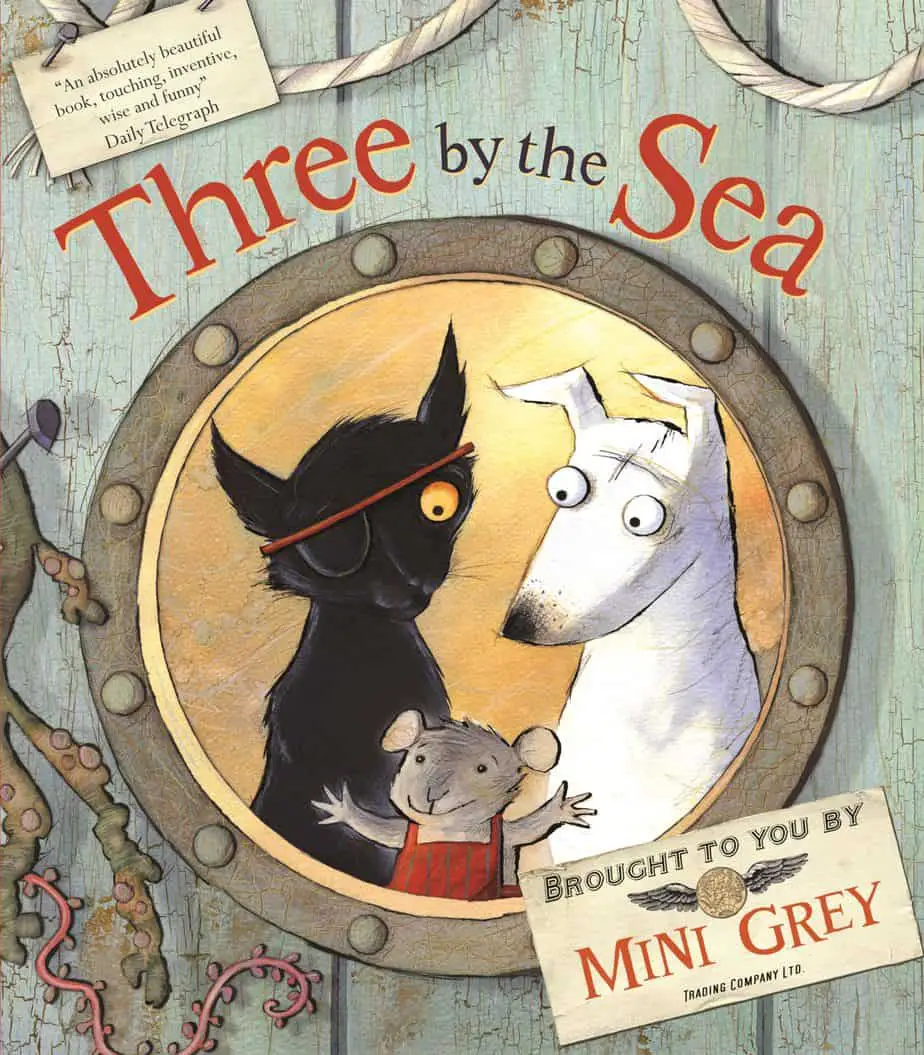

Three By The Sea is a 2010 picture book by British writer-illustrator Mini Grey. This storyteller comes from South Wales, which is somewhat evident in the setting. The most widely borrowed picture book from Mini Grey is the wonderfully metafictional Traction Man series.

This one has metafictional elements also, and offers plenty of picture book techniques to discuss. I even get into colonialist ideology and heteronormative gender roles.

By the way, there is a 1981 picture book that goes by the same title. That one is by Edward Marshall and was featured on America’s Reading Rainbow.

SETTING OF THREE BY THE SEA

- PERIOD — This story runs on “storybook” time, kairos rather than chronos. Generally, the technology in these stories is from early 20th century.

- DURATION — Three By The Sea begins by describing the daily life of characters as if they have always lived here. Once the story shifts to singulative, the time span feels like a matter of weeks.

- LOCATION — in a hut by the sea. As I note further down, we don’t know if this story is set on an island, but for all intents and purposes, this is an island story. Stories set on islands can be ideologically problematic.

