The other day someone in a book recommendation group wanted suggestions for a 10 year old who loves Hayao Miyazaki movies.

This basically describes my own kid, who’s been a Miyazaki fan since the age of three, before she even knew transmogrification wasn’t a thing. My kid enjoys Yotsuba&! (among other things, so I recommended that.

Yotsuba&! is a manga series which has been translated into English to capture an international market. We can deduce: Yotsuba&! is actually one of the least ‘weird-to-Westeners’ stories produced by Japan.

Someone else said, “Oh I love Yotsuba! She’s so cute.” Another person mentioned the general weirdness of Japanese media for kids. (It’s worth mentioning at this point, our kids generally love this stuff. Adults find it weird.) In any case, I should probably have recommended the series ‘with reservations.’

Because of my interest in storytelling, I wondered if I could attempt a theory on why, so often, adult English speakers find Japanese stories so… inexplicably weird.

- What do we mean when we call something ‘weird’?

- Why does a culture find some story elements ‘plausible’, but elements from another culture ‘weird’?

- What are the different expectations of ‘a story suitable for children’?

Any insight I have on this subject comes from 10 years of Japanese study, including a couple of years living in Japan — first as a high school exchange student living with a host family, next at a Japanese university living in a dorm Then I taught Japanese at high school level, though I’ve had little to do with Japan since the 2000s. I can only guess at the general trajectory, as more and more young Japanese people spend part of their youth abroad, many learning English to a high level which no doubt leads to a more internationalised Japan.

Conversely, is the West becoming a bit more accepting of Asian entertainment? I know white people who listen to nothing but K-Pop, and others who spend a lot of time playing Nintendo games from the 80s and 90s. Western fans of Japanese entertainment tend to be uber fans.

Japanese Weirdness and the Western Media

My general thoughts on Japanese ‘weirdness’ is this: Our Western media loves to paint Japanese people as downright quirky. We’ll pick up any out-there news article and disseminate it with glee, to bolster our view that these people are somehow ‘Other’. Oftentimes, our media’s ‘proof’ of Japanese weirdness is a complete misunderstanding of intent — Japanese people love to poke fun at themselves. Where they’re poking fun, we’re imagining they are taking themselves completely seriously. Either that or we can’t possibly see the joke because jokes are so culturally specific.

Yotsuba&! is a great introduction to Japanese ‘weirdness’.

YOTSUBA&!: A CASE STUDY IN WEIRD

Yotsuba&! is centered on Yotsuba Koiwai, a five-year-old adopted girl who is energetic, cheerful, curious, odd, and quirky — so much so that even her own father calls her strange. She is also initially ignorant about many things a child her age would be expected to know, among them doorbells, escalators, air conditioners, and even playground swings.This naïveté is the premise of humorous stories where she learns about, and frequently misunderstands, everyday things.

Wikipedia overview

Yotsuba means ‘four leaf clover’ in Japanese, which explains the green hair and four pigtails.

THE TITLE

Well, the first weird thing is the title. An English speaker would not shove an ampersand into that title unless it meant ‘and’. What’s it doing there?

Well, that symbol means ‘and’ in Japanese, too. It’s just used a little differently here. Japanese orthography doesn’t put spaces between words (because there are three different ‘alphabets’ and it doesn’t need to).

The phrase Yotsuba to means “Yotsuba and,” a fact reflected in the chapter titles, most of which take the form “Yotsuba and [something].

Wikipedia

LANGUAGE

First of all, Yotsuba&! is full of onomatopoeia and mimesis, which is amazingly rich in Japanese. The English version keeps the Japanese (written in Japanese) and adds its English transcription in small letters. For an English speaker, this still won’t be enough. We do fine with the echomimesis, but need further translation for ideophones such as ‘kuru’ to represent the turning of something. (This comes from the Japanese verb form of ‘to turn’, thus making perfect sense to Japanese readers.)

