It is much more effective to act like a nice guy and be “reasonable” if you prove willing to go beyond just verbiage. You can afford to be compassionate, lax, and courteous if, once in a while, when it is least expected of you, but completely justified, you sue someone, or savage an enemy, just to show that you can walk the walk.

Nassim Nicholas Taleb, Black Swan

Vince Gilligan, creator of Breaking Bad, said in defence of Skyler that if his audience sides with Walt, that’s on them. Not so fast. We live in a misogynistic framework and that will affect judgement of fictional characters in turn. I was recently sharing a doctor’s waiting room with a middle-aged white man who said with venom that Walt should have killed her. I immediately felt slightly terrified and shut the conversation down.

But with Breaking Bad, hatred for Skyler White is also in the writing.

When a character in fiction is required to do something very bad — something which any reasonable person would find morally reprehensible — and if the audience is required to empathise with that character (due to spending an entire series with them, say), then it’s necessary in the set-up for the audience to understand the reasons for the character’s actions. The audience must empathise, or else everything feels pointless.

Walter White is one such (anti)hero. An ordinary guy starts cooking up meth for money. Yet we side with him. Make no mistake: we are tricked into siding with him. Audiences who hate Skyler fell for that, hook line and sinker.

Writers use tricks. These tricks are tried and tested. Here are the tricks used in The Sopranos, to get us onside with Tony. (Spoiler alert: They made us despise the women closest to him.)

If I were a cannibalistic psychopath, I’d want to be just like Lecter.

Robert McKee, Story

Likewise, if I were a science-teacher turned meth dealer, I’d want to be just like Walter, I guess.

So, what are the tricks?

APPEARANCE AND NAME

For starters, Walter White looks like the actual human incarnation of Ned Flanders. i.e. Mr Harmless-And-Well-Meaning. (Walt has none of the annoying personality traits of Ned Flanders, which would turn him into an unsympathetic caricature.) Even Mr White’s name is allegorical: bland and ordinary and reasonably common. Even the W-alliteration of ‘Walt White’ is ever so slightly comical and emasculating. (A lot of children’s book characters have alliterative names.)

DISABILITY AS PITIABLE STATE

The Whites have a disabled son, which I believe is meant to make us empathise more with Walt than with Flynn himself. Walt Junior is a smart-mouthed teenager (middle-aged audiences will empathise) and a new baby on the way. In other words, Walt has more than himself to worry about. It’s easier to identify with unselfish characters than with selfish ones.

CONTRAST CHARACTER

Walter’s brother-in-law is a good contrast because, unlike Walt, who would be happy with the simple things in life, the brother-in-law is a police officer who craves action and excitement. He is not compassionate. He takes Walter along to a drug raid to ‘get some excitement in his life’ but unlike Walter, who sits in the back seat with an emasculating white bullet-proof vest over top of his jersey and a worried look on his face, the brother-in-law is hopped up on adrenaline at the thought of catching crooks. The brother-in-law and his police partner even make bets on the nationality of the criminals. For them, drug busts are a game. They don’t seem to look any further than that. It is only revealed as the series goes on that Hank takes his job very seriously. Ultimately, his job is more important than his life. (Refer to Hank’s last words.) In contrast, Walt thinks things through intelligently, and the audience is guided through his thought processes.

TRAPPED AND BABIED WITHIN MARRIAGE

On the morning of Walt’s fiftieth birthday, his wife dishes up vegetarian bacon. Walt’s fiftieth is not cause for celebration so much as reason to watch his health. Walt doesn’t complain about the bacon. He understands that he is being looked after. Skyler’s care is coded by the audience not as loving care, but as infantilization.

Walt Junior, in contrast, is vocal about it, complaining that it ‘smells like band-aids’. He then makes a wisecrack about his father’s age. The audience empathises with Walt because all of us worry about getting older (if we’re lucky enough to ever get old) and all of us feel we should be looking after our cholesterol (or something — there’s always something).

