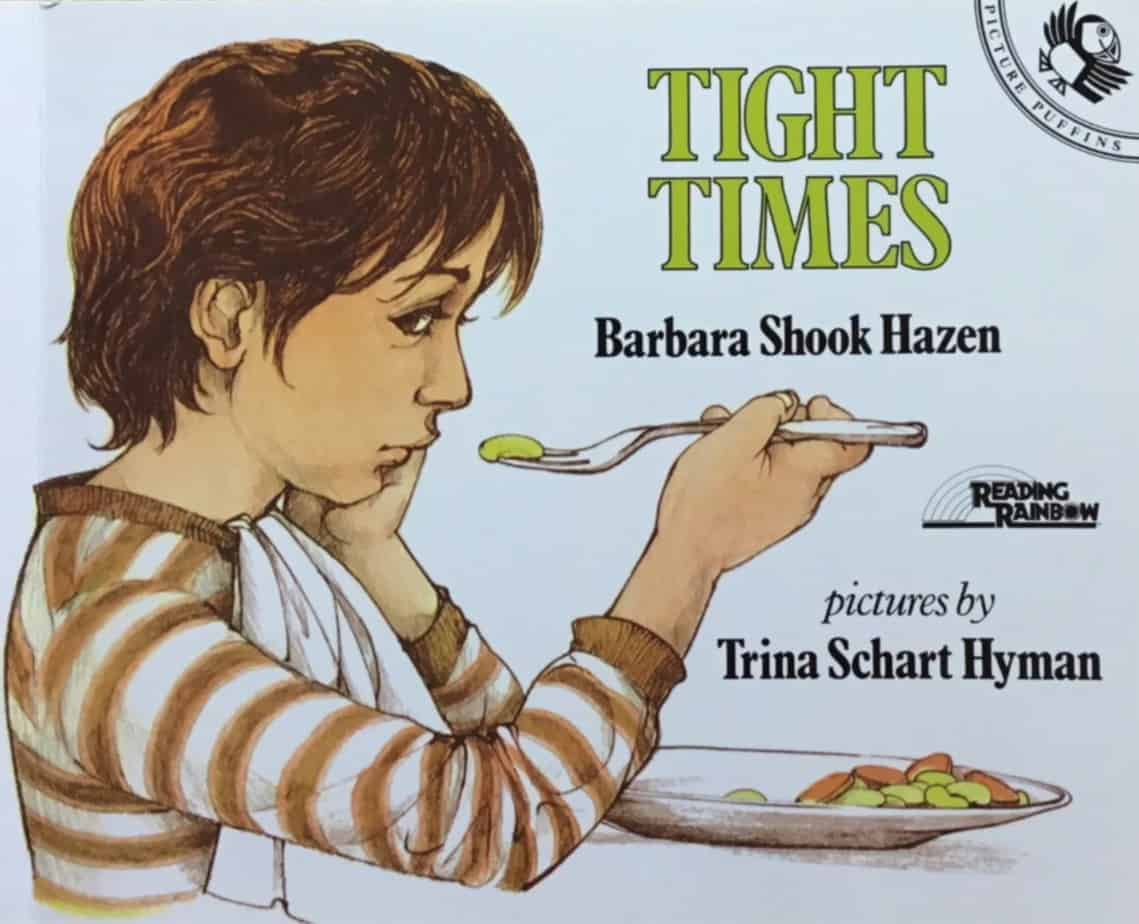

Tight Times (1979) is an American picture book written by Barbara Shook Hazen and illustrated in graphite pencil by Trina Schart Hyman. Tight Times also happens to be the first ever picture book read by LeVar Burton on America’s Reading Rainbow series back in 1983.

I can see why they chose it. This short picture book elicits some strong emotions, and unfortunately, this story about economic deprivation is just as necessary today as it was at the turn of the 1980s. Today in America, one in six children are living in poverty.

From a storytelling point of view, this picture book is interesting because it does a fantasic job of helping the reader empathise with the boy and his parents. Below I go into how write and illustrator work together to achieve that.

Also, as the child character heads towards the story’s climax, the storytellers make use of plot points straight out of fairytale, even though this is a story baked in realism. These plot points are so old and so embedded in our collective wisdom that other storytellers can make use of them to create a vivid and affecting story, full of pathos like this one.

SETTING OF TIGHT TIMES

- PERIOD — Late 70s, early 80s.

- DURATION — Like many picture books that take place over a day or so, there’s a build-up in which the reader gets a wider view of the child’s life. In the first part of Tight Times, the storytellers give us insight into what it’s like to live with less money than before. This maybe takes place over a few weeks, or a few months.

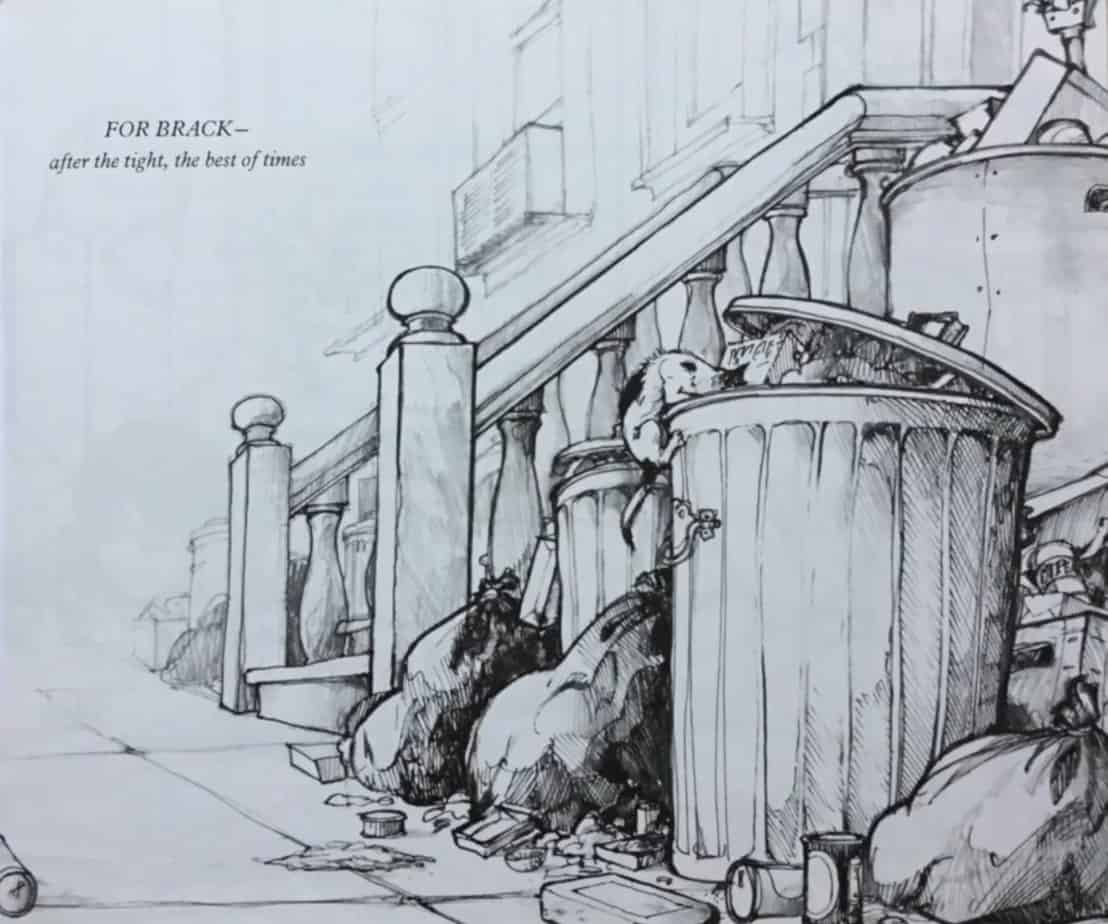

- LOCATION — New York? The houses open out onto the street where residents keep trash cans, which I recognise from images of New York but maybe there are other American cities with similar streets. When the bohemian woman turns up she’s holding a shopping bag with Zabars on it. I’m sure this offers Americans a strong clue.

