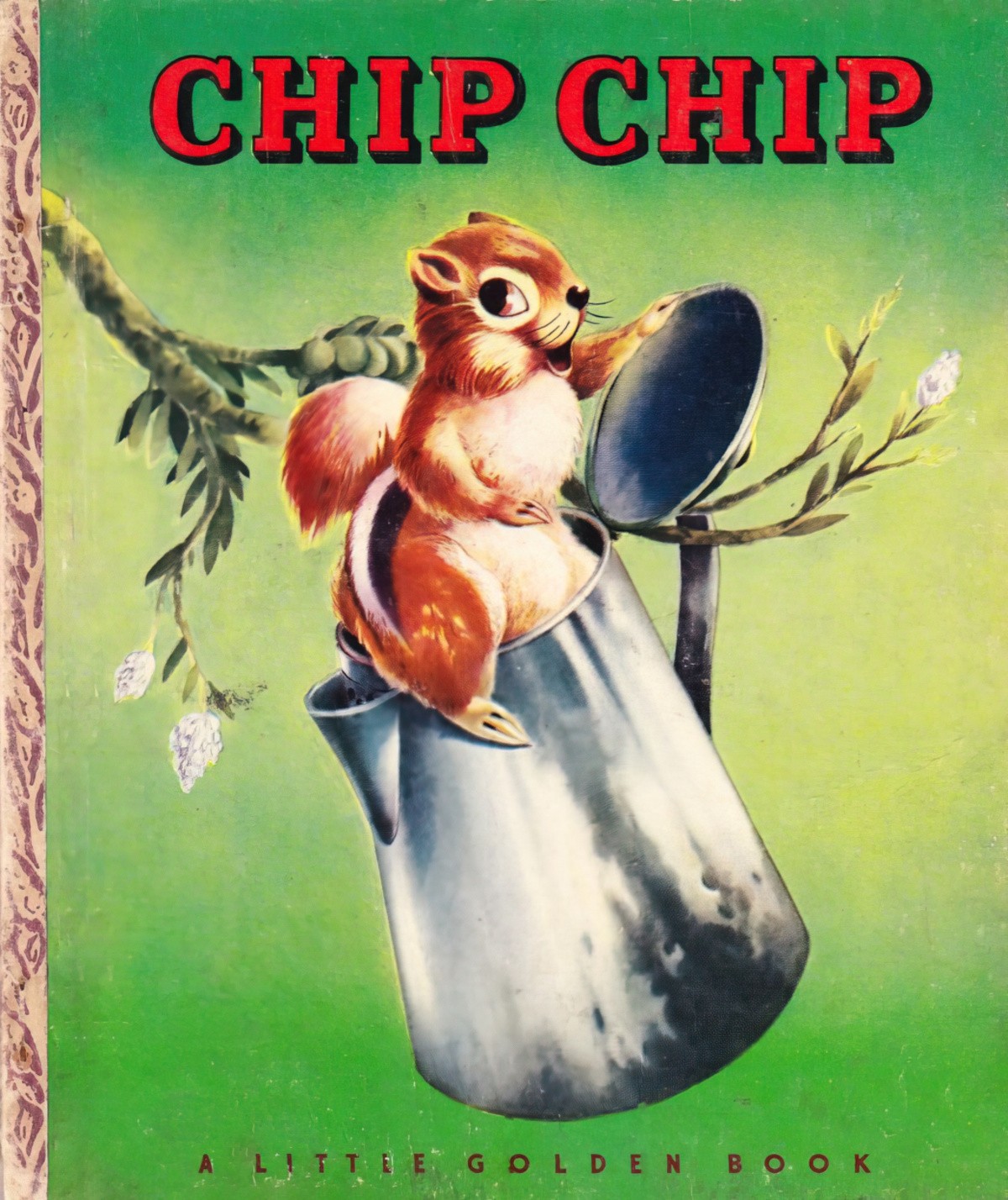

Beatrix Potter was already popular by the time she published The Tale of Timmy Tiptoes (1911). The introduction to our 110th anniversary copy says the tale was created specifically to appeal to a new, American audience, with the inclusion of chipmunks.

