“The Toys of Peace” (1919) is a short story by H.H. Munro (a.k.a. Saki) and is out of copyright so can easily be found online. This is the opening short story in a collection called The Toys Of Peace And Other Papers by H.H. Munro (and G.K. Chesterton). This volume was published after Saki’s death. Saki died on a battlefield during WW1.

Readers will most definitely arrive at this story with their own ideas about children, toys, gender and violence. This will very much affect your reading.

SETTING OF TOYS OF PEACE

“Toys Of Peace”, set in 1914, is a story about boys and their toys. It contains no girls, so ostensibly says nothing about girls, but there is a good reason why Munro chose two nephews rather than a nephew and a niece as the child subjects of this story, and it’s the same reason he created a mother to instruct the boys’ uncle on what to give them rather than an uncle who decides to embark upon this n=2 experiment himself.

Toys have been gendered since the industrial revolution, at least, and the more marketers can persuade adult gift-buyers that boys and girls need different toys, the more toys they will sell; families with both boys and girls won’t feel they can reuse the same toys for all of their kids. Witness the increasing gendering of Lego, as evidenced by the addition of Lego Friends (marketed at girls). In the 1970s and 80s, Lego was not gendered and they sold less of it. Lego has always been considered more of a boy’s toy; I shared the Lego that was gifted to my brothers.

