“Tobermory” is a short story by Hector Hugh Munro, otherwise known as Saki. Anyone with a pet has probably wondered what that pet would say to you if it could talk. Many children’s stories have this premise, and this particular wish fulfilment fantasy. We imagine if our pets could talk they would say satisfying things.

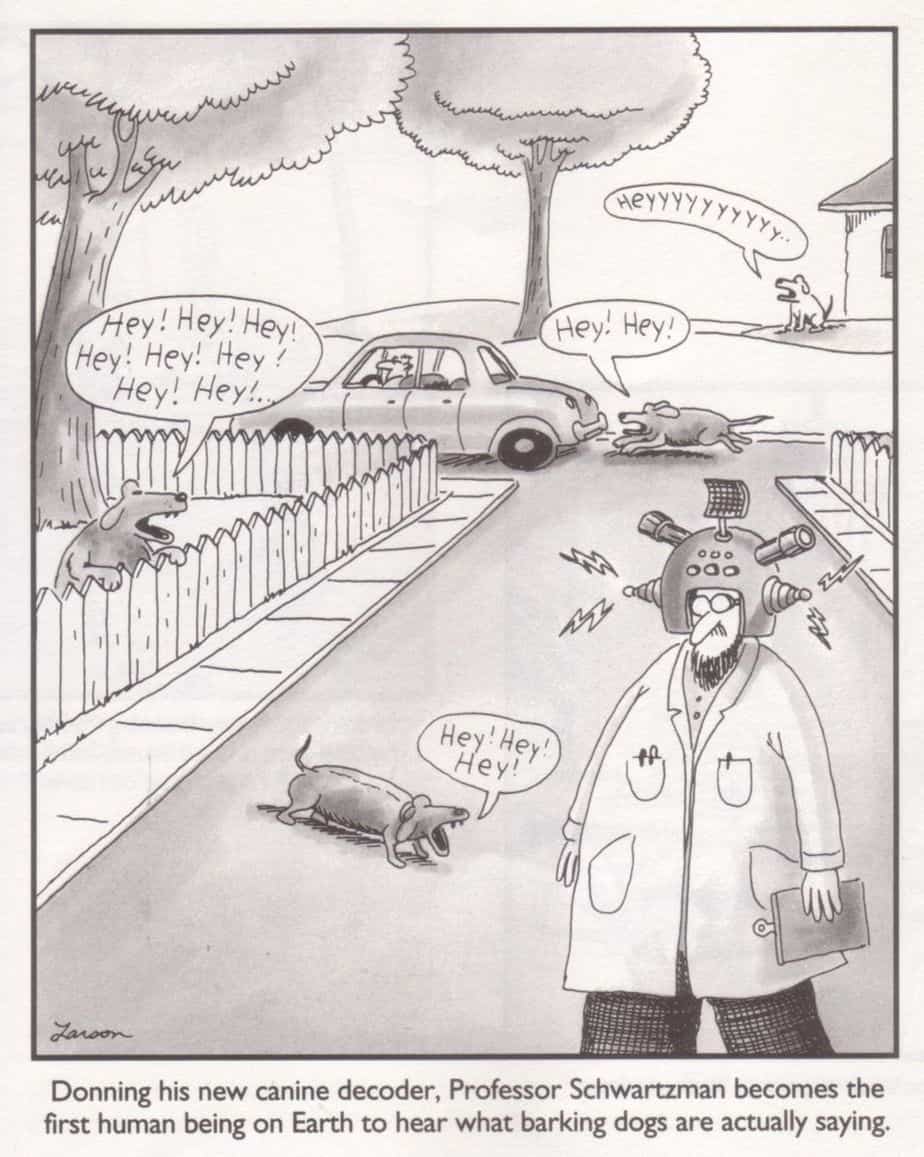

Saki’s story, about a talking cat, reminds me of a cartoon in which a man wishes his dog could talk. But as soon as the dog starts talking the man is weirded out and says, “You’ve seen too much.” He immediately takes the power of talking away from his pet.

