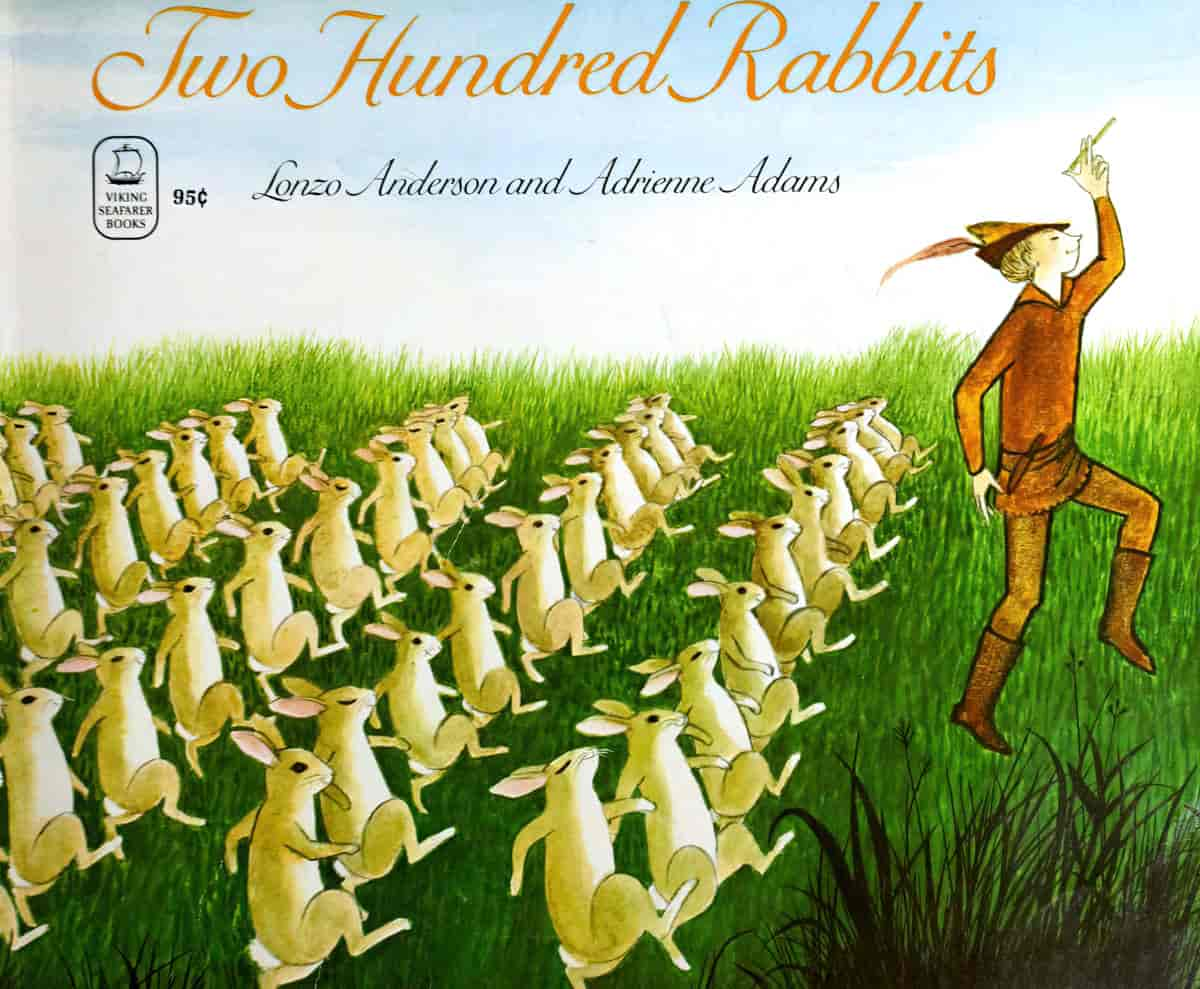

“Two Hundred Rabbits” is a 1968 picture book written by Lonzo Anderson and illustrated by Adrienne Adams, who were married.

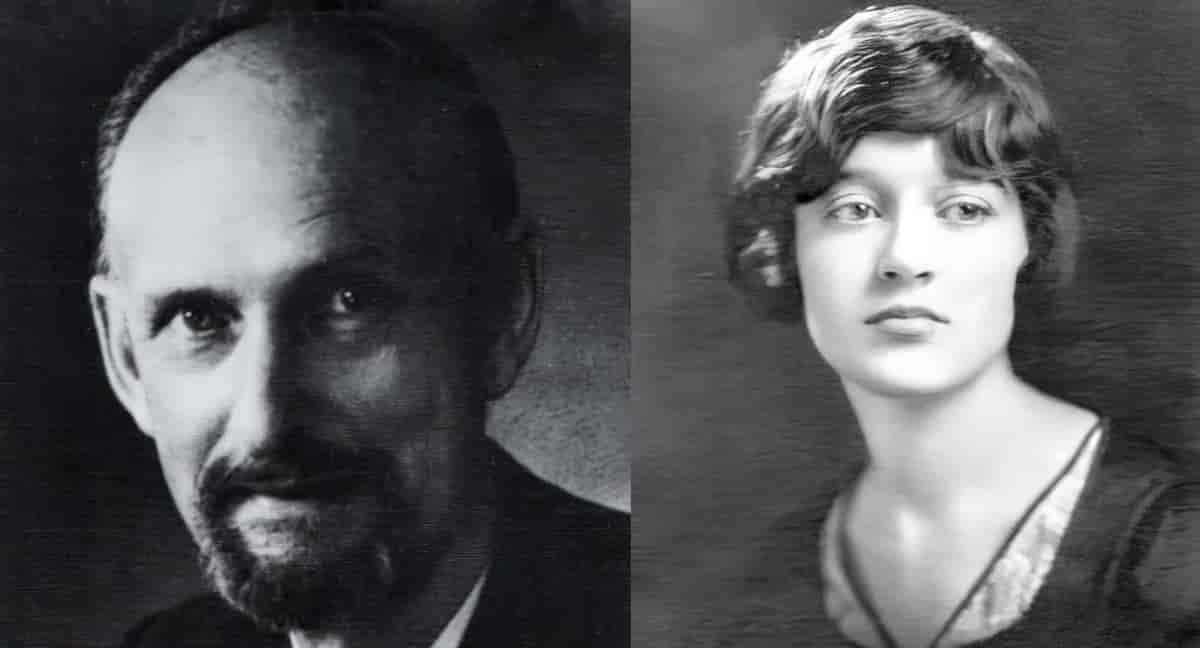

(John) Lonzo Anderson (1905-1993) was born outside Ellijay, Georgia, known for its mountain vistas and trail walks. He was a graduate of Harvard and over the course of his 88 years, learned 9 languages.

Adrienne Adams (1906-2002) was born in Arkansas and grew up in Oklahoma. Adams both wrote and illustrated picture books. She won Caldecott medals in 1960 and 1962. Adams worked in tempera, gouache, watercolour and crayon.

The couple’s first book together was Bag of Smoke: The Story of Man’s First Reach For Space, published 1942 after they’d been married for seven years. As you can probably guess from the WW2 timing, this picture book isn’t about rockets to the moon, but features a hot air balloon on the cover. This was Adrienne’s first picture book. As a trained illustrator, her main gig was textiles, greeting cards and other commercial art.

When a writer and illustrator are married, you can be pretty confident the pair communicated with each other during the creation process, which isn’t true when the publisher contracts the writer, then separately contracts the illustrator (the vast majority of cases). Where writer and illustrator collaborate extensively, there is frequently (but not always) an ineffable uniqueness to the story.

What Happens In Two Hundred Rabbits?

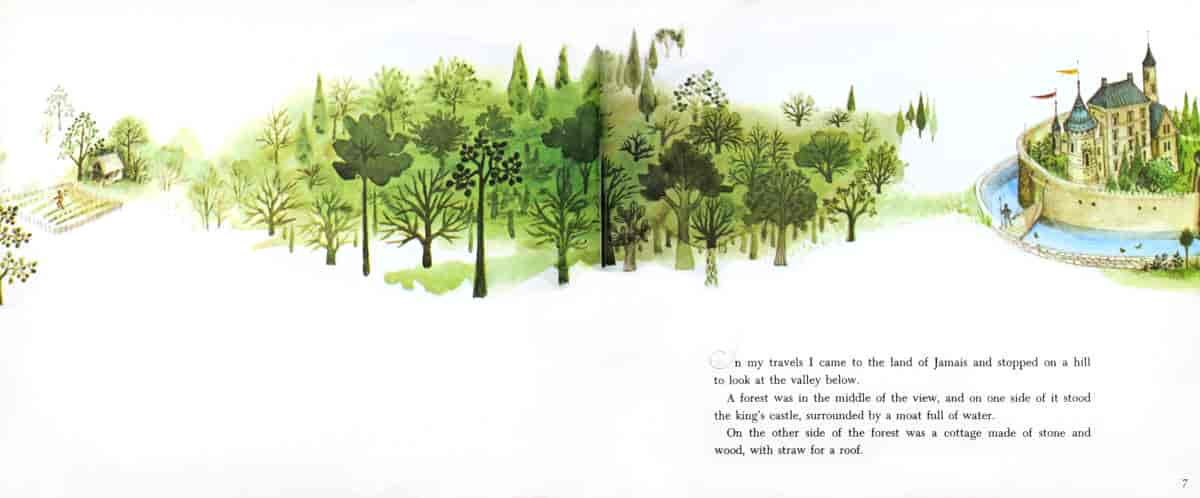

Two Hundred Rabbits is a contemporary literary fairytale with a twist… Someone is out on his travels, but we don’t know who it is. Generally in fairy tales, a young man (most often the youngest brother) is out in the world seeking his fortune. We don’t know where he is going or where he has come from — that’s of no consequence. We can expect him to meet friends and foes along the way and get tested. (Vladimir Propp outlined all of the things that could possibly happen to this fairytale young man.)

Except this isn’t a young man, is it. Someone (who?!) is watching the town from a detached distance.

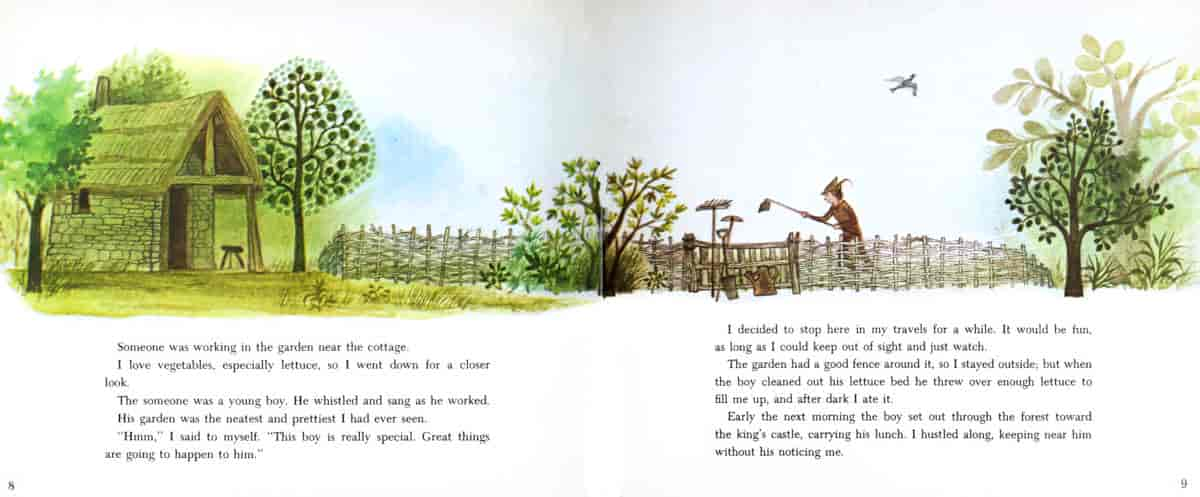

I’ll admit it. I was remarkably slow to pick up who was watching. I thought, “Clearly this someone likes lettuces. I know who likes lettuces. Snails and slugs. This viewpoint character must be a snail.”

I was surely influenced by the fact that I grew up in 1980s New Zealand, and every single Sunday morning listened to the same two Radio New Zealand children’s radio dramas. One was Badjelly the Witch by Spike Milligan. The other was a very odd and creepy English story about slugs eating lettuces.

I did start to wonder how a snail/slug could possibly keep up with the boy, given as how snails and slugs have no legs. But everything else fit nicely. I mean, snails and slugs would admire a boy who worked assiduously on his garden, right?

So, this young man with a feather in his cap sets out into the world to seek his fortune. He eschews labouring jobs and peasant work and instead has the self-confidence to apply for a job entertaining the king.

One problem: He has no skills in that regard. Undeterred, he goes to the woods to practice his singing. He’s a terrible singer. Also established fact: He’s no good at playing the fiddle, either.

Still, with the confidence of a privately educated cishet able-bodied white boy he’ll give it a go. The king will have to hire him.

An old woman appears. A witch, we can assume. According to Propp, this is the mentor. Scratch that. ‘Mentor’ is Joseph Campbell’s word. Vladimir Propp talked about ‘donors’, which unfortunately puts me in mind of organs and car accidents.

This old witch no doubt has a cottage in the woods and is sick of this kid hollering his lungs out nearby, so she suggests he make himself a little flute.

“Do you know how to make a slippery-elm slide whistle?” she asks.

“Why, yes,” says the boy. “Doesn’t everyone?”

I, for one, have never heard of a slippery-elm slide whistle. We used to make ‘flutes’ out of hair combs and folded tissue paper, but that was the extent of my home-made musical instrument-making.

The Internet tells me Slippery Elm is good for regulating bowel motions. My mind goes places with the word ‘slippery’.

The Internet also tells me how to make a slippery-elm slide whistle, introduced with, “Ah the good old days, when a kid could spend hours entertained by nothing more than a stick.”

All right, I’m back now. I’ve made my slippery-elm whistle, which sounds 100% better than those cursed school recorders kids still learn music on.

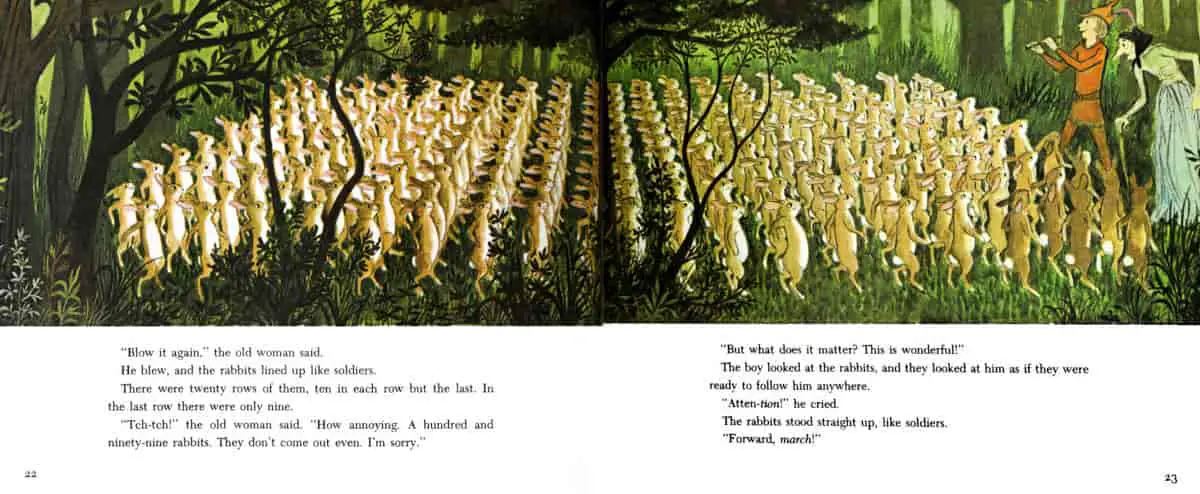

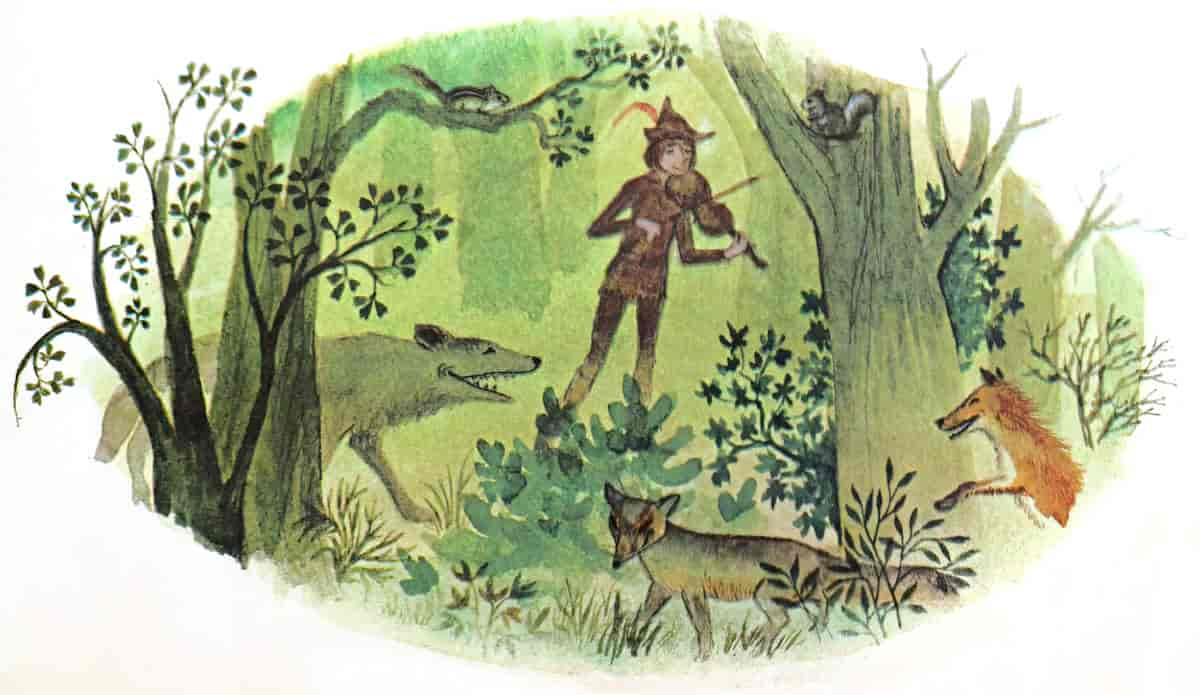

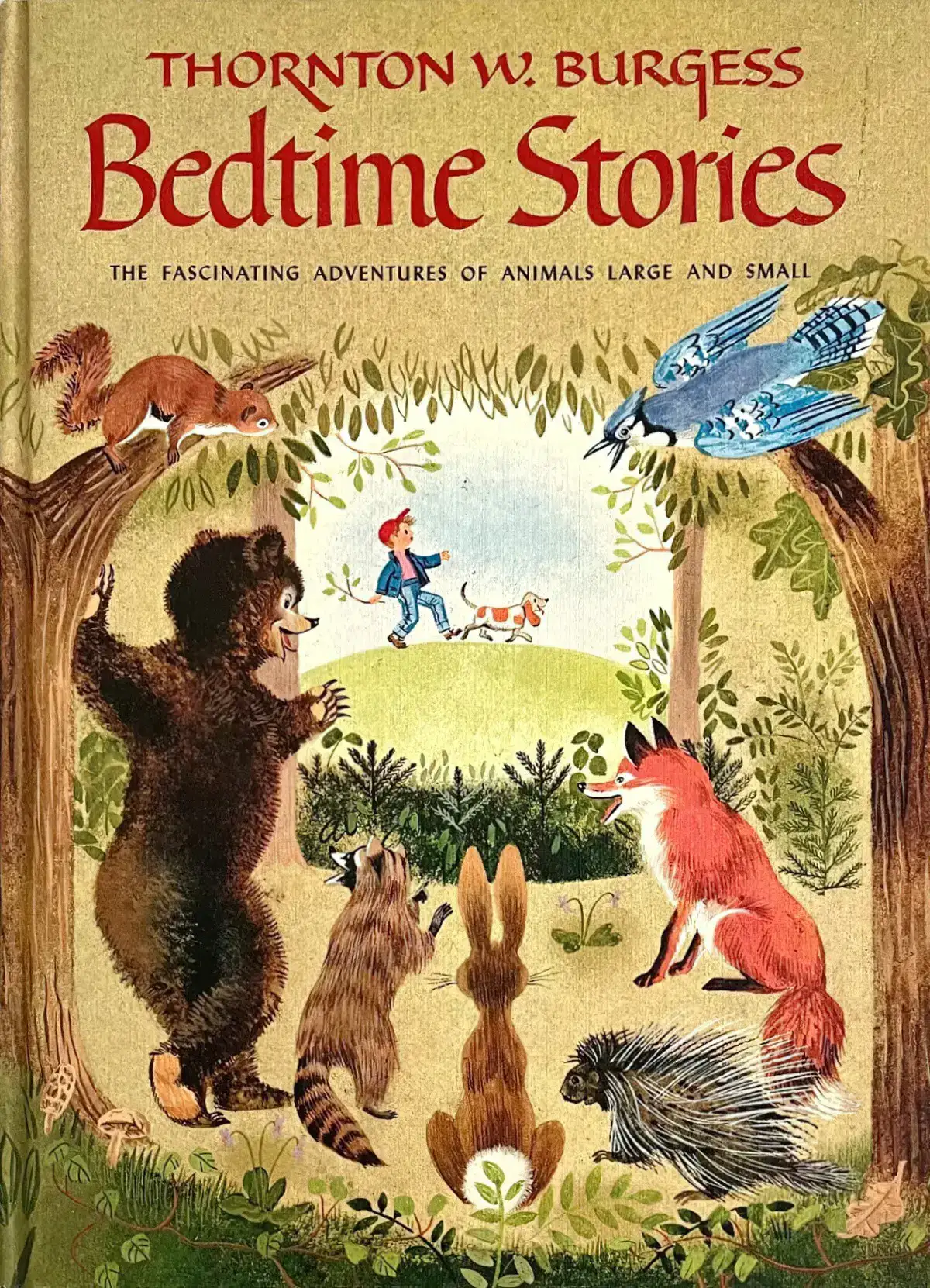

This fairytale boy has shared his sandwich with the skinny old witch which is basically a Save The Cat moment, establishing him as a kind, empathetic character who deserves a reward. But look at those rabbits, will you? He’s gonna Break Bad at some point. Alternative title: “The Pied-Piper As A Young Man.” Here he is practising on rabbits first.

