“Trespasses” is a short story by Canadian author Alice Munro, included in the collection Runaway, published 2006.

This piece might challenge everything you’ve learned about how to structure a story. All the parts are there, but not as you’d expect. If Alice Munro had anonymously joined one of my writing critique groups over the years, she may well have been offered the following notes:

- This is superbly written and achieves astounding psychological insight, but who is your main character here?

- Perhaps you’ve started in the wrong place with two sections of throat clearing? The real story is that of Lauren, so why not maintain focalisation of Lauren throughout the entire piece?

- What’s the point of the restaurant scene? We never see the old married couple again. All the more reason to nix the first few sections?

- I find it hard to believe a ten-year-old is allowed that much freedom.

Okay, honestly, if someone in one of my writing groups had uploaded “Trespasses”, they may have even received those notes from me. And this is why it’s so hard to offer critique on literary short stories — the form is deliberately experimental. Is anything ever wrong? Well, yes, of course. Except these ‘wrong’ things are so very specific to any single story we can’t fall back on guidelines. This is why some writers have learned to hate guidelines (or ‘rules’) altogether. (I’m not in that camp.)

That’s because in “Trespasses”, as in all of Munro’s work, there is an explainable reason for all narrative choices. It’s just, putting these reasons into words is so hard. If we can articulate what Munro’s doing here, we can bring more nuance to the ‘writing guidelines’ we have learned.

To that end, I recommend the following paper: ‘Who Was It If It Wasn’t Me?’: The Problem of Orientation in Alice Munro ‘s ‘Trespasses’: A Cognitive Ecological Analysis by Nancy Easterlin, who does an excellent job of putting Munro’s unusual narrative decisions into words, with the overall message that Munro is deliberately disorienting the reader.

Why would any writer want to do that? Let’s investigate.

THE OLD AND NEW MEANINGS OF TRESPASS

Despite attending a Presbyterian church, I was required to memorise the version of the Lord’s Prayer with ‘trespasses’ rather than ‘debts’.

And forgive us our trespasses, as we forgive those who trespass against us…

I didn’t understand the archaic meaning of ‘trespass’. I’d only ever seen the word on signs. I grew up in semi-rural New Zealand — these signs were always affixed to farm gates and I knew I hadn’t been walking around on farms, so as far as I was concerned, I was sweet. I also couldn’t fathom what was so very wrong about setting foot on private property — surely there were worse sins? Maybe someone’s just taking a quiet short cut…

I now have a handle on the wider meaning of ‘trespass’, but the word is so closely linked to Christianity that as I delve into Munro’s short story the words of the Lord’s prayer are forefront in my mind. Signage aside, I rarely hear the word ‘trespass’ in everyday English.

“Trespasses” by Alice Munro will likely be a story about ‘sin’. (What story isn’t, though?) This is also a story about ‘overstepping boundaries’, making it more in line with the modern definition of ‘trespassing’ we see on signage.

The story “Trespasses” encouraged me to consider the following:

- How might one kind of trespass (within a family) make a person vulnerable to a trespass from an outsider?

- What is the difference between loving someone and trespassing upon them? Might love commonly co-exist with trespassing?

- Can the truth be more damaging than fiction? What if the fiction is later found out? Is the damage then simply postponed?

- Can too much information make a child vulnerable? Surely too little information is also bad. Where’s that line?

PLOT OVERVIEW

Eileen and Harry and their daughter Lauren [EVENTUAL MAIN CHARACTER] have recently moved to a small town where Harry has bought the town’s newspaper. While unpacking, Lauren asks about the contents of a box that seems particularly light [MYSTERY], and her father gives her the first version of some past events. [STORY WITHIN A STORY] Eleven years before, he and Eileen had a baby, soon after which Eileen learned that she was pregnant. After a fight, Eileen drove off with the infant and had an accident in which the baby was killed. The box contains the baby’s ashes. This is just the beginning of Munro’s story, however. [MANY SHORT STORY WRITERS WOULD END THE STORY HERE, AT LAUREN’S DISCOVERY.] Another woman, Delphine [MINOTAUR OPPONENT], who believes she is the biological mother of the first (presumably illegally adopted) baby, has tracked them down [ OPPONENT’S PLAN]; she also assumes that the living girl Lauren (both babies were named Lauren) is her daughter and pursues a relationship with the girl. As Lauren gradually begins to suspect, based on Delphine’s hints and indirect revelations, that she might be adopted, Harry and Eileen learn of the friendship that has emerged between the two. The result [BIG STRUGGLE] is the late-night attempt to provide the canonical narrative of the past events and the hasty, long-delayed ceremony to scatter the ashes of the baby who died a decade before.

