Why are trains so useful to storytellers? In stories, trains play a functional role, getting your characters from one place to another. But there’s more to trains than that. Perhaps we encounter storytellers on trains more than in any other place.

A Brief History of Trains

Before understanding what trains have come to symbolise, it helps to understand the history.

WHEN WAS THE FIRST TRAIN?

This is impossible to say, because it depends what we mean by “train”. We might talk about wagon ways”, which ran on tracks from mines to nearby rivers. These did not have steam propulsion, so are not often counted.

Steam trains were a key invention of the 19th century and steam transportation changed the world.

Steam propulsion began around 1830 with a train between Liverpool and Manchester in England. This marked the beginning of the new era. This line was a marked advancement on what came before because this train ran on double tracks and linked two cities.

But no one in 1830 knew the significance of this new train back in 1830.

Across the ocean, also in 1830, the Baltimore to Ohio train changed things forever in America.

The typical starting length of a train track in this era was 10-15 miles. But within a single decade, these very short starting tracks had expanded into railroad networks.

First trains transported minerals, then other goods, then passengers.

India was about a decade behind, with the first double-tracked steam train built in the 1840s. Russia was a decade behind again — the 1850s. But from a historical standpoint, this technology was evolving all around the world at basically the same time.

HOW DID TRAIN NETWORKS CHANGE THE WORLD?

As soon as train networks started in any given country, that country was changed forever:

- Train companies rapidly became the biggest companies in any country. Factories don’t come anywhere near competing with their magnitude.

- Train companies created the modern company, and the accounting practices of modern corporations.

- People could now live further away from their place of work.

- This led to fewer people living near their natal homes in the country, more in the city: urbanisation.

- Trains also led to what we call ‘the agglomeration effect’, where like is grouped with like. Some areas were reserved for only residential houses; other areas for industry.

- People could source goods from further afield, opening up the range of items available to them.

- Basically, trains ushered in the Industrial era. Trains are key to capitalism.

- Some parts of the world have built relatively few railway networks (e.g. South America) and this is a factor in the relatively less prosperous state of their economies.

(A century later, America’s rocket on the Moon also spurred a new era of technological change, and an advantage for the countries who invested in space travel technologies.)

HOW DID 19TH CENTURY PEOPLE FEEL ABOUT RAILWAYS?

Most people in the 1800s were pro-railway because trains enhanced their lives. However, those with massive existing privileges weren’t so keen. Aristocrats did not want railways anywhere near their land. The poet Wordsworth was vocal about not wanting railroads into the Lake District as he felt they were a blight on the landscape.

However, compared to modern highways and roads, trains are relatively gentle on the landscape, with railways built along the natural curves of a landscape with the aid of tunnels and bridges rather than carving steep gradients into it. Compared to cars, a railroad’s environmental footprint is small. Railways blend into a landscape in a way that roads do not.

BUILDING RAILWAYS

Railroad workers were called “navvies” because they also built canals. (Navvie is short for “navigator”.)

Building railways was dangerous work with much hard labour — lifting, digging. This job required brute strength of a magnitude rarely required today in any profession. Workers faced all kinds of terrain, from desert areas to jungles.

Railway companies required many workers, and were huge employers. Building a train track required high levels of human coordination.

America’s railway network was especially huge in magnitude. Florida’s railway stretched 100 miles into the sea. America built 8 miles of railway per day for 86 years from 1830. This was hugely costly.

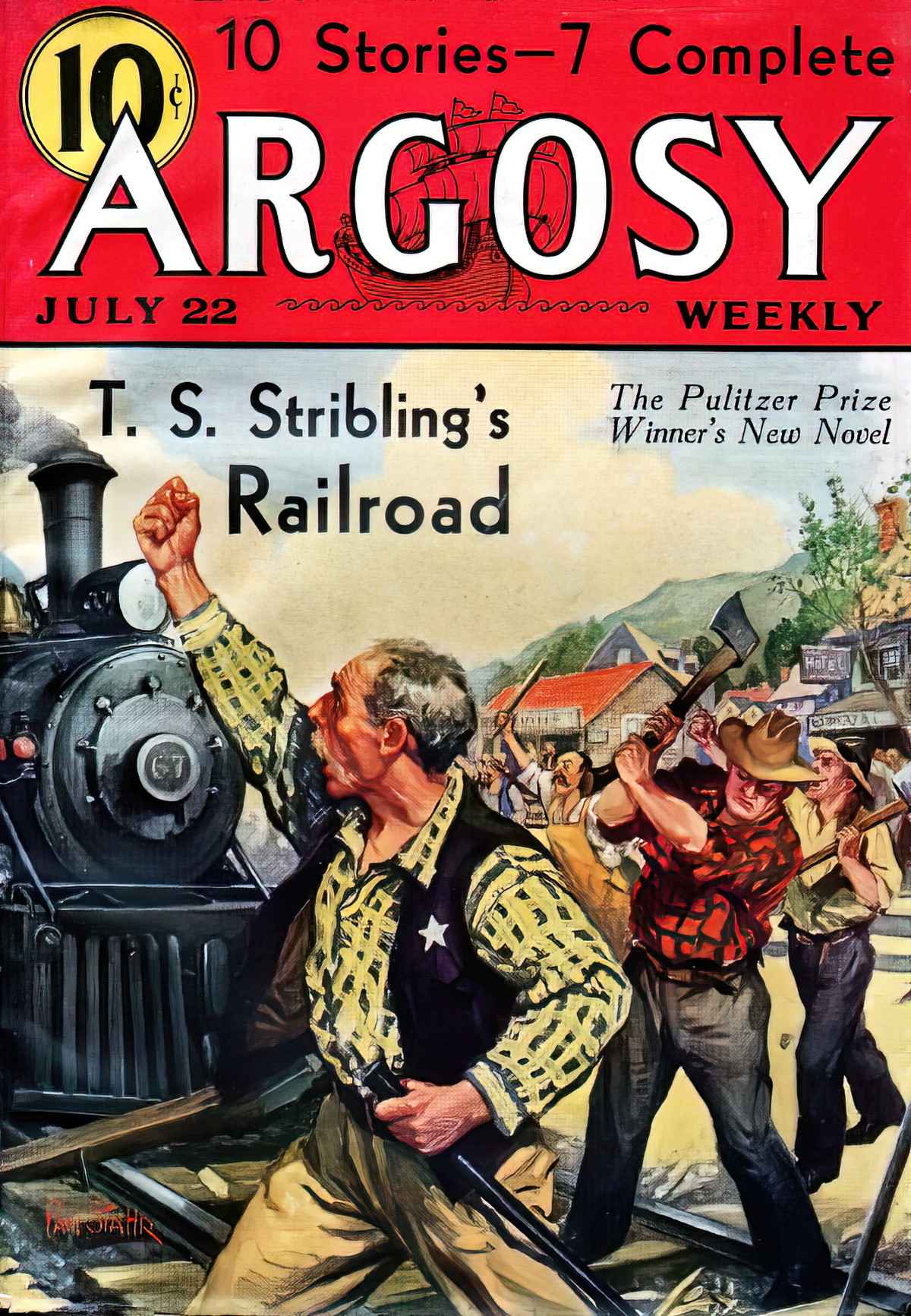

RAILWAYS AND TRADE UNION ACTIVITY

Since railway companies were so huge, they became the centre of trade union activity in countries across the world.

Building a railway is itself a huge feat of human co-ordination, which led nicely into the huge workforces banding together to petition for better pay and conditions. Once trains had become essential to industry and life itself, a strike could bring a nation to a standstill. Workers had excellent collective bargaining power.

AFFORDABILITY

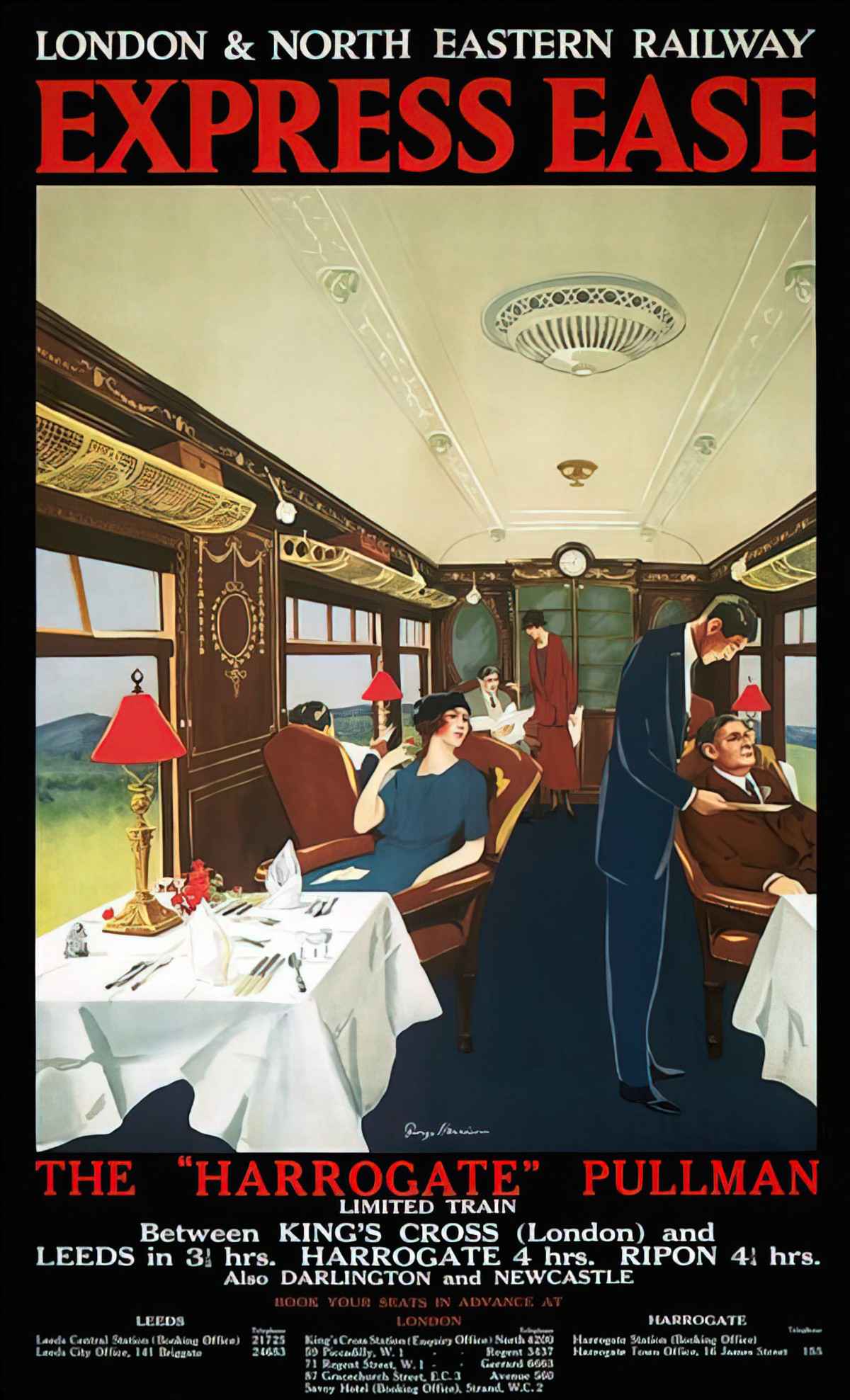

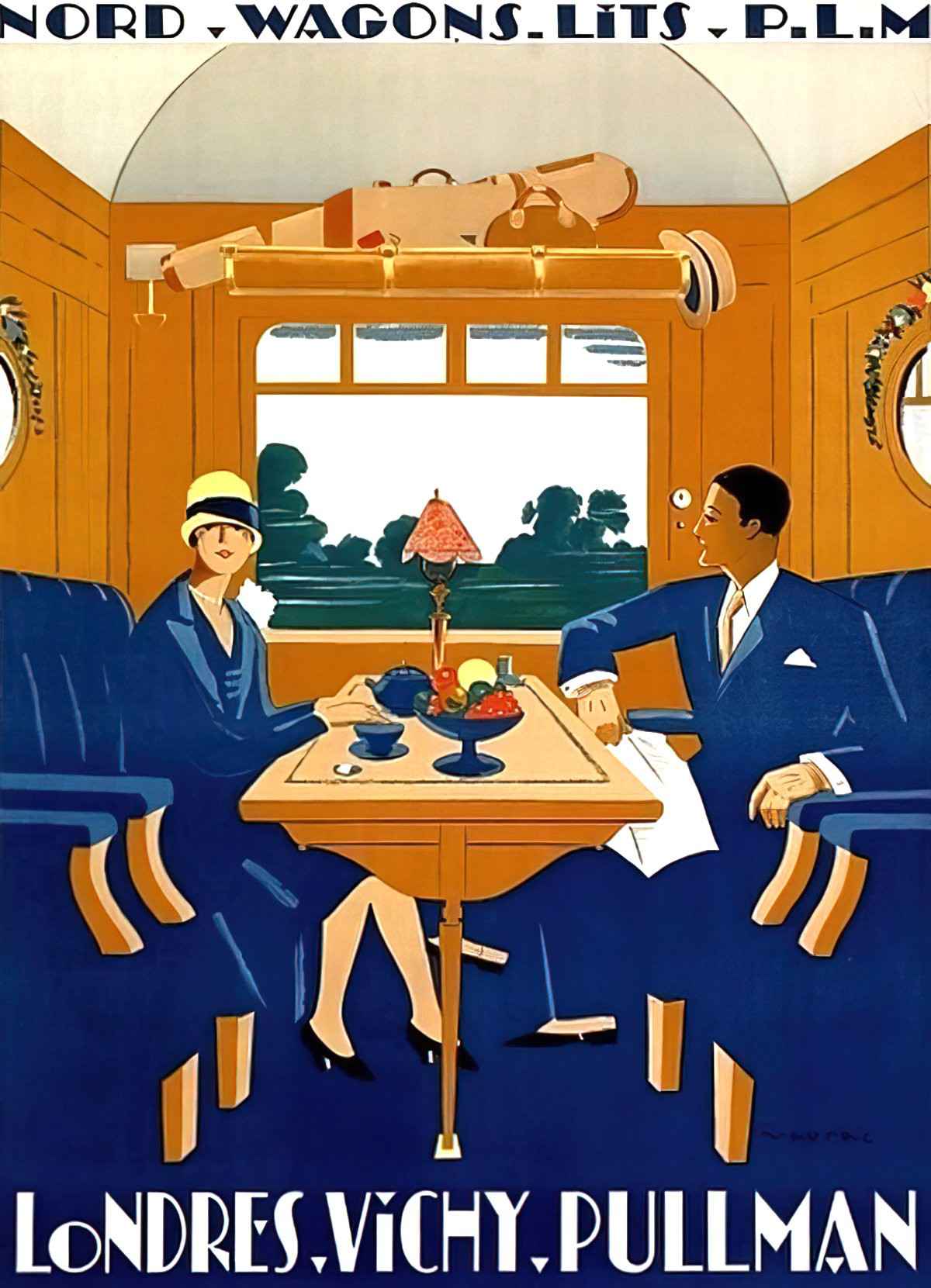

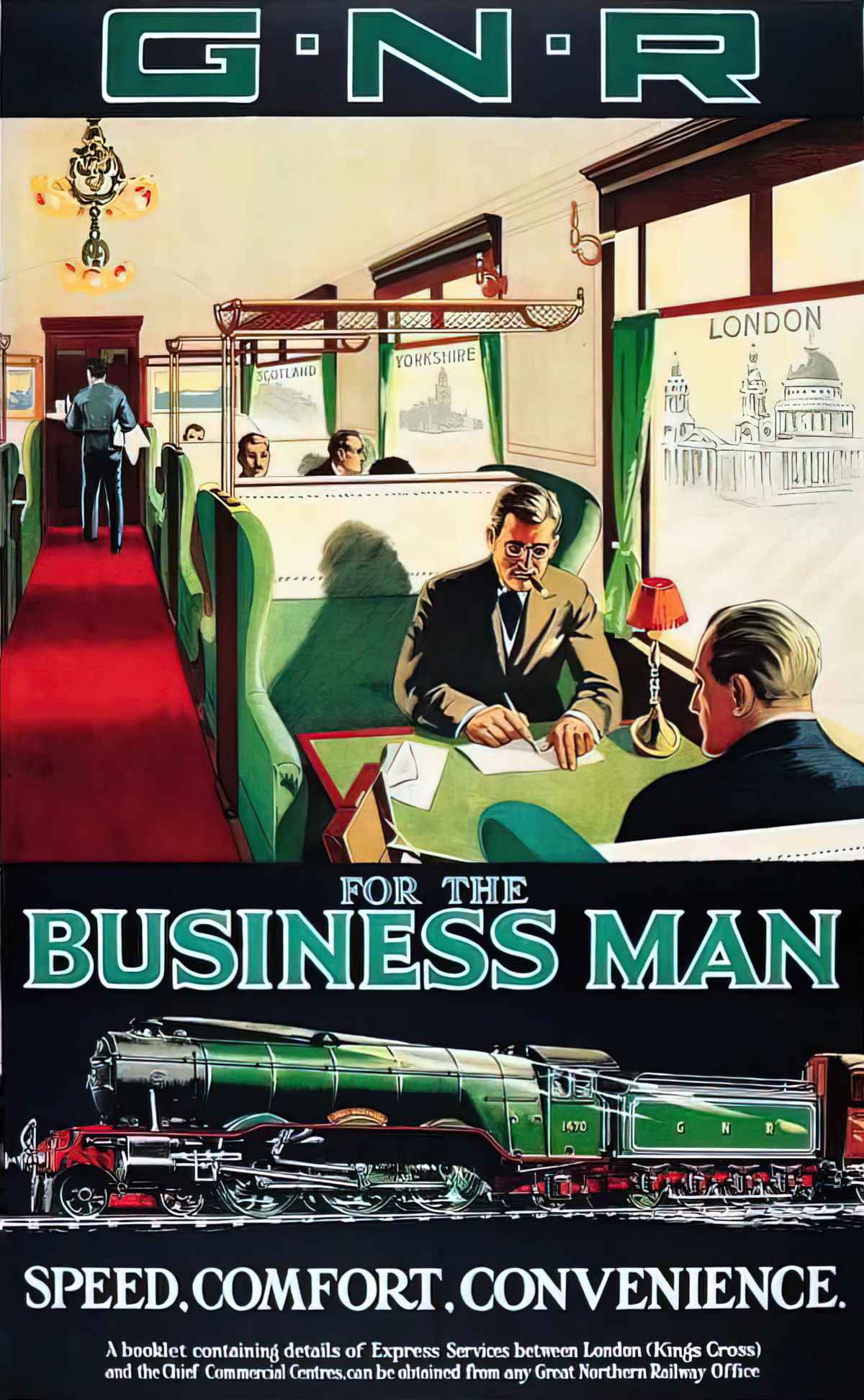

In the very beginning train travel was for the wealthy, which is ironic (if wholly predictable). Remember, the landed gentry didn’t want railway lines anywhere near their own land. But once they opened up to passengers, the wealthy were the first to make use of trains for their own travelling pleasure.

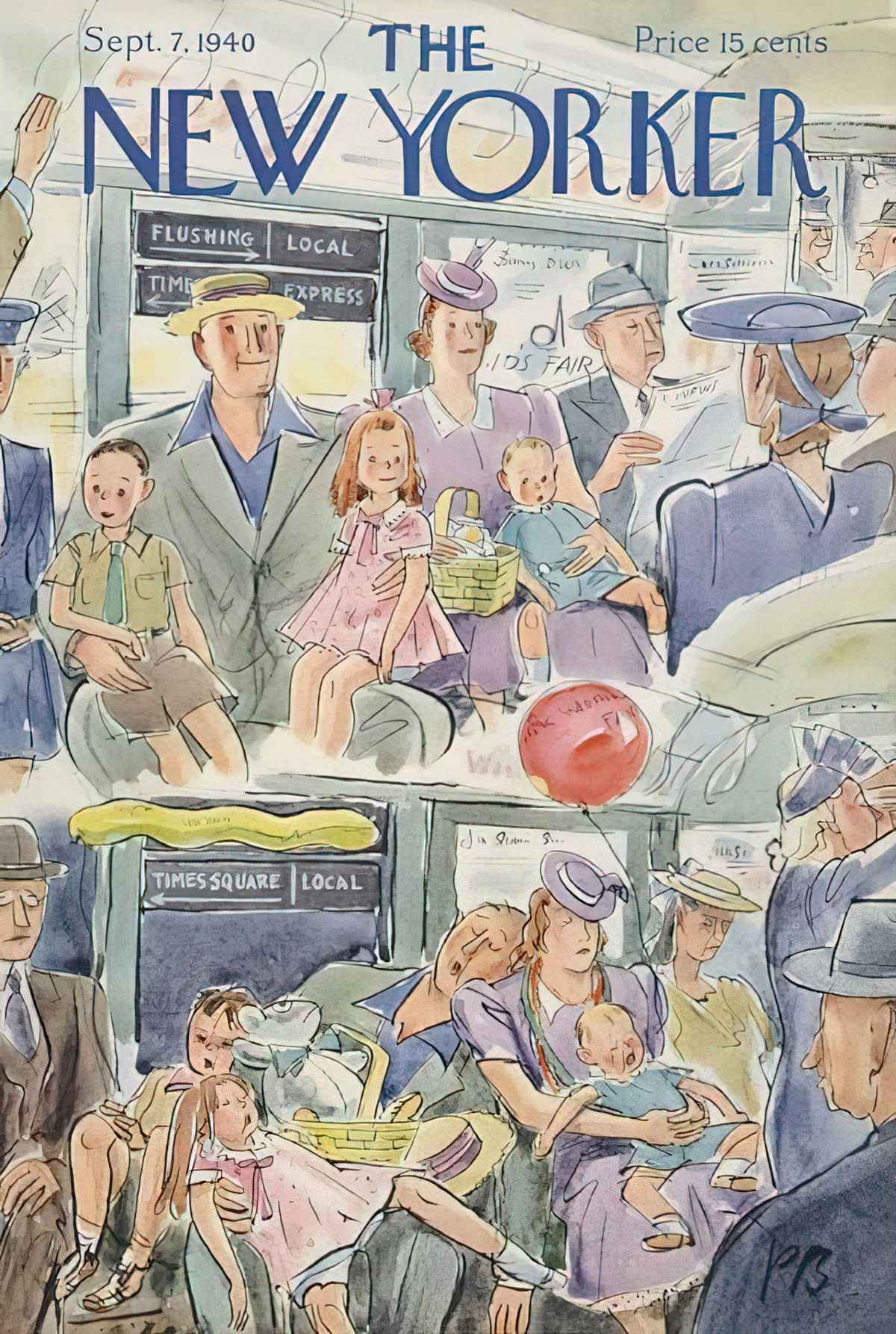

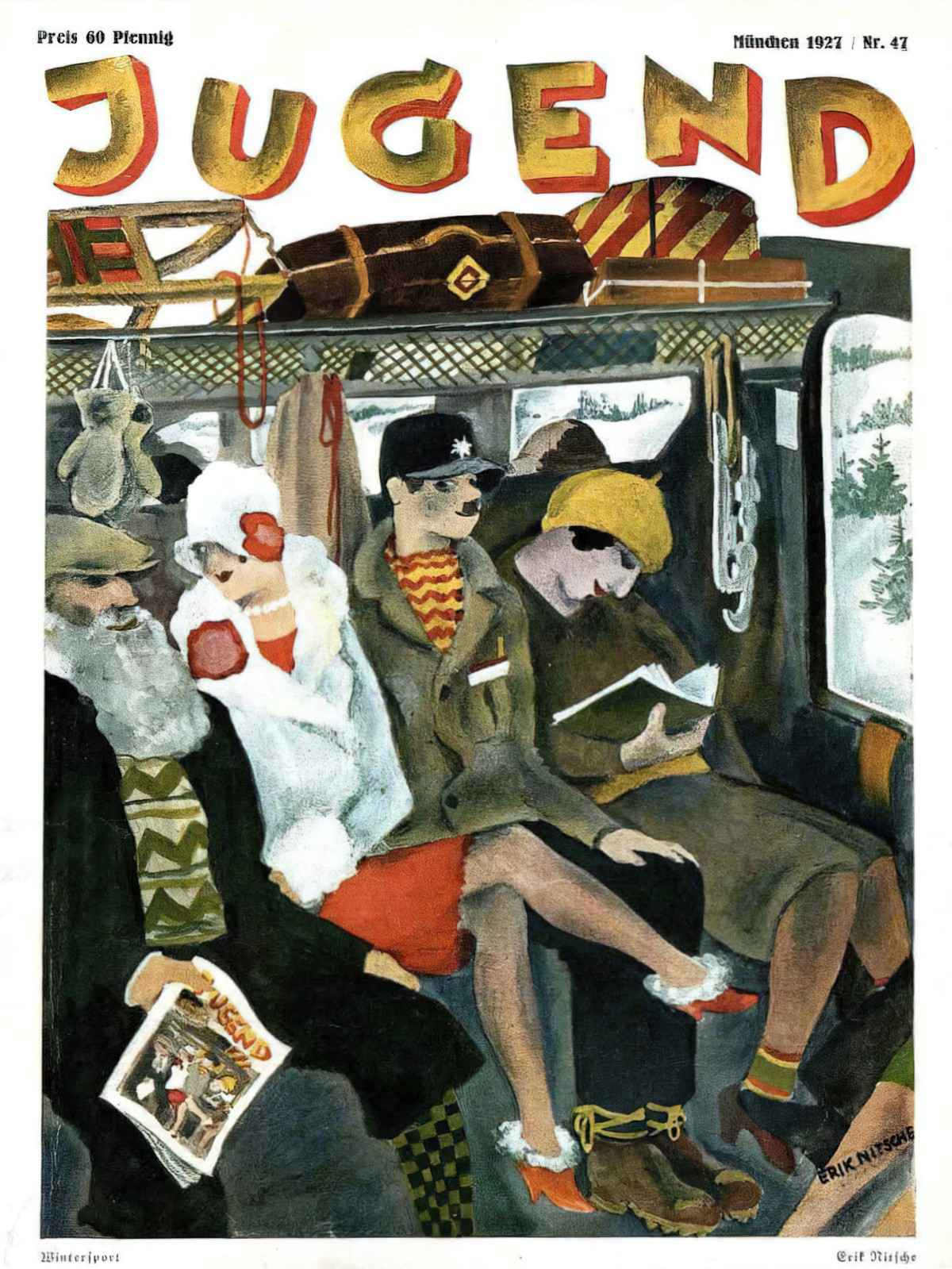

However, train travel soon became the main mode of travel for everybody. Companies introduced separate classes of travel so the wealthy wouldn’t have to associate with the lower classes. Across the different countries there were generally three classes:

- First class (you paid a lot more)

- Second class

- Third class (very crammed)

In the United Kingdom it was recognised that everyone had the right to travel. (More to the point, factories required a labour force who could make it in to work.) So the government instituted a rule for train companies, who were required to charge a set fee based on a certain cost per mile.

Train companies found it highly profitable to cram many people into small carriages. These “passenger” carriages had initially been built to transport goods, not humans.