Rabbits have caused untold environmental damage in my home countries of New Zealand and Australia, so our picture book rabbits look a little different (thanks to John Marsden and Shaun Tan) but here I’m probably not supposed to be thinking about that. Aren’t they cute. All lined up like an actual army about to invade… something. See also: Excess, Hyperbole and Pestilence In Illustration.

If you’re read enough fairy tales (or simply scanned the list of Propp’s narratemes) you’ll know that this kid does get a job with the king because the king is sufficiently amused by a kid who can enchant rabbits with a wood whistle. Except the king is an eccentric type who is bothered by the uneven number of rabbits in the final line, and orders nine of them ‘gone’.

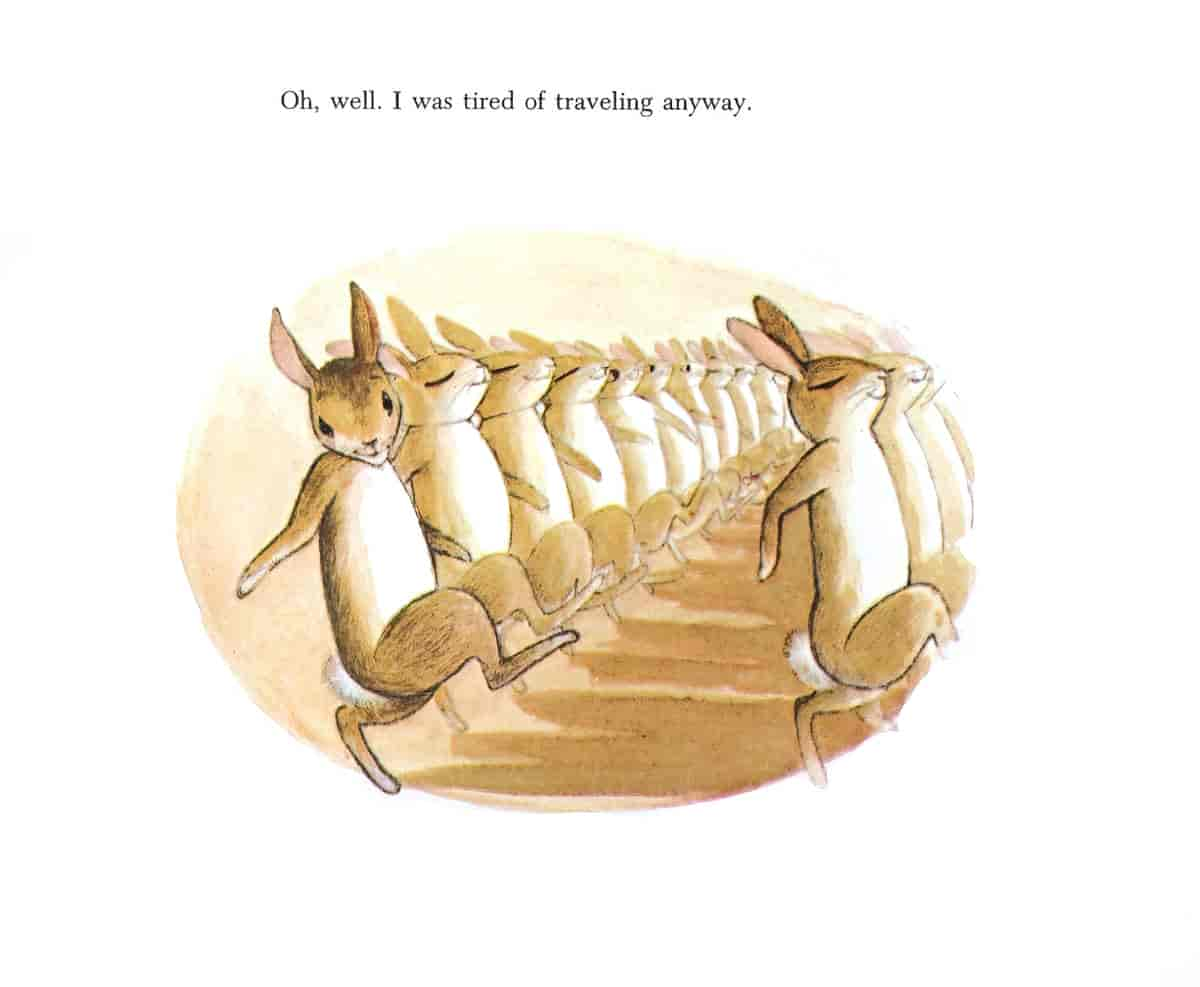

The kind boy doesn’t want to hurt those nine rabbits’ feelings. At this point, the viewpoint rabbit (OMG! The twist!) appears and saves those nine rabbits from… well, let’s not think about that, either.

I love how Lonzo has decided to quit the story. He doesn’t muck about. Also, due to binding constraints you get a set number of pages in a picture book. So there’s that.

