Outside is the big world, and sometimes the little world succeeds in reflecting the big one so that we understand it better.

Fanny and Alexander, Ingmar Bergman

Stories featuring vast size differentials are as old as storytelling itself. These differentials can be created in various different ways, and are much utilised across children’s stories in particular:

- A normal sized person pitted against a giant or ogre

- A normal sized person who enters a land in which everyone else is tiny or huge

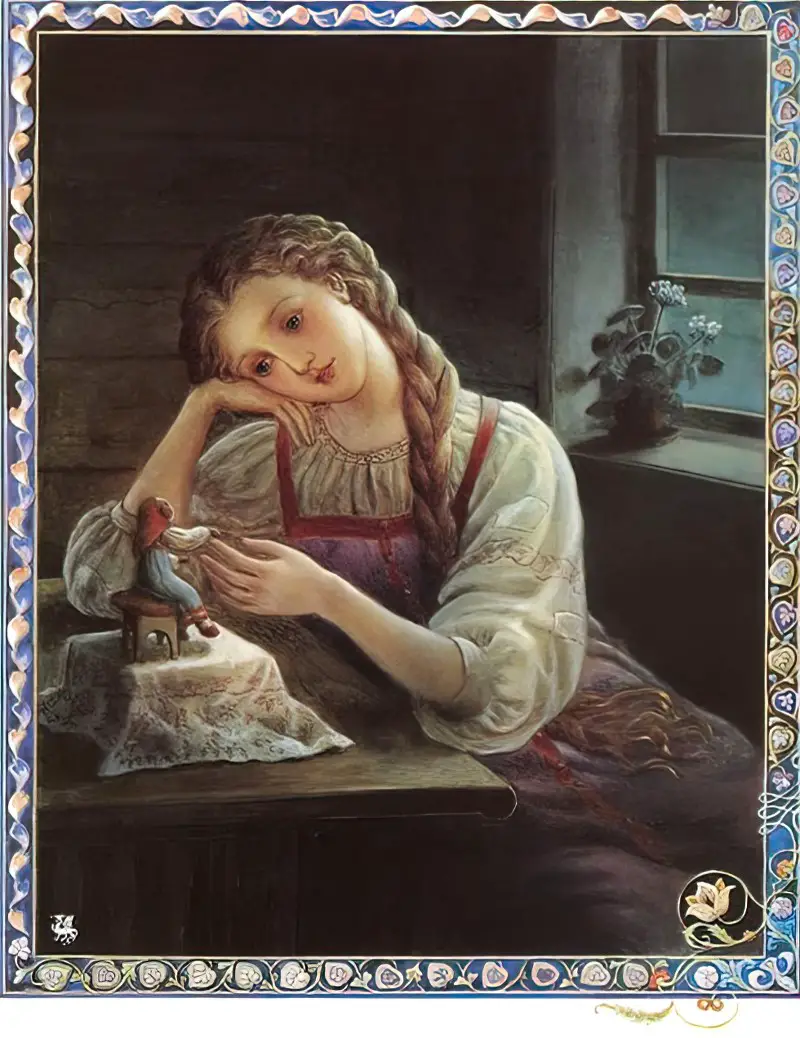

- Toys as tiny characters

- Animals as small characters

- Fairies in all their variations: dwarves, goblins, pixies etc., all of them much smaller than humans.

- Familiars, which are sometimes fairies, sometimes the spirits of dead children or other family members.

Go back far enough in time, and the tiny human was not fictional, but real in the collective imagination. A tiny human was known as a ‘homunculus‘, which means a very small person. The plural is homunculi. This was originally a medical term which comes from alchemy. People believed in the homunculus for much longer than we might imagine today. It was only in the nineteenth century that we learned a bit more about how humans come about, so now the tiny human becomes a fictional character for most people.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE MINIATURE

It was trendy in Elizabethan times to collect objects in the miniature. (Jacobeans also loved the miniature — perhaps even more so.)

Fairy stories took off in Elizabethan times. Miniature objects took off as consumer items:

- Tiny almanacs

- Tiny printed books e.g. Diurnale Moguntinum (1468)

- Cabinets of curiosities

- Elaborate doll houses

- Little people used as spectacle. See for example the story of Jeffrey Hudson.

