You’ve probably heard of foreshadowing, but have you heard of back-shadowing and side-shadowing? These techniques have nothing to do with each other, other than that they all describe literary techniques and they all include ‘shadowing’ in the term.

That said, each of these devices demonstrates a way of displacing the idea of temporal linearity in fiction.

FORESHADOWING

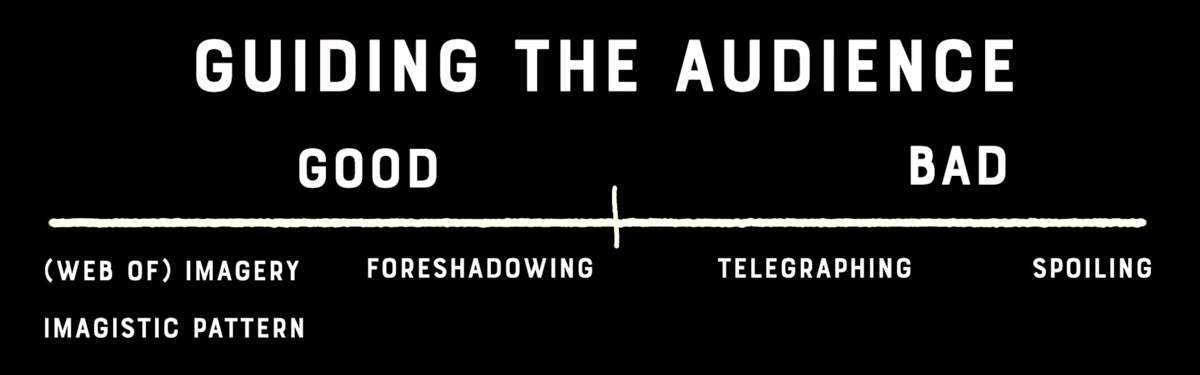

Foreshadowing is a literary device. An author drops subtle hints about plot developments to come later in the story. Foreshadowing exists on a continuum, with ‘spoiler’ at the far end and ‘telegraphing’ between the two.

Telegraphing is foreshadowing done badly. If a storyteller goes for foreshadowing but accidentally winds up telegraphing, this means readers can predict what is about to happen, even though the author doesn’t want them to.

Foreshadowing is especially popular in Western storytelling, but less common in, say, Asian storytelling.

I’ve been thinking about how much Western storytelling trains us to expect that writers show the audience where they’re going right up front. Main characters have to be introduced right away. Twists have to be foreshadowed. Inciting incident in the first 10% etc.

BUT Many of my favorite stories, especially Asian ones, don’t adhere to these “rules.” In My Neighbor Totoro, Totoro doesn’t appear until 30 mins into a 90 min film. The slow sense of discovery makes the film enchanting. Can you imagine any American film waiting until the 33% mark?

If the film Parasite had been an American movie, there would all sorts of clues, hints, bumps in the night. Or maybe the movie would’ve ended with the rich and poor families having a showdown and then reconciling. As it is, when the twist comes, it’s truly a shock.

Yet, it makes perfect sense and re-contextualizes everything. It’s been thematically foreshadowed but NOT literally foreshadowed. Not an Asian film, but there’s a similar OMG WTF moment in Sorry to Bother You that works precisely because it *hasn’t* been foreshadowed.

@FondaJLee

FRONTLOADING

Related to foreshadowing: ‘frontloading’:

As a former debater, I was taught, “Tell them what you’re going to tell them, tell them again, tell them what you told them.” Front loading (or hinting at) all your narrative cards upfront is a storytelling tradition couched in cultural assumptions and not really a rule at all.

@FondaJLee

Foreshadowing doesn’t just apply to red herrings (in mystery) and to meaningful dialogue and to characters who didn’t seem important before but do now. A mood can also be a form of foreshadowing:

In film, feeling is known as mood. Mood is created in the film’s text: the quality of light and color, the tempo of action and editing, casting, style of dialogue, production design, and musical score. The sum of all these textural qualities creates a particular mood. In general, mood, like setups, is a form of foreshadowing, a way of preparing or shaping the audiences, anticipations. Moment by moment, however, while the dynamic of the scene determines whether the emotion it causes is positive or negative, the mood makes this emotion specific.

Robert McKee, Story

POINTER

Will Dunne uses the term ‘pointer’ in his 2009 screenwriting workbook The Dramatic Writer′s Companion – Tools to Develop Characters, Cause Scenes, and Build Stories.

A pointer describes something in a story which subtly guides an audience in the direction the writer needs them to go. Generally, a pointer indicates things are about to go wrong. (But in stories, doesn’t something always go wrong?) Chekhov’s gun is a pointer.

Unlike in foreshadowing, even the least symbolically astute member of the audience is aware of the pointer on a conscious level.

that some people respond to any well-foreshadowed reveal with “ugh that plot twist was so predictable” proves bad faith criticism has rotted their brains to the point they think it’s bad writing if they can correctly identify information the writers were intentionally giving them

bloodraven55

Dunne also uses the word ‘plant’, possibly to avoid the annoying conversation about whether something in a story is allowed to be called ‘foreshadowing’ or not if it’s not metaphorical. This is something we only understand in hindsight. Literary academics use the term ‘delayed decoding’ and, as far as I can work out, both of these terms describe the exact same technique. A plant is what the writer does; delayed decoding describes an audience experience.