PERSPECTIVE IN TWO HUNDRED RABBITS

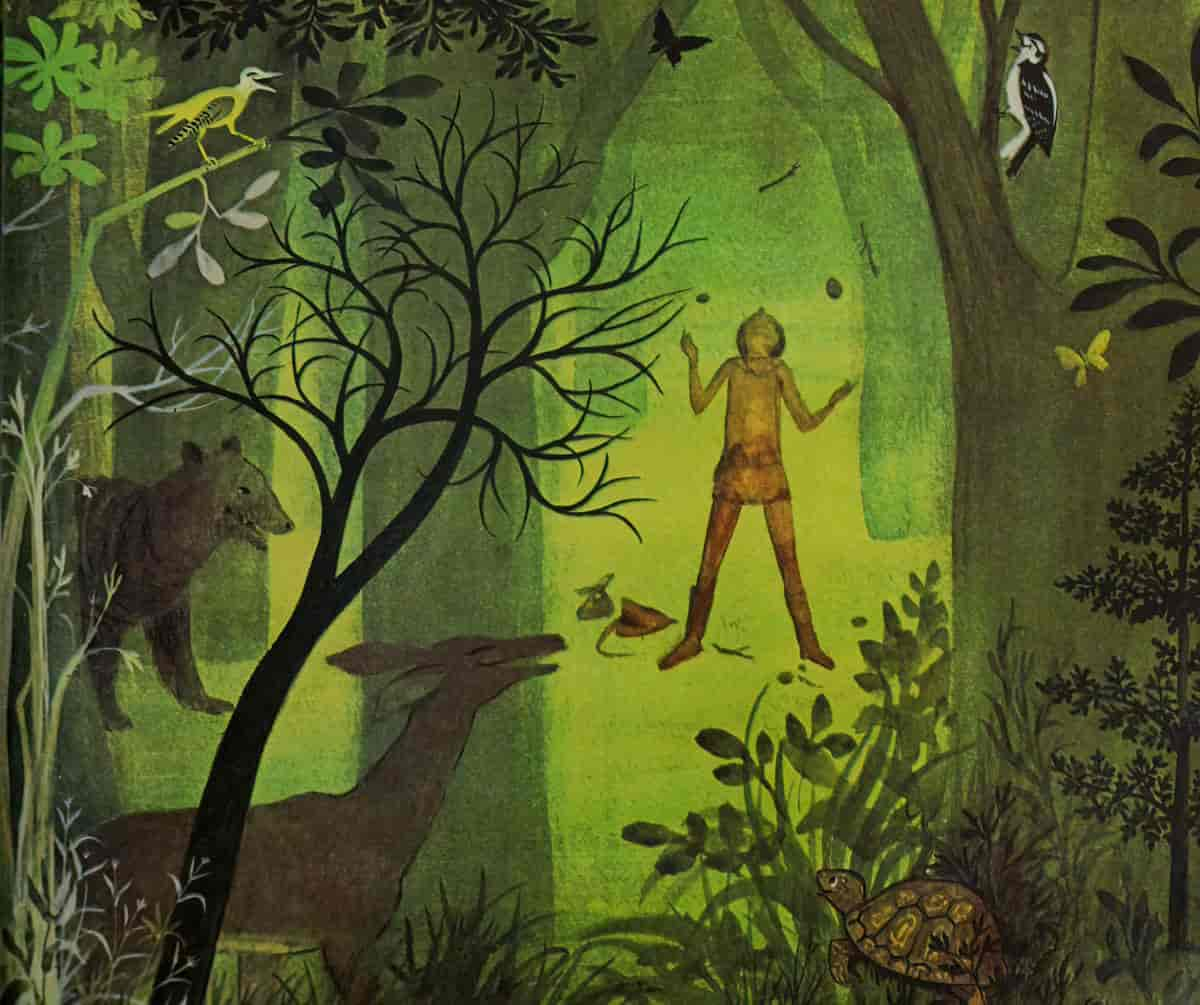

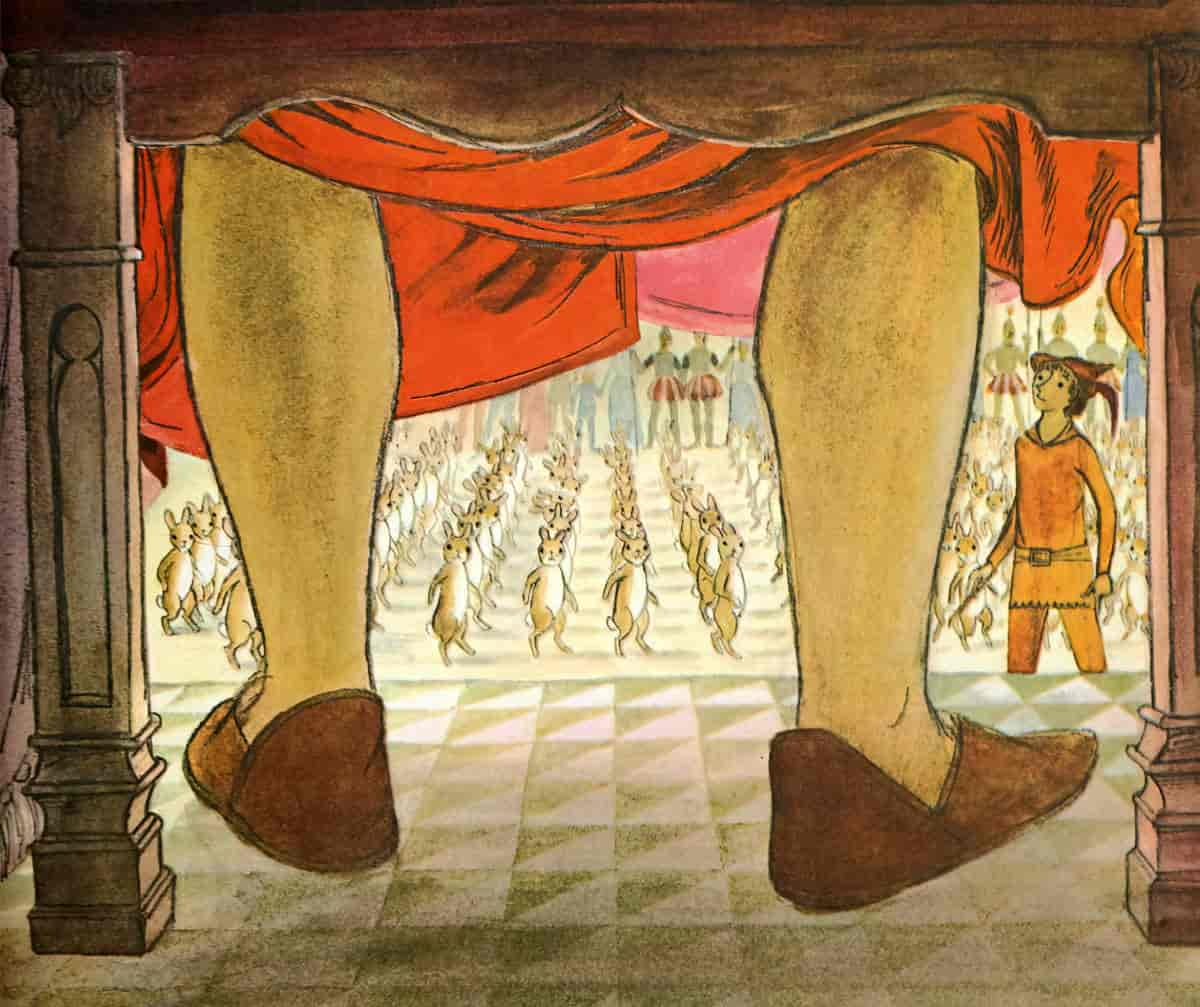

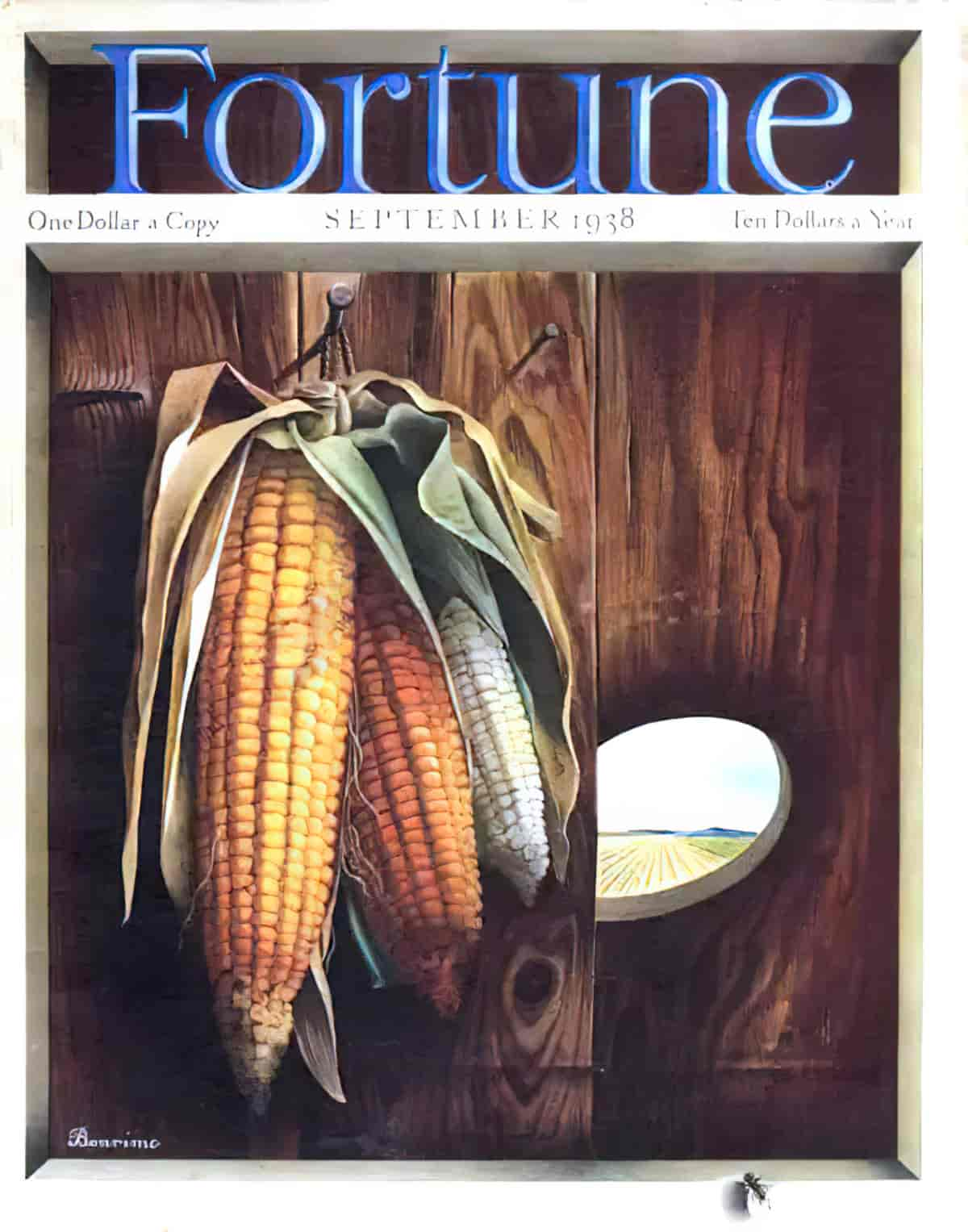

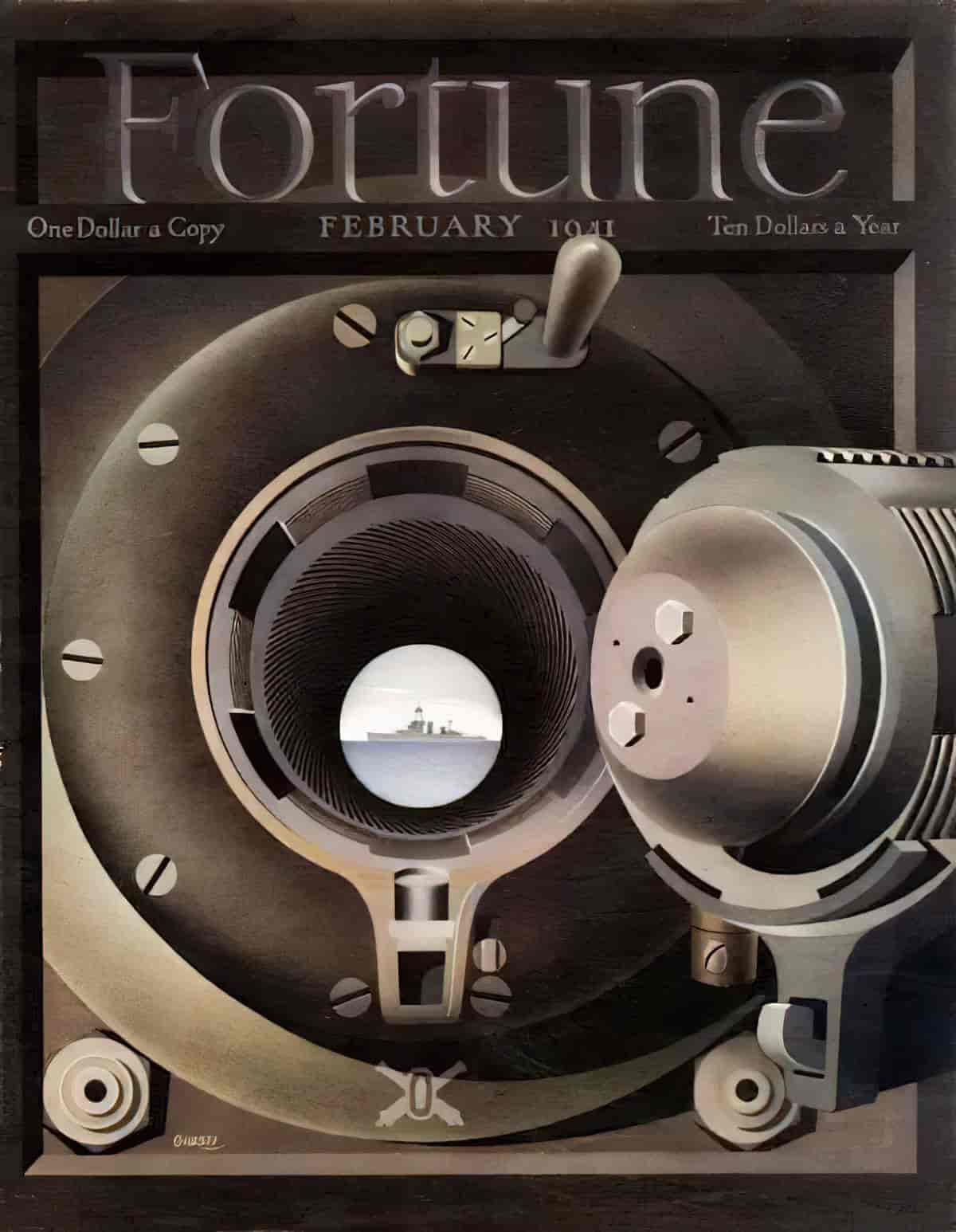

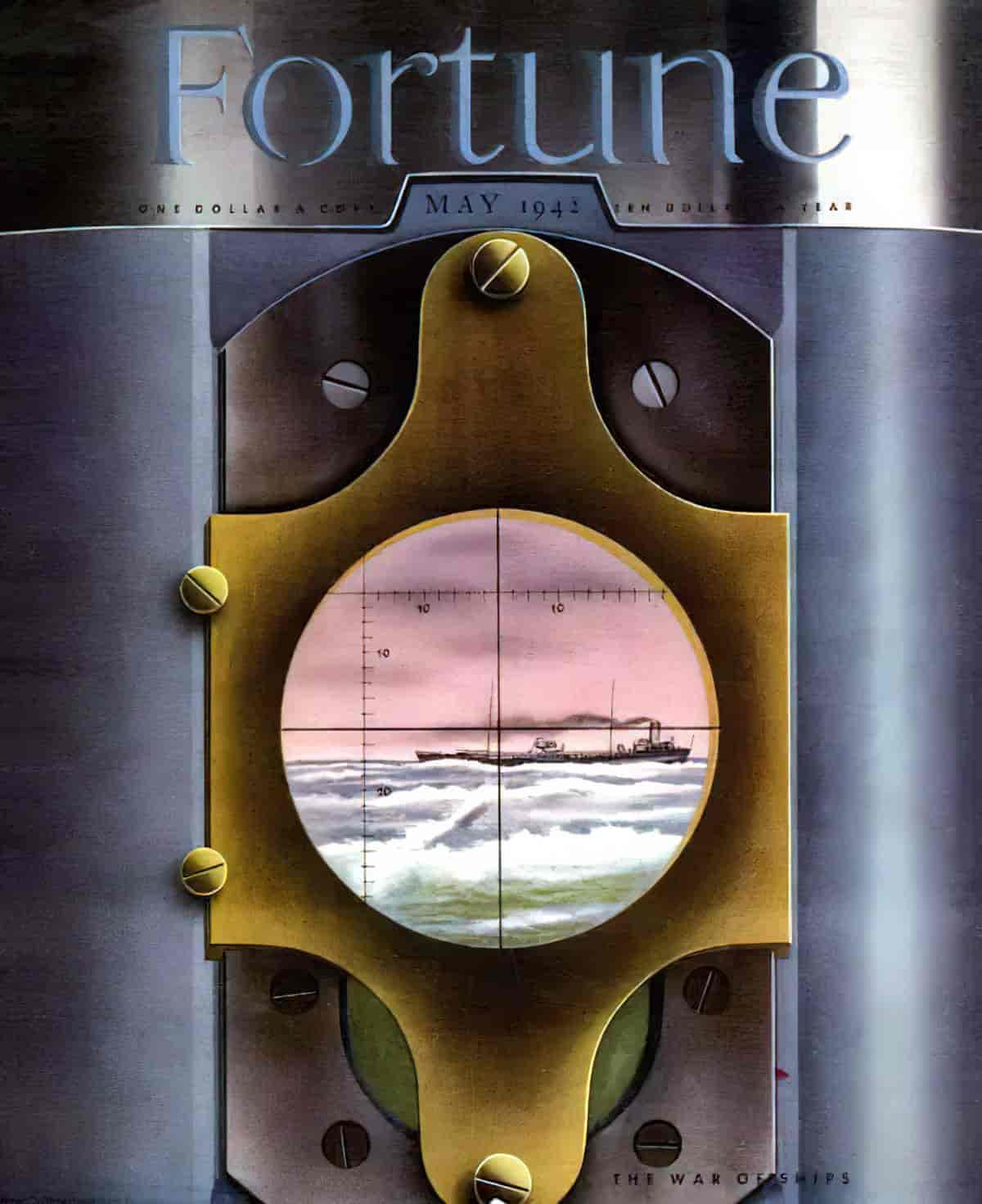

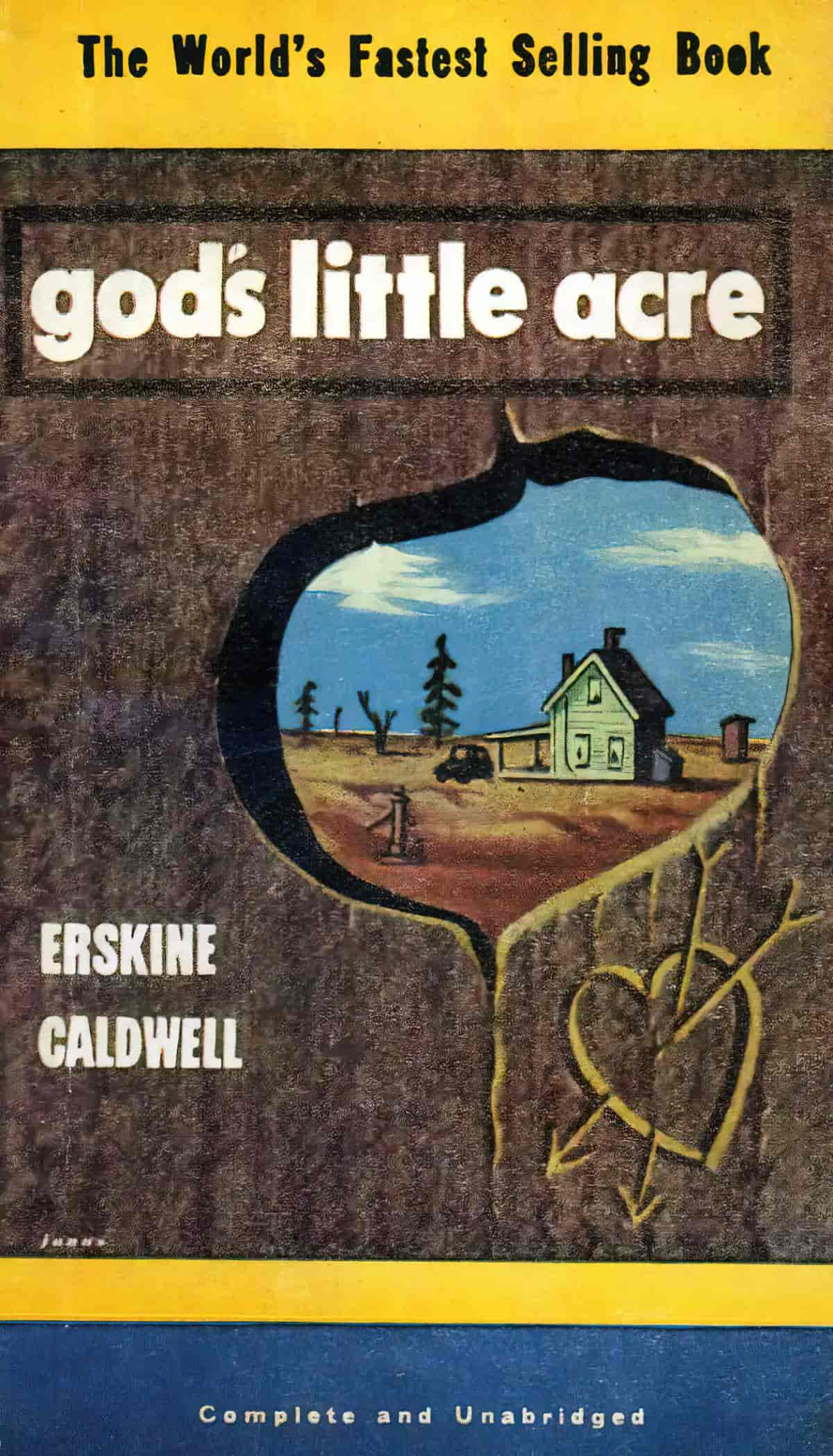

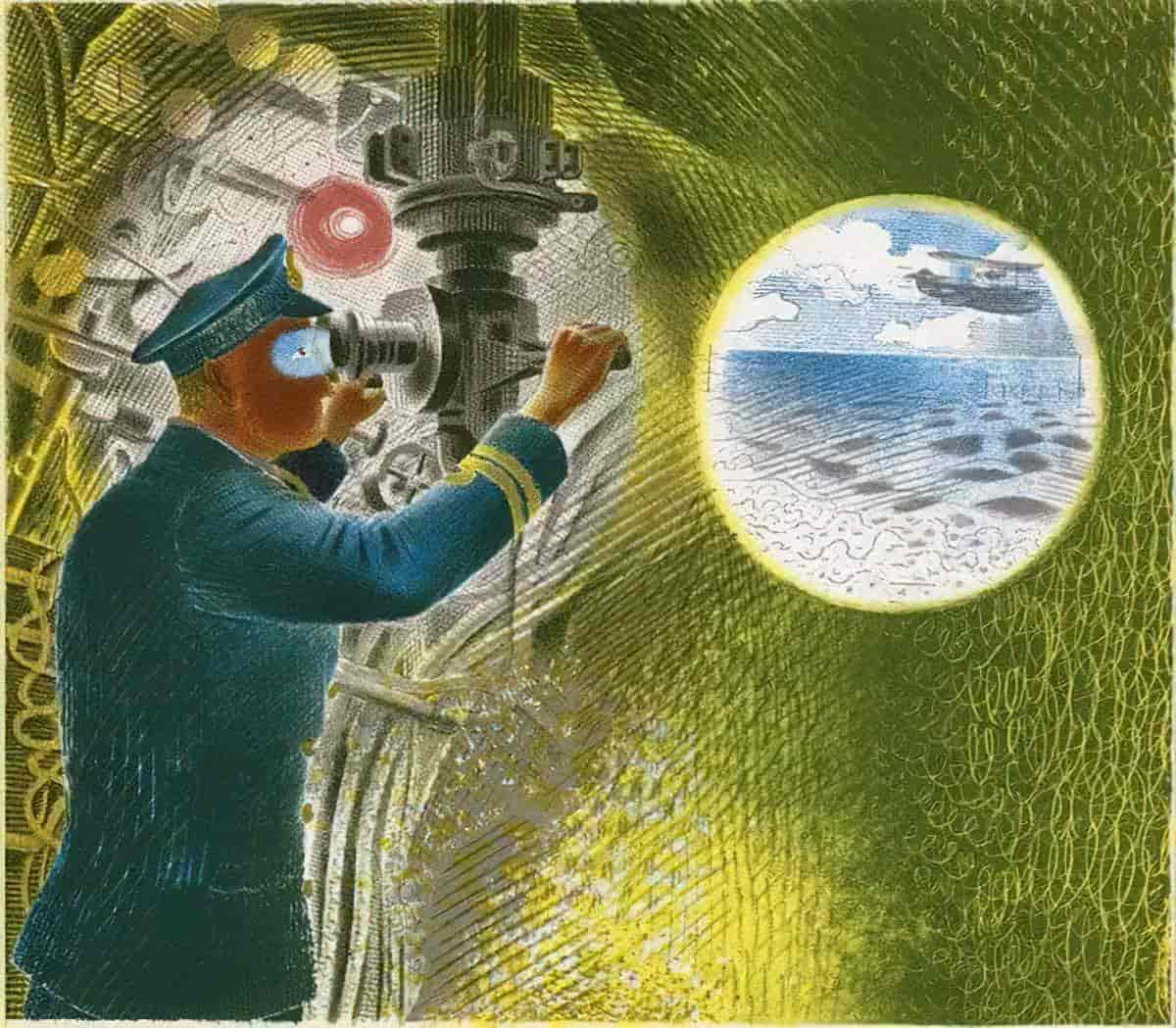

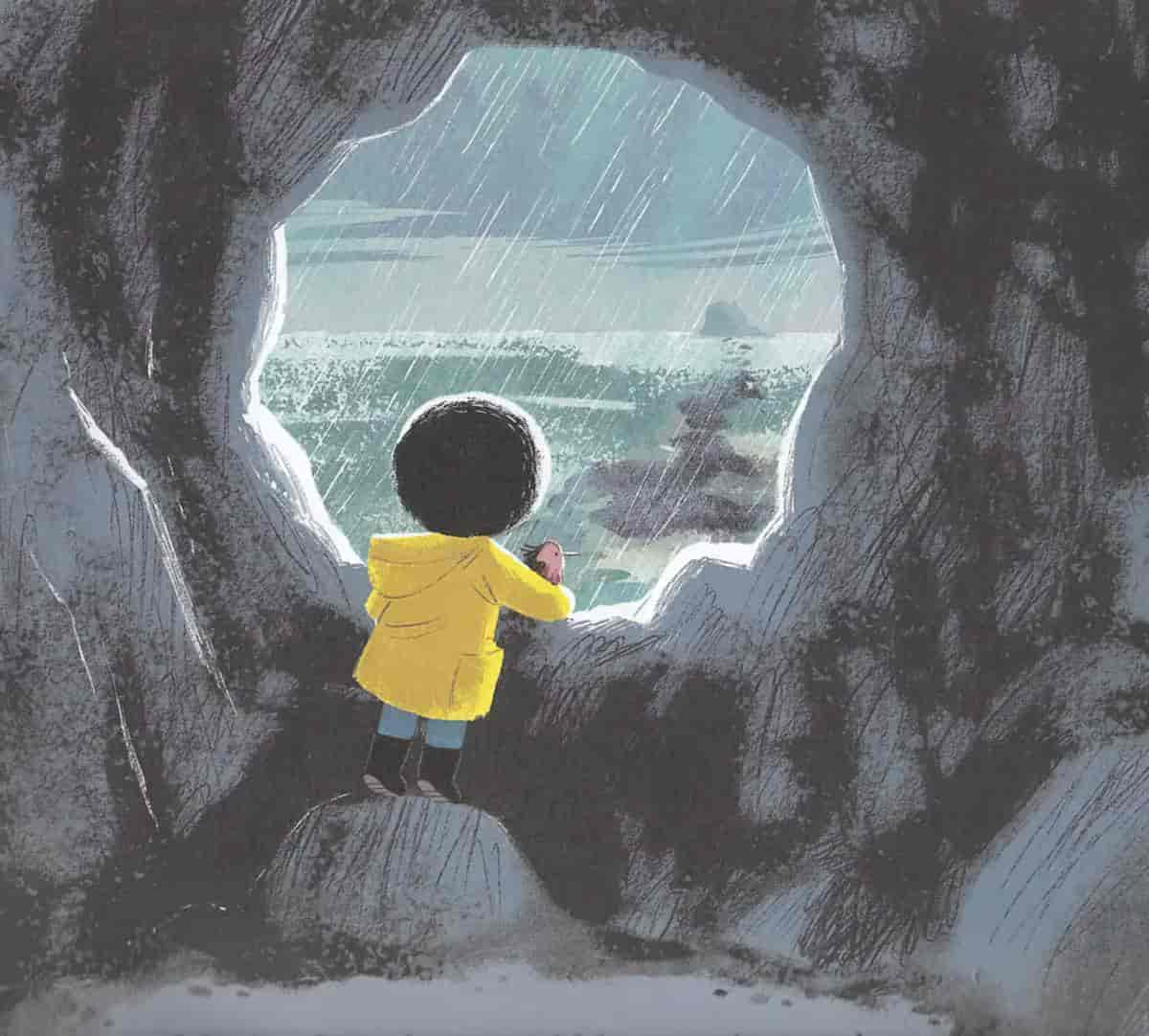

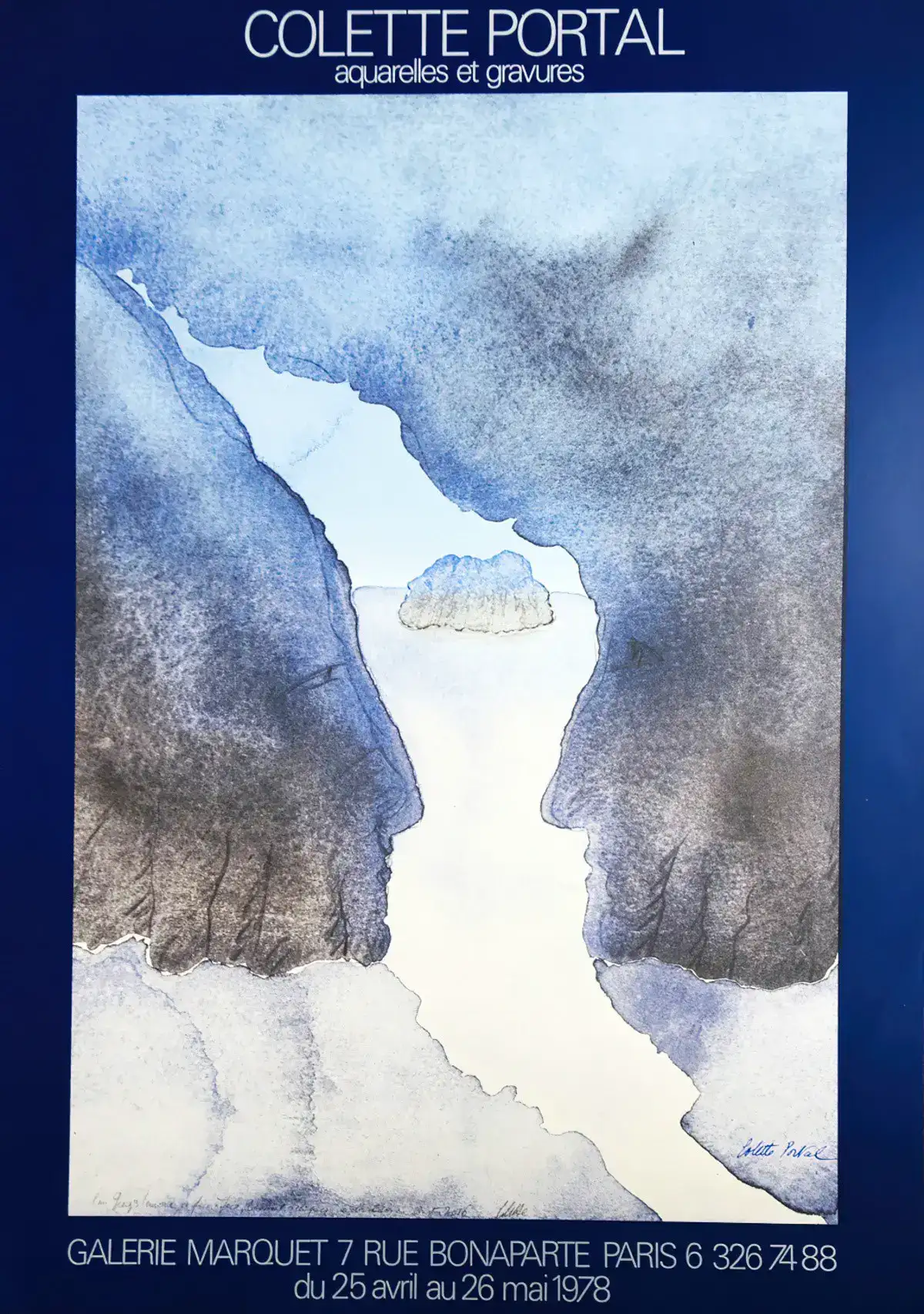

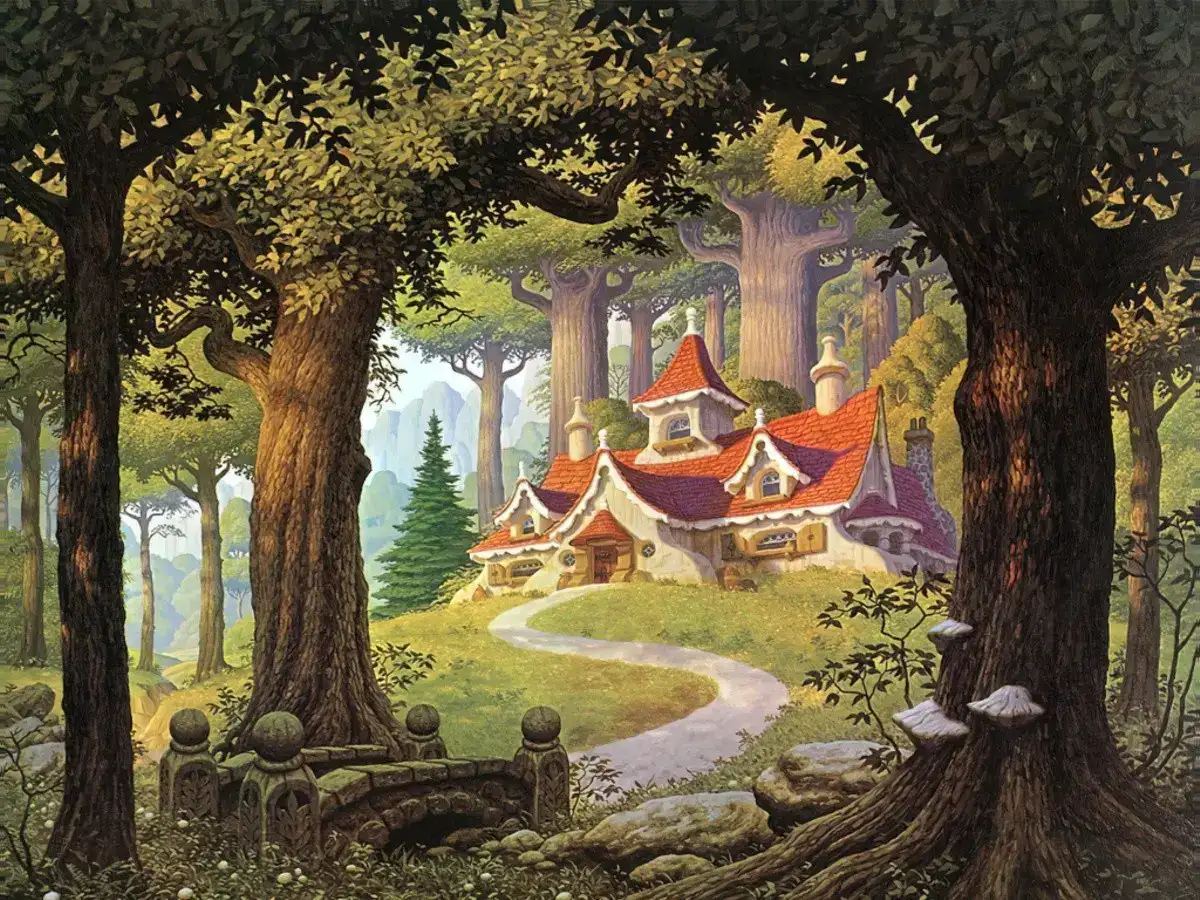

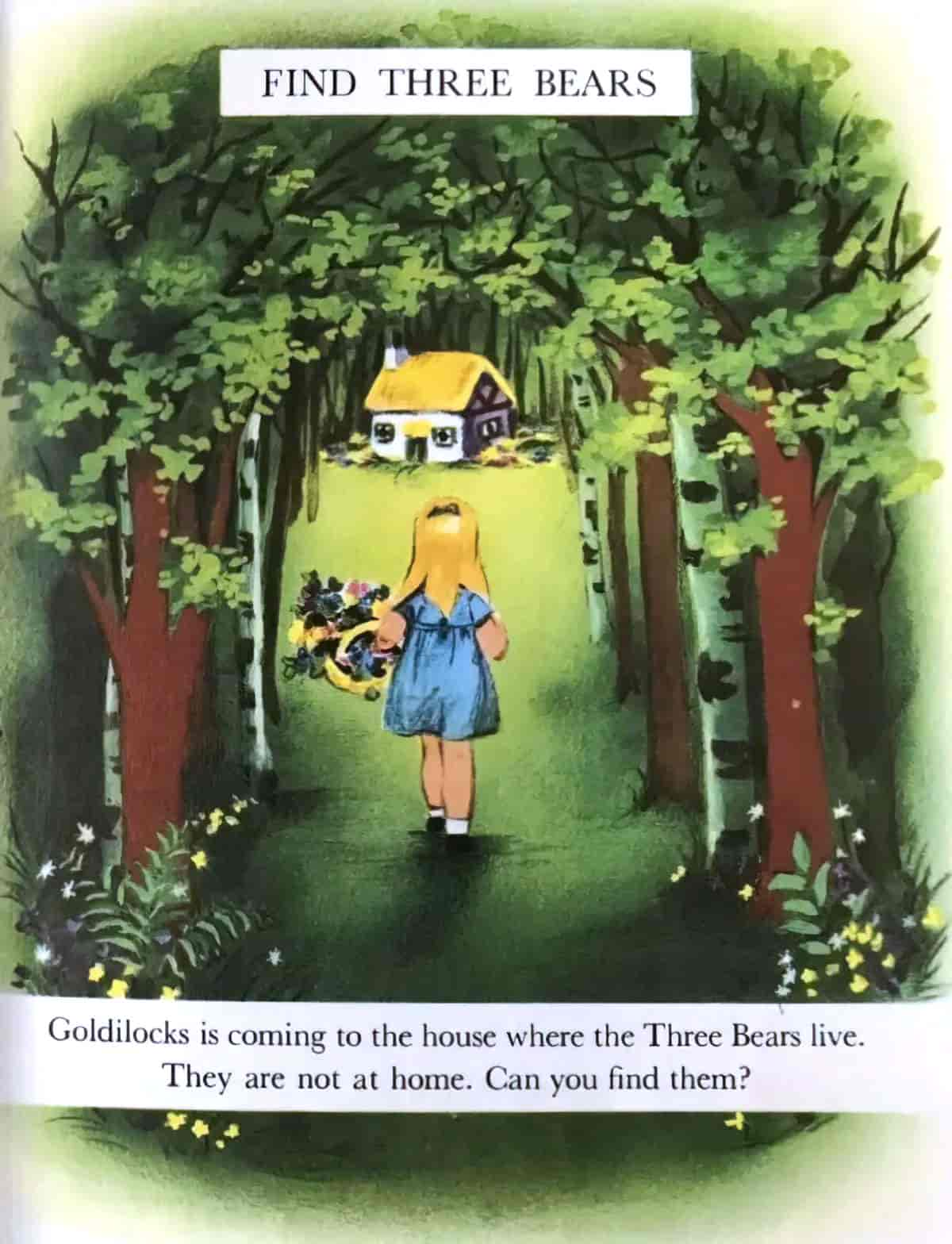

