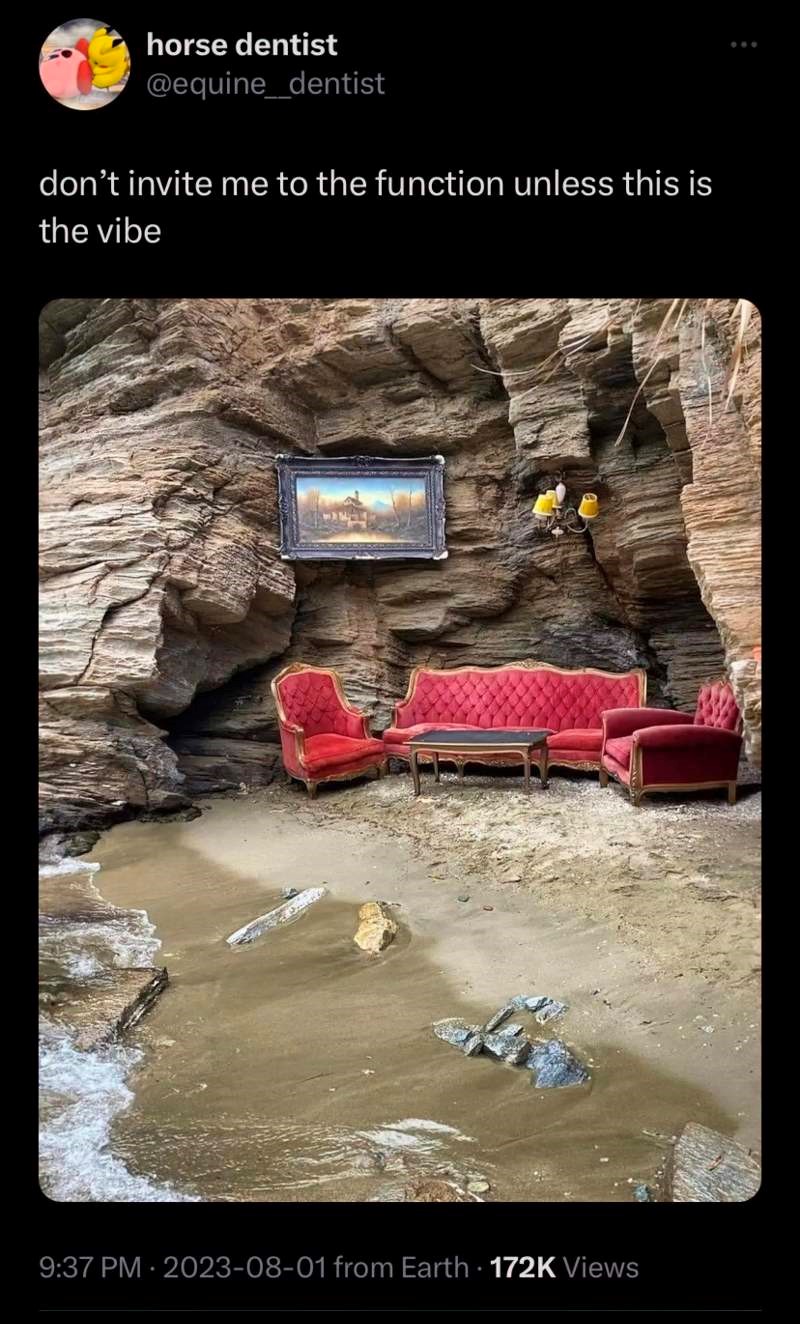

In symbolism, there is often a manmade and naturally occurring equivalent. The tunnel is the manmade version of a cave, the sewer a sea (littoral) cave.

Jack Panton’s weakness was caves. Where another boy would go mad over football, postage stamps, birds’ eggs or running away to sea, Jack Panton studied caves. He collected books about them, and photographs and engravings, and had at his finger ends―and his tongue’s end, too―all the information, I verily believe, that has ever been published concerning them. Jack had never been in a cave―that is to say, nothing bigger than the caverns in the serpentine rocks of Kynance Cove at the Lizard―but he was so familiar with their internal geography and measurements, and the strange beasts that inhabit them, that I have often fancied I was listening to the descriptions of a traveller and keen observer as he has talked to me of the great caves of the world.