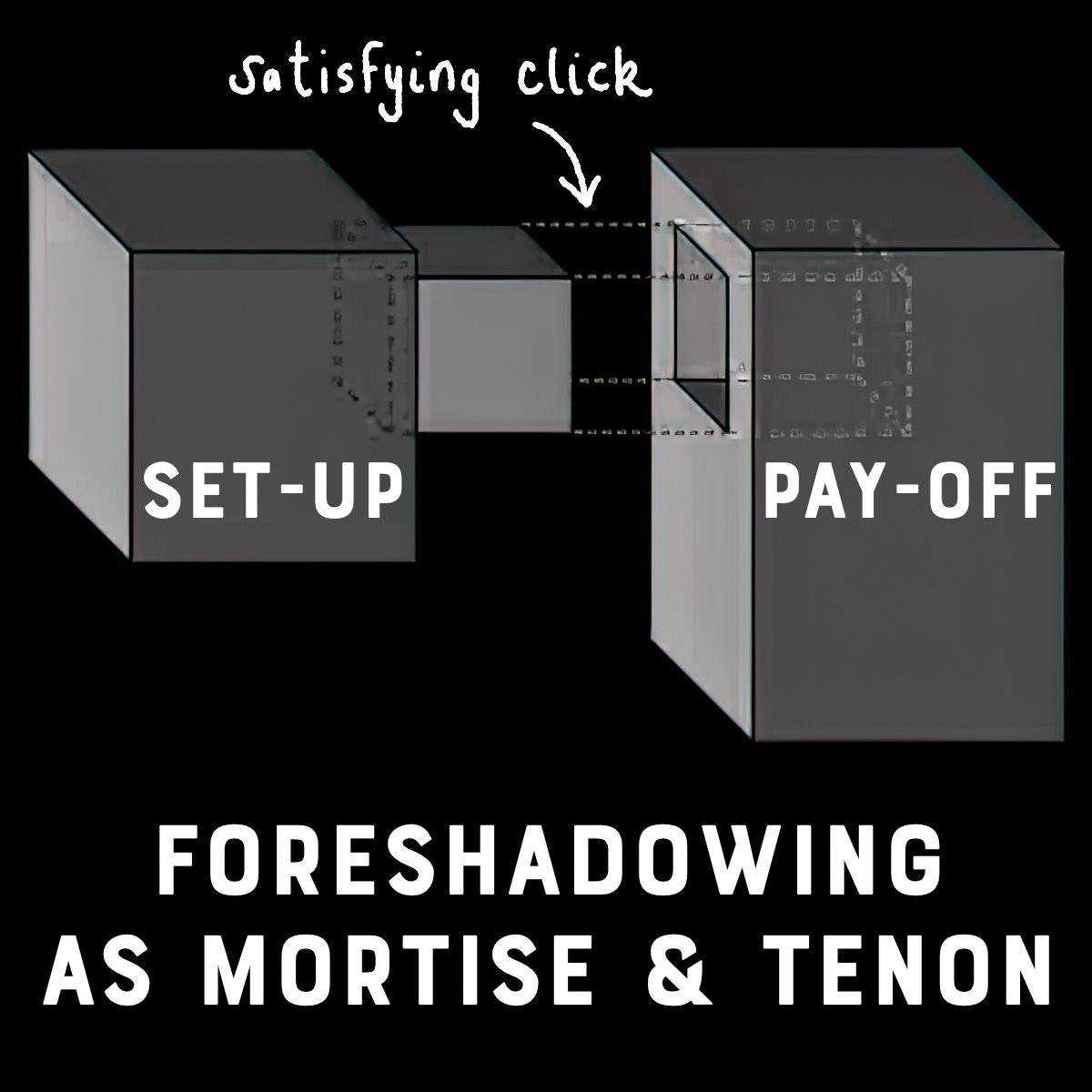

Specifically, Dunne’s ‘plant’ creates a joyous, satisfying click in the audience.

THE FRIDGE TEST

This is Alfred Hitchcock’s term, and relates to delayed decoding. This describes the moment you realise something in a movie didn’t add up. You’re gazing into the fridge looking for something to eat or drink.

“You know. You’ve just come home from a movie, you had a great time, you go to the refrigerator to get a beer, you open the door, and you say, ‘Wait a minute …’” If a film has got the audience until they open the fridge, maintains [director Jonathan] Demme, then that’s all that matters.

So Rose Could Have Saved Jack In Titanic — So What, It Still Passes The Fridge Test, The Guardian

(The article also explains that the refrigerator test is a modification on Alfred Hitchcock’s ‘icebox question’.)

FLASHING ARROW

Speaking of things going wrong in screenwriting, the film industry word for really obvious pointing is the ‘flashing arrow’.

A flashing arrow is a metaphorical audio-visual cue used in films to bring some object or situation that will be referred later, or otherwise used in the advancement of plot, to the attention of the viewers.

This technique is parodied in the 1981 film Student Bodies, which literally makes use of a flashing arrow to ‘telegraph’ to the audience that when the vulnerable young woman alone opened the front door, then forgot to lock it again.

What is Foreshadowing?

WHAT FORESHADOWING IS NOT

People mean different things when they use literary terms. Academics deep dive into the nitty-gritty of texts. Fiction writers are interested in terminology onto insofar as it helps craft. Screenwriters are a separate subgroup of writers with their own terminology again.

It’s easy to conflate three separate but similar things: set-up, foreshadowing and what we might call the ‘symbolic web’, imagistic patterning, or just ‘imagery’.

Let’s go to the core, literal meaning of ‘foreshadow’. Imagine an illustration or photo. A shadow drops into the frame, but you can’t see what’s causing it. The reader can see something, but probably won’t notice it. We don’t tend to notice shadows.

Foreshadowing works in the same way advertising works. Advertisements work better the less attention we pay to them. (That link is to the Factually podcast, How to Do Nothing with Jenny Odell”.) It is there to guide the audience, but in a way the audience won’t notice at the time.

A really common type of foreshadow: A small animal dies (often a rodent or a cockroach). Later, a human dies. This is so common I don’t even know how it still works to surprise us.

CHARACTERS DON’T PICK UP FORESHADOWING

We notice instances of foreshadowing in literature where we would not suspect it in real life. Nothing in a story lacks a purpose, or it wouldn’t be there. (See Chekov’s Gun.) But events in real life cannot be foreshadowed, despite certain cognitive biases which encourage us to retrofit past events to make sense of subsequent ones. Foreshadowing is a specifically literary construction. However, the novel opening below goes for realism by pointing out a lack of foreshadowing. Although the narrator tells a crafted story, the reader is to believe it all really happened:

If I’d known I was about to meet the man who’d shatter me like bone china on terra-cotta, I would have slept in. Instead, I roused our florist, Mr. Sitwell, from his bed to make a boutonnière. My first consulate gala was no time to stand on ceremony.

I joined the riptide of the great unwashed moving up Fifth Avenue. Men in gray-felted fedoras pushed by me, the morning papers in their attachés bearing the last benign headlines of the decade. There was no storm gathering in the east that day, no portent of things to come. The only ominous sign from the direction of Europe was the scent of slack water wafting off the East River.

