Window symbolism is as old as architecture itself. We can even find mention of windows in ancient mythology. Egyptian palaces had a window in which the Pharoah showed himself. The window itself became equated with the horizon. The sun rises above the horizon, filling the world with light.

Many stories feature windows, whether it’s children gazing from windows, opponents framed by windows, yellow squares of light offering the solace of civilisation. Windows can be important to a plot but are also symbolic.

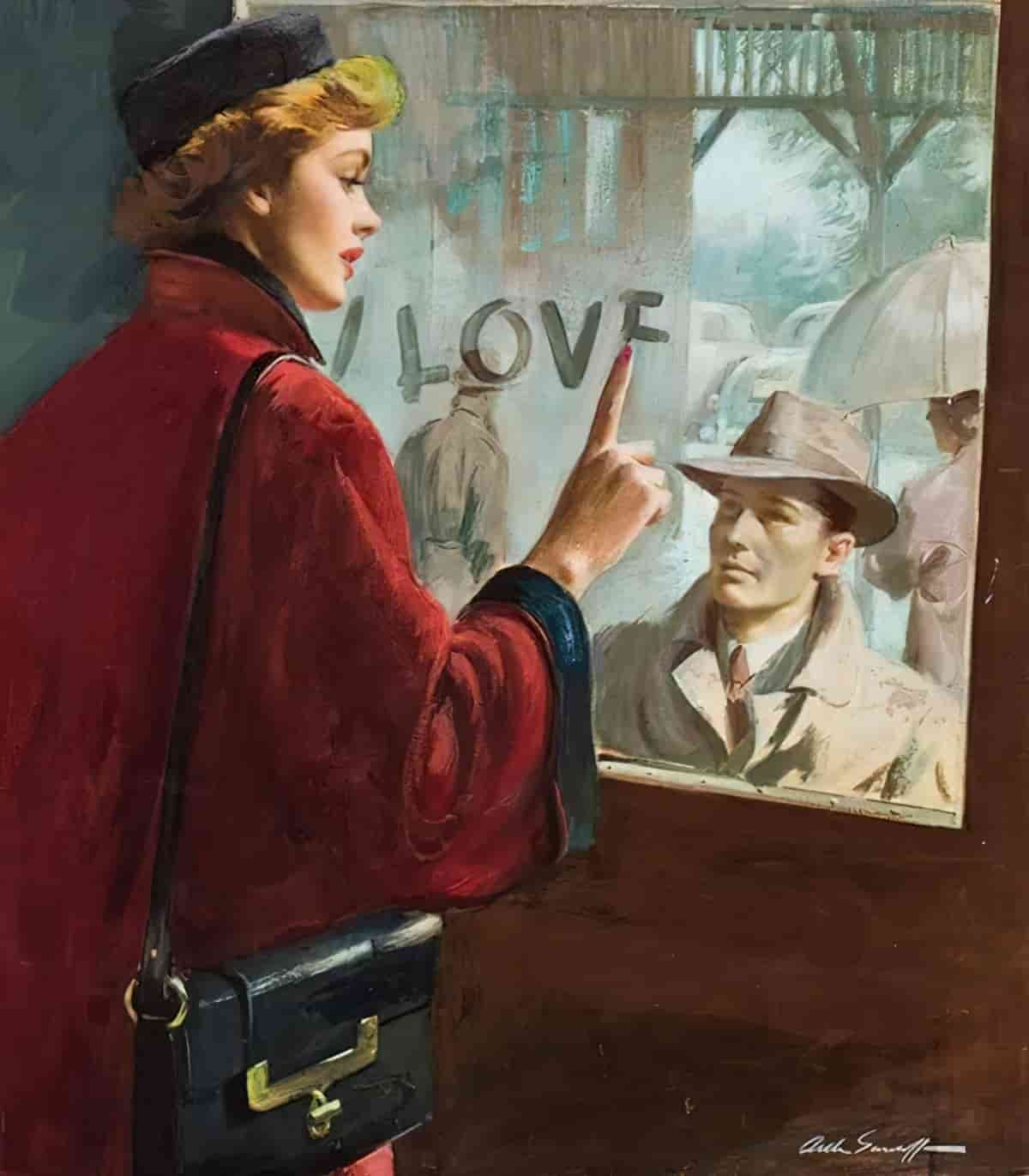

They quite often function as a visual motif to show the audience what a character wants.

WINDOWS IN FOLKTALES

These summaries are from Baughman’s Type and Motif Index of the Folktales of England and North America by Ernest Warren Baughman, 1966. Read through these story summaries and you’ll get a good idea of how coats have been used throughout history. Can you see patterns?

WINDOWS IN ANCIENT CULTURE AND MYTHOLOGY

The history of architecture is also the history of windows.

Le Corbusier, Swiss-French pioneer of modern architecture

Corbusier also said that the entire history of architecture can be seen as a struggle for larger windows.

THE FIRST WINDOWS WERE VENTS

We know from the etymology (word history) of the English word window that the first gaps in the walls of houses of Northern Europe were for wind and smoke. The first windows — as we know them today (as views to the outside world) — were invented in the ancient Middle East. Artwork depicting women looking out of windows is especially common in this part of the world.

WINDOWS IN EAST ASIA

Sheet glass used as window panes are older than you might guess. The Romans were using glass for windows around 100AD. As for Europe, there was a significant increase in glazing in both domestic and civic structures from the beginning of the late Renaissance, with increasing preference for clear over coloured glass. Glass technology made stronger and clearer glass. Glass is made of silica and plant ash, which often needed to be gathered from far away locations.

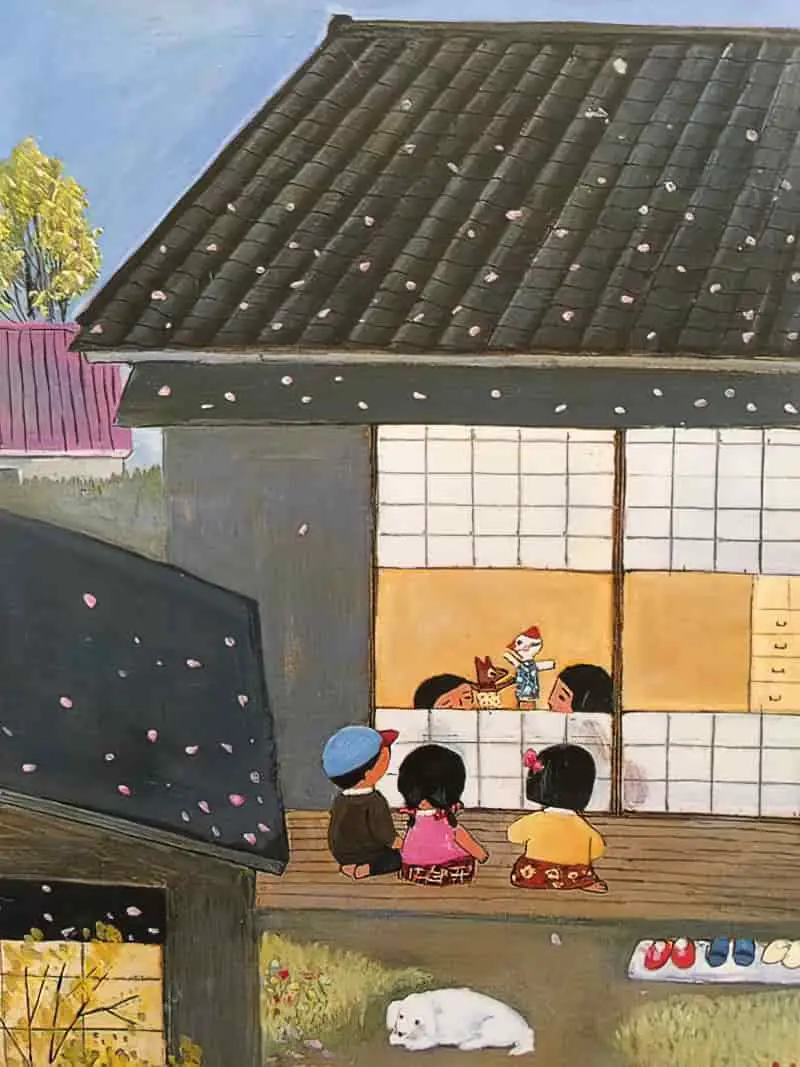

But let’s take a moment to consider ‘windows’ from other parts of the world, notably in ancient China, Korea and Japan, where paper was used as window material. Japan is well-known for its fusuma (sliding doors made of paper or cloth e.g. used as a wardrobe sliding door) and shoji (a fairly modern term referring to translucent paper doors and partitions) though the tradition comes from China. The oldest recorded evidence of folding screens in China dates back to 300 BCE. They were imported to Japan between the 7th and 8th centuries and became popular in the Kamakura period (1123-1333).

Aside from the well-known fusuma and shoji of Japanese architecture, there’s also the byobu (a folding screen which literally means ‘protection from the wind’), the tsuitate (a single panel entrance screen), a tobusuma (a wooden sliding screen) and the sugido (a cedar board). The Japanese made the screens portable with sophisticated paper hinges and also turned decorated screens into a Japanese artform. When Europeans borrowed the idea for these screens, they made them more like the Chinese ones — heavy and without portability.

Traditional Japanese houses are typically multi-use spaces, with furniture tidied away and replaced. Beds are rolled up and put away. Fusuma (decorative paper partitions) are the ‘moving walls’ of the house. Paper screens provide some privacy while allowing light to pass. They are well-suited to the mainland Japanese climate because they help reduce the effects of humidity in summer.

What about the windows on the outside of a Japanese house? Surely paper is no good against the elements, right? Right. But traditional Japanese architecture is well-suited to the environment.

A traditionally built Japanese house is called a minka. This is a distinctive structure. You can still find houses built this way in rural areas. Minka have thatched roofs, a generous veranda, a gable called a hafu, slabs of stepping stones leading up to the house, and distinctively Japanese windows called kōshi mado (latticed windows). The lattices are made with thin parallel strips of wood within a timber frame. Air and light pass through but the lattices provide some security.

When the weather really closes in, residents put up the rain shutters. These are stored in a tobukuro, a tall closet near the entrance. Importantly, minka are generous with eaves, which provide protection shade from the sun and also from the heavy rain which saturates Japan in June. Windows and entrances feature these eaves, called hisashi.

Some Japanese buildings have a specifically Japanese window called a mushiko-mado, a plaster construction inspired by the more traditional lattice window. The bars were plastered for fire-proofing, especially in built-up areas (prone to fire). Although these lattice/plaster-lattice windows have ‘bug’ in the name (mushi), that’s not because they keep the bugs out. They are named after traditional bamboo cages that were used to keep insects in. The Japanese ruling classes would keep crickets and other insects of interest in these high-quality, finely made cages.

So how do traditional Japanese houses keep insects out? Mosquitoes fly straight in through the lattice bars. As elsewhere in the world, fly screens proliferated in the 1960s. Before that, Japanese people used kaya (蚊帳). These are not common today, but you can see one in the Studio Ghibli film My Neighbour Totoro. (The children and their father move into a traditional Japanese home, where everything is a novelty to their young, 1980s eyes.)

A trope in some types of Japanese storytelling: A character moistens a patch on a paper screen to make it translucent and peer through. (Of course, paper screens offer no auditory privacy whatsoever.)

The ‘dramatic red Samurai background’ is a trope from Samurai fiction and has escaped the genre into other forms of storytelling. It comes from the fact that if you’re looking through a screen at night, you only see silhouettes. Violent scenes can therefore be conveyed to an audience without the full amount of gore. (Also, what’s left to imagination is often worse.) The redness is of course symbolic of bloodshed. (Sometimes the dramatic red Samurai background’ trope introduces a character rather than killing him off.)

Like other types of windows from other parts of the world, the paper screen contains the idea of interpenetration — unlike a solid wall, things can pass through it from each direction, including — of course — supernatural things. In a misogynistic trope we see the world over, the kitsune (fox) was thought to disguise itself as a supremely beautiful woman to tempt men into doing things they shouldn’t. Only a few could see the beautiful woman’s ‘true form’ e.g. dogs. But regular men could see her for what she was if they saw the kitsune passed between a lightsource and a paper screen. Her shadow would appear as a fox.

To more realistic stories: It’s easy to poke holes in paper screens. When a character does this in a story, they are demonstrating childish petulance or pettiness.

MESOPOTAMIAN MYTHOLOGY: FERTILITY AND WINDOWS

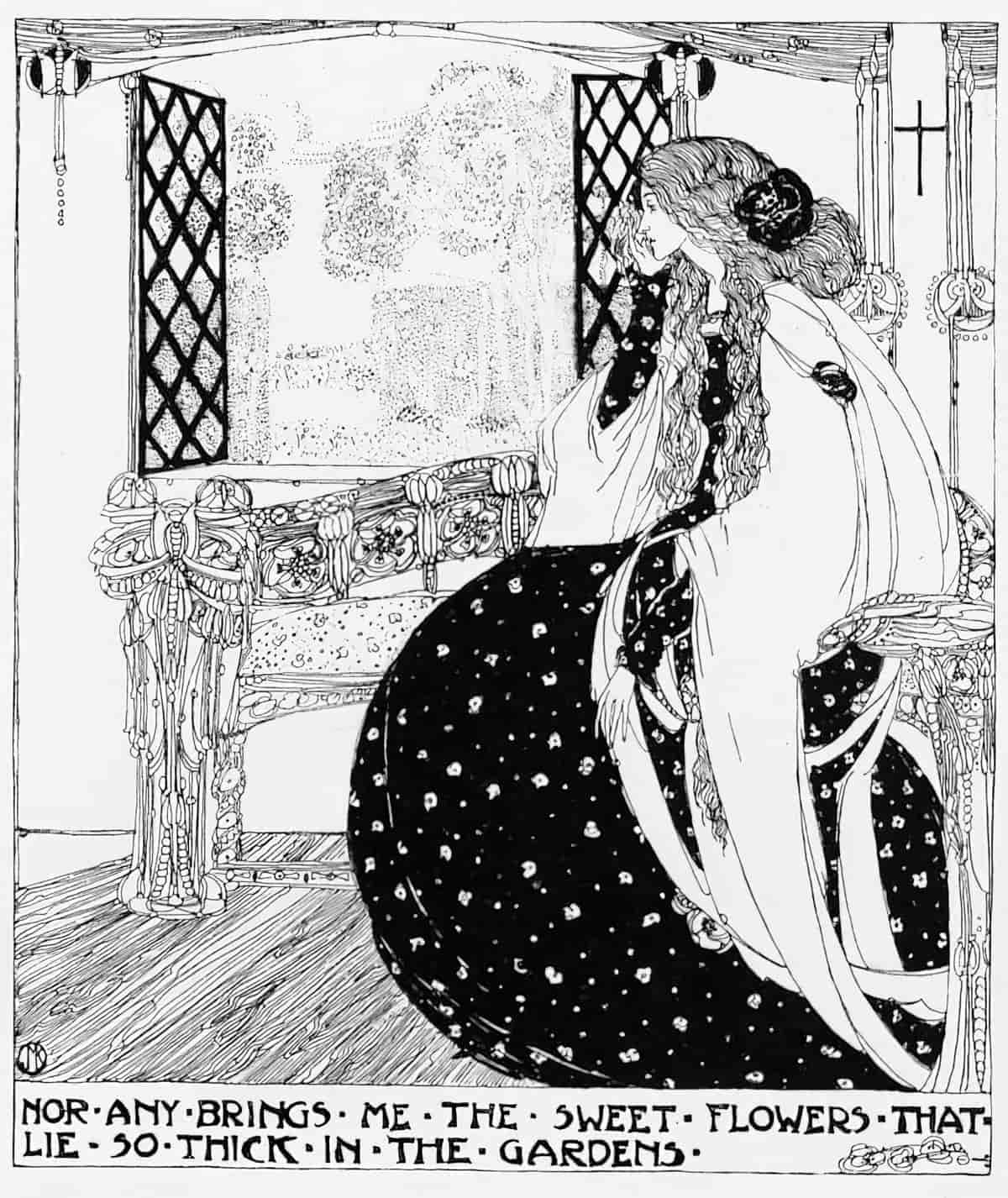

Mesopotamia had a goddess of the window (and fertility) called Kilili sa abati, which means the crowned one at the window, or she who leans out of the window. The window itself was thought to be her attribute, meaning the window was the material object recognized as symbolic of a saint or mythical figure. (This is why you get so many images of women looking out of windows.)

In the Near East, the window was thought to have the power of revealing the object of love. The window itself could either allow or disallow rainfall. The window had its own power.

The oldest images of women at windows are believed to represent the goddess Astarte, another goddess of fertility.

HEBREWS AND WOMEN AT WINDOWS

Hebrew people did not appreciate all these images of women at windows. The goddesses of windows and fertility were not only representative of polytheistic religions, but also associated with sex cults.

“From the window Sisera’s mother looked out. Through the window she watched for his return, saying, ‘Why is his chariot so long in coming? Why don’t we hear the sound of chariot wheels?’

Judges 5:28

Then Jehu went to Jezreel. When Jezebel heard about it, she put on eye makeup, arranged her hair and looked out of a window. As Jehu entered the gate, she asked, “Have you come in peace, you Zimri, you murderer of your master?”

2 Kings 9:30

Occasionally in the Old Testament men are also looking out windows. But whichever gender is gazing out, you know there is about to be some big, dangerous change.

THE GREEKS AND WOMEN AT WINDOWS

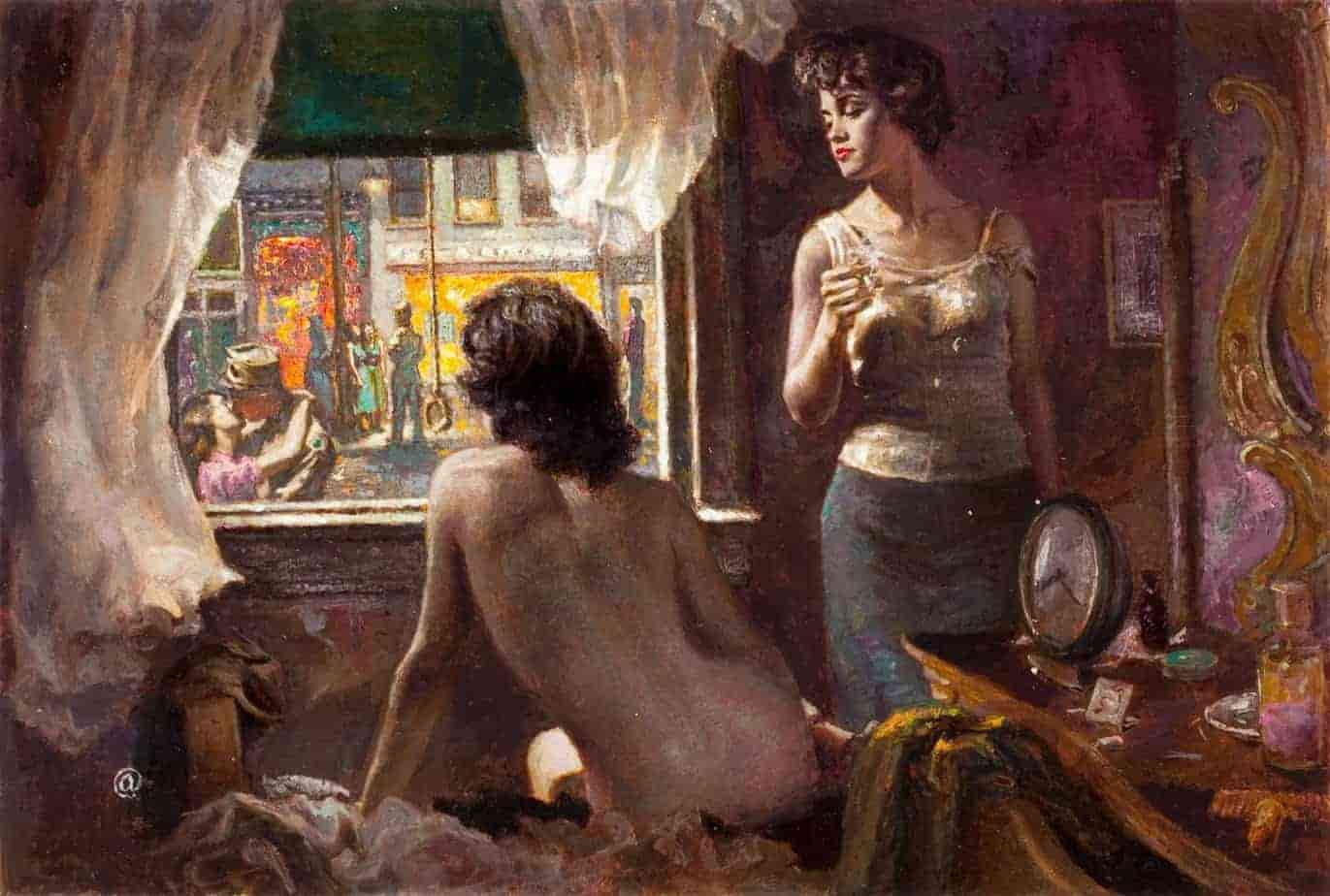

Over time, images of women at windows became more and more linked to stories about temptation and seduction (of men). Some art historians interpret women gazing out of windows painted on vases as caricatures of male desire and female sex work.

(Greek temples had few windows. Any windows were generally too high for anyone to see in or out.)

THE ROMANS AND WOMEN AT WINDOWS

The Romans were not nearly as antsy as the Hebrew and Greek people. Your right to look out of a window was even protected in law. (When building a house you weren’t allowed to block anyone else’s nice view.) The oldest Roman houses got their light mainly from atriums, but as architecture evolved, Romans became more and more interested in windows as a means to a view.

This change started with Romans who had holiday homes in the country. The windows at rear were increasingly meant to provide a picturesque view of the vista beyond. A good guest room required a nice view. And if there were no guests, the man of the house needed somewhere to admire his estate.

This symbolised man’s conquest over nature. (And by ‘man’s’ I do mean man’s. Women were not thought capable of rising above other animals. For more on that, read the first chapter of Beyond Power: On Women, Men and Morals by Marilyn French.)

THE CATHOLIC CHURCH AND WINDOWS

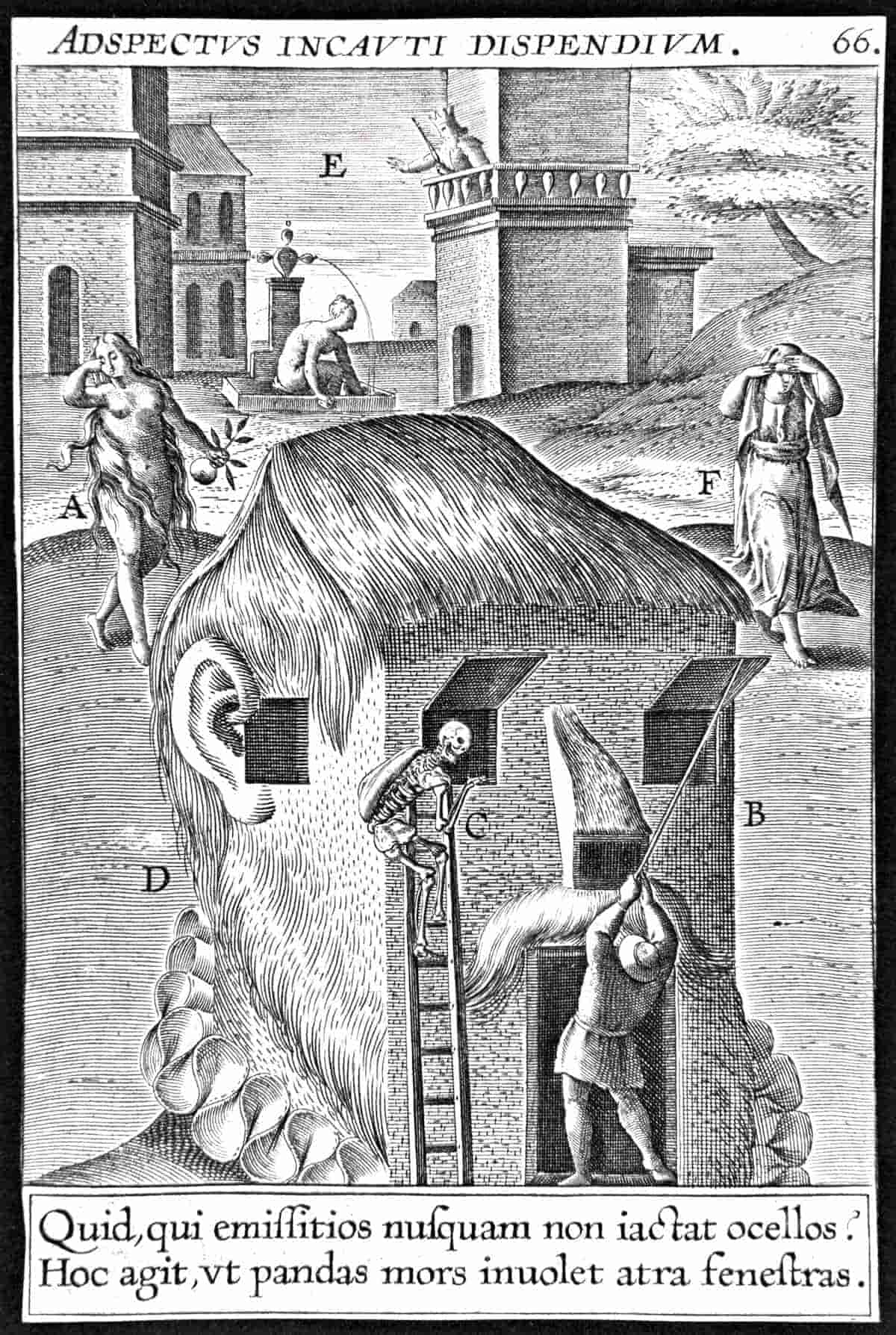

Catholic patriarchy, like the Jewish patriarchy, were highly suspicious of people gazing out of windows. If you hang around and think, without working, your mind would run to sinful thoughts. There was a general mistrust of any kind of sensual pleasure, which included standing around and taking in a nice view. You were supposed to keep your dirty, worldly eyes to yourself.

For everything in the world—the lust of the flesh, the lust of the eyes, and the pride of life—comes not from the Father but from the world.

1 John 2:16

Open windows were a metaphor for opening yourself up to God’s light, so you may see the City of God.

Everyone was supposed to follow this rule, but it applied especially to women. (This is how a patriarchy works.) Women were supposed to avoid windows and their temptations. (A woman’s place is in the home; looking out would only make her desire escape.) In every strange idea you’ll find an extreme. Look no further than the female hermits (anchoresses) of the European middle ages. Their rule book explicitly warned them against the ‘evil’ of looking out windows.

After the Council of Trent (1545-63) many convent churches had grilled screens in place. Nuns could not be trusted. They might prove too much temptation for the male churchgoers, so they were required to sit behind these grilles. The grilles had spikes on them so the men would not be tempted to peer in and get an eye-full of a tempting nun as she communed with God. These women belonged to God, and only to God. Grilled windows caught on and were soon a common feature of monasteries and convents where windows faced the street. If a nun or a monk showed too much interest in what was going on outside, they were threatened with removal of windows.

This is why, for centuries, the cells of nuns and monks had very small windows. Church windows are above the level of the gaze, so people in church cannot see out of them. Glass is stained so you have no choice but to admire the artwork, not see anything outside.

You can track when it became acceptable to look out of windows because people doing just that began to appear in art, along with artistic views. This change happened around the beginning of the 1400s.

Still, Catholicism encouraged devout looking and discouraged ‘worldly’ looking. Even what people looked at had rules around it.

THE RENAISSANCE

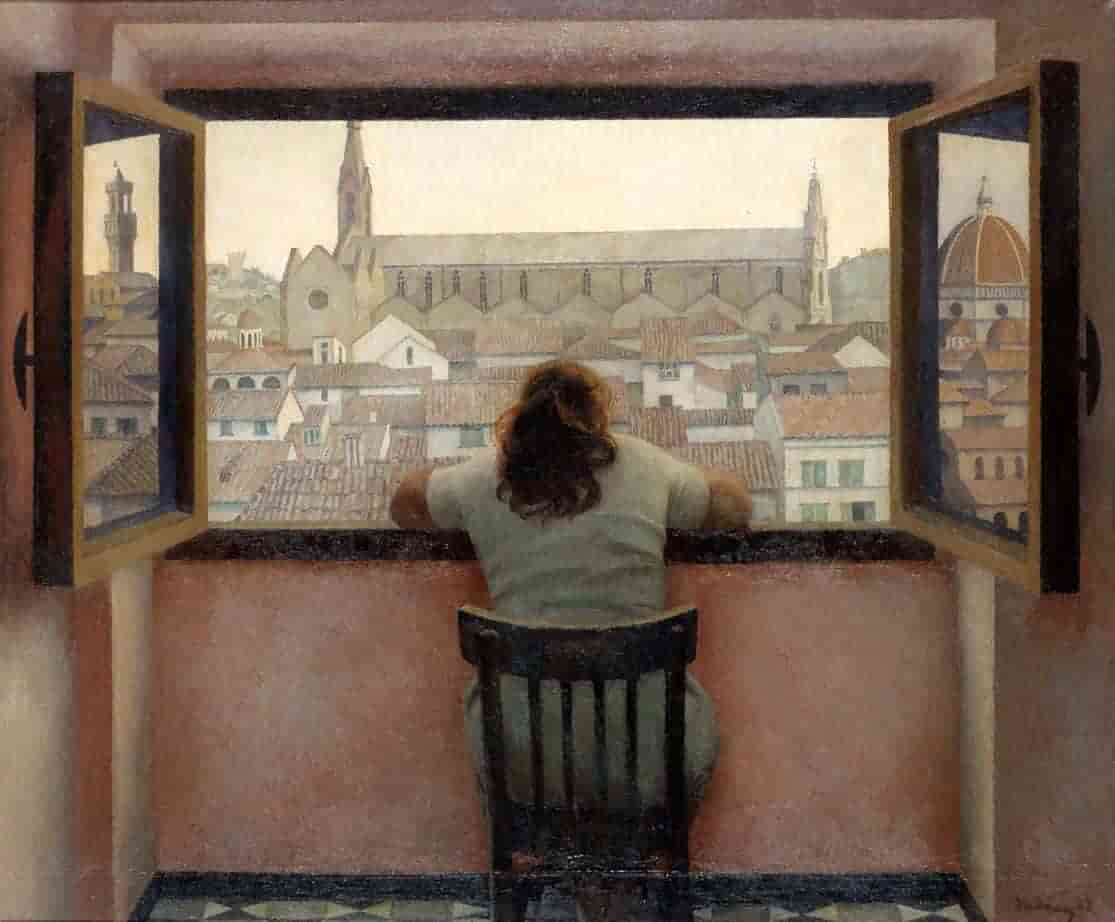

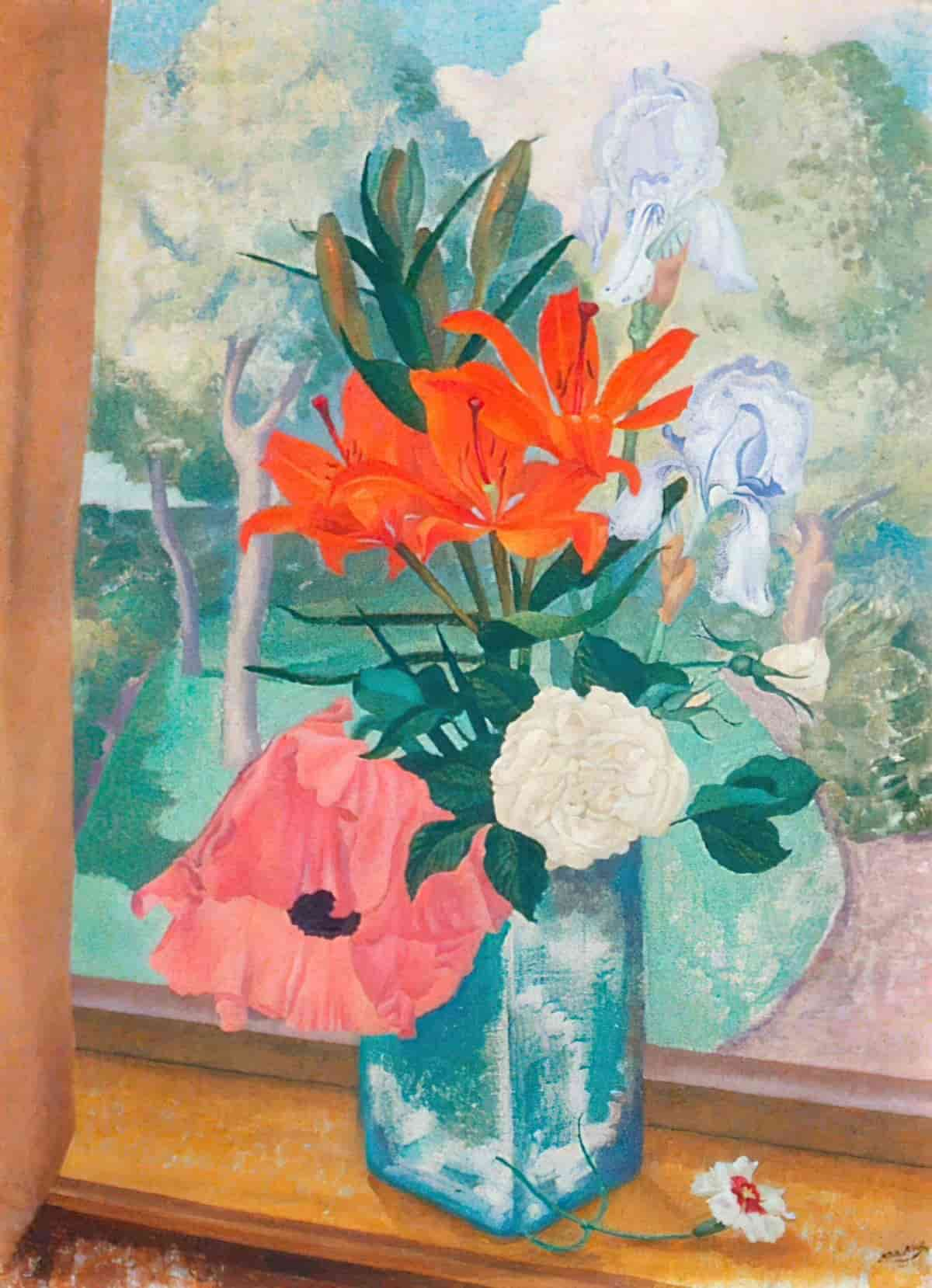

During The Renaissance (generally described as taking place from the 14th century to the 17th century), there were big changes in how we thought about sight and perspective. Views became important, and paintings became more three dimensional. Now, in well-known paintings, we have examples of foregrounding, middle-grounding and backgrounding, sometimes through windows.