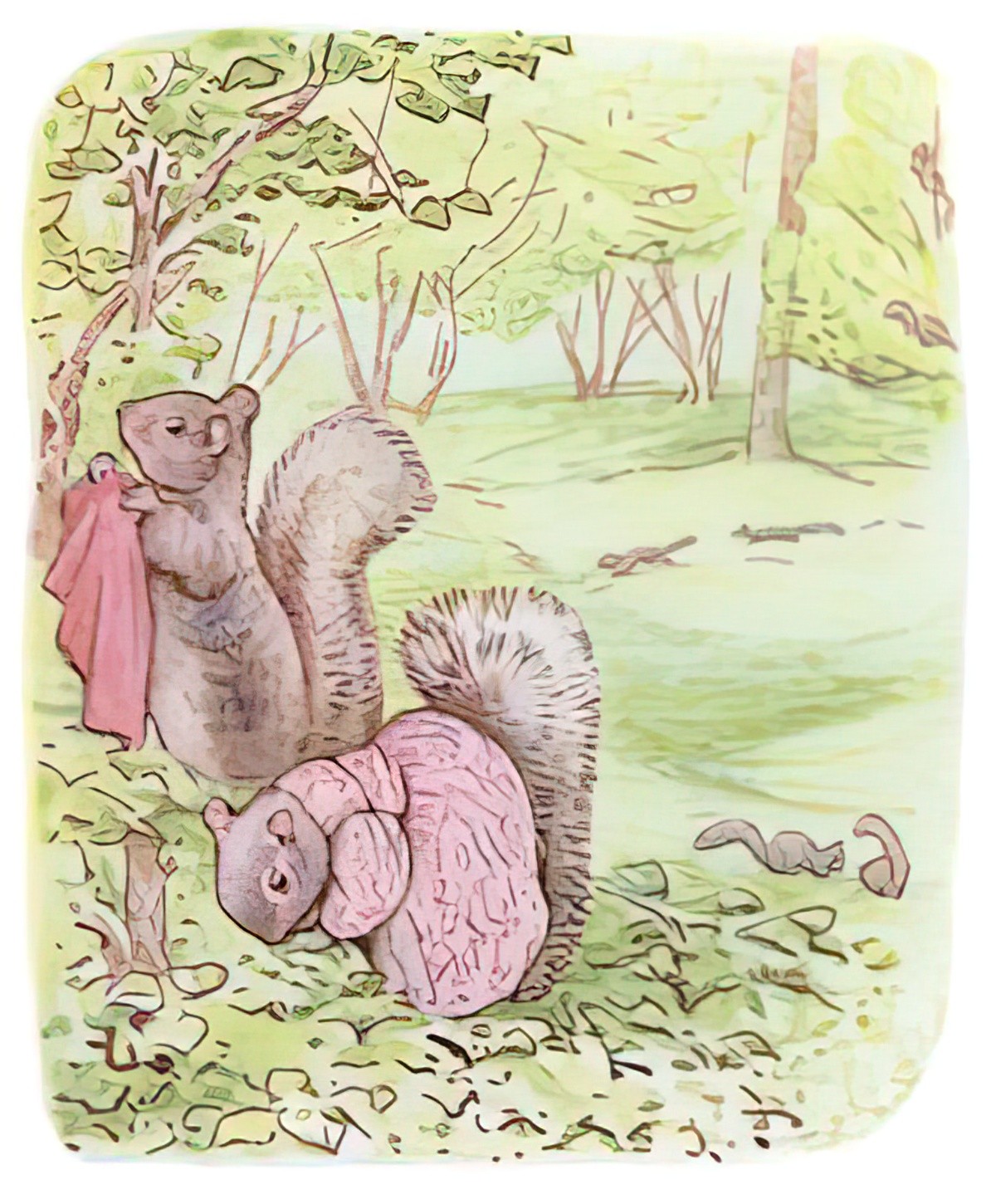

Unfortunately, Beatrix had never seen a chipmunk in real life. She must have relied upon photos when illustrating the chipmunks, but good reference photos wouldn’t have been easy to come by in England at the time.