Lilac Girls by Martha Hall Kelly (2017)

Importantly, foreshadowing is not visible to the characters, as it’s not visible to us until we’ve reached the end of the story.

Exception: Such obvious foreshadowing in Doubt (2008) that Meryl Streep’s character comments on it and basically names it as a literary technique. For Sister Aloysius not to comment on it would make her seem silly. Also, it works because she is a teacher.

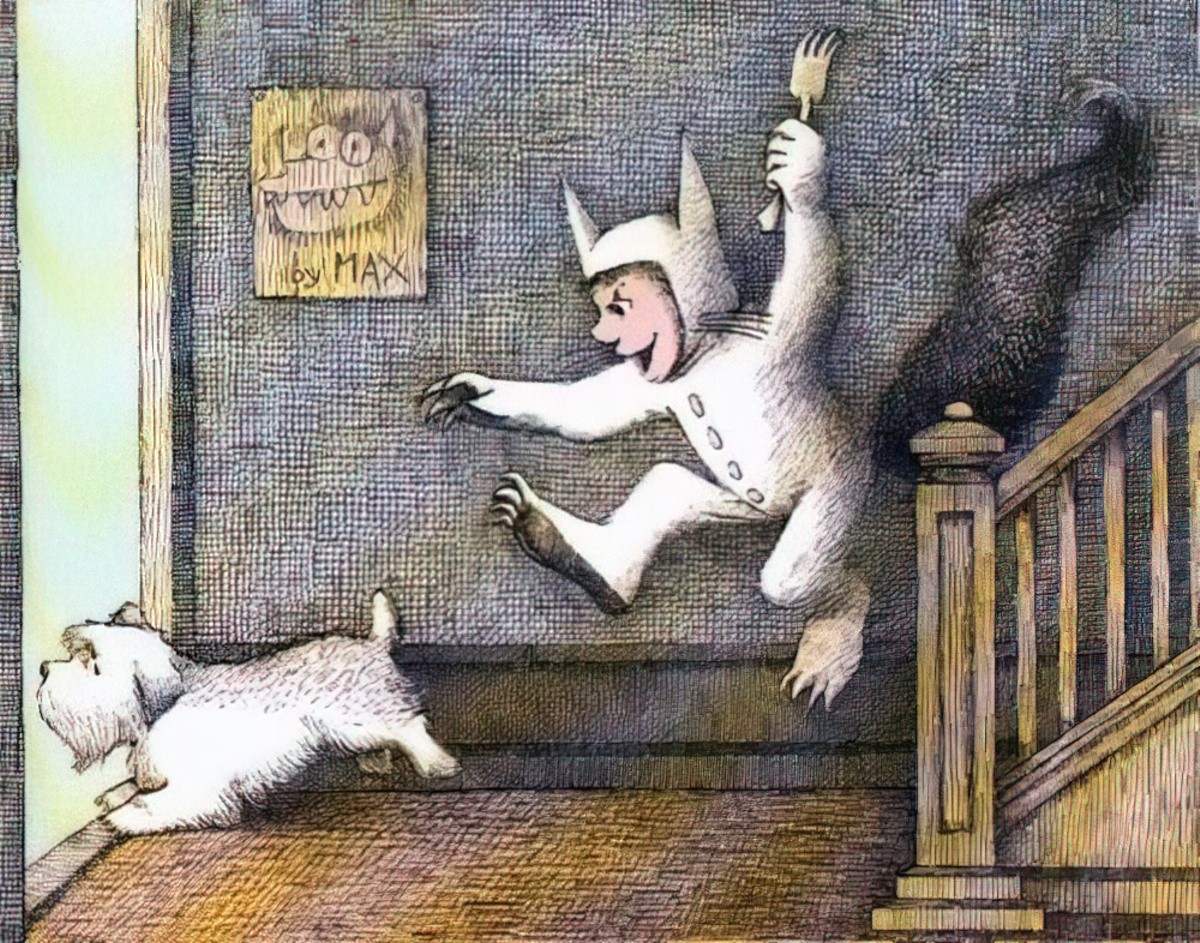

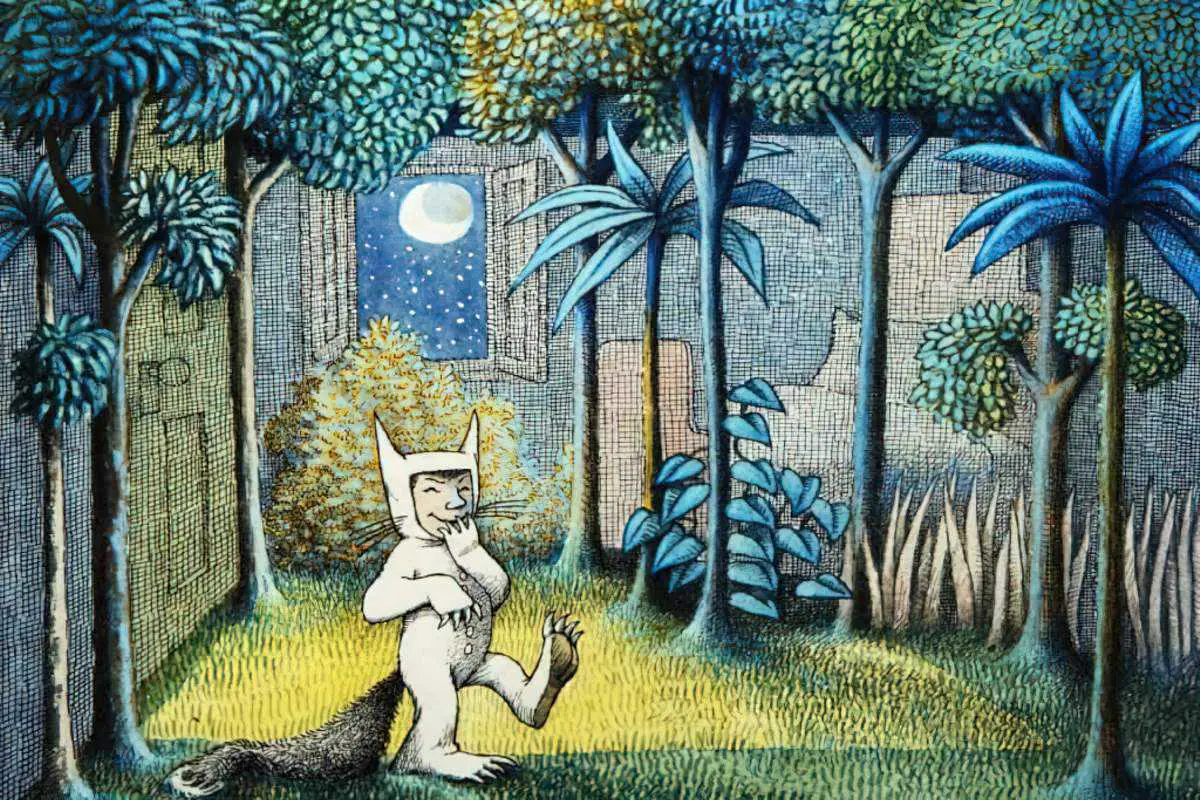

In picture books, foreshadowing can happen in the illustrations. Take, for example, the drawing of the Wild Thing at the bottom of the stairs in Where The Wild Things Are. Upon second reading, the reader knows that Max has been creating these wild things in his imagination.

What is foreshadowing used for?

Foreshadowing imparts the feeling that everything in a story is ‘tied-together’. It avoids an episodic feeling. (For writers crafting episodic stories, foreshadowing and imagistic patterns are super important.)

Foreshadowing (and its close relatives) provides a sense of closure and satisfaction at the end of a story or scene. Foreshadowing also helps audiences avoid the feeling of deus ex machina. This describes the feeling that something has suddenly swooped in to save the day (originally in stories from antiquity it was God, and in poorly executed children’s literature, an adult).

Foreshadowing provides the re-reader with extra insight, so rewards a repeat experience.

Foreshadowing can add dramatic tension by building subconscious anticipation about future events. It can also help build a creepy/suspenseful atmosphere.

All together, foreshadowing contributes to verisimilitude. Note the irony in that, since foreshadowing doesn’t happen in real life.

11 Clever Moments of Movie Foreshadowing You Might Have Missed from Mental Floss

PREFIGURATION

Another similar verb to ‘foreshadow’ is ‘prefigure’.

Prefiguration is the act of providing vague advance indications. Because this word is frequently used in relation to the Bible, the difference between ‘to prefigure’ and ‘to foreshadow’ is mainly around religious connotation. ‘Prefigure’ can have a bit of a prophetic feel to it.

FOREORDINATION

Sticking with the religious words, I’ve seen literary specialists talk about foreordination and wondered why they chose that word and not ‘foreshadow’.