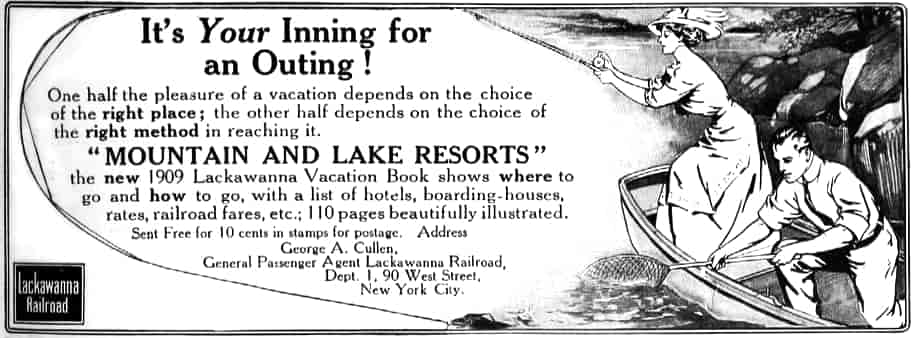

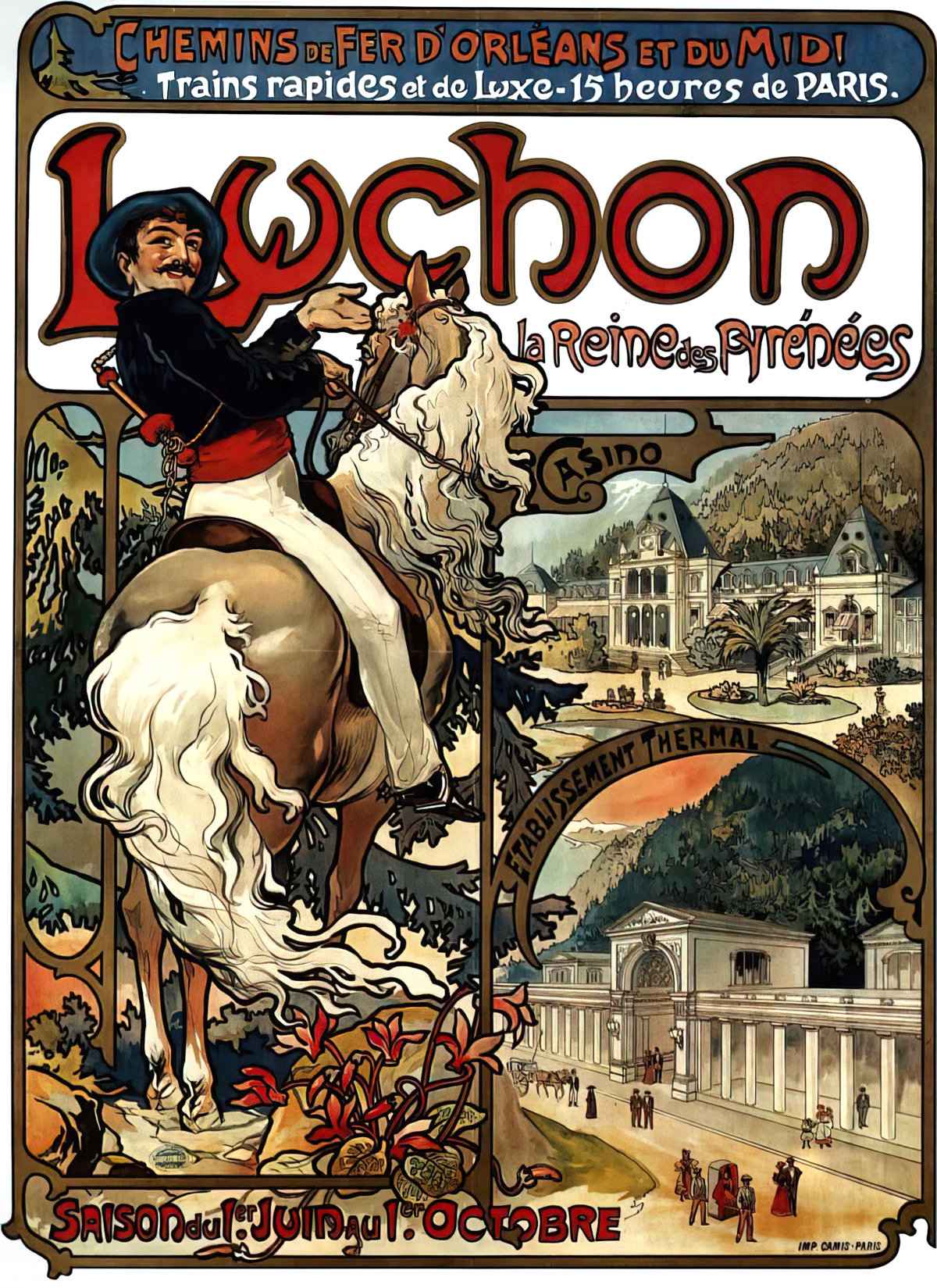

HOLIDAY TRAINS

By the 1940s in England huge trains with 20-30 carriages transported people on Bank Holidays to places such as Leeds or Manchester to the seaside for day trips.

Thomas Cook invented train tours for picnic day trips. These soon became weeklong holidays to the seaside or mountains. Basically, railways enabled “holidays”. Previously people had been unable to ever get to the seaside or the mountains because horses weren’t able to transport them there.

Of course, once people started taking holidays, a tourist industry popped up to support them, with hotels, souvenir shops and so on.

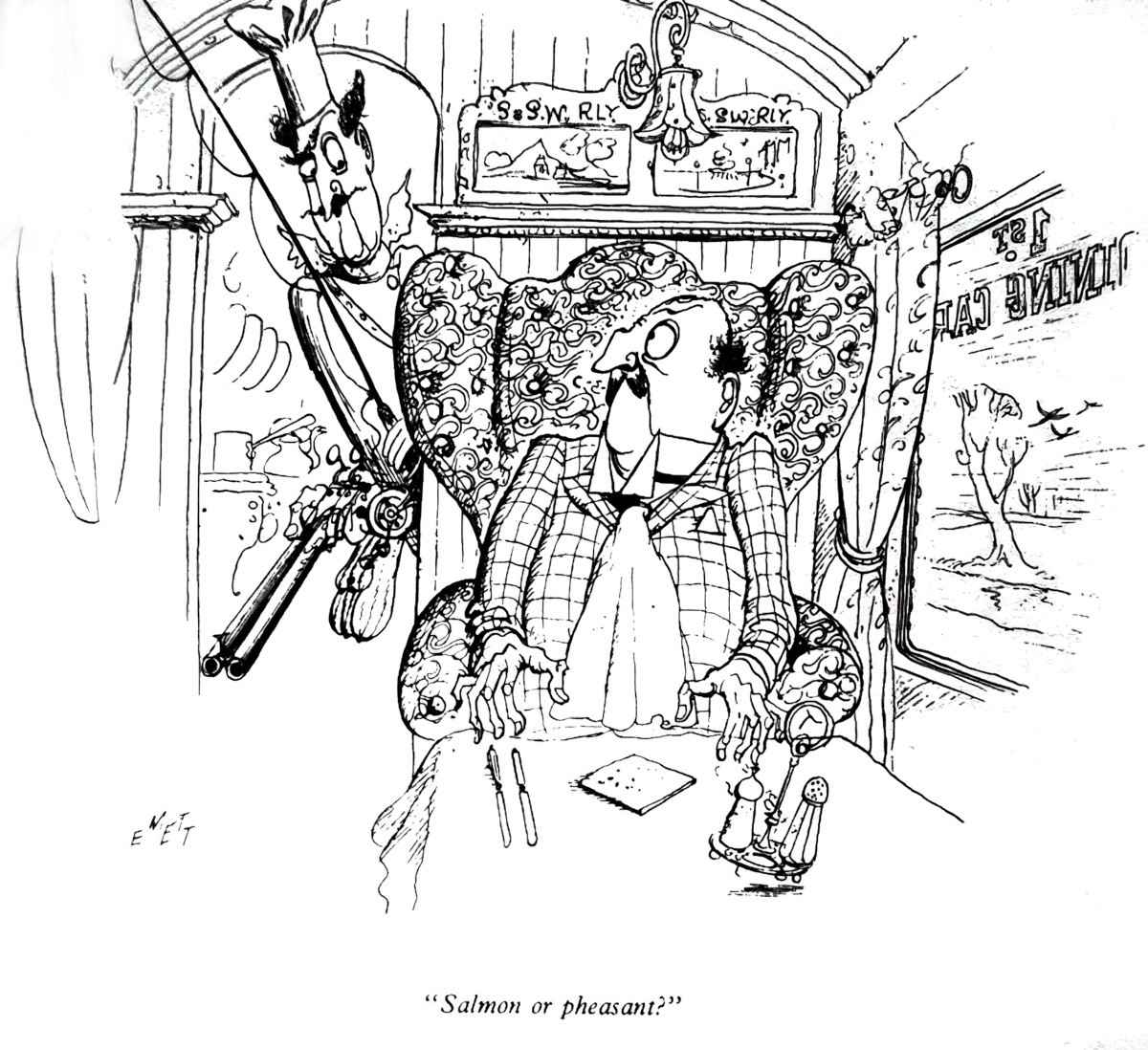

FACILITIES ON EARLY TRAINS

For the first 20-30 years of passenger train travel in England there were no facilities! Need to use the loo? Too bad! But trains would stop every hour or so precisely so passengers could hop off and use the facilities at a station.

Trains consisted of compartments, each with 6-8 people who had no access to the corridor. However, the guard was able to make it between carriages as he had the job of inspecting tickets. He walked along a board on the outside of the train. Of course this was a dangerous job!

By the mid 19th century (1860s-70s) the first corridor trains enabled toilet facilities and dining cars. This meant trains no longer had to stop every hour. Smaller stations no longer had trains stopping in numerous times a day, which destroyed any local industry which had previously supported passengers stopping for a break. Some towns had developed solely for the purpose of providing food for travellers.

Sitting about 100 miles West of London, Swindon is one such example. Trains no longer needed to stop at Swindon once toilet facilities were installed on trains, but train companies were required to stop there anyway to support the town. The rule was trains had to stop for 20 minutes. (This was enough time for people to both use the loo and buy food.) This arrangement continued until the 1880s and explains why it took decades to offer facilities on trains — they weren’t especially wanted! However, by the end of the 19th century, facilities on British trains were universal.

In the USA the situation was different. America had open carriages right away, without compartments. Partly this was because journeys were longer, covering more ground. American trains were quicker to get toilets and there wasn’t the same politics around installing them.

This week on A Taste of the Past, host Linda Pelaccio is taking a trip on the Trans-Siberian Railway with author Sharon Hudgins. Sharon has traveled along this particular railway numerous times and worked for University of Maryland University College for 20 years, primarily as a professor in the university’s programs in Germany, Spain, Greece, Japan, Korea, and Russia. She also served as UMUC’s program administrator at two universities in Siberia and the Russian Far East, and today chats with Linda about the evolution of the Trans-Siberian Railway dining car from the initial journeys to the practice today. After the break, Sharon shares facts about the food vendors that passengers would see across the long journey via station stops and also how the train line has endured through historic events like both World Wars, the Cold War, as well as the current political environment in Russia. Ever wondered the background behind the term ‘mystery meat?’ Tune in to find out and hear all about this legendary train trek. This program was brought to you by Cain Vineyard & Winery.

“There wasn’t a single train called the Trans-Siberian Express, a whole lot of people think there was this one great big legendary train, but it was the route was legendary.” [14:00]

“The real point of the the Trans-Siberian Railway is that it was the only way to get across Russia… all the way across the country.” [16:55]

—Sharon Hudgins on A Taste of the Past

History of Dining on the Trans

TRAIN ROBBERY

Train companies made money in many different ways, and mail was an important earner from the get go. Of course, mail can be valuable. People don’t just post letters, but also goods.

This was especially the case in America, where trains hauled bullion. This made train robbery especially lucrative for thieves. Compared to England, there are many very remote areas in the USA, where there’s literally nothing but a train track.

Of course, train robbery happened in Britain, too. The nice thing about trains for robbers, no matter which country: They run on very predictable schedules and you know exactly where to find them.

The Great British Train Robbery (1963) is now infamous. Most people have at least heard of it because of all the films, books and TV programmes about it. Basically, the robbers stole a whole lot of used bank notes which were on their way to being destroyed.

TRAIN ACCIDENTS

When was the first train accident? The first death that happened due to an actual train (so we’re not counting deaths from overwork building train tracks) occurred at the opening of the Manchester to Liverpool Railway. A politician called William Huskisson didn’t seem to understand how trains worked. He got off one train and didn’t look before dashing across the parallel track. He caught sight of the Prime Minister and was rushing to greet him, failing to notice another train while walking back to his carriage. The death of William Huskisson marred the beginning of train travel.

The early 1840s saw a train fire in France which killed many people. This happened on a holiday train to Versailles.

There weren’t actually many collisions in the early days of train travel, but then, there also weren’t many trains.

However, once trains increased in number, then the head-on collisions started happening big time. The late 19th century was particularly notorious for train crashes. Writer Charles Dickens was involved in one, and you may have read his horror story “The Signalman” in which he was probably processing his trauma.

During the second World War another sort of train catastrophe kept happening: Runaway trains. Two standout examples include one in Romania and another in France.

However, after WW2, people started taking train safety more seriously, leading to a massive decrease in the number of train accidents. Note that trains were already far safer than literally any other form of transport at the time. These days they really are extremely safe, and remain the safest form of land travel.

TRAINS AND WAR

Since the very first railway — the 1830s — trains have played a key part in war. Rail networks changed war because they were now able to supply the front lines.

Contrast modern war with the Battle of Waterloo (1815). Soldiers had to stop fighting because the horses needed feeding. Without supplies, everyone ran out of oomph.

In the current Russo-Ukraine war, trains are vital to sustaining Putin’s war effort. Trains play a key role in sustaining conflict, which is why blowing up railways is a key tactic.

TRAINS CAN UNITE

But trains can also be a uniting force. The 1860s (during Civil War) saw the beginning of America’s first transcontinental railway, completed in 1869. This railway undoubtedly contributed to a united country. Without that railway, it is possible that the “USA” (and the West) would not have become so dominant in the 20th century.

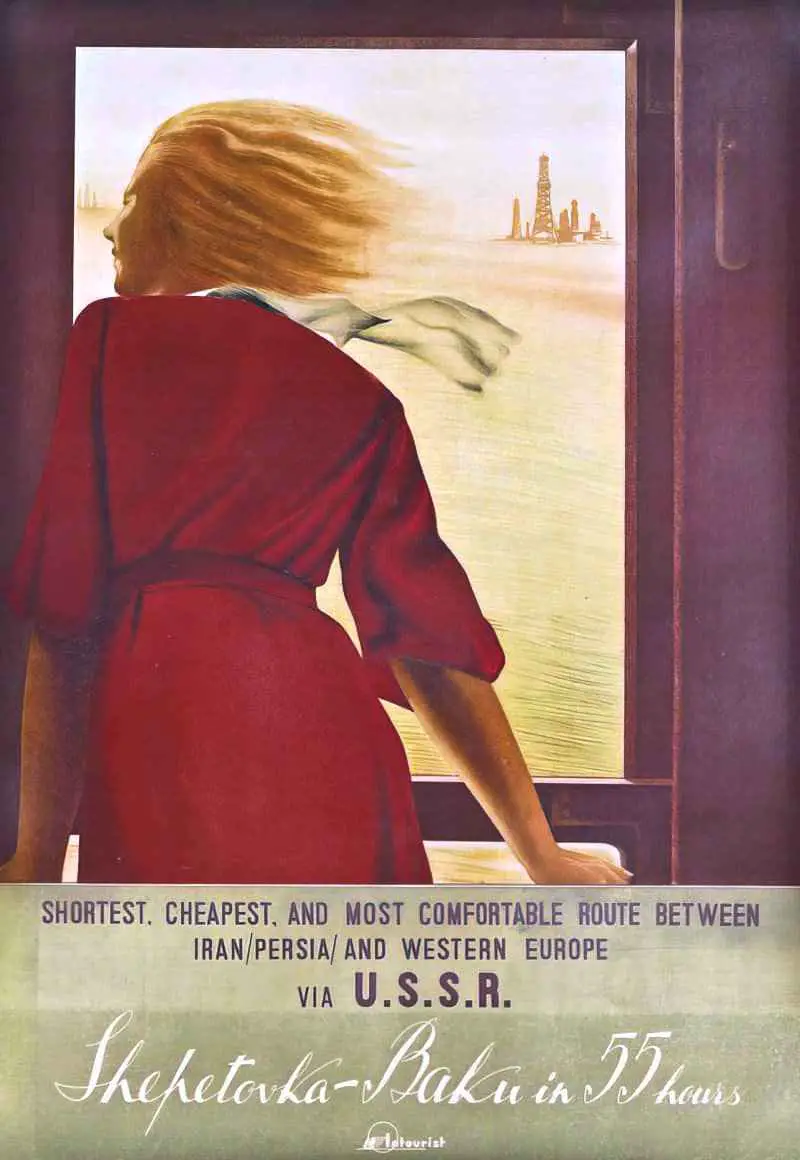

Likewise, the Trans Siberian held Russia together. Without it, Siberia would probably not have become the same country as Russia as geographically it sits in Asia. The connection to Russia by train provided a cultural and political link.

TRAINS AND THE IMPERIAL PROJECT

Trains in India were not built for Indian locals, but were instead built to establish the British Empire and transport goods for sale. However, Indian locals took to trains more than the British expected. India holds together as a nation partly due to its strong network of railways.

Note that where empires build rail networks elsewhere (notably in India and Africa), their Imperial Projects are for both economic and military imperialization. The point is to both make money and also take over a country’s military force.

TRAINS IN THE LATE 20TH CENTURY

Trains started to lose profitability after the proliferation of the motorcar. Until families had access to private vehicles, there had been no alternative for reliable long-distance travel.

For transporting goods, motor coaches and goods lorries took away some of the freight traffic previously transported by train.

When did this start to happen? Trains held up between the World Wars but once the Second World War was over there was mass motorisation across the world. It became impossible to run a profitable railway company despite trains remaining very important, so in most countries the state intervened and took train companies over.

Many countries cut their railway networks right back, including Australia and New Zealand. In the South Island of New Zealand it used to be possible to visit all the major and medium sized towns by train, but not anymore. The USA cut back except on the East Coast.

However, some countries realised that trains would keep much congestion off the roads and instead invested in the dieselisation and electrification of their rail networks. Japan is an excellent example of that.

Some countries are much better than others at recognising the role of rail networks as vital infrastructure. Some countries have managed to subsidise trains without the politicisation. (Look at England versus European continental countries.)

By the 1970s, people around the world had realised that although cars great personal freedom, as vital infrastructure, trains were here to stay. This realisation led to some renewed investment.

Basically, across the 20th century trains went full-circle from important, in decline to important again.

TRAINSPOTTING

Trainspotting is a hobby which used to be very popular, especially among adolescent boys. Basically, trainspotting is the practice of watching trains with the aim of noting distinctive characteristics. It appeals to our instinct to collect, and provides a reason to visit new parts of your country. “Bashing” refers to going somewhere for the purpose of seeing trains. People who love trains also often love radios.

These days, train enthusiasts tend to call themselves railfans.

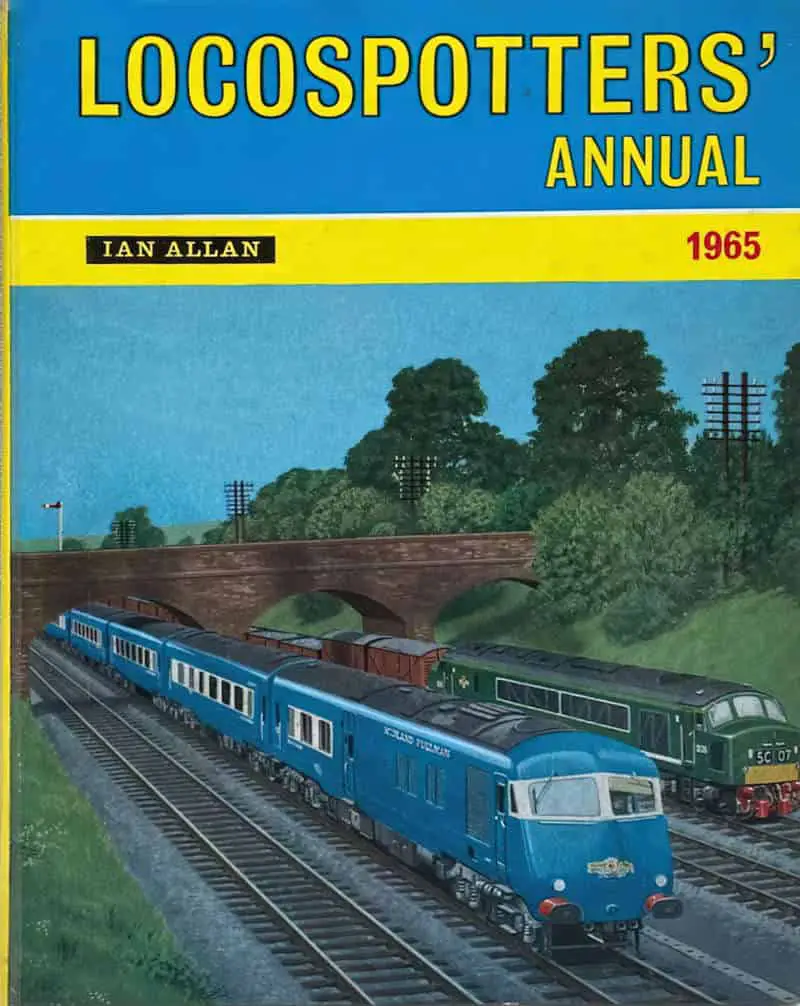

In England, a train clerk called Ian Allen printed a list of all the locomotives across the country and sold it as The Locospotters’ Annual.

Most (straight) trainspotting boys lost the interest once they became interested in girls, and those who persist with the hobby into adulthood are seen as a little strange by the mainstream as a result. A derogative word for trainspotter is ‘anorak’ because trainspotters will brave wet weather to pursue their interest. (Note that ‘anorak’ still refers to an actual raincoat in other parts of the English speaking world e.g. in New Zealand.)

‘To grice‘ is another word for trainspotting, and ‘gricer’ is another word for trainspotter.

Although trainspotting is an especially British phenomenon, there are enthusiasts in other countries. In the USA trainspotters are pejoratively known as ‘foamers’ (because they are thought to metaphorically foam at the mouth whenever they see a steam locomotive).

In any case, a strong interest in trains is quite common, though non-normative and therefore easy to mock. Trainspotters know how to have low-cost fun. You don’t need to buy anything at all, which means you’re not contributing to capitalism. You’re also not interested in showing off your wealth to others, which means you are outside the societal pecking order. For as long as trains run, trainspotters have a never-ending stream of novelty, and always have something to discuss with likeminded enthusiasts.

On Trains You Lose Your Regular Self

The train is a perfect place to pretend to be a different person. He said he was French. He was on his way to work on his Ph.D. in Art History in San Antonio. He had grim opinions on organized religion. He could have been flirting with me, but more likely he was just bored.

Secrets of the New York City Subway

On a train you are both alone and with others, at once. Plots frequently include villains and criminals jumping onto a train, becoming one of the crowd. In narrative, movie theatres are frequently used in the same way.

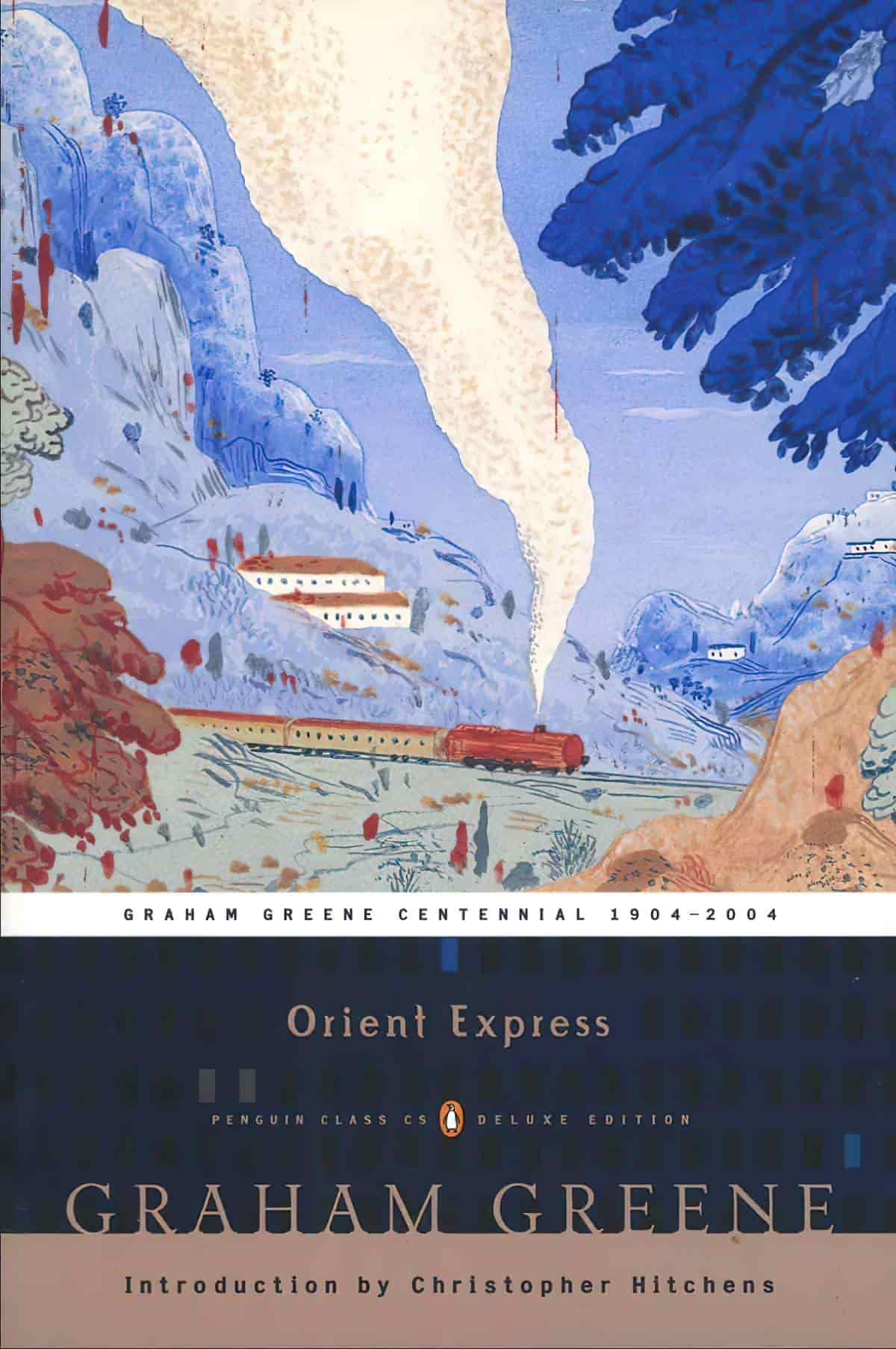

ORIENT EXPRESS BY GRAHAM GREENE (1932)

As the Orient Express hurtles across Europe on its three-day journey from Ostend to Constantinople, the driven lives of several of its passengers become bound together in a fateful interlock. The menagerie of characters include Coral Musker, a beautiful chorus girl; Carleton Myatt, a rich Jewish businessman; Richard John, a mysterious and kind doctor returning to his native Belgrade; the spiteful journalist Mabel Warren; and Josef Grunlich, a cunning, murderous burglar.

What happens to these strangers as they put on and take off their masks of identity and passion, all the while confessing, prevaricating, and reaching out to one another in the “veracious air” of the onrushing train, makes for one of Graham Greene’s most exciting and suspenseful stories. Originally published in 1933, Orient Express was Greene’s first major success. This Graham Greene Centennial Edition, originally titled “Stamboul Train,” features a new introductory essay by Christopher Hitchens.

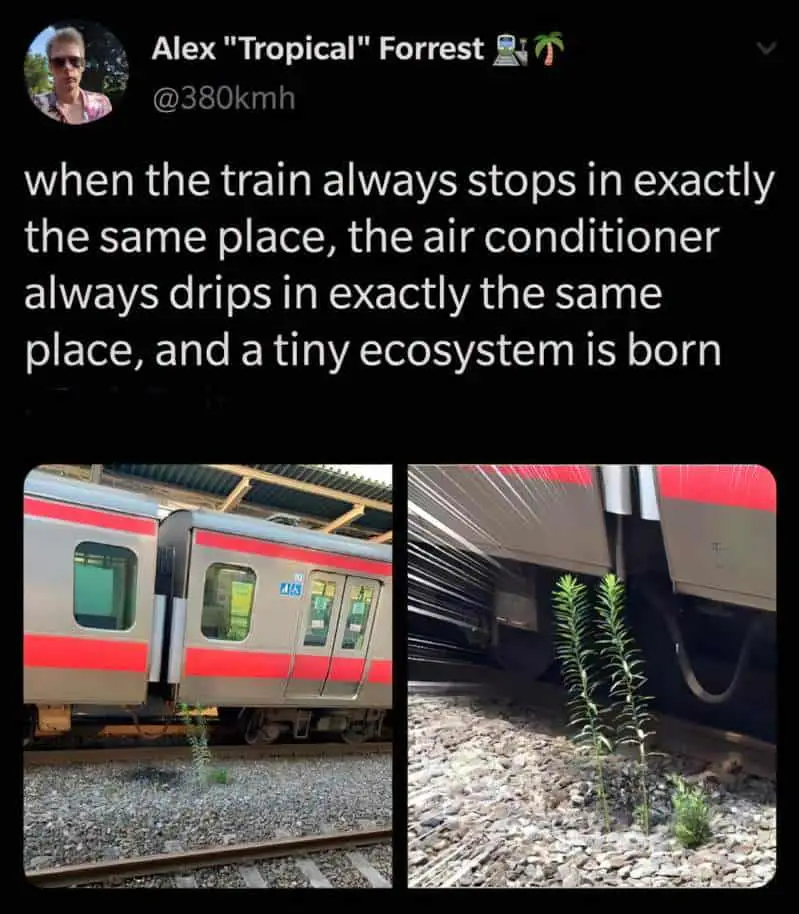

Trains as Symbols of Precise Regularity

On a train you may lose your ‘regular’ self, but trains are the epitome of regularity. At least, that’s the aim. Some countries (Japan) do better than others. Even where trains regularly fail in their regularity, trains are predictable beasts.

