“The Three Strangers” is a short story by Thomas Hardy, published as a serial in 1883. The story is set in 1820s pastoral England and is one of Hardy’s ‘Wessex Tales’.

SETTING OF “THE THREE STRANGERS”

Reading this story now, nigh on 200 years after it’s set, the setting of “The Three Strangers” feels almost mythical.

This is partly achieved by language no longer in common use:

- grassy and furzy downs

- coombs

Then there’s the reference to an actual mythical/legendary person: Nebuchadrezzar the second lived 630–562 BC. He was the Chaldean king of Babylon from 605 until his death. I don’t know enough about the Bible to infer meaning. But others have looked deep into it:

References to Timon, Nebuchadnezzar, and Belshazzar are made not only because these are figures from the distant past but also because their abuses of power can be compared to that of the hangman, whose every action is lawful but derived from an inhumane system of justice.

The Victorian Web, quoting a scholar named Brady.

Other, smaller things make this story feel old. For example, the description of ‘an elderly engaged man of fifty or upward’. Back then, 50 was elderly! Now it’s ‘middle aged’. Likewise, a ‘man of seventeen’ would today be a boy.

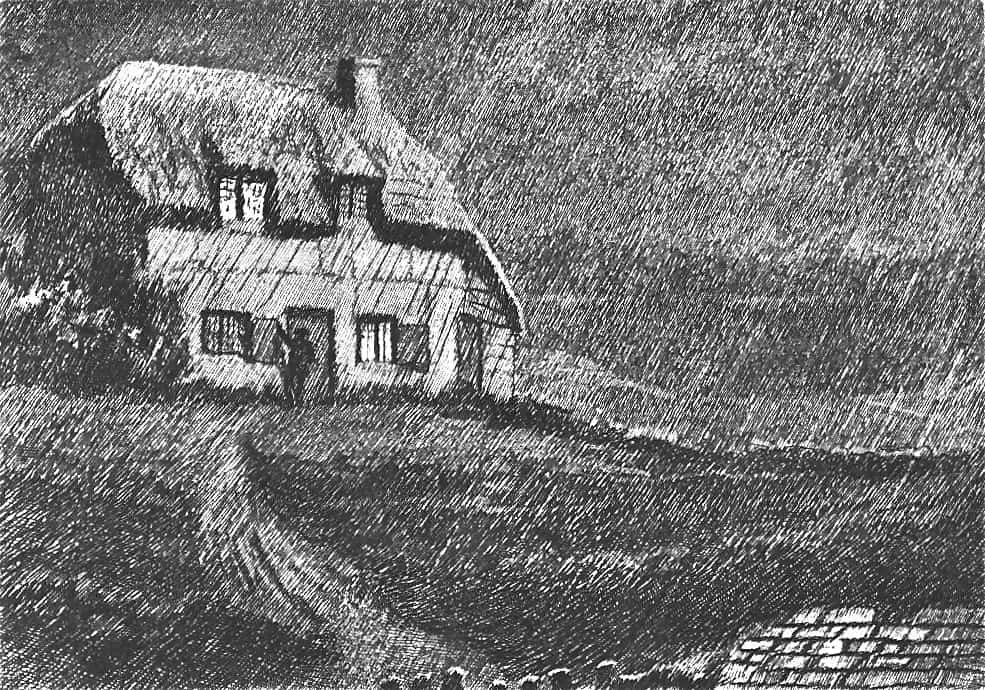

The illustrations below are not for this story. They happen to be by a Scottish illustrator called Robert Bryden (Ayrshire) for a book of poems by Robbie Burns published in the 1700s. However, when I saw these images, I thought of this short story by Thomas Hardy — people gathering in front of a fire. The details are different but the ambience probably the same.

WEATHER

Then there’s the ominous weather conditions, perfect for a horror setting:

Five miles of irregular upland, during the long inimical seasons, with their sleets, snows, rains, and mists

The ominousness of the rain is tempered by detail which describes the necessity of rain:

the grand difficulty of housekeeping was an insufficiency of water; and a casual rainfall was utilised by turning out, as catchers, every utensil that the house contained.