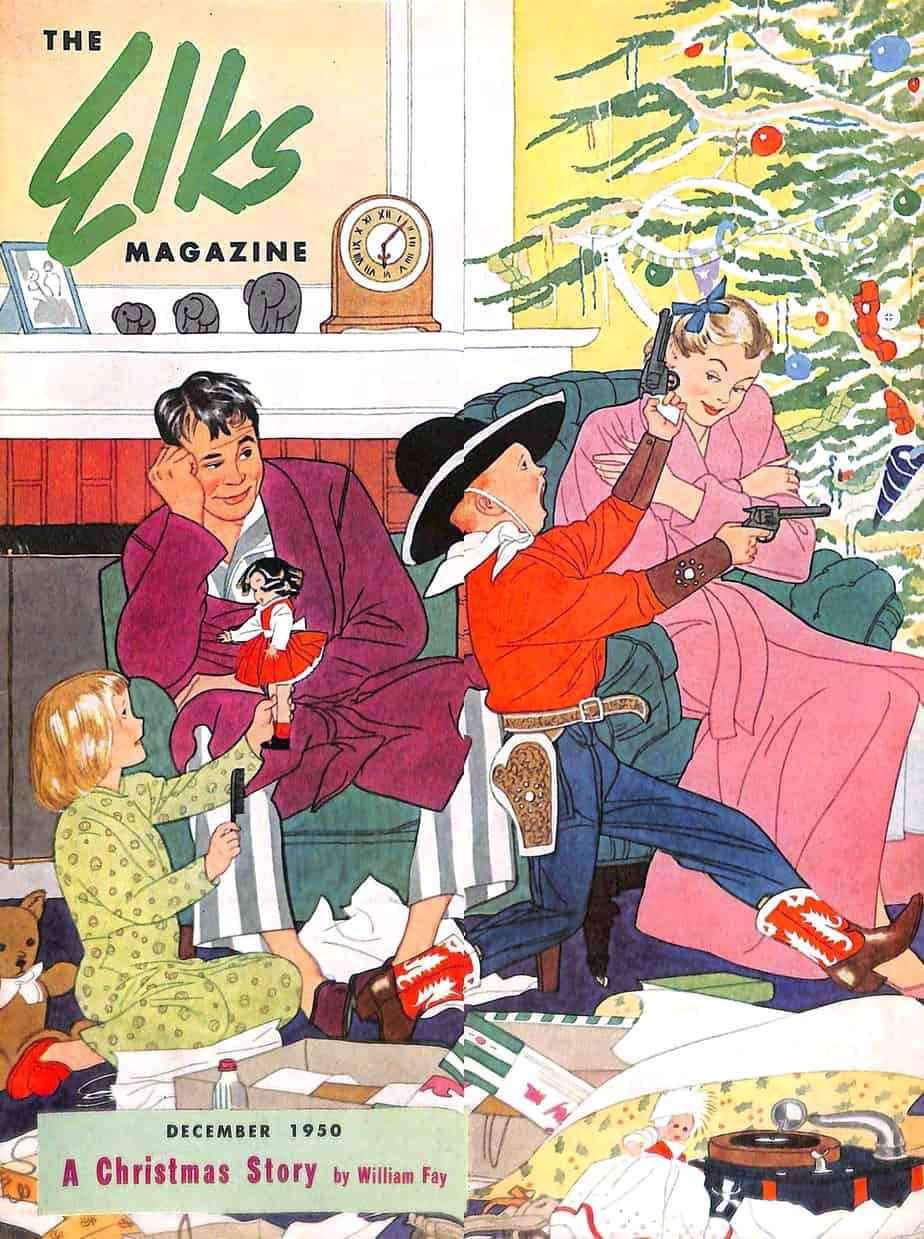

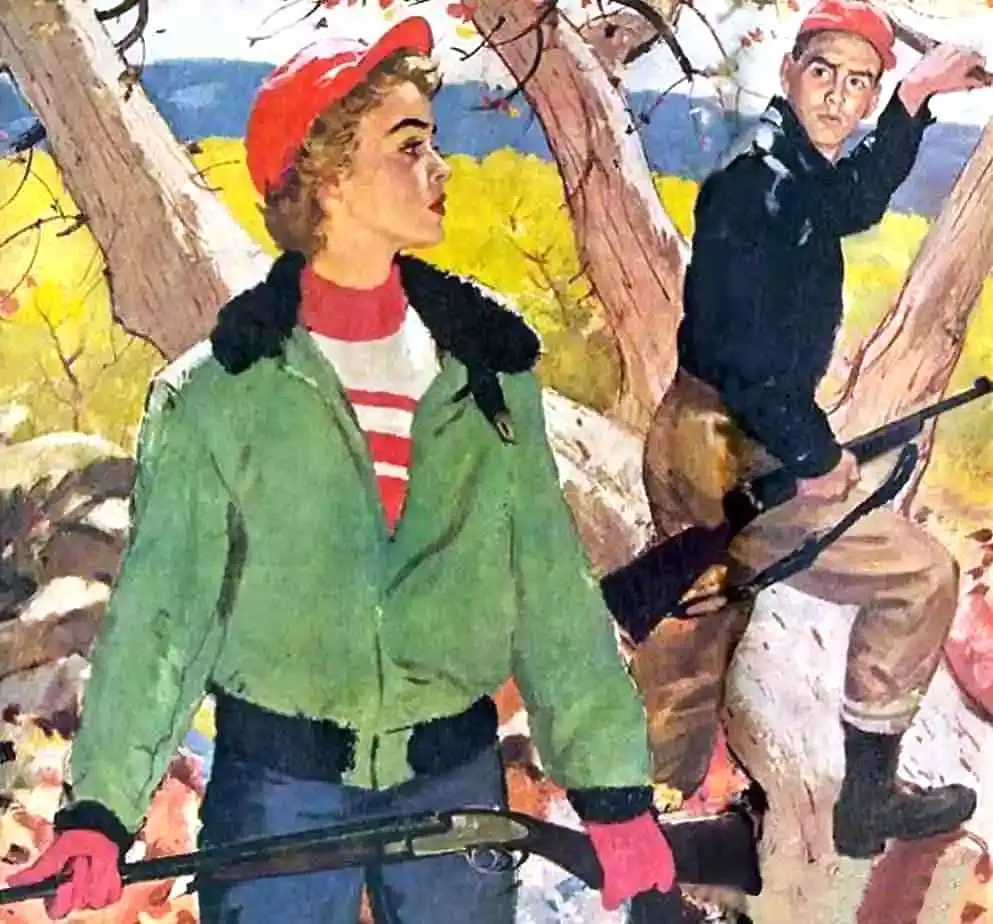

I remember slivers of the debate about boys and toy guns as I was growing up in the 1980s and 90s. My parents gifted us guns, which came with firecracker dust cartridges and made a satisfying popping sound, replete with smoke. (I liked those guns as much as my brothers did.) Our parents said on more than one occasion, probably to other adults with me eavesdropping nearby, that it is clearly fruitless to take toy guns away from children. Take away their guns and children will only utilise sticks to the same end.

This was the prevailing view of the 20th century and continues into the present. It is of historical interest to read a short story written more than 100 years ago which shows how long this discussion has been going on. Instead of ‘nature’ the phrase ‘primitive instinct’ is used here.

Fast forward to 2020, this is such a boring and frustrating binary discussion and I refuse to get into it. If only more people understood that the ‘nature versus nurture debate’ is long-gone, replaced by far more nuanced science. Scientists now understand that nature and nurture work in tandem, influencing each other. Epigenetics comes into it. Unfortunately, it gets so complex that this idea is beyond the average opinionated Joe who finds ‘nature versus nurture’ pleasantly simplistic, and will stick to it, thank you very much, because “I’ve had sons and also daughters, and they were definitely different, and my personal experience equals science.”

Was H.H. Munro expressing a ‘boys will be violent boys’ view, or has he left a little more room for reader interpretation?