‘Who Was It If It Wasn’t Me?’: The Problem of Orientation in Alice Munro’s ‘Trespasses’: A Cognitive Ecological Analysis

CHARACTERS OF “TRESPASSES”

Harry

Eileen’s husband and Lauren’s father. Used to work at a news magazine but quit his job after burning out. Has come to this new town having bought the local paper. He remembers this town from his childhood. For Harry, this is a home-away-home children’s story, underscoring his boyish nature. (Though he is revealed to be far more dangerous than any little boy.) “A broad-faced, boyish-looking man with a tanned skin and shining light-brown hair. His glow of well-being and general appreciation spread around the table…’

Eileen

Harry’s wife and Lauren’s mother. Much thinner than the local women in this small country town, marking her out as a sophisticate from the city. (Munro tends to describe characters’ BMI as something meaningful.) Eileen makes coffee each morning, takes it back to bed and drinks it slowly. Eileen works in her husband’s newspaper office (so she can never really get away from him). She wears ‘casually provocative outfits’. She is beautiful. ‘Her manner in the newspaper office was crisp and her expression remote, but this was broken by strategic, vivid smiles’. Eileen is a capable woman who prefers to do things like sanding and wallpapering on her own, without help from family. She is an isolated, self-contained person. Emotional isolation is perhaps a protective thing.

Delphine

We meet Delphine early in the story but are encouraged to mostly forget about her. At first I thought she might be the family dog, or some smaller animal sitting in a cage on the front seat. The story opens with someone (or something) called Delphine sitting in the front of the car with Harry. It takes a while before Alice Munro lets us know who Delphine is. This is part of Munro’s deliberate disorientation. Eventually we learn Delphine is the name of the woman who works in the restaurant. Interestingly, the name ‘Delphine’ and ‘the woman who works in the restaurant’ are only subsequently connected. Not many writers would hold off connecting the woman and the name. Munro also uses this trick in “Save The Reaper“, in which it takes the reader a while to realise two women are mother and daughter. This is so the reader can experience these two women as friends, which is the kind of relationship the mother in that story wants; in contrast, the daughter wants a mother who behaves like a mother. Using this trick, Munro lets the reader know how it feels to have a mother who behaves as a friend by tricking us into thinking the two women are simply friends.

When we do properly meet Delphine in “Trespasses”, Munro introduces her to us via Lauren’s eyes:

She had long fine hair that might be whitish blond or might be really white, because she was not young. She must often have to shake that hair back out of her face, as she did now. Her eyes, behind dark-rimmed glasses, were hooded by purple lids. Her face was broad, like her body, pale and smooth. But there was nothing indolent about her. Her eyes, now lifted, were a light flat blue, and she looked from one girl to another as if no contemptible behaviour of theirs would surprise her.

It’s a dump. Delphine said things like that. She spoke vehemently — she did not discuss but stated, and her judgments were severe and capricious. She spoke about herself — her tastes, her physical workings — as about a monumental mystery, something unique and final.

She had an allergy to beets. [UNEXPECTED DETAIL IN FICTION] If even a drop of beet juice made its way down her throat, her tissues would swell up and she would have to go to the hospital, she would need an emergency operation so that she could breathe.

She believed a woman should keep her hands nice, no matter what kind of work she had to do. She liked to wear inky-blue or plum fingernail polish. And she liked to wear earrings, big and clattery ones, even at her work. She had no use for the little button kind.

She was not afraid of snakes, but she had a weird feeling about cats. She thought that a cat must have come and lain on top of her when she was a baby, being attracted to the smell of milk.

Why does Alice Munro choose these details to describe Delphine? First, they are being filtered via a ten-year-old, and kids pick up on oddities. What have cats and snakes got to do with anything? We might also go the symbolic route — Delphine is the ‘snake in the grass’, sneaking up on this family, meaning to set up an unwanted relationship. But more importantly, I feel, Delphine is established as a woman whose mind goes to strange places. It is a fantasy that she doesn’t like cats because of an incident she couldn’t possibly remember, and almost certainly didn’t happen. This is the moment I don’t quite trust Delphine. This must also be the moment Lauren doesn’t trust her, either.