- ARENA — This is a Robinsonnade rather than an Odyssean mythic structure. The main characters don’t go anywhere. The journey takes place entirely at home (on an ‘island’). In these stories, strangers arrive from elsewhere. The Cat In The Hat is another example. The Stranger by Chris Van Allsburg is another. The Dr Seuss example is carnivalesque and fun, the Van Allsburg example is dark and slightly menacing. This picture book is interesting because it sits somewhere between these two tones. I suspect this is why a large proportion of consumer reviews aren’t positive. Adult readers like to know what they’re getting. Is this a fun book or is it dark? Three By The Sea sits in the uncanny valley of genre.

- MANMADE SPACES — A hut, furnished with the basic necessities of life. The goods inside the hut are ‘storybook archetype‘ goods, and the off-kilter (non-realist) perspective illustrations are perfect for depicting storybook archetypes.

- NATURAL SETTINGS — The seaside can be a utopian playground or it can be treacherous. Seasides with rocks (rather than sand) tend to be a little more ominous. Again, this rocky seaside setting probably contributes to the uncanny feeling. The rocky landscape outside is good for depicting loneliness. The wild weather and the turbulent sea will come in handy for the near-drowning plot.

- LEVEL OF CONFLICT — The conflict, too, brings readers into an uncanny valley of “What’s going on here?” Three characters live together harmoniously until a stranger arrives and starts making suggestions. None of them is doing a good enough job of gardening/housework/cooking. Now the original three start arguing.

STORY STRUCTURE OF THREE BY THE SEA

PARATEXT

In a house by the sea there happily live a dog, a cat and a mouse. Well, happily enough until a stranger knocks on the door one night, offering them each a special free gift. Who is this mysterious salesman blowing into their little world and turning it upside-down? And can their happy home survive his trouble-making gifts?

MARKETING COPY

SHORTCOMING

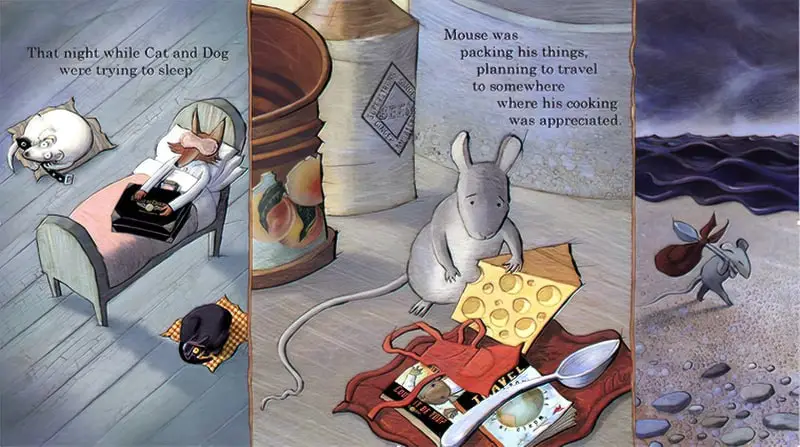

A dog, cat and mouse live together in a seaside hut. It’s interesting how the layout of the pages surprise us. Normally, pages in picture books are verso and recto, divided naturally by the spine down the centre of the book. This book frequently divides double spreads into three.

(Isn’t the little mouse with the knapsack on his stick adorable?)

Each animal living in this hut by the sea has their own roles. They perform their duties without collaboration. This is a specific kind of loneliness, as many a 20th century housewife would tell you. Many stories, especially children’s stories perhaps, are about characters who go from a state of loneliness to a state of collaboration or friendship. You can be lonely even when you share the same dwelling as someone.

Animals have symbolic gender. In the case of picture books, dogs are generally coded male, and if there’s a cat companion, the cat is coded female. Weird, I know, but I’ve heard more than one person say that when they were a kid they thought dogs were the males and cats were the females of the same species. (I’m pretty sure I even thought that myself.)

Note that we know the dog is male because of early use of ‘He’ in the story. We have to wait quite a while longer before hearing ‘she’ applied to the cat, but I had already coded the cat as female.

Why had I done this? Because tasks around a house is also gendered. Gardening is thought to be men’s work and housework women’s work.

The existence of a third animal messes with this gendered pattern somewhat. With the mouse we have a polyamorous trio, perhaps? It’s the job of the mouse to cook. In picture books, mice aren’t as symbolically gendered as dogs and cats are. Cooking is women’s work and chefing is men’s work, so kitchen work itself isn’t automatically gendered.

