A character is different from their family/tribe and feels utterly alone. Eventually they find their ‘people’ who accept them for who they really are. Understanding they are not alone in the world after all, the main character accepts themselves. Now they can be happy.

TRANSGRESSION STORY

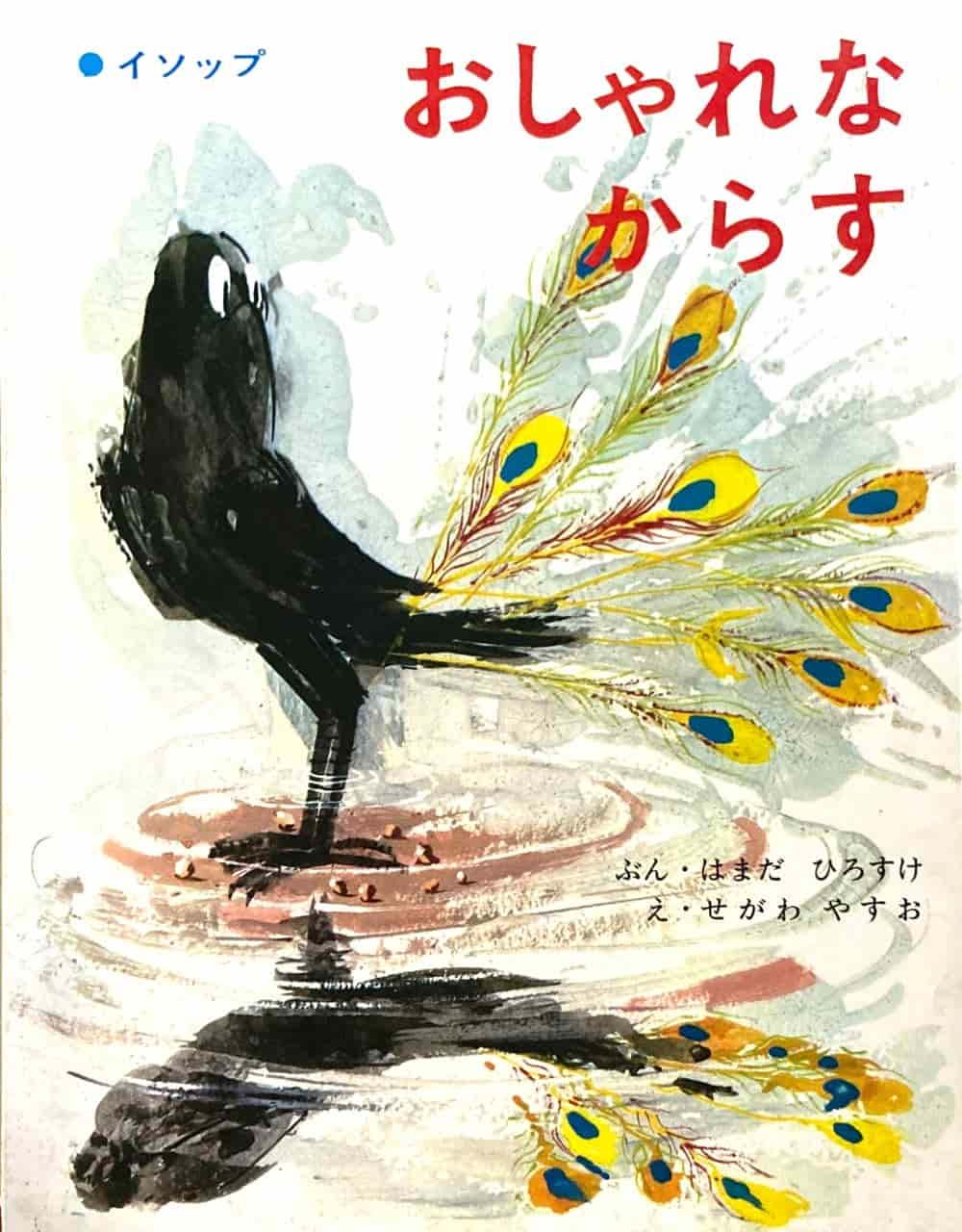

“The Ugly Duckling” is, at heart, a transgression story. In any transgression story the mask must come off at some point, revealing the animal’s true self. Stories in which a character wears ‘someone else’s’ identity and remains hidden are rare and run counter to audience expectation.

A STORY OF HERMENEUTICAL INJUSTICE

Hermeneutical injustice is a type of epistemic injustice, as named by philosopher Miranda Fricker, and refers to the injustice of not having access to information which would improve your life. Being gay in a world where everything about being gay is taboo, including the word, is one example of hermeneutical injustice.

LONELINESS

This basic plot of loneliness to community to acceptance is ancient, and not surprisingly so, since humans are a social species. Separated from their tribe in the wild, a human won’t survive for long. Unlike all other animals species, the human woman cannot so much as give birth on her own.

Most non-human primates give birth unassisted with relatively little difficulty.

Obstretrical Dilemma, Wikipedia

Partly for biomechanical reasons, loneliness for us means death, even more than for many other species. This age-old loneliness plot taps into the most primal of human fears. And in children’s literature in particular, stories very often begin with the empathetic main character in a state of loneliness, hence all the moving house/starting new school stories. The child character also quite often starts from a state of boredom, though some loneliness researchers include ‘boredom’ as a type of loneliness (called ‘existential* loneliness’ — being without a purpose in the world).

*Existentialism: an outlook which begins with a disoriented individual facing a confused world that they can’t accept. Existentialism’s negative side emphasizes life’s meaningless and human alienation. Think: nothingness, sickness, loneliness, nausea.

ANIMALS AS HUMANS

Although “The Ugly Duckling” features an animal main character, this is clearly a story about humans.

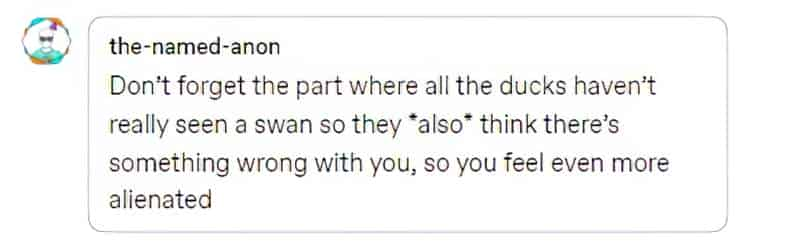

In The Ugly Duckling, Hans Andersen uses animal symbolism to tell a disguised human story. It unites animal transformation and animal moral tale in a unique way; it is about an unrecognised metamorphosis that really isn’t one at all. The Duckling only appears to be a strange outcast because no one knows what he really is, even his mother, who took trouble in hatching and defending him, gives up at last, wishing he had never been born.