- ARENA — The child is mostly in the home but also at the bus stop, at the shops and on his front steps.

- MANMADE SPACES — The city

- NATURAL SETTINGS — None

- WEATHER — Not relevant

- TECHNOLOGY CRUCIAL TO THIS PARTICULAR STORY — Not applicable

- LEVEL OF CONFLICT — I hope one day young readers will look back on these old picture books and think, Wow, imagine what it must have been like to live in a world where you can lose your job and have hardly any money to live on! I hope the 2020 pandemic takes us in the direction of universal basic income, not in the conservative, fascist direction. This boy is in a relatively stable position compared to many kids. He and his parents are white, and his parents are together. Children of colour from single parent families are more vulnerable, and almost entirely absent from American children’s stories in the early 1980s.

- THE EMOTIONAL LANDSCAPE — For light comedy purposes, as well as for realism, the child character doesn’t understand how naive he is about the outside world. Like Maisie in What Maisie Knew by Henry James, his lack of knowledge scares him and protects him at once.

STORY STRUCTURE OF TIGHT TIMES

PARATEXT

The marketing copy gives away the plot rather than tantalising the reader:

A small boy, not allowed to have a dog because times are tight, finds a starving kitten in a trash can on the same day his father loses his job.

MARKETING COPY

SHORTCOMING

As applies to every child character in every picture book everywhere, the first person narrator’s main shortcoming is naivety. His naivety shines through in the voice, but the author cleverly shows us his naivety on the page. (This always appeals to the adult co-reader even if the child misses it.)

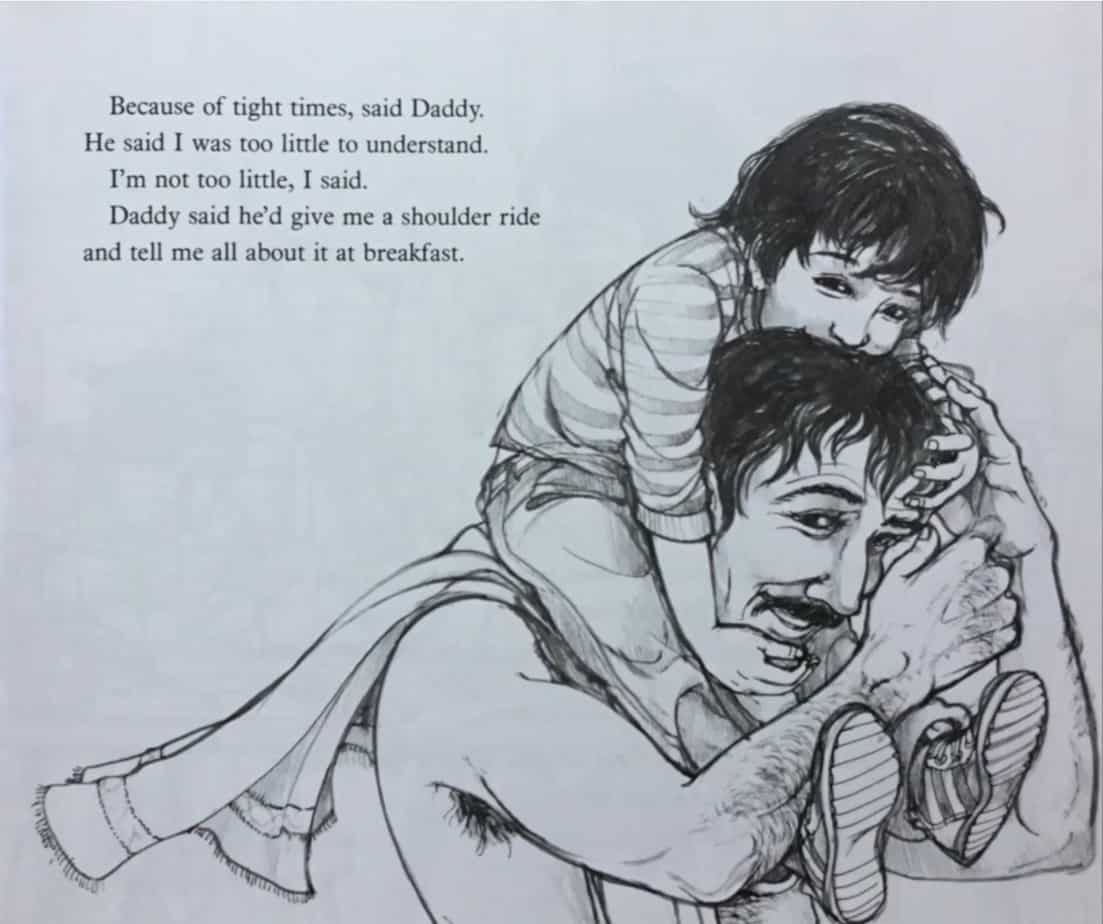

On this page, the father tells his son that he is too little to understand. The boy disagrees.

Turn the page and the reader is treated to a wonderful example of the exact naivety the boy insists he doesn’t have.

