Two Weeks With The Queen is an Australian middle grade novel by Morris Gleitzman. My edition is copyrighted 1989, though other places on the web will tell you this book was first published in 1990 or 1991.

I was in Year Seven in 1989. Fast forward to 2021 and my own Year Seven kid is studying this book in their first year of high school. Fair to say, this is a story with longevity.

My kid proudly announced to their English teacher, “This is the first book I’ve read on my own without pictures!” Um, this is true, despite the many, many books in our house, and nothing to be proud of when you’re almost 13, still doggedly attached to graphic novels and comic books, repelled by walls of text. I was wondering which book-without-pictures would crack the seal for my stubborn reader. Well, this is the one that did it. Kudos to Morris Gleitzman.

That said, my kid struggled with the first half, then read the second half in one go.

“You know, the Queen doesn’t just refer to the Queen of England,” I said, when they announced it was boring.

“What do you mean?”

“I mean, the Queen also means Drag Queen.” I was seriously in danger of ruining the entire book by spoiling the big reveal, but sometimes a spoiler is also a motivator.

“Oh! Cool!” As a fan of the Drag Race TV shows, Rainbow storytime and all things Rainbow, this was enough to get the resident reluctant reader over the finish line. The spoiler worked.

An hour or two later, “I’ve finished! But this story is so sad.”

Here’s your content note: The kid fell asleep crying into their pillow. But at least I know they’d both read it and understood. And also? Sometimes it’s good to have a cry. Some stories deserve a good cry. Because some things in life are sad. Sad as heck.

As for me, I’d just binge-watched It’s a Sin. So the kid and I experienced a concurrent AIDs epidemic narrative hangover. (By the way, Australian-made Holding The Man will turn you into the same variety of emotional wreck.)

The kid has now asked me assist with their English assignment, which is rare. This is why I’m re-reading Two Weeks With The Queen myself.

I’ll admit it: I was a bit hesitant, returning to this 1989 middle grade AIDs novel 30 years later. I can see class sets are still hanging around high school English departments, still being read, but how does the story hold up? The dominant culture has shifted so much on GRSM attitudes (ie. gender, romantic and sexual minorities) it’s ridiculously optimistic to return to fiction written at the start of the late 80s and expect the story not to have dated in some terrible way.

PRE-READING QUESTIONS

- This story was written and set in the late 1980s. Overall, do you think it was better to be a kid in Australia in the 1980s? Why? Why not?

- Do you think Australia is a lucky place to live? Why? Are there countries luckier than ours? Why do you think Australians commonly refer to ourselves as ‘The Lucky Country’?

- Do you think it’d be fun to be a member of a royal family?

- What do you know about the AIDs epidemic?

USEFUL WORDS

A chart set out like this can be helpful:

| WORD | WHAT I THINK IT MEANS | WHAT IT MEANS |

| foreshadowing | a storytelling technique in which the author hints at something to come without being too obvious about it | |

| juxtaposition | two things put together for contrast | |

| third-person narration | Any story told in the third person (without using “I” or “we”) e.g. “They did this”, “Colin did that” | |

| intersplice | To join or connect by putting something extra between | |

| metaphor | A comparison which doesn’t make use of ‘like’ or ‘as’. | |

| epistolary | In the form of letters/mail | |

| proxy | Something that stands in for something else. e.g. the queen as a proxy for everything fancy, rich and powerful. | |

| symbol | Something that stands in for something else, but when the ‘something else’ is abstract. e.g. summer as a symbol of happiness. | |

| archetype | A very typical example of a certain person or thing. |

POST-READING QUESTIONS

- How does the author let readers know this story is set in Australia?

- How is Colin, a child of the 80s, different from a typical kid of today? (And how do we know the setting is the 1980s?)

- How is Luke’s trip to the Sydney hospital foreshadowed?

- There’s a major juxtaposition running through this book: The contrast between health and sickness, life and death. What are some smaller examples of juxtaposition? (In the landscape, in the characterisation?)

