First, what is meant by mythic structure?

In everyday English, a myth is a story which is not true. In a myth, the surface level story is not true, but the symbols running through the story say something deeper about humankind. This is what makes it true.

If you look at all the Ancient myths they have things in common. Characters go on a journey, change, then either return home a different person or find a new home.

The farthest you can travel is to come back to the place you already are and see that place with new eyes.

T.S. Elliot

This is all related to the symbolism of the labyrinth. The journey itself takes the hero into the deepest darkest parts of the soul, where the hero encounters a Minotaur (opponent). The journey out of the labyrinth is a rebirth.

Although in English we have inherited the Greek word, the labyrinth shape can be seen across many different cultures. It’s a universal symbol and this is exactly why the labyrinthine shape so beautifully represents the shape of the universal mythological story structure.

Our classical hero finally comes across a REALLY bad guy, who kills him (or not, in a tragedy) then after some spiritual awakening the hero returns home, or finds a new home (or is dead).

Sometimes you find yourself in the middle of nowhere, and sometimes, in the middle of nowhere, you find yourself.

Unknown

British novel: let’s go to a party and find a wife.

@ExistentialComics

German novel: let’s go to the wilderness and find ourselves.

Russian novel: let’s go to the depths of despair and then find out there is an even deeper level of despair we didn’t know about and go there.

Since all cultures are built on myth, the mythic story works across cultures.

ZELTZER: How much do you draw on fairy tales or myths?

URSULA LE GUIN: Well, it’s useless to differentiate them; you always end up with the same damn archetypes.

The Last Interview

Take The Pilgrim’s Progress as a fairly modern story making use of mythic symbols:

Although The Pilgrim’s Progress is allegorical, it is impossible even for an adult to read about Christian’s journey to the Celestial City in any other way than as a story. The passages through the Slough of Despond and the Valley of Humiliation, the fight with the monster Apollyon, the loss of Christian’s comrade Faithful in Vanity Fair, the crossing of the River of Death: these are actual and vivid events, as real in their own way as the mass of detail with which Defoe built up Robinson Crusoe. It may be noted that the themes of all these three books — the dangerous journey, as in The Pilgrim’s Progress, the desert island, as in Robinson Crusoe: and the miniature or other imaginary world, as in Gulliver — have served for innumerable later books, both children’s and adult, and are by no means worn out.

Written for Children by John Rowe Townsend

Mythic stories work via symbolism, the universal kind of symbolism connected to what has lately been called ‘transformative memory’. This term describes memories which are not authentic, but created by the brain to make sense of life, turning disorder and fragmentation into some kind of meaning.

‘Transformative memory’ is Janice Haaken’s term. (See Haaken’s 1998 book Pillar of Salt: Gender, memory and the perils of looking back.)

Pillar of Salt introduces the controversy over recollections of childhood sexual abuse as the window onto a much broader field of ideas concerning memory, storytelling, and the psychology of women. The book moves beyond the poles of “true” and “false” memories to show how women’s stories reveal layers of gendered and ambiguous meanings, spanning a wide historical, cultural, literary, and clinical landscape. The author offers the concept of transformative remembering as an alternative framework for looking back, one that makes use of fantasy in understanding the narrative truth of childhood recollections.

Haaken provides an alternative reading of clinical material, showing how sexual storytelling transcends the symbolic and the “real” and how cultural repression of desire remains as problematic for women as the psychological legacy of trauma.

I’ve always wanted to get as far as possible from the place where I was born. Far both geographically and spiritually […] I feel that life is very short and the world is there to see […] and one should know as much of it as possible. One belongs to the whole world, not just one part of it.

Paul Bowles, American expatriate composer, author, and translator

Myth is not a part of every story. Even Joseph Campbell himself said that there was no mythic structure to be found in 25% of stories.

The truth is of course is that there is no journey. We are arriving and departing all at the same time.

David Bowie

Raison D’être Of Mythic Stories

Myths are born of the sticky dark. That’s why the truest have survived thousands of years. They present fictional answers to primal questions: Why do tragic things happen? Which is stronger, love or death? What if death is just the beginning?

Marcus Sakey, Publishers Weekly

There are three main types of modern adventure stories, and they all make use of mythic structure. (For more on children’s adventure stories and their evolution, see The Centrality of the Adventure Story.)

MYTH IN RELATION TO FOLKTALES AND FAIRY TALES

Myths and folktales are assumed to be the very first stories in the history of humankind, closely related to rites of passage. Thus, a fairytale becomes a travel instruction for a young person on the way toward adulthood, directions on exactly how to behave in various situations. […] The hero’s task in a folktale is totally impossible for an “ordinary” human being, it is always a symbolic or allegorical depiction. Allegories (like Dante’s Divina Commedia or Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress) are also travel instructions. But the addressee knows that you cannot die and then rise from the dead, nor be eaten by a whale and then come out again, nor descend into the realm of death, and so on. When the March sisters try to follow Bunyan’s instructions for a journey, they have to “translate” the allegory into more everyday conditions. […] The modern version of a travel instruction is formula fiction in all its forms: crime novel, science fiction, horror, romance, soap opera, and so on. The addressee of these texts also knows that the story has very little to do with life. On the contrary, the text is based on detachment, especially through its exotic settings and incredible events. Many scholars have noted the similarities between fairytales and formula fiction. As early as the 1920s Propp suggested that his model for folktale analysis could be applied to novels of chivalry and other texts with fixed narrative structures.

Maria Nikolajeva, From Mythic to Linear: Time in Children’s Literature

Nikolajeva refers to Umberto Eco’s analysis of structure of James Bond movies as an example of such analysis.

- M moves and gives a task to Bond.

- The villain moves and appears to Bond.

- Bond moves and gives a first check to the villain or the villain gives first check to Bond.

- Woman moves and shows herself to Bond.

- Bond consumes woman: possesses her or begins her seduction

- The villain captures Bond

- The villain tortures Bond

- Bond conquers the villain

- Bond convalescing enjoys woman, who he then loses

Award-winning children’s authors such as Kate DiCamillo typically write with a mythic structure, though the list could go on:

[A] tendency to reflection is why DiCamillo’s style often echoes with the dark-light verities of Victorian or Edwardian children’s literature which, too, dwell on the private lives of playthings and speaking animals on heroic quests.

Canberra Times

‘Adventure story’ is the term most often used when talking about traditional mythic forms in children’s literature. For more on the centrality of the adventure story see: A Brief History Of The Adventure Story In English.

Now to the three main types of myths in modern storytelling.

1. THE MYTHIC JOURNEY

The O.G. Myth is regularly considered to be The Odyssey, a poem first recorded by Homer 800 BC.

In this kind of adventure there are often two journeys, closely linked and mutually dependent, one physical and the other spiritual. The protagonist, by means of a physical journey, experiences a growth in self-knowledge or subtle character development. An observant reader will respond to both journeys and be aware of the spiritual growth that has taken place.

Give Them Wings, edited by Saxby and Winch

The Odyssey is so well-known that marketers sometimes use ‘Odyssey’ to mean ‘mythic journey’ and audiences basically know what we’re getting:

The Odyssean myth is so powerful that even something the length of an advertisement can create powerful emotions. Check out this Coca-cola ad. (Big brands can afford to spend the most on their campaigns. McDonalds also makes excellent ads.)

“We find a model for learning how to live in stories about heroism. The heroic quest is about saying yes to yourself and, in so doing, becoming more fully alive and more effective in the world. For the hero’s journey is first about taking a journey to find the treasure of your true self, and then about returning home to give your gift to help transform the kingdom and, in the process, your own life. The quest itself is replete with dangers and pitfalls, but if offers great rewards: the capacity to be successful in the world, knowledge of the mysteries of the human soul, the opportunity to find and express your unique gifts in the world, and to live in loving community with other people.”

Carol S. Pearson, Awakening the Heroes Within: Twelve Archetypes to Help Us Find Ourselves and Transform Our World

This Home-away-home story is also very common in picturebooks. This is basically the mythic journey but in different words specifically applied to picture books.

The mythic journey is also called the (mythic) quest.

The technical definition of myth:

The story of the transformation of the soul and the stages of its illumination.

He (and it’s almost always a he) will face moral choices along the way (which we might better represent as choices within a maze, not a labyrinth). In the case of a labyrinth, the journey itself takes you further and further into yourself, into your soul, where you will face your deepest darkest fears. The journey in and out is a cycle of death and rebirth. By rebirthing, you become a different person. You basically become a shapeshifter. In the famous Greek myth, Theseus transforms from a youth into a king. It’s basically a coming-of-age story. The labyrinth is his initiation.

In order to get out alive you’ll need to find the following within yourself:

- trickery (this is why tricksters are so universally popular across storytelling)

- perseverance

- unhurriedness

- curiosity

- playfulness

- flexibility

- improvisation

- self-mastery

- smarts, because you must resist the lure of easy solutions which are not solutions at all.

Throughout the last 3000 years of history (at least), people have understood this symbolism across cultures. The shape itself actually goes back further than 3000 years, to the Neolithic (New Stone) age. The Neolithic age began around 12,000 years ago.

As a narrative structure, the mythic labyrinth/maze forms the basis of all human storytelling, across cultures. Whenever someone tells us a story, we are expecting something which conforms to this shape, with certain accepted shape variations. This is why there is such a thing as universal story structure.

