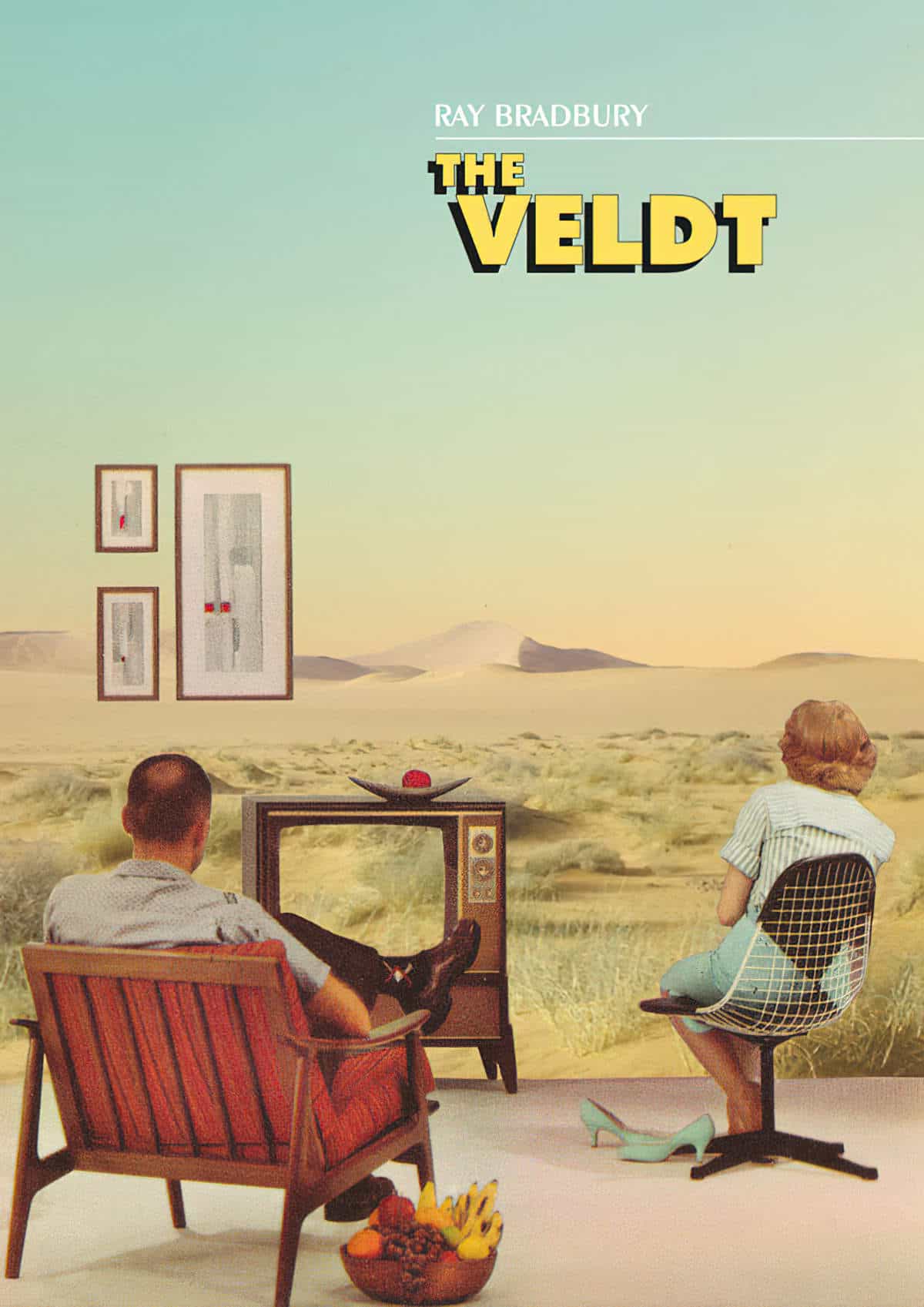

“The Veldt” (1950) is a well-known short story by American author Ray Bradbury. As I’ve seen it described: “The one where the techno wallpaper eats the parents.”

The story has entered popular culture. Take, for instance, “The Veldt”, an eight minute Canadian song by Joel Thomas Zimmerman (deadmau5) featuring Chris James.

WHERE TO LISTEN

You may be able to unearth the BBC dramatization of this short story somewhere e.g. on YouTube. “The Veldt” was broadcast 2011.

MEANING OF THE TITLE

Sometimes spelt ‘veld’, the word “veldt” comes from the Afrikaans word for ‘field’, and refers to the South African grassland. Go a little further back to proto-Germanic and you get a word which means ‘flat land’.

Now the link becomes clear: Ray Bradbury is comparing the flatness of the plain to the flatness of screens. (Screens weren’t even all that flat in Bradbury’s day. TV screens were a little curved, and definitely convexed at the back. They’re even flatter now!)

But there’s a deeper flattening which happens to these children. First their life experiences become flattened, from active participants in life to a flattened existence in which they remain infantilized, passive observers. After that, their emotional affect becomes flat. They feel nothing.

WHAT HAPPENS IN “THE VELDT”?