- What is Colin wrong about at the start of the story?

- How does third person narration interspliced with letters composed inside Colin’s head help Morris Gleitzman to tell the story?

SETTING OF TWO WEEKS WITH THE QUEEN

PERIOD

Late 1980s, when many Australian families were still turning on the TV to watch the Queen’s Christmas Broadcast. We also used to do this in New Zealand, but sometime in the 1990s we stopped. Even though the Queen hadn’t stopped delivering her Christmas broadcasts, those of us in the Antipodes stopped watching her in large numbers.

Here’s the broadcast from 1989. I feel a little sorry for the Queen. I’d absolutely hate to have every single one of my Christmas days wrecked by having to give a speech to the entire Commonwealth. LIVE. And she never once stuffed up or tripped on the stairs. Fancy that.

This isn’t how I thought of it as a kid, though. The Queen was the Queen. Not quite human. Now I look back on her, licking her lips occasionally, and realise she was nervous. She had a dry mouth. The main character of Two Weeks With The Queen is envious of the Queen — she can have anything she wants for Christmas.

Except she can’t enjoy the day to herself.

The Queen is bound by many and various rules. She can’t voice political opinions. She can’t choose who she speaks to at dinner parties. She can’t choose what she names her children. She can’t hug her family in public, cross her legs, be addressed by a shortened name, or pop down to the local for a bag of crisps. She can’t eat a wide variety of foods (including shellfish and garlic). She’s not allowed to drink foreign tap water. She can’t grow long fingernails or paint them; she must always have neat, healthy looking hair and her make up must be modest and natural. Although the Queen loves to drive, she rarely gets to drive herself anywhere. Everywhere she goes she is accompanied by a security team.

DURATION

The duration of this novel is embedded into the title, though the story actually begins a bit before the ‘two weeks’ with the ‘Queen’.

LOCATION

When Australian authors set their books in Australia there’s a rule they must follow: Australia has to be mentioned (or strongly hinted at) within the first few pages. This isn’t something American authors have to do. Americans just sort of expect books to be set in America unless told otherwise… which is why Australian authors do otherwise.

How does Morris Gleitzman tell the reader we are in Australia? He hints at it very strongly first: It’s Christmas time and it is also hot. (The parents are fanning themselves with a bit of cardboard ripped off the beer. And then, after we’re meant to have understood from ‘dusty paddocks’ (an archetypal Australian landscape and a typical Australian phrase) Luke tells the reader via an imaginary letter to the Queen that chopping people’s heads off is ‘frowned on in Australia’.

In the next chapter we learn a more specific setting: Smalltown Western New South Wales (where the ambulance worker doubles as the woman who works at the bakery).

ARENA

The story takes place in Australia and then in England, on the other side of the world. ‘Other side of the world’ equals ‘two different worlds’, and it’s convenient for storytelling purposes that England and Australia are on opposite sides of the globe because this creates a Janus effect for the reader, reinforcing juxtaposition.

MANMADE SPACES

In stories, writers commonly sit on a roof when they make the decision to set out on a journey.

Colin sat on the roof of the shed and stared out over the paddocks. The sun-scorched corrugated iron stung his legs and he didn’t care.

Two Weeks With The Queen

(Characters also commonly sit on roofs near the end of stories, when they have a self-revelation.)

NATURAL SETTINGS

1980s Western New South Wales is low on population, rich in space. The landscape over Christmas is brown and flat. If you get onto Google Earth and plonk yourself down at a random spot you get somewhere like this.

WEATHER

Summer is often a symbolically happy time, but in Australian narrative, summers can function more like symbolic winters. Summers are harsh and dangerous here. Although Luke is on his summer holiday and he’s expecting to enjoy his Christmas and New Year, awful things are happening with his family.

TECHNOLOGY

There are details in this book which place the story firmly in the 1980s, for instance the description of the doctor’s car:

The leather seats, the real wood dashboard, the aerial that went up without you having to stop the car and get out and pull at it and swear like with Dad’s.