Margaret Blount, Animal Land

Blount goes on to explain what Hans Christian Andersen brought afresh to this tale which otherwise relies heavily on Aesopian fable:

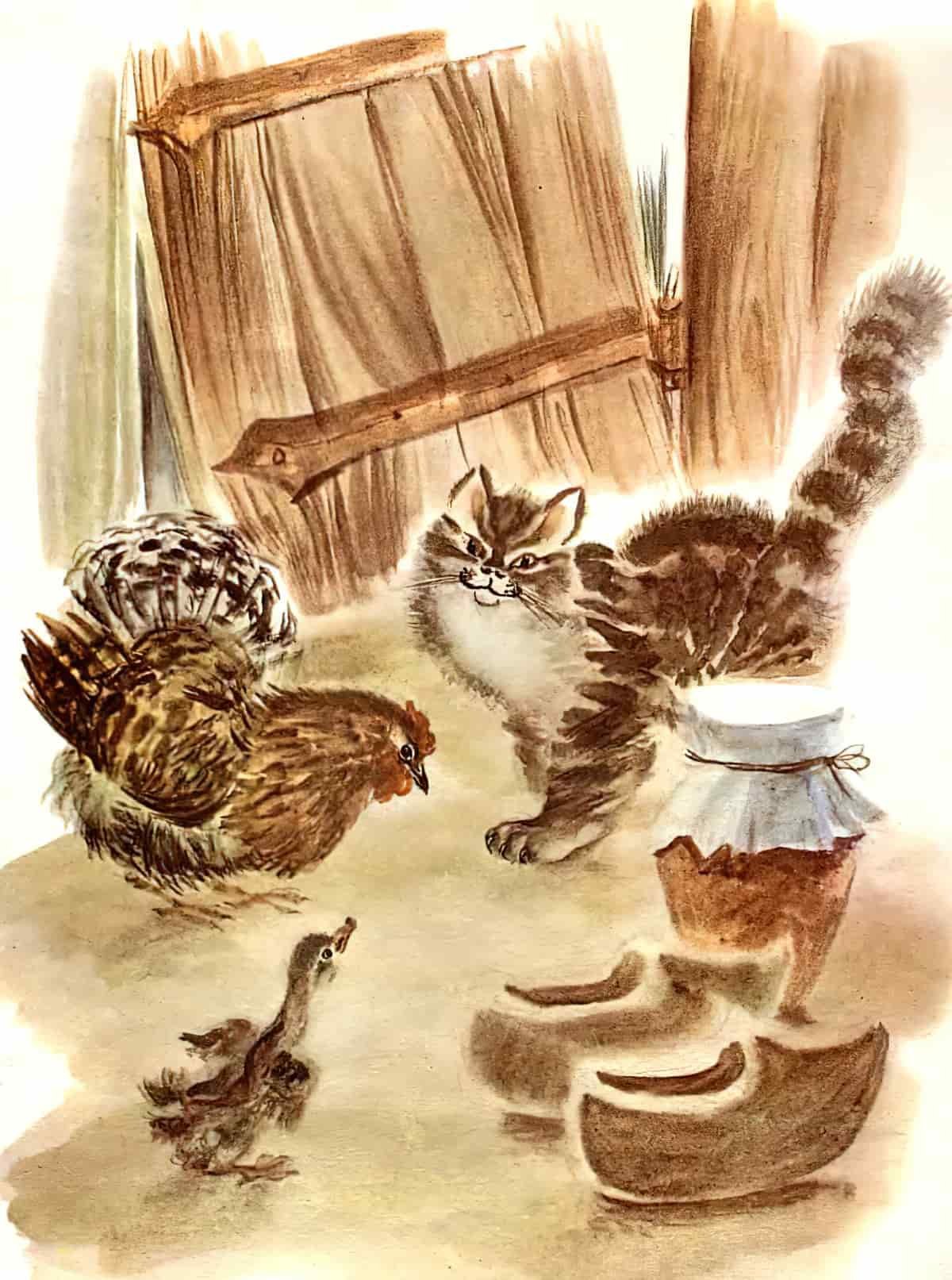

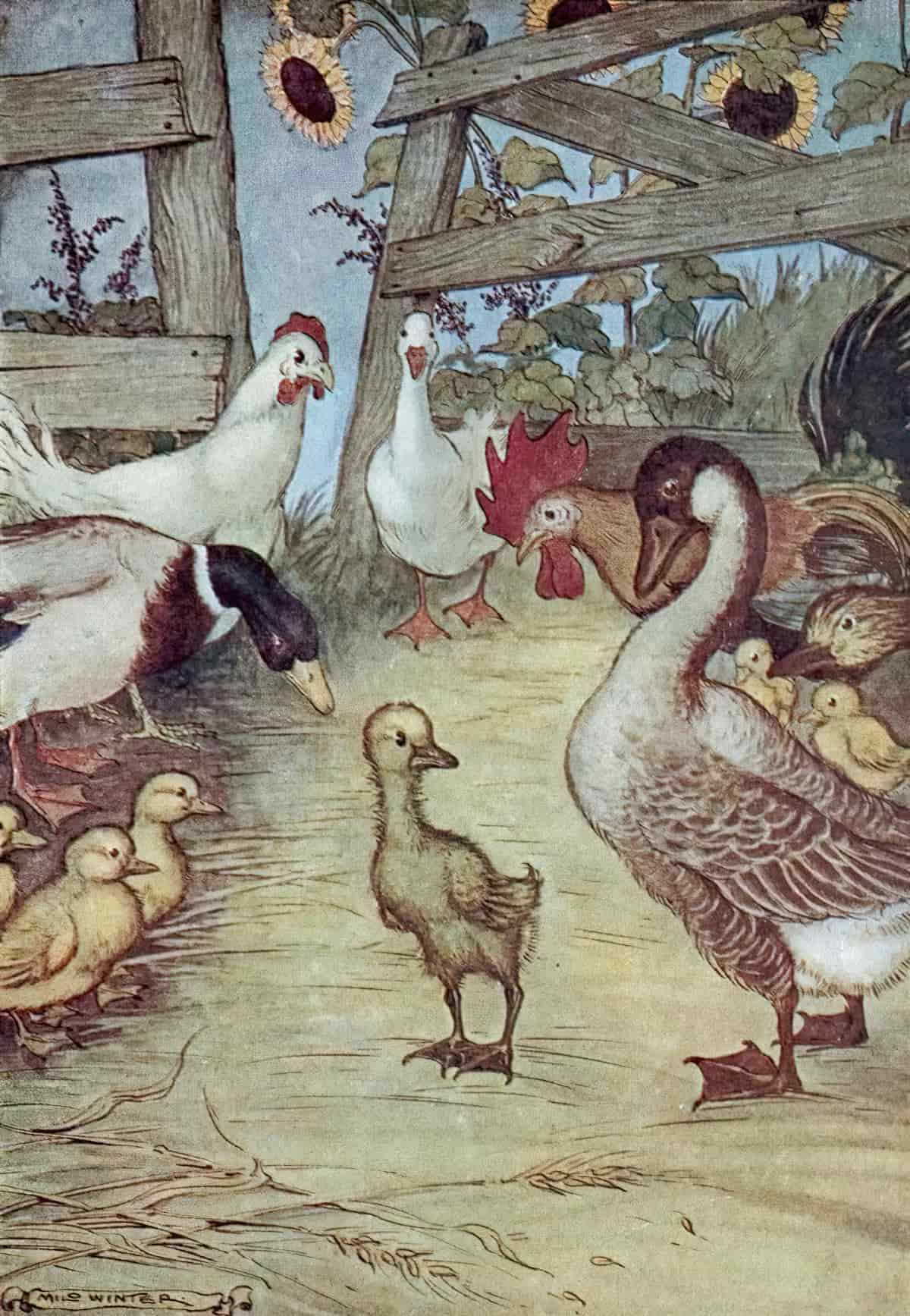

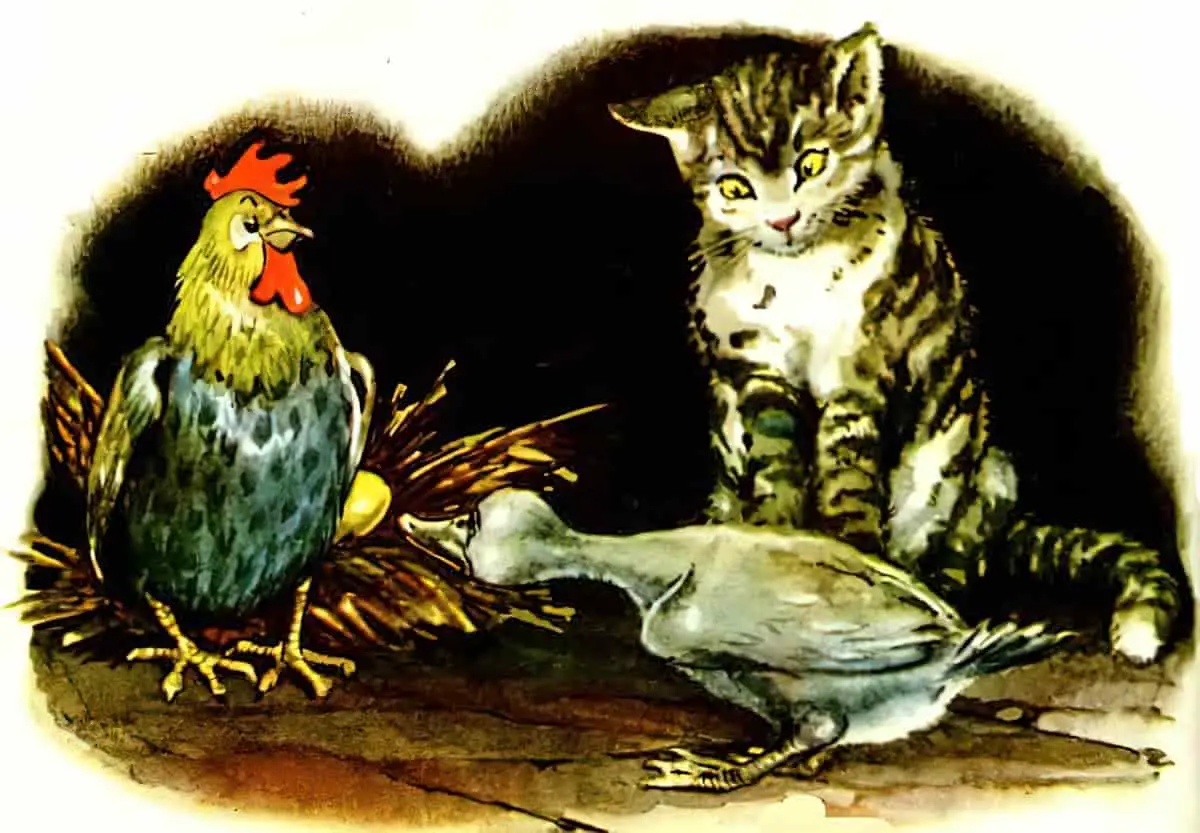

The pathos of this strange and beautiful fable is quite new to the form. The Aesop elements are there: the proud turkey cock, the old duck with the red rag of honour, and the incident when the animals quarrel over an eel head which is seized by the cat; and there is a house too, where the cat is master and the hen mistress. But there is far more than barnyard comedy in the rejection of the Duckling and his efforts to do what his nature demands, always thwarted by animals who, when he wants to swim, tell him to lay eggs or purr. Thrown out, hunted, half-starved, frozen, when he eventually meets the swans, his life has become so wretched and hopeless that he is only conscious of ugliness so great that he expects death.

Margaret Blount, Animal Land

THE UGLY DUCKLING AND THE LIFE OF HANS CHRISTIAN ANDERSEN

Apparently, when Hans Christian Andersen was asked whether he would write an autobiography he replied that “The Ugly Duckling” did the job.

Perhaps Hans Andersen was writing about himself. Everyone interprets the fable in [their] own way, for the story has an echo in everyone. As a fairy tale it is, like many of Andersen’s, very odd. The happy climax is so long delayed that it almost does not happen, unlike Cinderella (with the same plot) where we know the heroine is favoured and only unrecognised by an odd quirk that magic will soon put right. The long suffereings of the lonely duck are alien to the setting which (Orwell always excepted) from Chaucer to Hepzibah Hen is usually gay and superficial. The moral is the one about appearance and reality, expressed by birds so memorably and wonderfully that there is no need to call the story a Parable from Nature; these simple symbols have expressed universal truth as only a story teller of genius can do.

