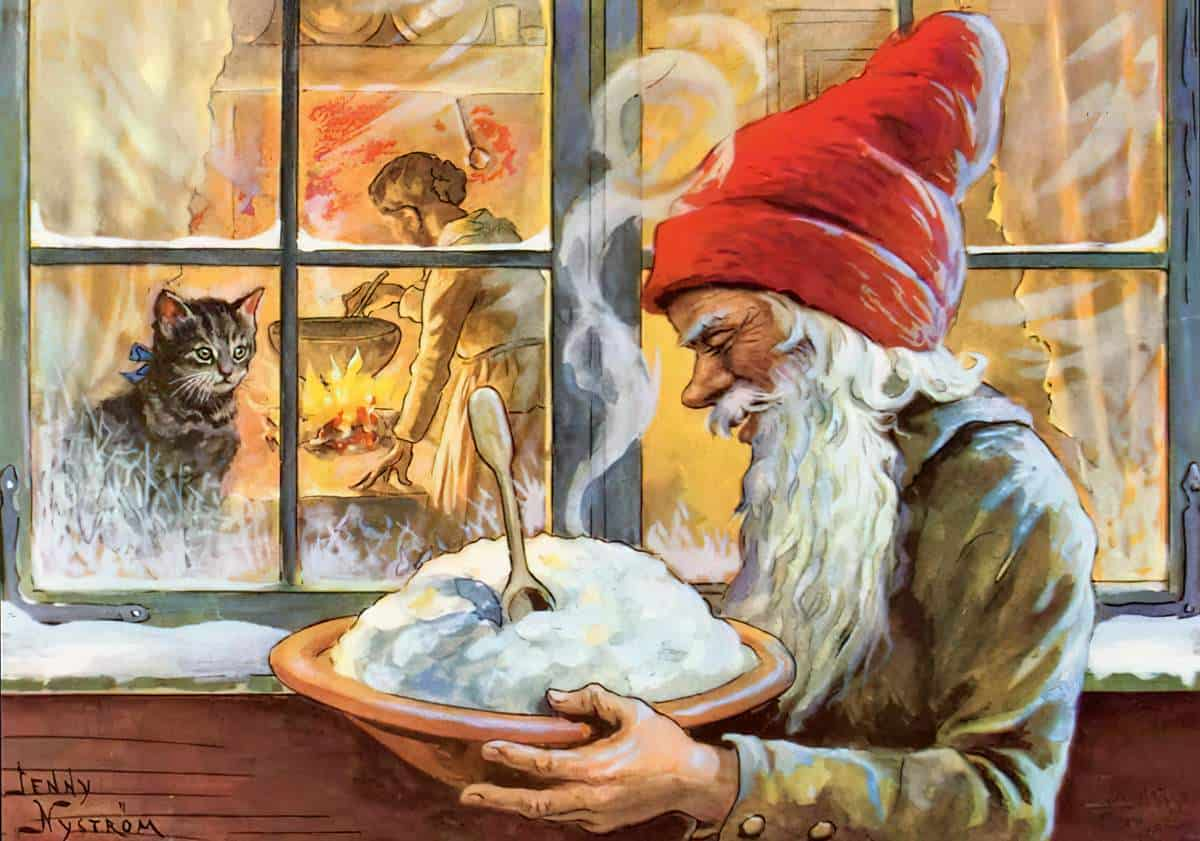

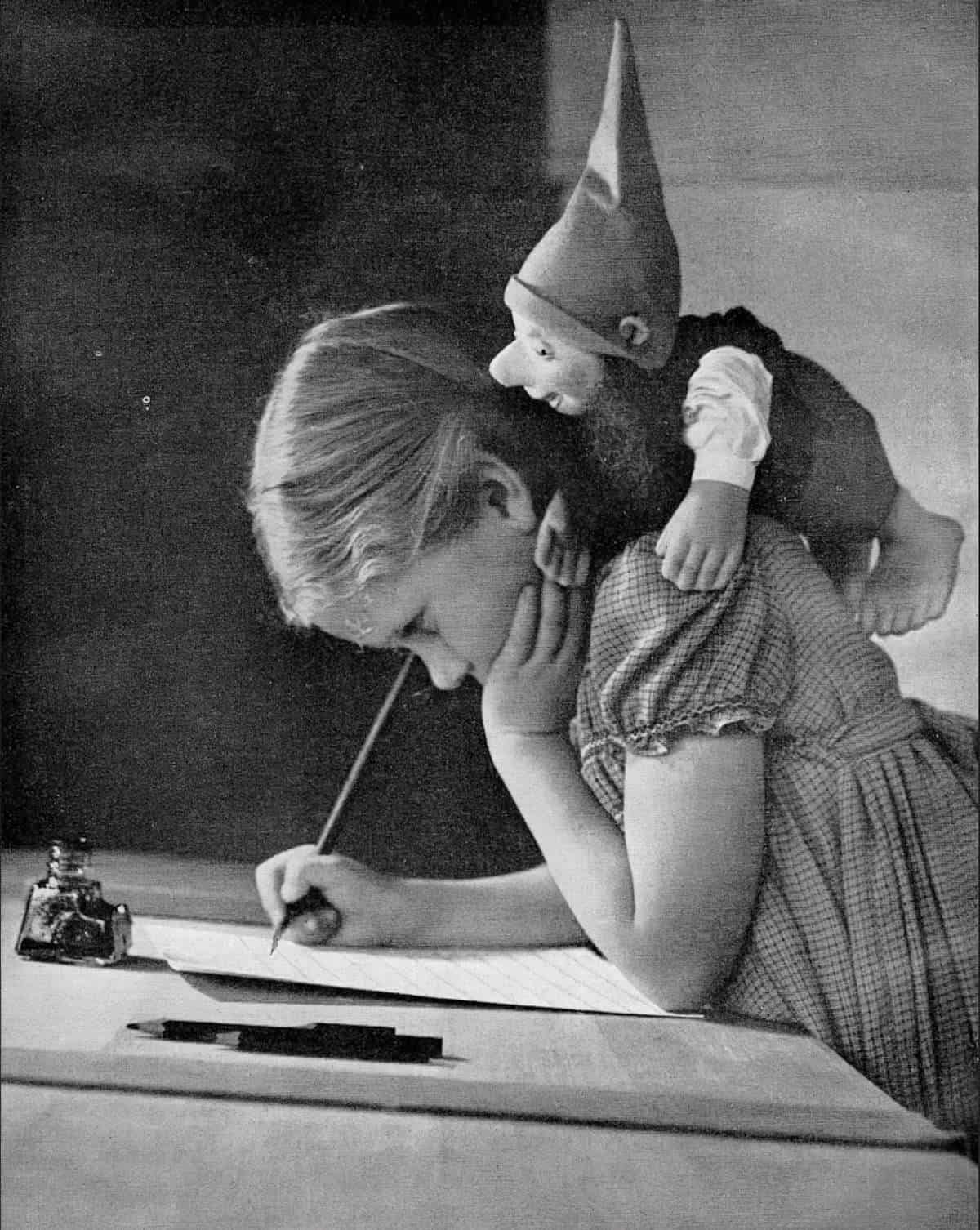

The Tomte is a Christmas creature from Nordic folklore. Tomte is Swedish, and the other Scandinavian countries have their own versions — in Norway known as Nisse. In English, think of your archetypal garden gnome, with his long, white beard and red cap. Tomten also translates as “homestead man”, and some English translators just stick with “troll” for every Scandinavian creature.