Two Weeks With The Queen

The coveted toy Luke gets for Christmas is called an MiG (Mikoyan-Gurevich), which is a Soviet plastic toy fighter aircraft.

This toy plane foreshadows Luke’s ride in a real plane after his test results come back. The MiG was also the world’s first mass-produced supersonic aircraft. Throughout the story, Colin constantly reasons that if humanity can create X excellent technology (e.g. the MiG) humanity can also cure Luke’s cancer, if only they found the motivation.

Colin’s mum ‘answers the phone in her long distance voice’ — a voice I haven’t heard in a long while, though Outback kids might know it still.

Young contemporary readers won’t be familiar with the tradition of kids onboard a flight being invited to visit the pilots in the cockpit. The events of September 11, 2001 changed all that.

LEVEL OF CONFLICT

Generally speaking, the late 1980s is a Golden Era for Australians.

It was the era of Hawke and Keating, Kylie and INXS, the America’s Cup and the Bicentenary.

It was perhaps the most controversial decade in Australian history, with high-flying entrepreneurs booming and busting, torrid debates over land rights and immigration, the advent of AIDS, a harsh recession and the rise of the New Right.

It was a time when Australians fought for social change – on union picket lines, at rallies for women’s rights and against nuclear weapons, and as part of a new environmental movement.

And then there were the events that left many scratching their heads: Joh for Canberra . . . the Australia Card . . . Cliff Young.

In The Eighties, Frank Bongiorno brings all this and more to life. He uncovers forgotten stories – of factory workers proud of their skills who found themselves surplus to requirements; of Vietnamese families battling to make new lives for themselves in the suburbs. He sheds new light on ‘both the ordinary and extraordinary things that happened to Australia and Australians during this liveliest of decades’.

Bob Hawke was Australia’s optimistic Prime Minister. Climate change was happening but the general public wasn’t even thinking about it. We kids of the eighties enjoyed a lot of freedom. The lucky among us felt the future was bright.

This song by Kylie and Jason (Donovan) made the top charts in 1989. The pair were popular on Neighbours. Even in New Zealand we were collecting Neighbours cards that came in packs of bubble gum. No one wanted the hard, pink rectangles of bubble gum (which looked suspiciously like erasers) but everyone wanted the Kylie and Jason collectors’ cards.

In the music video, Kylie is writing a love letter. It’s an interesting parallel that in Two Weeks With The Queen Colin is also composing an imaginary letter — not to a love interest but to his proxy for all people powerful and rich: The Queen.

Two Weeks With The Queen opens with a juxtaposition between rich and poor. The Queen is economically very wealthy (though her wealth is not her own to spend as she likes) and when I was growing up, the Queen was the proxy character for a fancy person you want to impress. In our house, the Queen got most mention at the dinner table, when my brothers and I broke the rules of etiquette.

“What are you picking up that chop in both hands for? That’s bad manners. What if the Queen popped in, and saw you holding a greasy mutton chop with both hands? Eh? You know you’re only meant to pick up a greasy chop with one hand.”

“Stop eating with your mouth open. The Queen’d be horrified.”

The story is full of juxtaposition:

The hot Australian summer where the Queen is but a remote figure versus the relations in England where Christmas is cold.

In the 1980s, we believed that things in England were better than they are down here. I suspect this is an aspect of the story which Gen Z won’t relate to. I don’t believe young Australians are now looking to England and thinking, Wow, if only we had what they had things would be better. Yet Colin looks to England and thinks the answer to his brother’s cancer cure will come from the land of the almighty and all powerful: Home. As someone the same age as fictional Colin, I remember this attitude. I don’t believe things really were better in England, but I certainly remember the sense of inferiority about living in the Antipodes. Even if we didn’t actually want to live in England, because the houses on Coronation Street and Eastenders were poky and dark, we did have a sense that the best things in the world came from there.