Apart from The Odyssey there are a whole bunch of really old myths that all have the basic same plot: Jason and the Golden Fleece, Beowulf, Saint George etc.

A slightly more modern mythic journey is Gulliver’s Travels, published 1726.

From Gulliver’s Travels came 20th Century stories such as:

- The Hobbit by J.R.R. Tolkien

- I Am David by Ann Holm

- The Silver Sword by Ian Serraillier

- Julie Of The Wolves by Jean Craighead George (now outdated)

(Gulliver’s Travels is also the O.G. Miniature Story as well as being the O.G. Journey.)

An example of an Odyssean journey in a picture book is Where The Wild Things Are by Maurice Sendak.

Other examples of Odyssean Mythic Structures:

- The Lion King

- Thelma and Louise — a female buddy movie. Buddy movies tend to make use of mythic structure. Thelma and Louise is of course a standout Road Trip story as well, which is a modern American take on the Odyssean mythic journey, spawned by the development of America’s federal highway system in the 20th century.

- Beauty and the Beast

- The Piano — myth blended with anti-romance

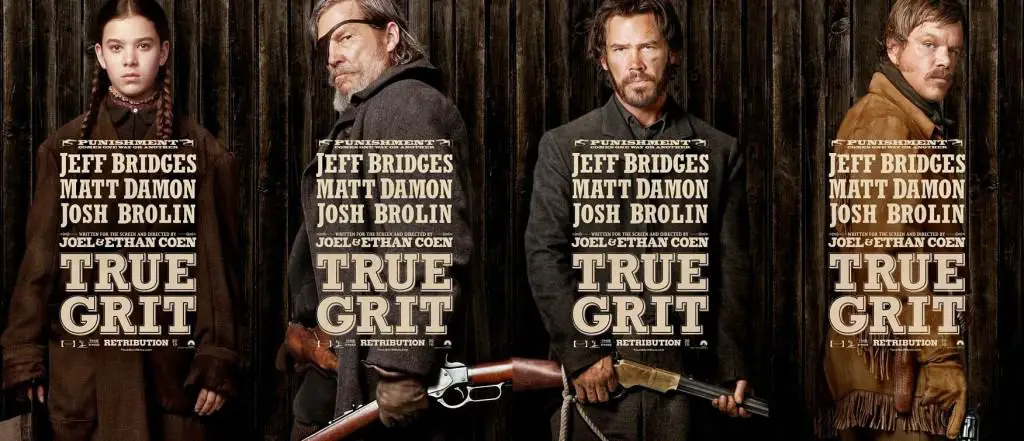

- True Grit — basically a crime story, blended with mythic structure

- Harry Potter — Typically for main characters of myth stories, Harry is a foundling, abandoned by his parents and brought up by horrible people (and written by a horrible author).

- Le Week-end — a film written by Hanif Kureishi in which the journey takes the form of a romantic weekend away with the purpose of rekindling a failing marriage

- Locke — a road trip with one on-screen character played by Tom Hardy. Extraordinarily well scripted, we really only see Tom Hardy sitting in his car. The opponents he meets on his journey come only in form of voices through his car phone. By the end of the journey he is in a different place both physically and spiritually.

- I Don’t Feel At Home In This World Anymore – an indie-film which provides an excellent example of modern use of mythic symbolism such as the labyrinth and the river. The backdrop is American suburbia. The main hero is a woman, though she is joined by a man. Interesting for its gender inversions.

- Wildlike — a 14 year old girl is sent to stay with her uncle in Alaska one summer as her mother is receiving treatment for an illness. She is soon faced with the task of running away from the uncle and making her way back to Seattle. She meets various helpers and opponents along the way, and contributes to a grieving man’s character arc as he grieves for his own wife’s recent death.

- Jolene — a 2008 film based on a story by E.L. Doctorow. A young orphan marries but in a Cinderella-like tragedy things don’t go well and she ends up on the road, meeting all sorts of people along the way, mostly horrible.

- Hunt For The Wilderpeople — a New Zealand comedy drama about the relationship between a cranky man and a boy, who go bush, pursued by the police for suspected child abuse.

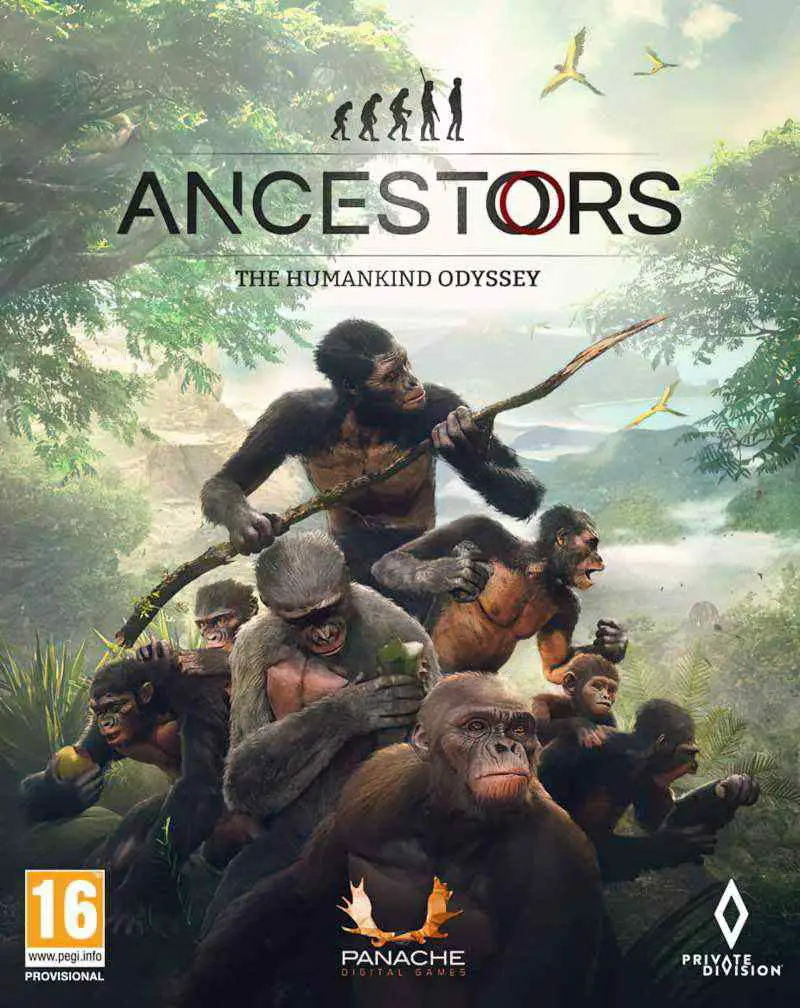

Then there are computer games, such as Halo and Red Dead Redemption.

Occasionally, the story isn’t so much about what the character learns about themselves. It is about what the main character teaches others they meet. This hero is like a sage, going from place to place fixing things. Let’s call this type of journey-person a ‘blow-in saviour’.

Blow-in Saviour describes a character who travels from place to place fixing the joint, or spreading joy, then moving on. We assume the cycle will continue.

Blow-in Saviour characters are found mainly in Westerns, detective stories and comedies. They are also found in children’s stories. Sometimes the Blow-in Saviours of children’s stories are children, sometimes they are adults. As I’ve noted before, characters in children’s stories are not always rounded to the point that they are treating others wrongly in some way. This is less true of contemporary adults’ stories.

Blow-in Saviours tend to turn up with a community is in trouble. (But not always.) Mary Poppins turns up when a household is in trouble. (Middle grade fiction is about the household more than about the community). They fix the problems, then move on.

The Blow-in Saviour trope is a benevolent outworking of the ‘walking the Earth’ trope.

EXAMPLES OF THE BLOW-IN SAVIOUR TROPE

- Into The Wild — Chris McCandless goes from place to place offering (pseudo-) wisdom and seeming to improve other people’s lives, until his philosophies turn in on himself and lead to his own downfall.

- Tinkerbell of Peter and Wendy

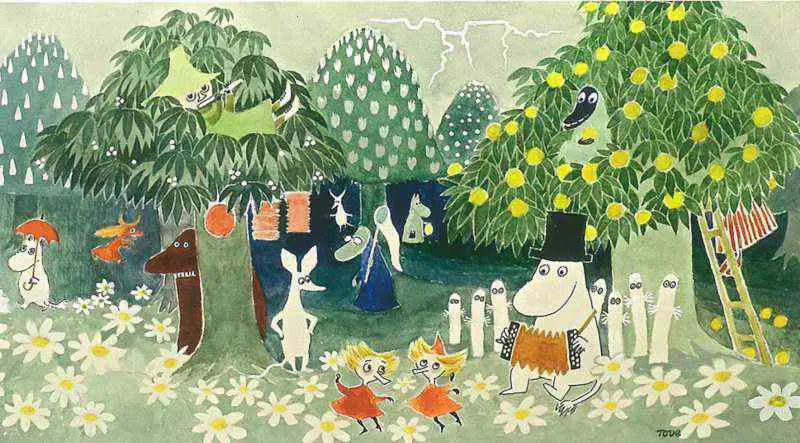

- Snufkin from The Moomins is similar. He plays a harmonica wherever he goes, distributing the joy of music.

- Crocodile Dundee (Australian film) — comedy, adventure

- Red Dog is another Australian film — in a heartwarming story, a red dog goes from place to place spreading joy.

