Tricksters are characters who make secret plans to get away with stuff and to get what they want. Most characters in children’s literature have an element of trickster about them, but this archetype is found frequently across the history of storytelling.

In any negotiation, the one who lays out their position first usually loses because it allows their opponent to reposition accordingly and outflank them. This is true whether you want a kiss, a confession, or a treaty. Clever people play their cards close to the vest and lead their verbal sparring partners on until they can trap them with their own words.

Don’t assume that only unsympathetic or devious characters do this. All people who are clever and persuasive know they must pepper their conversation with tricks and traps.

Matt Bird. “The Secrets of Story”

Tricksters often appear as pranksters or mischief-makers. In stories for adults and young adults, tricksters can also have a sinister side.

What Is A Trickster, Exactly?

Tricksters can be found along the entire spectrum of morality. They can be supremely evil or extremely good. Most often they’re ambivalent, shifting back and forth as the story sees fit. Think Pennywise the Clown, who changes from scene to scene to be the monster the plot requires him to be.

By the way, all clowns are descended from the trickster archetype. This includes comedians, jesters, Medieval court fools, the masked actors of the Commedia dell’Arte, Punch and Judy.

Tricksters don’t care about the usual taboos, and can therefore help challenge them. They just don’t seem to care. Some of them, if real people, might be analysed as psychopaths. Because tricksters don’t worry so much about taboos, some of them are extremely scatological. For this same reason, native cultures have sometimes been reluctant to share their trickster stories with ethnographers, which means the stories have probably gone under-recorded as a result.

Some animal characters are tricksters, established by storytellers such as Aesop. Foxes, ravens and other animals who live on their wits are most likely to get the trickster treatment in our stories.

Why Tricksters Work So Well In Narrative

In his book Secrets of Story, Matt Bird ranks five levels of scene work. From weakest to strongest scenes he lists:

- Listen and Accept Scenes

- Listen and Dispute Scenes

- Extract Information or Action Directly Scenes

- Extract Information or Action Through Tricks and Traps Scenes

- Both Try To Trick and Trap Each Other And One Or Both Succeed Scenes

Notice how 4 and 5 are the most lively scenes? They both involve tricksters. Or, they both involve ‘tricks’. Even when your main characters aren’t trickster archetypes, it’s really helpful if they sometimes use trickster tools to get what they want.

An audience identifies with a trickster because we all feel like we have hidden layers (the public, private and secret self). The hidden layer of a trickster is that there is an ironic distance between what they appear to do and what they really do. Tricksters are inherently ironic, and irony is necessary for any story to work.

A Brief History Of Trickster

The word “trickster” first appeared in the Oxford English Dictionary in the eighteenth century. However, the concept has been around for a lot longer than that.

Tricksters are descended from ancient gods.

Tricksters are “beings of the beginning, working in some complex relationship with the High God; transformers, helping to bring the present human world into being; performers of heroic acts on behalf of men, yet in their original form, and in some later forms, foolish, obscene, laughable, yet indomitable.”

The Trickster in West Africa, Robert D. Pelton

The term actually refers to a variety of different character archetypes, from the magician to the wise fool. A trickster can be a shapeshifter or parahuman creature or a human simpleton who blunders into good fortune.

Simpleton: Abbreviation of simple Tony or Anthony, a foolish fellow.

from a 1703 dictionary of slang

In the Middle Ages, the Christian Feast of Fools was a celebration of tricksters. People dressed up as their perceived inverse. Men as women, peasants as lords and so on. In Catholic countries there are the Carnaval festivities — fun before the difficult days of Lent. (This is related to the term carnivalesque. Both derive from the Latin word for ‘meat’. )

