The Turning is a 2004 short story collection by Western Australian author Tim Winton. In 2013 the collection was adapted for film. It’s unusual to find a feature-length film which is actually a series of short stories, which might partly explain the tagline on the movie poster: A Unique Cinema Event.

I really enjoyed three hours of Tim Winton stories on film, though I did watch half one evening, half the next. A few of them are more atmosphere than substance. So I decided to read the book, confident in the knowledge that some textual stories lost much of the interiority when adapted for a viewing audience.

I read the stories about two years after watching the film, so I only remember the most resonant details. Still, reading the book is an entirely different experience from watching the film. The film utilises different actors for each story. But when reading, you understand gradually how stories weave together. We see characters as children and later as adults. We might return to the same place but a generation later. Winton offers a parallactic reading experience by telling the story of a life from someone else’s point of view.

THE TURNING BY TIM WINTON

“Tim Winton’s stunning collection of connected stories is about turnings of all kinds—changes of heart, slow awakenings, nasty surprises and accidents, sudden detours, resolves made or broken.

“Brothers cease speaking to each other, husbands abandon wives and children, grown men are haunted by childhood fears. People struggle against the weight of their own history and try to reconcile themselves to their place in the world.

“With extraordinary insight and tenderness, Winton explores the demons and frailties of ordinary people whose lives are not what they had hoped.”

THE CONCEPT OF HAUNTOLOGY

This short story collection is a good example of ‘hauntology’. (Nothing to do with ghosts.)

HAUNTOLOGY: THE PERSISTENCE OF A PRESENT PAST

This is a term which comes from philosophers of history, political scientists and also from the creators of certain subgenres of electronic music (see the work of British music critic Simon Reynolds for use of ‘hauntological’ in the music world).

Jacque Derrida first used the word at a 1993 lecture. He was talking about the state of Marxist thought in the post-Communist era, but let’s not worry about that here. Since then, the word ‘hauntology’ has caught on somewhat. The present moment doesn’t exist in isolation. Every present moment is affected by our history.

For Derrida himself, hauntology is a philosophy of history that upsets the easy progression of time by proposing that the present is simultaneously haunted by the past and the future.

Berkeley Art Museum’s exhibit notes for”Hauntology”

This was an important idea for Derrida, who was conveying the idea that the spectre of Marxist utopianism haunts the present, capitalist society.

Also a part of hauntology:

- the identities of individuals are fluid and

- one person’s experience links to someone else’s

- both in the present moment

- and also across time.

As we read, we are required to make connections for ourselves. Tim Winton doesn’t make them explicit. He connects (and then does not connect) stories in sometimes surprising ways. He crosses generations. He links city to the bush. What happened in characters’ past continues to ‘haunt’ them in the present.

“BIG WORLD”

A middle-aged man looks back on his high school years. This is an odd couple story because, on the surface, Biggie Botson and the narrator have little in common. I recall the phrase: “Friends for a season, friends for a season, friends for life.” High schools are such unusual social situations that two kids can buddy up for reasons that would never endure in the post-high school world. With the benefit of hindsight, the narrator can see why he and Biggie needed each other, and also how they were bad for each other.

To be honest he’s not really my sort of bloke at all, but somehow he’s my best mate.

I got us both to the finish line but ensured that neither of us got across it. Biggie hadn’t learnt anything that he could display in an exam and I was too worn out and cocky to make sense. We fried. We’re idiots of a different species but we are both bloody idiots.

“Big World”

The narrator’s mother is an English teacher. Children of teachers (and doctors) frequently find themselves set apart from their peers when their parents work remotely. The narrator is originally from Perth. He fully expected to return, and to follow in the socioeconomic footsteps of his mother, who is university educated. But this hasn’t happened.

Me, I love the city. I’m from there originally. I really thought I’d be moving back this month. But I won’t, of course. Not after blowing my exams.

“Big World”

He assumed his fate based on the life of his parents, without accounting for the effect his environment would have. The narrator has been affected by the different socioeconomic status of rural peers around him, and by a best friend whose father beats him and who has no shared dreams for his future.

Biggie’s results were even worse than mine — he really fried — but he didn’t have his heart set on doing well; he couldn’t give a rat’s ring.

“Big World”

I feel this is a story about how home environment and social environment both play a role in how we turn out.

NARRATION

“Big World” is the story of a man’s high school years, told in retrospective first person. (That’s when a first person narrator recounts events from the past.) Here’s the thing about first person retrospective: Sometimes readers don’t know how long ago things happened. That describes my reading experience of “Big World”. We have a clue from the start, because the narrator has clearly achieved understanding of his youth via maturity. There are also contextual clues if you know how to read them: Only people of a certain age (or expertise) recognise the vintage of a V-8 Sandman or what we might expect to find on the cover of a Yes album.

Here’s the lurid palette mentioned in the story. Australia is well-known for its harsh sunlight, and bright colours — red earth, cerulean sky. Its own kind of lurid. We might say this palette is a 1970s teenaged-rock-take on the natural colours of an Australian landscape. The narrator describes the Australian sky of his youth as ‘blue as mouthwash’. Another lurid colour, and a brilliant way to keep the colour imagery going. Later, when the Kombi fries, the sky turns ‘acid blue’.

But unless you’re reading for era clues, it’s not until the final paragraph that readers realise just how much time has passed, and how many things have changed. The time between ‘story’ and ‘telling of it’ is kept as part of the reveal which is, of course, that Biggie has died.

In stories which end in death there is almost always death of some kind earlier in the story. I don’t know how this keeps working its magic without telegraphing because it’s pretty much a storytelling rule. Examples: Someone finds a dead rodent; a dead cockroach on a pantry shelf; a hearse passes someone stopped at traffic lights. If anything like that happens in a story, you can predict death of a character by the end. Foreshadowing only works if it doesn’t stick out.

Did you pick the death foreshadowing in this one? Death surrounds them at the meatworks, as they hose blood off the floors and deal with confronting animal innards.

USE OF THE SUBLIME

We forget most things from our past. But when you recall high school memories, you’ll almost certainly remember a few big moments. We tend to remember near death experiences and can sometimes recall those as if they just happened.

On death and dying: towards a new paradigm – Ven. Fabienne Pradelle interviews Dr. Peter Fenwick

(As an aside, people who sit at the far end of the (a)phantasia spectrum tend to have more issues with PTSD precisely because of their superpower to see in their mind’s eye what has happened in the past.)

In this episode of High Theory, Laura Wittman tells us about near death experiences. The central feature of these experiences is a vision and a story, which it turns out are a lot stranger than the “best seller” version. These narrative encounters with death often inspire people to make dramatic moves in search of a more meaningful life, from newfound religious faith or activist commitments to career changes and divorce.

High Theory Podcast

Like any driver — or passenger — I’ve had my share of near death experiences on the road. One in particular sticks out. I was forced onto the other side of a New Zealand highway after an oncoming car veered into my lane, heading straight for me. He subsequently crashed into a bridge over a culvert. I called emergency services and waited for them to arrive. (If you’ve never had to do this, emergency services remotely lock your phone. In NZ, they don’t have the numbers of bridges on file either, so you have to be able to tell them which part of the highway you’re on.)

The old man driver had fallen asleep. Fortunately for him, by the time he crashed into the bridge, he hadn’t been going too fast. Afterwards, I got back into my car, went to start the engine and realised the engine was still running. My hands were shaking. I continued along the highway with all senses on high alert. At some point it must have hit me that we’d almost been killed. That realisation hit my workmate passenger immediately.

But I never experienced The Sublime at any point. The narrator of “Big World” experiences a connection with something bigger than himself after his noteworthy motoring event, hence the title of the story.

I’ve seen it in someone else, though. Driving along another New Zealand highway (the South Island this time) a local man — who should’ve known better — took a corner too fast. He would have flown straight into the ravine if it hadn’t been for two young European tourists who had parked their campervan in exactly that spot to enjoy a cup of morning tea. The guy who caused the massive dent in their rented vehicle had skidded off the road due to black ice. When I briefly spoke to him, he was looking up into the sky, as if he’d just seen angels descend. (Now I’ve said ‘angel’, I realise Tim Winton has set this story in a fictional town called Angelus.)

I don’t believe that guy I met was high on that early weekday morning, but it was like talking to someone who’s on something. For him, in that moment, he was suddenly happy to be alive. (In case you’re wondering, the young tourists looked pleased to have saved someone’s life. Hopefully the insurance crowd gave them no grief.)

This experience is shared across time and cultures. The Sublime. The word has a separate, colloquial meaning these days. I think of TV chefs tucking into something delicious. “Sublime!” they say, using the word as an intensifier to describe something really, really good. (Or maybe they are just that into food?)

‘Danger’ has largely been lost in colloquial modern usage of the word ‘sublime’.