- True Grit — anti-Western, adventure

- Amélie (film) — French comedy romance — Blow-in Saviour comedies are popular in France for some reason

- Chocolat (book and film) — drama, romance

- Good Morning, Vietnam (film) — biography, comedy, drama

- Mary Poppins (family musical based on a series of books by P.L. Travers) — children’s book — comedy, fantasy, Nanny Story

- Shane (classic Western) — about the only non-ironic Western movie made since the world wars — includes drama and romance

- Anne Of Green Gables — Anne starts off as a scattered character who causes chaos wherever she goes despite her best efforts. But her character arc turns her into a Blow-in Saviour, which starts the night she saves the Barry girl by knowing what to do for her illness. After she grows up, Anne doesn’t leave Avonlea for good, she is back and forth, and tends to win crotchety people over so long as they are basically good in the first place.

- Wanda from The Hundred Dresses by Eleanor Estes is wise and humble beyond her years. She visits a school temporarily, changes the social structure for the better, teaches kindness then moves on.

- Jack Reacher goes from town to town solving mysteries.

- Xena Warrior Princess and her sidekick Gabrielle go from place to place fighting warlords. The backstory is that Xena is atoning for her past as the worst warlord of them all.

- Superheroes have Blow-in Saviour attributes. They seem drawn to saving everyone and will travel far and wide to do so.

- Santa — the ultimate Blow-in Saviour!

- Miss Rumphius is a bit of a Blow-in Saviour character, walking from place to place spreading flower seeds, beautifying the area.

- Ray Donovan, a Hollywood ‘fixer’ who later moves to New York.

- The Straight Story — This 1999 biographical road trip story directed by David Lynch is about Alvin Straight, a man who decides to make an epic journey to see his brother and straighten things up with him before he dies. The journey to Wisconsin wouldn’t ordinarily be so epic, except he makes the eccentric decision to undertake the journey on a series of ride-on lawnmowers which keep breaking down. (We can assume he has lost his car driver’s licence due to old age). This guy meets people along the way and shares wisdom he has collected. (If you enjoy this film, see The World’s Fastest Indian.)

Related: Angelic Tropes at TV Tropes

THE BLOW-IN DASTARD TROPE

An inversion of the Blow-in Saviour trope can be found undertaking less optimistic, borderline misanthropic mythic journeys. Annie Proulx has upended the Blow-in Dastard trope in several of her stories, notably “Heart Songs” and in “Negatives“, both from the Heart Songs collection. Well-heeled outsiders enter a poor, rural community, wreak havoc then move on, only to do the same to the next town, we deduce.

In children’s literature we have Wolf Comes To Town! by Denis Manton and similar stories in which a villain goes from place to place wreaking havoc. Classic fairytales tend to end with the goodies defeating the baddies, but new re-visionings sometimes eschew the happy ending.

When Nellie Bertram joins The (American) Office cast, inserting herself as boss, she describes herself as their blow-in saviour by comparing herself to Tinkerbell (a genuine Blow-in Saviour). In doing so, she describes the Blow-in Saviour perfectly:

Jim: Yeah, that’s the thing. I don’t know if you can even give raises.

Office Quotes, Season 8, Episode 19

Nellie: Jim, have you ever heard of a character named Tinkerbell?

Jim: Yes.

Nellie: I’m Tinkerbell.

Jim: No.

Nellie: Mm-hm. I’m a magical fairy who floated into your office to bring a little bit of magic into your lives, to give you all raises.

Stanley: And we are grateful.

Nellie: But here’s the thing about Tinkerbell, Jim. Everyone has to believe in her or she doesn’t exist.

Jim: She dies.

But Nellie is full of bluff and bluster, a charlatan and a terrible boss. From the outset she is presented as a Blow-in Dastard instead. This works best when the audience understands what she is trying to do, which is why having her explain this is effective.

2. THE STATIC JOURNEY

There are two ways of getting home; and one of them is to stay there.