Margaret Blount, Animal Land

One of the well-known fairy tales that ends happily is The Ugly Duckling. The poor duckling is mocked and humiliated because he is so ugly, but he finally turns into a beautiful swan. On closer examination, what does this story say? It has been usually interpreted as follows: after many hardships, patience and perseverance will be rewarded. But if we stop to think about it, the ugly duckling has turned into a swan only bcause he was hatched from a swan’s egg. If he had been a real duckling, he would have grown into a duck. What does Andersen mean by his tale? Some biographers believe that Andersen was not the son of a washerwoman and a cobbler, but the illegitimate child of a nobleman, perhaps even the king of Denmark. There is no direct evidence for this, but the indications are strong. Perhaps The Ugly Duckling is the author’s way of saying, “I have achieved fame and wealth only because I am in fact of noble birth.”

Another possibility is that Andersen himself believed that he was of noble birth, even if it was not true. In this case, Andersen was suffereing from an obsession, a psychotic condition, traces of which we see in his fairy tale. This is an example of speculative biographical approach. It would perhaps be unwise to apply it as a consistent critical method, but it does illustrate the possibility of using literary works to illuminate the author’s life. However, this approach has little to do with the study of literature. If the focus of psychoanalysis is on the author, then the literary text is used merely as any narrative the patient may tell to the analyst.

