Writing for a young audience has always been fraught, because children are thought to be more highly impressionable than adults. Tobacco, junk food, bad behaviour that goes without punishment… any and all of these things in children’s literature can be enough to stop the story finding a wide audience.

How to open a Korean fairy tale:

“Once, in the old days, when tigers smoked…”

But would a contemporary children’s book opening that way ever get published today?

I broadly agree with Philip Womack in his recent article defending the latest Julia Donaldson picture book, in which a scarecrow lights a cigar. I’m not among the picture book enthusiasts who believes that smoking should be banned in children’s literature, or that it would even make a difference. Womack summarises this week’s furore:

In Julia Donaldson’s new picture book, The Scarecrows’ Wedding, Reginald Rake, a scarecrow, lights a cigar, and is immediately admonished; he then manages to set on fire the female scarecrow that he’s courting. Cause and effect are clear: smoking harms you and those around you (although Rake gets off with only a cough). What could be more obvious, and less controversial?

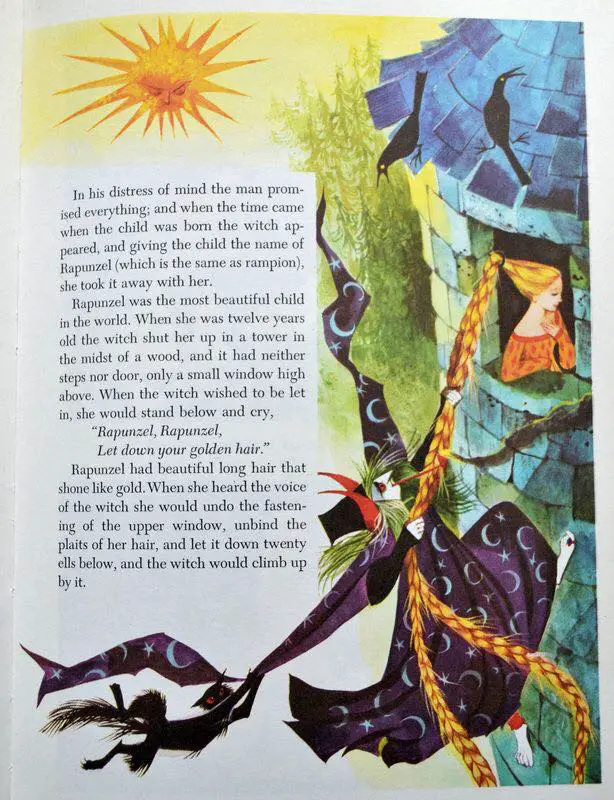

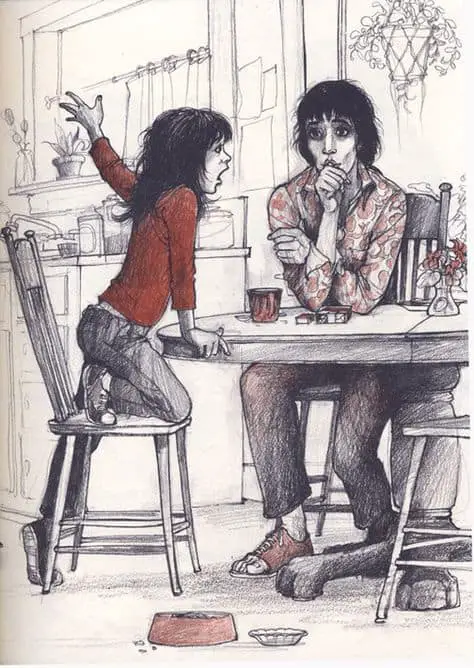

Sure enough, I’ve been considering the possibility of having a character smoke in the picture book app (for older readers) which we’re planning to release later this year. The art has already been done. One of the characters seems like the sort of person who you’d see with one of those lady cigarettes, the kind with the holder, like you’d see on a noir film of yesteryear. In completing the artwork I pussied out a bit, and instead I have a small stream of smoke coming out of an ashtray, which may or may not be noticed by a reader, and wouldn’t be interpreted as cigarette smoke by any young readers who are lucky enough to have been sheltered from the practice of smoking over the course of their entire life:

(At least I got the knitting needles right.) Here are the problems I see with Womack’s argument, however.