Lauren

Lauren is ten years old, her exact age calculated only after her father explains the past. Until that point I thought Lauren was a few years older than that. She is given a lot more freedom than typical contemporary ten-year-olds (though this story is at least 15 years old). Lauren’s love of sugary foods marks her out as a child, though. Lauren makes her own breakfast, usually cereal with maple syrup instead of milk. Lauren is lonely at school. This much is explained by the narrator. It’s a complex situation, so the narrator steps in to describe the nuance:

Her isolation at school was based on knowledge and experience, which, as she half knew, could look like innocence and priggishness. The things that were wicked mysteries to others were not so to her and she did not know how to pretend about them. And that was what separated her, just as much as knowing her to pronounce L’Anse aux meadows and having read The Lord of the Rings. She had drunk half a bottle of beer when she was five and puffed on a joint when she was six, though she had not liked either one. She sometimes had a little wine at dinner, and she liked that all right. She knew about oral sex and all methods of birth control an what homosexuals did. She had regularly seen Harry and Eileen naked, also a party of their friends naked around a campfire in the woods. On that same holiday she had sneaked out with other children to watch fathers slipping by sly agreement into the tents of mothers who were not their wives. One of the boys had suggested sex to her and she had agreed, but he could not make any progress and they became cross with each other and later she hated the sight of him.

Lauren is thereby established as dangerously ‘precocious’ (not a word I like), and at this point I expect the worst for her. Fortunately, Lauren is still young enough to blurt everything out to her mother when things feel really bad, and I figure this is why Munro made Lauren ten and not, say, thirteen. (In stories, perhaps as in real life, a thirteen year old’s trouble is more likely to be discovered by a caring adult rather than the child breaking down and telling all.)

The Dead Lauren

The deceased baby forms the ‘ghost‘ (a.k.a. psychic wound) of Harry and Eileen and of Lauren, too. This baby was killed in a car accident due to not being strapped in properly. Eileen was pregnant with a new baby at the time (Lauren the Second).

How would it feel to find out your parents had a baby before they had you, and this baby was called the same name? I might start imagining a completely other life for myself — one in which the other Lauren had lived and I had died. Munro’s plot is an interesting, slightly complicated set up but I’ve seen similar in real life — parents have years of difficulty in conceiving a baby, go through the lengthy faff of the adoption process, adopt a baby, then immediately find themselves pregnant. Something about being around a baby seems to influence fertility rates, at least anecdotally:

One theory floating around is that women who are around babies somehow experience improved fertility. […]

“There is zero evidence of this, other than anecdotes,” Dr. Paula Amato, Oregon Health & Science University School of Medicine associate professor of obstetrics and gynaecology, told Healthline.

Healthline

SETTING OF “TRESPASSES”

SEASON

The framing story, in which a family disposes of ashes, begins a few weeks before Christmas, which in Canada is winter. Something is coming to an end.

- ‘The sky was clear and the snow had slid off the trees but had not melted underneath them or on the rocks that jutted out beside the road.’

- ‘black lacy cedars’ (putting me in mind of a Tim Burton movie)

- ‘There was a slight crackle to the snow, though the ground underneath was soft and mucky’ (suggesting an snail under the leaf setting). This sort of sentence can be described as ‘multivalent’, meaning it can be interpreted as both literal and metaphorical. Multivalent = having many applications, interpretations, meanings, or values. There is plenty of multivalent detail throughout Munro’s fiction.

THE TOWN

- Harry’s family used to have a summer place on one of the lakes around here. There is a hotel on the main street. This hotel no longer has a liquor licence.

- A Victorian mansion, now a nursing home (Gothic overtones)

- a brick tower which used to be a broom factory

- the graveyard going back to 1842.

- a fair in fall, suggesting a Gilmore girls type utopia

THE HOTEL

He pointed out things in the dining room that were just the same — the high ceiling, the slowly rotating fan, even a murky oil painting showing a hunting dog with a rusty-feathered bird in its mouth.

The hotel serves canned green beans even though it is fresh bean season. This is another example of a unexpected detail — perhaps it is noticed for its irony. Where else in this story is irony at work?

The unwelcoming Mr Palagian and his hotel are inextricably linked — juxtaposed against each other by the unwelcoming owner versus his sign which reads ‘WELCOME’. More irony.

There is also an ironic gap between the narrator’s delightful chatter and the grim story of the dead Lauren underneath. What makes the narrator seem delightful and chatty? That’d be the ‘incidental nature’ of the discourse, cue those strange details — like your best friend chatting to you over coffee, each new recollection prompting a related, delightful and interesting one.

