To The Manor Born is a British romantic comedy series written by Peter Spence which aired from 1979 to 1981. The actors reunited for a Christmas special in 2007. The writer is also known for Rosemary & Thyme and Not The Nine O’Clock News. Spence is educated in politics and American studies, which come across in his one-liners — these English characters have a contempt for all things American and there is a stark division between the blue bloods and the Labour government. He married into the family that runs this estate, so I can’t imagine anyone better positioned to write from an outsider’s perspective about a small English community set around a parish than Peter Spence.

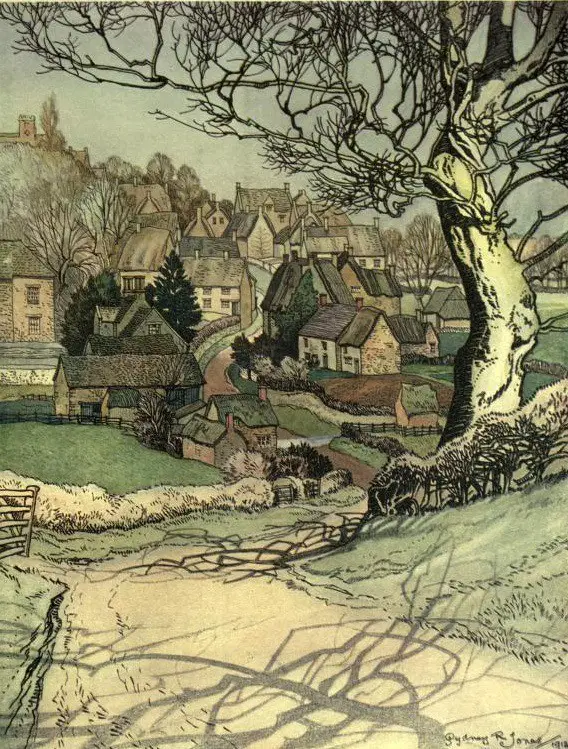

SETTING OF TO THE MANOR BORN

Characters Who Stand In For Subcultures

Oftentimes when two characters clash in fiction, those individuals stand in for the clash between groups of people irl. This elevates an otherwise simple comedy or domestic drama. In Hud we have a clash between old values and new (1960s) values of the American South. In 2017 we saw a similar clash in Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri, in which certain characters exemplified racist, insular attitudes. Others struggle to deal with the new, kinder culture. Still others display progressive values. In To The Manor Born we have a very British clash between aristocracy and the nouveau riche — two very different kinds of rich, but both rich all the same, and therefore foreign to the vast majority of the audience.

TO THE MANOR BORN STORY STRUCTURE

Structure Of A Transgression Comedy

Each episode of To The Manor Born conforms to the transgression comedy. This is a perfect structure for two characters whose modus operandi — and main character attribute — is to pretend they are something they are not.

Discontent: someone is unhappy about something

Transgression with a mask: peculiar to comedy (and, incidentally, to noir thrillers)

Transgression without a mask: midpoint disaster when the mask is ripped off

Dealing with consequences

Spiritual Crisis: happens in almost every story

Growth Without a Mask

The stand-out example of this comedy structure is Tootsie, but can be seen all over comedy, including many episodes of The I.T. Crowd.

SHORTCOMING

Returning to To The Manor Born after a long time (it was a series I grew up with), I was slightly surprised to see that Richard DeVere is set up as an equal insofar as screentime and empathy goes. My memory is that this is a story about Audrey. We actually meet Richard first, as he pulls into the village, setting him up as the viewpoint character. Like Richard, we are amused as outsiders by the eccentricities of the vicar. Richard comes across as very reasonable — we sympathise with him.

We soon see that Richard wants what he wants and stops at nothing to get it. He’ll even crash a funeral gathering to get his dream house. Richard reveals himself to be a trickster, though we don’t know the extent of this until episode two, when we learn that he is part Czechoslovakian, part Polish. (This is the perfect example of transgression comedy in which ‘the mask’ comes off. Richard DeVere is revealed to have a Czech birth name. )

Richard’s shortcoming is that he uses people to advance himself socially, and this makes him blind to whatever else is going on peripherally. He demands to be treated with respect, and in the business world he no doubt gets it, but here in blue blood territory he is starting from the bottom and must earn respect in a foreign environment.

Audrey fforbes-Hamilton is presented immediately as a trickster. The trickster is a very popular archetype with audiences, and we needn’t sympathise with them at all because they are so interesting. Tricksters make plans and follow them through. All we need in order to sympathise with a character is right there. We don’t even have to agree with their morality, and we wouldn’t agree with Audrey’s if we knew her in person — Audrey is a pragmatic, gold-digging schemer who will happily use people to get what she wants.

