“There Will Come Soft Rains” (1950) is a short story by American author Ray Bradbury. I thought I’d better read it because August 4 2026 is looking nearer and nearer, and I’d like to know what to expect in four years’ time.

Here’s your soundtrack for this story, called “The Humans Are Dead” from New Zealand’s fourth most popular guitar-based, digi-bongo, acapella-rap-funk-comedy folk duo. Or maybe keep this until the end, to cheer yourself back up because, content note: The dog dies.

PARATEXT

Some readers consider “There Will Come Soft Rains” the sequel to Bradbury’s “The Veldt”.

Colliers Magazine, where the story first appeared in May 1950, said “There Will Come Soft Rains” is ‘the one story that represents the essence of Ray Bradbury.’

The Pulitzer Prize board said, “While time has (mostly) quelled the likelihood of total annihilation, Bradbury was a lone voice among his contemporaries in contemplating the potentialities of such horrors.”

SETTING OF “THERE WILL COME SOFT RAINS”

PERIOD

The talking clock gives us a precise date: 4 August 2026, seventy-six years into the future. Bradbury was imagining a time when he knew he’d definitely be dead. (He died in 2012 at the age of 91.)

Three months before this story was published, The USA announced that it was going to start working on a hydrogen bomb in response to the USSR’s atomic bomb. Many people, including Bradbury, weren’t too happy with these plans. It didn’t help that the scientists themselves thought the experiments might end in fire.

DURATION

This short story is sub-headed all the way through with timestamps which take us through the course of a day, which is now run by machines. As we all know, machines require specificity, and time is one example specificity. It makes sense that we are hyper away of the time.

This hyperawareness of time also hooks into the theme of capitalism, which started with the (imaginary, dead) human in bed woken up by a machine voice. Sleeping in is not an option when your existence relies upon being at work. Whereas the storyworld is fictional, the feeling of being ‘chased by the clock’ is very real to a 1950s reader (and beyond).

LOCATION

Allendale, California. Like Springfield of The Simpsons, Bradbury picked a run-of-the-mill town name.

Allendale could be: Allendale Fremond, Allendale, Oakland, Allendale Solano, or some other Allendale.

If I were creating a made-up place-name for Australia I might call it ‘Macquarie’ or ‘Murrumsturt’. For New Zealand, Havelock South, or something starting with ‘Wai-‘ (meaning ‘water’ in Te Reo.) New Zealand author Janet Frame made up Waimaru for her début novel, concatenating the Māori prefix with the real place of Oamaru.

What would you call a fictional, unidentifiable, ‘everywhere-nowhere’ region near where you live?

ARENA

A single dwelling, a house. This house is alive.

See: Buildings As Characters In Fiction

MANMADE SPACES

The walls of this house (at least, the nursery) are ‘made of glass’. Houses made of glass are typically devoid of love and care. If you ever find yourself the character of a story, never ever move into a house with huge swathes of glass. You will not be happy living there.

NATURAL SETTINGS

The scrawny dog brings a bit of nature into the house, which the personified robo-vacuum army of mice do not appreciate. They get rid of anything natural right away. In this new world, biological life is incompatible with tech-perfection.

These mice do more than a robo-vacuum cleaner. Turns out they can shoot water in case of fire.

WEATHER

It was raining outside.

“There Will Come Soft Rains” by Ray Bradbury

Bradbury gradually reveals that there are no humans alive in this world, and we will likely guess before we are told that the rain is acid rain.

This particular detail may be more easily surmised by older readers, who will remember the stories that came out of Hiroshima. When the story was first published, early August, 1945 was only five years earlier in readers’ memories. Everyone at the time was familiar with images coming out of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The atomic bomb left disturbing shadows of people against hard surfaces. These shadows encapsulated people’s final moments, and are the clear inspiration behind Bradbury’s short story.

Animals took shape: yellow giraffes, blue lions, pink antelopes, lilac panthers cavorting in crystal substance. … the walls lived.

