How do you write a lengthy work — a book, a thesis — without giving up? Various writers share tips and tricks. Here are a collected few.

- Read Bird by Bird by Anne Lamott if you would like a more personal story with spiritual overtones.

- Read Making Ideas Happen by Scott Belsky if you prefer a more practical, analytical set of strategies.

RENAME “DRAFT ONE” TO SOMETHING ELSE

“Draft Zero” works, but I’ve seen “Sh!tty First Draft” and similar. The latter is a constant reminder that the first draft is not supposed to sound like published work.

Related: Draft numbering is an outdated way of thinking about revision.

DESIGNATE PROBLEMS AS “SECOND DRAFT ISSUES”

Dedicated writing software such as Scrivener comes in very handy here because Scrivener allows you to write notes in the Inspector window. Whenever you see something that needs fixing, make a note to yourself in the Notes section of the Inspector.

Alternatively, keep a separate document which is basically a to-do list of things to be fixed (or researched) later.

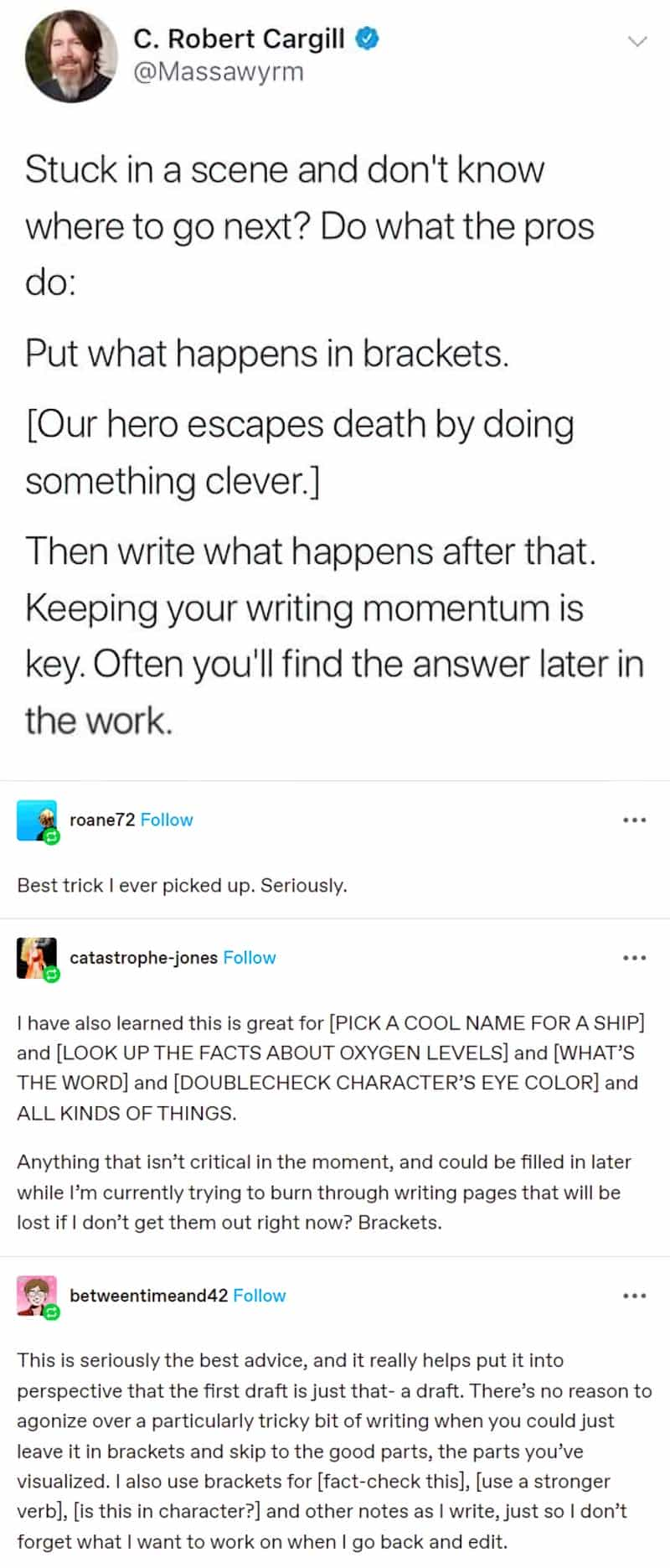

If you tend to get stuck down Internet rabbit holes when you look up something relatively simple, it’s a good idea to make use of a keyboard symbol like square brackets, which can easily be searched in the document later:

At 3pm [check character would be able to get to the restaurant from Ned’s house by this time] she arrived at Nandos.

The waitress looked familiar. After ordering a coffee, finally it hit her. [Character Name] from high school.

ASK “HOW ACCURATE DOES THIS WORK NEED TO BE?”

Speaking of research, if you are a fan of mimesis you can get to a point where you are frustrated that you can’t be more “accurate” (historically, factually) and this can cause a block. Not every writer will relate to this, but if you are someone who gets to that point, go back to your broad themes and ask what function you hope your novel to achieve.

There’s always the danger of fetishizing one’s research, becoming obsessed with a little archival gewgaw one has found, and then starting to write just to create a display case for it. I dislike novels that feel like show-and-tell. And although I don’t want to make egregious mistakes and am terrified of anachronisms and inconsistencies, I’m not obsessed with referential accuracy. That’s absolutely not a primary concern for me. To me, archival work has to be in the service of imagination. Instead of becoming a factual straightjacket, research has to open up your vista and let you imagine things that were unimaginable before.

Hernan Diaz, author of Trust

PRACTISE MENTAL CROP ROTATION

Another common piece of advice issued to writers: Write every day. For some, this works. It works for Stephen King, who famously writes 2000 words every day while he’s working on a manuscript.

But for others this doesn’t work at all. Some people need to plant seeds, step away and let the seeds do their work. (This idea is explored by Arnold Lobel in a Frog and Toad story.)

WRITE THE PART YOU WANT; SKIP THE REST

If you don’t want to write it, readers probably don’t want to read it. The exception is: Parts of a story which are difficult to write but which must be written anyway. Don’t skip:

- The climactic scenes (it’s tempting to skip these)

- Making your beloved character’s life difficult

MAKE USE OF SQUARE BRACKETS

And I cannot emphasise this enough: Make sure you use square brackets for this purpose.

GENERAL INSPIRATION

If there’s a book that you want to read, but it hasn’t been written yet, then you must write it.

Toni Morrison