Subways As Journey Into The Subconscious

On subways, especially, you are taken into the metaphorical forest of your subconscious:

Thoughts very often grow fertile on the subway, because of the motion, the great company, the subtlety of the rider’s state as he rattles under streets and rivers, under the foundations of great buildings.

Saul Bellow, “A Father-To-Be” (short story)

The Train As Heterotopia

Trains are an example of a heterotopia. For more on that see this post. French philosopher Michael Foucault had quite a bit to say about trains:

A train is an extraordinary bundle of relations because [1] it is something through which one goes, it is also something by means of which [2] one can go from one point to another, and then it is also [3] something that goes by.

Foucault

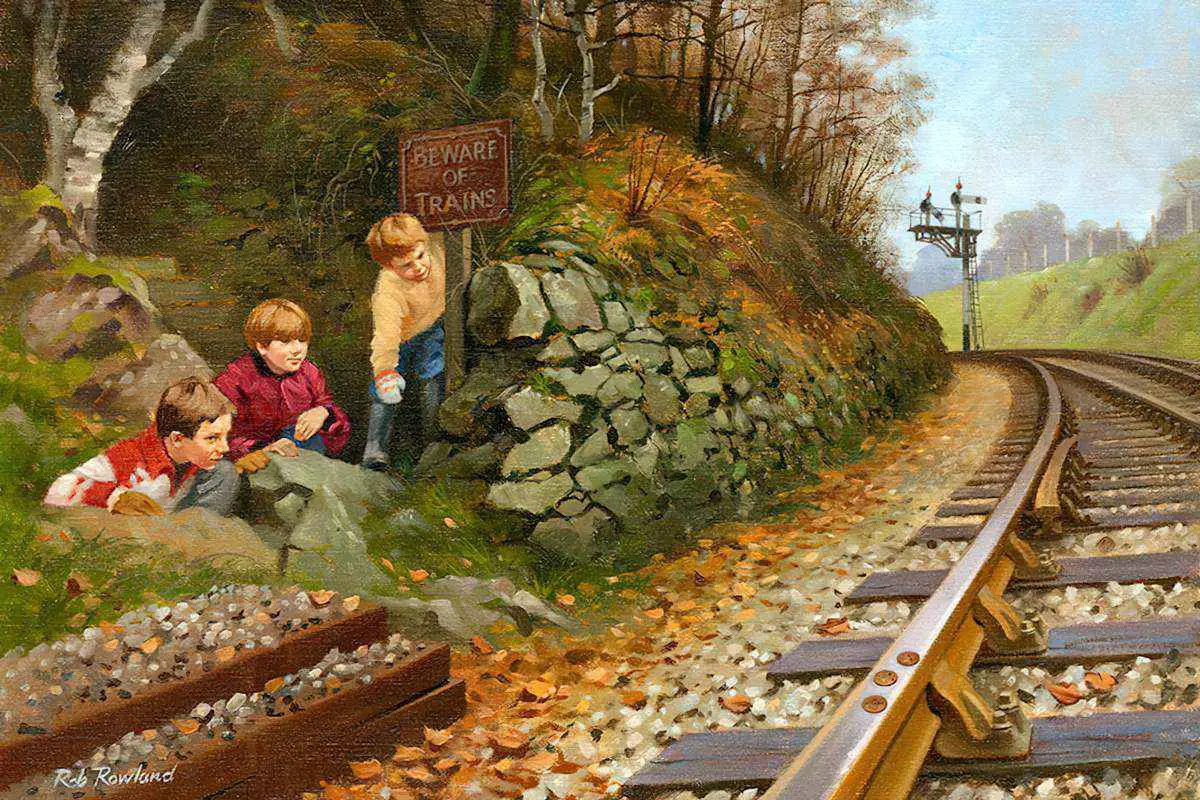

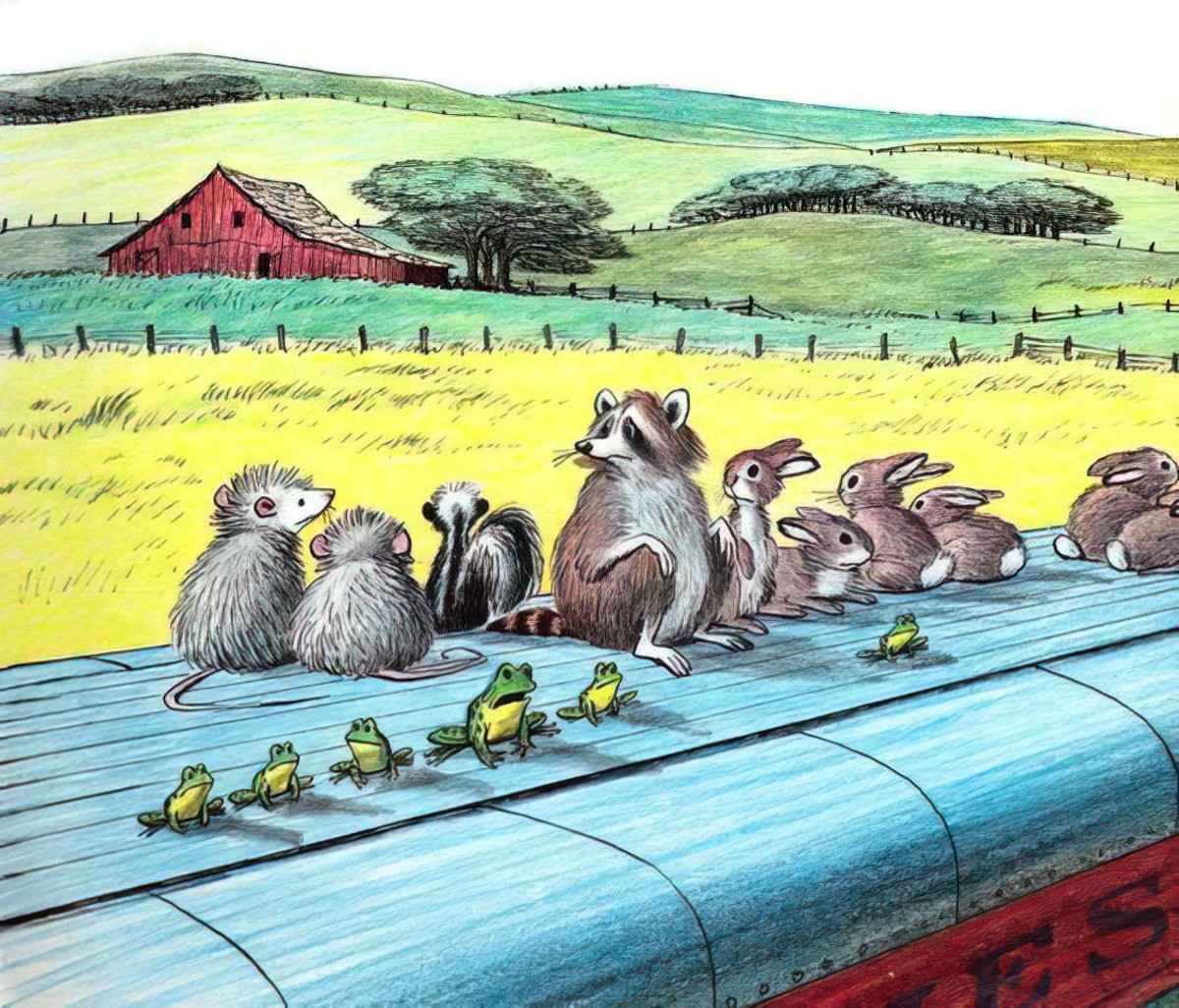

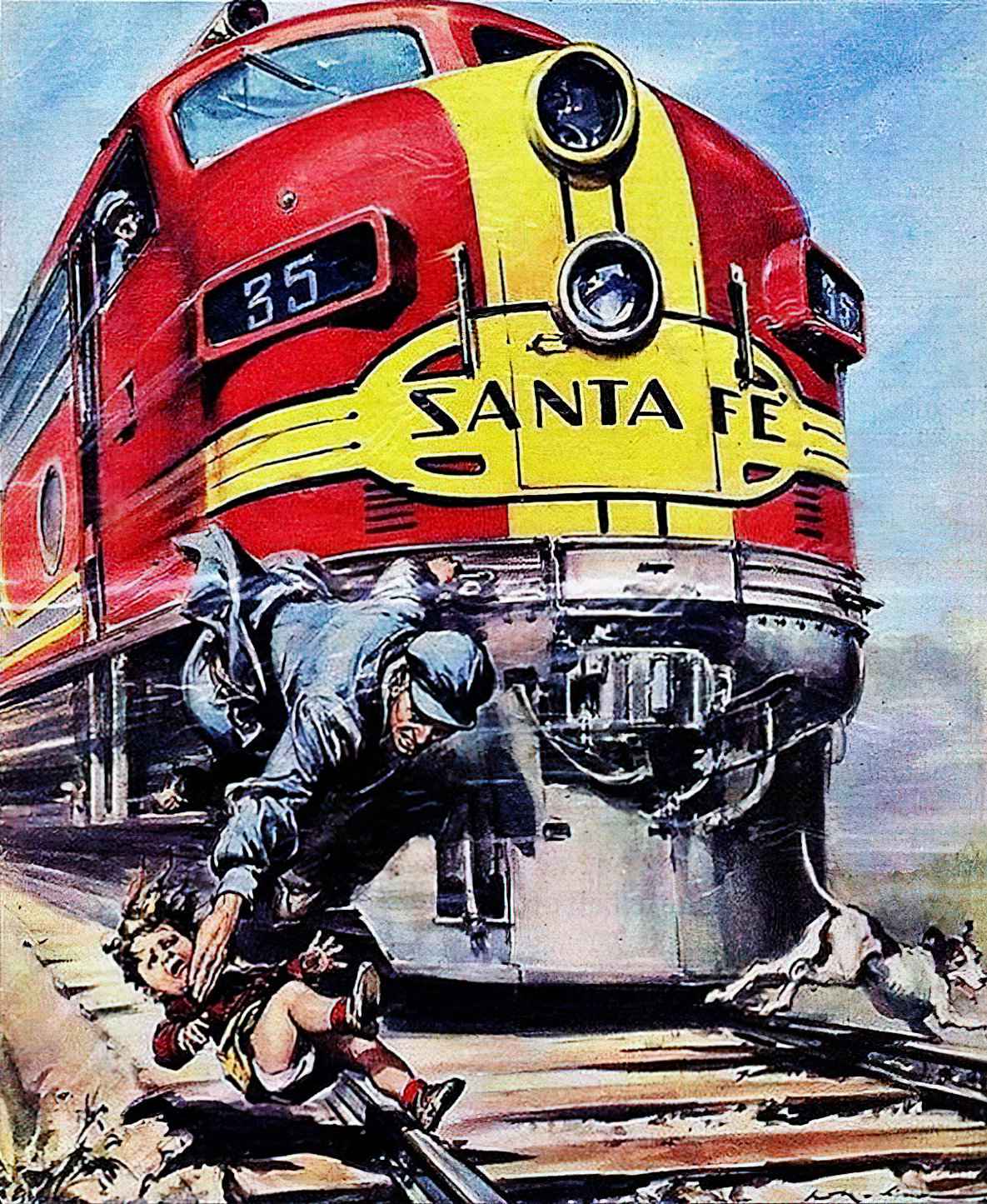

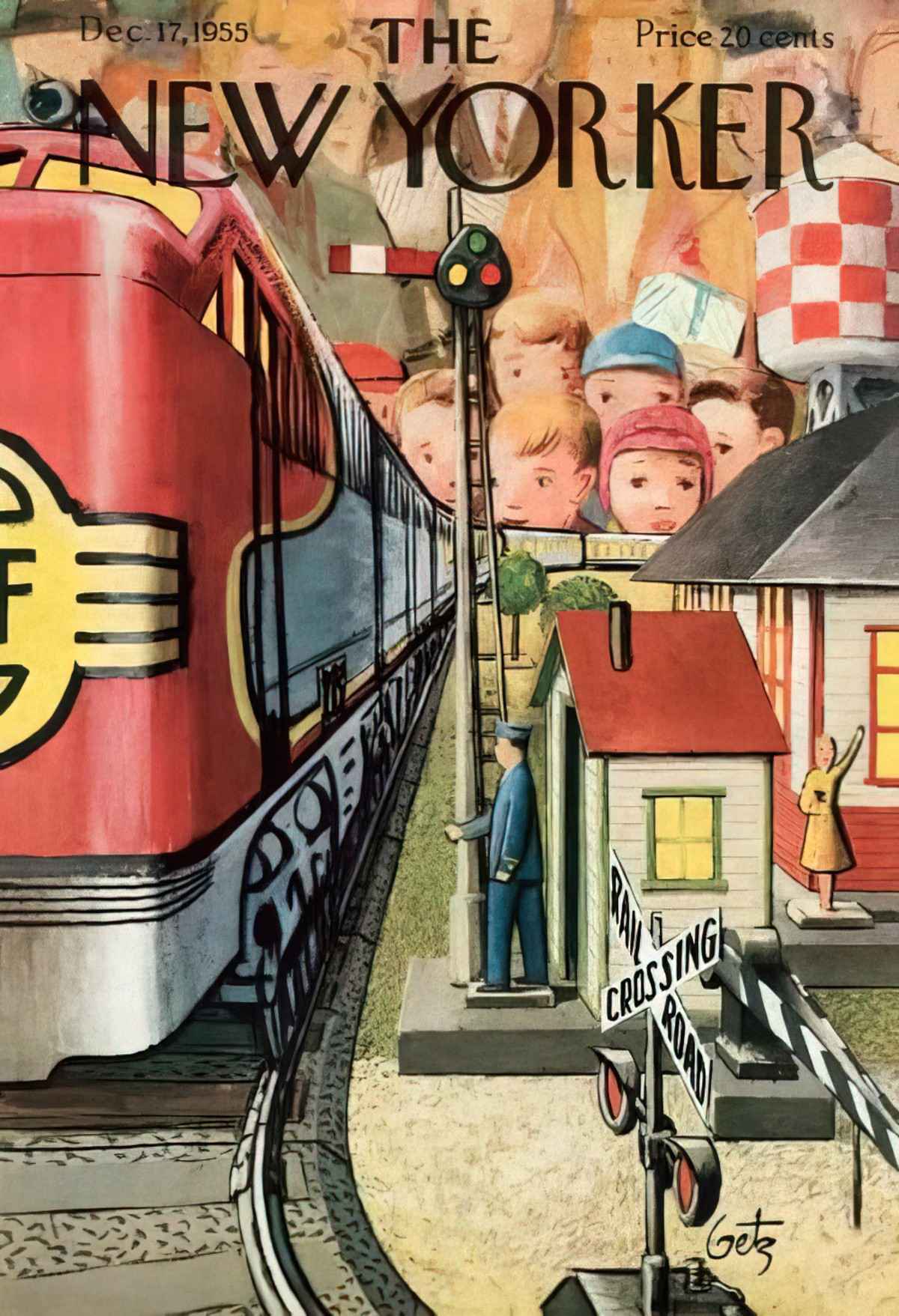

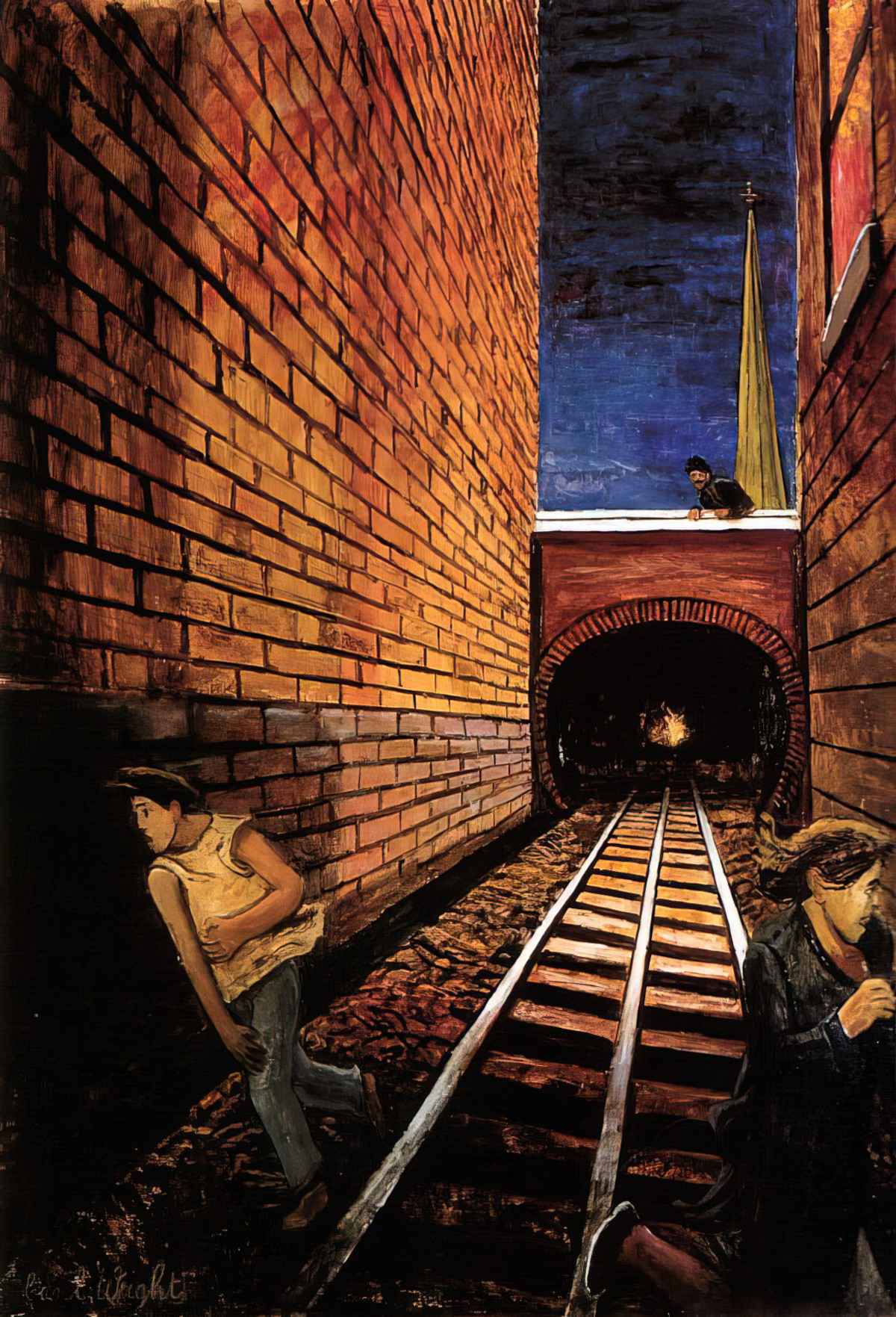

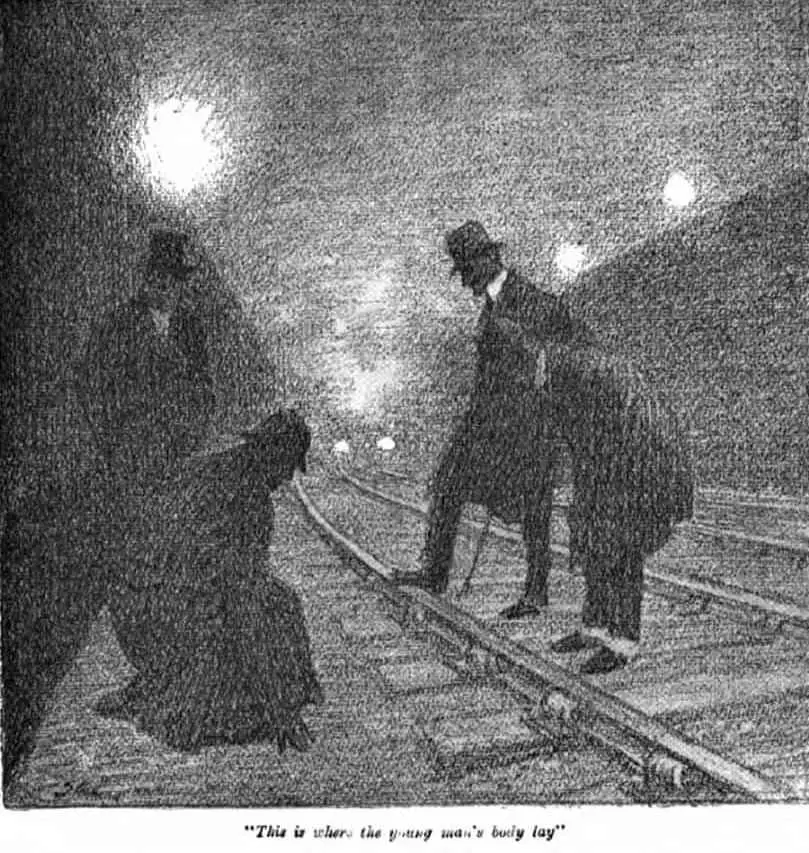

Some modern kids might not know what’s going on in the painting below, partly because children are more supervised these days and mostly advised against playing around train tracks.

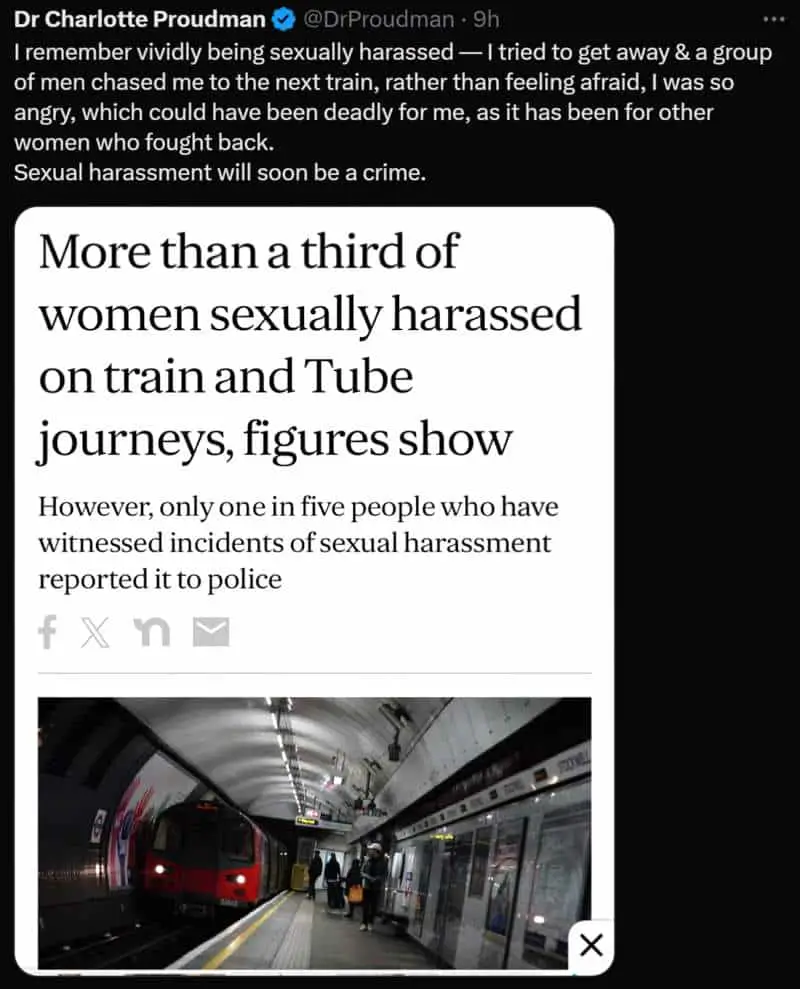

Some women are not permitted to walk about in the world alone, or even with other women. They must be accompanied by a male family member. Only well-to-do families can maintain such customs, since they entail the loss of women’s labor in the fields, but all women can be (and are) prevented from entering certain ‘public’ spaces, like mosques. It is not necessary, however, to pass laws excluding women from particular places. Exclusion can be achieved simply by abusive behavior by men toward any women who enter. In Turkey, women are in peril if they take a train alone, or enter a male preserve; in Saudi Arabia, women are forbidden to drive cars.

Beyond Power: On Women, Men and Morals by Marilyn French, 1986, p123

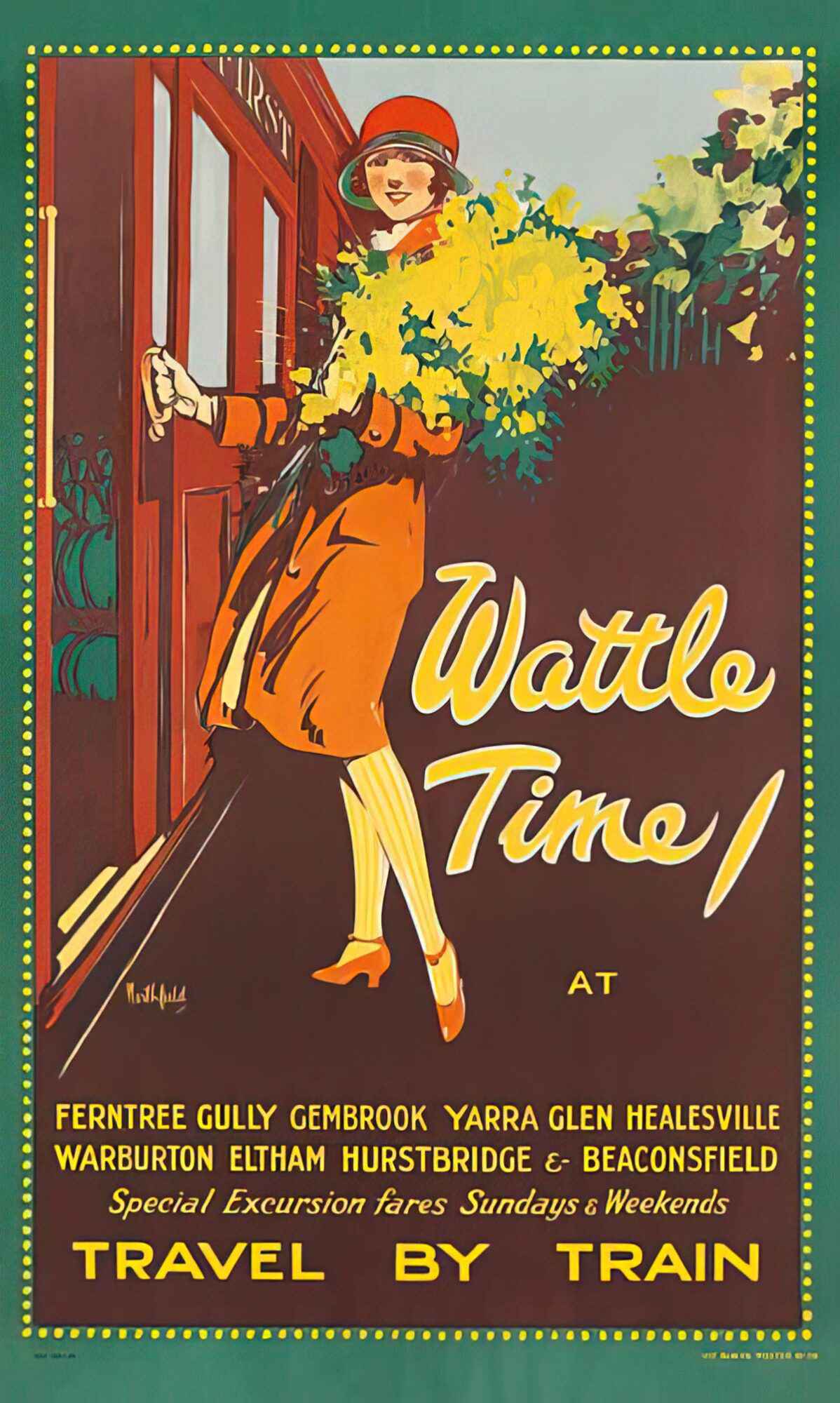

Trains Are Masculine-coded Spaces

Modern audiences are unlikely to feel this way, but trains initially excluded women.

Genevieve Bell, anthropologist and director of Intel Corporation’s Interaction and Experience Research, says the burgeoning use of the steam engine in the early 19th century incited an unusual panic. Some “experts” believed that women’s bodies weren’t fit to travel at 50 mph. “They thought that our uteruses would fly out of our bodies as the train accelerated to that speed,” says Bell.

Women’s Day

Trains Are Multi-layered, Liminal Spaces

Multi-layered places and objects are especially useful for creating a symbol web. Take any word which means two different things at once; or a tree, which can be covered in leaves or bare; or a sea, which has a surface and also great depth; blackberries, which are delicious but also a pest; the colour yellow, which means happiness but also decay… You get the picture. As Foucault mentions above, trains are great, symbolically, because the audience has not only two but THREE different relationships with trains.