STORY STRUCTURE OF TOYS OF PEACE

PARATEXT

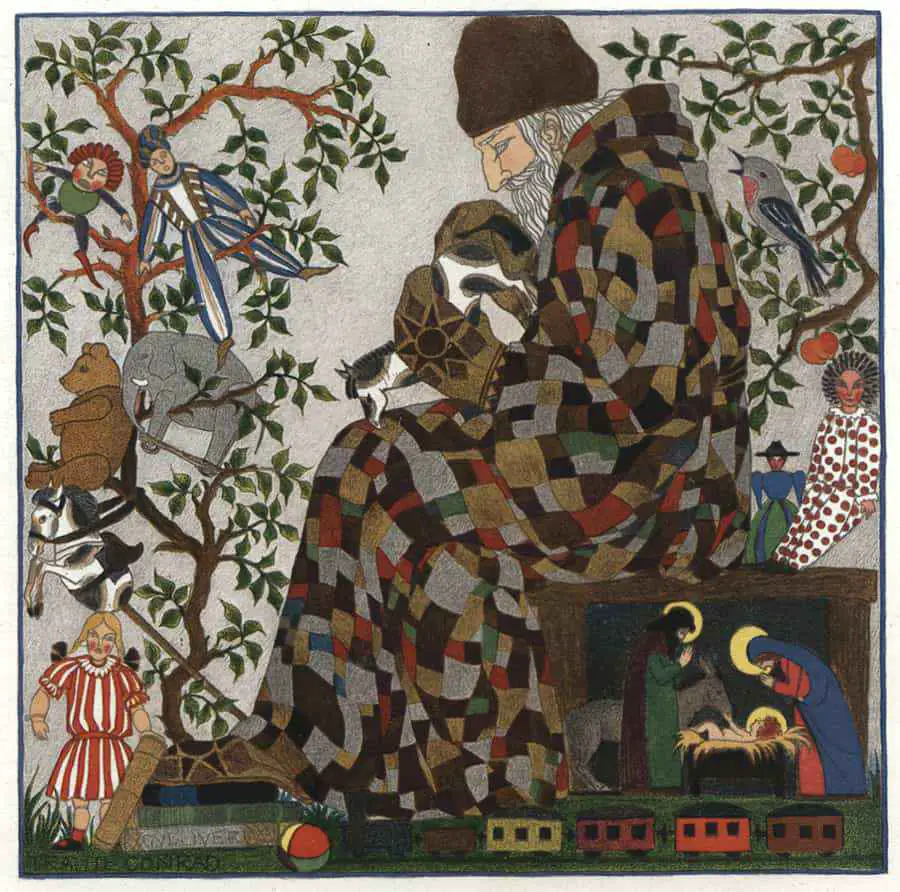

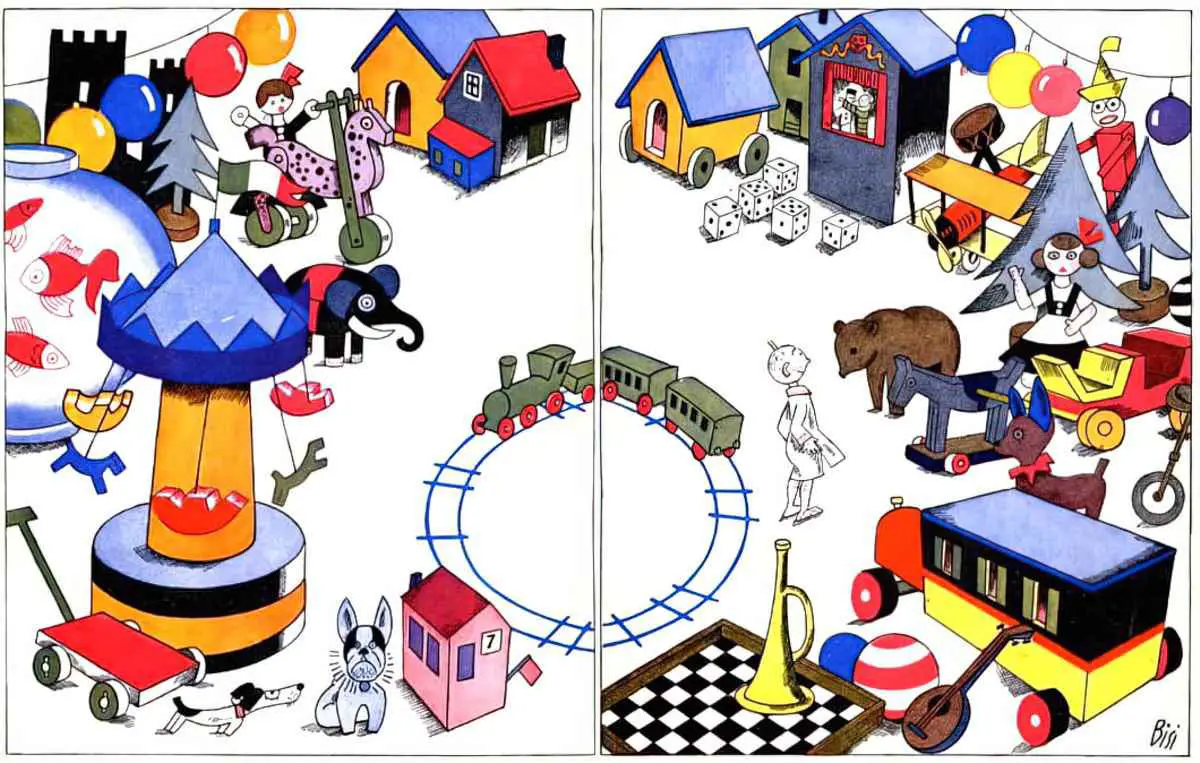

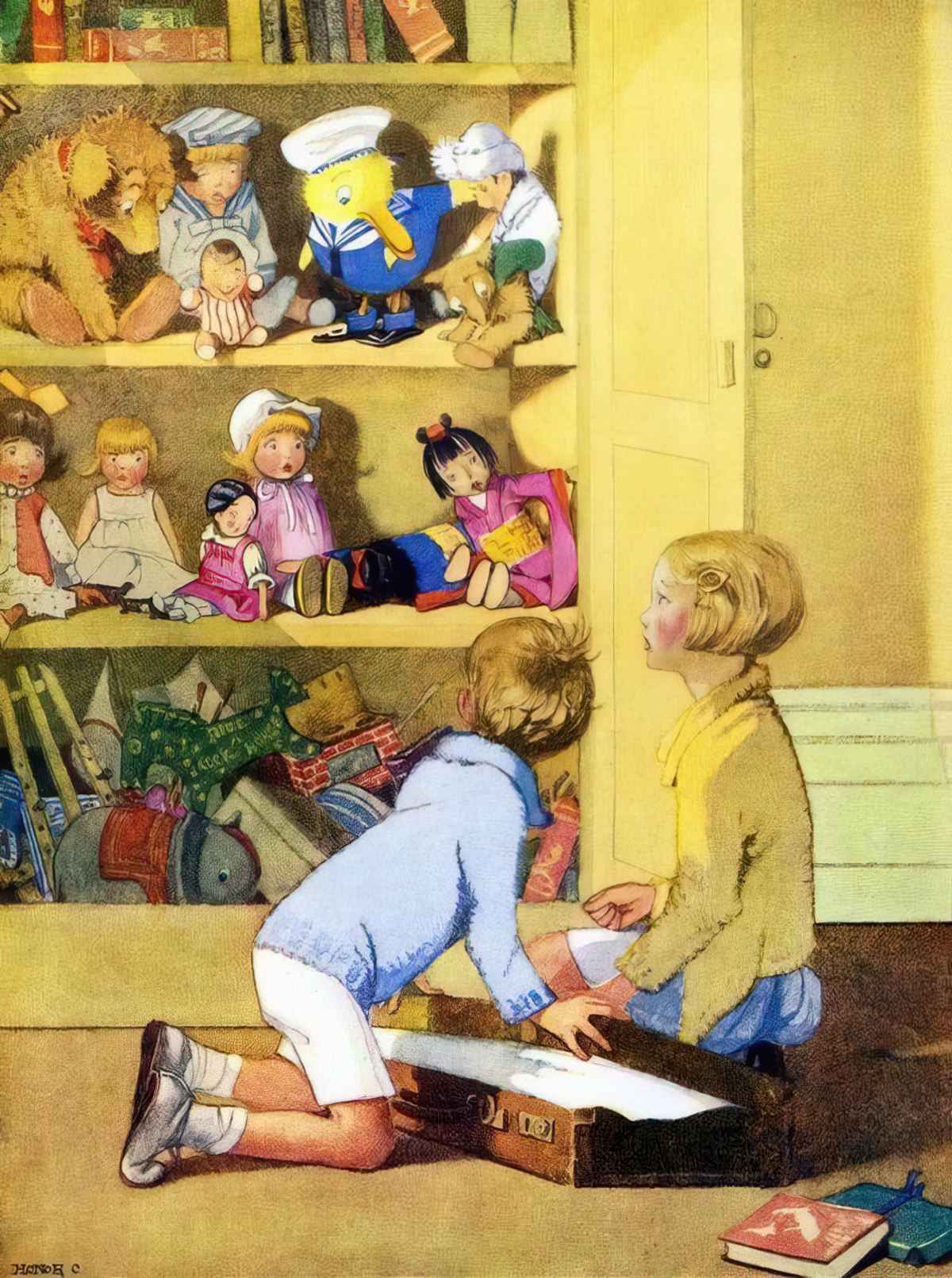