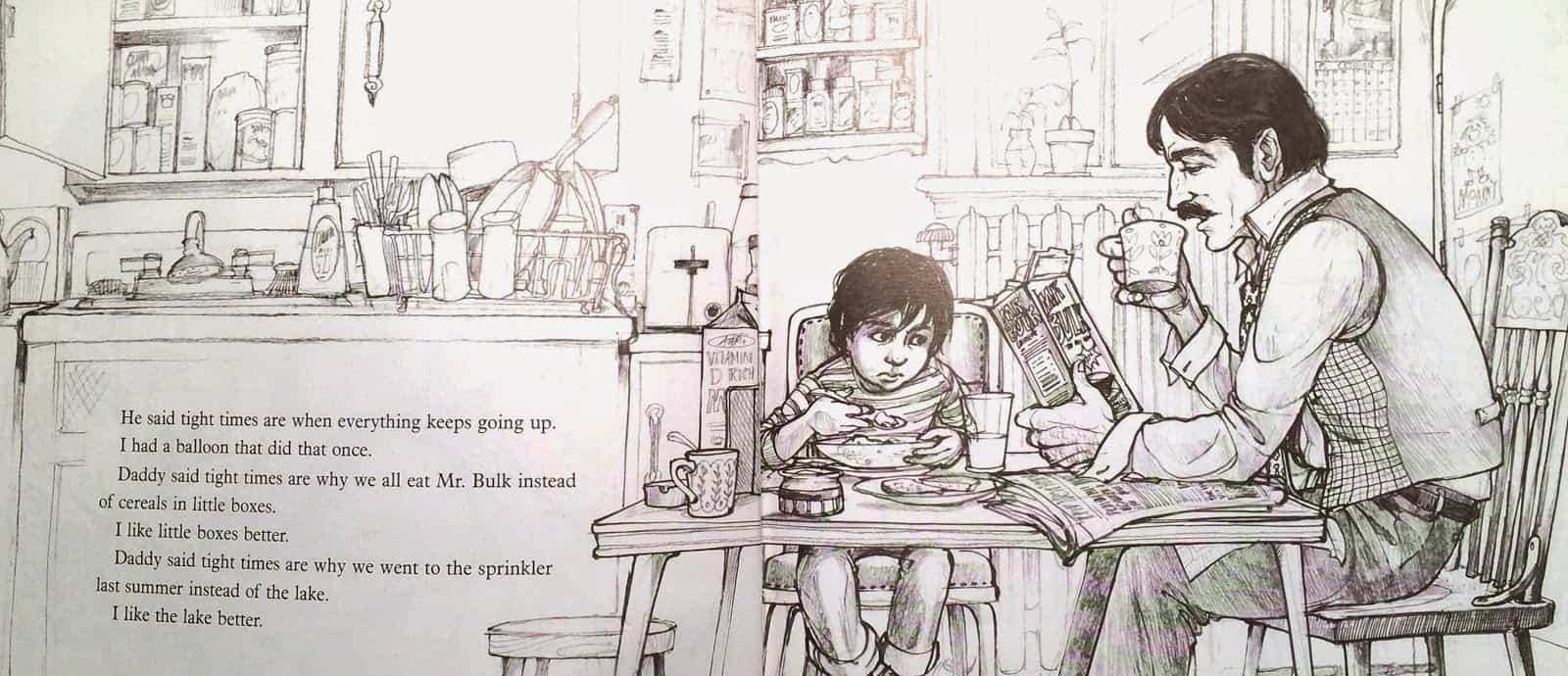

“Things keep going up,” says the father, clearly meaning prices. The boy thinks of a balloon — a literal example of something going up. Later he will encourage his father to look for his lost thing (his job) behind the radiator, because that’s where he lost a puzzle piece once. The boy’s universe extends only as far as the edges of the house.

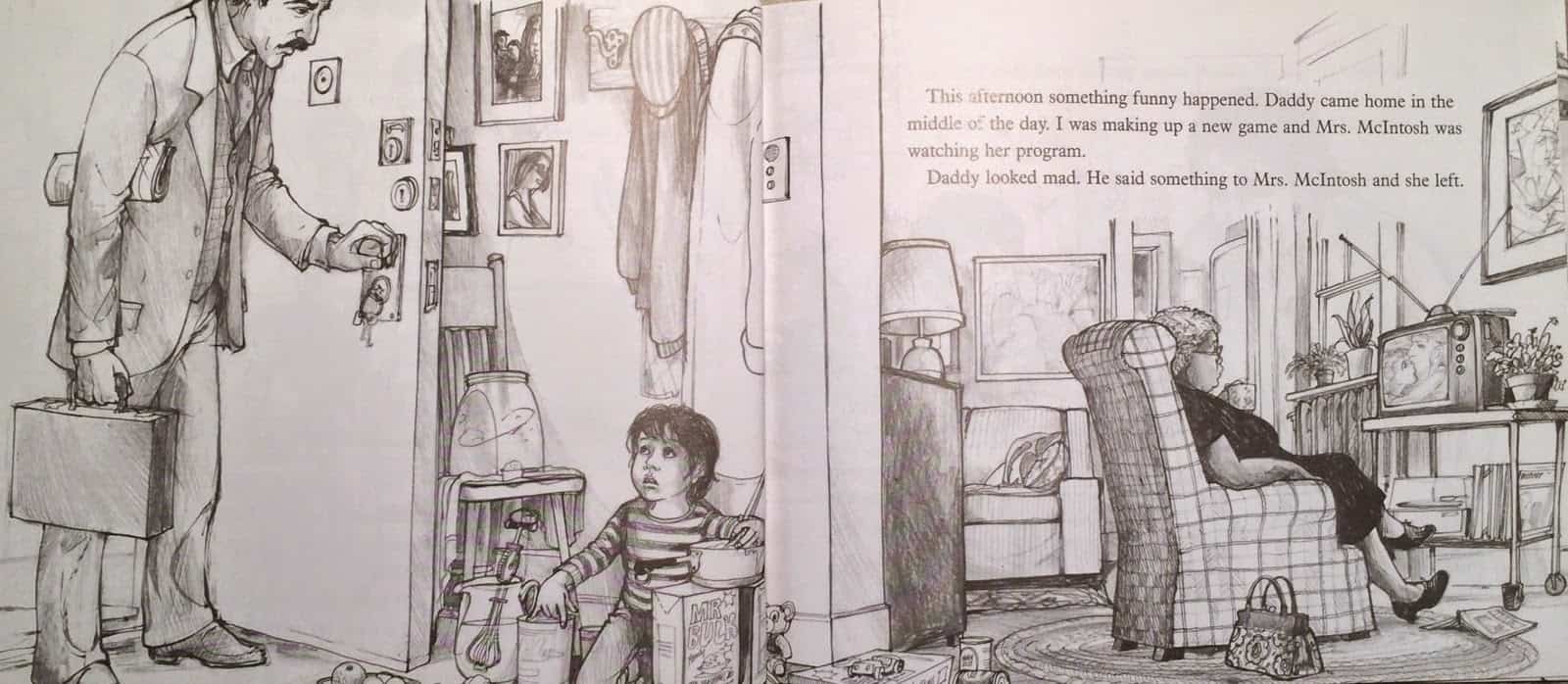

The boy’s naivety comes across via the illustrator’s composition. In the scene below, the boy sits on the floor whereas the father’s head is so much higher it is cut off by the top of the page. Notice, too, how the pillar/wall bisects the two-page spread, helping to emotionally separate the boy from his reluctant babysitter. (Reinforcing this, the babysitter faces in the opposite direction.)

DESIRE

Surface desire: The boy wants a dog. This is a common wish for a child character and clearly impossible to any reader who understands apartment living in the central city.

Deeper desire: He needs to feel secure at home and loved by his caregivers and to spend time with his own parents.

In a fairy tale, when a family member leaves home, this is known as ‘Absentation’.