THE OPPRESSIVE SETTING

The setting itself is important to audience sympathy of Walt.

Walt is a high school chemistry teacher, demeaning in Albuquerque because of the poor pay — and although he knows his subject matter very well, he is jaded after many years of uninterested, disrespectful students. The shot of the bunsen burner flame licking Walt’s face as Walt drones on to the class is symbolic of his later demise. The audience watches this scene rather than listening to what Walt says about the importance of chemistry; the fact is, Walt is not an engaging teacher. Yet he makes an effort to be. His passions are simply not shared by his students. He has somehow ended up in the wrong profession. Yet Walt does care about his students. This redeems him. In fiction, teacher characters can be in the wrong job and yet retain empathy with their audience, but they must basically care. (Mr Holland’s Opus springs to mind.) Many empathetic characters are in the wrong job. (Peter Gibbons from Office Space, Elaine from Seinfeld — constantly — and many people in real life who wonder what it would be like to have chosen a different job.)

See also: Teachers in the U.S. Seem to Be Getting a Raw Deal Compared to Teachers in the Rest of the Developed World from Jezebel

Poor teacher remuneration, and a wife who earns piddling amounts trading items on eBay, mean that Walt must wash cars to supplement the family income. He suffers humiliation after two of his disrespectful senior students witness him polishing the tyres of another student’s expensive car. When the girl takes a picture of him on her phone (and it’s significant that she, too, is a girl), we suspect she’ll send it round the entire school, or upload it to the internet. We know Walt’s humiliation won’t stop there. (Not like the good old days.) Humiliation elicits strong reactions in both the sufferer and onlookers, so even when a fictional character suffers a humiliation, the audience cringes in empathy.

Then there’s the American health system. I’ve only ever lived in countries with socialised medicine myself and I hugely enjoyed Breaking Bad from the get go, but overall, Tim Worstall wrote in Forbes Magazine that audiences from countries like mine had less sympathy for Walt. We need to understand something of America’s oppressive healthcare system before we fully understand his decisions.

But Walt does not feel sorry for himself even when the American healthcare system is that bad. He collapses at work and taken away by ambulance, but still wants the medic to let him out on the corner. He doesn’t have good health insurance. I’m sure. For those without good insurance, the prospect of getting an ambulance bill is almost as scary as the illness itself.

UNASSUMING EXPECTATIONS

Walt’s ordinary life and ordinary expectations are apparent when his idea of a pleasant birthday weekend is to take a drive to see an exhibition of photos from Mars. We also understand from this scene that Walt has a genuine interest in science. We suspect (and later find out) that he is very good at his (science) work. The audience can easily respect someone who is intelligent.

“HEN-PECKING”

Skyler is inclined to puts the screws on. I suspect many married men would empathise. Skyler White displays many unreasonable expectations — common to wives in fiction — that enable audience empathy with the husband.

For example, Skyler chides Walt for being late home, even though he wasn’t expecting the surprise party. (How many times have you seen a fictional wife scrape a perfectly good – microwaveable – meal scraped into a rubbish bin?)

Unlike Skyler, the audience was there with Walt when the boss wheedled him into staying on at work after five. Next, Skyler gently but surely puts the screws on about painting the baby’s bedroom. (Room-painting seems to be a common source of antenatal angst in fiction — I’m thinking Juno now.) She’d do it herself except he ‘doesn’t want her standing on ladders’. This low level guilt-trip takes place in bed, and then she wonders why he’s not aroused. Skyler makes a thing of this. Another common trope: Lack of sexual arousal* is linked with general hopelessness, marital difficulties and loss of masculine purpose in life. (This situation is reversed in the final scene of the pilot episode to symbolise a reincarnation of sorts.)

*Is this trope used far more frequently with male characters than with female characters? Even in modern stories, lack of sexual motivation is not commonly utilised as a symbol for hopelessness and malaise in women.