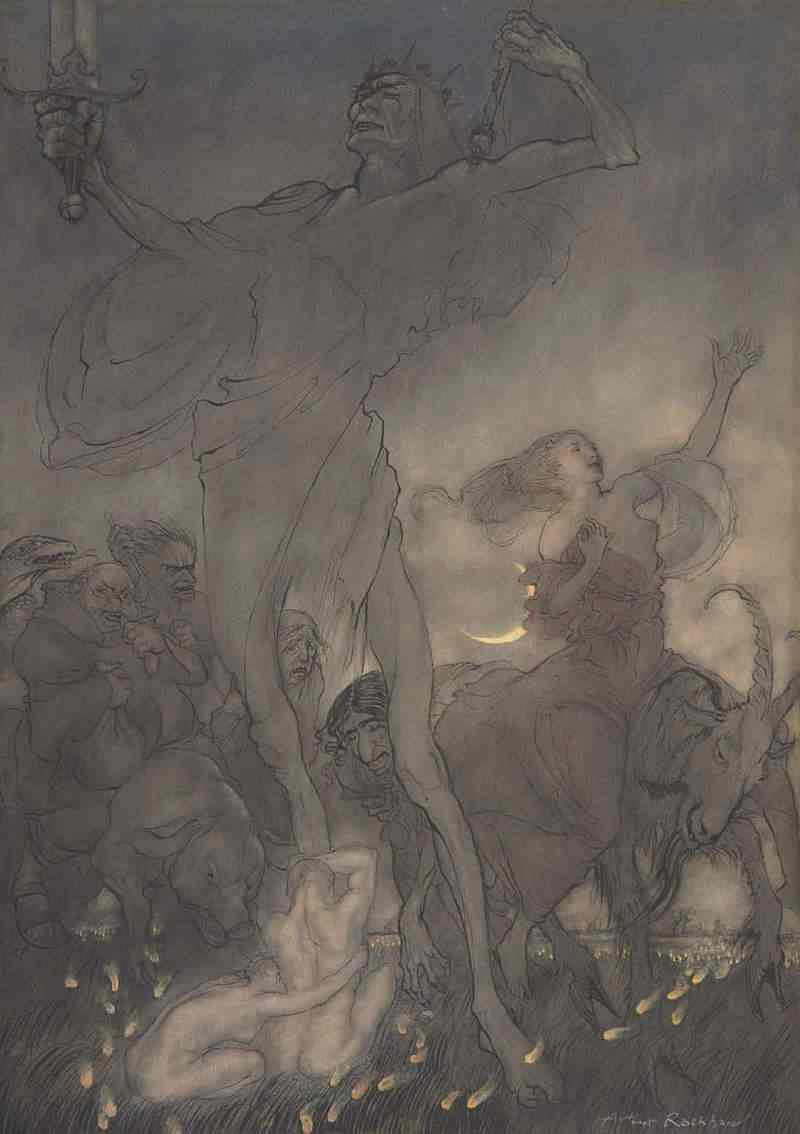

Many fairies are tricksters. Puck of A Midsummer Night’s Dream is a good example. (Puck seems to be a fairy of Shakespeare’s own invention.)

Even today, scholars argue about the definition of the term ‘trickster’, but writers don’t need to get into that. We can create any kind of trickster for our stories as we see fit.

Types of Tricksters

‘Robin Goodfellow’ (or Robin Good-fellowe) seems to be a name applied to a wide variety of apparitions and fairies, and he therefore takes various forms, including various types of tricksters.

- Household tricksters — Sometimes Robin Goodfellow is this kind of common-thief trickster, who steals people’s clothes while they sleep. We also have the category of hobgoblins. Goblins who live in the house. They are capricious and can help you with your housework but also undo everything if you annoy them, upending everything like a poltergeist.

- Will-o’-the-wisps — a.k.a. marsh spirits or moor spirits. These creatures wander about like they’re in the mist, led by a different (earlier) rendition of Robin Goodfellow. These tricksters have a subversive, demonic energy. (Fairies are less scary demons/devils.)

- The Merry Prankster — In A Midsummer Night’s Dream Puck says he likes to pull chairs out from under ladies. However, he doesn’t actually do this on the stage. The wish to be a merry prankster exposes the comic arbitrariness of erotic desire. There is no rhyme nor reason for Demetrius to desire Hermia, as there is no definable reason Puck should like to play pranks. He just does. In Shakespeare’s case, there is a symbolic use for the prankster.

Examples Across The Ages

- Odysseus/Ulysses — Ulysses is the Latin name for Odysseus, a hero in ancient Greek literature. Odysseus is renowned for his brilliance, guile, and versatility, and is hence known by the epithet Odysseus the Cunning (mētis, or “cunning intelligence”).

- Prometheus — Prometheus in European myth is both Trickster (when he steals fire from the gods) and culture hero (when he lifts the darkness for mankind).

- Hermes — the Greek god. (Mercury to the Romans). According to prominent folklorist Yeleazar Meletinsky, Hermes is a deified trickster. He is the god of messengers, of merchants, and of financial transactions — but he’s also, in his dark aspect, the god of liars, gamblers, and thieves.

- Merlin — from the Arthurian legend, perhaps based on 6th-century Druid living in southern Scotland. He causes trouble at his former wife’s wedding, for instance.

- Sirens — You didn’t expect sirens, right? Sirens have changed a lot over the course of history, from terrifying Greek flying birds who killed sailors at sea, to seductive naked girls sitting by a pool. You’ll find a lot of mythical creatures at some point went through a trickster phase, and sirens are a case in point:’ Many scholars today believe that the Sirens were considered to be manifestations of the human soul after death, and duplicitous tricksters. “The bird-woman became a death-demon, a soul sent to fetch a soul, a Ker that lures a soul, a Siren,” writes Jane Ellen Harrison in her essay, “The Ker as Siren. (Sirens are actually bird bodied messengers of death, not sexy mermaids)

- Brer Rabbit — For some reason, trickster rabbits and hares are found in stories from all over the world. Perhaps this is because they’re hard to catch, being so fast, disappearing into otherwise invisible holes in the ground.