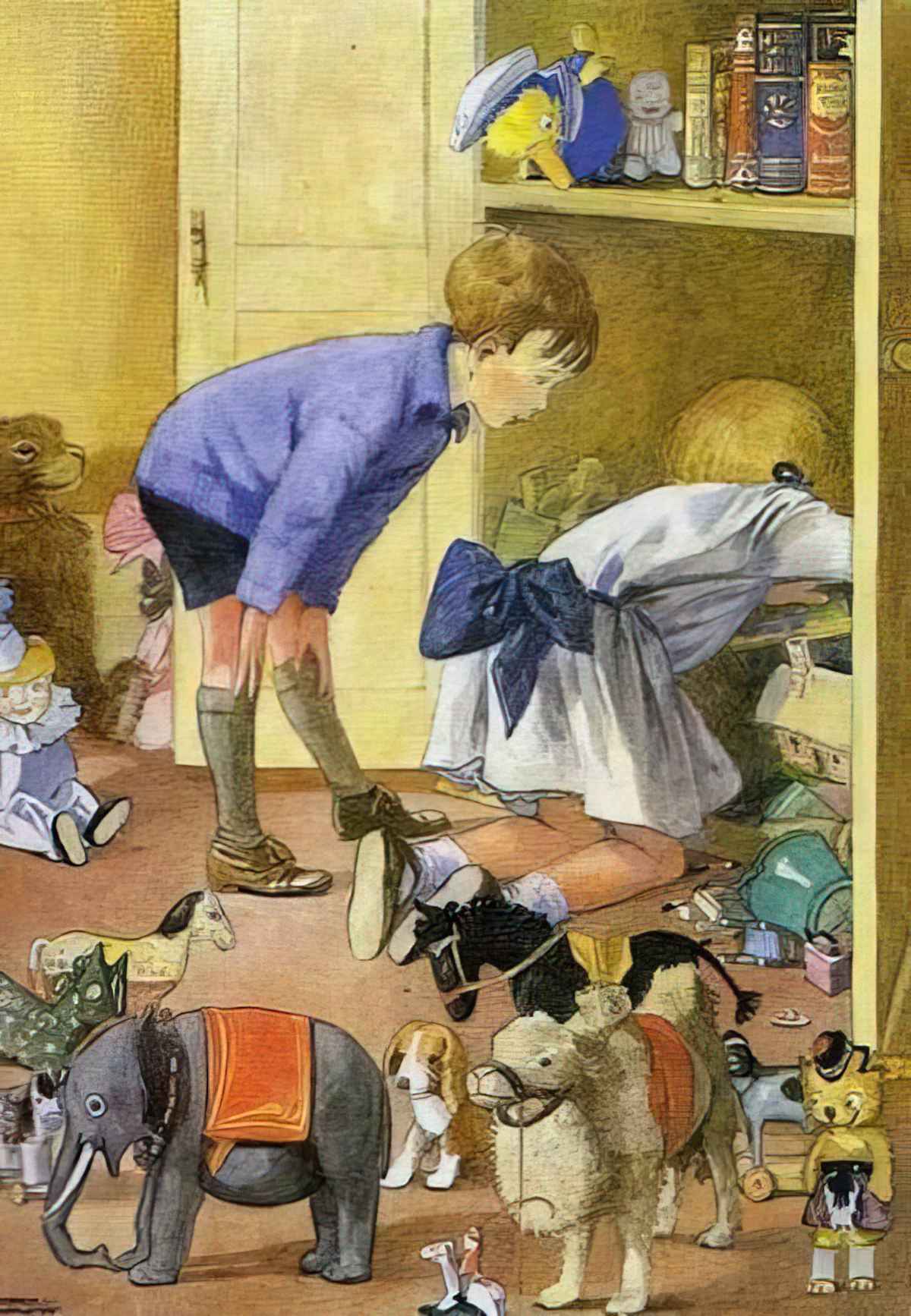

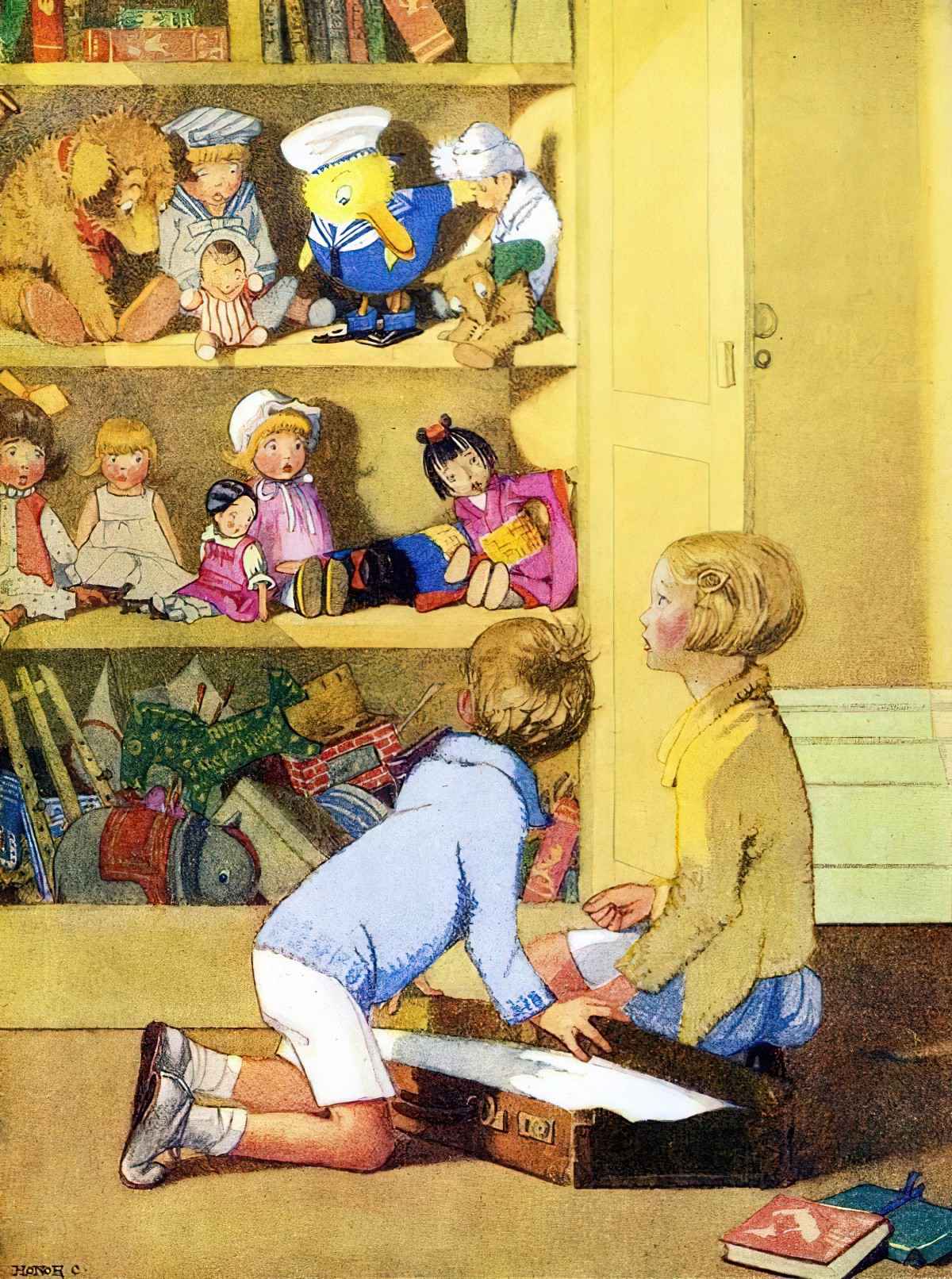

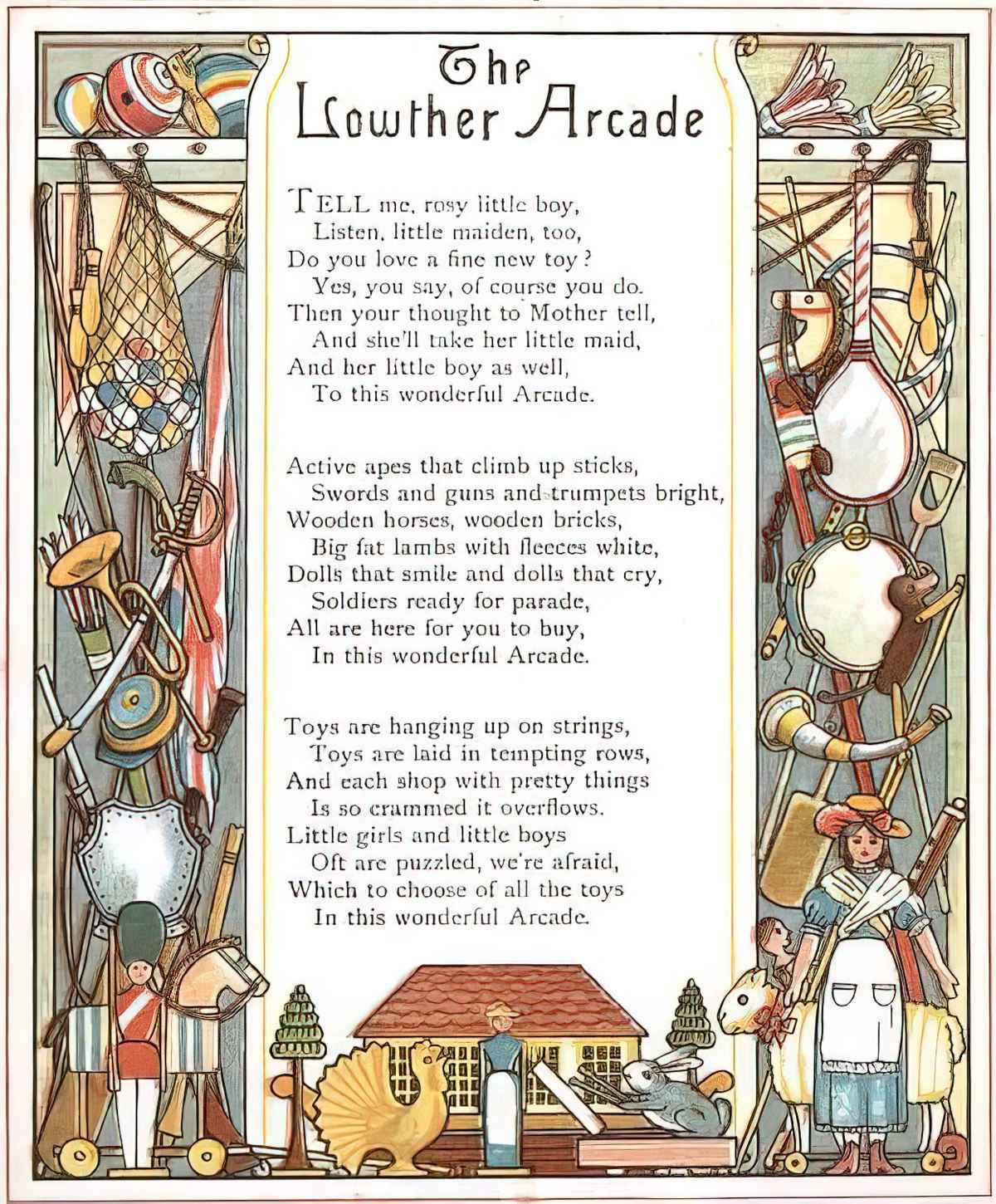

The paratext of this short story comes not from book