Let’s sojourn back to a more useful, targeted usage of the concept. The Sublime helps us with the gratitude of being alive by reminding us of our own mortality. The Sublime requires danger. The most reliable way to achieve that feeling of connection to something bigger than yourself is to narrowly avoid getting yourself killed. Storms are good. Lightning, thunder, flash floods etcetera. Across literature, storms are regularly utilised to transport characters (and readers) into the Sublime.

Why might Tim Winton have made use of The Sublime?

The Sublime is very useful at the Anagnorisis (epiphany) part of a story because that’s how stories are structured, across thousands of years (no point in individual authors trying to mix this up — story structure has evolved.) Fact is, epiphany happens after a battle, in which the hero (main character) almost dies (actually or metaphorically). The storyteller’s job lies in conveying to readers how the character has learned something, or in anti-epiphanies, readers learn something while characters (tragically) do not.

But aside from that extremely useful function of The Sublime as Anagnorisis, whenever a storyteller connects readers to something bigger, we’re now dealing in circles, cycles and spirals. Leave Earth, you’re looking at a round ball. (“The Overview Effect” — a.k.a. The Sublime for Astronauts.) Stay on Earth your whole life, you’re part of the Life Cycle, with grandparents and parents and perhaps children of your own. Most of us hang around long enough to see how everything links up and locks together. This feeling only intensifies as you age. Winton’s choice of retrospective first person present tense narration makes sense. This is a story told from the mature point-of-view of a middle-aged man. The Sublime is especially useful when stories cover many years of someone’s lifetime, when conjured historical memories co-exist with the present. Stories which emphasise the interconnected web of influences and interdependencies also frequently delve into themes of fate. In this story, even when writing about the past, the narrator is casting his mind forward in an example of side-shadowing: ‘Some days I can see me and Biggie out there as old codgers, anchored to the friggin place, stuck forever.’

Is this a fatalistic story, do you think? It’s strange to look back at high school peers from the distance of middle-age. Where I know the gist of what happened to school peers, I am both surprised and not surprised at all. It’s a bizarre thing. Tim Winton captures it brilliantly in “Big World”.

THE ANAGNORISIS

With Biggie and his new girlfriend in the back, and the narrator feeling angry because they’re treating him as their chauffeur, we are eventually told the real reason the narrator’s annoyed:

Something else, the thing that eats at me, is the way he’s enjoying being brighter than her, being a step ahead, feeling somehow senior and secure in himself. It’s me all over. It’s how I am with him and it’s not pretty.

“Big World”

It’s not clear whether he realises these complicated feelings in the moment, or much later. The advantage of retrospective first person narration: The narrator has had time to reflect. More complicated insights into the self (and others) therefore seem plausible.

THUMBNAIL CHARACTER DESCRIPTION

Tim Winton’s distinctly Australian voice makes for a satisfying read, grounded firmly in time and space. Unlike Winton himself, the first person narrator is not supposed to be a writerly type. I especially like his description of his mother’s lover, the deputy principal:

He’s married. He uses the school office to sell Amway. Both of them believe that Civics should be reintroduced as a compulsory course.

“Big World”

In three sentences we can picture the guy, right? We understand the hypocrisy (irony) of his so-called morality, something his economic values and what he believes a young person’s path should look like. He’s presumably cheating on his wife but still thinks young people should have morality knocked into them via a compulsory high school course. I’d be terrified for Tim Winton to describe me in three well-chosen sentences.

Writing tip: Highlight irony at every opportunity, even in three-sentence character thumbnail descriptions.

comparing humans to animals

The unappealing character Tony Macoli is compared to a rat.

I was new in town and right from the start a kid called Tony Macoli became fixated on me. He was very short with a rodent’s big eyes and narrow teeth.

“Big World”

(Do you know the name of this literary technique? There are a few. It’s not anthropomorphism — that’s the inverse, when an animal is given human characteristics.)

Tim Winton compares Tony Macoli directly to a rat by using the actual word ‘rat’, making this a simile rather than metaphor. In contrast, Roald Dahl uses the metaphorical version in his well-known short story “The Ratcatcher“.

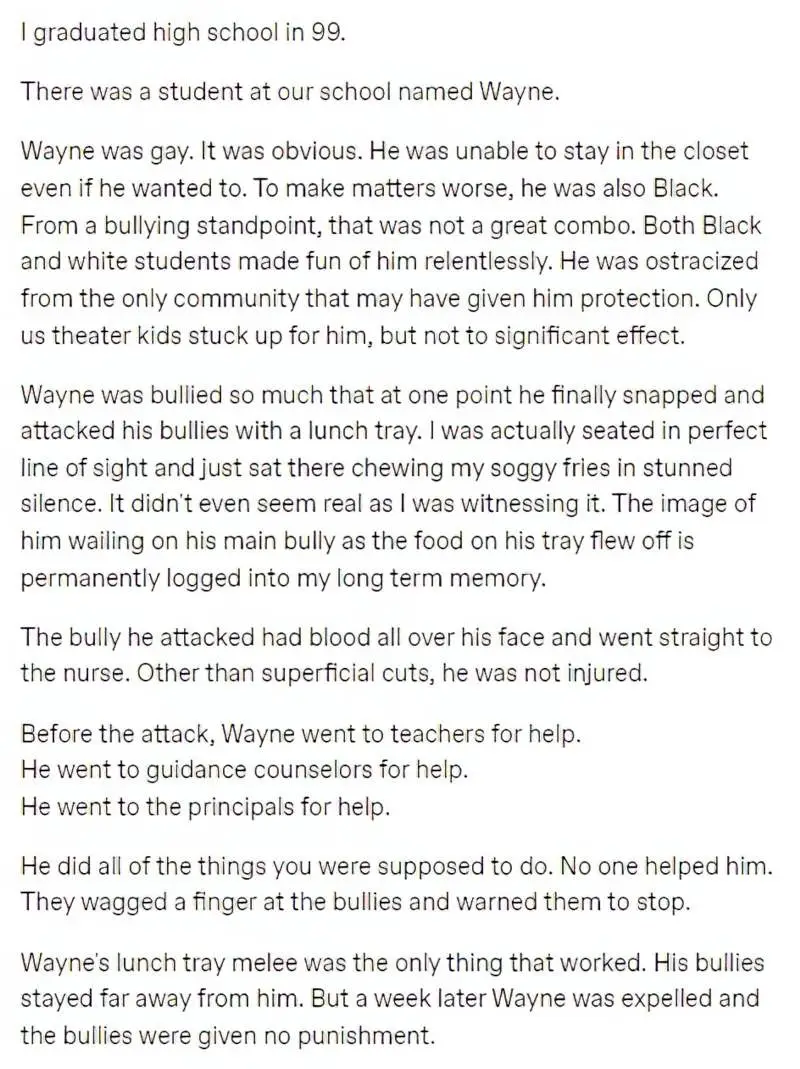

BULLYING and ‘effective violence’

Tim Winton’s description of high school life as the city newcomer feels (horribly) realistic. After a synopsis of the abuse:

The little bastard kept at me but I didn’t touch him. After a week I didn’t even react. I wasn’t scared. It wasn’t passive resistance or anything. I just got all weird and listless. I reckon I was depressed. But the less I responded the more Tony Macoli paid me out.

“Big World”

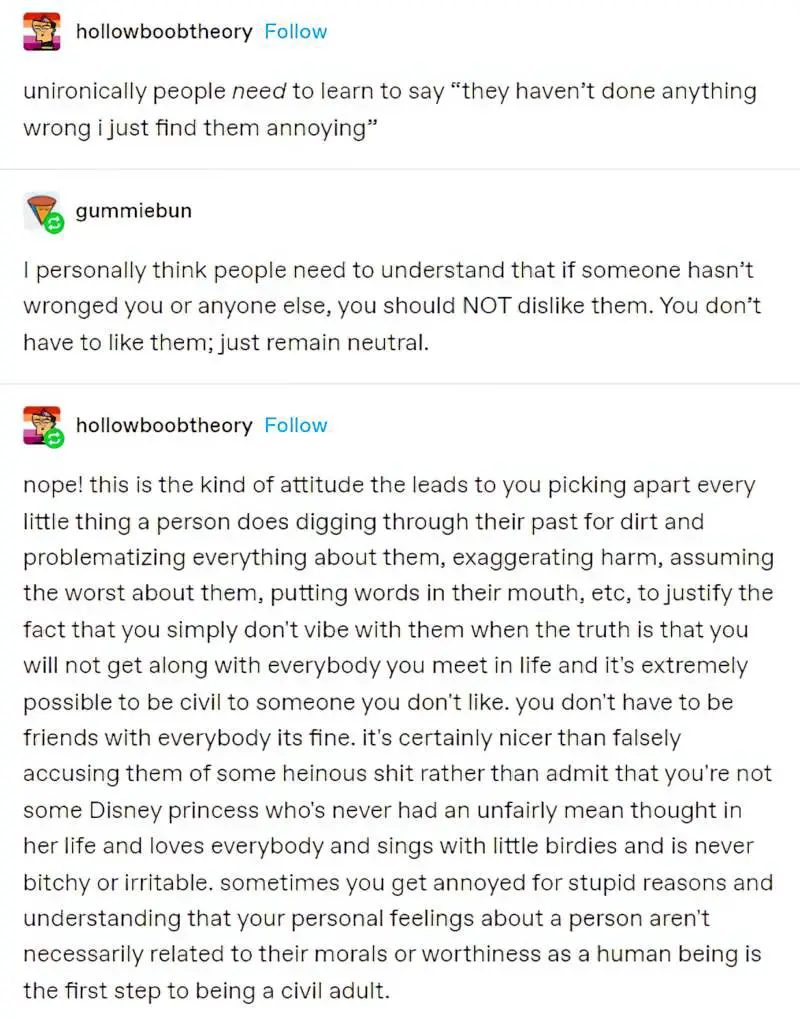

Even now, too many adults working with young people misunderstand the dynamics of bullying. Kids on the receiving end are frequently told that if they ignore it, the bully will get tired of them. But this isn’t how bullying works at all. Such advice goes against everything teachers know about how learning works, which makes such advice all the more baffling.