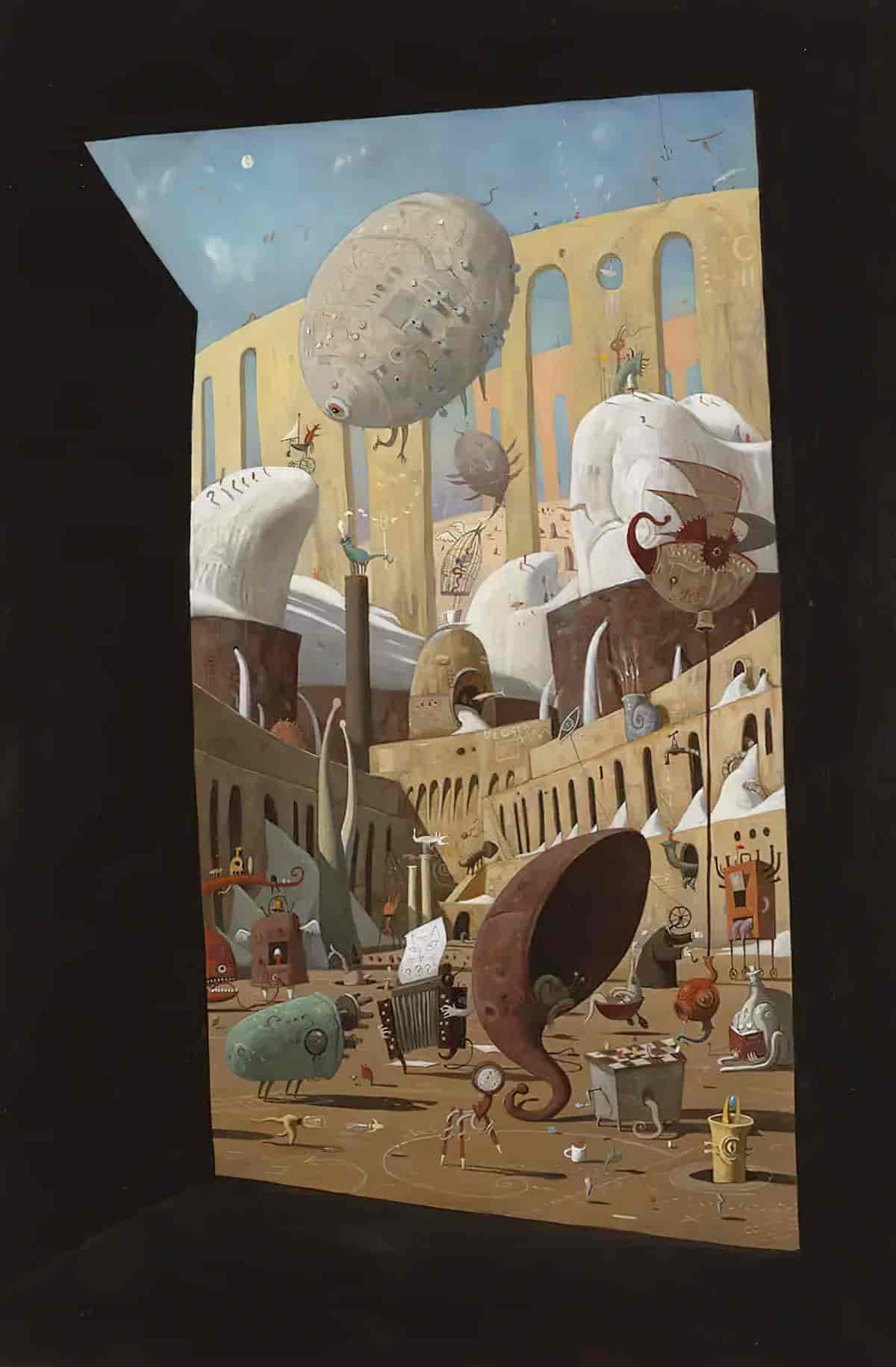

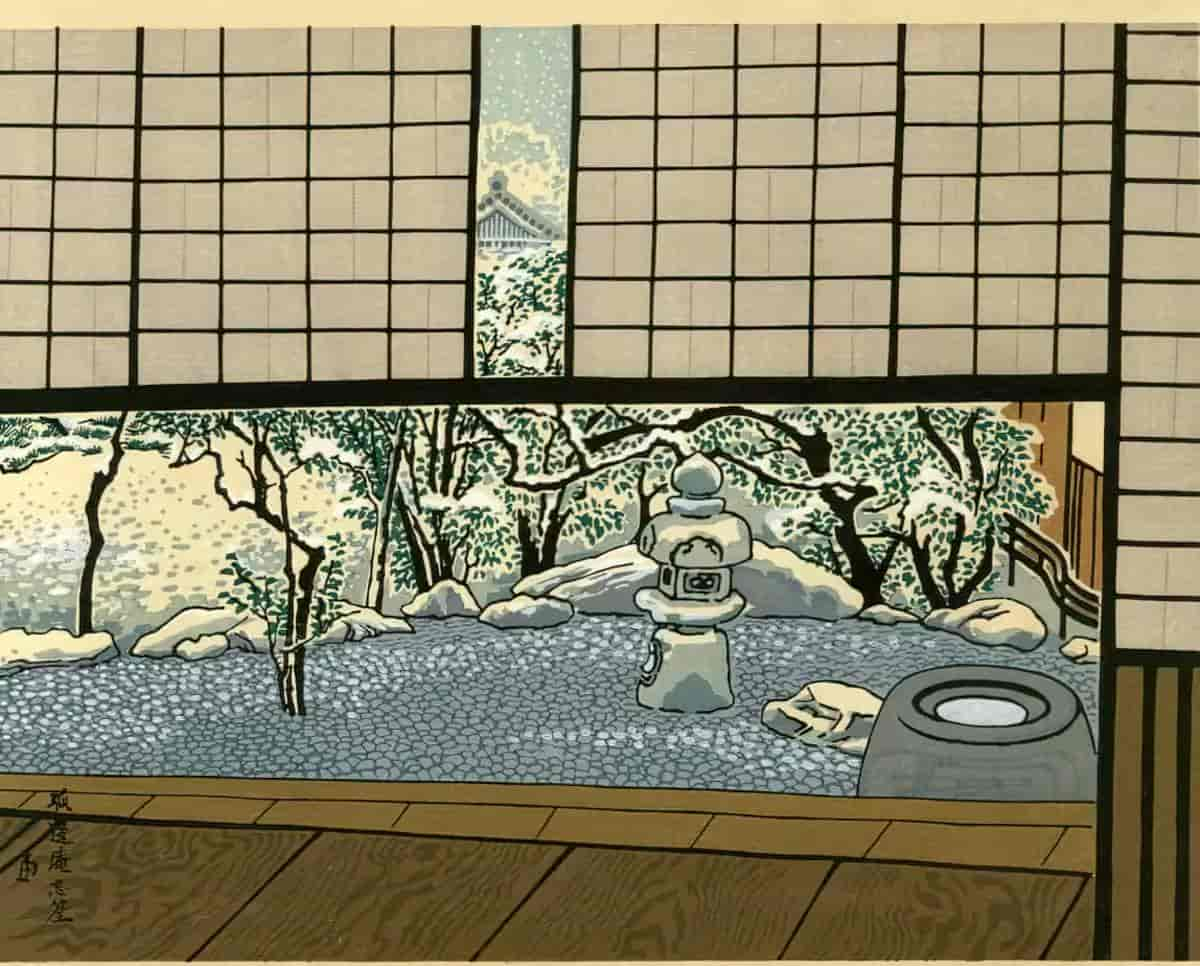

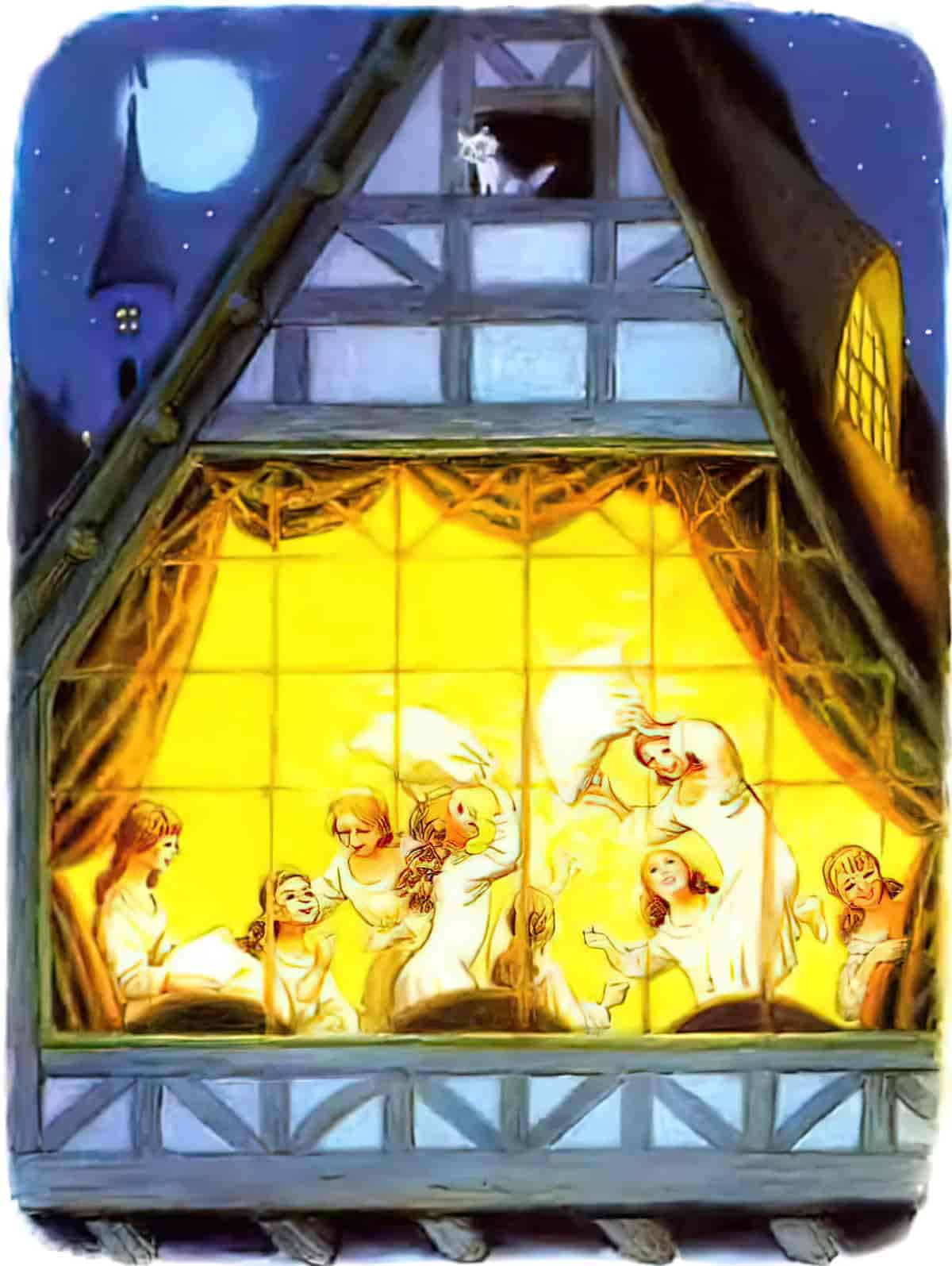

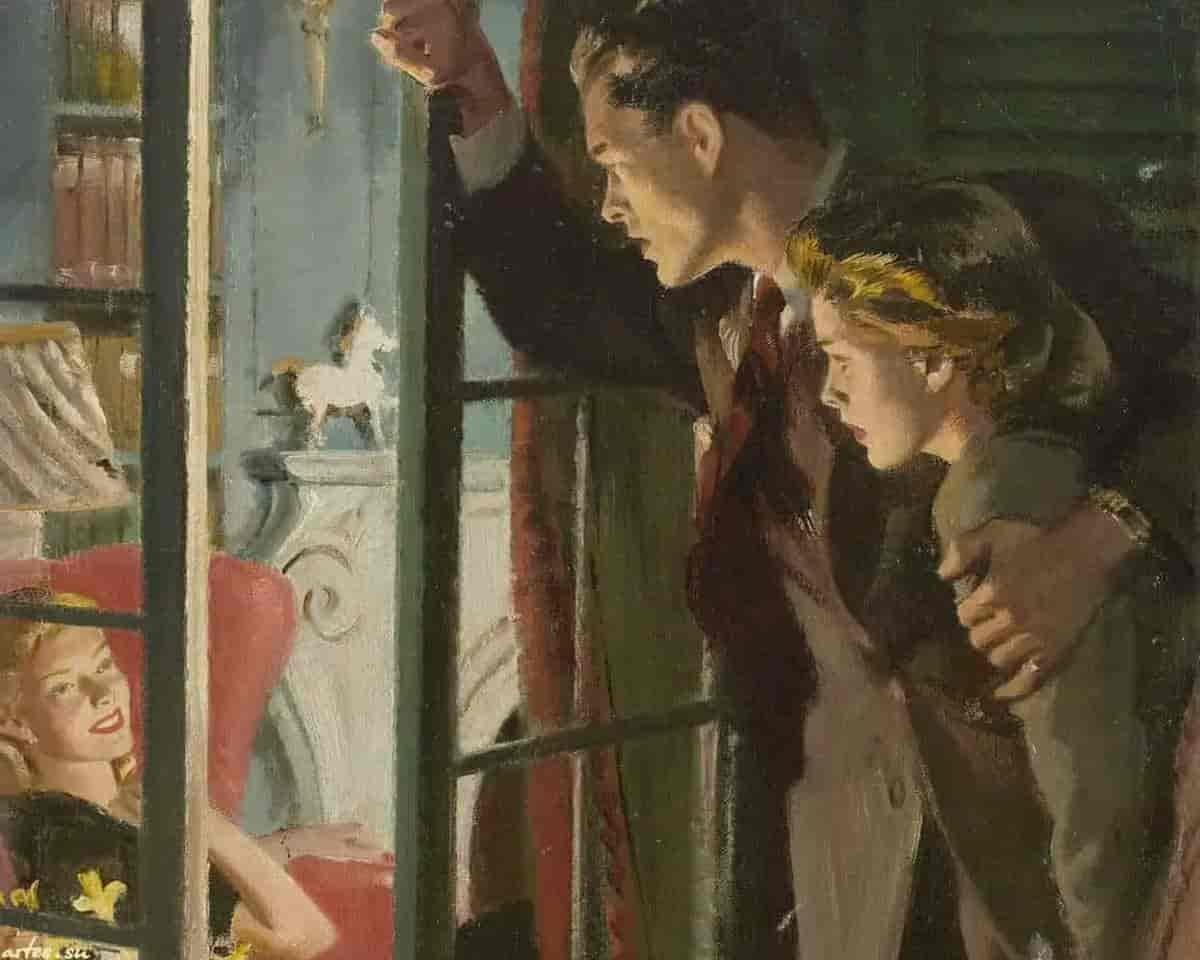

Returning now to Adrienne Adams’ beautiful illustrations, the thing that stands out to me is her perspective. Because the whole story is told from the point of view of a rabbit, there are a number of ‘peephole’ views. (At least, that’s what I call them. Is there an established name for this?) If we use the language of Postmodernism, we’d be talking about ‘framing‘.

