Stranger Things is a Netflix series created by the brilliantly named ‘Duffer Brothers’, out this year but set in 1983. Though I suspect strong ‘recency bias’, season one scores a very high 9.2 on IMDb.

**CONTAINS ALL THE SPOILERS**

The show feels like a mixture of Twin Peaks (with the missing kids and small community), Freaks and Geeks (with the three nerdy boys playing Dungeons and Dragons and the older sister trying to find her place in the cool group), something done by Stephen King, and Minority Report (with its sensory deprivation bath and freaky magic-genius girl).

Dangerous Games: What the Moral Panic over Role-Playing Games Says about Play, Religion, and Imagined Worlds

The 1980s saw the peak of a moral panic over fantasy role-playing games such as Dungeons and Dragons. A coalition of moral entrepreneurs that included representatives from the Christian Right, the field of psychology, and law enforcement claimed that these games were not only psychologically dangerous but an occult religion masquerading as a game. Dangerous Games: What the Moral Panic over Role-Playing Games Says about Play, Religion, and Imagined Worlds (University of California Press, 2015) by Joseph Laycock, explores both the history and the sociological significance of this panic.

Fantasy role-playing games do share several functions in common with religion. However, religion—as a socially constructed world of shared meaning—can also be compared to a fantasy role-playing game. In fact, the claims of the moral entrepreneurs, in which they presented themselves as heroes battling a dark conspiracy, often resembled the very games of imagination they condemned as evil. By attacking the imagination, they preserved the taken-for-granted status of their own socially constructed reality. Interpreted in this way, the panic over fantasy-role playing games yields new insights about how humans play and how they construct and maintain meaningful worlds together.

New Books Network

The show also feels a bit like the computer games Don’t Starve and Minecraft, with its own version of the Nether (“The Upside Down”).

GENRES

Stranger Things is a blend of drama, horror and mystery.

The drama gives us a great character web; the horror gives us rich symbolism and mystery drives the plot forward.

The mystery:

- What happened to the boy (and the young woman) who went missing?

- Why is Joyce getting creatures coming through her walls and messages through the lights?

- What’s going on inside that big building on the edge of town?

- What is the nature of the mysterious creatures? What dangers do they specifically pose and to what extent are they human?

- How is that other world related to our real world?

- Who is Elle and what is weird about her?

In a lot of mysteries, the audience wonders whose version of the truth to believe. In this mystery, however, the audience knows that Joyce and the kids are right about the supernatural goings-on because from the very first scene we are let in on the setting fact that strange things are going on inside the lab.

If this were a novel, we’d also classify this series as (classic portal) fantasy.

If the story takes place in a world other than our own, it is fantasy.

If the story starts in the real world but the characters enter a new one in the story, that is called a Portal Fantasy.

The other world is called a ‘parallel world’.

Classic fantasy takes a single main character from mundane world to fantasy world and back to the mundane. So, classic fantasy is also portal fantasy.

A passageway is normally used in a story only when two subworlds are extremely different. We see this most often in the fantasy genre when the character must pass from the mundane world to the fantastic.

In good portal fantasies, the story dwells for quite a time on the portal itself. The characters will go back to it several times, and they will spend quite a bit of time in it before they infiltrate the parallel world.

Some reviewers have wondered who this series is for. Is it a family film? The horror film is a genre aimed largely at pubescent and adolescent youth, so I think that answers that question. There’s quite a bit of schlock shock in this film, but mainly from the scene transitions. There may be a few times when you scream out loud.

SETTING

TIME

This show feels impressively like a genuine throwback to the 1980s. Everything from the movie poster to the intro scene adds to that feel. It’s interesting to me that the Duffer twins were born the year after this was set. Still, I bet these guys grew up with a heavy diet of 1980s stories.

There’s a strong E.T. flavour to this film, though E.T. was genuinely filmed AND set in the early 1980s.

A huge advantage of setting stories about kids in this period is that it predates mobile phones and the Internet. Kids genuinely had a lot more freedom to roam their environs. These days if you want to write a story about kids riding around on their bikes after dark, you’d better cover yourself by also making those kids from neglectful homes. And that leads to a much different kind of story, in which the neglect is in danger of becoming The Story.