THE EMOTIONAL LANDSCAPE

The land which lives inside the main character. The imaginative landscape, the difference between what is real in the veridical world of the story and how a character perceives it — never exactly as it is, but rather influenced by their own preconceptions, biases, desires and personal histories. In what way are characters wrong about the veridical world of the story, and how will this be their downfall (or advantage)?

Colin is wrong to think that the answer to his family’s problems resides in England, but this is what our generation thought.

What else is Colin wrong about at the start of the story?

He thinks he’s older than he is, comically referring to his eight-year-old brother as a kid in relation to himself, who is a grown, responsible adult. (Colin feels the weight of responsibility, even though the responsibility for Luke is not his.) This is the misbelief which propels him into action. He believes he has the power to fix cancer, even when doctors in Sydney cannot, being far too busy thinking about the broken aerials on their fancy big cars.

STORY STRUCTURE OF TWO WEEKS WITH THE QUEEN

PARATEXT

I need to speak to you urgently about my brother Luke. He’s got cancer and the doctors in Australia are being really slack. If I could borrow your top doctor for a few days I know he/she would fix things in no time. Of course Mum and Dad would pay his/her fares even if it meant selling the car or getting a loan. Please contact me at the above address urgently.

Yours sincerely,

Colin Mudford.P.S.

This is not a hoax.

Ring the above number and Aunty Iris will tell you.

Hang up if a man answers.

The marketing copy of Two Weeks With The Queen utilises epistolary narration (written as if it’s a letter).

The letter writing aspect of this novel is a convention which was mostly left behind in the 1980s and 90s. Contemporary young readers rarely write formal letters to friends and family. Letters have been replaced by social media and video conferencing technologies. It’s therefore unlikely that a middle grade character would be composing formal letters inside his head, though there are eccentric exceptions e.g. Manny Delgado of Modern Family comedic archetypes, who seem to come from an earlier era.

SHORTCOMING

The name Colin Mudford suggests a working class family, one example of a juxtaposition against the wealthy and all-powerful Queen. The dialogue of Colin’s family is reminiscent of the dialogue of Muriel’s Wedding (1994) — there’s a performative aspect to it — the way Australians think they talk, and which Australians know to be hilarious to non-Australians. When Australians go to England and hang out together in Earls Court, everyone seems to amp up the ocker. (New Zealand has its own version, exemplified by the comedic character of Fred Dagg.) This seems to happen to our young fictional character Colin, though it starts before he leaves Australia:

“I reckon it’s gastric. If it’ll help you put your finger on it I can tell you what he’s eaten today. One bowl of Coco-Pops, three jelly snakes, some licorice allsorts, packet of Minties, six gherkines, half a bowl of Twisties and a chocolate Santa. That was before lunch.”

Two Weeks With The Queen, Colin talking to Luke’s doctor

Colin Mudford has a younger, 8-year-old brother Luke who has high medical needs. For that reason, Colin feels he doesn’t get his share of attention and has already concluded that his parents like Luke better than they like him.

Like many of us, Colin is an admixture of anxious and flippant. When he learns his younger brother needs to be flown to Sydney the blood drains out of him. The gag in the next sentence: He’s never been on an aeroplane and now his younger brother will be beating him to it. Then he talks to the pilot, ostensibly trying to persuade him to let him go, but also (I deduce) because he is worried about a bumpy flight for his brother and father’s sakes.

‘See ya, Luke,’ said Colin and suddenly it was swirlier inside his chest than it was out on the airstrip.

Two Weeks With The Queen

In this way, Gleitzman does a masterful job of creating a child character who is anxious and who can’t articulate it. Colin’s interoceptive skills and self-knowledge aren’t as developed as those of a typical adult. Gleitzman gives the reader enough to work with: We can see that Colin’s outer concerns don’t match his underlying worry. This is a subtle way of teaching young readers emotional intelligence.