The publisher pointed out that Potter’s chipmunks looked more like rabbits. She initially insisted chipmunks DO look like rabbits, but was required to re-do them regardless.

Whatever you think of Beatrix Potter’s chipmunk’s they’re nowhere near as bad as this… 1895 “platypus”, also clearly never seen by the illustrator:

This story is notable for its depiction of bird calls set to words. Like the riddles found in other Beatrix Potter books, and like nursery rhymes in general, my generation of parents may be skipping the teaching of these bird calls set to words. e.g. “A little bit of bread and no cheese” to describe the call of a yellowhammer, introduced to New Zealand by Acclimatisation Societies between 1865 and 1879. My own father taught this to me, but I remain unfamiliar with the calls of European birds.

The calls in Aristophanes’ Birds (produced in 414 bce) must be some of the oldest examples of this on record: Torotorotorotix, Epopoi popopopopopopoi and so on.

Aaaaw to Zzzzzd: The Words of Birds North America, Britain, and Northern Europe is a book by John Bevis. Its marketing copy reads: The distinctive and amazing songs and calls of birds: a meditation and a lexicon.

We do have a few New Zealand-specific bird calls set to words, most notably from Denis Glover’s famous poem “The Magpies”, which I learned in school. My parents’ generation were required to memorise poetry and this was one that New Zealanders over about 75 will be able to recite for you, but the skill of poetry recital had died by the time I went through primary school in the eighties. I didn’t memorise a single poem (outside Bible verses).

New Zealand’s magpies are from Australia. Now I live in Australia, surrounded by an array of outstandingly noisy birds. The magpie barely makes an impact against the cockatoos, so it’s no surprise the poem was written in New Zealand, where the magpie remains distinctively loud.

When it comes to birds, regional dialects develop. Haha. So yellowhammers probably sing with a Kiwi accent these days.

VIOLENCE in timmy tiptoes

The Tale of Timmy Tiptoes is a remarkably violent story of the kind you won’t see published anew today. The scene where Timmy is wrangled through a very small hole leaves him close to dead. This is Tony Soprano stuff.

A MODERN THEORY

But it’s also a tender story of two male characters spending time together, one looking after another in a way far more typical of feminine caring. I just did an Internet search in case my thoughts on this are already done to death in literary circles, but found nothing. I may plough a lonely furrow, and this may sound facetious, but through my contemporary lens Chippy Hackee reads as a gay man, perhaps gender queer, or some related combo.

STORY STRUCTURE OF TIMMY TIPTOES

This story is written in classic mythic structure. Timmy leaves home, encounters baddies and goodies, must decipher which is which and eventually returns home slightly changed. Beatrix Potter mixes things up a bit by switching the squirrel main character out for a chipmunk, who continues this same linear journey into darkness. It is the chipmunk who faces the biggest big struggle (with the bear). Potter’s empathetic character remains safe.

SHORTCOMING

Timmy Tiptoes starts out with a remarkably hygge vibe — life is good for this young married couple, living in a utopian woodland with plenty of food and meditative days out collecting food for winter.

DESIRE

Timmy Tiptoes and his wife want to collect enough nuts for winter.

Chippy wants a different lover from the one he’s got, or maybe he only wants the freedom to express the feminine-coded act of caregiving in an era where that’s not permitted for men. But that’s just my reading. (It would not have been Potter’s intention.)

OPPONENT

Something must happen to upset Timmy’s idyllic life. Turns out this is no utopia at all — only an snail under the leaf setting. There are baddies in these woods. Thieves.

If you are a hibernating creature and your food store gets stolen, that’s a life and death matter.

The birds are unwitting opponents by outing where the Tiptoe couple are hiding their stash.