A disadvantage of living in this period was lack of Internet. Remember how Bella works out that stuff about the Cullens? She finds out all about it on the Internet. This is not a particularly exciting thing to portray on TV however, and in this setting we have the character of the geeky and pushover science and math teacher who the boys can ask anything, from parallel universes to how to make a sensory deprivation chamber. This guy is a fount of knowledge and always willing to help. As a well-meaning character, he has other plot uses too.

A lot of the scariest scenes take place at night. If they don’t take place at night, they take place inside dingy houses, abandoned caravans and sheds.

PLACE

Though we are told that this town is in the state of Indiana, and is filmed in Georgia, Hawkins is fictional. It’s a quiet ‘all-American’ town and centres on the police station, family houses, huts in the woods and in the schools.

The woods as a place of danger come straight out of the darkest fairy tales. Bad things happen in the woods, especially at night. But during the day the woods are a safe place to play.

CHARACTERISATION

Who are the main characters of this show?

This is an ensemble cast but some are archetypes and others undergo a character arc. (If ever in doubt, main characters = people who change the most over the course of the story.)

So that would include Hopper, the reluctant police sheriff. When we first see him he is living in semi-squalor. In the establishing shot we see him wake up, smoke a cigarette, brush his teeth, then wash down some pills with Schlitz. On the balcony he smokes a cigarette. This is your archetypal ‘defective detective’.

On the job, he insists to his secretary that ‘Mornings are for coffee and contemplation’, despite having a serious missing child case right under his nose. But over the course of the first season he springs into action, and his lackadaisical attitude has a positive upside: He is quite happy to work outside the law and is open to the idea that mysterious things are happening in his town. He then demonstrates great ingenuity and problem-solving and shows that, when sufficiently interested in the case, he is in fact an excellent cop.

Hopper has a ‘ghost’ — not a particularly original one: he has a dead daughter himself, explaining his descent into squalor and not-caring, but also causing him to eventually care deeply about the missing children.

Joyce (Winona Ryder) also has a ghost. We keep hearing around the town that she has mental health issues, and her general anxiety leads her into a very dark place after her younger son goes missing. But a change in circumstance does not make a character arc. Joyce was ‘crazy’ at the start and after a few weeks of understandable agony, others around her learn she’s been right all along, but Joyce herself remains basically the same person. Joyce is therefore not a main character.

CHARACTER AND GENDER

A Variation On The Rape Revenge Storyline

If you’ve watched enough TV, you’ll have predicted it as soon as you saw the three geeky boys playing that boardgame: You just know one of them is going to have a snarky, unkind older sister who is interested in the cool group.

You see it a bit in Freaks and Geeks also, though Lyndsay is presented from the get-go as a more sympathetic character. In contrast, Mike’s older sister slams her bedroom door on him even as he kindly offers her pizza. This manipulates audience sympathy in favour of the boys. It’s only later in the story that we get a more rounded picture of the sister (Nancy) when we see her let down by her unpleasant jock boyfriend and his much nastier friends. Our sympathies for Nancy are at their peak when we see her put down as a ‘sl*t’ in public, and no one comes to her defence. I am a little sick of these cheap and highly gendered methods of guiding audience sympathies for characters. Another version of this storyline is the rape storyline. While it’s true that in real life women and girls are frequently called whores and sl*ts as a form of control, when it comes to entertainment, it would be nice to not have to deal with that again and again and again. I think perhaps it takes a female writing team to understand that this storyline does not constitute pure ‘entertainment’ for a large portion of the population, as it hits too close to home. And in a story with any number of made-up things, the writers could have made something else up here, too.

That said, Nancy Wheeler does have a character arc. She learns that chasing the jock is not going to lead to happiness. After spending her life sheltered by parents who live at the end of a cul-de-sac, she realises that she does have what it takes (most of the time) to rise to the challenge of a life-and-death crisis.

Feisty Girls With Powers

There are a lot of faux-feminist stories out there in which the girl characters — often described as ‘feisty’ — are the ones with the abilities while the boys around them are sometimes shown up for their shortcomings.

Here we have Nancy, picking up a gun for the first time, but out-shooting Jonathan, who has been shooting between cans for years.