I have had many a long chat with Jack upon his pet subject; not because Jack has forced it upon me, for he is no bore. But he is quite ready to be drawn out by an appreciative listener, and when he feels he has got that―well, he lets himself go. I had always thought caves were uncomfortable places, chiefly patronised by people of bad character, outlaws, bandits, smugglers, and the like; but Jack taught me to look upon them with a different eye. He would start off with the caves of the Bible, and get on to Kent’s Hole, at Torquay, and the Brixham Cavern, with the wonderful exploring work carried on in them by Mr. Pengelly, who found the bones of the great woolly elephants―the mammoth―bears, rhinoceros, reindeer, cave-lion, hyena, and other cheerful beasts that used to range the hills of Devon. Then would he drift to Fingal’s Cave at Staffa, and glance in passing at Whernside, and the Derbyshire caves, but before long would have you safe in the caves of Adelsberg in Southern Austria, or the Mammoth Cave of Kentucky in the United States of America.

Opening to “A Night Underground” from the late 1800s children’s book A Night In The Woods And Other Tales and Sketches

LITTORAL CAVES

Wildly here without control,

Robert Burns

Nature reigns and rules the whole;

In that sober, pensive mood,

Dearest to the feeling soul,

She plants the forest, pours the flood:

Life’s poor day I’ll musing rave,

And find at night a sheltering cave.

In eighteenth-century England, a fad swept the upper class. Several families felt their estate needed a hermit, and advertisements were placed in newspapers for “ornamental hermits” who were slack in grooming and willing to sleep in a cave. The job paid well, and hundreds of hermits were hired, typically on seven-year contracts, with one meal a day included. Some would emerge at dinner parties and greet guests. The English aristocracy of this period believed hermits radiated kindness and thoughtfulness, and for a couple of decades it was deemed worthy to keep one around.”

Michael Finkel, The Stranger in the Woods: The Extraordinary Story of the Last True Hermit

OTHER CAVE SYMBOLISM

- The pool is the manmade equivalent of a pond. This symbolism is utilised by Helen Simpson in her short story “Up At A Villa“.

- The atrium is the manmade equivalent of Heaven / sky.

- The cathedral is a manmade attempt at a forest. (So is a barn, e.g. in Charlotte’s Web.)

- The cauldron is the manmade, utilitarian equivalent of a woman’s womb.

- This is a bit different again, since both rugs and gardens are manmade, but the Persian rug symbolises a garden. (Check our my post on heterotopias.)

The list goes on, but you get the idea.

