When I was in Form 2 (now called Year 8), our teacher set a transactional writing exercise: Does violent media make a culture more violent?

I’d never heard of Rudine Sims Bishop who, five years earlier, in a different hemisphere, had been writing about how story functions as a mirror as well as a window, and also as a sliding glass door. I could’ve applied this to violence as well as to representation if I’d known about it.

This was pre-Internet. I had no opinions on the topic of Violence In Media. My essay got stapled onto the classroom cork board, I remember that much. This was a minor humiliation because the teacher had ruled a red line through my final sentence, which is the one sentence I do remember: ‘So what are you going to do about it?’ My passive attempt at turning punk was thereby stymied for all to see.

I’ve since thought more on this topic. I’m close to someone who sometimes plays first person shoot-em-ups and reads extensively and deeply about war, yet he’s the most laidback, non-confrontational person I’ve ever known. He rejects any claim that there’s a direct causal, one-way link between violent content and violent behaviour.

On the other hand, the analysis of someone like Anita Sarkeesian (Feminist Frequency) demonstrates that if we regard media as a corpus, the corpus becomes a behemoth and gains the power to influence culture itself. Not one of us is fully immune to that.

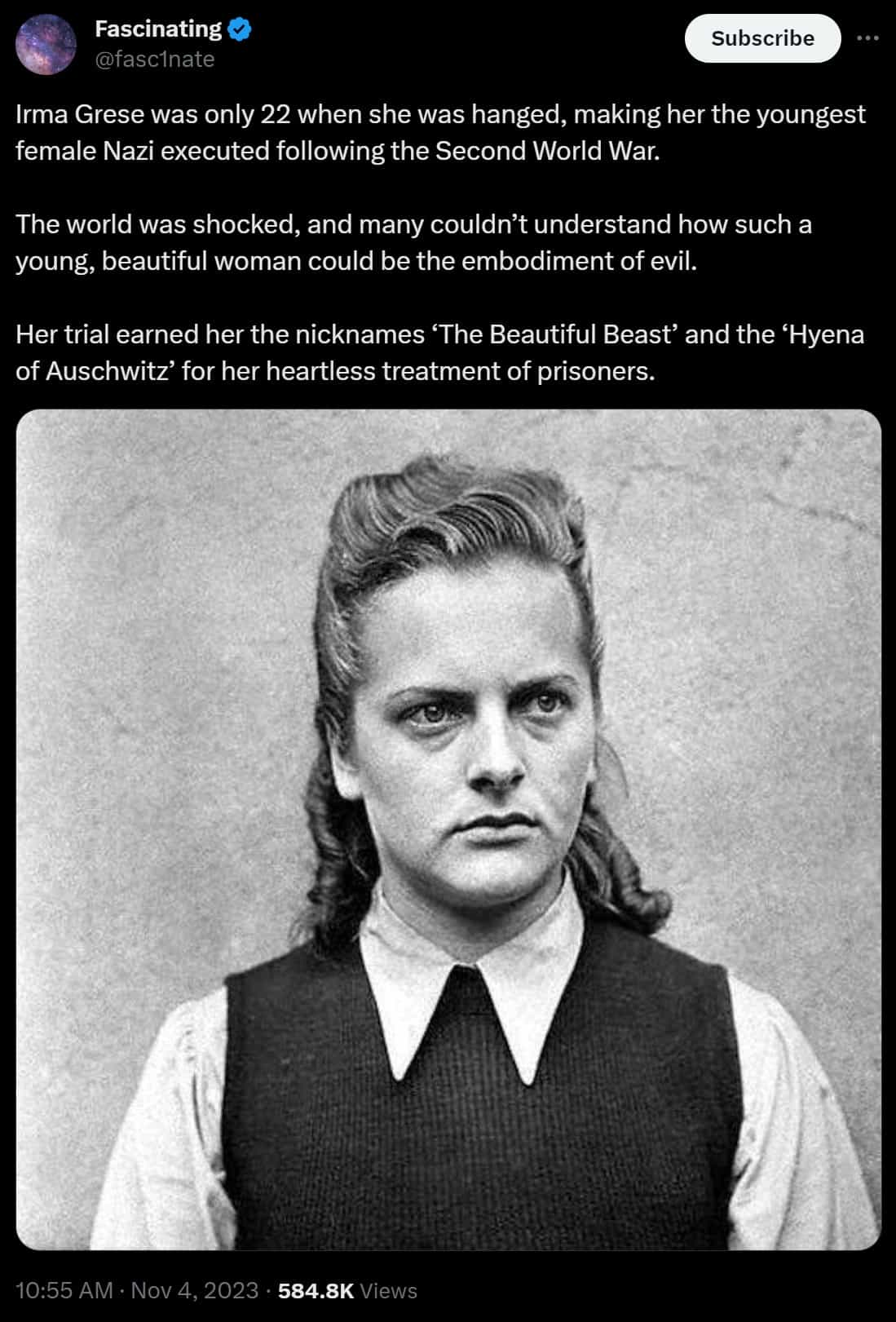

More recently I’ve been mulling over the fact that women are the main audience of true crime stories. This doesn’t surprise me at all, in part because I am a woman with some appetite for (thoughtful, well-handled) true crime.

I do get to a point where I can’t take any more, but I am fascinated by the semi-autobiographical works by Helen Garner, who attends trials and then processes her own feelings on the page. (See Joe Cinque’s Consolation and This House Of Grief.)

The most unrealistic thing about the “women solving crimes” genre is that the women aren’t CONSTANTLY getting complaints from weird old men that “solving crimes is a man’s job” and “a woman’s place is in the home, not solving murders on a train.”

@sketchesbyboze (Owl! At The Library)

I stopped listening to Casefile (a popular Australian podcast) when I noticed the anonymous host fails to pay victims sufficient respect. In line with the media reports he’s been reading as research, he is inclined to make excuses for male perpetrators of domestic violence.

In contrast, I admire the work of Laura Richards, a British Criminal Behavioural Analyst who critiques true crime shows on her podcast, and who is also active in changing outdated laws which put victims at further risk. Richards has changed the narrative around coercive control. In her discussions, Richards makes a point of acknowledging the victims and humanising them.