Foreordination is mostly contrasted against predestination. The two are part and parcel in certain Christian writings. Predestination refers to what God has already decided for you. Foreordination doesn’t strip you of free will, but is basically the same thing otherwise. Say you’ve been foreordained to eat mac and cheese this evening, you can always choose not to, even though that’s your proper calling, so to speak.

An example of “foreordination” in the field of literature: It has been said that the beginning of an Alice Munro short story will foreordain the ending. Basically, if you read an Alice Munro short story, the ending will seem both inevitable and surprising. Inevitable because once you go back to the beginning, you can see how the writer (god of the story events) set things up to go in the direction they did.

SET-UP AND PAY-OFF

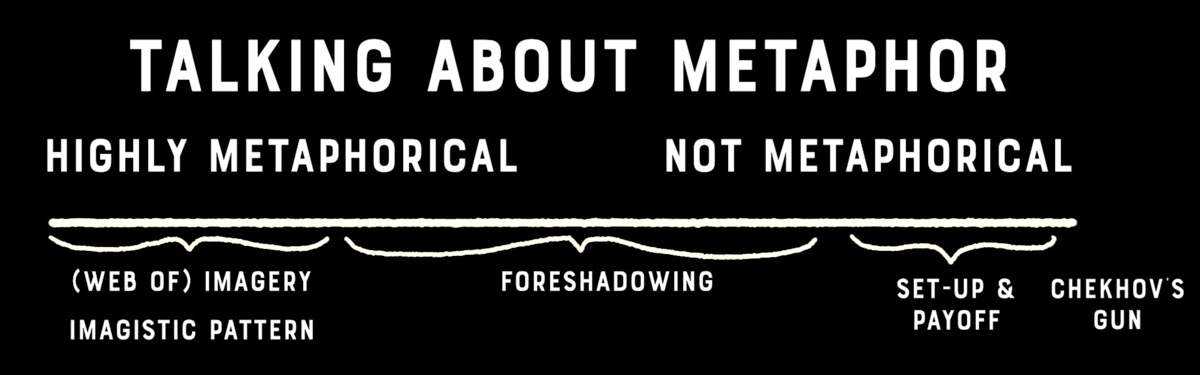

Borrowing from the language of comedy, the parts of story snap together like LEGO. I like the analogy of ‘mortise and tenon’, a type of carpentry joint. Sometimes, foreshadowing takes this form. If it’s more metaphorical, it’s more likely to be called ‘foreshadowing’. If it’s something concrete and is more noticeable, it’s more likely to be called ‘set-up and pay-off’.

There’s no hard line separating these two concepts, but here’s the difference: If you see it happening on first read, it’s set-up. If you only understood it on second read, it’s foreshadowing. Foreshadowing is metaphorical. Set-up and pay-off is structural. The writer introduces a character early because they reappear later on.

The reason why symbolism and motif is not foreshadowing: Imagery is a lacy spider’s web, hanging over the story, weaving parts together at a separate layer from plot. At the other end of that spectrum we have plain old set-up and pay-off (think Chekhov’s Gun) but in between those two we have foreshadowing, which is ‘metaphor with a pay-off’.

Imagery is not a two-part thing. Imagery comprises many techniques, including simile, metaphor, motif, symbolism and so on.

But with foreshadowing, as with set-up and pay-off, something happens early in a story which functions as a set-up. Crucially, the audience doesn’t realise this something will be working one both a plot level and at a metaphorical level. They won’t know this until they have learned the entire story. They may still not know unless they step back and reflect. Foreshadowing is not the one, two punch which is Chekhov’s gun going off, or the start of a joke and its punchline.