Audrey is also part of a long British tradition of comedic, socially aspiring women, which were very popular sit-com fodder in the 1970s and 80s, and which may be making a comeback.

These women care about no one but themselves and Audrey is probably on the sociopathic spectrum, treating all people as tools, failing to even recognise the emotion of sadness after her blue blood husband dies of double pneumonia and good living. An older, American analogue would be Scarlett O’Hara in Gone With The Wind, in that Peter Spencer uses the same trick — he surrounds Audrey with people who do like her. This tells the audience that bad characters can’t be all bad.

Audrey and Marjory are among the second-to-last generation of toff women who were never expected to work, trained only in social manners and managing domestic staff. The very last of that class included women such as Princess Diana, born 1961. Audrey and Marjory would have been born around 1940, same as Penelope Keith. Audrey’s other shortcoming is that she’s just not fit for integration into regular life, even though that is exactly what is demanded of her now that England changed markedly after the war. Audrey has no marketable skills. Unless she marries rich again there is no place for someone like Audrey, and this is a very real problem for her. We could dig more deeply and it says something serious about upper-class women, and how a sexist dichotomy imprisoned them, in its own way.

DESIRE

Richard wants the dream house to impress his business pals, and also to pass himself off as old money. Audrey and Marjory’s xenophobia shows us that Richard has been up against racism his entire life, and we can see why he might want to offload his continental heritage to make life easier for himself.

Audrey wants to continue living in Grantleigh Manor, which has been in the family (her former husband’s family?) for 400 years. I doubt this heritage factor is important to her in the least — Richard pulls her up when she claims certain traditions are ancient when they’re really only new. Audrey wants to stay in the house to maintain her prestige in her community. It is a huge comedown for an aristocratic woman to be ousted from the family manor.

In episode one we are shown Audrey’s history — she had an ‘arranged’ first marriage (arranged by herself), and we’ve not surprised to learn in episode two that she has designs on Richard DeVere, not for him but for the manor. It’s also no surprise because it’s right there in the title. The title is so good because there is irony in it. Audrey is no more deserving of that manor than anyone else. I feel like this show gave modern culture the phrase ‘to the manor born’ but it goes back much further — To The Manner Born is a play on the phrase “to the manner born,” from Shakespeare’s Hamlet.

The desire-line ‘to marry Richard and move back into Grantleigh Manor’ will sustain the entire series. And because this is a romantic comedy we know the two will get together eventually.

What keeps them apart over the course of three seasons are mini-desires that are either fulfilled or stymied in the course of one half-hour episode.

01: Richard wants to buy Grantleigh whereas Audrey wants to continue living there as a happy widow. (The sustaining desire-line is established.)

02: Richard wants to find a social secretary to help him integrate into the village without impacting on his role as CEO of his supermarket chain. Audrey is not at all happy about being ousted into the much smaller property across the meadow, but wants to reclaim some dignity of sorts by tricking Richard into embarrassing himself by thinking someone else has moved in instead — someone he can use. In this episode Audrey gets what she wants in a small way, while Richard has already got what he wants in a big way — the manor.

03: Audrey wants to turn Richard into a church-going man. This is one concrete improvement she can make to a man she wants to turn into marriageable material. (Marriageable in her own eyes, that is.) Peter Spence is sure we know that this is part of a larger scheme by having Audrey tell Marjery so.

04: Audrey continues on her Richard improvement strategy. He must learn to protect the nation’s heritage. Instead, he has replaced an ugly but culturally significant mantel with a safe full of cash. Audrey wants him to feel bad about this. (It backfires when she ends up with the ugly mantel in her lodge.)

05: Audrey wants Richard to come to her on “bended knee” to ask for help in organising an annual ball. She wants to maintain her former status in the community and also impress Richard with her organising skills.

06: In episode six, Mrs Poo is the character whose desire sets the story going — she is bored at the Manor and wants a party. But because Mrs Poo is a minor character, her desire is also minor, and can be considered a McGuffin desire. It is only once Audrey attends the party that her own story-worthy desire kicks in — she wants to show the village that she is doing well financially. For that she must go on her usual overseas holiday. But as she explains to Brabinger, it’s appearing to go on holidays that is the main thing, not going on the holiday itself. It makes sense for Audrey’s character that she doesn’t enjoy overseas holidays in the slightest. This is shown via her reading a holiday journal from the previous year, in which she was bored. Outside her own very specific environment, the xenophobic Audrey flounders. This harks back to the wider, enduring desireline of Audrey — regain her former position or die. Audrey is the human equivalent of an insect which can only survive on one single blighted species of grain.