Squirrels go to great lengths to hide their nuts — they meticulously arrange leaves to make them look undisturbed. (I think Potter would’ve seen that herself.)

Chippy is also an opponent to Timmy despite his caregiving — Timmy just wants to go home to his wife, but Chippy keeps offering up all this delicious food. He becomes too fat to fit back through the hole.

PLAN

Our main character has no plan other than to get on with his happy, day-to-day life, so in this case the baddies are the ones with the plan — they steal the Tiptoes’ nuts.

Silvertail is a forgetful squirrel, so his plan is to just dig up whosever nuts he finds. Potter was right about squirrels forgetting the location of some of their nut stores, but their memory is far more amazing than even naturalists knew back then:

Depending on the squirrel species and the type of nut, squirrels are generally able to retrieve up to 95 percent of their buried food, research shows.

Live Science

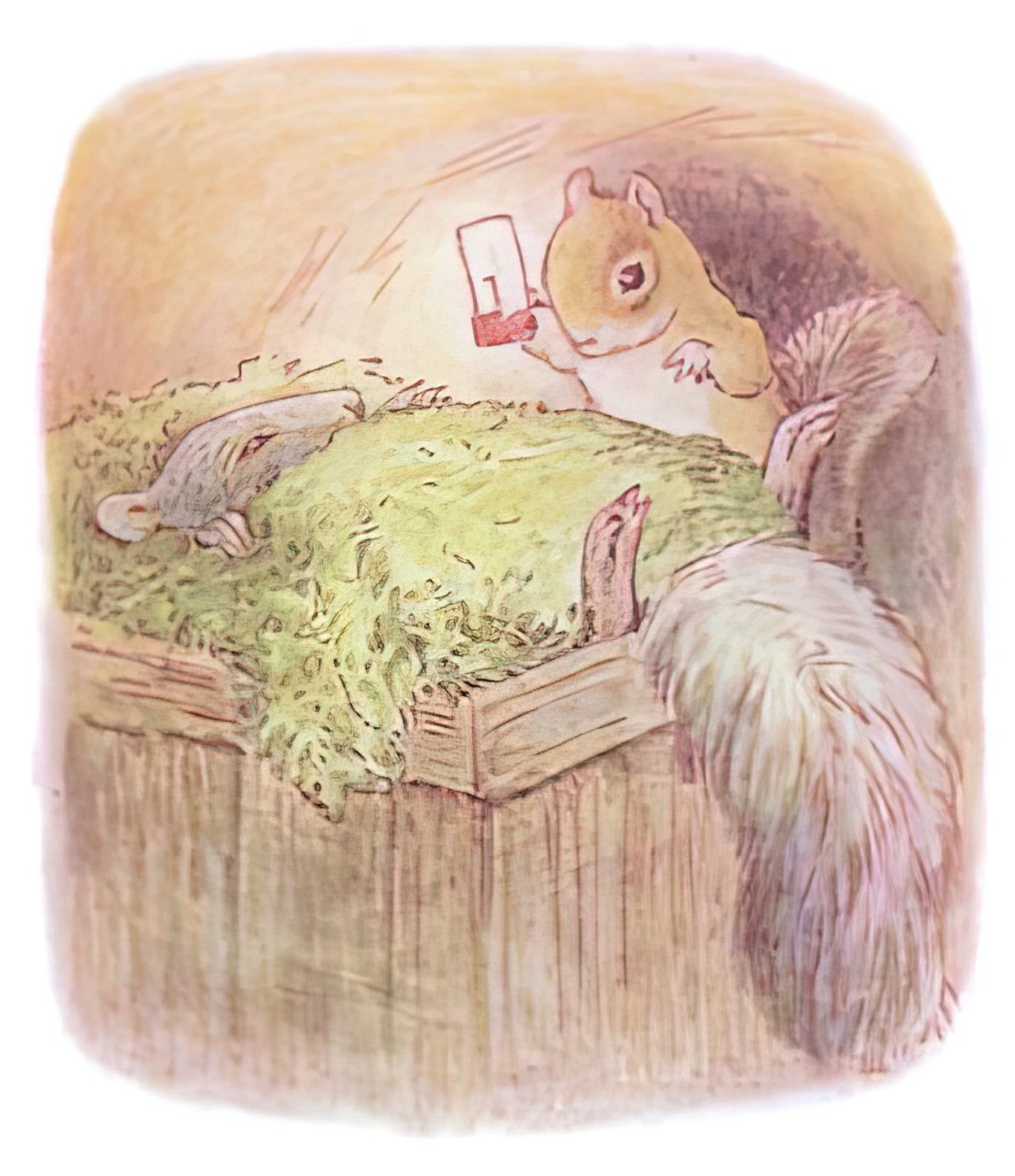

BIG STRUGGLE

Timmy has his near-death moment when he is squeezed through the hole in the tree. He lies semi-conscious upon his own store of nuts. Meanwhile we are subjected to the heartbreaking scene of Goody, his wife, searching everywhere for him. This Battle happens at about the midway point in the story. But Timmy is saved by the tender care of an (at first) non-gendered, unidentified chipmunk (referred to as the distancing ‘it’), who tucks Timmy into his own bed and even lends Timmy his night cap. Then he keeps Timmy captive by feeding him nuts so he will never make it back out through the woodpecker’s hole. This is Emma Donahue’s Room mashed up with Se7en mashed up with Brokeback Mountain.