Morris Gleitzman conveys Colin’s anxieties to the reader partly by having him compose letters to people inside his head. The benefit of this technique: Gleitzman gets the main benefit of first person narration and also the benefits of third person narration.

The main benefit of first person narration: The reader gets an insight into the main character’s way of phrasing things and what’s on their mind.

Benefits of third person narration: The narrative ‘camera’ can leave Colin’s head a little and allow the reader to more easily see the wider picture, and therefore the things that Colin is slightly (or a lot) wrong about.

DESIRE

Colin wants a microscope for Christmas and doesn’t get one. At the start of the story he has received a functional and boring present: shoes.

But this is what I call a Macguffin Desire — I haven’t heard anyone else talk in these terms but by Macguffin Desire I mean a desire which kicks the story off but which is not sustained and which is soon replaced by a much larger desire: The desire to cure his brother of cancer.

Eggs are breakable. Hope is not.

When Natalie’s science teacher suggests that she enter an egg drop competition, Natalie thinks that this might be the perfect solution to all of her problems. There’s prize money, and if she and her friends wins, then she can fly her botanist mother to see the miraculous Cobalt Blue Orchids–flowers that survive against impossible odds.

Natalie’s mother has been suffering from depression, and Natalie is sure that the flowers’ magic will inspire her mom to love life again. Which means it’s time for Natalie’s friends to step up and show her that talking about a problem is like taking a plant out of a dark cupboard and giving it light. With their help, Natalie begins an uplifting journey to discover the science of hope, love, and miracles.

OPPONENT/ ALLY

An opponent in a story doesn’t mean ‘the villain’ or the ‘baddie’. It simply means the character who stands in the way of the main character getting what they want. Since Colin wants to stay home for the summer and practise cricket, his dying brother is his opponent for the purposes of this story.

Luke is also an opponent because Colin wants Luke to live.

Along his journey, Colin will meet people who help him and people who stand in his way. The uncle and auntie in London, with their only son who is constantly eating, are reminiscent of the Dursleys of Harry Potter, though less abusive. The father is of the same grumbling archetype, the mother is concerned with appearances (refusing to allow the word ‘cancer’ to be uttered in the house) and Alistair, the son, is nicer than Dudley but the implication is that boys who are only children are somewhat ‘coddled’ (a word I don’t like). In contrast to the go-and-get-em Colin from Australia, Alistair is a reactive character. So long as he has food, he is happy.

I’m reminded of Matt Bird’s head/heart/gut philosophy of storytelling. Stories commonly feature a trio of characters each of them ruled by a different part of the body. The head character makes the plans, the heart character feels, and the gut character is usually easy to pick because they are obsessed by food (or in stories for adults, by sex).

Clearly, in this story, Alistair is the gut character. So what is Colin? This is interesting, because at the start of the story he is a head character. He figures if he just makes the right plans, he’ll be able to save his younger brother. But as the story progresses, Colin’s character arc turns him from a character ruled by his head to a character more ruled by his feelings. A big clue that Colin has started to be more in touch with his feelings? The model plane. In England he finds a model plane for Luke — the only one Luke has been unable to get in Australia. Previously, Colin was jealous that Luke got a model plane for Christmas whereas he only got the functional gift of shoes, but now his feelings have shifted. He is now able to think about what would make Luke happy.

Welsh Ted at the cancer hospital is the mentor archetype we might find in a fairytale. There is a dearth of adult men who cry in fiction; men cry in real life far more often than storytellers let them cry on the page. Later we’ll learn that Ted isn’t exactly your macho stereotype, which partly explains why he lets himself cry in public.

Sociologists use the term ‘masculinities’ (plural). Colin’s uncle, obsessed with ‘show offs’ and Welsh, gay Ted exemplify different masculinities.

Which is the masculinity Morris Gleitzman ultimately rewards? Macho man or in-touch-with-his-feelings man?