Saying “The Tomten” doesn’t sit well with bilingual speakers of Swedish and English. Calling tomten “The tomten” is like saying “The the gnome” because the “n” at the end of Tomte already indicates “The”. Likewise with Nisse and Nissen. However, when words are borrowed into other languages, grammar doesn’t come with. Forgive my usage of ‘The Tomten’ and ‘a Tomten’ — English language children’s book publishers have run with it for decades.

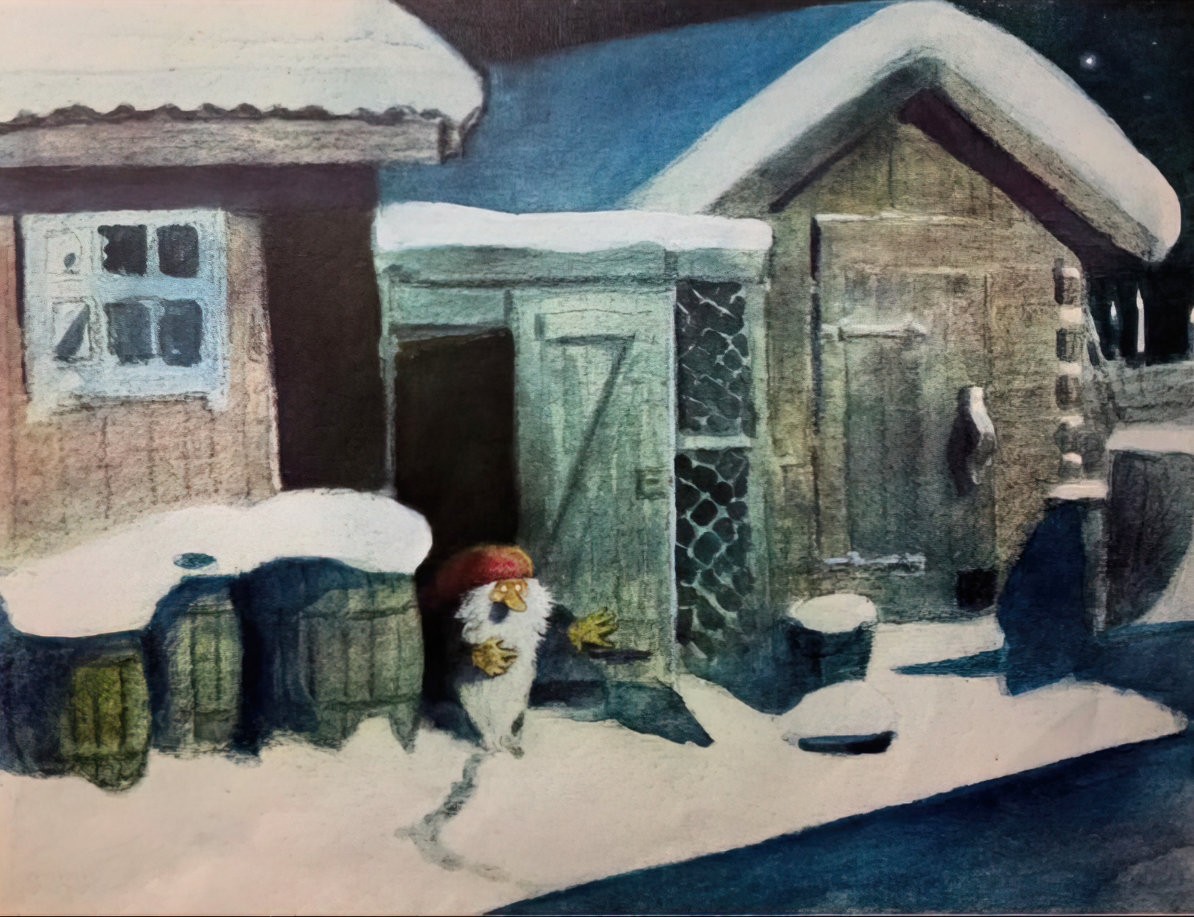

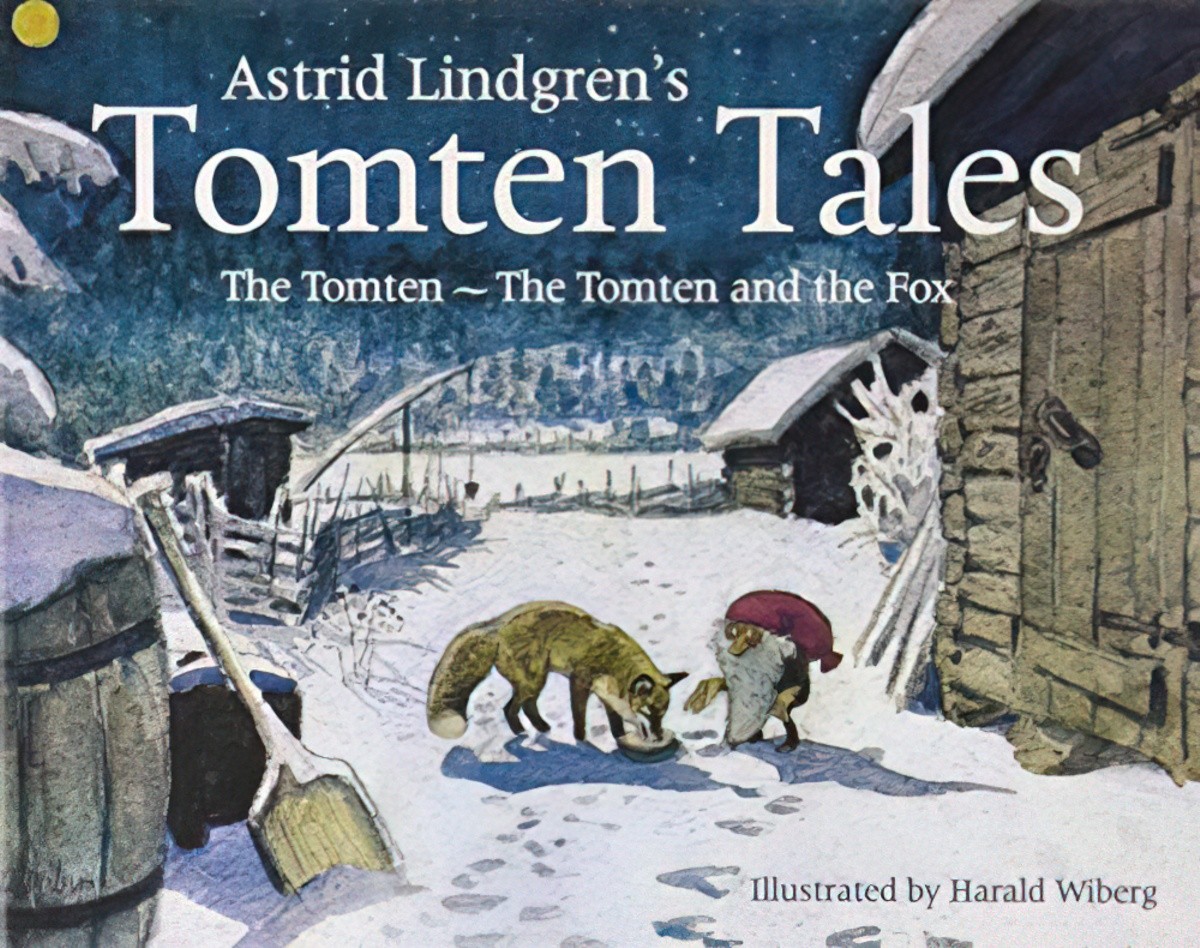

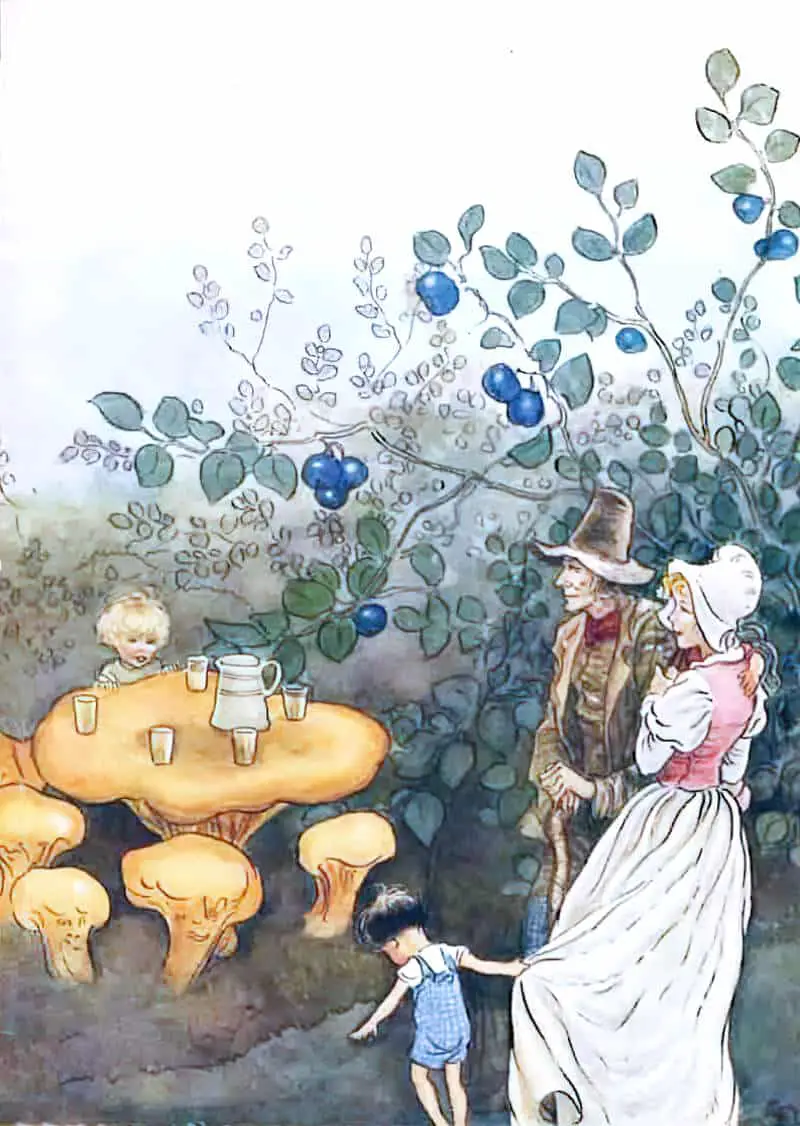

Case in point, The Tomten and the Fox is a tomte picture book for children written by Astrid Lindgren, of Pippi Longstocking fame. Harald Wiberg, a Swedish Children’s Book Illustrator, and wildlife artist illustrated an earlier edition. Like any classic tale, there are numerous retellings illustrated by various artists. Belgian artist Kitty Crowther has also illustrated the Lindgren retelling in a more cartoonish, less painterly style, I assume to attract a modern child readership and make it a bit less… creepy.

The creature is straight out of Nordic folklore, and the story itself is based on an old poem by Karl-Erik Forsslund (1872-1941). I can’t easily find this poem, but came across other sources crediting the inspirationalTomten poem to Viktor Rydberg, originally published in 1881. It’s possible that two men both wrote poems about Tomten around this time?

Using Harald Wiberg’s beautiful illustrations, Astrid’s prose version has been adapted for short film. I watched this mid-afternoon, started yawning uncontrollably, then lay down for a very pleasant afternoon nap. Now I’m back, I can tell you that this tale is perfect for putting kids to sleep. Listen to the cadence, which works hypnotically even in English.

THE STRUCTURE OF LULLABY STORIES

For those still awake, I’d like to point out that the story structure is very similar to that of Goodnight Moon by Margaret Wise-Brown. A creature or camera moves from place to place or from object to object, seeming to check up on it, with the covert message that everything is fine, because it will still be there, as expected, even after the child wakes up. Whereas Margaret Wise-Brown is confined to a child’s (?) bedroom (the bedroom has a telephone), The Tomten poem guides us gently around a dark and snowy farm. The snow itself functions as a cosy blanket in what might as well be a bedroom.

These lullaby stories are the rare exception to the ‘rules’ of complete narrative. They do satisfy the intended audience, but don’t contain the steps of every other kind of story in the world. Perhaps this is precisely because they are designed to send a child to sleep. Sleep is the ending.