IMAGINING THE FUTURE

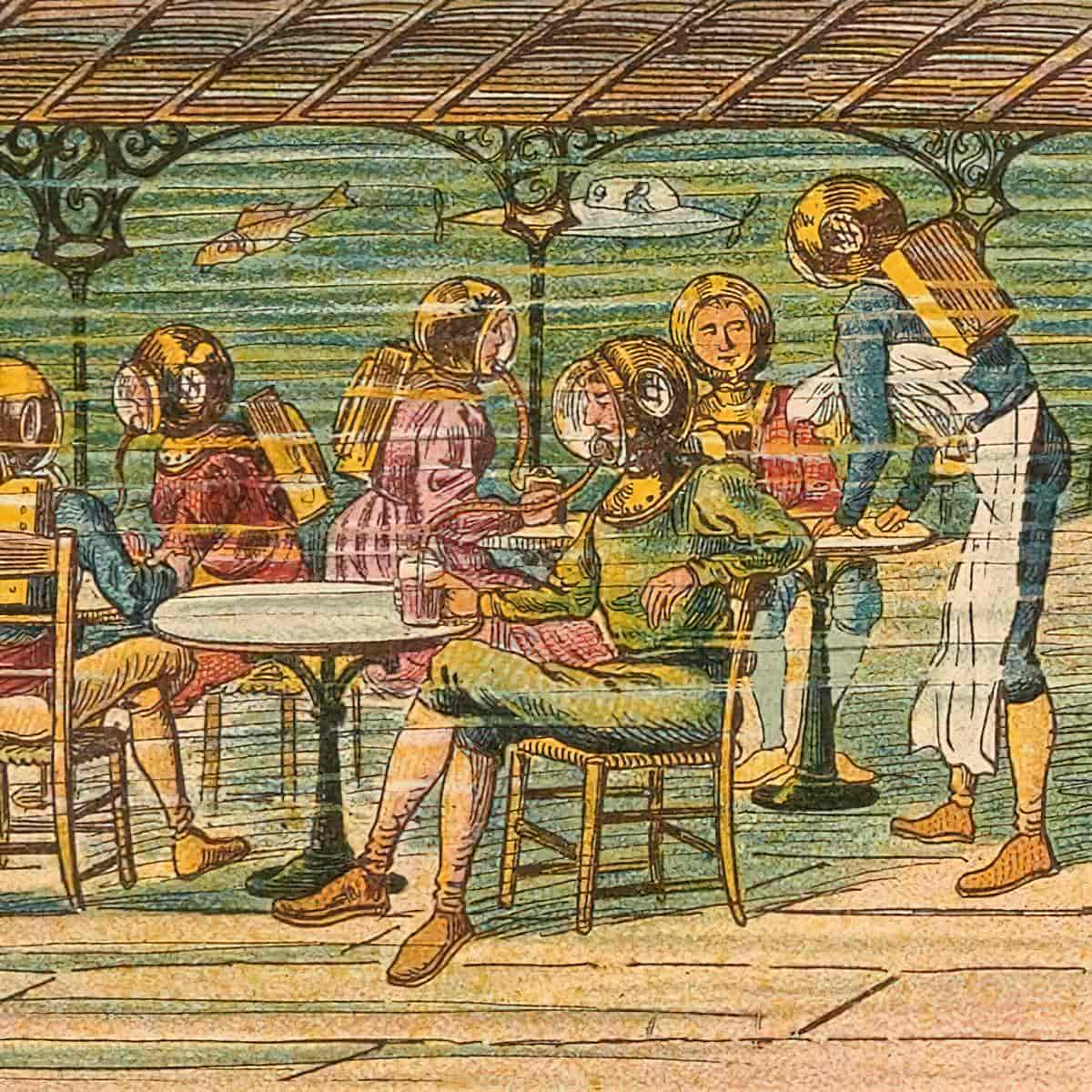

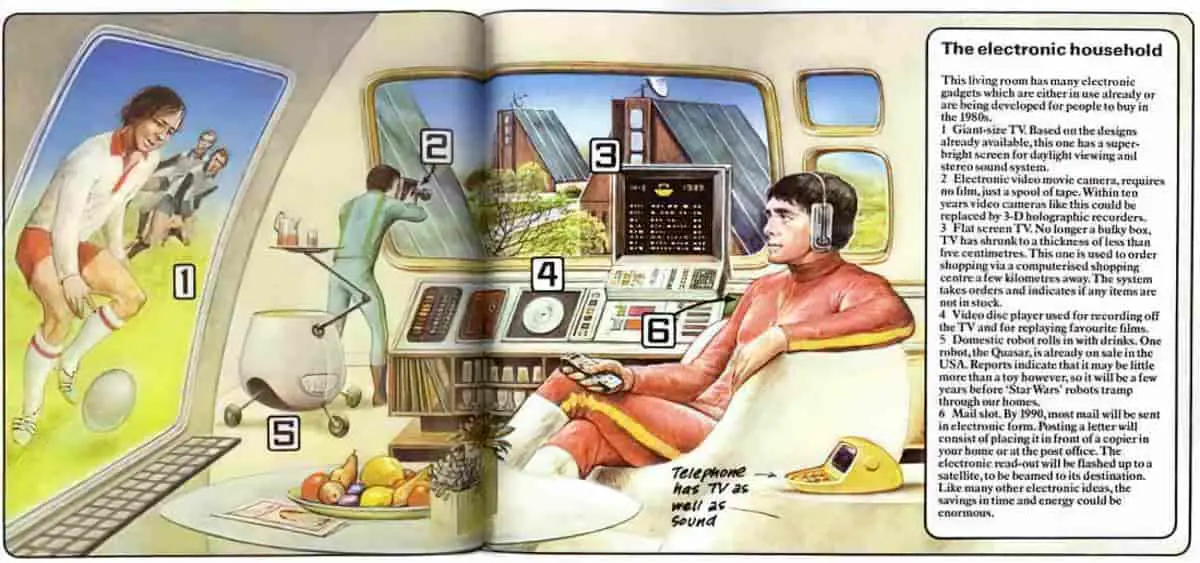

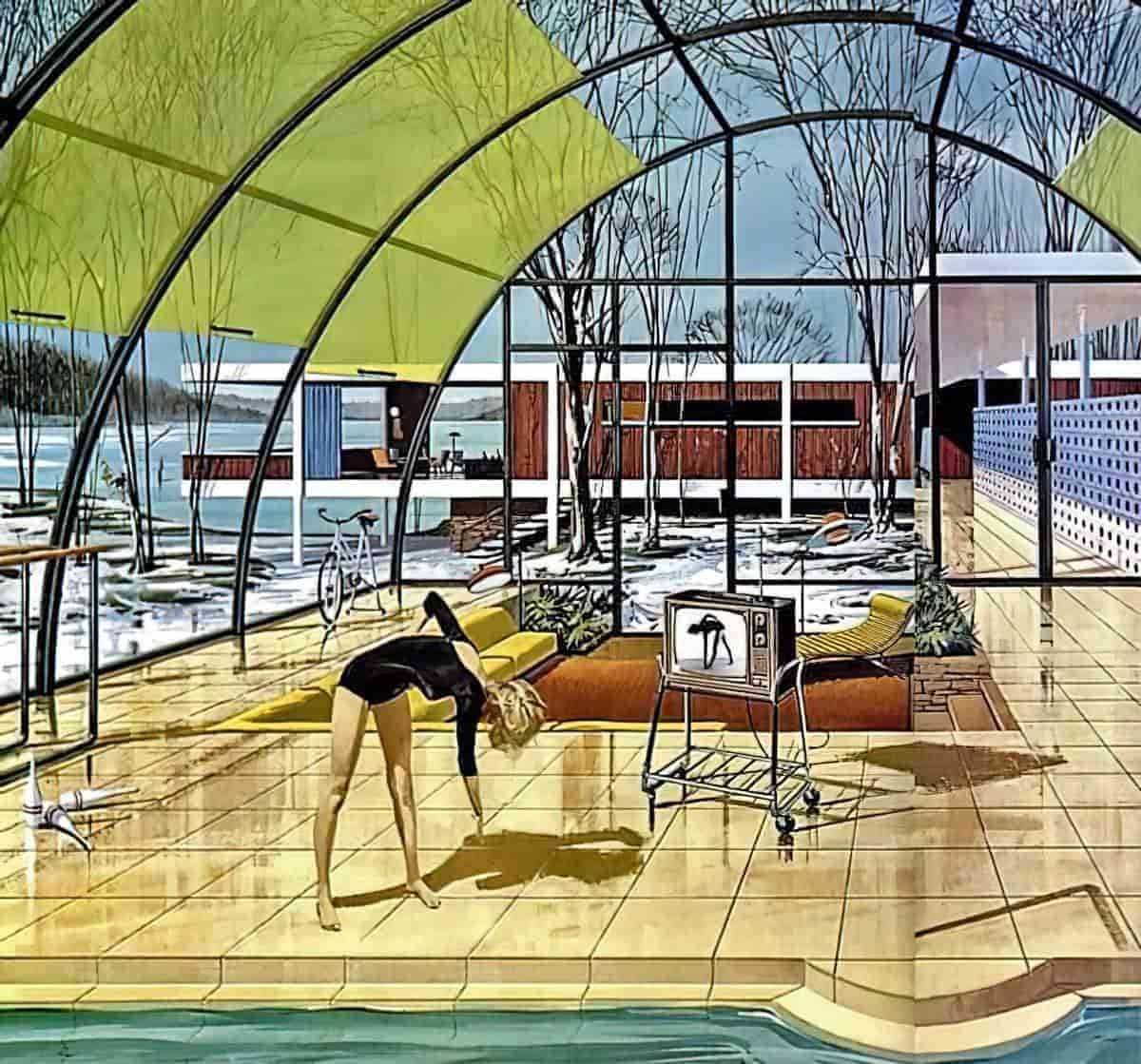

Across a number of his short stories, Ray Bradbury imagined a fully-automated house of the future. If you’ve ever seen The Jetsons, it’s a little like that, but in American suburbia. Everyone is lazy as heck. In a new-age Happylife Home, machines even tie people’s shoes.

Bradbury didn’t predict the invention of shoes which can remain permanently tied. Nike calls theirs a ‘hands free shoe’ (the Go M Flyease). These sneakers don’t have laces. They snap around your foot when you put it on. Take them off by stepping on the back of one shoe with your other foot.

When sci-fi authors envision the future, they are often mostly right, but instead of imagining a complete phase out of something, they imagine machines which replace human effort.

Overall, though, Ray Bradbury accurately predicted the Internet and wall-sized screens entering the home. He predicted the almost addictive quality of Internet entertainment. He predicted mobile phones and Facetime. The children ‘televise’ home from a carnival to tell them they won’t be home for dinner.

He did not predict the extent to which ten-year-old children lost the freedom to wander around neighbourhoods without adult supervision.

INTERTEXTUAL SETTING: A SCI-FI NURSERY

The stars of this story are brother and sister called Peter and Wendy. The name ‘Wendy’ did not exist until J.M. Barrie invented it for his play, so this is a clear intertextual reference to the story we now called Peter Pan (but which was originally called Peter and Wendy). Like these two children, Peter and Wendy spent a lot of time in a nursery. They lived in the worlds of their imaginations rather than locked within the four walls of suburban existence.

Bradbury’s nursery is a vast room with super high ceilings and screens covering the walls. This is the kind of room you need if you’ve got a VR headset, right? Otherwise you’ll be walking into the sofa when you think you’re walking into a portal.

The parents check on their children’s technology use (i.e. when they ‘check their search history’). They learn what the kids have been looking at. Lions feeding on kill.

The nasty little kids have been researching the South African veldt for a school project right? Right?! No, they appear to be obsessed with animal killings. If these kiddos are looking up gruesome things on this 1950s version of the Internet, does this mean they are…. psychologically disturbed? Should they be locked out of the VR nursery?

THE YELLOW MOTIF