It was understood that the microcosm represents the macrocosm.

WHY DO STORYTELLERS LOVE MINIATURE WORLDS?

How are tiny humans useful in storytelling? Here is writer Emma Donoghue, explaining how when rewriting fairytales she took tales from the oral tradition and simply considered them in metaphorical terms.

My method was mostly metaphorical: what if Thumbelina wasn’t actually small, she just felt small.

Emma Donoghue

By making something unusually small, a storyteller can turn the everyday into something remarkable. Likewise, a miniaturised item is a luxury item. A distinction is drawn between the homely and the exotic.

Flight is very common in children’s stories. When a character shrinks, this means they can ride on the back of something that actually flies (or a fantasy creature that actually flies).

In this music video featuring a series of still, the viewer is lulled into an entranced state which plays with our sense of scale.

One of the powers of attraction of smallness lies in the fact that large things can issue from small ones.

Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space

Another function of reducing something in size: It becomes manageable and also laughable. What once was scary is no longer.

But it also works in the exact opposite way:

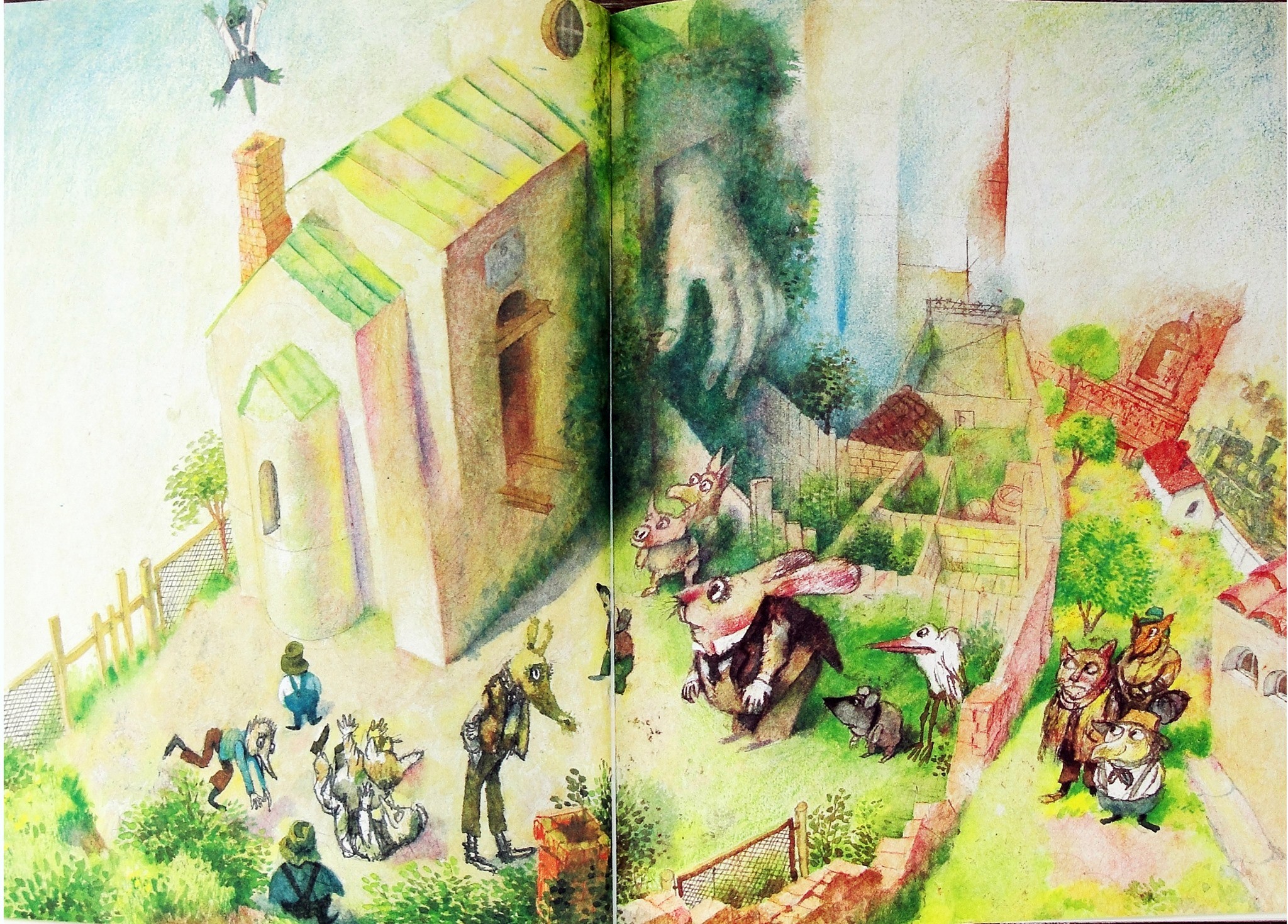

Animal stories are the stuff of an imaginative child’s delight: Kenneth Grahame’s Ratty and Mole, C.S. Lewis’s beaver family, Beatrix Potter’s Benjamin Bunny. In these stories, impossibility is key. “Lucie opened the door: and what do you think there was inside the hill? – a nice clean kitchen with a flagged floor and wooden beams – just like any other farm kitchen” . . . only suspiciously smaller. In fact, everything in Beatrix Potter’s Mrs. Tiggy-Winkle is suspiciously small, including the washerwoman herself, who has other strange features: a nose that goes “sniffle, sniffle, snuffle” and prickles rather than pincurls under her cap. But none of her animal-like qualities stops Tiggy-Winkle from living a very person-like existence, wearing a print gown and apron while she irons out her neighbors’ waistcoats. This is a common animal story conceit: away from the familiarity of home, a child encounters fantastical creatures, the impossible nature of which she only slowly registers. (Tiggy-Winkle is a hedgehog!) At which point, the child seems to awaken; perhaps it was all a dream. But was it? The evidence points in both directions, a la Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland.