OPPONENT

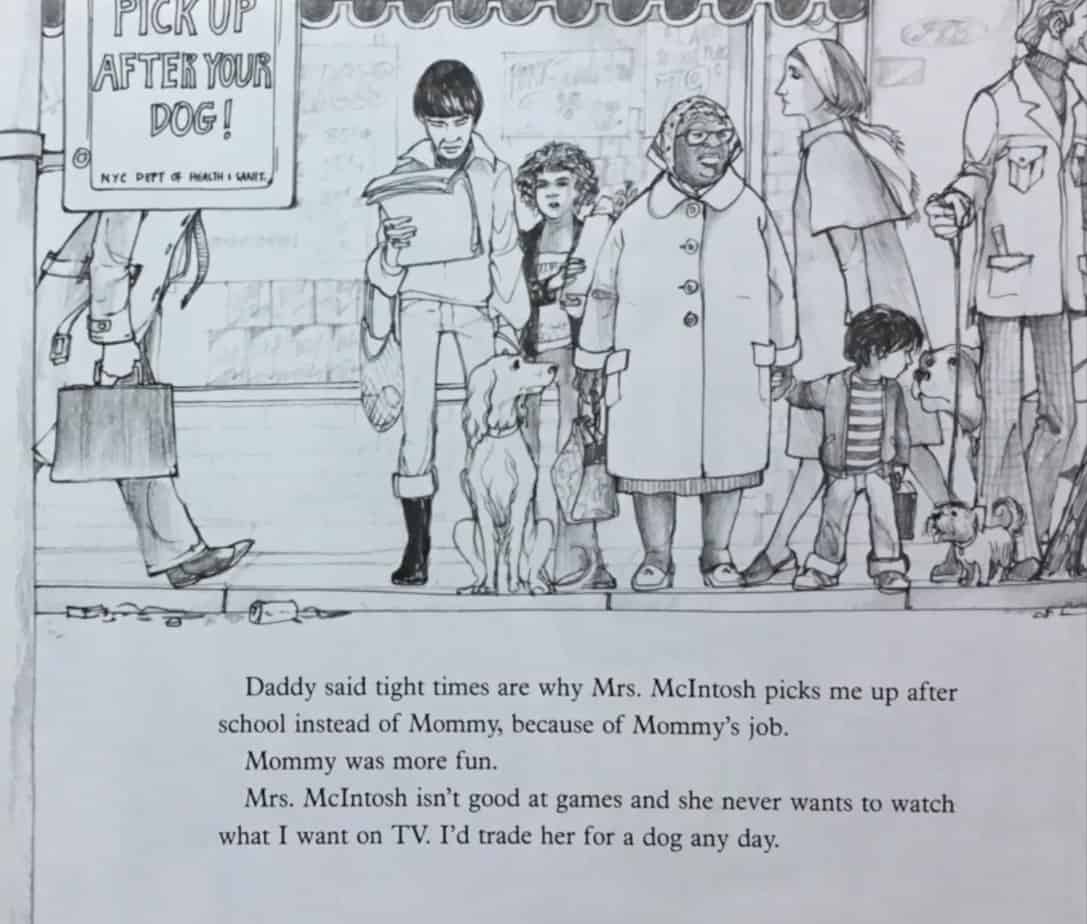

A typical parenting ideology of this era was that preschool children are best cared for by their own mothers, emphasis on mothers. Off the page, the boy’s mother hire an older woman called Mrs McIntosh to supervise their son while the boy’s mother goes out to work. Significantly, Mrs McIntosh is Black. She is clearly as much a hostage of the economic (as well as the social situation) as this white family is. This part of the picture book dates it. A contemporary picture book would be more aware of racism and the problem of depicting a distant and unsympathetic Black person in a cast of empathetic white characters. Instead, it’s completely up to the reader to have sympathy for Mrs McIntosh, and sympathy derives only from knowledge of what’s going on in the wider milieu.

Mrs McIntosh functions as an opponent to the boy because she has no energy to be caring for energetic young children and also she is not his own mother.

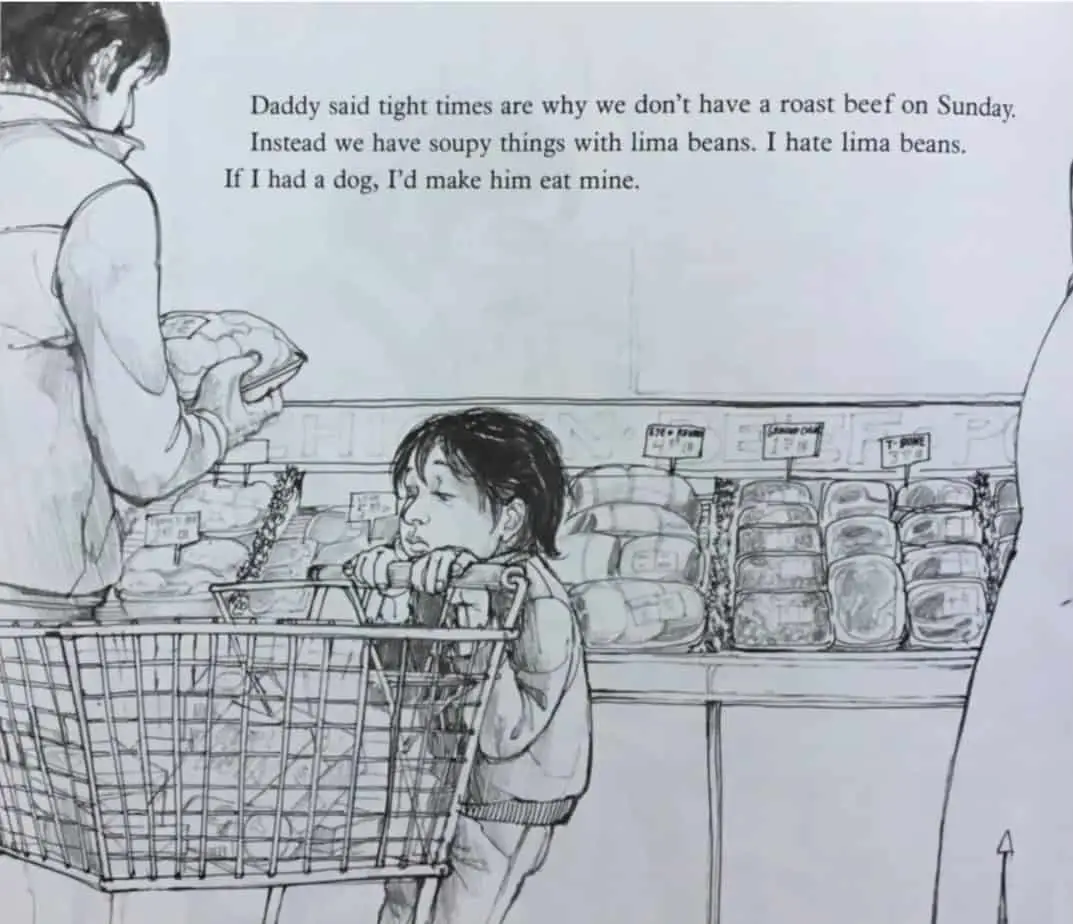

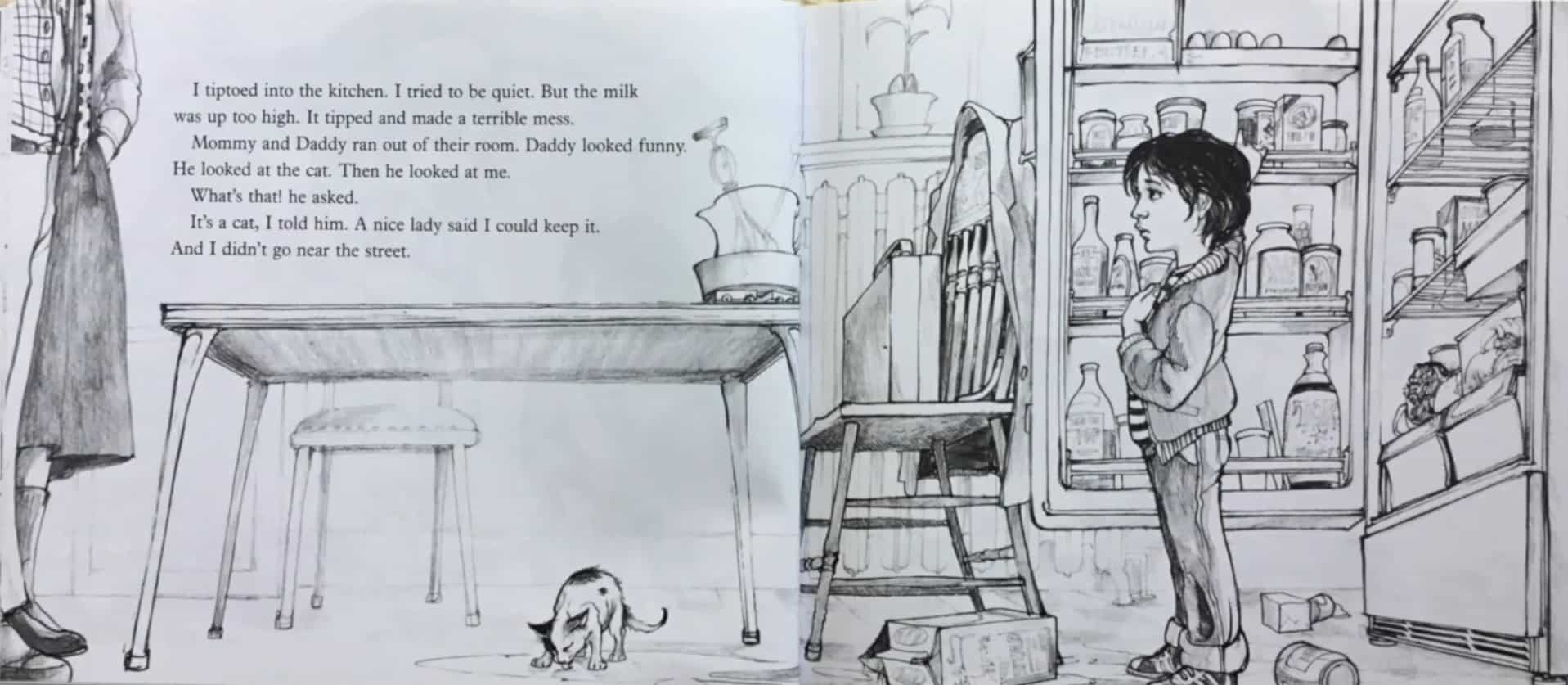

The bigger opponent is the wider world of the economy in which people have less disposable incomes and are losing their jobs. This is beyond the realm of what the boy can know. So the storytellers open the story with specific examples of what it feels like to have not as much money as before. Lima beans are utilised as stock yuck. (It’s usually a green food used for this purpose.) This detail puts the story back into the late seventies, early eighties. Families going through economic deprivation today are more likely to buy highly sugared foods, which are cheaper for the calorie. Compared to foods full of empty calories, lima beans aren’t all that cheap anymore (at least that is the case here in Australia). The food landscape has changed over the last 40 years.