I’m reminded of the following meme, which is not at all how a writer plots. Instead, Munro’s narrator achieves the illusion of a ‘chatty’ storyteller, because that’s what ‘chatty’ means, right? Someone who is never short of the next thing to say, because one thing segues effortlessly into another thing:

See also

THE HOUSE

The word ‘liminal‘ seems apt here. The ‘vacationland wilderness’ is, functionally, a heterotopia:

They had rented a house at the edge of town. Just beyond their backyard began a vacationland wilderness of rocky knobs and granite slopes, cedar bogs, small lakes, and a transitional forest of poplars, soft maples, tamarack, and spruce. Harry loved it. He said they might wake up one morning and look out at a moose in the backyard. Lauren came home after school when the sun was already getting low in the sky and the middling warmth of the autumn day was turning out to be a fraud [SHE KNOWS IT’S A SNAIL UNDER THE LEAF SETTING]. The house was chilly and smelled of last night’s dinner, of stale coffee grounds and the garbage, which it was her job to take out.

Harry’s view of the forest is utopian, but as any reader knows, a story featuring a house situated on the edge of the woods is imperilled. At best, the forest is the family’s dark subconscious. They’re about to go there — right into the deepest, darkest Jungian parts of it. When it comes to houses, the basement is the psychological equivalent of the forest. Notice how Eileen wants to send Harry down to the basement of their rented house, along with all his possessions, including their box of ashes.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “TRESPASSES”

The thirty-seven-page story is told in seventeen sections that vary in length from under a page to about six pages. It starts with a section covering the first part of the final scene [FRAMING TECHNIQUE], the four characters finding a site on a riverbank to scatter the ashes, and ends with the rest of the scene, the scattering of ashes and the beginning of the ride back into town. On one level, then, the present event of dispersing the ashes functions conventionally as a narrative frame. However, Munro develops this overt structural circularity on more subtle chronological and psychological levels, since the town is a place of childhood vacations for Harry, and since each adult character, through unacknowledged feelings of guilt, responsibility, and desire deviates from but ultimately returns to his or her version of the past events. The story thus enacts a debased version of the myth of eternal return, wherein the structural return to the oozy riverbank reflects the return of each of the adult characters to his or her muddy version of the baby’s adoption and death.

Who Was It If It Wasn’t Me?’: The Problem of Orientation in Alice Munro’s ‘Trespasses’: A Cognitive Ecological Analysis

THE MYTH OF ETERNAL RETURN

What is ‘the myth of eternal return’? Children’s stories in particular tend to contain the soothing message that no matter what happens out in the world, you can always return home to safety. Harry himself has returned to a childhood utopian setting of his — he genuinely believes this ideology.

I put it to you that this is why Alice Munro has chosen a ten-year-old as main character — books for Lauren’s age group are all about the safe return home, or finding a new and safer home.

But reality differs from children’s books. For so many people — children included, Lauren as one example — home is not safe at all. Unlike the storybooks tell her, Lauren’s home is not homely.

NARRATION

As well as structurally, Munro’s chosen style of narration underscores the theme, of ‘what is really true’?

One theme of “Trespasses,” as of much of Munro’s longer fiction, is the difficulty of establishing authoritative narrative accounts.

Who Was It If It Wasn’t Me?’: The Problem of Orientation in Alice Munro’s ‘Trespasses’: A Cognitive Ecological Analysis