Early modern Europeans (1450-1789) became very interested in whether human vision returned an accurate (veridical, reliable) picture of the world. telescopes, lenses and windows (literal and metaphorical) often came up in these discussions.

I remember that, when looking from a window and saying I see men who pass in the street, I really do not see them, but infer that what I see is men. … And yet what do I see from the window but hats and coats which may cover automatic machines? Yet I judge these to be men. And similarly solely by the faculty of judgment which rests in my mind, I comprehend that which I believed I saw with my eyes.

Rene Descartes, Meditations on First Philosophy (1641)

(Importantly, Descartes was raised in the Catholic tradition, which means he’d been taught not to look out of them willy nilly.)

PROTESTANTS AND WINDOWS

The Protestants were far more forgiving about people enjoying views. Protestants did take issue with some kinds of looking — looking at other gods and especially at Catholic art and relics — was not okay. But looking out of windows at beautiful views? Sure. Have at it.

At least, if you’re a man. Martin Luther (1483-1546) was the catalyst of the 16th century Protestant Reformation. He had three daughters and strong opinions about how women should live their lives. He did not like women who gazed out of windows, and coined the German phrase ‘Fensterguckerin’ to describe them.

[Women should be] like a nail driven into the wall […] stay at home and look after the affairs of the household.

Martin Luther

Note that Luther prayed at exterior windows, which was in direct contrast to Catholic men of the church, who prayed at small interior windows called hagioscopes or, colloquially, a leper’s squint as people deemed unfit for public gaze, possibly contagious, were expected to hide themselves but were also expected to attend church.

Luther regularly stood at windows and gazed out. He also prayed before a window each night before bed. (Performatively, perhaps — there are stories of people outside watching him commune with God.) Catholics learned of this guy standing round praying, looking out windows and condemned the practice as a non-Catholic one.

Eventually, after centuries, it became okay to look out of a window — for all genders — so long as you were looking outside to admire God’s creation and not for nefarious, pervy reasons. If you must gaze out a window, do it for edification, not for entertainment.

Look at the marvelous splendor

German Lutheran poet Barthold Heinrich Brockes, 1700s

of all of what God has created!

Thence you will

not just in the next world, but already in this one,

receive in every moment new bliss.

Unfortunately, as soon as it became spiritually A-okay to gaze out of windows, industraialised capitalism hit its stride. So again you weren’t supposed to stand around gazing out of windows because if you weren’t earning money for some fat cat’s coffers, you were wasting yours and everyone else’s time.

This attitude comes into sharp focus when hearing people talk about the treatment of prisoners, whose only use was to perform hard manual labour.

Prospects [views from windows] seduce the indolent from their work.

John Howard, 18th century English prison reformer

WINDOW-ADJACENT SYMBOLISM

THE ‘WINDOW’ AT THE TEMPLE OF RAMSES III

The temple of Ramses III in Medinet Habu, Egypt, was one of the last great funerary structures built in Western Thebes. It has the best-preserved temple palace in Thebes. Inside, on the northern wall, is something called The Window of Appearances. This window is a gap in the main façade of the building. The king sat here during religious ceremonies.

As we have seen, a paper screen functions symbolically as a window. What else might we include in this family of symbols?

THE BALCONY

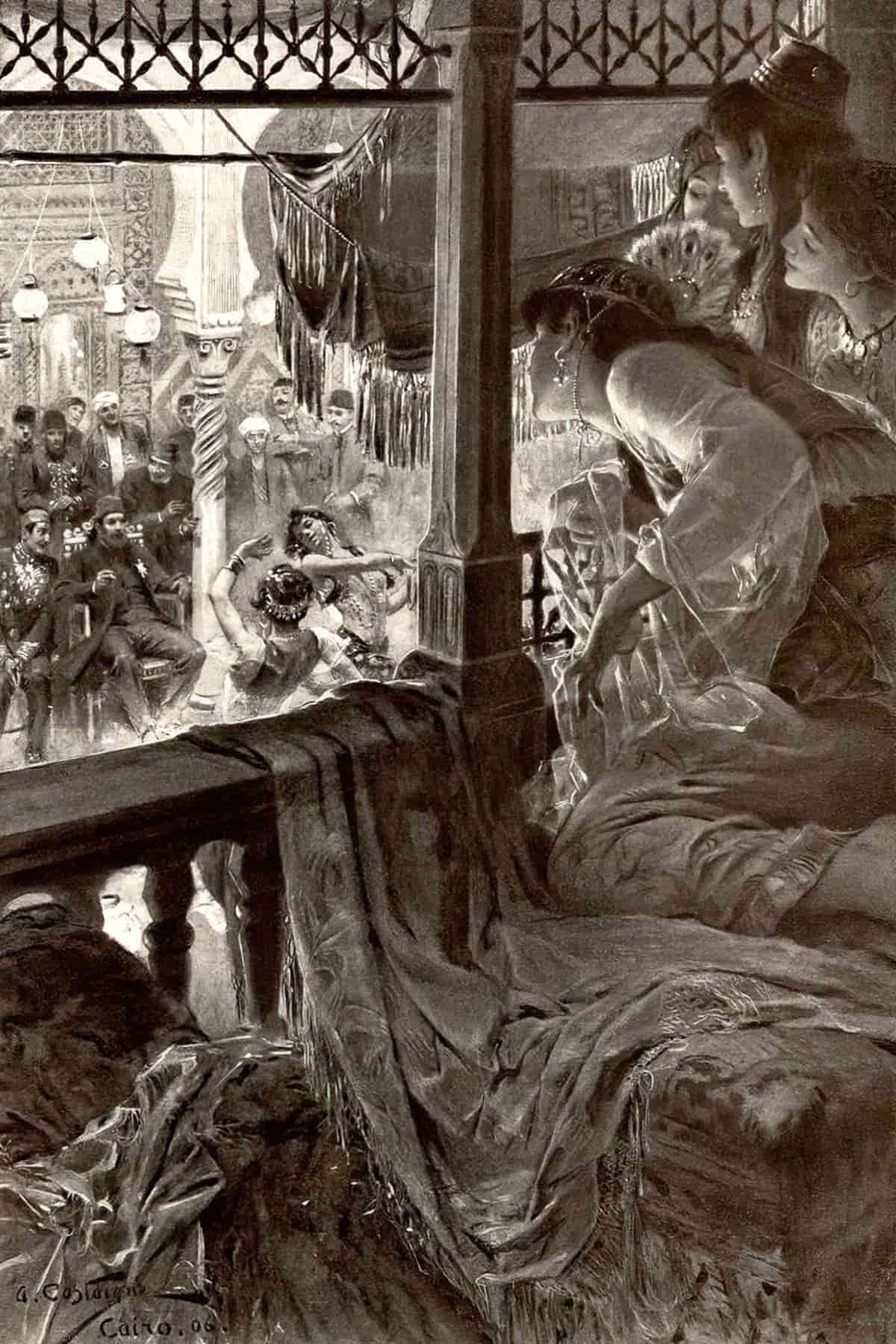

Well, The balcony is symbolically similar to a window. The balcony is a place to stand and gaze down at the world, part of the world but also removed. A box at a theatre is another window-adjacent symbol.

THE CAMERA

If a window offers a picturesque view, the house itself functions as a well-positioned camera.

The practice of standing at a window, taking in a view, is similar to the impulse behind taking a snapshot with a camera.

The inextricable connection between the open window and the invention of photography […]

The pioneers of photography were fascianted by the idea of capturing life and reality, in its elusive momentariness, on a glass plate, and few other places lent themselves better to that enterprise than the window, that “veritable microscope that allows me to discover an entire world in a nutshell,” as one nineteenth-century writer called it.

Daniel Jutte, 2016, Window Gazes and World Views

THE FRAMED PICTURE

A picture hanging on a wall of a beautiful vista is an emulation of a picture window, and vice versa. Leon Battista Alberti (Italian Renaissance humanist author, artist, architect, poet, ordained Catholic priest, linguist, philosopher, and cryptographer) famously came up with the idea of ‘painting as window’.

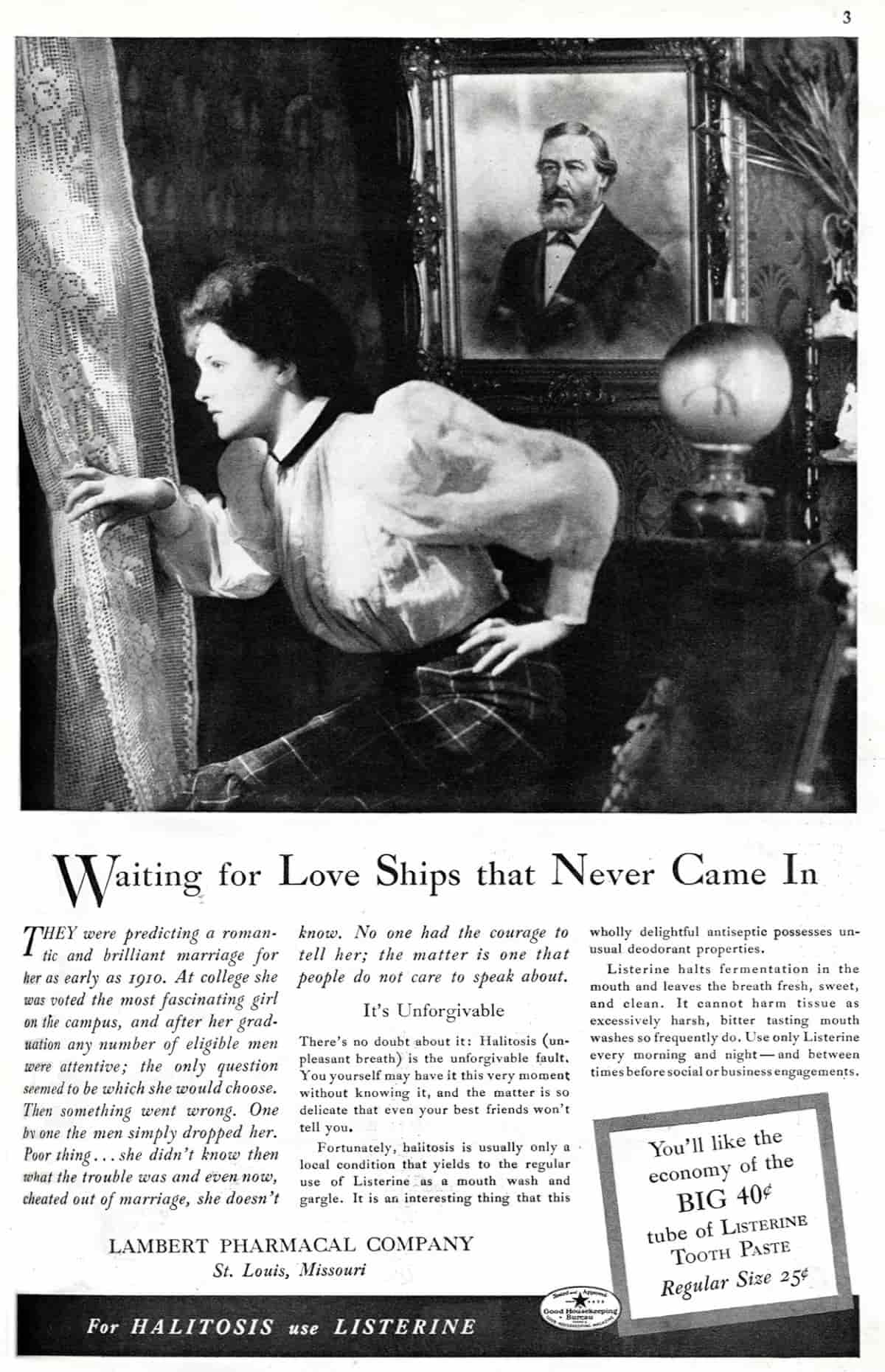

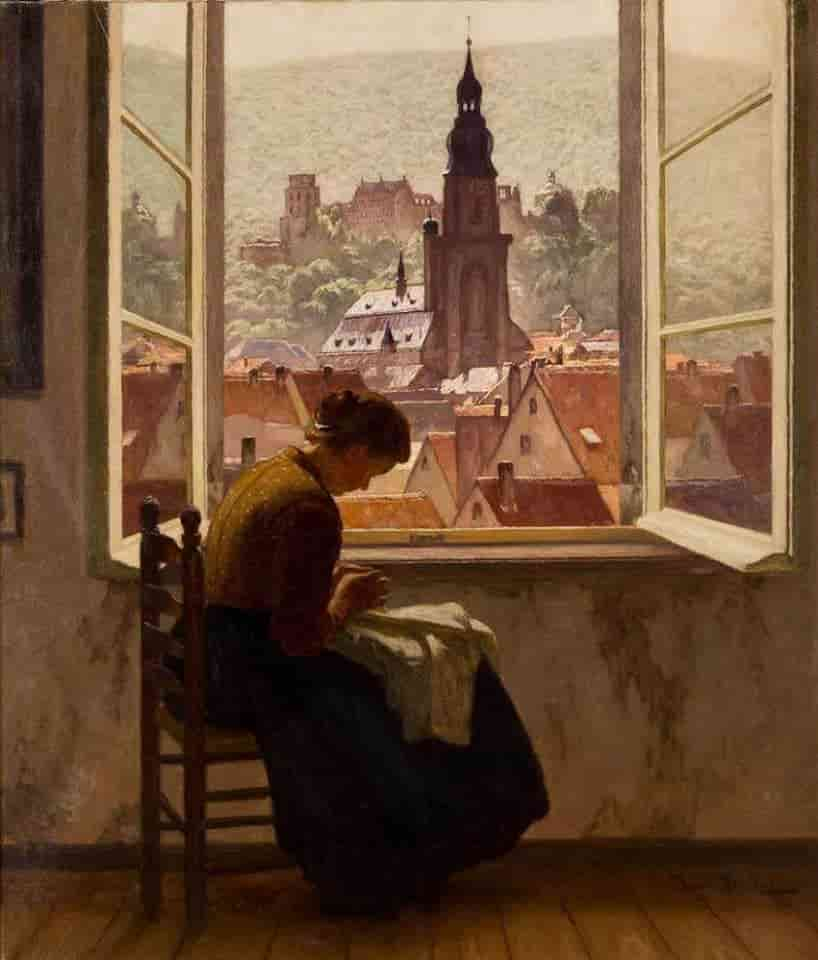

Alberti was yet another misogynist who loved his windows, but cautioned women against spending “all day sitting idly with elbows on the window sill, like some lazy wives who always hold their sewing in their hands for an excuse, but their sewing never gets done.” Windows, according to Alberti, were for male enjoyment. Women should get on with their sewing.

Of course, underdog men weren’t allowed to enjoy window views either.

THE ATRIUM

In architecture, an atrium is a large open air or skylight covered space surrounded by a building. Modern atria, as developed in the late 19th and 20th centuries, are often several stories high and having a glazed roof or large windows, and often located immediately beyond the main entrance doors (in the lobby).

Atria were a common feature in Ancient Roman dwellings, providing light and ventilation to the interior. The Latin word atrium referred to the open central court, from which the enclosed rooms led off, in the type of large ancient Roman house known as a domus.

The impluvium was the shallow pool sunken into the floor to catch the rainwater. As the centrepiece of the house, the atrium was the most lavishly furnished room. Also, it contained the little chapel to the ancestral spirits (lararium), the household safe (arca) and sometimes a bust of the master of the house.

It’s clear looking at the original function of the atrium what it might mean symbolically in stories:

- a direct link between home and the heavens, where a character might go to look up at the sky and contemplate freedom, journeys or death.

- luxury and riches — you’ll find an atrium in a house with unbound riches.

- water, light and cleanliness — purity of spirit and soul

The human heart is also divided into ‘atria’. The atrium is the ‘heart’ of a large house, connecting various parts of the house to other parts. It is where various things meet, symbolically.

The inverse of an atrium is a cloister, or perhaps a basement.

The gardener’s glasshouse is a form of atrium.

THE FOREST AS ATRIUM

The Jungle Book film poster depicts the jungle version of an atrium as first envisioned by the Romans in their architecture — a home in the jungle whose canopy of trees overhead lets in light. The forest is often seen as nature’s ‘cathedral’ but I think atrium is a better fit.

THE ARCHETYPAL WINDOW

But what do you think of when you visualise ‘the archetypal window’? That will probably depend on where you grew up. But ‘storybook’ versions of things tend to be a little different — less modern — than what you have in your own house. Let’s say The Archetypal Window is the double-hinged type which opens inwards. The French window. This window reveals the interior to the exterior.

SIMULTANEITY

Because a window lets you be inside and see outside at the same time, the window is associated with simultaneity.

DETACHMENT

Because you’re in both places at once, you’re also in neither of those places at once, which means the window can symbolise detachment. You feel neither here nor there.

WINDOW AS SITE OF INTERPENETRATION

Interpenetration: the process of spreading completely through something or from one thing to another in each direction.

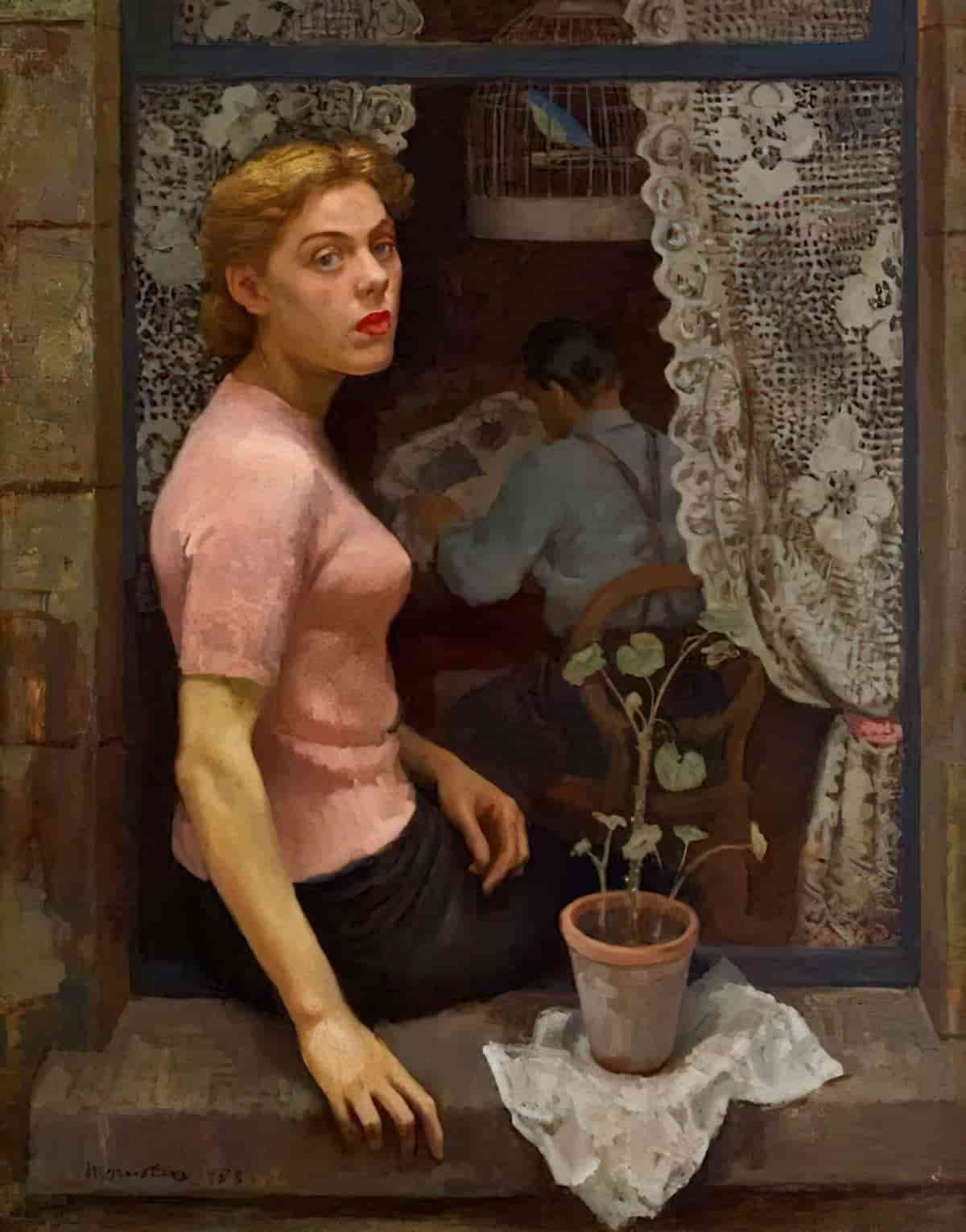

Symbolically, windows are the architectural equivalent of the veil. Their double duty is to shield the ‘wearer’ from outside forces while also keeping the outside world away from the wearer. Also in common with the veil, the window is diaphanous (modern windows are completely see-through), so when behind a pane of glass, we are physically shielded but remain psychologically exposed; we see the exact horror playing out on the other side.

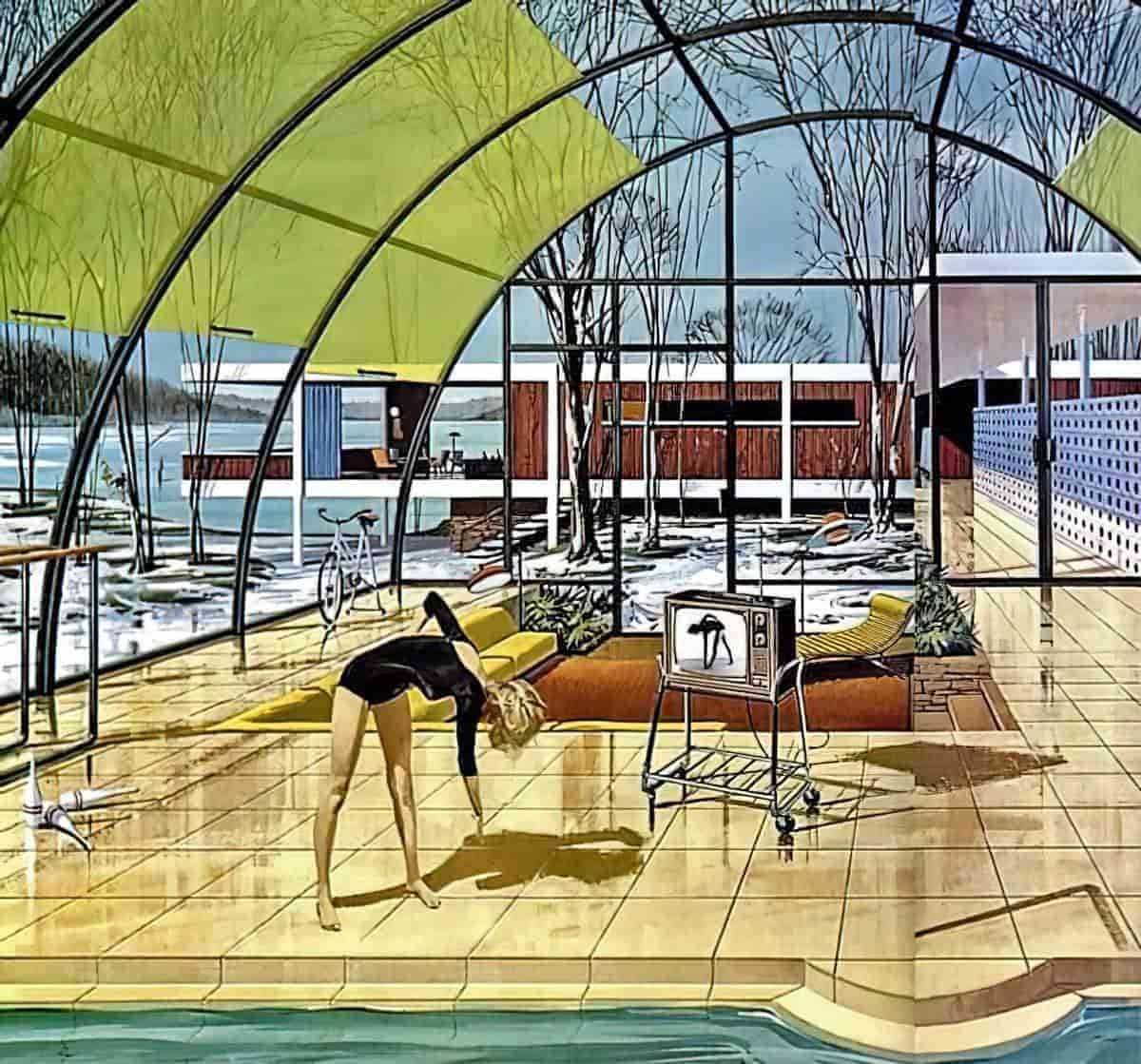

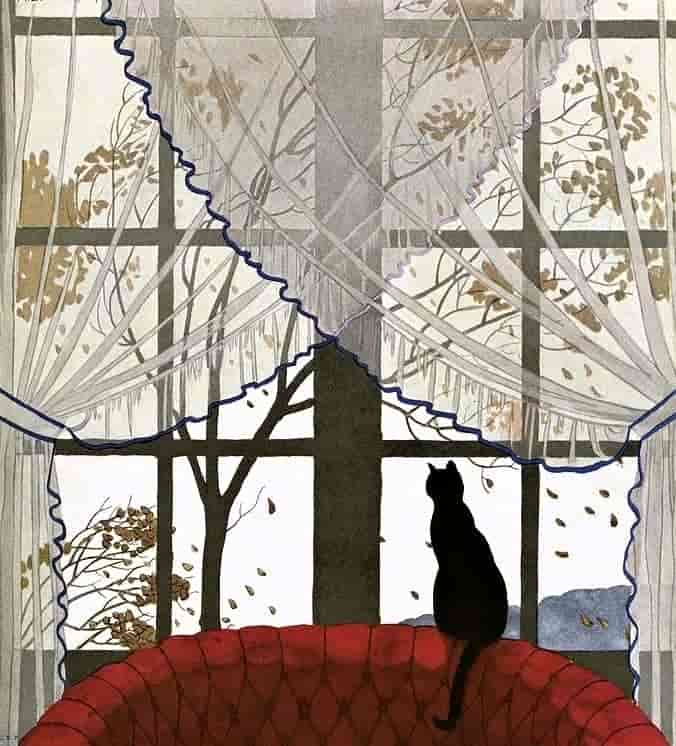

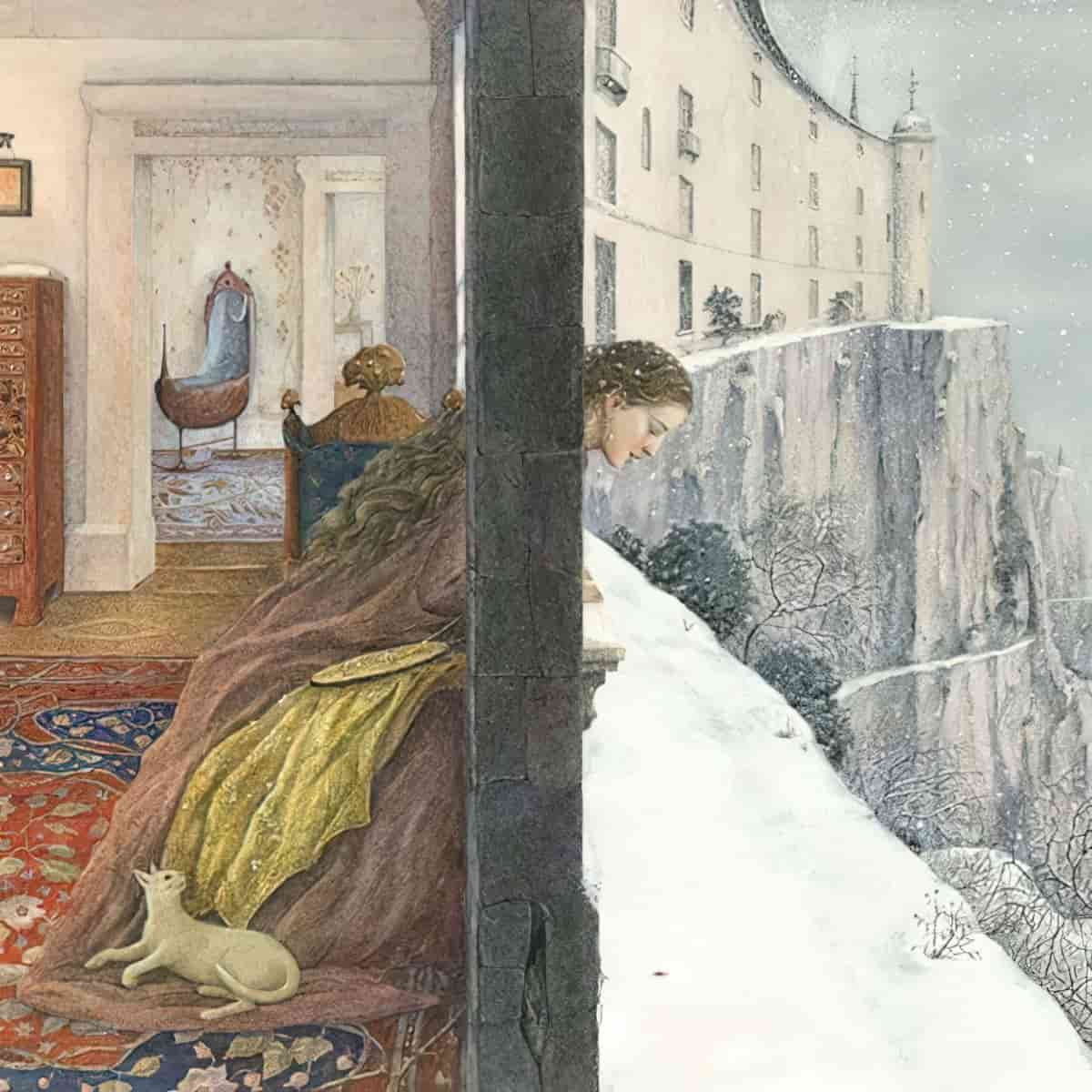

The window is a frontier between two spaces, highlighting any juxtaposition between interior and exterior. Typically, the inside of a house will feature technology and the outside will feature natural elements such as sunlight, foliage and suchlike. The window can symbolically bring them together, perhaps as a way of highlighting the difference.

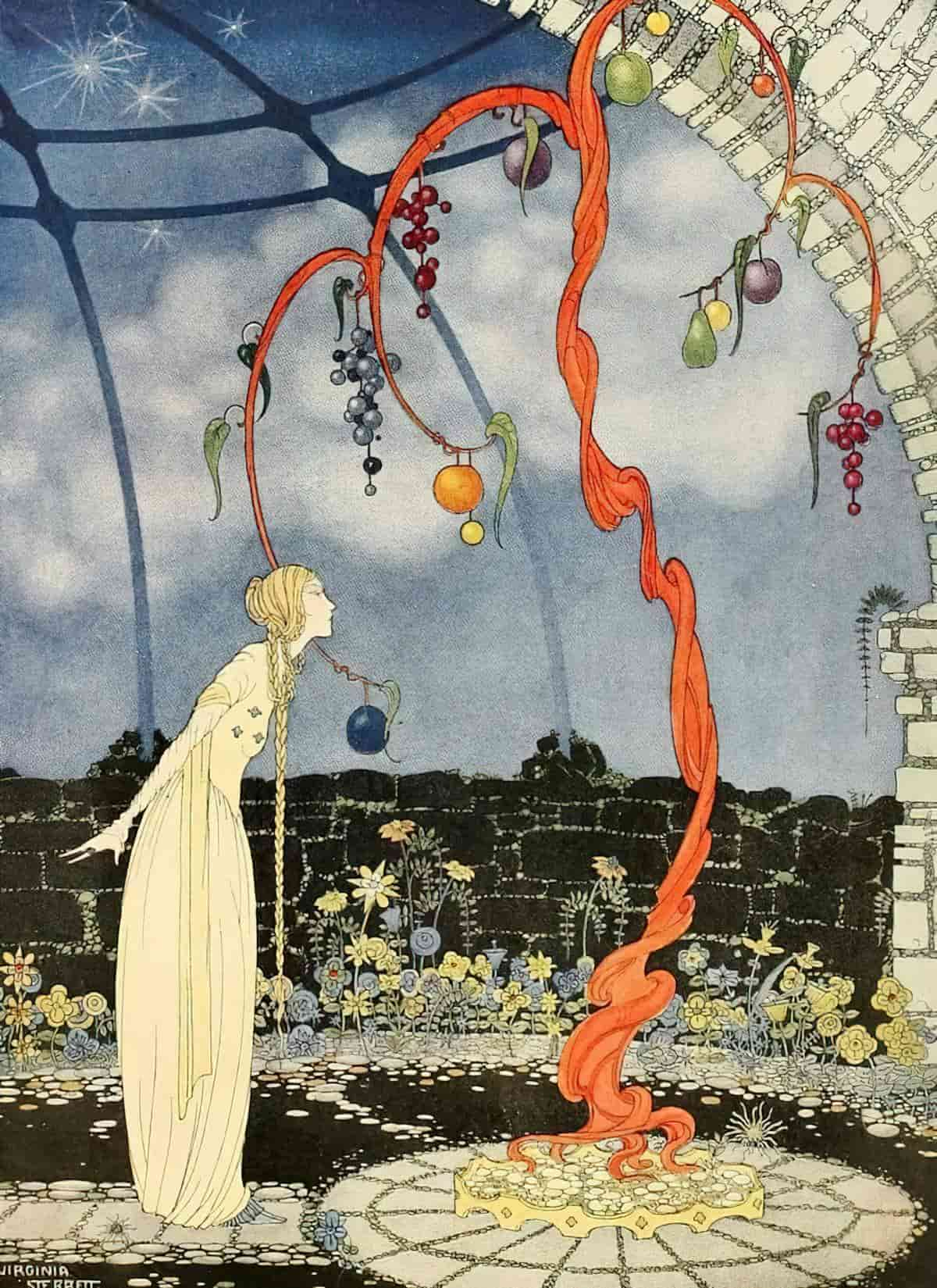

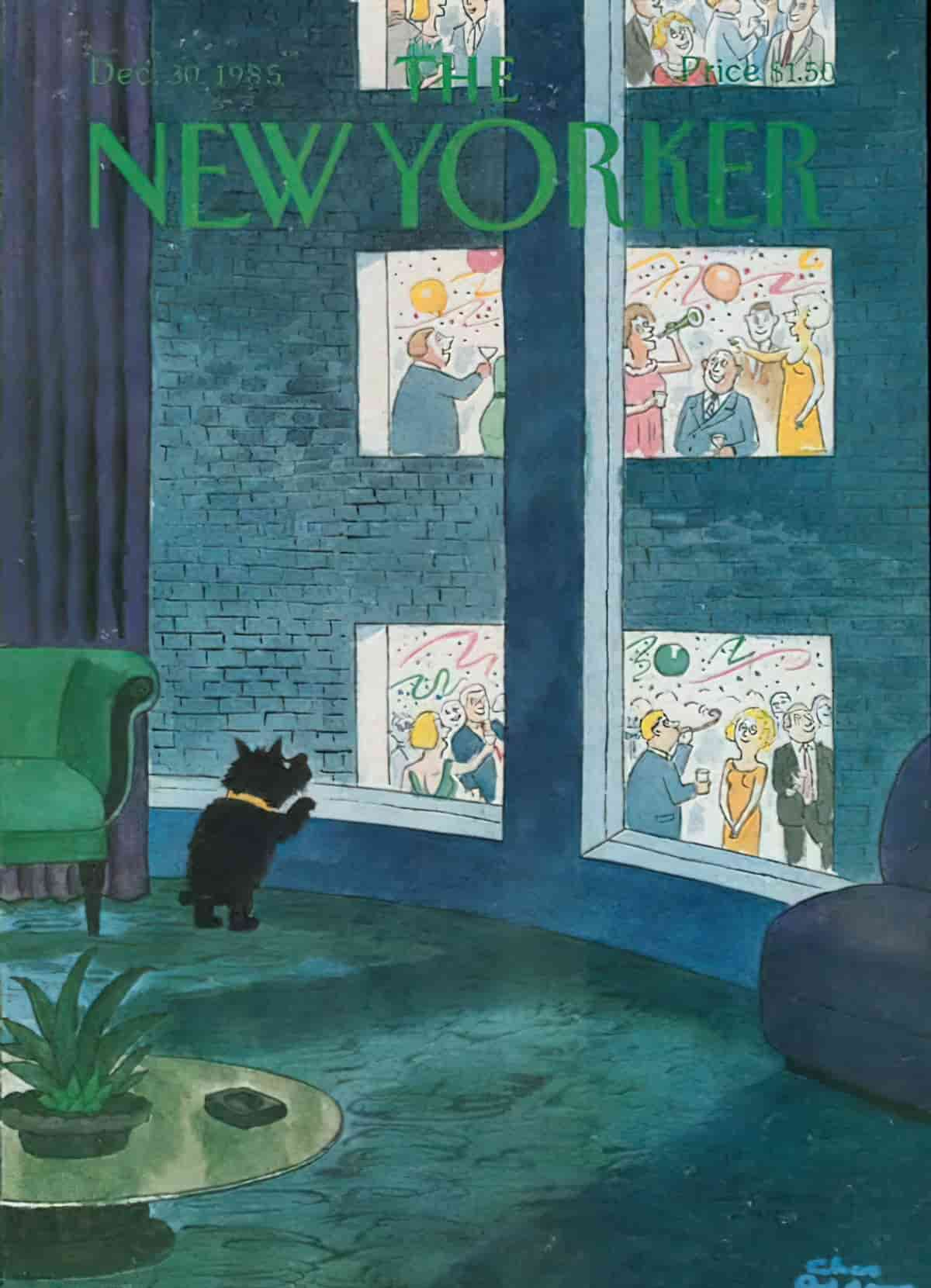

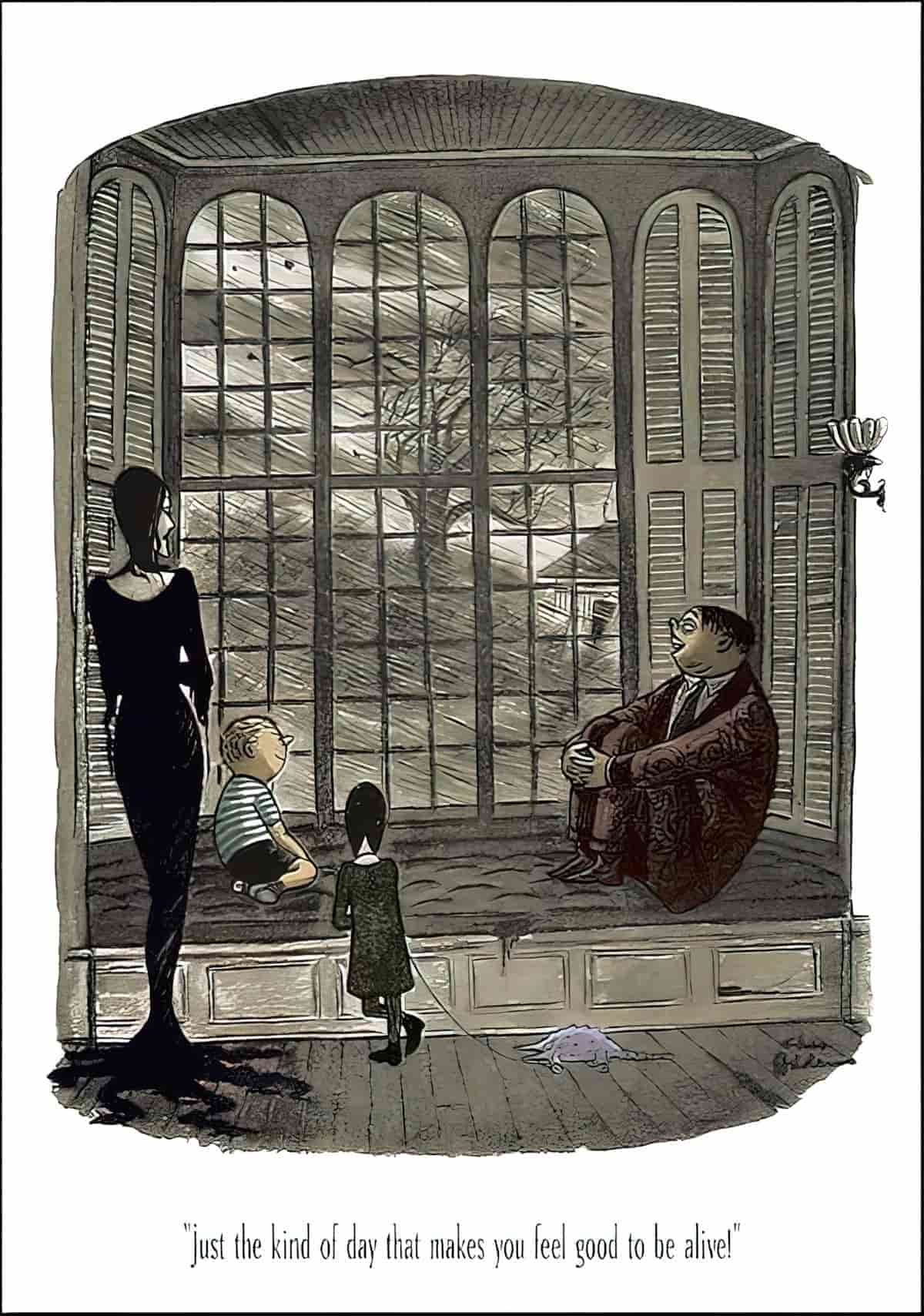

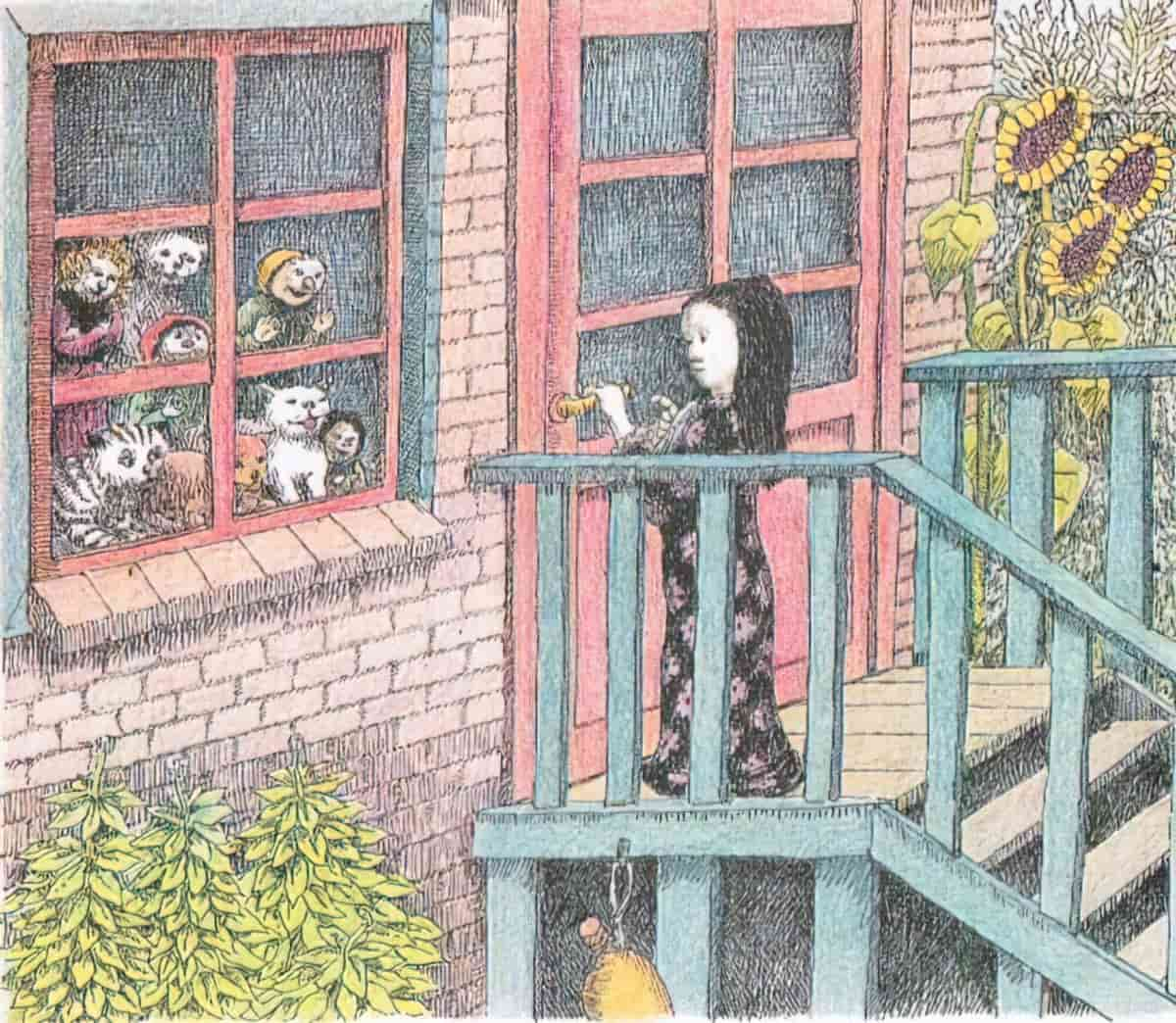

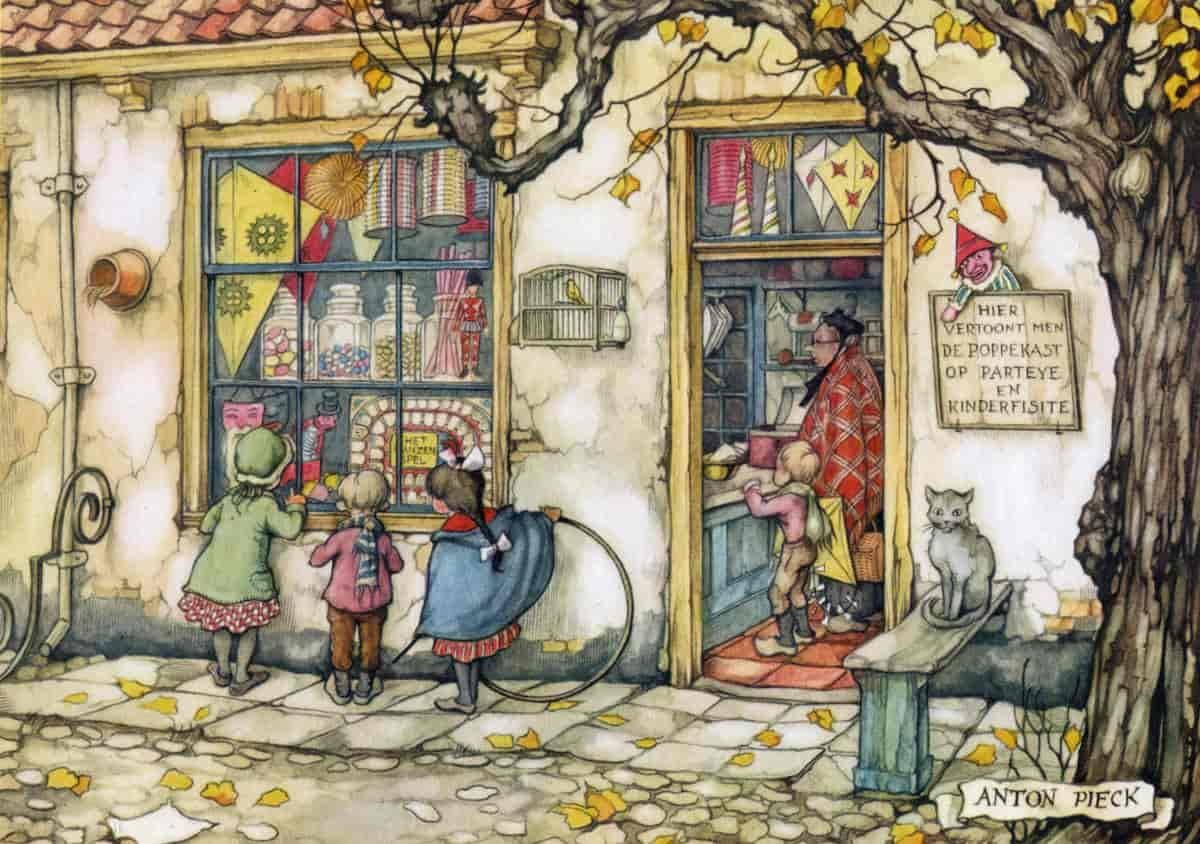

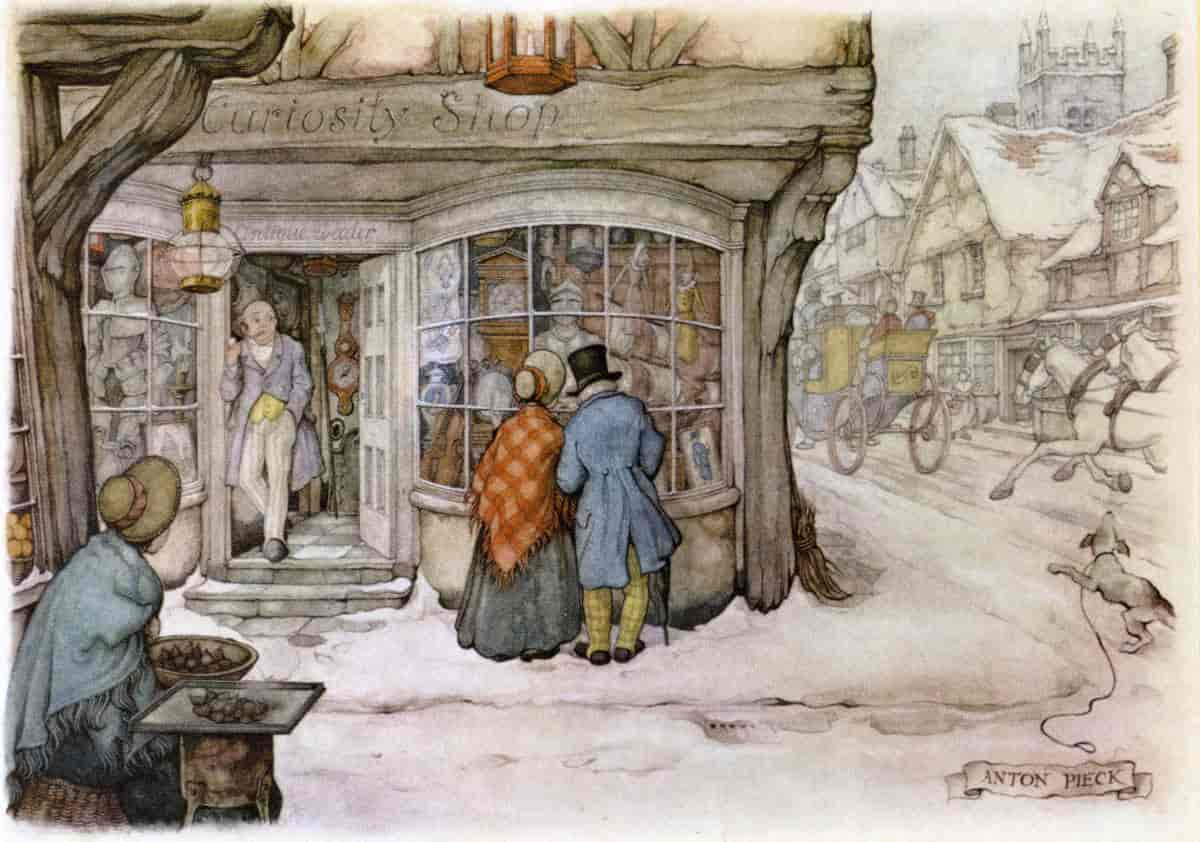

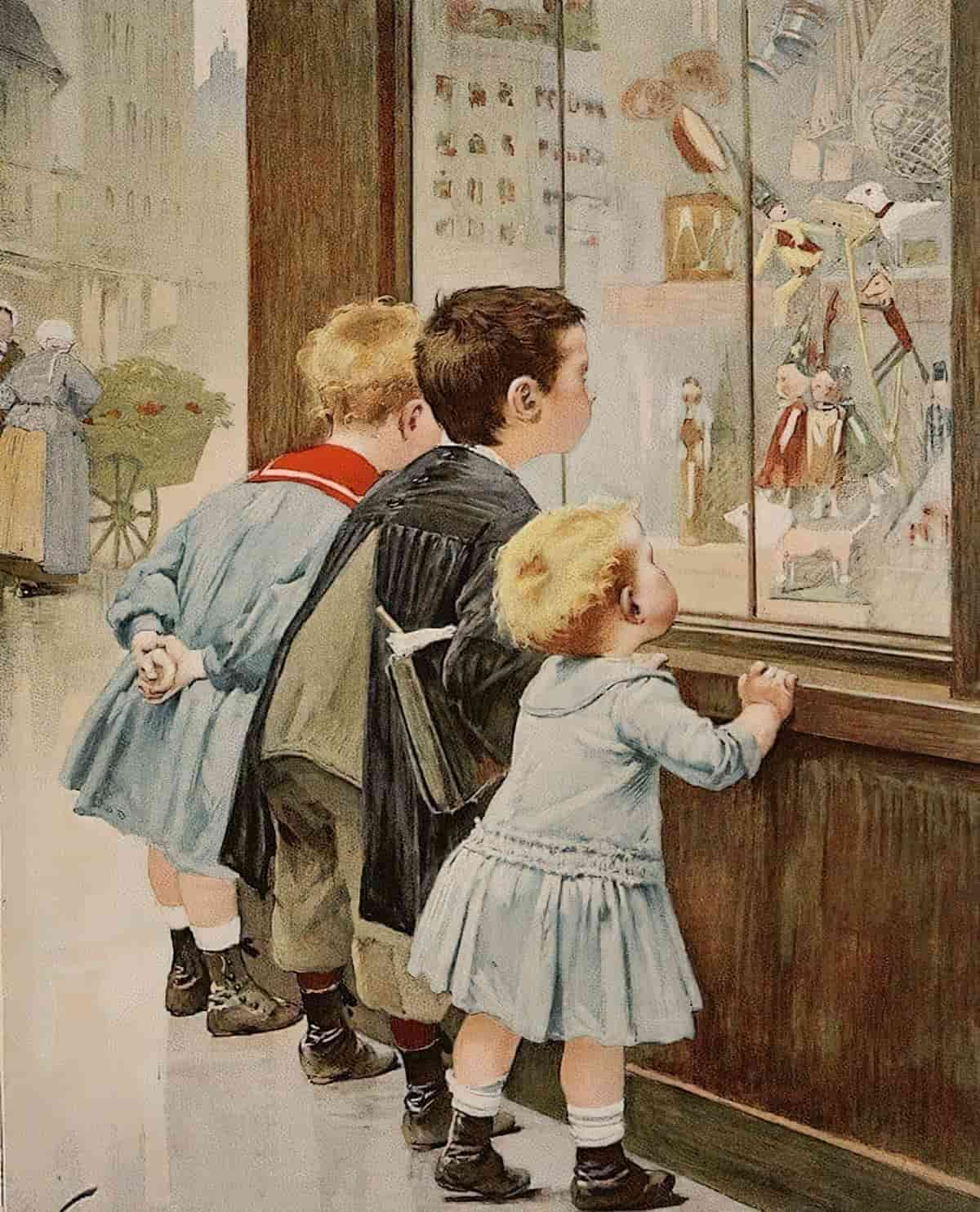

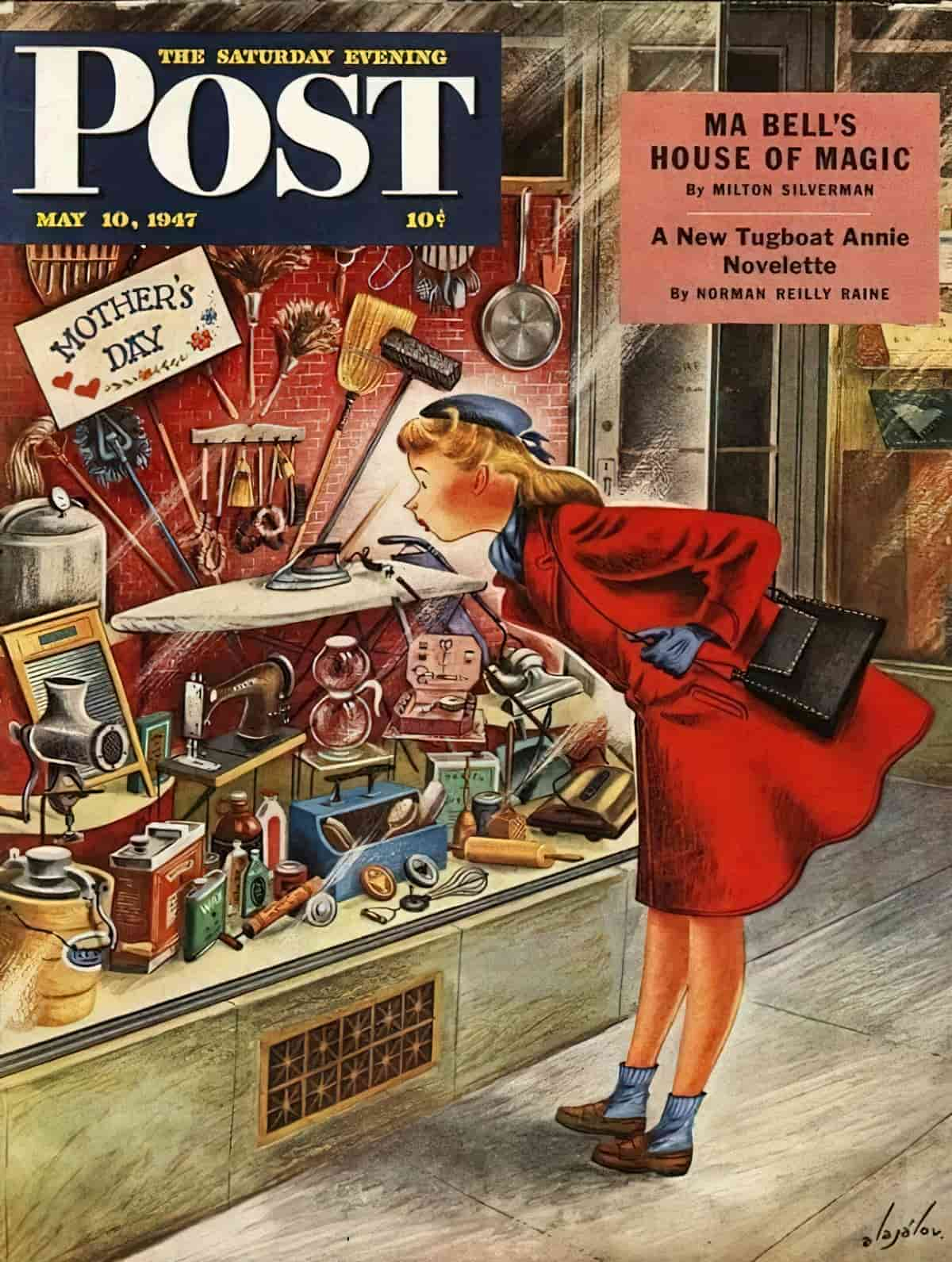

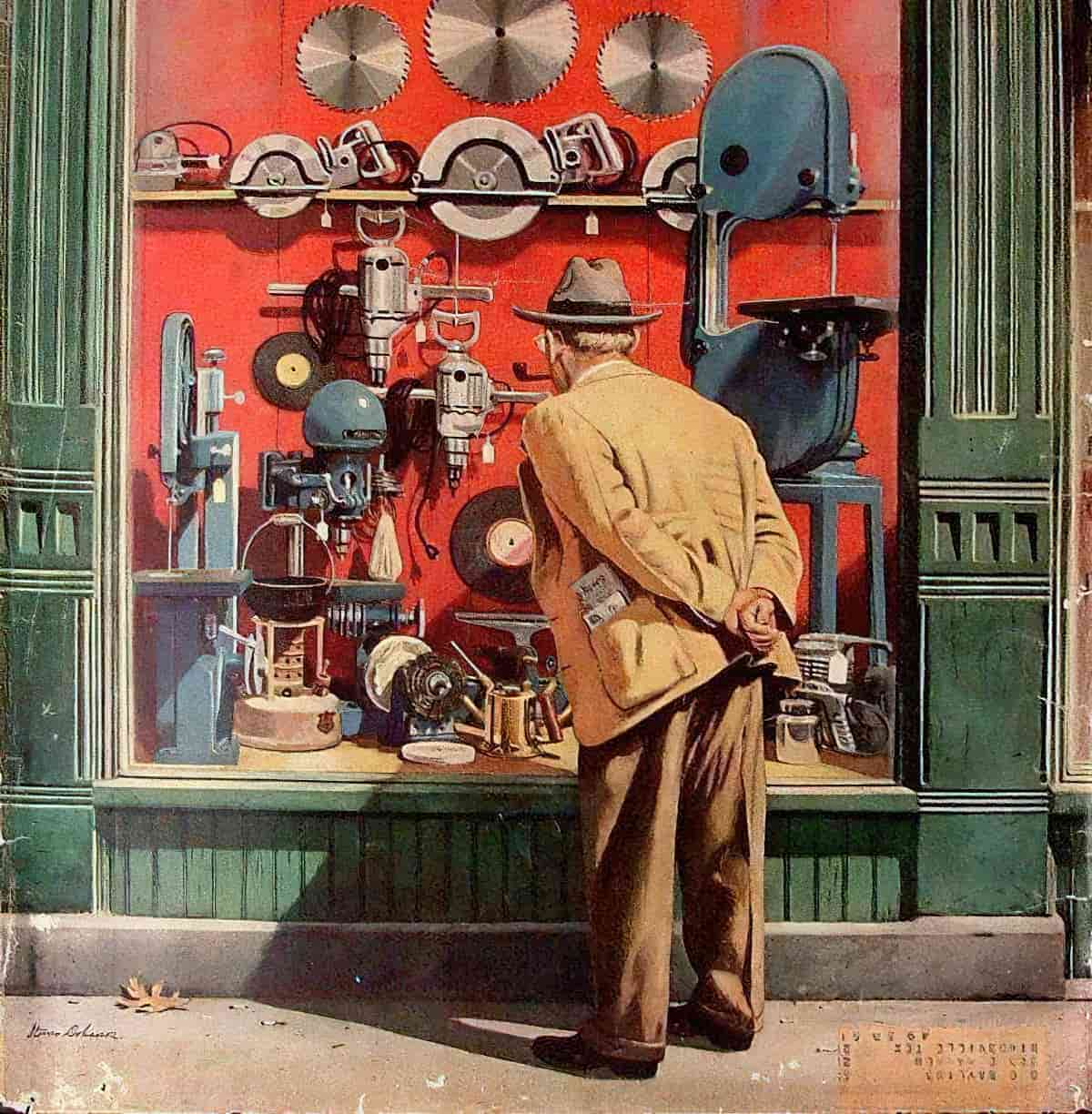

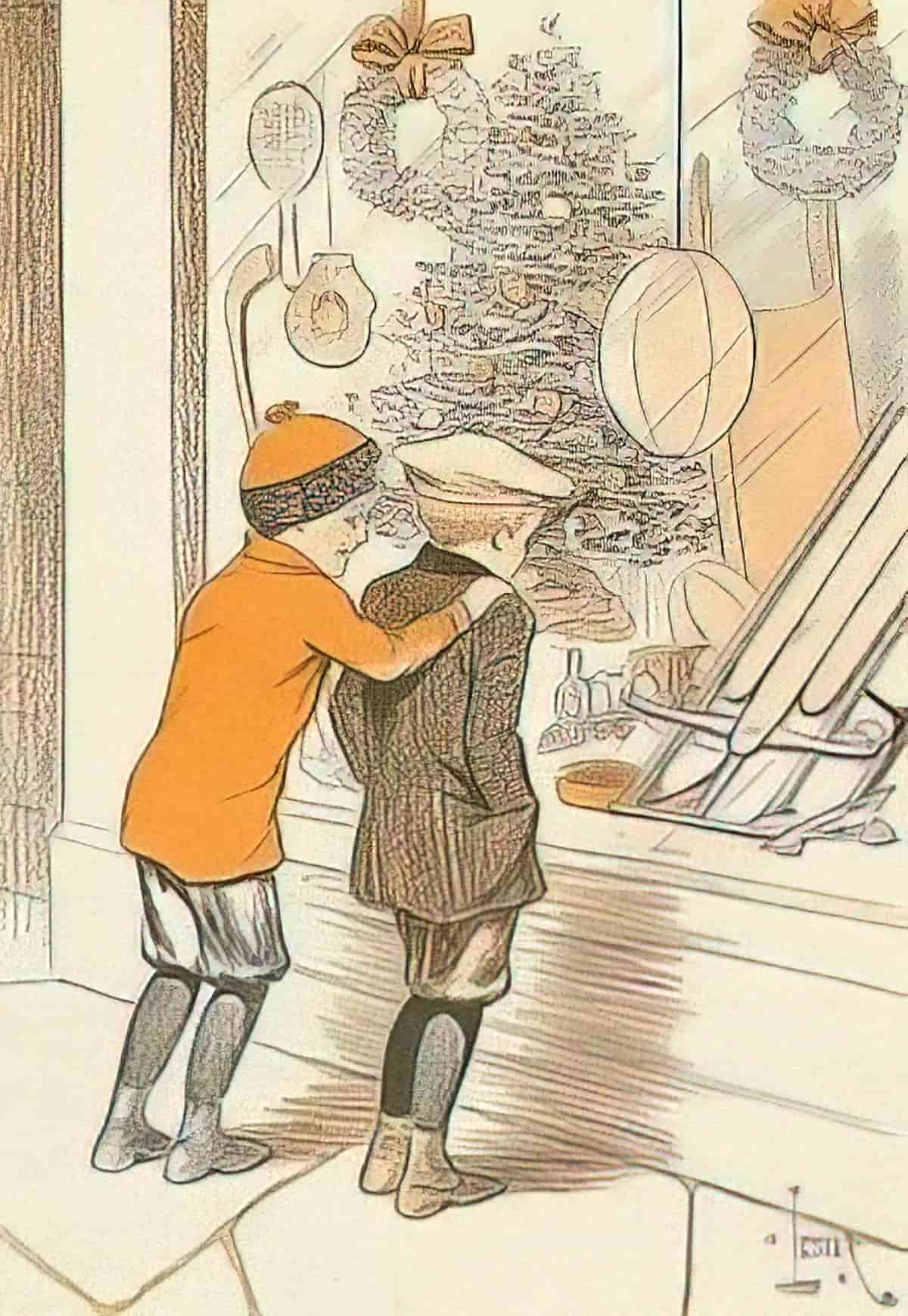

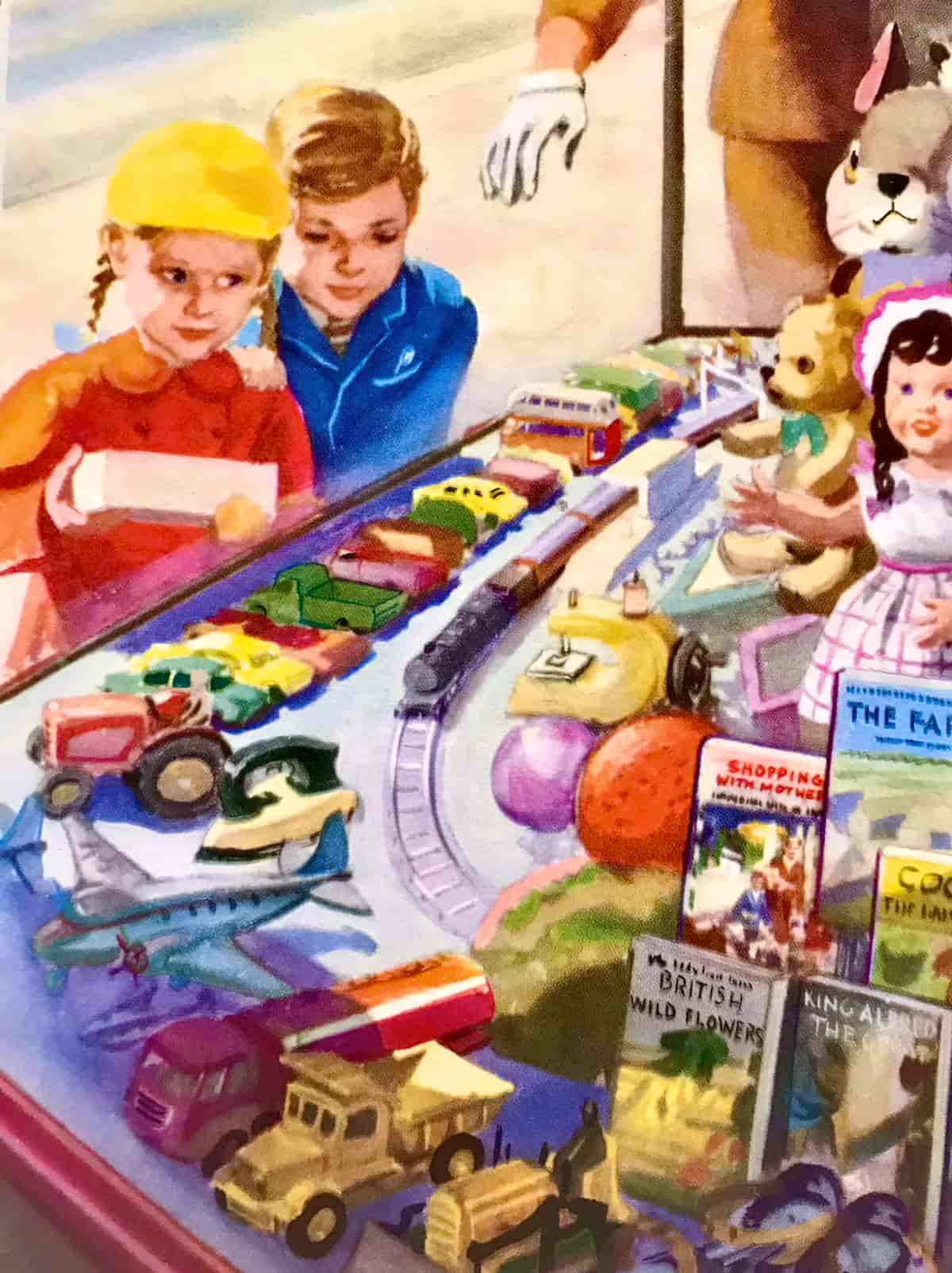

Below, the audience gazes through the window. We know we will never be admitted. This is a separate world.

[By 1900] colors, fabrics and textures were lighter… Whites and pastels largely replaced browns, blacks, deep burgundies, greens, and blues in women’s dress, and the materials were often much airier and more porous. Lace (now produced relatively inexpensively on factory machines) was used abundantly. It was made into bodices (the “Edwardian blouse” was often a rather frothy affair) or sometimes whole dresses, and it was used for trim on garments and accessories. It was also important for the first time as a fabric for undergarments. Lace also found its way into the interior, and significantly, it was particularly popular as a window treatment. Lace curtains were multivalent symbols. Visually, they offered a sense of translucency and a play of light that was not unlike what the impressionists were experimenting with. They also stood for or reflected the greater permeability that existed between “the outside world” and the home at the turn of the century; just as women were following Frances Willard’s precept of “making the whole world homelike,” they were concomitantly bringing the outside in. Some of this was conceptual, but some was literal, for they brought in an increasing amount of plant life, sunshine, and air. Lace curtains also signalled to the passer-by the strength of the feminine presence in the home, demonstrating the woman’s housekeeping skills and social aspirations and indicating her artistic refinement. Even beyond this, the lace also resonated as a particularly intimate fabric, as it now carried associations with lingerie. Because these were personal garments that were most closely in touch with the woman’s body, it is also reasonable to assert that hanging lace curtains in the window signalled a subtle but symbolically important identification between the home and body.

Beverly Gordon, Woman’s Domestic Body: The Conceptual Conflation of Women and Interiors in the Industrial Age, 1996

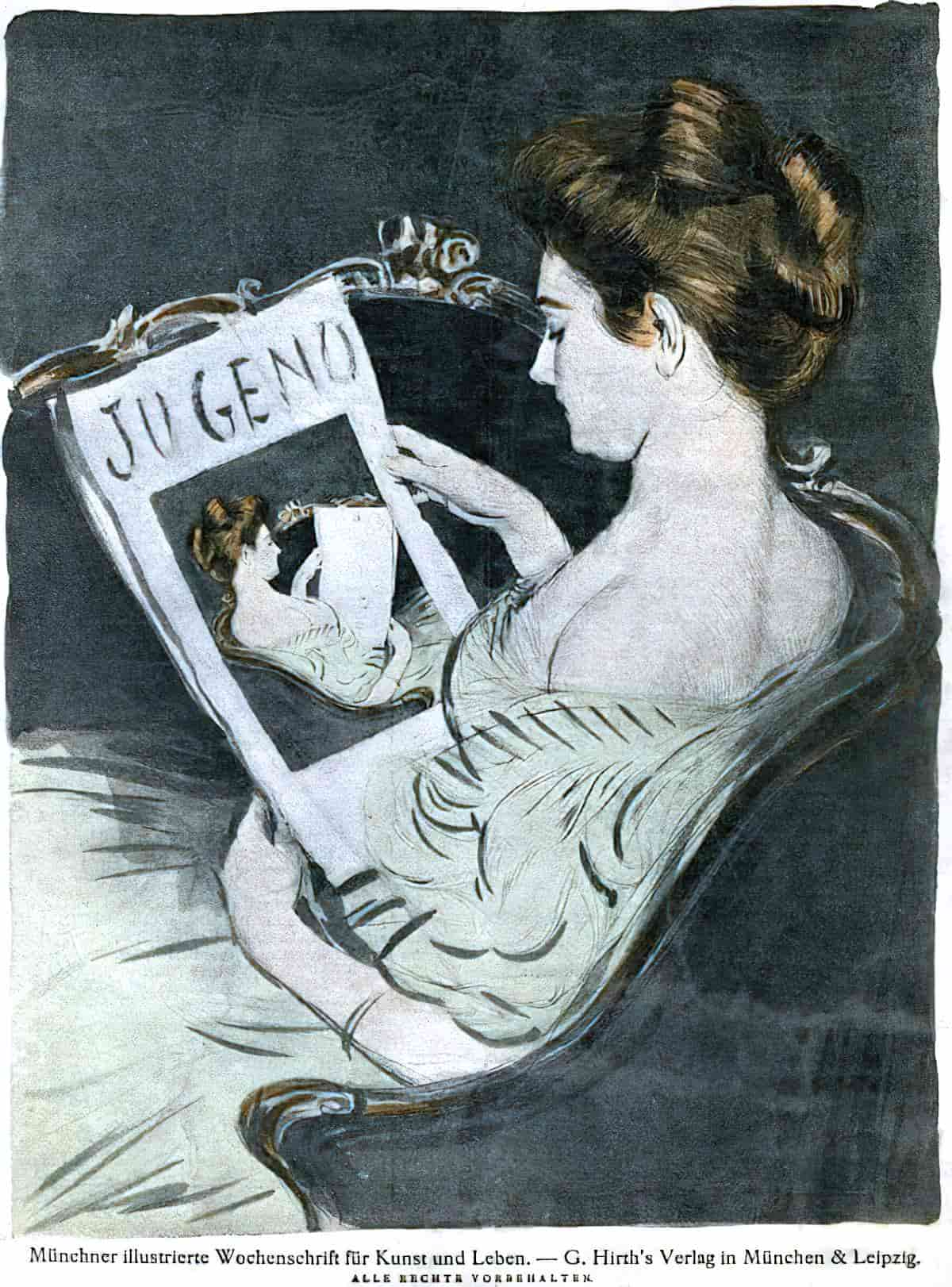

WINDOW AS REPRESENTATIONAL (CF. PRESENTATIONAL)

When we look through a window, we feel as though we are looking at a picture. We know what we see is real, but we don’t feel it as keenly as if we were standing without a glass pane and frame between us and the vista outside.

Consider again how the window is like a painting/picture or a mirror. With both paintings and mirrors, we have the contradiction of a visual presence but a physical absence. What we see does not really exist.

WINDSHIELD BIAS

Here is some real-world evidence that what exists beyond the window is regarded differently.

Psychologists who study driver behaviour use the term ‘windshield bias’ to describe the condition in which drivers prioritise travel by car while becoming annoyed with cyclists and pedestrians.

Sitting behind their windows, drivers feel removed from ‘the collective ‘(people just trying to get from A to B) and lose empathy. Drivers tend to treat others with less consideration than if they met them face to face, without the ‘protection’ of the windshield.

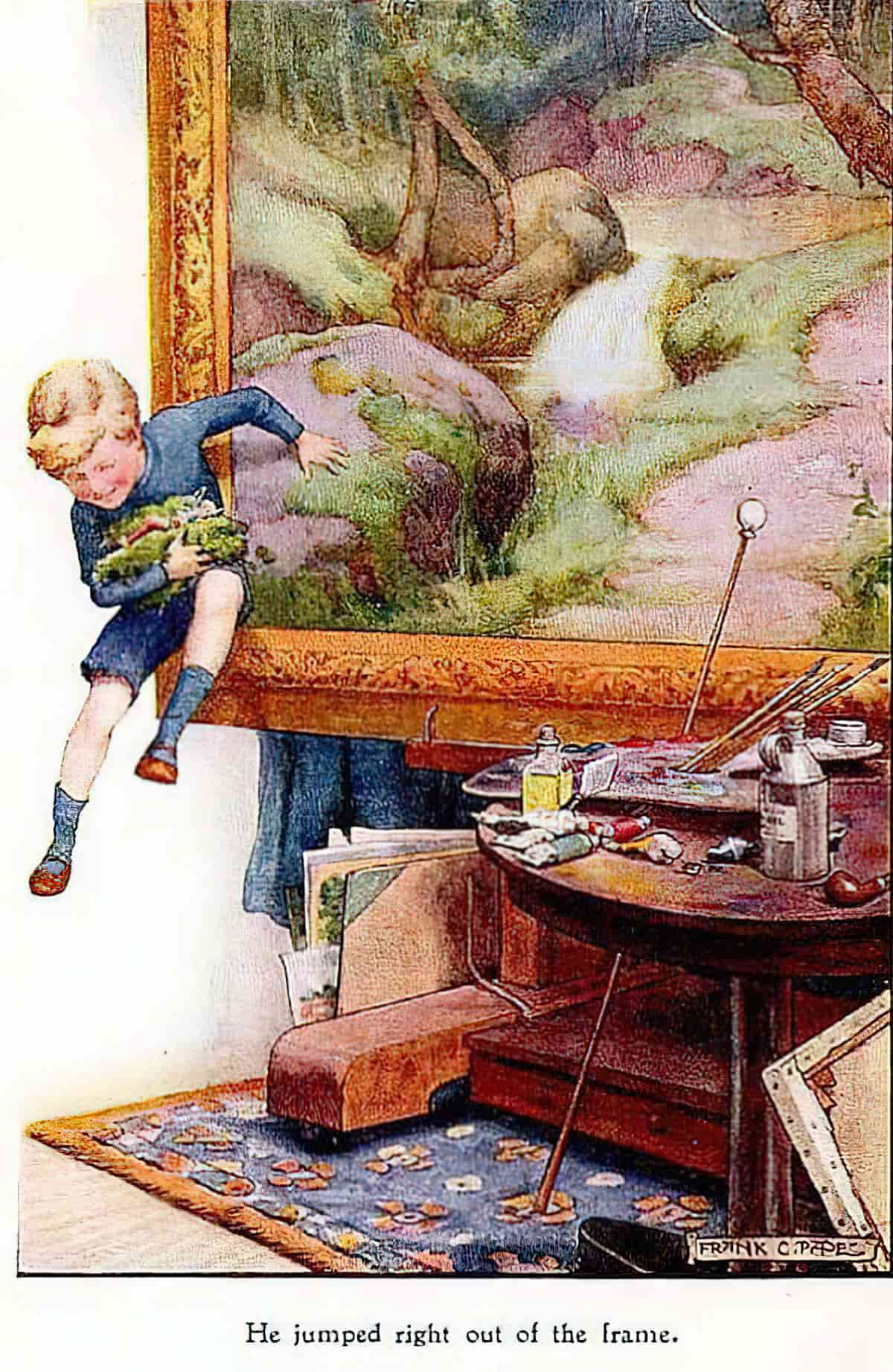

