“U.F.O. in Kushiro” is a short story written by popular contemporary Japanese author Haruki Murakami. English readers first had access to the story in 2001, when it appeared in an issue of the New Yorker magazine. The story was republished in 2011 after an earthquake and tsunami devastated northern Japan. Safe to say this is considered a Japan-disaster-story.

Bryan Washington joins Deborah Treisman to read and discuss “U.F.O. in Kushiro,” by Haruki Murakami.

But “U.F.O. in Kushiro” is not really about the Hanshin earthquake, one of Japan’s most devastating and expensive disasters in history. To convey the magnitude of disaster in a short story is difficult because of the phenomenon of ‘psychic numbing‘. I’m sure we’re all feeling that in the year 2020. It’s impossible to extend equivalent empathy to everyone affected by disaster, but when we hear about someone’s personal tragedies, we can be overcome with empathy for them, personally, because we can more easily imagine the trials of one person, or one small community.

To get around the psychic numbing, Murakami has focused on the story of an individual. Unusually for a ‘disaster story’ though, this individual isn’t near the scene of the disaster, but instead lives in Tokyo, three hours away from Kobe (by train). But in a different way this is a story about psychic numbing. The main character is entirely passive right until the end of the story. He does what he is told to do by others. He is numb because his wife has left him and he did not see it coming. ‘The ground shifts beneath him.’ The symbolism of the earthquake is very clear.

What big ideas is Murakami hoping readers will explore in this story? Which storytelling techniques does he utilised to take us there? Let’s take a look.

SETTING OF U.F.O. IN KUSHIRO

PERIOD — The weeks after the Great Hanshin earthquake in 1995. (Safely ensconced in New Zealand, I was finishing my final year of high school and preparing to spend a year as an exchange student in Yokohama, near Tokyo. I head hear that Japan was prone to earthquakes; now I knew it was a distinct possibility.)

DURATION — A few weeks, focusing on a single day. Many lyrical short stories weave the past into the present and the main characters experience a kind of overlaid time, in which the present cannot be separated from the past because the present is always affected by it. Writers convey this sensation in a variety of ways. Murakami’s is original:

Keiko slung the bag over her shoulder and walked off toward a distant phone booth. Komura studied the way she walked. The upper half of her body was still, while everything from the hips down made large, smooth, mechanical movements. He had the impression that he was witnessing some moment from the past, shoved with random suddenness into the present.

LOCATION — The story starts in Tokyo, then the main character flies to Hokkaido, which is quite different from the mainland of Japan. People in Hokkaido speak dialects that mainlanders find amusing and quaint. None of this comes across in the English translation and I wonder if it’s there in the Japanese, which could make the Hokkaido women seem slightly unhinged, especially when they start talking about U.F.O.s, which in Japanese is a loanword pronounced ‘YUU-fo’. (With the letters forming a word rather than spelt out as separate letters.)

In Japan, ‘YUU-fo’ is also a well-known brand of noodles. I’m guessing the brand name comes from the shape of the container, which is disc-like. The marketing campaign for these noodles is always camped up for humorous effect.

ARENA —The entire story takes place within Japan, but to the main character, the trip from Tokyo to Hokkaido would feel like an intercultural experience (especially as he’s never been up there before).

MANMADE SPACES — Komura works in Akihabara, a suburb of Tokyo full of electronics stores. This is pretty much as far as Japan gets from the more natural environment of Hokkaido.

NATURAL SETTINGS — Although Komura goes up to Hokkaido, he is still mostly indoors — first the car, then the noodle restaurant, then the love hotel. One of my fellow exchange students in 1996 — a French Canadian — lived with a host family who owned and ran a love hotel. This kid was always flush with cash, which he earned doing jobs around the hotel. Love hotels are an accepted part of Japanese culture, and I couldn’t imagine similar establishments existing so openly in my conservative hometown of Christchurch, New Zealand, though from what I can tell Japan has become more conservative since the 1990s, with LGBTQ patrons turned away from love hotels, ostensibly (and legally) for everyone.

Akira Nishiyama, assistant executive director of the Japan Alliance for LGBT Legislation, said hotel rejections of same-sex couples were common, even though it is illegal under a 2018 revision to the hotel business law, which states that hotels “should not reject guests on the basis of their sexual orientation.