What happens is this: Bullies learn they can get away with bad behaviour, so the bad behaviour continues. Bullies crave the stimulation of a reaction. In search of a reaction, and with tacit permission to have at it, bullying in fact escalates when ignored.

In Tim Winton’s story, the teachers at the school hail from the city. Angelus High School is run by university educated people who have never been on the receiving end of continued, severe violence. We know this because the narrator’s parents are both teachers themselves. The father took off, leaving only the mother to offer advice on a specifically masculine subculture of the high school hierarchy. We are told the deputy principal is preoccupied, between his wife, his affair and his Amway side-gig.

Only one person knows what to do. That’s Biggie, who is far from book smart, but canny in the street smarts. Biggie beats the crap out of the bully. This is the language that actually works.

Mum thinks Biggie’s an oaf.

“Big World”

You rarely find this in children’s literature. Adult gatekeepers are reluctant to send young readers the message via literature that violence can work (even if it’s wrong). But you do find this plot in retrospective accounts of high school, in stories meant for adults. And we do see ‘effectively deployed’ violence exacted in real high schools. When I say ‘effective’, I mean a single act of retaliatory violence can end a long-running campaign. (Nothing else about violence is ‘effective’.)

We’re actually talking about The Trolley Problem:

A single decisive act of violence … joined me and Biggie forever. … Until that moment I was disappearing. School, home, the new town, they were all misery. If Biggie hadn’t come along I don’t know what would have become of me.

“Big World”

Schools now have zero tolerance policies around violence. This has an unintended consequence: Zero tolerance places the initial violence (no matter how long-running and severe) on the same moral plane as a single retaliatory act.

This is why ending youth violence is so difficult. “Big World” is an excellent snapshot of how well-meaning adults are frequently ill-equipped to deal with bullying. In the well-meaning teacher toolbox: Separating kids from the designated ‘bad eggs’; encouraging young people to imagine two different futures, one good, one bad; repeats of failed courses (paying little mind to the lowering of social capital which results from studying alongside younger peers). Biggie took from a different toolbox.

The examples above talk about retaliation at a personal level, but let’s take a much bigger view and head across the Tasman to the year Abel (Tasman) visited New Zealand and rapidly decided not to bother the Maori any further. Here’s what historian Professor James Belich has to say about the murders of Tasman’s crew members:

[New Zealand was found by Europeans in] 1642, when Abel Tasman sailed the ocean blue. He was a Dutch explorer hired by the Dutch East India Company to try to find gold and spices and precious things. He touched on New Zealand, the top of the South Island in 1642 after a couple of days of confused interaction with the local Maori. One of his boats was attacked by a Maori canoe. They were believed to be hostile or insulting and several of his crew were killed. After that, New Zealand had a bit of a reputation which actually, ironically enough, saved Maori from a longer period of interaction with European diseases in particular, and may have contributed to their current resilience as a people. So it was a pretty economical act of resistance to European expansion, but it kept Europeans out for well over 100 years until Cook arrived, and de Surville in the same year, 1769.

New Zealand: everything you wanted to know, History Extra Podcast

So there you have it. The trolley problem in history. A relatively small massacre saved an entire people.

Another example:

“ABBREVIATION”

When the title of a short story is an abstract noun (“Abbreviation”) and a concrete example of this comes up in the story (a missing finger) that’s our cue to look for a broader example of something “cut off” — something which works at the thematic level — the “big issue” of the entire narrative, if you will.

For me, Melanie’s cut-off finger ‘points towards’ the end of Vic’s childhood.

- “He wasn’t quite thirteen.” Stories about twelve-year-olds are very often about the end of childhood. In the West, twelve is considered a transitional age. Every one of Vic’s relatives fits neatly into either the child category or the adult category. Vic feels very much alone in that pendulous adolescent state. On the first page he cracks a childlike joke about worms which is also quite sophisticated. He’s old enough to have a wisecrack for his Nanna but young enough to apologise for it when his mother cautions him.

- Sixteen-year-old Melanie forces a sexual awakening upon twelve-year-old Vic. The first kiss literally hurts, as she grabs at his ear. But it hurts at a psychic level, too. Melanie is unusually sexually aggressive doesn’t understand consent. Someone taught Melanie that sex and pain go together. For this reason, I think Melanie has also had a premature sexual awakening forced upon her, too. Vic’s body responds physiologically, but neither he nor Melanie fully understands that a physiological reaction does not equal pleasure. (Nor does orgasm, for the record.) When Vic meets her again later, he feels differently about the make-out session. Notice how quickly things have changed, signalled by the end of a year, right as everyone sings “Auld Lang Syne” (old long since/long long ago). Winton probably wants us to think carefully about the meaning of “Auld Lang Syne”, since he gave Vic’s family the last name of Lang. Surely not an accident that Vic’s last name means ‘Long’ yet the story is — ironically — about things being cut short.

- We traditionally sing “Auld Lang Syne” at New Year, but in other parts of the world, at other times, it is also sung at funerals. It’s really a farewell song.

- The period between Christmas and New Year has an odd, nothing sort of feel to it. Most of us are on holiday, we forget what day it is, we eat at odd times, we hang out with relatives we don’t normally see. Before we know it, a new year has begun.

- A seaside setting also points us towards a liminal reading — Vic isn’t a strong swimmer so he plays around in the exact place where sea meets the land.

- When Vic returns to his own family’s camp, he is woken in the small hours by his uncle and auntie having sex. Now he has a sexual experience of his own to conjure in his mind. He is no longer a child, and is seeing adult things. We’ve already seen how Vic is starting to understand things without being told — he is old enough to put two and two together, work out the bike gifted to him by his dodgy uncle was stolen. Now he knows even more about the adult world.

- Vic has an injurious, painful experience out on the boat with his father and uncle on New Year’s Day. Again he conjures his make-out session with Melanie. This becomes his escapism.

- When he looks for Melanie to show her the hook that had to be dislodged from his leg, her crew have up and left. Only camp detritus remains. Vic never got to say goodbye. Their time together was cut short.

a condensed childhood

Now let’s go back to the beginning of the story. These few days over New Year symbolise a long childhood, which feels to Vic at the time like it will never end. Vic thought the family would never get to White Point. Waiting, waiting, waitin while Uncle Ernie typically drags the chain, arguing with his wife. Tim Winton spends a significant proportion of story-time on getting there.

The effect? This is how childhood feels to us all, until it is over. And when it is over, it’s suddenly over.

In Pixar’s Toy Story, the adult test audience had a completely different reaction to Andy giving away his toys. Kids were happy for Andy. Plus, the toys had a new home! Yay! But the adults were sniffling. Adults could see that giving up toys meant the end of Andy’s childhood. Nothing would ever be the same for him again.

Outside stories, we don’t tend to realise the moments marking the end of childhood. A premature, unexpected sexual awakening can do it. But generally it’s only with hindsight that we can pinpoint the moments which add up to an ending.

“AQUIFER”

In common with the opening short story of this collection (“Big World”) the first person middle-aged male narrator of “Aquifer” returns to his younger years. Waking up to a news item on the TV, he thinks about childhood events which formed him. “Big World” covered teenage years and leaving school. “Aquifer” is about preadolescent childhood, and the big, traumatic event which the narrator has always kept to himself: He saw his childhood bully sink into the swamp and die. The narrator’s family soon moved away.