G.K. CHESTERTON

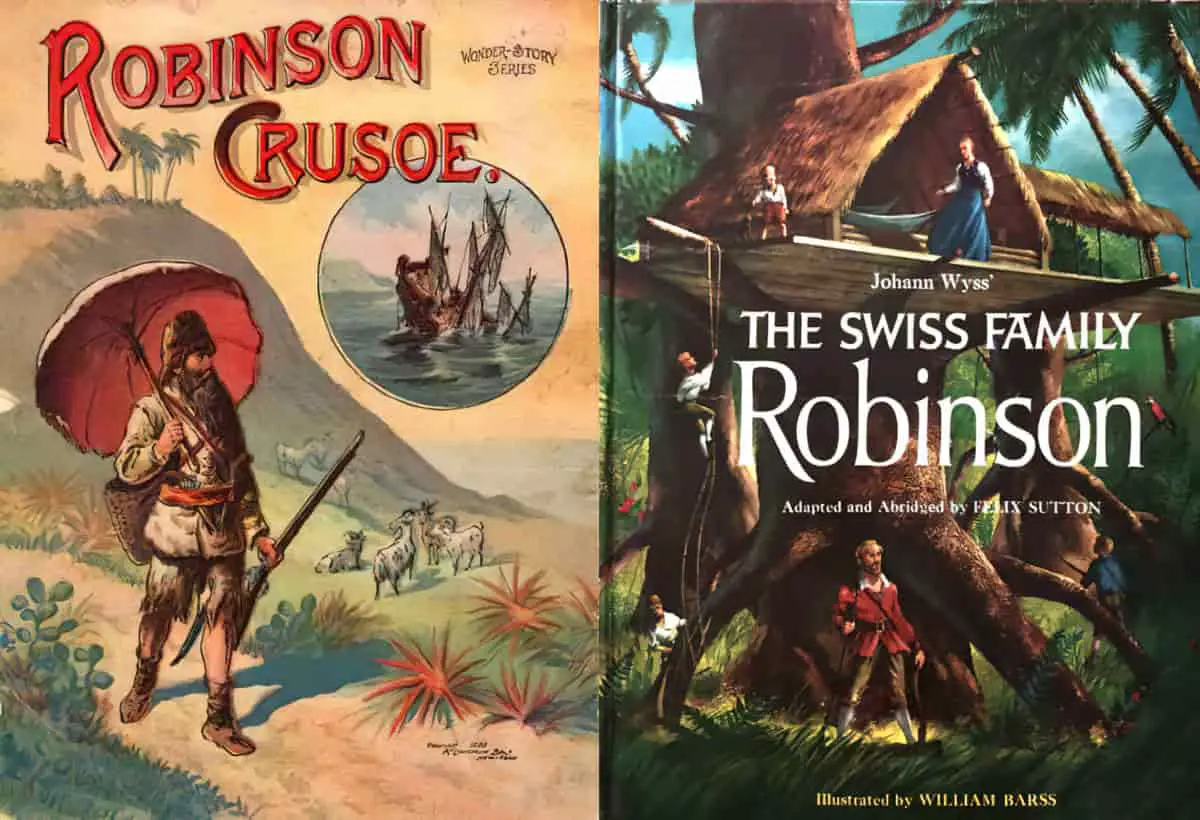

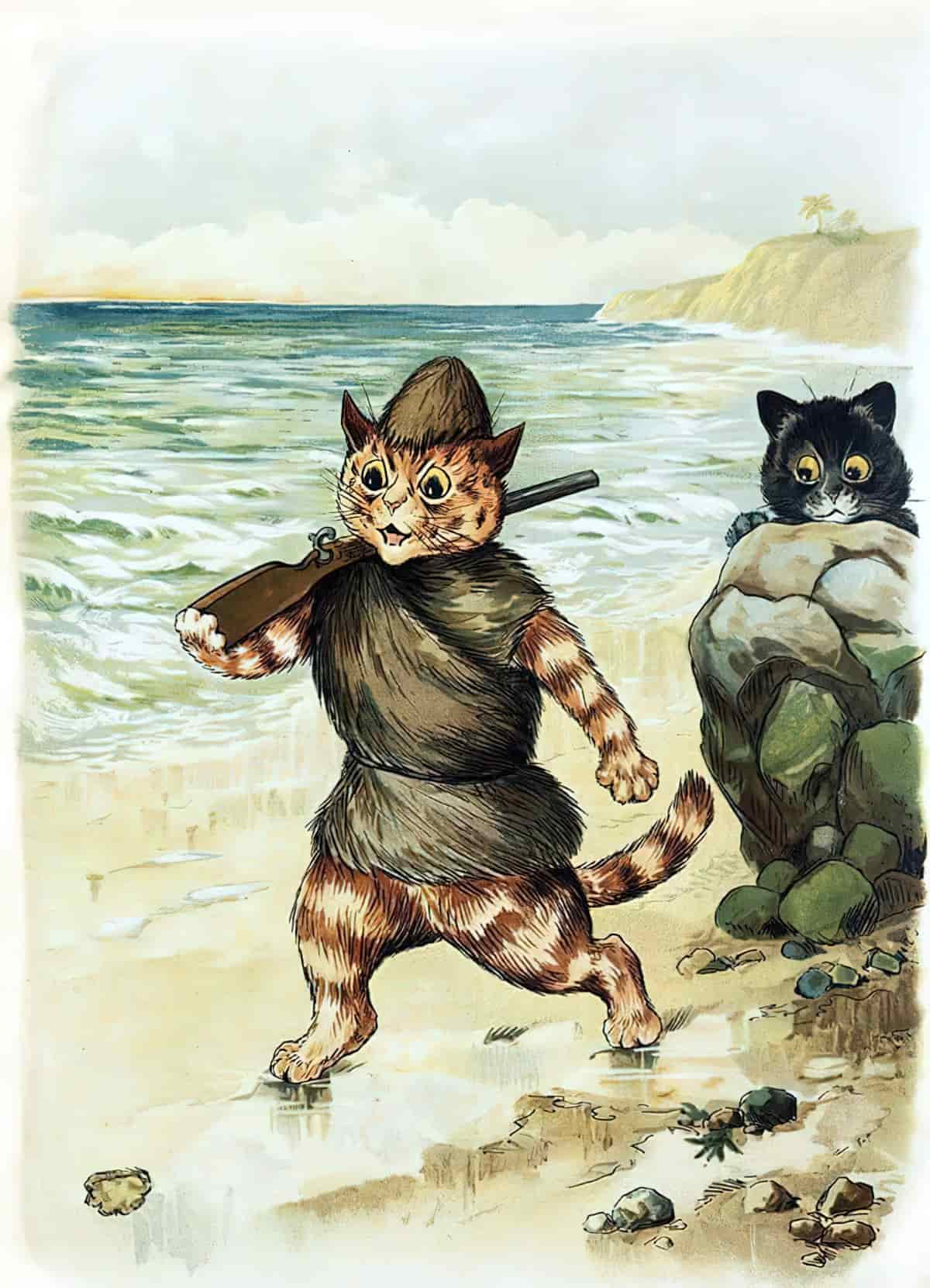

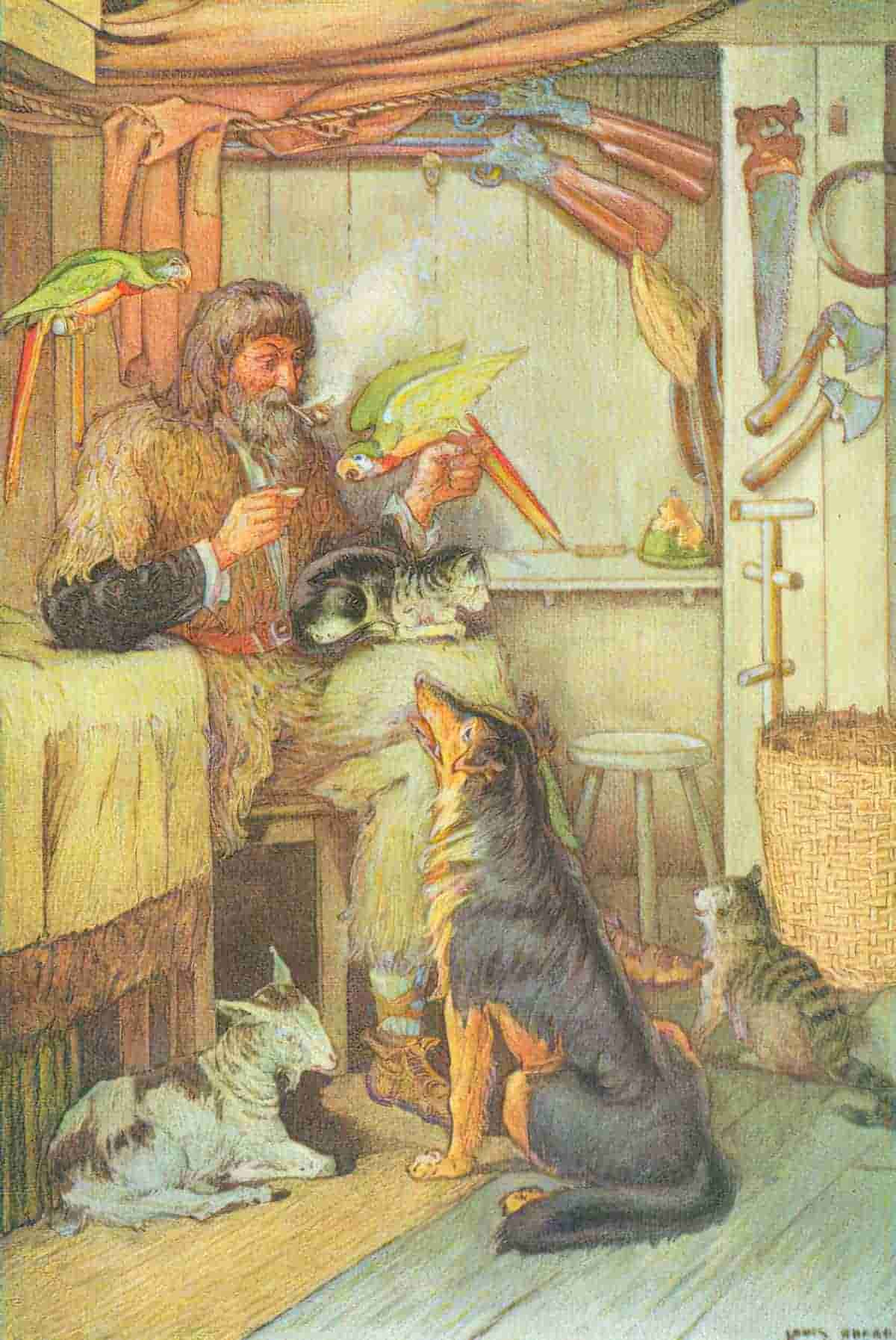

The ur-Static Journey is the Robinsonnade, a word that appeared to describe two similar novels which happened to both have ‘Robinson’ in the title: Robinson Crusoe (1719) and Swiss Family Robinson.

The fictional story of Robinson Crusoe by Daniel Defoe had a huge effect on real-world events, especially on the history of Australia. Explorer and cartographer Matthew Flinders read Robinson Crusoe as a kid and wrote in his travel memoirs that he was “induced to go to sea against the wishes of my friends from reading Robinson Crusoe“.

What made Robinson Crusoe so popular?

- A wonderful narrative voice — exciting, unhurried and conversational. Quasi-journalistic.

- It’s actually a very old story pattern, also seen in the Bible: transgression, retribution, repentance, redemption. (Youthful rebellion, successive shipwrecks, the painful lessons of isolation, Crusoe’s return home.)

- Memorably concrete images, like Friday’s footprints in the sand, Crusoe with his parrot and umbrella.

One reason for the island myth is pure escapism, of course. But this sort of myth is often not an escape from work. Once you’re on the island, characters need to work hard to live. This is like ultra-camping, or the feeling you get watching reality TV of the Doomsday Preppers variety. In Robinson Crusoe, our hero has to build shelters, fence off territories, hunt and farm. This plays into the wish fulfilment fantasy of self-sufficiency.

Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island has […] fallen out of favour with present-day readers, but any number of adventure stories, from Rudyard Kipling’s The Jungle Book to The Action Hero’s Handbook derive from it. Stevenson’s young hero, Jim Hawkins, foreshadows the plucky resourcefulness of Anthony Horowitz’s reluctant teenage spy, and Eoin Colfer’s criminal mastermind Artemis Fowl.

Why this is a golden age of children’s literature, Amanda Craig

Why are these stories so popular? Well, we love a story in which characters work for what they have. This is a dominant ideology in children’s literature, too. When characters get what they desire we like to see evidence that they deserve it. Robinson Crusoe has achieved longevity due in part to its consonance with this modern ideology that work is one of most important things humans can do. Indeed, Defoe presents work as a kind of therapy — working on mind, body and spirit. When Crusoe bakes his own bread he’s proud of his achievement. This is in line with the tale of The Little Red Hen: If you want to enjoy your bread you had better have baked it yourself.

For more on Robinson Crusoe see The Guardian, in which they count Robinson Crusoe as the second most important book in English literature.

A more recent evolution on the Robinsonnade is Huckleberry Finn and Tom Sawyer, written in the mid- to late-1800s in which the hero doesn’t actually need to go anywhere; all the action takes place at home.

In the 20th century we read school stories and holiday stories, which are also static in that the action takes place at a (boarding) school or at a holiday destination.

Around the 1960s and 70s, adventure stories started to focus less on plot and more on character. Romanticism gave way to realism. As in the best adventure stories, setting is still important.

- Betsy Byars

- Joan Phipson

- Patricia Wrightson

- Ivan Southall — the Simon Black series, considered The Australian Biggles

- Eleanor Spence

- Lilith Norman

Most recently these realistic adventure novels have evolved into what are sometimes derisively known as ‘issues novels’, especially in young adult literature, and the trend is now moving down into middle grade literature.

A more direct modern retelling of the Robinson Crusoe story is of course Castaway starring Tom Hanks. But don’t forget that any adventure story which takes place in one place is a descendent of Robinson Crusoe.

Julie of the Wolves is a young adult novel in the Robinsonnade tradition.

Reality TV shows set on islands are also part of this tradition, where contestants ‘work’ for their prizes, even if the work comprises social manipulation and flirtation.

You may already be noticing a few problems with traditional mythic stories. The third main type of myth (described below) goes some way towards modernising the form, but first, let’s take a look at the known problems.