TRUE CRIME AND WOMEN

Like all kinds of stories enjoyed mainly by an audience of women, there’s a lot of dismissive harrumphs around the category of true crime. Why would you even read that? Is that not revelling in violence? Aren’t you supporting an industry that requires violence? And surely, surely, violent stories make us more violent, whether or not these stories are ostensibly true. (And what about paying respect to the privacy of victims? An adjacent matter; many families want memories of victims preserved via amplification.)

Women are unquestionably taught to be more fearful than men. Though men are more likely to be the victims of violence, women are more likely to be victims of certain kinds of violence. Women perform all sorts of invisible labour in the name of keeping ourselves safe.

These measures range from ritualistic and self-soothing — e.g. keeping a gun in one’s handbag, to semi-effective at an individual level — e.g. leaving a party before midnight, pleasantly buzzed rather than impaired. (The perpetrator will then find someone else, which is why there should be no broad service announcements urging women to keep safe.)

Are we looking at these true crimes because we can’t look away, akin to rubbernecking past a car accident? Is it because we are trying to understand a foreign mindset? What would make someone do that to another human being? If only we could learn to identify a dangerous person, we might then avoid him.

Perhaps that’s part of it.

A few writers have helped me think about what crime might do to help us, psychologically.

First, a closing paragraph in the second essay of Not That Bad, edited by Roxane Gay.

In her essay “Slaughterhouse Island”, Jill Christman describes a self-defence class in which she learns: Unless we are able to imagine performing acts of self-defence on a perpetrator, we’ll never be able to carry them out in real life.

In that vein, might reading about acts of violence prepare us mentally? Similar experiments have been done in sport. We know that when athletes imagine putting balls through a hoop, this helps them to actually put a ball through a hoop. (We’re talking at an elite level, when physical prowess is eclipsed by mental preparation.)

The most famous contemporary example of fiction influencing real life is perhaps the true story of Terra Newell of the Dirty John true crime podcast. Terra inflicted fatal injuries upon her mother’s abusive boyfriend after he tried to kill Terra outside her apartment. Terra cites her interest in The Walking Dead as the reason why she knew to go for his eyes. She stabbed at him as she’d seen zombies do on the show.