“There Will Come Soft Rains” by Ray Bradbury

Another inspiration is a 1918 poem, quoted within the story, by American poet Sara Teasdale (1884–1933). The story’s version of Alexa or Siri reads this wartime/pandemic poem to the dead children who used to inhabit the nursery.

TECHNOLOGY CRUCIAL TO THIS PARTICULAR STORY

The voice-clock of the opening sentence which says, “Tick-tock, seven o’clock, time to get up, time to get up, seven o’clock!” reminds me of the screaming school bell from Hexside School of Magic and Demonics in The Owl House animated series.

American sci-fi writers of the 20th century were obsessed with Rube Goldberg machines and with breakfast-making in particular. It must have been the dream of many to lie in bed a little longer, letting machines take care of breakfast for you. Perhaps there’s something about a popping toaster which lends itself to such imaginings.

In the kitchen the breakfast stove gave a hissing sigh and ejected from its warm interior eight pieces of perfectly browned toast, eight eggs* sunnyside up, sixteen slices of bacon, two coffees, and two cool glasses of milk.

“There Will Come Soft Rains” by Ray Bradbury

*Bradbury did not foresee that eggs would later be demonised as bad for cholesterol from the 1990s onwards. These dead people even eat egg sandwiches for lunch. (Also, like Alien, Bradbury didn’t realise that people would not typically be smoking cigars in the distant future. The tobacco revolution happened very quickly, in hindsight.)

Earlier in the century, men had their wives carry out such tasks, of course. Culture changed in the 1960s, and now women entered the workforce en masse. No more time for cooked breakfasts. Cereal and milk. Bradbury’s breakfast-making machine feels like a wish fulfilment fantasy specific to white American men of Bradbury’s exact vintage.

Bradbury describes a modern waste disposal unit. I wondered when these were invented. Bradbury was describing the ubiquity of something which had already been invented, way back in 1927, though it was called a ‘garburator’ back then. (I wish we’d kept that name.)

He predicted robot vacuum cleaners, comparing them to mice. He must have imagined an army of smaller vacuum cleaners rather than one or two, more like the size of a cat. Bradbury’s vision feels like those soot sprites (susuwatari) from various Hayao Miyazaki movies, including, notably Totoro and Spirited Away.

In English speaking countries we have historically called such creatures ‘Brownies’. Brownie refers to any type of type of fairy who enters the house, sometimes causing mischief, oftentimes helping us out (see: The Elves and the Shoemaker, in which the ‘elves’ are actually ‘brownies’.)

Japanese mythology cannot map perfectly onto Western words such as ‘sprites’ and ‘brownies’. (‘Dust bunny’ refers only to a visible bit of fluff and comes nowhere close.) In ancient/traditional Japanese thought, in line with Shinto, spirits and souls are seen in everyday things. These are properly ‘fairies’, but we have to go back in time and reclaim a much earlier notion of ‘fairy’ than the Tinkerbell-type creature English speakers think of today.

The incinerator, too, is reminiscent of another Studio Ghibli creation: The talking hearth (Calcifer) from their adaptation of Howl’s Moving Castle.

Ray Bradbury’s world, when The Humans Are Dead, is nevertheless imbued with ‘life’. This is life, but not as we know it.

Like the writers of Ridley’s Scott’s Alien (1979), 20th century humans failed to predict just how much of our memories would be outsourced to technology. Bradbury’s talking clock repeats the day’s date three times ‘for memory’s sake’. Whose memory? Who really needs to remember the date these days, when the date is displayed on every interactive screen? Even daylight savings goes almost unnoticed when your smart devices change the time for you.

In some ways, Bradbury imagined the future accurately. He didn’t predict smart phones, but our phones do tell us what’s happening for the day. Mostly they don’t speak, so he got that part wrong. Science fiction writers failed to consider how annoying machine-yakking would be (and also how annoying people find electronic beeping. Why does everything beep, in the year of our Lord, 2022?) That said, when I have an issue with my grocery delivery, I now talk to an animated oily fruit rather than to a real person. This change happened around 2020. The supermarket’s ‘Olive’ is not yet at AI level, but ‘she’ gets the job done. Once you learn the keywords which set her off, correcting an order is more simple than dealing with a human.