from Aesthetic Approaches To Children’s Literature by Maria Nikolajeva

SETTING OF THE UGLY DUCKLING

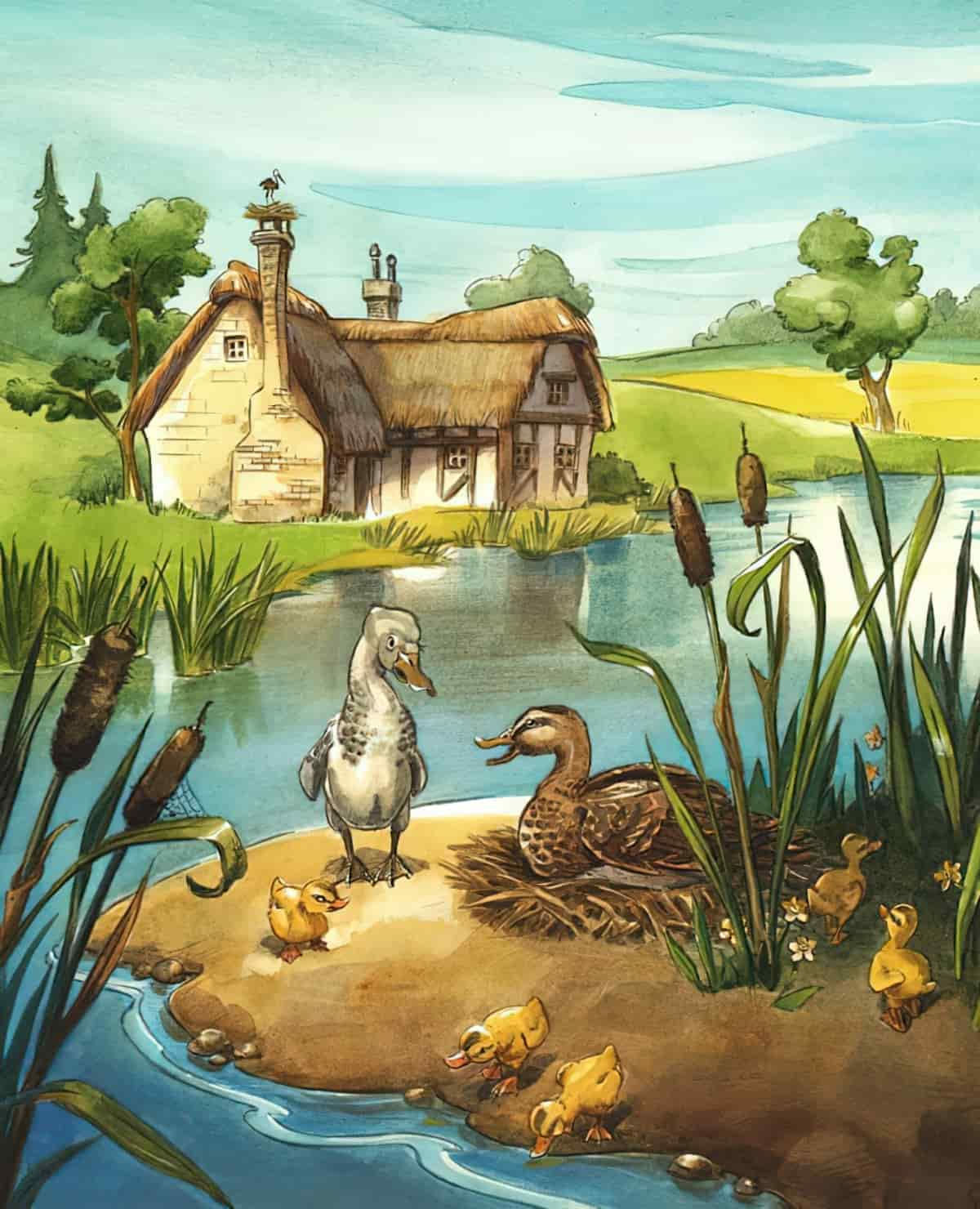

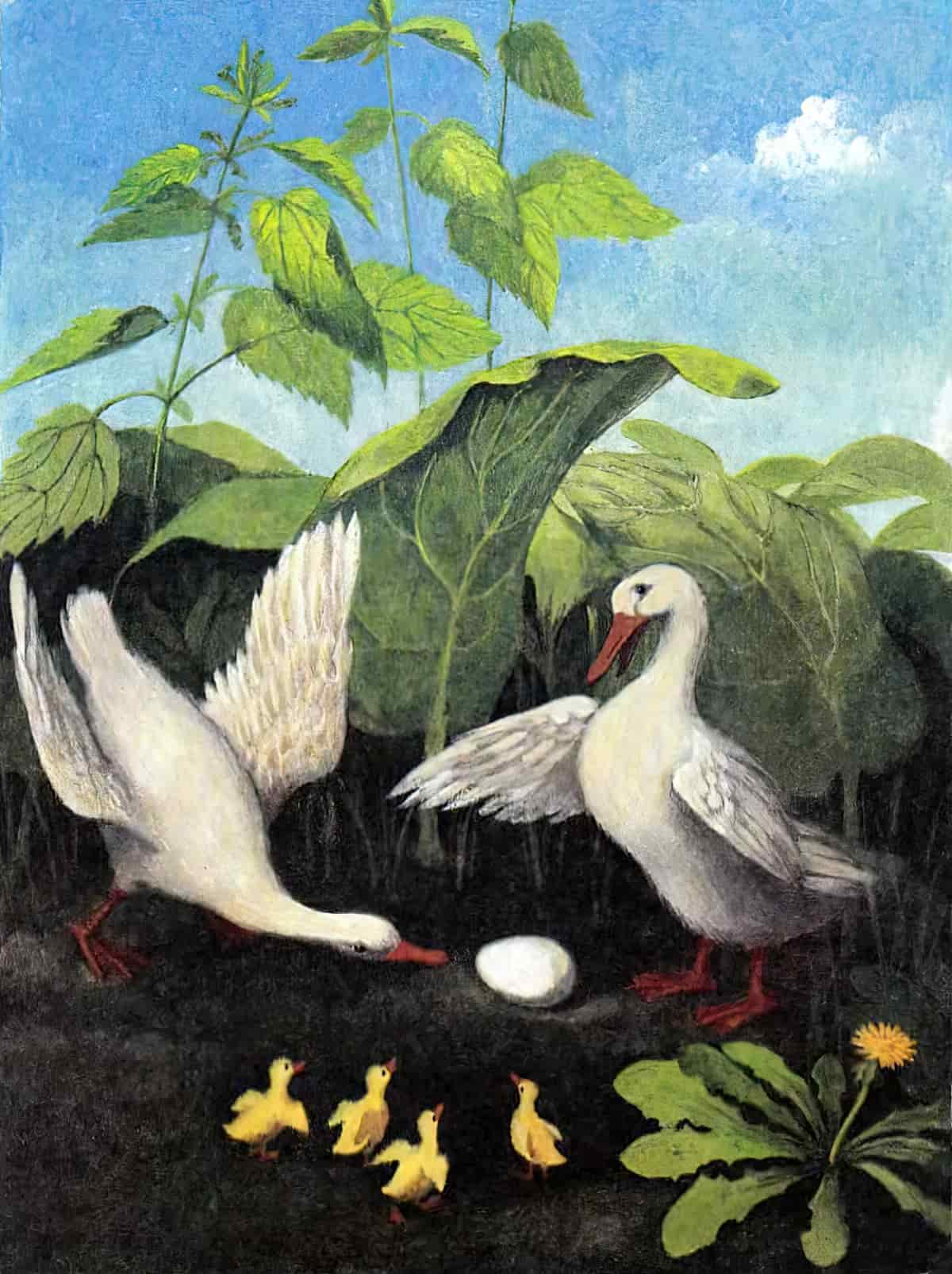

“The Ugly Duckling” is an atemporal story that takes place on a river and riverbank. The group of birds is an animal community standing as allegory for human community.

STORY STRUCTURE OF THE UGLY DUCKLING

PARATEXT

“The Ugly Duckling” (“Den grimme ælling”) is a good example of judicious title change. Hans Christian Andersen originally called this story “The Young Swans” but realised the title completely gave away the surprise ending. Don’t give away your ending in the title!

For over one hundred years The Ugly Duckling has been a childhood favorite, and Jerry Pinkney’s spectacular new adaptation brings it triumphantly to new generations of readers. With keen emotion and fresh vision, the acclaimed artist captures the essence of the tale’s timeless appeal: The journey of the awkward little bird — marching bravely through hecklers, hunters, and cruel seasons — is an unforgettable survival story; this blooming into a graceful swan is a reminder of the patience often necessary to discover true happiness. Splendid watercolors set in the lush countryside bring drama to life.

an example of modern marketing copy for “The Ugly Duckling” turned into a picture book

SHORTCOMING

The problem is that the Ugly Duckling is different.

I’m not sure who decided ducklings are prettier than baby swans. To me they’re about even. The drake’s feathers rival the majestic outline of the grown swan. I wonder if people ranked the prettiness of these water birds before Hans Christian Andersen turned ‘ugly duckling’ into a meme.

In any case, the baby swan’s main shortcoming is that he is ugly. And because he is ugly, even his mother rejects him. If that’s not pulling at the reader’s heartstrings, I don’t know what will.

DESIRE

As a repository for many socio-cultural feelings and attitudes, ugliness operates in ways that have dangerous and deadly consequences for bodies and those who inhabit them. When a body is labeled or understood as “ugly,” it is subsequently targeted for expunging, overlooking, destruction, and affectively motivated terror.