This is a rare example of a happy ending. John Meehan was impaired due to drug abuse at the time, Terra was at peak strength due to her age, and unusually strong because of her job working with dogs. But Terra’s story has such a cathartic, satisfying ending that Dirty John was a huge success with audiences, first as a podcast and later as a Netflix series. How many of us thought, You know what, if that happens to me, I’m gonna fight like a zombie as well.

Separately, I came across the following article and thought of procedural crime, fictional or otherwise: Seeing The Unseeable: How viewing crime scene photos can be beneficial.

Allowing bereft families to view images from crime and accident scenes can offer them a path to healing.

If a focus on crime detail helps real people in real situations, perhaps when we endure gore in crime story, an audience is somehow — though safely distanced from it — creating our own ‘path to healing’ in what we are led to perceive as a dangerous and violent world.

And if women experience the world more fearfully than men do, it makes intuitive sense that women achieve a higher psychological reward from crime narratives.

Are Crime Shows Becoming Less Sexist?

Related: Why Do We Love Grimdark TV? from Bitch Magazine

Since so much horribleness goes on in the real world, I’ve reached the age where I have no time for stories about men whose motivations are spurred by the torture and murder of women. I can enjoy a good crime series, but if the crime is going to be against women, I want to see a certain amount of female agency. Sometimes this agency comes from the victim/survivor herself; at other times the focus is on the women who work to solve the crimes.

In my middle age I am sick to death of stories such as True Detective, hailed as ‘dark masterpieces’ which are about the way men deal with the rapes and gruesome murders of women in their jobs, and with the nagging, unreasonable, one-dimensional wives and girlfriends in their real lives. Even a great show such as Breaking Bad unwittingly, I believe, turns female characters into annoying, nagging sidekicks. (Vince Gilligan blamed the audience for hating Skyler; after watching that series three times I’m now sure there are things he could have done, or rather plot points he could have avoided, to make the female characters more empathetic, if that’s what he’d been going for.)

Crime writers who base their plots around the murder, rape and mutilation of female bodies need to be especially careful to go out of their way to present live women as rounded individuals. FFS, it should be part of the damn contract.

The following shows are not about the murder and rape of middle aged men. Far from it. There’s still that uncomfortable link between sex and violence in here, and crime drama isn’t for everyone.

If, like me, you would like to enjoy the suspense of a good crime show but you’d only sit through slightly more female-friendly crime, here are three series for your consideration.

THE FALL (Belfast)

A lot has been said about The Fall, which is what made me watch it in the first place.

See: You Should Be Watching The Fall, a Serial-Killer Show Like No Other from Wired

The Fall: The Most Feminist Show on Television from The Atlantic

This is a story comprising two short series, both available now on American Netflix. Gillian Anderson plays the SIO (Senior Investigation Officer) looking for a serial killer of women. From the start, the audience knows who the serial killer is. He is not the serial killer of the popular imagination. Gillian Anderson’s character has some great lines, which show she isn’t wearing the rose-tinted glasses; she knows sexism when she sees it and she calls it out. This is immensely satisfying. Needless to say, I really enjoyed it.

TOP OF THE LAKE (New Zealand)

Are you a Jane Campion fan? This is like watching a mash-up of The Piano (scenery-wise), Once Were Warriors (plot-wise) and Twin Peaks (creepiness-wise).

I predicted the outcome by episode three, but I think you’re supposed to. You’re certainly given enough clues. As I said, I’m not a crime fan, so a lot of viewers will probably work it out before I did.

Unfortunately I’m from New Zealand and Australia and Elisabeth Moss doesn’t do a fantastic job of the accent. You’d think they could find some decent local actresses, wouldn’t you? Then again, Elisabeth Moss would introduce this series to an American audience, thereby expanding it many times over. I guess this is how it works.

What makes it feminist? The drama is focused on Elisabeth Moss’s character, oftentimes on her relationship with her mother. There is also a community of battered women — a sort of cult, lead by an aged Holly Hunter — so it definitely passes the Bechdel Test. There are times, though, when I feel the scenes at the commune are unnecessarily comic. (Monkey? Did it have to be a monkey?) But that seems to be the nature of TV that’s made in my home country. Even the darkest stories inject these comic scenes which, to me, often feel out of sync with the vibe.