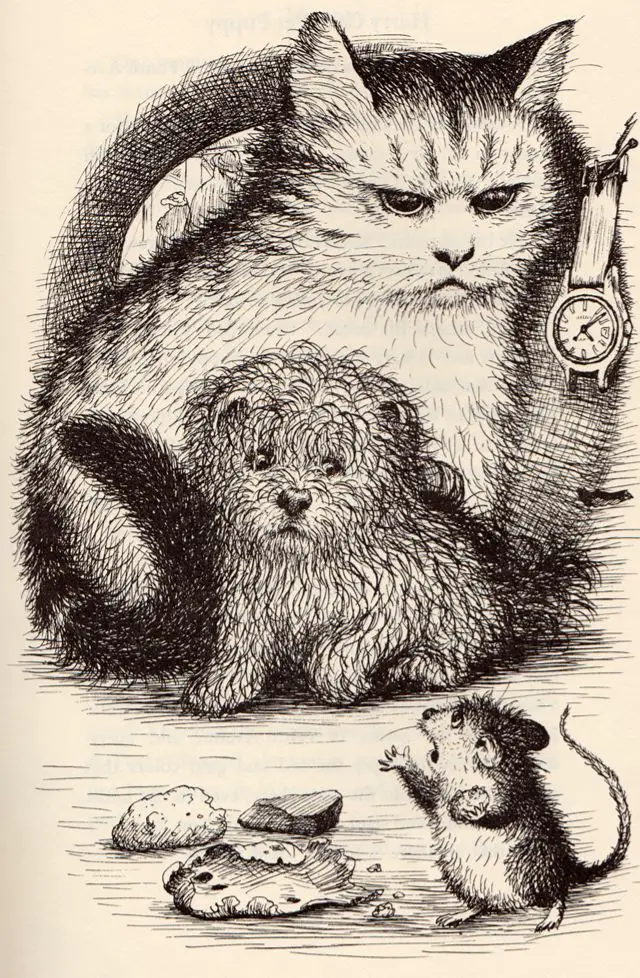

Gary Larson has also mined this gag, also on dogs:

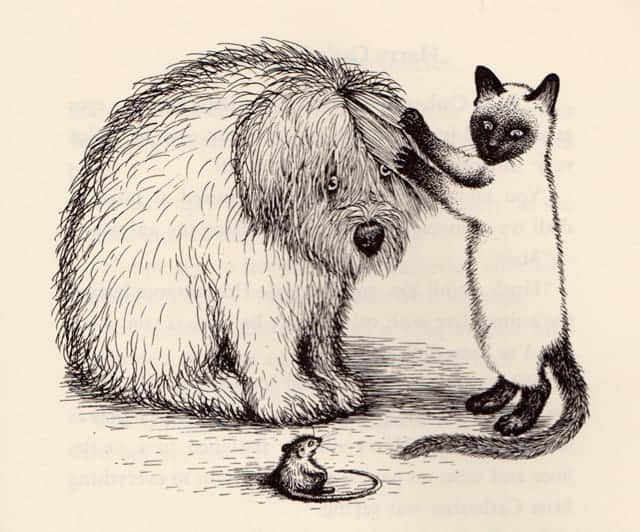

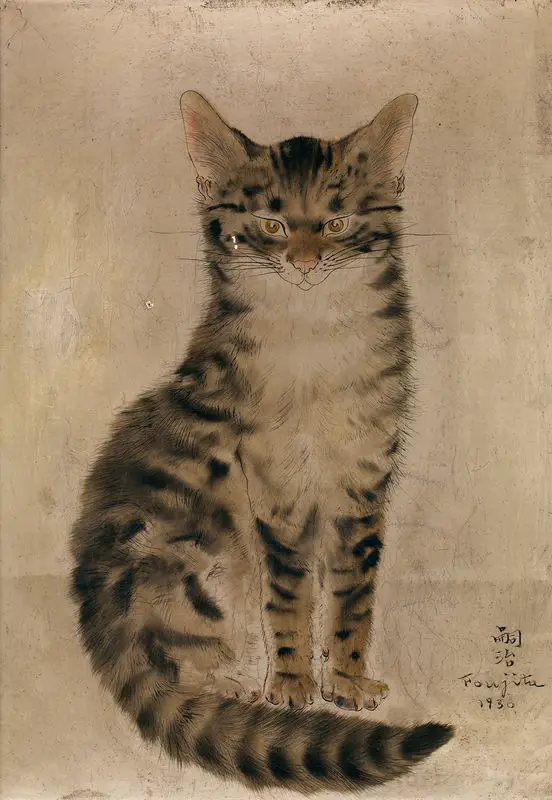

But cats are thought to be more circumspect. We consider them haughty, knowing and at the top of their own hierarchy. The heterodiegetic narrator of Tobermory is like a cat himself, and as viewpoint character, sees through bluff and bluster of the assembled human party.

The reality is that cats are more social than we think:

HUMOUR OF SAKI

The humour of Saki’s stories derives from an ironic gap between the highly formal register, most often used by the highly educated, and the subject matter, which is completely unbelievable. The register tips over into ostentatious and affected. Saki makes deliberate use of purple language such as ‘he expostulated’.

The comparisons he makes go way outside the bounds of the story itself. Here is a sentence which says ‘Cornelius Appin was crestfallen.’

An archangel ecstatically proclaiming the Millennium, and then finding that it clashed unpardonably with Henley and would have to be indefinitely postponed, could hardly have felt more crestfallen than Cornelius Appin at the reception of his wonderful achievement.

Australian author Kathy Lette writes in a similar fashion in some of her novels, such as The Boy Who Fell To Earth. This story gets a lot of its humour from its great many parenthetical asides.

It’s the ironic gap between register and subject matter that makes Saki’s humour feel irreverent. Add to that insights on human nature from his narrator and you have a wry social commentary. No better character than a talking cat to criticise humans.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “TOBERMORY”

SHORTCOMING

The great shortcoming of this group of people is that they don’t really like each other at all, yet here they are, all forced to commingle. They’ve been saying nasty things about each other behind backs.

DESIRE

Each has their own conflicting desire which they bring to the dinner party:

- Mr Cornelius Appin wants to demonstrate his wonderful invention (foiled because the invention is terrible)

- Sir Wilfrid does not want to be taken for a fool (foiled because he is revealed to be a fool anyway)

- Lady Blemley wants to be a good hostess (foiled by the cat)

- Mrs Cornett wants to be regarded a beauty (though she spends much time with make-up to get herself looking presentable)

- Miss Scrawen, ironically, doesn’t want everyone to know she leads such a good and virtuous life

- Odo Finsberry wants to keep his private life private since he is meant to be reading for the Church

- Agnes Resker wants to enjoy a free meal since she is experiencing financial hardship

- and so on

OPPONENT

The talking cat is the opponent, but only because the web of opposition has already been set up.

PLAN

Sir Wilfrid suggests they put strychnine in the table scraps and leave them out for the cat to eat.

The rest of the party do their best to paper over that a huge rift has emerged between the neighbours of the Tower.

BIG STRUGGLE

The Battle of cat eating poison and dying is subverted. The death happens off-stage in an unexpected fight with a Tom. On the other hand, this is entirely expected. We might imagine the cat was able to articulate nastiness to other cats as well as to other humans.

ANAGNORISIS

This story includes an entire cast of characters but Saki has chosen to home in on one character’s response to all this: That of Lady Blemley, who ‘sufficiently recovers her spirits to write an extremely nasty letter to the Rectory about the loss of her valuable pet’.

This is displaced anger, of course. And this is the reader’s revelation. People deal with humiliation by branching out with it. It’s called lateral violence, when it happens as part of a system.

NEW SITUATION

Saki finishes in children’s picture book fashion (also utilised a lot by Paul Jennings) in which another similar story happens a second time, but with a different main character. This time it’s an elephant, and the reveal is that the elephant learned to talk and got sick of an Englishman who was trying German irregular verbs on it.