On The Politics of Ugliness (Introduction)

The desire to be not ugly is basically a desire to be loved. He thinks that if he weren’t ugly then he would be loved. (He is never proven wrong on this point; he is loved once he morphs into a beautiful swan.)

OPPONENT

The mother duck is most responsible for the Ugly Duckling’s rejection. She models her distaste for him and the genetic offspring all gang up. So does every single creature who comes into contact with the Ugly Duckling, though he does meet someone who wants to help him find love despite being ugly: The geese. These guys are more like allies than opponents. The Ugly Duckling never did want to be associated with ugly birds. He knew deep down he was better than that.

PLAN

The Ugly Duckling feels down and waits around to mature. That’s not such bad advice for the mid-teen years.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

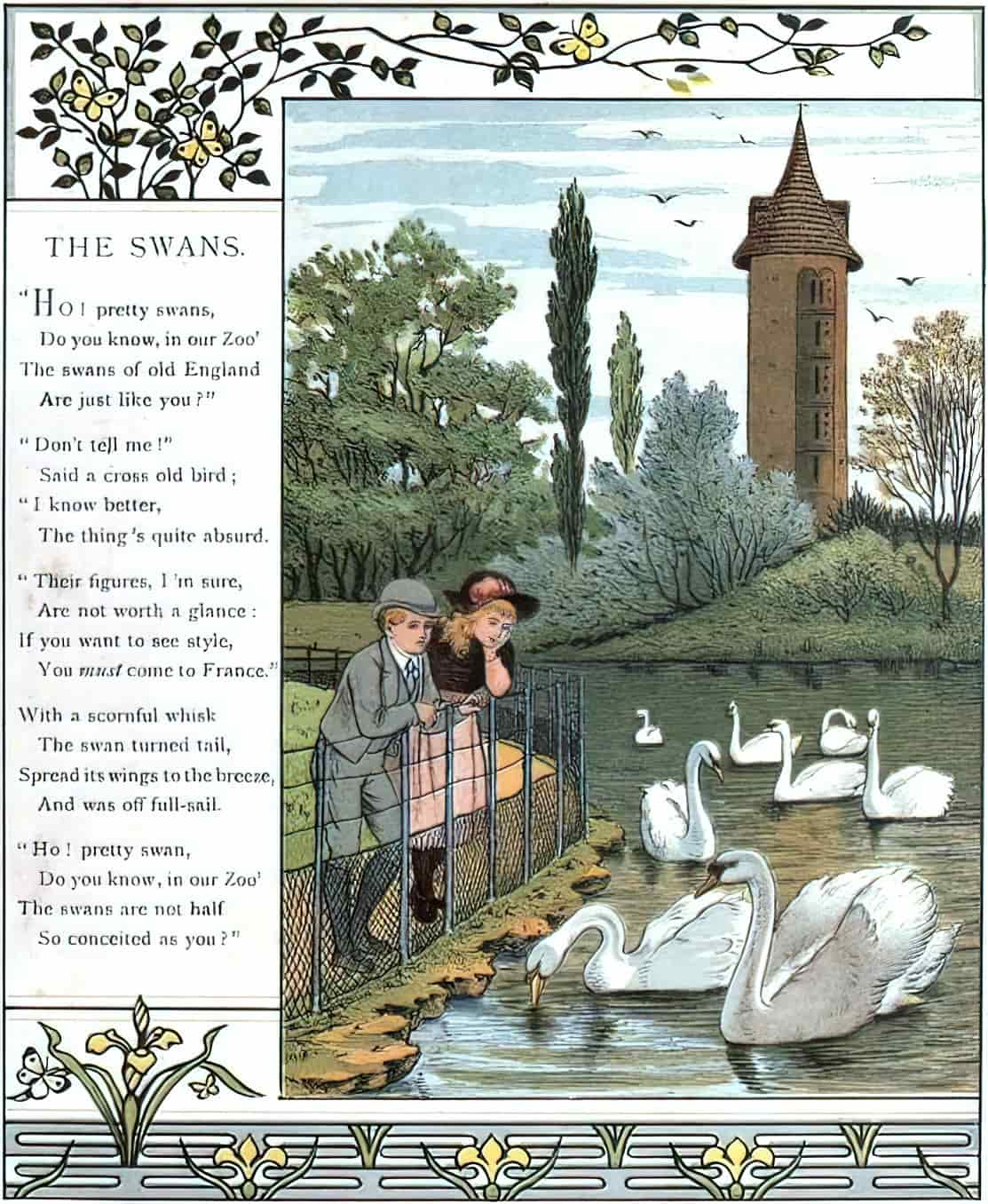

The Ugly Duckling thinks he’s going to be murdered by the massive, good-looking swans and offers himself up to them. They can murder him if they want; he feels so wretched and ugly and useless.

ANAGNORISIS

He looks into the reflection and sees that he has grown into a swan.

NEW SITUATION

The Ugly Duckling is really a swan, so will leave the ducks to live happily ever after as a beautiful swan.

Anastasia Aekhipova, illustrations for The Ugly Duckling from The Steadfast Tin Soldier and Other Fairy Tales, 1980. Illustrations to this story are often done in old master style.

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

Everyone is happier once they are able to live as themselves, so I guess this swan doesn’t have much keeping him down anymore.

No one really disagrees with the idea that in order to be happy you must find your people and thereby find self-acceptance.

But what might Andersen have been wrong about? Which ideas feel dated when read through a modern lens?

The mother duck thinks her own babies are pretty because she gave birth to them. This suggests mothers love genetically related children more than adopted children. Studies don’t bear out this idea at all. Parents don’t love their children equally, but there’s no detectable difference between genetic and adopted offspring when both are raised from birth.

The ugly ‘duckling’ feels so ugly that ‘even a dog will not bite me’. If we take that as a stand-in for abuse in general, it is simply incorrect that a person can be too ugly to be victimised. This probably wouldn’t bother me if it weren’t used as an actual defense in court when trying to prove the innocence of rapists. This is an example of yet another thing the Ugly Duckling is wrong about. (Main characters are meant to be wrong about something otherwise there’s not much of a character arc.) However, the Ugly Duckling never learns that he is wrong on this point. It’s up to the reader to deduce that he must be wrong, because clearly he’s ugly AND he’s being abused.

The ugly duckling only feels legitimised once he looks into the reflection and sees a beautiful swan looking back. This is basically the make-over plot in which Beauty equals worthiness. More modern picturebook retellings of this story generally avoid the literal transformation from ugliness to beauty and instead limit the plot to ‘finds creatures who look just like him’. But what if you have some sort of facial difference and will never find your people? If we read “The Ugly Duckling” at the truly allegorical level, the baby swan was never ugly, only lacking in love. Therefore there was no literal transformation from ugly to beautiful; the bird felt beautiful after finding acceptance with creatures who accept him. The first Shrek movie works in a similar way. Shrek and Fiona are happy because they have ‘found their people’ (both of them ugly by comparison to the haughty, insecure, beautiful versions/imaginings of themselves). The message is ostensibly a positive one for kids: You’re as beautiful as you think you are. The other, unintended message: Know your level, kids. Ugly creatures belong with other ugly creatures; beautiful creatures belong with other beautiful creatures. Beauty is meaningful. Beauty is something we should all be constantly thinking about and trying to improve. In our image obsessed culture it feels hopelessly idealistic to believe that beauty doesn’t mean anything; clearly it does. But can we imagine and work towards a better world than one that runs on Beauty privilege?

[U]gliness is not one thing, and it is not a property of one body or another. It is, instead, … a “social location complexly embodied.”