PLAN

The boy’s plan is to keep asking for a dog until he gets one (because this is how kid logic works). This plan to get a dog is a McGuffin sort of plan — it’s tangential to the ‘real’ story going on, the one about a family dealing with economic deprivation and the loss of an income.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

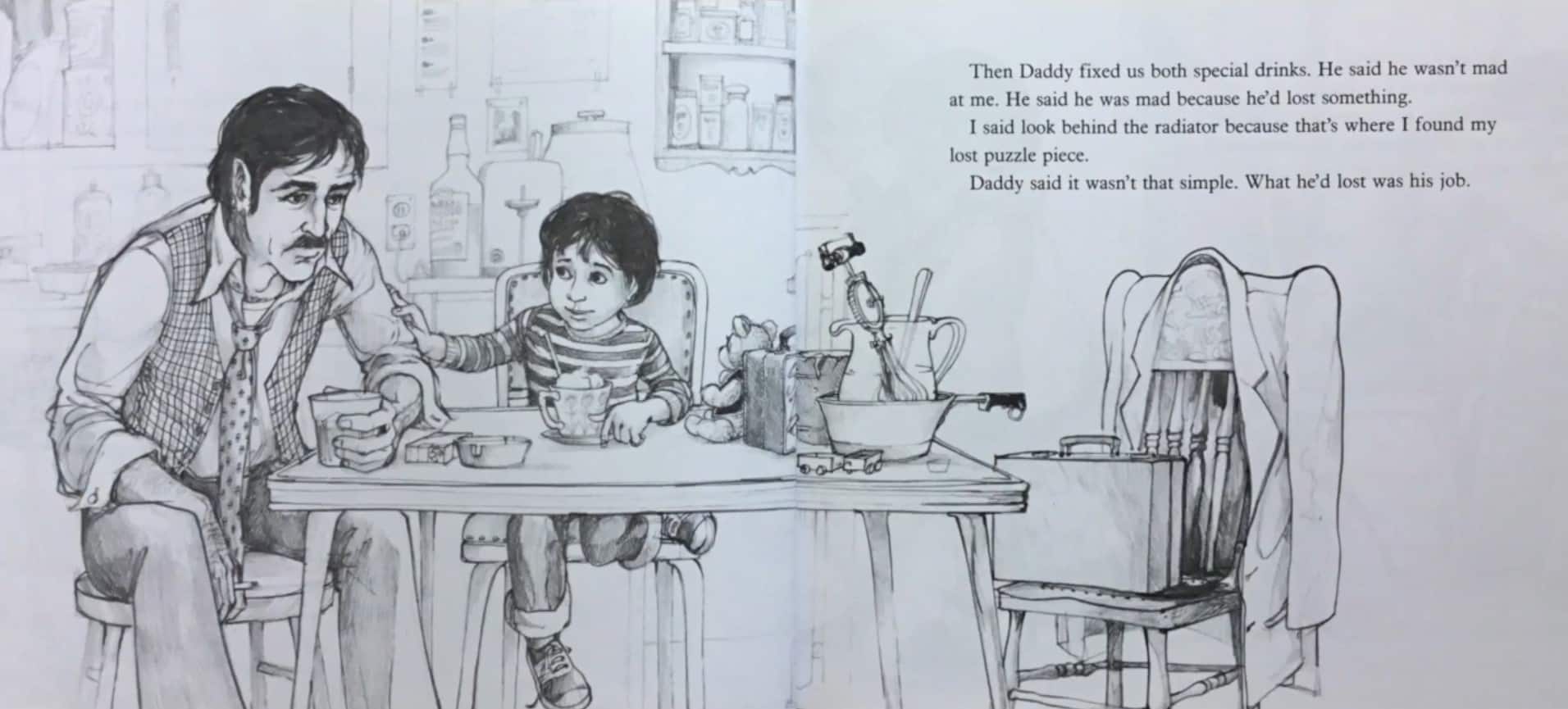

The father comes home and tells his son he has lost his job.

Schart Hyman does a wonderful job of depicting the emotional state of the father.

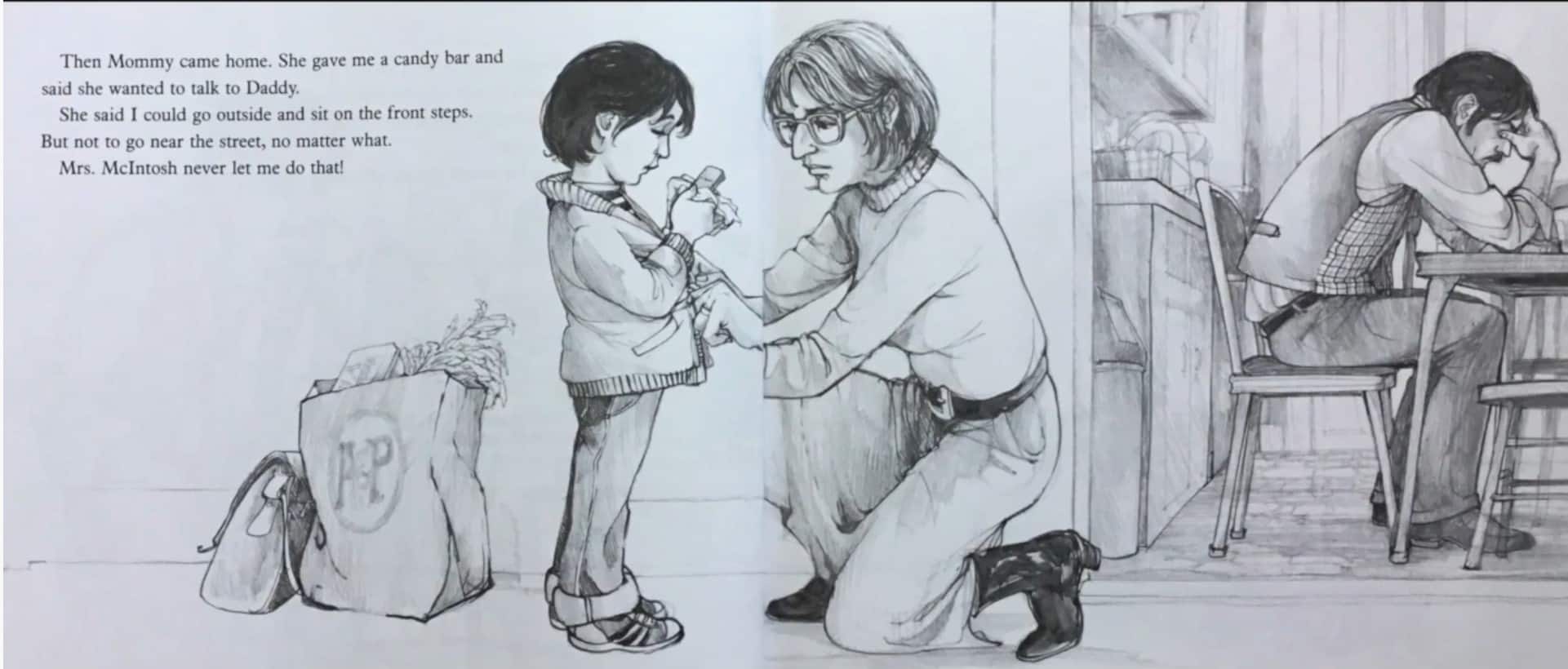

Notice how the mother tells her son to go outside and sit on the steps, but not to go near the street, “no matter what”. This may remind you of Little Red Riding Hood, in which the mother warns Little Red Riding Hood not to talk to strangers as she walks through the forest.

