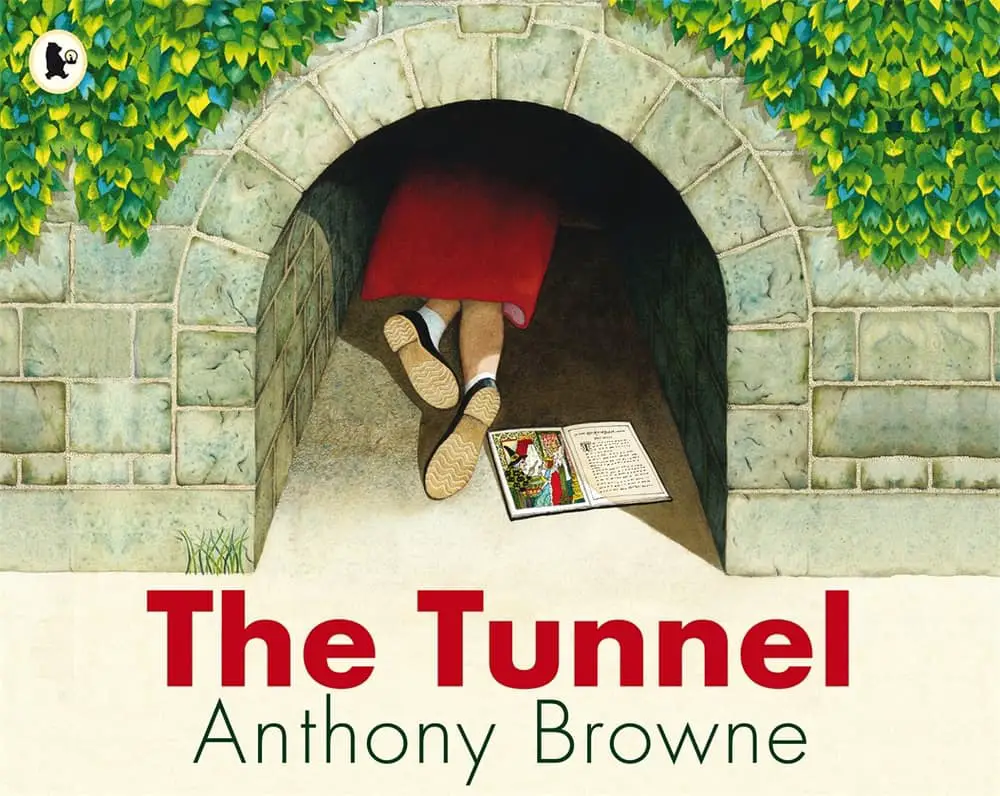

The Tunnel is a picture book written and illustrated by British author/illustrator Anthony Browne. The Tunnel was first published in 1989.

SETTING OF THE TUNNEL

In the 1980s it was far more common for kids to be sent out of the house because their mothers were sick of them (and it was almost always the mothers doing the caregiving). “Get out of the house, you kids! I don’t want to see you again til dinnertime!” The mother in this story is a little kinder than that, but I’m reminded of the vibe.

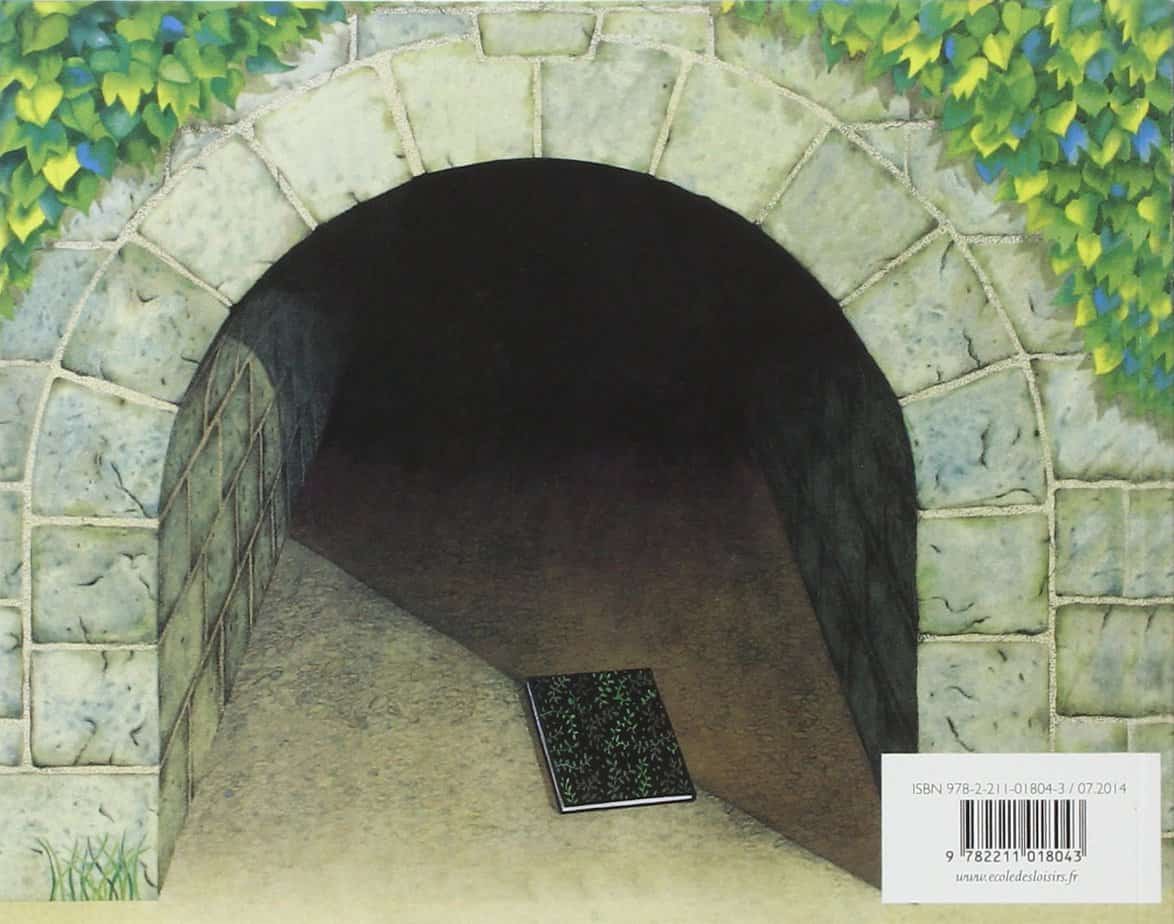

So the kids go to a wasteland which just so happens to have a fantasy portal in the shape of a tunnel. The tunnel appears to be manmade. Tunnels are an inherently scary feature of the urbanised landscape. Stephen King made the most of this in the 1980s with IT (you know, with the clown and the red balloon.) Australia’s own Paul Jennings also wrote a tunnel/sewer story. See “There’s No Such Thing” in his Unbelievable collection.

The tunnel/sewer is, symbolically, the man-made equivalent of the forest cave. It makes sense that humans have developed a fear of caves. Wild creatures tend to sleep in there, and if not wild creatures, perhaps other humans. Humans have always been the most dangerous ‘creatures’ to humans. We’re called super predators for a reason.

There’s a strong Narnia vibe to this one, though I guess all portal fantasies which start in the normal world and land kids in a wooded area are going to remind me of Narnia. On top of that, we’ve got the boy who is turned into stone, a trope utilised by C.S. Lewis, and which can be found in fairytales much older than C.S. Lewis.

Anthony Browne’s fantasy world offers nothing by way of explanation. We are never told what, how or who turned the boy into stone. Readers are left to create that part of the story for ourselves. Anthony Browne’s books expect the reader to craft at least half of the narrative, which is part of the Surrealist, postmodern experience.

As you read Anthony Browne’s books, look carefully at the skyline. In this story, as well as in Zoo, Browne lines the horizon with industrial buildings to convey a fearful, repressed emotion in the young characters. In this particular story, the skyline buildings change as the characters start to view them differently.

The painting below is by a Russian artist, and features a similar line of industrial buildings between landscape and sky.

STORY STRUCTURE OF THE TUNNEL

PARATEXT

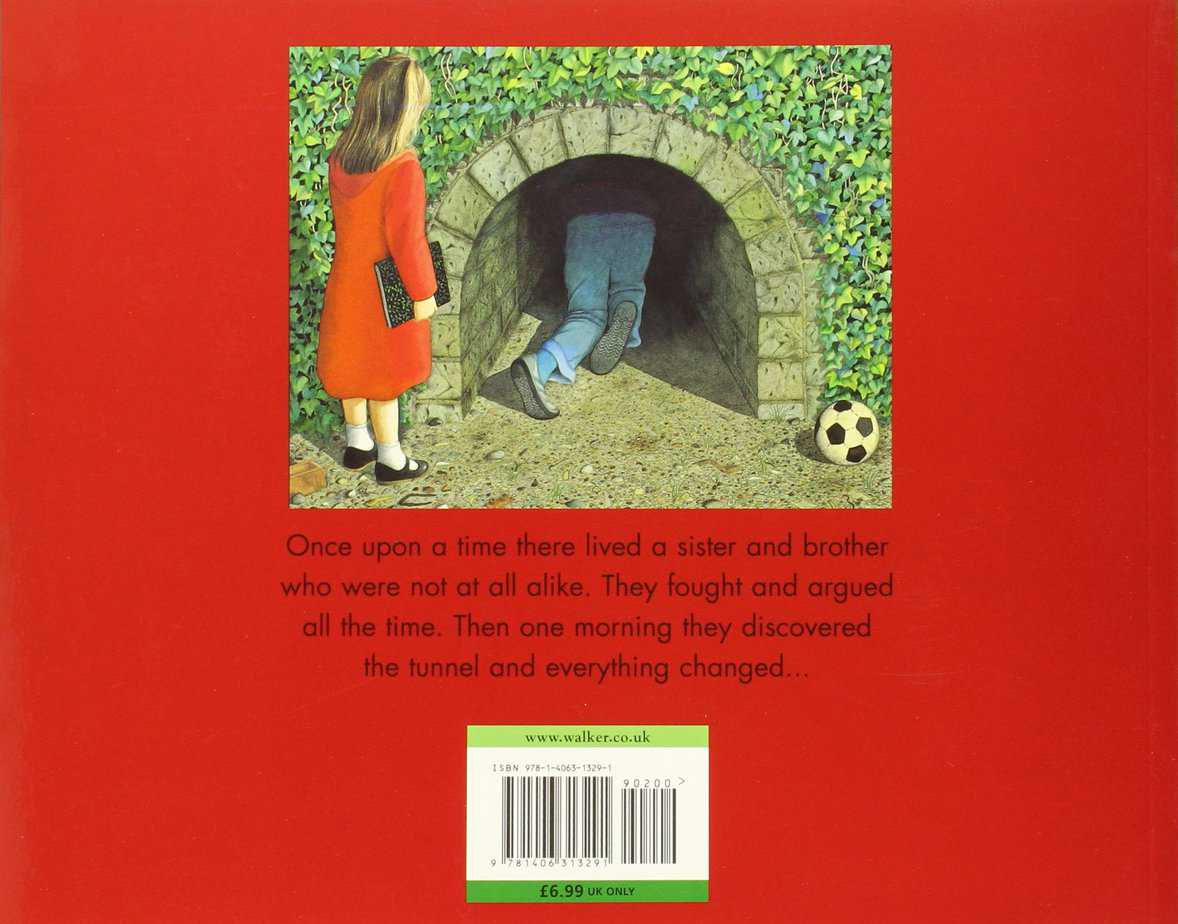

Jack fearlessly explores the tunnel he found while playing, but when he doesn’t return, his sister Rose goes in the tunnel to find him.

MARKETING COPY

SHORTCOMING

I’ve noticed contemporary children’s storytellers are a little wary of relying on such gendered stereotypes to open a story, but in the 1980s, this wasn’t on many people’s radars. It is fully expected by a typical 1980s reader that the girl is the indoors bookish type, contrasting with the outdoorsy brother who can’t sit still.

Although in The Tunnel Anthony Browne relies on a gender binary which now feels outdated, Browne’s books have always conveyed femininst ideas. For an example of how Browne understood the dilemmas facing working women in the 1980s, see another of his books, Piggyback. When women entered the workforce, their husbands did not, en masse, pick up the slack at home. The woman in that book literally ends up with her husband on her back. I can’t think of a more overtly feminist picture book.

Although contemporary readers can be wary of a story which opens with stereotyped gender roles such as found in The Tunnel, it’s worth asking: Must writers always avoid doing this in order to appear feminist? There are two ways of looking at this, because as readers learn after reading the entire story, the fear of the girl is not a bad thing within the world of the story. It isin fact her bookish knowledge of fantasy portals which will save them both.

The weakness of the brother: He has already absorbed the toxic idea that to show fear is to show weakness. Our culture is still teaching boys that the only acceptable negative male emotion is anger. Fear, sadness and other softer emotions are still unacceptable for some boys. This story will be critiquing that.

DESIRE

The children are driven out of the house because their mother desires peace and quiet. The girl wants to continue reading, and takes her book to the wasteland. The boy wants to continue playing and exploring.

OPPONENT

The brother and sister are so different they make natural opponents for each other. These kids are given names but they are not especially individuated. (Hint: If a boy is called Jack he’s probably meant to be the Every Boy.) These siblings are the archetypal ‘boy’ and ‘girl’. (The Every boy and Every girl are still able-bodied and white. Any intersectionality is considered ‘extra’ and characters are no longer considered universal. This is a huge problem which children’s media is yet to overcome.)

The Minotaur opponent — the thing which changes the boy into a statue — is unseen. But the scary forest world through the tunnel is plenty menacing.

PLAN

The brother explores the wasteland.

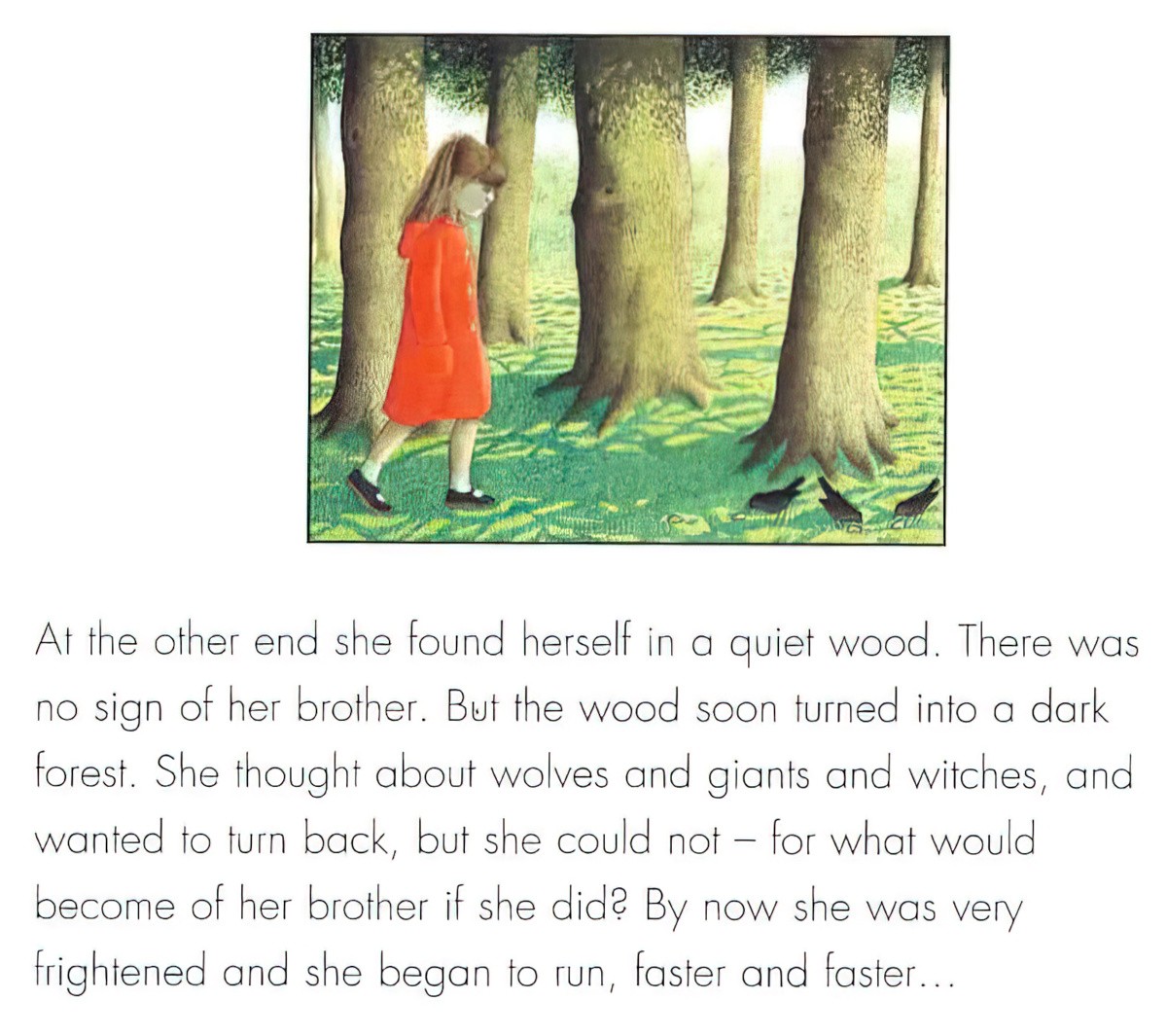

The girl sits down with a book. She is eventually forced to go into the tunnel when her brother crawls through and fails to come out. She is forced to ‘feel the fear and do it anyway’, as Susan Jeffers said in her 1987 bestselling self-help book. This was a message aimed at women, especially. The Tunnel may be the standout picture book version of the same message. When mothers were required for financial reasons to enter the workforce in large numbers, many women were thrust into a life they had not expected for themselves. It was scary.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

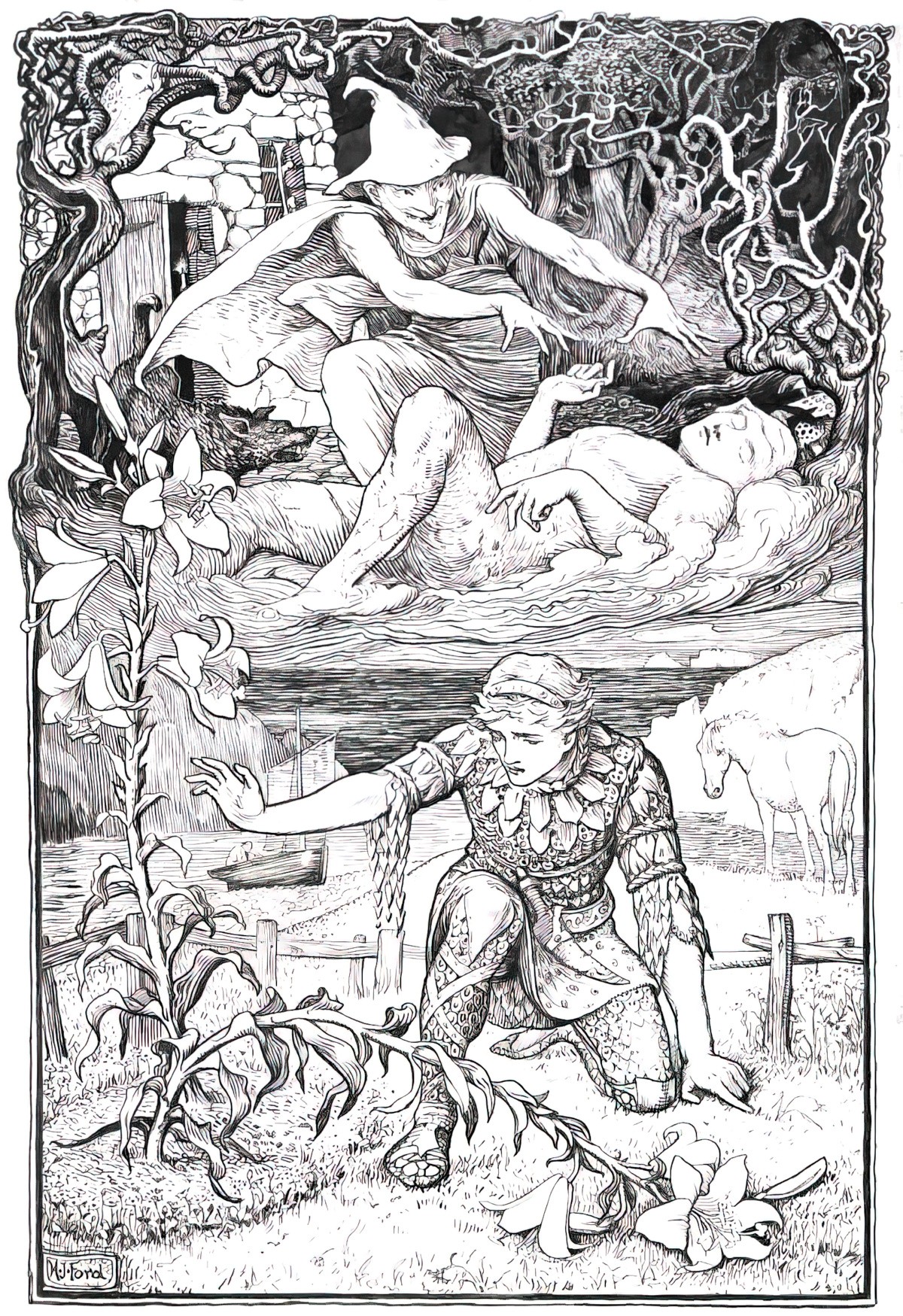

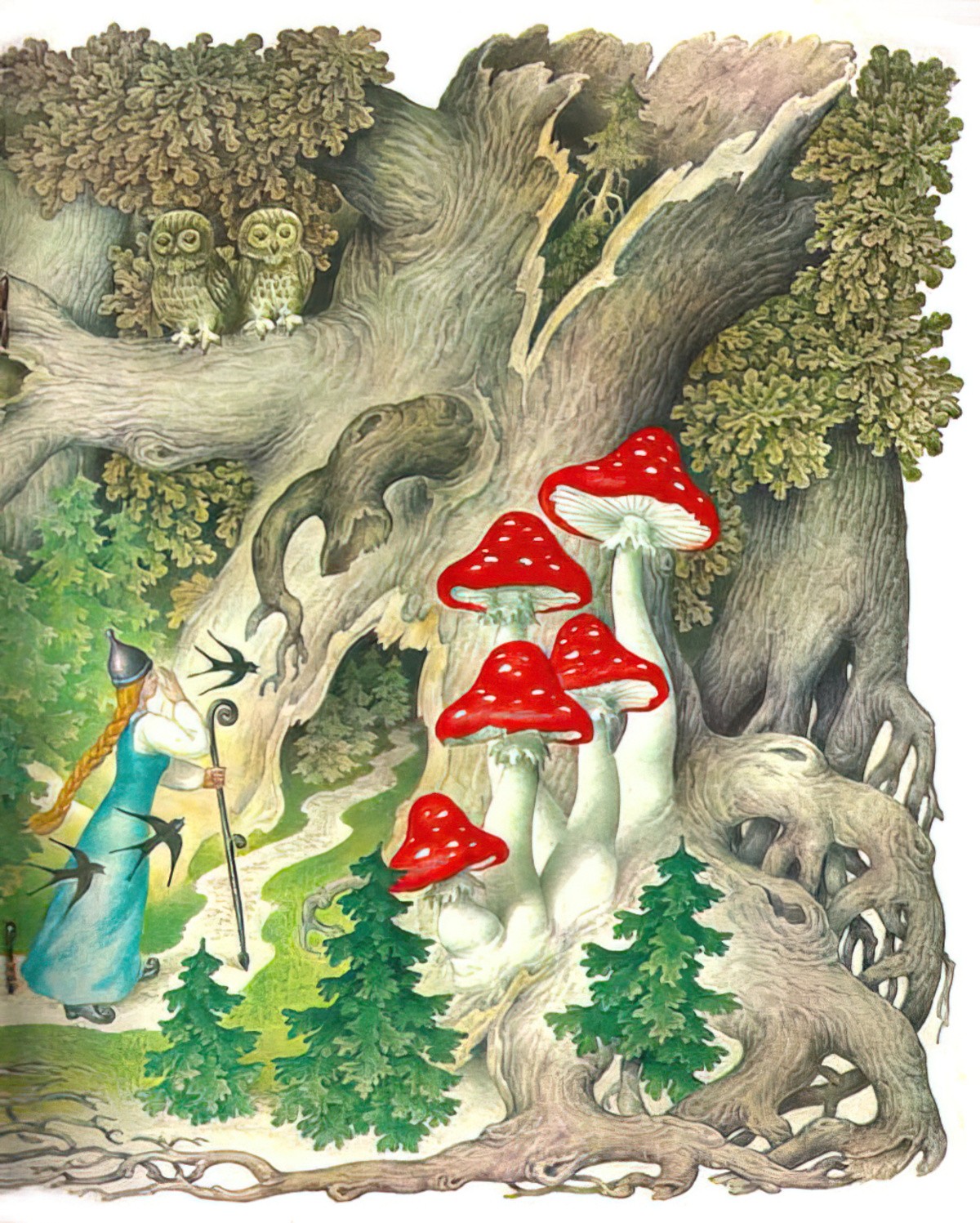

Below is a similar art style but from a Russian illustrator:

The girl’s fear of losing her brother overwhelms her fear of entering a tunnel, which she correctly deduces may take them to a parallel world where physics works in unexpected ways. Anthony Browne makes sure to show the reader an open page of her book. This story therefore has the double function of promoting literature — if you read, you’ll be well-equipped to handle whatever life throws at you.

ANAGNORISIS

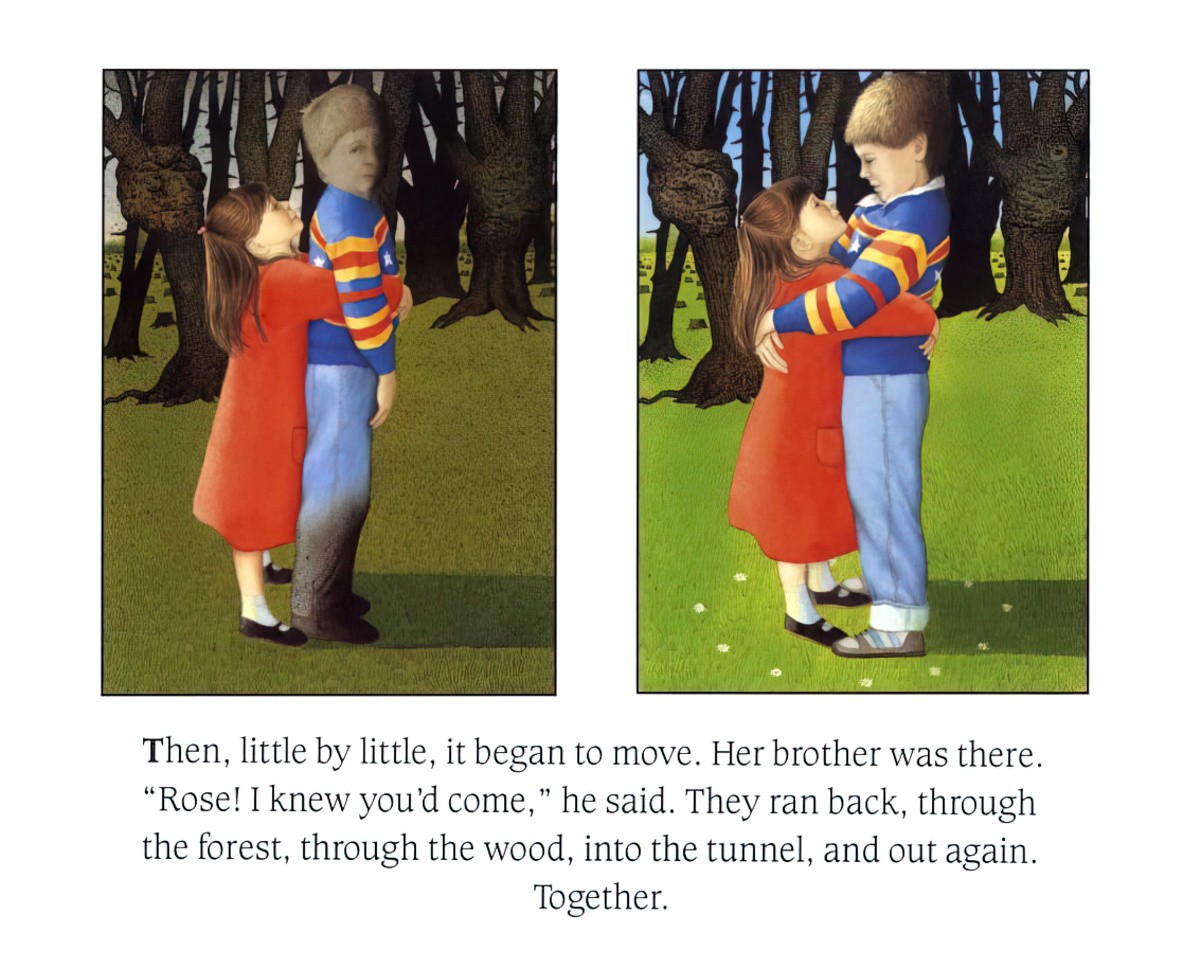

When the sister hugs the brother and warms him up to bring him back to life, the reader realises that her love works like magic.

NEW SITUATION

The brother and sister are now getting along. They return home. They share a secret which they’re not about to share with their mother.

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

It was an unexpectedly feminist 1980s inversion to tell a story in which a sister saves a brother. Normally it worked the other way around, especially in 1980s computer games, where the hero was always masculo- coded and the reward at the end (if you clocked it) was a literal princess.

So there’s that. This is also an age-old story of the girl saving the day via thoughtfulness and kindness. The trouble with this plot, when it happens over and over again for 3000 years since The Odyssey, is that readers absorb the idea that it’s the job of girls to manage the troublesome emotions (or lack of range of emotion) in boys. This is another take on the Female Maturity Formula, in which girls are little mothers. Although the girl saved the boy in this story, it was by using stereotypically feminine means. A hug. Love. The sort of care a mother would dish out after her child fell off a swing.

The Tunnel is an excellent example of that really uncomfortable reality in which a story can be feminist as a standalone, but not so much when considered as part of a corpus.

RESONANCE

We are starting to see stories in which girls have their own adventures, without feeling responsible for fixing the specifically masculine weaknesses in boys.

We are also starting to see more stories starring boys with the full range of emotions. We are There doesn’t need to be a little mother teaching them how to feel — these new boy characters have already learnt this when they come onto the page in statu nascendi. Pixar’s Up is good in this respect, although Pixar otherwise makes much use of the Female Maturity Formula in its other stories. (Roberta Seelinger Trites actually named it the “Pixar Maturity Formula” when she came up with it — I only drop the “Pixar” because I see it absolutely everywhere.)

We are also starting to see picture books which challenge the very notion of a gender binary. An excellent Australian example is My Shadow Is Pink by Scott Stuart.

FOR FURTHER INVESTIGATION

Another artist who reminds me of Anthony Browne: Harry Kingsley.

Tristam Hillier is another. Hiller was a British artist who lived from 1905 to 1983. Like Anthony Browne, his artworks could look unsettlingly cosy or outright post-apocalyptic. His subject matter was mostly barns, small villages and farmhouses.