1. FANTASY OR REALISM: WHEN IT COMES TO CAUSE AND INFLUENCE, THE DISTINCTION IS IRRELEVANT

Womack writes:

This [furore] misunderstands something fundamental about picture books. They are, first and foremost, fantasies. I don’t see anyone complaining about the fact that the scarecrows can talk; nor that they are brought a necklace of shells by a handy crab when they are nowhere near the sea. A fantasy can be used to make a moral point, as Donaldson does, patently; and since children respond much more easily to ordered, made-up worlds than they do to the baffling real world, it is often the best way to get something across.

And so Womack contradicts himself. He seems to be saying that fantasies are disconnected from the real world of the child while at the same time admitting that fantasies are actually the best way to influence young children. I am very wary about using the ‘it’s only make-believe’ as an argument either for or against anything in the world of literature and other media. But here’s something I’m not seeing come out of this debate. In fact, it’s taken as a given, and is instead being used in the book’s defence:

2. SMOKING IS NOT ACTUALLY A SHORTCUT TO SIGNAL VILLAINY

My main issue with tobacco use in story is when the reader is encouraged to make some moral judgement about their (bad) character.

One of the most important things I hope to teach my daughter is that you can’t tell much about a person by looking at them. Goodies and baddies cannot be identified on the street simply by their clothing, physical appearance and accoutrements. If they could, the ‘Keeping Ourselves Safe’ unit they’re learning at school right now might take a different tone altogether. In fact, by conflating smoking with evil, we’re possibly creating two unintended lessons for young readers:

1. People who smoke are evil; ergo discrimination of people who are addicted to tobacco (often disenfranchised) are not deserving of help, or of Champax subsidies, come to think of it.

2. People who smoke cool because they have a touch of evil, or subversive, or against the grain; ergo, if you want to identify as alternative in your post-adolescent years, taking up smoking is one way to do it. More ominously, perhaps, children may absorb the message via common tropes that people with bad intentions can be identified by their appearance, in which case, real world people who look ‘normal’ may get away with things they should not. My decision to avoid the more overt smoking scene in Hilda Bewildered and instead have the character pick up a pair of knitting needles was actually down to my reluctance to promote tropes which, unexamined, may be doing more harm than good. If children’s book writers and illustrators are going to avoid depictions of tobacco use in their picture books, then I’d prefer it were for this reason.

