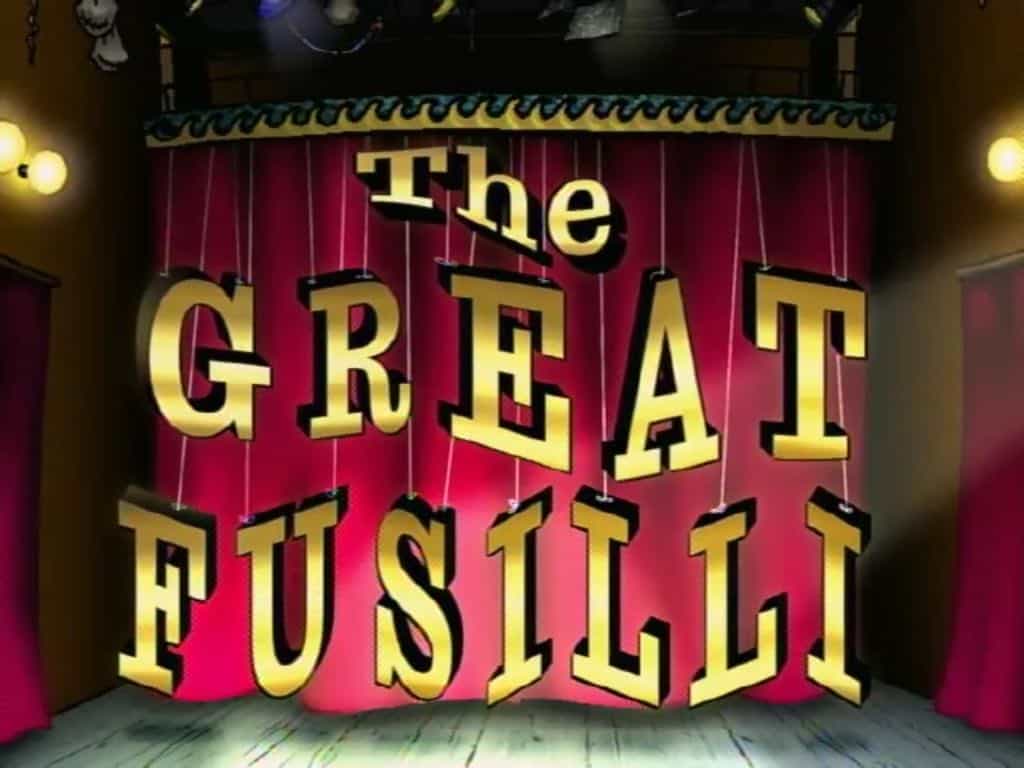

STORY STRUCTURE OF THE GREAT FUSILLI

The Great Fusilli is the last Courage story of season one and it is fitting that the creators have made a work of metafiction — in other words, the audience is reminded that they are watching a TV show.

WEAKNESS/NEED

Courage: That it’s up to him to save the day despite being an ordinary dog

Muriel: That she is oblivious and trusting and just a little prone to fancy

Eustace: That he is easily persuaded by the promise of riches (among many other faults, this one is often his downfall, as it is here.)

DESIRE

Eustace wants to save Muriel and Eustace from the suspicious magician who has come to the house to make his owners stars.

OPPONENT

We see the opponent in the very first scene, driving down a long road to Nowhere. There is a long history of travelling circuses (and gypsies) and because they come to town for a short time then leave, we are to be suspicious of them.

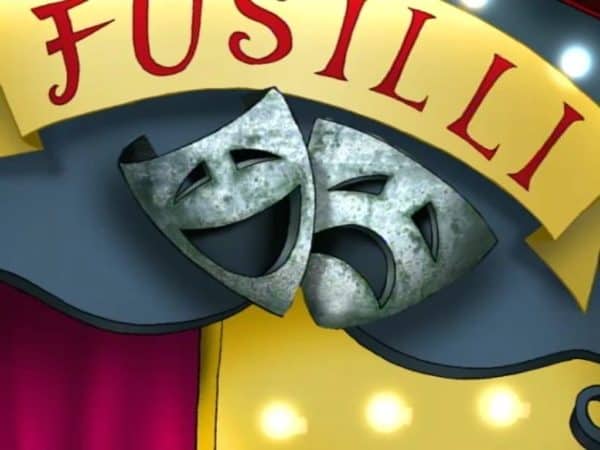

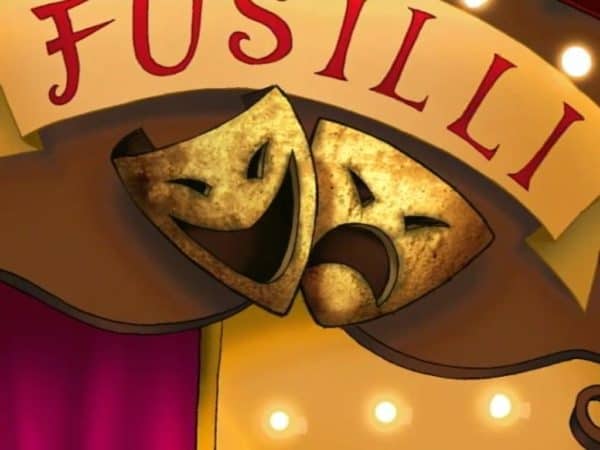

He parks right outside the Bagges’ house and tries to persuade Courage that he belongs on the stage. Courage is immediately suspicious when the masks of the Fusilli logo switch suddenly from happy to sad.