blurbs and marketing copy but from an entire corpus of toy advertising and illustration, which in turn influences how boys and girls play.

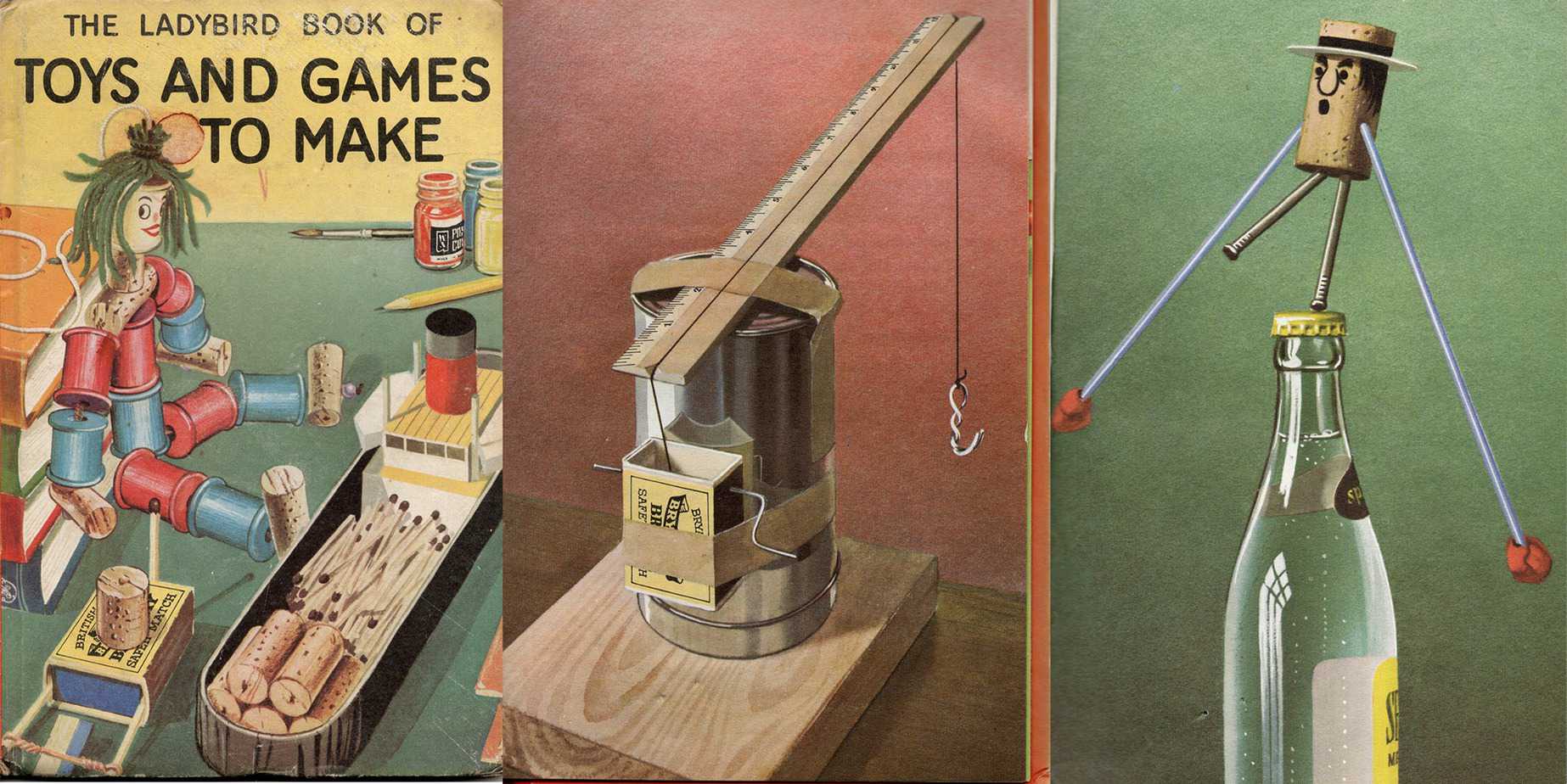

We all simply know which toys are for boys and which are for girls. Boys play with things they can assemble, which require technical knowledge, which move, and which fight.