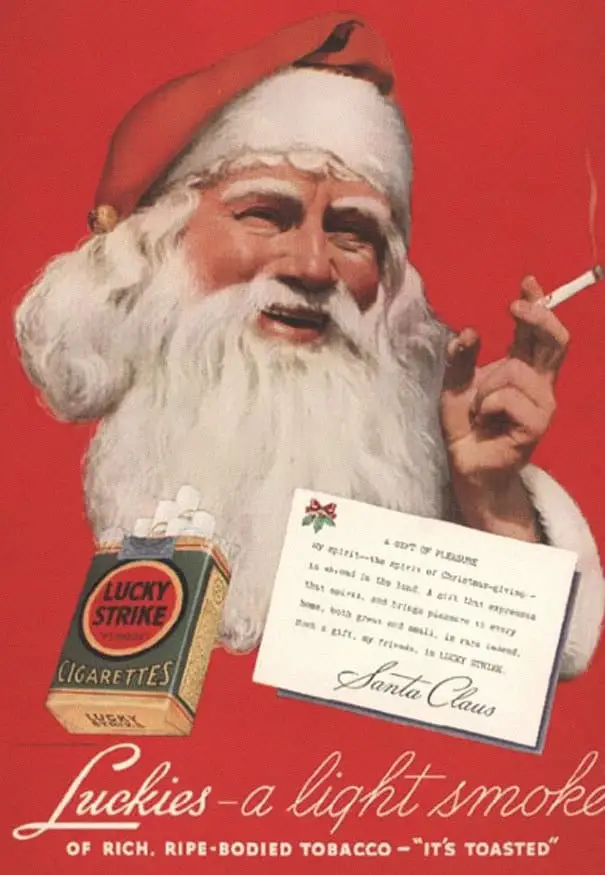

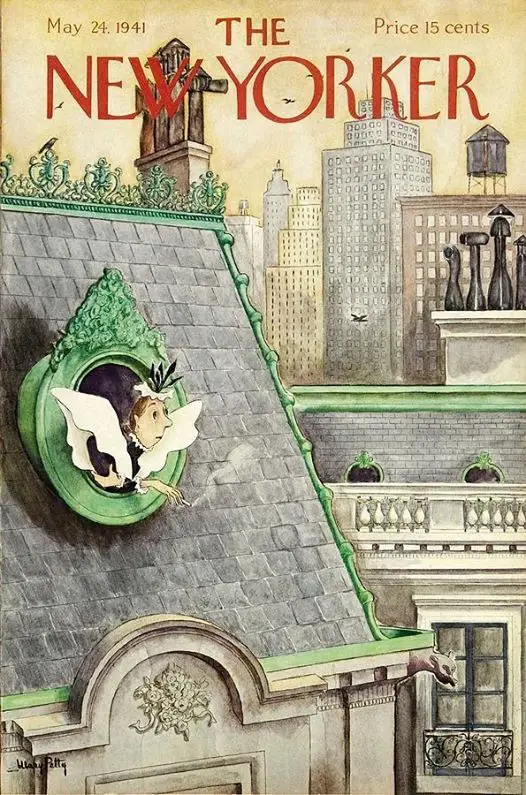

The advertisement below is not necessarily aimed at a young audience, but if it involves Santa, the illustration inevitably links smoking to childhood pleasure.