Rebecca D. Martin

Reimer and Nodelman write that tiny characterisation is used as a metaphor for childhood in children’s literature:

Reducing the size of their characters, or bringing miniature objects to life, is a[nother] technique children’s writers use to explore the nature of childhood. In Hans Christian Andersen’s Thumbelina, for instance, a girl as small as a thumb has to cope with a world made for much bigger people. In Lynn Reid Banks’s The Indian In The Cupboard, a plastic toy comes to life and interacts with a human child. In Mary Norton’s The Borrowers, tiny human beings who live within the walls of a normal-size house survive by “borrowing” objects and adapting them to their own use.

These miniature human beings and living dolls and toys can all be read as metaphoric representations of children. Like dogs or pigs or rabbits, the miniature beings are much smaller than the creatures who control them. But unlike animals, toys and miniature humans have no instinctual defences, no innate ability to cope with the dangers of life in the wild.

The Pleasures of Children’s Literature, Reimer and Nodelman

Lilliputian

One of the early classics was of course Gulliver’s Travels by Jonathan Swift, first published in 1726. By asking the reader to see human society in miniature, Swift is asking us to take a good, hard look at ourselves:

Shipwrecked and cast adrift, Lemuel Gulliver wakes to find himself on Lilliput, an island inhabited by little people, whose height makes their quarrels over fashion and fame seem ridiculous. His subsequent encounters – with the crude giants of Brobdingnag, the philosophical Houyhnhnms and the brutish Yahoos – give Gulliver new, bitter insights into human behaviour. Swift’s savage satire view mankind in a distorted hall of mirrors as a diminished, magnified and finally bestial species, presenting us with an uncompromising reflection of ourselves.

Goodreads marketing copy

‘Lilliputian‘ is now used as an adjective to describe these small worlds in fiction.

Though Gulliver’s Travels doesn’t have good things to say about humanity, miniatures more typically say both good and bad things:

In many books about toys and other small creatures, the simplification of the miniature is itself a central concern. The small creatures of children’s fiction tend to express both the virtues and the vices of smallness and limitation. They are exquisitely delicate but also vulnerable, and often quite small-minded.