The Guardian

Before Japan opened up to foreigners, literature and art suggests Japan was a-ok with all manner of human diversity in its floating world. It is disturbing that progress does not march in linear fashion from repressed to liberal, but can swing back the other way, and vehemently.

WEATHER — Hokkaido is often banked up with snow, reflected in the way buildings are constructed. This is the middle of winter. (Komura can’t believe so many people are going to Kushiro in the middle of winter.)

TECHNOLOGY CRUCIAL TO THIS PARTICULAR STORY — Technology is crucial in science fiction stories, but this isn’t science fiction. What is it? Realism? Murakami takes us to the ‘seedier’ side of Japan — to a love hotel — and if he were a Western writer we might say he was writing ‘dirty realism’. But he’s not exactly reminiscent of Carson McCullers, Annie Proulx and Raymond Carver either, is he? Murakami’s ‘realism’ is slightly different again. The reader can choose whether or not to believe the U.F.O. story. It’s not actually the U.F.O. diversion which gives a sense of unreality to this story — it’s the plot itself, in which a man asks his friend to deliver a box without telling him what’s inside it. This doesn’t feel like something that’d happen in real life (I’d be worried about drugs). Mind you, precisely because Japan cracks down so hard on drugs, it’s actually pretty unlikely that your mate would be asking you to function as a mule if you’re outside established gang circles. Komura’s naivety in this regard is coloured by my reading 25 years later, from other countries where drugs are more accepted by society (even if not encoded in law).

LEVEL OF CONFLICT — Big disasters tend to shake us out of complacency, even if we are not directly involved. For Komura’s wife, the Hanshin earthquake seems to remind her of the emotional rift between herself and her good-looking husband with the good job, though we never hear her side of things. I deduce her side of things after the scenes with the two women in Hokkaido, who are doing all of the emotional labour as hostesses for this man.

THE EMOTIONAL LANDSCAPE — Komura’s wife has said in her Dear John letter that Komura is made of a chunk of air. It’s up to the reader to decide whether this is accurate or not, so how much interiority does Murakami give us? Not much. My reading is this: After getting married, Komura decided to give up his individuality and sink into unhealthy co-dependency, or the unilaternal version, in which the wife does all the real work of relationships. When we hear that his wife took off like Thelma to her hometown of Yamagata with no notice, we never hear her side of things, but I’m guessing she needed a break from being the adult in the relationship. Interesting that she took her breaks by returning home to Daddy, which I deduce — from Murakami’s detail — that she can sink into the role of ‘daughter’ (little girl).

CAST OF CHARACTERS

Komura

Komura was tall and slim and a stylish dresser. He was good with people. In his bachelor days, he had dated a lot of women. But after getting married, at twenty-six, he found that his desire for sexual adventures simply—and mysteriously—vanished. He hadn’t slept with any woman but his wife during the five years of their marriage. Not that the opportunity had never presented itself—but he had lost all interest in fleeting affairs and one-night stands. He much preferred to come home early, have a relaxed meal with his wife, talk with her awhile on the sofa, then go to bed and make love. This was everything he wanted.

Komura’s wife

In daily life we rarely speak of the rule of beauty equivalency. Social experiments have been done on pop-psychology TV shows — I remember one in which men and women were asked to form two lines, divided by gender, and they were asked to line up in order of attractiveness, rating themselves against others. No one had any trouble with this exercise. Everyone’s always looking at everyone else, and rating them on some scale of sexual attractiveness. It’s depressing. I find certain popular male writers in particular are very upfront about this reality of human nature. Murakami is well-known for his hyperfixation on women’s breasts. I know this about him even though this is the first thing of his I’ve ever read. No boobs in this particular story, but I am noticing in his thumbnail descriptions of his cast that his narrator is a ‘beauty ranker’.

Komura’s friends were puzzled by his marriage. Next to his clean, classic looks, his wife could not have seemed more ordinary. She was short, with thick arms, and she had a dull, even stolid, appearance. And it wasn’t just physical: there was nothing attractive about her personality, either. She rarely spoke, and her expression was often sullen.

By pairing Komura with a wife who is less sexually marketable than himself, is Murakami critiquing this human tendency to rank, while at the same time completely falling into it himself, via his narration? It’s possible to both reinforce objectification in an ostensible attempt to critique it. To give an American example, I believe the creators of Mad Men did exactly that with their plotlines of female empowerment replete with naked and objectified women.