Epiphanies Happen On Trains

Trains have a special position outside other forms of public transport. It’s no accident that Neal of Planes, Trains and Automobiles has his epiphany while riding a train. Compared to planes and automobiles, trains provide a meditative calm.

This is why here in Australia, The Indian Pacific: Australia’s Longest Train Journey proved such a hit for SBS, and led to a flurry of train bookings from enthusiastic viewers. The show is 3 hours of footage out a train window.

In her 2014 film Appropriate Behaviour, Desiree Akhaven bookends the story of a young woman trying to get over a recent breakup with scenes on a train. It is difficult to show epiphanies on screen. A lot relies on the skill of the actor, but the setting also helps. The train journey shows that the main character is ‘moving on’, but emotionally.

Trains As Metaphor For Passing Time

Lior’s song “This Old Love” assures the object of affection that “We’ll grow old together.” Lior also tells us that “time moves like a train”.

In fact, time moves nothing like a train. That is simply our human experience of it. For more on that read The Fabric of the Cosmos by Brian Greene.

Symbolically, we think of rivers in the same way we think of trains. When it comes to love and fate, it seems we like to think time moves forward in one inevitable line, and that our lives will look just like that long, smooth, uninterrupted train track that lies ahead.

For cynical twenty-three-year-old August, moving to New York City is supposed to prove her right: that things like magic and cinematic love stories don’t exist, and the only smart way to go through life is alone. She can’t imagine how waiting tables at a 24-hour pancake diner and moving in with too many weird roommates could possibly change that. And there’s certainly no chance of her subway commute being anything more than a daily trudge through boredom and electrical failures.

But then, there’s this gorgeous girl on the train.

Included in this symbolism: The idea that the past is the past, and it’s time to let the past go.

A train has a poor memory: it soon puts all behind it.

Ray Bradbury, “The Lake”.