Even Michio Kaku, publishing his book Visions in 1997, sort of predicted smart phones but not really? He predicted ‘tabs’, ‘pads’ and ‘boards’, and that the first 20 years of the 21st century would see offices filled with these flat, disposable, digital surfaces. He was eerily accurate with the ‘pad’. The smaller ‘tabs’ of his predictions map onto smart watches. ‘Boards’ map onto interactive whiteboards, which are now standard equipment in many classrooms of rich countries around the world. He overestimated how quickly the price on these items would fall. While the life on smart items remains short (by design), they’re not yet at disposable prices. (In fact, smart phones continue to climb in price.)

Bradbury’s technology infantalizes by speaking in rhymes that would be at home on the set of Playschool.

Various contemporary commentators express concern at the extent to which we are now outsourcing our brains, and also the extent to which social media is negatively influencing our mental health. Bradbury may have gotten the details slightly wrong, but his vision of infantalizing technology, or at least our increasing concern about it, were spot on.

Bradbury extends this infantalizing analogy while simultaneously making excellent use of horror tropes associated with childhood.

LEVEL OF CONFLICT

No one is alive in this story. The world-changing conflict happened in the recent past. (We know it was recent because it happened within a single dog’s lifetime.)

STORY STRUCTURE OF “THERE WILL COME SOFT RAINS”

SHORTCOMING

This is a story concerning a world, not just a community, not just a family, not a single person.

The world is devoid of human kindness and empathy. It is therefore doomed from the start.

DESIRE

Writers are told that main characters must desire something, ‘if even a glass of water’ (Kurt Vonnegut). So how do we craft a story in which all of the sentient creatures are dead at the start? How can anyone possibly want anything?

First of all, this plot is well-suited to the short form and audience interest would not be sustained across a novel-length work. So there’s that.

Here’s how Bradbury does it: He has killed off the actual life, but via metaphor and simile, he brings the objects alive. He gives the appearance of desire.

OPPONENT

With all the humans dead, the conflict is now between:

- The dog and the robot mice

- The fire and the house, both animated

Opposition is also manufactured by way of simile, between elephant and snake, between surgeon and house as skeleton:

The fire backed off, as even an elephant must at the sight of a dead snake.

The house shuddered, oak bone on bone, its bared skeleton cringing from the heat, its wire, its nerves revealed as if a surgeon had torn the skin off to let the red veins and capillaries quiver in the scalded air.

“There Will Come Soft Rains” by Ray Bradbury

PLAN

Artificial intelligence has its own plan, though it’s not informed by real desire. The plan appears to be: Go on as before. No one cares if actions have consequences. As Bradbury puts it, these creatures have a ‘sublime disregard’ for whatever’s happening. (For more on the meaning of ‘sublime’, see The Overview Effect In Fiction.)

Ultimately, such a self-effacing plan will lead to destruction.

Life metaphors are not limited to the fiction writers of this world. Scientists, too, think in this way:

The idea of ubiquitous computing has been amplified and embellished by many of the key thinkers in the computer field. Paul Saffo, director of the Institute for the Future and one of the leading futurists in the country, is one of many computer experts who feel that some form of ubiquitous computing is inevitable, given the proliferation of cheap microchip technology. His particular version of this future is called the “electronic ecology.”

When we analyze the ecology of a forest, we treat it as a collection of animals and plants which exist in harmony and interact dynamically with each other. To Saffo, every ten years or so there is a key technological advance which changes the relationship between the creatures in what he terms the electronic ecology.

Michio Kaku, Visions, 1997.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

The battle between the house and the fire, who seems to walk through the house like the calm, psychopathic and ultimately self-destroying Anton Chigurgh from No Country For Old Men.