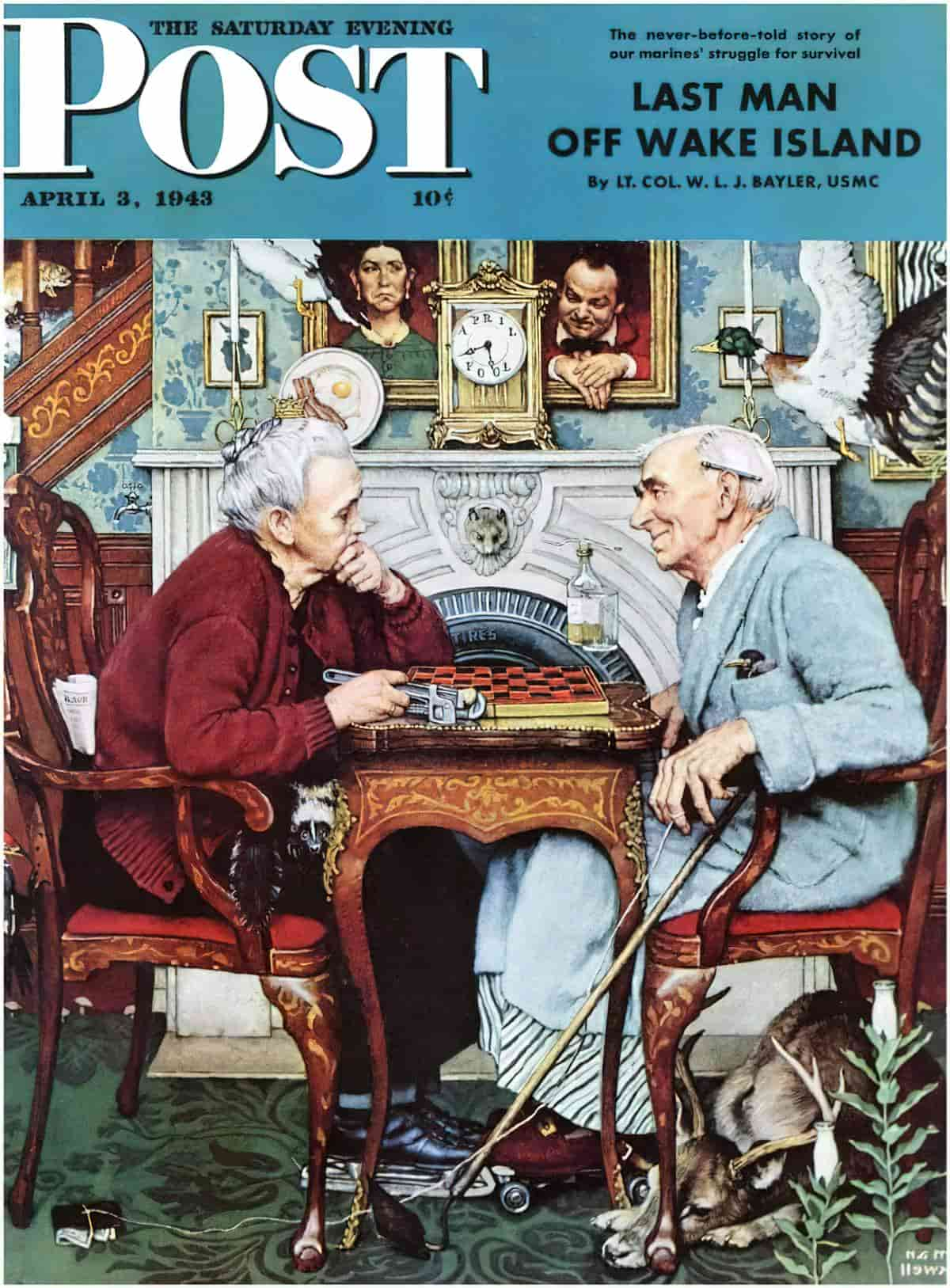

BREAKING THROUGH THE PICTURE PLANE: Trompe-l’œil

In general, art is ‘a window’ into another world or another vista. Some artists take this idea and run with it.

People emerging out of pictures are an example of art known as Trompe-l’œil.

Trompe-l’œil (French for ‘deceive the eye’) is an art technique that uses realistic imagery to create the optical illusion that the depicted objects exist in three dimensions.

Wikipedia

But the standout example is perhaps Italian Renaissance artist Filippo Lippi. Take a look at the painting below. The viewer considers the frame an open window in a pictorial illusion with Madonna sitting in the same room as us. (This painting would have felt like a miraculous mind-blower to a 1400s audience.)

But there’s also something self-conscious about the illusion in paintings such as that. It’s the pictorial equivalent of metafiction. By breaking the fourth wall, the painting serves to remind us that we are looking at an illusion. However, commentators feel that Filippo Lippi painted images like these because he was interested in the illusionary aspect of window metaphor. He wanted to create continuity between viewer and image, not break it. The Virgin Mary is positioned between viewer and picture plane. This places her in some intermediate (liminal) space. All of this emphasises the permeable nature of the window/picture frame as window.

THE WINDOW REFLECTION

This is a screen trope. Below is a screen capture from The Homesman. This is a trick often used by film directors as a way of showing an actor’s face and what the character is looking at simultaneously.

WINDOWS AND CHARACTERIZATION

COLD HOUSES MADE OF GLASS

Storytellers typically use houses to illuminate character, or how a family relates to each other. For example, a family who lives in a warm, cosy home which is slightly chaotic (but not too chaotic!) is probably a healthy one. In contrast, a wealthy family who live in an architecturally designed building with many cold, glass surfaces is probably not functioning very well. Not only that, something bad is about to happen. The many windows of their house exposes them to outside threat.

For champions of architectural modernism in the early decades of the twentieth century, the extensive use of glazed fenestration was a hallmark of what they audaciously termed the International Style. This new architectural idiom, characterized by vitreous expanses envelopoing openwork structures of steel and reinforced concrete, first emerged in Germany, France, and the Netherlands. Only since the Second World War, however, has the style truly come to live up to its ambitious name. […] In the words of one contemporary critic, such modernist architecture disregards the “contingencies of climate and the temporally inflected qualities of local light,” with the goal of imposing “a condition of absolute placelessness” in these disparate geographies. As a result of this global triumph, the near-universal spread of window glass — and the architectural transparency to which it has given rise — is now perceived as a paradigmatic expression of the modern era.

Towards a Cultural Ecology of Architectural Glass in Early Modern Northern Europe by Morgan Ng

For more on that see Homes and Symbolism.

GLASS HOUSES AS EVIDENCE OF SHOWY, WEALTHY INHABITANTS

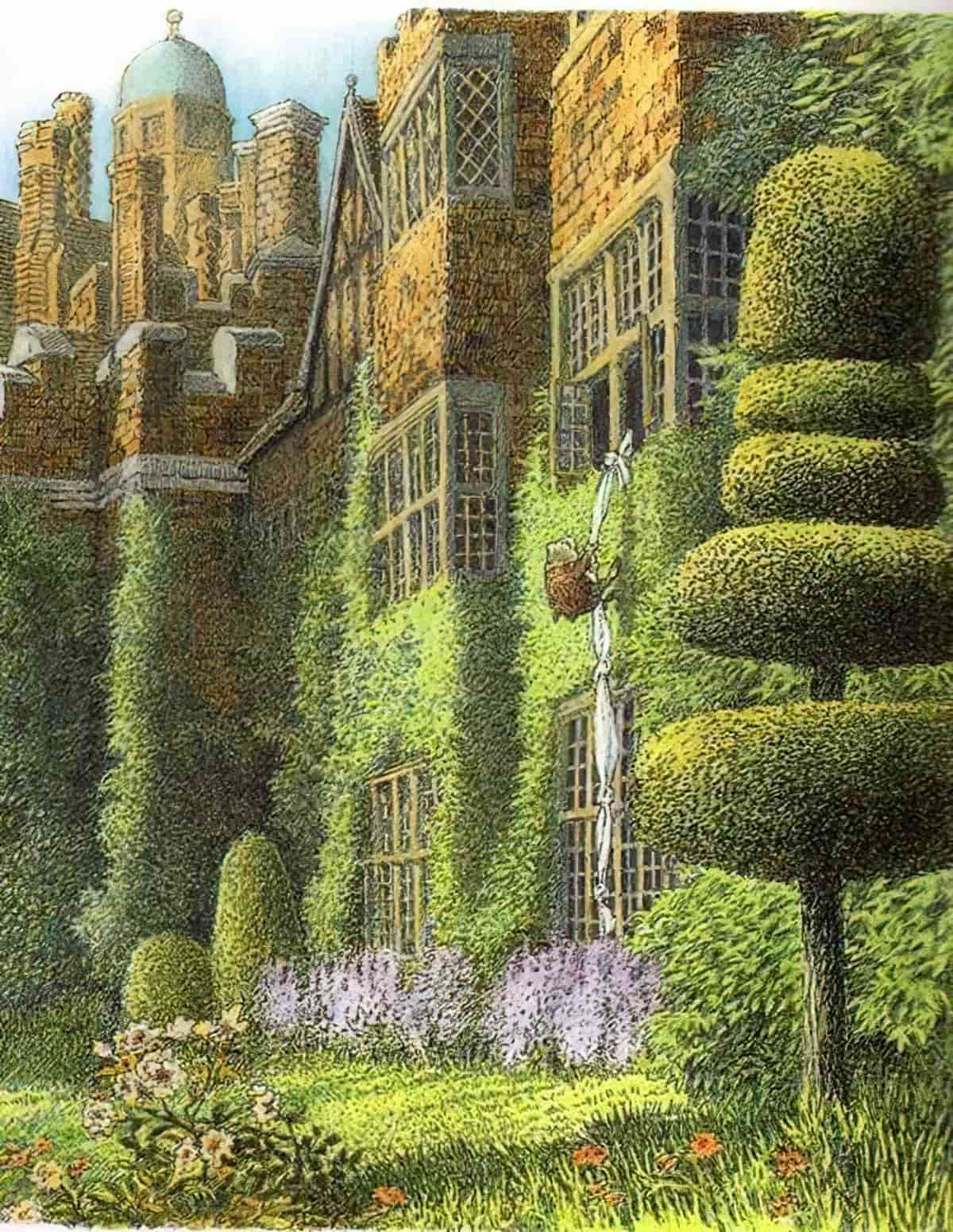

By the way, houses made with a whole lot of glass are not new. In 1500s England (the Elizabethan period), wealthy people might build a so-called ‘lantern house’ or ‘glass house’. These houses often had a ‘prospect-room’, meaning a room with lots of glass and a great view.