I find it fascinating that this mortise and tenon, two-part metaphor holds true for communication at the micro (sentence) level as well as at the macro (storytelling) level. Here is linguist Dr Mark Ellison talking about how we know something has gone wrong in a conversation:

If you can kick off language by having these messy, overlapping semantic units put together — and they have to match up — what happens is, when you start to break things a little bit, making metaphors, we found that there’s a requirement that both bits of the metaphor, both of the bits that cause a break, have to be present, have to be said explicitly. Even in languages where you can leave out anything.

Because Language podcast, 3 January 2023 (For more on that, listen to the fascinating podcast.)

We might also talk about ‘setting stuff up so we’re allowed to use it later’. For example, in the TV show Happy Valley, Season Three, the plot required the use of a game station. This game station was mentioned ‘in passing’ before it was needed to instigate the climax. If the game station hadn’t been mentioned, audiences would have been left a little discombobulated or distracted by the brief thought: “I didn’t know he had a game station.”

Rule of thumb: If something is required for the climax to work, slip it in early. Ideally do it in such a way that the audience barely notices this thing, because the scene is really about something else.

I’ve talked about two spectra. They look like this:

FORESHADOWING TIPS FOR WRITERS

Don’t expect to be including foreshadowing in first drafts. Foreshadowing happens once you know where the story is going.

Recognise what’s likely to be interpreted as a foreshadow or a set-up. If you kill a mouse early on, the audience will be subconsciously expecting death. (The concept of Chekhov’s Gun is pertinent in this discussion — the most obvious form of prop foreshadowing.)

Your beta readers shouldn’t be able to predict what’s going to happen based on foreshadowing. If they can, you’ve been too heavy-handed. That would be called telegraphing, or spoiling. Caveat: If you’re writing for kids (not for a dual audience, for kids) there are things kids won’t pick up which adult beta readers will. That’s because kids, by definition, haven’t spent as much time in the world and haven’t the experience to recognise patterns of story.

BACKSHADOWING

Writers don’t use this term. If writers think in terms of set-up and pay-off, the set-up might be ‘the foreshadow’ and the pay-off would be ‘the backshadow’. The term isn’t really necessary in relation to foreshadowing, because we’re only reversing directionality.

However, others use the word ‘backshadow’ to describe something else. This word is not related to the writerly process of guiding an audience via metaphor. It describes audience experience.

What is backshadowing?

Backshadowing is the technique of inserting commentary into the present narrative that refers to earlier narrative events. For example, a child in a story lives in present-day Germany. The child discovers she is a descendent of a war criminal. In order for such a narrative to make sense to a reader, the reader must know something about Germany and the world wars.

Backshadowing is visible to readers as well as to characters. Everyone knows what happened, and the story rests upon this shared schema. Neither narrator nor narratee is in superior or inferior position.

In this sense, the word backshadowing is related to intertextuality. The reader brings extratextual knowledge into the story from their own life experience.

What is backshadowing used for?

Many historians and writers of historical fiction employ backshadowing of real-world historical events because the reader already has a schema. For example, the holocaust might be used as a setting in a romance novel to allow the writer to spend time on the characters and plot. (This can be problematic.)

BACKSHADOWING AND PROBLEMATIC DETERMINISM

In his book Foregone Conclusions: Against Apocalyptic History, author Michael Bernstein criticises authors who use their own and their audience’s knowledge of an apocalyptic event which occurs after the epoch about which they are writing to interpret the actions of their real or imaginary characters.

Bernstein’s main problem with backshadowing: this technique encourages a reader to believe in determinism — that whatever happened in the past led inevitably to the present we know.

CHRONOCENTRISM

Related to this usage of ‘backshadowing’ is the cognitive bias ‘chronocentrism’. This word describes the natural human tendency to see one’s own time/era/generation as more special than others.

The term backshadowing was coined by Bernstein. See his book: Foregone Conclusions: Against Apocalyptic History.

THE EFFECT OF BACKSHADOWED STORIES

The character in this kind of story is likely to interpret their own current (fictional) reality according to whatever happened in the past. In first person narratives where the character is the intradiegetic first person narrator, the very act of storytelling becomes the main focus rather than the events themselves. The narrator’s main role is ‘artist’.

ANOTHER EXAMPLE OF BACKSHADOWING IN USE

Another, completely different use of the word backshadowing describes a plot shape. The writer starts a story with its ending, then shifts back to the beginning with the reader in full knowledge of the outcome, but no idea how it all happened. The rest of the story fills the reader in.

This technique allows the writer to use a climactic event as a hook, drawing in the reader with the promise of something big and interesting to come.

In this case, ‘backshadowing’ is a subcategory of a flashback. It’s not a widely-used term.

I have also heard people talk about backshadowing and foreshadowing as alternative words to describe that mortise-and-tenon click audiences get from set-up and pay-off deftly done. However, I prefer not to use backshadowing in this way. I suspect this use came about because, if someone already knows the word ‘foreshadowing’, by deduction, the word ‘backshadowing’ would seem to mean the other half of that.

SIDESHADOWING

Soundtrack for this section: Possibility by Lykke Li

What is sideshadowing?

A character or narrator posits a series of possible, hypothetical or imaginary events which never have any consequences in the story.

Side-shadowing is a literary device which presents alternative scenarios to the reader. Side-shadowing is about possibility. It’s the narrative, scene-ified equivalent of subjunctive mood.

We are naturally inclined to imagine alternative realities. One thing you may notice about being middle aged is the tendency to look at the people you grew up with and compare their lives to your own, imagining that if you’d made those same decisions, you’d have that life over there. Tim Kreider calls this comparison “The Referendum”. He also describes a sort of real life side-shadowing:

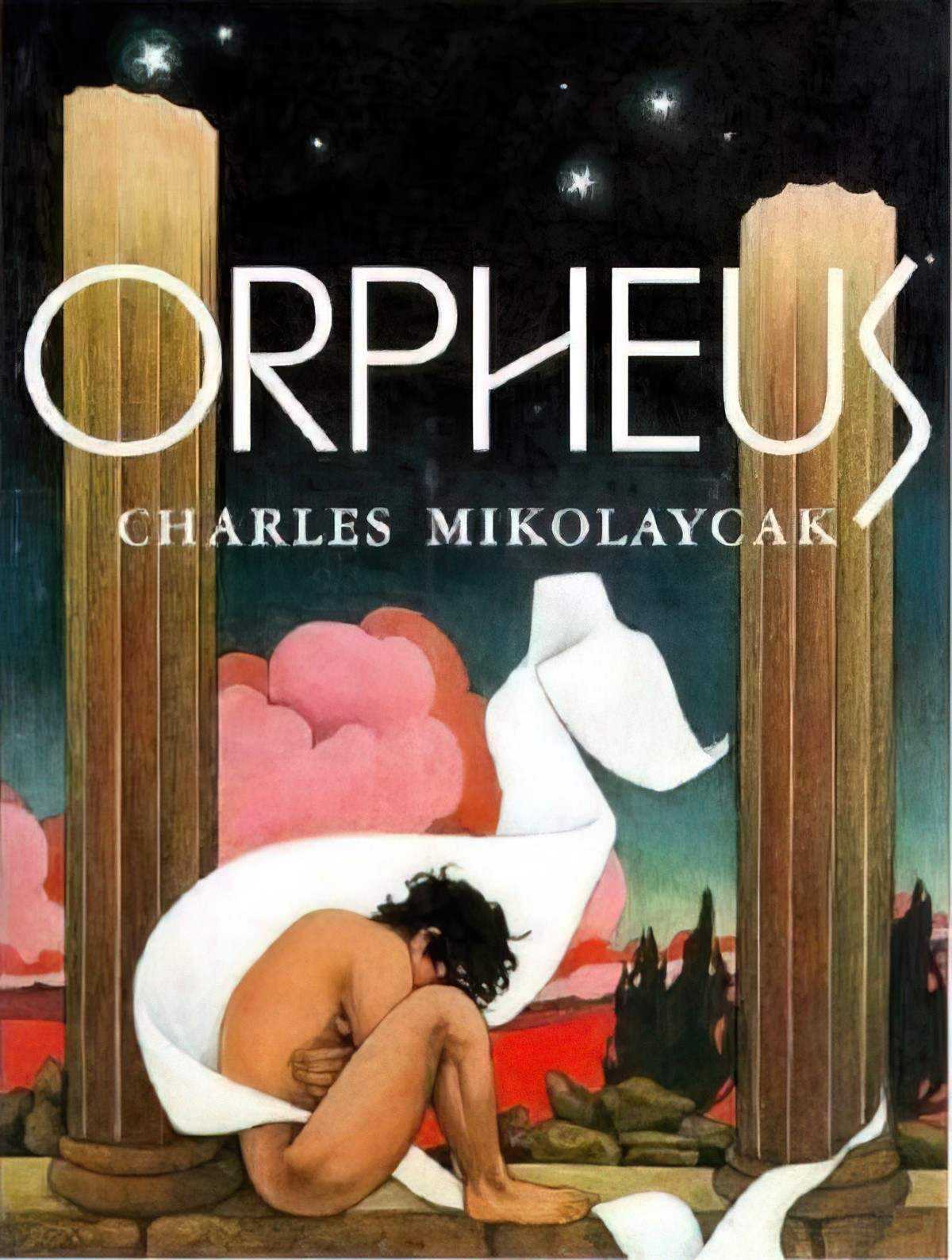

One of the hardest things to look at is the life we didn’t lead, the path not taken, potential left unfulfilled. In stories, those who look back—Lot’s wife, Orpheus—are irrevocably lost. Looking to the side instead, to gauge how our companions are faring, is a way of glancing at a safer reflection of what we cannot directly bear, like Perseus seeing the Gorgon safely mirrored in his shield. It’s the closest we can get to a glimpse of the parallel universe in which we didn’t ruin that relationship years ago, or got that job we applied for, or made that plane at the last minute. So it’s tempting to read other people’s lives as cautionary fables or repudiations of our own, to covet or denigrate them instead of seeing them for what they are: other people’s lives, island universes, unknowable.

Tim Kreider, We Learn Nothing

But of course, we don’t call this side-shadowing. We only call it something when it happens in literature. Often, it’s extremely sad.

AN ENTIRE GENRE OF LITERARY SIDESHADOWING

Authors who fill in historical gaps propose a history which we know did not exist, but which we can imagine might have existed.

An excellent example from children’s literature (recommended by a history expert on the Romans): The Eagle of the Ninth by Rosemary Sutcliffe. This is a historical adventure novel for children written by Rosemary Sutcliff and published in 1954. The story is set in Roman Britain in the 2nd century AD, after the building of Hadrian’s Wall.

What is sideshadowing used for?

Moral Luck: Say you drink & drive and get home safely. Now imagine you do the same thing but someone crosses your path and is hit. In both cases you acted exactly the same way, but in one case, through no fault of your own, you’re deemed to have committed a far greater crime.

@G_S_Bhogal

Sideshadowing draws attention to the possibility that other paths could have been taken. Sideshadowing suggests to a reader that one must grasp what else might have happened in order to fully understand an event.

The technique suggests to readers that time is not a fatalistic line but a shifting set of possibilities.

Sideshadowing suggests that nothing can be wrapped up neatly, if at all.

In other words, sideshadowing is used to give a contrasting illumination to the ‘real’ event. Oftentimes, the contrast is that in the side-shadowed section of the story, the character makes a different moral decision. Side-shadowed section work like subplots: They’re of most use when they explore various moral decisions made by the characters.

While foreshadowing and (especially backshadowing make the present and future seem inevitable, emphasising fate, sideshadowing emphasises the contingency of the present.

Sideshadowing points outside the narrative, deliberately suggesting to the reader that more things might be going on than what’s expressed in the story.

In children’s literature, there’s a good example of sideshadowing in Johnny, My Friend:

Let’s turn the clock back, Johnny! […] We’ll take the Alternative where […] you can have a home, Johnny, not just a bit of a smelly monster’s den, and a name, Johnny, you can have an English mum and a Swedish dad and a French sister, and me as a brother, and regular pocket money […]

Unfortunately, some people take the sophisticated human ability to imagine other scenarios and use their side-shadowing gifts for ill.

This is a character visualising a series of alternative events that never happened in the story. (See Maria Nikolajeva’s From Mythic to Linear: Time in children’s literature.)

Ann Dee Ellis uses sideshadowing in her 2017 novel You May Already Be A Winner. Here the narrator describes reuniting with her little sister after the little sister got lost. Notice the shift in mood from indicative to the subjunctive mood: ‘would’.