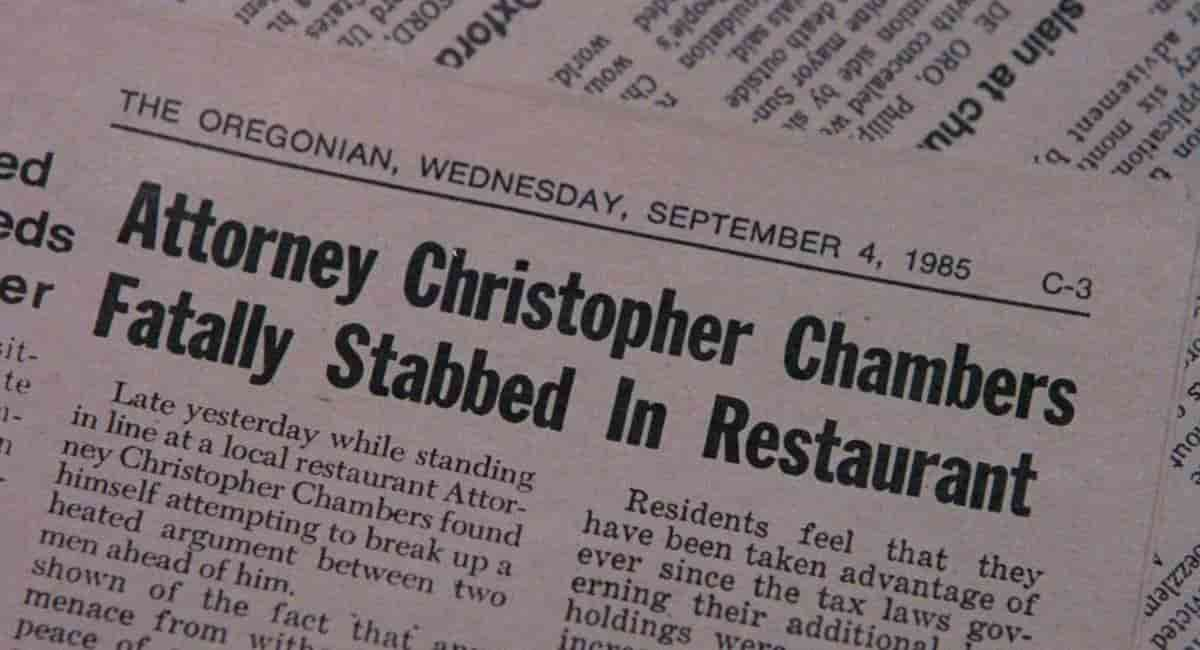

In many ways, this short story is reminiscent of the film Stand By Me. In both, a man in middle age returns to memories of his childhood small town after a criminal news story which reminds him of a terribly resonant memory from the boy’s own childhood.

Here’s the narrator of Stand By Me, tidying up the plot by telling us what happened to his friends:

Chris did get out. He enrolled in the College-courses with me. And although it was hard he gutted it out like he always did. He went on to College and eventually became a lawyer. Last week he entered a fast food restaurant. Just ahead of him, two men got into an argument. One of them pulled a knife. Chris who would always make the best peace tried to break it up. He was stabbed in the throat. He died almost instantly.

Stand By Me

Likewise, Tim Winton’s story opens decades after an initial ‘crime’ (harrowing incident?) and also after the climate has changed. (This distinguishes the 1980s Stand By Me from this one.) Draught has dried up the swamp, revealing bones which had never been recovered. The narrator’s childhood town was once a place where working class people and immigrants lived. Now the city has expanded to engulf it — everyone who lives here is now middle class.

QUICKSAND STORIES

This story involves a body of water with a lot of sludge at the bottom. Not exactly quicksand, but the same horrors.

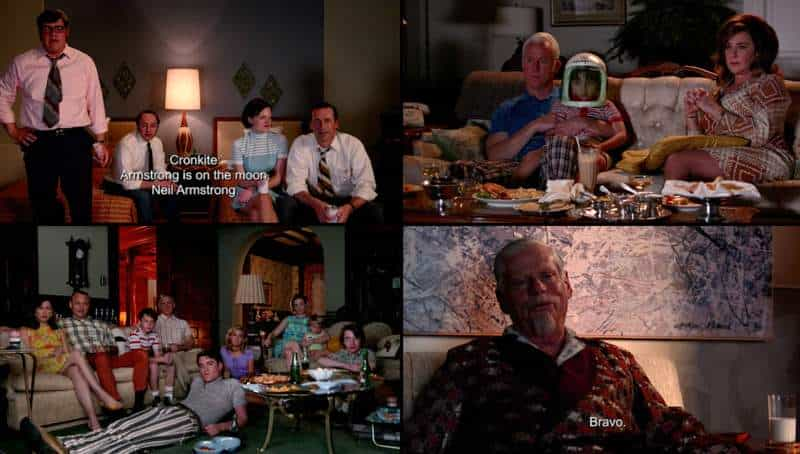

Quicksand horror stories were popular in the 1960s. This coincided with the Moon landing. No one was sure what would happen if a shuttle landed on the Moon — for all we knew, the Moon comprised a hundred metres of dust rather than solid rock.

Quicksand stories went out of fashion after that. By the time I grew up in the 1980s, the horror had gone — I only saw the spoofs on Saturday morning cartoons.

Does Australia have much quicksand anyway? I looked it up.

Quicksand can be found in many places across Australia and doesn’t need saltwater to form. It is primarily found where creeks and rivers flow into the sea, on the beach at low tide, along riverbanks or in rivers with sandy bottoms. A notorious area is Tasmania’s west coast between Pieman Heads and Arthur River.

Australian Geographic

Tim Winton unites two separate Australian fears in this story: Quicksand Fear plus Fear of the Billabong cf. Australia’s unofficial National Anthem, “Waltzing Matilda“.

THE TITLE: THE BRINGING OF THINGS

An aquifer is a body of rock and/or sediment that holds groundwater. Phonetically I’m reminded of Lucifer, especially after reading the imagery of burnt out cars left beside the swamp. Lucifer refers to Satan, of course. He was originally a Heavenly being but later cast down to the Underworld. But at its root Lucifer means ‘light-bringer’.

The words are related! They both contain the Latin root ‘ferre’, which means ‘to bring, bear or carry’. Aquifer means ‘water-bringer’.

Other examples of ‘fer’ meaning ‘bring’ in English:

- Conifer: ‘to bring cones’

- Fertile: ‘carrying babies/fruit etc.’

- Prefer: ‘to bring forward’

- Transfer: ‘to carry across’

- Refer: ‘to carry back’ (and from this, ‘referee’)

- Circumference ‘brought in a circle’

- Differ: ‘to set apart’

- Offer: ‘to bring for (someone)’

- Suffer: ‘to bear from below’

- Christopher: ‘Christ-carrier’ (a name from the Middle Ages)

(If you’re thinking ‘ferry’ belongs on this list, it is actually a Germanic word which came via Old Norse. It’s related to the word ‘fare’, to journey, wander, make one’s way.)

Is this short story about ‘bringing’, in all its forms? I can definitely see how the words ‘transfer’, ‘differ’, ‘refer’ and ‘suffer’ could arguably relate.

Winton’s “Aquifer” is clearly about time, and the way time does not travel like an arrow (or a river). The past always affects the present. (The past is brought into the present.) Time turns back on itself (cf. The Turning). A great many stories are about this very human relationship to time (The Father is another example I can think of), but Tim Winton’s story is very obviously about this, made apparent in the closing lines.

Winton has led us there by describing an resonant recurring habit of the narrator: Dialling from a public phone box to learn the time. As a boy he finds the voice comforting and reassuring. But when time starts folding onto itself, memories affecting the present, he no longer trusts it.

“DAMAGED GOODS”

If you remember the boy from “Abbreviation” is named Vic, it’s very soon clear that this is the same boy as a grown man. He’s married now, in middle age. This is his wife talking about her husband, who she finds an enigma. She takes road trips to his childhood haunts hoping to work him out. He’s a laconic sort, though she’s picked up many pieces of his jig-saw puzzle over the years. He does quite a bit of pro bono work. (From this I’m guessing he’s a lawyer, though this is not confirmed until later.)

I spent quite a bit of reading-time wondering if this man is the same man from “Big World”. Vic and the narrator of “Big World” have a number of things in common: Notably, their parents were sent to the small town of Angelus for work. Both had fathers who took off, unable to cope with smalltown life as well as their mothers. Both dreamed of getting themselves and exploring Australia after graduation.

But the point is this: That’s the standard dream for young men in Australia’s small town. They’re not the same person. They’re like different iterations of him; same environment, different seed.

The boy from “Big World” was sent to Angelus because his parents were high school teachers, whereas Vic’s father went there as a police officer. Same socioeconomic class, different outcome. Unlike the boy from “Big World”, Vic must have done well enough at school.

Even before Vic’s wife mentions it in this first person narration, I’d made the connection that Vic is drawn to women who have (what others perceive as) a physical malformation. (Speaking of ‘formation’, how formative was Vic’s first sexual experience, with Melanie? How formative are first sexual experiences in general? Do they disproportionately affect us for the rest of our lives?)