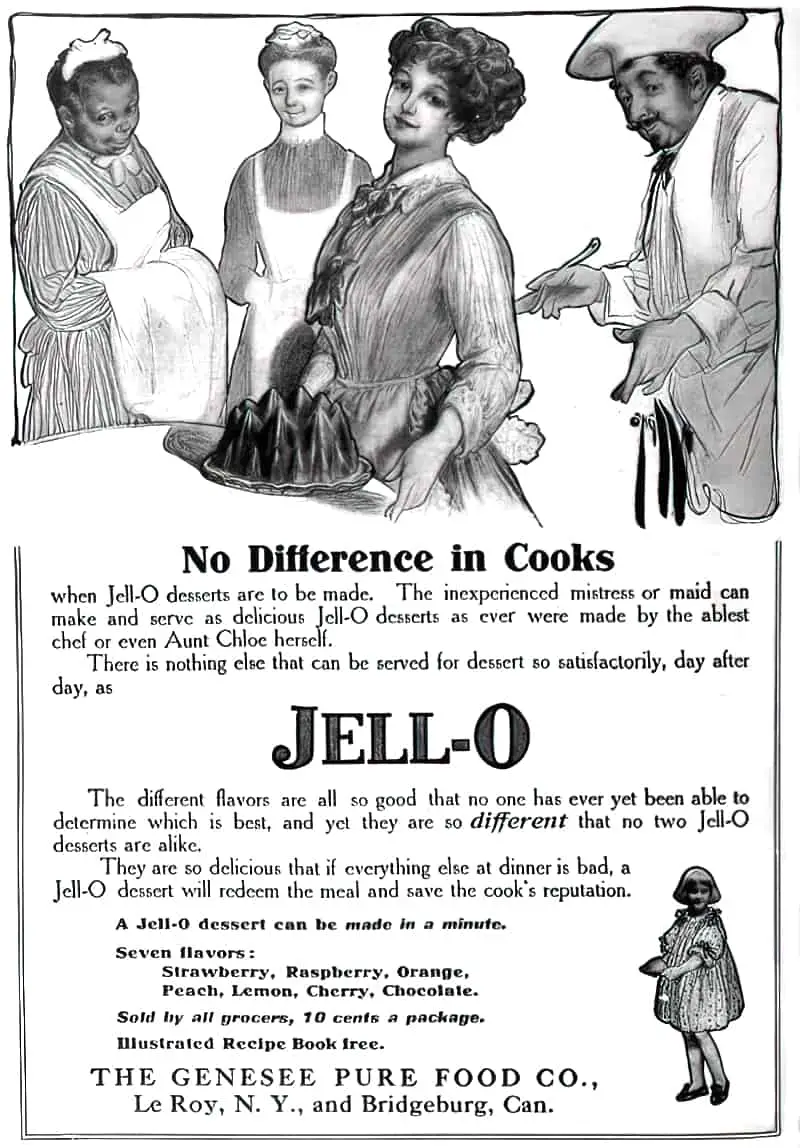

This American Jell-o advertisement from 1909 shows how (female) home cooks were less respected than (male) chefs, though perhaps a very experienced older woman might live up to the culinary reputation of a professional chef.