When I came in, I thought she’d run to me. I thought she’d cry and I’d cry and we’d hug and then I’d tell her I’m so sorry. I’m so sorry.

And then she’d hit me. And it would hurt but then we would hug and Jane the social worker and all her coworker social workers would say, “Now there’s some sisters who stick together.”

But instead, when I walked in, Berkeley didn’t look up.

I said, “Berkeley!”

And she and the boy started laughing about something.

You May Already Be A Winner by Ann Dee Ellis

Twelve-year-old Olivia Hales has a foolproof plan for winning a million dollars so that she and her little sister, Berkeley, can leave behind Sunny Pines Trailer Park.

But first she has to:

– Fix the swamp cooler and make dinner and put Berkeley to bed because her mom is too busy to do all that

– Write another letter to her dad even though he hasn’t written back yet

– Teach Berk the important stuff, like how to make chalk drawings, because they can’t afford day care and Olivia has to stay home from school to watch her

– Petition her oddball neighbors for a circus spectacular, because there needs to be something to look forward to at dumb-bum Sunny Pines

– Become a super-secret spy to impress her new friend Bart

– Enter a minimum of fourteen sweepstakes a day. Who knows? She may already be a winner!

Olivia has thought of everything . . . except herself. Who will take care of her when she needs it? Luckily, somewhere deep down between her small intestine and stomach is a tiny voice reminding her that sometimes people can surprise you–and sometimes your family is right next door.

The purpose of this is almost metafictional. Or perhaps it’s the inverse of metafictional, attempting to persuade the reader that we are not reading a story at all, but that this is the real world. In this example of side shadowing, the author describes a sort of melodrama we have in our heads about how stories goes. But because the ‘reality’ within the world of the story ironically differs from the narrative Olivia has in her head, we are reminded as readers that stories are not like the real world (even though we are actually reading a story at this very moment).

Later in the story, Ann Dee Ellis writes:

Just then, a lady collapsed. And I gave her CPR. And everyone cheered.

No I didn’t. I never do anything.

In this case the idealistic first person narrator shows us how imaginative she is, and how she aspires to be better.

In the young adult novel We Were Liars, e. lockhart uses side-shadowing when Cadence jumps from a cliff into the ocean:

I wonder if there’s another variation in which Johnny is hurt, his legs and back crushed against the rocks. We can’t call emergency services and we have to paddle back to the kayak with his nerves severed. By the time we helicopter him to the hospital on the mainland, he’s never going to walk again.

Or another variation, in which I don’t go with the Liars in the kayaks at all. I let them push me away. They keep going places without me and telling me small lies. We grow apart, bit by bit, and eventually our summer idyll is ruined forever.

It seems to me more than likely that these variations exist.

This kind of story relies on what TV Tropes calls ‘The Alternate Self’.

I doubt Sliding Doors (1998) was the first well-known story to use this structure, though it is perhaps one of the best known, since more people watch popular movies than read books. This is a plotline in which a character has a difficult decision to make. Instead of having the character choose one path, then carry on the story until a good point to stop, this kind of story decides to explore the consequences of each decision by having the character follow both paths, perhaps with alternating chapters or something quite complicated plotwise.

This kind of plot can feel quite didactic. Usually this sort of story has the following message:

However you imagine your life might have been had you made X decision instead of Y, your imagined other life isn’t as romantic/glamorous as the imagined life in your imagination.

Here are some examples of books which use side-shadowing as part of the plot. They come in all moods, all genres, all lengths. Some call it the ‘Sliding Doors’ plot, after the film.

THE POST-BIRTHDAY WORLD BY LIONEL SHRIVER (AMERICAN AUTHOR, SET IN ENGLAND, DARK)

Lionel Shriver constructs an entire plot around sideshadowing in several of her novels: Big Brother and The Post-Birthday World. This is known as a sliding-doors plot, from the movie Sliding Doors (1998).

Anyone who has read Shriver’s later (and better known) We Need To Talk About Kevin will already be expecting something quite dark. It’s what Shriver is good at. I thoroughly enjoyed this story. Shriver is an expert at plotting, as evidenced by her adept execution of this device, which is used for the end purpose of exploring long-term, stable relationships such as in marriage. The end message, for me, was that

…the story breaks into two narratives with alternating chapters: In one, Irena pursues an affair with Ramsey and leaves Lawrence; in the other, she restrains herself and stays loyal. Each choice has its downside.

Kirkus Reviews (Starred review)

I consider this book as masterful as We Need To Talk About Kevin. Don’t be fooled by the cover; the bright colours may suggest something quite different.

NORMAL PEOPLE BY SALLY ROONEY

The other, imagined life doesn’t necessarily have much substance to it. This is the case for Marianne in Normal People by Sally Rooney, in the set-up for a character who remains emotionally detached for backstory reasons:

Marianne had the sense that her real life was happening somewhere very far away, happening without her, and she didn’t know if she would ever find out where it was and become part of it. She had that feeling in school often, but it wasn’t accompanies by any specific images of what the real life might look or feel like. All she knew was that when it started, she wouldn’t need to imagine it anymore.

Normal People, Sally Rooney

SIX FEET UNDER (TV SERIES)

Season Three of Six Feet Under (“Perfect Circles”) opens with the ultimate episode of sideshadowing. The audience was left at the end of season two wondering if Nate would survive his surgery. He has been told by his doctor of various possibilities: death, disability, or perhaps he’d come out fine. Each of those is offered to the audience before we learn what actually happens to Nate. In this case, the episode explores the theory of infinite universes — that each of these things did happen to Nate; it’s just that in this world, he happened to survive.

Later in the episode, Nate overhears Ruth talking to Lisa and learns his conception was an accident.

Nate: “I don’t like knowing that my whole existence is an accident.”

The sideshadowing in this episode keeps the audience on tenterhooks, wondering what really did happen to Nate, but also serves to convey the idea that life is entirely random; we are all here by chance, and there are many other ways life could have gone.

JUST LIKE FATE (Young Adult)

I have not read this one myself, but here’s what Kirkus had to say:

In an ambitious narrative device, the book juggles two alternating plots, following a prefatory “Before” section. Chapters titled “Stay” are based on the premise that Caroline chooses to remain with her grandmother in the hospital and hears her dying words of love for her granddaughter; in those titled “Go,” Caroline succumbs to her friends’ pressure to go to a party, thus missing the moment when Gram dies.