The Great Fusilli is not what he seems and this is conveyed in various ways.

- The canned laughter not only pokes fun at other cartoons which rely on it, but show that this character is quite happy to live in non-reality, where an imaginary audience is as good as a real one.

- The logos are masks. Masks are used equally in horror and comedy, which is why it’s no surprise to find them used so frequently in a horror comedy. A mask isn’t necessarily a literal mask — we saw Courage dress up as a bunny rabbit in an earlier episode in order to lure a predatory opponent and this was another example of a ‘mask’. (Another oft-talked about mask is when Dustin Hoffman dresses up as a woman in the film Tootsie.)

- He is a crocodile. With the concept of ‘crocodile tears’ we have been primed to think of crocodiles as tricksters.

It is eventually revealed that The Great Fusilli is a carnivalesque character whose ambition is to have fun. This should come as no real surprise, since he is named after a type of pasta. (The second part of his name sounds like ‘Silly’ in English, which helps.)

PLAN

“What do I do now?” we often hear Courage say at the moment where he must come up with his plan.

Courage’s plan is always first to talk and reason. Since he is a dog this never works.

He goes along with The Great Fusilli, giving the audience an opportunity to see Courage tap dance and so on. We’ve seen other characters do this, for example Chihiro in Spirited Away. Going along with the opponent’s wishes is a type of plan, though perhaps not much used in the West because writers are mostly under the influence of Joseph Campbell and the Hero’s Journey. Going along with an opponent’s plan is never part of that deal.

We don’t know what The Great Fusilli’s plan is until near the end. We only know that he’s up to no good.

We get a clue when we see the other puppets (from Courage’s point of view) and then the three empty but labeled hooks, much like graves waiting to be filled in.

BIG STRUGGLE

The Great Fusilli — via magical ribbons dropping out of the mouths of the masks — turns Eustace and Muriel into puppets on strings. He has great fun playing with him. This was his plan.

This is where the metafictional part comes in — he has set up the stage to resemble the Bagges’ living room. The characters say exactly what they would normally say, only they’re being pulled by strings.

Courage covers himself in powder first, and inadvertently scares The Great Fusilli, who naturally assumes Courage is a phantom. This was not Courage’s plan (we are told from his face).

There’s obviously some Phantom of the Opera influence coming through here. The original novel was partly inspired by historical events at the Paris Opera during the nineteenth century and an apocryphal tale concerning the use of a former ballet pupil’s skeleton in Carl Maria von Weber’s 1841 production of Der Freischütz. So there’s a long tradition of European phantomy things in operas.

SELF-REVELATION

The Great Fusilli jumps to his death over the balcony, although he’s not really dead. Death is not the worst thing that could happen to this opponent who craves fame. The worst thing for him is to be left all alone in the middle of Nowhere, performing to an imaginary audience. So that’s what the writers have happen.

See also: Picturebook Study: In which Baddies Get Their Comeuppance.

In short, if you want to dish out just desserts for an opponent in a children’s story, and also want to avoid death, the way to manage it is to work out their greatest shortcoming, ham it up, then do that to them. It can be as silly as you like. So if you had a character obsessed with cheese you could trap them in a glass room surrounded by cheese on the moon, for instance.

Since this is a metafictional story the audience has it ‘revealed’ (in a fashion) that this entire thing has been made by people behind the scenes. This feels like an homage to them.

NEW SITUATION

The metafictional part doesn’t end. So the series comes to an end with Courage pulling the strings of Eustace and Muriel as they sit in their rocking chairs, safe in their own living room.

“The things I do for love!” Courage announces to the camera — one of his catch phrases.

If this series had not been renewed for another three seasons it would have made a fitting end. Fortunately there are plenty more Courage stories to come.

Since this episode feels like an homage to the creators of Courage I’ll take the opportunity to screenshot just one of the end credits, as a reminder to all of us writing for children just how much effort goes into a great children’s story. The head writer is David Steven Cohen. Cohen has more recently been working on Arthur, Little People and Space Racers.

Also take a look at the number of storyboarders involved in Courage The Cowardly Dog: