“The Voyage” is a short story by Katherine Mansfield, written 1921. Find it in The Garden Party collection.

Katherine Mansfield always disliked intellectualism and aestheticism (one thing she had in common with her husband John Middleton Murray). She strove to combine a realist way of writing with personal and relatable symbols.

“The Voyage” is a good example of her philosophy on that. This is one of Katherine Mansfield’s later stories and was published only after her death, in her 1923 collection The Garden Party. (She died in January of that year.)

Mansfield’s technique can be called impressionist, a term borrowed from art world. (“Impressionist” generally describes the way 19th century painters depicted sensory impressions.) Mansfield mainly aimed to offer the reader a series of interconnected experiences. It’s often said there’s no ‘point’ to her stories other than that. It’s true that Mansfield’s stories were without didacticism (morals). We’re used to that now. It was unusual at the time.

It’s easy to forget how avant garde Mansfield was. You’ll have seen a lot of modernist, impressionist work since Mansfield’s time, and in fact, series of montages with none of the 19th century padding is now the storytelling norm. So I’d like to really emphasise that Mansfield’s impressionistic way of writing was a very new technique back in the 1920s. Katherine Mansfield was part of a movement, and made an important contribution to the development of the short story genre in particular.

Scholars are sometimes keen to point out that Mansfield’s short stories had ‘no plot’, either, comprising nothing but a series of quotidian snippets. Think of the montage technique in film and you’ve got the idea.

I disagree with the view that Mansfield’s short stories are without plot. Her stories are lyrical, but still adhere to conventional storytelling structure, which I’ll show you below.

What Happens In “The Voyage”

A girl of about five (Fenella) travels from Wellington with her grandmother by boat to her grandparents’ home in Picton, where she will live with the grandmother and grandfather. Her mother has passed away and her grandmother now takes care of her as her guardian. It is only halfway through the story when we discover Fenella’s mother is dead, hence the grandmother as new guardian. This information is revealed via imagery rather than via the narration, which emulates the way we learn things as children, before language and explanations even make much sense. It’s likely that Fenella has already been told in words exactly what’s happening, but she cannot really understand her new situation — or her mother’s death — until she feels it.

Setting of “The Voyage”

In the opening sentence we know where this story is set. Picton is a small town at the top of the South Island of New Zealand.

Is it time for Picton to have the conversation about changing its name? from The Spinoff. (The gateway to the South Island is named after a notorious slave trader who tortured a 13-year-old girl.)

If you want to travel between the North and South Islands, that’s where you catch the ferry, which takes you to the capital of Wellington, where Mansfield grew up. Historians and Mansfield’s contemporary readers would know the characters on the Picton side of the trip because of the landing stage:

‘And now the landing stage came out to meet them. Slowly it swam towards the Picton boat.’

Mansfield was very familiar with the Picton Boat. As a child she visited her Picton relatives many times with her family, and the Picton relatives came often to visit her.

It’s difficult to imagine now, just how dark it was before street lighting. The buildings ‘all seemed carved out of solid darkness’. The area around the Old Wharf is brought to life, with words like ‘quivering’, and the description of how it ‘burns softly, as if for itself’.

Why? Candles are used not only to light spaces but also as meditations. We have a tradition of lighting candles to remember dead loved ones. This is Fenella burning a candle for her early childhood life. We don’t know this yet — this is all foreshadowing.

This was an era when it was believed fathers were incapable of bringing up their own children. I’m sure a few did, but it was just as acceptable to give children to other female relatives if the children’s mother had died. The father walks in ‘quick, nervous’ strides. We’re not encouraged to take a good look into the father’s psychology, but it must have been terrible to lose a wife and then to lose your child, via nothing other than social circumstance.

A Brief History Of The Picton Boat

If you’d like a painterly view of the Ferry in Wellington in 1910, check out this painting by Sean Garwood, called “The Duchess”.

These days it’s common to take a flight between islands, but of course back in Mansfield’s era, the ferry was your only choice.

Now, a large proportion of the passengers will be travelling by ferry mainly for the tourist experience. The view of the mountains as you sail close to land is magnificent. And if you’re not sick to the stomach from choppy waters, it’s even more magnificent! The Cook Strait is a strip of water above a major network of fault lines — hence New Zealand is chopped in two in the first place!

The ‘Picton Boat’ known in my childhood as the ‘Picton Ferry’ is now called The Interislander, and the journey takes between 3-3/5 hours. But in the early 1900s, this boat trip between islands lasted an entire day. Back then, a trip between islands (a strip of water known as The Cook Strait) was more drama than a trip to Australia is today. Apart from the boat trip itself, you had to make it to the Old Wharf in Wellington, probably by horse and cart, and you couldn’t pay to just leave your horse there. You had to be dropped off. Today, travelling between islands is simple. To call it a ‘voyage’ would be hyperbole. But not for young Fenella, and not back then.