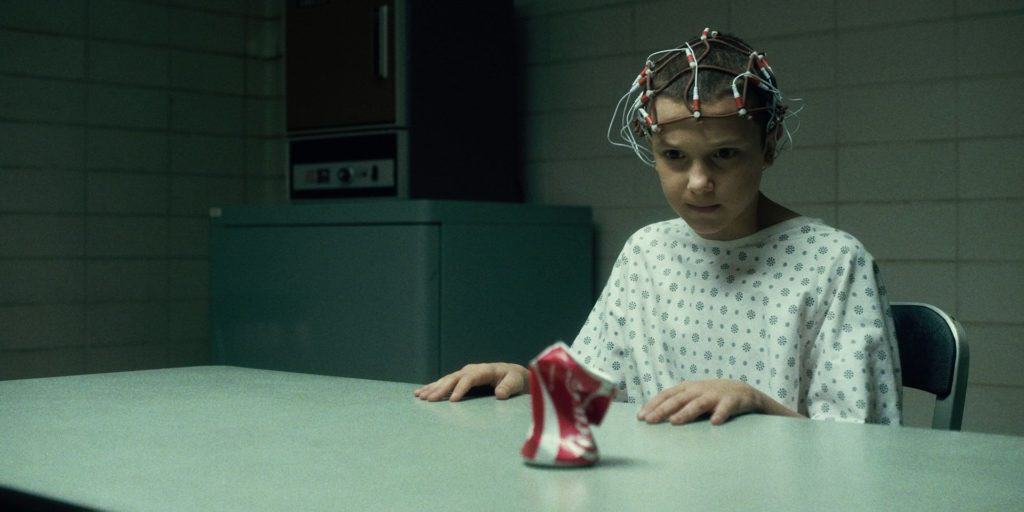

Then we have the character of Eleven, of course, who is an even better example of a feisty girl with powers. The fact is, superhuman strength is even more amazing when it comes from a girl, precisely because that’s not what we have been trained to expect. The younger the girl, the stronger this effect. As chauvinist Ted Rumsen says of Peggy in Mad Men when she comes up with the creative line that leads to her first break promotion: “It was like watching a dog play the piano.” The same applies when little girls defeat men in stories.

But let’s not mistake this for ’empowerment’. Don’t forget that these girl characters exist mainly for the character development of the boys who surround them. In the case of Nancy, the jock who slept with her then lead to her public shaming has an epiphany in episode seven and comes to realise that Nancy is a much better person than his other friends. In the case of Eleven, she is the cause of Mike’s sexual awakening and also the cause of Lucas Sinclair’s realisation that it’s not always so easy to tell good from evil without digging a little deeper. When female characters appear mainly to serve the character arcs of boys around them, I call this the Female Maturity Formula. It’s absolutely everywhere.

In the final episode we see our heroes attack the monsters. Here we have the classic trope of Guys Fight, Girls Shoot. This reminds me of the pro-gun sentiment that comes out of America after any big shooting: The idea that civvie ownership of guns is a good thing because it ‘levels the playing field’. A girl with a gun can overpower a big guy, for instance. I have heard this argument coming out of very smart people, who completely forget how many more women (to say nothing of men) are shot by their intimate partners each week.

Don’t Go In There!

One of the most genuinely scary moments in this series happens in the dying deer scene. Soon after, Nancy is wondering what happened to that deer, and she hovers at the edge of a most unappealing open tree trunk, obviously dripping with blood and full of cobwebs on the inside. Anyone sitting in the audience is thinking, “Jesus, don’t go in there!” But what does Nancy do? She goes in there. Despite being too grossed out to shoot a deer herself and put it out of its misery (instead relinquishing the gun to the older boy, despite her already having proved herself as the sharp-shooter of the two), we are to now believe that she would be brave/foolish enough to enter a tree which presumably contains a dead deer and some other horrible supernatural goings-on.

This is a common trick in horror. And it’s almost always a naive (read: stupid) female character who goes into danger despite everyone, including the audience and other male characters, knowing that she’s going to get herself into strife. Why wasn’t it Jonathan Byers who went into that tree trunk? Because that defies the gender rules of the horror genre. Only a silly girl would go in there. Also, Jonathan is given the opportunity to prove his manliness by pulling her out when she sticks her hand out for help. She ends up lying on top of him, pressing her full body against his, hugging him in terror.

Would it work the other way around?

Female Friendships?