Vic’s wife finds this aspect of her husband disconcerting:

Vic has a compensatory element to his nature. When he talks about his pro bono clients you can see the earnest teenager in him. You can picture him battling on with his mother, feeling responsible for her as the only man, the only child in her life. And then I think of Strawberry Alison and his boyhood conviction that he alone understood her trouble, that only he saw the true face behind the mask. So endearing until you think of it turned your way. It’s no fun wondering if your husband’s love could be another act of kindness, whether there’s something about you he feels you need to be compensated for, as if you too qualify as his sort of damaged goods.

“Damaged Goods”

This theme came up in “Big World,” also: When the narrator feels disgust at his mate, Biggie, for revelling in the fact he’s finally found someone less smart than himself. The narrator’s disgust comes from the unpleasant realisation that he’s that person for Biggie.

But what is a long-term relationship if not for the ability to add something of value to your partner’s life? It is surely an evolutionary advantage that humans have this capacity — a romantic take on what some have termed The Benjamin Franklin Effect: a person who has already performed a favour for another person is more likely to do another favour for the other than if they had received a favour from that person.

It’s possible to get people to do things that make you like them more but respect them less. Avoid this, it destroys relationships.

Less Wrong

Rosy take: Long-term partners love us warts and all. The more we show, the more they accept, the more they love.

Tim Winton has offered us the disturbing riff.

Also disturbing: This is a “kill the queers” story. As soon as Strawberry Alison is revealed to be happy and in a lesbian relationship, she and her girlfriend go up in flame. Plus, the link between the birthmark and the flame feels uncharacteristically on-the-nose for Tim Winton.

If anyone here is considering adding a dead queer ending to the corpus of existing literature, please think twice.

“SMALL MERCIES”

A man returns from the city to his childhood town (again, Angelus) after his wife ends her own life in the garage, leaving him to solo-parent their young child. He lives in his mother’s house there, hoping to start fresh, away from awful memories.

But once he gets there, he’s pulled into a drama with the family of his teenage girlfriend. The girlfriend has battled addiction ever since the pair of them broke up. Now her parents are caring for her child, and are hoping she’ll find non-addicted friends to aid her recovery. Peter Dyson is just the man.

The old girlfriend — Fay — is literally delivered to his door one night (by Fay’s father — Dyson’s old football coach) and Dyson is expected to perform, somehow.

In common with 16-year-old Melanie in “Abbreviation”, Fay is sexually aggressive. She doesn’t respond well to Dyson’s no.

THE TITLE

Once again we have a multivalent title, with a literal outworking in the text. “Small mercies,” says Fay’s Catholic mother when Dyson is obliged to join them for dinner:

But, said Marjorie emphatically, we have our precious Sky. And we’re past the worst and we forgive and forget. Don’t we, Don?

Yes, said the old man subsiding, contrite, in his chair.

And we’re grateful for small mercies.

“Small Mercies”

This had me wondering if there are aspects to the word ‘mercy’ I had not considered. Marjorie and Don are Catholic. ‘Mercy’ sounds like a religious concept. So I looked it up:

At its core, mercy is forgiveness. The Bible speaks of God’s love for sinners – that is, for all of us. But the Bible also relates mercy to other qualities beyond love and forgiveness. […] As Pope Francis tells us in Misericordiae Vultus, his letter introducing the Holy Year of Mercy, Jesus’ mercy is not abstract but “visceral” – it’s something that quite literally changes us from the inside out.

What Is The True Meaning of Mercy? by Mathew Schmalz at The Conversation

And I’ll be darned if that last sentence doesn’t describe Tim Winton’s story exactly.

Towards the end, it is revealed in a threat from Fay that, when they were very young, Dyson and Fay became pregnant. Without Don and Marjorie ever knowing, Dyson was instrumental in arranging the abortion.

Like the mercy described by Mathew Schmalz at The Conversation, pregnancy is also ‘something that quite literally changes us from the inside out’.

On the ‘small’ aspect: There’s the literal size of a fetus, and the smallness of Fay’s child. Aside from that, Dyson’s life is becoming smaller by the day. His life became smaller when his wife ended her life. It became smaller again (by design) when he moved from the city to Angelus. But it was still big enough that he believed he could live somewhat anonymously, genuinely starting again to build a new life without the shadow of history looming over him.

However, once he’s dragged back into Fay’s drama — Fay who is in arrested development since their teenage years due to addiction — not only are his opportunities for new life opportunities winnowing down, he is being sucked back in time. Fay is sucking him back into their teenage years. With a baby as part of that history, it’s clear that the story is taking us inexorably in the direction of literal smallness.

We can deduce from this ending that unless Dyson leaves Angelus, he will wither away to nothing.

WHAT IS LOVE?

Twice in this collection already, Tim Winton has encouraged us to wonder: Is it love if you love feeling smarter (“Big World”)? Is it really love if your partner is attracted to damage (“Damaged Goods”)?

In this story, our main character wonders if he really loved his dead wife. He was attracted to her because she was so different from Fay — but Dyson’s new woman was subsequently revealed to be just as fragile — for different reasons (post natal depression, not drug addiction).

“ON HER KNEES”

When the mother of the story addresses her son as “Victor” we know this is another story about Vic — the kid who went camping at the beach during his thirteenth summer, whose police officer dad left the family after moving to Angelus, who lost his younger sister and was then an only child and who later married a woman who finds him such much of a mystery she makes solitary trips to his childhood haunts hoping to understand the guy. We also have it confirmed that he’s a lawyer, and the pro bono work he does is legal.

In this story we learn why Vic might be drawn to pro bono work. He’s a young, cocky law student who still think the law is there — is capable — of protecting everyone. His mother has learned that the law has its limits, and the limits are way back there. The law cannot protect her good name as a local cleaner, even if she’s legally in the right and has been falsely accused.

For me this was the most resonant story when adapted for film. Though I saw the film several years earlier, I remember the son watching his mother through the window as they leave. She stops to admire a lemon tree. Clearly, the film needed to slow the pacing so the audience could consider what made Vic change his mind about leaving the earrings where the owner could find them. This scene isn’t necessary on the page because the whole story has featured the interiority of Vic. Instead, at that moment, Vic goes back into the house to retrieve the vacuum cleaner but he doesn’t see his mother with the tree through the window.

You forgot the vacuum cleaner, she said.

Oh, yeah. Right.

I went back to the laundry, knelt at the catbox and picked out the earrings. I dusted them off on my sweaty shirt. In my palm they weighed nothing. I grabbed the Electrolux from the bedroom and made my way out again. In the kitchen I put the earrings beside the unstrung key and the thin envelope of money.

“On Her Knees”

THE DEHUMANISATION OF “ESSENTIAL WORKERS”

I hadn’t picked up from watching the film version that the woman who lives in this house works at the university Vic attends. Since she has enough money to pay a cleaner, we can deduce she’s a lecturer.

This story felt very familiar to me. I also had a parent who cleaned. I helped him do his cleaning occasionally as a teenager, when he cleaned at my high school. Later, when I was a university student, we both cleaned a building overnight at the university where I studied during the day. I experienced very similar feelings to Vic, cleaning the offices (not homes) of the lecturers who taught me. I, too, was falsely accused of something once (not theft — of playing computer games instead of doing my job. I had been sanitising a lecturer’s keyboard, not realising the CPU was still powered up.) I’m very familiar with how easy it is for people with power to accuse those they never see, and whose acceptance of ghost figures in their private spaces very much relies upon emotional detachment, if not dehumanisation. Ironically

THE IRONY OF WHITE FEMINISM

Winton lists the items in the lecturer’s house. Ironically she reads feminist texts — Germaine Greer (who I must add is trans exclusionary) and Erica Jong.

The cleaner in this story is also white. Rather than being a story which juxtaposes wealthy white women against an underclass of Black workers, this story is still about a form of so-called feminism which has been driven by white women: Get ahead yourself while using the invisible labour of other women.

This is not feminism to me. It’s fake feminism, because this woman is choosing not to see her own antifeminist act of employing a woman to do her lackey work, then failing to pay her properly, or afford her human dignity. By dehumanising another woman, she is doing exactly what feminists have long accused the patriarchy of doing.

THE SOCIAL HIERARCHY: APPEARANCE VS REALITY

What else are we to make of the items in this woman’s house? Along with the books — including pop psychology and erot*ca — Tim Winton describes prints on the walls of popular artists — the sorts of prints one might display if they wanted to look like they appreciated art. (Paul Klee and Oskar Kokoschka are Expressionists. Viewers must do a bit of work before making sense of them.) This all adds up to what we these days call “Basic Bitch”, academic version.

When Vic and his mother find the earrings, the mother knows they’re not worth $500. They feel light in Vic’s palms. The woman has an inflated self-image which doesn’t match reality.