- Hares — Hare is the primary Trickster figure of various Native American tribes, particularly among the Algonquin–speaking peoples of the central and eastern woodlands.

- Rumpelstiltskin

- Cagliuso

- Jack — There are a whole lot of tales featuring a human simpleton called Jack. They come from Great Britain and the Appalachian Mountains of North America. There’s a similar character in German and Pennsylvanian Dutch cultures. Jack and the Beanstalk

- Anansi the Spider — a trickster whose tales are known in many parts of Africa, the West Indies, and far beyond. His tales are generally humorous, with Anansi in the role of antihero. He breaks the rules, violates taboos, makes mockery of sacred things; he gets what he wants by plotting, scheming, lying and cheating. Anansi is famously lazy, greedy, pompous, vain, and ignorant — but he’s also very, very clever, usually outwitting everyone around him.

- Reynard the Fox — a European epic of the Middle Ages, probably from France, emerging some time around the thirteenth or fourteenth century. This fox is a satirical figure — greedy, wily. He dupes peasants and nobility alike.

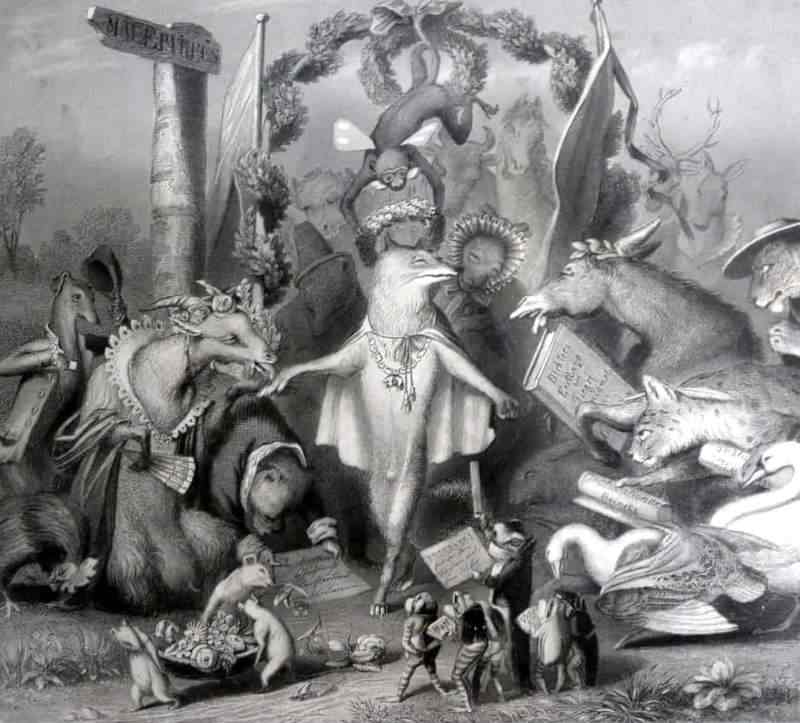

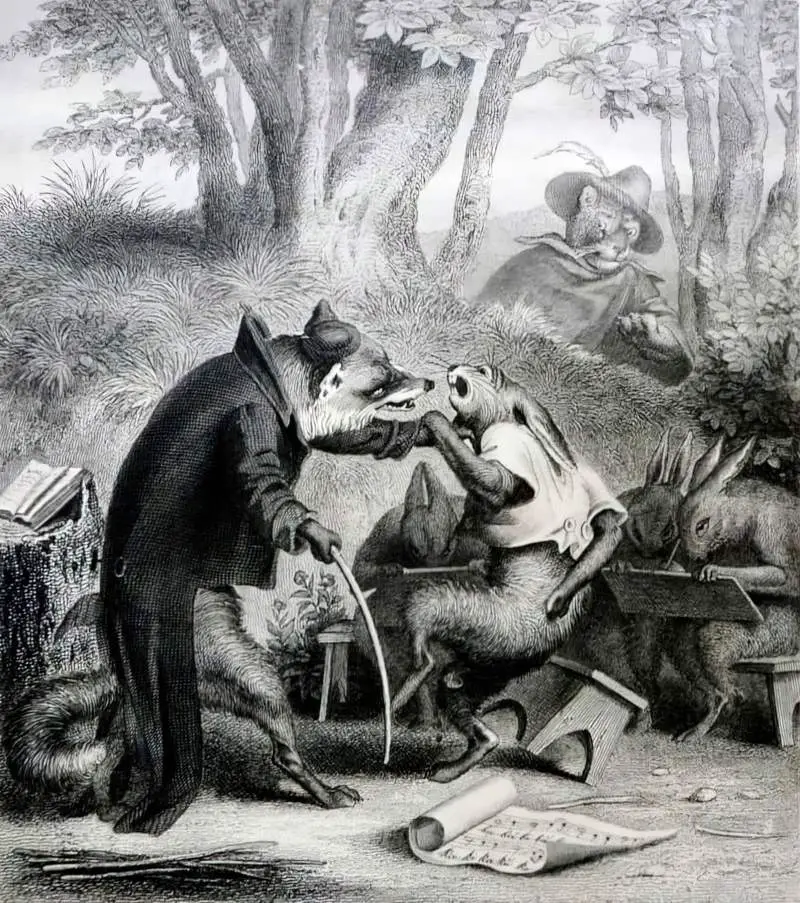

Below, illustrations from a translation of Reynard The Fox by E. W. Holloway from a German text dated 1852 with engravings on steel after designs by H. Leutemann.

- Raven — the central Trickster figure for many tribes on the North Pacific Coast of America.

- Old Man Coyote — Old Man Coyote makes the earth, animals, and humans. He is the Indian Prometheus, bringing fire and daylight to the people. He positions the sun, moon, and stars in their proper places. He teaches humans how to live.

- Coyotes in general — though this expectation is ironically explored in the Road Runner cartoon, though in common with Old Man Coyote, this one is soon on his feet again after any setback. Coyotes are the best known animal trickster in North America.

- Attauba, le petit malin devenu roi (Attauba, the smart young boy who became King) — a tale from The Ivory Coast

- Puss In Boots — a vain and silly creature, yet clever enough to win a castle and a princess for his master

- Faust — and a devil waiting at the crossroads

- A Muslim mullah

- a Zen master

- Eshu-Elegba is the trickster god of the Yoruba people of West Africa. Like Hermes, this fellow is the god of thresholds and roads. Eshu can be benevolent or malign — and is usually both these things at once, delighting in playing tricks on human beings and the other gods. Notice that the older variety of religions feature gods who are assholes but really nice also. Modern religious thought has no time for this. Why love a god who is also heinous?