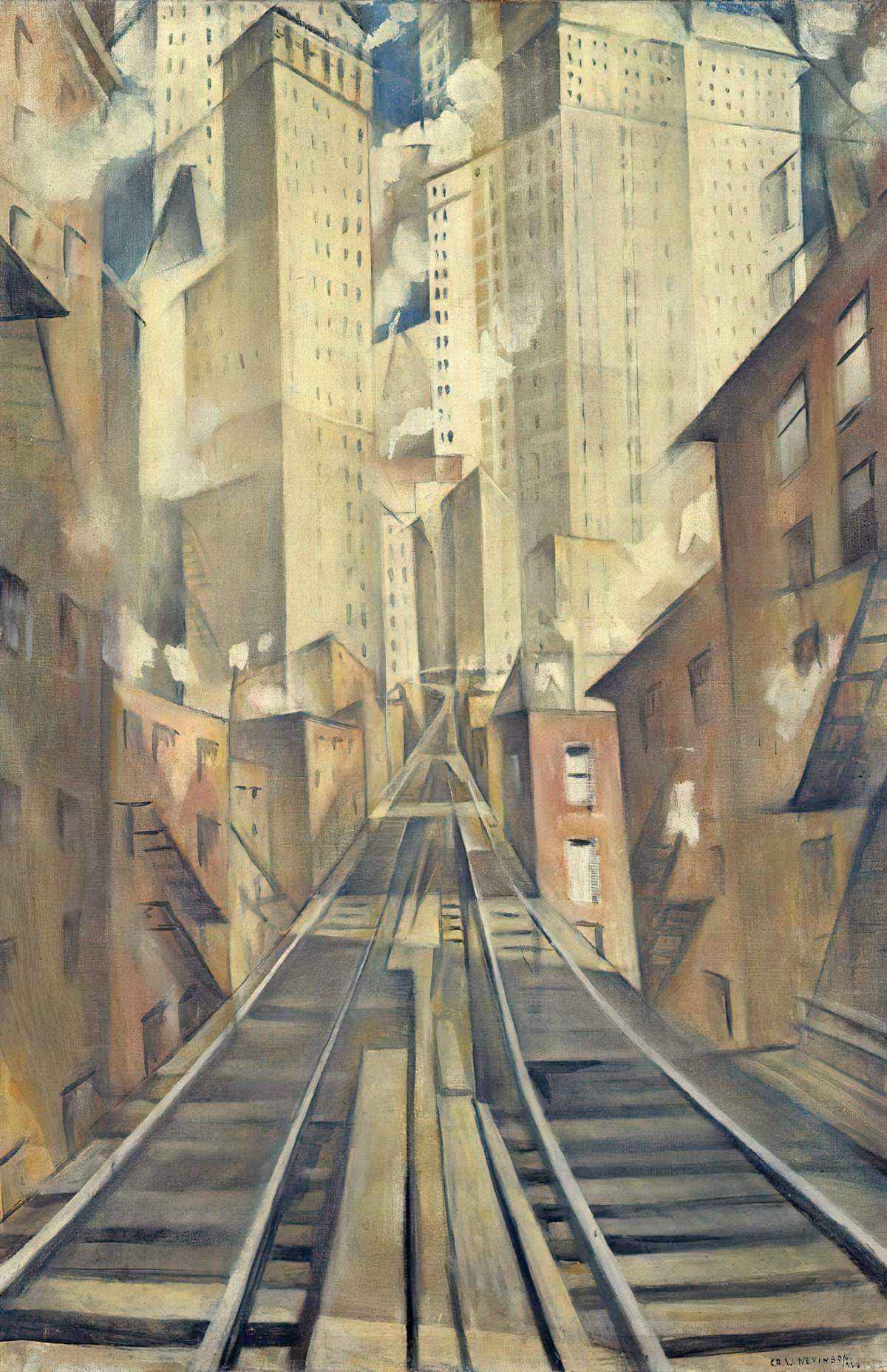

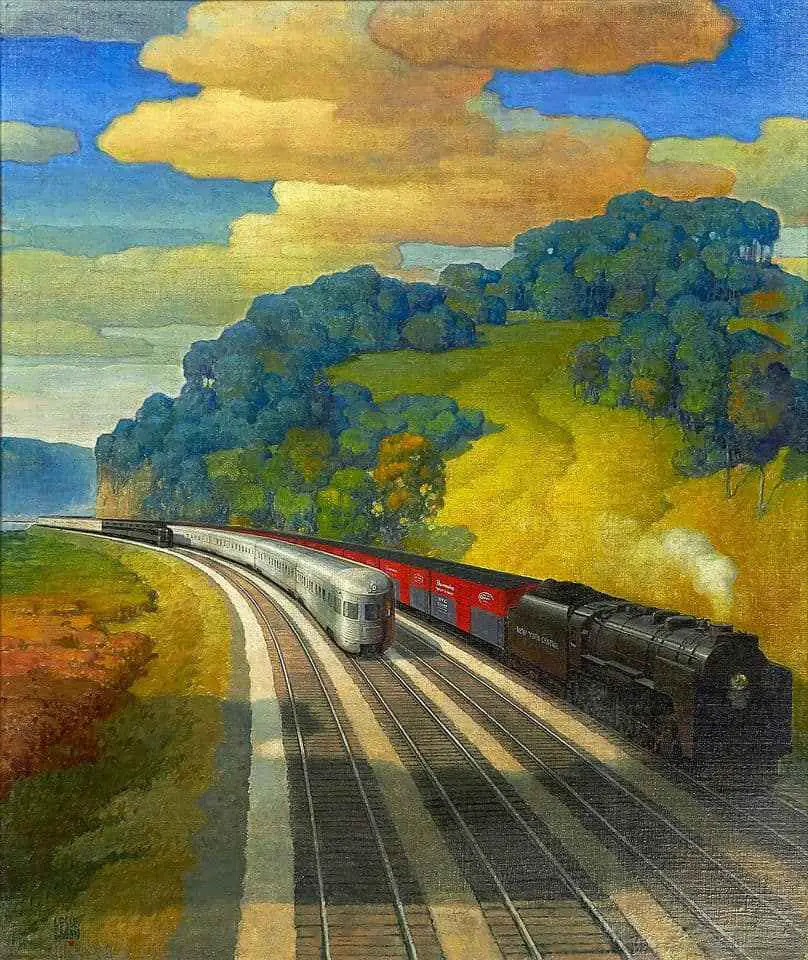

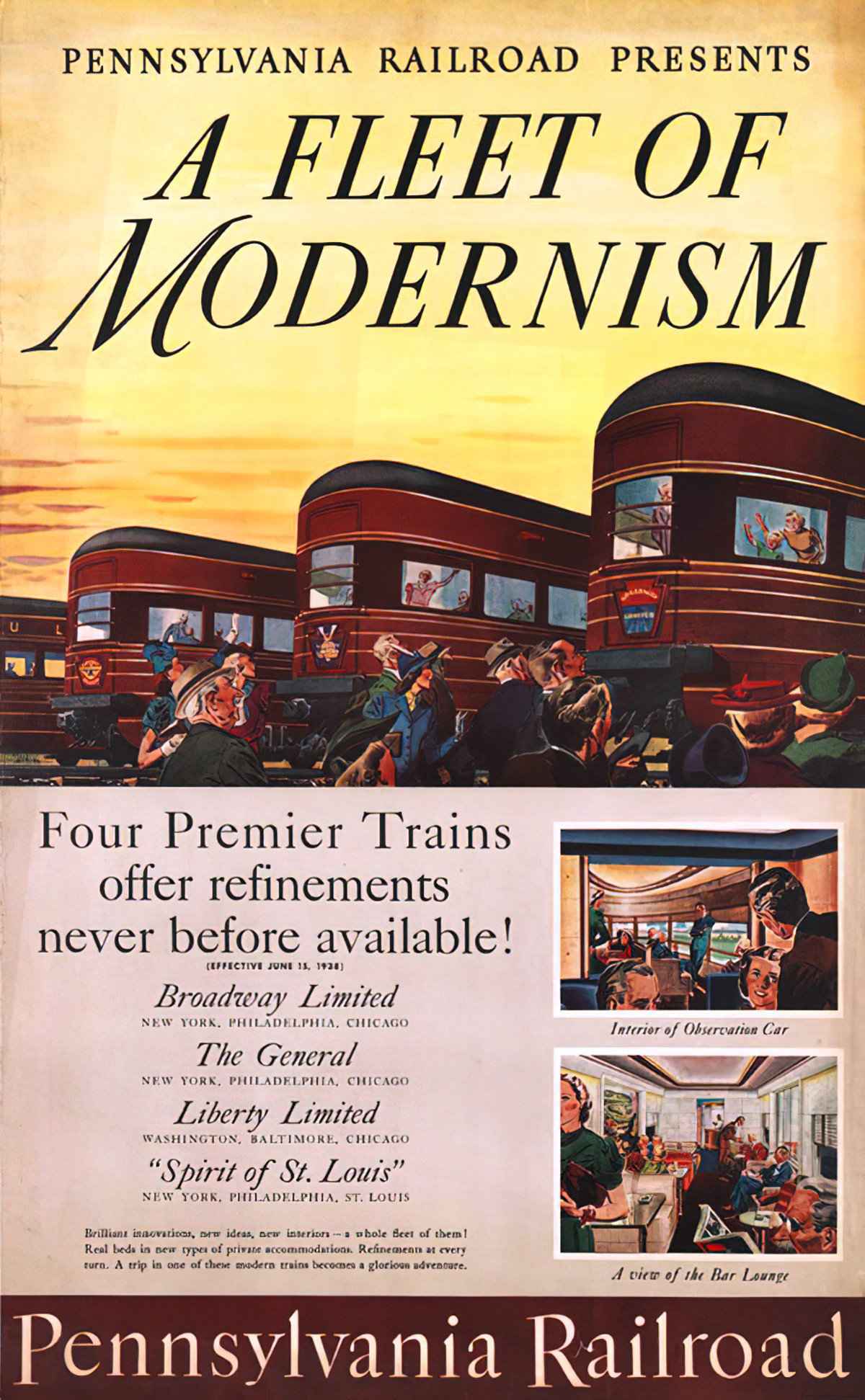

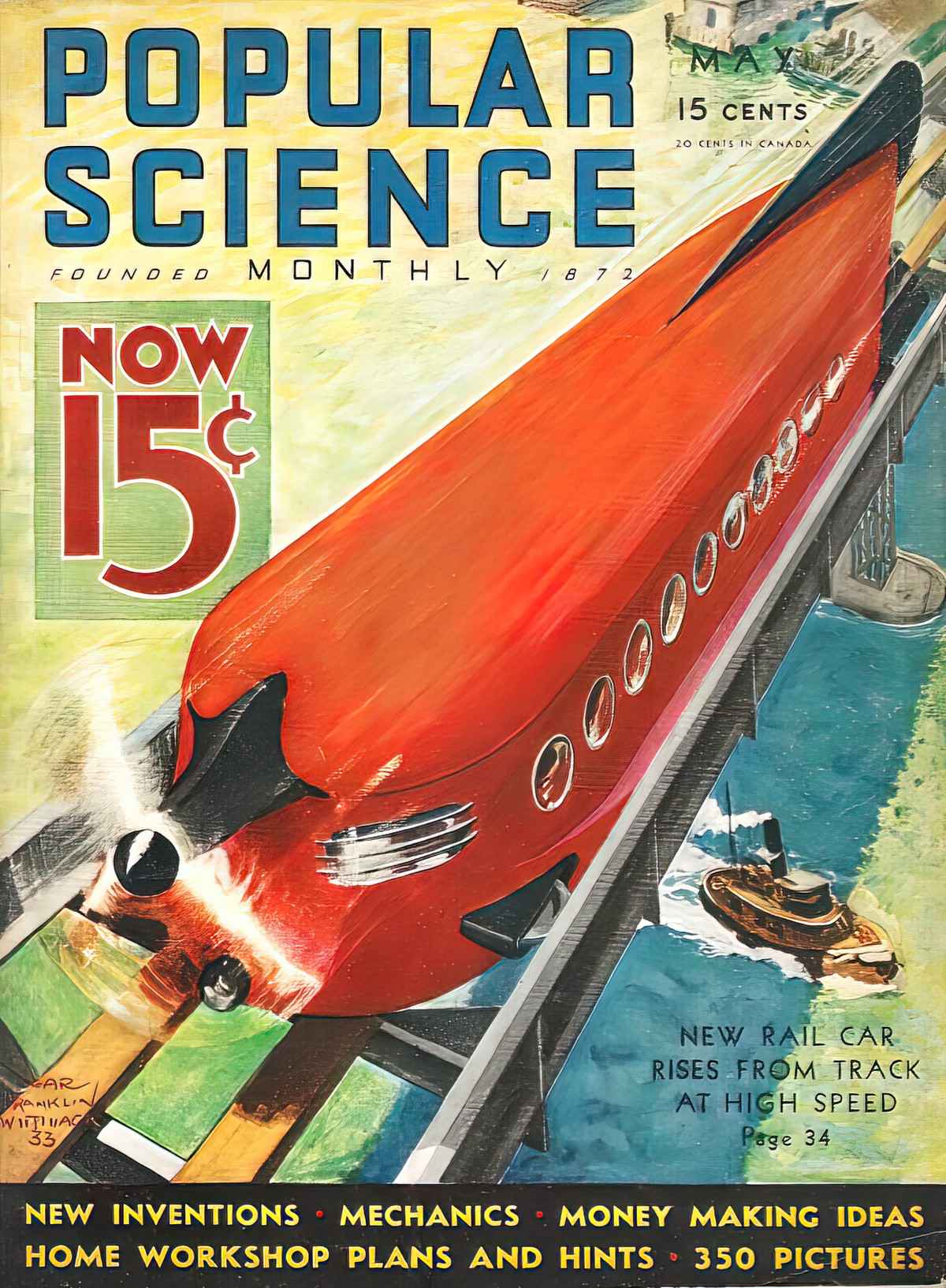

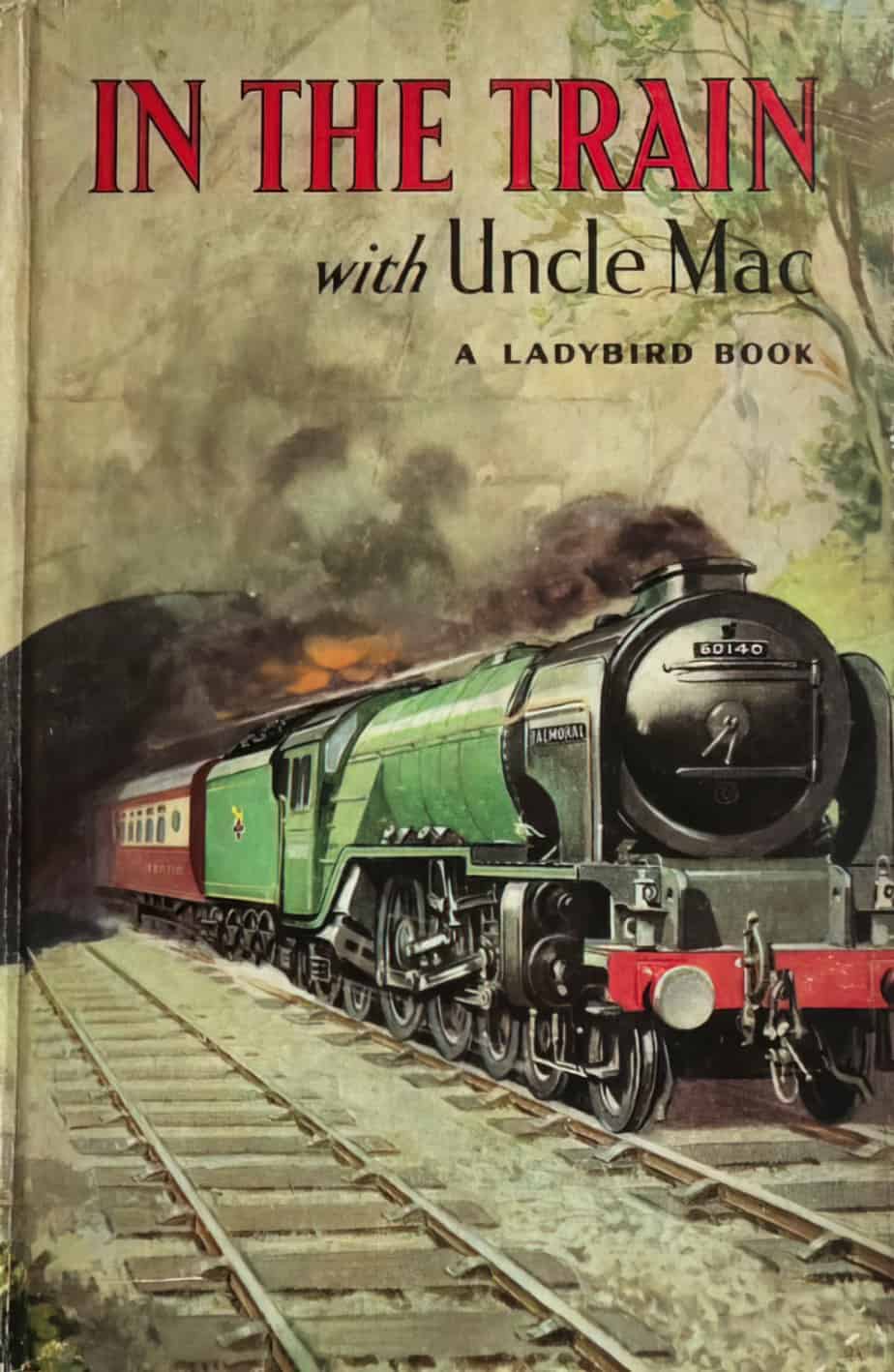

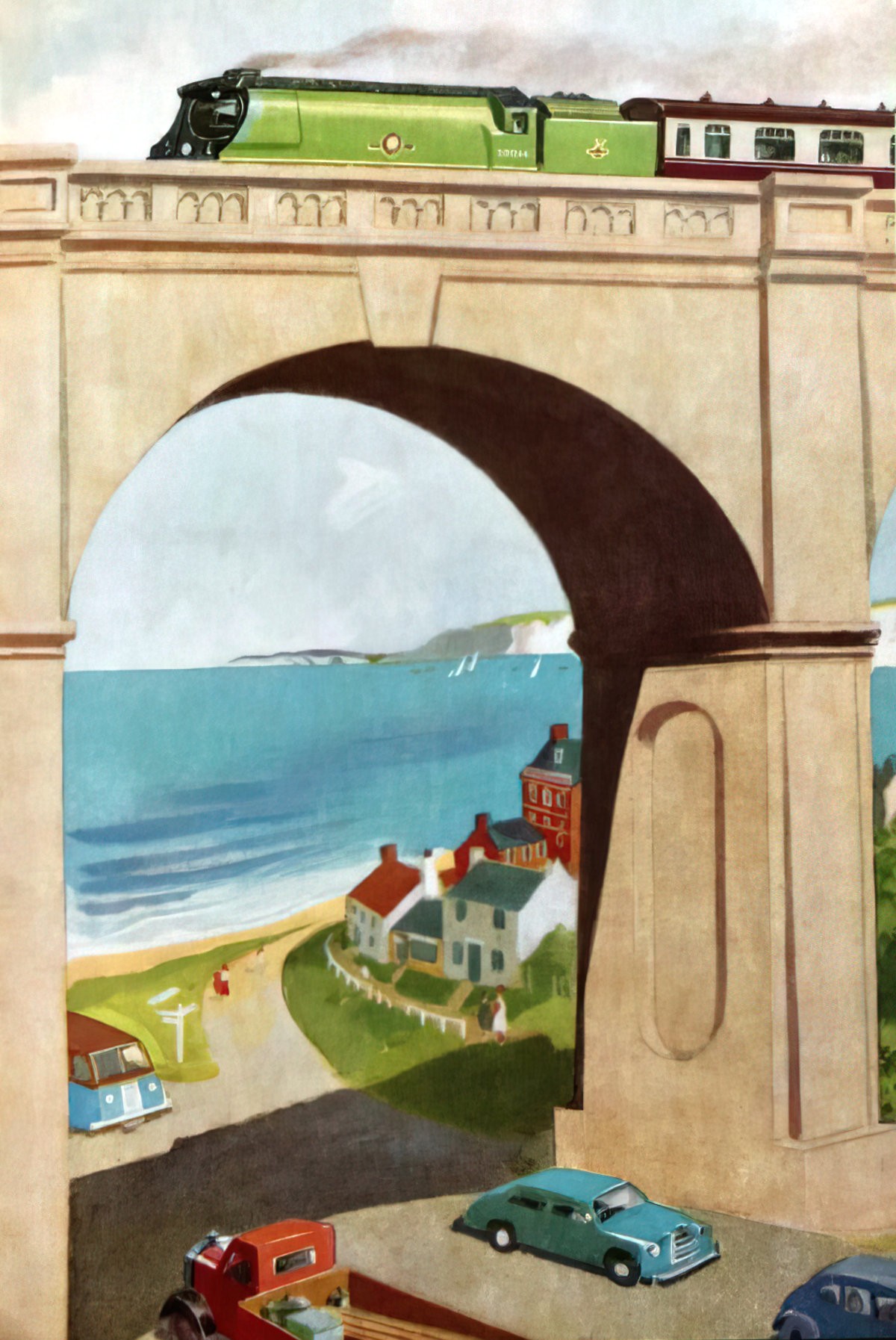

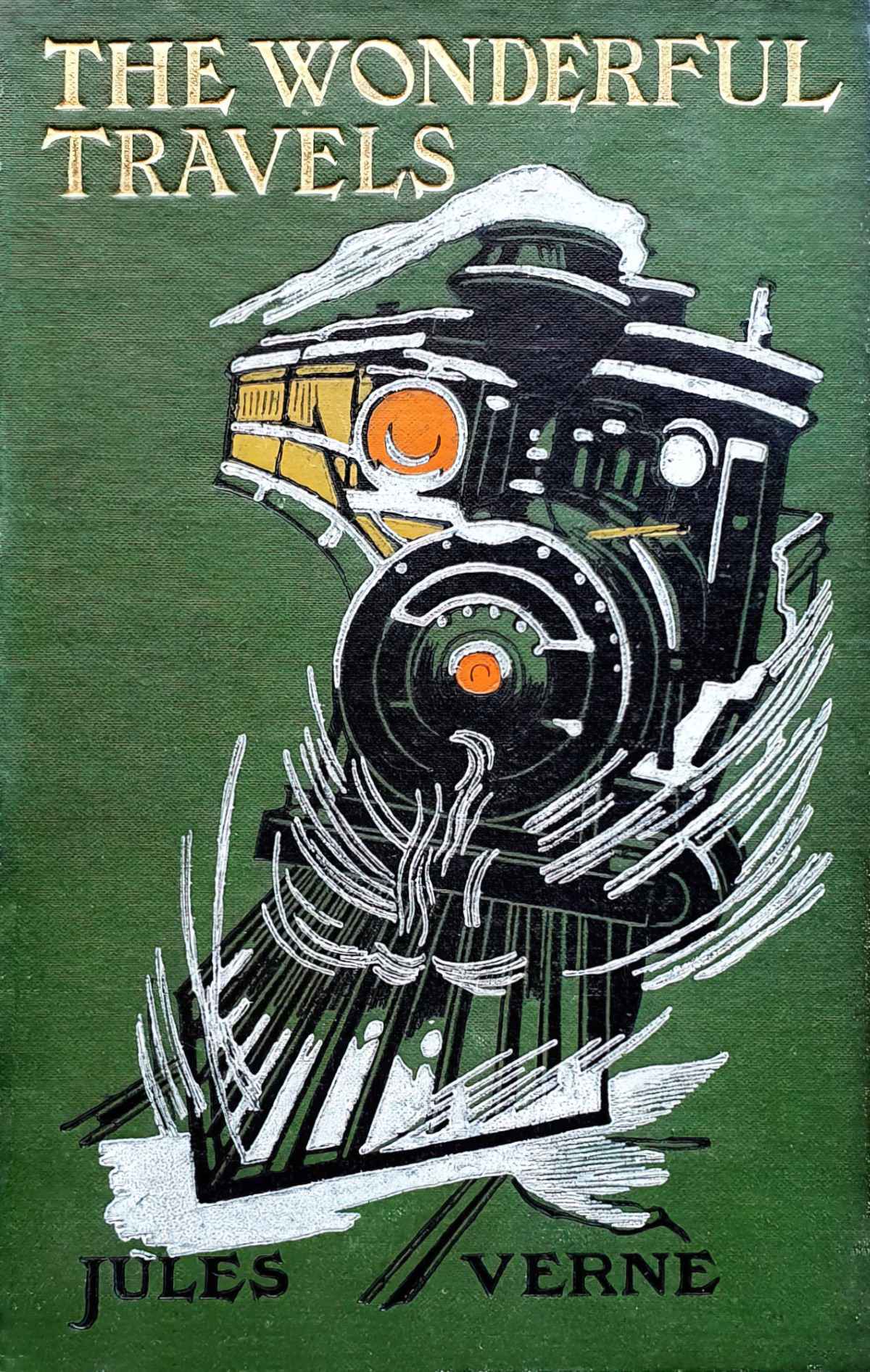

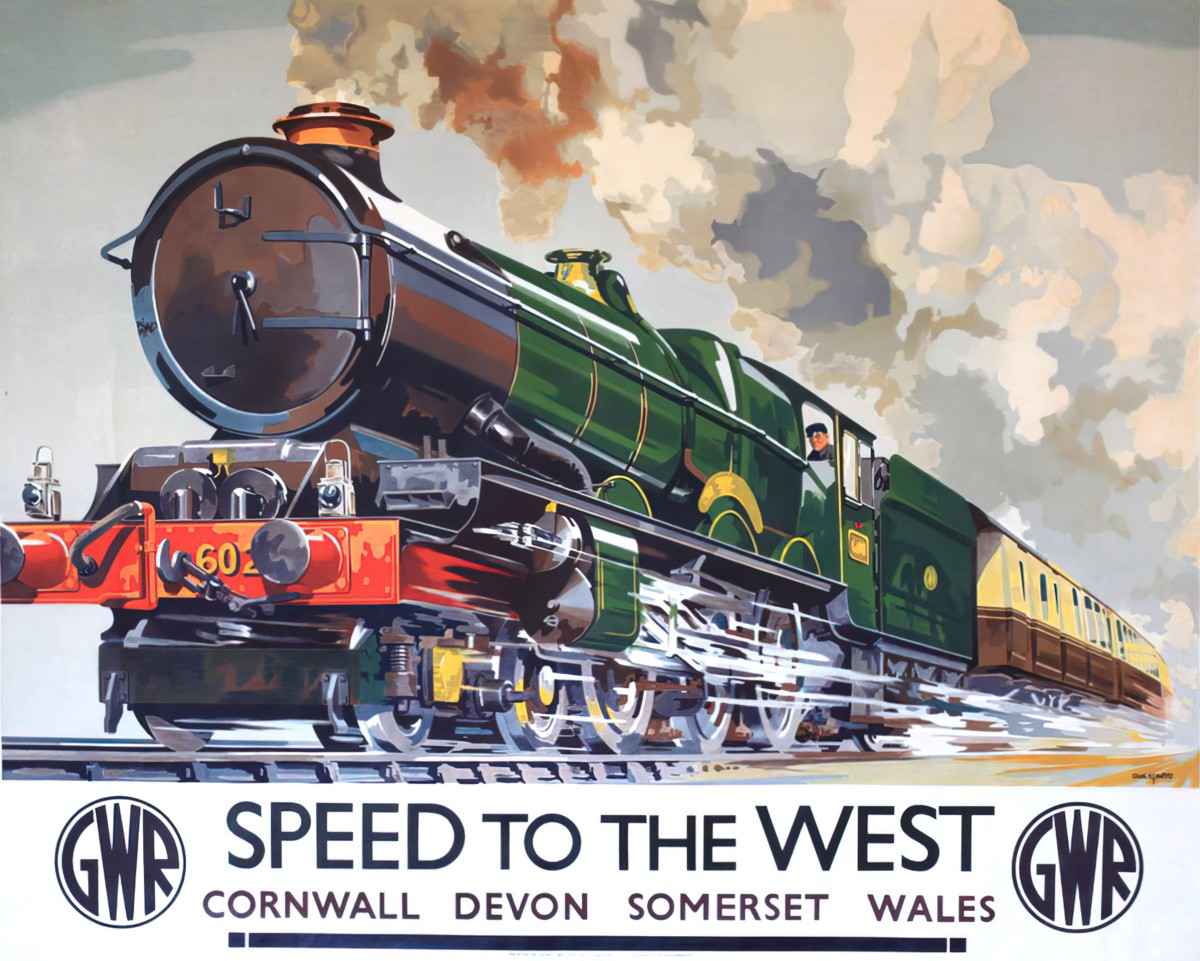

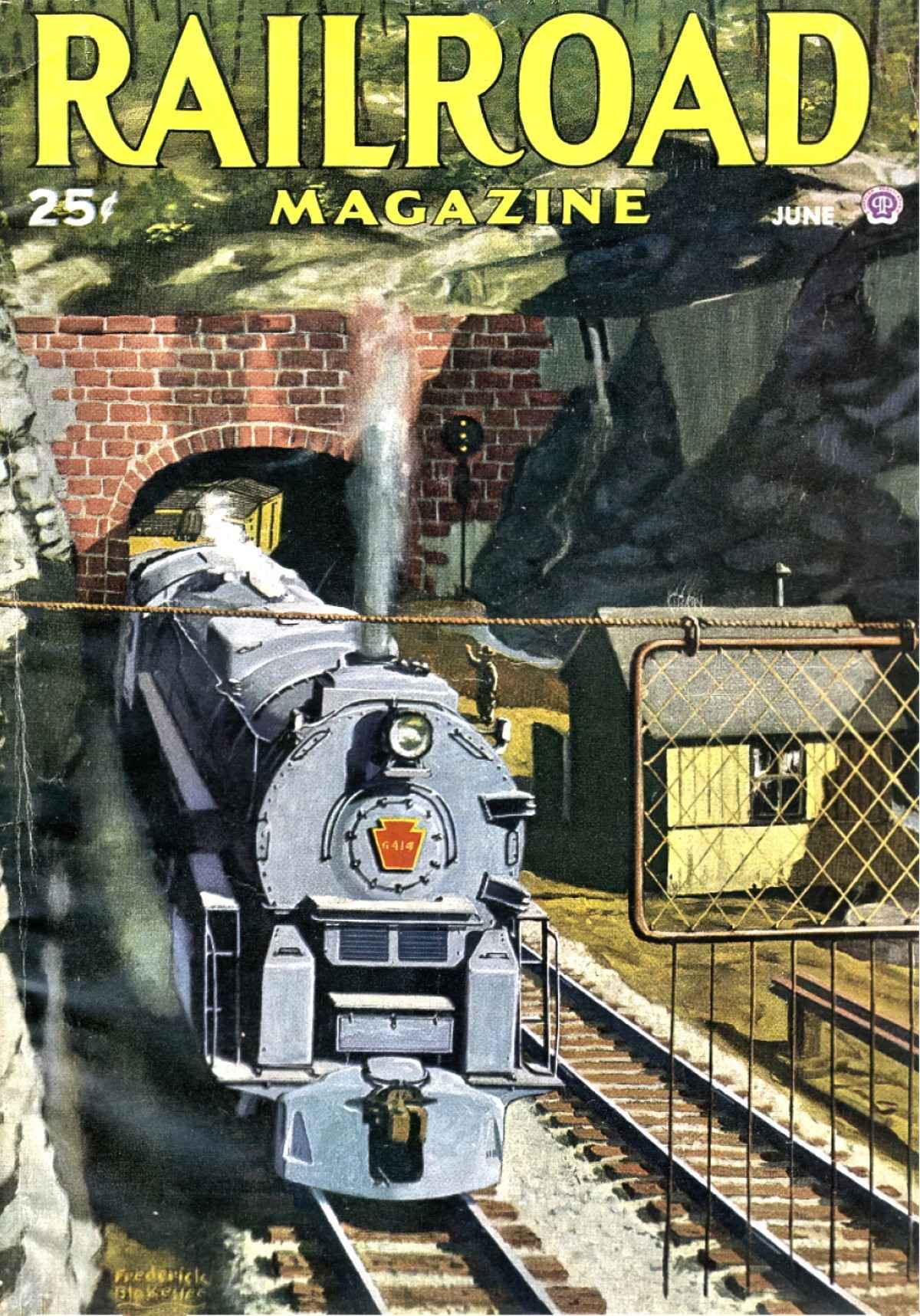

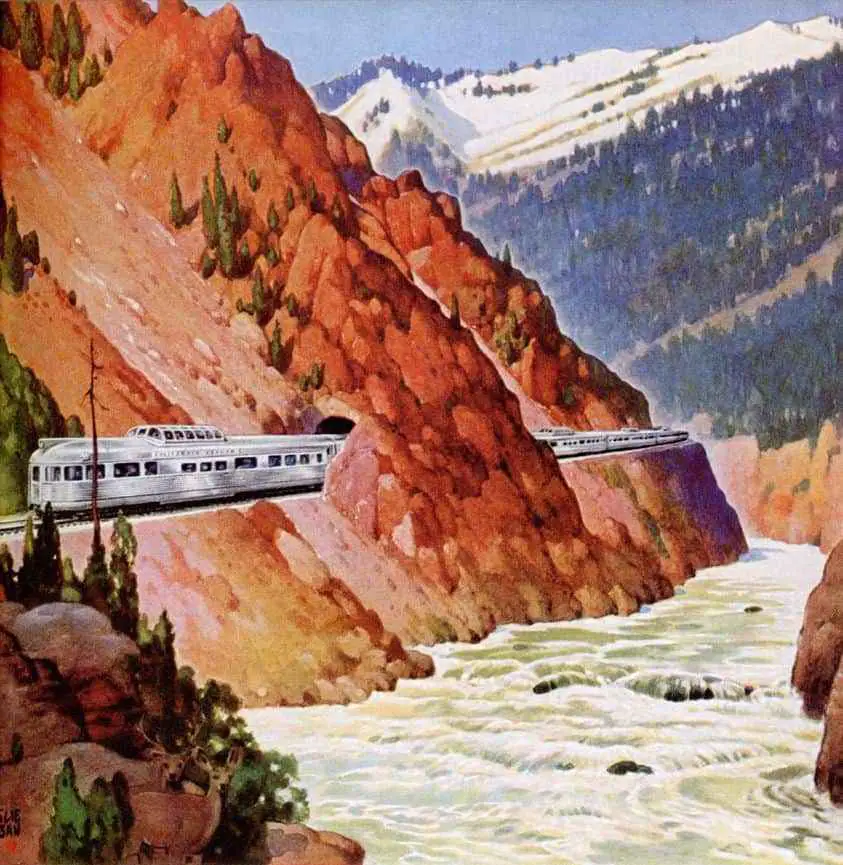

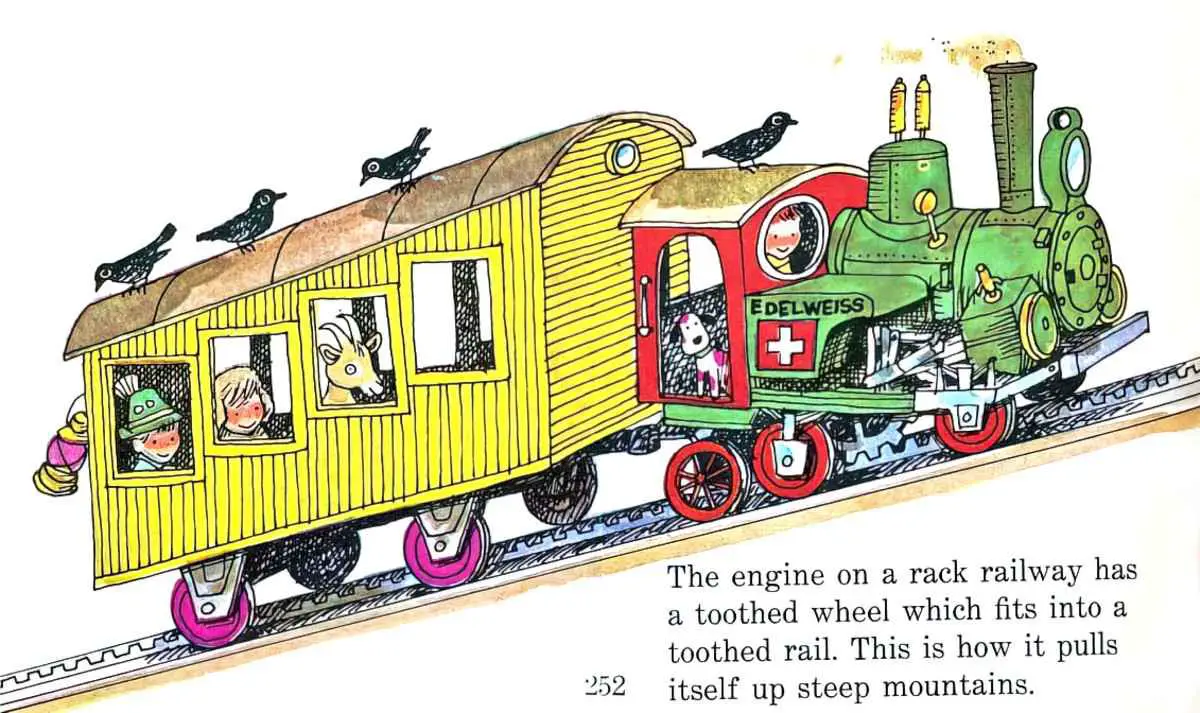

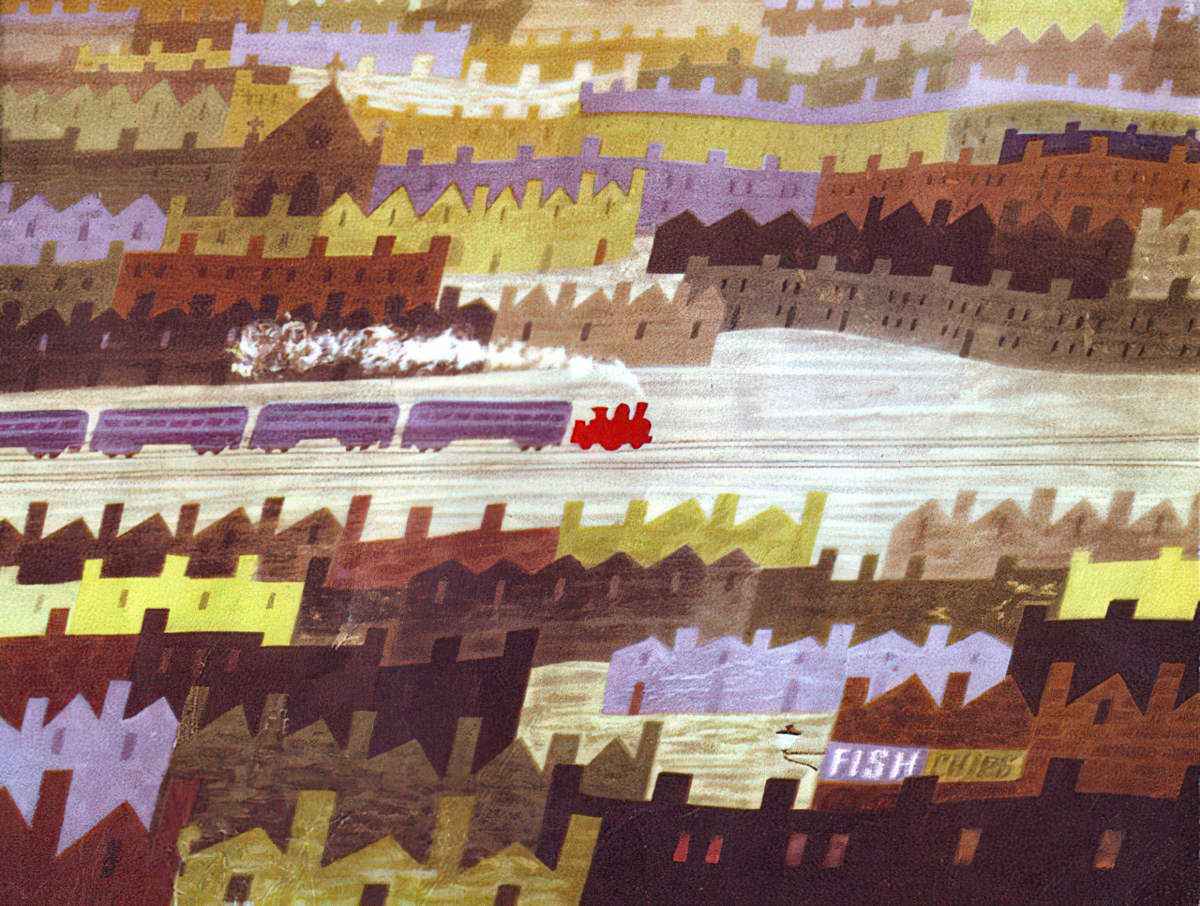

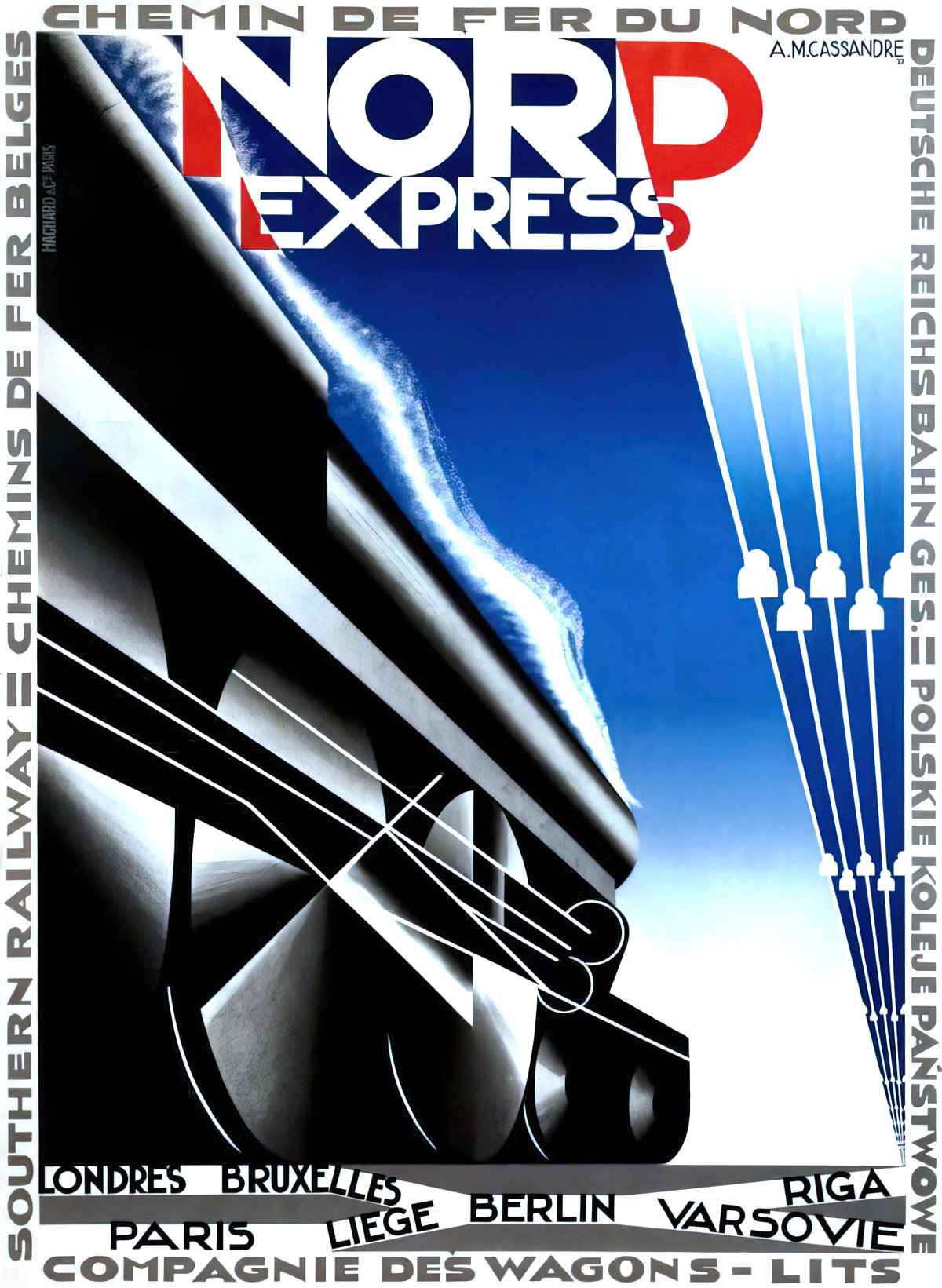

The classic poster art illustration below is from a time when three competing technologies of rail transport served as clear reminders of the rate of human progress.

When writing Dracula (1897), Bram Stoker wanted to make readers feel like vampires were living in their midst. For that, he had to utilise modern technology of the day. Characters move easily from place to place, sometimes making use of high-tech rail. For the same reason, characters communicate by telegram. Trains and telegrams felt futuristic at the time. Jonathan Harker’s fiancée Mina is even a trainspotter who has memorised train timetables. For Stoker, train travel was synonymous with modernity and technological progress, which still could not compete with the ancient evil of vampirism. Hence the horror.

The artist Leslie Ragan juxtaposes human technology against nature’s beauty.

Once Started, Can’t Be Stopped

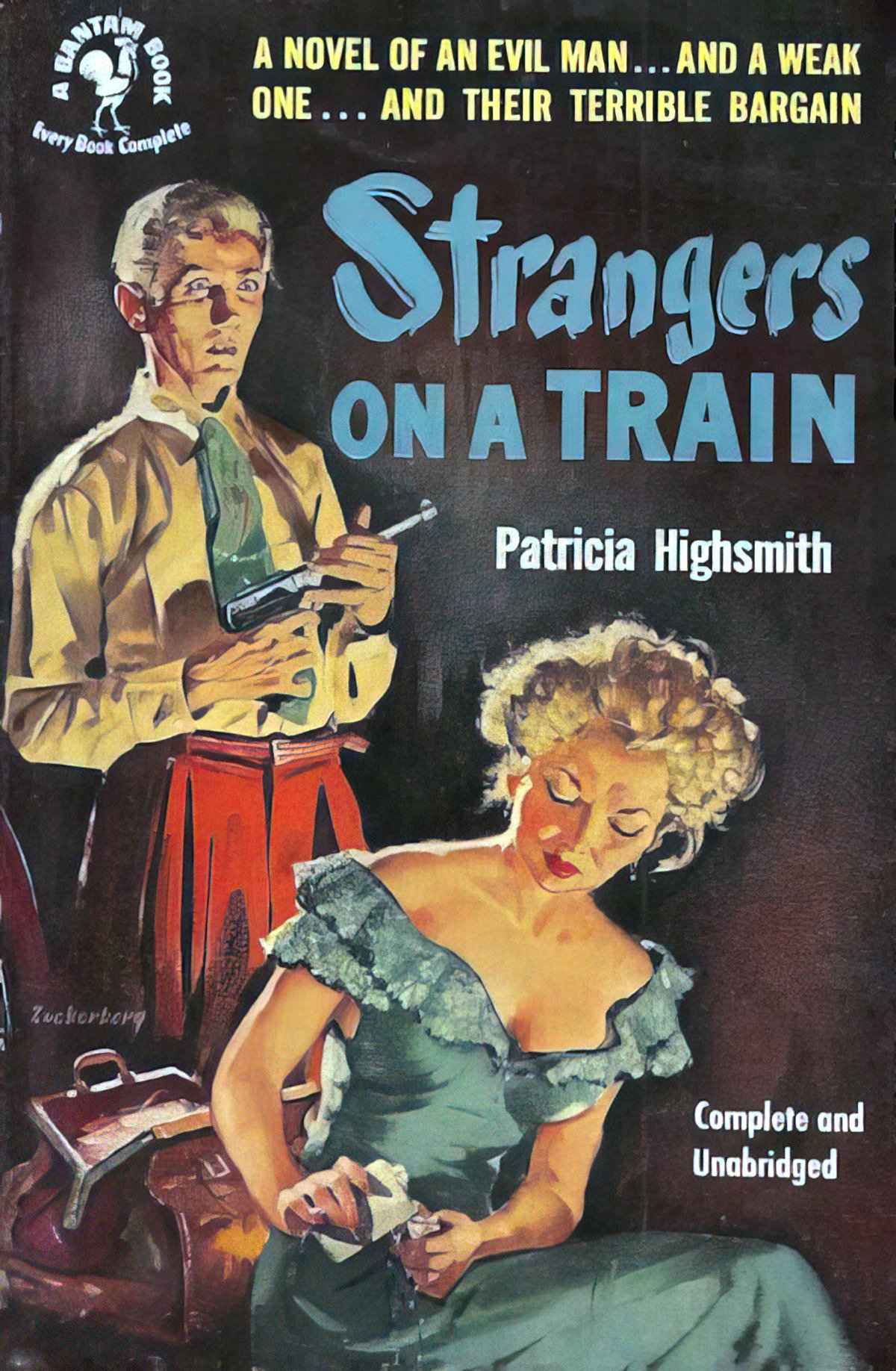

This symbolism is similar to the one above. It surely comes from the fact that trains are so huge they literally cannot be easily stopped. This is related to the idea of a butterfly effect — or fatalism — in which certain events trigger further events, and even if we change our mind partway through a plan, the damage has already been done.

Runaway train never going back

“Runaway Train“, Soul Asylum

Wrong way on a one way track

Seems like I should be getting somewhere

Somehow I’m neither here nor there

Patricia Highsmith utilised this aspect of trains in her psychological suspense story Strangers On A Train.

Guy Haines and Charles Anthony Bruno are passengers on the same train. Haines is a successful architect in the midst of a divorce, Bruno a mysterious smooth-talker with a sadistic proposal: he’ll murder Haines’s wife if Haines will murder Bruno’s father. As Bruno carries out his twisted plan, Guy finds himself trapped in Highsmith’s perilous world, where, under the right circumstances, ordinary people are capable of extraordinary crimes. The inspiration for Alfred Hitchcock’s classic 1951 film, Strangers on a Train launched Highsmith’s prolific career, proving her a master at depicting the unsettling forces that tremble beneath the surface of everyday life.