SOME PROBLEMS WITH ODYSSEAN (AND ROBINSONNADE) MYTHIC STRUCTURE

Your soundtrack for this section: I Saved The World Today by Annie Lennox and Dave Stewart

PROBLEM ONE: UNIVERSALITY IS WORKABLE BUT PREDICTABLE

The mythic structure is certainly popular, but has been done many times before. It’s likely that the most original stories to emerge will veer away from mythic structure altogether. However, since film audiences are already conditioned for myth, such novel stories are likely to be considered ‘fringe’ and will have less money allocated to their production and marketing. Indie studios are more likely to take such risks. However, you’re more likely to see non-mythic novels than non-mythic Hollywood films for exactly this reason. Genre in novels/short stories/indie film is evolving at a faster pace and is more open to innovation.

The story of the hero and his quest, the adventure story, is always essentially the same. It is the story of Odysseus, of Jason and the Golden Fleece, of Beowulf, of Saint George, of the Knights of the Round Table, of Jack and the Beanstalk, of Robinson Crusoe, of Peter Rabbit, of James Bond, of Luke Skywalker, of Batman, of Indiana Jones, of the latest sci-fi adventure and the latest game in the computer shop. It appears in countless legends, folk tales, children’s stories and adult thrillers. It is ubiquitous. Northrop Frye has argued that the quest myth is the basic myth of all literature, deriving its meanings from the cycle of the seasons and ‘the central expression of human meanings from the cycle of the seasons and ‘the central expression of human energy [which transformed] the amorphous natural environment into the pastoral, cultivated, civilized world of human shape and meaning…the hero is the reviving power of spring and the monster and old king and outgrown forces of apathy and impotence in a symbolic winter.’ Whether we accept this or not, the centrality of the hero story in our culture is unarguable.

Margery Hourihan, Deconstructing The Hero

PROBLEM TWO: LACK OF NUANCE

Since myth tends to rely on simple distinctions between ‘good vs evil’, nuance can be sacrificed. The message that ‘good doesn’t always win out’ isn’t easily conveyed by the mythic structure.

“But to look back from the stony plain along the road which led one to that place is not at all the same thing as walking on the road; the perspective to say the very least, changes only with the journey; only when the road has, all abruptly and treacherously, and with an absoluteness that permits no argument, turned or dropped or risen is one able to see all that one could not have seen from any other place.”

James Baldwin, Go Tell It on the Mountain

PROBLEM THREE: GENDER INVERSIONS DON’T FIX LACK OF REPRESENTATION

In a female-led mythic story the heroine requires an extra step: She FIRST needs to break free of the constraints of home. (See Thelma & Louise.) This is an extra burden on writing female characters, leads to a less diverse type of storytelling featuring women, girls and gender diverse characters. After all, why should stories about women and girls base their template on stories which never included women and girls in the first instance? A good story about the female experience of the world isn’t simply a story about a boy, only with the boy switched out for a girl.

3. THE INTEROCEPTIVE MYTH

Here it is, your Moment of Zen, from The Daily Show

Interoceptive awareness basically refers to your ability to understand what emotions you’re feeling.

This new type of myth, which requires characters who are able to access their own emotions, and doesn’t require a big externalised fight for a climax. Others have used the gender binary to describe these myths, and call this type of myth the Female Myth. But I would like us to move away from this now. Though there’s truth to the observation that stories starring boys and men are more likely to contain fighting at the climax and less likely to feature characters with high-level thinking and co-operative skills, I’d like to disentangle the idea that masculinity and violence naturally go together. I’d like to see more boys the stars of these so called feminine myths. The feminine myths are about thinking, and I’d also like us to move away from the idea that women and girls are guided by emotions. (Emotions are for everyone.)

All that said, there is an obvious physiological connection between the binary mythic forms:

It could be that we’re all sick of the three act structure and that actually there is a way of telling a story that is different. And it’s just not about the big orgasm [Battle] at the end. We have multiple orgasms, that’s God’s gift to us. […] There is a theory around women’s storytelling, that it isn’t just the three act structure to get to the big bang at the end. That isn’t our biology. We like a slow burn. And it’s very rewarding. What’s wrong with 10 endings?

Gaylene Preston, New Zealand filmmaker

[Some people] think that the bases track neatly onto emotions so that holding hands is a little bit intimate and kissing more intimate and having sex the most intimate thing of all. Reality is rarely this neat or linear. Sex can be boring and impersonal, while a brush of the hand can be thrilling. One person can feel close to another from far away and the same person can have penetrative intercourse and not feel much of anything. Touch doesn’t have to be a hierarchy, and sex doesn’t have to be the only, or even the best, way of achieving intimacy.

Ace: What Asexuality Reveals About Desire, Society, and the Meaning of Sex by Angela Chen

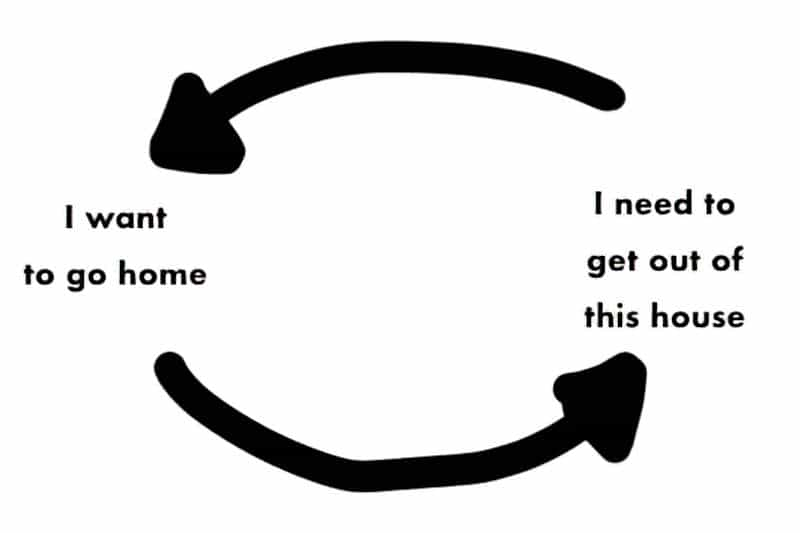

To recap, Odyssean stories and Robinsonnades are said to be of the ‘male’ type. The first involves leaving home and going on a journey to find oneself; the second focuses a bit more on character development. Throughout the corpus of children’s literature it is especially obvious — girls get to stay home (domestic stories) while boys leave the home (on adventure).

‘If you were a boy I’d say are you going to seek your fortune?’

Terry Pratchett, Equal Rites

‘Can’t girls seek their fortune?’

‘I think they’re supposed to seek a boy with a fortune.’

Now, let’s talk about the new, Interoceptive Myth.

There are few modern examples of the interoceptive mythic form, but some well-known examples include:

- Inside Out

- Frozen

- Gravity

- Coraline

- My Neighbour Totoro

- The Snowman

- Arrival

- The Paperbag Princess as an example of the big struggle-free mythic form. (Book creators have been doing it longer than Hollywood writers have.)

- Wolf In The Snow by Matthew Cordell

- The Fog by Kyo Maclear and Kenard Pak

In fact, a lot of picture books use a battle-free mythic structure. I would put Where The Wild Things Are in this category because the main character is dealing with his own emotions and the monsters can be read as imaginary. Think of any picture book which is a descendent of Where The Wild Things Are: A child feels their emotions, retreats into themselves and go through an internal kind of struggle.

- Doesn’t have all the fighting

- Or the fisticuffs type of battle at the climax

- Doesn’t necessarily involve a journey away from home, but there is some sort of long, difficult journey

- There doesn’t have to be a ‘minotaur’ (a powerful outside opponent)

- Plots are not based on outside conflict

- It draws heavily from Jungian theory.

- Interiority. The battle-free myth is an inner journey. It seems to have been around since the Second Wave feminist movement (though there may well be excellent earlier examples I don’t know about.) Either the character goes into their own heads or, as in Inside Out, there’s a whole other world in there. Imagination and fantasy are great combos for the battle-free myth form, as without the big battles and strong outside Minotaur villain we need other points of interest.

Perhaps because we don’t want kids exposed to endless fighting, children’s storytellers are moving towards stories with less violence and more emotion. Pixar has now given three examples (Inside Out and the Frozen films). They will likely give us more because these stories are really popular. In Waking Sleeping Beauty, Roberta Seelinger Trites names two books in particular: The Blue Sword by Robyn McKinley and On Fortune’s Wheel by Cynthia Voight.

THE BLUE SWORD (1982)

This novel has a lot of feminist problems, to be sure.

- The main character (Harry) basically has to become a boy and do traditionally masculine stuff. Inversion does not equal subversion.

- Harry is silenced because of how it’s plotted — she can’t speak the local fantasy language and has to rely on a dude to translate everything for her. This means he dominates conversations.

- Only four of the fifteen knights are women and they remain unnamed, so McKinley doesn’t achieve gender balance in her minor characters.

- This is ultimately a marriage plot. At the end she gets married and this is a happy ending for her.

But The Blue Sword is an important work because it was one of the first books to allow a female character a traditionally masculine mythic quest.

Seelinger Trites points out that imagery of cycles and wheels inform both texts to emphasize how Birle and Orien’s journeys are process rather than goal-oriented. This lines up with what Maria Nikolajeva has said about how seasons dominate in children’s books written for girls, since seasons are cyclical.

The journeys themselves are circular as well. In male myth forms, the hero often (though not always) ends in a different part of the world.