The character of Komura’s unnamed wife challenges the culturally dominant idea beneath the unspoken beauty equivalency rule: That people will only find happiness partnering up with someone of their own ‘level’. Komura is in fact (ironically?) very content with his un-beautiful wife:

Still, though he himself did not quite understand why, Komura always felt his tension dissipate when he and his wife were together under one roof; it was the only time he could truly relax. He slept well with her, undisturbed by the strange dreams that had troubled him in the past. His erections were hard; his sex life was warm. He no longer had to worry about death or venereal disease or the vastness of the universe.

While challenging his readers to critique the beauty equivalency violation he has just described, Murakami’s (clearly hetereosexual male narrator) nonetheless keeps offering thumbnail character descriptions which rank people by beauty, and most harshly, women.

KEIKO SASAKI

Two young women wearing overcoats of similar design and color approached Komura at the airport. One was fair-skinned and maybe five feet six, with short hair. The area from her nose to her full upper lip was oddly extended, in a way that made Komura think of short-haired hoofed animals.

Shimao

The other woman was closer to five feet one and would have been quite pretty if her nose hadn’t been so small. Her long hair fell straight to her shoulders. Her ears were exposed, and there were two moles on her right earlobe which were emphasized by the earrings she wore. Both women looked to be in their mid-twenties. They took Komura to a café in the airport.

Keiko and Shimao don’t become individuated until Keiko leaves the love hotel, leaving Shimao to make a move on the handsome fresh bachelor. They gently tease Komura for asking about bears — a dynamic I’m familar with now that I live in Australia. Australians love to tease foreigners about their fear of dangerous Australian animals, partly because it fills minds, and seems to leave little room for a more rounded and accurate view of Australia, an Australia in which people rarely encounter a dangerous animal. (After 14 years in semi-rural Australia I’m yet to encounter a wild snake.)

I get a little tired of Komura — his passivity, his inability to engage in witty conversation. If anything he seems like the victim of the gentle teasing (intended only to challenge his Tokyo perception of Hokkaido as ‘wild’.)

What to make of the initial misunderstanding?

“My brother tells me that your wife recently passed away,” Keiko Sasaki said, with a respectful expression.

Komura waited a moment before answering, “No, she didn’t die.”

The polite word for ‘to die’ in Japanese is homophonous with ‘to disappear’. Japanese language is chocka full of homophones (to do with borrowing a lot of language from China centuries ago, but losing the tonal distinctions).

The die/disappear misunderstanding could easily happen in conversational Japanese, though in written language the distinction is clear:

無くなる (nakunaru) means to disappear.

亡くなる (also pronounced nakunaru) means to die.

I therefore suspect that an English reader would make more of this confusion than a Japanese reader? Or maybe it’s easier for English readers to pick up the deliberate confusion. Lorrie Moore is another short story writer whose characters mishear each other, and because conversations are entirely fabricated, these are never accidental details. In “Which Is More Than I Can Say About Some People”, Lorrie Moore creates a mother who mishears ‘people’ for ‘peepers’. This has significance in the story.

In this story, the misunderstanding emphasises how similar divorce and death can feel to the left-behind person. To Komura there is no emotional difference. He is a grieving man.

STORY STRUCTURE OF U.F.O. IN KUSHIRO

This is classic mythic structure: A character leaves home to embark upon a mission of some kind. Along the way he meets allies and opponents, and leaves knowing something about himself. This is an ancient story, at least as old as “The Odyssey”. Contemporary writers play with it a bit: The ‘hero’ is sometimes a passive, unremarkable guy, a low mimetic hero (to use the terminology of Northrop Frye).

PARATEXT

“U.F.O. in Kushiro” appears in a collection of post-earthquake stories, all six from the same author.

SHORTCOMING

A passive main character who sunk so fully into marriage that he seemed to lose vitality for life.

In line with Murakami’s reputation as a writer, this guy is going to experience a revelation, guided by a female ‘oracle’ (or witch) character.

I don’t think any of my characters are that complex.

Haruki Murakami

DESIRE

As a typical passive main character, he only wants things to stay exactly the same. It’s up to the cast around him to drive the action.

OPPONENT

The unseen opponent is Komura’s wife, who has left him. We don’t hear a thing from this wife, only from her mother, and so the reader is not let into the veridical situation between them, but forced to deduce.