And that’s what Vic learns via this experience. His mother doesn’t have a university degree but she better understands how the social hierarchy really works. The social hierarchy itself rubbish: Precisely because she sees the dirty aspects of these ‘important’ people, considered above her in every way, she knows they’re no better than she is.

Honestly, that’s the lesson I also took away from my years as a cleaner. Every important Joe Blow under the sun is somewhere soiling a toilet.

“COCKLESHELL”

“Big World” featured a meat works where the narrator and Biggie worked briefly after leaving school. This story is set in a hamlet on ‘the bay road’ just out of Angelus and there’s mention of a ‘superworks’ which has already closed. So my read is this: “Cockleshell” is set a few decades after “Big World” and involves the next generation of teens. The whaling station has also closed. Cockleshell (actually Cockle Shoal) is a dying town, and the families who remain are only there because they can’t find their way out.

The soundtrack to this story: “I’m a Creep” by Radiohead. (And perhaps the same vintage, c1993.)

Brakey realises one week in his teenage years that he’s suddenly magnetically attracted to the girl next door. They played together as kids, and her family have taken refuge with Brakey and his mum when her father was younger and prone to fits of rage.

I recently read some stats about men and domestic violence. Most men give it up by the age of 40. The reason? They don’t have the energy for it anymore. And they’re starting to lose their brute strength.

A sobering reality.

Strikes me that Old Man Larwood is one such man. Agnes goes spear fishing each evening to keep her mind focused on something outside the house. She’s noticed Brakey following her around. He’s so enamoured by Agnes he forfeits the opportunity to return home and put on shoes in favour of holding the lantern for her. Of course, he steps on something painful — returns him shamed.

There’s a House On Fire ending — a classic example of what TV Tropes calls Let The Past Burn (What’s Eating Gilbert Grape?, Office Space, Rebecca, “The Fall Of The House Of Usher”).

Here, it’s also an example of Fire Purifies. By burning her house down, Agnes kills the abusive father and also takes the family out of Cockle Shell. Without leaving the bay, she would never have found the opportunity to become a surgeon.

Once we learn she has become a surgeon, her ‘strange hobby’ of spearing fish makes more sense. Agnes has been honing her ability for sharp focus, unrattled by death and injury (Brakey’s foot).

A BAD but necessary DEED

In “Big World,” Biggie beat a bully up and saved the narrator’s high school life. A bad deed, good outcome. Likewise in this story, burning a house down is a terrible act. But if Agnes hadn’t done it, she’d never have made it out of there. Morality is not black and white.

(Shock troop: Any specialised, elite unit formed to fight an engagement via overwhelming assault)

“THE TURNING”

Now we come to the titular short story of the collection.

If you ever meet someone who is really friendly, unshockable, genuine, egalitarian, they’ll either be an outreach Christian or a Green voter.

So it is in this story. A woman in an abusive relationship lives in a caravan at a holiday park with two preschool aged daughters. Rae’s husband works on the boats. His temper prevents him from ever getting a promotion. The beautiful woman who compliments Rae’s belly-button piercing in the laundry room of the camping park seems too good to be true. Sherry is only staying here while their nice new house is getting ready to move into. Her husband also works in fishing, but in middle-management.

The two women grow closer and closer, as Rae starts to believe she can escape her own life for hours, days, at a time, hanging out with this middle-class woman who isn’t snooty at all.

Then one night Rae turns up to Sherry’s and the couple have been reading a Bible. So this is what they want. They wanted her all along for this.

At this point, the story forms a juxtaposed bookend to “On Her Knees”, because although Rae knows many things about Sherry, including how she lays items inside her drawers (because she helped them move in), she realises she knows nothing about them at all. Not really.

THE MANY MEANINGS OF ‘TURNING’

Turning has various related meanings. Here are some which relate to Winton’s short story:

- a place where a road branches off from another

- the action of using a lathe (shaving bits of wood off to make something shapely and smooth and elegant — as Rae becomes more elegant through association with Sherry, from a different class of person)

- moving in a circular direction (getting through the day, the season, going nowhere)

- moving something so it’s in a different place (Sherry moves to town)

- to change in nature, state, form or colour

- to make or become sour (first Rae’s husband, eventually every relationship in her life)

In Tim Winton’s “The Turning”, on the page, turning refers to the moment born-again Christians experience a formative, life-changing moment with God.

Is this short story an example of an anti-epiphany? That’s where a character is offered the chance to realise something but fails. (Importantly, the readers realise, seeing the situation at a distance.)

But it’s not an anti-epiphany. Rae’s ‘turning’ is a toxic version of an epiphany. When Sherry described her come-to-Jesus moment as ‘like a hot knife’, that gave Rae all the reason she needed to reframe her abuse in a way she can endure.

At story’s end, Rae is ‘turning away’. And so is everyone else who might help her.

This story says something profound about domestic violence. Many people turn away completely. Others, like Sherry, have the best of intentions and step in. They will befriend a woman like Rae, but eventually become exasperated when she refuses to leave the abusive partner.

Acceptance and friendship becomes a frustrating experience for people like Sherry, who doesn’t see value in the relationship unless she’s swooping in as saviour. In yet another story, Tim Winton has explored what it means to have a genuine, non-transactional, egalitarian relationship with another person.

“SAND”

I didn’t realise when first reading this, but Max is Rae’s abusive husband as a mean older brother. (If you remembered his name you’ll be right.)

Two men and two boys from the same family night-fish on the beach. What’s interesting for its irresolution: Mention of a missing mother who has been gone for two weeks. Readers get no further clues. There’s no hermeneutical closure on that, which makes me think the story of this family will be told in a subsequent story. “Sand” feels like a story fragment.

The story ends on a comical note but this story is harrowing. My best friend in high school lost a nine-year-old brother when sand collapsed on him at the beach one day between Christmas and New Year. The boy in this story really did have a near-death experience.

“FAMILY”

A story set in White Point again. This is where Vic’s family holidayed at New Year when he was twelve years old and met sixteen-year-old Melanie.

Ah yes. My hunch was right. “Sand” was just one small part of the story of these brothers. It’s not until I realise Leaper is the grown up Frank, and that he just quit football that I connect all three stories: “The Turning”, “Sand” and now this one.

The two brothers meet — seemingly by accident, though it’s pretty clear Frank (Leaper) was hoping to run into his older brother by visiting his exact patch of surf at the time he’d be surfing.

Frank tries to re-establish the fraternal relationship he’s been missing, and which has infected his mindset, affecting his game. Now that he’s quit his profession — the one which made him a local celebrity — he’s craving some family connection.

But Max has never even introduced Frank to his wife Rae, and nieces.

When Max reveals he’s been let go from the fishing boat, the timeline becomes clear. Rae is at home, injured from at least two of her husband’s beatings.

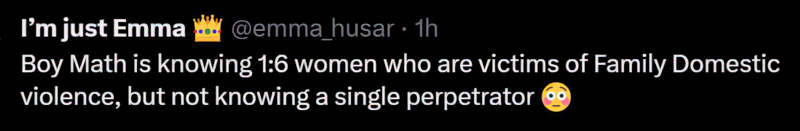

Although Frank knows what sort of man Max turned into, it doesn’t occur to him that Max might be beating his wife. With the proliferation of relationship violence, it’s a wonder more people don’t suspect their own brothers and friends. A deliberate un-seeing, and the unfortunate downside to always seeing the best in people.

Is that what the shark represents? Some horrible thing lurking beneath the surface? Frank didn’t see it coming (nor did Max). Chances are he’ll learn the extent of his brother’s abuse now that he’s either dead or critically injured. The shark isn’t the only thing to hit him out of the blue.

In an example of delayed decoding, I realise in this story (after piecing timing and characters together) that when Max jumped on Frank buried into the sand he really did mean to harm him, if not kill him. Before I realised Max was the abusive husband of Rae, I read that act as childlike naivety.

But should I be recasting a childhood event in this light? (I notice myself using the words of evening fishermen — light, casting.) We like to think events connect sequentially to each other. We like to fit things together. (Tim Winton knows this — that’s why he withholds information to let readers make connections for ourselves.) But is it fair to look at an abusive man and say, “Ah yes, he was always a bad one. Remember the time he did X and almost killed his little brother?”

What to make of the mother who up and left? To what extent do we blame her? And what are the things which make a mother leave, anyway? Likely as not, Max and Frank’s father abused her. It’s simplistic to conclude, “These two boys were abandoned by their mother. Therefore, they turned out one bad, the other pathetic.” But we don’t have the full story. (Not yet?)

“LONG, CLEAR VIEW”

We meet Vic again. This time he’s an adolescent. His policeman dad leaves, never to return. Vic feels responsible for his bereft mother, and for his baby sister. He doesn’t like the predatory vibe he gets from his father’s former colleagues, coming to the house to help his mother.