This series barely passes the Bechdel test. There is the friendship between Nancy and Barbara of course, but the writers soon get rid of Barbara.

A serious shortcoming of this storyline is that the disappearances of the children have an unrealistically low-key effect on this small Indiana town. Something more could have been done to show the audience that the disappearance of Will Byars is occupying the town’s consciousness (as I expect it would), but the disappearance of Barbara is dealt with as if no one, except Nancy, really cares she’s gone. I rather cynically think that people are much more interested in missing children if those children are classically pretty, and it’s no coincidence that almost every murdered girl on a crime show is beautiful to look at. Not so Barbara. In fact, her uncoolness and her boring sensibleness are very things that lead to her downfall. (If she’d just stayed inside with Nancy she wouldn’t have been taken at the pool). It’s not just the town who seems uninterested in Barbara’s disappearance; the audience is likewise encouraged to focus elsewhere.

The ending of this season felt icky to me. The boys are elated to have their friend back. Even Nancy has moved on, and her main focus is on replacing Jonathan’s smashed camera. Hopper has come to terms with the death of his daughter. But Barbara is collateral damage. No one misses Barbara. Though found dead inside The Upside Down world, at no stage is there any scene in which her family — or anyone else — mourns her absence.

Then there’s Wynona Ryder’s character: The archetypal crazy-with-grief mother, who turns out to be right, due to the widely acknowledged invisible bond that ties a mother to her children. This trope is called Cassandra Truth, and the reason it works so well in stories when applied to women and children is that both women and children are widely perceived to be liars — children because their understanding of the world is limited by dint of their age, and women because, well, women are liars. And overly emotional. To the writers’ credit, I suppose, the women at least accompany the men on their mission to save the day. But Wynona is given little to do but scream. And be instructed by Hopper on CPR. (Another male-instructs-female dynamic.)

It’s rare for male writers to attempt a female friendship, and the Duffer brothers have avoided it here, too. It would seem Joyce Byers has no female friends to call upon in her time of need. Instead the deadbeat Dad turns up to give her lectures, alternately comforting and upsetting her. Via this dynamic we get to see a little more about the history of this family. But it’s telling that in this made-up story, the writers felt safer getting rid of Joyce’s sources of real support (via the argument with Karen Wheeler) rather than attempt something that might result in an uncomfortably feminine dynamic.

Then again, doesn’t Jane (known for most of the series simply as ‘Eleven’) undergo her own character arc? Yes, perhaps we can say she does.

The indefatigable 12-year-old protagonists on their bikes are straight out of Spielberg – especially when they find Eleven, an almost-mute girl with large eyes and strange powers who they have to hide in the basement and who gradually learns by their example what friendship and loyalty mean.

Note that the reviewer above has pointed out that the female character has to ‘learn’ friendship from the boys.

I’ll clarify here that when I have a problem with female friendship as most-often written in popular stories, we very rarely see realistic (if any) female-to-female friendship.

When it comes to Jane’s character arc, the boys are presented as models, as if male-to-male friendship is the most pure kind. This has to be our conclusion when there is no positive example of female-to-female friendship.

Then of course we have boys as mentors, girls as infantalised learners. Boys learn from their circumstances whereas girls learn from boys. (We have the most classic case of this in the film ParaNorman, in which Norman gives the young — but actually much older — witch a life lecture in the forest.)

Female Infantalisation

Some reviewers have said that Winona Ryder is upstaged by the kids when it comes to acting. But I’d like viewers to consider the dialogue as scripted, and the difference between what the boys are given (great one-liners and definite character arcs) versus what Wynona Ryder is given (crazy Cassandra mama bear).

Despite her considerable screen time, Ryder is given very little to play with. For the first four hours, she runs a narrow gamut of emotions from anxiously perturbed to anxiously distressed. “My son is missing!” she announces in the first episode, trying to provoke a response from the lazy, beer-for-breakfast police chief (a wonderfully dishevelled David Harbour). Two hours later: “My son is missing!” And that’s it. It’s not until Joyce discovers a supernatural way to contact said missing son – risking her sanity in the process – that Ryder is allowed to explore a broader dramatic pallet.