07: At the beginning of the episode it is revealed that Audrey has been having cash flow problems. Ordinarily, a real life person would ‘want money’, but because this is a comedy and because Audrey is a comic archetype, Audrey doesn’t really want money. (For her, such a desire is crass.) She is ironically upbeat about the late bills and wants to bounce a cheque at one of Richard’s supermarkets to get her own back. He took her house, after all. Then she wants to know what’s going on at the Manor, because Richard has a clearer desire in this episode — in an attempt to appear more English he is staring in an advert for Fontleroy’s Old English Tonic. When this is revealed to Audrey she has an about turn and her desire changes — she wants to star in the advert herself, considering herself more genuinely suitable for the job.

OPPONENT

Romances are so difficult to write because the main opponents are the lovers, to each other. This series follows the fight-fight-kiss-kiss tradition of romance, where the audience sees from the very beginning that two characters are perfect for each other, and now we must (hopefully) enjoy watching them come to the same realisation, swapping witty banter (and it had better be witty).

A mistake some romance writers make when writing these fight-fight-kiss-kiss stories is simply creating personalities that clash. That’s not enough. Their agendas need to clash. Agenda = desire + plan, so their desires and their plans must clash as well.

The manor provides a very solid goal (desire) for both of them, but they can’t both have it.

Audrey and Marjory have a longterm, sisterly relationship in which Marjory is often the voice of reason, speaking for an audience who would otherwise question Audrey’s motives. A staple of British comedy is the stupid sidekick. In The Vicar of Dibley we have Alice, in Only Fool’s and Horses we have Rodney Trotter, and so on. This dynamic is also utilised frequently in cop and buddy comedies, where one guy is wily and the other dimwitted, getting them into trouble.

PLAN

What is Audrey’s overall plan? After the wedding she plans to stay in the Manor, living life as before, only without her husband. This plan is soon dashed when she is told she is in debt. She has a plan to raise funds, but has no idea about how hard money is to come by, so these plans fail and she is required to leave her family manor.

Her plan switches and she intends to win over Richard. She’s planned this before the other characters realise — she has purchased the lodge, very nearby. Audrey understands Richard completely and knows that in order to win his heart she has to prove herself as wily and socially aspirational as he is himself. All of these trickster stories are flirtation. And the audience loves to see them fall. These are powerful people we’re laughing at, which makes it satire.

BIG STRUGGLE

The big struggle scene in each episode of To The Manor Born involves witty back-and-forth dialogue between Richard and Audrey, often with an audience such as Marjory, sometimes alone. Spence started out as a gag writer for radio, but as he explains in the special features, Penelope Keith told him she’s not a gag actor. Also, gags would not be in keeping for a lady of the manor, so that explains why the big struggles happen in dialogue.

The writer kept the winning and losing about even, to show the audience that these two characters are made for each other. Audrey succeeds in getting Richard to church, but in the next episode she succeeds in conveying the importance of historical buildings but fails at the same time — she didn’t want the old mantel in her house. In “The Grapevine” episode, both Audrey and Richard are victims, discovered by the whole village coming out of the woods at night. They’ve been observing badgers.

In “A Touch Of Class”, Audrey attempts to trick Richard into eating a terrible mean, but she has been outfoxed by her drunkard temporary butler, who serves up a delicious meal, cooked by a renowned good cook as a favour.

ANAGNORISIS

A look at the structure of a transgression comedy (above) maps the ‘anagnorisis’ phase onto the ‘coming off of the mask’.

Over the course of the first series of To The Manor Born we see Richard realise that he has to learn a new culture and make a big effort to fit in, as custodian of the land he now owns. The whole village now knows that he’s not old money, so he’ll have to try extra hard to fit in. He realises in episode two that when you’re living among blue bloods, they’re not always happy to do what you want them to do, e.g. be your social secretary.

As for Audrey, she starts off resenting Richard, then realises she might be able to marry him and return to her manor, then she realises she’ll have to mould him into the sort of man she would want. Finally by the end of season one it is clear both of these characters are more similar than they are different, and Audrey realises she likes him as a person.

NEW SITUATION

The back-and-forth one-upmanship and the discovery that each of them is duplicitous as the other will culminate at the end of season three in a wedding. The wedding episode drew huge viewer numbers in 1981. It was the only episode not written by Spence, for some reason. Perhaps Spence felt more comfortable writing transgression comedy than in tidying up a romance with a happy ending. These are two different skills, and two different sensibilities.