LOST IN TRANSLATION

Japanese is so different from English that wordplay never translates. Yotsuba is young and gets words wrong, which presents a problem for the translator to the point where jokes simply do not work. Sometimes the translator gets around this by describing the problem in marginalia. In Yotsuba&! number one, Yotsuba mistakes her father’s job ‘translator’ for ‘jelly maker’. This works in Japanese because the words sound very similar. (Even the translation of ‘jelly’ doesn’t work — konnyaku is not what Westerners think of when we hear the word ‘jelly’ — it’s a grey, black flecked substance made from potato starch.) On a meta-level, it’s ironic that the character of the father is a translator, yet the joke about his job simply doesn’t translate.

THE CHARACTER WEB

The fictional child orphan is a very American trope. Yotsuba as a character doesn’t fit this trope at all, though. This backstory (such as there is) feels foreign. The father just kinda picked her up from someplace.

Yotsuba is not really a… real child? She’s more like Ponyo of the Hayao Miyazaki film — someone who just turns up and joins the family. She seems to have come from a different planet. In the world of the story, she’s understood to simply be ‘foreign’:

She is also initially ignorant about many things a child her age would be expected to know, among them doorbells, escalators, air conditioners, and even playground swings. This naïveté is the premise of humorous stories where she learns about, and frequently misunderstands, everyday things.

This particular character trope isn’t entirely foreign to a Western audience. We’re seeing a lot more comedy about characters who don’t seem to know what on earth is going on around them. Some of these characters are coded as autistic, which I go into more thoroughly here.

Because Yotsuba has no mother, and because her adopted father is so useless, the girls next door step in and they perform much of the emotional (and housework) labour a mother would otherwise provide. I don’t believe this is a specifically Japanese phenomenon at all, but it is an unusual family set up to see in contemporary Western children’s literature. Hopeless Dads are dime a dozen, but Dads who kind of fall in lust with their children’s informal babysitters next door? Not so much. (See below.)

SPECIFICALLY JAPANESE SYMBOLISM

In Yotsuba&! volume one, the story takes place over summer. Summer in Japan has its own specific atmosphere — after the rainy season of June comes a very hot and humid time, and unless you live in a very built-up area, summer sounds like cicadas. (Cicadas and frogs.) A ‘typical’ Japanese summer includes eating watermelons with family, wind chimes and festivals. This summer experience is depicted clearly in Yotsuba&!, though may not be coded as specifically ‘summer’ by readers who haven’t experienced the specifically Japanese summer. My Australian summer includes many of those things, too, but an Australian ‘vision of’ summer is different: the beach, swimming, surfing, shorts, sunscreen, icy-poles, thongs, beer. Each culture has its own Symbolism of Seasons, and Japanese symbolism is a little different even when summer itself is basically the same.

SPECIFICALLY JAPANESE CULTURE

As a high school exchange student, I was surprised to see teachers thwack students across the head. Touching the head is taboo in my own culture, especially when it’s a teacher to a student. Yet I saw it done mostly in jest.

Likewise, in Japanese entertainment, when one character hits another over the head, this is coded by the audience as funny. It’s one character ‘owning’ the other, usually as the conclusion (or as the main part) of a joke.

This joke is used numerous times in Yotsuba&!, first with one sister hitting the other on the head in the chapter where Yotsuba thinks she’s being abducted by the girl next door. (She doesn’t know that yet.) Later, Yotsuba insists everyone goes cicada catching. She jokingly ‘Catches an Ena’, which involves capturing her neighbour’s head in a net.

In another gag, Yotsuba’s father ends up with underpants on his head and pretends he’s some kind of underpants monster. This version of the joke translates the best out of all of these ‘head’ gags — probably because a young Western audience is also laughing at the inversion of a clothing article meant for the butt ending up on the head. For a Japanese audience there’s an added layer of embarrassment around showing your underwear to someone in your out-group — for girls and women especially, this is taboo. While modern attitudes are various, some Japanese women will never, ever show anyone their underwear, to the point where they won’t hang underwear on the line. (Therefore, a joke about the father’s underwear exposed to a non-family member works as a joke, but I doubt it would work if the underwear belonged to a girl.)