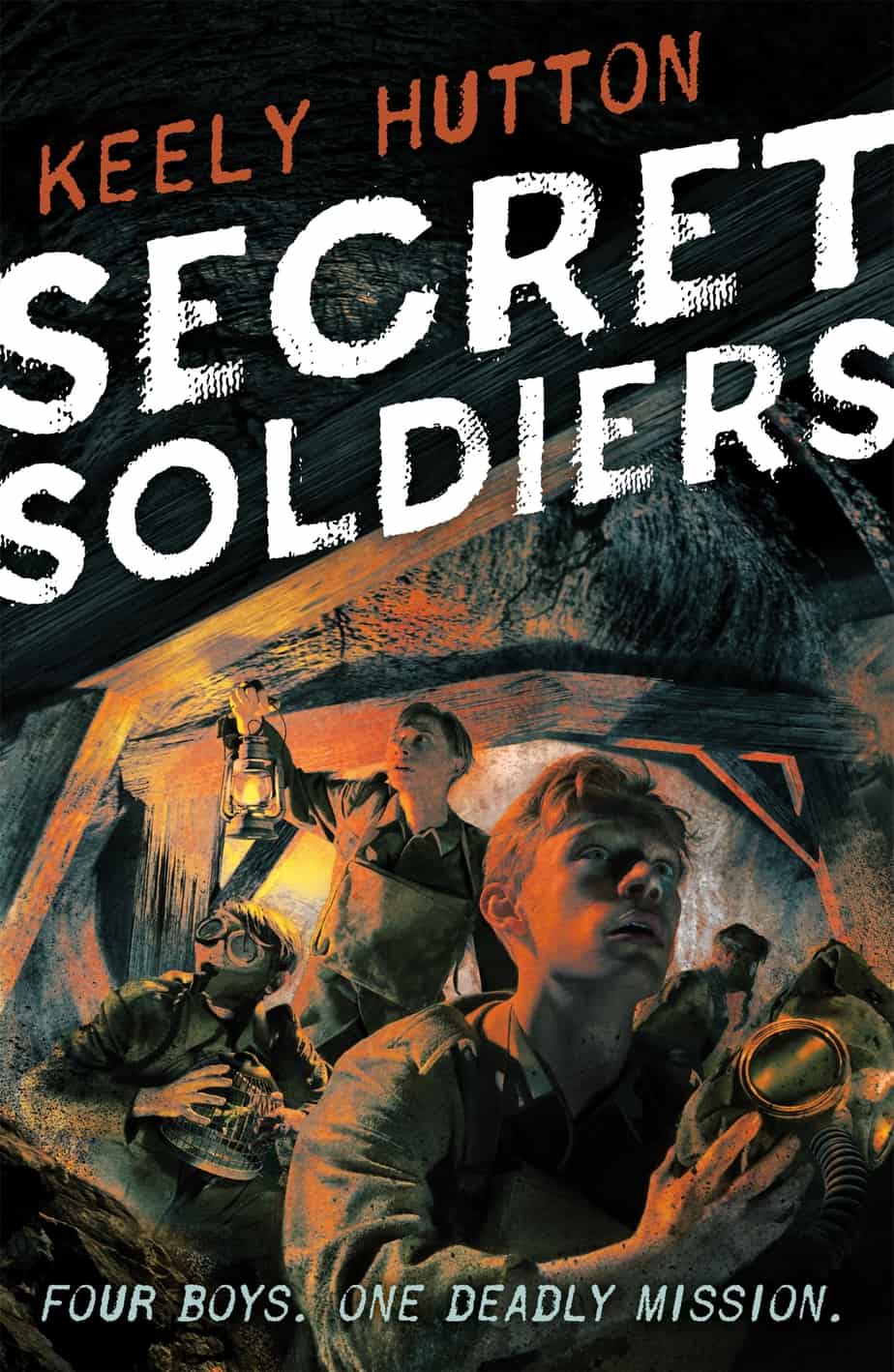

Over a quarter million underage British boys fought on the Allied front lines of the Great War, but not all of them fought on the battlefield―some fought beneath it, as revealed in this middle-grade historical adventure about a deadly underground mission.

Secret Soldiers follows the journey of Thomas, a thirteen-year-old coal miner, who lies about his age to join the Claykickers, a specialized crew of soldiers known as “tunnelers,” in hopes of finding his missing older brother. Thomas works in the tunnels of the Western Front alongside three other soldier boys whose constant bickering and inexperience in mining may prove more lethal than the enemy digging toward them. But as they burrow deeper beneath the battlefield, the boys discover the men they hope to become and forge a bond of brotherhood.

Basically, caves and tunnels recreate darkness and night-time, so naturally inherit much of the symbolism of black, darkness and night.

Other associations:

- secret, hidden space

- the universe

- security

- impregnability

- the womb of Mother Earth (the vagina would then be the entrance)

- mothers in general, fertility

- hell

- resurrection and rebirth (the Easter Bible story)

- place of initiation

- place of earthly energy

- burial

- the human mind, especially the unconscious and subconscious, or the primitive part of the self, or where Self meets Ego. Perhaps this is what Virginia Woolf meant when she chose the word ‘tunneling’ to describe her technique of how she burrowed into her characters’ backstories in order to show who they are in the present.

- the heart and centre (especially in Hindu tradition, where Atma is seated)

- a liminal space where the divine meets the human

- a place of refuge (especially robbers)

- primitive shelter

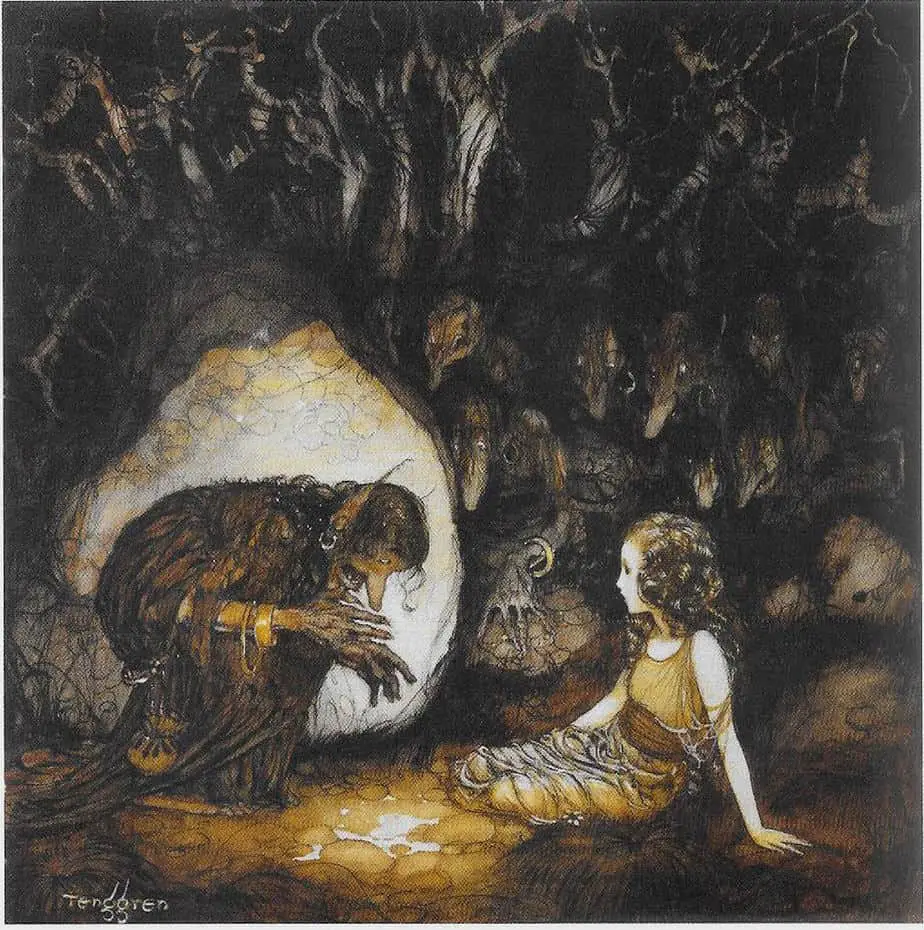

- where gnomes and monsters live

- where failed mothers hide in shame (e.g. Lamia, wicked cannibalistic fairy-ancestor of Greek myth)

In the highlands of Papua New Guinea, where people literally believe their villages and families comprise multitudes of witches, even babies aren’t safe. This is apparently because witch mothers take their babies to the cave at Owia Stone:

[Witch mothers] go to the stone, and file their teeth and when they see that they are sharp, then they know that the child is ready. They can eat people now … kill people … destroy people. From the time they are babies they are prepared …. Now many of the little children — they are witches. But you can’t tell ….

Bad things happen in caves! Equally, though, to enter a cave can symbolise entering the womb, or somehow returning to one’s beginnings. Safety, not danger.

Passing through a cave can symbolise overcoming some kind of dangerous obstacle, leading to rebirth and anagnorisis.

In Native American tradition, a series of caves one above the over symbolises the different worlds.

In Celtic tradition the cave is the portal to another world. In the music video below (99 by Elliot Moss), the tunnel is also used as a portal to a person’s emotional landscape.

In China the cave is the feminine, the yin, and the gate to the Underworld.

According to Jewish thought, Obadiah is supposed to have received the gift of prophecy for having hidden the “hundred prophets” from the persecution of Jezebel. He hid the prophets in two caves, so that if those in one cave should be discovered those in the other might yet escape.

THE ALLEGORY OF THE CAVE

The Allegory of the Cave is a Platonic story in which Plato has Socrates describe a group of people who have lived chained to the wall of a cave all of their lives, facing a blank wall. The people watch shadows projected on the wall from objects passing in front of a fire behind them, and give names to these shadows. The shadows are the prisoners’ reality. Also known as Plato’s Cave.

In Plato’s Republic, Socrates, Plato, and several of their fellows debate the nature of ideal government. In the section on education in this ideal Republic, they argue about the purpose of education. As part of Socrates’ argument, the discussion veers into an allegory in which human existence is being trapped in a cave of ignorance, chained in place and unable to view anything except shadows cast on the wall. Some of those shadows are vague outlines of actual unseen truths beyond the perception of the senses; others are false images deliberately designed to mislead the cave-dwellers, keeping them content and unquestioning. The purpose of education becomes freeing the imprisoned human and forcing him to leave the cave, to look at the actual objects that make the shadows. Cf. Platonic Forms.

While reading Plato’s cave as an allegory of education is a common interpretation, some philosophers (especially medieval readers) often took a more mystical approach to the Greek text, interpreting the cave as the material or physical world, while the shadows were mere outline of a greater spiritual truths―hidden and eternal beyond the physical world. C. S. Lewis coopts this idea in The Last Battle, in which the characters discover after death that Narnia has merely been a crude approximation of heaven, and the further they travel in the “onion ring,” the larger and more beautiful and more true the inner rings become.

Literary Terms and Definitions

CAVES AND SEX

The cave has unambiguous sexual connotations, associated with an historically taboo part of cis women’s bodies. (Sea caves even more so.)

“You know how you feel when someone whispers to you that so-and-so is ill and you say, ‘Too bad,’ and ask what the matter is and they whisper ‘Women’s troubles’? You never pursue it. You have this vague sense of oozings and drippings, blood that insists on pouring out of assorted holes, organs that drip down with all the other goo and try to depart, breasts that get saggy or lumpy and sometimes have to be cut off. Above all there is the sense of a rank cave that never gets fresh air, dark and smelly, its floor a foot thick with sticky disgusting mulch. Yes.”

Marilyn French, The Women’s Room

CAVES AND GREEK MYTHOLOGY

The sirens in the painting below are presented to us as sexual objects. Here’s the thing about femme mythical creatures: They spend part of their history as formidable, then eventually are ‘tamed’ and rendered useful by artists and storytellers who sap their powers by presenting them as consumables.

That said, I don’t think the dangerous side of sirens has been forgotten entirely. It lurks within our collective psyche. These sirens may be presented as helpless, highly sexualised objects, but there’s something dangerous and troubling happening in the background. Where there are sirens there is trouble. Using sexuality, they are supposed to lure sailors to their deaths.

The painting below shows the Greek god Vulcan hiding in a cave. Vulcan was the only ugly god, which was a real problem because even his mother couldn’t love him. Juno kicked him off Mount Olympus. (In her defence, he did have a bright red face and cried constantly.) He fell for an entire day and night and eventually landed in water. This broke Vulcan’s legs. Fortunately for him, sea nymphs found him. They raised him. According to the painting below, he might’ve lived in a sea cave. When he grew up, Vulcan tricked his mum into sitting in a jewelled chair. This chair wouldn’t let her go, and Juno was mad as hell. Jupiter persuaded Vulcan to let her go. If he let his mum get out of the damn chair, he’d get beautiful Venus as a gift. So here’s Venus, visiting Vulcan in his cave. They didn’t live happily ever after in this cave, by the way. Vulcan returned to Mount Olympus. He had a beautiful wife now, so she compensated for his ugliness.

AUSTRALIAN CAVES

Australian Aboriginal culture also features a fearsome woman in a cave. She is similar to the Greek Lamia but has sharp teeth and cannibalises her lovers (in common with some spiders). She is a figure from a series of Aboriginal cautionary tales. These tales were designed to prevent young men from too much sexual adventure. (Others were the Mungga-Mungaa and the Abuba.)

Today, the cave is littered with broken bottles, old roof tiles, and other scraps of rubbish. But it carries an important story.

For hundreds of years, caves like this were used by local Indigenous communities to quarantine people who became sick.

“[People] probably would’ve died here,” says Aunty Barbara, a Bidjigal, Gweagal and Wandi Wandian elder.

The (Australian) Smallpox Outbreak of 1789

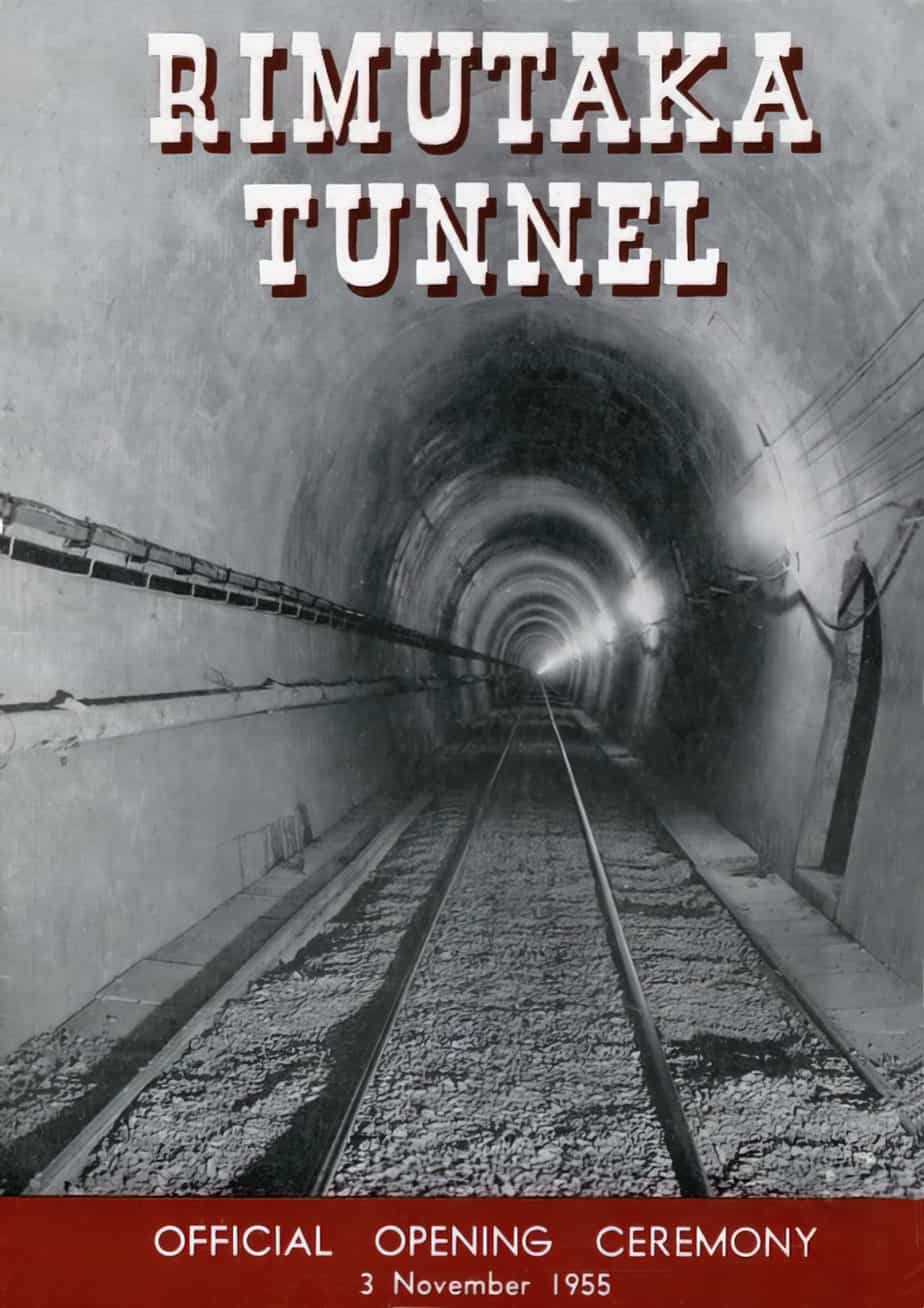

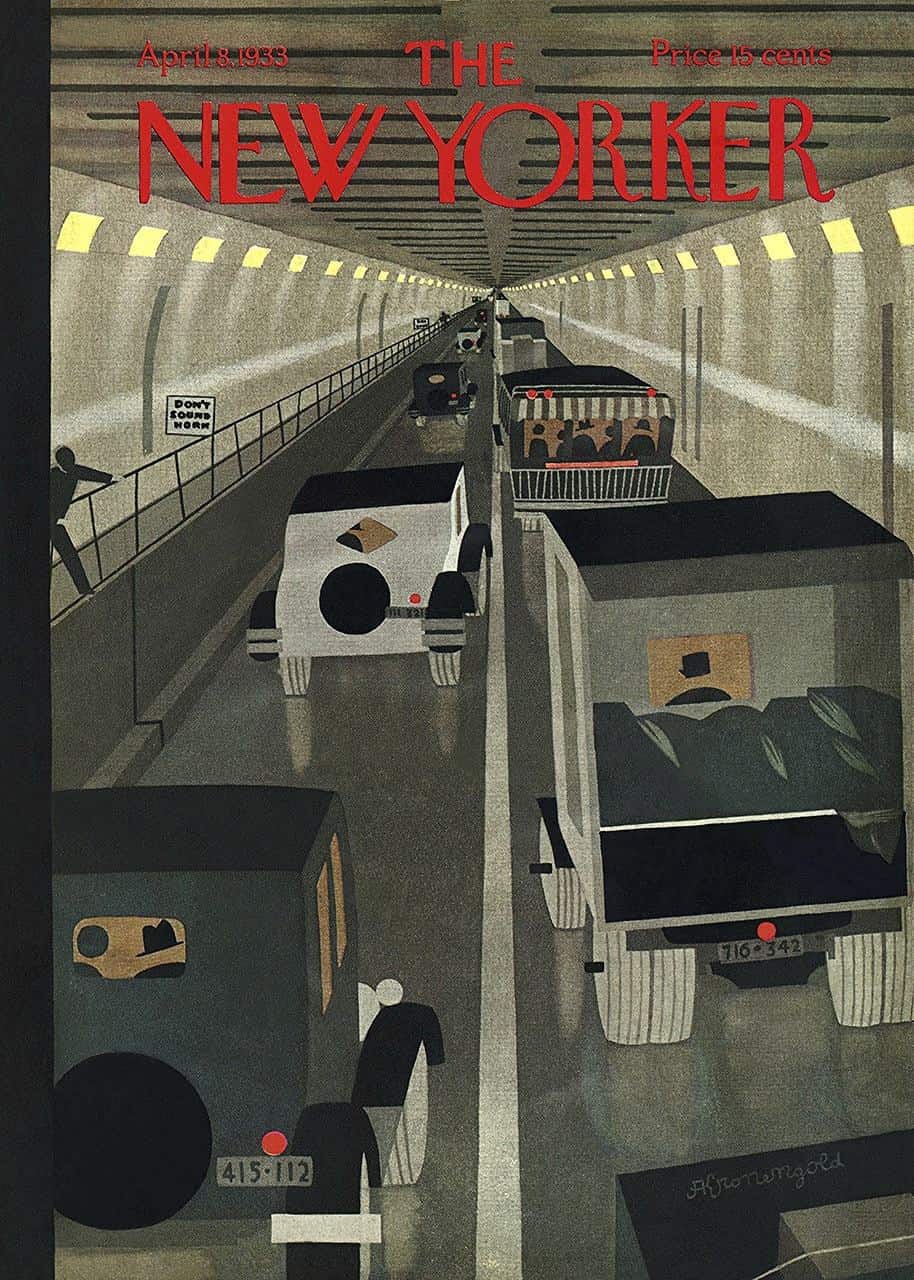

TUNNEL AS URBAN CAVE

TUNNELS AS MALADAPTIVE FOCUS

Tunnels inherit much of the symbolism attributed to caves but, on top of that, tunnels signify focus. Sometimes the dominant culture feels someone has too much focus. We call that tunnel vision. In that case the word ‘monotropism‘ is often applied to people with autistic phenotypes.