(We do the same at our Australian house, though we have four tanks, gutters and gutter guard for the purpose of collecting and storing rainwater for domestic use.)

TIME

The night of March 28, 182-, was precisely one of the nights that were wont to call forth these expressions of commiseration.

As Edgar Allen Poe does in “The Murders in the Rue Morgue”, Hardy omits the final digit off the exact year this was supposed to have happened. I wondered why Poe did this when everything else about the setting in the Rue Morgue story was so specific. Perhaps doing so was a writing convention of the late 19th century.

ISLAND SYMBOLISM

Though this story does not take place on an actual island, writers sometimes make use of island symbolism when describing remote buildings on land. Stephen Crane also did this in his short story “The Blue Hotel”.

MOON SYMBOLISM

It was nearly the time of full moon, and on this account, though the sky was lined with a uniform sheet of dripping cloud, ordinary objects out of doors were readily visible.

At this time in history, people really did believe that eerie things happened at full-moon — that people turned into werewolves, or that the moon could turn you mad. An ambulance driver friend has told me that, even today, full moons tend to reveal mental illness, resulting in more ambulance call-outs during a full-moon. I asked her why that is but she has no idea. I’m not even sure it’s statistically fact, but the perception still exists.

WHAT HAPPENS IN “THE THREE STRANGERS”

ESTABLISHMENT OF SETTING

“The Three Strangers” opens with a wide angle view of the local area, written in the continuous, then switches to the singulative with:

The night of March 28, 182-, was precisely one of the nights that were wont to call forth these expressions of commiseration.

DESCRIPTION OF A CHRISTENING PARTY

A group of neighbours meet up at the shepherd’s house to celebrate a birth and a christening. It is pouring down with rain outside. (I also learned the original meaning of ‘eavesdroppings’ — literally, water which drops off the eaves and onto the ground, possibly down the wall. Before someone invented guttering, I suppose.)

INCITING INCIDENT: ARRIVAL OF A DARK STRANGER

A dark stranger turns up and asks to seek refuge inside. The shepherd welcomes him in. The stranger accepts mead and dries himself by the chimney.

THEN ANOTHER ONE

The second stranger turns up. He starts drinking a lot and Mrs Fennel isn’t comfortable with him in the house. When they ask him what he does for a living, he replies in rhyme. They deduce he’s an executioner, come to hang the local sheep thief.

AND ANOTHER!

Then a third stranger turns up, this time short and blonde rather than tallish, gaunt and dark. (Utilising the age-old storytelling technique of Rule of Three.) But he won’t come in. He’s terrified by the sight of people in the room. He closes the door and runs away.

THINGS GET AWKWARD

The characters stand around the ominous gray stranger in the centre of the room and someone chants as if trying to get rid of the devil. Then a gun goes off in the distance, which they know to be fired whenever a prisoner escapes from the nearby town of Casterbridge, where there is a prison.

AHA! (WRONG CONCLUSION)

They deduce that the terrified man was the sheep thief, and that he fled because he recognised his own executioner. The firing of the alarm gun continues at intervals.

DO YOUR JOB, MAN!

A fifty-year-old guest advises the executioner to pursue the man, since that is his job after all. But the executioner says he needs to go home first and retrieve his staff. He insists he needs a staff as a weapon to hit his prisoner.

IF YOU WANT A JOB DONE PROPERLY, DO IT YOURSELF.

The rest of the men decide to take it upon themselves to catch the man. So they gather pitchforks and planks of wood (staves) as weapons, light lanterns and go after him. The women stay in the house and comfort the christened baby, who has been woken up.

MEANWHILE, THE WOMEN…

The women vacate the room where the food is. The stranger who was sitting by the chimney turns back and re-enters the property. He eats some of the cake. He drinks more mead. Then he is joined by the stranger in cinder-gray. After eating and drinking their fill, the two strangers go their separate ways.