There’s a huge irony in this, which I’ve never been able to reconcile: Whereas the underwear of a post-pubescent Japanese female is absolutely taboo, the white, voluminous underpants of a little girl is considered cute, whereas in the West, adult women get to show their bodies as a form of empowerment, but when it comes to little girls, we are very protective of them. Pixar would never show the underpants of a little girl flying on a broomstick or falling comically from a height, but Hayao Miyazaki has no such qualms.

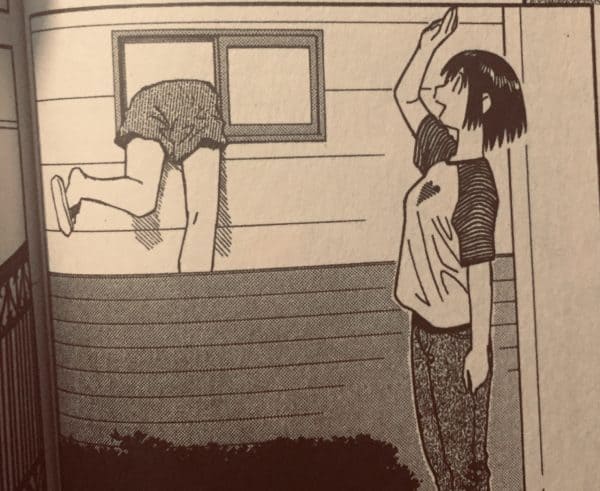

In Yotsuba&! we see examples of butt shots used comically:

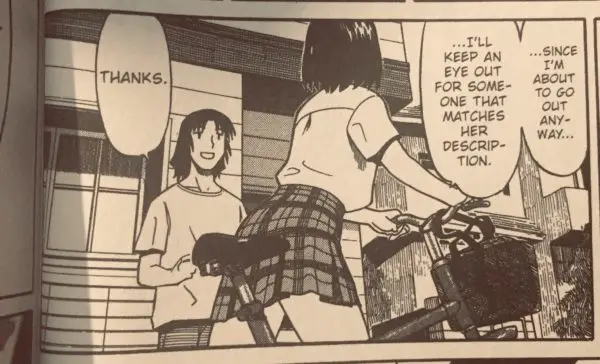

But my Western sensibilities come to the fore in the relationship between Yotsuba’s ‘father’ (according to the story he simply found her and decided to keep her), and his reaction to the triad of adolescent/teenage sisters who live next door.

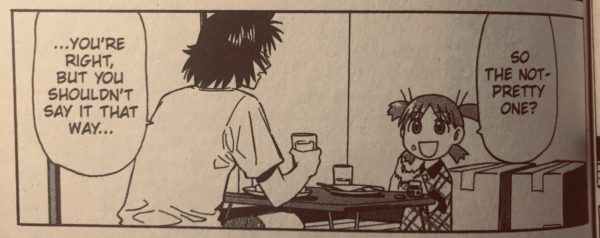

In the first, minor example, the comically inappropriate Yotsuba refers to one of the sisters next door as the pretty one, the other as the ‘not pretty’ one. The father says, “You’re right, but you shouldn’t say it that way…”

My Western sensibility wants a Good Dad to tell Yotsuba that all the sisters next door are beautiful in their own way, but this father is more pragmatic, instead acknowledging that yes, he has noticed and yes, some girls are pretty, others not so much. I’ve noticed in the West, a general lack of willingness to accept that some people fit the Beauty Cultural Norm better than others. The problem with that: Unless we accept Beauty as a concept, we can’t acknowledge Beauty Privilege. If we can’t acknowledge Beauty Privilege, we can’t go out of our way to move past it.