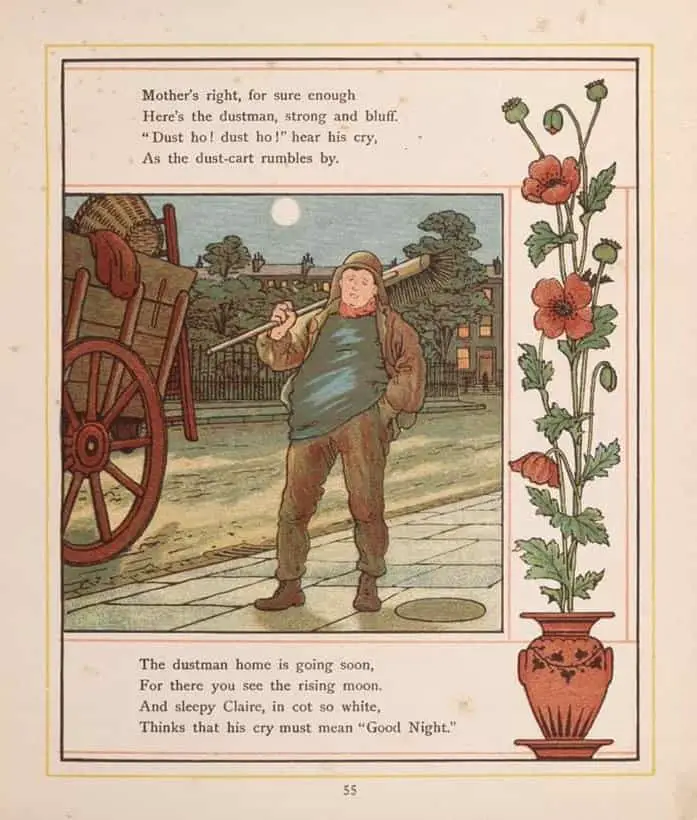

FOLKLORIC CREATURES PEERING AT CHILDREN THROUGH WINDOWS

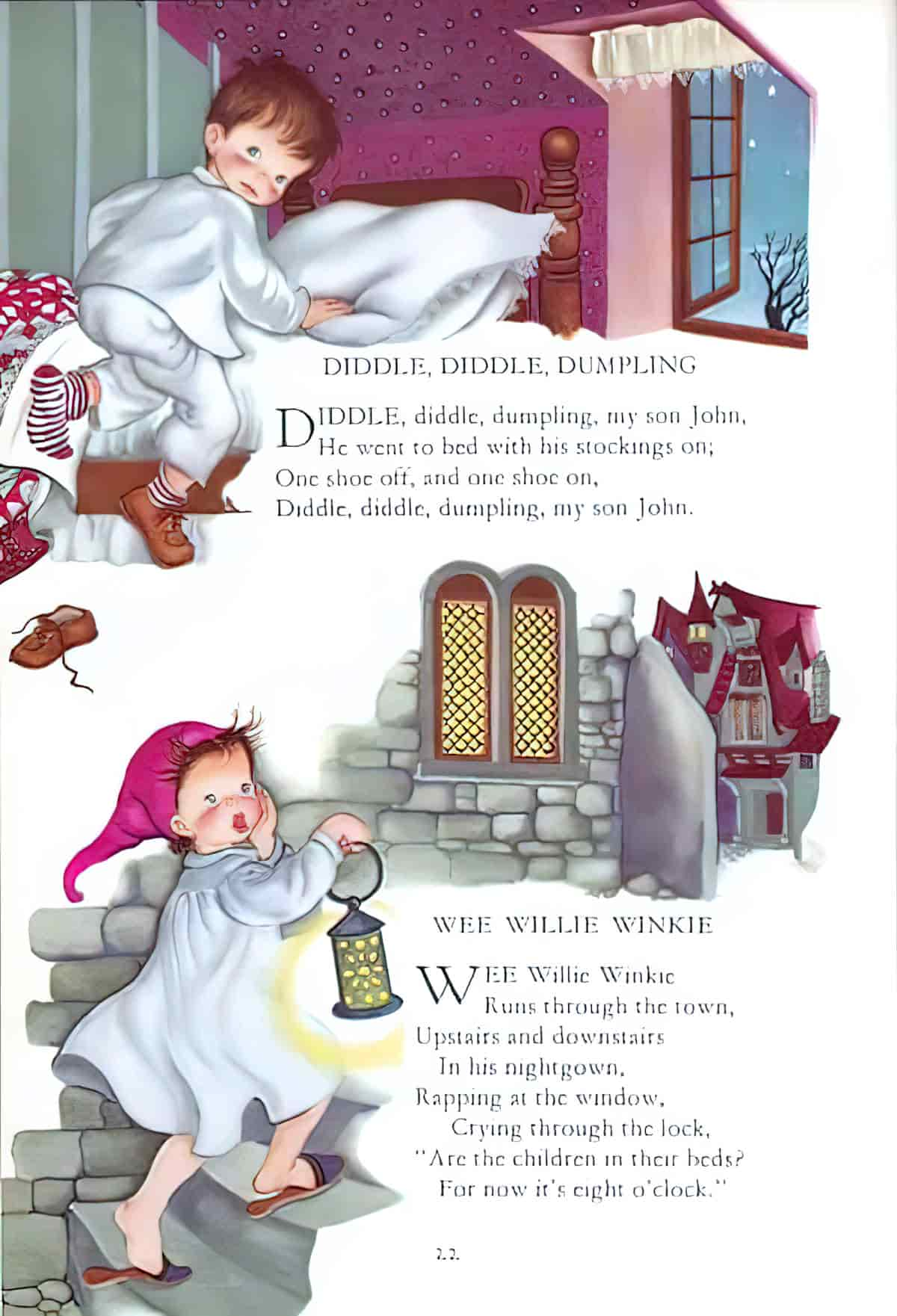

I am not Scandinavian and did not grow up with tomte mythology. Here’s a poem in a late 19th century children’s book about scary creatures sending children to bed:

My ancestry is Scottish so I was spooked by threats of Wee Willy Winky instead.

Wee Willie Winkie rins through the toon,

Up stairs an' doon stairs in his nicht-gown,

Tirlin' at the window, crying at the lock,

"Are the weans in their bed, for it's now eight o'clock?"

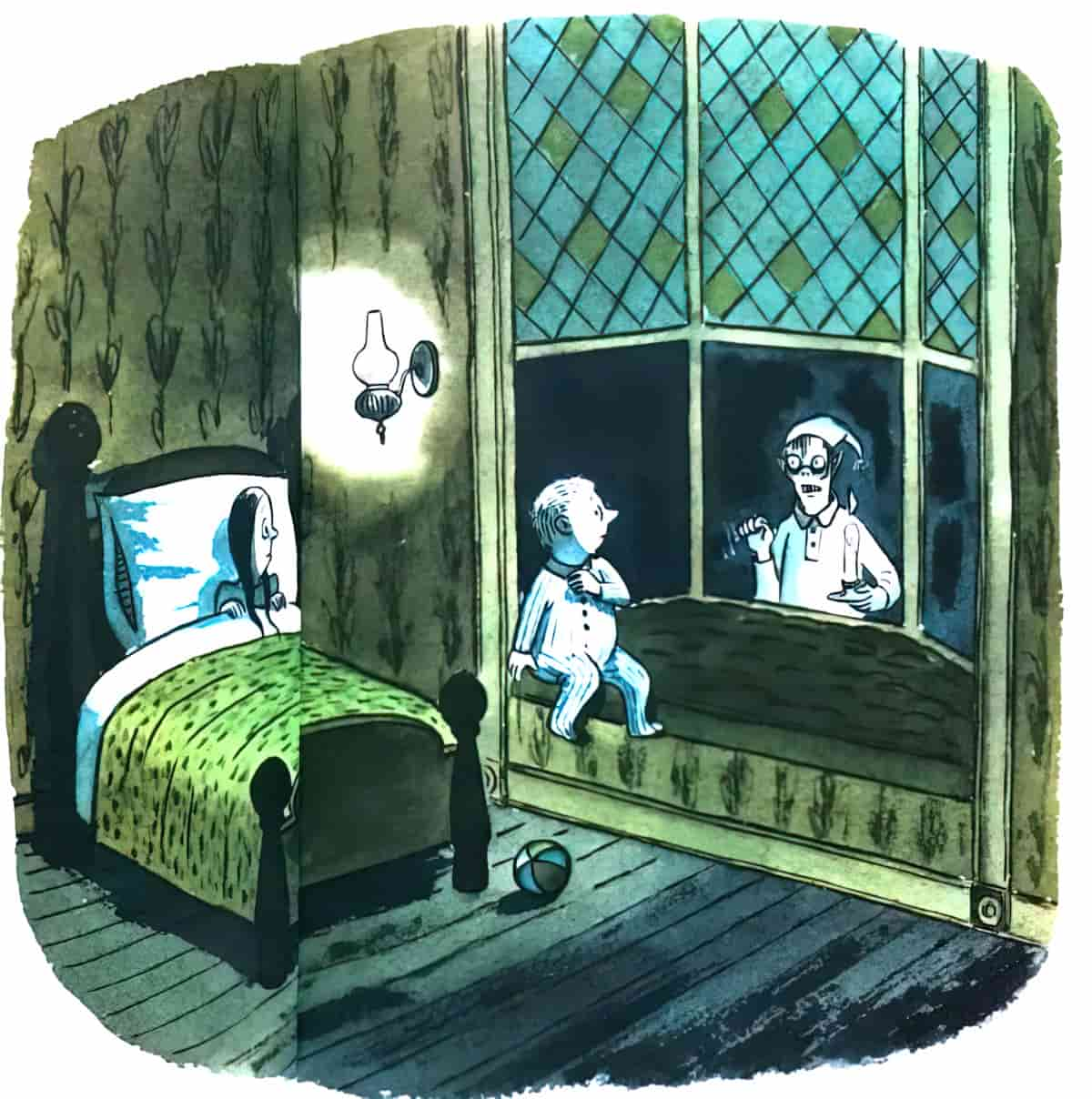

Now that I’m an adult, I code Wee Willie Winky as a pedophilic peeping tom. (If you’ve listened to podcasts about the Golden State Killer, you’ll hear police officers saying that peeping toms are more common than commonly believed.)