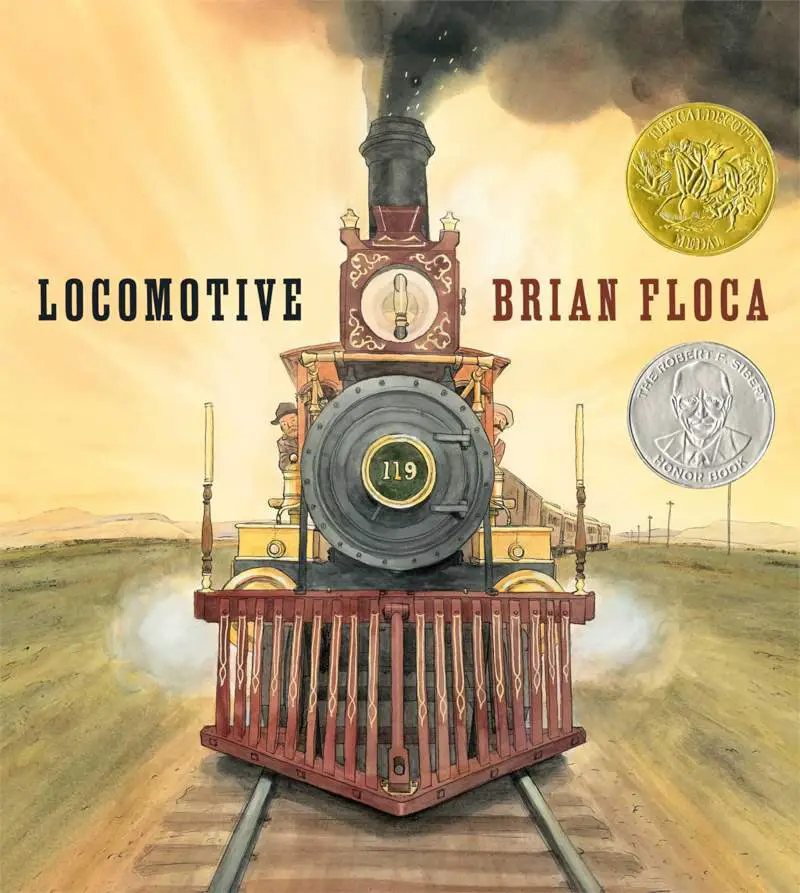

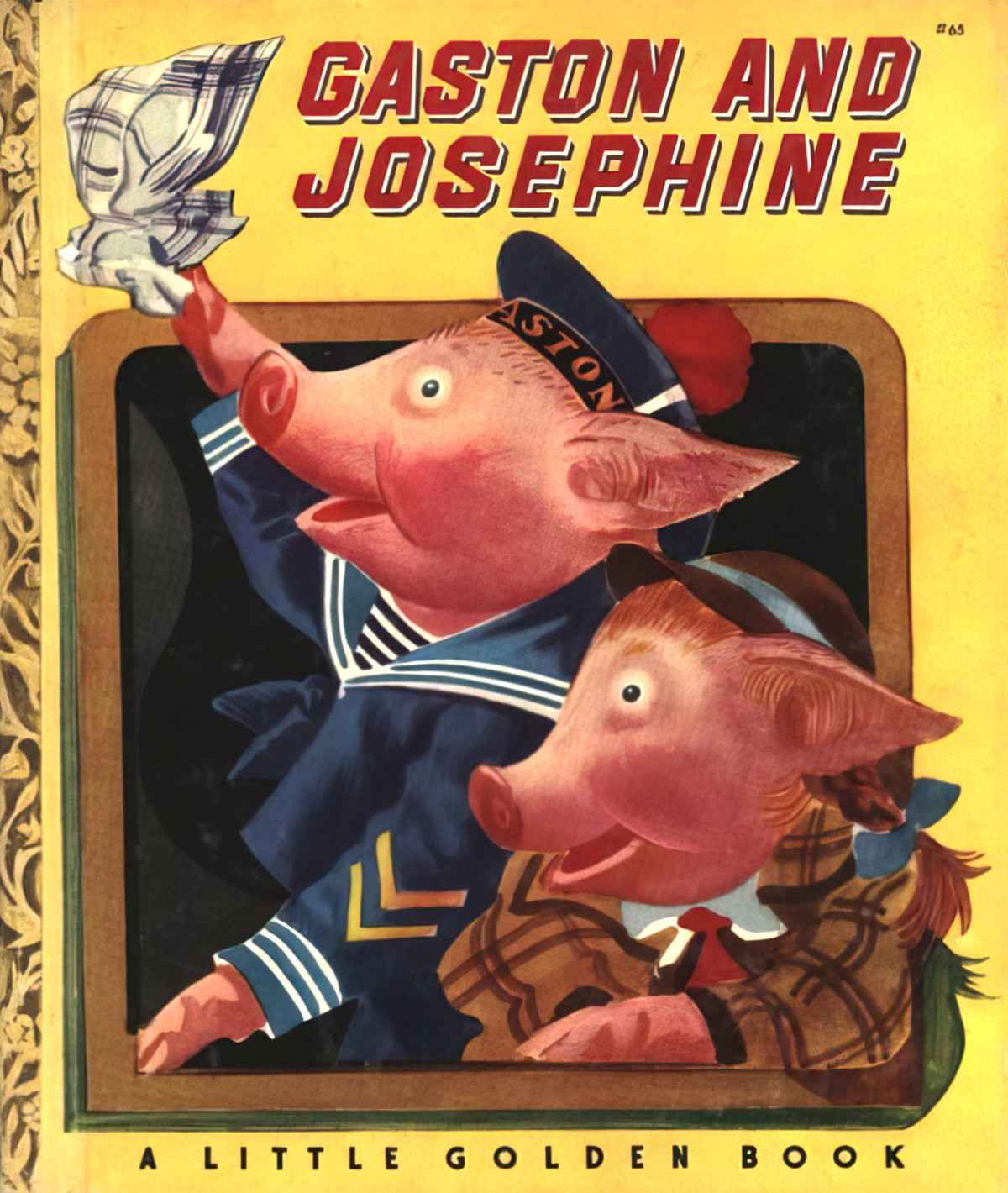

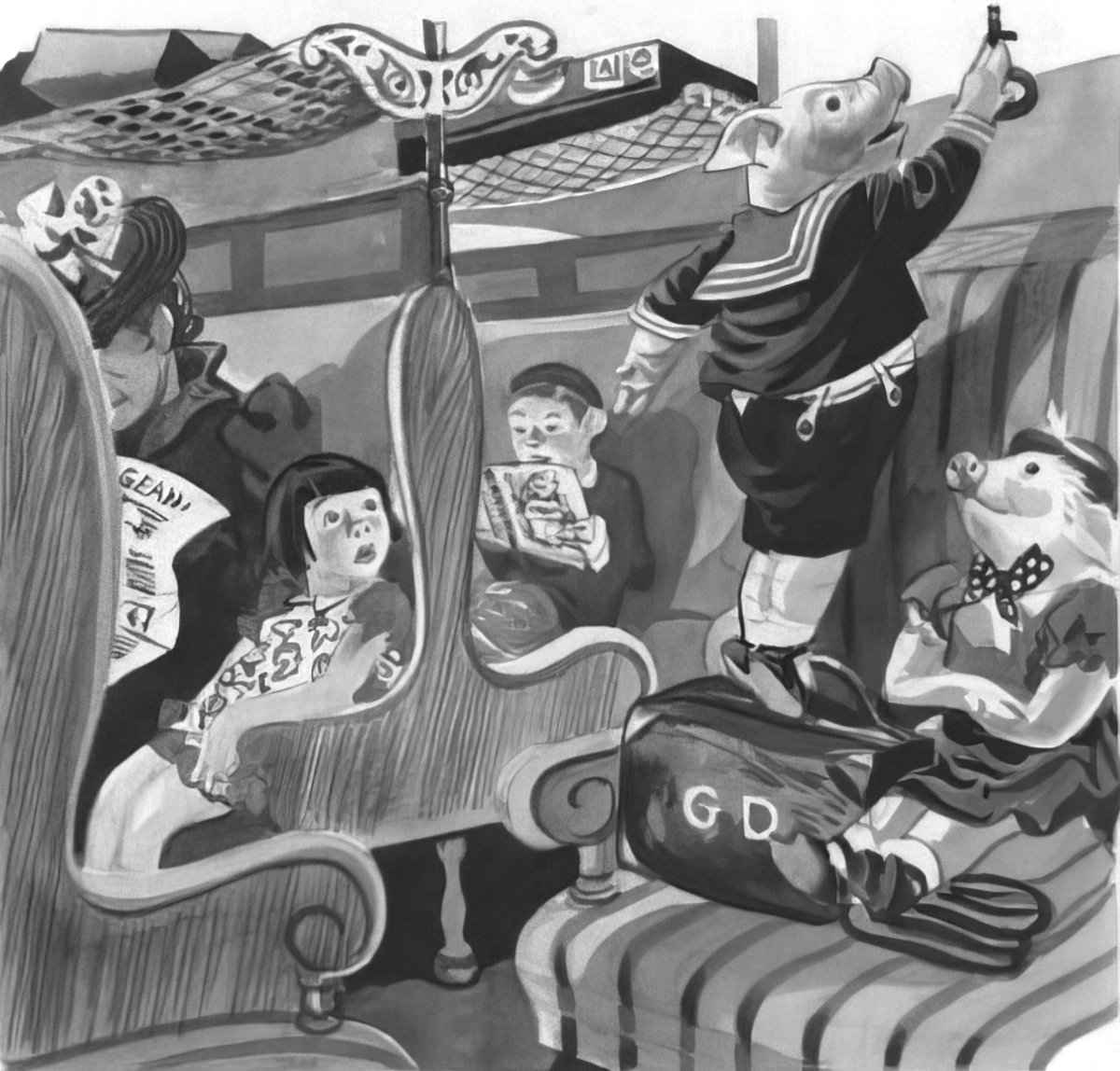

Trains In Utopian Fantasy For Children

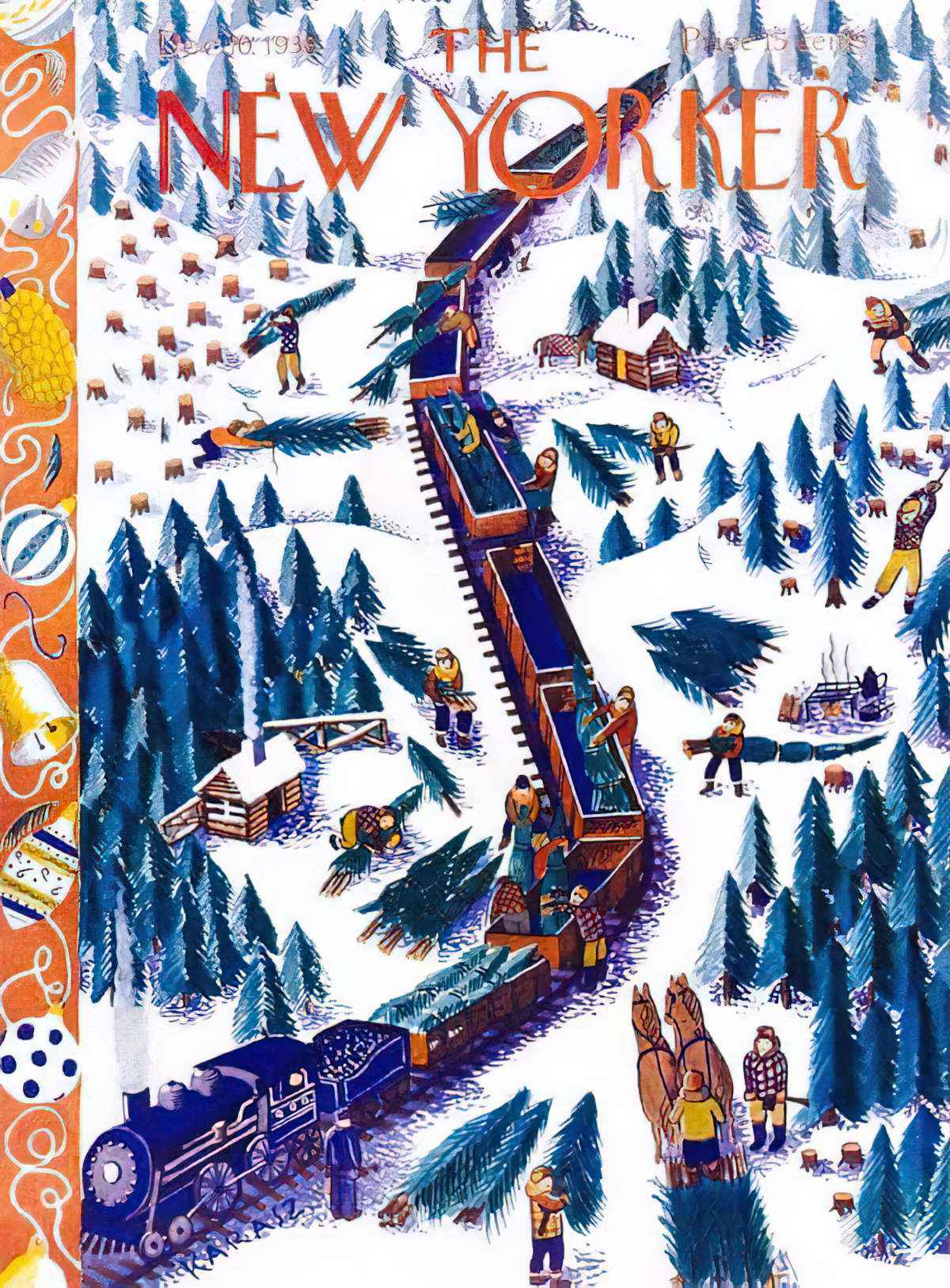

Train illustrations for Gaston and Josephine, 1933. The handkerchief waved from a train window is a recognisable motif.

Trains have been hugely important in children’s literature in particular.

Train journeys occur at initiatory or climactic moments of large numbers of classic children’s utopian fantasies; in these journeys, the railway functions as a protean, paradoxical space, not merely instrumental but instead active. Long after it vanished from the landscapes of the real world as a functional means of transport, the steam train in particular continues to feature in works of fantasy aimed at children, operating by laws often unlike those of the realms through which it passes, and providing a space for the dramatisation of spiritual and emotional adventure. […] Railway journeys serve an important role within the metaphorical as well as the narrative economy of utopian texts; this role is sometimes a subversive one, and ultimately calls into question the relationship of reader to text.

Railway trains in utopian fantasy literature operate like alternative worlds, allowing space and time within the narrative for establishment, subversion, and clashing of the logics and values of the other realms of the text. In this way they can be described in terms of Foucault’s well-known formulation of “heterotopia“. […]

Utopian and Dystopian Writing for Children and Young Adults, edited by Carrie Hintz, Elaine Ostry

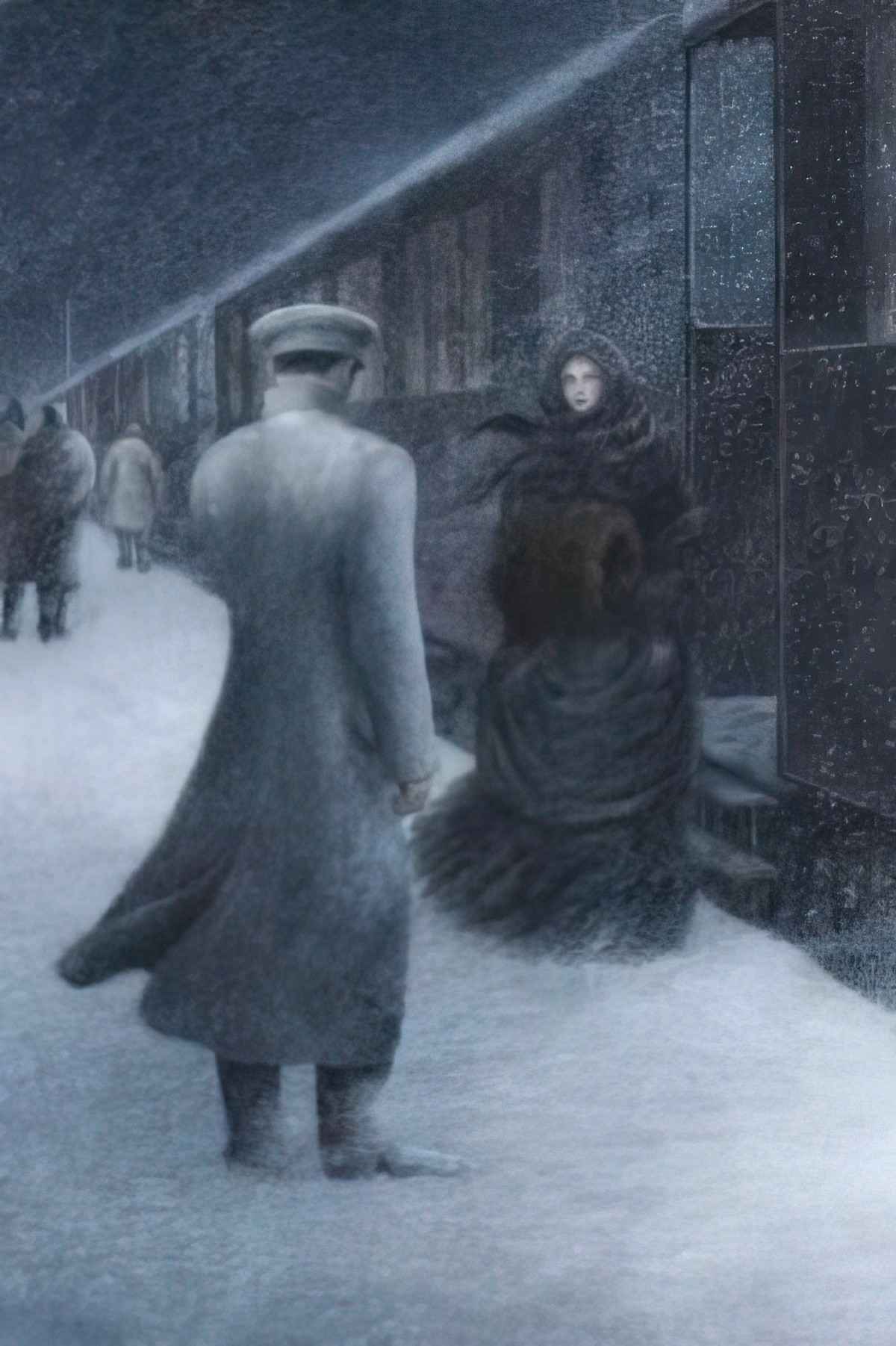

Train Stations As Beginnings and Endings (Hellos and Goodbyes)

The train station as a place of beginnings and endings is seen in many stories. One especially memorable train station for me is that depicted in Anne of Green Gables.

For a younger generation of readers, it is often the train of Harry Potter which resonates.

The train station platform functions identically to the bus station platform. You can probably think of many resonant scenes set in train and bus stations. A bus station marks the end of a student-teacher relationship in Mr Holland’s Opus. A bus station makes the end of a housekeeper’s employ with a problematic man in Hud. There is also the strong feeling of regret at what could have been in another parallel life. Symbolically, these platforms are functioning as crossroads.

Another resonant parting of ways (largely inaccessible to young viewers because of its uniquely adult emotion — regret with no hope) is the train station scene in The Remains of the Day.

That sense of the ‘parallel’, imagined life that could have been is perhaps why trains (and express service buses, which travel along their own invisible, pre-laid tracks) lend themselves to well to stories in which we’re encouraged to consider fate, and our own hand in it.

Trains As Temporary Home

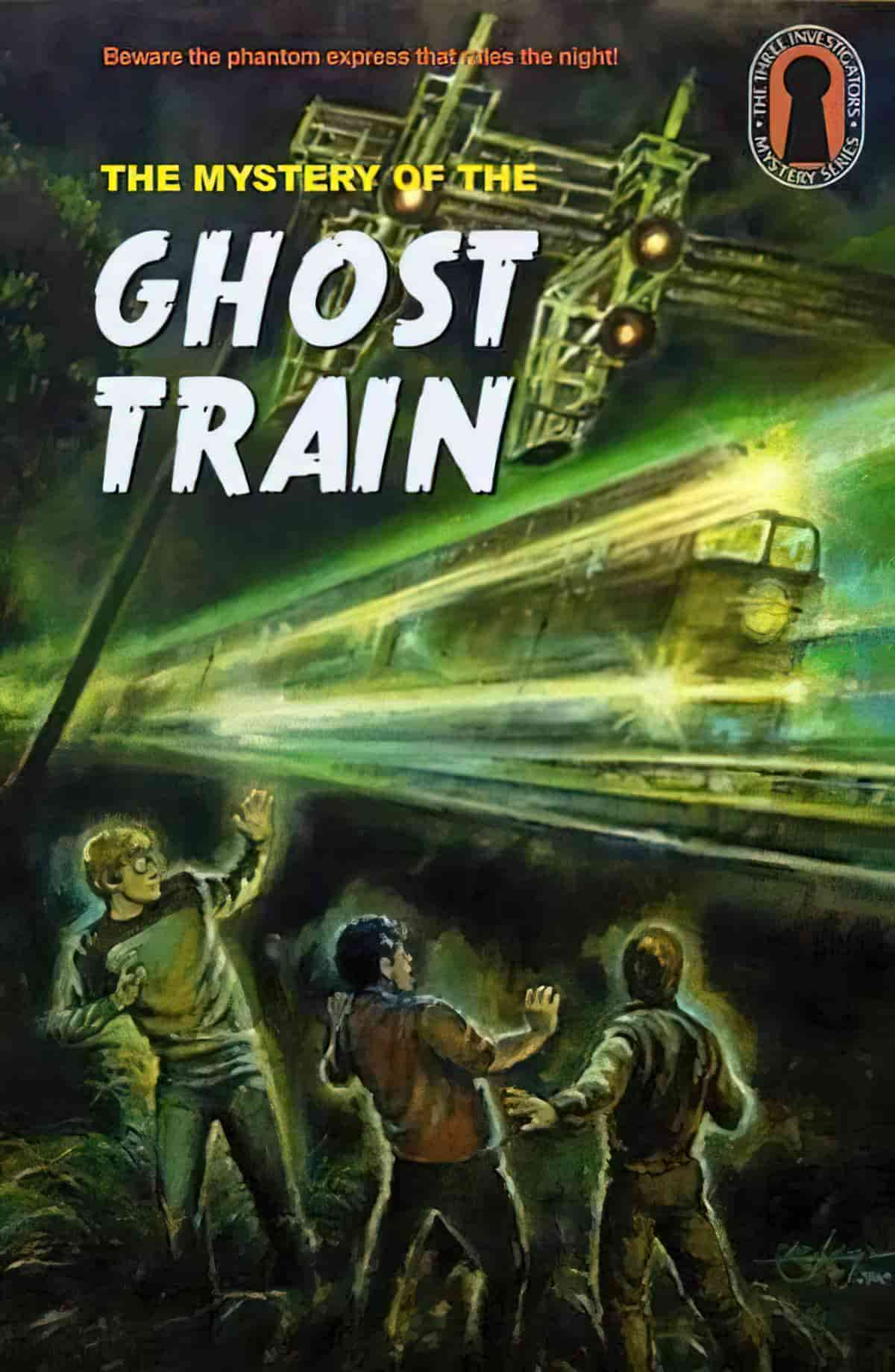

Ghost Trains

Like motels, trains are a little bit like home, but not your home. They therefore fall into the uncanny valley of home, and we can’t help but think of all the other people who have been in our seat before us and after us.

Jupiter Jones, Bob Andrews and Pete Crenshaw win a radio contest for tickets on The Ghost Train, a passenger train traveling from Los Angeles to New Orleans over a 6 day period with a promise that passengers will “see the ghosts of the dead men found in the locomotive!”. As it is summer, they get permission to travel unaccompanied just as long as they agree to obey the train personnel.

The trip begins inauspiciously with a badly-performed disappearance of the rear locomotive, and seems to go downhill for the boys after that.

See also: “The Ghost Train” by Arnold Ridley, a BBC dramatized production of the short story, broadcast 24 January 1988.

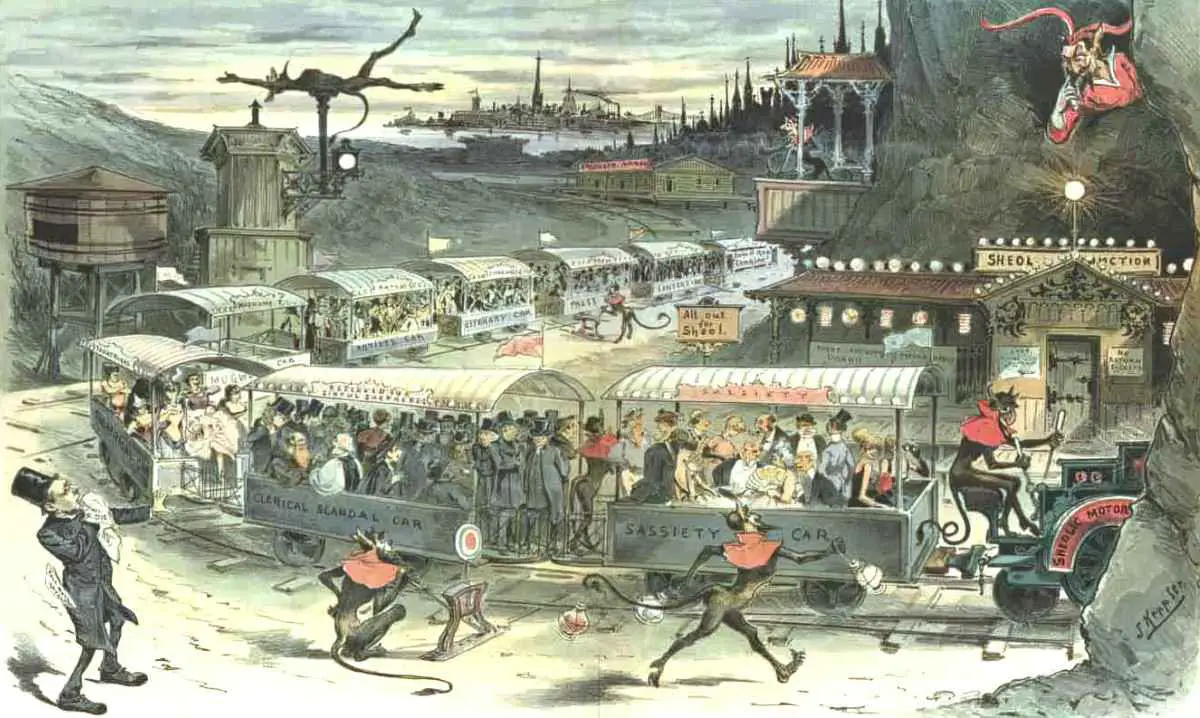

Trains As Contra-Symbol

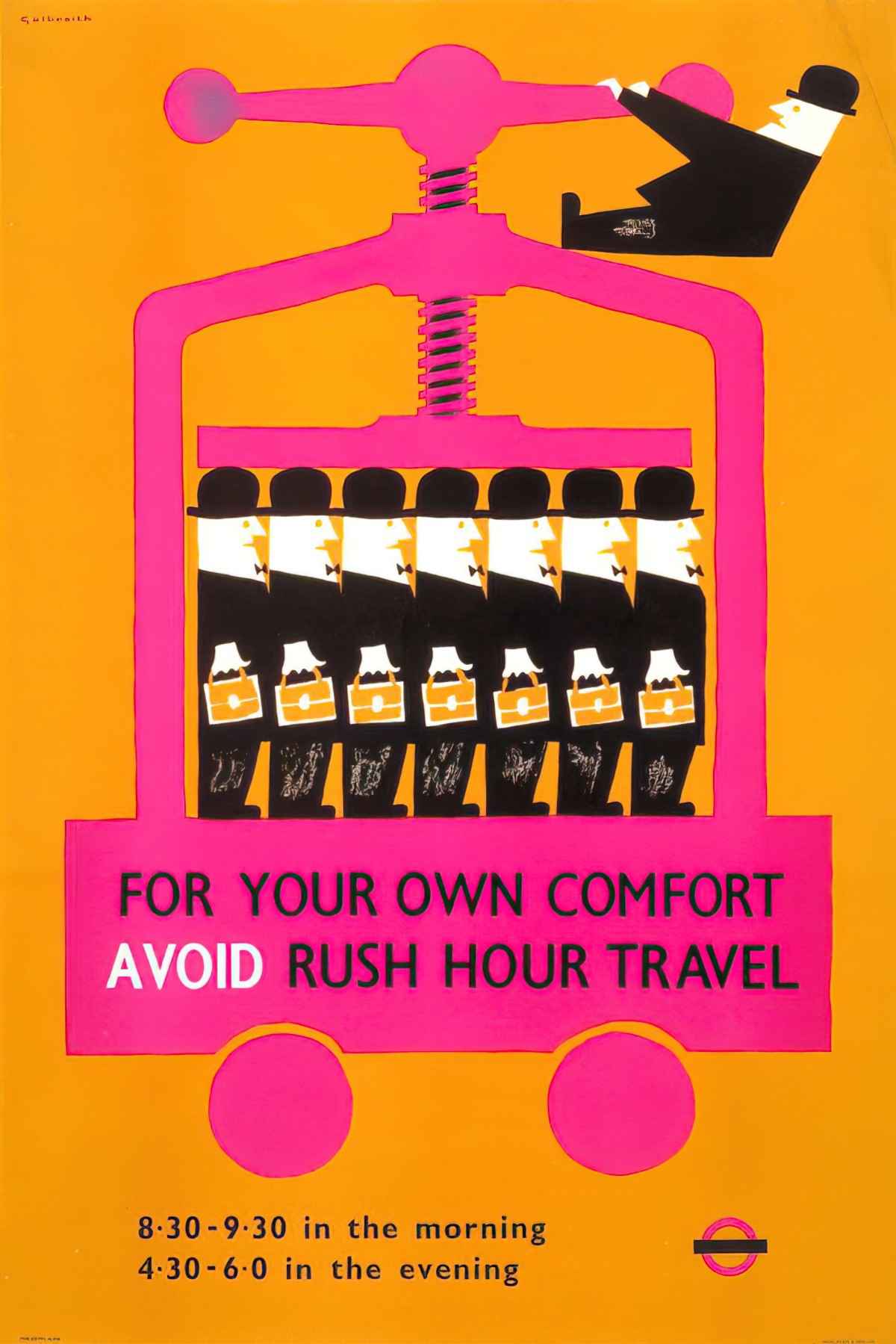

The symbolism of a train can be milked any which way by a storyteller. The train can feel at once oppressive but also afford freedom. The best example of this contradiction in action is perhaps Japan.

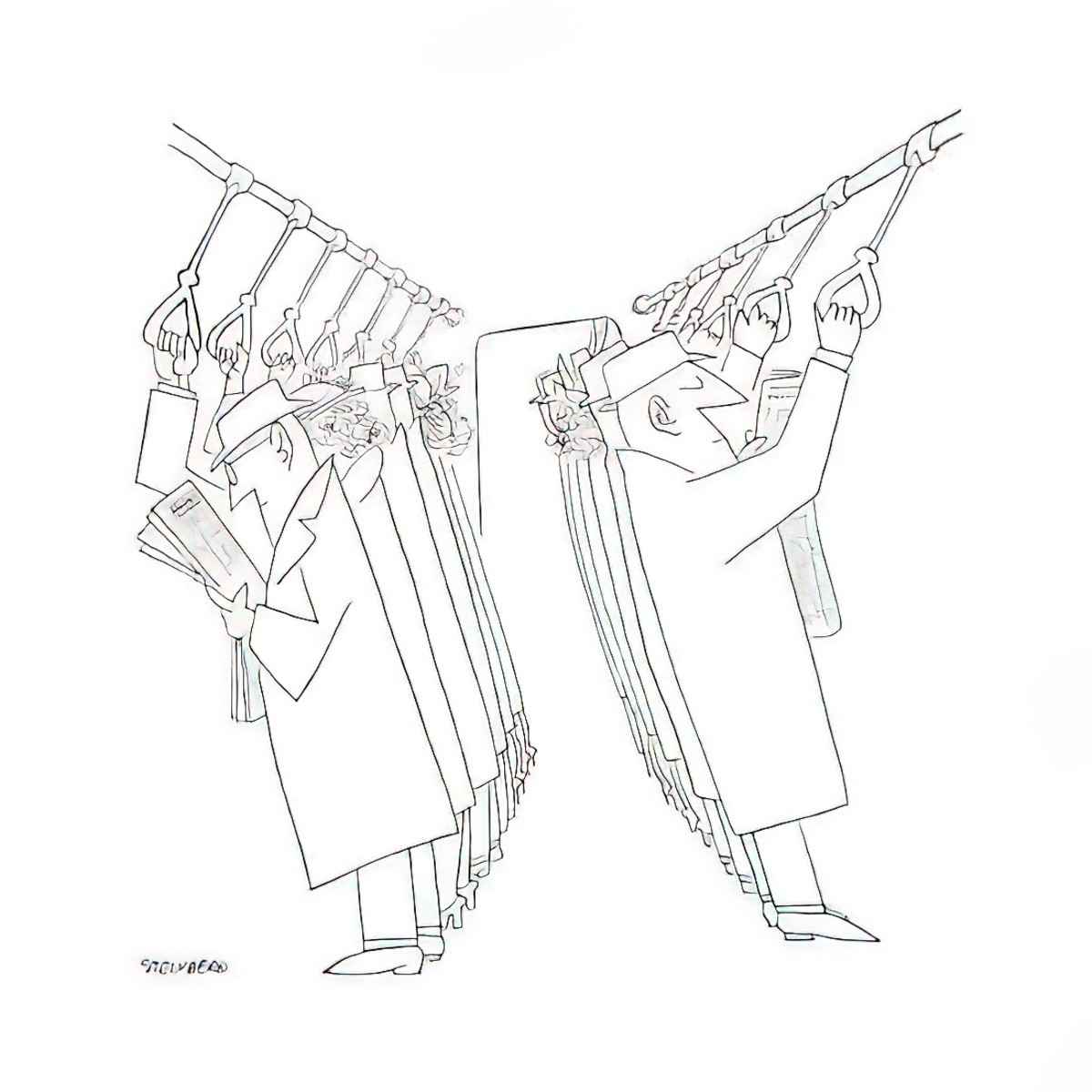

Trains are a huge part of Japanese life and are also a huge part of Japanese storytelling, perhaps especially in manga culture. Japan is famous (infamous?) for its pushers, but pushers also existed in New York:

In the early 20th century, New York subways actually had attendants, colloquially called “sardine-packers,” to physically cram people in. The Japanese famously employed uniformed, white-gloved “shiri oshi” — meaning “tushy pushers” — to do the same during rush hour. A pusher in Tokyo told The Times in 1995, “If their back is toward us, it’s easier, but if they’re facing us, it’s harder because there’s no proper spot to push them, though we try to push their bags or something else they are holding. In any case, we always first say, ‘We will push you.’” Once the trains left the station, the attendants used long, hooked poles to recover shoes and other items that had fallen on the track. Said another pusher, back in 1964, “I really wonder how so many of those girls manage to go to work with one shoe.”