- Loki in Norse mythology is full of clever pranks that both undermine and benefit the gods of Asgard. He is an irrepressible liar, schemer, thief, and lover of practical jokes; he is also a shape–shifter, with the rare ability to shift between genders. Perhaps the character of Buffalo Bill in Silence of the Lambs is (problematically) based on this Loki character. (Transphobia goes way back.) Unlike Buffalo Bill, however, Loki is exuberantly amoral.

- Maui is New Zealand and Hawaii’s folklore trickster. He may have created the world but he’s also a meddlesome troublemaker.

- Iktomi — a small but powerful creature, devious and mischievous. According to the Lakota and Dakota (Sioux) tribes of the American Midwest, it was Iktomi who created time, space, and language, and gave all the animals their names, but he’s also a thief, a glutton, a letch, and “the grandfather of lies.”

- Monkey King — famous in China

- Lord Hanuman — the Monkey God of India is sometimes considered a trickster though he is upstanding rather than amoral.

- Queen Mab — from Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet. She is mischievous but mostly benevolent, referred to as the fairies’ midwife, who delivers sleeping men of their innermost wishes in the form of dreams.

- Till Eulenspiegel — Low German Dylulenspegel, German peasant trickster whose merry pranks were the source of numerous folk and literary tales.

SCAMS AND PLANS IN CHILDREN’S STORIES

In children’s literature, baddies who plot evil are often foiled by a child or a childlike creature who saves the day. As in films for adults, some of these plots are serious and some are comical.

Almost every children’s story involves a scam scene, regardless of what we call it:

- The entire Famous Five and Secret Seven series, and all of the child sleuth grandchild books, in which groups of children outwit smalltime crooks.

- Matilda — Roald Dahl absolutely loved scams. Scams form the entire plot points of Matilda and the Twits. But every one of his books involves a scam of some kind, in which the young hero gets back at the opponent. David Walliams writes in the same tradition.

- Ramona Quimby hides her report card in the freezer because her older sister Beezus’s is always perfect, showing her own school achievements up.

- Jesse Aarons in The Bridge To Terabithia really wants to go with his music teacher to the museum, so when his mother is half asleep when he asks permission to go, he isn’t really concerned that she may not have even heard him.

- Mildred Hubble from The Worst Witch series is constantly foiled in the second book in the series by a newcomer (Enid) who Mildred is supposed to be in charge of. This newcomer is full of mischief, which is interesting because she doesn’t really mean to cause trouble for Mildred, she is simply blundering her way through the strict rules of the boarding school for witches, breaking lots of rules.