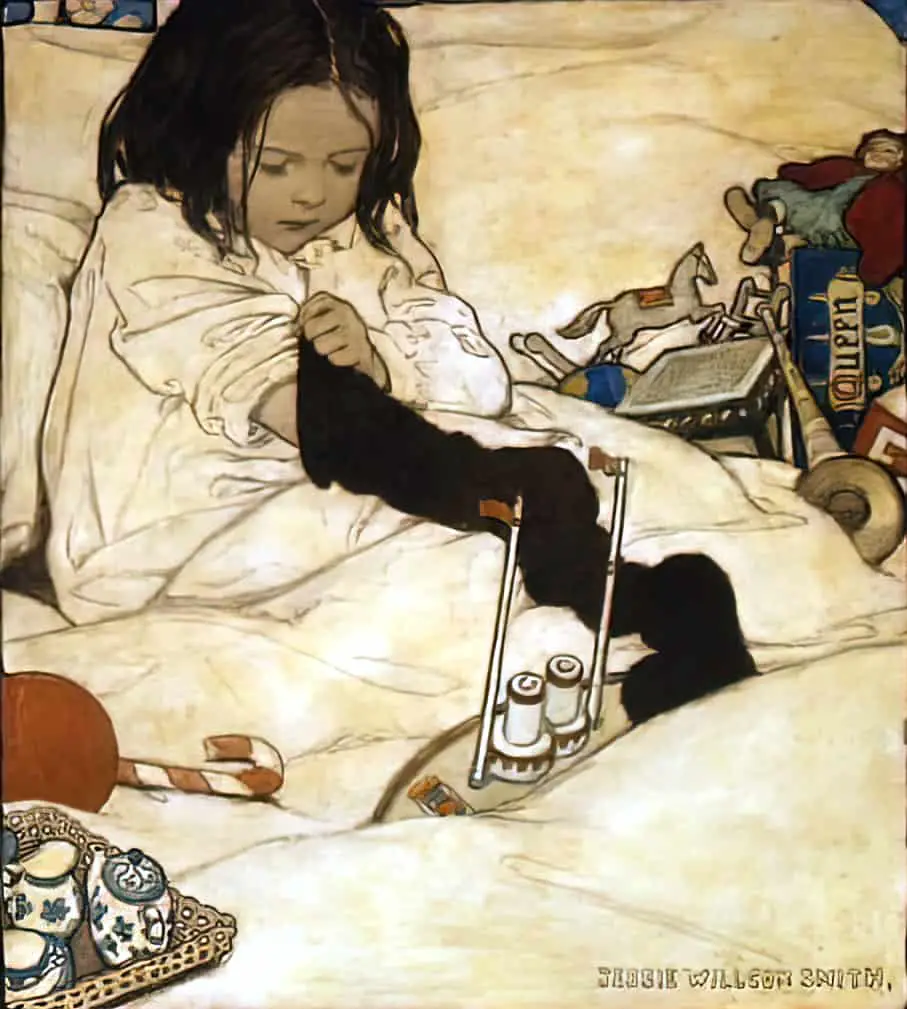

Girls’ toys encourage nurturing and care: tea sets, dolls, miniature versions of household appliances, toys which teach the basic skills of sewing, and anything that prettifies.

SHORTCOMING

“Toys Of Peace” is the story of a community, and the characters of “Toys Of Peace”are archetypes. The boys are Every Boys. The mother is the Every Mother. Only the uncle feels like an interesting individuation. He is clearly taking the piss while appearing to follow his sister’s instructions regarding gifts for his nephews. And he does go utterly over the top.

But because Saki is is dealing with archetypes, the shortcoming of these characters is presented a universal shortcoming in humans: People (especially masculine people) are drawn towards violence. Nothing can be done.

DESIRE

The desire of this plot is driven by the mother, who asks her brother to buy ‘peace toys’ for her sons. She doesn’t want their toys to lead them towards more violence. (The mother understands that her boys are already plenty exposed to it.)

I was interested to learn that this was a feminist movement even as the world entered the first World War: Mothers have been trying to instill more caring, stereotypically feminine virtues in their sons for over 100 years, even as the dominant culture draws their boys into war. Perhaps mothers were more emphatic about that in a time of war. We don’t hear the stories of those mothers, though. We hear about bravery and necessary sacrifice.