Other Setting Details

Without knowing anything else about the story, the reader can deduce the early 1900s setting of “The Voyage”:

- They use the old British style currency (shilling, tuppence). New Zealand switched to dollars and cents in 1967.

- Fenella’s grandmother wears restrictive clothing such as stays and bodice. Adults are wearing bonnets and caps in public. Even my mother, who grew up in the 1950s and 1960s, was required to wear a hat in public. Straw hats were part of her public school uniform. The social revolution of the late 1960s meant people no longer regarded it ‘improper’ to leave the house without wearing a hat. ‘To her surprise Fenella saw her father take off his hat.’

- The language used by the characters feels dated at times e.g. ‘what wickedness’.

- Bananas were a luxury product in this era. You couldn’t get them just anywhere, but Picton wharf was one place known for bananas. Unlike Australia, New Zealand’s climate has never been able to support its own banana growing industry. Even so, bananas are cheaply available now. They’re grown in the Phillipines and imported. New Zealand’s cheap bananas have huge ethical implications because the people who grow them are working under slave conditions. When I lived in London in 2006, I noticed Londoners had the option of buying ‘regular’ bananas or ‘fair trade’ bananas. There was never that option in New Zealand and I’d never given much thought to where bananas came from. Ethical bananas have since become an option for New Zealanders who still want to eat bananas.

- We know the grandmother doesn’t drink alcohol because the staff know her and therefore now it’s hopeless offering. Then she eats wine biscuits, and I realised that’s a word I haven’t heard in a very long time. I grew up in the 1980s with Griffins biscuits, and wine biscuits describe a sweet, plain biscuit with a complicated imprint of grapes on one side. I must have eaten thousands of those. Did they originally have something to do with wine? Probably, given the grapes. Griffins has rebranded them as ‘Superwine’ biscuits. I don’t know what the Picton Boat offerings looked like, and I can’t find a single image of a single Superwine biscuit on the entire Internet! In any case, Grandma was eating a plain, sweet biscuit, probably to settle her stomach.

- I’ve never booked a cabin on the Interislander. I have slept literally underneath the seats in the main area, on a midnight trip… after having missed my daytime one. According to one reviewer who booked a cabin in 2015: For $40 extra we had our own 4 bunk cabin on the Interislander. It had lovely white sheets, a window, our own shower and toilet. Two free cups of coffee and a newspaper thrown in! It was excellent and well worth the money.’ — Paula from Christchurch

For more on the historical era and the setting around the Old Wharf, see this post by Julie Kennedy.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “THE VOYAGE”

SHORTCOMING

When the child is a main character, their biggest shortcoming is their naivety and their reliance upon those around them.

Mansfield never lets readers know the exact age of Fenella, but we can guess she is a young child because of the limited understanding she has of different situations.

Mansfield writes this story in free, indirect discourse. Another story written with this narration is What Maisie Knew by Henry James, a description of a divorce but via the limited understanding of a girl about Fenella’s age.

When the audience knows something the character does not, this is a technique known as dramatic irony. Irony describes any sort of ‘meaningful gap’ in a story — in this case between audience and character.

Examples of dramatic irony:

- The woodpile is described as a “huge black mushroom”, an image that would perhaps be unusual from an adult’s point of view, but completely understandable from a child’s.

- In the middle of the story Fenella is in the private cabin with her grandmother. In wonder, Fenella sees the old woman undress. Until then she had hardly ever seen her grandmother with even her head uncovered. Because this is new and strange to Fenella. We know this is through the Fenella-filter because Fenella does not know the right words to describe women’s clothing: ‘Then she undid her bodice, and something under that, and something else under that.’ This is Fenella’s introduction to what it would be like to have a woman’s body.

- Fenella doesn’t know why Grandma thinks selling sandwiches for twopence is such ‘wickedness’. She doesn’t understand the value of money.

- Also, it is the first time Fenella makes this trip. We can also tell from the images — Fenella’s impressions — the narrator uses to describe the public area on the boat that everything is new to the girl: ‘They were in the saloon. It was glaring bright and stifling; the air smelled of paint and burnt chop-bones and india-rubber.’ An experienced traveler would no longer register this strangeness, but children — in common with adults on psychedelics — notice every new detail around them.

DESIRE

Fenella is a typical child, and small children tend to live in the moment. She’s not fully aware of the significance of this journey and she may not even know where they’re going. She doesn’t know how long she’ll be away from her father.

For this reason, her desires are very much in the moment.

- She wants to take care of her grandmother’s fetching umbrella.

- She wants to touch the sandwich, so she does. (She wants to eat it, too, but it’s too expensive.)

- She wants to take off her lace booties.

- She wants the soap to lather up, though it doesn’t.