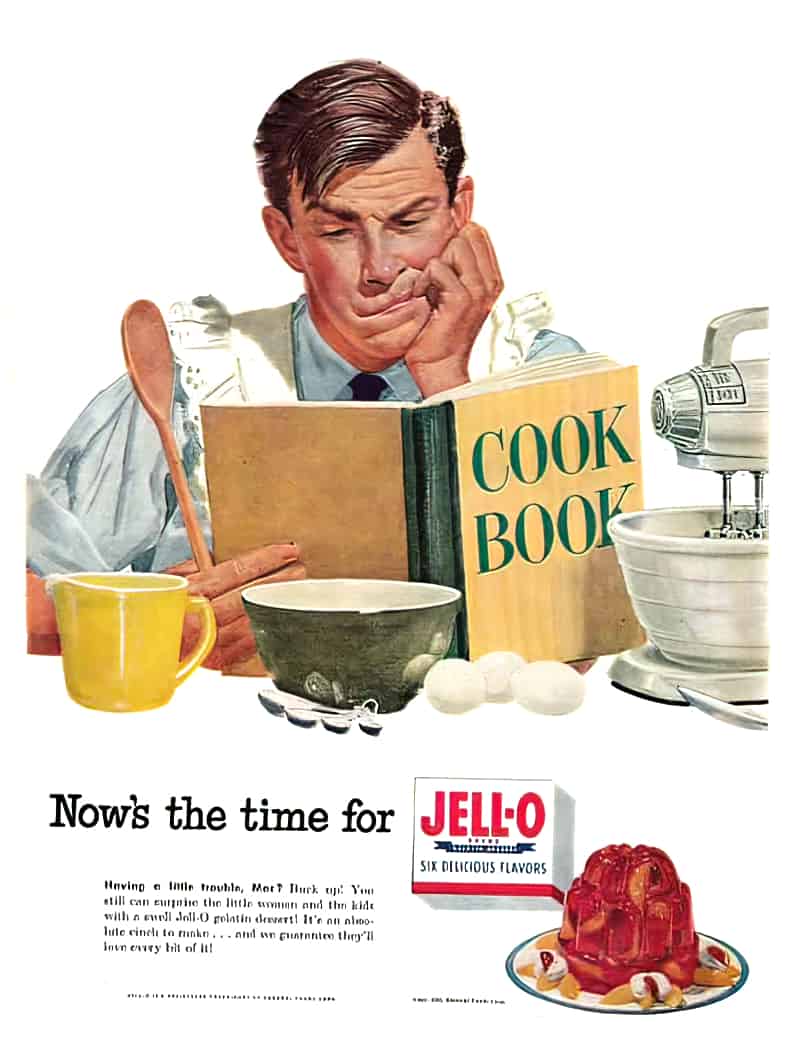

Here’s a Jell-o advertisement half a century later. (We can tell by the kitchen technology.) This time, humour derives from the quizzical look on the man’s face. A man couldn’t possibly be expected to be adept in the kitchen. Home cooking is women’s work.

Moreover, the man in the Jell-o advertisement above is wearing a woman’s frilly apron. This emasculates him. The very existence of crossdressing (and also trans women) is in itself meant to be a gag. Unfortunately this hasn’t changed in modern storytelling as much as we might hope it has. However, we’ve still come a long way since 2003, when mainstream American ‘liberal’ Jon Stewart mocked Ohio representative Dennis Kucinich for saying he’d support any gay or trans person for the supreme court.

Content note for transmisogyny.

Picture books such as Niki Nakayama: A Chef’s Tale blow the homecook-chef respect dichtomy out of the water.

“Niki Nakayama: A Chef’s Tale in 13 Bites is a picture book biography that tells the story of the powerhouse female Japanese-American chef and her rise to fame

As a child and adult, Niki faced many naysayers in her pursuit of haute cuisine. Using the structure of a traditional kaiseki meal, the authors Debbi Michiko Florence and Jamie Michalak playfully detail Niki’s hunger for success in thirteen “bites” — from wonton wrappers she used to make pizza as a kid to yuzu-tomatillo sauce in her own upscale Los Angeles Michelin-starred restaurant, n/naka.”

Back to Three By The Sea. Now that we know how Dog, Cat and Mouse spend their days in a hut by the sea, this particular story begins: “That night…” This sentence marks the shift from iterative to singulative time.

DESIRE

Until the stranger arrives the three by the sea don’t want anything. They’re happily going about their lives. Melodramas tend to start like that.

Once the stranger points out their deficiencies, each animal wishes the others would do a better job.

OPPONENT

The stranger is in the body of a fox and very clearly the villain of the piece… or is he?

Animals in children’s stories (and in some stories for adults) fall at various places along the anthropomorphism spectrum, between completely naturalistic at one end and humans-with-animal-bodies at the other. (The fish in this story are naturalistic fish, unfortunately for them but commonly for fish, which are delicious.)

Dog, Cat and Mouse are slightly more animalistic than the stranger, who upsets the equilibrium partly by bringing more human sensibilities with him. It is a very human thing to crave variety in food. I mean, cows eat nothing but grass. Dogs eat the same chow night after night and don’t seem to get sick of it.

The image of the stranger sleeping in the bed under an eiderdown while Dog and Cat sleep curled up on the floor is the main imagery signalling to readers that the stranger is more human than they are. This has unfortunate implications if readers get ‘colonialism’ out of the message. See more on that below.