As displacement, and also as security, Vic cradles his father’s gun like it’s his own baby.

Anton Chekhov had a rule: If a gun appears in a story, it must go off. (‘Chekhov’s Gun‘ in storytelling.) Yet this gun doesn’t go off. Winton takes us closer and closer to a possible disaster. But Vic only gets so far as loading it and pointing it out the window.

Let’s call this an example of ‘Displaced Chekhov’s Gun’. Instead, we get a rundown of all the traumatic stories Vic heard as a kid — mostly of young people who died and became injured. With his father being the local cop, he was exposed to more of these stories than he wanted to be. Others expected him to know the gory details.

So although the gun in Vic’s adolescent hands never discharges, the story is full of menace and death.

Our reading of the story is fleshed out by other stories we’ve already read about Vic: He will spend New Year’s with his extended relatives and meet a sixteen-year-old girl. After that, he will lose his baby sister and become an only child. He’ll leave Angelus and become a lawyer. At uni, his mother will teach him about the social hierarchy, and battles worth fighting. He’ll marry. But his wife will remain distant and perplexed by him. The basketballer he’s in love with here will meet a lesbian lover and die in a fiery car crash.

This story doesn’t need a gun going off. Tim Winton has already given us the “long clear view” of Vic’s life.

And each time, he uses a different form of narration: third person; via a first person viewpoint character (his wife), first person when he’s cleaning the house with Carol, his mum, and here, second person. As if this is Vic himself talking, but making use of ‘you’ to distance himself from his own memories.

“REUNION”

As is evident from children’s literature, home break-ins can have a farcical quality.

A breather of a story in the series about Vic and Carol. Like “Damaged Goods,” this is his wife narrating. It’s Christmas, and they’ve been invited to Ernie and Cleo’s, who we met in “Abbreviation”. It’s been a long time, because Ernie and Cleo blamed Vic’s mother, Carol, for the break-up between herself and Bob, Vic’s policeman father.

Vic drives Carol and his wife — who we now learn is called Gail — to a suburb which reads on paper like the suburb from Kath & Kim.

Likewise, this has a sit-com plotline: They realise they’re at the wrong house. But not before Carol falls into the pool, and Gail joins her in childlike mirth. I found this story genuinely funny. Tim Winton makes an excellent job of writing a believable scene. At no point does it tip into farce.

The story is ironic: Sopping wet, Carol is too ashamed to join Ernie and Cleo, who they catch sight of in their driveway. Carol misread number 75 for 78. They go home without meeting them. But after a few drinks, Carol opens up about Vic’s family a little, talking about Bob though it makes Vic uncomfortable to hear about his father. This is the real reunion.

American 20th century author John Cheever wrote a short story by the same name.

“COMMISSION”

After a story of levity, now Vic’s mother is dying. Her dying wish: To see Bob, Vic’s father. It’s Vic’s job to go find him in the bush.

Writing techniques of note

- We’re never told how Vic’s mother is dying, just that she’s doing slowly. In stories, readers need to know how someone dies if it’s sudden. But if it’s a long illness, and it happens to someone elderly, we don’t have the same craving to know. (I suppose we assume it’s cancer.)

- Tim Winton lets us deduce for ourselves before confirming: It’s not that Carol needs to see Bob again. She wants Vic and Bob to reunite. Winton leaves enough time for us to make that connection on our own before we hear Bob and Vic realise it themselves. One of the most difficult parts of writing: Knowing what the audience can and can’t work out, and when to fill them in. Absolute beginner writers overexplain. When you’ve learned to trust readers more, intermediate writers hold too much back. Masterful writers confirm things on the page which they trust readers to have already worked out.

- When Vic first gets out and meets the drunkard, I’m sure we’re supposed to wonder if this is Bob pretending not to be Bob. Tim Winton surely knows we’re thinking this and cannot be fooled with a low-blow ‘reveal’. That’s not what this character is for, story-wise. He’s there to contrast against the man Bob could have turned into, had he not got himself sober.

Note that the previous short story was called “Reunion”, which was an ironic failure. Tim Winton has postponed the real reunion — the important one — for a story in which we weren’t expecting it. Now it’s clear how important “Reunion” was: Doing the job of letting us know how Vic feels about his estranged father. He wanted nothing to do with him, not even comfortable hearing his name.

The emotional valence between “Reunion” and “Commission” forms a juxtaposition which leads to great pathos when father and son finally meet again after so many years apart.

This story also fills in gaps which were left open in “Long, Clear View”, regarding the boy with the broken legs.

Now that Vic has reunited with his father, the story of Vic feels complete. I wonder if we’ll hear more of his story, and if the lives of Vic and Frank and Max’s family will be shown to link up somehow.

“FOG”

Vic’s story may feel complete, but what about his father? This story takes us back to when Lang was a police officer, though already affected by the drink and not very effective. He’s out searching for a missing hiker when he comes across a young woman reporter, first week on the job. Together they find the almost-dead man. This freaks the young woman out. Unable to summon for help to get him rescued, they spend the night lying each side of him, keeping him warm.

We have no hermeneutical closure regarding whether the injured hiker lives or dies but we know Lang lives because we’ve just seen him as an older man.

Told in third person past tense, the final paragraph utilises the auxiliary verb ‘would’.

He lay there to wait it out. At the first break in the fog he’d take the camera up the rock and set the flash off at regular intervals. Eventually he’d guide the vollies up to where he was. It’d come out alright. They wouldn’t freeze to death. The girl, Marie, would forget her blubbering fear because she’d get her rescue piece on the front page. She’d have her victim, her ordeal, her stoic hero. It’d be a great story, a triumph, and none of it would be true.

“Fog”

‘Would’ is such a versatile auxiliary verb that it can be a nuisance for communication, but, for more frequently, its breadth of usage is an asset. It can refer to iterative events which took place in the past: (“Every morning he would get up at six and brush his teeth…). Here it is doing one of two things, or both at once: What Lang thinks will happen as he’s lying here in the midst of the rescue attempt, and what actually happened. It all depends on whether the narration has pulled out from Lang’s head or not.

We don’t get to know if Lang’s plan with the camera worked. As I mentioned, we don’t know if the injured guy lived or died. We don’t know how Marie actually felt about the experience. For all we know, Lang thinks she’s happy with it. She could be left traumatised.

One thing I’ll say for sure: ‘Would’ is a useful way to collapse time onto itself, combining past, present and future into one hypothetical-memory space.

FOG SYMBOLISM

When utilised in stories, fog symbolism is usually pretty ‘clear’ (heh): obfuscation, mystery, dreams, confusion and a blurring between reality and unreality.

Here, though, I figure it means the DTs (delirium tremens) Lang experiences as he tries to show himself worthy in front of the young woman.

EXTRAPOLATION

Lang’s plan to be seek help via the camera flashing seems symbolic of a turning point in his life. After all, aren’t we looking for turning points in each of these stories? (The hint is in the collection title.) Lang left his family very soon after this incident. For whatever reason, this event had something to do with his thinking: the man who came so close to death; the wish to be a better person in front of a stranger, contrasted against the prospect of showing himself to be a drunkard in front of his increasingly world-wise adolescent son; the youth and earnestness of a young woman in search of the truth when he, himself, has been required to look the other way to the crime perpetrated by his police force colleagues in the corrupt small town of Angelus.

But it’s doubtful Lang understands why he up and left his family. He’s unable to achieve such clarity of thought under the fog of alcohol addiction. This is probably why Tim Winton leaves it to us to work it out.

“BONER MCPHARLIN’S MOLL”

By the end of the first paragraph we know this is the kid who had his legs broken. Probably by the police. We know this kid let off a fire bomb at the high school, yet charges were never laid.

It’s good storytelling practice to mention in passing a character who will later be fleshed out. By drip-feeding tantalising details, readers are primed to hear more. This collection would not feel complete without Boner McPharlin’s story.

Except we don’t get his story, not really, because this collection is about half-knowing as much as it is about anagnorisis — better described as turning points. We don’t get Joycean epiphanies here, because this is fiction aiming for realism, and in life you don’t get many — if any — epiphanies. Instead, you get slow realisations which happen after decades of extra maturity and reflection and slow-release extra info which helps characters form more of the jig-saw.

When I realise the story of Boner McPharlin will be told via the viewpoint of his erstwhile teenage girlfriend, I admit my heart sank a little. This is clearly Tim Winton’s thing: Alexithymic men depicted via the viewpoint of the women in their lives. Winton used this technique when he wrote an entire story about Vic, but through the viewpoint of his wife.

What does it mean for a story to be feminist, or, not anti-feminist? Here’s a pick-and-choose list for consideration:

- Stories told by women*, offering a specifically non-masculine take only non-male characters can provide.

- Stories told by AND ABOUT women characters which don’t centre men.