PLAN

Colin will do as his parents want and go to stay with his relatives in London, but while he is there he plans to contact the Queen of England and persuade her to lend his family in Australia her best doctors. The Queen’s doctors will cure his younger brother Luke of cancer.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

Three main things happen before Colin realises that there’s nothing he can do — his brother is going to die.

He persuades his cousin to try and break into Buckingham Palace.

Next, he tries to sneak into the best cancer hospital in England.

A doctor persuades Colin that his younger brother is indeed going to die.

ANAGNORISIS

The following passage reveals to readers that Colin has finally understood the reality of Luke’s situation:

He stood up, pushed the nurse aside and ran for the door, through the door, down the corridor, nurses and patients looming up and bouncing off him, down another corridor. Ted’s shouts behind him, past the uniformed attendant, out into the cold bright air, cars parked everywhere, bumping into bumper bars and icy paintwork, to a corner, down into a corner, brick walls all around him, where hot tears of anger poured down his face and he didn’t care.

Two Weeks With The Queen

Philosopher Heidegger wrote about a developmental stage he called Being-toward-death. We learn about death when we’re very young, but we’re typically in our teens and 20s before we really give death much thought, and understand that we, ourselves, are not immortal. Young adult literature is full of examples of characters who realise that they can’t escape death. Every now and then it comes down into middle grade literature, because a younger character experiences the death of someone close.

Colin isn’t going to experience a necessary character arc unless he comes face to face with reality. This has involved less making-plans (head) and more feeling (heart). Sometimes in a character ensemble, one character moves between body-parts, so to speak. Commonly for middle-grade fictional boys, with masculine models who avoid feelings, that shift is from head to heart, or from a more toxic form of masculinity to a more healthy one.

However, ‘understanding the reality of a situation’ is not the same thing as ‘learning something deep and true about yourself’. Good stories are about self-revelations and characters who experience personal growth.

So Colin’s struggle phase isn’t finished yet. He chucks a tantrum. He lets out all the air from the tyres of the doctors’ cars. Tantrums are always satisfying to watch. (See Z Is For Moose and Don’t Let The Pigeon Drive The Bus.) Tantrums are satisfying even when the character is morally wrong. (Tantrums are pretty much always ‘wrong’.)

It’s not until Griff dies and Colin witnesses Ted grieving that Colin finally has a script for how to deal with the impending death of his brother in Australia. Colin’s anagnorisis is a two-parter: Luke is definitely going to die; this is how you grieve.

Then Alistair has his own character growth, finally standing up to his overbearing mother by insisting Colin be allowed to go home and see Luke before Luke dies.

NEW SITUATION

The letter from the palace wishes Colin’s brother a ‘speedy recovery’ but by this stage Colin knows there will be no such thing and that the letter is nothing but platitudes. Symbolically, he leaves it in the ashtray before heading home to Australia. (Why is this a ‘symbol’? Ashes symbolise a flame which has died. Flame often symbolises a strong desire. Colin no longer has the desire to cure Luke of cancer; ergo, the ashes are symbolic of Colin’s acceptance of death.)

In the final sentence we learn that Colin wouldn’t trade places with anyone, ‘not even the Queen of England’. He has learned that the only life worth living is an authentic life, beside your family (whether chosen or natal).

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

Foreshadowed earlier, Colin has realised after watching Alistair that ‘being an only child is not all it’s cracked up to be’.

By following Colin in his character arc the reader has been given enough information to know that Luke is about to die. Like his cousin, Colin is about to become an only son.

RESONANCE

Morris Gleitzman has written many books, and Two Weeks With The Queen remains one of his earliest and also his most popular.