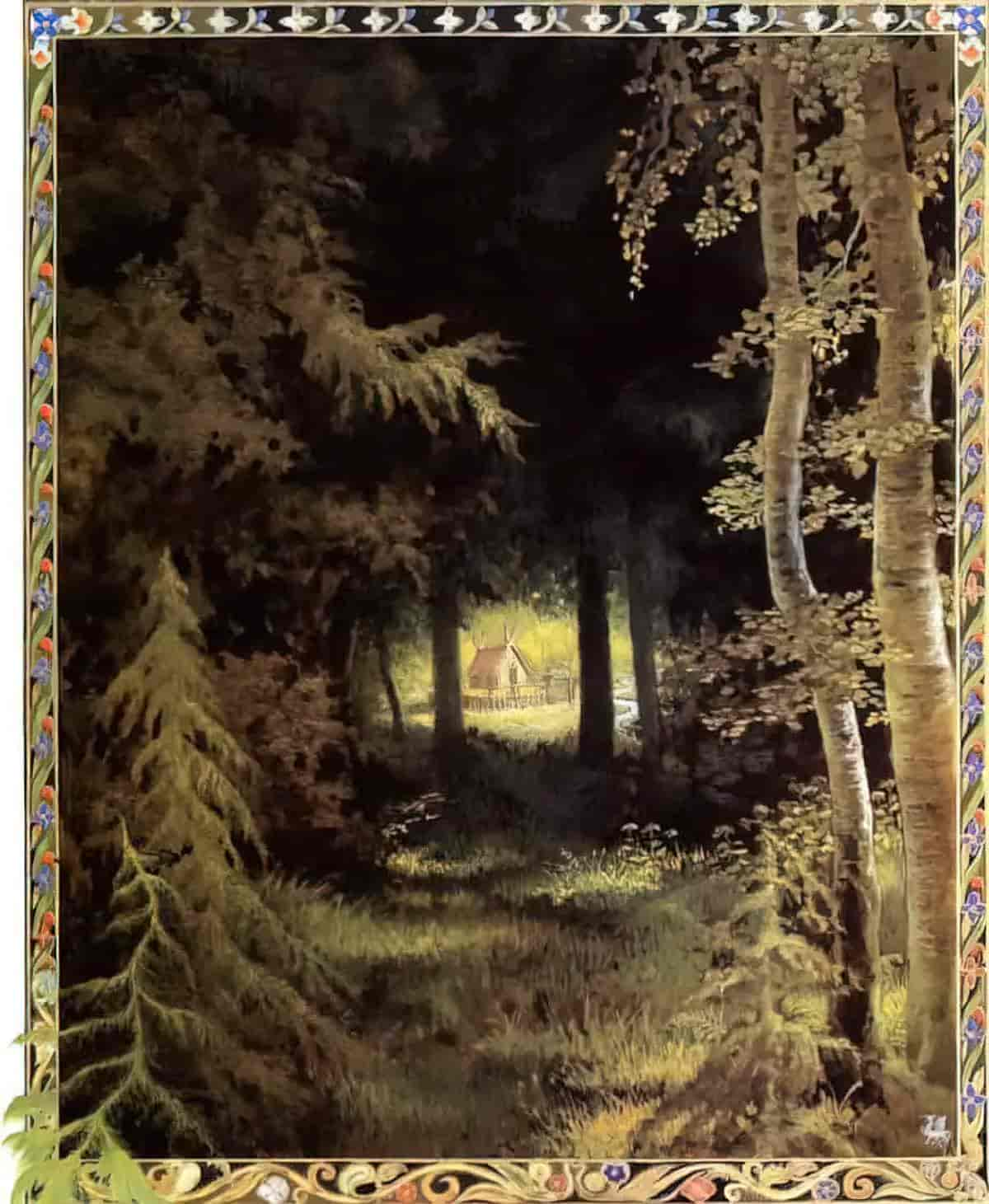

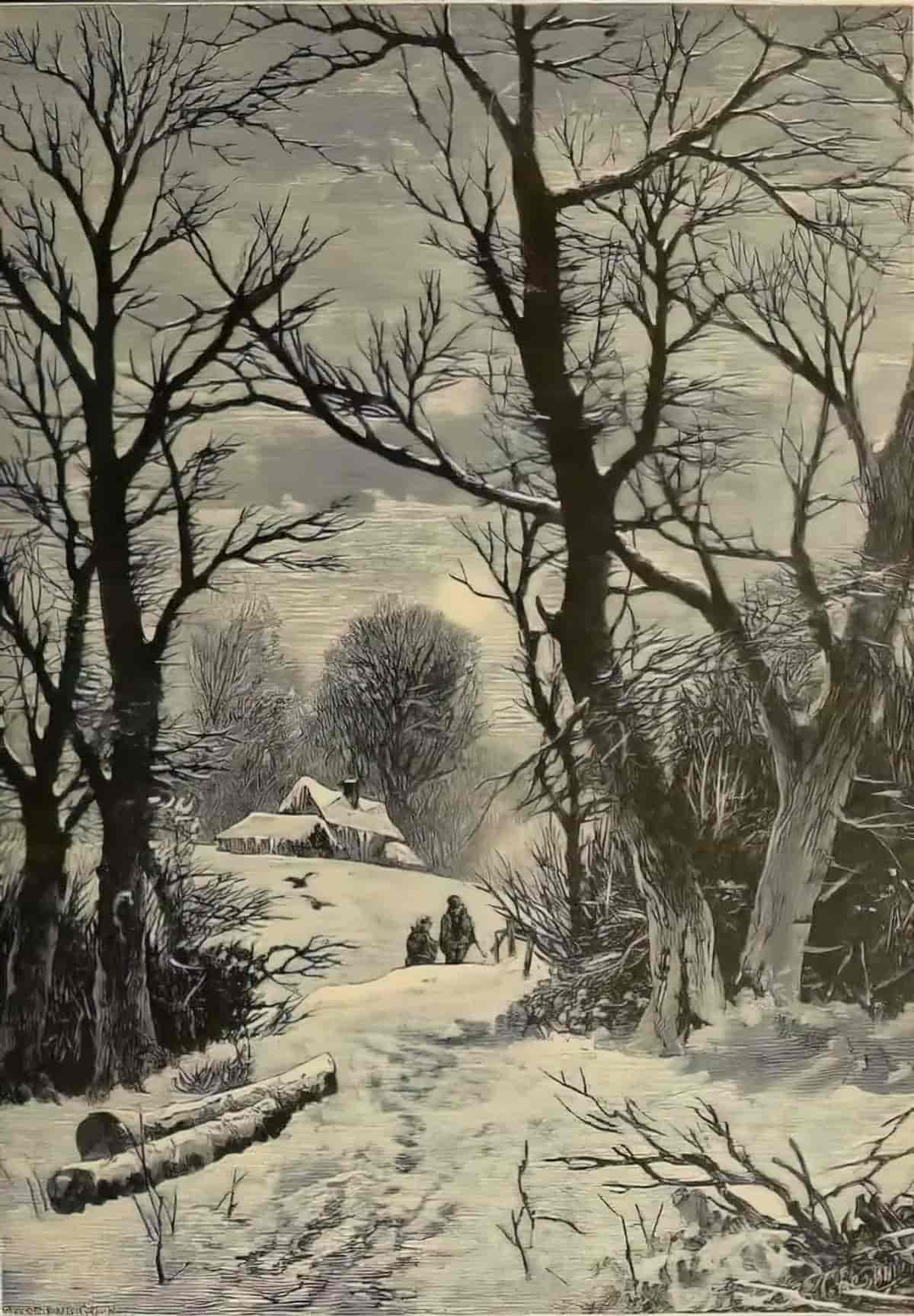

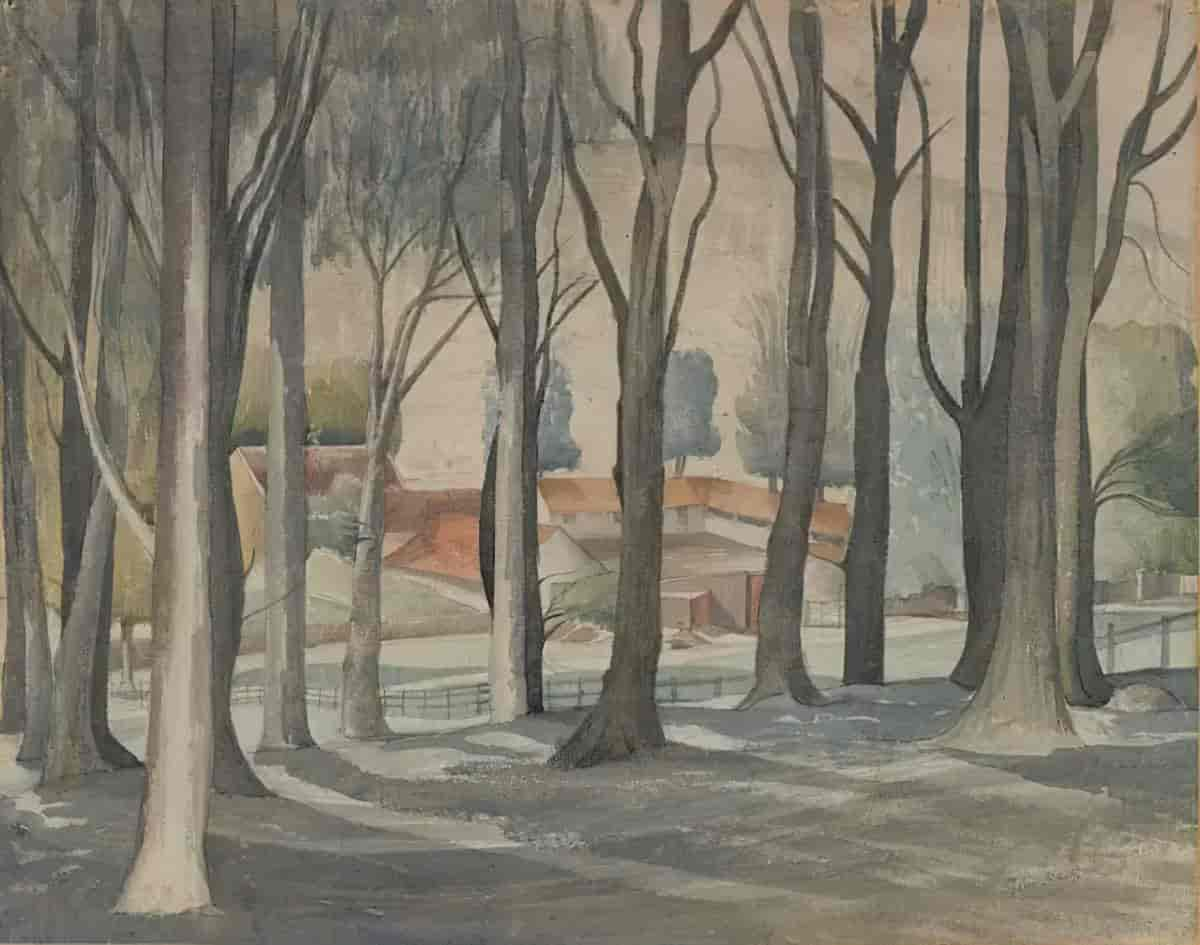

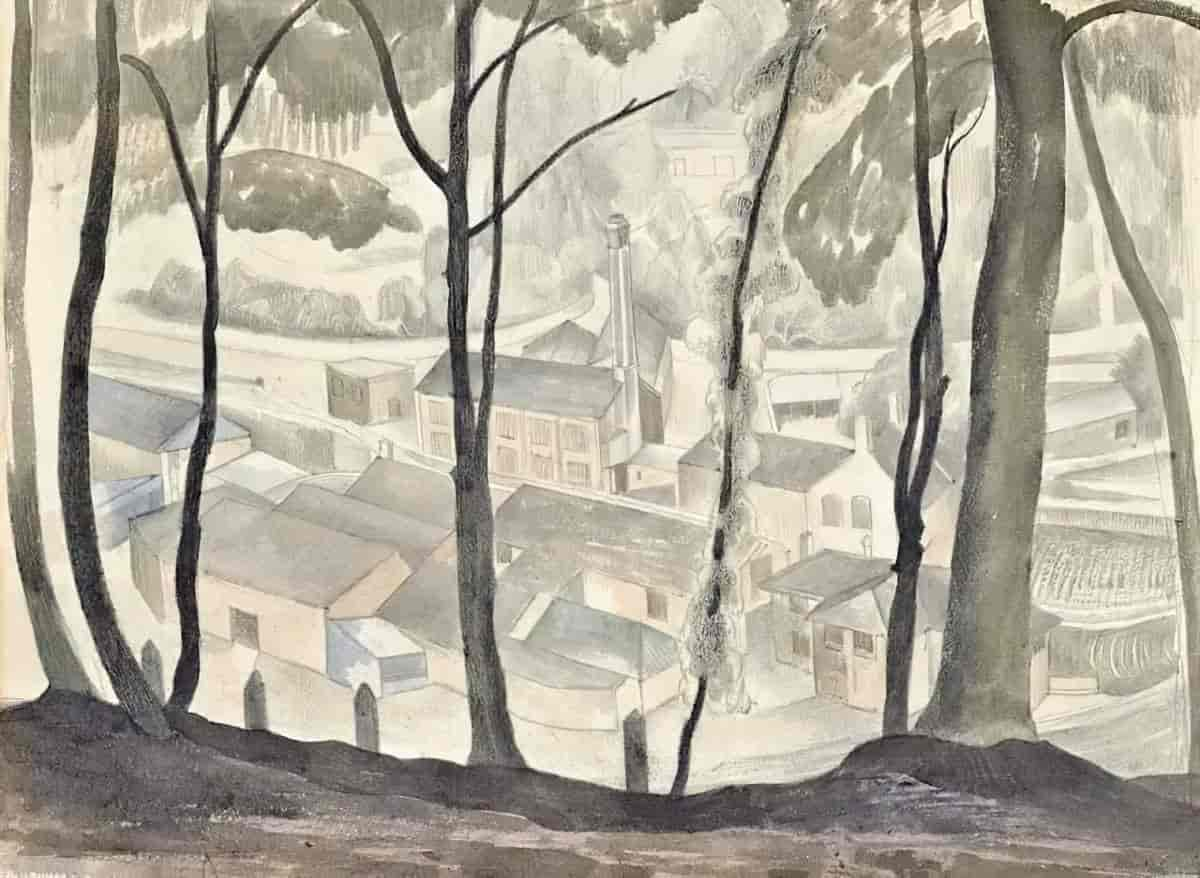

Here’s a few shots through trees:

And here’s my favourite, in keeping with the quiet humour of the book: A view through the king’s legs. This has a carnivalesque effect. The salty, bossy king who doesn’t like odd numbers is as human as any of us. Under his fancy robes he has an ordinary pair of pins:

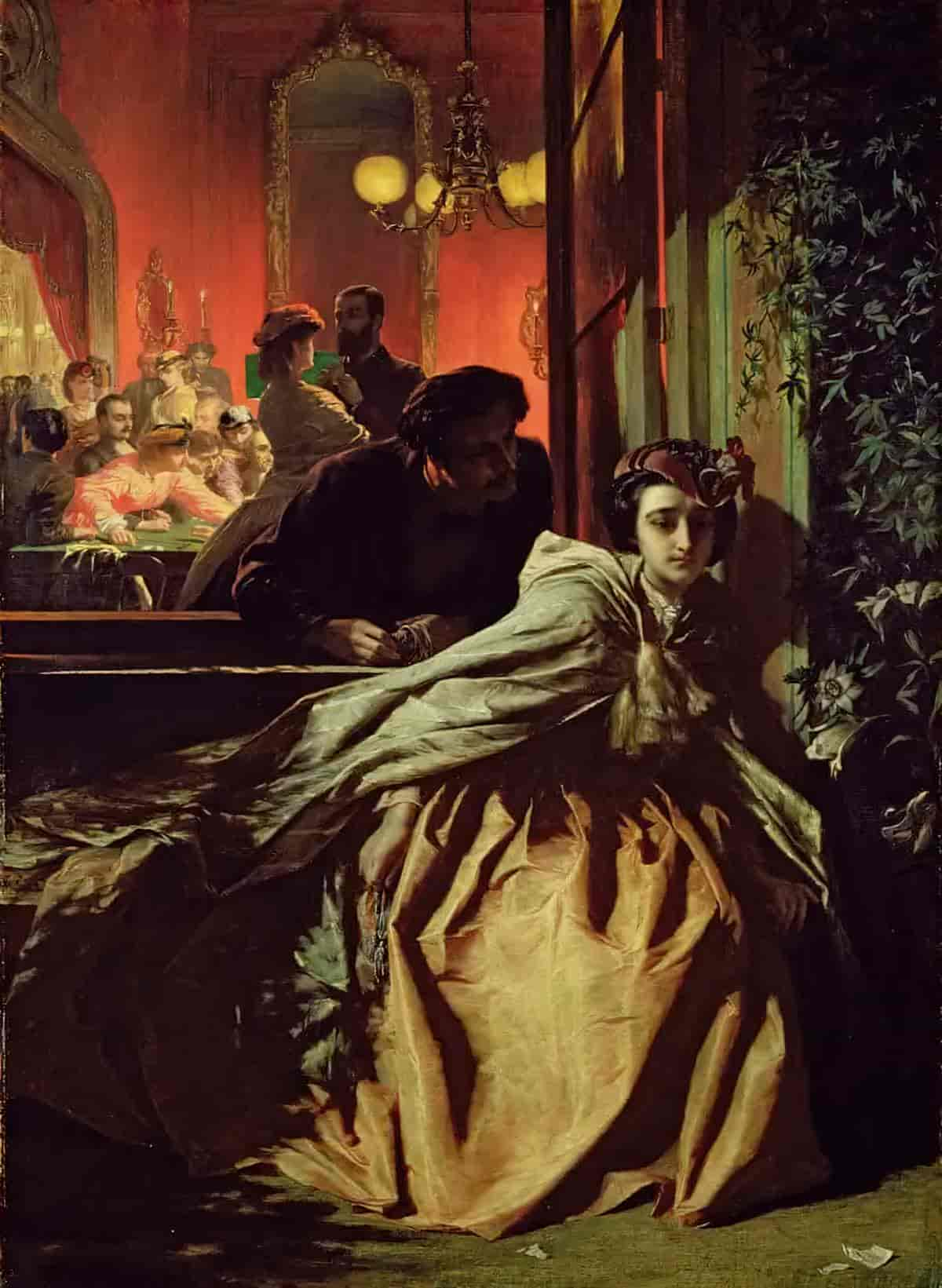

Peephole Composition In Art and Illustration

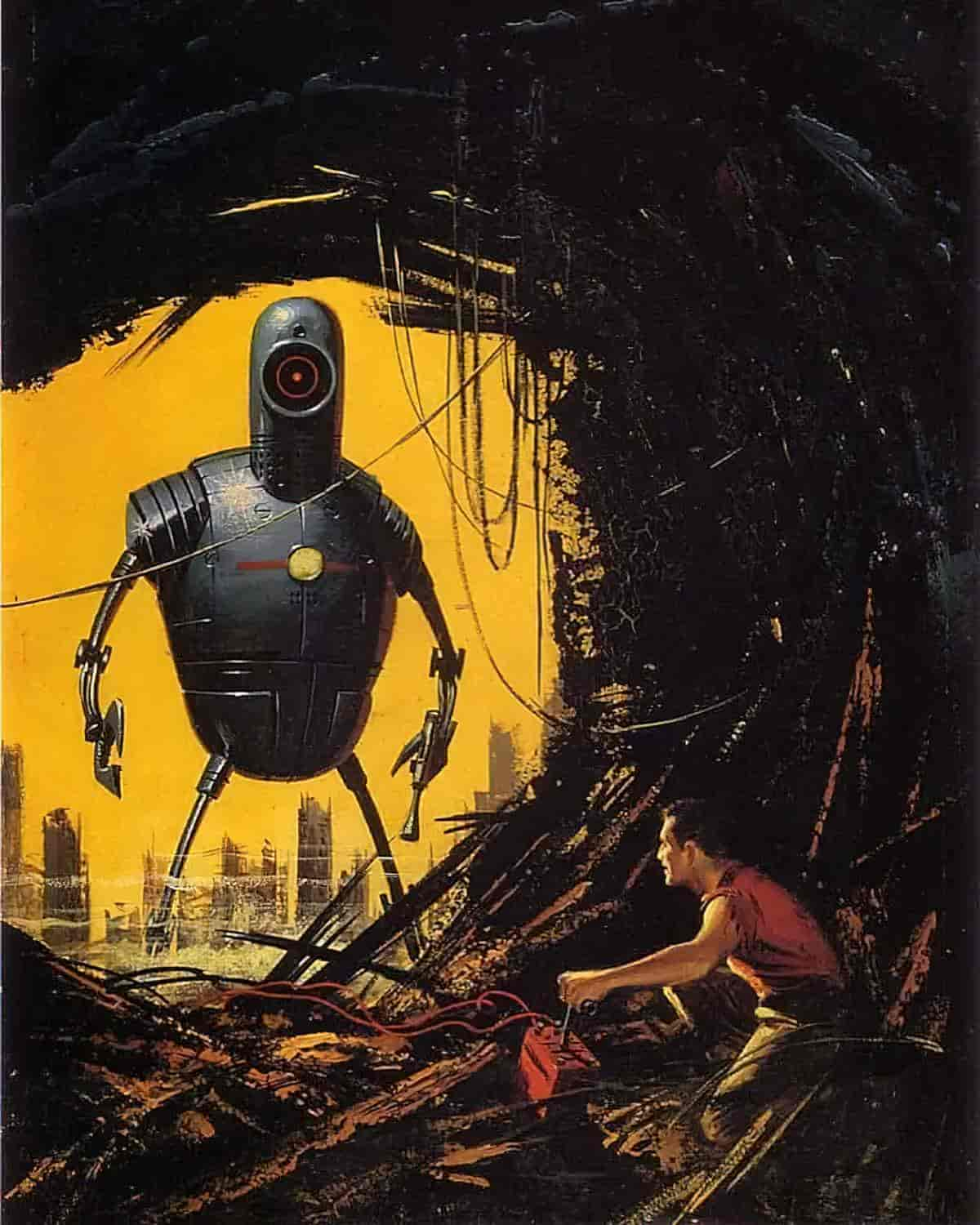

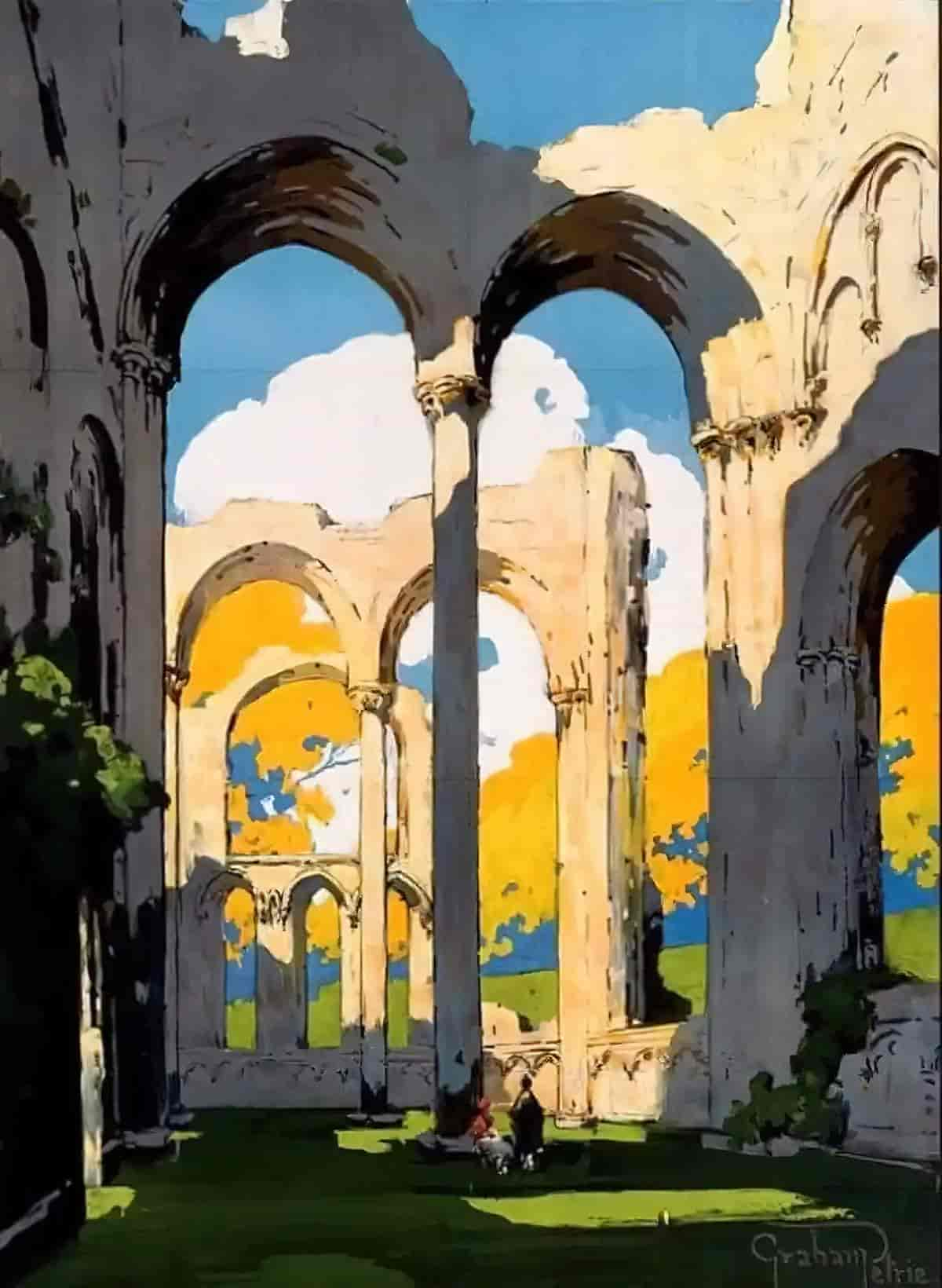

Let’s take a look at how artists and illustrators frame paintings through some kind of deliberate constraint, be it trees, windows, binoculars or any number of other intrusions.

Peephole: a small hole that may be looked through, especially one in a door through which callers may be identified before the door is opened.

Though the graphic art below focuses on peepholes — from literal holes in walls to views through trees in a forest — in literature there are established terms for describing the unsettled feeling you get when you look through something to something else.

It goes back to Freud, of course. Freud and the uncanny, or unheimlich.

Freud described the uncanny as “that class of the terrifying which leads back to something long known to us, once very familiar”. The uncanny represents the liminal space between what is capable of being understood as outward in the world and what is hidden. Though we may get a sense of the familiarity, its true connection to the past is never quite in our reach. Through repression or burying, the uncanny is never able to be fully comprehended — it can, however, be sensed or felt.

The word ‘unheimlich’ is the opposite of ‘heimlich’, which has various definitions, all related to ‘the home’ e.g. ‘belonging to the home’. The home is (hopefully) where we experience peaceful pleasure and security.

Some writers are well-known for their ability to evoke a sense of the uncanny in readers. One standout example: Shirley Jackson.

In her novel Hangsaman, Jackson repeats door scenes to evoke in readers a sense of the inbetween. (Liminal space.) These doors runction as a gateway to “the shadowy part of self reserved for the double“:

A knock on her door was a strange thing to her as the fact of the door itself… as she looked at the inside, and meant to mark the next day whether the panels outside were the same as those inside; off, she thought, that someone standing outside could look at the door, straight ahead, seeing the white paint and the wood, and I inside looking at the door and the white paint and the wood should look straight also, and we two looking should not see each other because there is something in the way…

Hangsaman, Shirley Jackson

Below is an analysis of this passage. Before reading, know that lonely college freshman Natalie Waite is the main character and she has created this imaginary friend she calls Tony. (Many readers don’t pick up that Tony is imaginary, instead coding Tony as a same-sex romantic object.)

The knocking figure lurking behind the door, somatically signalling its presence but unknowable until the door is opened, is exactly the fear Freud describes in the uncanny. Natalie’s attempts to understand the odd situation relies her ability to “look” at the inside, to “mark” the day, to observe panels from various angles, to “see” the paint, wood, and otherwise normal harbingers of reality.

To decipher what is happening, Natalie attempts to reassert the concreteness of her room and the door. Jackson’s paragraph instils the fear in not knowing where the boundary between the real and the unreal lays, and leaving the uncertainty open after establishing the obvious.

The “we two looking” are Natalie and Tony, not yet able to meet due to that “something in the way,” whether it be logic, reasoning, perception, or simply, a locked door.

Beyond the locked door is the distance between two selves and mental activities. To look at each other would be to finally confront the shadowy other, an act that Natalie cannot fully confront.

What is beginning to emerge in this passage, though, is an inability to separate the real world self from the non reality. It is unclear who the “I” in the passage is, whether Natalie or Tony, real self or shadowed visage.

“Homespun” Horror: Shirley Jackson’s Domestic Doubling by Hannah Phillips

Useful words from that analysis:

Somatic psychology: The study of the mind/body interface, the relationship between our physical matter and our energy; the interaction of our body structures with our thoughts and actions.

Non reality: A place, situation, etc. that is not reality.

Visage: A person’s face or facial expression, with reference to the form or proportions of the features. And here it means the manifestation, image, or aspect of something. (A metaphorical face, for things which don’t normally have faces e.g. buildings or parts of architecture.)

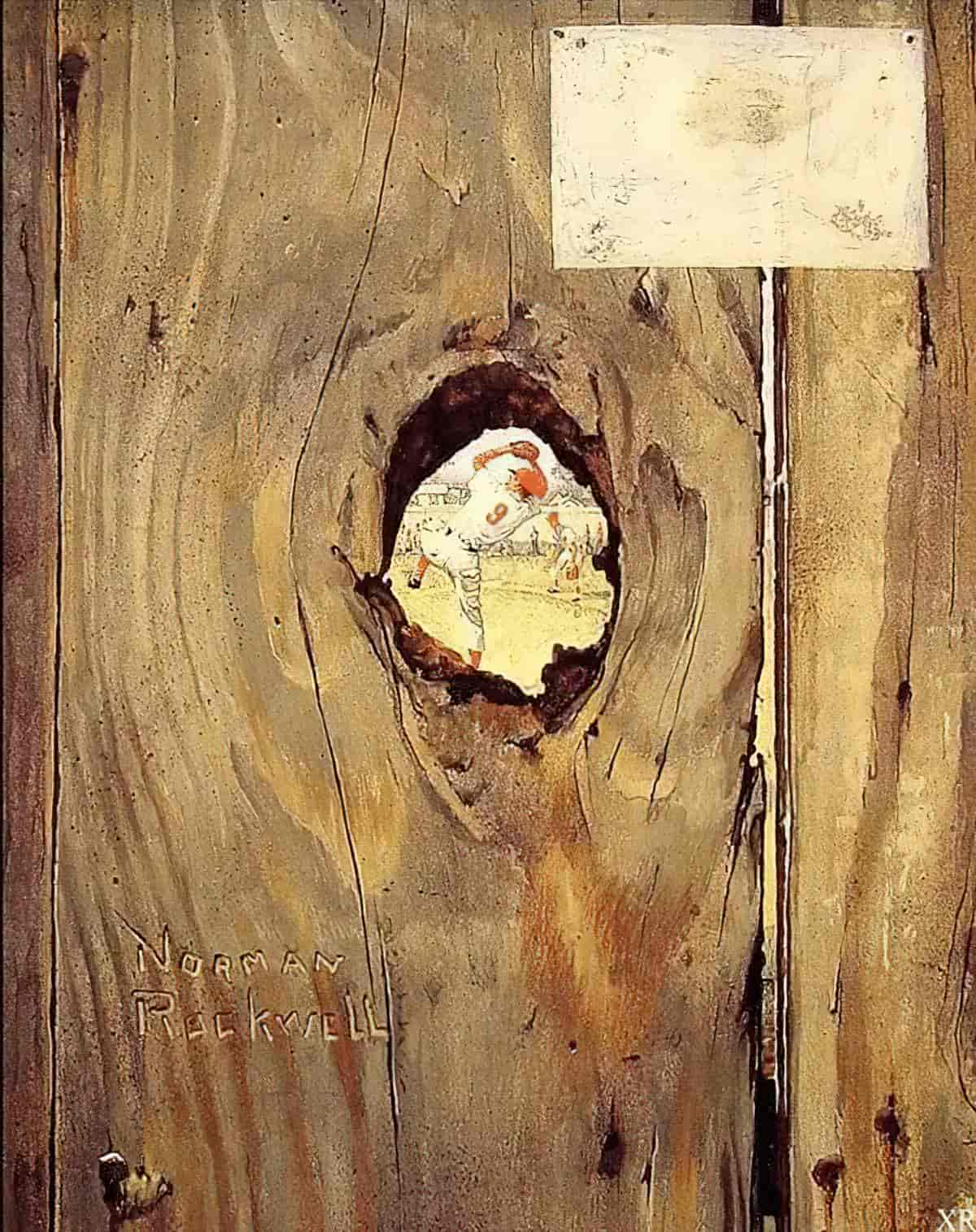

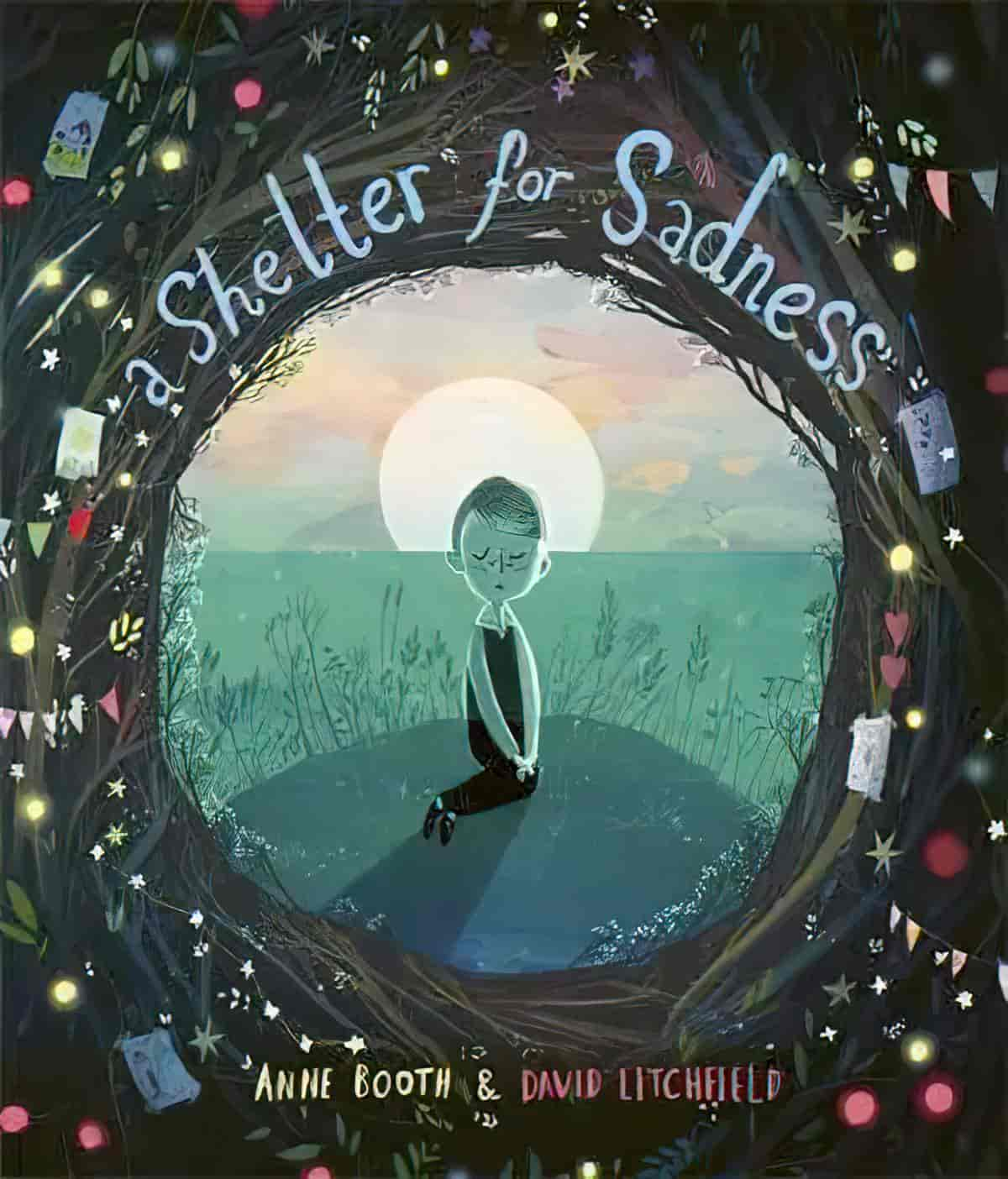

VIEW THROUGH A PEEPHOLE OR VIEWFINDER

A poignant and heartwarming picture book exploring the nature of sadness, beautifully captured by David Litchfield’s stunning illustrations.

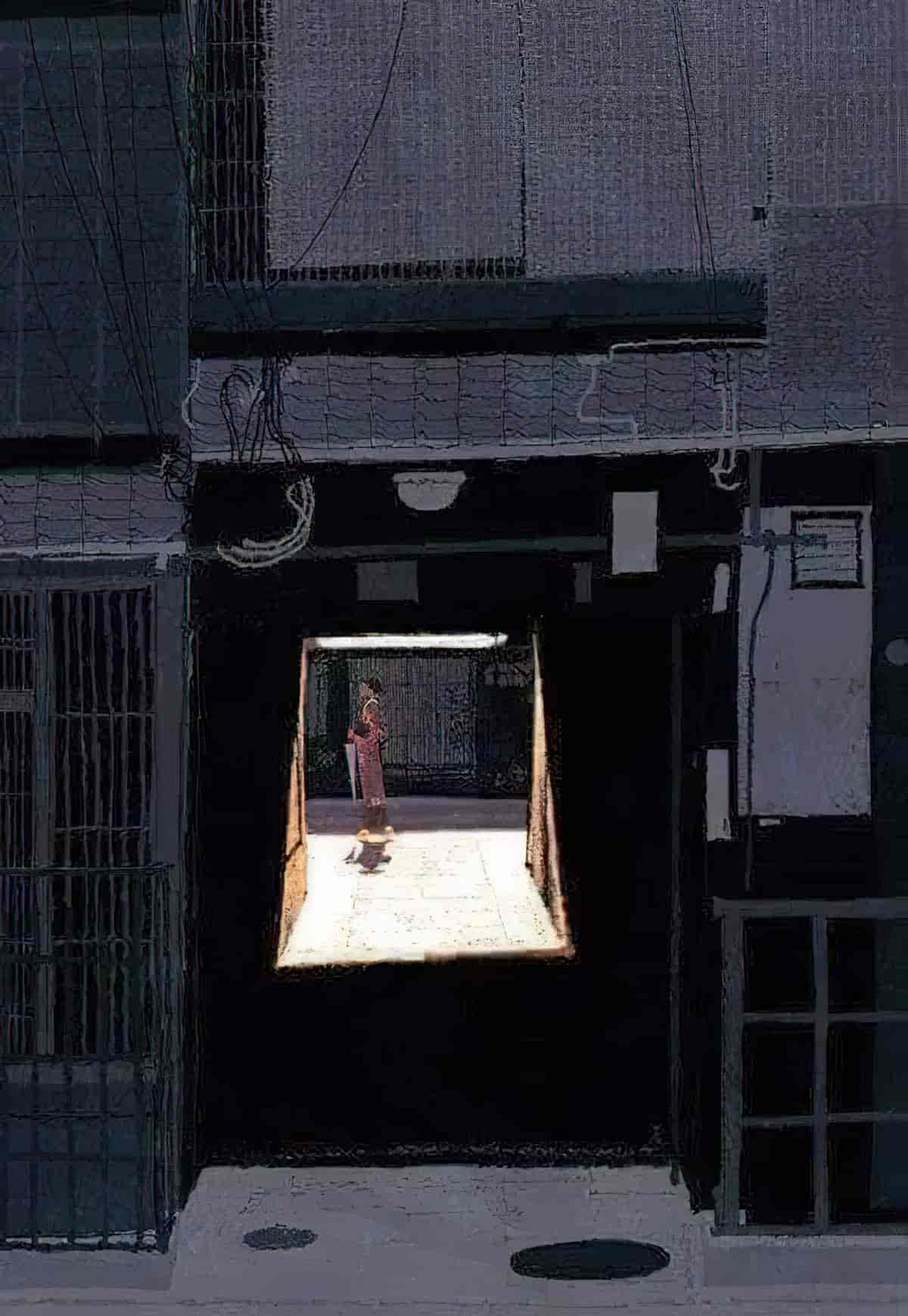

Corridors create a creepy peephole effect, which explains their popularity in horror (and in spoof horror).