Vladamir Propp analysed the plots of fairytales and came up with a list of plot points which may or may not occur in any given fairytale. The scene where an adult tells a young character not to do something is known as ‘interdiction’.

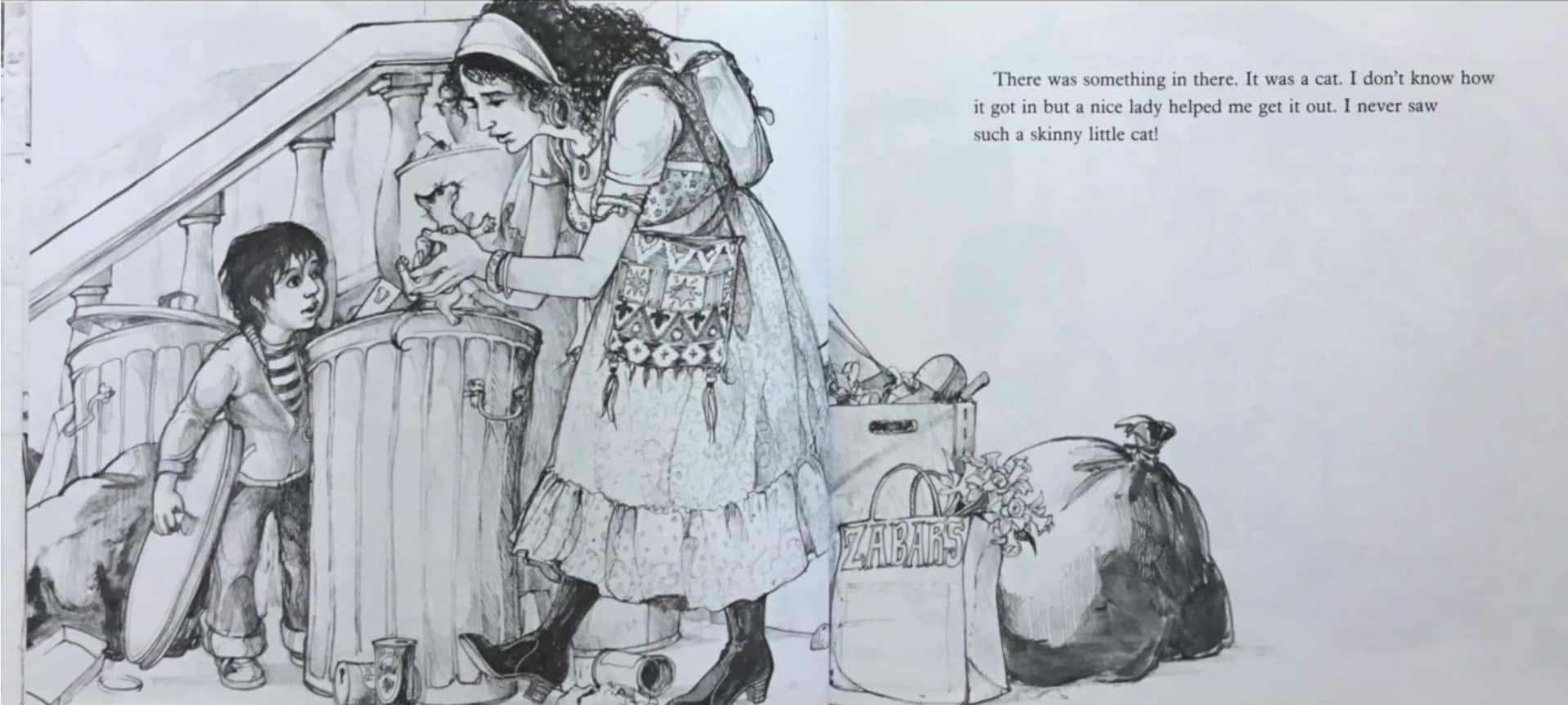

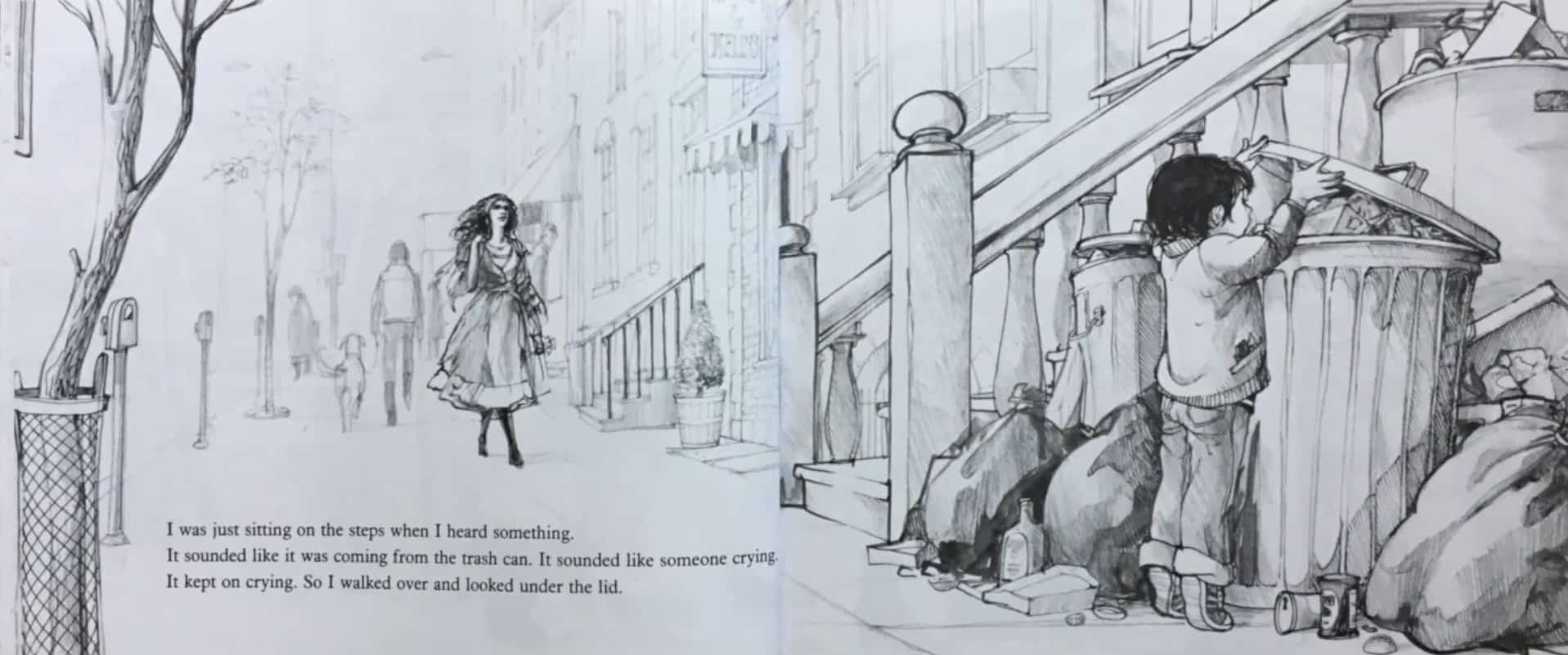

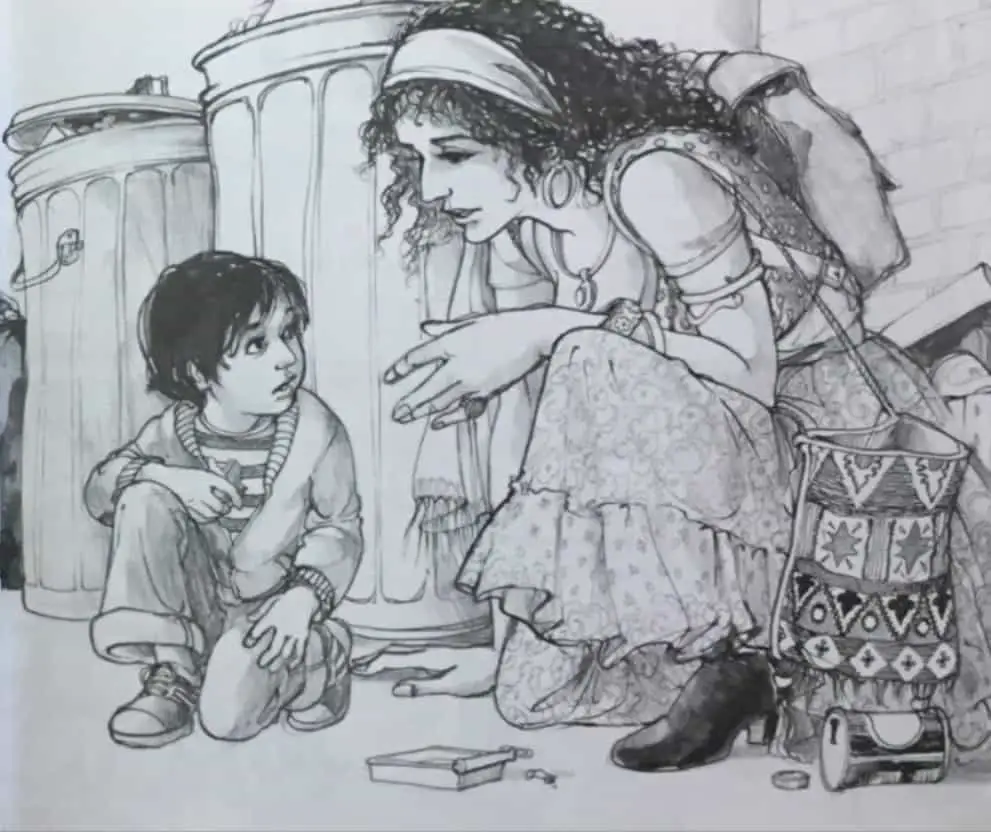

While the boy is told to wait outside on the steps a ‘Donor’ turns up in the form of the young Bohemian woman who helps him rescue a kitten from the trash can and (unhelpfully, to be fair) tells the boy he can keep it.

In a fairy tale, this character might be a fairy godmother or a talking tree or a talking animal. The storytellers of Tight Times have come close to creating a talking object when the boy hears ‘crying’ coming from inside the trash can.

This young woman is the New York, late 1970s equivalent of a fairy godmother or a benevolent witch. Notice her arm bangle with the snake, suggesting some kind of magical power. (In reality, she’s a hipster young woman with little experience of parenting.)