The first was Longleat, rebuilt four times between 1547 and 1580 by English architect Robert Smythson for his most showy clients, in this case for Sir John Thynne. The Longleat mansion had a bay window three storeys high. It was built high on a hill where people could admire it for miles around, especially at night with the lights glowing. Hence the name ‘lantern house’. Another of Smythson’s lantern houses, Wollaton, lit up the whole of Nottingham, showing off the wealth of its owner. Glass was extremely expensive. So was heating and lighting.

Hardwick Hall in Derbyshire is another good extant example which you can visit, also designed by Robert Smythson. He designed this house in the 1590s for Elizabeth Hardwick, Countess of Shrewsbury and ancestress of the Dukes of Devonshire, shrewd businesswoman and the second richest woman in England after the actual Queen.

Unfortunately, the English climate is not well-suited to all that glass, especially when glass technology was such that it easily shattered. These lavish rooms of glass were criticised by people like Sir Henry Wotton and Francis Bacon, who declared the north too cold for all that glass; the south too hot. People commonly said at the time: “Hardwick hall, more glass than wall,” which was surely supposed to say something about Bess Hall herself, for desiring and acquiring such a residence.

Of course, today these houses do not seem to be excessive in the amount of glass. Technology can now easily manage glass sheets many times the size of a human being, and many modern buildings are made of far more glass than the Elizabethan lantern houses, once considered ostentatious.

Even today, corner offices with many windows and a great view are a symbol of prestige, as are large, light-filled houses with a great panoramic view. When it comes to automobiles, 1955 is thought to be the peak of excess, both in style and horsepower. A good example is Plymouth’s 2-door hardtop, overpowered at 285 horsepower. Not coincidentally, it had more glass (and taller tail fins) than any of its competitors.

In some markets, the view rather than the house itself affords a property its high market value. Here in Australia, a view of Sydney Harbour from Bellevue Hill is the most prestigious (read: expensive) view in the country.

IS THE WINDOW OPEN OR CLOSED?

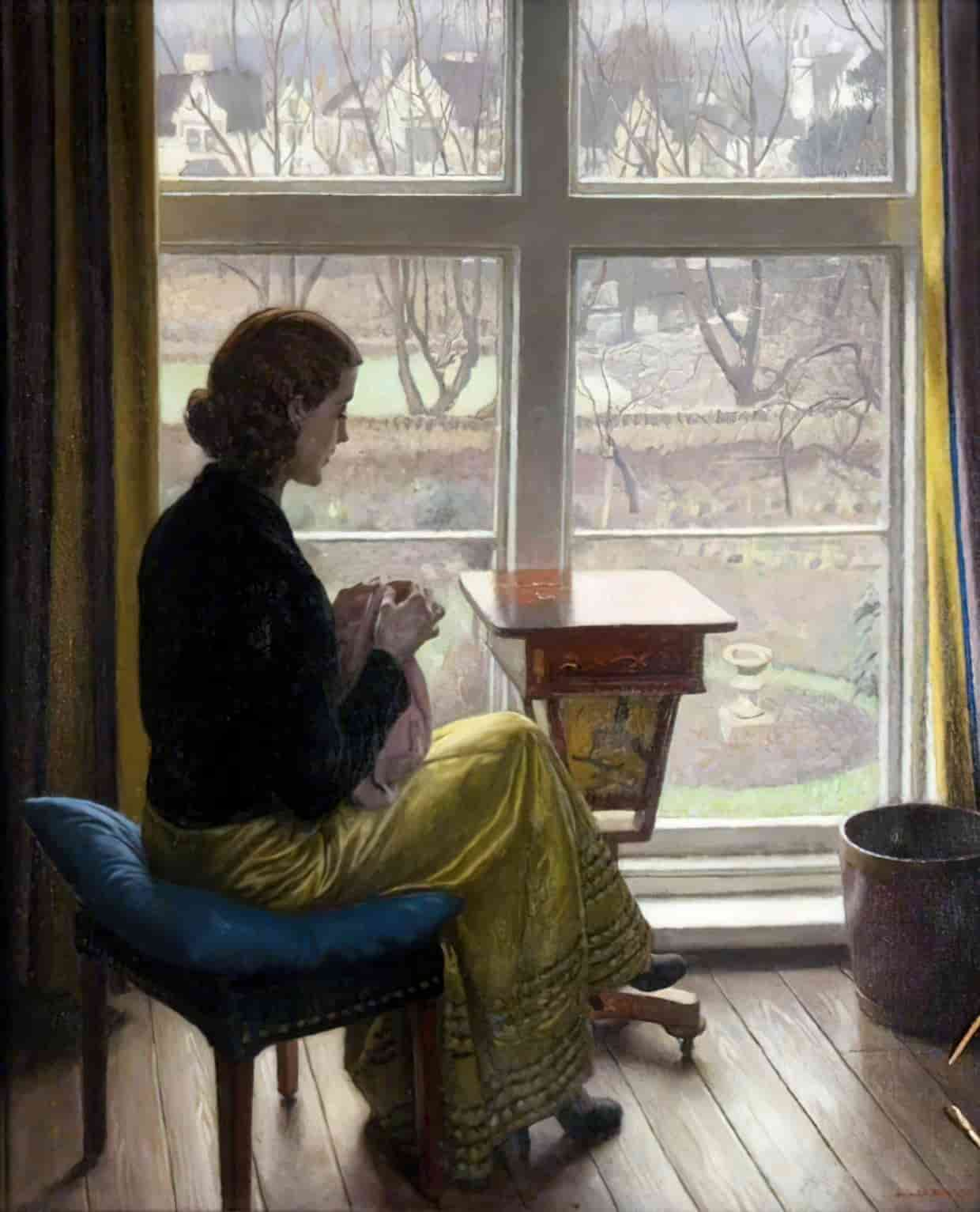

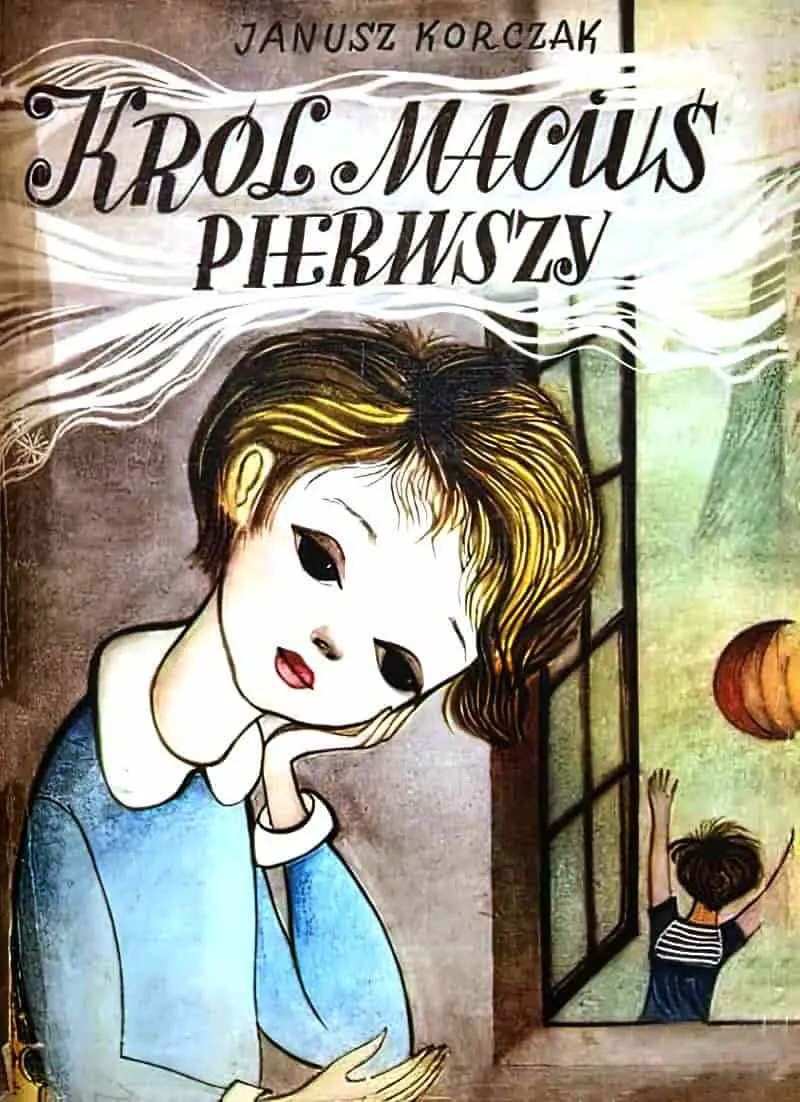

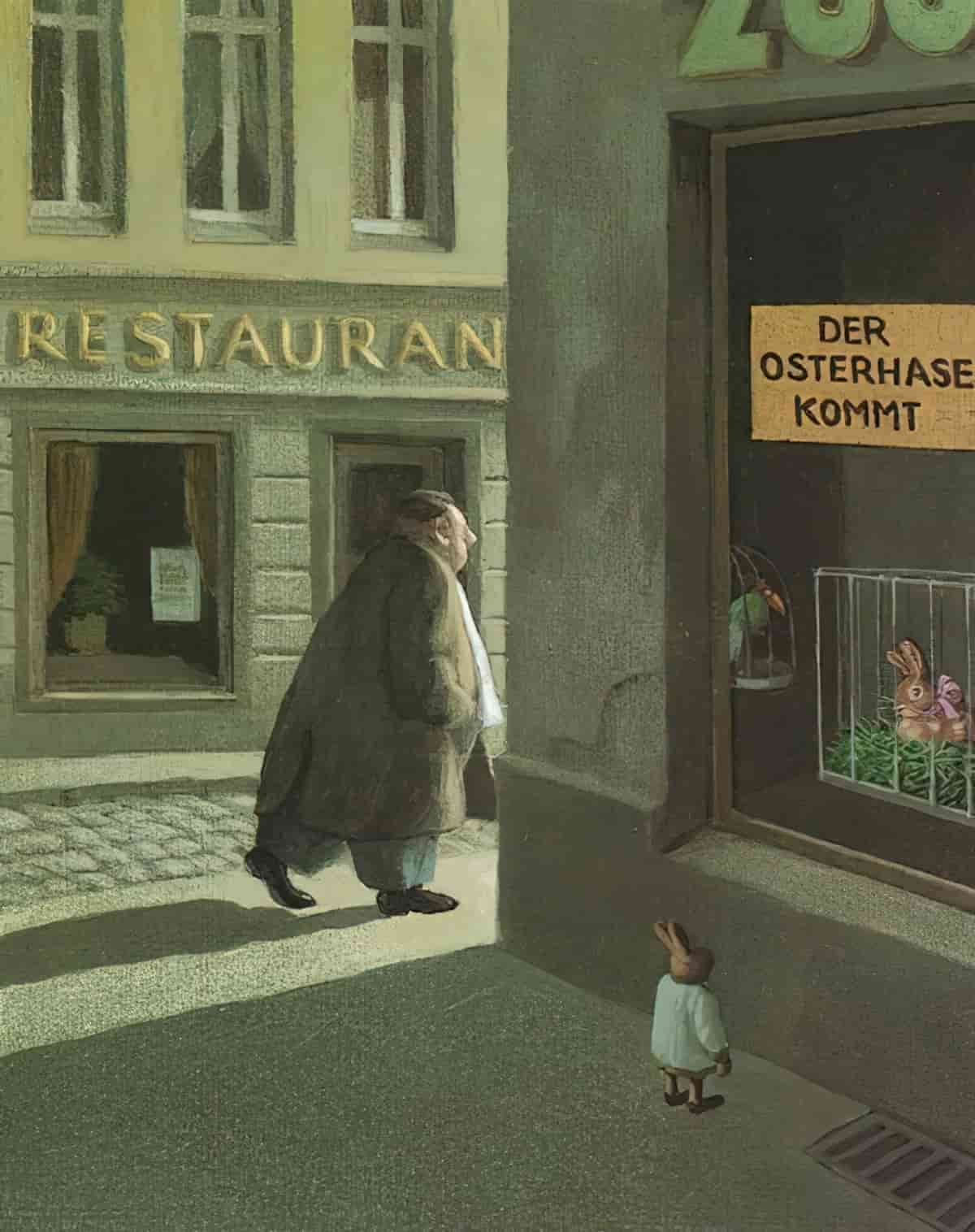

The state of a window may say something. For example, a closed window may indicate frustration or close-mindedness. If a character longs to join characters on the other side of the glass, that may indicate how alienated they feel from their environs. We might call this a within-without perspective. Are the windows grimy, clean, broken, fractured?

Do they look up at legs passing along the sidewalk or down onto a street? One takes on the symbolism of a basement, the other of an attic.

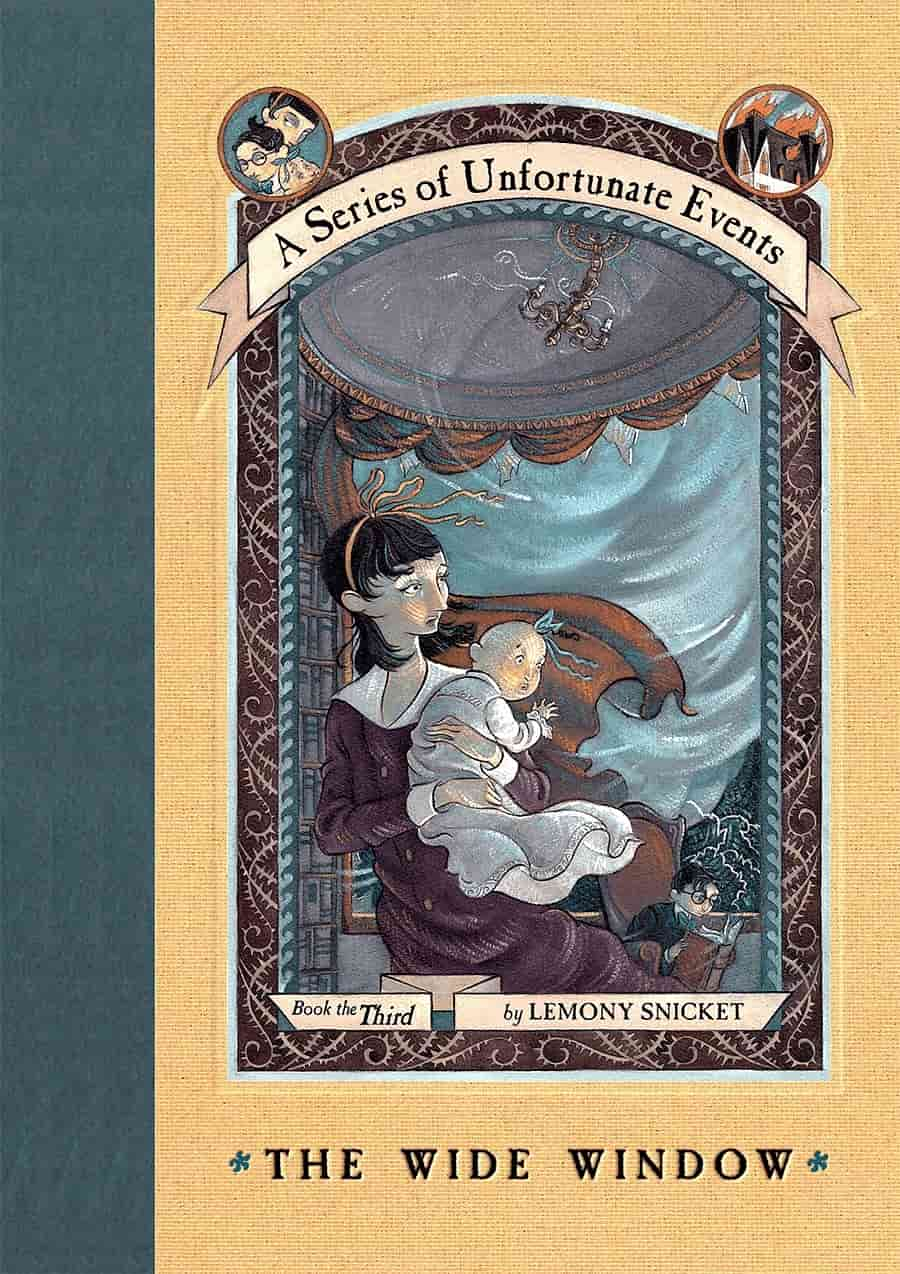

If you have not read anything about the Baudelaire orphans, then before you read even one more sentence, you should know this: Violet, Klaus, and Sunny are kind-hearted and quick-witted; but their lives, I am sorry to say, are filled with bad luck and misery. All of the stories about these three children are unhappy and wretched, and this one may be the worst of them all. If you haven’t got the stomach for a story that includes a hurricane, a signalling device, hungry leeches, cold cucumber soup, a horrible villain, and a doll named Pretty Penny, then this book will probably fill you with despair. I will continue to record these tragic tales, for that is what I do. You, however, should decide for yourself whether you can possibly endure this miserable story.

With all due respect,

Lemony Snicket

HORIZONTAL OR VERTICAL?

The shape of a window is significant in architecture and is sometimes worth considering in literature, too.

The horizontal “picture” window, or strip window, functions as an intermediary between the inside and outside of the house and is better at making its frame invisible. The house is a massive camera, pointed at its subject. The window is a sort of lens or screen.

If a landscape-shaped window offers a perpetual panorama, a long, tall window is better at distributing light. From inside the building we get a more complete view of the world, from the sky to the ground. The vertical window is also about the size and shape of a standing human, so feels a little more anthropological.

A vertical line is associated with erectness, or standing upright. A horizontal line is associated with lying down and therefore with death.

THE WOMAN (OR GIRL) UPSTAIRS

Until only a few decades ago, one of the most popular leisure activities in Europe was simply looking out the window. Consider Germany, where leisure has been the subject of sociological study for more than half a century: in the 1950s, gazing from windows ranked sixth in a list of favorite national leisure activities, surpassed only by reading, gardening, shopping, fixing up one’s home, and playing with one’s children. As those who grew up during that time recall, people would stand at their windows for hours and look out.

Daniel Jutte, 2016, Window Gazes and World Views

Jutte points out that few people consider ‘gazing out of a window’ a leisure activity today. We might blame screens for that — TV screens, because people stopped doing this in the 1960s. Today, if you stare out of a window, people will consider you odd, though this depends on culture.

Jemand ist weg vom Fenster

German phrase meaning ‘no longer at the window’; permanently gone, sometimes a euphemism for ‘dead’.

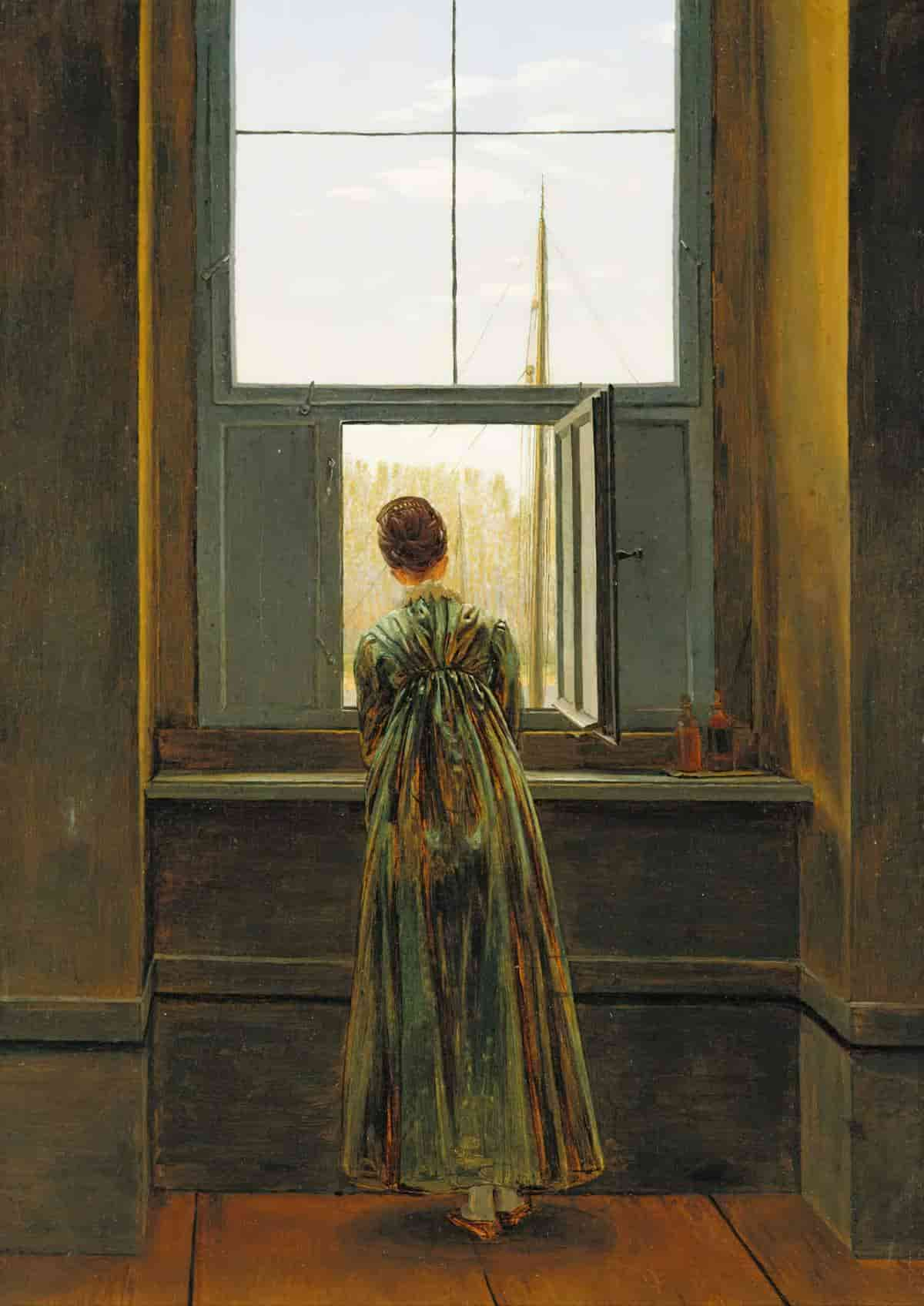

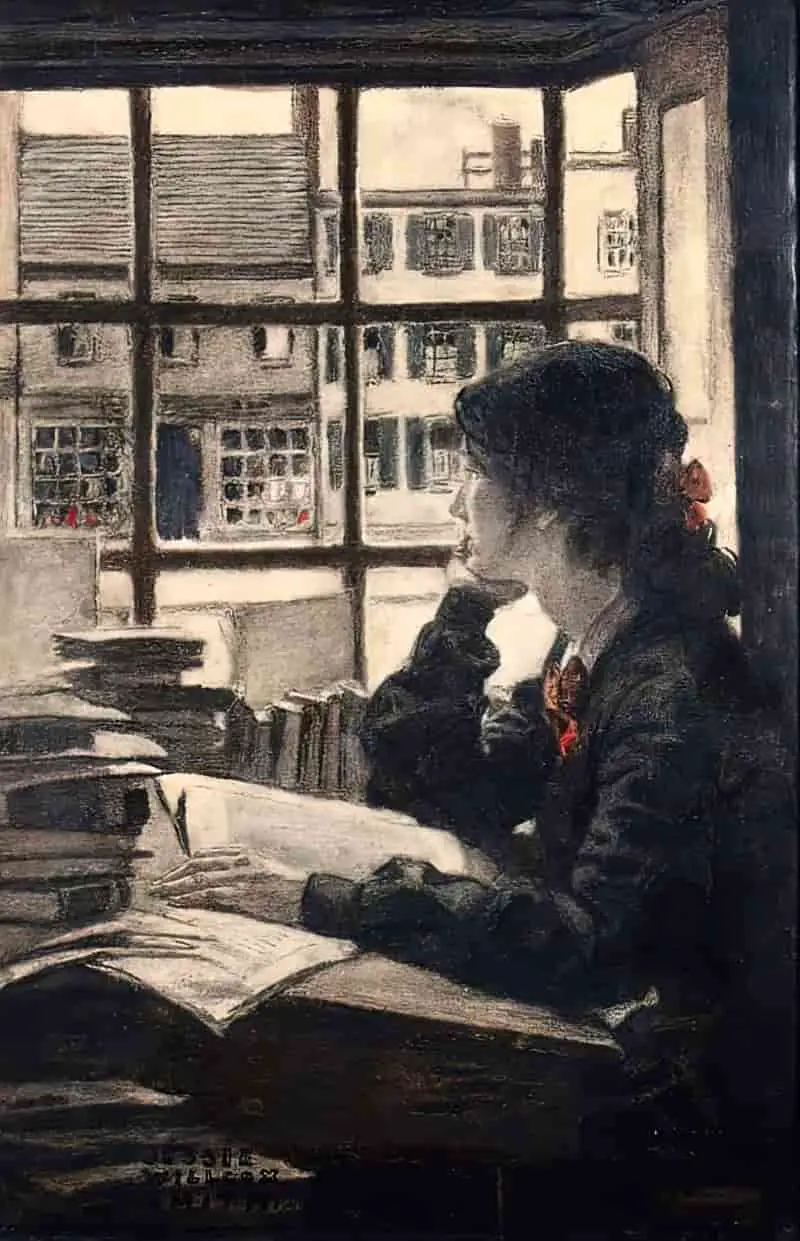

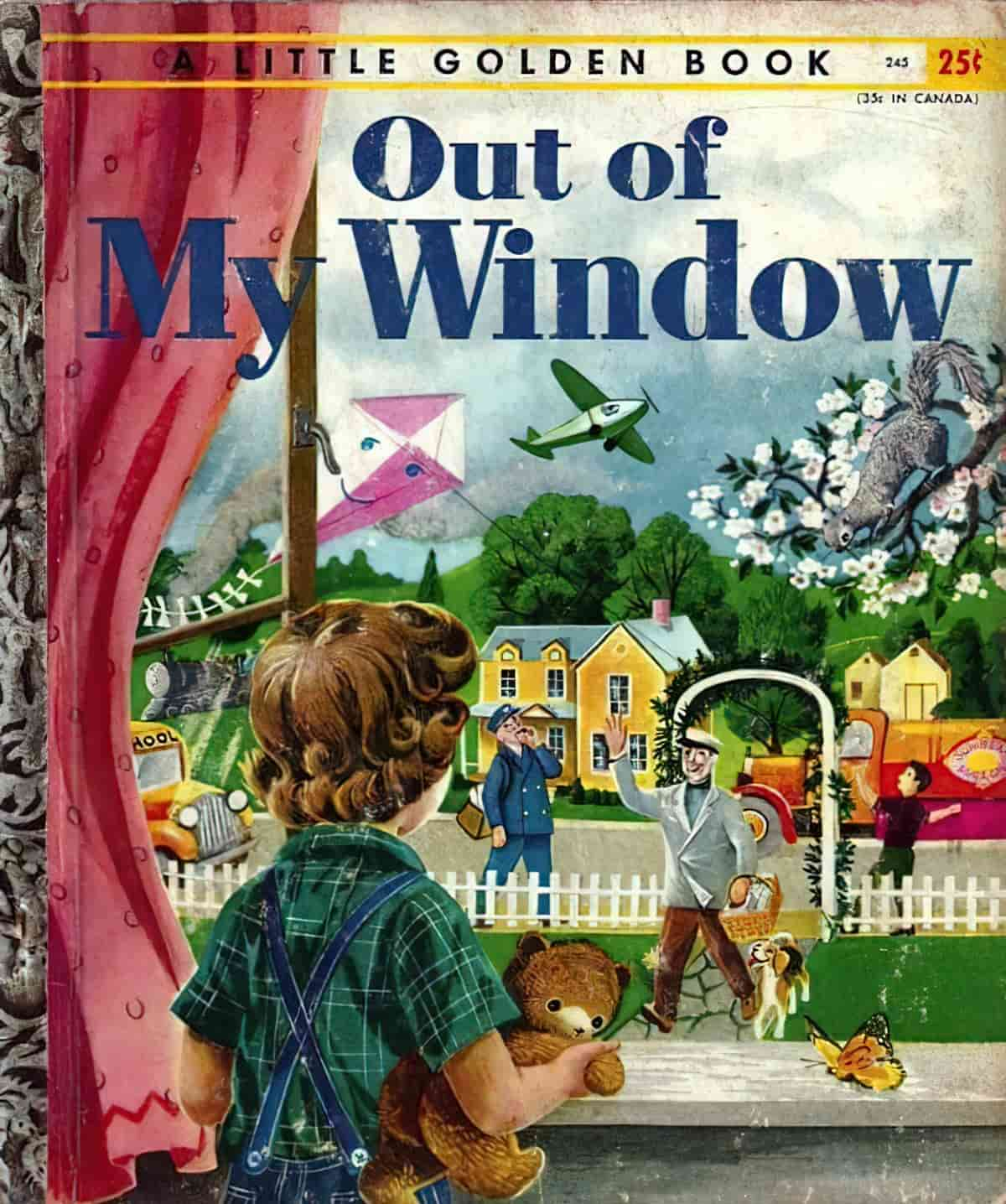

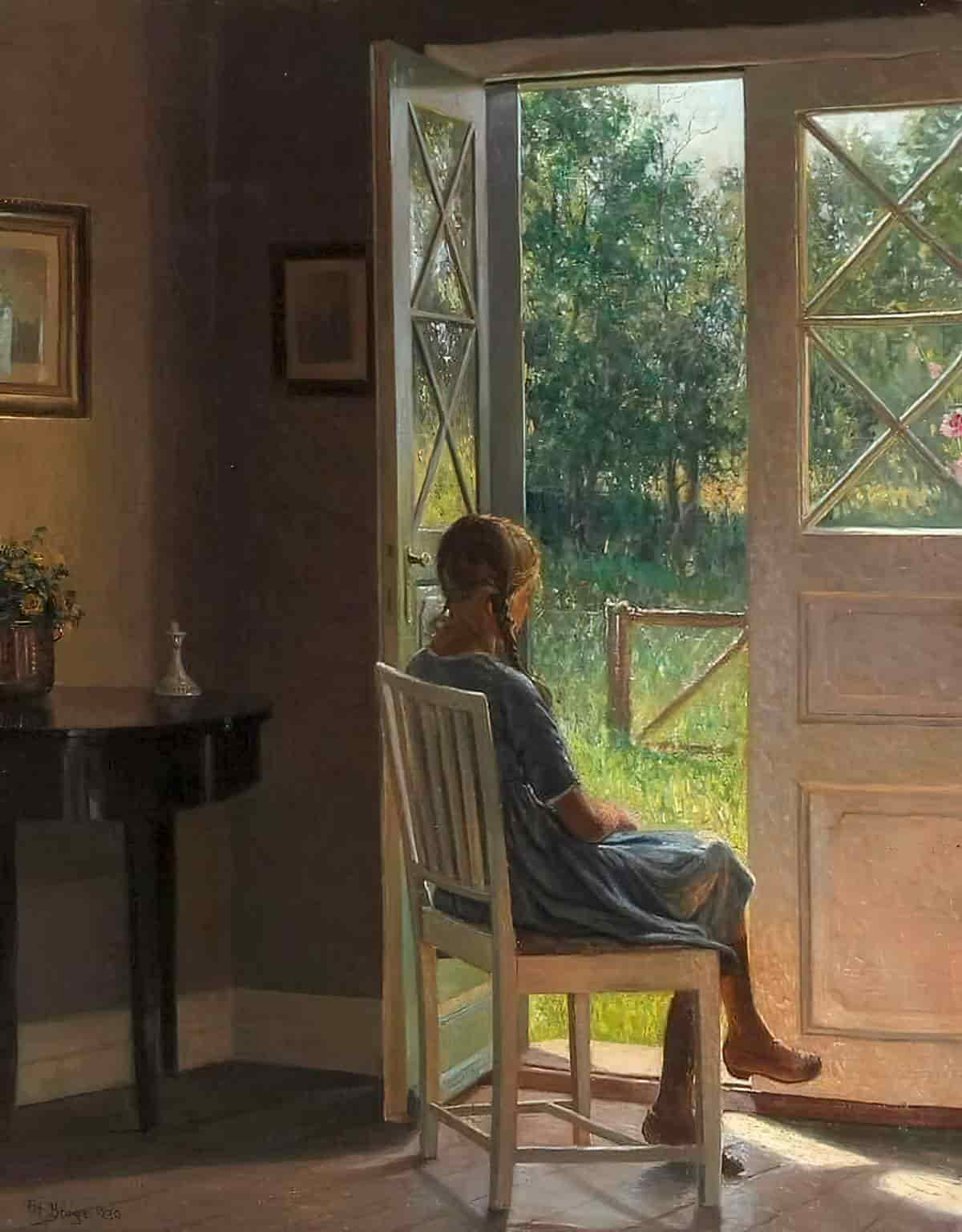

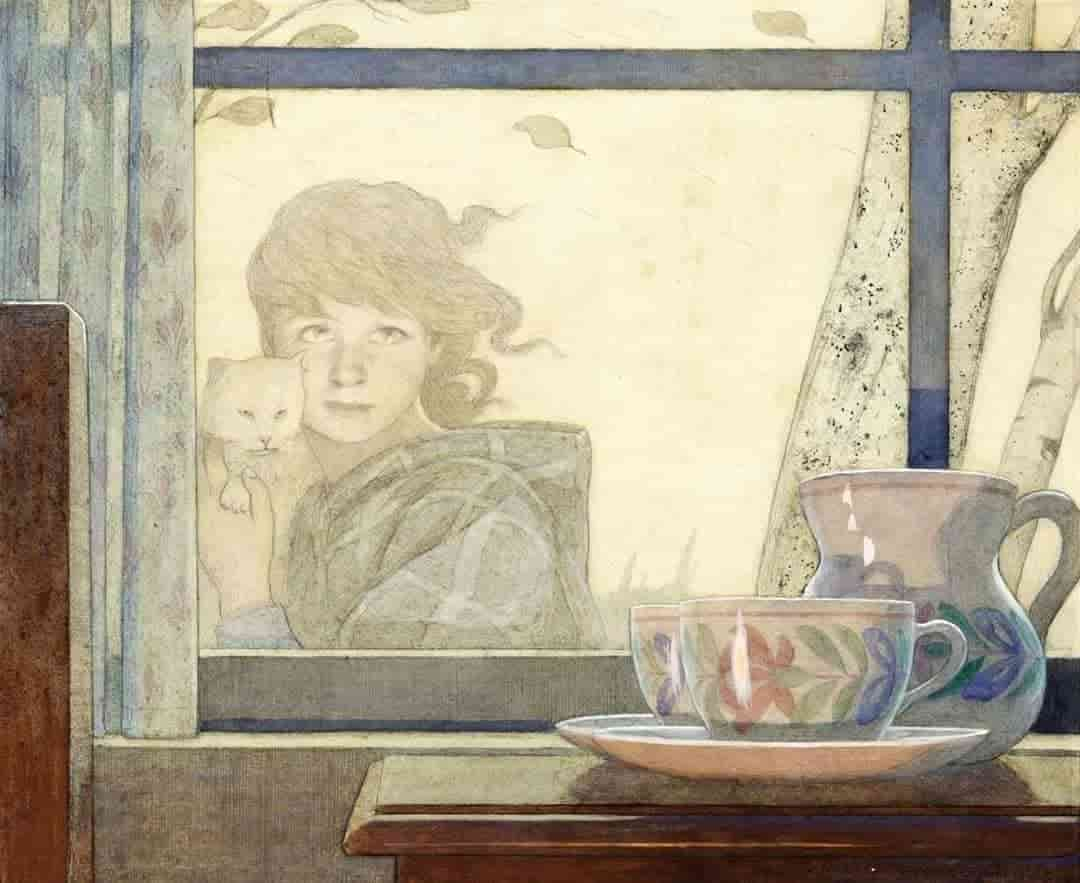

Still characters gazing out at the world from behind windows in story books. Knowing what we now know of prohibitions against gazing from windows, this is a subversive act.