Bradbury juxtaposes the futuristic tech of the nursery against a yellow motif. Yellow creates the feeling of age or rot. (Light things yellow when they age — teeth, paper.) Perhaps this ‘yellow wallpaper’ is also a nod to the famous Charlotte Perkins horror story?

And here were the lions now, fifteen feet away, so real, so feverishly and startlingly real that you could feel the prickling fur on your hand, and your mouth was stuffed with the dusty upholstery smell of their heated pelts, and the yellow of them was in your eyes like the yellow of an exquisite French tapestry, the yellows of lions and summer grass, and the sound of the matted lion lungs exhaling on the silent noontide, and the smell of meat from the panting, dripping mouths.

“The Veldt” by Ray Bradbury

Like the ‘yellowed’ environment that formed them, these kids are about to grow up fast. Into little psychopaths.

Unfortunately, the parents are a bit too late to intervene.

They do lock the VR nursery. The kids chuck a full tantrum about it. These are weird kids, though. Brother and sister hold each other’s hand. You just know when siblings get on too well, they’re cooking up a plot against their parents.

Too much tech everywhere. The wife would dearly love to go back to frying her husband’s eggs and darning his socks. Like other male sci-fi authors of his era, Ray Bradbury was unable to imagine the bit in-between, where women started to live out lives which did not revolve around men. He couldn’t imagine men would move away from handkerchiefs towards tissues, or that smoking would go completely out of fashion.

With free time, the kids go out to a ‘plastic carnival’ and have a ride in a helicopter. They won’t be back for dinner. The parents eat alone. This family has gone full kids-vs-parents now.

When the kids get home, the father asks about Africa. Peter denies seeing anything about Africa. Wendy goes into the nursery to investigate. (The father has forgotten to lock it.) She comes out having seen Rima, referring to Rima the Jungle Girl, fictional heroine of W. H. Hudson’s 1904 novel Green Mansions: A Romance of the Tropical Forest.

“The Veldt” suddenly becomes more ominous, since humans evolved on the grassy plains, which means our eyes are adapted to seeing incoming predators. But jungles terrify us, for good reason.

The father can’t sleep. He regrets not spanking them.

PLAN: CALL THE SHRINK

Lydia and George Hadley call in the psychologist. Ray Bradbury didn’t predict that child psychologists would be so hard to get in 2022. This one doesn’t even have a waiting list. His name is David McClean. A symbolic name: He’ll clean the minds of your kids. (Also a familiar brand of toothpaste. I picture a twinkling smile.)

