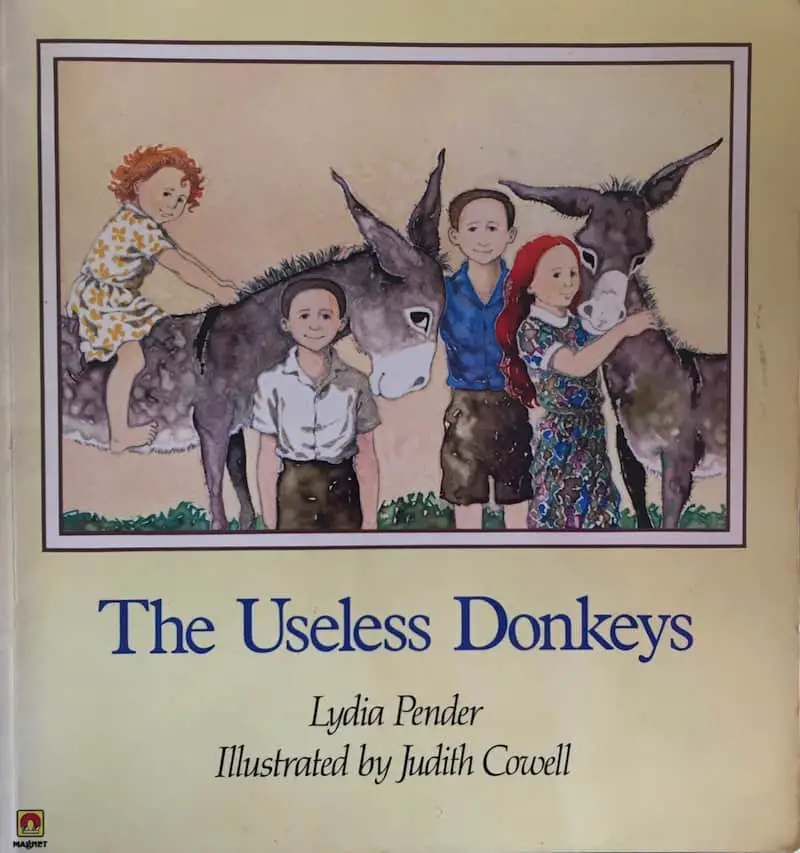

The Useless Donkeys is a 1979 picture book written by Lydia Pender and illustrated by Judith Cowell. At first I thought The Useless Donkeys was going to be a more realistic, earlier version of Walter The Farting Dog in which an adult threatens to get rid of a family pet, but over the course of the story the pet(s) prove their true worth and end up staying with the children.

I was a little off in my prediction. Instead, these donkeys are donkeys in the realistic sense. There’s nothing anthropomorphised about them at all. So they just wander around being donkeys, without ever proving their worth. Instead, the oldest daughter in this story happens upon what’s nowadays known as ‘The Benjamin Franklin Effect‘, in which the more you do for someone the better you like them.

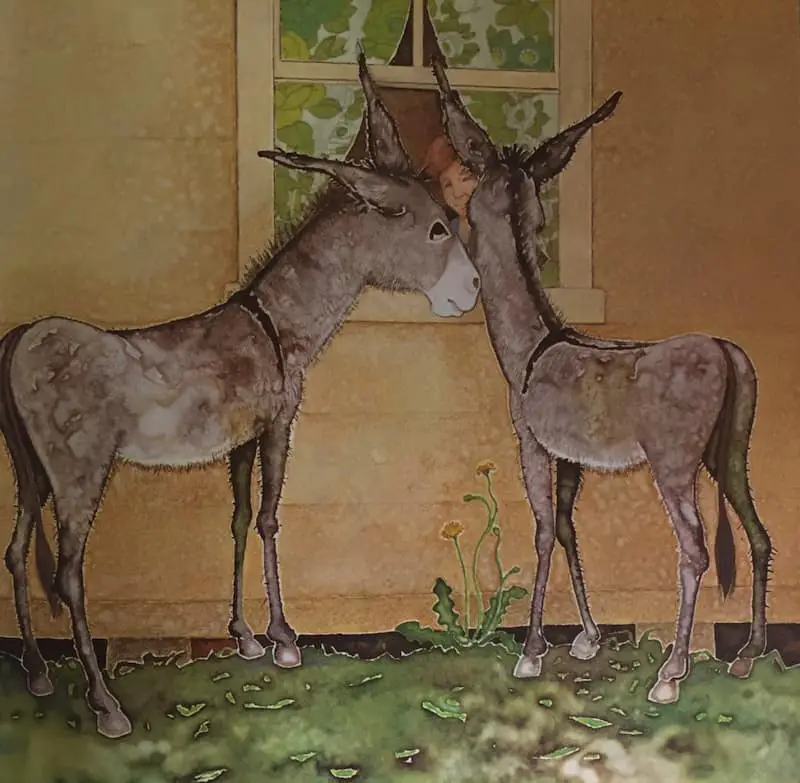

The front matter tells us the illustrator, Judith Cowell, is a perfectionist and spent two years working studiously on the watercolours of this book. As you’d expect, they’re worthy of framing.