A few of these gazers are old men e.g. the main character of Old Masters by Thomas Bernhard (1985), a misanthrope (human hater) who sits by the window and watches people from his ‘window stool’. (A window stool is an actual thing, sold for the purpose of window gazing in Vienna and other places.)

No intelligent man ever looks out of his window; his window is made of ground glass; its only function is to let in light, not to look out of.

Adolf Loos, Austrian and Czechoslovak architect, 1870-1933

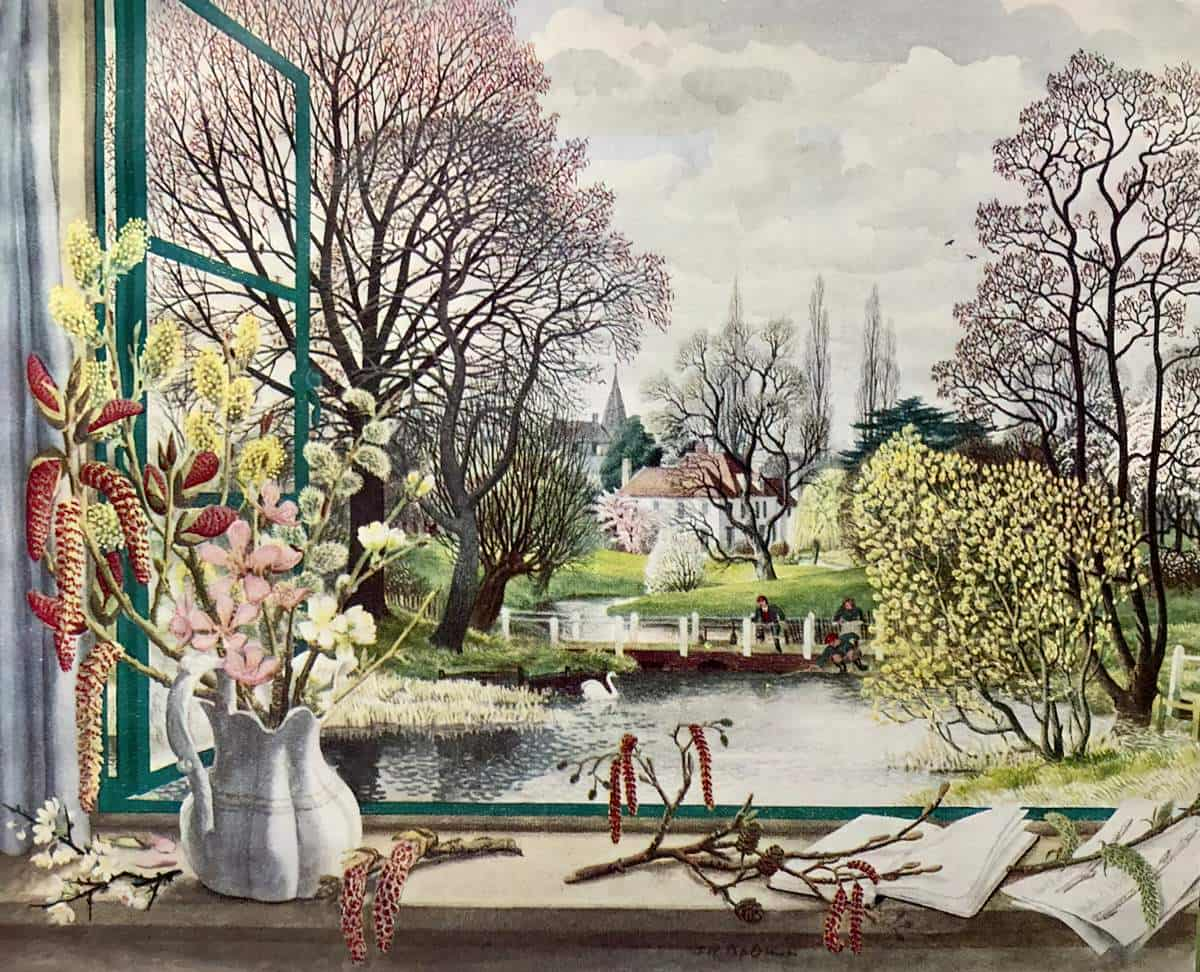

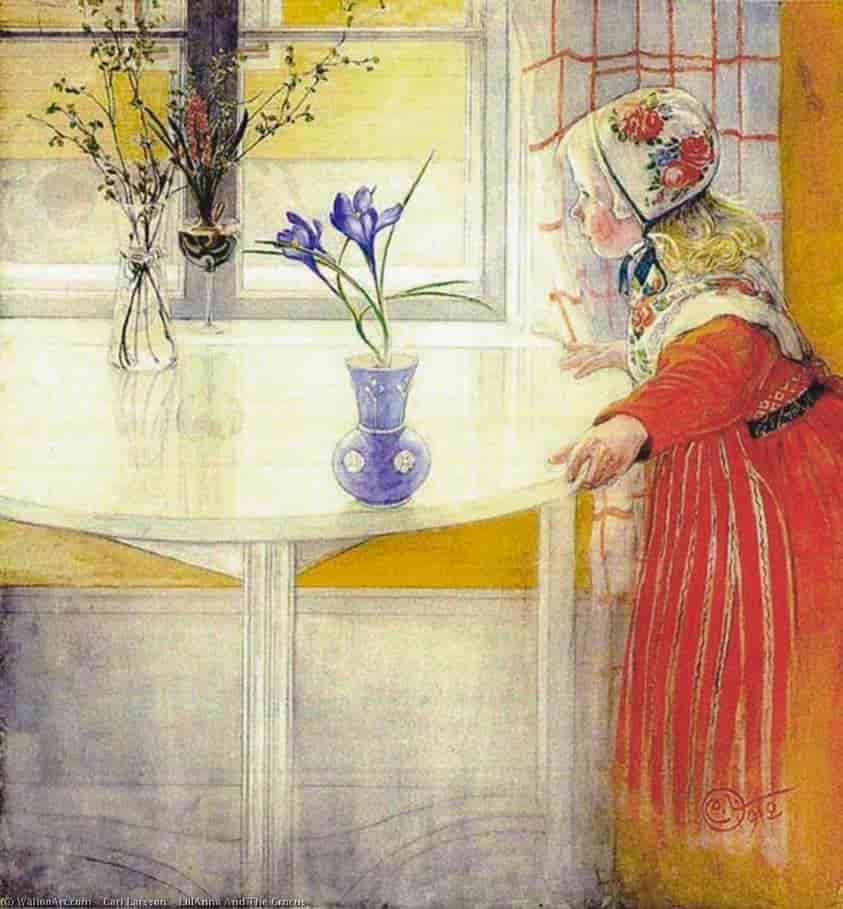

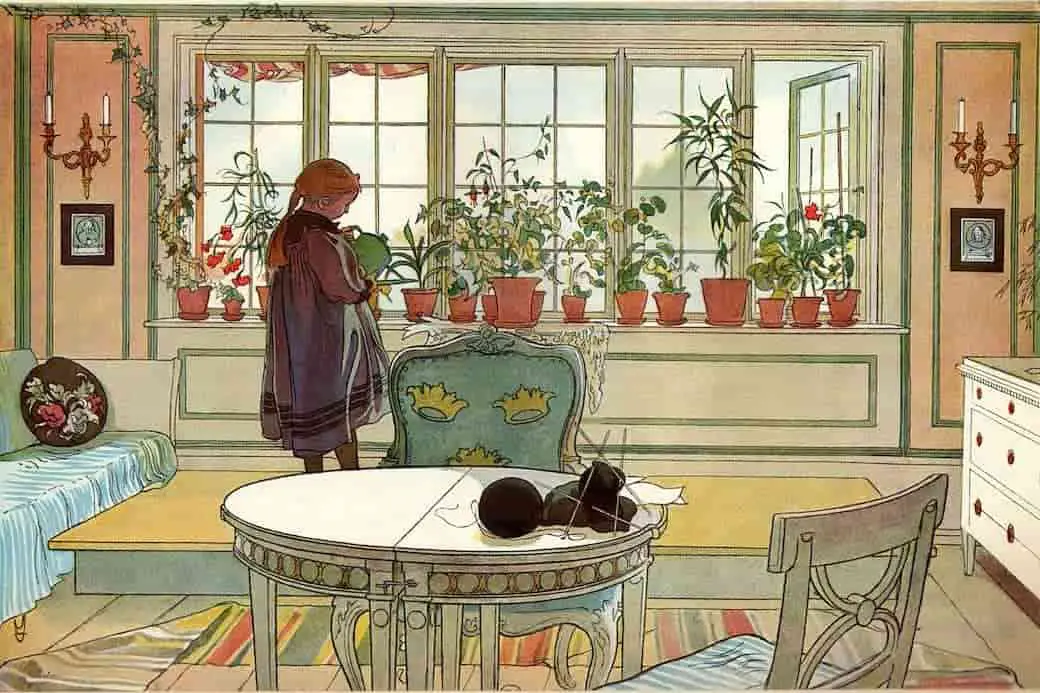

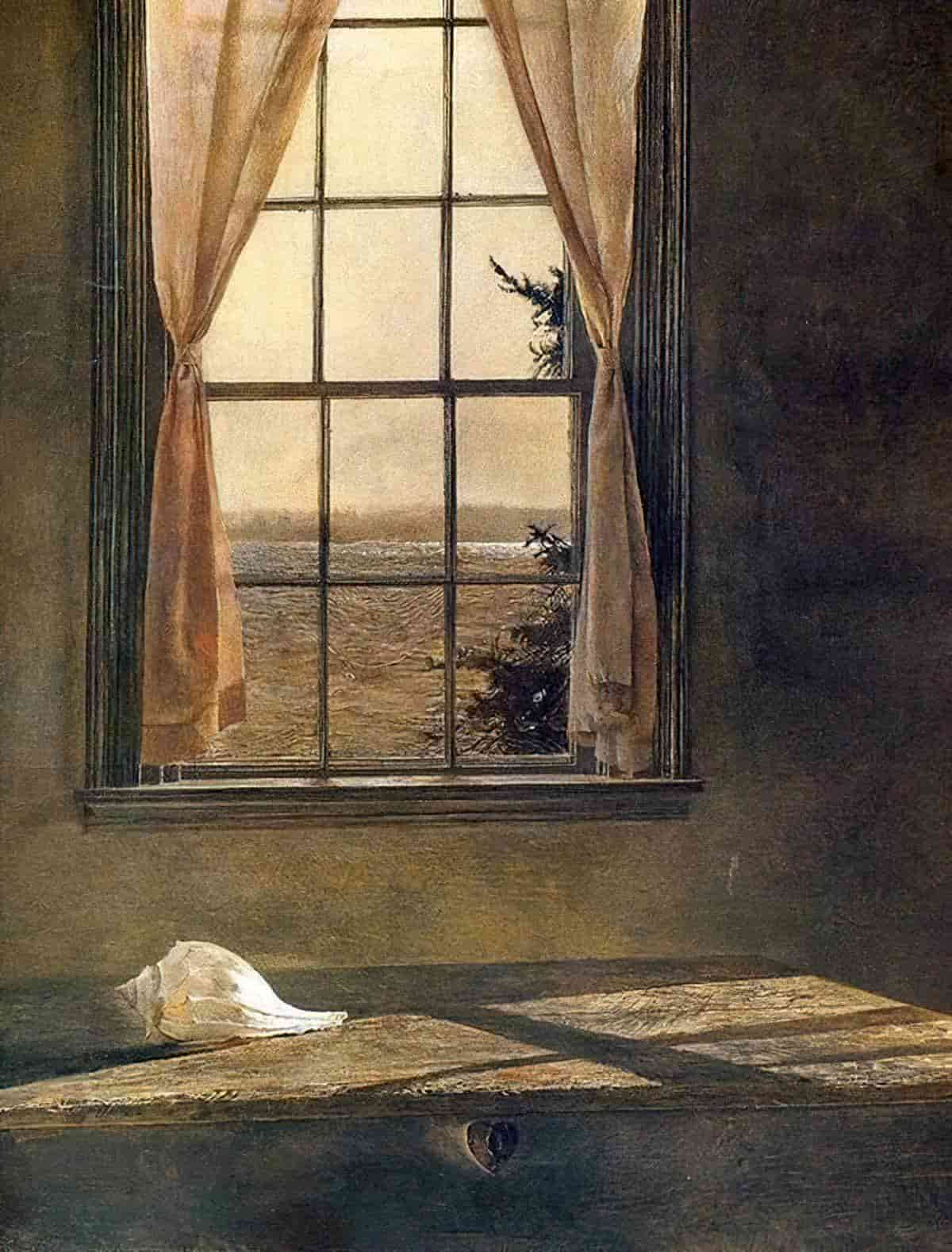

Dutch painters such as Carl Holsøe and Vilhelm Hammershøi (friends with each other) were inspired by the Dutch masters.

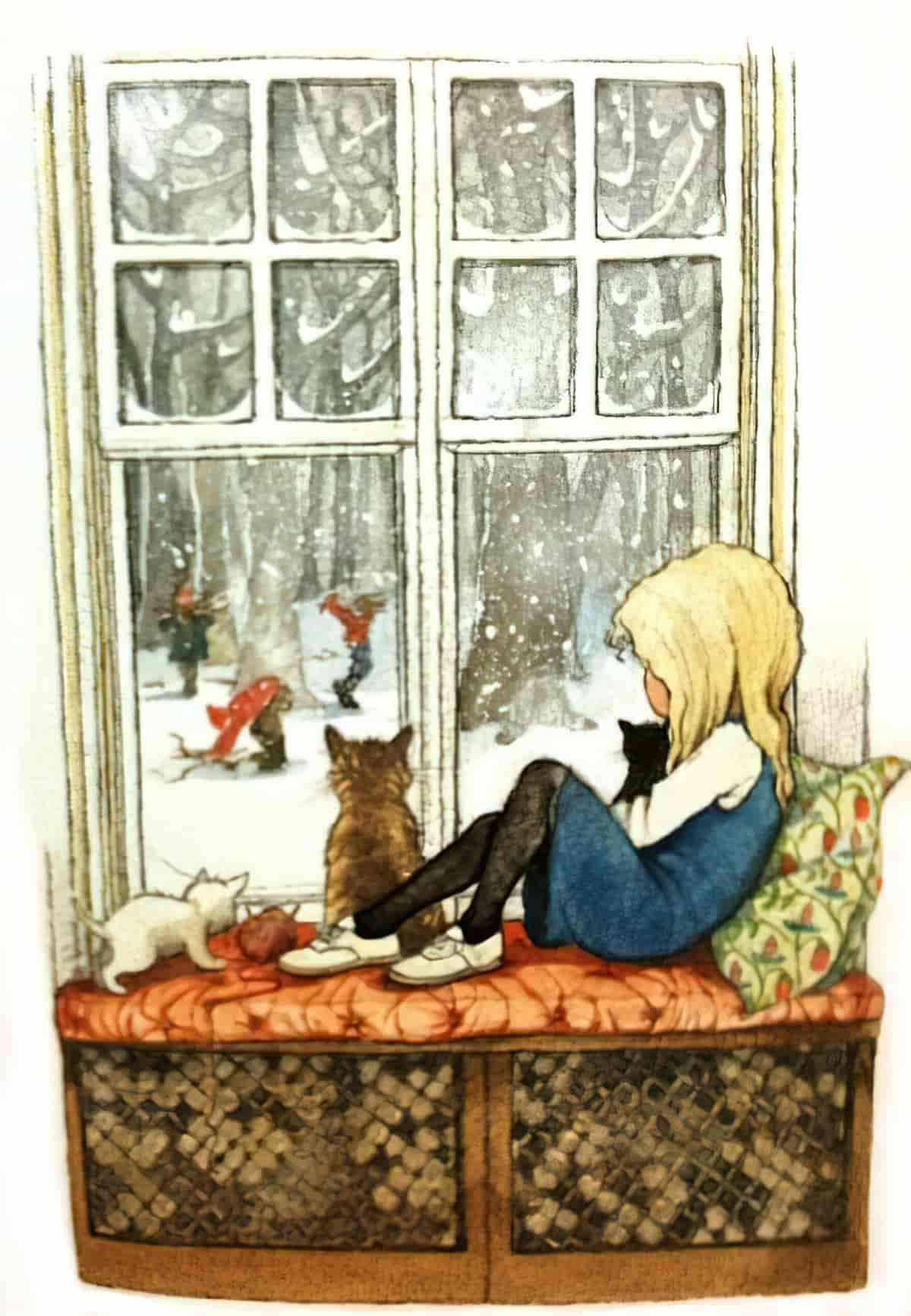

These characters are mostly girls and women, though you get a few boys and men occasionally looking through windows at the adventures happening outside. There’s a reason for the gender imbalance:

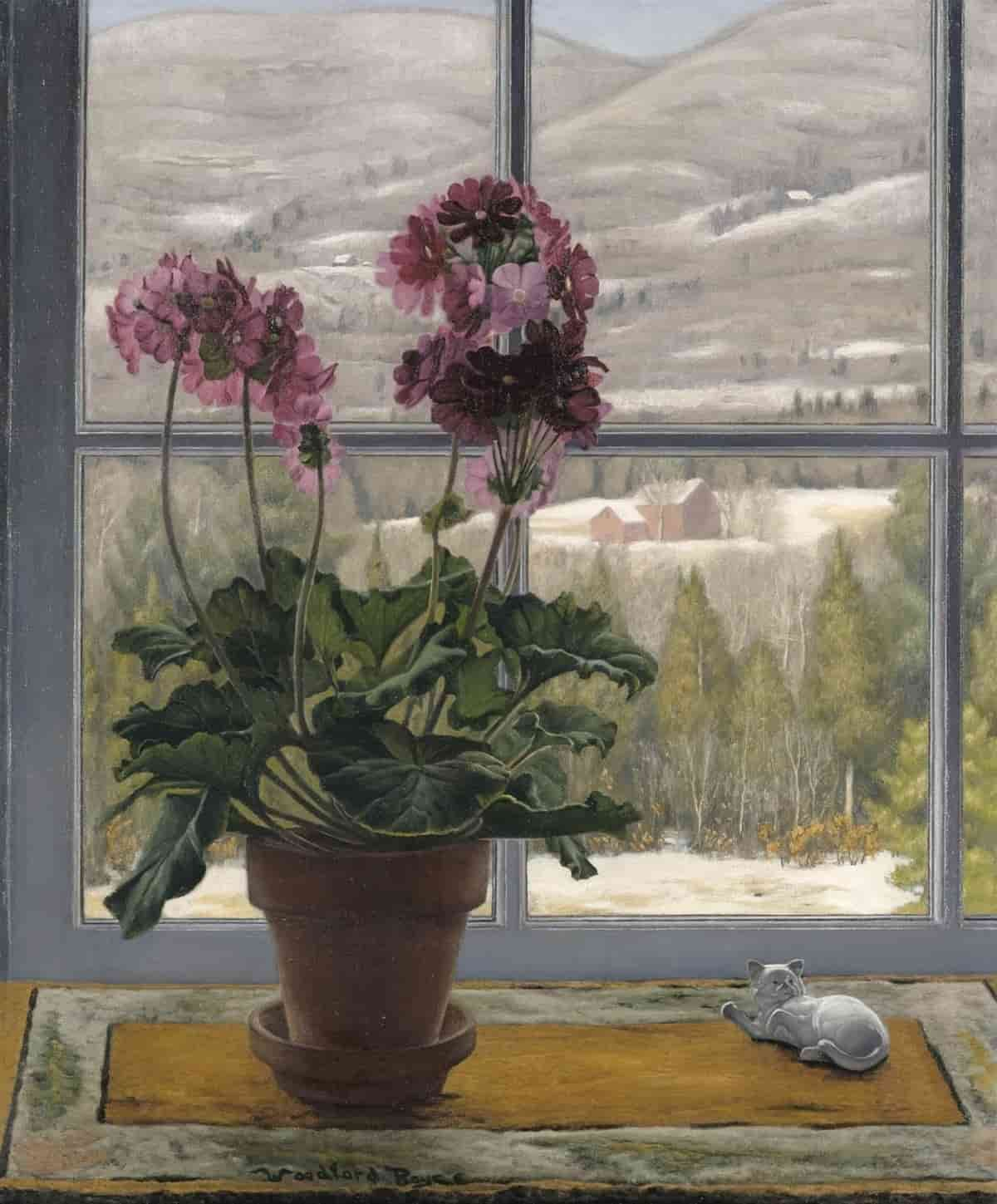

Turn-of-the-century paintings illustrating women in interiors routinely reflected [woman as decoration, part of the actual room]. In Childe Hassam’s 1918 painting, “Tanagra,” for example, the woman literally blends into and almost becomes a part of the décor. The table so closely mirrors her dress that it functions as an extension of it, as does the Japanese screen behind her. The woman is shown among flowering plants — in contrast to the cityscape glimpsed out the window, she represents naturalness and fecundity — but like her, the plants are tamed, as they are cut or confined to a clay pot. The outside light shines on the woman, but she remains in the interior, completing it with her very presence (significantly, she glances at another female body). Other paintings played on many of the same ideas. Female figures matching and even merging into surrounding draperies were seen as early as the middle of the century in America — a well-known example is James Abbott McNeill Whistler’s “The White Girl” — but the convention is particularly associated with a group of impressionists that called itself “Ten American Painters.”

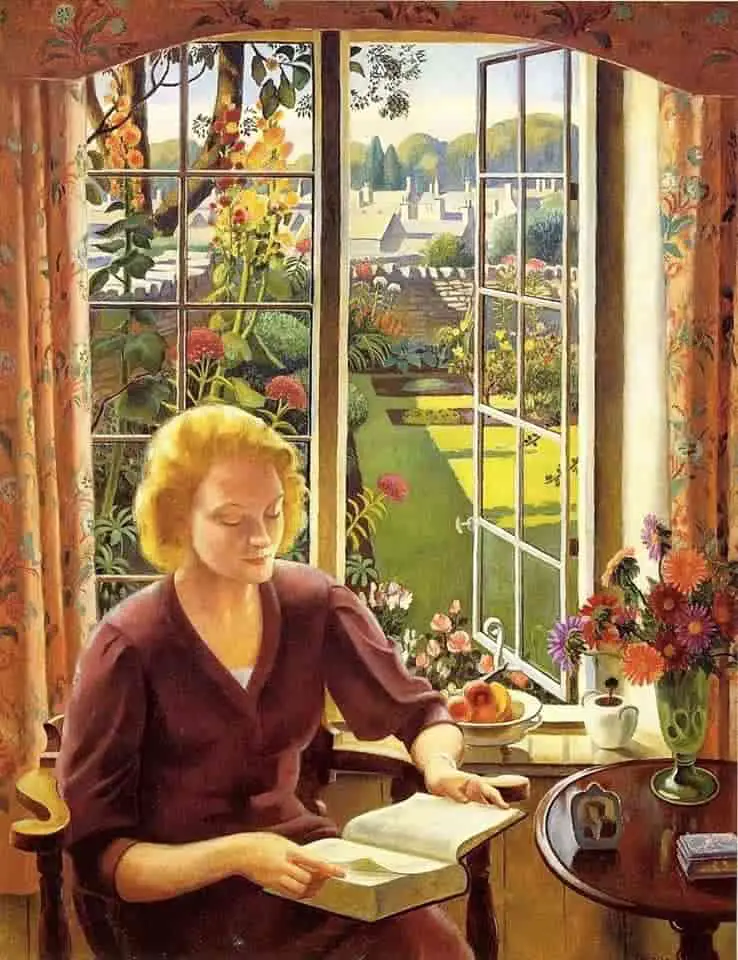

Playing on imagery from seventeenth century Dutch masters such as Vermeer who also focused on women in interiors, Hassam and his colleagues often portrayed women sitting by windows or in front of mirrors, engaged in contemplative, domestic activities such as holding flowers, sewing, or reading. The women all appeared part of their surroundings.

Woman’s Domestic Body: The Conceptual Conflation of Women and Interiors in the Industrial Age by Beverly Gordon (1989)

Confined though many of these characters are, there is also a class component in which kind of characters are viewing the world from the safety of their own domesticity, rather than out working all day, perhaps doing the housework for some other woman, who is gazing out of her window…

For two decades, Zeba was a loving wife, a patient mother, and a peaceful villager. But her quiet life is shattered when her husband, Kamal, is found brutally murdered with a hatchet in the courtyard of their home. Nearly catatonic with shock, Zeba is unable to account for her whereabouts at the time of his death. Her children swear their mother could not have committed such a heinous act. Kamal’s family is sure she did, and demands justice. Barely escaping a vengeful mob, Zeba is arrested and jailed.

Awaiting trial, she meets a group of women whose own misfortunes have led them to these bleak cells: eighteen-year-old Nafisa, imprisoned to protect her from an “honor killing”; twenty-five-year-old Latifa, a teen runaway who stays because it is safe shelter; twenty-year-old Mezghan, pregnant and unmarried, waiting for a court order to force her lover’s hand. Is Zeba a cold-blooded killer, these young women wonder, or has she been imprisoned, like them, for breaking some social rule? For these women, the prison is both a haven and a punishment; removed from the harsh and unforgiving world outside, they form a lively and indelible sisterhood.