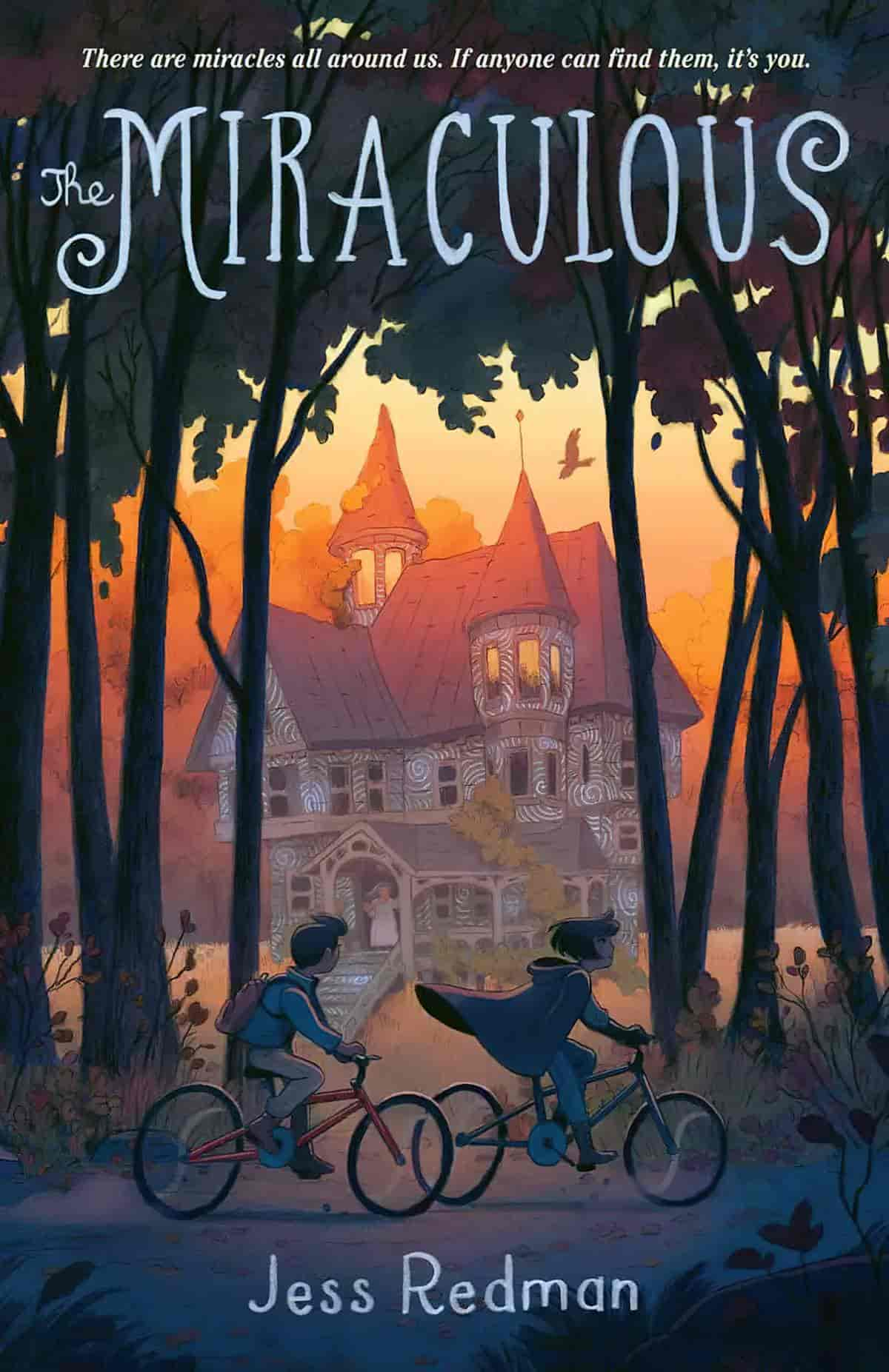

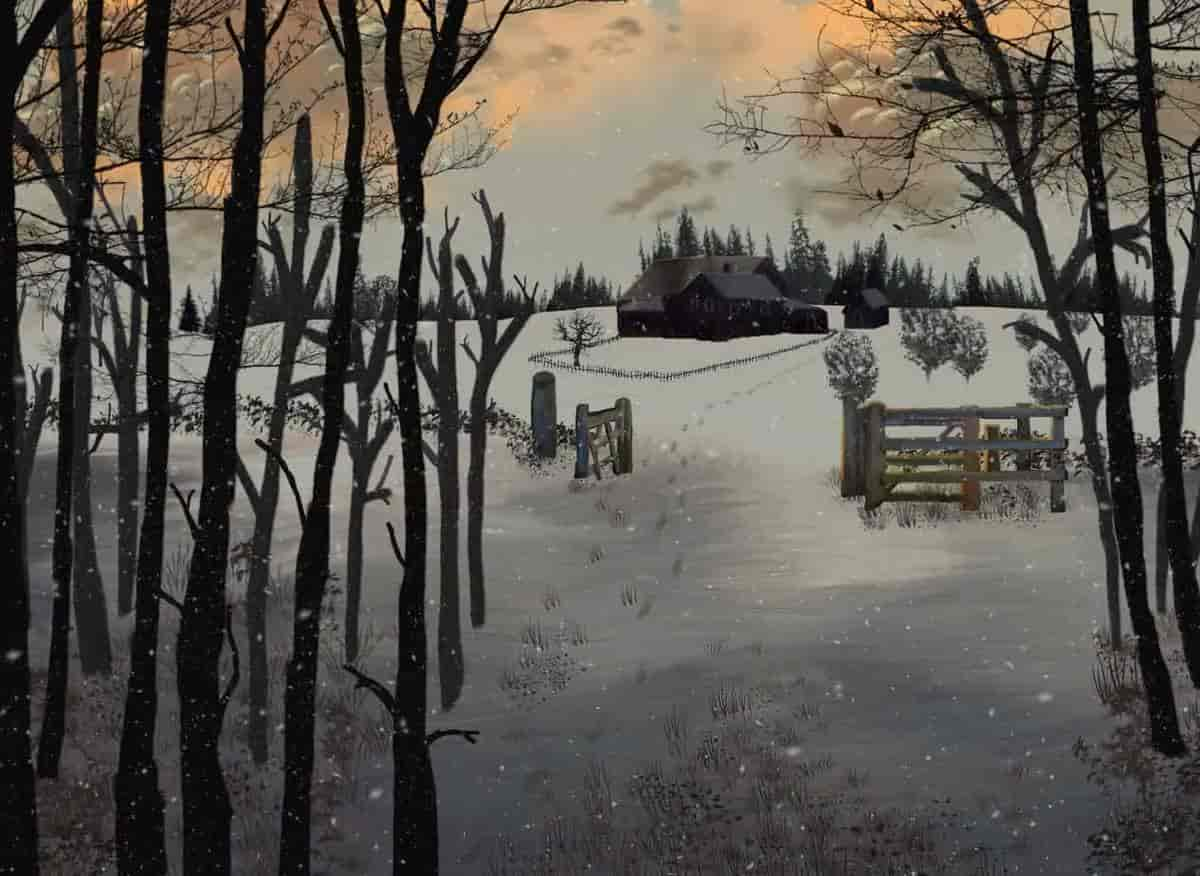

A VIEW THROUGH THE TREES

In The Widow’s Broom, a picture book by Chris Van Allsburg, the ‘camera’ moves around to afford readers various views of the story. In the image below, the climax, the viewer has been taken into the trees. We are now seeing something ominous take place, but Van Allsburg makes the axe-weilding axe even creepier by positioning readers as eavesdroppers… who live in the woods. This is a subtle but highly effective way of achieving ominous vibes to a work of art.

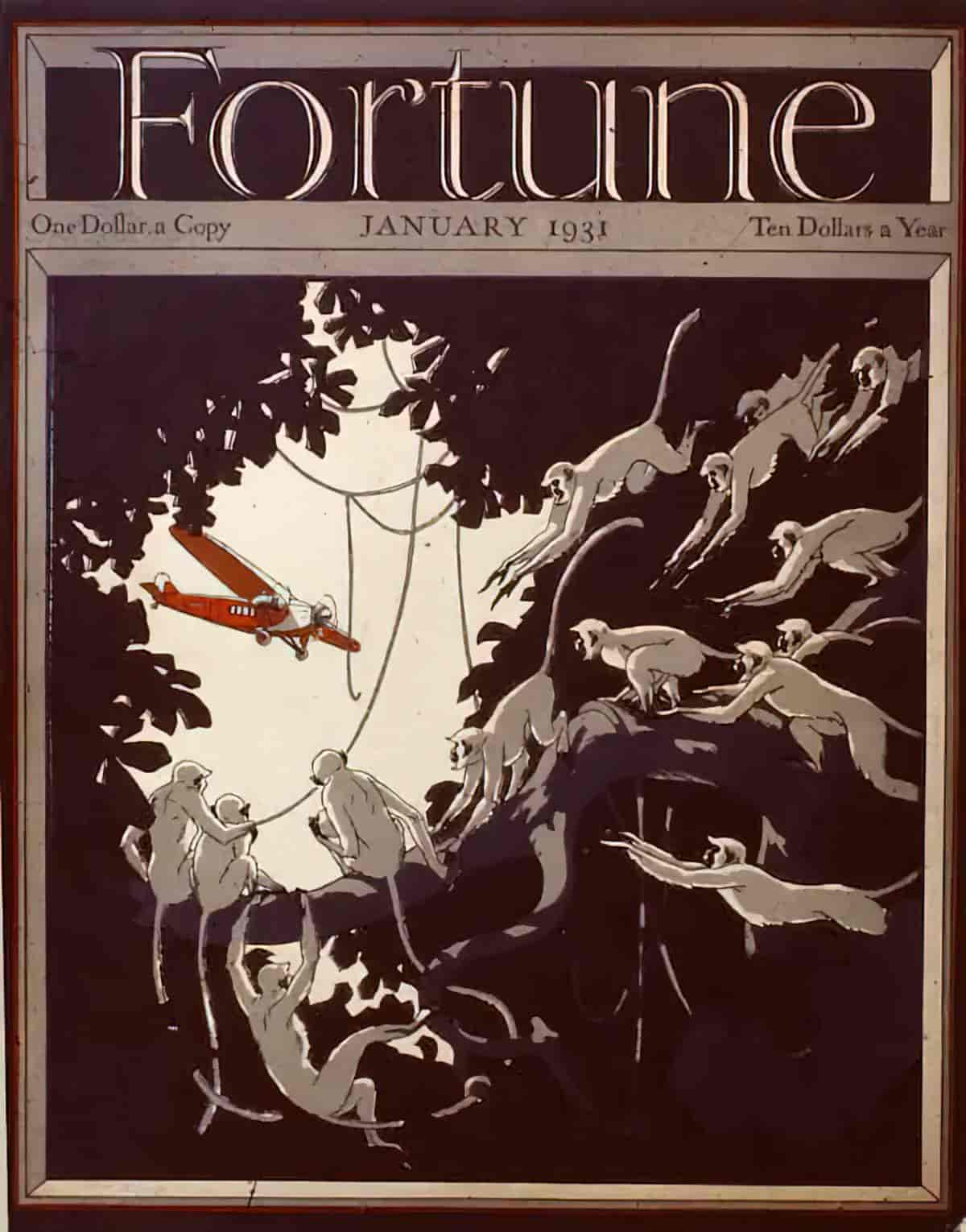

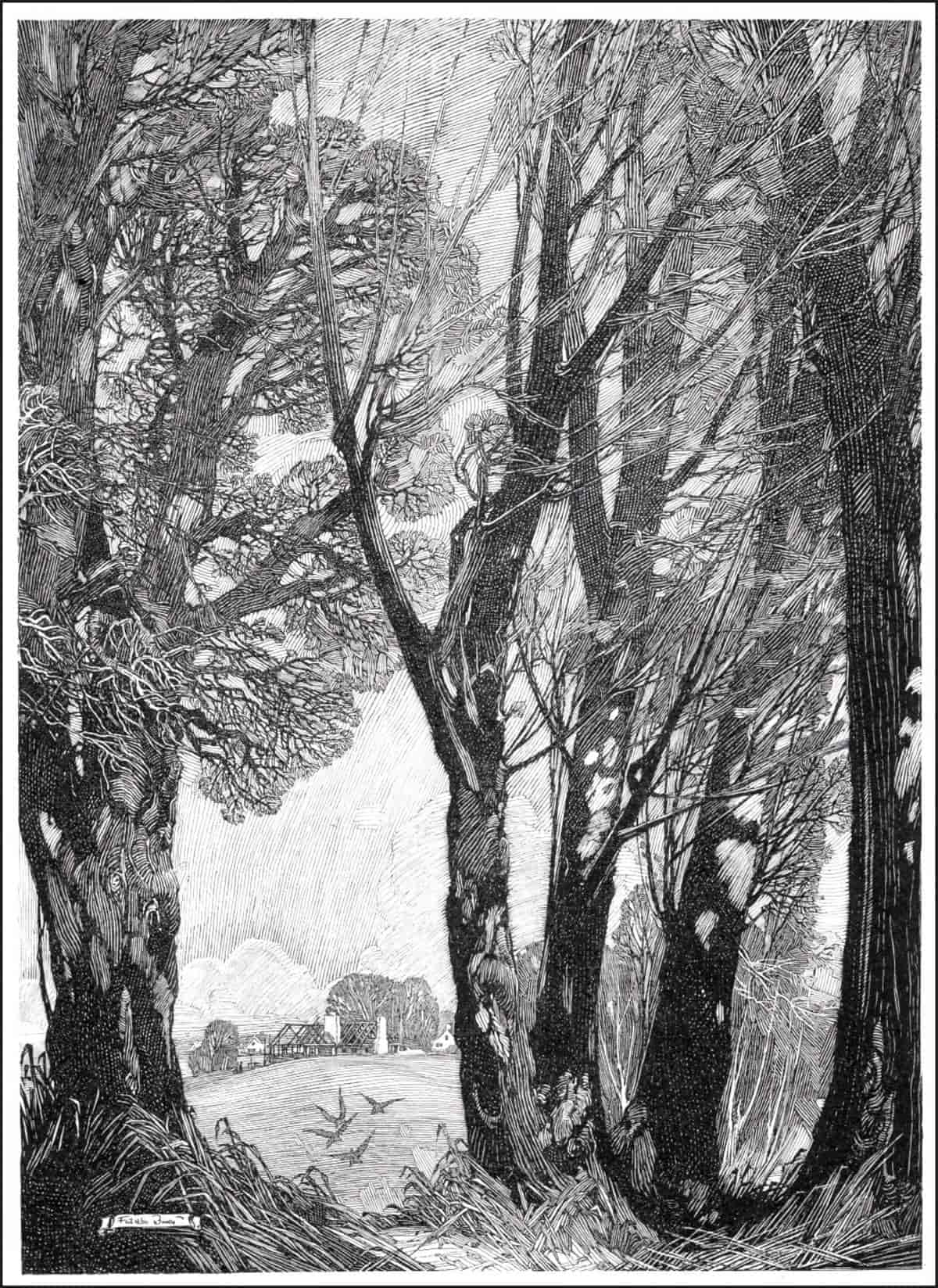

Here are further examples of views through trees. Someone is spying on us. Or is it us, doing the spying? Like matter in quantum superposition, this composition places the viewer in two psychological positions at once.

Every particle or group of particles in the universe is also a wave — even large particles, even bacteria, even human beings, even planets and stars. And waves occupy multiple places in space at once. So any chunk of matter can also occupy two places at once. Physicists call this phenomenon “quantum superposition,” and for decades, they have demonstrated it using small particles.

Live Science

The effect is almost always unsettling.

I utilised this fairly common composition myself in Lotta: Red Riding Hood. Sure enough, something bad is about to happen in this Little Red Riding Hood re-visioning.