In the 20th century, when sci-fi writers wanted to convey computers-gone-awry, they tended to pick up the pace. In Alien, we’ve got all those flashing lights as Ridley sets about blowing up the mother ship. (I find it highly unpleasant to watch.) Here, Bradbury’s Rube Goldberg machinery starts working at a frenetic pace.

This imagining probably works because it mimics the raised heartbeat of a biological entity. In reality, we know that’s not what computers do when they run into trouble. They do the opposite, in fact.

ANAGNORISIS

We start to realise there are no humans on this Earth when the Rube Goldberg breakfast-making machine washes a perfectly good, slightly overcooked breakfast down the sink.

The final sentence offers another revelation to readers who remember when the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima. This marks the (almost) anniversary of August 6, 1945.

NEW SITUATION

Everything is dead.

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

“The last voice.” The Earth will soon be silent.

RESONANCE

The threat of nuclear destruction will probably never leave us. Gen Z are growing up under the imminent threat of climate change. For my generation, Gen Z, we rarely heard about climate change. For us it was about putting our own rubbish in the bin rather than leaving it lying around. Later it was about separating recycling. For us, the existential* threat was nuclear war.

*Existentialism: an outlook which begins with a disoriented individual facing a confused world that they can’t accept. Existentialism’s negative side emphasizes life’s meaningless and human alienation. Think: nothingness, sickness, loneliness, nausea.

Come 2022, the threat of nuclear war and climate change coalesce. Unfortunately, Ray Bradbury’s 1950 short story continues to speak to our fears.