ANAGNORISIS

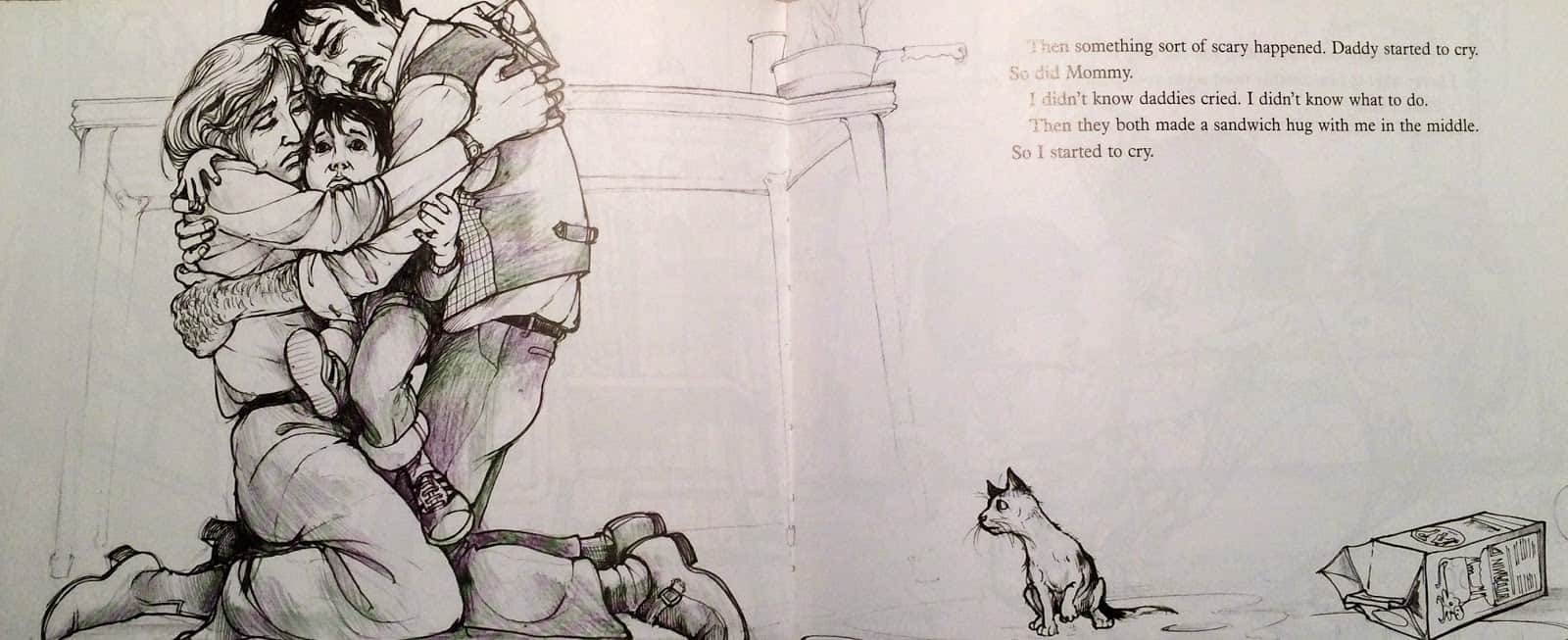

Outside, the boy learns the kitten has been crying from inside the trash can. When he rushes back inside, he learns that what happened outside on his own preschooler’s version of an adventure has been mirrored inside his parents’ bedroom, and now he sees his father cry for the first time ever.

Unfortunately, boys and men still need to be explicitly taught that it’s okay to cry. (In New Zealand the ‘Soften Up Bro’ campaign is aimed at Māori and Pasifika men.)

He didn’t know that fathers could cry. When his parents hug him ‘in a sandwich’ configuration, he learns that they love him no matter what.

The author has made use of the trope of the spilt milk to elicit this ‘last straw’ display of emotion. The father isn’t crying because of the spilt milk, but this small calamity simply tops it all off.