OPPONENT

GRANDMA

Sometimes in a story populated by two people, they are each other’s opposition.

Definition of opponent: Any character who stands in the way of what the main character wants.

It’s irrelevant how kind the opponent is. In this story, grandmother is a caring, kind woman. The way in which she deals with Fenella belies her personality – she tells Fenella she would be more comfortable taking her lace socks off, though doesn’t insist that she do so. She reminds me a lot of my own grandmother.

Yet this loving grandmother is still Fenella’s opponent, because Fenella is a little anxious, and the grandmother is requiring her to do something she’d really prefer not to. The grandmother is taking her away from everything she knew and loved. To a child, who has not yet developed the meaning of permanence, a dead parent might come back at any stage.

The other opponent is that of nature — the inherent danger — or the sense of danger — which attends boat travel.

Grandma tells Fenella that ‘God is with you at sea more than he is on land’, betraying her nervousness, and the possibility of disaster.

The grandmother’s fears aren’t wholly imagined. The most notorious of New Zealand’s ferry disasters is the Wahine Disaster of 1968. My father was living and working in central Wellington at that time. He describes the wind as so strong that day that for a smaller individual it was impossible to stand upright outside. He remembers office workers on their hands and knees, trying to cross the street. 53 people lost their lives. The unbelievable part of it was, the ship was so very close to shore.

The Wahine was not New Zealand’s first maritime disaster. Shipwrecks were common in the 1800s, when this grandmother grew up, and as for this particular route:

On 12 February 1909 the Penguin struck a rock (Maybe Thoms Rock or the floating remains of a wreck) off the Wellington coast of Cook Strait and foundered with the loss of 75 lives. Katherine Mansfield left New Zealand in July 1908 so it is possible to speculate that if the Beauchamp family had been on the boat New Zealand might have lost its best known writer. She would certainly have been upset about this incident when she heard about it in England.

Julie Kennedy

When Grandma and Fenella first go into the cabin, Fenella feels she has been ‘shut into a box’ with Grandma. The ‘box’ refers equally to a coffin. Mansfield probably thought of coffins whenever she entered small rooms — she uses that same imagery with the same reference in her story “Miss Brill“, who returns to her small bedsit after a visit to a public garden, in which she realises for the first time that she’s old. (I wonder if Mansfield suffered a little from claustrophobia.)

In any case, when Fenella thinks of grandma, she thinks of death. If they’re both in the coffin-like cabin together, they’re both adjacent to death, together. But then Mansfield juxtaposes this vision of grandma as one-foot-in-the-grave by making her climb nimbly up the ladder to the top bunk. Though this is a juxtaposed image of the elderly woman (who probably wasn’t all that old, given the era — she was probably in her forties, dammit), the story function is the same and therefore reinforces the idea that though Fenella is at one end of her life and grandma is at the other, they are both equal: they are both mortal. They will both die, and whenever that is? That doesn’t matter. It can happen at any time, as it happened to her mother.

If grandmother is an opponent, it’s because she is positioned as Fenella’s older version of herself. Fenella is therefore unable to get away from the concept of mortality.

Mansfield is drawing on a long history of the elder-care in this story, especially upon the history of old women. European fairytales are a good place to look for the contradictory feelings people have always held in regards to the sick, frail and elderly. On the one hand, old people have been given special status and privilege as founts of wisdom. By the same token, once a person becomes senile and can no longer contribute to family and society, they are pushed from this position of honour. In the medieval era, the elderly were oft-times executed or abandoned. Death is often considered a good thing, especially when compared to being old here on earth. When dies and joins her grandmother in Heaven, this is considered a happy ending.

THE LITTLE BOY

The little boy in “The Voyage” functions as more of a foil character than of outright opposition. His circumstances are the inverse of Fenella’s: Fenella’s grandmother is kind to her, but the little boy is jerked angrily along between two parents. Note that he has his parents, so is technically more lucky. But what if your parents are angry types?

PLAN

The plan is made by the adults and Fenella has no choice but to go along with it. That’s the typical case for a naive child character.

BIG STRUGGLE

The ‘big struggle’ scene isn’t any sort of argument or fight but rather conveyed through an imagistic system of light and dark. (See below.)

ANAGNORISIS

Now’s a good time to talk about the imagery, which links directly to Fenella’s Anagnorisis.