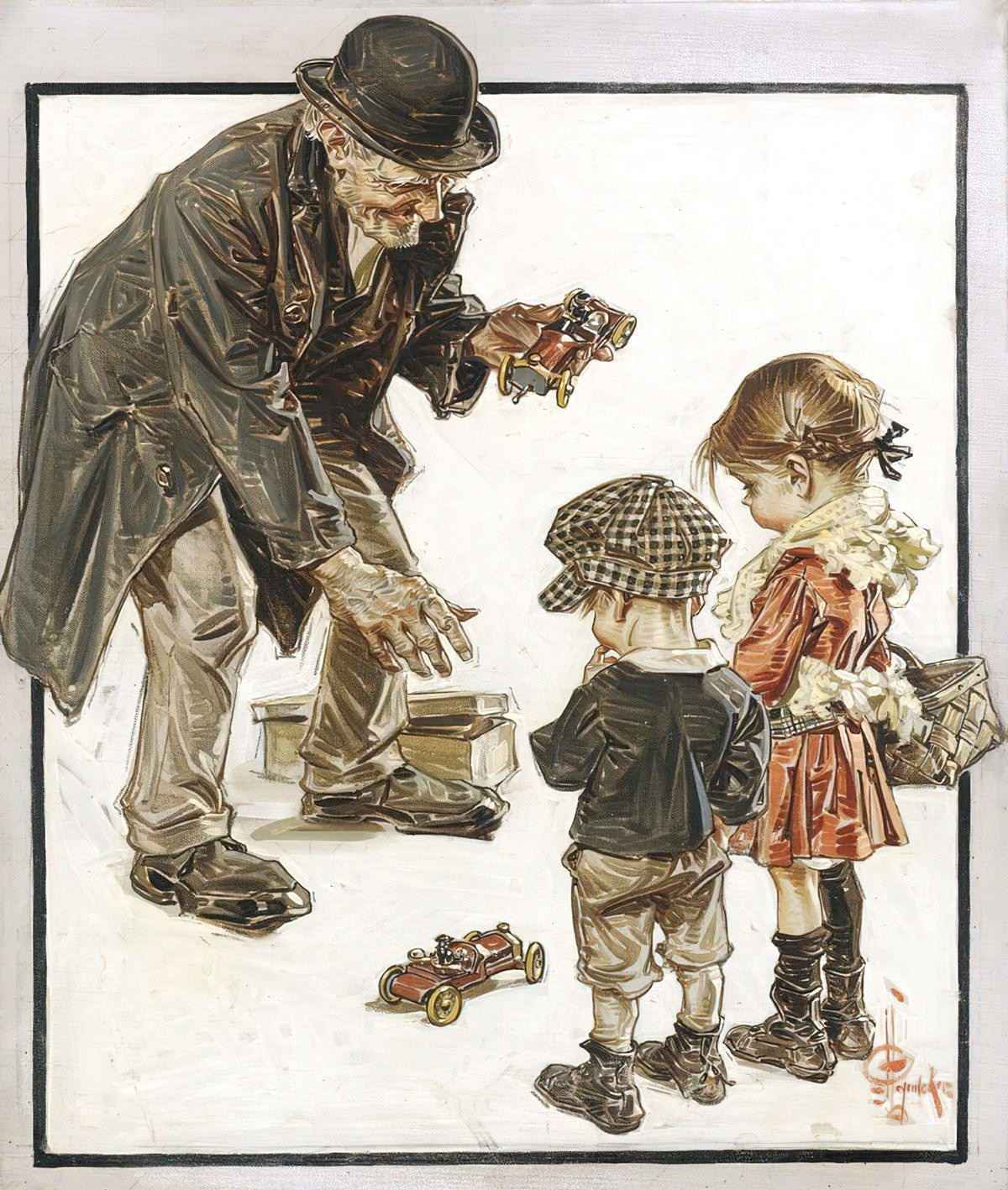

OPPONENT

Harvey (the uncle) is clearly opposing Eleanor (the boys’ mother) by introducing toys which are boring as hell. He must already believe that ‘boys will be boys’ (a take on my own parents’ 1980s view that ‘boys will turn a stick into a gun even if you don’t hand them a toy gun’). By giving his nephews ‘a municipal dust-bin’, ‘a distinguished civilian’, and ‘a model of the Manchester branch of the Young Women’s Christian Association’ he is conducting a layperson’s science experience of false equivalency. There is no way to discern from this whether the boys are drawn towards war, specifically, or whether they are drawn towards change (which might include spiritual battles rather than actual ones). I believe imaginary games conform to universal storytelling principles. It’s not the shoot em ups that engage us, necessarily — it’s the melodrama of life and death situations, and the opportunity to imaginatively explore the meaning of life by comparing life to death.

There is also an assumption, no doubt held by the mischievous trickster archetype of the uncle, that toys are the main ways boys learn to be violent. Only the mother suggests that the boys may have been conditioned to show interest in war by dint of… living in an era cranking up for a stonkin great World War. Do we side with the mother, who is soon disappeared?

PLAN

The reader is clearly encouraged to take the world view of the uncle, however flawed his experiment. Trickster archetypes are always popular with readers. This master spoofer has gone to great lengths in preparing his gifts, and he entertains us.

The mother, with opposing views, is a classic Mature Female, and we see very little of her. (We side with the ‘active’ character — the guy who makes the plans.)

THE BIG STRUGGLE

Now that H.H. Munro has encouraged us to side with the fun uncle, we are encouraged to interpret his argument as a win: the argument which assumes boys will naturally use ‘peace toys’ to start an imaginary gory fight, repurposing peaceful toys for wartime purposes.

The reader will likely see this coming, no matter our starting ideology. Harvey’s is the dominant historical view, after all.

ANAGNORISIS

Some readers will have their pre-existing view confirmed: That boys will be violent no matter what toys you give them. This may elicit a knowing chuckle.

Other contemporary readers, including myself, have realised just how long this naïve, simplistic view of character-building has been talked about and written about. It’s depressing.

NEW SITUATION

Harvey rushes off to find his sister. He tells her that the experiment has failed, and that “We have begun too late”. My read, given the uncle’s actions: He doesn’t really believe that there was any perfect age at which to start gifting his nephews peace toys; he offers this interpretation to pacify his sister or to avoid a nature versus nurture debate.

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

Munro was killed in a fox hole, right after he told a nearby soldier to extinguish his cigarette. It is believed the burning ember of his comrade’s cigarette which led to Munro’s slaughter on the battlefield.

Knowing this, and knowing the era in which he lived (and died), it’s no surprise that Munro’s basic view of humanity led him to the conclusion that men are irredeemably violent.

RESONANCE

The view of humans as naturally and irredeemably violent has changed somewhat, with the observation that humans are becoming less violent over time. This view was popularised by Steven Pinker in his 2011 book The Better Angels Of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined. I’m not recommending Steven Pinker, but his is the pop science tentpole book.

TOYS THROUGH THE AGES

Animal totems as symbols in folk rituals are common and go back probably further than any of us can track. By far the most prolific of these is the hobby horse. Often associated with calendar customs as well as an accompanying figure for many Morris dance sides, there are a number of common varieties of hobby horse and they are found in customs around the world.

The Folklore Podcast