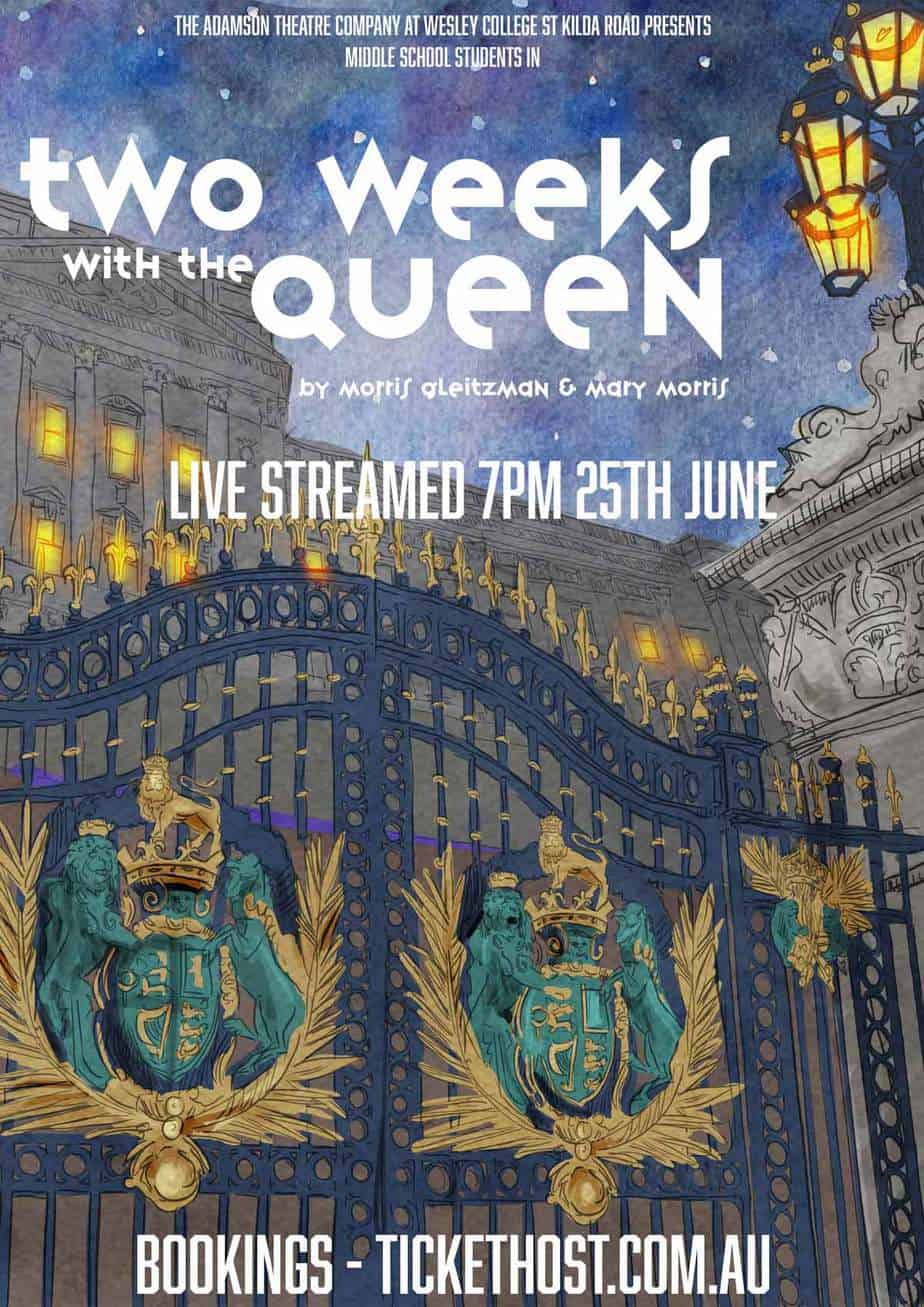

The book was adapted for stage by Mary Morris. The play has had many successful seasons in Australia and was then produced at the National Theatre in London in 1995 directed by Alan Ayckbourn. Audiences in South Africa, Canada, Japan and the USA have also seen Two Weeks With The Queen onstage.

If you’d like your adolescent reader to know the history behind It’s a Sin but understand they’re also too young for the explicit and confronting subject matter, Two Weeks With The Queen is a good middle grade choice, and holds up very well even in the year 2021.