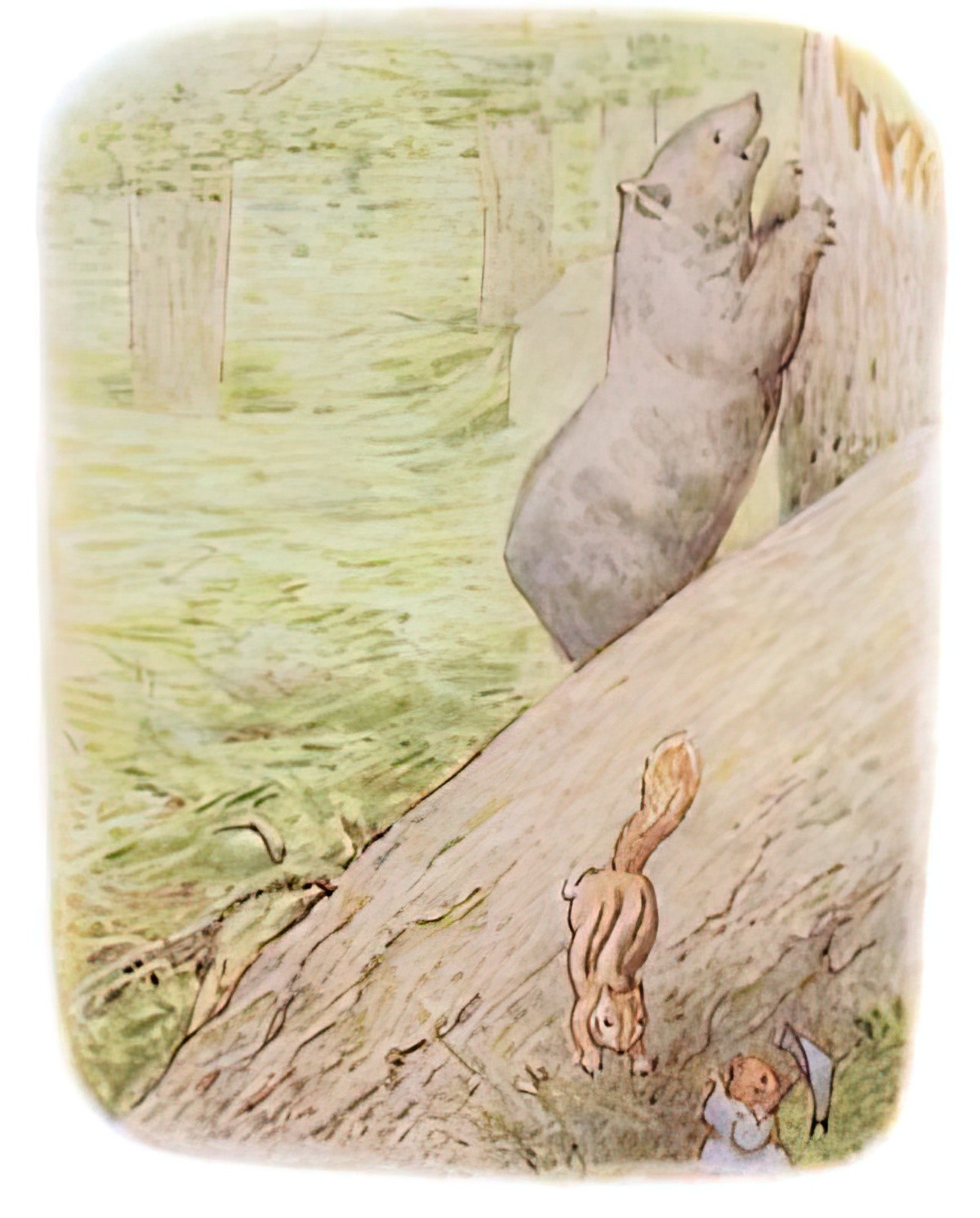

Conveniently for the story, wind blows Chippy’s tree over. This allows Timmy to escape and the mythic journey now switches to the chipmunk, whose name we learn is Chippy Hackee, but only after the wives get together to lament their missing husbands.

Mrs Chippy Hackee has been abandoned for reasons that remain unexplained within the world of the story. Nor are we given any clues — she seems a perfectly adequate wife — everything one would want in a chipmunk. I deduce the setting reason for Chippy leaving his wife must be this: Timmy has been busy filling their marital home with his nut store and Chippy is dissatisfied because his wife fails to keep their house clean — the main job of a wife in 1911, and perfectly obvious to Potter’s contemporary audience. An obvious plot hole: Chippy’s new hiding place is no less full up with nuts. The nuts are not the problem in that relationship, people.

We learn via Mrs Chippy Hackee that her husband ‘bites’; i.e. he bites her. She assumes he bites everyone. But we have seen the opposite behaviour from Chippy in his tender loving care for the larger, injured (male) squirrel.

Chippy refuses to go home to his wife even when the tree blows over, leaving him exposed to the elements. He would rather CAMP OUT IN THE ACTUAL RAIN than go home to his wife, who pleads with him nonetheless. He’s in a total slump. He had a soul mate in Timmy — now Timmy has gone home, arm in arm with his own wife, and if Chippy can’t have Timmy he would rather have no one.

The only thing that shoos Chippy home is the appearance of a hangry bear.

ANAGNORISIS

And when Chippy Hackee got home, he found he had caught a cold in his head; and he was more uncomfortable still.

More uncomfortable because of the head cold? His wife is nursing him back to health despite his previously biting her. Perhaps Chippy is more comfortable in the caregiver’s role. He’s had a taste of his gender expansive freedom and now he’s stuck being someone’s reluctant husband forever in the strict gender binary of 1911.

I don’t believe for one second that this was Beatrix Potter’s intent for the story. So what is the 1911 Anagnorisis of her Timmy Tiptoes tale?

That home with your wife is better, because wives take care of you. Go home to your family. Be loyal to your heteronormative family.

As for the Tiptoes, they buy a lock for their nut stash. Moral: If you don’t want your stuff nicked, lock it up. Hey, that’s what Chippy thought. (‘Lock up what you love’ doesn’t apply to living creatures, Chippy. You can’t just force feed a lover so he can’t escape through the hole, Chippy.)

NEW SITUATION

The Tiptoes have new babies, which makes Goody’s earlier scene all the more upsetting — she was pregnant with at least three when she thought she’d been abandoned by her husband.

