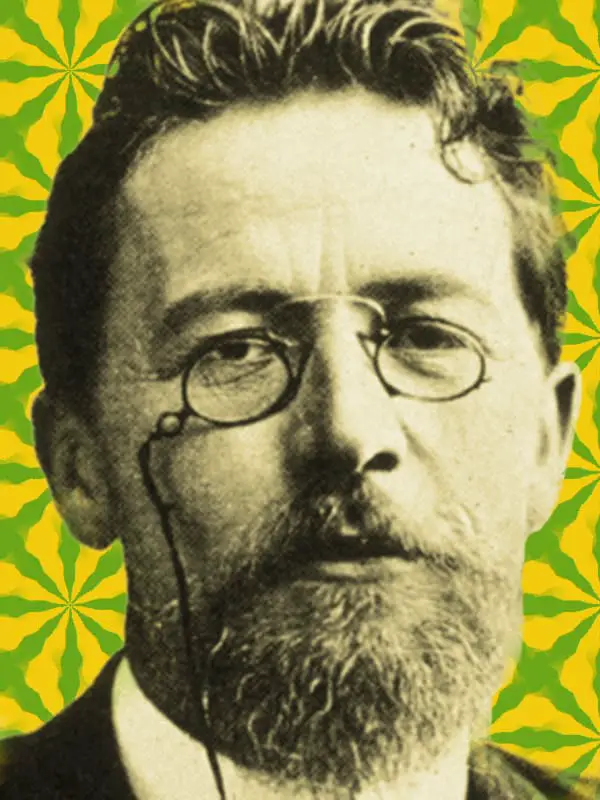

Anton Chekhov was a Russian writer who lived 1860-1904. He financially supported his extended family and initially started writing to support them. But he considered himself mainly a doctor. He treated people experiencing financial hardship for free. He died at the age of 44 from tuberculosis.

1. CHEKHOV DID NOT OVERWRITE

You’ll hear Chekhov related advice in every writing group ever.

In short stories it is better to say not enough than to say too much, because,—because—I don’t know why.

One would like […] descriptions to be more compact and concise, just two or three lines or so.

Take out adjectives and adverbs whenever you can.

My own experience is that once a story has been written, one has to cross out the beginning and the end. It is there that we authors do most of our lying.

Chekhov

In his essay “Notes on the Novella” , Graham Good considers Chekhov the inventor of a ‘new form of novella’ involving a ‘minimal plot’. (Good uses the word ‘novella’ but is talking about short stories.)

As for the writing process itself, Chekhov said, “the middle is the difficulty”.

2. OFTEN THE MAIN CHARACTER DOES NOT CHANGE

Chekhov’s stories are frequently less about change than they are about the failure to change. Chekhov was generally pessimistic about the possibility of change. This is more true to life than other forms of storytelling, for example any movie coming out of Hollywood today — audiences are there to see a character change.

Even when the characters do change, their changes fail to last, merely complicate the existing conflict, or create a new and often greater conflict.

See also: Character Transformation In Fiction.

3. CHEKHOV WAS HUGELY INFLUENTIAL

Chekhovian is now a word. Examples of Chekhovian writers:

- Henry Green (English) — who likes to ‘gag commentary’ (give even fewer reasons) than Chekhov even did.

- Katherine Mansfield (New Zealander) — early in her life she admired Ivan Turgenev but after discovering Anton Chekhov she cast Turgenev aside. Sure enough, her best work was written after her discovery of Chekhov. The Garden Party, for instance, has a distinctively Chekhovian ending. Some people say she out-and-out plagiarised Chekhov’s “Sleepy” when she wrote “The Child-Who-Was-Tired.” Mansfield considered herself the English language Chekhov. Like Chekhov, Mansfield died young from complications of tuberculosis.