The Pleasures of Children’s Literature, Reimer and Nodelman

By ‘small-minded’, it is explained that this means that the characters have responded to their physical condition by becoming unadventurous and inflexible.

‘Miniatures’ refers here to books about tiny people, but includes heroes such as mice, who are naturally small, living in an over-sized world.

Further Examples of The Miniature In Storytelling

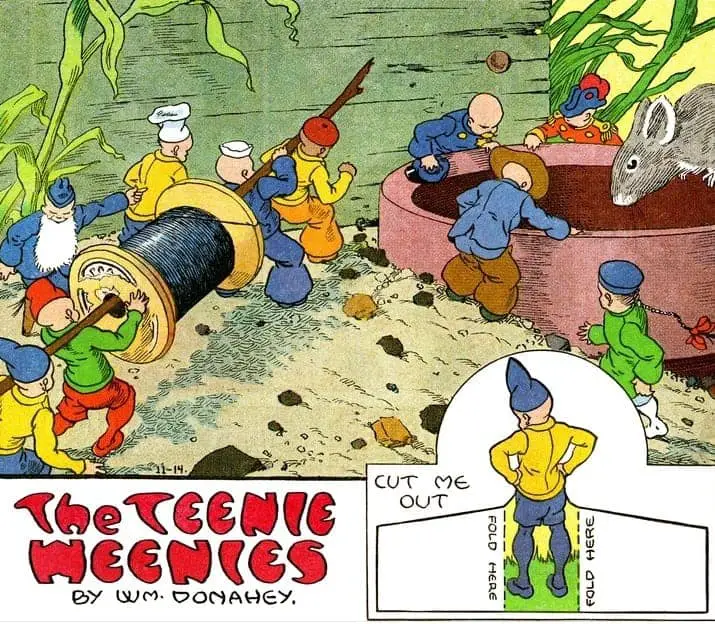

The following two stories are about mice, which not at all unusual — popular stories starring mice appeared every couple of years during the 20th century and keep on coming. (Interestingly, the mouse in Thumbelina goes against the usual characterisation of casting mice as nice.)

THE MOUSE & HIS CHILD

Thumbelina can be controlled by whatever larger creature comes along, as can the mechanical father and son who are the main characters in Russell Hoban’s The Mouse and His Child. As Lois Kuznets suggests, then, characters like these “suggest the relatively powerless relationship of human beings to known or unseen forces: their dreadful vulnerability”. When these small beings prevail over insurmountable odds, as they almost always do, they represent a potent version of the typical underdog story […] The very small can triumph over the dangerously large, the very powerless over the exceedingly powerful.

STUART LITTLE

Books about miniatures tend to focus on the physical difficulties that their characters face and their ingenious solutions to them. In Stuart Little, E.B. White describes his small protagonist’s troubles with ordinary toothpaste tubes and drain-holes. In The Borrowers, Norton shows how the Clock family adapts postage stamps to wall paintings, spools to chairs, and children’s blocks to tables. Much of the pleasure such books offer depends on their readers’ delight in objects that are just like other objects but smaller.

The Pleasures of Children’s Literature, Reimer and Nodelman

I believe we carry that fascination for miniature objects into adulthood. This explains the current interest in tiny houses, popular conceptually as a wish fulfilment for a simple life, though perhaps not so comfortable to live in long term. In fact, the movement to encourage economically disadvantaged populations into small houses en masse is bolstered by the idealisation of the tiny house.

THE BORROWERS BY MARY NORTON

Thumbelina is unlike more modern stories about little people in that Thumbelina’s is a life and death story, sans irony:

Even the triumphs of miniatures tend to be little ones. The Borrowers’ epic adventure is a trip out of the house and into the adjoining field. Readers’ consciousness of the relative insignificance of these creatures and their triumphs tends to give an edge of irony to these books. Readers seem to be expected to both identify with the Borrowers and separate themselves from them, in both cases because of their smallness

The Pleasures of Children’s Literature, Reimer and Nodelman

Townsend also enjoys The Borrowers:

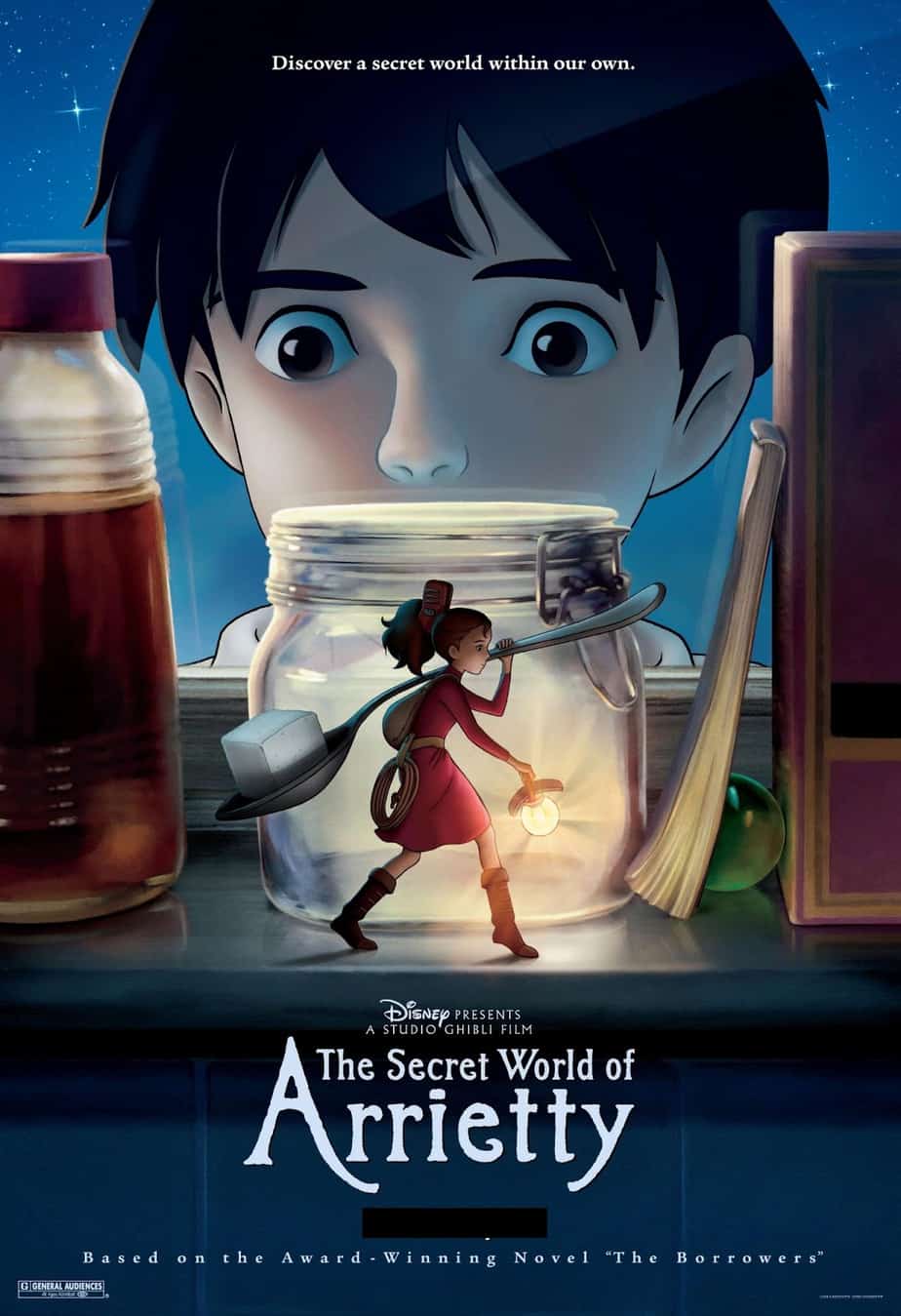

In contrast to large allegorical and mythic themes is the small-scale, magnifying-glass fantasy of Mary Norton’s The Borrowers series which began with The Borrowers (1952). These books create, with perfect consistency and attention to detail, a tiny world within our own. Borrowers are little people who inhabit odd corners of houses: under the floorboards, for example, or anywhere else that provides a safe retreat. They live by “borrowing” from the human occupants of the house. Over the years Borrowers have grown smaller and fewer, and now you only find them in “houses which are old and quiet and deep in the country — and where the human beings live to a routine. Routine is their safeguard: it is important to them which rooms are to be used, and when. They do not stay long where there are careless people, unruly children, or certain household pets.”