Then the kicker: Walt White is diagnosed with lung cancer, even though he’s never smoked in his life. We all know people who smoke like chimneys and live til a ripe old age. But Walt has just two years to live. This now seems the ultimate unfairness, and marks the turning point. Whatever Walt is about to do, the audience can now accept. We’re with Walt all the way as the straight guy ‘breaks bad’.

Will he tell his wife?

So many storylines would be stymied, if people only talked to their spouses. But no. The audience knows that Walt can’t tell his pregnant wife. In fiction as in real life, there is never a good time to break bad news. When Walt gets home, Skyler is on the phone with a credit company. They are in financial difficulty, as usual:

Skyler to Walt: Did you use the mastercard last month? Ah, fifteen eighty-eight at Staples?

Walt: Um, oh we needed printer paper. (It’s not like Walt is careless and extravagant with his money – this is a guy doing his genuine best, yet still, ends don’t meet.)

Skyler: Well the mastercard’s the one we don’t use. (Slightly patronising tone.) So, how was your day?

Walt: Oh. Fine. (The words themselves don’t do justice to this perfectly judged bit of acting from Bryan Cranston.)

Although Skyler’s eBay habit and her constant wheedling expose weak character flaws, it is also important that the audience empathises with her. And I do. How was this bit of storytelling engineering achieved?

Enter the sister.

Evil sisters are oft-used in fiction to highlight the good points in another woman. Skyler’s sister, Marie, is unpleasant in a low-grade but constant way. She seems to be in competition with Skyler. Marie does not take pleasure in any of Skyler’s happiness (the baby) or success (the writing hobby). When Skyler says she’s writing a collection of short stories, Marie asks why she isn’t writing a novel. (Short story collections ‘don’t sell’ – another unwelcome reminder that the Whites are short on money.) Yet Skyler accepts her sister’s bitchiness, refusing to take the bait. This trait in a character almost always engenders empathy. Thus, as Walt highlights Skyler’s less attractive traits, the sister highlights her best points. Now we have a deftly portrayed, rounded female character in Skyler. We want the best for her.

And Walt’s multi-layered reasons for breaking bad have now been set up. So he gets on with the job of cooking up some meth. But even when Walt engages in something morally reprehensible, he demonstrates good basic principles when negotiating with his partner in crime, ex-student Jesse Pinkman:

“You and I will not make garbage. We will produce a chemically pure and stable product that performs as advertised.”

Endearingly, and ironically — given the actual danger — Walt will also set up an emergency eye-wash station, and wants them each to wear protective coats. He knows nothing about the criminal world, and thinks they just can rent one of those self-storage sheds. (The police are onto that, apparently, so they buy a Winnebago.) So Walter is a hapless criminal, which endears him to a largely non-criminal audience. How many of us would know where to start, if we suddenly decided to take to the underworld?

Walt’s incompetence is demonstrated later in the episode as we watch him trying to douse a rapidly spreading grass fire with a single lab apron, and later again when he can’t even manage to shoot himself with the gun. (I’m reminded of Llewelyn Moss of No Country For Old Men. Moss is another small time crook who engenders empathy by getting in trouble with criminals far harder than himself.)

Comic Relief

When an ordinary guy turns bad, it is appropriate that heavy/dangerous/violent scenes are interspersed with lighter ones. In Breaking Bad the musical score lightens up and the audience is encouraged to take some scenes less seriously than others. This is a little heavy handed for my taste.