- Raymond Carver (American) — influenced by Chekhov and Hemingway, who was himself influenced by Chekhov

- Beth Henley — modern American playwright

- James Joyce (Irish)

- George Orwell (American)

- Strunk & White — who wrote the grammar guide emphasising simplicity

- Matthew Weiner — because the main male characters in Mad Men fail to change and that’s the whole point, unlike most other novelistic TV series. “1960 Sterling Cooper is the manor house in “The Cherry Orchard,” a besieged institution about to be swept away by the new order.” — John K.

4. CHEKHOV CHANGED THE NATURE OF ENDINGS

And knew exactly what he was doing when he said, “Either the hero gets married or shoots himself […] Whoever discovers new endings for plays will open up a new era.”

Chekhovian endings tend to emphasize the continuation of conflict, not its conclusion.

When I am finished with my characters, I like to return them to life.

One story even states: “And after that life went on as before.” While this feels like a ‘non-ending’, what it is, is a truncated ‘New Situation’ stage.

These are subversive endings, designed to undercut our expectations of a ‘finished, satisfying story’. Such endings force readers to examine our conceptions about life and human nature.

The novel, and perhaps even more so, the short story does not provide philosophical answers, and Chekhov was fine with this state of affairs, saying that stories only need to ask the right questions.

Chekhov, and his descendants, may have together influenced children’s literature, including picture books:

There is a growing tendency for picture book endings to be left open, and more often than not, they pose questions to which there is no easy answer. Often the themes are what Egoff calls ‘the darker side of human experience’, as if authors wish to insist that the security of childhood be shattered as soon as possible, or maybe inferring that it is fiction anyhow.

Clare Scott-Mitchell, Give Them Wings, 1988.

If he does this, he does so in order to make the reader have the epiphany his protagonist fails to have.

He did this more in his later work.

He did this because an epiphany is more powerful if the reader experiences it rather than merely witnesses it happening in a character.

Unreliable narrators are particularly useful for achieving an epiphany in the reader.

See also: Short Story Endings

5. CHEKHOV’S GUN

This storytelling term came from a piece of writing advice he issued once:

One must not put a loaded rifle on the stage if no one is thinking of firing it. If you say in the first chapter that there is a rifle hanging on a wall, in the second or third chapter it absolutely must go off. If it’s not going to be fired, it shouldn’t be hanging there.

You don’t find many real guns in children’s literature, but the technique is still used. I call this Chekhov’s TOY Gun.

6. CHEKHOV’S SIX PRINCIPLES OF A GOOD STORY

According to Chekhov:

- Absence of lengthy verbiage of a political-social-economic nature

- Total objectivity

- Truthful descriptions of persons and objects

- Extreme brevity

- Audacity and originality: flee the stereotype

- Compassion

7. CHEKHOV AND OBJECTIVITY

Many commentators have said Chekhov created narrators who are ‘perfectly neutral observers’. These narrators ‘simply register phenemena with the mindless impersonality of a camera or a tape recorder. (For more on that see John Hagan.)

But we need to define what we mean by objectivity, as described above. If by ‘objectivity’ we mean ‘moral indifference’, we can’t say Chekhov’s narration is objective. He definitely wrote stories with an agenda, even though he avoided ‘subjectivity’.

Chekhov avoided the sort of subjectivity in which the author is ‘continually falsifying the truth of his cahracters by making them behave in ways that are pleasing to himself’ (Hagan).

8. CHEKHOV’S DETACHMENT FROM POLITICS

The novel depends enormously upon its sense of a stable social structure and the short story does not really depend on there being a social structure at all. Perhaps there is one of some sort, but it can direct itself to life outside the theoretical, or practical interest of the country. One of the problems I think that Chekhov had when he wanted to write a novel was that he did not quite have the breath for it: the society he lived in was despotic and anarchic. He had his opinions about it but that is another matter. He was detached from ideological politics.

Journal of the Short Story In English Autumn 2003

SEE ALSO

And Then There Was Chekhov: The Librarian Is In Podcast, Episode 43