The tomte story does not give me the same creepy vibe as Wee Willie Winky. I wonder if I was scarred by Willie as a child. Once I’d been ushered into bed I’d pressed my ear to my pillow. I could swear I heard his footsteps pacing down our gravel driveway. I now know that I was hearing my own blood. No, that’s not creepy at all.

Or perhaps there’s some fundamental difference between Willie and the Tomte. Perhaps Willie’s creepiness comes from his night-gown, which makes him less supernatural, more human. (Then there’s the unfortunate other meaning of ‘wee willie’.)

Is the tomte scary for Scandinavian children? This 1941 short film (in Swedish) has a Noseferatu vibe and I wouldn’t try putting kids to sleep with it. The Tomte can be either cosy or scary, depending on treatment. Same as monsters.

I was basking in the warm glow of a familiar, beloved story from my childhood, they were creeped out that little men might be walking around the house while they were sleeping looking in windows. Matter of fact, one of my boys came and crawled into my bed about 20 minutes ago. Guess that story backfired a little…

Goodreads reviewer

In common with Wee Willie Winky, the Nordic tomte is imagined by artists as peering through windows. Windows, in common with doorways and chimneys, are one of those liminal parts of a house where storytellers of yore imagine all sorts of dangers would rush in at night, killing the entire household.