NYT

Trains are thereby seen as oppressive, but also afford Japanese children a freedom Western children rarely have — the train network is so reliable, so crowded and easily navigated that children are often trusted to ride trains without adult caregivers in a way I wouldn’t see here in Australia.

For passengers inside, trains are a safe form of travel. But in Japanese towns and suburbs, trains travel regularly across your path, and you must stop at the gate and the lights. The threat of death is near. All you’d need to do is disobey the signs.

This low-level fear is utilised in The Girl Who Leapt Through Time. The way a train hurtles unstoppably forward is at symbolic odds with the fact that, should you stand in front of it, your life comes to an immediate halt. Symbolically, you’ve now got this juxtaposition between how an individual’s life ends suddenly but the world continues on.

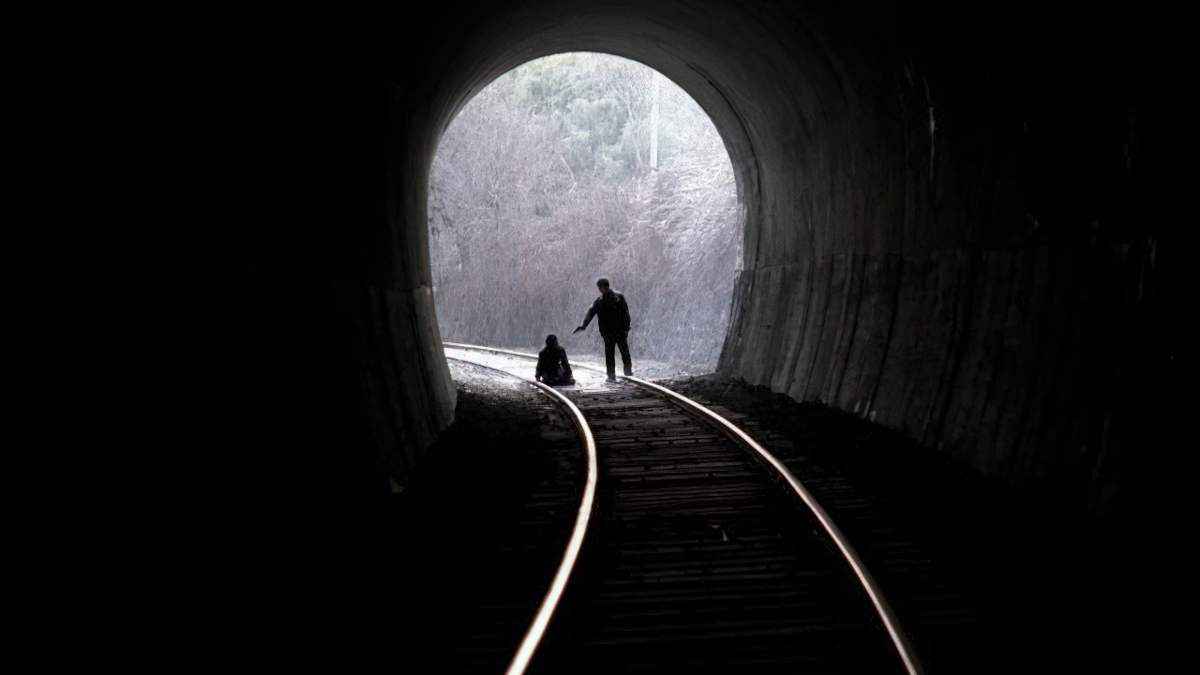

The image of the body tied to a train track reminds us that trains are in fact dangerous, if you’re near the tracks. When characters walk down the tracks our blood pressure rises a little. The audience doesn’t know when a train is about to turn up.

See: The Train Scene in Stand by Me (YouTube)

The trailer of 5 Centimeters Per Second shows us that almost the entire film (comprising 5 interconnected short stories) takes place in trains and train stations.

Trains As Dangerous Monsters

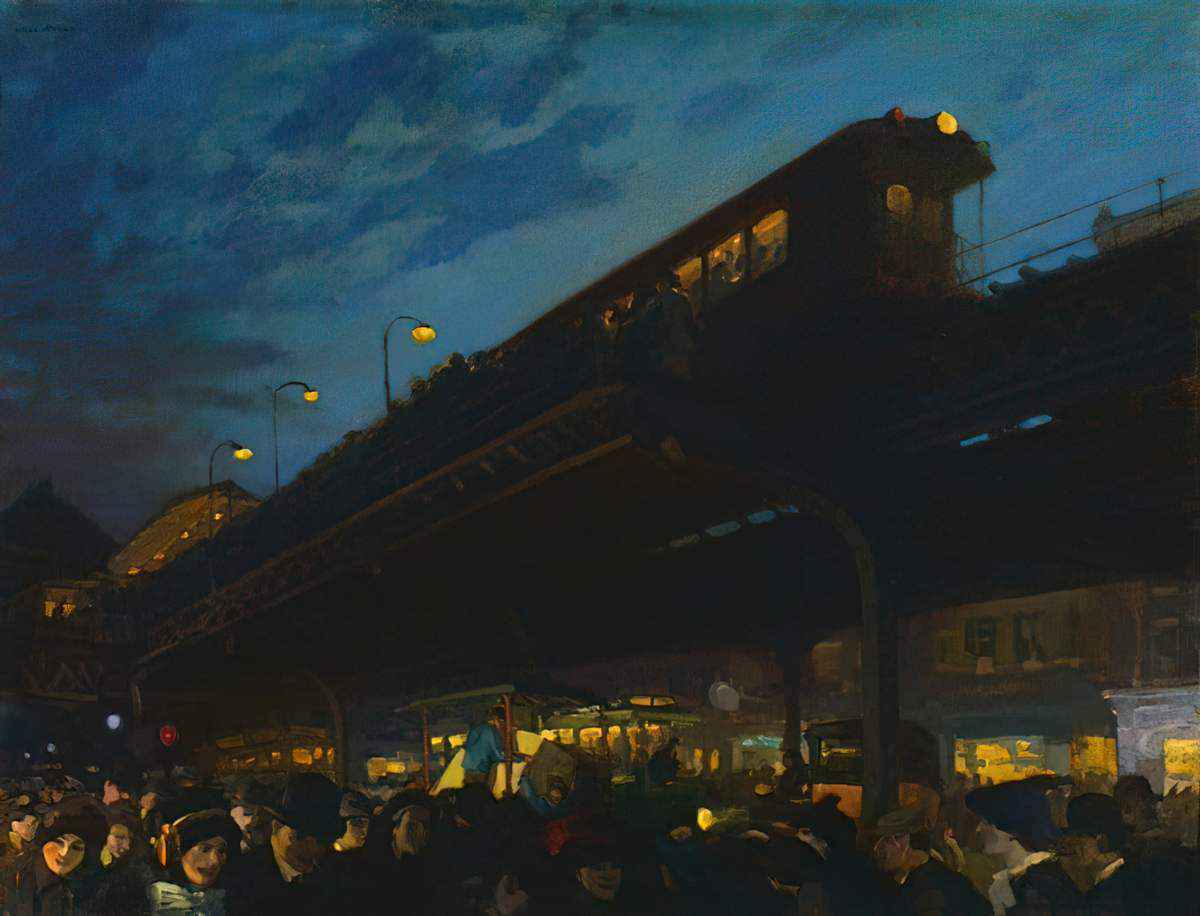

Sometimes trains seem like dangerous monsters because they travel above us, on elevated tracks.

But trains can also feel menacing and ominous when we see them from worm’s eye view.

For passengers, trains are one of the safer forms of transport. But trains pose a danger for anyone crossing their path. Like a mechanical horror monster who just won’t stop, a train literally can’t stop at short notice.

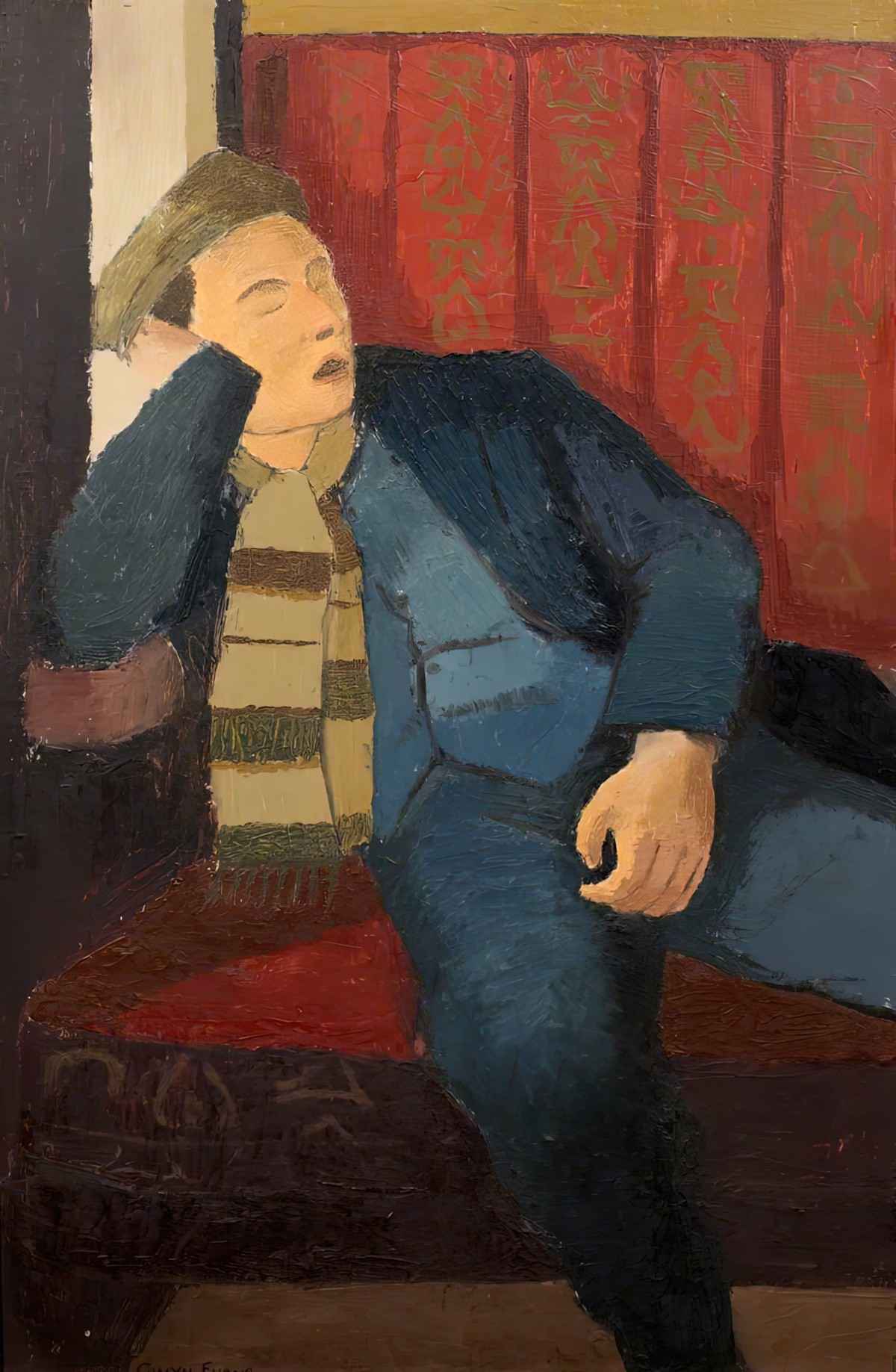

Trains As Loneliness, Though Surrounded By People

The worst kind of loneliness is when you’re surrounded by people. On a crowded train, etiquette dictates we avoid others’ gaze, don’t speak unless necessary.

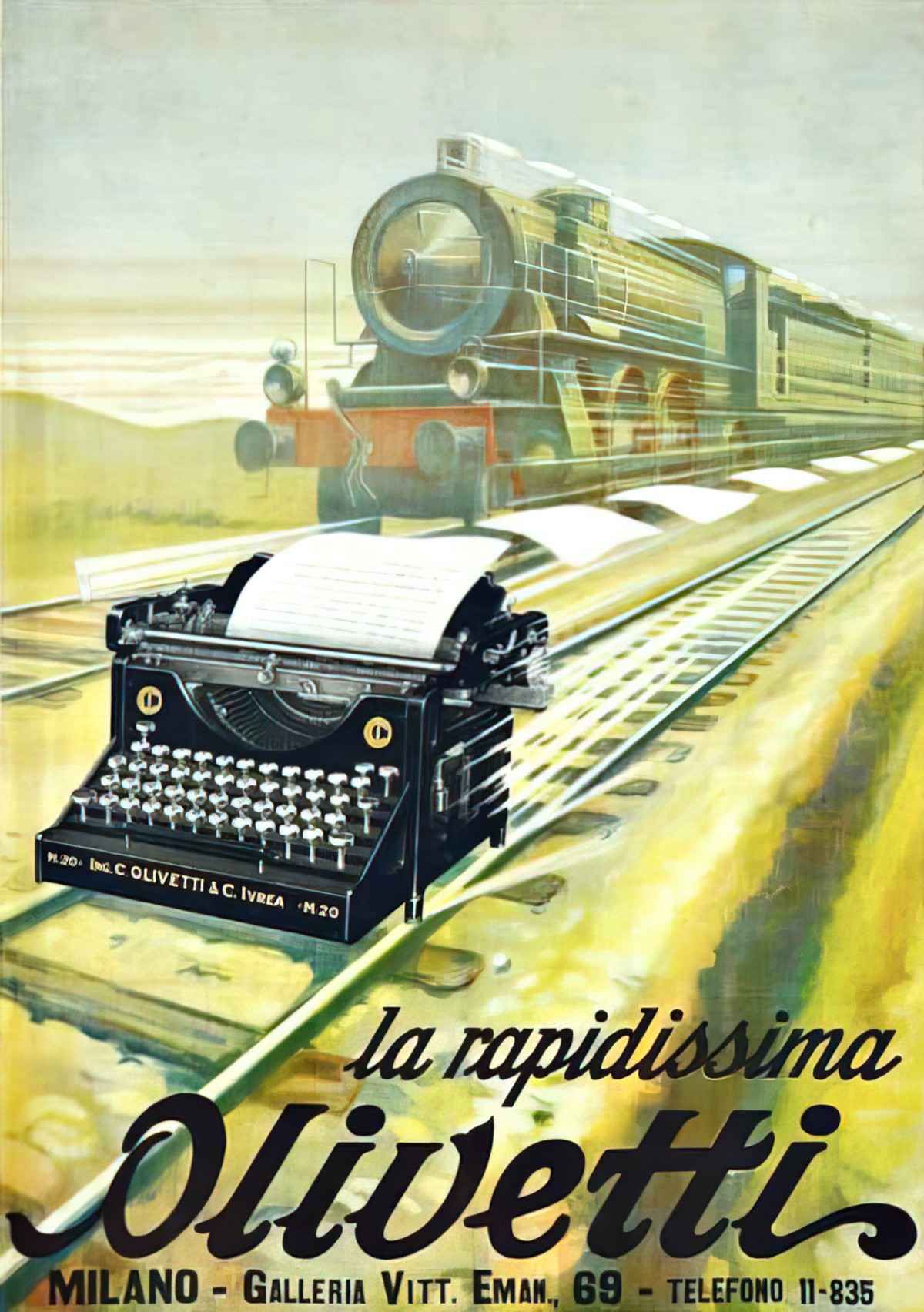

Trains Are Fast

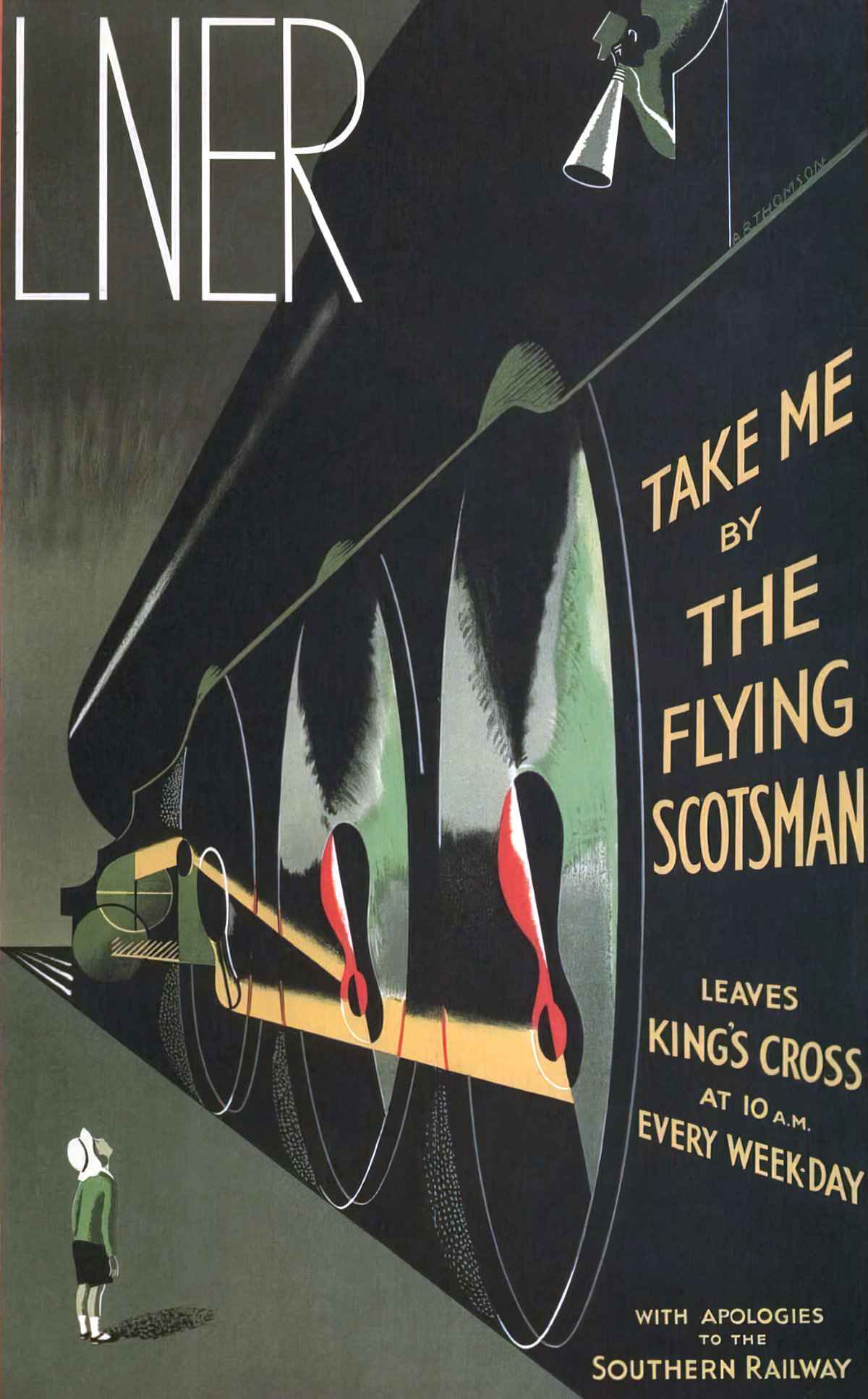

Contemporary travellers won’t associate trains with speed. The bullet trains in Japan are pretty fast, but planes are always faster. Earlier audiences didn’t feel this way about trains at all. For them, over a fairly brief period of human history, trains were the epitome of speed.

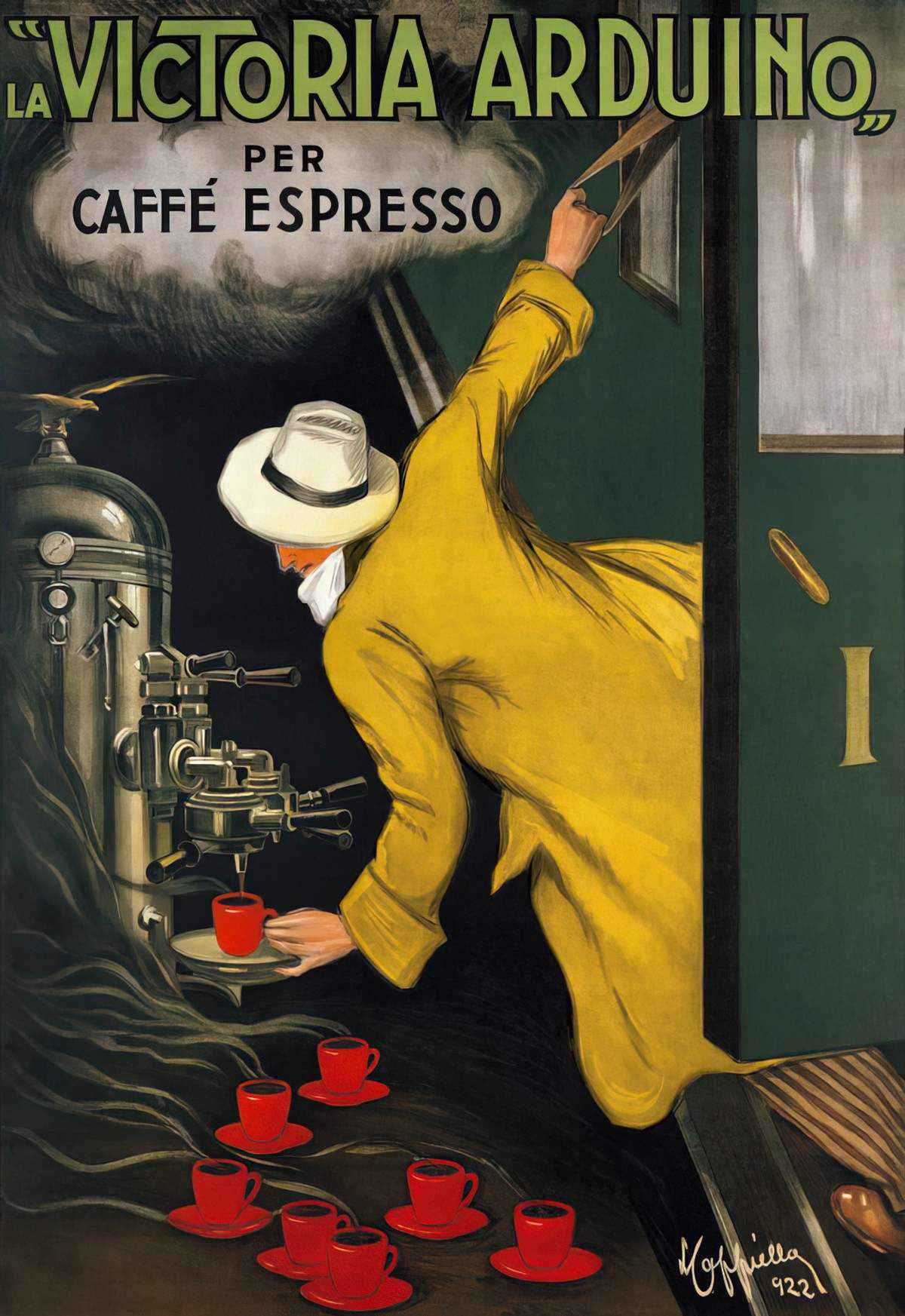

Once it was established in everyone’s mind that trains equal speed, advertisers of other products started comparing those other products to trains. The 1923 advertisement below is selling a super-fast Olivetti typewriter by comparing it to the speed of a train.

And here we have a coffee machine, which makes you coffee so quickly the train hardly even needs to stop at the platform!

Trains As Symbols of Socioeconomic Class

There’s no better modern example of a train used to highlight social inequality than Snowpiercer, first a film, now a TV show.

Apart from trains, other forms of public transport push rich and poor people together onto the same small vessel, most notably planes and ships. This turns the vehicle of transportation into a microcosm of society.

MIND THE GAP

In Western Australia a man managed to get stuck in the gap. There was a happy ending — he was freed after about 15 minutes, without injury. If you’re anything like me, you probably don’t really think about all those echoey announcements warning us to mind the gap, and you may have even peered at the gap at one point, wondering how anyone could possibly get their foot stuck down there, except for maybe a toddler.

Public Transport Authority spokesman David Hynes … it was an impressive feat because the gap between the train and platform was less than five centimetres.

Warnings to ‘Mind The Gap’ are so well-known that the phrase is used metaphorically to refer to other things.

This is not an original metaphor. Scientific American has used it, for instance, as have many others.

Do you know how this ‘Mind The Gap’ warning is announced in other languages around the world? Wikipedia has a list of translations.

Can you think of any other phrases like this which have become part of popular culture, commonly used to refer to other things? Wikipedia offers ‘Objects in mirror are closer than they appear’ as another example.

How many of these do you recognise?

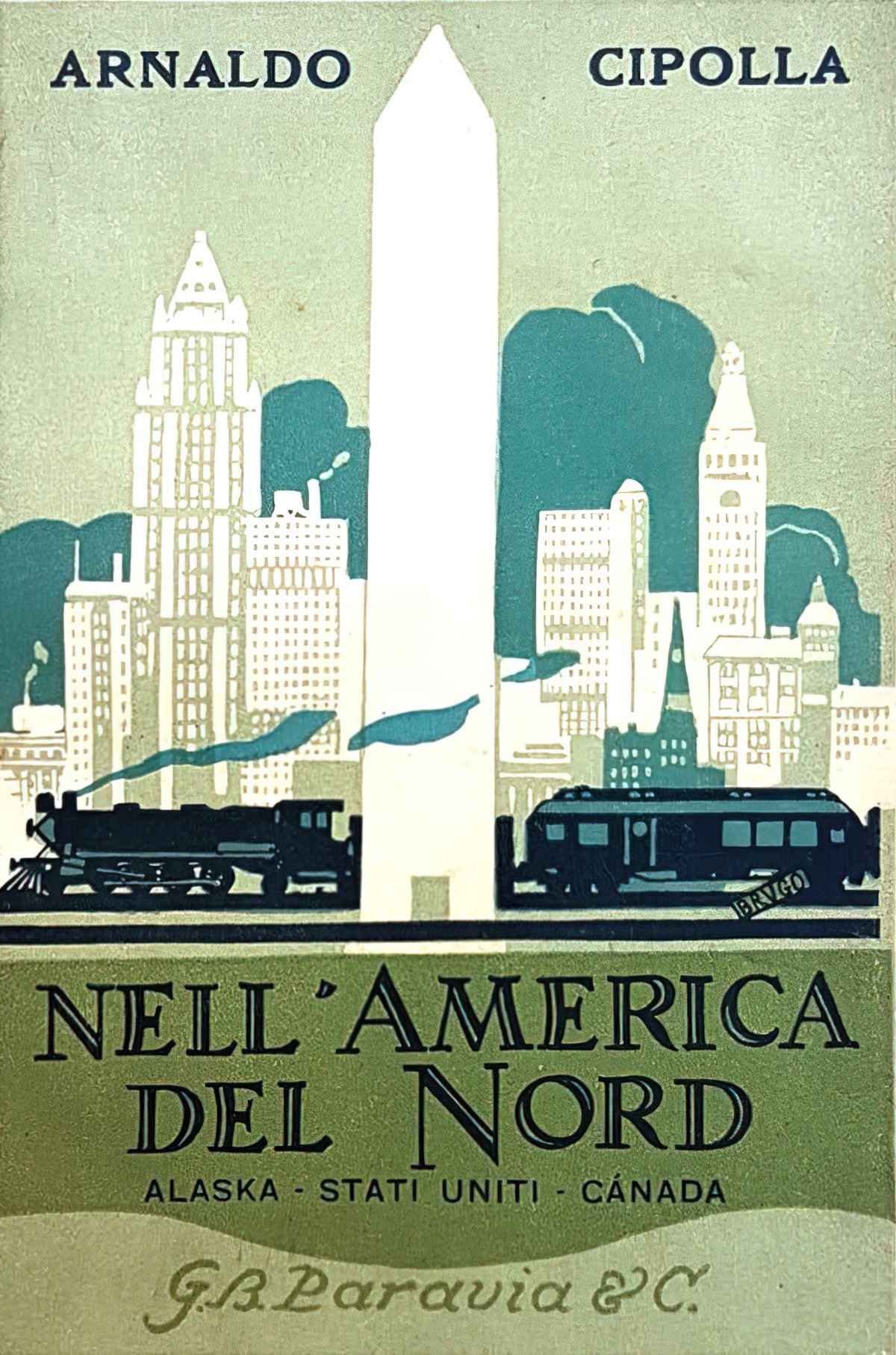

Trains as Symbols of Expansion Into The American West

Ships are metonyms for England in stories about colonisation. Trains work similarly.