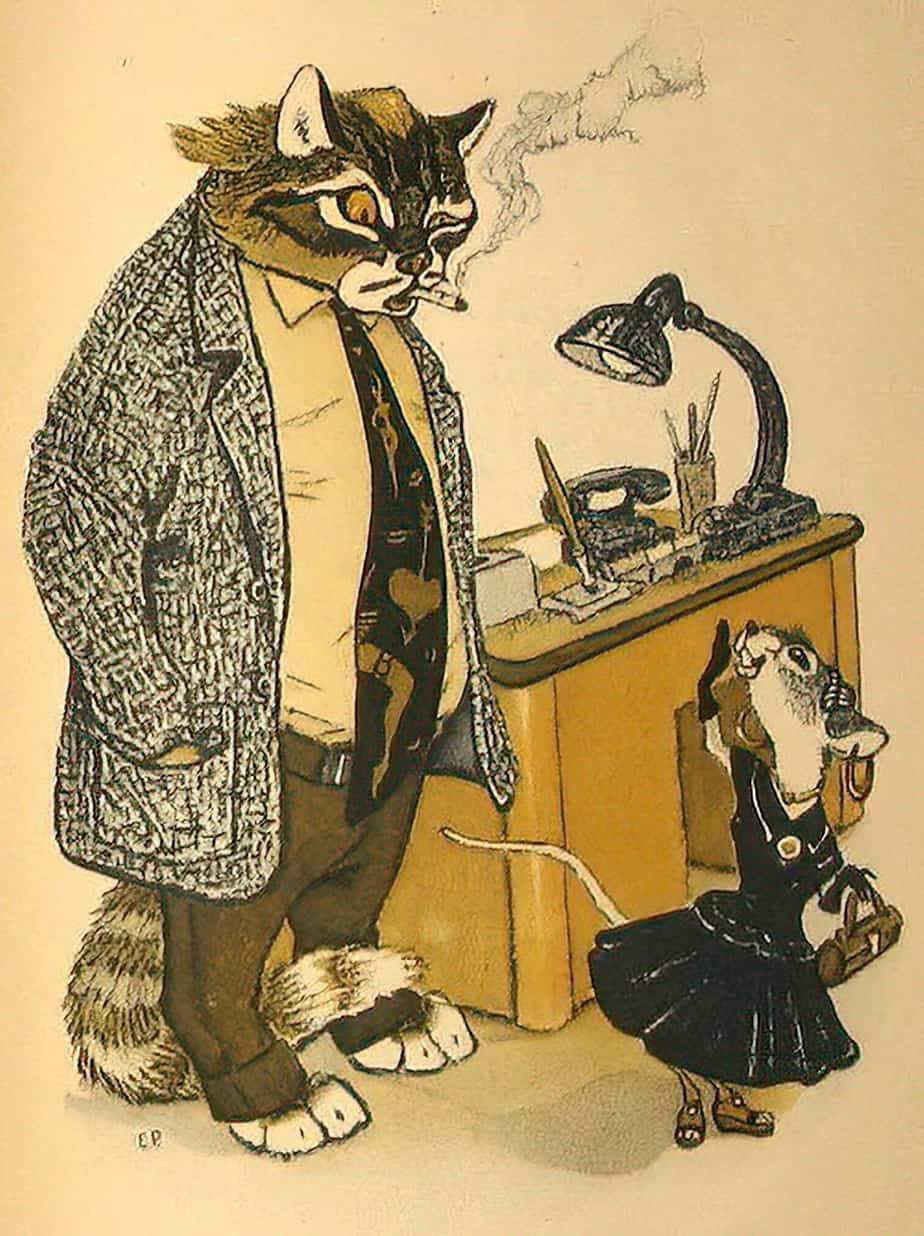

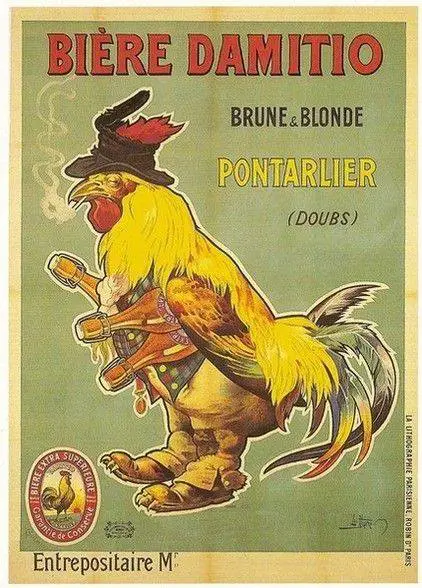

Even for adults, cigarette companies have traditionally linked their products to popular fictional characters in order to sell their product.

Moving on to the depiction of tobacco use in classic art, I was surprised to learn the extent to which smoking has gone in and out of fashion. I had imagined that once tobacco caught on, it remained fashionable on a continuously upward trajectory until its ill-effect on health could no longer be ignored. But this is not the case, as explained by Witold Rybczynski:

There is plenty of evidence that people’s sensitivity to smell was more highly developed in the Victorian period. They had a horror of cooking smells, for example, and so they located the kitchen as far as possible from the main parts of the house … The smell of tobacco was similarly affronting. During the first part of the eighteenth century, people stopped smoking almost entirely, and when, later, cigars started to come back into fashion, they were still forbidden indoors. Queen Victoria banned smoking in her homes, and many followed her example. In some country houses visitors who insisted on smoking were archly directed to the kitchen, and then only after the servants had left. …. When smoking became more common, a special room — the smoking room — was added to contain this activity.

Home, Witold Rybczynski

Will we ever see a comeback of tobacco smoking? What about vaping? Will that ever be depicted in stories for children?