The joke is readily understood by any English speaker who has ever tried learning German verb conjugation. (Though English is far less regular than German.) Note that Saki has not waited until the final paragraph to mention the elephant — one of the characters suggested elephants at the dinner party, since elephants can’t sneak about under chairs and whatnot and therefore make a safe subject.

It’s a good idea to prepare the reader in this way if you mean to end your short story like this. This is how you get your ending to feel ‘both expected and surprising’. Otherwise, readers will complain that the ending feels ‘tacked on’.

Elephants are an excellent choice for this final episode. My father remembers a traveling circus coming to the small town of Amberley. This was the 1950s. He and another boy rode their bikes to see the animals before the circus opened, one evening in summer. The friend had nothing to offer the elephant, so offered it a stone. The elephant took the stone in its trunk, perhaps thinking it was a peanut. But after realising its mistake, the elephant heaved the stone at the boy. The elephant seemed to know it had been tricked, then exacted revenge.

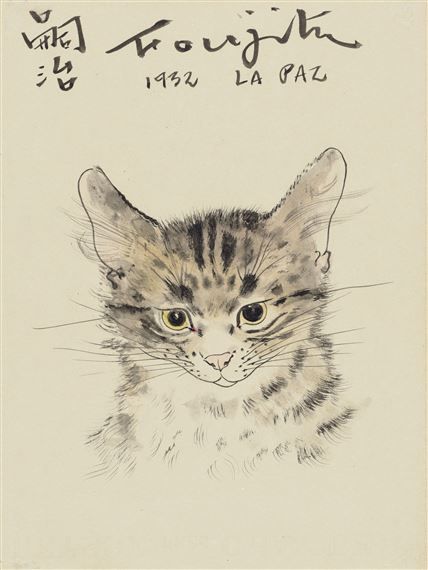

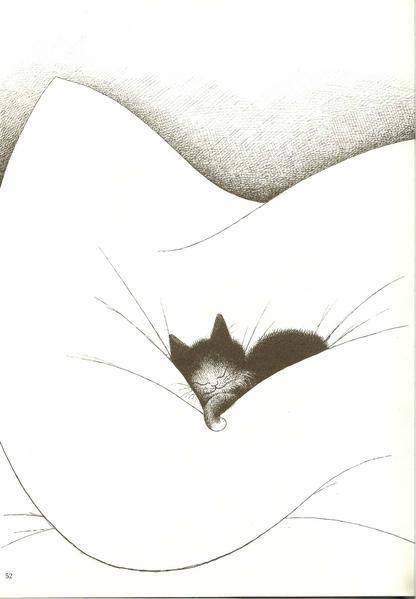

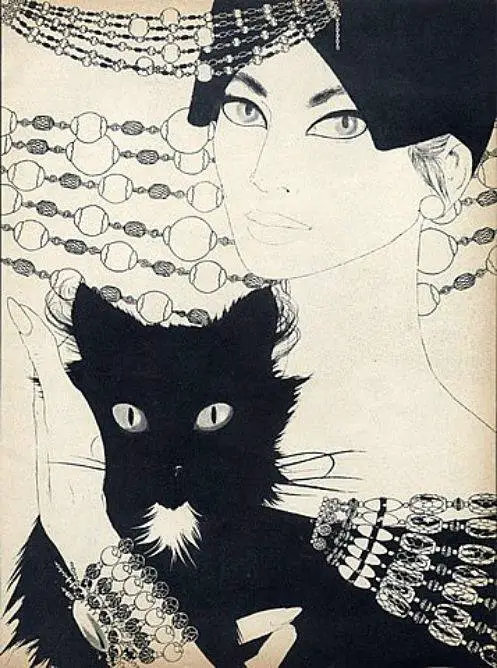