On The Politics of Ugliness (Introduction)

“The Ugly Duckling” is basically a Chosen One story, in which bloodline is king. The Ugly Duckling is really a swan; the poor boy is really a prince. There are many ideological issues with the bloodline story, which remains popular in contemporary storytelling (see Harry Potter and all its offshoots).

RESONANCE

This story is so well-known that ‘ugly duckling’ is now a widely understood English idiom.

The Animal Who Thought He Was A Different Animal is an enduring trope across children’s literature:

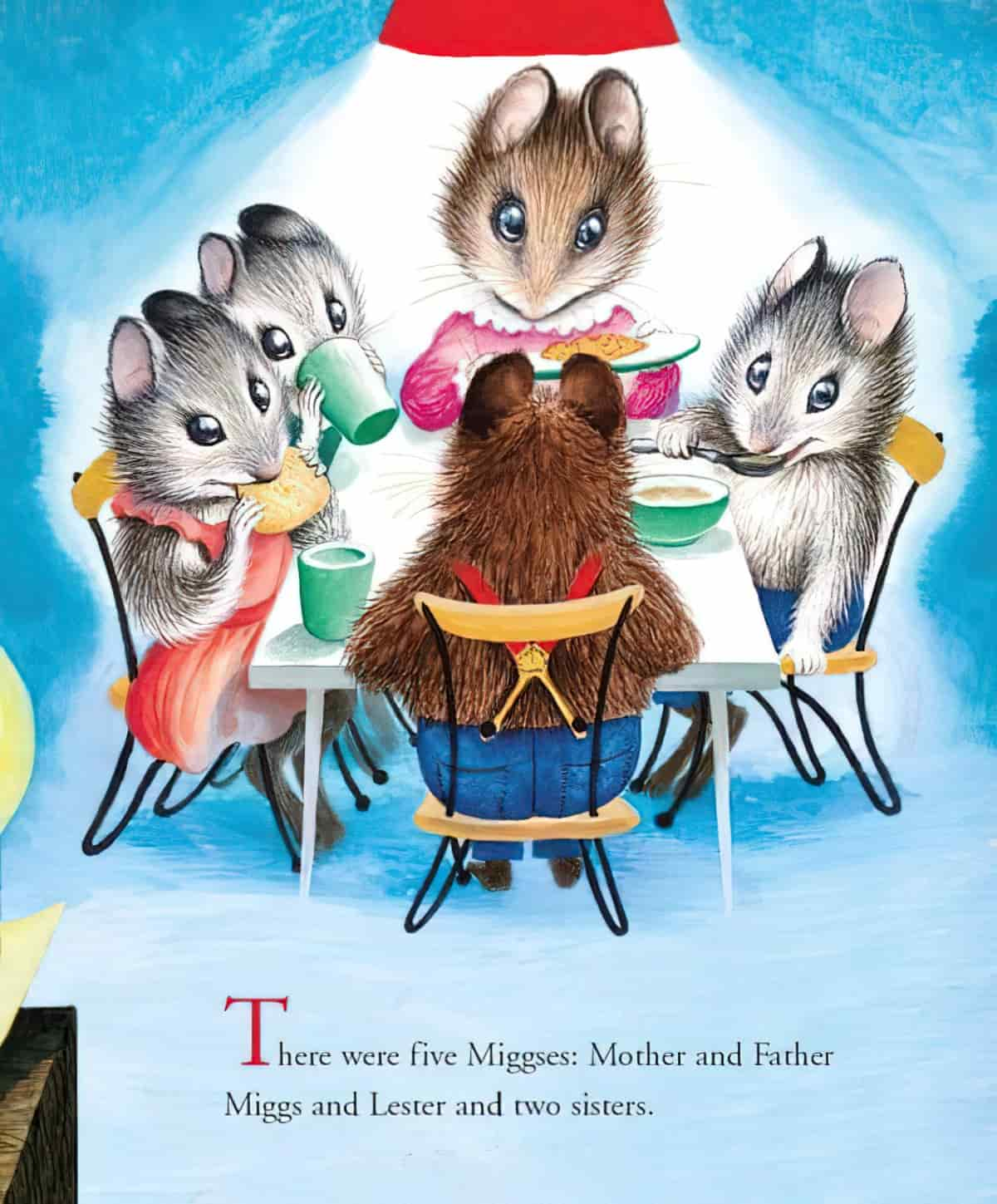

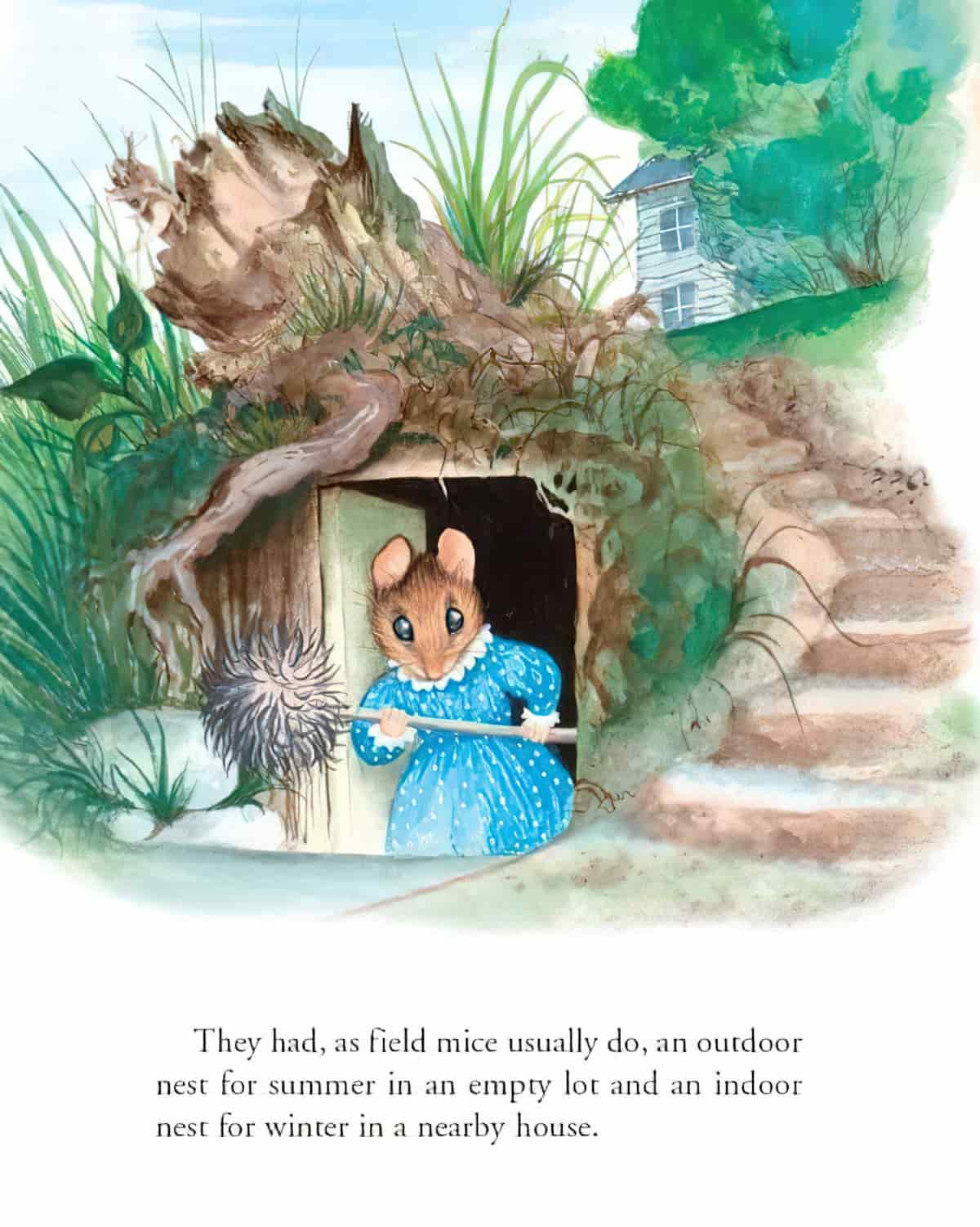

- The Kitten Who Thought He Was A Mouse

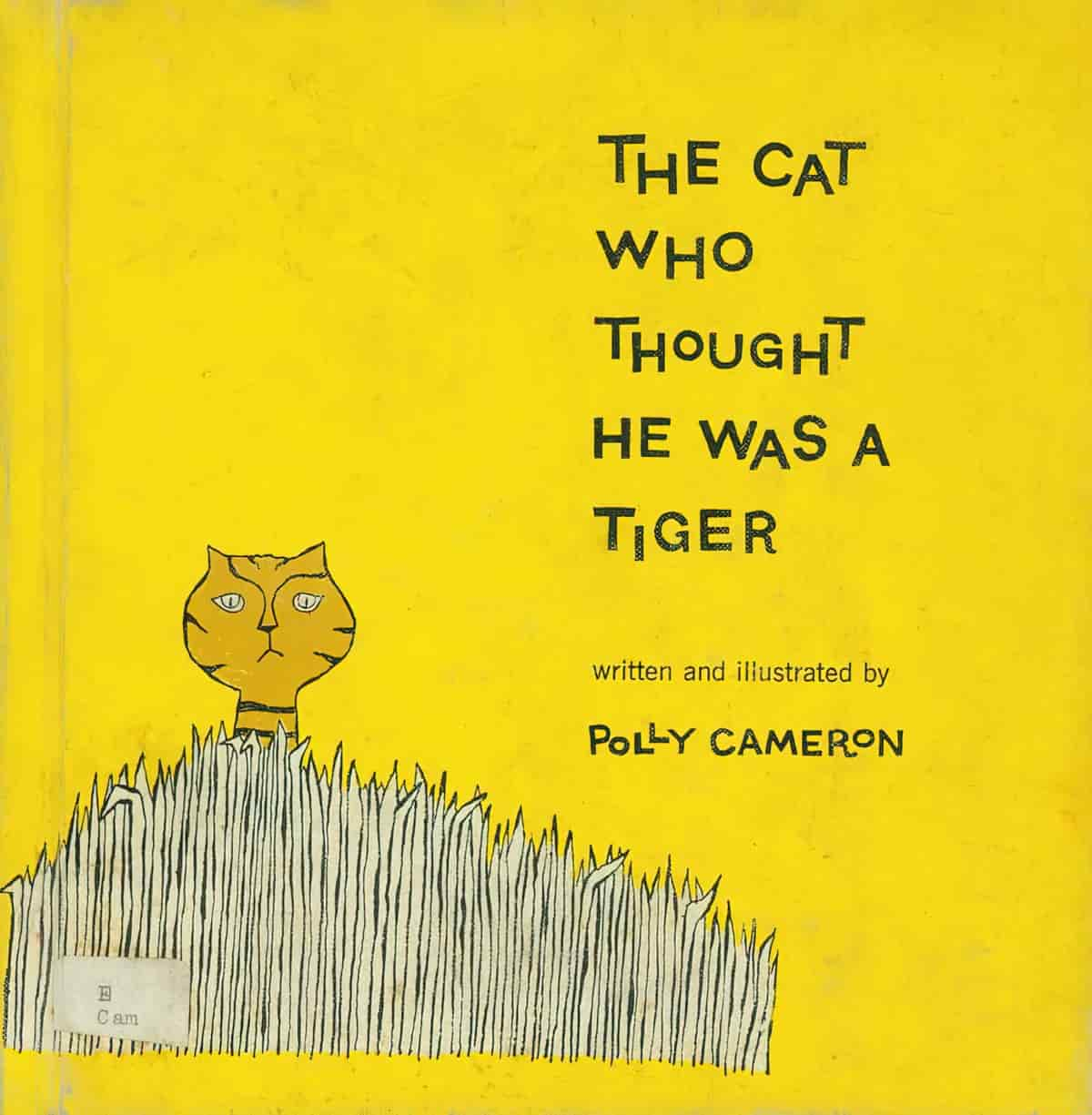

- The Cat Who Thought He Was A Tiger

- The Girl Who Thought She Was A Dog

- Pumpkin: The Raccoon Who Thought She Was A Dog

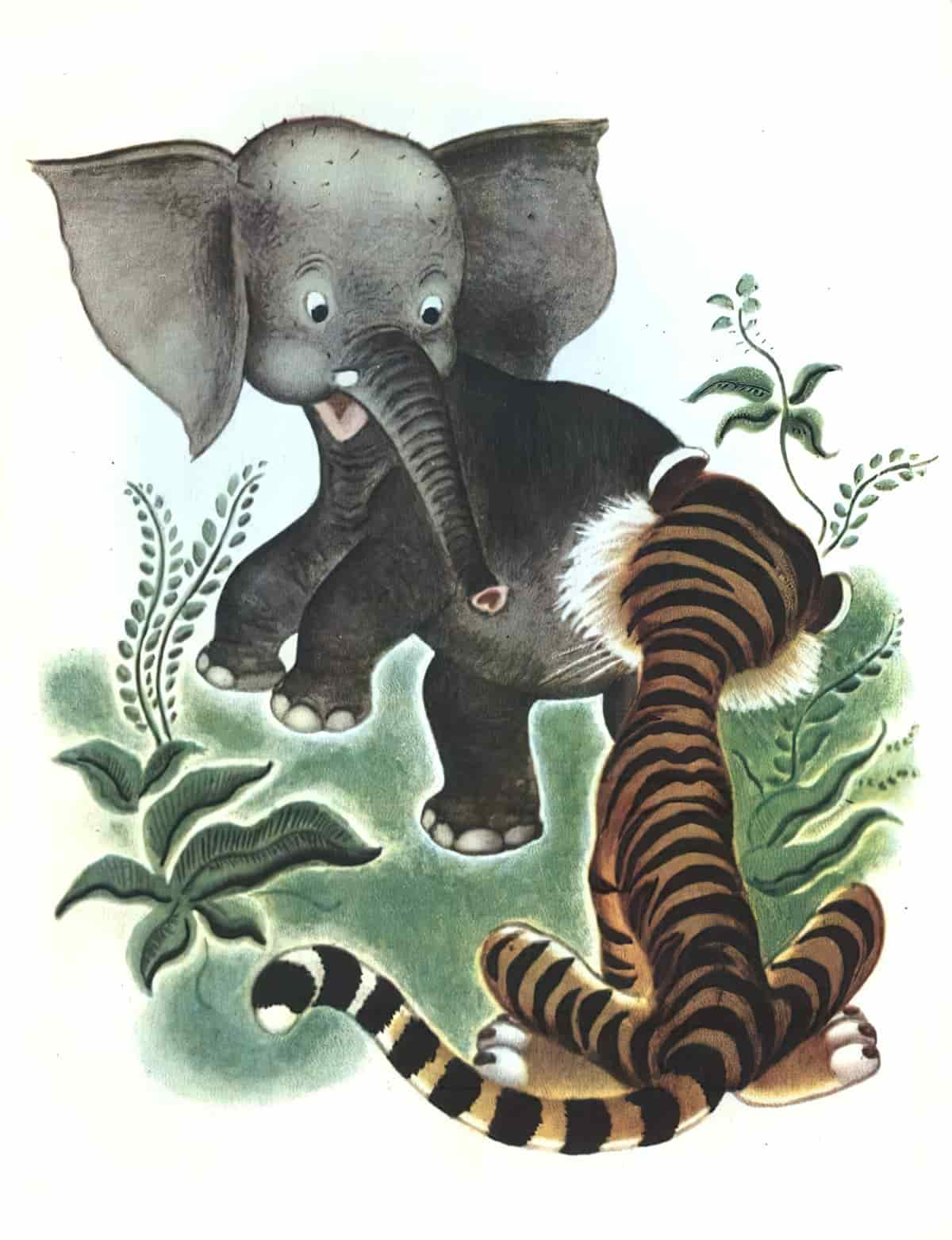

Then there’s the animal who wished he were a different animal. The Saggy Baggy Elephant is a Little Golden Book by Jackson and Tenggren, first published in 1947. In the jungle, a bird taunts a baby elephant, saying his skin is too baggy. He doesn’t seem to realise he’s been separated from his tribe. The poor elephant feels self-conscious and tries to shrink his skin so he won’t be wrinkled. The tiger, whose sleek skin fits ‘perfectly’ is no help and instead offers to eat bits of it off for him. (That part is quite gruesome by today’s picture book standards.) The saggy, baggy elephant finds happiness and self-acceptance after meeting other elephants.