BACK TO THE MEN

The men out hunting for the so-called escaped prisoner realise the executioner is no longer with them and aren’t sure what to do next. They’re having trouble navigating the land in the darkness, with its unexpected rubble and hollows.

GOTCHA!

The men eventually find the stranger they were pursuing, hiding near the trunk of an ash tree. In comical fashion (for the reader) the men confront the stranger with words they’d have heard constables say. “Your money or your life!”

ARREST

The stranger allows himself to be arrested without fuss. The man take him back to the shepherd’s cottage. They arrive back at 11 o’clock. There they find two officers from the jail and a magistrate.

HIDING IN PLAIN SIGHT!

The constable tells them they’ve caught the escapee. But the officials don’t recognise him. It is revealed that the man they’re after is the gaunt one with an unmistakable bass voice — the man in the chimney corner.

THINGS GET FAMILIAL

The third stranger reveals that the condemned man is his own brother. He has come to bid him farewell. He was caught out by darkness falling and knocked on the door, shocked to see his own brother escaped from jail.

BACKSTORY OF THE CONVICT

They ask for more information about the convict. The brother reveals that he is a watch-and-clock maker, when the man himself described himself as a wheelwright. The younger brother says ‘The wheels of clocks and watches he meant, no doubt’.

THE NEXT DAY…

By the following morning, general local opinion has shifted even more in favour of the sheep thief, now for his daring escape as well as for the circumstances which led him to steal the sheep in the first place. So when they go out looking for him, they don’t look very hard. And when they do see him, they let him go.

ESCAPE TO AUSTRALIA (I PRESUME)

The man was never found, perhaps escaped across the seas. The characters in this story are long since dead and the baby is now an old woman. The story has now become folklore in the local area.

CAST OF CHARACTERS

Hardy begins by setting up a cast of characters. He basically goes around the party and describes them.

Charley Jake

Described as a hedge-carpenter. What the Sam hell is a hedge carpenter? I tried looking it up online and was directed back to Hardy’s story. It seems to be specific to this story. Is it a man whose job it is to keep hedges trimmed? The word is also used in a 1905 story (in Chatterbox) and I deduce from context that a hedge-carpenter is a low-respect trade, whatever it is. Below that of a wood worker, anyhow. “‘My fingers be as full of thorns as an old pin-cushion is of pins.’”

Elija New

Parish clerk, booming voice, plays the serpent a bass wind instrument, descended from the cornet)

John Pitcher

neighbouring dairyman, the shepherd’s father-in-law

Shepherd Fennel

Master of the house where the party is being held. Married a dairyman’s daughter and into this property, Higher Crowstairs.

Mrs. Shepherd Fennel

Sensibly frugal. Keeps control of her own inherited money for their future family. This probably sounded unfair to men of the time, but seems forward thinkingly feminist to my modern ears.

The fiddler

a boy of those parts, about twelve years of age, who had a wonderful dexterity in jigs and reels, though his fingers were so small and short as to necessitate a constant shifting for the high notes

Engaged man of fifty

We must use our imagination.

The man in the chimney corner

A wheelwright (a person who makes or repairs wooden wheels). If you’re wondering what a ‘chimney corner’ is, it’s the cosy warm space between the fireplace and the wall.

Oliver Giles

A man of seventeen, enamoured of his partner, a fair girl of thirty-three rolling years. Has a lot of money at his disposal. (Today we’d likely say a ‘boy’ of seventeen’ or a ‘young man’ of seventeen. Kids had to grow up fast back then.)

The Strangers

Hardy makes use of The Rule of Three in Storytelling.

Stranger number one

He might have been about forty years of age. This makes him a generation older than Mrs Fennel though his accent tells her he comes from her parts.

He appeared tall, but…this was chiefly owing to his gauntness, and that he was not more than five-feet-eight or nine. Notwithstanding the regularity of his tread, there was caution in it, as in that of one who mentally feels his way; and despite the fact that it was not a black coat nor a dark garment of any sort that he wore, there was something about him which suggested that he naturally belonged to the black-coated tribes of men. His clothes were of fustian, and his boots hobnailed, yet in his progress he showed not the mud-accustomed bearing of hobnailed and fustianed peasantry.