PLAN

The Dog, Cat and Mouse have no plans so they must now ride along on the tails of the stranger’s plan. The stranger wants to shake these guys up. He points out their deficiencies. What a house guest!

THE BIG STRUGGLE

This unpleasantness culminates in the original housemates turning on each other and yelling. Then Cat and Mouse get into trouble in the ocean. Dog saves them both from drowning as he is a good swimmer.

ANAGNORISIS

Although they’ve all been arguing, the animals know now that they love each other. They need to get rid of the stranger who has sown the seeds of discontent among them. (The seeds in the story are actual herb seeds, but the metaphor is clear to an adult audience.)

NEW SITUATION

Before, only Dog did the gardening. Now he does it with Mouse.

Before, only Cat did the housework. Now Cat and Dog both keep the hut cozy and clean.

Before, only Mouse did the cooking. Now Cat helps out and gets to eat sardines.

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

It’s out of fashion to comment on the morals in a children’s story, lest we be mistaken for an eighteenth century school ma’am who believes stories for young ‘uns must teach lessons. I’m of the school who believes all stories teach something, whether explicitly or implicitly, whether by what’s on the page, or by what has been left off.

So of course I’m looking at a story’s ideology.

If the stranger had never arrived, the characters would have lived out the rest of their lives like automata, but not especially fulfilled. The mouse would continue making nothing but fondue and the others would never have realised they’re sick of it.

Household conflict is an unpleasant but necessary part of living together. If there’s no conflict, someone’s making a silent sacrifice.

My reading is a feminist one. But any contemporary Robinsonnade which features a stranger coming in to upset the peace (and don’t they always?) will be interpreted by some adult readers as a metaphor for colonialism.

The text offers much for a colonialist reading. For example:

- The stranger explains that he needs to sleep in a ‘proper’ bed. Meanwhile, the original inhabitants sleep on the floor. Beds, of course, are a white man thing. Most indigenous cultures around the world don’t sleep in this kind of bed.

- The (white man) fox is wearing a dapper suit while the original seaside inhabitants wear very few clothes.

- The dog’s gardening might be stand in for ‘agriculture’, although this comparison doesn’t work for me as part of a commentary on colonialism. (Indigenous cultures are experts at managing their own land, whereas bones yield nothing.)

RESONANCE

If, say, a picture book creator wanted to use the example of polyamory in a picture book as a way of commenting on the way heteronormative couples fall into heteronormative roles by default without communicating with each other, content in a non-woke culturally conforming way but never fully self-actualised, how might they go about it?

They’d use animals, of course, and few readers would notice what happened.

I’m not suggesting this author was deliberately going for polyamorous utopia… necessarily. Why ‘Three’ by the sea and not two? What’s the storytelling (Doylist) reason? Mouse may have been added to avoid making an overt commentary on binarist culturally ascribed gender roles.

When will we see the first mainstream published polyamorous picture book starring actual humans? Whenever romantic minorities achieve representation overtly in picture books we’ll know culture has changed for the better.

Unfortunately, if our take on this picture book is commentary on colonialism, the ending is problematic. White man has landed on shore and exerted his own customs upon content native people. He initially created discontent but ultimately left them alone and as a more cohesive group with better customs. The problem? Here in the real world, white man never left. If this is a story of colonialism, it is your ultimate cozy colonialism.

If that’s what this is, it’s certainly not the first picture book to do it, which is why deep-thinking readers are primed to find it. The Island of the Skog by Steven Kellogg is a well-known 1973 example.

Jenny and her city-mouse friends take to the seas in search of a more peaceful place to live. But when they arrive at what first seems the island of their dreams, they have a giant problem to contend with: the island’s only inhabitant, the Skog. Judging by his enormous footprints, he seems a more terrible threat than a hundred urban cats and dogs. How will the mice master their new domain?

Three By The Sea works for me as a commentary on gender roles and even looks amazingly progressive in its romantic possibilities. As a commentary on colonialism, nope.

This 2010 picture book is also a standout example of how different readers receive different experiences from a story. A narrative that succeeds on one level can flop on another. An author’s intention is utterly irrelevant.

Note that Robinsonnades are especially prone to be read as takes on colonialism, especially when set on an island. Even though Three By The Sea isn’t set on an actual island, the colonialist issues embedded in island stories kick in when a story is set beside a sea.