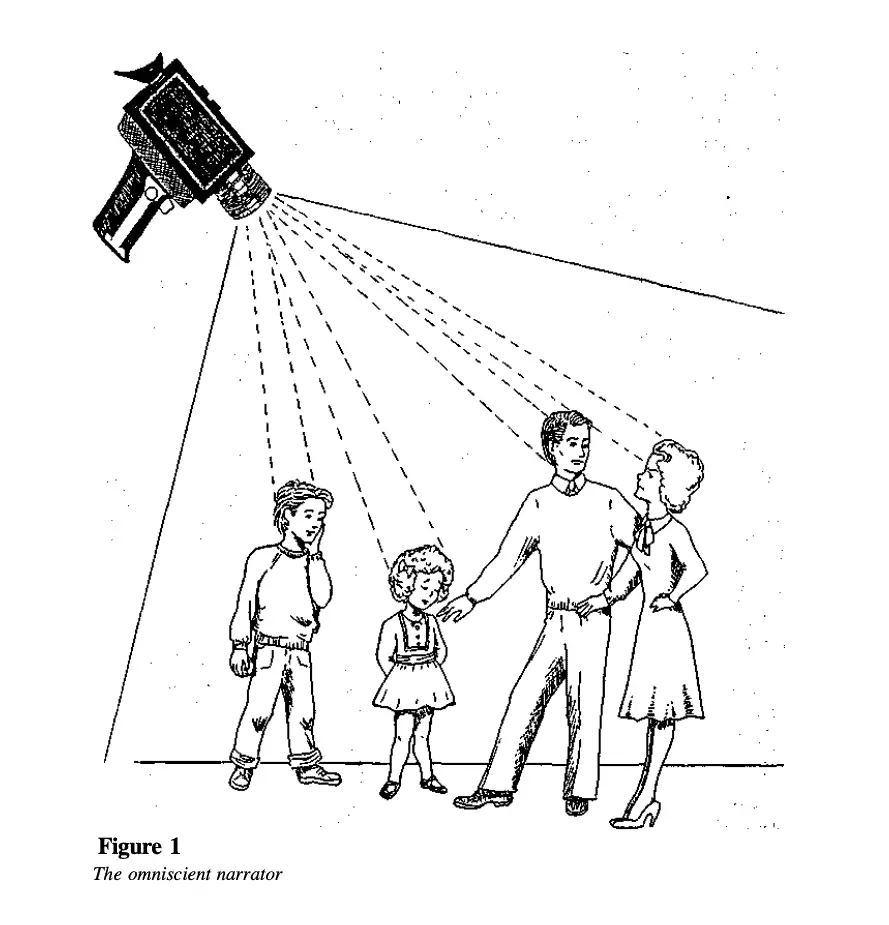

Alice Munro has chosen a roving camera for this story, which opens with an unseen narrator. Who is this person? It feels like Alice Munro herself, but that’d be a mistake. (Narrators are not authors.)

Munro orchestrates this process of deception at the level of narrative technique, employing an ostensibly reliable narrator who, beguiling readers with her intelligence and charm, surveys the narrative world and delivers a comic, apparently loosely connected, and superficial account of events. In this manner, Munro compels readers to stand quite outside the narrative world for the first five pages, in alliance with the narrator and without any hint that there will be an orienting perspective among the characters.

Who Was It If It Wasn’t Me?’: The Problem of Orientation in Alice Munro’s ‘Trespasses’: A Cognitive Ecological Analysis

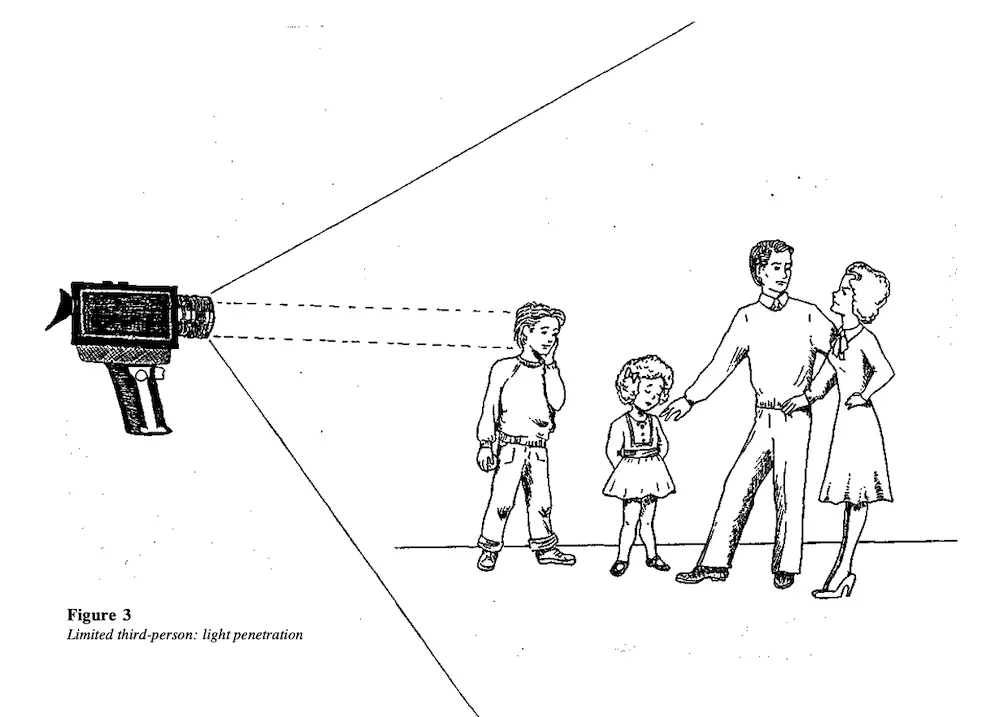

If we imagine a film, the camera zooms in to sit on Harry’s shoulder, then shifts to Lauren’s.