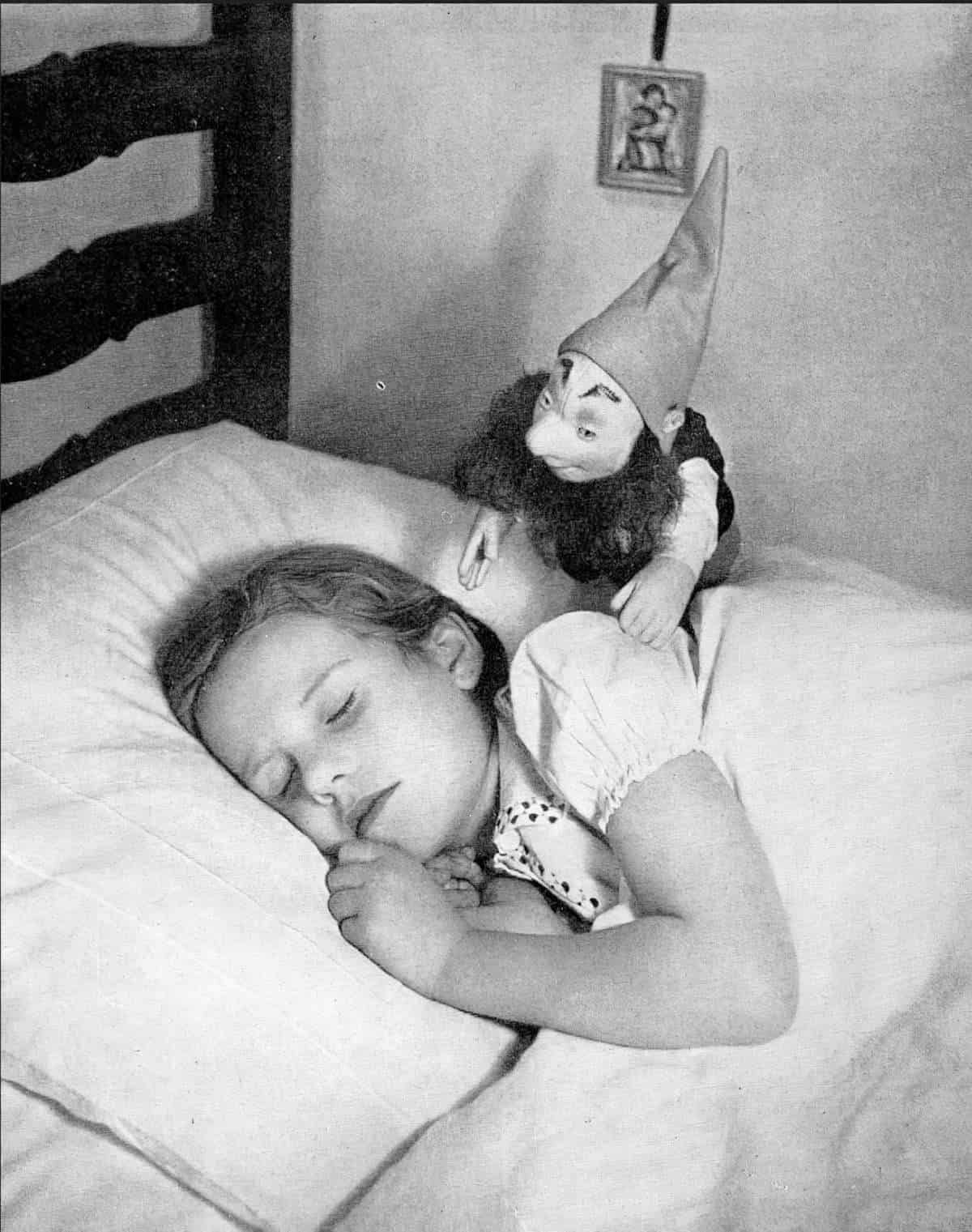

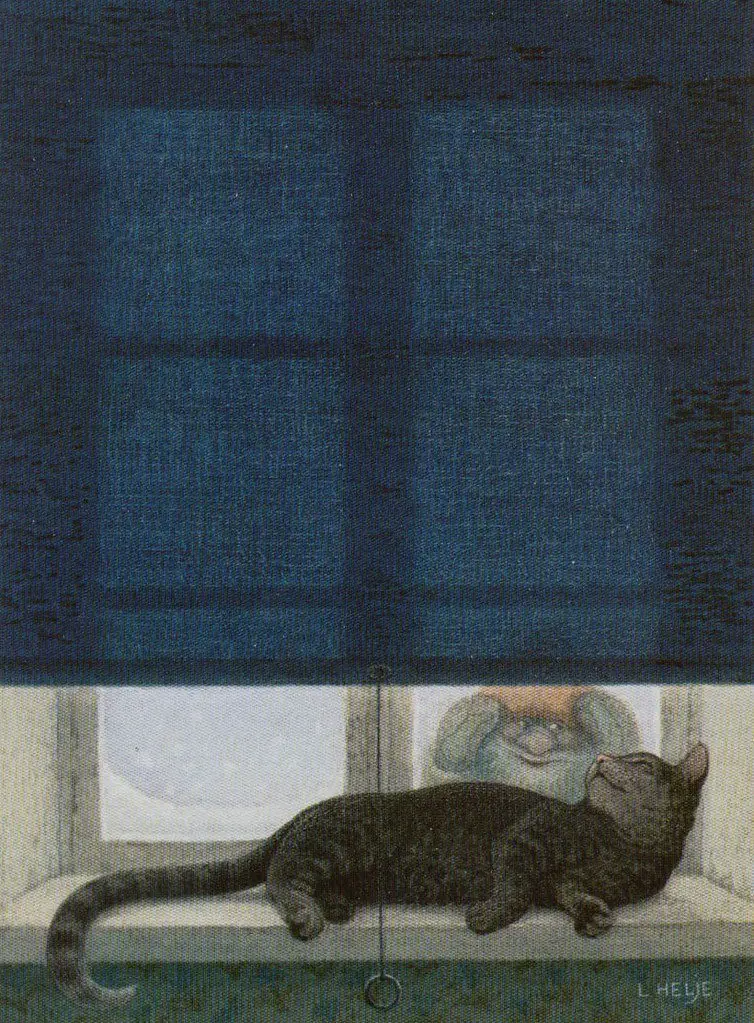

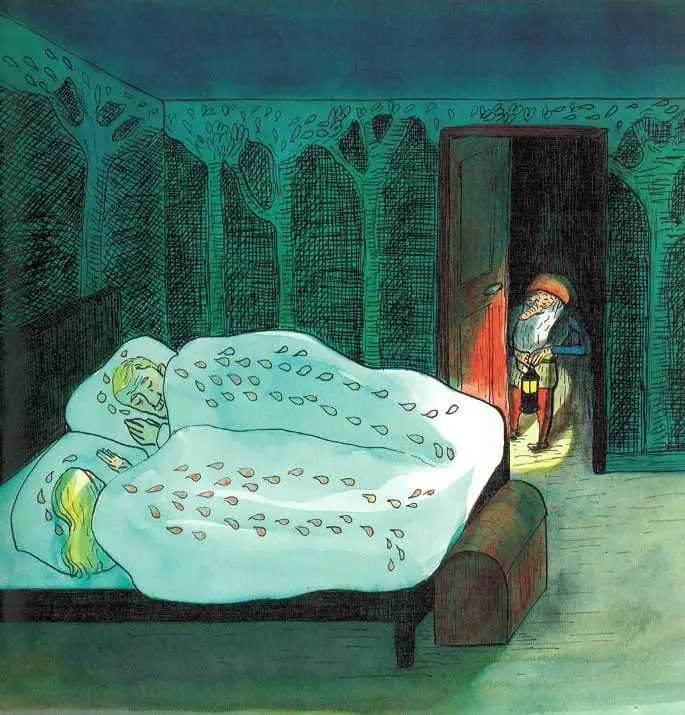

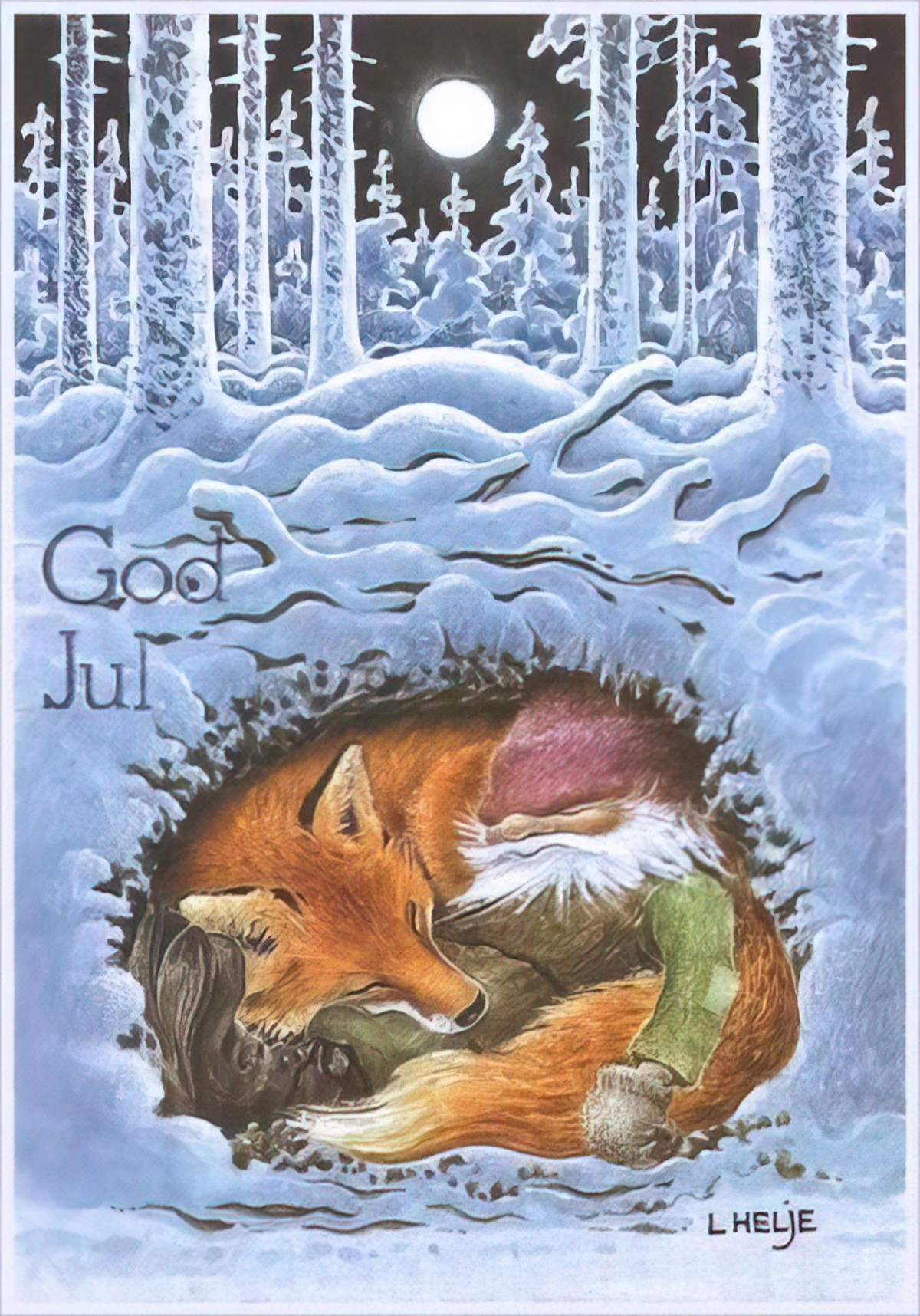

In the illustrations below, Lennart Helje offsets some of the peeping tom creepiness by showing him peering in at the cat (rather than at the children), who he is able to talk to in cat language. However, tomte stories will also show the little man staring fixedly at sleeping children. That’s what he does, after all.

There is another man of folklore who penetrates the safe home in winter to visit children as they sleep and that guy is Santa Clause. But Santa is presumably far too busy to hang around and stare at kids. If he’s not delivering presents he’s eating cookies and milk. Santa wears the same red cap, the same white beard as the tomte. The origin folklore clearly overlaps. (No, Coca-cola did not invent Santa as we know him today.) Santa’s red outfit comes from civil war cartoonist Thomas Nast in the 1870s, who would’ve been influenced by gnomes.

See also: A Pictorial History Of Santa

SETTING OF THE TOMTEN AND THE FOX

- PERIOD — around Christmas time, when the days are very short, the nights very long.

- DURATION — over a night time, but repeated. Every night, all winter, every year. This is a cyclical story which conveys the idea that the tomte have been around for a very long time, and will still be around long after we’re gone.

- LOCATION — Scandinavia, specifically rural Sweden

- ARENA — A storybook farm, with just enough farm animals to keep a family afloat.