Besides, this father is not your typical father. He’s more of a young guy who isn’t quite up to the task of taking care of a kid. This kid regularly finds herself in perilous situations, because the father is asleep or busy working or whatever. A permissive, indulgent parent is useful to a writer of children’s literature, because it’s really hard to realistically get adult caregivers out of the way. Modern kids, in real life, are rarely afforded the opportunity to head off on their own adventures. Not so Yotsuba, who goes off on her own around the neighbourhood. “Don’t worry, she eventually comes back,” says Father to the concerned girl next door. While he’s sleeping, Yotsuba’s getting herself locked in the toilet, then escapes by tottering precariously along the rail of the balcony. Instead of fixing the lock on the door, the father leaves it be, paving the way for further embarrassing window-escape adventures. An adult Western reader may well look at this father-daughter relationship and have grave concerns. Has the creator removed the father from Yotsuba’s life in a way that doesn’t set us on edge? What is he even doing with this little girl? Does her origin story need to be explained a little more? Readers will vary on this point.

More salient: Is Yotsuba&! even for kids? At first glance, of course it is. Japanese publishers have definitely aimed it at a young child market: We know this because they include the ‘kana’ readings over the Chinese characters, which is a sure sign a book is aimed at emergent readers. (Around 5-8.)

The main character, Yotsuba is also five. But Yotsuba is five in the way Junie B. Jones is five — her particular quirks appeal to older readers.

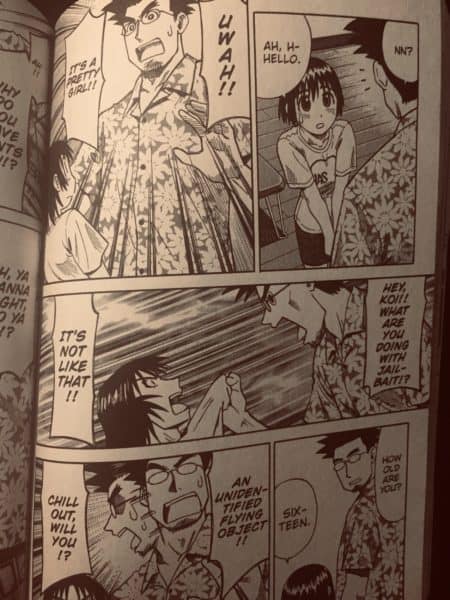

Here’s a scene Junie B. Jones would never include: The father’s friend comes round to the house, sees the girl next door with the father and makes a comment about ‘jail bait’.

This is icky to me, especially after the way in which this girl is introduced to Yotsuba’s father — and to the reader:

I’m no manga apologist, but it’s possible that within manga culture this is such a normalised objectification of a teenage girl that it doesn’t really even strike the manga-enthusiast as a sexualised pose. I recall my year as an exchange student, in which I wore the school skirt a lot lower than any of my Japanese classmates. I wore it just below the knee, whereas they rolled theirs up. Some concerned classmates offered fashion advice, and tried rolling it up at the waist to achieve a more acceptable look. The girls themselves have internalised the idea that women’s legs are to be looked at.

To me, this pose is very gazey and, depending partly on the viewer, absolutely sexual. I was prepared to look past it until the ‘jail bait’ section, but considering the story as a whole, the creators are well-aware of their intent: To depict these teenage girls in a sexual manner to appease the male gaze. Although we do see examples of the male gaze in Western children’s literature, it’s been a long time since I saw something this blatant. This is manga culture pulled down into children’s entertainment.

THE STORY STRUCTURE OF YOTSUBA&!

Yotsuba&! is the perfect example of an ‘episodic’ story, found quite often in middle grade fiction, especially that aimed at (and starring) girls. Boys more often go off on linear adventures, but in Yotsuba&!, each chapter is its own self-contained story. Apart from the first chapter, in which Yotsuba moves house and meets new people, any of the others could easily be switched around.

‘Episodic’ is often used as a negative descriptor when it comes to fiction — as a synonym for ‘boring’ or ‘goes nowhere’. Modern middle grade novels in English tend to have a single driving thread even if it includes subplots which seem to take the reader off on self-contained tangents. Diary of a Wimpy Kid is a good example of a Western counterpart. I’m also thinking of Clementine — also about the quotidian life of a girl. The difference is, each of the Clementine books has a single plot thread with means the chapters could not be switched up.