To borrow terms and (creepily heteronormative) illustrations from Characters and Viewpoint by Orson Scott Card (milkshake duck), “Trespasses” begins like this:

… and gradually moves into this, in which the boy below is first Harry, next Lauren:

SHORTCOMING

THE PARENTS’ WEAKNESS

At first “Trespasses” looks like it’s going to be about the character of Mr Palagian, told by a storyteller narrator, much like The Great Gatsby. But this is not about Mr Palagian at all.

Why does Munro do this?? Alice, are you messing with us?

In “Trespasses,” Munro’s circuitous delineation of the ambiguity surrounding events and the evasions that sustain those ambiguities are a product of her delayed introduction of the main character (and thus the orienting consciousness), a delay that confounds the reader’s ability to prioritise and evaluate incidents and information, and so to determine narrative relevance. Typically, readers approach literature under the assumption that the author will provide a speaker, a narrator, or a character to serve as a central point of reference, focusing emotional-cognitive effort in the literary environment and, in consequence, motivating and guiding reasoning processes in the direction of constructing and sustaining narrative order. This is, in some respects, a matter of convention… the reader’s commitment to character functions is the imaginative equivalent of a real-world self, and its absence can deprive the reader of a vantage point for seeing, cognising, and acting. Thus, when Munro intentionally withholds her main character’s identity for the first six pages of “Trespasses,” she deprives her readers of the point of orientation (the character function) that will prompt for and facilitate narrative construction. Munro’s goal in thus disabling event- and fact-based narrativity is to fully reveal the psychologically disabling conditions of that main character’s life and the ethically troubling domain of her upbringing.

‘Who Was It If It Wasn’t Me?’: The Problem of Orientation in Alice Munro’s ‘Trespasses’: A Cognitive Ecological Analysis

Here’s what I get out of that: Munro is making the reader disoriented about who the important people are because that’s how Lauren feels, too, not about a story, but about her actual life.

Munro’s delayed revelation of the story’s main character in combination with conventional features of narrative presents readers with a territory devoid of its true and necessary focalizing perspective, that of the ten-year-old Lauren. Meanwhile, Munro effectively provides the narrator as an alternative (though ultimately false) other “self” with whom readers identify. Thus standing on the perimeter of the setting rather than entering actively into it, readers are deprived of crucial information by orientational disadvantage and immobility.

‘Who Was It If It Wasn’t Me?’: The Problem of Orientation in Alice Munro’s ‘Trespasses’: A Cognitive Ecological Analysis

Back to Mr Palagian for a minute. Here’s the description of Mr Palagian, as filtered to the reader via Harry. I mean, Harry is a writer, so he’s a natural fit as the character chosen to (indirectly) narrate someone else’s life:

Someone like Mr Palagian—or even that fat tough-talking waitress, he said—could be harboring a contemporary tragedy or adventure which would make a best seller.

The thing about life, Harry had told Lauren, was to live in the world with interest. To keep your eyes open and see the possibilities—see the humanity—in everybody you met. To be aware. If he had anything at all to teach her it was that. Be aware.

But this description of Mr Palagian is not even about Mr Palagian. ‘What Sally says about Susie says more about Sally.’ This description is about Harry. We learn that Harry’s shortcoming is as follows:

Harry is so interested in people as possible fictional inspiration that he’s not going to see what’s going on in the real world, with his very own daughter. His shortcoming is misplaced focus due to literary pretensions. He likes to tell Lauren things as her father and mentor. It is ironic that as he instructs Lauren to ‘be aware’, he fails to achieve genuine awareness himself. Something in this story is going to surprise him. Of that we can be sure. Later it bears out:

Harry was not as angry as Eileen [about Delphine].

“She seemed a perfectly okay person anytime I talked to her,” he said. “She never said anything like this to me.”

Eileen is equally preoccupied with superficial appearances. We see this in her observation of the family in the hotel dining room — she wonders how they could get so fat. She has no comment about the misogynistic joke that comes out of the old man. What’s the point of the anniversary celebration? At first it seems disconnected from the rest. First, it has allowed us to know more about Eileen and Harry and their superficial, middle-class shock (at the green beans and the fatness). Second, it introduces the theme of violence within marriage. Eileen and Harry cannot hear the old man’s joke as a joke; we learn later that violence between husband and wife is far too close to home.

I don’t find Harry an empathetic character. I find him quietly dangerous. Harry describes Eileen as ‘hysterical’, and talks to their daughter about her dead older sister without Eileen’s knowledge and consent. A father tells his daughter something in confidence, encouraging secrets within the family. Emotional incest. Some people feel the phrase ’emotional’ incest devalues the word ‘incest’ but whatever we call it, this relationship within a family a real and icky phenomenon:

Emotional incest is not sexual. Instead, this type of unhealthy emotional interaction blurs the boundaries between adult and child in a way that is psychologically inappropriate. When a parent looks to their child for emotional support or treats them more like a partner than a child, it is considered emotional or “covert” incest. The outcome of this family structure often produces similar results — on a lesser scale — as sexual incest.