The Telegraph

Don’t forget that Joyce isn’t the only unstable woman in the town. When the writers rely on the mental instability of yet another distressed mother — Eleven’s mother — an unfortunate pattern starts to emerge. Hopper’s grief for his child is the impetus for hyper-masculinity — bravery and an increasingly thick beard, in fact. But with the grieving mothers you get… crazy. I mean, stuck in the house talking to the lightbulbs crazy. Mute and sitting-in-a-rocker-all-day kinda crazy. It makes little difference that these women are ‘right’. Hopper is also ‘right‘. He gets to leave the house and be a hero.

But will an audience really accept anything else?

A somewhat reluctant word on the actress who plays Nancy.

This young woman is now looking so fragile and waiflike that I’m worried for her health.

Even if this is Dyer’s natural phenotype, the choice to cast a super-thin actress, when the young male actors look 1980s slim but nevertheless sturdy, says disturbing things about our culture.

Especially when the actress who plays Barb is dressed up to look dowdy. Shannon Purser, in contrast, looks to be in the healthy weight range for her age and gender. (The actress is a very similar build to me, which is how I know!)

Opponents

This series has a wonderful range of opponents, beginning with the inhuman, moving into the semi-human, and then into the rounded humans who can stand in the way of progress despite themselves.

The problem with monsters as villains is that they’re not all that interesting. Sure, they’re scary, and those long-armed, Venus-fly-trap-faced things are some of the scariest creatures I’ve seen on TV. But they’re not interesting. The best opponents are human.

To occupy that position of human evil we have ‘Papa’ (Dr Brenner) from the lab, who has kept Jane captive since her conception. This guy is surrounded by some nameless sidekicks and is a great villain because he is single-minded in his mission to get the best out of this child for his own personal gain.

An interesting evil sidekick is the middle-aged woman, Agent Connie Frazier, who looks as harmless and professional as you could imagine. In a quest to recapture Eleven, this woman poses as a social worker, a science fair organiser, a police officer and whoever else the situation requires.

As for the ordinary characters, the detailed character web means that even characters who care about each other can at times be opponents.

- The Wheeler parents are the opponents when the boys hide Eleven in Mike’s house.

- And when Nancy brings boys back to her bedroom, and the mother never knocks.

- Lonnie Byers is Joyce’s main emotional opponent, though the whole town is against her.

- The three boys disagree about the girl, and whether or not she is The Monster. They also disagree about whether it’s possible to have a threesome when it comes to ‘best friends’.

- Nancy has frenemies who lead her astray then fail to stick with her.

- Nancy and Jonathan have a complicated friendship, which is also the beginning of a romance. (You can tell because they have a big argument, which is a sure-fire way to know they’re meant for each other.)

- and so on

SYMBOLISM

Horror is about humans in decline, reduced to animals or machines by an attack of the inhuman. While traditional horror is religious in nature, these days most horror stories make use of medical or psychological ideologies.

Since this is a horror story, obviously ‘light’ and ‘dark’ are symbolic.

Most annoyingly this comes to fruition in the final episode, with all of that flickering at the climactic big struggle scene — to the point where I seriously thought we could’ve used a warning for photosensitive epilepsy.

But even before that, we have the lights in Joyce’s house, flickering on and off. We have the ‘light’ world of the town in contrast with the dark underworld below.

This opposition between light and dark are from Christianity, and symbolise good and evil. We all know that intuitively. Also from Christianity we’ve got the snake, which rather disgustingly comes out of the missing boy’s mouth.

FURTHER READING

Ode to Gen X: Institutional Cynicism in “Stranger Things” and 1980s Film

In Ode to Gen X: Institutional Cynicism in “Stranger Things” and 1980s Film (University Press of Mississippi, 2021), Melissa Vosen Callens explores the parallels between iconic films featuring children and teenagers and the first three seasons of Stranger Things, a series about a group of young friends set in 1980s Indiana. The text moves beyond the (at times) non-sequitur 1980s Easter eggs to a common underlying narrative: Generation X’s growing distrust in American institutions.

Despite Gen X’s cynicism toward both informal and formal institutions, viewers also see a more positive characteristic of Gen X in these films and series: Gen X’s fierce independence and ability to rebuild and redefine the family unit despite continued economic hardships. Vosen Callens demonstrates how Stranger Things draws on popular 1980s popular culture to pay tribute to Gen X’s evolving outlook on three key and interwoven American institutions: family, economy, and government.

at New Books Network