“Our” particular family of Borrowers are Pod, the father, Homily, the mother, and little Arrietty (even their names are scraps of borrowed human names). They live below the wainscot under the grandfather clock, and Clock is their family name. Here is a glimpse of them at home:

The fire had been lighted and the room looked bright and cosy. Homily was proud of her sitting-room: the walls had been papered with scraps of old letters out of waste-paper baskets, and Homily had arranged the handwriting sideways in vertical strips which ran from floor to ceiling. On the walls, repeated in various colors, hung several portraits of Queen Victoria as a girl; these were postage-stamps, borrowed by Pod some years ago from the stamp-box on the desk in the morning-room. There was a lacquer trinket-box, padded inside and with the lid open, which they used as a settle; and that useful stand-by — a chest of drawers made from match-boxes […] The knight [from a chess set] was standing on a column in the corner, where it looked very fine, and lent that air to the room which only statuary can give.

Homily is a houseproud, nervous little woman. Pod is a tough, resourceful little man, but he is beginning to feel his age, and a Borrower’s life is not an easy one — it involves perilous mountaineering exploits over tables and up to kitchen shelves. And poor Arrietty, at nearly fourteen, is bored and lonely.

In The Borrowers, a human boy comes to stay in the house and meets Arrietty; he does some borrowing himself on the Borrowers’ behalf, so that for a time they enjoy a life of undreamed-of affluence. But he borrows more than is wise; things are missed and the Borrowers’ household is exposed; they are smoked out and have to take to the fields. The Borrowers Afield (1955) and The Borrowers Afloat (1959) trace their adventures after this forced emigration. In The Borrowers Aloft (1961) they find a home in the model village built by a retired railway man, Mr Pott, but are kidnapped by his unpleasant rival Mr Platter. Ever-resourceful, they build themselves a balloon in order to escape from an upstairs window of Mr Platter’s house.

The author then indicated that the series was complete, but in 1982 The Borrowers Avenged effortlessly jumped a gap of twenty-one years and followed straight on from its predecessor. After their escape from Mr Platter, the Borrowers are again looking for a home, and this time they find an ideal one in a rambling old rectory with only caretakers and the odd ghost in residence. Arrietty still has a dangerous longing to talk to Human Beans, and another for the fresh air and wider world; and there’s a hint of romance when she meets Peregrine Overmantel, a Borrower of the vestigial upper class and also a poet and painter. The Platters get their comeuppance and the Borrowers are safe — or as safe as Borrowers can ever be.

John Rowe Townsend, Written For Children

Margaret Blount has this to say about The Borrowers, and other similar tales:

The quality of Lilliput and the delight of smallness which makes objects increase in pleasure and value in inverse proportion to their size so that a human size is useful, child’s size agreeable, doll size delightful and doll’s house size a work of art, outweigh the other considerations of Gulliver’s first voyage. Smallness is of no particular interest without something to measure it by, and both Mary Norton’s and T.H. White’s miniature fantasies are in retreat from life of average size, and have to hide from it. Contact with humans is in some way fatal — mouse societies are the same. The People in T.H. White’s Mistress Masham’s Repose, 1947, i colony of Liliputians living on an island, are self-sufficient until contact with the child Maria encourages them to make use of human artefacts, not always to their advantage. Mary Norton’s The Borrowers, 1952, experience the same thing. When the precious balance is upset — when Homily, Pod and Arietty have their home filled with doll’s house furniture by the Boy, when the People are overwhelmed with gifts from Woolworths — the relationship has to end and the small retreats from the larger.

Margaret Blount, Animal Land

Film Adaptations of The Borrowers

There is a 1997 British/American film for children called The Borrowers, but I recommend this is avoided in favour of the Japanese version. 1997 CGI no longer looks much good to a modern audience, and this type of fantasy is beautifully suited to animation. There is also a lesser known film adaptation from 1973.