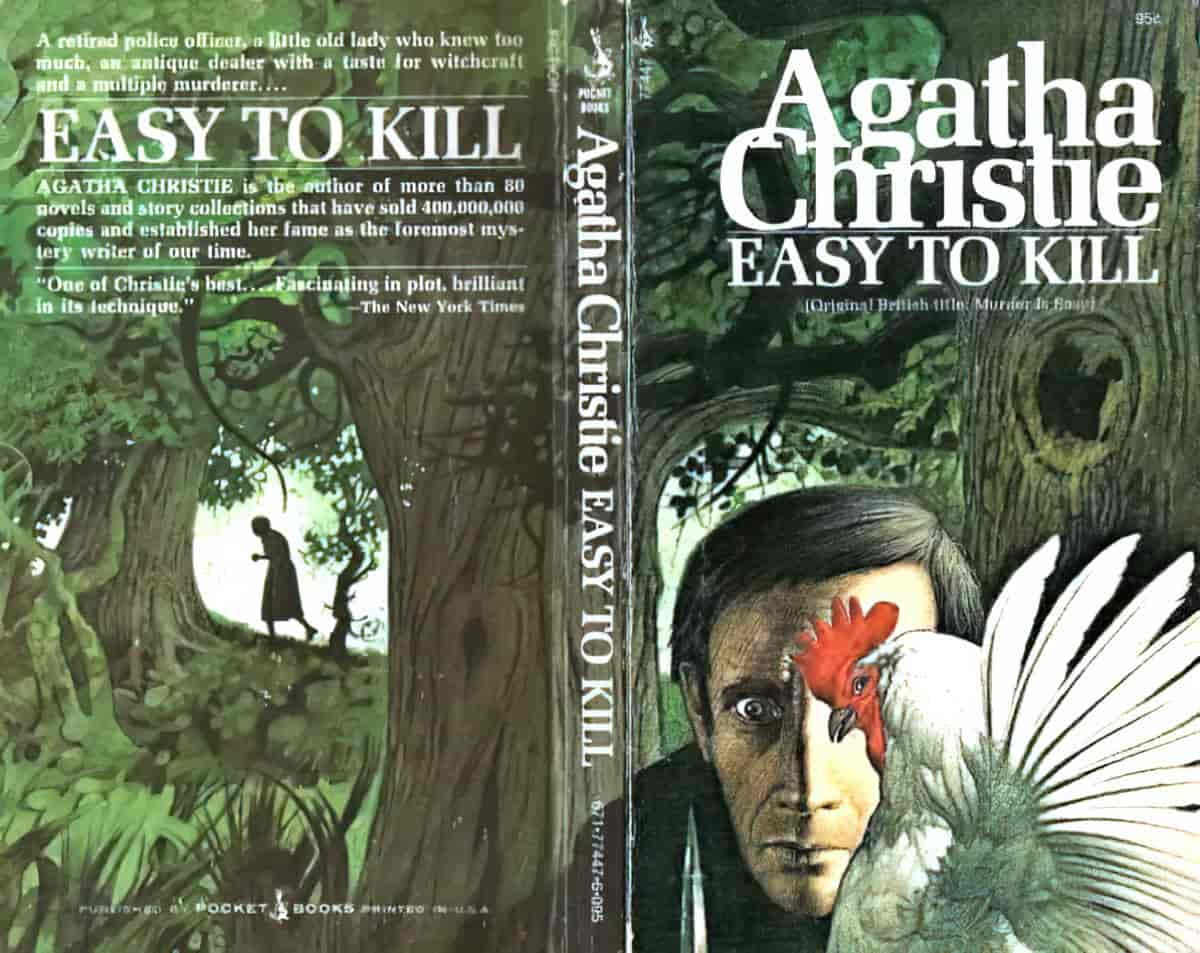

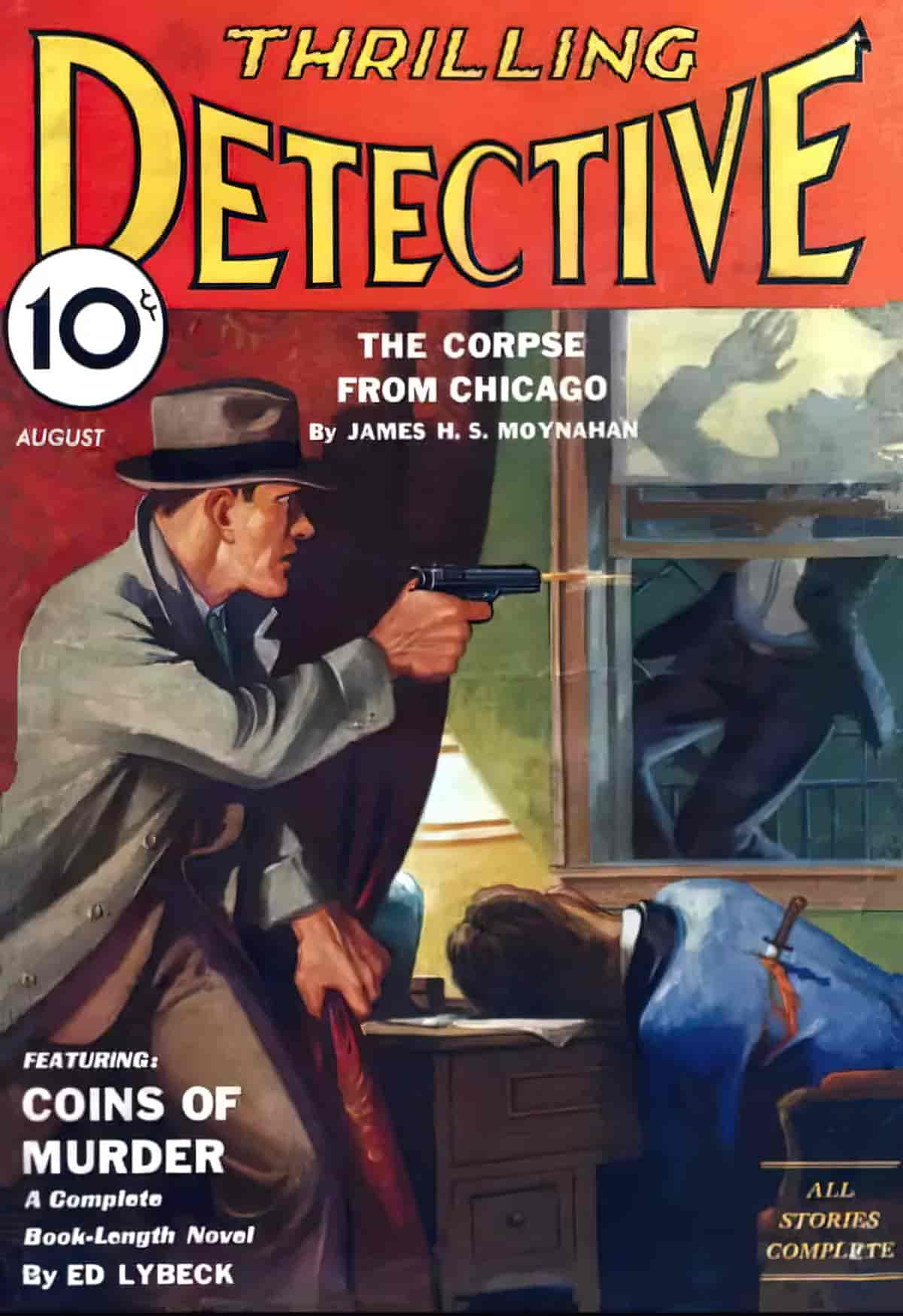

Tom Adams illustrated the most outstanding Agatha Christie covers. The cover below is ominous in numerous ways. The peephole effect on the back cover adds to the eyes, the gnarled branches, the sly chicken, the obscured face, the blade of a dagger to create melodrama.

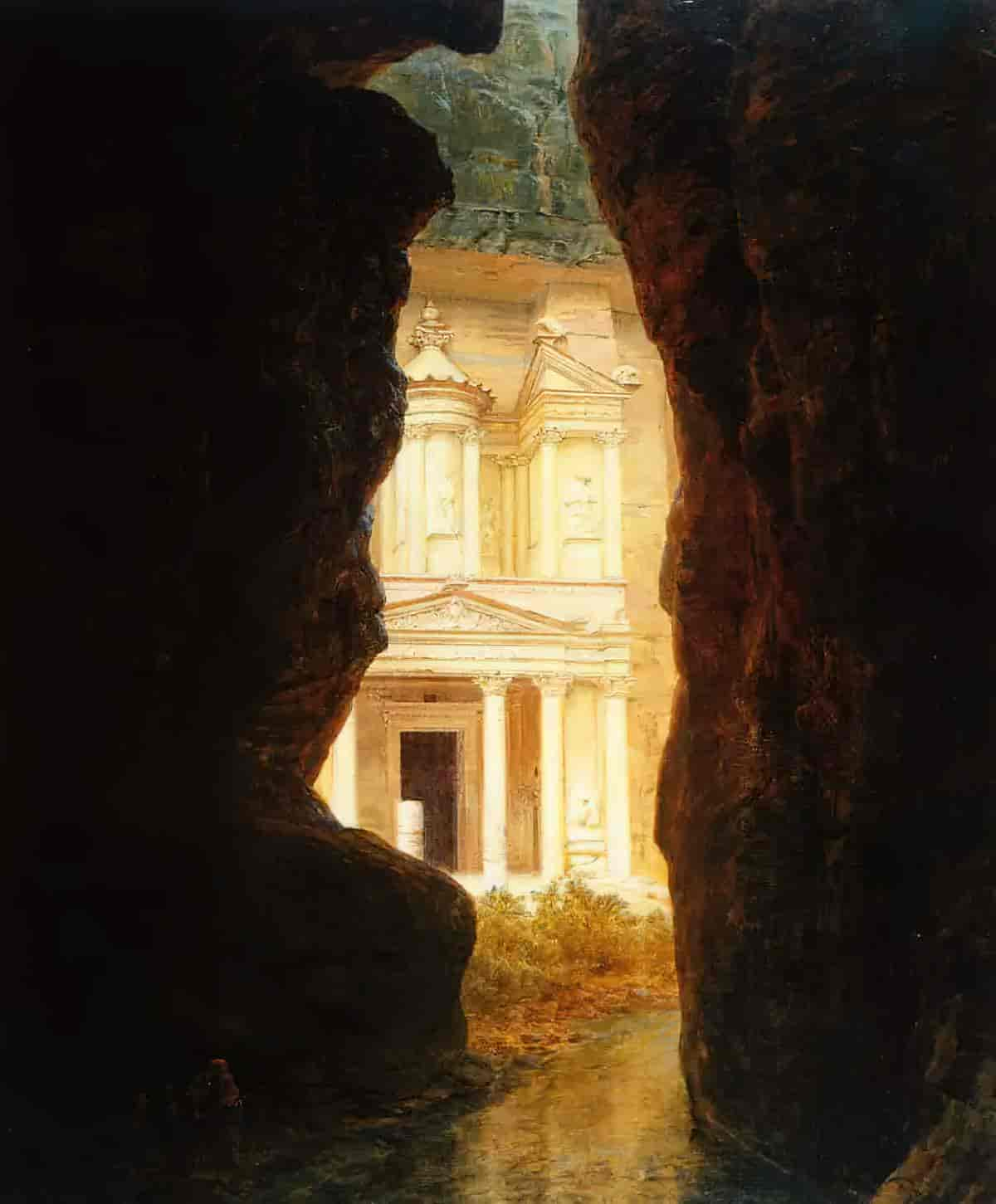

DOORS AND WINDOWS AS PEEPHOLE

Doors in houses and dorms are meant to conceal what may be behind them. They are passages from one space to another, the divide between the entertaining area in dining rooms and living rooms and privacy found in bedrooms. Tony purposefully disrupts this ordered normalcy.

In leading Natalie from one space to another, she alters Natalie’s connection to the outside world (both in how the girl must relate to her own spaces, the spaces of others, and even to herself).

“Homespun” Horror: Shirley Jackson’s Domestic Doubling by Hannah Phillips

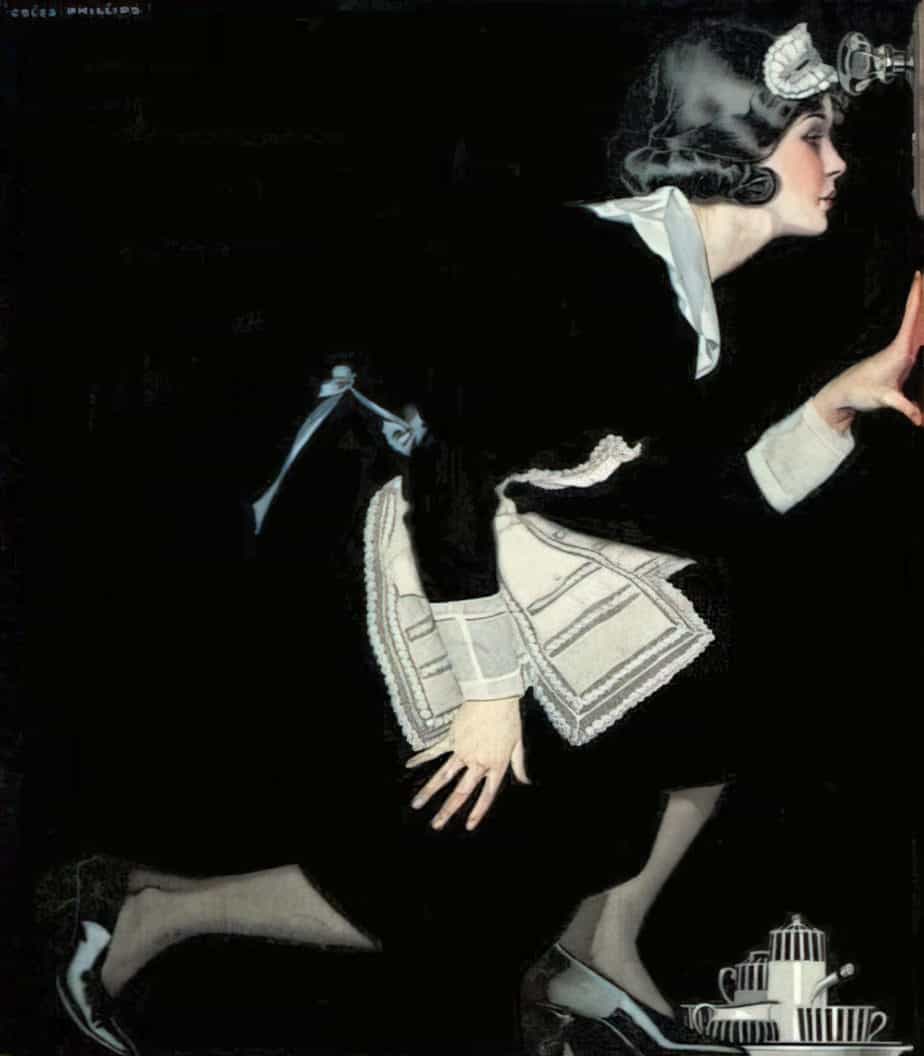

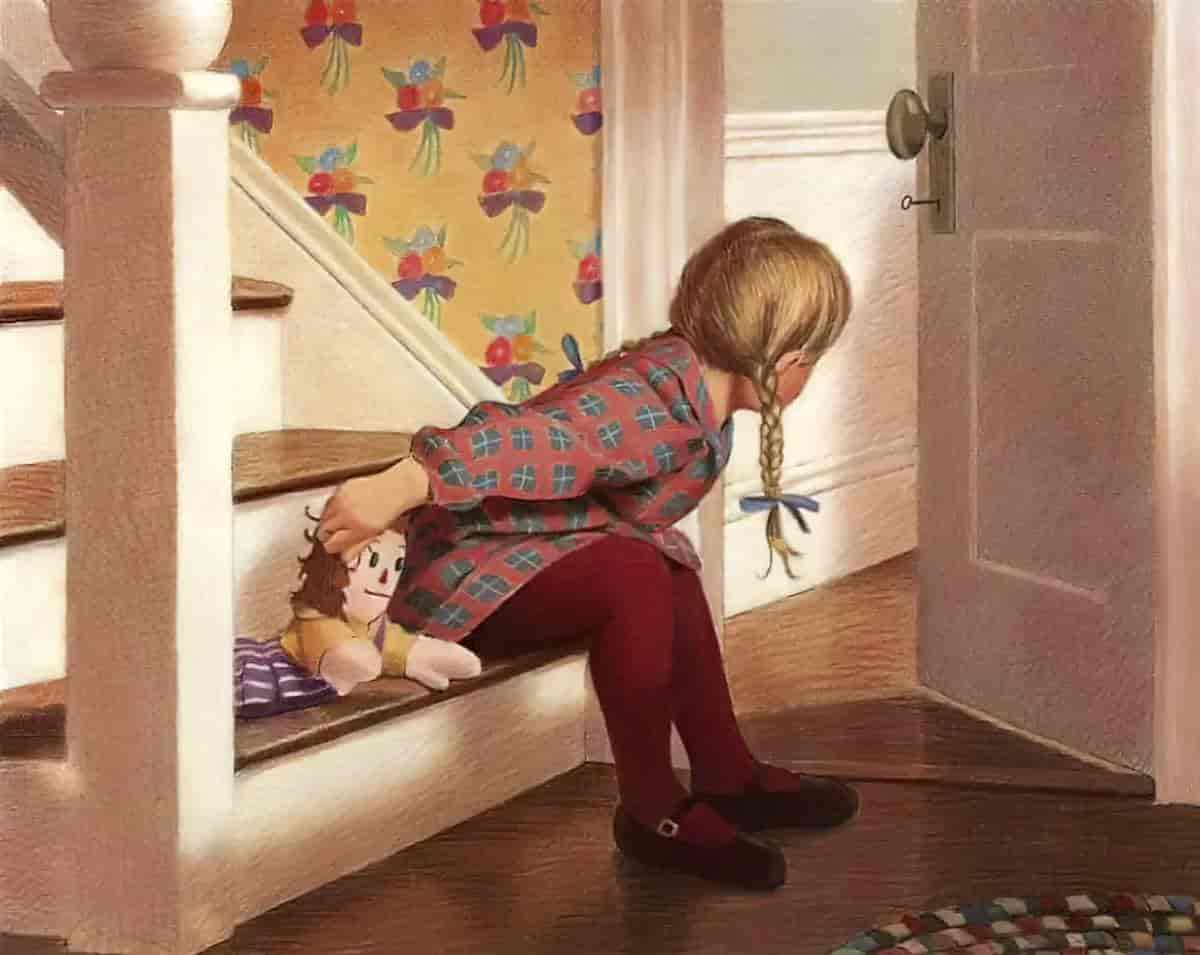

One way to add interest to a composition is to show only a part of it. The viewer wonders what’s missing, and fills in some detail themselves. Below are various compositions from various angles, from the fine art world and from picture books.

And from the other side of the window: (See also: Window Symbolism)

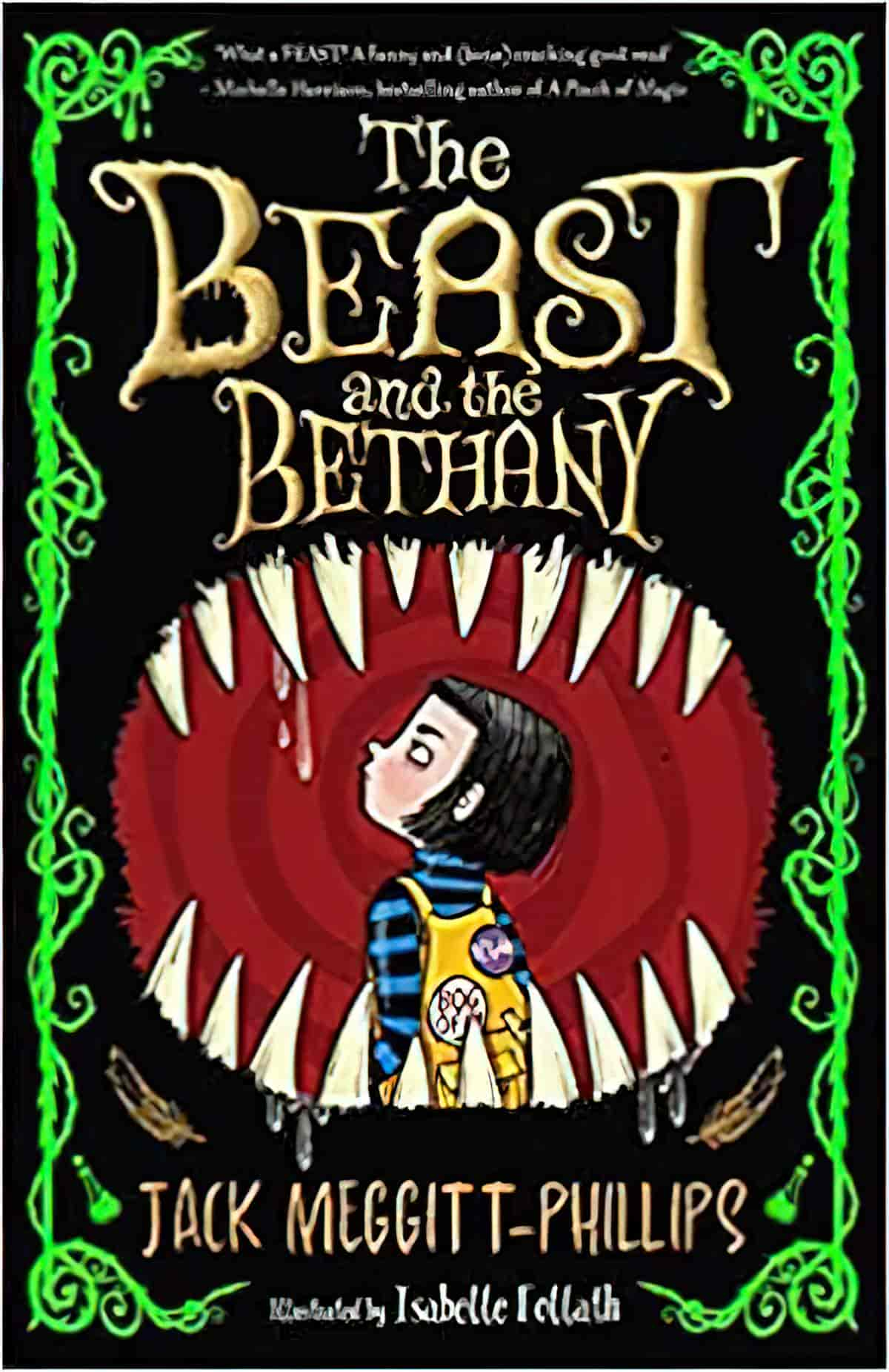

Beauty comes at a price. And no one knows that better than Ebenezer Tweezer, who has stayed beautiful for 511 years. How, you may wonder? Ebenezer simply has to feed the beast in the attic of his mansion. In return for meals of performing monkeys, statues of Winston Churchill, and the occasional cactus, Ebenezer gets potions that keep him young and beautiful, as well as other presents.

But the beast grows ever greedier with each meal, and one day he announces that he’d like to eat a nice, juicy child next. Ebenezer has never done anything quite this terrible to hold onto his wonderful life. Still, he finds the absolutely snottiest, naughtiest, and most frankly unpleasant child he can and prepares to feed her to the beast.

The child, Bethany, may just be more than Ebenezer bargained for. She’s certainly a really rather rude houseguest, but Ebenezer still finds himself wishing she didn’t have to be gobbled up after all. Could it be Bethany is less meal-worthy and more…friend-worthy?

Art can turn us into saviours and voyeurs.

No decent man ought to read Shakespeare’s sonnets because it was like listening at keyholes.

Virginia Woolf, Mrs. Dalloway

SEE ALSO

In many of the illustrations and paintings above, a clear light distinction between foreground and background is what makes it great. But sometimes you don’t want that in a photo, perhaps because the ‘peephole’ part of a photograph is too overexposed. The tutorial below is a good guide on how to fix that. (I happen to use Affinity Photo but the concepts are exactly the same for Photoshop.)

In a nutshell:

- duplicate layer

- set the top one to soft light

- play with the opacity (lower it)

- create a curves layer

- click in the middle of the curve, pull down until it looks good to you, looking only at the part that’s overexposed, ignoring what it’s doing to the rest of the photo

- layer > invert

- using a white soft brush with a lowered opacity, paint back in over top of the part you feel is overexposed

Now you’ve got a curves layer, you can also mess around with how shadows and highlights (use a black brush) look across the rest of the photo. You’re basically dodging and burning, with one big advantage doing it this way: You’ve manually adjusted the curve layer yourself, and can go back and adjust it again at any time: a ‘controlled’ dodge and burn, if you will.