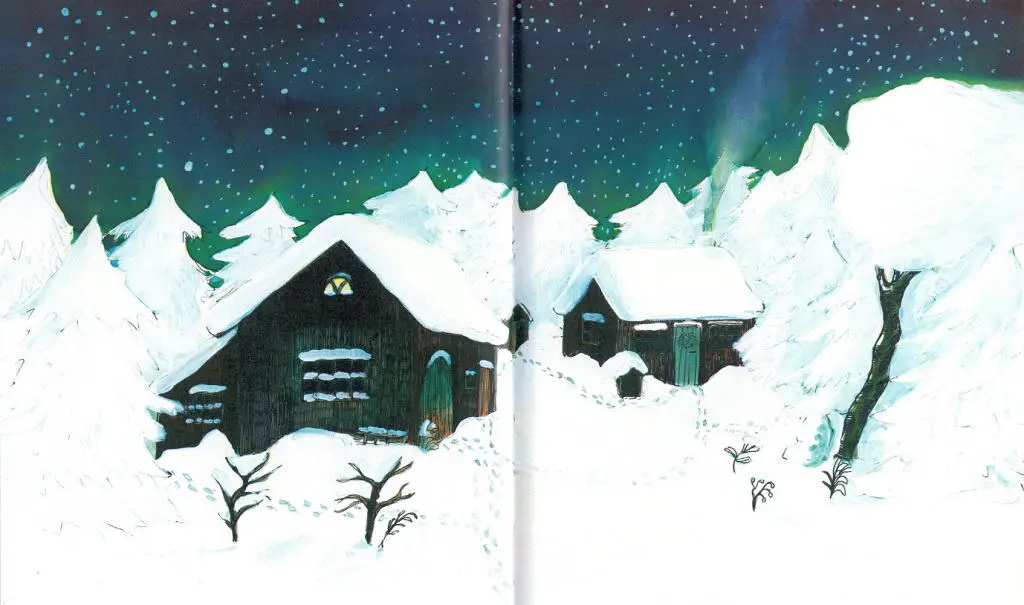

- MANMADE SPACES — farm buildings and the main house. Traditional Scandinavian farm houses are set up with a specific cosy layout, with buildings forming a mini ‘town square’.

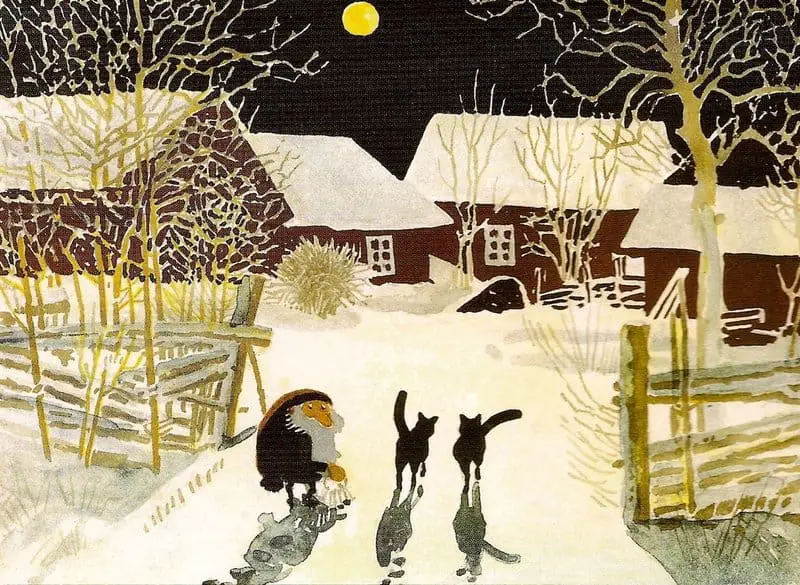

- NATURAL SETTINGS — The moon is out, which lights up the arena as if it were daytime. Night-time brightness is reguarly conveyed by illustrators but in Astrid Lindgren’s story, the brightness of the moon is mentioned right there on the page.

- WEATHER — It has always been snowing in a tomte tale. The snow is crucial to the story because tomte leave footprints. That’s the only clue that they exist.

- TECHNOLOGY CRUCIAL TO THIS PARTICULAR STORY — Only the farm technology is crucial.

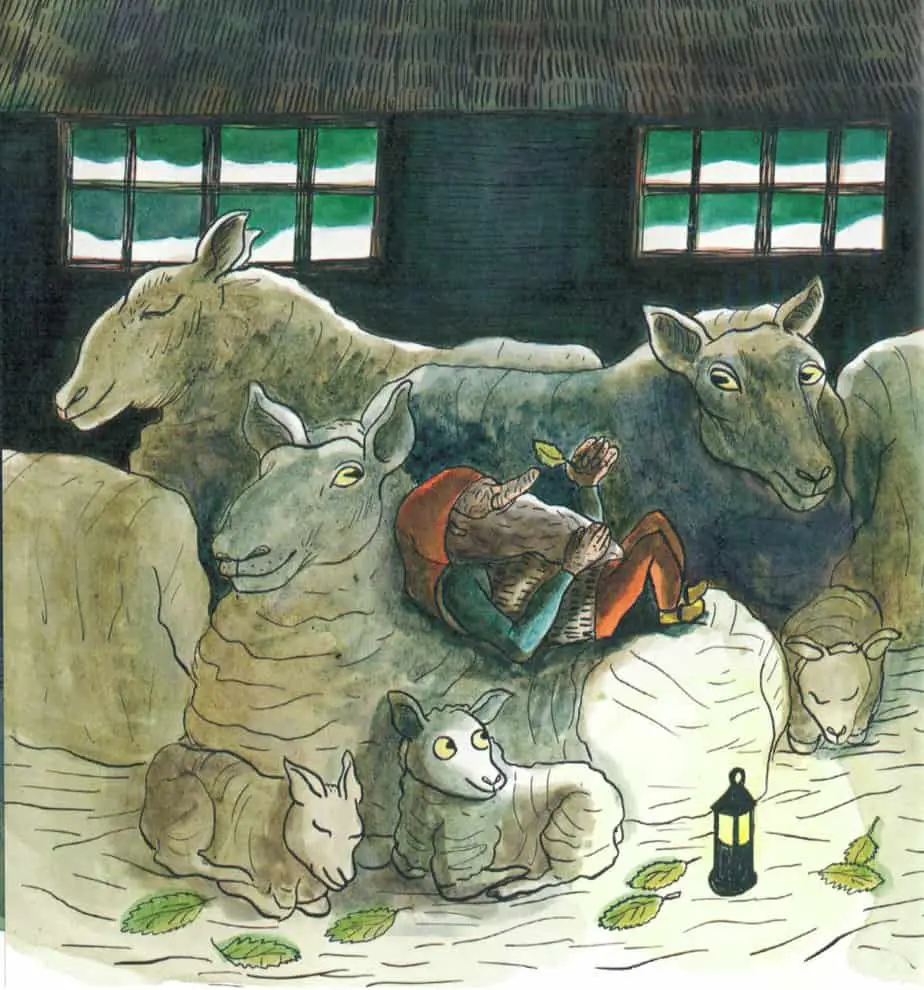

- LEVEL OF CONFLICT — This refers to the story’s position on the hierarchy of human struggles. From antiquity, humans imagine every emptiness occupied by higher forms of life ie. fairies. The tomte is a type of fairy, in the broadest sense. Fairies can fall anywhere on the spectrum of morality. This one has an apotropaic (protective) function. Winter is a dangerous time for people living in cold climes, reliant upon keeping their livestock alive. It would be comforting to think that a supernatural creature is keeping an eye on things, even as you sleep.