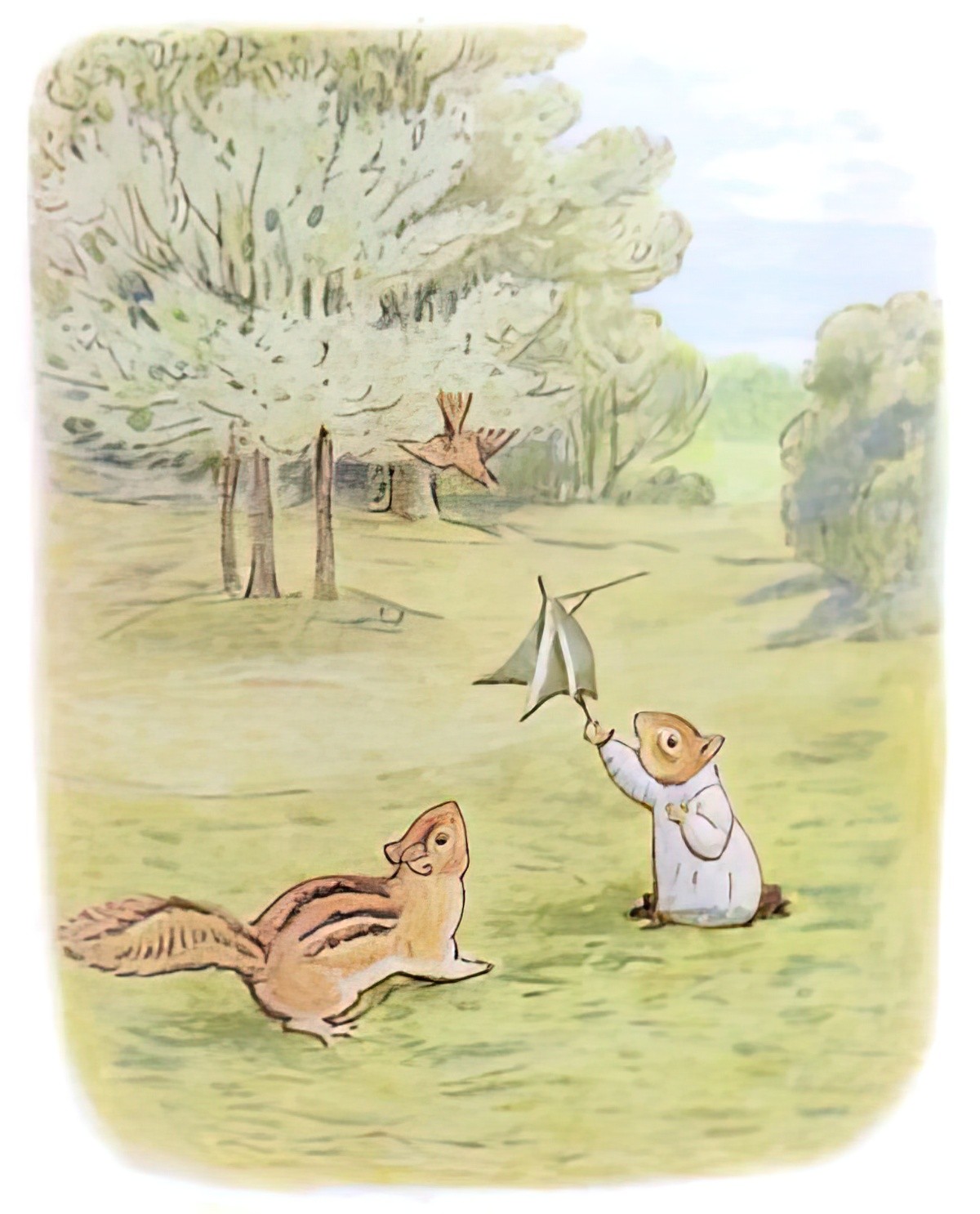

The final illustration suggests the chipmunks remain unhappy. Their discord is symbolised by the bird who swoops down, poked at angrily by the wife with that battered and broken umbrella, to symbolise the battered and broken relationship.