Perhaps this is why Cowell seems to have produced only two books in her lifetime.

SETTING OF THE USELESS DONKEYS

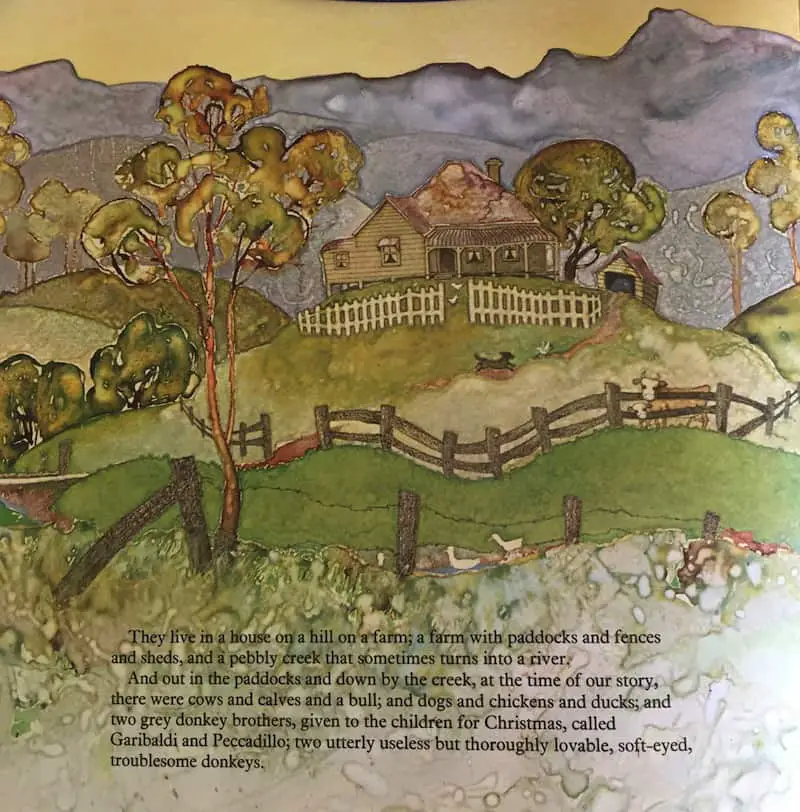

This storybook world is something between English and Australian. I couldn’t decide whether the author was Australian or English, in fact, so wasn’t surprised to look her up and find she was English born but spent most of her life in Australia.

Lydia Pender was the daughter of George Herbert and Ethel Podger. She came to Australia with her parents and four brothers in 1920. They lived in Sydney and she went to St. Albans Church of England School, Hunters Hill, completing the Leaving Certificate. Pender won a scholarship to do a bachelor of Arts at the University of Sydney but did not complete it.