Bradbury’s fictional psychologist tells the father (not the mother, because this isn’t women’s business) that he’s ‘never seen a fact in his life’. He deals with feelings, and he has a very bad feeling about this room.

INTERPRETATION OF AMBIGUOUS DESIGNS

The following explanation from Dr Macleans speaks to the 20th century popularity of the Rorschach test — interpretation of pictures as a way into the psyche.

Bradbury’s inverted, sci-fi spin on the Rorschach Test, in which children create rather than interpret the picture:

One of the original uses of these nurseries was so that we could study the patterns left on the walls by the child’s mind, study at our leisure, and help the child.

“The Veldt” by Ray Bradbury

Such tests were at their peak in the 1960s, but patient interpretation of ambiguous designs as personality assessment goes back to the Middle Ages. The Rorschach test was only ever supposed to diagnose schizophrenia and, despite controversy, continues to be used today by some psychologists for that purpose.

SCREEN-FREE TIME, KIDS

The parents remove all the little luxuries which have made their children’s lives easy. In fact, the father threatens to move the family out of the house. They’re going to Iowa. Even in Ray Bradbury’s future, Iowa is a backwater.

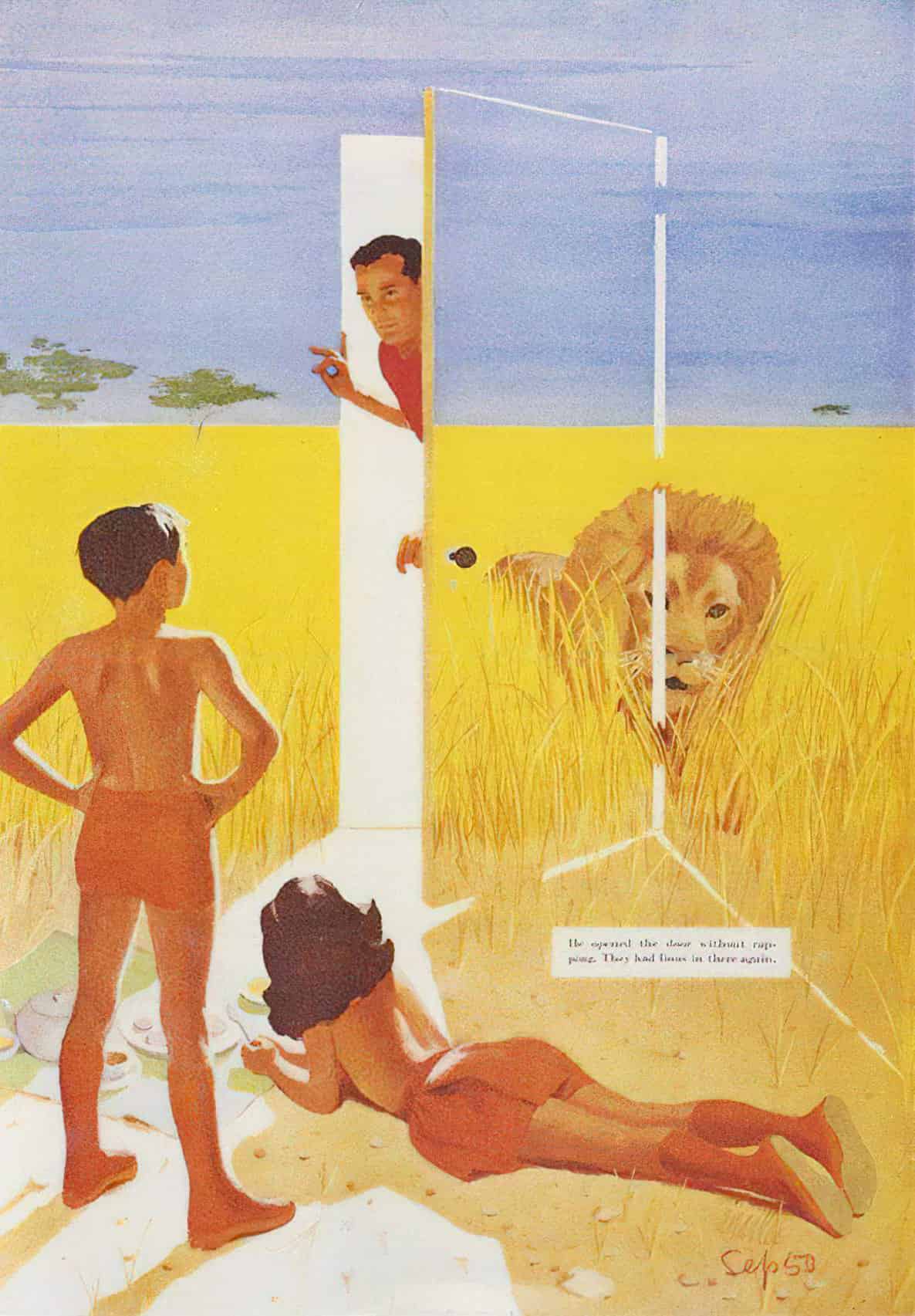

Terrified at the death of machinery and the mass grave of gadgetry that is now their house, the kids lock their parents inside the nursery.

The kids must have hacked into the system somehow. We can deduce Ray Bradbury meant it to be Peter, because Peter has a very high I.Q., mentioned earlier in passing. The lions are now real lions and with horror the parents realise they’re about to be eaten. The screams they’ve been hearing are their own.

WHAT HAPPENS AT THE END?

The little hackers have also managed to insert themselves into the veldt beyond the screens. Dr McClean turns up, hoping to offer counsel. “Where are your mother and father?” he asks, increasingly suspicious. He sees those lions feeding on something in the distance.

This sci-fi ending is Bradbury’s, but is a sci-fi take on an old trope: the Portal Picture, as TV Tropes calls it. Pictures offer a doorway into another world.

ENDURING THEMES OF “THE VELDT”

Gen Xers who studied this story in school would not have predicted how quickly Ray Bradbury’s futuristic story would happen. We were the last to grow up without the Internet and AI. But we are those parents now. The story is particularly disturbing for us, cast from the children to the parents.