- The Pokey Little Puppy — Like Peter Rabbit, this is the character children fall in love with, even though he is doing exactly as his mother tells him not to. Perhaps we like these animals so much because they are justly punished.

- Room On The Broom — through their own creativity, all of the passengers of the broom display great team work and fool the baddie to save the benevolent witch.

- The Wee Wishy Woman of Nickety Nackety Noo-noo-noo by Joy Cowley saves her own bacon by fooling her captor into eating a stew made of glue. This is a classic fairytale ending — the clever trickster character gets away, similar to tales such as Hansel and Gretel, who fool the wicked witch by sticking out a chicken bone instead of a finger, and then by feigning ignorance about how to climb into an oven.

- Holden Caulfield from Catcher In The Rye might be called the father of Ferris Bueller, taking off from school and doing his own thing.

- Eleanor and Park each deceive themselves about how much they like each other, and then when they realise this, they must deceive certain adults in their lives. Is this the romance equivalent of a scam? I consider it as such.

- The Fish in This Is Not My Hat has already stolen the hat at the beginning of the picture book, which shows initiative. In We Found A Hat, one tortoise fantasises about scamming his friend, but ultimately realises that this would ruin the friendship.

- The Story Of The Little Mole Who Knew It Was None Of His Business is basically a revenge story in which a mole gets his own back by shitting on someone else.

- Wolf Comes To Town is all about a wicked wolf who dresses up as respectable people in order to do very bad things. This particular form of deception fails to go unpunished, though, which may explain why this children’s picture book went out of print.

- Artemis Fowl behaves badly, stealing fairy gold, but is undeniably attractive as a character because he goes after what he wants even if it’s illegal. He’s also very proud of himself.

But children’s authors aren’t usually encouraged to make use of ‘scams’, as such. I haven’t seen the word used. But I have heard advice to make use of ‘secrets’, the close cousin of the scam.

SECRETS IN STORYTELLING

Children’s book editor Cheryl Klein advises that child protagonists should have secrets:

Let the reader know there’s a secret, and then don’t tell them what it is until it absolutely serves your purpose to do so. …It could be a secret the narrator knows and is keeping from the reader…Or it could be a secret the characters have to find out.

Klein points out that the genre of mystery novels require secrets and offers the example of Lemony Snicket, an example of a narrator who has a secret but refuses to tell the reader what it is.

Other child(like) characters with secrets:

- Claude the dog goes off on his adventures when his owners are at work, so they never know what he’s been up to.

- The Secret Seven were called ‘secret’ because they never told their parents (or other children outside the club) exactly what went down in their crime-busting world.

- The storyteller character of Looking For Alaska by John Green keeps a secret from the reader and the structure of the book lets the reader know that we are counting down to a big reveal.

- Billy in Where The Red Fern Grows has a secret — he sneaks off to buy a puppy after saving up a lot of pocket money, even though his family needs it

Are secrets more common in chapter books (and up) than in picture books? It seems so, since it’s harder to find examples of picture book characters who keep secrets. Since toddlers and young children are completely reliant upon their caregivers, the degree to which child protagonists keep secrets will depend on the age of the ideal reader, with the deepest darkest secrets being kept by YA protagonists.

Klein offers a caution about secrets when crafting the plot:

The answer to the secret has to have a significance equal to the effort the reader has invested in it.

Examples From Contemporary Pop Culture

- Carrie Mathieson — from Homeland does underhanded things in her job in order to do her job well, gets herself fired and committed to a mental institution

- Sarah Manning — a mistress of disguise, often throws away the book in order to accomplish her goals

- Jessica Jones — a private investigator from the Marvel franchise

- The Doctor — Doctor Who

- Walter White — Breaking Bad. On the other hand, we can’t stand watching Marie because she tries to get away with petty theft and keeps failing miserably. This is excruciating to watch and makes us hate her not just for the immoral behaviour itself but for the fact she fails.

- Marty Byrde — Ozark — a Walter White inspired character.

- Newman — from Seinfeld

- Bart Simpson — is always getting into trouble at school and trying to get out of it

- Will — (Hugh Grant’s character) in About A Boy

- Tom Sawyer

- Jack in Titanic — Leonardo DiCaprio plays a rogue charmer hero

- The Usual Suspects

- Anansi Boys by Neil Gaiman

- Pirates of the Caribbean — Johnny Depp plays a rogue charmer

- Men In Black

- Ferris Bueller — Bueller, the hero of Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, tricks everyone so that he can have a relaxing day off school

- Silence of the Lambs — Hannibal Lecter is a trickster character who sets up a puzzle for Clarice to solve

- James Bond — a (good-looking) loveable rogue

- All of Eddie Murphy’s roles in his younger days, e.g. Beverly Hills Cop

- Villanelle from Killing Eve, and also Eve herself, who is her equal but on the other side of the law. Villanelle’s special super power is that she is a young, attractive woman and few people except that from such a character. She can shiv someone with a hair pin and get away with it. She can walk into a fancy party and look like she fits in.