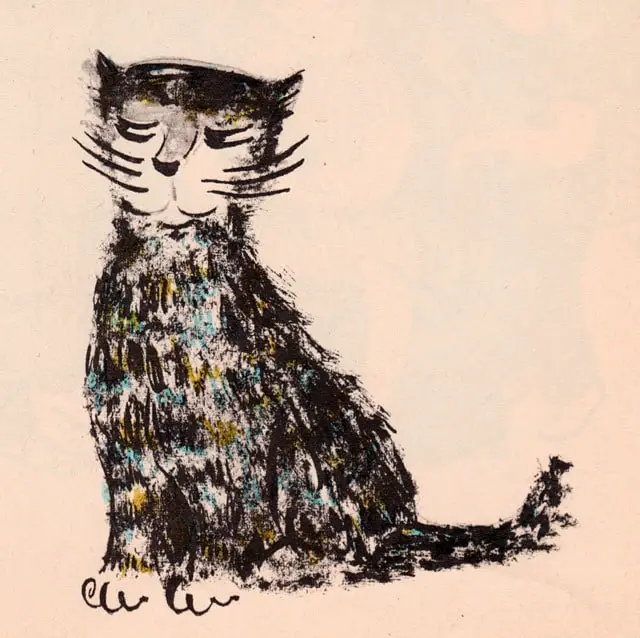

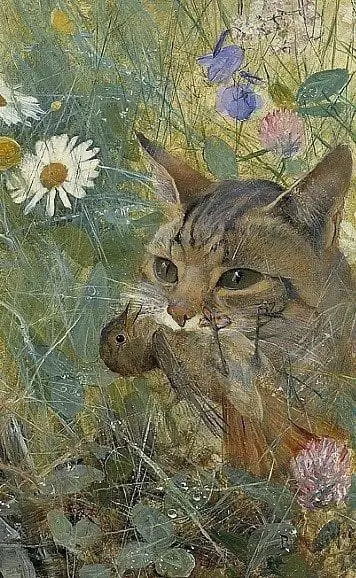

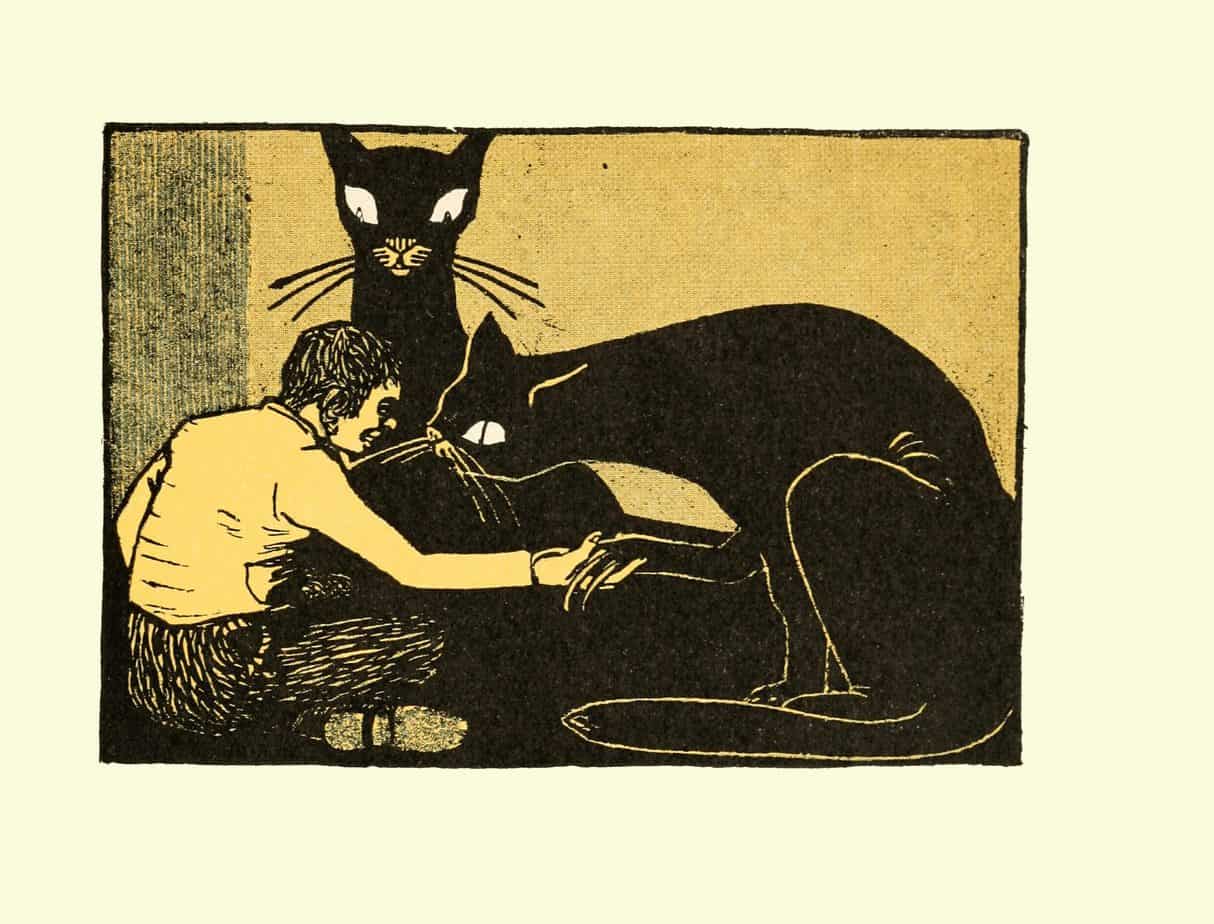

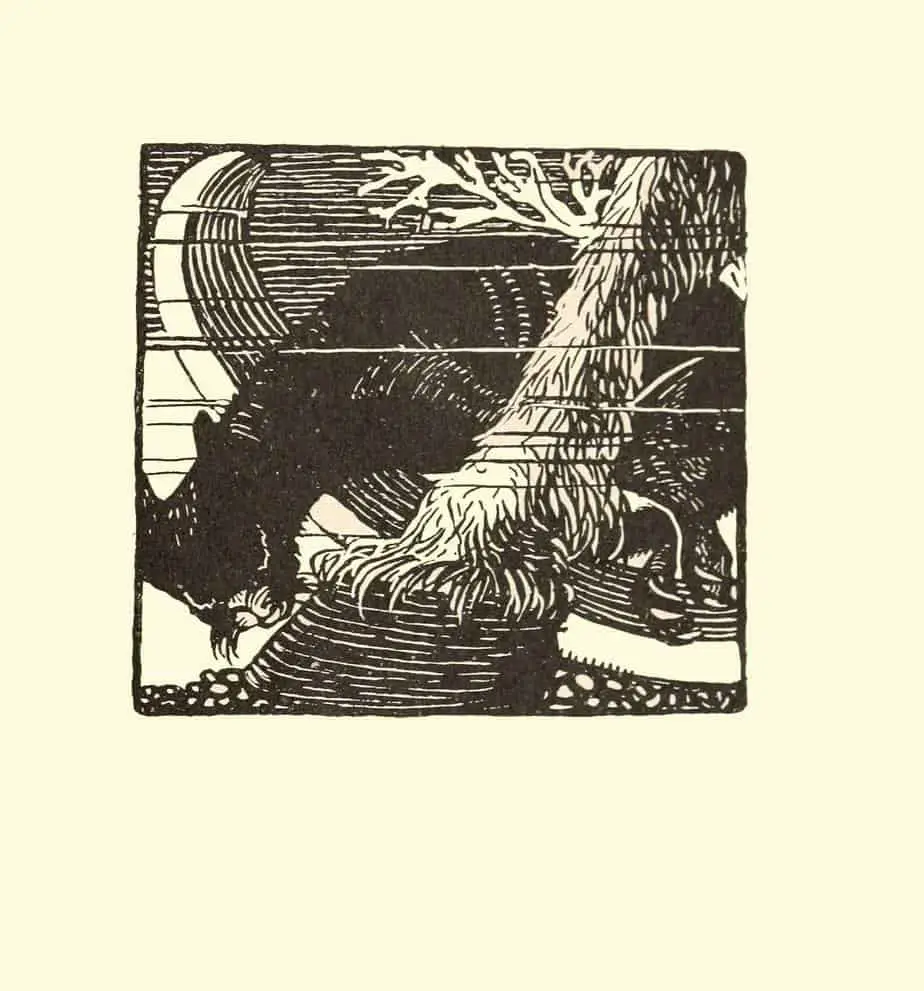

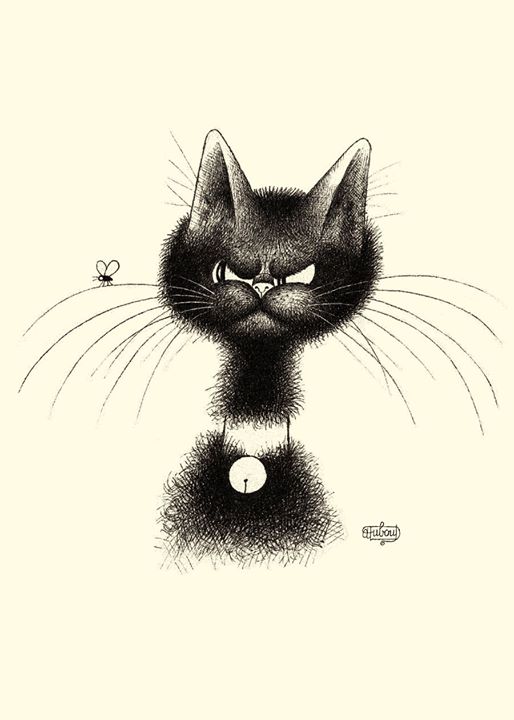

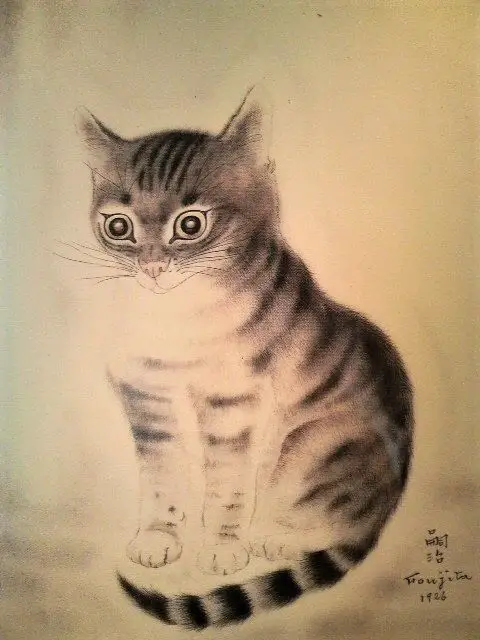

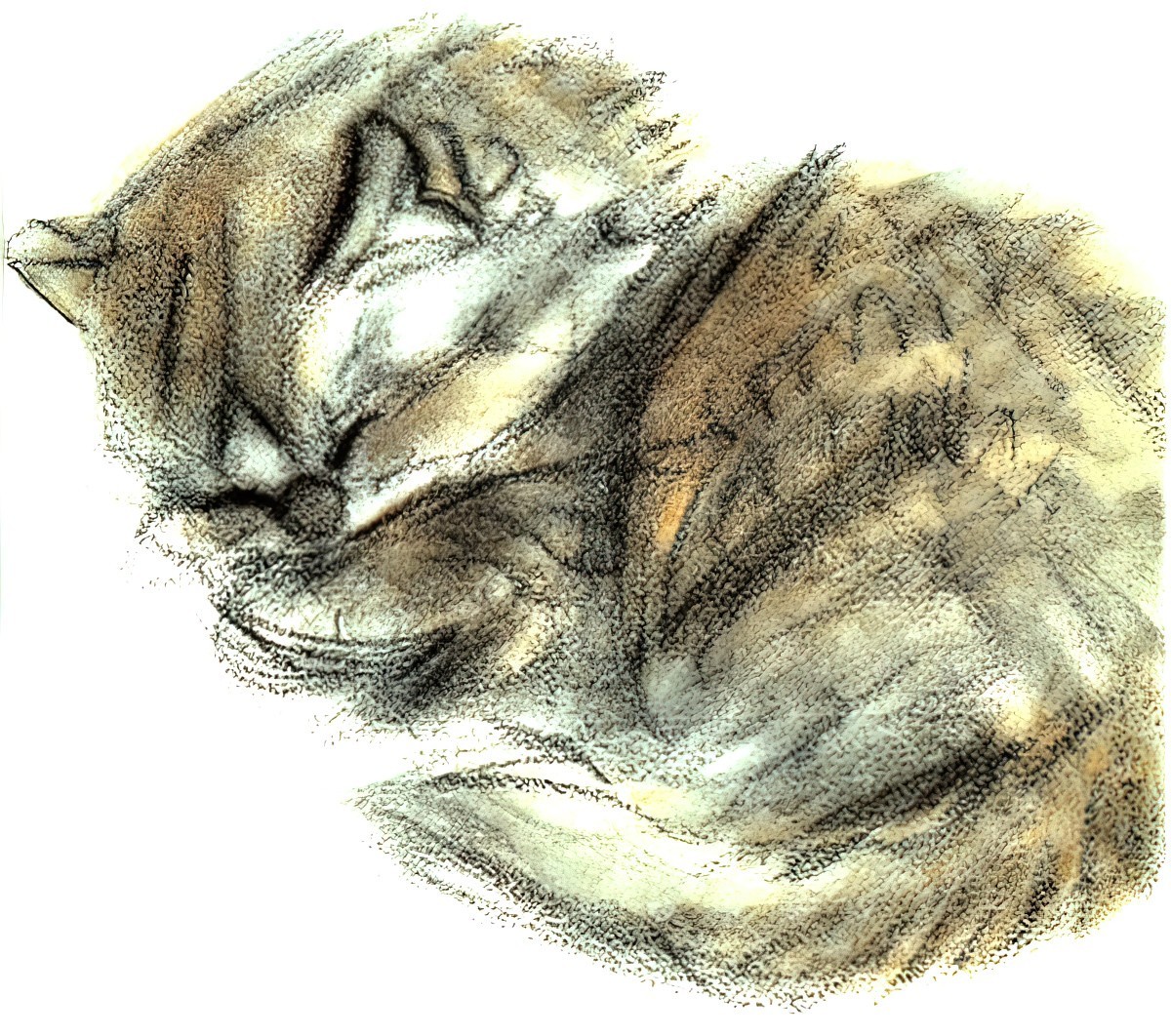

HOW WOULD YOU ILLUSTRATE THIS CAT?

The wonderful thing about cats is that they can be depicted in so many ways, from contemplative, gentle, silky creatures to mischievous tricksters to evil familiars.

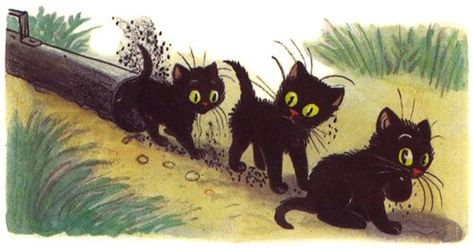

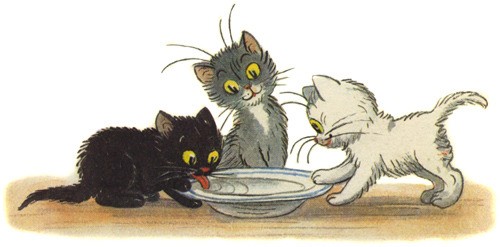

“Three kittens” V.Suteev (1963) Vladimir Grigorevich Suteev (5 July 1903 – 10 March 1993) was a Russian author, artist and animator

COMPARE AND CONTRAST

Compare “The Child” by Ali Smith, in which a woman finds a baby in her supermarket trolley. The child can talk, and it says nasty things.