My deduction comes from observing Komura with the women in Hokkaido, who are his next opponents in a subtle way, mainly because their upbeat attitude juxtaposes aginst Komura’s sadness. Later in the evening, one of them becomes a sexual partner and this scene is what will bring Komura close to ‘spiritual death’.

PLAN

His friend in Toky has given him a mission: Take a small package up to his sister in Hokkaido. He does not tell Komura what’s in the box; this is irrelevant. Komura does as he is told, and takes a week’s holiday up there while he’s at it.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

Shimao, who has arranged the evening so that she ends up in bed with Komura, is a contemporary witch-like character. Like a witch you might find in a cabin in the woods, she tells him a story about a time she had sex with her boyfriend (in the woods). To keep bears away, they kept ringing a little bell the entire time.

After ‘failed’ sex (by the traditional definition of ‘sex’), Shimao elicits from Komura the personal information of what his wife wrote for him in her Dear John letter. Komura tells her that his wife called him ‘a chunk of air’.

Shimao appears to take the Mick by refusing to tell him what was in the box he delivered, using his own words back on him; she tells him the box contains a chunk of air.

ANAGNORISIS

The shift that happens for Komura: He suddenly does something of his own volition, without being told to do it.

When discussing this short story at The New Yorker, Bryan Washington and Deborah Treisman note that when the main character stops being passive, he is filled with thoughts of violence. Treisman suggests this is good — finally he’s his own person. Washington doesn’t feel the same rush of pleasure at seeing a character swing from extreme passivity to violence.

NEW SITUATION

This narrative is a great example of a (post-Chekhovian) short story with two different kinds of closures. Charles E. May speaks of ‘dramatic’ versus ‘aesthetic’ closures.

There is no dramatic (plot) closure, because we never find out what was in the box. However, there is aesthetic closure, because “hard matter” has been transformed “into metaphor … resolved only aesthetically.”

Stories of this kind lean hard against symbol webs, metaphors, motifs. The earthquake is clearly a symbol for relationship rifts. The box of nothing requires more considered interpretation from individual readers. (Motifs always do, unlike universal symbols which are… universal.)

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

What do I make of that box of nothing? I’m thinking of other short story writers who use small boxes as motifs. A notable example is “Prelude” by Katherine Mansfield. In “Prelude”, a family moves house. (Another mythic journey, only this time the ‘home’ at the end is a new one.) We see Mansfield’s world largely through young Kezia, and small containers of various kinds function as a motif: hold-alls, bags, boxes, stay-buttons, a high box border, box edges, a matchbox, a pillbox.

In “Prelude”, this box motif is all about restriction and closure. Kezia also happens to be preoccupied with death, partly because her beloved grandmother seems to be getting so old.

Whaddayaknow, this character in “U.F.O. in Kushiro” is also kind of preoccupied with death. He experiences violent thoughts when Shimao refuses to tell him what’s in the box. Earlier in the story, he experiences the disappearance of his wife as a “prelude” to death. The box itself on-the-page reminds him of death: “[the friend] handed Komura a box like the ones used for human ashes, only smaller, wrapped in manila paper.”

The box “weighed almost nothing”. I think this is a visual representation of existential* crisis. What is life for, if not to get married and stay married (thinks the main character, right after his wife leaves him). In Japan, the married life garners the most respect. To become (or remain) unmarried carries very real consequences for men in the workforce.

*Existentialism: an outlook which begins with a disoriented individual facing a confused world that they can’t accept. Existentialism’s negative side emphasizes life’s meaningless and human alienation. Think: nothingness, sickness, loneliness, nausea.

I’m reminded of a scene from Kill Bill vol, 2 which, only be coincidence, is also set in Japan. For me, the box motif running through “U.F.O. in Kushiro” is very similar to the box motif running through Katherine Mansfield’s “Prelude”: Something to represent that feeling you get when you feel your life has constricted, a highly unplesant funnel-y feeling which leads you in only one direction: straight towards death.

But this box/constriction motif also about that fear of being buried alive, probably.

I take great care not to dwell too much on the meaning of existence, its importance or its implications.

Haruki Murakami, who uses motifs for the job, instead.