There are many other subcategories of fictional tricksters. See the list at TV Tropes.

Tricksters In Children’s Stories

In children’s stories, the trickster and the underdog are the two main archetypes for heroes. Trickster heroes are more common in the highly entertaining (comedy) stories.

In picture books you’ll find tricksters in ‘carnivalesque‘ children’s stories. Tricksters upset normal hierarchies and rules of everyday or official behaviour, either through cleverness or foolishness. Oftentimes in picture books the trickster doesn’t get away with their plan because there’s a hole in it. Jon Klassen’s This Is Not My Hat is a good example. In picture books there’s also a moral issue whereby some adult consumers want to expose children only to upright, moral characters, and this means tricksters (liars, in other words) must be punished at the end. This comes through in consumer online review of books such as This Is Not My Hat.

Fairytales are full of tricksters. Some stock characters such as ogres are destined to be outwitted, always by a smaller, smarter hero. In fairytales, the trick is often a simple reversal. In Italian this is known as beffatore beffato (the cook gets cooked). Hansel and Gretel is an excellent and very literal example of that.

- The cook gets cooked

- The biter gets bit

Trickster tales are humorous stories in which the hero, either in human or animal form, outwits or foils a more powerful opponent through the use of trickery. Anansi the spider is a trickster figure in African folklore; Iktomi, which means spider, comes from the U.S. Plains Indians and is generally in human form; Coyote is a trickster figure from southwestern Native American folklore; and Raven is from the U.S. Pacific Northwest. Picture book examples are A Story, a story (1970), illustrated by Gail E. Haley; Iktomi and the Boulder (1988), illustrated by Paul Goble; Raven: A Trickster Tale from the Pacific Northwest (1993), illustrated by Gerald McDermott; Nail Soup (2007), illustrated by Paul Hess; and Mauri and the Big Fish (2003), illustrated by Frane Lessac.

A Picture Book Primer: Understanding and Using Picture Books By Denise I. Matulka

The Red Wolf by Margaret Shannon features a female picture book trickster. Although examples can always be found, across cultures, the female character is not normally the trickster.

TRICKSTERS IN STORIES FOR OLDER READERS

- The Tricksters by Margaret Mahy (clearly)

- Hannah’s Garden by Midori Snyder

- A Rumor of Gems by Ellen Steiber

- Deluge by Albertine Strong

- Chancers by Gerald Vizenor

- Coyote Blue by Christopher Moore

- Bone Game by Louis Owen

Tips For Writing A Good Trickster Character

- Tricksters have extreme confidence.

- They have a way with words.

- They are fun-loving. By seeming not to care about common morality (always) they teach the audience how to have fun in life.

- Deception is crucial. The more deception, the better the story.

- They are complete liars but we like to watch them in action so we do forgive them.

- The trickster might be the main character, but if not, they are the main character’s main opponent.

- Trickster opponents are very smart and have the ability to attack the hero, giving heroes a lot of grief.

There’s great psychological resistance to admit to being tricked, which is what pins many to their spot, long before it’s irrefutable. Opens up a huge can of worms related to family & social network, worldview. Gullibility (weakness, shame) & potential loss of investment.

@lavika

New Female Tricksters

As mentioned above, the original archetypal trickster is almost always gendered male.

Unfortunately, ironically, the male trickster is often coded as femme. Our fascination with tricksters reveals a dark side to our humanity.

[T]he major reason that plastic surgeries, gastric bypasses, and sex reassignments are all given similar sensationalistic treatments is because the subjects cross what is normally considered an impenetrable class boundary: from unattractive to beautiful, from fat to thin, and in the case of transsexuals, from male to female, or from female to male. […]

Coming face-to-face with an individual who has crossed class barriers of gender or attractiveness can help us recognize the extent to which our own biases, assumptions, and stereotypes create those class systems in the first place. But rather than question our own value judgments or notice the ways that we treat people differently based on their size, beauty, or gender, most of us reflexively react to these situations in a way that reinforces class boundaries: We focus on the presumed “artificiality” of the transformation the subject has undergone. Playing up the “artificial” aspects of the transformation process gives one the impression that the class barrier itself is “natural,” one that could not have been crossed if it were not for modern medical technology. Of course, it is true that plastic surgeries and sex reassignments are “artificial,” but then again so are the exercise bikes we work out on, the antiwrinkle moisturizers we smear on our faces, the dyes we use to color our hair, the clothes we buy to complement our figures, and the TV shows, movies, magazines, and billboards that bombard us with “ideal” images of gender, size, and beauty that set the standards that we try to live up to in the first place. The class systems based on attractiveness and gender are extraordinarily “artificial”—yet only those practices that seem to subvert those classes (rather than reaffirm them) are ever characterized as such.