- THE EMOTIONAL LANDSCAPE — The winter is typically symbolic of death, quiet, sleep and contemplation.The Tomten and the Fox revisioning sets up the fox as the real tomte, for people who want an imaginative jaunt grounded in the logic of reality. But a child audience can choose to believe that those footprints belong to the tomte, not to the fox.

STORY STRUCTURE OF THE TOMTEN AND THE FOX (English Edition)

So, The Tomten based on the old poem is more lullaby than plot. But Astrid Lindgren wrote a whole collection of Tomten stories. Let’s take a closer look at The Tomten and the Fox (1966), because she beefed the earlier tomten lullaby poem out into a fuller plot. For that reason, it makes a good case study.

Wikipedia summarises the structural difference:

The Tomten

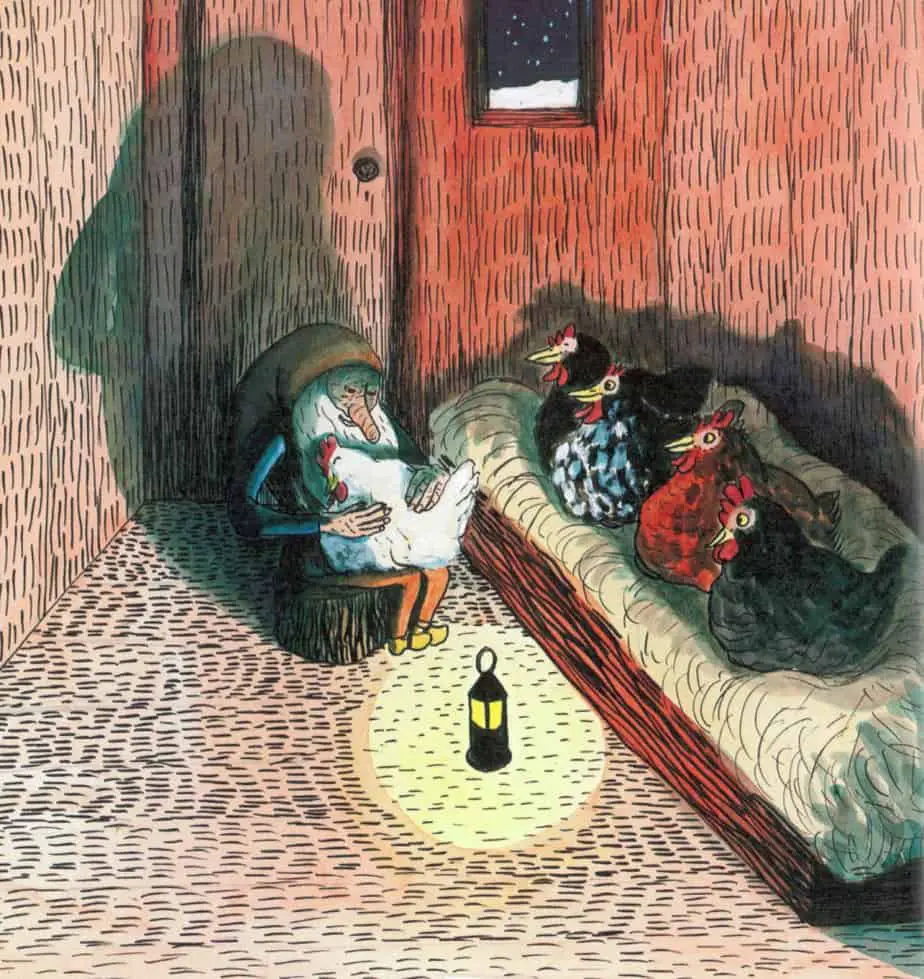

During the night the people at a farm in a forest are asleep. Only Tomten is awake. No one has ever seen Tomten, the people only know that he is there. Sometimes the people only find his small footprints in the snow. Tomten takes care of the animals and gives them comfort through a cold winter’s night. He promises them that spring will be there soon. Tomten also visits the children, who always want to see him. However, they are always at sleep when he comes, so they dream about him.

The Tomten and the Fox

The fox Mickel is hungry and hasn’t found food for a long time. At Christmas Eve he comes across a farm in the forest. He comes into the chicken’s stable and wants to eat a chicken. However, he is stopped by Tomten. Tomten knows how hungry a fox can be in such a cold winter’s night. When a child leaves a plate of groat on the doorstep for Tomten, Tomten wants to share it with Mickel. He tells Mickel that he would share it every night with him if he needs to. Mickel is happy, full and goes back into the forest.

Wikipedia

PARATEXT

No one knows when he came to the farm, no one has ever seen him, but everyone knows it is the troll Tomten who walks about the lonely old farmhouse on a winter’s night, talking to all the animals and reminding them of the promise of Spring.

marketing copy

SHORTCOMING

The family is vulnerable to predators who come out of the forest at night.

DESIRE

The Tomte has a job and does it well. He protects the farmstead from intruders, not by trickster business and violence but with kindness.

OPPONENT

The fox is named Reynard, a trickster archetype from medieval Dutch, English, French and German fables. Readers may know more about him from other stories. Reynard’s main opponent is the wolf. But Reynard is basically synonymous with any fox. In French, renard now means fox.

The fox has come from the woods (the mythical forest) to steal the chickens. Reynard is not just an enemy of the chooks, but also an enemy of the family reliant upon those chooks for food over winter. He may be just a fox, but this is a life and death struggle.

PLAN

The fox clearly wants to steal some chooks.

The Tomte’s job: to protect the chooks. Tomtes are supposedly vegetarian, I guess. They eat porridge with cinnamon and butter. The Tomte will keep the fox from the chooks by sharing his own porridge.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

The gentleness of the lullaby poem is retained. The fox doesn’t resist the tomte’s plan to feed him porridge, to prevent him from eating meat, but the hungry opponent does leave an aperture of doubt by failing to promise that he’ll stay away from the chickens.

ANAGNORISIS

Any revelation here is for the reader, who is hopefully comforted by the idea that there is a tomte looking out for them overnight.

NEW SITUATION

To give a sense of an ending, a storyteller will frequently pan the camera up into the sky.

What is the morning star?

In general, when Mercury or Venus has a western elongation from the sun, it is a morning star; with an eastern elongation, it is an evening star. Different planets may appear together in the morning or evening sky, depending on their location relative to Earth and the sun.

Space.com

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

Not so sure the Tomte’s plan accounts for bloodlust. I’ve kept chooks, unsuccessfully, from foxes.

RESONANCE

Partly due to the succcess of Pippi Longstocking, when Astrid Lindgren turned the Swedish poem into prose for children’s picture books, and once that had been translated into English, the tomte stories became more widely known in the English speaking realm. Alongside The Three Billy Goats Gruff, these stories are some of the better known folktales outside Scandinavia.

How has Kitty Crowther made the Tomte more relatable and less creepy? See the illustrations below for the answer.

FURTHER READING

Hedgie’s Surprise by Jan Brett is another children’s book about tomten.

What Do We Do All Day? has collected a list of Tomte picture books for English readers.

In Trip Trap I created a modern short story by blending Scandinavian mythologies, namely The Three Billy Goats Gruff and a spooky version of Tomten tales.