Psych Central

LAUREN’S WEAKNESS

Ironically, Harry and Eileen have brought Lauren up thinking that if she is exposed to all the worldly knowledge, the knowledge itself will protect her. Unfortunately, it’s this knowledge, and the experience of living with hipster, free-loving parents, which marks her out as more mature (faux-mature?) than her peers, and serves to isolate her from them.

“Trespasses” is one of several Munro stories in which the central character is an adolescent girl whose parents and their associates live by a lingering set of counter-cultural attitudes, which include a mild anti-establishment posture and a belief that children should be treated as adults. While the parents are deluded in their sense of superior honesty and freedom from conventional mores (they seem as repressive, viciously passive aggressive, and jealous as any of the usual human lot), these attitudes help them evade the moral and ethical consequences of their actions.

‘Who Was It If It Wasn’t Me?’: The Problem of Orientation in Alice Munro’s ‘Trespasses’: A Cognitive Ecological Analysis

And isolation is itself supremely dangerous. In her early teenage years Lauren is the lonely new girl in town, seeking friendship outside the home as well as emotional distance from her own parents. As the story opens, Lauren is presented as dangerously vulnerable to the advances of a sexual predator.

DESIRE

HARRY’S DESIRE

Harry is clearly after a new start in a new town, where he can rebuild his social capital by being important at the newspaper and perhaps find time on the side to write a novel, using local personalities as inspirational fodder. Harry is recovering from some mental health issues himself, having faced ‘burn out’ at his previous job. (We don’t know exactly what this means — ‘burn out’ is a conversational term and could be major or code for something else.)

Lauren is finding her place in the world as a young teenager and craves genuine connection with equals. This is more of a psychological need which leads directly to her Desire. (Shortcoming and Desire are very much interconnected.)

Here’s why Alice Munro’s stories are famous for being psychologically complex. Sentences like the following:

It wasn’t possible to tell the whole truth because she couldn’t get it straight herself. She couldn’t explain what she had wanted, right up to the point of not wanting it at all.

OPPONENT

Alice Munro sets up a family in opposition to each other. It’s more about what she doesn’t show than what she does: We don’t see Lauren and Eileen interacting much at all until Lauren’s confession that she’s been seeing Delphine. It’s as if Lauren Number Two is a ghost to Eileen. Eileen is mostly emotional unavailable. Perhaps she has withdrawn from her daughter, opening up the gap for the father to come in and overfill it. However, this changes towards the end.

The other opposition comes from outside the family. Who is standing in the way of Lauren finding genuine friendship? The woman who isolates Lauren from her peers, pretends to be her friend, then reveals herself to be a kind of predator.

Alice Munro at first led me to think Delphine might be a sexual predator. She seems to keep that as a reveal at about midpoint. This is what I’m thinking as Lauren learns it, up in Delphine’s attic bedroom. Perhaps this is why Munro’s narration first lets us into Harry’s head; along with Harry, we become wary of Mr Palagian instead — that old magician’s trick of misplaced focus. Or, ‘disorientation’.

There are story-external factors encouraging the reader along this line of thought — namely, the real world statistics on gender and sexual predators. A sex offender is simply more likely to be gendered male. When we think ‘sex offender’ we think of a man: a man like Mr Palagian, perhaps — uncannily foreign (intersecting with xenophobia), gruff, lacking in social graces.

Unfortunately, the most dangerous predators have very good social skills. Poor social skills make one an equally poor predator.

Delphine knows exactly how to win Lauren over. But again, I have been fooled. Delphine is not a sexual predator but with completely different intentions — she wants a connection with the girl she believes to be her adopted daughter.

PLAN

DELPHINE

Delphine’s plan, at first appears as following: to coax an attractive, vulnerable underage girl to her bedroom where she will see what she can get away with.

But my focus was (deliberately?) misplaced. Delphine is not a pedophile. She is a troubled woman and grieving mother. Her plan is to move to Harry and Eileen’s town and strike up a connection with her daughter.

LAUREN’S PLAN

Without a plan of her own, Lauren goes along with Delphine’s pla.. Lauren is only ten, so she is reactive rather than proactive. Except in fantasy and in children’s literature, ten-year-olds don’t tend to rescue themselves from adult opposition.