The Japanese Studio Ghibli made a beautiful animated film adaptation of The Borrowers series, and unlike what Hollywood tends to do with female protagonists (in which even books with female names as the title tend to be changed to something less ‘gendered’ in order to ostensibly avoid alienating the boys), Hayao Miyazaki took the main female’s name and used it in the title.

Studio Ghibli loves the miniature world as much as it loves flight symbolism. In The Cat Returns, the main character takes a fantastical trip to The Cat Kingdom, where she becomes the size of a cat.

THE RETURN OF THE TWELVES

Another small world was created n The World of the Genii (American title The Return of the Twelves). A boy called Max finds, under the floorboards of an old house not far from Haworth, the toy soldiers of the Brontes, as described by Branwell in The History of the Young Men. It seems that the chief genius Brannii breathed life into them. Now they can revive. And when they do, their faces become bright and living, sharp and detailed instead of blurred and featureless with age. These tiny men are characterized not only as a group — they are soldiers, organized and resourceful in all they do — but as individuals: most strikingly their patriarch, the kindly and dignified Butter Crashey. And what more natural than that when in danger they should “freeze” into mere wood?

John Rowe Townsend, Written For Children

THE POWER OF THREE BY DIANA WYNNE-JONES

Another different and ingenious world is created in Power of Three (1976), which is set on the Moor, a sunken plain occupied by the People, or Lymen, and by the strange, water-dwelling, shape-shifting Dorig. There are also the noisy Giants, who trample over the place from time to time; and a brilliant revelation about the Giants, guaranteed to make the reader blink, changes the whole scale of the story. Fire and Hemlock (1984) blends a great deal of traditional material with real-life relationships in a long and ambitious book for older readers.

John Rowe Townsend, Written For Children

THE MINNIPINS BY CAROL KENDALL

The British title is The Minnipins but the American title is The Gammage Cup. This book was published in 1959.

The appeal of the book lies largely in the neatness and consistency of the portrayal of the Minnipins’ country. The valley of the Watercress River, with its dozen villages — Great Dripping and Little Dripping, Slipper-on-the-Water and Deep-as-a-Well — is exactly the place in which to find such a right little, right little, smug little people. The Whisper of Glocken (1965) is a sequel.

John Rowe Townsend, Written For Children

OTHER EXAMPLES

Wiplala is a tiny little man who can do magic. He calls this magic a ‘tinkle’, and sometimes makes a mistake.

Nella Della, Johannes and Mr. Blom find all this a bit difficult, but in the end they have many exciting and funny adventures.

“She saw: first, a square opening, about eight inches wide, in the lowest step…finally she saw that there was a walnut shell, or half one, outside the nearest door…she went to look at the shell—but looked with the greatest astonishment. There was a baby in it.”

So ten-year-old Maria, orphaned mistress of Malplaquet, discovers the secret of her deteriorating estate: on a deserted island at its far corner, in the temple long ago nicknamed Mistress Masham’s Repose, live an entire community of people—”The People,” as they call themselves—all only inches tall. With the help of her only friend—the absurdly erudite Professor—Maria soon learns that this settlement is no less than the kingdom of Lilliput (first seen in Gulliver’s Travels) in exile. Safely hidden for centuries, the Lilliputians are at first endangered by Maria’s well-meaning but clumsy attempts to make their lives easier, but their situation grows truly ominous when they are discovered by Maria’s greedy guardians, who look at The People and see only a bundle of money.

More recently, Pixar’s Inside Out makes use of tiny people who live inside Riley’s brain. These ‘people’ are presumably too small for anyone to see, existing more at the level of atoms than of your thumb. However, these characters are ‘regular’ sized in their own worlds.

ALSO INTERESTING

If different species could hypothetically scale up or down, as from an insect into a man-sized creature, there’s no way the creature would survive. Dutch thinker Arne Hendricks (from a tall country and 195cm himself) has researched the topic of humans and animals and scale and shrinking. He has worked out that humans could be shrunk to the size of a chicken, but no smaller. This is because we’d then be sacrificing brain power etc. He has proposed that we deliberately try to breed ourselves smaller to shrink our carbon footprints accordingly. His blog is a fascinating exercise in hypothetical futures.