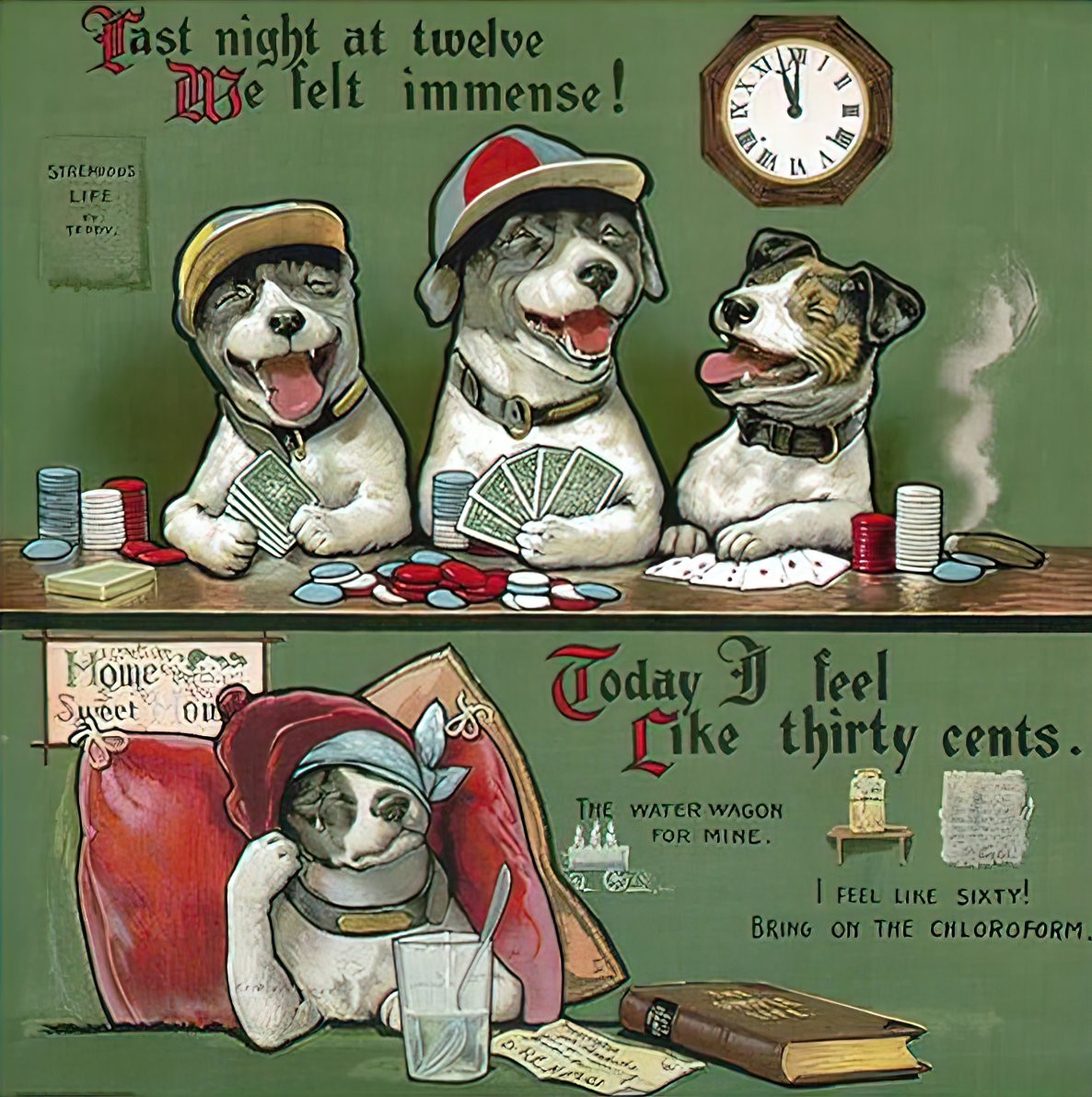

Header: ‘Katzenjammer’ 1905 advertisement for pillow cases by Harold Knerr