- Stories about women living free and non-stereotypically constricted lives within the patriarchy.

- Stories about how patriarchal, toxically-formed masculine cultures affect everyone, and how the gender hierarchy affects men and women differently.

*my definition of ‘women’ includes genderqueer characters, but we definitely don’t get that with Tim Winton

Which of these marks does Tim Winton hit and miss?

- Tim Winton is a cishet man, and can’t be expected to offer anything other than a cishet masculine take on non-cishet male experiences. Likewise, we can expect a Western Australia to write about a specifically Western Australian landscape rather than, say, a New York City one. The answer to ‘more stories told by women’ isn’t to coax male authors such as Tim Winton towards writing them. Nor is it about coaxing more women to write fiction. We already have plenty of fiction written about women. Instead, we need to defy the enforced ignorance about female (and queer and Black) lives which our culture heaps upon boys and then men: We need to buy books about girls for young boys and then keep that going without shaming anyone for failing to meet the strict criteria around ‘manly enough’.

- So if Tim Winton isn’t able to write an authentically female point of view, but must still people his stories with women — because women exist, and because these stories are realism — how might he utilise them in fiction? Answer: Winton uses women as viewpoint characters for parallactic insight into male lives. Women have better emotional insight because they have been allowed the opportunity without punishment. To a tee, Winton’s men have been emotionally stunted by trauma inside hyper-masculine cultures. Some of these traumas are big moments (Boner McPharlin). Just as often, trauma is sustained across many much smaller moments (Vic). In this collection, “The Turning” is the closest we get to a story about women. They are not being utilised as viewpoint characters into the psychologies of men. Instead, we see something of their own psychology.

- Some stories describe the horrors of the gender hierarchy we call patriarchy. Other stories offer a model for how society might look if only we worked together to make it more hospitable for women (and also for men, as a by-product). We need both kinds of stories. Tim Winton writes the former.

- I only take issue with men writing stories about men when authors are clearly blind to the fact that a gender hierarchy exists at all. In “The Turning”, Tim Winton showed he has a good handle on how society turns a blind eye to relationship violence. And here’s the frustrating fact of writing difficult subjects: In order to show violence and inequality, the writer has to show it. Simply by showing it, writers can be charged with normalising and even glorifying it.

What to make of “Boner McPharlin’s Moll”?

THE TITLE

Moll: A gangster’s female companion, or his provider of sex.

Right from the title, we have a female character described only in terms of her relationship to a man, like all those books that came out on the back of The Time Traveller’s Wife around 2012. (The Lighthouse Keeper’s Daughter etc. Author Emily St. John Mandel found 530 books with a title in the form The . . .’s Daughter.)

But if it’s right there in the title, authors know they’re doing it. (Authors far more often choose their own short story titles, if not their own novel titles.) In the case of great writers, I default to: “Authors do things for a reason… until they demonstrate otherwise.” (A hill I will die on: We can only ever guess at those reasons, unless they go on record in interview or something.)

WOMEN AND GIRLS AS FAKERS

When men write women (especially teenage girls) they too-often fall into a few hackneyed traps. One of them: Teenage girls fake at being women until they become fully-fledged and confident women. The O.G. example from pop culture is Angela Hayes, faking at sexual prowess in American Beauty. Angela was of course created by a gay male writer.

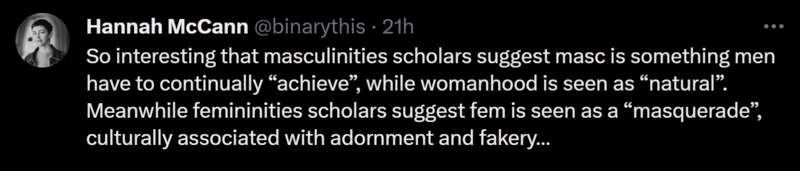

It is a true but unoriginal observation that teenagers try on their adult gender before it becomes natural. But you don’t tend to find paragraphs such as the following, written about teenage boys trying on their adult masculinity:

Erin and I … were at a cruel age when we clung fiercely to girlhood yet yearned to be women, and everything excited and disgusted us in equal measure. Sophistication was out of reach yet we could no longer remember how to be children. So we faked it. Everything we did was imitation and play-acting. We lived in a state of barely suppressed panic.

“Boner McPharlin’s Moll”

Even the best writers can’t achieve originality and insightfulness in every single character depiction, but that paragraph really sticks out to me as ‘a man trying to get inside the head of a teenage girl’. Note that at no time have any of Winton’s teenage boys felt anything other than authentically who they are at the time. The closest we get is Vic on the beach, looking at himself in the sixteen-year-old’s mirror sunglasses and seeing someone younger than he is. This speaks to his lack of readiness for sexual experience with another person. It doesn’t smack of fakery, and when men write about women, they too often slip into analogies about fakery.

Plenty has been said about this form of misogyny already, including by me, but for the ultimate in insight, look to transfeminism, where this error in thinking — that women are basically liars and fakers — is most starkly evinced. See: Whipping Girl by Julia Serano.

Perhaps we don’t need fewer of these stories. We need clearly exploration into how boys, too, try on masculinity, how gender performance does not, in fact, come ‘naturally’ to anyone, even if it feels that way.

JACKIE’S REALISATION

What has Jackie realised by story’s end, after Boner dies? That she wasn’t a good friend.

On one hand, this is a naturalistic response for the character. Women, far more than men, are taught to prioritise men over their own personhood. USA based Australian author Kate Manne wrote an entire book about that.

“always somebody’s someone, and seldom her own person. But this is not because she’s not held to be a person at all, but rather because her personhood is held to be owed to others, in the form of service labor, love, and loyalty.”

Kate Manne, Down Girl: The Logic of Misogyny

Here’s why it’s impossible to say whether a story is feminist or not: Stories are stories. There are feminist readings and anti-feminist readings of stories. (The same can be true of other things, e.g. postmodernism. There are no postmodern stories, only postmodern readings of stories.)

Having read Julia Serano and Kate Manne and basically kept up with feminist thought over decades, here’s my take: Winton has depicted a woman feeling guilty for not doing more for a man, when she was systemically shut out from the system. This shutting out was protective as much as it was patriarchal. While she’s left to regret not doing more for Boner, who she knew for a very brief period as a child, she’s not thinking about how everyone ‘knew’ she was sexually involved with this older boy, yet no one did anything to check in on her. All she got was judgement and… once again… turning away.

When characters in stories come to a realisation, they’re not necessarily seeing the fuller picture that we have been given. Tim Winton gave us a fuller picture, and interpretation of Jackie’s regret is up to us.

My stance can feel, at times, like authors are entirely let off the hook. I don’t believe that either. See, for instance, my take on the writing of Walter White in Breaking Bad, in which the writer (mis)guided a sexist viewership into liking Walt and hating his wife, Skyler (despite later proclaiming not to have meant that at all).

“IMMUNITY”

This story literally begins, “There was this boy I liked.” Winton doesn’t even pretend to be writing stories about women, even if they’re told by women. But, as I said, I don’t think Tim Winton is able to do anything more than he does here. He’s good at writing male stories. When he uses women as viewpoint characters, he’s digging into masculinity, with a level of insight that cannot be matched by alexithymic masculine types. (Another way in: write from an omniscient third person point of view, but that’s gone mostly out of fashion.)

We don’t find out until the final paragraph that the lonely bookish boy on the train is Vic, though some readers probably guessed before then.

In an example of delayed decoding, managed expertly by Winton, we know he hadn’t been holding a broom or a hockey stick, but a rifle.

The best stories work with irony at their heart. While Vic feels immune from death, his baby sister has just died. The feeling is no more than a feeling, a coping mechanism.

“DEFENDER”

Ah. Perhaps Tim Winton had a sense that the gun of “Long, Clear View” did need to go off after all, in line with Chekhov’s rule.

Here, the firing of a gun is subverted: Instead of killing someone, he and his wife’s friend’s husband are having fun with it. Vic realises, at the age of 44, that he is happy.

Perhaps this reading is too on-the-nose, but if guns are a symbol of masculinity, this would indicate he has gotten past the worst of its psychic damage. Now he’s a confirmed cuckold, and also somewhat disabled by shingles, and is ‘looking down the barrel’ of the increasing indignities of age. He’s reached a crossroad. It is either ‘come to terms with things’ or die spiritually. We’ve got “Defender” in the title — also a ‘title’ men feel they must uphold in order to be Good Men. It is only when the symbolic rifle is used as a toy that — ironically — the gun itself says something to Vic about what happiness can look like for him — not ‘free of masculinity’, but at peace with it, playing with it, picking it up and putting it down as he sees fit.

Of course, we’ve seen where toxic forms of masculinity can take you, by contrasting Vic with Max, who was a literal wife beater and literally got munched by a shark. I’d been half-expecting those two characters to join up somehow, but I think that’s the connection.