NEW SITUATION

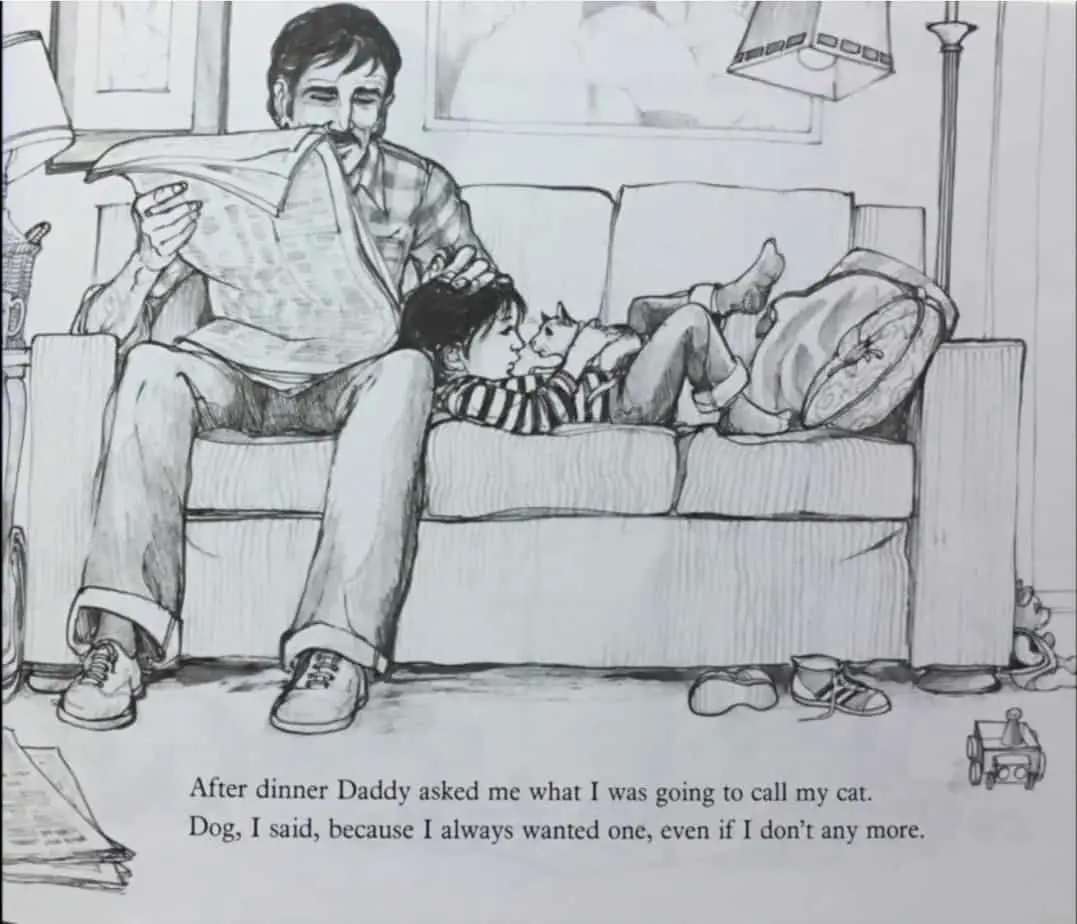

When the child gets the kitten, and when his father stops crying, the boy is happy.

A story feels finished when a character either gets or does not get what they wanted at the surface level of the story. In this case, the boy has got a compromise, which he recasts as just as good. It is funny that he calls the cat ‘Dog’, and gives us an insight into his state of mind. When he has his ‘Dog’, we know that desire thread of the story has been tidied up.

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

The young boy is happy because he is loved, and the wider world cannot affect him too much.

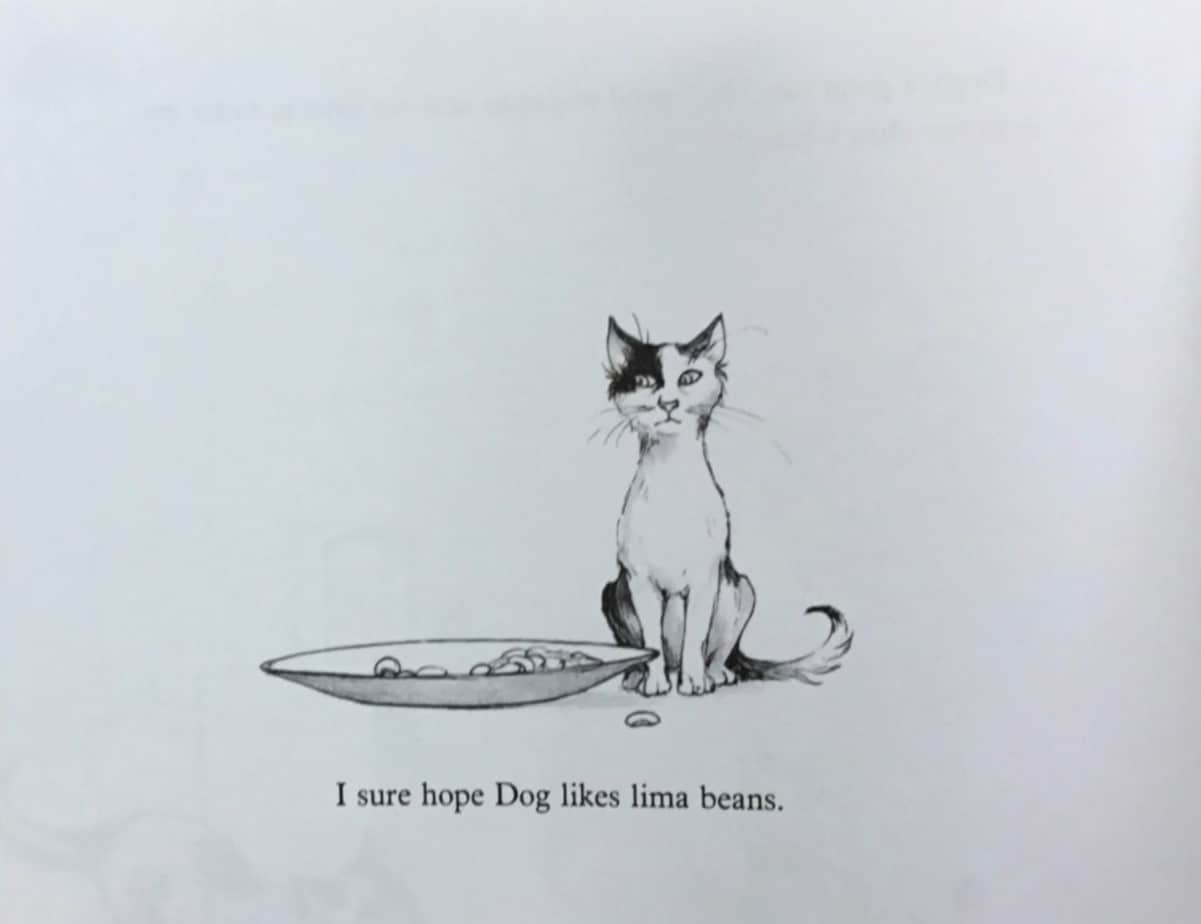

The picture book ends on a ‘wink’. Sometimes the wink at the end suggests a repeating story. In this case, the wink suggests the tight times will continue for a while yet, but because of the cat, these times will be bearable.

RESONANCE

This story is a contemporary story but makes use of very old narrative tricks to tell an affecting story, as outlined by Vladimir Propp. When the boy is cared for by his parents, and when the kitten is cared for by the boy, this also creates a mise-en-abyme effect in which caregiving trickles down. The storytellers have made use of a literal ‘save the cat’ moment to elicit audience empathy for the child.

There is also a deeper symbolism running throughout this story, working on a subconscious level. The dedication page suggests the trash can is important, and it is. (Not just because it foreshadows a kitten getting into the bin.) The lid dislodged on the bin echoes the emotion that comes out of the father, who normally ‘keeps a tight lid on things’.