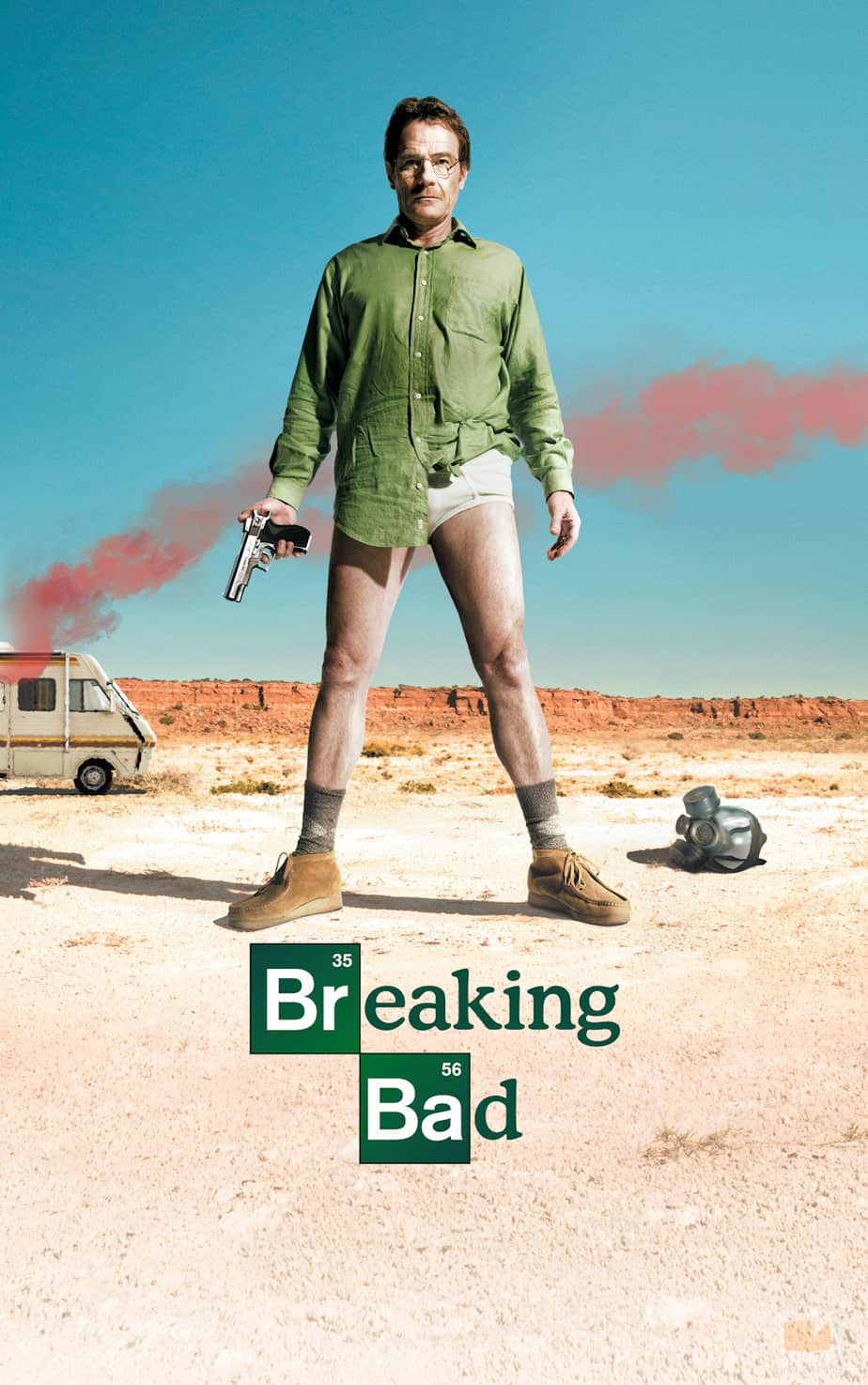

The ultimate in relief comes at the end of the pilot episode, just as we realise (along with Walt) that it’s not the cops who are after him – it’s simply a cavalcade of fire engines, and they’re screaming right past him as he stands on the side of the road in nothing but underpants and shirt. The engines are off to put out that fire he made.

This comical scene happens right after a scene of heightened tension, when Walt tries to kill himself (and fails). When we realise there is no imminent danger, we are almost as relieved as Walter himself.