This show features more diversity than seems usual, too.

Double X presenters (in particular June Thomas) wondered what on earth an Australian police officer was doing, seconded into the New Zealand police force to fight a New Zealand crime. I wonder the same thing, but I’m willing to put it aside for the sake of a story.

Looks like there might be a series two coming? Season one certainly doesn’t feel entirely wrapped up.

HAPPY VALLEY (Yorkshire Valleys)

The thing that makes Happy Valley a standout for a feminist audience is:

1. The drama focuses around the female police officer just as much as it focuses on the life of the male criminals.

2. Whereas in The Fall, everyone rushes around Gillian Anderson’s character because she is senior and because she needs to be listened to (also refreshing) this show very accurately depicts some of the problems with being a female working in a mostly male environment. Part of this police officer’s problems stem from the fact that she used to be a detective, but took a demotion for family reasons (also relatable to many women), and is struggling to work under people who have vocational deficiencies.

3. The main confidante of Lancashire’s character is her sister. (Cue: Bechdel.)

4. The main character is far from perfect. (Watching a martyr would be unrelatable.)

5. The characters on here are dealing with things that romanticised characters on similar shows manage to avoid, by dint of being super smart or super sexy or something. For example, the grandson is dyslexic. There is addiction in the family. There’s the family female friend dying of cancer in early middle age. There’s PTSD, which has a real effect on the main character’s behaviour. This is a level of realism that can only be achieved by understanding the real, everyday lives of women.

I absolutely loved Season One of Happy Valley and Season Two was just as good.

THE KILLING (Copenhagen or Seattle)

I watched the AMC version set in Seattle, but I have it on good authority that the Danish version upon which it is based is just as good if not better. (It should be more of a surprise that the American adaptation is as good as it is, I guess.)

This show is still about the murder of a young woman. Sex and violence are still linked at the grassroots level.

But to balance this we do have a rounded, interesting female detective. It’s been suggested Sarah Lund/Linden is aspie — an increasingly popular trope which has also been utilised in The Bridge and its offshoots, such as The Tunnel. When you think of these female cops, think of Doc Marten. These are women who are single-minded, smart, straight-talking and damaged by something that happened in the past, wary of people. It’s a satisfying character to watch, though I note with interest that characterisations of more typically female outworkings of autism level one are still very much lacking on TV.

THE INFLUENCE OF THE X-FILES

FURTHER READING

The Ethical Dilemma of Highbrow True Crime from Vulture (possible paywall)

Laura’s Ghost: Women Speak about Twin Peaks

Miranda Corcoran speaks to Courtenay Stallings about her new book, Laura’s Ghost: Women Speak about Twin Peaks (Fayetteville Mafia Press, 2020). Laura’s Ghost is unique exploration of an iconic television series. The book focuses on the character of Laura Palmer, the beautiful homecoming queen whose murder sets in motion the mysteries at the heart of David Lynch’s eccentric small town. Through conversations with women involved in both the show itself and the Twin Peaks fan community, Laura’s Ghost explores Laura’s legacy from a host of different perspectives. Stallings speaks with the actor Sheryl Lee about her experience of playing Laura Palmer, with filmmaker Jennifer Lynch about writing Laura’s backstory in The Secret Diary of Laura Palmer, and with a range of artists, authors, performers and teachers about Laura’s impact on their lives. In this way, Laura’s Ghost excavates the layers of complexity embedded in Laura’s character, framing her as a friend, a daughter, a mischief-maker, a rebel and, most importantly, a survivor.

New Books Network

While shows like Mare of Easttown interrogate patriarchy, they also uphold it: They may offer audiences strong, female detectives as leads, but there’s still the unsettling, age-old problem of plot lines that almost exclusively revolve around the death of girls and women. A dead, missing, and/or raped woman is so commonplace on any given episode of Law & Order: SVU that its familiarity can almost become comforting: One can fall asleep to the rhythms of a woman’s murder being solved in a single episode. But the victim is never really fleshed out; she’s a black hole, an empty vessel, and a symbol of both innocence lost and the horrors of patriarchy.

Eleanor Howell, Bitch Media