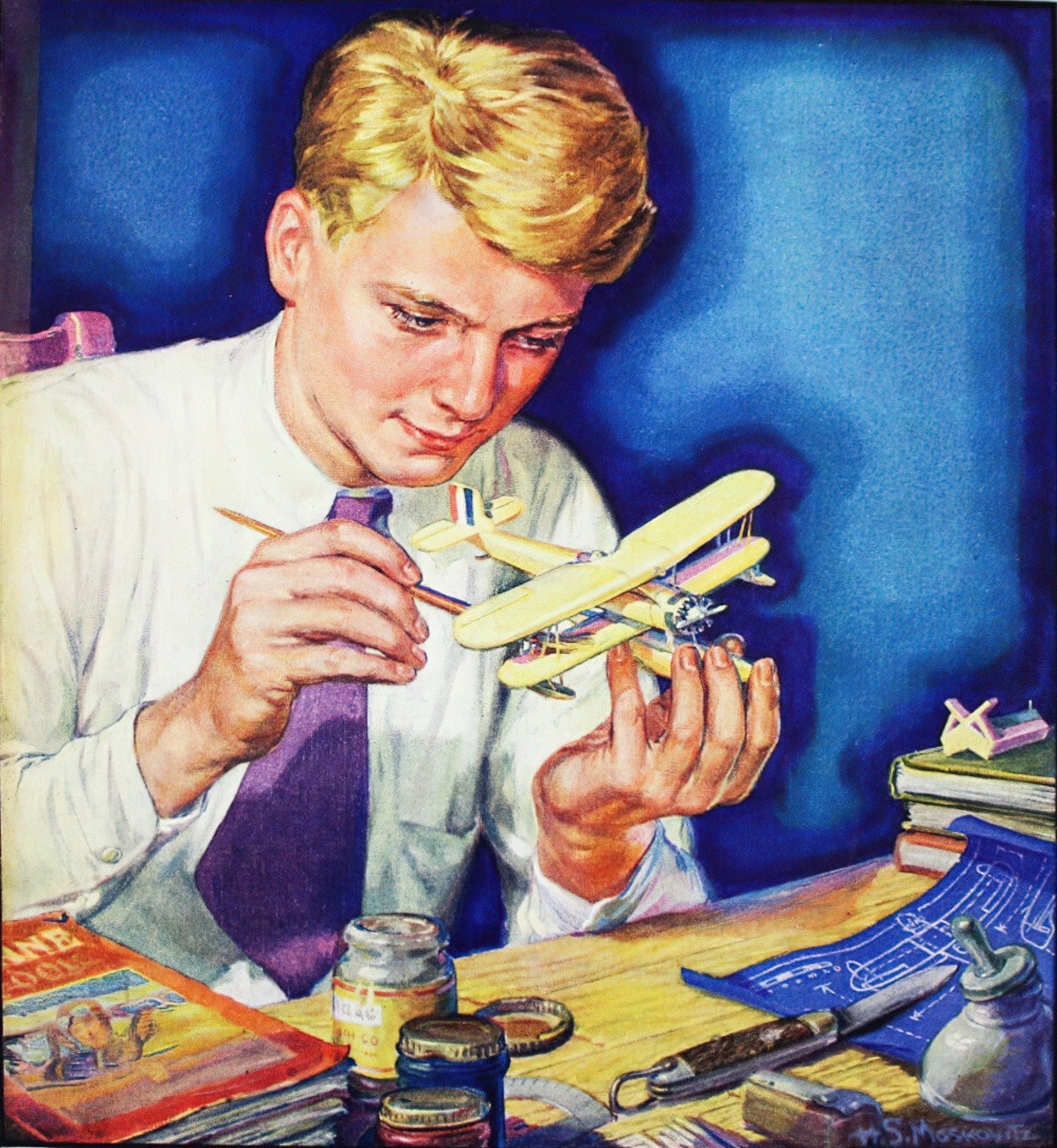

Header painting: Charles Robert Leslie — The Miniature