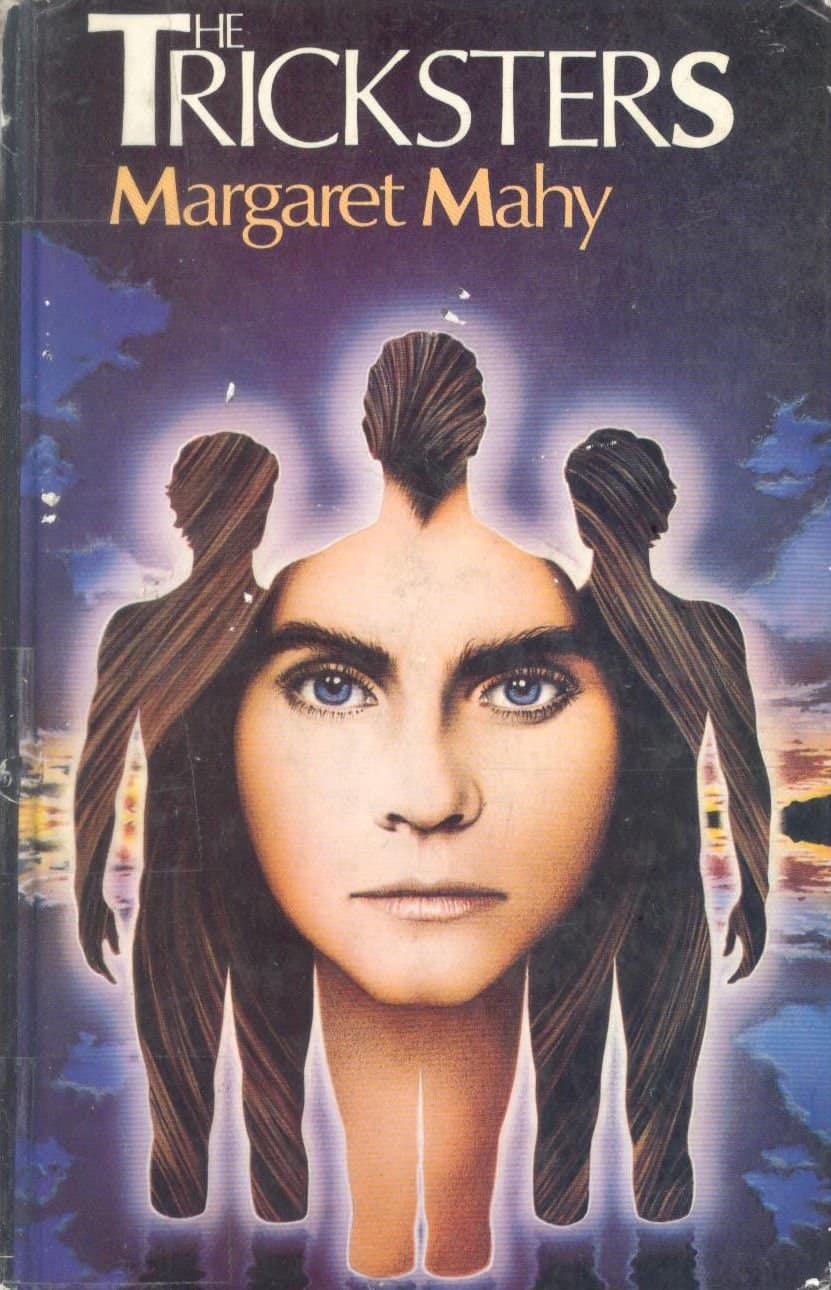

THE TRICKSTERS BY MARGARET MAHY (1986)

In this sophisticated YAL novel from 1980s New Zealand, Margaret Mahy takes a classic Greek myth and re-visions it into something feminist. To do that, she takes the ‘thread’ of the Minotaur myth and uses another of its meaning: not a literal spool of thread this time, but a ‘plot thread’. Main character Harry (alter ego Ariadne) is using her brain to work through a mystery surrounding her family.

The text of The Tricksters exemplifies the intertextual use of mythology and folklore in feminist children’s novels. It uses intertextual references to underscore its theme, but more important, when the original text oppresses females, the feminist author transforms the story, redeeming it from sexism and claiming it for feminism. Jack Zipes maintains, “Folk tales and fairy tales have always been dependent on customs, rituals and values in the particular socialisation process of a social system. They have always symbolically depicted the nature of power within a given society. Thus, they are strong indicators of the level of civilization, that is, the essential quality of a culture and social order. That the ways a culture uses folktales reflect the culture’s values seems clear. In rewriting folktales to advance feminist ideologies and to identify female subjectivity, feminist writers are both protesting the powerlessness of women inherent in our culture’s old folkways and giving voice to a new set of values: a set that allows for the princess to have power, a set that allows Sleeping Beauty to wake up not to a destiny that immerses her in her husband’s life but to a destiny that is self-defined.

Waking Sleeping Beauty by Roberta Seelinger Trites

ON FORTUNE’S WHEEL (1990)

Cynthia Voight’s novel is similar to The Blue Sword but avoids some of the traps of subversion.

- Birle goes on a quest, like Harry, though she’s not after an object in particular.

- She doesn’t give up her voice, identity or her culture when she marries.

- She starts her journey voluntarily, trying to rescue her family. (This is similar to the much later Katniss Everdeen ‘call’ to adventure.) She’s not kidnapped or anything, decisions are her own.

- She serves as the male character’s guide for a while then makes her own decision to join him on his journey in the hopes of escaping an unwise betrothal (that she made herself).

- She falls in love with her male companion and chooses to be with him.

- Birle is not setting out to destroy a foe. This is what makes it different from the male quest/myth.

- Instead, it is the process of the journey, which allows the characters’ love for each other to grow, and not the end of the journey that matters. This is the main narrative choice that separates Voight’s quest from others.

One feature of the masculine myth: the rebirth, emphasis on ‘re’. A hero has come from his mother’s womb, but he hasn’t properly disassociated himself from his mother until he undergoes a REbirth. In this way, the symbolic labyrinth (or fantasy world, or journey) is a womb, but a dangerous one. This is why in mythic fairy stories, fairies are always trying to take male babies away from their mothers, and why mothers are always clinging onto the idea that their little boys can be kings and heroes despite having been born of a woman. It probably goes without saying, but all of this is a product of a misogynistic culture.

This works slightly differently in the non-battle myth. Instead of disassociating herself from her mother, the hero of a non-battle myth (usually a heroine) might be separating herself from ‘the male culture that was modelled by her mother’.

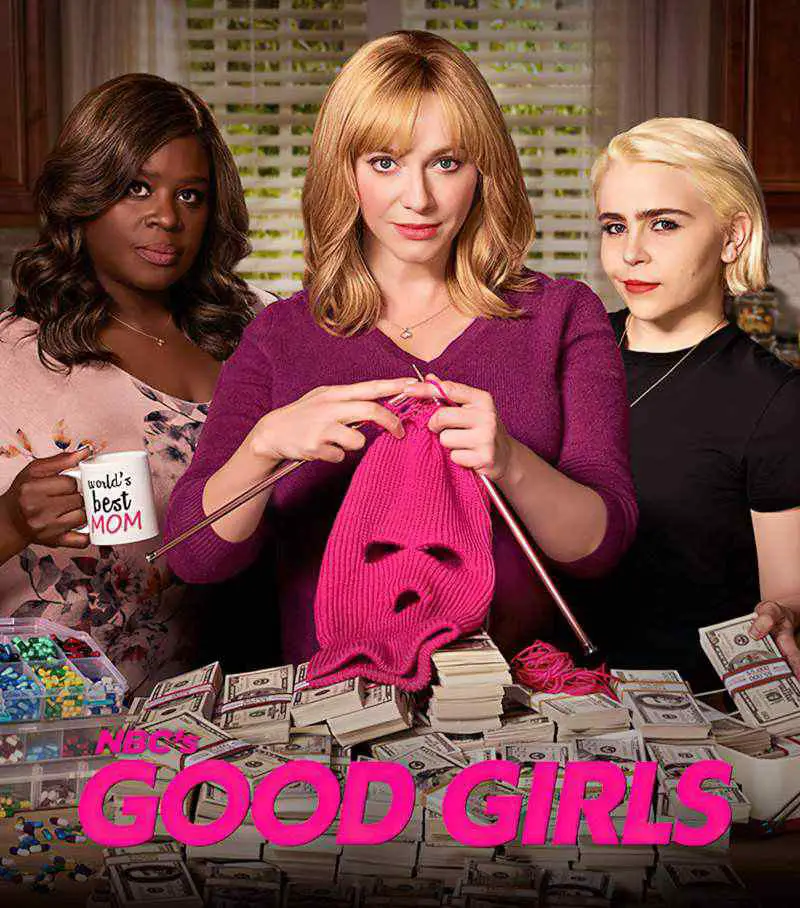

GOOD GIRLS TV SHOW

Good Girls is an interesting example of a feminised traditional story. Anyone who has seen Breaking Bad will see that Good Girls is ‘Breaking Bad, but for moms’. (Breaking Bad is a brilliant show but has clear gender problems, not all of which can be blamed on a misogynistic audience.)

How is Good Girls different from Breaking Bad? Well, first there’s the tone. Good Girls is far more cosy and, as a result, far less tense. Like Walt and Jessie, they kidnap someone early in the show. Whereas Walt keeps his captive in the basement, the moms keep theirs outside in the shed. But at no point do we get the sense that the mothers’ lives are in danger.

There’s violence, all right. But instead of a real gun, these moms try to win a battle using an actual toy gun. (The scene is a pastiche from the famous Thelma & Louise inciting incident.) A subsequent gun scene turns into dark comedy when another mom means only to threaten, but ends up shooting a guy in the foot. Drama happens in and around the homes.