“There is probably no better or more reliable measure of whether a woman has spent time in ugly duckling status at some point or all throughout her life than her inability to digest a sincere compliment. Although it could be a matter of modesty, or could be attributed to shyness- although too many serious wounds are carelessly written off as “nothing but shyness”- more often a compliment is stuttered around about because it sets up an automatic and unpleasant dialogue in the woman’s mind.

If you say how lovely she is, or how beautiful her art is, or compliment anything else her soul took part in, inspired, or suffused, something in her mind says she is undeserving and you, the complimentor, are an idiot for thinking such a thing to begin with. Rather than understand that the beauty of her soul shines through when she is being herself, the woman changes the subject and effectively snatches nourishment away from the soul-self, which thrives on being acknowledged.”

“I must admit, I sometimes find it useful in my practice to delineate the various typologies of personality as cats and hens and ducks and swans and so forth. If warranted, I might ask my client to assume for a moment that she is a swan who does not realzie it. Assume also for a moment that she has been brought up by or is currently surrounded by ducks.

There is nothing wrong with ducks, I assure them, or with swans. But ducks are ducks and swans are swans. Sometimes to make the point I have to move to other animal metaphors. I like to use mice. What if you were raised by the mice people? But what if you’re, say, a swan. Swans and mice hate each other’s food for the most part. They each think the other smells funny. They are not interested in spending time together, and if they did, one would be constantly harassing the other.

But what if you, being a swan, had to pretend you were a mouse? What if you had to pretend to be gray and furry and tiny? What you had no long snaky tail to carry in the air on tail-carrying day? What if wherever you went you tried to walk like a mouse, but you waddled instead? What if you tried to talk like a mouse, but insteade out came a honk every time? Wouldn’t you be the most miserable creature in the world?

The answer is an inequivocal yes. So why, if this is all so and too true, do women keep trying to bend and fold themselves into shapes that are not theirs? I must say, from years of clinical observation of this problem, that most of the time it is not because of deep-seated masochism or a malignant dedication to self-destruction or anything of that nature. More often it is because the woman simply doesn’t know any better. She is unmothered.”

Clarissa Pinkola Estés, Women Who Run With the Wolves: Myths and Stories of the Wild Woman Archetype

Arthur by Amanda Graham picture book 1984

Arthur is an ordinary brown dog and nobody wants him so he practises being other, more popular pets.

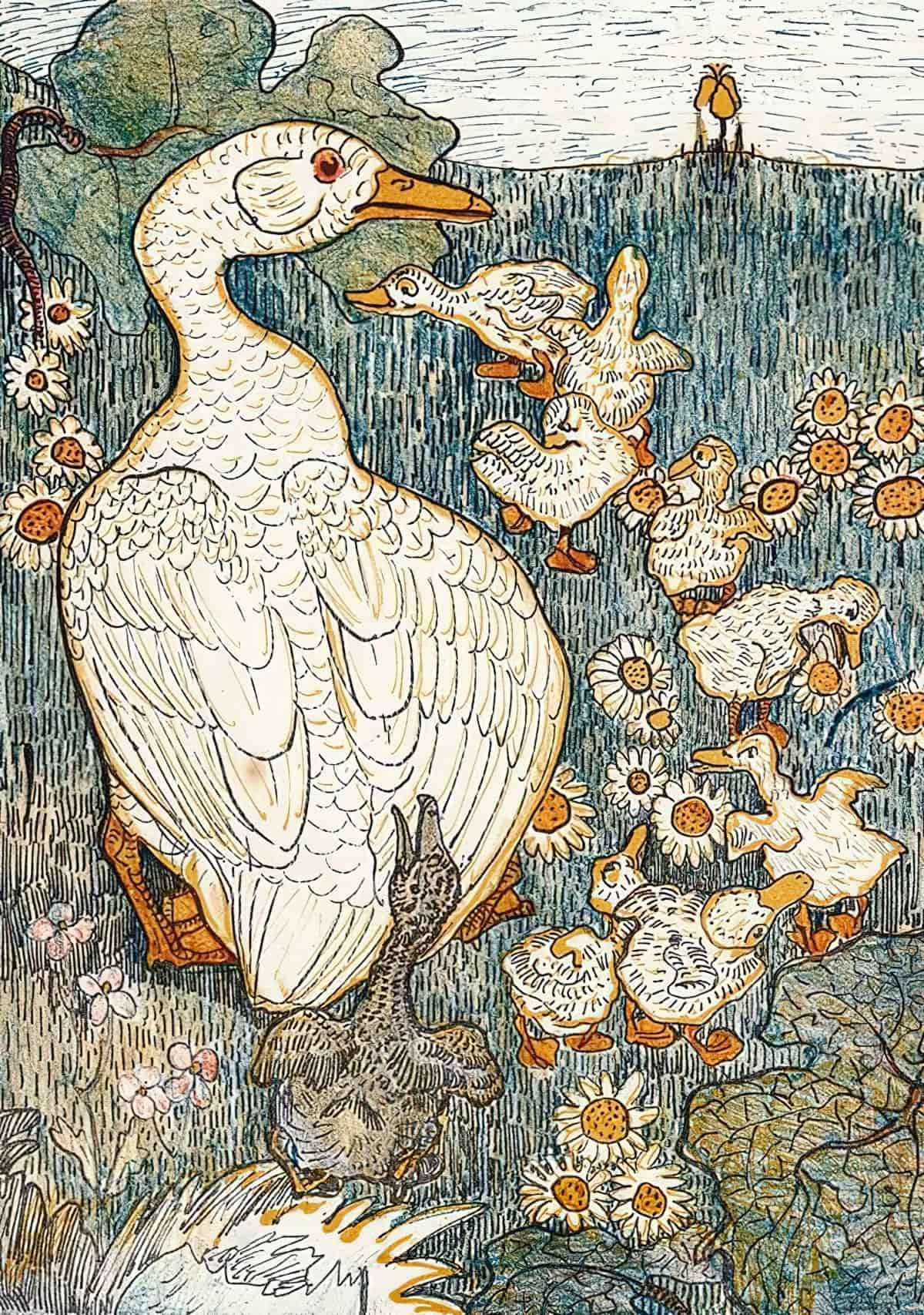

Header illustration from Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Ugly Duckling” by Vilhelm Pedersen