CHARACTERS LOOKING OUT WINDOWS

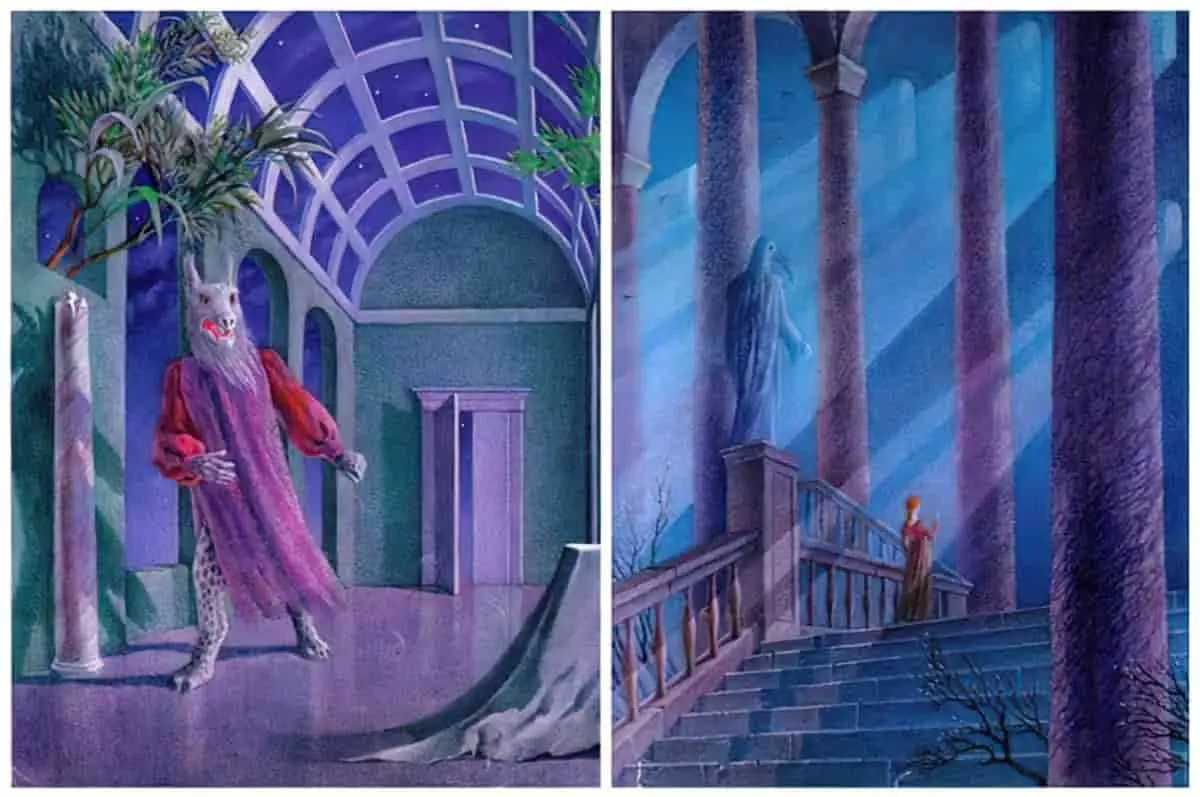

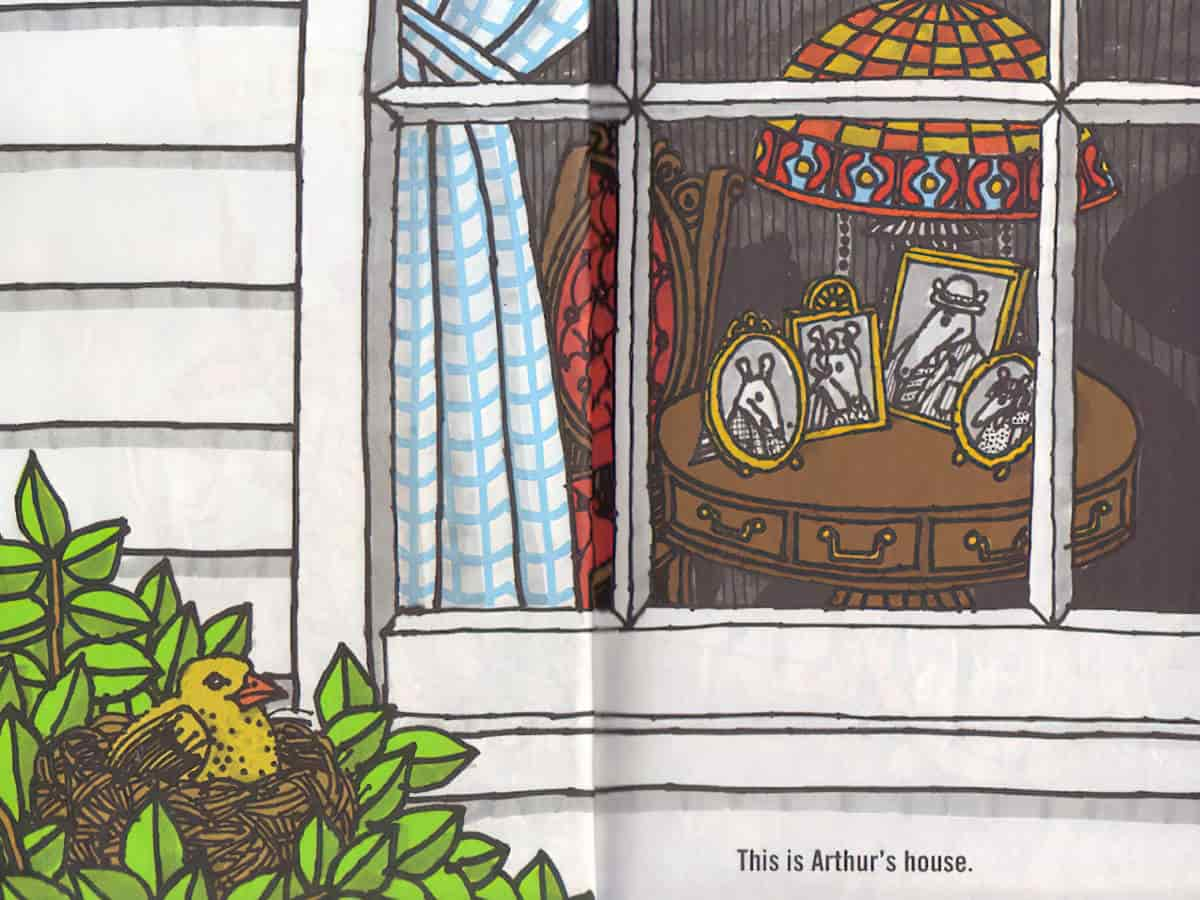

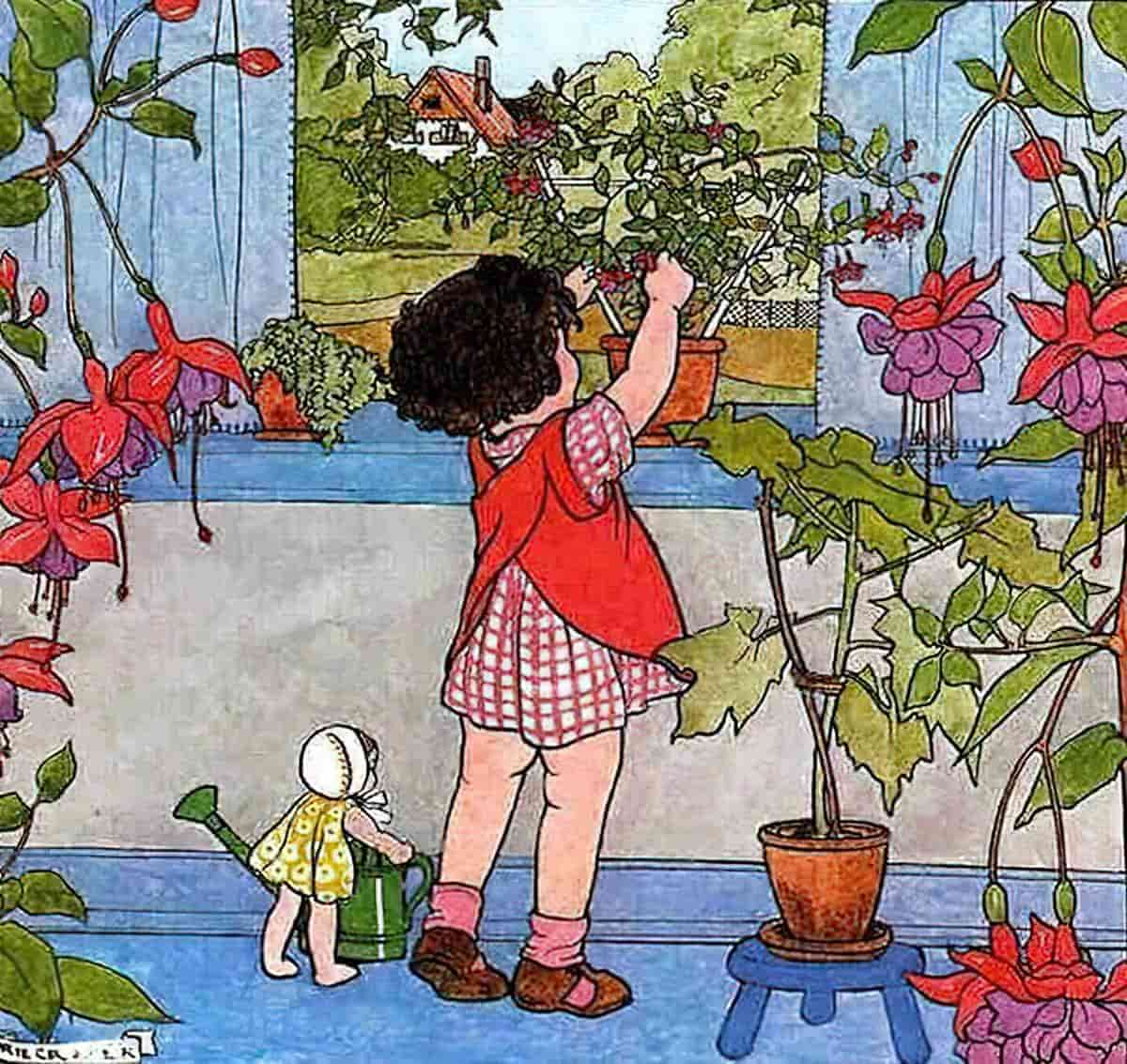

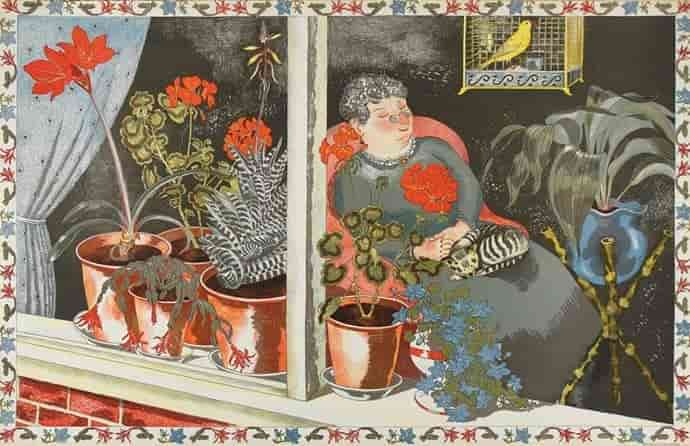

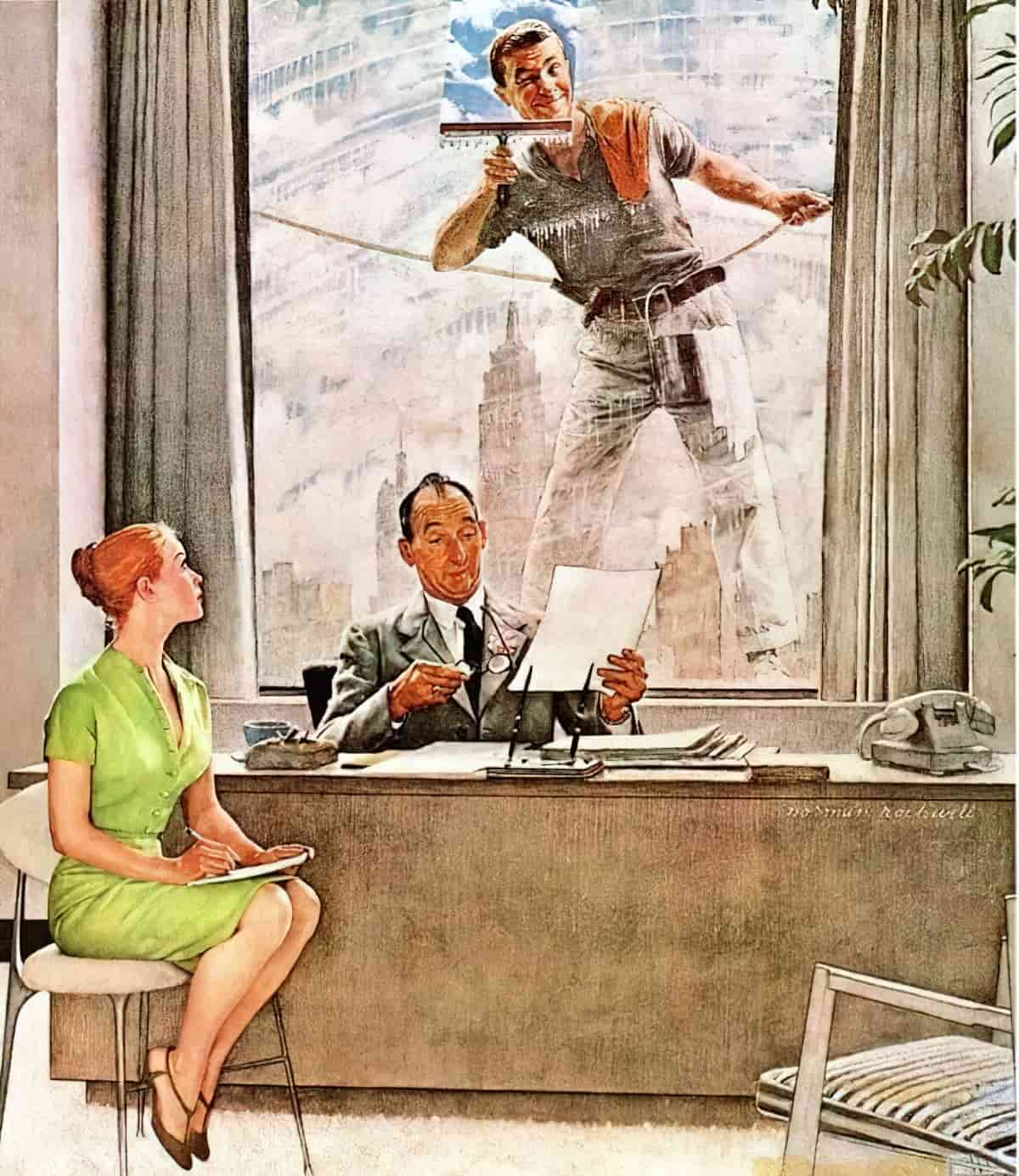

The illustration below offers a refreshing spin on the passive woman sitting next to a window tending to her flower pots, watching the world go by.

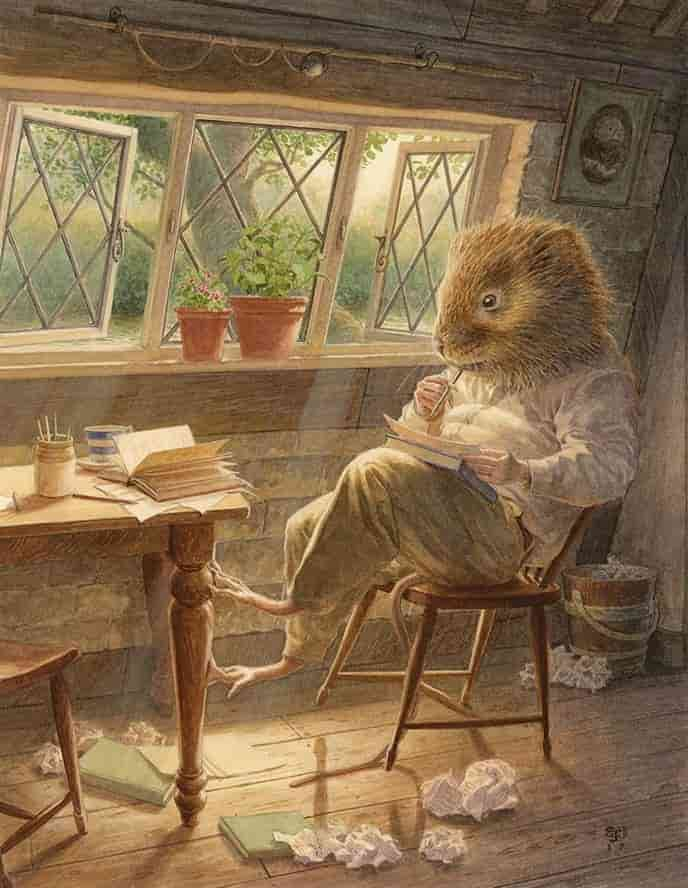

You’ll be hard-pressed to find a picture of a grown man sitting in front of a window with potted flowers on it, unless that masculo-coded character is an animal. But Chris Dunn gives us one, thanks to the boundary-breaking effect of animals as characters in children’s stories.

This often indicates the beginning of a character arc, possibly a journey away from the house. Through the window, the unknown becomes more fascinating and attractive than the known. When characters gaze from a window, we become as interested as they are.

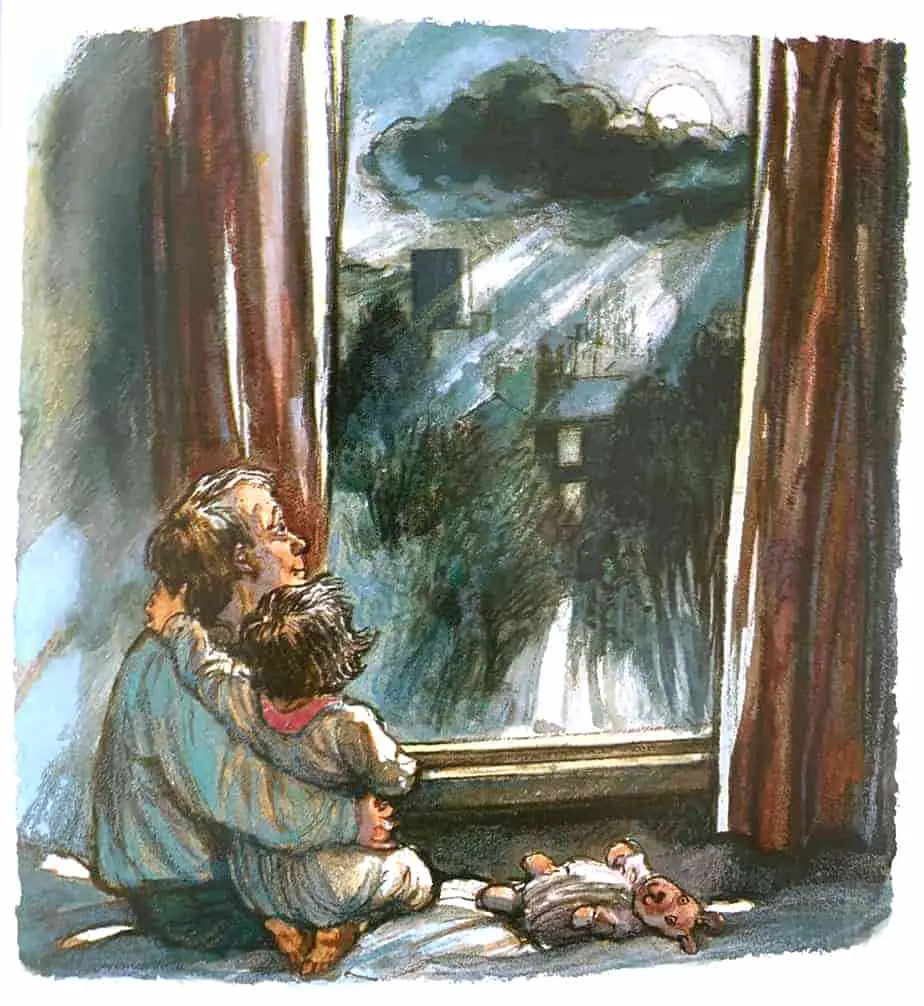

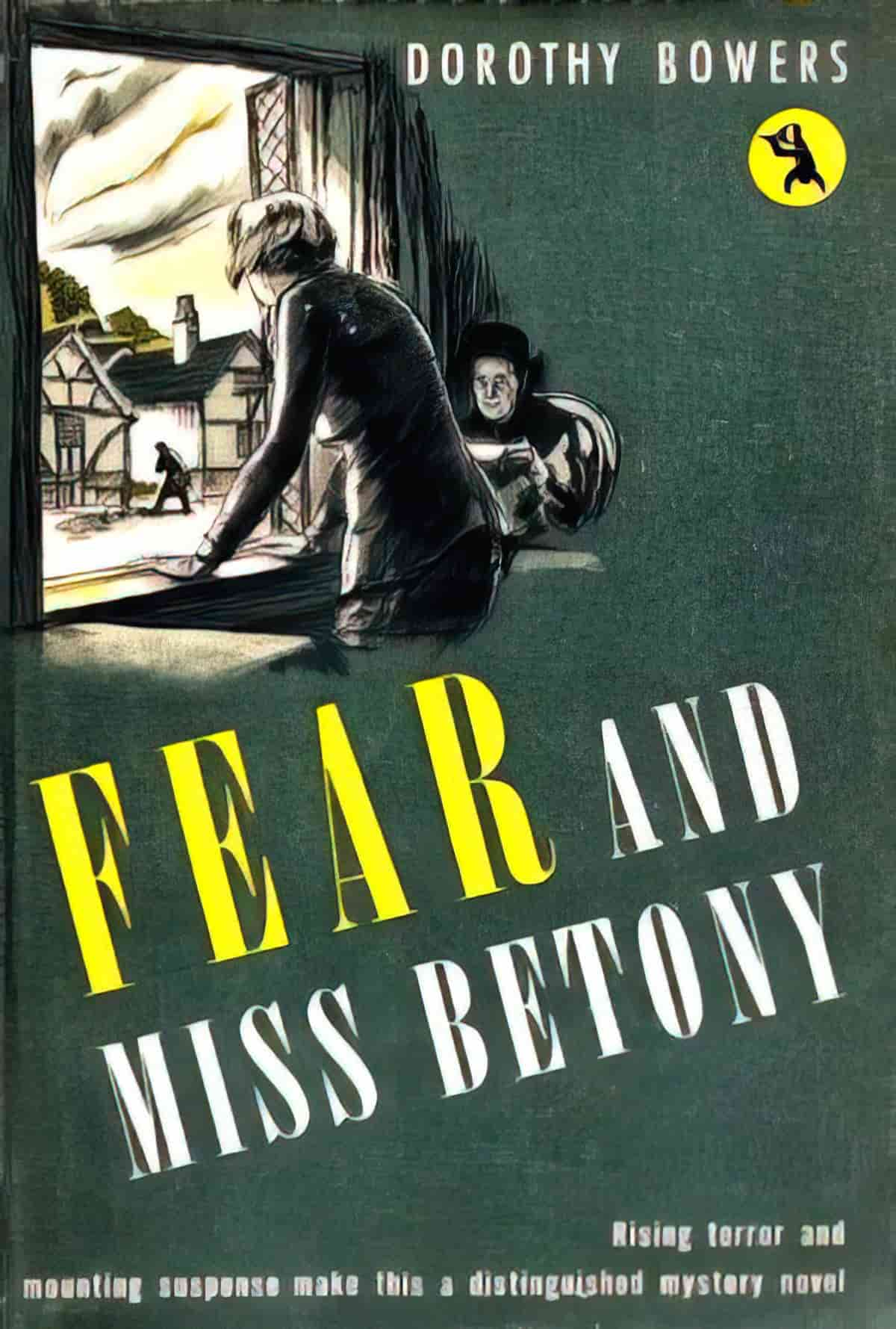

At other times the characters are hiding from the outside world, because the outside world is dangerous.

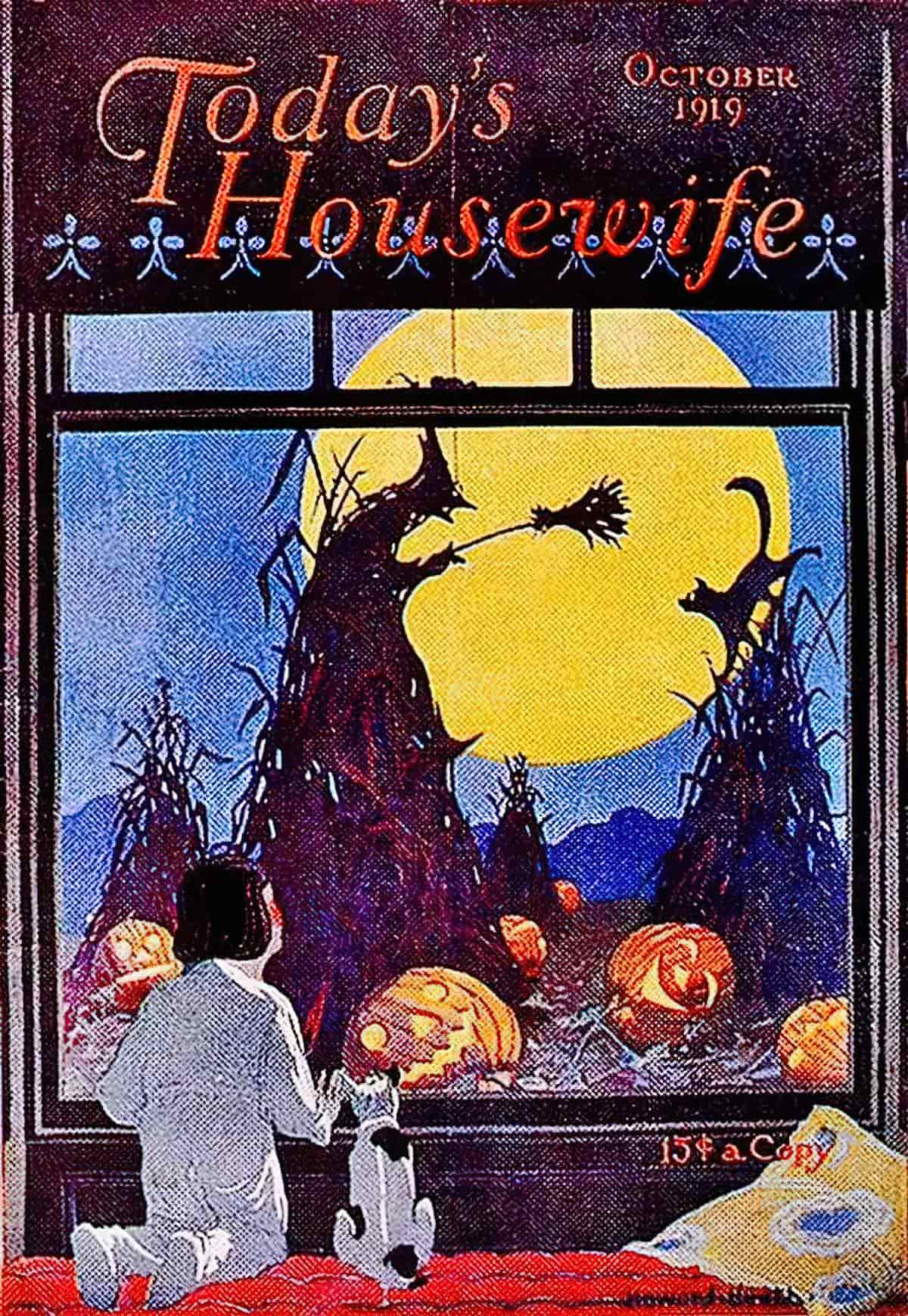

Many children’s stories open with a character looking out the window. In these stories the main character’s Desire Line will involve the pursuit of freedom.

Picture book version: The carnivalesque desire to have fun for a while without adult supervision/interference.

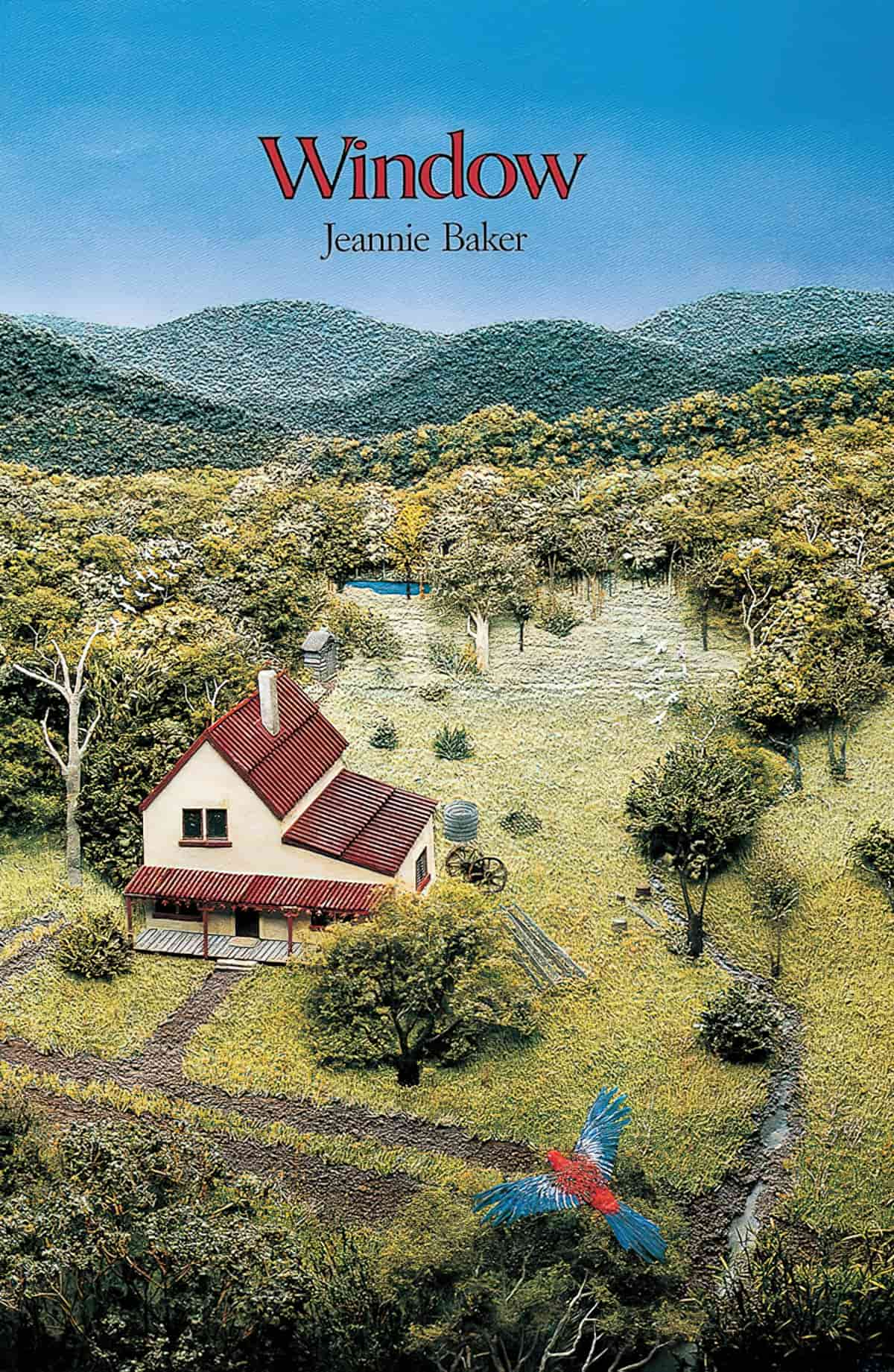

The concept is taken most literally in the picture book Window by Jeannie Baker.

Window is an Australian wordless picture book published 1991.

A mother and baby look through a window at a view of wilderness and sky as far as they can see. As Sam, the baby, grows, the view changes. At first, in a cleared patch of forest, a single house appears, A few years pass and there is a village in the distance. The village develops into a city.

Sam, now a young man, gets married, has a child of his own and moves to the country. Now father and baby look through a window in their new home. The view again is of a wilderness, but in a cleared patch of forest across a dirt road a prophetic sign reads, ‘House Blocks for Sale’.

Middle Grade version: To solve problems on one’s own, outside the safety of the house

Young Adult version: To separate from parents and find true self.

Margaret Simon, almost twelve, likes long hair, tuna fish, the smell of rain, and things that are pink. She’s just moved from New York City to Farbook, New Jersey, and is anxious to fit in with her new friends—Nancy, Gretchen, and Janie. When they form a secret club to talk about private subjects like boys, bras, and getting their first periods, Margaret is happy to belong.

But none of them can believe Margaret doesn’t have religion, and that she isn’t going to the Y or the Jewish Community Center. What they don’t know is Margaret has her own very special relationship with God. She can talk to God about everything—family, friends, even Moose Freed, her secret crush.