People respond in unexpected ways to trauma. Lauren is scared by Delphine, a trauma which follows her all the way home. Once home, she decides to eat — not because she is hungry but because she is trying to expunge something horrible. The symbolism of the whiteness outside feels like a type of cleansing:

The felling in her stomach was of both a swelling and a hollow. It seemed as if she might get rid of that just by eating the right sort of food, so when she got into the house she went straight to the kitchen cupboard and poured herself a bowl of the familiar breakfast cereal. There was no maple syrup left, but she found some corn syrup. She stood in the cold kitchen, eating without even having taken her boots and her outdoor clothing off, and looking out at the freshly whitened backyard. Snow made things visible, even with the kitchen light on. She saw herself refelcted against the background of snowy yard and dark rocks capped with white, and evergreen branches drooping already under their white load.

This paragraph reminds me of the ancient tradition of ‘sin eating’ in which the sins of the recently dead were transferred to a village person who, for a fee, consumed food & drink handed to them over the coffin. This sin-eater would be shunned by their village, much like lepers were. Mourners would pay the designated sin-eater to rid their departed loved ones from all their sins. The sin-eater would then perform a ritual. This would allow the dead person to enter Heaven without sin-free. I wonder if the sin-eaters really did believe they would be forever damned in hell after they themselves died. Apart from societal shunning, it doesn’t sound like a bad gig in a starvation economy — sin-eaters received both food and payment.

One well-known account of sin-eating goes like this:

The corpse being taken out of the house, and laid on a bier, a loaf of bread was given to the sin-eater over the corpse, also a maga-bowl of maple, full of beer. These consumed, a fee of sixpence was given for…taking upon himself the sins of the deceased.

Enacademic

(Does anyone know what a maga-bowl is? If so, I’m interested.)

I wonder if Alice Munro encountered this account. I’m aware that in Canada maple syrup is a pantry staple, in which case Lauren’s penchant for maple syrup could be symbolically unloaded, but might the maple syrup be doing double (‘multivalent’) duty — an intertextual reference to the ‘maga-bowl of maple’ described above?

In any case, Lauren’s attempt at sin-eating don’t work. She throws the food back up.

BIG STRUGGLE

Lauren faces two main scary moments and the reader is right there with her:

- In Delphine’s room

- At her own house, as her parents get drunk and fight

There is nowhere Lauren feels safe.

ANAGNORISIS

Sure enough, The Lord’s Prayer has been the thematic backbone of this short story. I have this confirmed when Eileen says “Our Father which art in Heaven—”

Eileen seems to have had a Anagnorisis about her family — she knows that she can’t create a homely environment for Lauren so she’ll be better off at boarding school. Harry never realises that. He will continue in his delusion that he has found the perfect home in this little town where he owns the newspaper and they live in an idyllic little house on the edge of a vacationland wilderness.

But still, um, is this story really finished? For real?

Munro not only strains readers’ desire for narrative closure by providing information that seems incidental (apparently useless) at the outset but forestalls readers’ ability to begin sorting information and thus shaping the narrative by refusing to establish an orienting perspective within the setting. In rendering problematical the truth that readers are cognitively predisposed to pursue—initially, a factual account of past events and their connection to the present—Munro redirects attention to the self-justifications of her characters and the implications of their stories for the submerged main character, Lauren, and her potentially focalizing perspective. The story of her life, in fact, is one of a faltering, or long-deferred, orientation—in other words, of an unrealized because unrecognized self.

Who Was It If It Wasn’t Me?’: The Problem of Orientation in Alice Munro’s ‘Trespasses’: A Cognitive Ecological Analysis

In other words:

- Lauren doesn’t get the straight truth about herself, so dear reader, don’t think you can have it told to you straight, either. This is how it feels, see?

- Lauren does have a bunch of other information, about life in general. But that info isn’t exactly helping her out. I mean, she’s only ten.

NEW SITUATION

She was so sick of these burrs that she wanted to beat her hands and yell out loud, but she knew that the only thing she could do was just sit and wait.

Surely the burrs, too, are multivalent. We have burrs in our yard and the dog collects them. Here’s the thing about burrs: If you don’t get rid of them they bury their way right into your skin and cause a lot of pain. They can even get infected. Symbolically, a burr could stand for anything that works like that. Perhaps in this story the burrs symbolise the little bits of information Lauren gathers as she grows up.

Ultimately, since a ten-year-old doesn’t have much agency, what else can Lauren do but sit and wait out her childhood, until she can be free of these parents?

We don’t see this happen on the page, but we extrapolate that Lauren will be sent away to a boarding school. I imagine a Sally Draper future for Lauren, followed by a clean break from her ageing parents.

Header photo by Patrick Tomasso