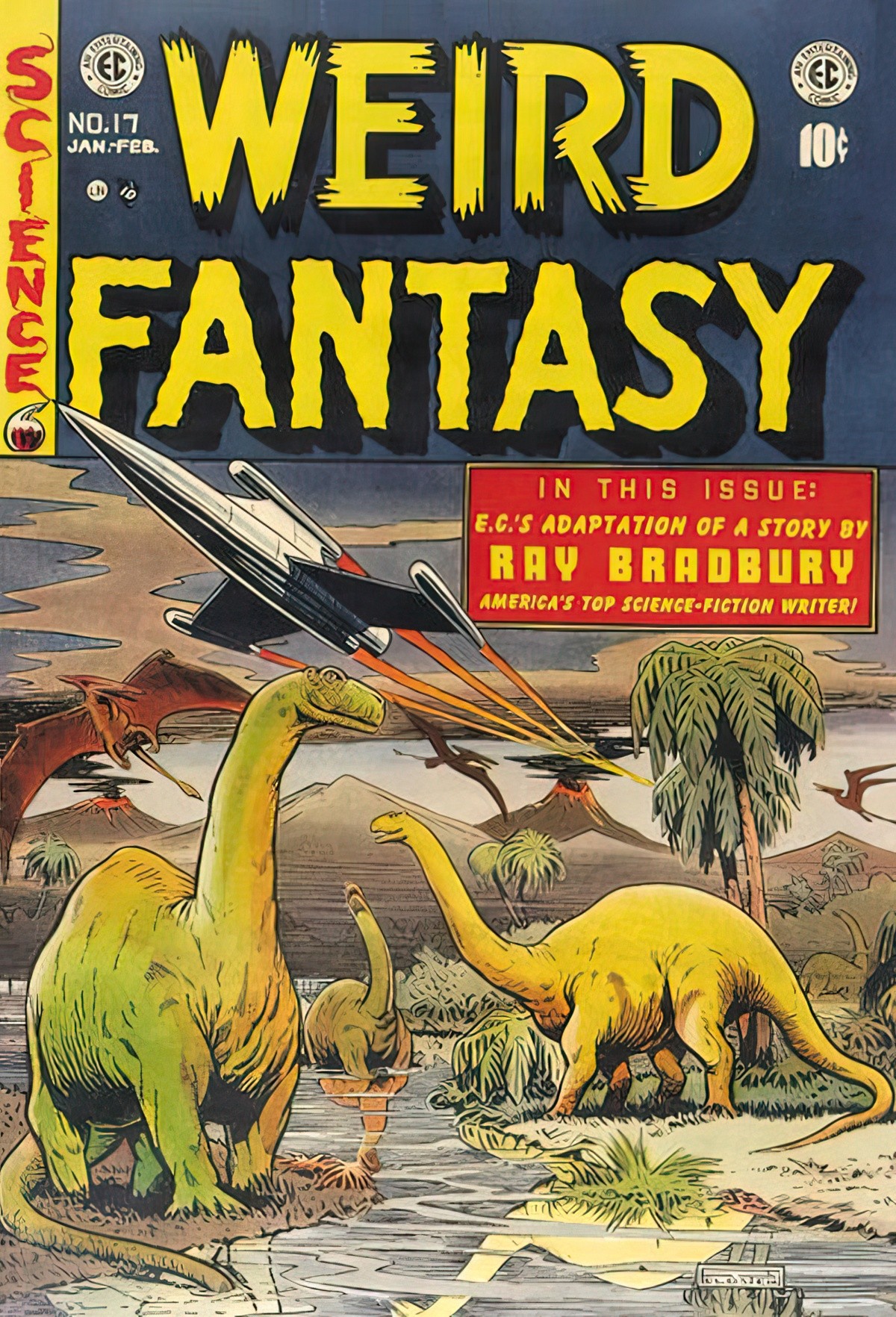

Header illustration: The cover of issue 17 of Weird Magazine, which featured an adaptation of Bradbury’s story, illustrated by Wally Wood.

COMPARE AND CONTRAST

The Ten-Year Nap is a 2008 novel by Meg Wolitzer. The opening reminds me of Ray Bradbury’s “There Will Come Soft Rains”.

All around the country, the women were waking up. Their alarm clocks bleated one by one, making soothing sounds or grating sounds or the stirrings of a favorite song. There were hums and beeps and a random burst of radio. There were wind chimes and roaring surf, and the electronic approximation of birdsong and other gentle animal noises. All of it accompanied the passage of time, sliding forward in liquid crystal. Almost everything in these women’s homes required a p[lug. Voltage stuttered through the curls of wire, and if you put your ear to one of the complicated clocks in any of the bedrooms, you could hear the burble of industry deep inside its cavity. Something was quietly happening.

BIP BIP BIP. By a bed on this Monday morning in fall, the first alarm went off in a house with cedar shingles in a small, buffed suburb, and a woman sat up, the prospects of the entire day rising before her. BOOP BOOP BOOP. Three towns over, there went another alarm, a full octave lower, and a woman broke the skin of consciousness in her colonial, blinking. “–A LOOK AT THE TRAFFIC. RANDY, WHAT’S HAPPENING OUT THERE?”

The Ten Year Nap, Meg Wolitzer

Living with Robots: What Every Anxious Human Needs to Know

There’s a lot of hype about robots; some of it is scary and some of it utopian. In this accessible book, two robotics experts reveal the truth about what robots can and can’t do, how they work, and what we can reasonably expect their future capabilities to be. It will not only make you think differently about the capabilities of robots; it will make you think differently about the capabilities of humans.

Ruth Aylett and Patricia Vargas discuss the history of our fascination with robots—from chatbots and prosthetics to autonomous cars and robot swarms. They show us the ways in which robots outperform humans and the ways they fall woefully short of our superior talents. They explain how robots see, feel, hear, think, and learn; describe how robots can cooperate; and consider robots as pets, butlers, and companions. Finally, they look at robots that raise ethical and social issues: killer robots, sexbots, and robots that might be gunning for your job. Living with Robots: What Every Anxious Human Needs to Know (MIT Press, 2021) equips readers to look at robots concretely—as human-made artifacts rather than placeholders for our anxieties.

New Books Network

In this episode, we discuss “There Will Come Soft Rains” by Ray Bradbury. What can we learn from a story with no apparent characters? How can we establish a POV without characters? How does language introduce hidden personifications? How can we use these hidden metaphors to pump up our prose?

Alternate version: “August 2026: There Will Come Soft Rains” by Ray Bradbury.

Why Is This Good? podcast