A monotropic mind is one that focuses its attention on a small number of interests at any time, tending to miss things outside of this attention tunnel.

Wikipedia

Another phrase is ‘cognitive capture’:

Cognitive capture or, cognitive tunneling, is an inattentional blindness phenomenon in which the observer is too focused on instrumentation, task at hand, internal thought, etc. and not on wider aspects of the present environment.

Psychology Wiki

Tunnel vision can have disastrous consequences. In one case, it even led to a ship wreck which continues to wreak havoc on an ecology system today, though it happened many years ago.

Torrey Canyon was one of the biggest and best ships in the world – but its captain and crew still needlessly steered it towards a deadly reef known as The Seven Stones. This course seemed like utter madness, but the thinking that resulted in such a risky manoeuvre is something we are all prone to do when we fixate on a goal and a plan to get us there.

“His plan was risky. And his plan was not about to change. […] While this may seem strange to you or me, this is a natural outcome of plan continuation bias. As tunnel vision develops, we don’t even think about alternatives to our initial plan. We don’t have the bandwidth. We continue to plough on.”

DANGER: Rocks Ahead! from the Cautionary Tales podcast

Various folk tales allude to dangerous obsessions, for example “The Red Shoes” by Hans Christian Andersen.

TUNNELS FORGING A PATH

Tunnels, more than caves, are also thought to lead somewhere. tl;dr: Nowhere good. In stories they are often a kind of portal.

Hayao Miyazaki features many caves in his anime. I’ve written about tunnels in Totoro and Ponyo. Tunnels feature large in Japanese superstition. Until quite recently women were not meant to enter tunnels. Naturally, this restricted women to their local areas, since Japan is a mountainous country. The superstition is based on the misogynist notion that women are jealous by nature:

According to the superstition, the god of a mountain is a jealous woman who will cause accidents if a woman enters the construction site of a tunnel.

Bucking superstition, Japanese woman tunnels way to top of civil-engineering world, The Japan Times

Canadian author Alice Munro makes use of tunnel as a kind of portal in her short story “Powers“. This is an excellent example of speculative fiction with grounding in the real world. (The supernatural powers are probably no such thing… but could be.) The tunnel is therefore a good choice of fantasy portal because tunnels exist in real life and a tunnel could be just a tunnel.

Sea caves are especially scary because the tide sends water rushing in. You don’t want to hang around for too long inside a sea cave. If you get disorientated due to utter darkness you might end up drowned. This puts a natural ticking clock storytelling device on narratives featuring caves by the sea.

TUNNEL AS DISRUPTOR OF TIME

What you mean is how am I managing to cope, now that Tig has died. Am I lonely? Am I suffering? Is the house too empty? Am I checking all the boxes of the prescribed grieving process? Have I gone into the dark tunnel, dressed in mourning black with gloves and a veil, and come out the other end, all cheery and wearing bright colours and loaded for bear?

No. Because it’s not a tunnel. There isn’t any other end. Time has ceased to be linear, with life events and memories in a chronological row, like beads on a string. It’s the strangest feeling, or experience, or rearrangement. I’m not sure I can explain it to you.

Margaret Atwood, “Widows”

SEWER AS URBAN LITTORAL CAVE

In the realm of the city, the sewer is the manmade symbolic equivalent of the sea cave.

The snail under the leaf setting is an appealing horror setting, epitomised by comfortable suburbs. The definition of an snail under the leaf setting is ‘something rotten lurks beneath the surface’. Sewers epitomise that feeling of dread. Rats are the animal most closely associated with sewers. (Though turtles may have stepped into that mental picture for kids of the 80s and 90s.)

FURTHER READING

Header painting: William Shayer Senior – Scene Near Zeldkirch in the Tyrol