Yet when we first met Walter, we saw a crazy man in a gas mask driving a Winnebago with dead bodies in the back. He could have been a psychopathic mass murderer, and all those movies about psychopathic mass murderers have primed us to think he might be. But the pilot episode of Breaking Bad makes use of the bookends structural technique, and now we’re back to the opening scene. This time, though, we’re on the side of the drug cook.

For me, the writers/actors/directors of Breaking Bad achieved character empathy in Walter White. And what a stunning example it is too. I never thought I’d be rooting for a meth cook.

FURTHER READING

STORYTELLING LINKS

- Matt Bird’s Ultimate Pilot Checklist for Breaking Bad

- Breaking Bad and the Influence of Fairytale

- Walter White Character Study

ALSO INTERESTING

ON EMPATHY

- The Neurochemistry Of Empathy, Brain Pickings

- The Walking Dead, mirror neurons, and empathy from GamaSutra

- I Hate Walter White from Salon

- Breaking Bad Season 5 from Slate

- 20 Breaking Bad Locations In Real Life from Twisted Sifter

- The Real Walter White (is a woman) from Salon

- The Real Walter White (from Alabama)

- So, You’re Looking To Break Into The Meth Business: A Guide from Thought Catalog

- Do you find Skyler annoying? I think she’s remarkably calm and reasonable given the circumstances, but I know people who can’t stand her… all the while rooting for the meth cooks. Why is that?

- A cat dressed as Walt White from BF. It really does look like him

- Breaking Bad Plush Toys, because you know, this show just screams ‘Plushie’, from Laughing Squid

- Also at Laughing Squid, a video which depicts Breaking Bad so far as an 80s style computer game

- And a recap on the first 5 seasons in time for the second half of the fifth and final

- Your complete creative guide to Breaking Bad from Co.Create

- An article on Breaking Bad and American Ambition from The Nervous Breakdown

- Like on Mad Men, the colours of the characters’ clothing are symbolic. Here’s an infographic from Slate.

- And here’s one I really don’t want to read because I know she’s right. It’s about the lack of believable female characters in Breaking Bad.

- Skyler White Is The Best Character On Breaking Bad, from Slate

- The jury is still out on whether this is science fiction or not from io9

- Breaking Bad Happened In Real Life. It also happened in New Zealand, when I was teaching at a nearby high school. (He was actually making ecstasy, but same kinda thing.)

- 10 Years On — reflections from the actors and creators

The Revolution Was Televised: How The Sopranos, Mad Men, Breaking Bad, Lost and Other Groundbreaking Dramas Changed TV Forever

What do Tony Soprano and Archie Bunker have in common? Alan Sepinwall, longtime TV writer and critic, knows that the 1970s comedic bigot and 2000s Jersey mob boss are not as different as we may think. Both broke new ground in TV and made viewers sit up and take notice, although in very different ways.

In his newly revised book, The Revolution Was Televised: How The Sopranos, Mad Men, Breaking Bad, Lost and Other Groundbreaking Dramas Changed TV Forever (Touchstone, revised edition December, 2015), Sepinwall takes readers on a spin through 12 television shows that changed the medium forever. The book takes readers behind-the-scenes of 12 groundbreaking TV dramas, including “Oz,” “Deadwood,” “The Wire,” “The Shield,” and of course “Breaking Bad.”

Sepinwall isn’t in it to merely recap the plots – he speaks to the writers, actors and directors who made the shows happen, and puts their information together with his own insights to show how this new form of drama developed. Sepinwall also discusses how his book, at first self-published, became a New York Times favorite, and shares what he’s added to this new version. (Spoiler alert—don’t listen if you still don’t know how “The Sopranos” ended, but do tune in if you want Alan’s incisive take on Tony’s family’s final fade-to-black.)

You’ve seen the shows – now go behind the curtain with Sepinwall and podcast host Gael Fashingbauer Cooper as they remember the characters and plots that ushered in this new golden age of television.

New Books Network