Trains As Symbols Of The City

Trains and the subway system are often central city images with multiple meanings in children’s literature. In Holman’s Slake’s Limbo, the New York subway becomes a metaphor for escape and freedom. We are told early in the novel “Aremis Slake had often escaped into the subway when things got rough above ground. He kept a subway token in his pocket for just that emergency”. Moreover, the subway takes on a greater magical force or power related to Slake’s personal choices and destiny, rather than merely a means of transit: “Slake with the instinct of other migratory creatures flew from the train at Seventy-Seventh Street and Lexington Avenue. This was an unusual move in itself; Slake usually exited only at transfer points”. Comparatively, in Robert Munsch’s picture book Jonathan Cleaned Up-Then He Heard a Sound, illustrated by Michael Martchenko, the mysteries of the city’s subway are perceived in a fantastical and absurd manner when young Jonathan’s living room becomes a subway station. It is an ordinary day at home when suddenly the living room wall opens up, a subway train pulls up and “all kinds of people came out of Jonathan’s wall, ran around his apartment and out the front door.” A mission down to City Hall leads Jonathan to find (in a moment reminiscent of Dorothy finding the “great and powerful Oz” behind the curtain) a little old man, who craves blackberry jam, behind a huge machine that apparently runs the city. He tells Jonathan that because the computer is broken, he does “everything for the whole city”. The story hilariously concludes with an illustration depicting the subway rerouted to stop at the Mayor’s office instead. Through Jonathan’s imaginative perspective, the behind-the-scenes controls of the city are in a realm as mysterious, fantastical or absurd as a mad tea party in Wonderland.

Naomi Hamer

Case Study: Trains in Katherine Mansfield Short Stories

You’ll find the most dense symbolism in lyrical short stories, so let’s take a closer look at some stand-out examples.

In her paper on Katherine Mansfield’s short story “The Escape“, Masami Sato has this to say about train symbolism, in which every aspect of the train is ripe for close-reading, including the doors (open or closed?), the rails on the balcony, and the carriage shared with others:

Using trains symbolically is a technique found frequently in literary history. It has been used as a place where people accidentally meet, separate, take time to think, work on something, and even as a place of rest and relaxation. We can see some of this symbolism in the last paragraph of “The Escape”.

The door of the carriage seems to refer to the threshold, or border, between the wife’s world and the husband’s heavenly (maybe, by implication, his ideal) world. The door is open, which denotes that he is still connected with his wife’s world, even though he does not want to be completely submerged in it. However, since he is holding on tightly to the brass rail with both hands, this could possibly signify his effort in trying to cling to his sense of happiness, having escaped, if only momentarily, the space which is dominated by his turbulent relationship with his wife.

The train carriage, for the wife, could be seen as a place to relax: as mentioned before, the wife is talking contentedly with the other passengers, while the husband is absorbed in his solitary emotions of happiness, apart from her, in the corridor. Their juxtaposition refers to two different worlds, and suggests that from a gender point of view, the worlds of men and women do not cohere seamlessly.

The story began with the couple missing their train and ends with a scene on a train. I would suggest that Mansfield intentionally uses the symbol of the train journey at the beginning of the narrative to demonstrate the emotional gulf between the husband and wife, a state which is shown to be highlighted if they spend time in too close proximity to each other. In the story’s ending, Mansfield suggests, by their positions in the separate (yet adjoining spaces) of the train compartment and the corridor, that perhaps, in a marriage, a certain amount of distance between individuals is more comfortable for both of them.

Katherine Mansfield’s Portrayal of Marriage In “The Escape”

Another story, “Something Childish But Very Natural” is an excellent example of how the movement of a train is symbolically representative of fate.

The train of “Something Childish” is both a motif and a setting. I’ve written before about the symbolism of trains. Alice Munro is another short story writer who likes to make heavy symbolic use of them. Trains are interesting as an example of heterotopia — an ‘other’ space, separate from the regular world. To enter into a heterotopia is akin to going through a fantasy portal (even when the story is not speculative in nature).

Trains are the perfect fatalistic symbol; there’s only one path for a train — its pre-laid tracks. A fatalistic view of the world means you’re all about destiny, and subscription to the idea that we are powerless to do anything other than what we actually do.

The trains of “Something Childish But Very Natural“ are also useful for symbolising the iterative nature of our daily lives — trains basically do the same things every single day, turning up at the same places at the same times. This gives a sort of Groundhog Day vibe to a story, before an author switches readers to the singulative (but on this particular day…)

Trains and tunnels go together.

“Something Childish But Very Natural” is also an excellent example of how tunnels are used symbolically. Two young lovers ride a train, falling more and more in love as their journey progresses. But their dreams of love are punctuated by tunnels, foreshadowing the darkness of their emotions at story’s end.

Also in “Something Childish But Very Natural”, Mansfield matches Henry’s excited, elevated heart rate to the sounds of the train moving over the tracks. She describes how the train smells — wet india-rubber and soot. We really do feel transported to the era of steam engines.

Case Study: Trains In Alice Munro Short Stories

Alice Munro has also written short stories which take place on trains, one of my favourites being “Chance”.

“Free Radicals” is another interesting example.

What about the train thread in this story? First, the sexe en plein air near the tracks, between Nita and Rich. Later, the train reappears and now it is a symbol of fate.

“You wait till I say. I walked the railway track. Never seen a train. I walked all the way to here and never seen a train.”

“There’s hardly ever a train.”

The train track itself led the murderer to Nita’s house. There was nothing she could do to stop him. This fate was set in place the moment she started the affair with Rich. (And even that was probably fate.)

Case Study: Trains in a Robin Black Short Story

The following is the opening paragraph from”A Country Where You Once Lived” by Robin Black. It demonstrates perfectly the way in which trains signify the passage of time. Notice, too, how Black is saying something about ‘train window scenery’ as well:

It isn’t even a two-hour train ride out from London tot he village where Jeremy’s daughter and her husband—a man Jeremy has never met—have lived for the past three years, but it’s one of those trips that seems to carry you much father than the time might imply. By around the halfway point the scenery has shaken ff all evidence of the city, all evidence, really, of the past century or two. […] It’s a fantasy landscape, he thinks. The kind that encourages belief in the myth of uncomplicated lives.

Robin Black

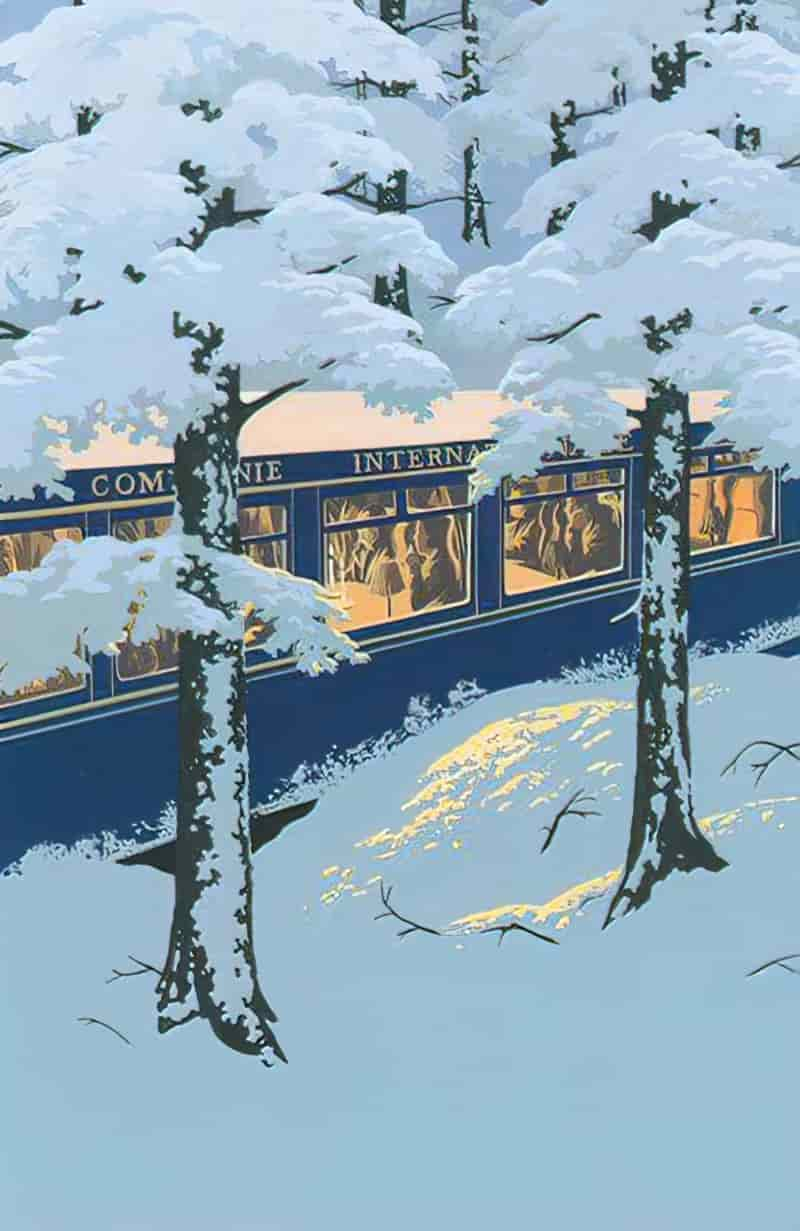

Trains as Portal To Luxury

Symbols of Perseverance

We tend to personify vehicles, so the sight of a heavy train making its way up a hill can be a gratifying sight.

The standout picture book example of a train trying its best is The Little Engine That Could by Watty Piper.

A Train Bisects A Town

Train carriages themselves divide passengers by socioeconomic status.

Also, the English language idiom ‘wrong side of the tracks‘ describes the part of town that is not inhabited by the wealthy; an area where the working class, poor or extremely poor live.

Even when the socioeconomic division is not implied, a railway line does function as a noisy, dangerous (but necessary) presence which runs through town, bringing inhabitants to a standstill whenever it rumbles through.

The Train Unites and Divides Families and Lovers

Trains As Setting For A Crime Story

Murder On The Orient Express by Agatha Christie is a standout example. Trains make good settings for murder mysteries for a number of reasons. The game Cluedo works with the same advantage: a limited set of suspects. This is called a locked-room mystery.

The “locked–room” or “impossible crime” mystery is a subgenre of detective fiction in which a crime (almost always murder) is committed in circumstances under which it was seemingly impossible for the perpetrator to commit the crime or evade detection in the course of getting in and out of the crime scene.

Locked Room Mystery, Wikipedia

With a train we also have a ticking clock device, because the train will eventually reach its destination and the murderer will then have the opportunity to walk away free.

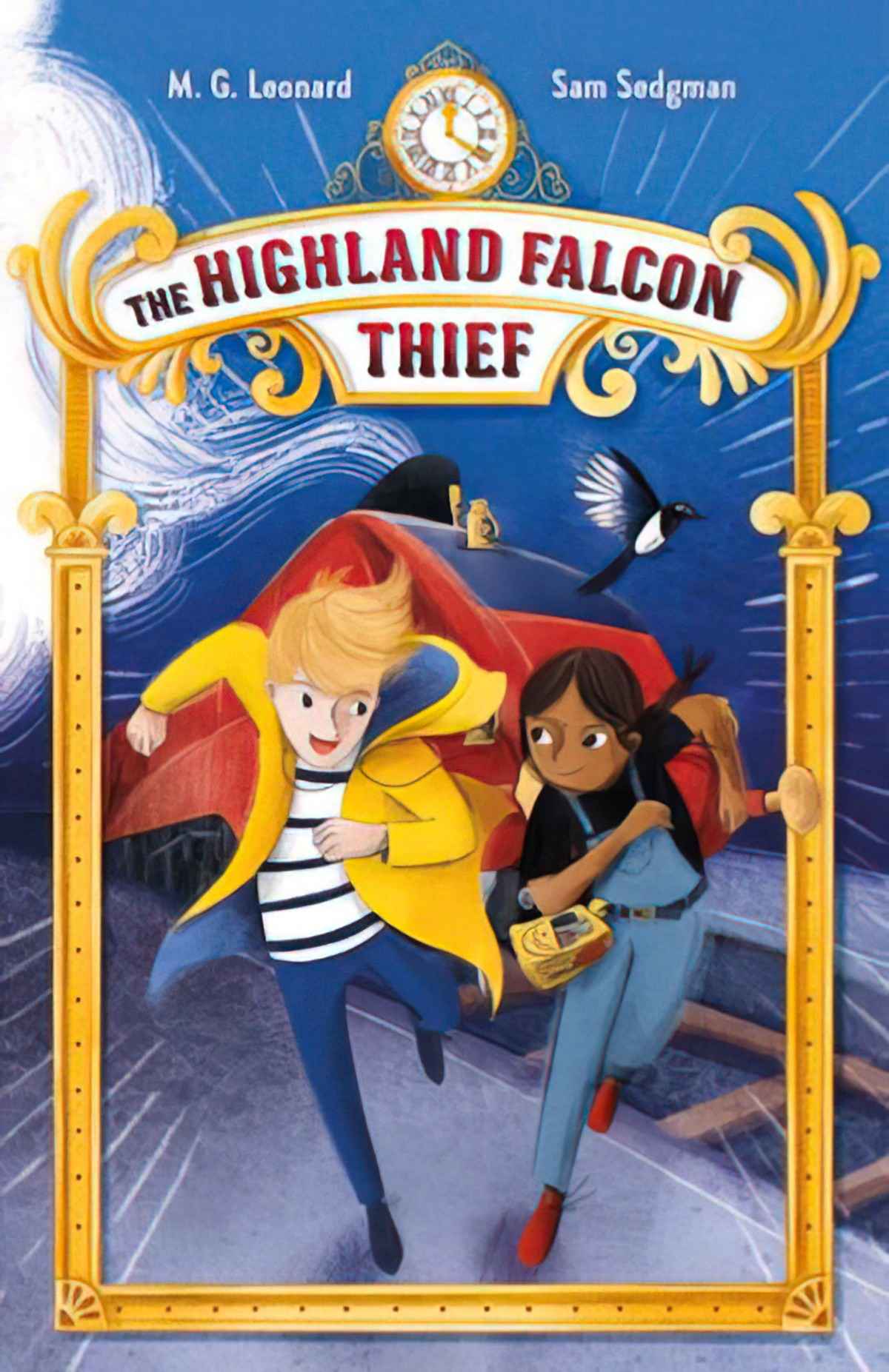

In The Highland Falcon Thief: Adventures on Trains #1, a middle-grade series starter from MG Leonard and Sam Sedgman, a young boy is swept up in an investigation to uncover the perpetrator of a jewel theft.

When eleven-year-old Harrison Hal Beck is forced to accompany his travel-writer uncle on the last journey of a royal train, he expects a boring trip spent away from video games and children his age.

But then Hal spots a girl who should not be on board, and he quickly makes friends with the stowaway, Lenny. Things get even more interesting when the royal prince and princess board for the last leg of the journey–because the princess’s diamond necklace is soon stolen and replaced with a fake! Suspicion falls on the one person who isn’t supposed to be there: Lenny.

It’s up to Hal, his keen observation, and his skill as a budding sketch artist to uncover the real jewel thief, clear his friend’s name, and return the diamond necklace before The Highland Falcon makes its last stop.

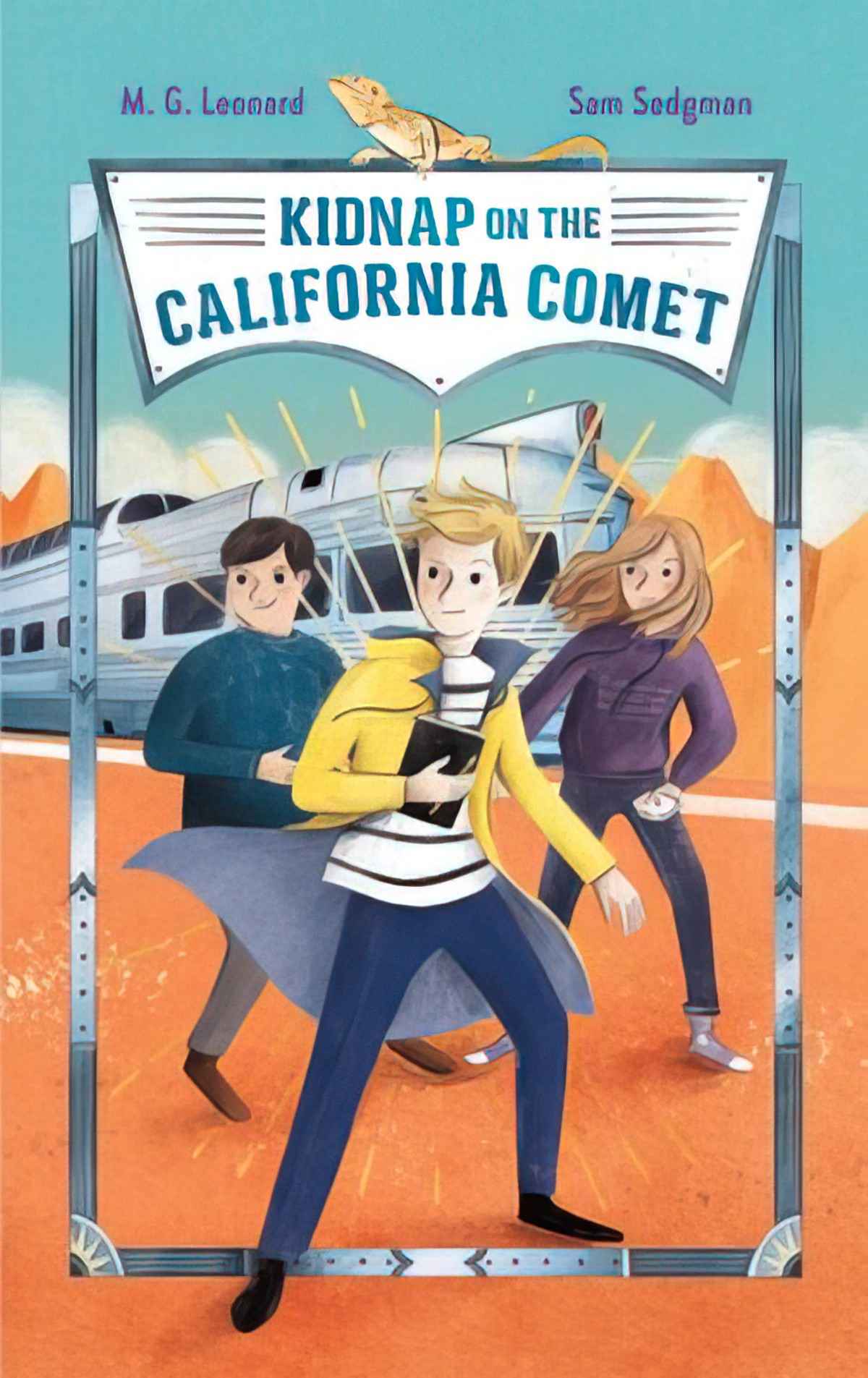

KIDNAP ON THE CALIFORNIA COMET BY M.G. LEONARD AND SAM SEDGMAN

In this second book of the middle-grade Adventures on Trains series, amateur sleuth Hal Beck travels to the U.S. with his uncle to ride a famous train—the California Comet—and stumbles on a new mystery to solve, in M.G. Leonard and Sam Sedgman’s Kidnap on the California Comet…

After his adventure on the Highland Falcon, amateur sleuth Hal Beck is excited to embark on another journey with his journalist uncle. This time, they’re set to ride the historic California Comet from Chicago to San Francisco.

Hal mostly keeps to himself on the trip, feeling homesick and out of place in America. But he soon finds himself drawn into another mystery when the young daughter of a billionaire tech entrepreneur goes missing!

Along with new friends—spunky 13-year-old Mason and his younger sister, Hadley—Hal races against the clock to find the missing girl before the California Comet reaches its final destination.

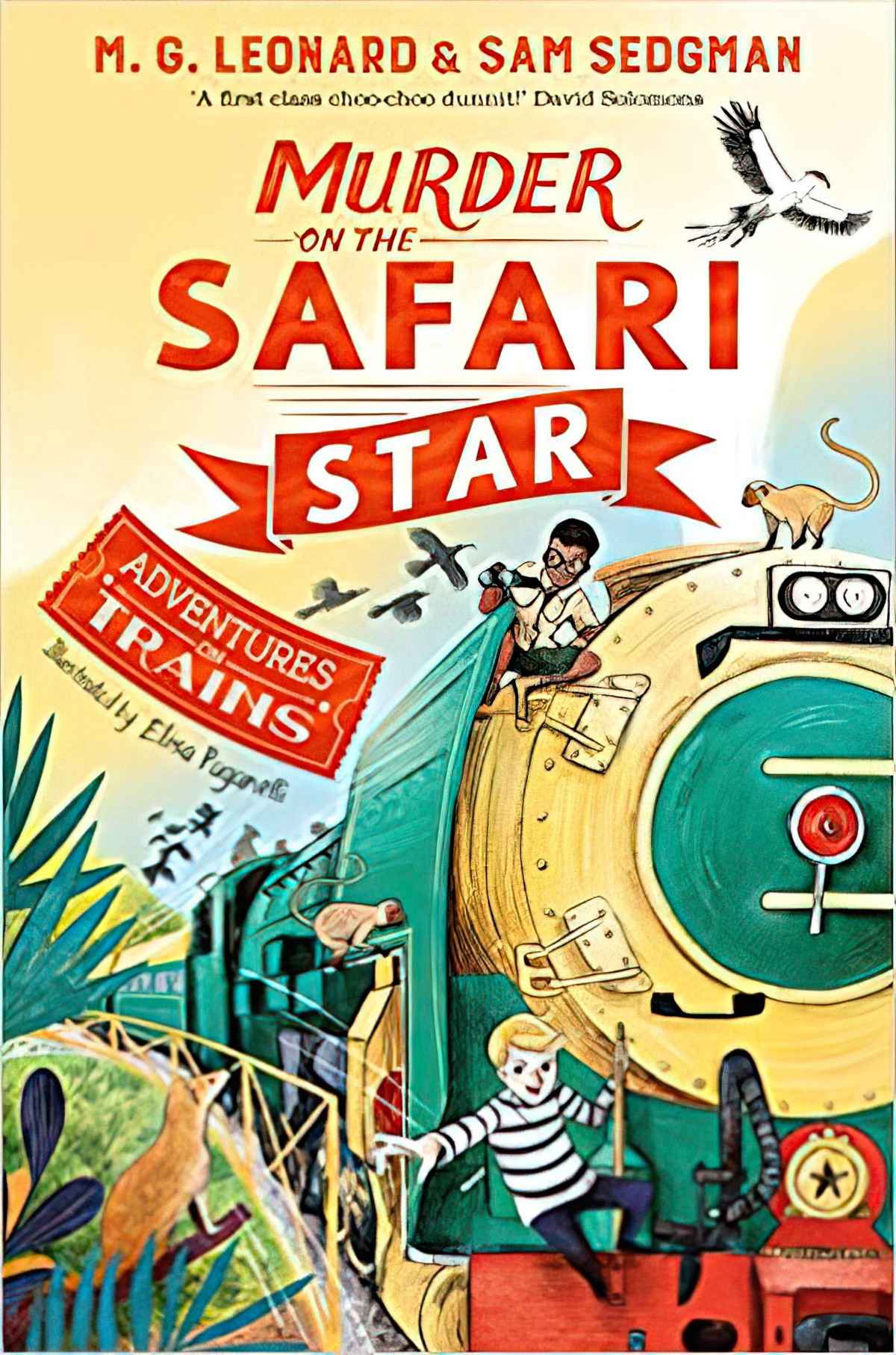

MURDER ON THE SAFARI STAR BY M.G. LEONARD AND SAM SEDGMAN

Join Hal and Uncle Nat as they plunge straight into an exciting mystery – this time while on Safari!

All-aboard for the third amazing journey in the bestselling Adventures on Trains series from M. G. Leonard and Sam Sedgman, illustrated throughout by Elisa Paganelli.

Uncle Nat is taking Hal on the journey of a lifetime – on a Safari Train from Pretoria to Victoria Falls. Drawing Africa’s amazing wild animals from on board a spectacular steam train described as a luxury hotel on wheels, should be enough excitement for anyone. But something suspicious is happening on board the Safari Star and when a passenger is found mysteriously killed inside a locked compartment, it’s up to Hal, along with his new friend Winston and his pet Mongoose, Chipo, to solve the murder mystery.

RAILWAY SYMBOLISM

A railway is like an iceberg, you know: very little of its working is visible to the casual onlooker.

Robert Aickman, from “The Trains”, a horror short story

The illustrations below are less-seen perspectives of railway tracks, defamiliarising the train for us, offering a worm’s eye view perspective.

The Ticking Clock is a tool often used by storytellers to add narrative drive. Anytime characters venture near railway tracks our heartrate increases as we know (or suspect) a train will be coming along soon.

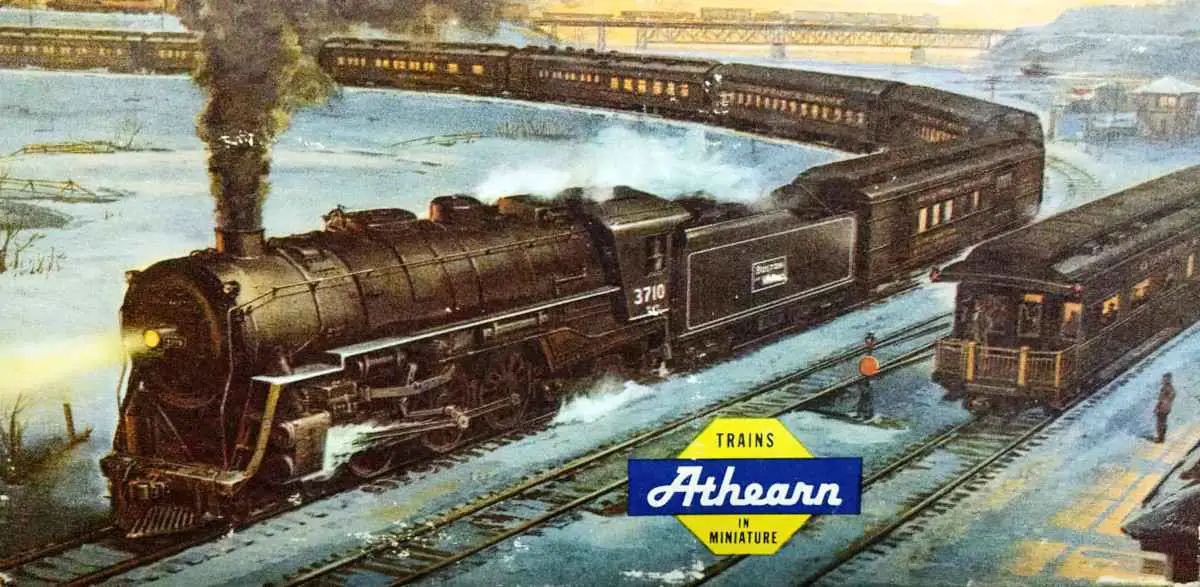

Trains And The Miniature

Humans love to mess around with size and scale.

We also love to create miniature versions of the things important to us. Model trains have long been associated with boyhood.

OVERVIEW OF TRAIN SYMBOLISM IN STORIES

- When characters meet someone on a train they could so easily not have met them. This makes any encounter seem serendipitous.

- This connects to a fatalistic view of the world (and perhaps of love), and the idea that ‘two souls were meant to meet’. The straight line of the tracks is a symbol of fate.

- Tunnels (which are literally dark) can foreshadow emotional darkness to come.

- Trains represent how humans experience time even though this is not how time actually works.

- When we think of time in terms of straight, inevitable lines, we are drawn into a fatalistic view of the universe.

- Trains are a part of the real world but work differently from the real world. We talk to people we might not otherwise have the chance to talk to. This is what makes them a heterotopia.

- Trains can stand in for society, conveniently pushing rich and poor together, highlighting the divide.