RESONANCE

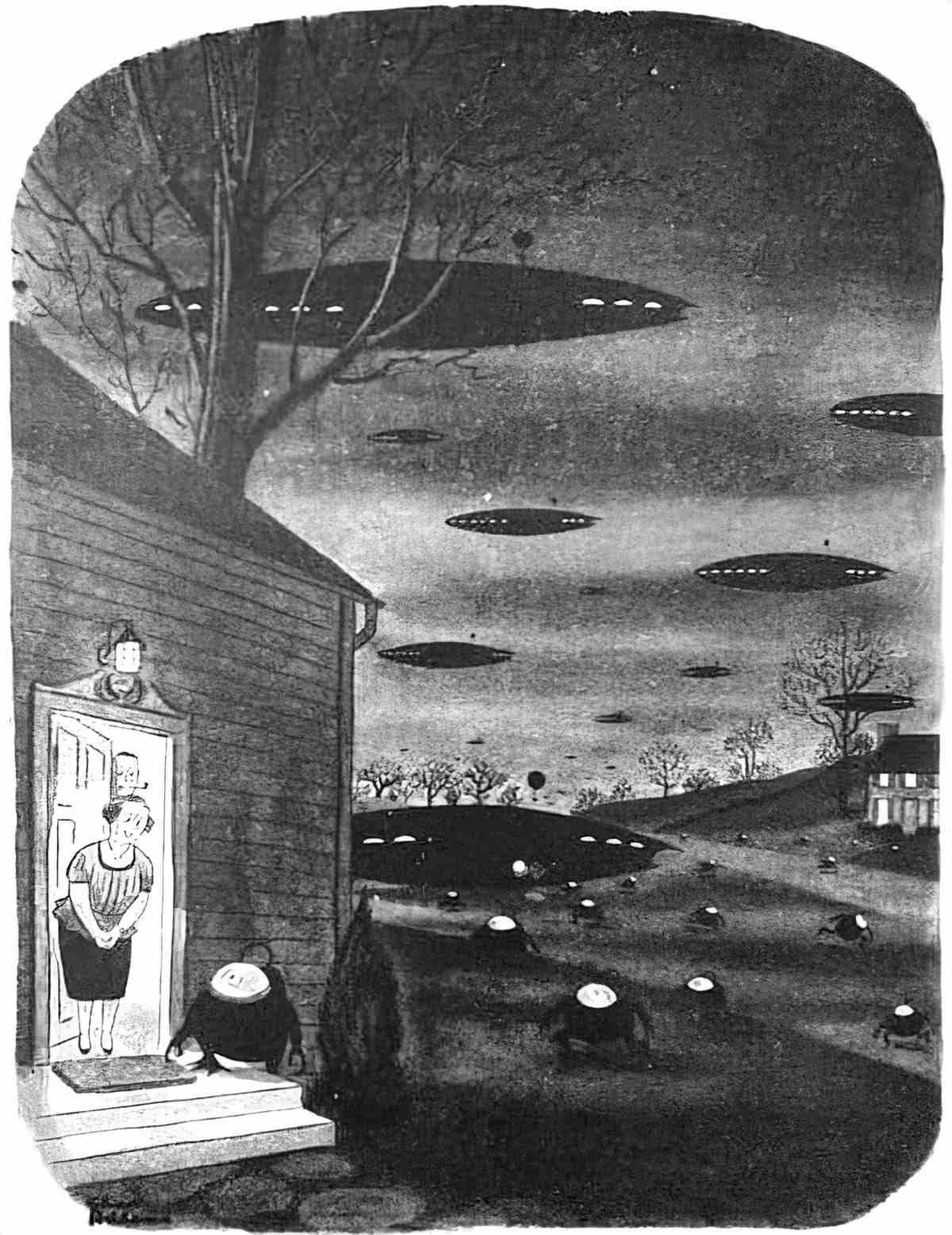

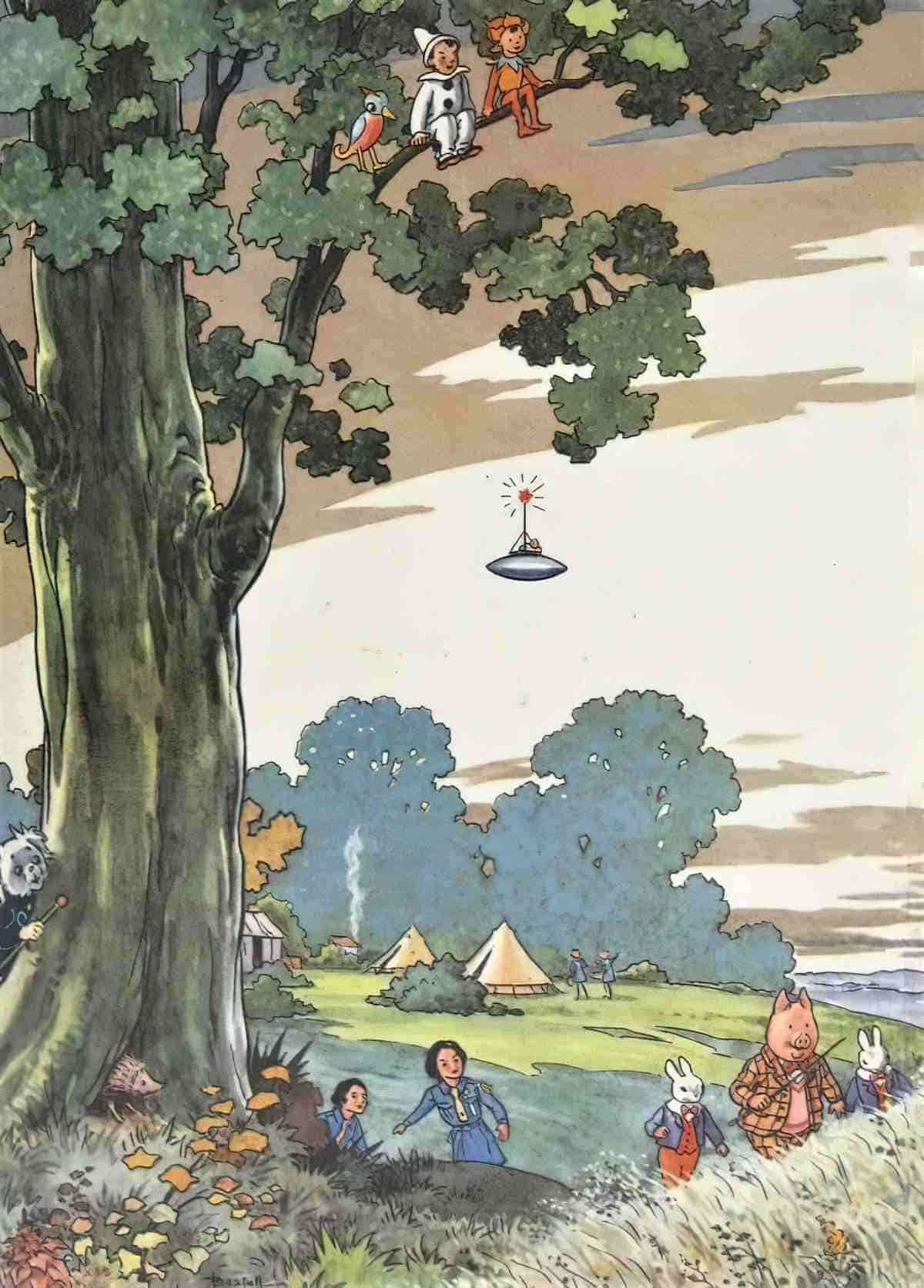

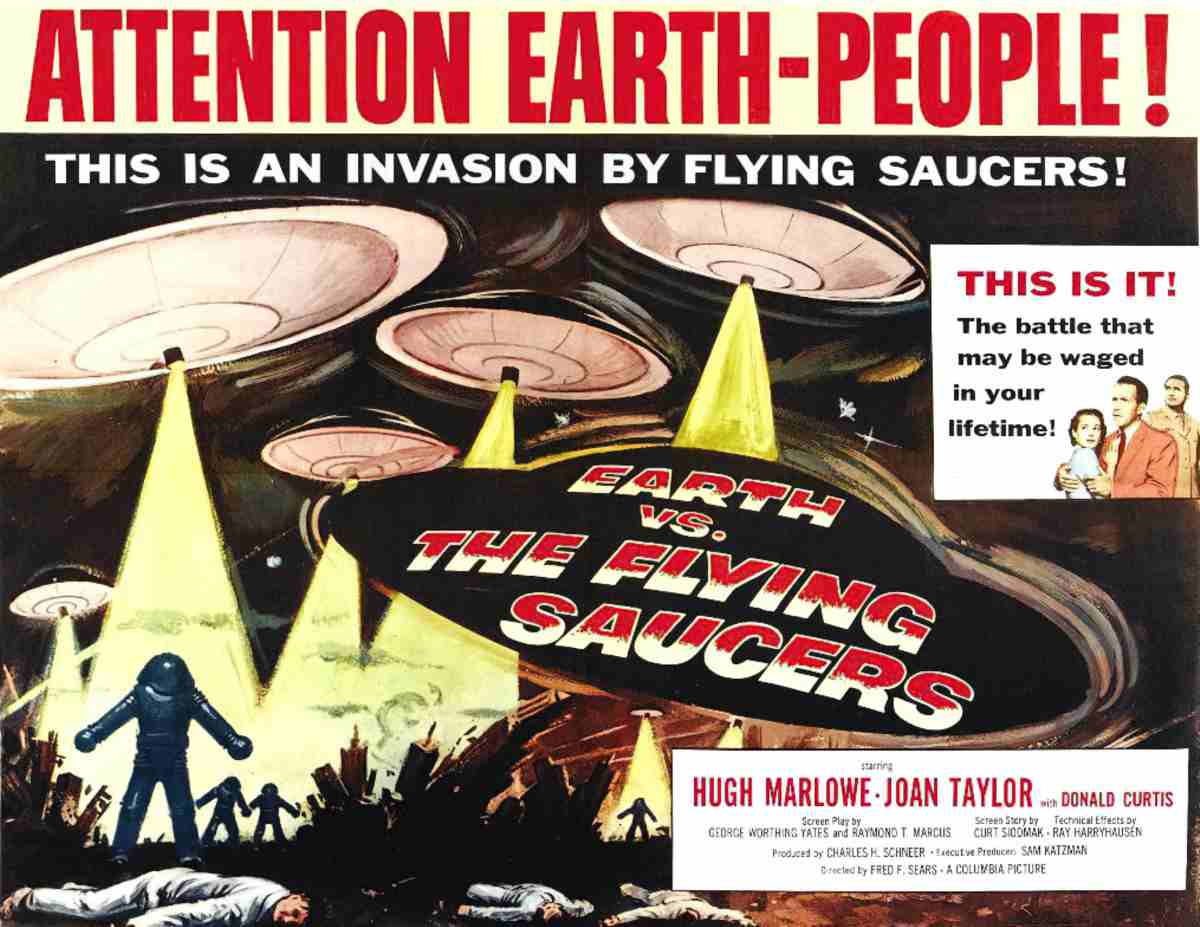

Legends of U.F.O. sightings are so well-known the world over that they can be utilised for various purposes, including non-SF, lyrical short stories such as this one.

Below is a small collection of U.F.O.s in illustration. My favourite are the scenes in which U.F.O.s appear in otherwise completely mundane scenes.

ALIENS IN JAPAN

If anyone is disappointed because this story did not feature UFOs in Japan, read a VICE article called Inside a Dying Japanese Town Obsessed With Aliens by Hanako Montgomery

FOR FURTHER INVESTIGATION

The Forbidden Worlds of Haruki Murakami

In an “other world” composed of language—it could be a fathomless Martian well, a labyrinthine hotel, or forest—a narrative unfolds, and with it the experiences, memories, and dreams that constitute reality for Haruki Murakami’s characters and readers. Memories and dreams in turn conjure their magical counterparts—people without names or pasts, fantastic animals, half-animals, and talking machines that traverse the dark psychic underworld of this writer’s extraordinary fiction.

Fervently acclaimed worldwide, Haruki Murakami’s wildly imaginative work in many ways remains a mystery, its worlds within worlds uncharted territory. Finally in The Forbidden Worlds of Haruki Murakami (University of Minnesota Press, 2014), Matthew Carl Strecher provides readers with a map to the strange realm that grounds virtually every aspect of Murakami’s writing. A journey through the enigmatic and baffling innermost mind, a metaphysical dimension where Murakami’s most bizarre scenes and characters lurk, The Forbidden Worlds of Haruki Murakami exposes the psychological and mythological underpinnings of this other world. The author shows how these considerations color Murakami’s depictions of the individual and collective soul, which constantly shift between the tangible and intangible but in this literary landscape are undeniably real.

New Books Network

All About U.F.O.s from The Folklore Podcast