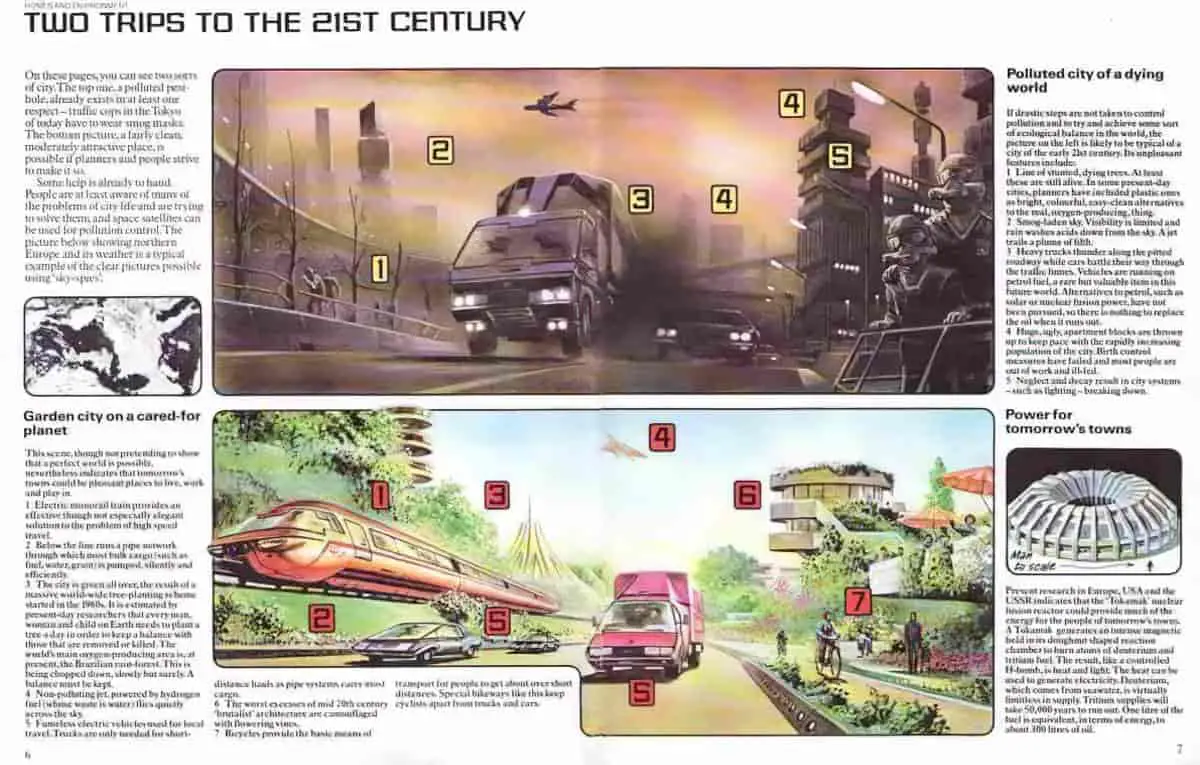

But parenting is so much harder than even Ray Bradbury imagined. Instead of a lockable room made of screens, screens are everywhere, and portable. Futurists predict that the future contains even more screens. Everything will be Smart and interactive.

For today’s parents, the Internet isn’t simply a luxury item which can be locked away, but necessary. Our kids are expected to use it to do an increasingly full load of homework. As parents of Gen Z, we are required to be more vigilant and involved than ever. The worry is that if we let our children use screens too often, the children will lack humanity. Children will become AI. They will happily, without remorse, sacrifice their very own parents for more of the virtual reality drug.

I’ve been thinking about a “Veldt” quote this year, 2022.

“I didn’t like it when you took out the picture painter last month.”

“The Veldt” by Ray Bradbury

“That’s because I wanted you to learn to paint all by yourself, son.”