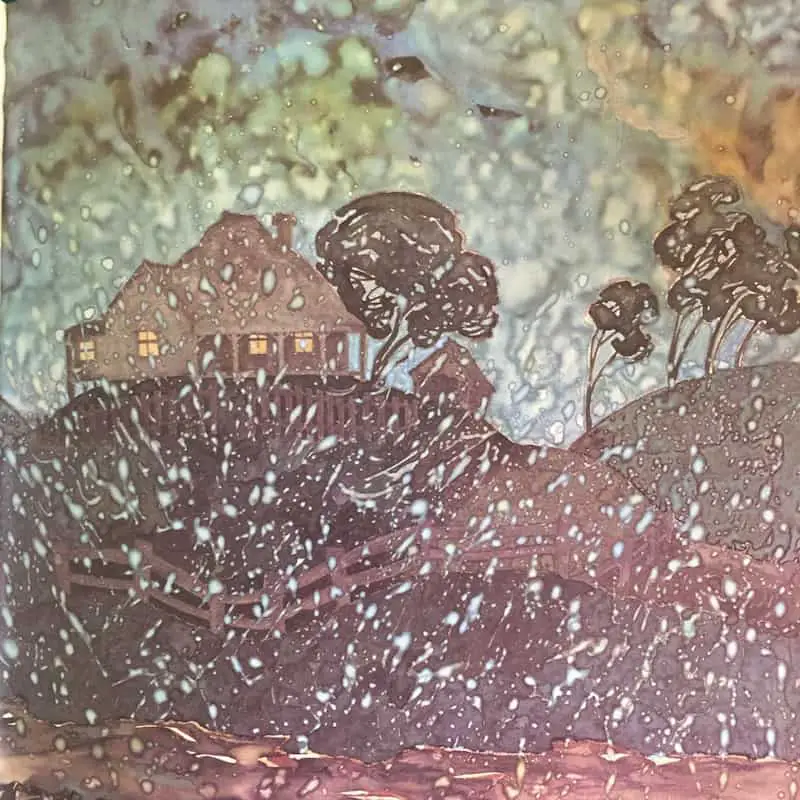

There is something quite English about the diction, and the way the full names of the children are used. Then there’s that heavy rain, of course, which is often absent from Australian picturebooks set on farms. (See for example Two Summers.)

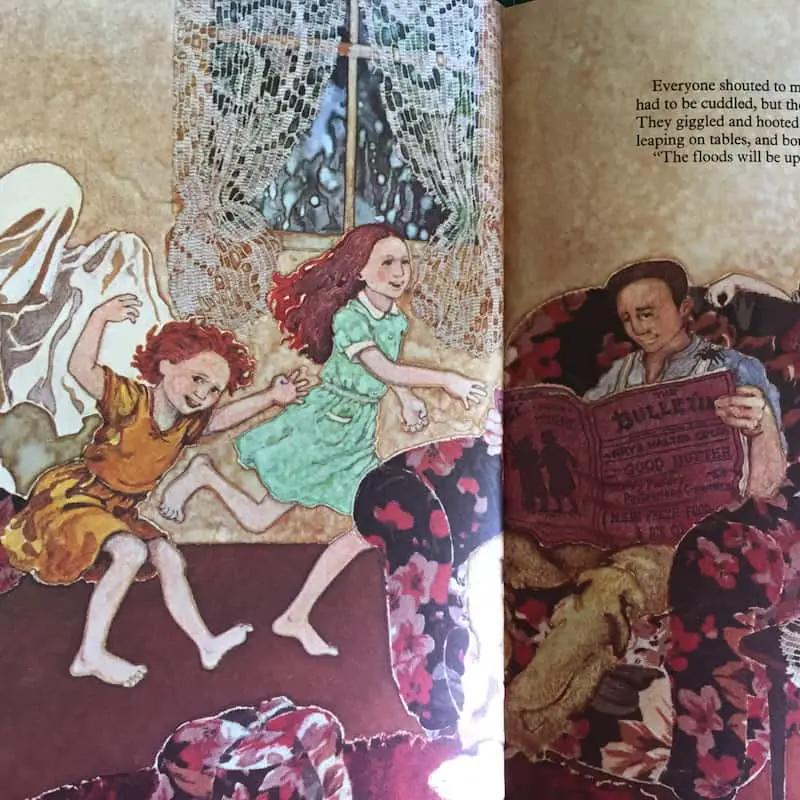

This is a cosy homestead, a small farm with a big, bustling family. The house provides safety, and the children are healthily excited about the rising river.

We have a newspaper reading father and a mother dressed as a 1940s housewife, tending to the family.

DONKEYS

Donkeys are one of the main animals in Aesop’s fables. (They’re often referred to as an ‘ass’, which has fallen out of favour for some weird reason.)

Asses, no surprise, are often depicted as hapless victim types, with no brains. They fall into traps easily, and they are drawn towards fun with no thought to consequences.

Donkeys in real life have been important to us since the age of agriculture, but only if they can be put to work. Unlike horses and ponies, donkeys in children’s literature are primarily for working rather than for companionship. Donkeys don’t save the day very often. It’s no surprise, therefore, that the donkeys in this story are actual donkeys, not people in the form of donkeys.

STORY STRUCTURE OF THE USELESS DONKEYS

SHORTCOMING

A pair of donkeys are useless and a bit annoying.

DESIRE

The mother and children want to keep the donkeys.

OPPONENT

The father. This guy is a farmer type who values animals only for their utility.

PLAN

The two eldest children row to the ‘island’ and spend the night keeping the donkeys company.

BIG STRUGGLE

The storm sequence.

A storm can symbolize the turmoil in the character’s psyche.

The Rhetoric of Character In Children’s Literature, Maria Nikolajeva

The reason for that watery watercolour technique, with those large splashes to add texture, becomes clear when it starts raining in the story and the river rises.

For more illustrations of storms, see here.

ANAGNORISIS

The more you do for somebody, the more you like them. It applies to babies and it applies to animals.

NEW SITUATION

The donkeys will be allowed to stay. We know this because the father gave the final say to the more sympathetic mother.

This part of the story is implied rather than shown.