Kirkus Reviews

ME MYSELF I BY PIP KARMEL (Australian ‘chick-lit’)

This is a book from 2000 which has been adapted into a film starring Rachel Griffiths. This is much more light-hearted than Shriver’s, and makes use of a structure oft-utilised by writers of picturebooks. When the protagonist comes back from the fantasy world (or in this case, wakes from a vivid dream), they are lead to believe it wasn’t really a dream because they have brought something back with them from the ‘dream world’. Or things have been moved slightly, and their world view is significantly changed (in almost all cases, for the better).

LIFE AFTER LIFE BY KATE ATKINSON (Contemporary Fiction)

Atkinson’s (Started Early, Took My Dog, 2011, etc.) latest opens with that conceit, a hoary what-if of college dorm discussions and, for that matter, of other published yarns (including one, mutatis mutandis, by no less an eminence than George Steiner). But Atkinson isn’t being lazy, not in the least: Her protagonist’s encounter with der Führer is just one of several possible futures. Call it a more learned version of Groundhog Day, but that character can die at birth, or she can flourish and blossom; she can be wealthy, or she can be a fugitive; she can be the victim of rape, or she can choose her sexual destiny. All these possibilities arise, and all take the story in different directions, as if to say: We scarcely know ourselves, so what do we know of the lives of those who came before us, including our own parents and—in this instance—our unconventional grandmother? And all these possibilities sometimes entwine, near to the point of confusion.

from Kirkus

THE PARALLEL LIFE AS A SCENE

In this post I talk about the writing technique of ‘side-shadowing’. This is basically a parallel life, but it may only be a sentence, a throw-away comment or a paragraph. Quite often we get a side-shadow scene at the end of a story, to suggest to the reader there may be other endings, or may have been, had things not turned out differently.

Anton Chekov was a fan of sideshadowing in his short stories. In Russia, Dostoyevsky was no stranger to sideshadowing, either. Tolstoy does it too.

Philippa Pearce uses the technique of sideshadowing in Tom’s Midnight Garden.

Canadian short story writer Alice Munro is also a fan. Check out one of her earlier stories, “Queenie“. A woman wonders what happened to her estranged step-sister after she got into a coercively controlling relationship as a young woman. Munro showcases various ways of sideshadowing across her oeuvre.

In “Passion“, a paragraph begins: ‘But this was the thing that had not happened’. This lets readers know that the previous paragraph was a side-shadow for what might have been. Now we hear how sex with her future husband really was. (Not romantic as she had hoped, for she has fallen in love with his family rather than with him.) In the same story, Munro achieves sideshadowing in another way: An elderly point-of-view character is looking back and isn’t sure which is a real memory and which is imagined:

As a matter of fact, she does not know, to this day, if those words were spoken or if he only caught her…

Alice Munro, “Passion“

See also Cheever’s short story “Just One More Time“. The final scene is an example of sideshadowing, because the reader doesn’t know if it really happened within the veridical world of the story.

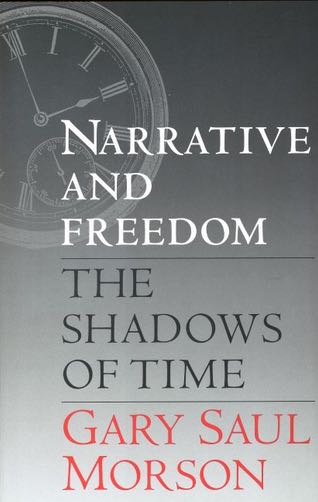

In this important and controversial book, one of our leading literary theorists presents a major philosophical statement about the meaning of literature and the shape of literary texts. Drawing on works by the Russian writers Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, and Chekhov, by other writers as diverse as Sophocles, Cervantes, and George Eliot, by thinkers as varied as William James, Mikhail Bakhtin, and Stephen Jay Gould, and from philosophy, the Bible, television, and much more, Gary Saul Morson examines the relation of time to narrative form and to an ethical dimension of the literary experience.

Morson asserts that the way we think about the world and narrate events is often in contradiction to the truly eventful and open nature of daily life. Literature, history, and the sciences frequently present experience as if contingency, chance, and the possibility of diverse futures were all illusory. As a result, people draw conclusions or accept ideologies without sufficiently examining their consequences or alternatives. However, says Morson, there is another way to read and construct texts. He explains that most narratives are developed through foreshadowing and “backshadowing” (foreshadowing ascribed after the fact), which tend to reduce the multiplicity of possibilities in each moment. But other literary works try to convey temporal openness through a device he calls “sideshadowing.” Sideshadowing suggests that to understand an event is to grasp what else might have happened. Time is not a line but a shifting set of fields of possibility. Morson argues that this view of time and narrative encourages intellectual pluralism, helps to liberate us from the false certainties of dogmatism, creates a healthy skepticism of present orthodoxies, and makes us aware that there are moral choices available to us.

THE COULD-HAVE-BEEN CHARACTER

There is another, less obvious, way authors can create a type of sideshadowing for the reader: by creation of a ‘could-have-been’ character:

Could-Have-Been. This is Cho in Harry Potter. These Could-Have-Beens have the significant value in that they present other options, and can keep the plot from feeling inevitable; as such, they can shore up suspense. These characters are useful in another way, for often they show that a MC isn’t going to get everything he wants. (That’s a danger for books … when a protagonist can have her cake and eat it too.) A subcategory of the Could-Have-Been is the Fateful Warning—what the MC might be or become if circumstances were different. In Les Miserables, Fantine is who Cosette might have become, if Jean ValJean hadn’t intervened.

CRAFTING SECONDARY CHARACTERS: BEYOND FOILS, FRIENDS, & FOES

SIDE-SHADOWING IN ILLUSTRATION

In these illustrations, characters imagine another reality.

SHADOW STAGING

This is another word which describes a literary device and also includes the word ‘shadow’.

Shadow staging: Presenting a crucial event (such as an out-of-whack event) by its consequences rather than showing it directly. In Sophie’s Choice, for example, Sophie’s choice is shadow-staged throughout the whole novel. (CSFW: Steve Popkes)

Glossary of Terms Useful In Critiquing Science Fiction

Header illustration: William Rothenstein, The Doll’s House (1899–1900)