FUTURISTIC HOMES

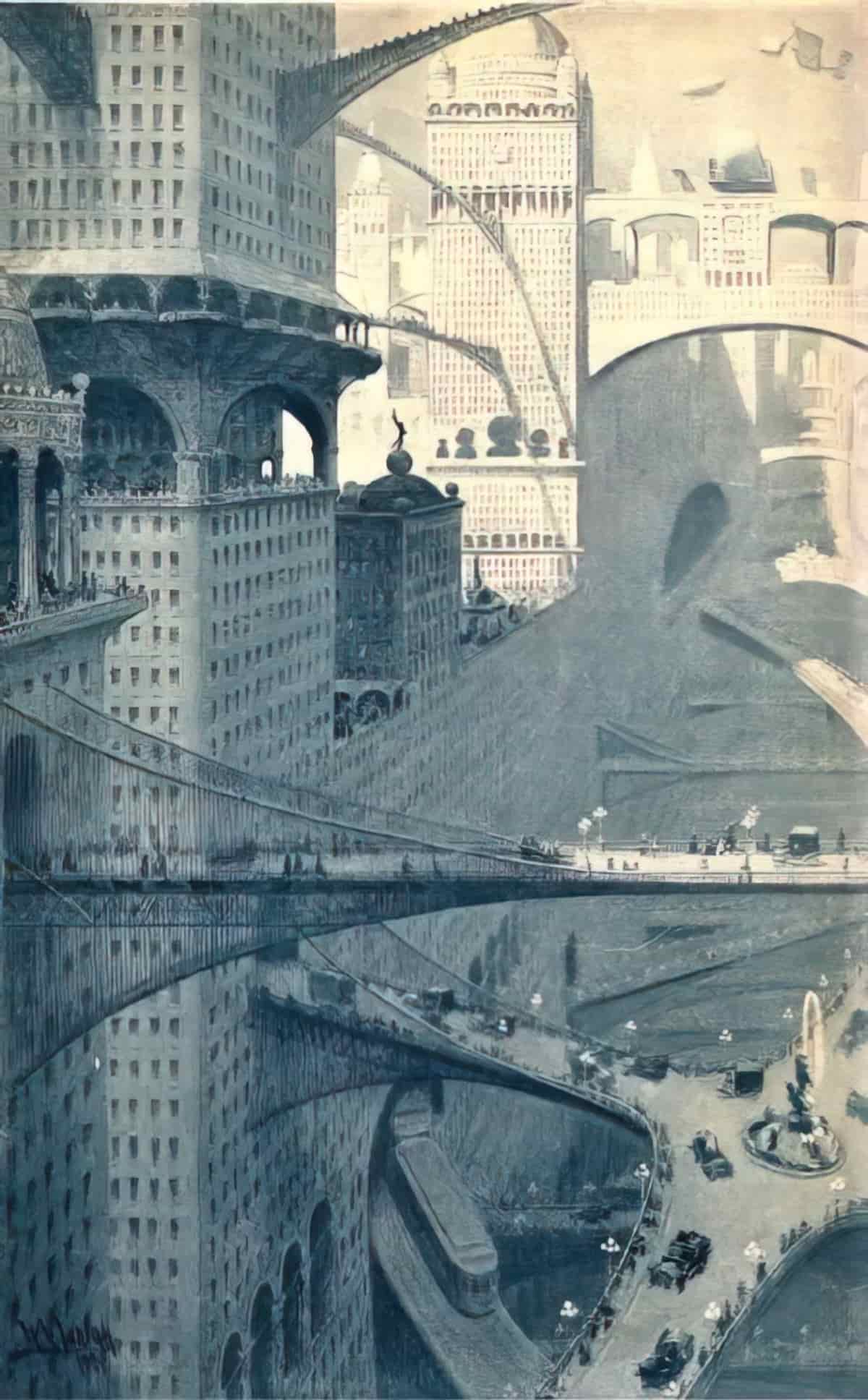

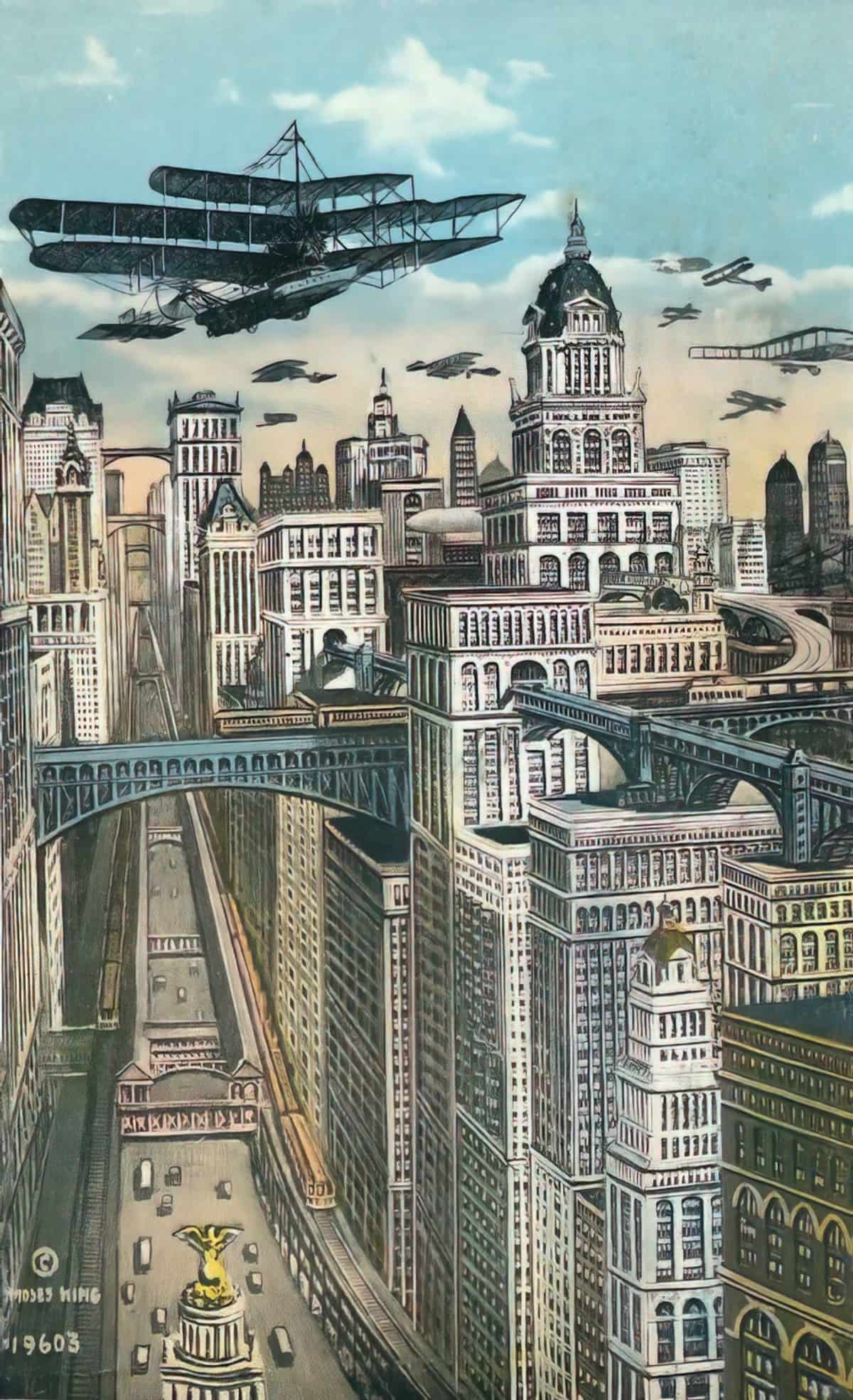

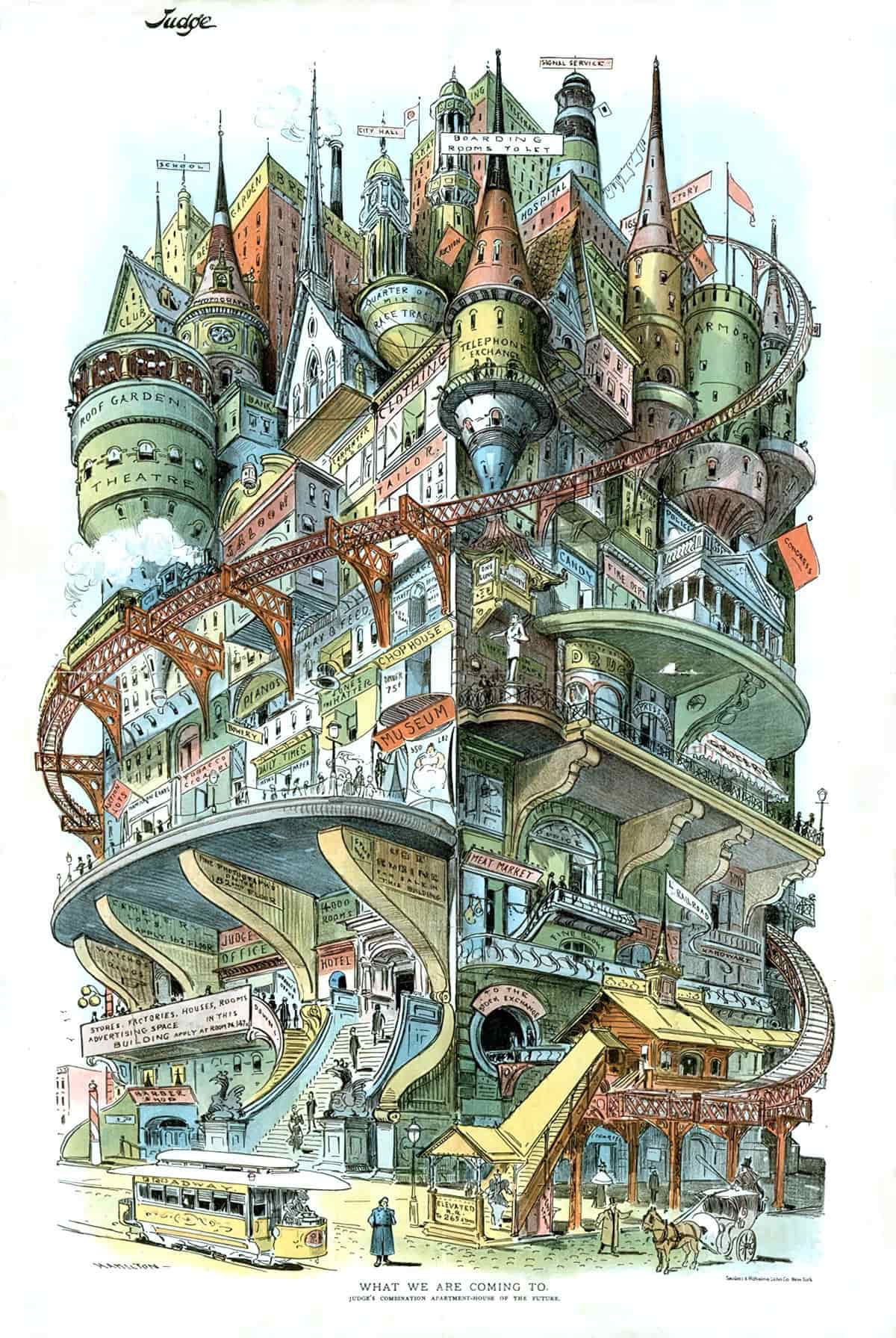

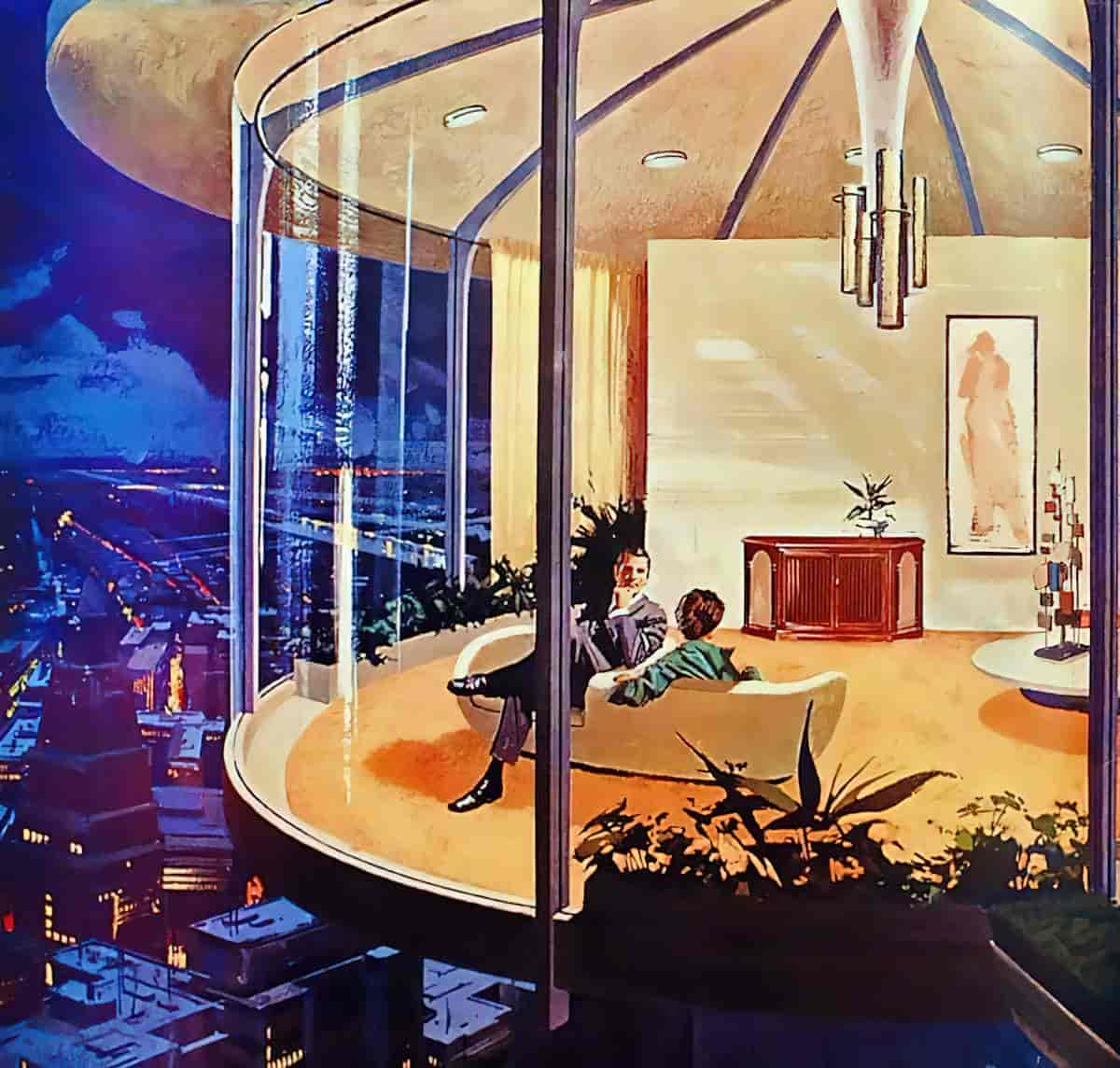

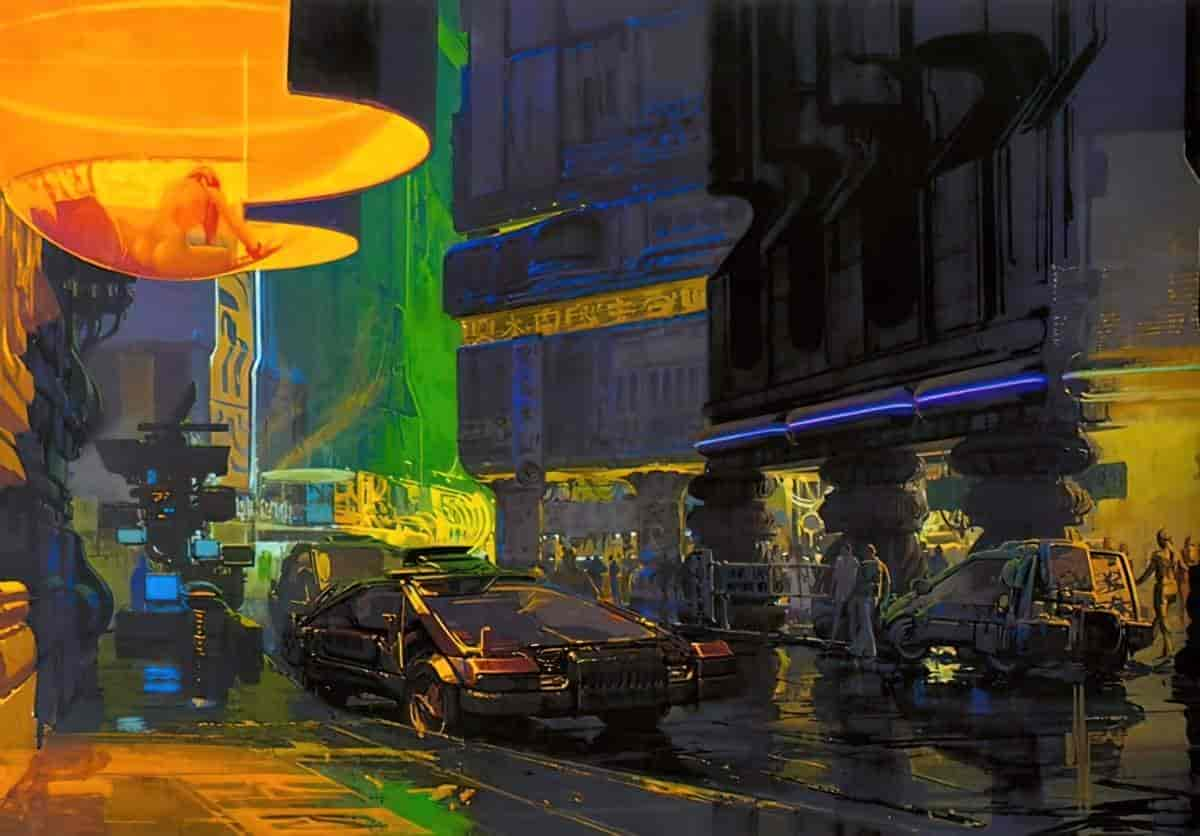

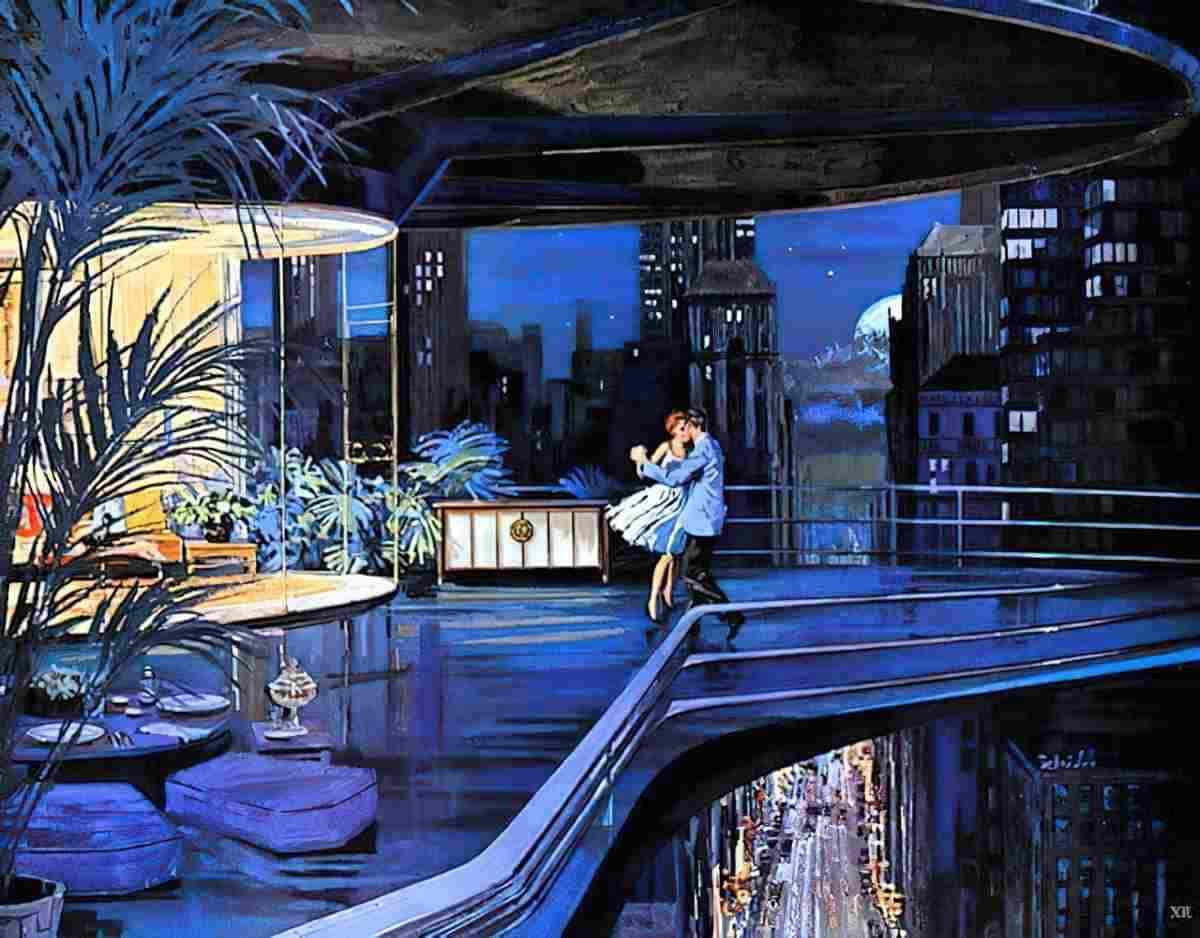

How did 19th and 20th century artists imagine the futures of cities and houses? Artists envisioned plenty of metal and glass. Both conduct heat — they were clearly imagining coldness. This has been interpreted by storytellers as emotional coldness. The symbol of the big, flash house made of glass housing emotionally distant characters endures in modern storytelling.

Ray Bradbury accurately predicted lights that turn on and off by sensor. He predicted voice activated machinery. We’re not yet at the point where we only need to ‘think’ something before it happens, but with tech so firmly integrated into our lives, our use of mobiles does, indeed, make use feel there is no intermediary between ourselves and the commands we give ‘the machines’.