Julia Serano, Whipping Girl

Very occasionally in folklore you’ll come across a female trickster:

- The seductive, deceptive foxes of Korea and Japan can be female. Note that ‘seduction‘ is a specifically feminine attribute that doesn’t seem to work for male tricksters in quite the same way, even though this Southeast Asian fox is seductive even when he is gendered male. This plays on the culturally dominant idea that men do the choosing, but if women want a part in choosing their own partners they must go about it in ‘underhanded’ ways (‘seduction’). In European tradition, the fox is gendered male — a handsome, smooth-talking knave.

- There’s a wise-cracking Baubo in Greek Eleusinian myth. The modern Crabby Road cartoons featuring the wise-cracking old woman who loves wine is a descendent of Baubo. (My mother and aunties often share them on social media.) This character is sometimes known as the burlesque witch.

- In African-American culture there is clever Aunt Nancy. In A Long Way From Chicago, Richard Peck creates a clever trickster grandmother who is a joy to read.

- The Hopi and Tewa Native American tribes feature a female coyote.

In children’s literature, Pippi Longstocking is the ‘tomboy’ equivalent of Tom Sawyer. (See also Anne Shirley and others.) These girl tricksters are very common in children’s stories being published today, as these characters have agency, and are therefore often referred to as ‘strong female characters’. Female tricksters are equally popular among adult readers, as Maria Tatar points out below. Notice also the extra burden heaped upon female tricksters compared to the original male version:

Stieg Larsson’s Millennium trilogy and Suzanne Collins’s Hunger Games series have given us female tricksters, women who are quick-witted, fleet-footed, and resolutely brave. Like their male counterparts—Coyote, Anansi, Raven, Rabbit, Hermes, Loki, and all those other mercurial survivors—these women are often famished (bulimic binges are their update on the mythical figure’s ravenous appetite), but also driven by mysterious cravings that make them appealingly enigmatic. Surrounded by predators, they quickly develop survival skills; they cross boundaries, challenge property rights, and outwit all who see them as easy prey. But, unlike their male analogues, they are not just cleverly resourceful and determined to survive. They’re also committed to social causes and political change.

Maria Tatar

I’m especially interested in the ‘surrounded by predators’ predicament of contemporary girl tricksters. This harks right back to the 17th century to The Harlot’s Progress story archetype, exemplified by a novel called Eveline.

In modern culture we now have:

- I Love Lucy

- Hyacinth Bucket — Hyacinth comes from a low income family and pretends to the world that she is a respectable upper-middle class lady. It’s a full-time job tricking other middle class people into thinking she’s from respectable roots.

- Roseanne — has a mischievousness about her

- Madonna — plays the part of a trickster in some of her music videos

- Rihanna — see the music video for “Bitch Better Have My Money” for instance

- Sarah — from Orphan Black shows us that she’s a trickster from the pilot, pretending to be her doppelganger in order to solve the mystery of her origin. A number of her clones are also trickster types, especially the soccer mom.

- Gabby — from Desperate Housewives is appealing because she’s constantly tricking her husband. This is a couple who are a constant state of oneupmanship. Roald Dahl’s Twits are this kind of couple, as are Vera and Jack Duckworth of Coronation Street.

- Nicolette Grant — is the trickiest housewife in the Hendrickson family, but following in her footsteps is Rhonda Volmer, for whom everything backfires terribly. The compound women in Big Love learn trickery as a survival measure — it’s the only power they get. The trickster characters are all punished, but punishment of death is reserved for a different character altogether.

There are a number of Rhonda Volmer archetypes in pop culture — they’re not usually the star of the story: teenage girls who present as sweet but who are liars and thieves. These girls are uniformly pretty, and like Rhonda they might be able to sing beautifully or something like that. They are often the opponent in a middle grade story, where the heroine is adorably straight-up, mostly lacking in guile. Ramona Quimby is lacking in guile, and her nemesis Susan is pretty but sly. This dynamic, set up by Beverly Cleary, has been repeated over and over in middle grade stories for and about girls.

Meanwhile, think of any female entertainer who is known as a ‘bitch’ and she probably has trickster attributes.

WHY SO FEW FEMALE TRICKSTERS?

- Most stories come from patriarchal cultures, where both hero and opponent are male.

- It’s possible (and very likely) that stories about female tricksters once existed but have since been lost because they haven’t been considered worthy of recording

- The female trickster may take a different form entirely, in which case we don’t consider her the female analogue of the same thing

- There might be something about the trickster archetype that cultures see as primarily male. In this case, even in a hypothetical matriarchal culture, the trickster would be gendered male.