When the moms make enemies, they treat these enemies differently from Walter White. These moms empathise with their opponents, because they are all having the same problems: living as women under patriarchy, never having enough money to care for their families. Instead of killing them in explosions and with poison, the mothers think and feel their way around their opponents.

DIFFERENCES BETWEEN ‘MALE’ AND ‘FEMALE’ MYTH FORMS (exteroceptiVE VS INTERCEPTIVE)

Some major differences between the ‘male’ and ‘female’ myth forms are described by Elizabeth Lyon in her book Manuscript Makeover, in which she picks the highlights from an earlier feminist book The Heroine’s Journey by Maureen Murdock, which now feels like a very 90s form of feminism.

| MALE MYTH: THE OUTER QUEST | FEMALE MYTH: THE INNER QUEST |

| The Hero is in his familiar Ordinary World when a serious event introduces a problem that is his Call To Adventure. | A life changing event compels a woman to go on a quest to find her own identity, separate from the one she assimilated from the male culture that was modelled by her mother. |

| He refuses the Call because it will mean change, challenge, Separation from the known and familiar, and Departure from home. It may even mean risking his life. He also doesn’t know if he is capable of the task. | At first she adopts so-called male behaviours, thinking that she has denied aggressiveness in the past and that is what she needs. |

| A Mentor assures him that he can do it, must do it, and is the only one who can succeed. | This belief leads her into the world of men, often also growing closer to her father. |

| Emboldened and committed, the Hero departs. He Crosses the Threshold into the Special World, which is alien compared to his Ordinary World. | She often achieves success in the work world as she perfects her Animus, the assertive competitive, perfectionist, and male-identified side of her personality. |

| He quickly learns the rules, encounters Allies and Enemies, and begins his Descent deep into the Special World, the territory of those who oppose him and where he’ll find the solution to the problem. | At the same time, she challenges, rejects and even rebukes the beliefs in inferiority, dependency, and romantic love that she now sees as cultural indoctrination of women. |

| As he continues on the Road of Tests and Trials, the obstacles grow more formidable. He reaches the Approach to the Inner Cave, knowing that at its heart will be the Supreme Ordeal. In the innermost cave, he encounters the biggest obstacles and threats to success. If he overcomes these final challenges, he will have claim to the Reward: He’ll achieve the goal that resolves the problem that set him on his journey. | She may blame her mother and distance herself from her. |

| After he succeeds (or fails), he Refuses the Call to return home, instead emerging from the cave to regale in his glory or to lick his wounds. | But when success in the male world also leaves her feeling hollow she no longer feels close to her father or male mentors. She feels betrayed by everyone and everything she has known and believes, including God as a male-defined creation of the culture. |

| Believing his quest is over and he can at last begin his Return home, he is confronted with one last obstacle, the Ultimate Test. Whether or not he reaches his story goal, if he summons all that he has learned, and releases or heals a wound he was afflicted with in his past, he will let his old self die to be reborn into a new, freer self. | Alone, “spiritually arid”, the woman begins her turn inward in search of her unique self. She examines her unique experiences and searches for memories that seem to reflect pieces of a lost but authentic self. However long this period lasts, it often involves shedding any accoutrements of what the patriarchal culture deems appropriate and desirable: female dress, manners and friends. Yet she yearns for an end to the grief and emptiness. She fears she may die without finding her true self and a chance to pursue dreams that she discovers within her. |

| This is his emotional passage, his Initiation. Death and Rebirth allow him to overcome this final confrontation (unless the story is a tragedy, and then he clings to his old ways, shortcomings, and the emotional wound.) | Little by little, or all at once, she finds that connection, and the courage to receive the archetypal power of the Feminine. She integrates it in her own way. She begins to express her unique and now known self. Now she can also express, as needed, nurturing, relatedness and receptivity. These are the positive qualities of the Feminine. |

| She reconnects with her mother or with the archetype of the Mother. If the relationship with her earthly mother permits it, she seeks to heal the former breach. | |

| Instead of rejecting all the Masculine qualities, she integrates the side of herself that also holds the power of the positive Masculine archetype. | |

| At last he can Return with the Elixir, perhaps a treasure, but the true reward is being a new, transformed individual, a Master of Two Worlds, an integrated person with wisdom to share, in the form of the theme reflected by his journey. | Finally, she ends her duality, the split of her self and cultural beliefs about the Feminine and Masculine. She ends the misery of beliefs and behaviours not in harmony with her discovered self. She emerges into her new world and selects her new life as an integrated, renewed and healed person. |

“Some women tend naturally to be Warriors and Seekers, and some men to be Caregivers and Lovers in spite of their cultural conditioning. The point is for both to take their journeys in such a way as to find their own way to be male or female, and eventually to achieve a positive kind of androgyny, which is not at all about unisex, neutered behavior, but is about gaining the gifts both gender energies and experiences have to offer us.”

Carol S. Pearson, Awakening the Heroes Within: Twelve Archetypes to Help Us Find Ourselves and Transform Our World

In order to work out whether a mythic story is ‘male’ or ‘female’, don’t look at the gender expression of the hero. Men and boys can star in interoceptive myths while women and girls can star in the traditional ‘male’ myth, and often do (a la the Strong Female Character archetype).

A text may be intended for women and may be about women, but it may still have a masculine point of view because the beliefs in the hypothetical narrator point of view about women are masculine.

Ismay Barwell, Feminist perspectives and narrative points of view, 1993

Oprah’s book club picks are often examples of the interoceptive myth.

Since the reader of this kind of interoceptive myth form is asked to identify with a character battling what is essentially the patriarchy, it’s not surprising that some men (one of whom even refused to appear on Oprah’s book club…) will be turned off by a Oprah’s book club sticker. It is true of many things in life as it is in reading — women are expected to understand and sympathise with the male experience but not vice versa. Many men simply cannot understand what such a battle would feel like, or what it even entails.

Where are all the female creation myths?

The female body follows the lunar cycle, which is closely associated with the idea of death and rebirth (waning and waxing moon). The cardinal function of the female body is reproduction. The big battle-free myths, describing female initiation, are aimed at repetition, rebirth, the eternal life cycle. Actually, very few genuine big battle-free myths exist in written—male, civilised, “symbolic” (Lacan)—form, due to many reasons. Connected with essential life mysteries such as menstruation and birth (both involving bloody), big battle-free myths are more secret and sacred than male myths. They have mostly existed in oral form, as esoteric rituals. In Western civilisation, they have been suppressed and muted by the dominant male culture. We can only discover traces and remnants of them, in the figures of the *Progenitrix, the witch, the **chthonic goddess.

*Progenitrix = A female progenitor, a foremother, any of a person’s direct female ancestors (ancestresses).

**Chthonic = relating to or inhabiting the underworld

Maria Nikolajeva, From Mythic to Linear: Time in children’s literature

How is story different in a non-patriarchal society? I say ‘non-patriarchal’ rather than ‘matriarchal’ because there is no real evidence to suggest that before patriarchy was matriarchy. In fact, evidence points to a flatter social system altogether.

I have written previously about how the mythic form as we know it — the form which dominates Hollywood blockbusters even today — is a strongly male-centric story.

The very recent Female Myth form aside, the Male Myth form — the one we’re all veeery familiar with — has been dominant for the last 3000 years.

3000 years sounds like forever, but humans have been around longer than that. We’ve been telling stories for longer than that. What did the original big battle-free myth look like? 20th Century feminist Marilyn French offers some insight in the first chapter of her 1985 book Beyond Power: On Women, Men and Morals:

THE VERY OLD HISTORY OF THE MYTH

- Most of the metal, human-shaped ornaments found from ancient times are figures of women. There are men too, but most are women. Like, not just 51% women — the overwhelmingly majority are obviously female. Some of these figurines date back to 9500BCE. (Metallurgy wasn’t widespread back then but it was still practised in certain areas.) This suggests that women were more visible in these very old societies, only later wiped from the history books.

- These female-shaped figurines last right up almost until the Christian era.

- Many researchers believe these figurines were significant when it comes to worship. Old cultures worshipped regeneration and fertility. It made sense to them that everything came from the female, not the male. Other symbols of regeneration (apart from the female body) included: eggs, butterflies and the aurochs (the wild ox of Europe).

- The mother goddess was not only in charge of birth but also of death. (“I brought you into this world, and I can take you out!” Anyone?) She was also mistress of the animals. So she could also be symbolised by dogs and pigs and other animals vital to human survival. She was also seen in the form of a bird. (We have to remember that all early art was symbolic.)

- This view of the world — one ruled by a goddess — wasn’t limited to a small area. It was all over the show. Like, China, the Middle East, Mesoamerica, and in Europe from the far north to the Mediterranean and in Middle Europe as well. For more on this look up work done by Marija Gimbutas.

- Around the 4th or 5th millennia BCE cultures started to make more and more male figures alongside the female ones and they started to become elaborately dressed.

- Other changes: The female figurines of the Paleolithic era were corpulent, but after the agricultural era was ushered in she was slimmed right down. She became flanked by domesticated rather than wild animals (dogs, bulls and he-goats). The goddess was also often associated with the bear. Bears are considered particularly good mothers, and may have had a big impact on Europeans.