LIGHT AND DARK IMAGERY

There are two themes symbolised by the contrast between darkness and light. First of all, complete the following chart using quotes and examples from the text.

| IMAGES OF DARKNESS | IMAGES OF LIGHT |

| The old wharf is ‘dark, very dark’. (Everything on the “Old Wharf” is dark, and the one lantern with its timid light only seems to underline that sensation.) | ‘The lamp was still burning, but night was over’ (Describes the morning they arrive in Picton to Fenella’s new life). |

| Woodpile looks like a ‘huge black mushroom’. | ‘the cold pale sky was the same colour as the cold pale sea. On land a white mist rose and fell’. |

| grandmother is wearing black clothes ‘crackling black ulster’ | Grandma’s cheeks are ‘white waxen’. |

| Little boy has black arms and legs | ‘up a little path of round white pebbles’ |

| Wool shed has a trail of smoke | On the table at Grandma and Grandpa’s sits a ‘white cat’. |

| A ‘huge coil of dark rope’ on the ferry | Grandpa has a ‘white tuft’ on his head and a ‘long silver beard’. |

| ‘Dark figures of men lounged against the (ferry) rails’. | |

| The ‘dark round eye’ is the window in the cabin on the ferry | |

| ‘spider-like steps’ of Grandma climbing the bunk |

This darkness/light imagery symbolizes:

1. TRANSITION FROM EARLY CHILDHOOD TO CHILDHOOD

There’s a point in our childhoods when we understand the concept of death. Until that moment, we believed everyone lives forever. The death of her mother forces Fenella to confront this fact earlier than she otherwise would have.

In a different story, “The Wind Blows”, Katherine Mansfield uses a ship in the distance to symbolise the later developmental phase — that of a teenager: The realisation that childhood comes to an end. This can feel like a kind of death (in hindsight more than at the time, I think).

2. LIFE AND DEATH

The sense of darkness may illustrate both Fenella’s uncertainty and her grief.

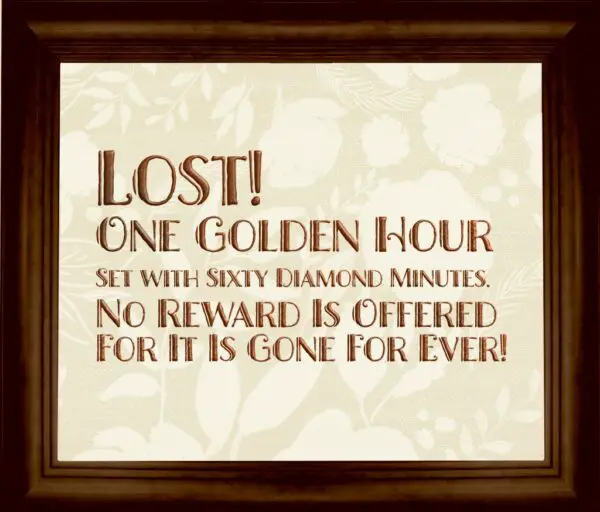

Symbolically, these images may indicate a difficult period in Fenella’s life is now behind her. Perhaps there have been years of her mother being ill, and now she has arrived in a new, stable home. (The mother might equally have died in childbirth.) However, it is implied that life will never regain the stability it seemed to have from a child’s point of view. Dealing with the death of a beloved one and becoming an adult also means getting a sense of the irrevocable passage of time. Fenella’s grandparents are obviously no longer young, and a final image, the text painted by her grandfather, underlines the awareness that life is transitory. Fortunately for Fenella, Grandpa looks very happy.

Fenella’s slight maturation over the course of a single night on the ferry is such a subtle ‘Anagnorisis’ that the reader is offered a second one, in the form of the grandmother’s painted message, affixed above the old grandfather’s head:

I wonder if this saying is a Katherine Mansfield original. It sounds like a poem that was commonly passed around, but I can’t say either way.

This story is about the inevitable passing of time — the hurtling towards death. When Katherine Mansfield wrote “The Voyage”, she had well and truly faced her own mortality. She would die just a few years later. The passing of time must have felt acute.

NEW SITUATION

The umbrella is important when making sense of the ending.

The umbrella is a repeated symbol throughout “The Voyage”, which technically makes it a motif. Fenella’s grandmother lets Fenella take care of her swan-necked, probably expensive umbrella. At first it seems a burden to Fenella as it is big and awkward (too big for her to manage — just like the notion of death). Fenella focuses on it during the trip, almost as a way of avoiding anxiety. At one point she prevents it from falling over at the same moment her grandmother does.

When they have arrived on the island, Grandma does not even have to say the word or Fenella can confirm she has performed her duty:

“You’ve got my—”

‘Yes, Grandma.’ Fenella showed it to her.”

The umbrella comes to symbolize Fenella’s new sense of responsibility, a process which has been accelerated because of the death of her mother. It surprises her grandfather that Fenella arrives carrying his wife’s precious novelty umbrella.

“Ugh!” said grandpa. “Her little nose is as cold as a button. What’s that she’s holding? Her grandma’s umbrella?”

We have learned, along with the grandfather, that little Fenella has grown up a little — enough to be trusted with a precious umbrella, and enough to cope with the tragic death of her mother. She’s going to be okay.