I posit that voters have higher expectations of female politicians just as audiences have higher expectations of female tricksters. This has a very real effect upon who makes it into office. Hillary Clinton is often described as ‘wily’, for instance, whereas the same behaviours from a man would be considered ‘intelligent’.

One comic strip, considered ahead of its time in some ways, is the Nancy cartoons, recently rebooted. Though Nancy’s aunt was heavily sexualised by her original creator, Nancy was a bit of a standout heroine for her times because she has always been most definitely a trickster, with a dark, punitive side to her.

The Trickster As Story Genre

As well as referring to a character, the trickster is also a type of tale.

The Biter Bit

A subcategory of the trickster tale is the ‘biter bit’.

- Biter bit is an editorial term used to describe a story about aggression, in which the aggressor becomes the victim.

- The Biter Bit is an 1899 British short black-and-white silent comedy film featuring a boy playing a practical joke on a gardener by grasping his hose to stop the water flow and then letting go again when the gardener looks down it to check. (This gag is also used by Nancy in the Nancy cartoons.)

- A biter bit story is usually told from the point of view of the eventual victim, who throughout the major part of the story seems to be the perpetrator of the joke, swindle, etc.

- At the close of the story another biter-bit might begin, creating a circular plot.

- At the story’s close, both sides might find themselves undone by another party even shrewder than they are.

- The biter bit has two component parts:

- a fairly original situation in which one character is doing dirty on another

- an ingenious reversal whereby the dirt is done the doer.

- Probably about half of all jokes that do the rounds are biter-bit stories. Essentially, the biter-bit is an extended joke or anecdote. Just as in so many jokes, there is the non-malicious aggression and then the sudden setback for that aggressor. As in the joke, too, the story first sets up a taut situation and then explosively loosens it with an unexpected reversal. As with a successful joke, also, the good biter-bit must have a spark.

- A good biter-bit story rests entirely on how good the switch is.

- The morality of a biter bit is inherently conservative — people who seek to trick others get their own back.

- In children’s stories in particular, it is important to certain gatekeepers that children with ill-intent are punished.

Roald Dahl was a fan of the biter bit. The Twits is an extended biter bit comedy. Many of his short stories for adults end with a trickster getting tricked back.

Roald Dahl’s most famous biter-bit short stories were actually other people’s plots, executed well by Dahl. “Lamb To The Slaughter” is one. Dahl got his strongest plots from a less-remembered author called John Collier. See Collier’s short story “Back For Christmas” for a classic biter-bit plot. In my post, I go into how Collier sets it up perfectly.

Dahl, in turn was heavily influenced by other writers crafting biter bits. John Collier was one of them. See: “Back for Christmas“.

In movies, the 1980s film Dirty Rotten Scoundrels is another classic biter-bit plot. These days the horribly ableist ideology is evident, but I do remember watching that over and over as a kid. The movie remains a successful biter-bit plot, in part because we don’t expect a pretty, blonde woman to be a trickster herself. This is the exact same reason why Killing Eve is so successful in 2019.

By the way, who is the trickster in Road Runner? Wile E. Coyote has an ironically symbolic name — the road runner always ends up playing a better trick.

Further Reading

- Trickster Makes This World by Lewis Hyde

- Transformations of the Trickster by Helen Lock

- The Socially Aspiring Woman is a popular British archetype and part of the reason she works is because she is trying to trick those around her, and the mask always comes off, resulting in humiliation for her, and therefore comedy for the audience.

- Dr David Waldron, lecturer at Federation University, Australia, and folklore researcher gives an exclusive talk to The Folklore Podcast on the phenomenon of ghost hoaxing and guising in Victorian Times. How did figures such as Springheeled Jack come about. Why did people do this and how has it continued into our modern folklore?

- “Have I got a *wild* medieval story for you. A woman sleeps with someone in exchange for presents, and her husband gets mad. So she sets out to prove that her husband would ALSO allow a man to have sex with him in exchange for presents…” (#MedievalTwitter)

- Cleverness, a categorisation from Baughman’s Type and Motif Index of the Folktales of England and North America by Ernest Warren Baughman 1966

LOKI BY MELVIN BURGESS

In his new novel Loki (Pegasus Books, 2023), Melvin Burgess follows the antics of Norse mythology’s trickster god as he takes the reader on a wild ride through legendary stories about the founders of Asgard. Born from a fire inside the hollow of a tree trunk, Loki arrives in Asgard as an outsider. Despite his cleverness and wit (or, perhaps, because of them), Loki struggles to find his place among the old patriarchal gods of supernatural power. Loki is an amusing and relatable contemporary retelling of a classic Norse legend.

interview at New Books Network