In general, Japanese audiences accept a slower pace. There’s a long history of very long Noh and Kabuki plays, in which the audience happily leaves part way through, goes to eat a meal, then comes back to see the end.

But partly this is because of the huge crossover appeal of its anime, manga and also pop music, which tends to be enjoyed by adults and children alike. To generalise, even children’s media ends up with a more adult pacing:

Toy Story – 76 mins

Brave – 84 mins

Monsters Inc. – 85 mins, 8 secs

Toy Story 2 – 85 mins, 32 secs

Inside Out – 87 mins

A Bug’s Life – 88 mins

Up -89 mins

Wall·E – 90 mins

Finding Nemo – 93 mins

Toy Story 3 – 94 mins

Monsters University – 94 mins

Cars 2 – 98 mins

Ratatouille – 103 mins

The Incredibles – 107 mins

Cars – 108 mins

Summer Wars – 114 mins

Wolf Children – 117 mins

Spirited Away – 125 mins

Paprika – 90 mins

Totoro – 86 mins

Ponyo – 101 mins

Your Name – 106 mins

From Up On Poppy Hill – 91 mins

My comparisons aren’t perfect, because ‘animated’ doesn’t mean ‘for kids’ in Japan. Summer Wars is more for an adult audience despite being anime, in line with Miyazaki’s From Up On Poppy Hill, whereas all of the Pixar films are made solidly for kids despite humour that only their adult co-viewers would get. Totoro is Japanese anime made solidly for kids, making for a better Pixar comparison, and Totor’s runtime lines up nicely with the films of Pixar. My wider point is: A more diverse story structure is accepted by audiences in Japan, with younger audiences enjoying films of ‘adult length’. (Spirited Away is enjoyed by children, but you won’t see a Pixar film of 125 minutes.)

Why are some Japanese films much longer? Because they are ‘slower’. By ‘slower’ I mean there tends to be more emphasis on scene-setting. Hayao Miyazaki is well-known for his emphasis on food scenes. Food is important across all children’s literature from any part of the world, but the emphasis on food preparation and the sharing and consumption of food is not something you’ll find easily in the West.

However, emphasis on food culture is not specific to Miyazaki. Keep looking and you’ll find it holds true across all aspects of Japanese entertainment. It’s true of Yotsuba&!, too.

The word ‘pillow shot’ was first used to describe the films of Yasujiro Ozu:

A “pillow shot” is a cutaway, for no obvious narrative reason, to a visual element, often a landscape or an empty room, that is held for a significant time (five or six seconds). It can be at the start of a scene or during a scene.

Dangerous Minds

Although it describes film, I like to apply the word equally to stories comprising static images (e.g. manga) because all the Yotsuba&! shots of first waking up, slurping on food, announcing one’s intention to visit the toilet… these are the quotidian aspects of life more commonly omitted from Western stories, even in stories for children:

My Japanese teacher in Japan also taught English to Japanese students (that was her main job). She always found it uniquely Japanese that when asked to write an essay about their daily, her Japanese students would include details English speaking students would not: “I got up, went to the toilet, brushed my teeth…”

I have concluded over time that Japanese natives do a better, more thorough job of noticing the details of everyday life, and this is reflected in entertainment coming out of Japan.

In Sum

As you can probably gather, I have mixed feelings about the Yotsuba&! series as a middle grade text. Yotsuba as a character is a satisfying character for girls in particular — she’s irreverent (especially by Japanese standards of politeness), she’s energetic and her family situation means she’s often out on interesting hi jinx. Yotsuba herself is not sexualised — in fact she’s dressed in hardy shorts and is wholly unlimited by cultural gender expectations.

All of these wonderful things about Yotsuba are undermined by the dynamic between Yotsuba’s young, adoptive father, the father’s creepy best friend and the triad of teenaged sisters next door. I believe the creator has been influenced by manga culture to the point where he perhaps doesn’t even realise this dynamic could be read as anything other than innocent.

I suspect a proportion of Japanese parents would share this view in common with me, and to finish off, I’d like to emphasise that ‘manga’ culture is not synonymous with ‘Japanese culture’.