Fustian: thick, hard-wearing twilled cloth with a short nap, usually dyed in dark colours

Stranger number two

The second member of the Three Strangers was dark in complexion and not unprepossessing as to feature. His hat, which for a moment he did not remove, hung low over his eyes, without concealing that they were large, open, and determined, moving with a flash rather than a glance. His shoes are cracked.

He tells the party he’s fallen on rough times lately. Then he makes the most of his hosts’ generosity and asks for tobacco, then pipe to smoke it in, as well as all the paraphernalia, for despite being a smoker he has no equipment.

At this point I wonder if he’s a ghost. We’ve had two clues: He’s not of Mrs Fennel’s ‘time’, and he has not even the most basic equipment on his person.

Hardy seems to be posing a riddle for his reader: Hardy gives us clues about him, we’re to use those clues to work out who he is.

Rich is not quite the word for me, dame. I do work, and I must work. … the oddity of my trade is that, instead of setting a mark upon me, it sets a mark upon my customers. … O my trade it is the rarest one, Simple shepherds all – My trade is a sight to see; For my customers I tie, and take them up on high, And waft ’em to a far countree!

Is he an executioner? The grim reaper?

My tools are but common ones, Simple shepherds all – My tools are no sight to see: A little hempen string, and a post whereon to swing, Are implements enough for me!

At this, the party come to the same conclusion I had a few paragraphs earlier. (Hardy is deliberately keeping the reader one step ahead of the characters.) They think he’s an executioner, a ‘public officer’, who has come to hang the sheep thief, who the characters have sympathy for. He was driven to steal out of desperation.

Stranger number three

The third of The Three Strangers contrasts in appearance with the others:

The door was gently opened, and another man stood upon the mat. He, like those who had preceded him, was a stranger. This time it was a short, small personage, of fair complexion, and dressed in a decent suit of dark clothes.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “THE THREE STRANGERS”

NARRATION

Told by a narrator long after the supposed event, this is a story in the tall tale tradition. This is not an omniscient narrator, but a local personality. So we can deduce that parts of it have been made up for colour. For instance, the scene in which criminal and executioner share stolen cake and mead together, one failing to recognise the other. It adds colour to the story to think this happens, but who was there to witness it? The room was empty, which is precisely why the men went in.

I’ve noticed lots of people say this story is narrated omnisciently. The story is narrated in omniscient style, as if the narrator can know everything.

SHORTCOMING

The shortcoming of this little party is that they are overly influenced by appearance. They are unable to correctly guess at who the strangers are. They’re looking closely at shoes and body language, reading intention into body language when we can’t possibly know someone’s inner thoughts just from their demeanour.

DESIRE

The party wants to enjoy a Christening with merrymaking.

After the strangers turn up and the third one scarpers, their desire changes. The men jump into superhero mode and want to save the day by tracking down the supposed criminal.

OPPONENT

Their constructed opponent is the third man, though the guy they’re after is actually the first man. They’re most scared of the second man.

PLAN

They will take lanterns and weapons and find the third man in the slippery darkness. Then they will turn him in to the authorities and receive pats on the back.

BIG STRUGGLE

The big struggle (battle/climax) is not when they find the third man — he goes happily with them (probably happy to have some shelter for the night, knowing he’ll be revealed as not the culprit, and that his brother is currently on his way out of the area.)

The big struggle is when the men get back to the cottage and have the conversation with the authorities.

ANAGNORISIS

They learn that they’ve got the wrong man, and that they’ve judged the strangers incorrectly.

NEW SITUATION

The sheep thief gets away because he is respected for his daring. The story is passed down as an important part of local history.

Header illustration: Henry Macbeth-Raeburn’s frontispiece for Wessex Tales, Volume Thirteen in the Complete Uniform Edition of the Wessex Novels, The Fennels’ Cottage, Higher Crowstairs (1896)