- Funnily enough (for anyone who’s read the Old Testament), women were also associated with snakes. This is because snakes lose their skins and ‘regenerate’. There are a whole bunch of other symbols to do with women too, like chickens, which puts me in mind of Baba Yaga. (The bear puts me in mind of Pixar’s Brave — see, we’re still making use of these ancient symbols today.) We even see oversized depictions of female genitalia. From here things start to go downhill for women.

- From the beginning of what’s known as ‘the Classical period’ (300CE to 900CE) women still appear as sculptures, but only as goddesses or priestesses. After that, right up to the 14th century, depictions of women — anywhere, in any form — basically cease. When we do see women, like in some Aztec art, women are huge, ugly and terrifying.

- Between 1500 and 1900 there was a lot of religious art: Madonnas and Annunciations coexisted with many crucifixions. There were many, many portraits of saints and Church Fathers and gory martrydoms. In secular art there were condottieres on horseback, gorgeous naked Davids, kings and ministers in ermine and gold, wizened-looking Protestant merchants with their wives and possessions spread around them.

- Today, of course, women have reappeared in art but we continue to be depicted in a much more heavily sexualised way. We are back in the story, but even in children’s literature there are 3 male characters for every female. (See the work of Janet McCabe if you need to know someone counted.)

What the hell happened?

- First – don’t get the wrong idea. Those ancient figures of corpulent women didn’t necessarily mean everyone was living in a matriarchy. All that means is that people valued fertility of all kinds above all else. People lived very close to the land, and had not yet begun agriculture. Men just didn’t seem as important in that kind of society. Maybe it’s because early societies didn’t even know that men were necessary for reproduction? It’s just as likely that they did know — I mean, we know now that both parties are equally important to human life but we still have a gender hierarchy. The male’s role in Paleolithic and early Neolithic society simply wasn’t considered as important as it is now.

- Then agriculture happened. Those central ideas of fertility, regeneration and a sense of humans as integrally connected with nature… dissipated.

- Agriculture lead to bigger populations.

- Bigger populations lead to more complicated social systems. It’s interesting and sad that today, our definition of an ‘advanced society’ is one with an established hierarchy, between men and women, between the very rich and the very poor.

- With agriculture humans started to use coerced animal labour. For examples, mules were roped in to till our fields for us. This lead to humans pulling away from nature. We no longer saw ourselves as part of nature, but in opposition to it.

- And when I say ‘we’, I mean men. Men considered women, like their mules, to continue to be a part of that ‘civilization/nature’ dichotomy. It was men and men alone who were elevated to this special place, holier than everyone and everything else. For millennia, women had been considered goddesses of regeneration, so they couldn’t just jump ship away from nature with the men, right? We see this attitude clearly exemplified in works such as the Holy Bible, in which we are told that God made the Earth and the animals for the express use of humans (addressing mainly men at the time).

- Don’t forget that before men started to use mules to till the fields, this was work which had been done by women. Even without the mules, agriculture requires male strength. Men are in charge of all areas of food production now, not just the hunting. Men control the food source. They are therefore basically in charge of who lives and who dies. It used to be the other way around.

- It is not clear to anyone exactly how it happened, but there are plenty of clues right there. Communities started warring with each other and the status of women fell. Fell so much that women were now owned as chattels, alongside farm animals. Men owned women until very recently, and women are still fighting for equal status. See this Timeline of Women’s Rights for more on that. Most recently the fight to be in charge of one’s own reproduction is one of the main feminist issues.

- Joseph Campbell has pointed out that this change in human society can be seen in how (and who) humans worship: Campbell divides his study of creation myths into four stages: in the first, the world is created by a goddess alone; in the second, the goddess is allied with a consort and the efforts of the pair lead to creation. Next, a male creates the world using the body of a goddess in some way; and finally, a male god alone creates it. For an example of that evolution take a close look at the Greek myths (some of the best studied mythologies in the world) and you’ll see the evolution from Ge (Earth) to Zeus. At one time Hera was the primary goddess and Zeus becomes powerful only by marrying her. Take a look at Athene — at one point she is born from the head of Zeus. (For some reason it makes more sense to be born from the head of a man than from the vagina of a woman.)

So, was this some kind of retribution? Did men get sick of living in a matriarchy and decide that men were in charge now?

No. First of all, there is no evidence that humankind lived in a matriarchy. There is no evidence that the Mosuo of today are representative of how most of the world ran way back when. Men have about twice the upper body strength of women and women, during pregnancy and childbirth (most of a woman’s life without contraception) are reliant upon men for survival and protection. There is no good reason to think that — goddess worship aside — women were ever hierarchically above men.

SOCIAL CHARTER AND TRANSFORMING MYTHS

Marilyn French makes the distinction between ‘social charter myths’ and ‘transforming myths’.

WHAT IS A SOCIAL CHARTER MYTH?

‘(Social) charter myth’ is a term used to interpret myths which validate or justify power structures. Any myth that seems to confirm patriarchal or establishment ideologies is probably a “charter myth”. For example when Virgil arranged events in the Aeneid to validate the Julio-Claudians by directly connecting them to Romulus and Remus.

A ‘transforming myth’ is also known as a ‘shapeshifting myth’.

As French explains, one of these mythic forms has been worse for women than the other:

Social charter myths implicitly ascribe power to women, if only in the past. They can be read as suggesting that the sexes were once equal, or that women once dominated men. Myths transforming or diminishing female figures like Hera elide such suggestions. Instead, they omit the past and transform the character of the female into something venomous, ugly, dark, mysteriously threatening. By erasing any reference to an earlier power or power struggle they make the hostility of these female figures appear unmotivated, a given. Social charter myths at least acknowledge intersexual conflict. Transforming myths do not acknowledge intersexual conflict. Transforming myths do not — thus the evil power of females appears to be biological, natural. Such a procedure penetrates the moral realm and affects an entire society’s view of women.

Marilyn French

Finally, a fourth type of myth, which isn’t really a myth but a reaction to it.

4. THE ANTI-MYTH

What makes a story an ‘anti-myth’? Basically, it’s a subversion.

- Whereas the heroes of myths have almost superhuman powers, heroes in anti-myths have real human shortcomings. See Northrop Frye.

- In an anti-myth the delineations between good and bad are blurred. The heroes are morally flawed, if not downright anti-heroes. Anti-heroes do not serve as models for the audience.

- Myths tend to take place on roads and rivers, but the anti-myth might have the characters take a journey to nowhere significant, or nowhere particularly different from before, a la Lonesome Dove. (The typical setting of typical dime Western novels was a lush river setting.)

- Whereas heroes of myths have a self- and public- anagnorisis, or self-revelation, heroes of anti-myths don’t really change a la Don Draper of Mad Men. In myths the character arc is huge; in the anti-myth, there may be no real arc. In a ‘mock-myth’, the main character doesn’t learn anything once returning home. (e.g. Ulysses by James Joyce, a take on The Odyssey.)

- If main characters of traditional myths win because they are essentially ‘good’, the main characters of anti-myths can lose despite their goodness, because shlt happens.

- Whereas myths focus on psychological states of the heroes, anti-myths focus on moral dilemmas.

- Whereas heroes of myths tend to be separate identities, main characters of anti-myths can be represented by ensemble characters, with each character representing a different aspect of self. (Winnie-the-Pooh, Sisterhood of the Travelling Pants)

- Whereas myth stories are circular home-away-home structured stories, anti-myths can take on a variety of different forms.

FURTHER READING

- Young Adult Fiction Uses Myths To Keep Traditional Storytelling Alive from NPR (and also because traditional mythic form is still a successful way to satisfy an audience).

- Using Maureen Murdoch’s work, and anything else she could find on the topic, Kim Hudson has crafted a theory of the interoceptive mythic form but calls it The Virgin’s Promise. I’m yet to read this one, but Melanie Marttila summarises the main parts of the theory.

- On BBC Woman’s Hour (before it went full transphobic) there is an interview with a woman who spends part of the year living in the Kingdom of Women in China. This is the only matrilineal culture in the world. It’s difficult to imagine what such a culture looks like, but we are told to ‘flip everything’. The men are revered, but as studs and heavy lifted. There is a hierarchy but the women in a matrilineal society seem to treat their men better than men treat their women in a patriarchy.

- For more on this Kingdom of Women, look for the Mosuo.

- The Hero With A Thousand Faces by Joseph Campbell

- From Mythic to Linear: Time in children’s literature by Maria Nikolajeva

COURTING THE WILD TWIN

Today I interview Martin Shaw. In Shaw’s new book, Courting the Wild Twin (Chelsea Green Publishing, 2020), he writes, “Here’s a secret I don’t share very often. Myths are not only to do with a long time ago. They have a promiscuous, curious, weirdly up-to-date quality. They can’t help but grapple their way into what happened on the way to work this morning, that video that appalled you on YouTube. Well, they are meant to; if they didn’t they would have been forgotten centuries ago.” In our interview, Shaw invites us to consider the power of myth to guide us not only toward new ways of seeing our current moment—one in which we’re witnessing an unprecedented global pandemic—but also new ways of seeing itself. For Shaw, a mythologist who’s designed courses at Stanford University and who directs the Westcountry School of Myth in the U.K, myths reveal unseen possibilities in our own lives and overlooked chances to reunite with our natural world. The old stories can lead us forward if only we learn how to hear them. Shaw shows us what it might mean to listen deeply and profoundly, with our minds, yes, but also with our souls, our spirits, our very bones.

New Books Network