Margaret is funny and real, and her thoughts and feelings are oh-so-relatable—you’ll feel like she’s talking right to you, sharing her secrets with a friend.

The following is a passage from Carrie, a young adult novel by Stephen King, describing Sue as she is about to join the fray, where Carrie wreaks havoc.

The town hall whistle went off every day at twelve noon and that was all, except to call the volunteer fire department during grass-fire season in August and September. It was strictly for major disasters, and its sound was dreamy and terrifying in the empty house.

She went to the window, but slowly. The shrieking of the whistle rose and fell, rose and fell. Somewhere, horns were beginning to blat, as if for a wedding. She could see her reflection in the darkened glass, lips parted, eyes wide, and then the condensation of her breath obscured it.

The outside world of 101 Dalmatians (film adaptation is from 1961) is also dangerous for dogs whose hides are wanted for coats.

The window allows the framing of Cruella as she drives past in her Rolls, dangerously close to capturing them.

The audience also sees her two hapless baddies framed by the broken window, highlighting all of their brokenness. Note that this is the climax, in which the Dalmatians successfully escape death. The view of the opponents through the broken window foreshadows this happy outcome.

The brokenness of the glass not only frames the character as psychologically broken but also removes what little distance there might be between heroes and opponents. The baddies are dangerously close to finding us. (The only need to move their eyeballs…)

AUDIENCE GAZES FROM WINDOW

When the audience is gazing through the window we emotionally identify with the character on the same side as we are. Sometimes we’ll be looking over the sympathetic character’s shoulder and other times we’ll be looking out as if we are them. This can happen after the characters have been introduced.

The cover of Pax does not feature a window per se, but when an animal looks through a frame of foliage across a landscape, this is the animal equivalent of a child gazing out a window.

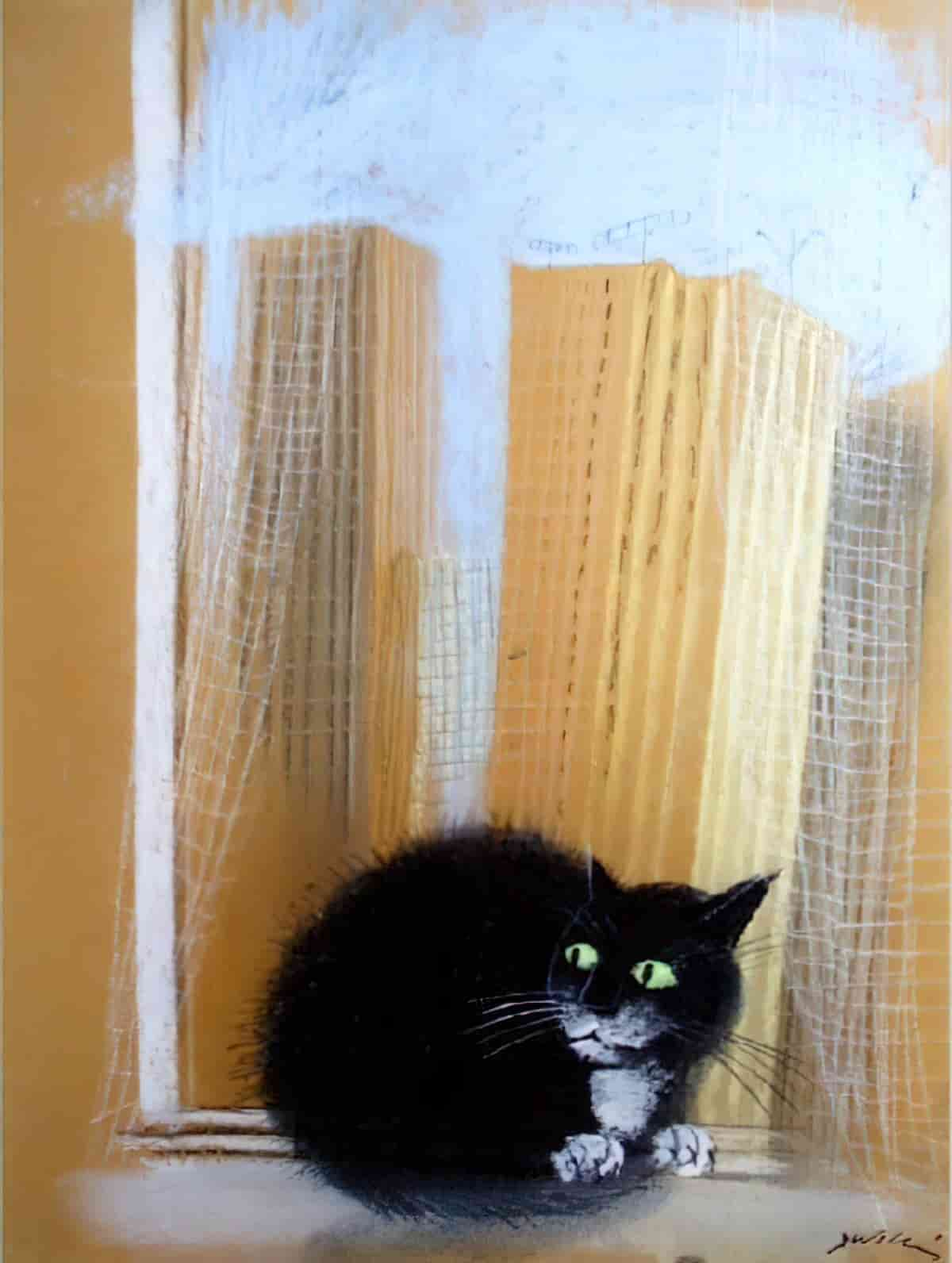

Cats looking out windows is another popular motif.

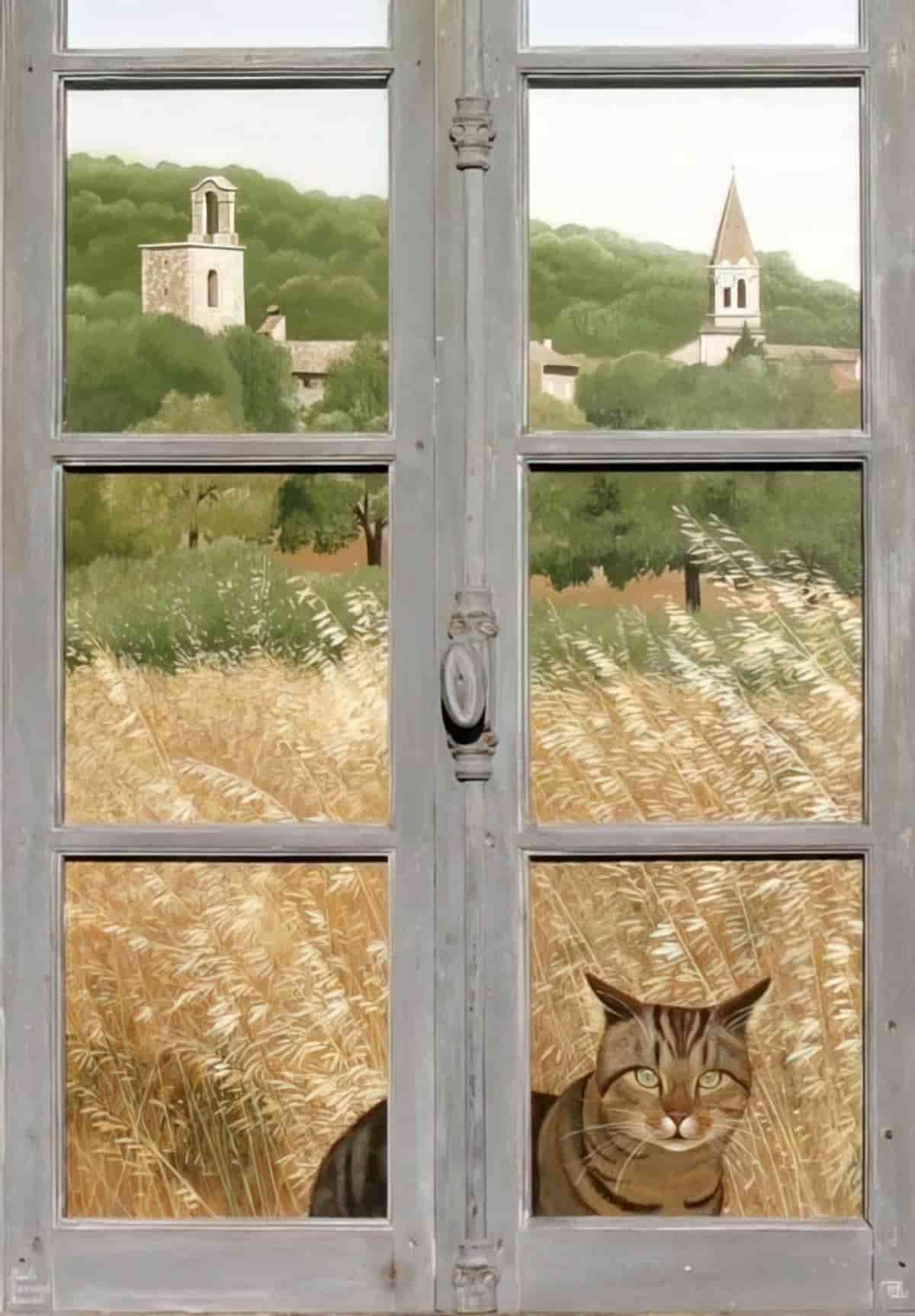

And of course you can’t have cats wishing to head outside without cats also wishing to come back in. So here are a few catslooking inside a window from the outside.

WINDOW AS ESCAPE HATCHET

There are three escapes via windows in the Bible:

- The flight of Joshua’s spies from the town of Jericho with the assistance of sex worker Rahab (Jos 2, 15)

- The flight of David from Saul’s persecution through a window of his palace with the help of his wife Michal (1 Kings 19, 12)

- The flight of Saint Paul from Damascus, who was lowered into a basket through a window (2 Cor 11, 33) and over the town walls by his disciples (Ibid. and Acts 9, 25)

The difficulty with reading the Bible and other religious texts: It’s difficult if not impossible to draw a distinction between narrative and details meant to be read as a symbol. So, were there actual escapes through windows, or are these window escapes symbolic of escape as a concept, and possibly of rebirth and connection with God?

A symbolic window in a Biblical window story is always, on the first level, a narrative window upon which a second, symbolic, level is overlaid; while, on the other hand, the mediaeval mind saw a deeper meaning in every story, so that every window episode contained for this mind eo ipso [thereby] a lesson; it is merely a question whether or not the lesson is tied to the window.

The Escape Through The Window: A Figura For Christ’s Victory Over Death by Carla Gottlieb

Regarding the story of Joshua and Rahab, Gottlieb quotes a first century Frankish Benedictine monk:

The comment on the symbolic meaning of the window in the meeting of Rahab with Joshua’s messengers is formulated as follows by Hrabanus Maurus (776 or 764-856): Insofar as this sign hangs in the window, I believe this indicates that the window is the one which illumines the house and through which our appearance is illumined, but we take in merely as much light as suffices for our eyes and needs. Likewise, the Incarnation of the Savior does not present to us the true and complete appearance of divinity but makes us perceive the light of divinity by means of His Incarnation, as though through a window.

Therefore, it seems to me, the sign of salvation was given through the window, by which sign all those who were found in the house of the one who once was a harlot, will achieve salvation through water and the Holy Spirit, though the blood of our Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ. (Comm. to Jo 2, Bk. 1, chapter 3).

The Escape Through The Window: A Figura For Christ’s Victory Over Death by Carla Gottlieb

Meaning:

- The window is the source of light for humans.

- But it is impossible to have the full brightness of the sun illuminate an interior via window. In the same way, it is impossible for mortal eyes to perceive the full glory of God in the Incarnate.

- For Rahab, the window is a symbol of the Incarnation. (This is also the case for the window of Solomon’s bower in the Canticle.)

- The miraculous deliverance of Joshua’s scouts prefigures the Incarnation and Redemption. (Likewise, David’s miraculous deliverance prefigures the Descent into Limbo and the Resurrection in Christian thought.) In both cases, the window is a token for Christ’s victory over death.

However, in the story of Joshua there’s a scarlet rope (or cord), commonly considered the cord which brought salvation to Joshua’s messengers. Being a more resonant detail due to its colour and binding power, much attention has been given to the cord, and almost none to any symbolism of the window. Gottlieb considers the cord a ‘magic image’ rather than a ‘dramatic object’.

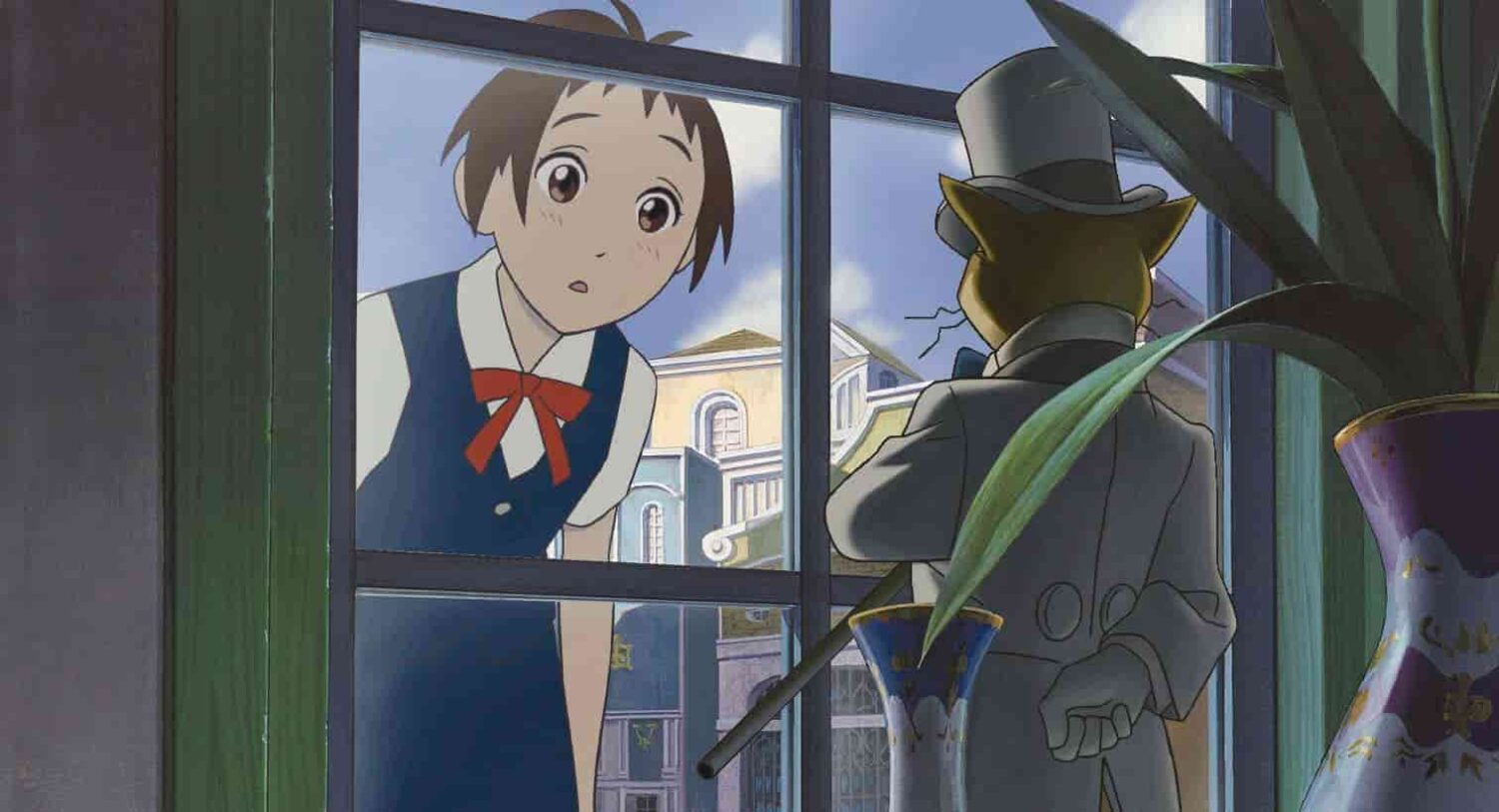

WINDOW AS PORTAL

In The Cat Returns, Haru sees the Baron before she meets him. She’s about to be transported into a miniature world. By allowing this slower meeting, the creators let the audience dwell for longer on the transition. In portal fantasies, transitions are important.

The poets Naturalist, Symbolist and Surrealist French poets Baudelaire, Mallarme and Apollinaire all wrote poems called Fenêtres (meaning windows). All three poets associated the window with some kind of breakaway, an exit to a different world.

- Translation of Charles Baudelaire’s “The Windows”

- Windows (Version A), by Stephane Mallarme

- The Windows by Apollinaire

WINDOWS AS VULNERABILITY

An important feature of windows is that, even if they don’t open, they expose occupants of a house to vulnerability.

People have been worried about peepers for as long as windows have been built for views. In medieval and early modern Europe, Italian preachers scolded young women who, “when she hears a horse, does straightaway run to the window, who would see all and know everything”. (There is a long, long tradition of women and girls being too nosy for their own good. Depressingly, being too nosy for her own good according to patriarchy doesn’t even necessitate her leaving the confines of her own home.)

Much later, when homes switched from gas lamps and other low levels of lighting, commentators expressed concerns that women and girls would be subject to peeping Toms if homes were well-lit after dark.

In many contemporary movies, especially, the house made of big windows is almost always a cold, unwelcoming place — never a warm, cosy ‘home’. Thrillers and horrors especially utilise the big, glass house as a setting. Intruders can see you, and plot bad things based around your schedule.

Humans have known how to make glass for a very long time. It took much longer to work out how to make sheet glass suitable for windows. Before windows, Europeans lived in houses with a different kind of vulnerability: Doors could be locked, but chimneys were always open.

We see evidence of this vulnerability in fairy tales such as The Three Little Pigs. The pigs turn that vulnerable opening to their advantage by coaxing the wolf down the chimney, where he will fall to his death in their cooking pot.

Coaxing a Minotaur Opponent down your chimney in order to cook them in your pot is a trope with a long history. The early to mid 14th century marked the beginning of the witch craze across Europe. Many people really did believe that witches lived in their village. This accounted for the crop failures and starvation. (The culprit was in fact climate change in the form of a little ice age.) To regain a sense of control, people blamed witches. You can’t do anything about climate, but you feel you can do something about an opponent in human form. For example, you could surround your house in witch marks, perform counter magic and force witches down your chimney, where she will fall into your cooking pot and be scalded to death. In order for this to work, people had to imagine a witch small enough to fall down a chimney, so it was necessary to believe that witches could transmogrify. This made them even more scary, because now you believed a witch could get in through any tiny crack.

The idea that entering homes via the chimney is possible has been recast as a pleasant story in the narrative around Santa Clause. This is the version we tell to children.

When an illustration (or scene) is framed by a window, the audience experiences something akin to voyeurism. Should we really be seeing this?

The composition of Snow White’s pregnant mother below is an especially interesting depiction of vulnerability. Using the ‘split screen’ technique, illustrator Angela Barrett chops the head off the vulnerable mother-to-be. Notice also, in close up, the slipper stuck in the wall. The viewer gets a simultaneous view of the safe, cosy inside of the castle and the snowy, bleak outside.

Once upon a time in midwinter, when the snowflakes were falling like feathers from heaven, a queen sat sewing at her window, which had a frame of black ebony wood. As she sewed she looked up at the snow and pricked her finger with her needle. Three drops of blood fell into the snow. The red on the white looked so beautiful that she thought to herself, ‘If only I had a child as white as snow, as red as blood, and as black as the wood in this frame.’

Brothers Grimm

WINDOWS AS EYES OF THE PERSONIFIED HOUSE

The metaphors [conflating women and houses] were supported by the many ways in which women in particular related to their houses in physical, bodily ways. Housewives attended to and even created cycles of house maintenance, just as they attended to daily, monthly and seasonal cycles of body and clothing maintenance. Curtains were opened in the morning, much as the body was groomed and prepared for the day’s activities. The same curtains were drawn in the evenings, when the lamps were lit and evening dress was put on.

Beverly Gordon, Woman’s Domestic Body: The Conceptual Conflation of Women and Interiors in the Industrial Age, 1996

Aside from eyes, houses (and windows) are compared to human inhabitants in many other ways. Beverly Gordon goes into the various (mostly dead) metaphors we use in English when talking about houses. (Dead metaphor: Started out as metaphor but has now become routine idiomatic use.) ‘Dressing’ is one example:

A “fully dressed” window in the Victorian era could, like a woman’s fully dressed body, involve multiple layers, including underdraperies and overdraperies, tassels and “jewelry” (brass rings and similar hardware). The “French shawl” arrangement featured a variety of textures and decorative treatments, from fringe on the outer layer to sheer fabric almost like an undergarment on the inside.

Beverly Gordon, Woman’s Domestic Body: The Conceptual Conflation of Women and Interiors in the Industrial Age, 1996

WINDOWS TO LET OUT THE DEAD

Another medieval belief was that if someone died in bed, you needed to open the window in order to let their soul escape. If you could no longer look after your elderly relative, you might leave the window open hoping they would die. If this worked, it was probably because opening a window also let in the cold. It was probably quite effective in winter.

There’s a long history of window motifs as symbol of the human soul in its relation to the external world. This is especially evident in the poetry of Baudelaire. In Fenêtre (1863) the prose poem begins by reminding the audience that the poet’s window is closed and obscure. This is supposedly ideal for stimulating melancholy and suffering.

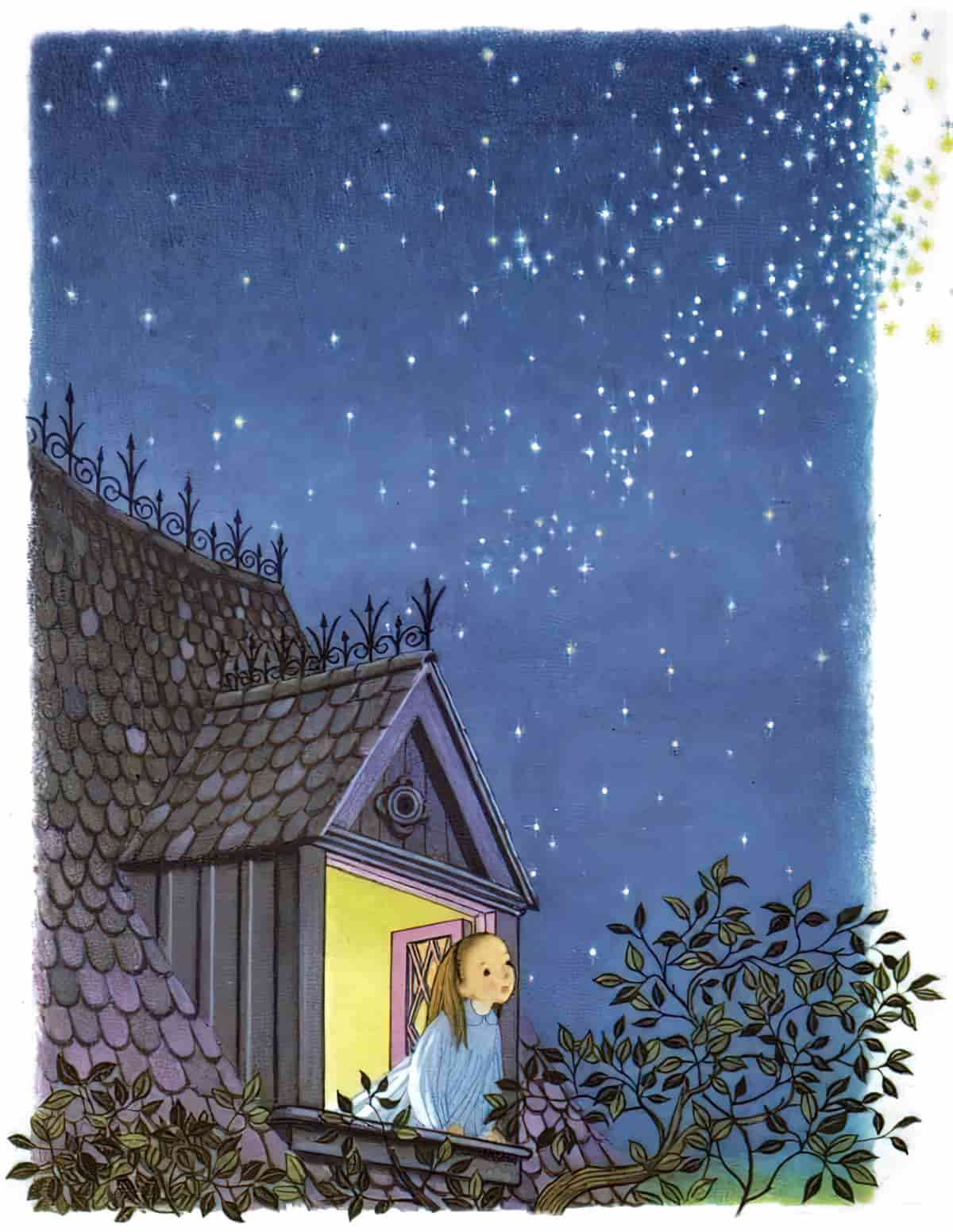

YELLOW WINDOWS AS SAFETY

A chase scene from 101 Dalmatians starts to feel safer when the puppies approach a window with warm yellows emanating from it. We are reassured that safety is imminent.

In the scene below, our 101 Dalmatians make it home to safety. Their howling wakes up the entire town. We see the lights flick on one by one. Plotwise, these dogs are waking neighbours up, but symbolically, the yellow squares turning on reassure the audience that ‘this is civilisation and our dogs are safe now’.

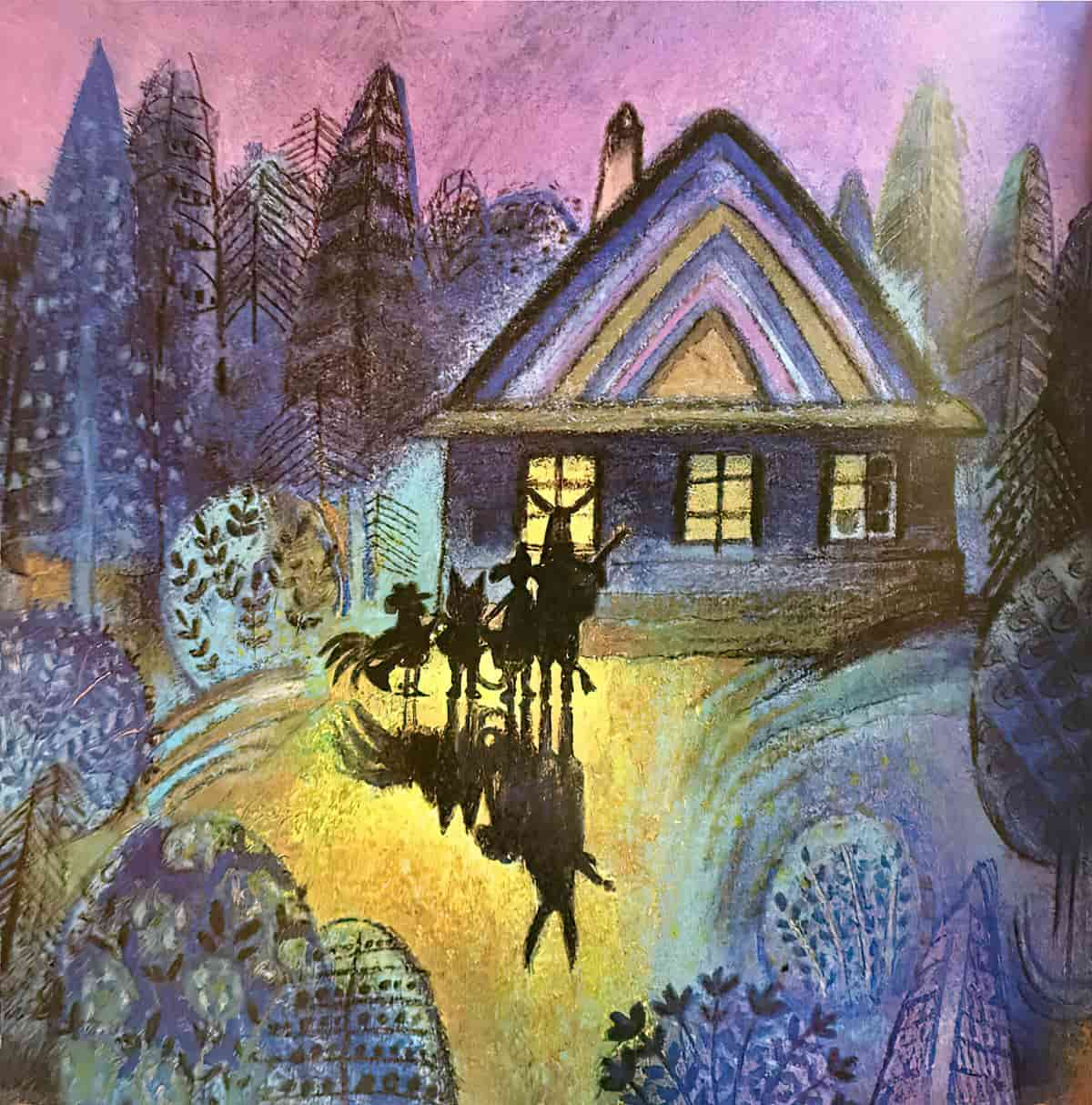

In most illustrated versions of “The Town Musicians of Bremen” there is a picture of the yellow window of the robbers as seen from a distance. My Richard Scarry edition was one of the resonant illustrations from my childhood.

But adults as well as children appreciate a yellow window in the distance. Alice Munro writes beautifully about cosy, yellow windows in “Fiction“:

There was the one special thing Joyce loved to see as she was driving home and turning in to their own property. At this time many people, even some of the thatched-roof people, were putting in what were called patio doors—even if like Jon and Joyce they had no patio. These were usually left uncurtained, and the two oblongs of light seemed to be a sign or pledge of comfort, of safety and replenishment. Why this should be so, more than with ordinary windows, Joyce could not say. Perhaps it was that most were meant not just to look out on but to open directly into the forest darkness, and that they displayed the haven of home so artlessly. Full-length people cooking or watching television — scenes which beguiled her, even if she knew things would not be so special inside.

WINDOWS AS TOOLS OF SURVEILLANCE

Windows don’t always exist for the benefit of people living behind them. In Michel Foucault’s panopticon, prisoners are afforded windows not so they can enjoy a view, but so that they may be constantly observed by the guard, who sees everything from the tower.

In this way, windows are multivalent in their symbolism: If you have the freedom to see out, others can also see in. The window can therefore function as a symbolic inverse of the veil, which performs a different double duty, both to do with separation. A veil is both revealing and concealing. The window can never conceal, and is about revealing rather than concealing.

WINDOWS AS TOOLS OF DIVINATION

Certin Rabbinic scholars (Alshich, Albo, Abarbanel, Saba) interpreted Biblical passages about women looking through windows as attempts at divination. Examples are Sisersa’s mother looking through a window (Judges 5:28) and Abimelekh looking through a window (Gen. 26:8).

In earlier eras, women (and other disenfranchised people) were at risk of being accused of witchcraft and similar, and these interpretations by Rabbinic scholars during the eras of the witch craze are evidence of that. Because some light particles go through a pane of glass while others bounce back, windows took on some of the mysticism of mirrors.

By the way, physicists still have no idea why some photons go through glass while others bounce back. Each photon appears to be identical. For more on that, see Marcus Chown.

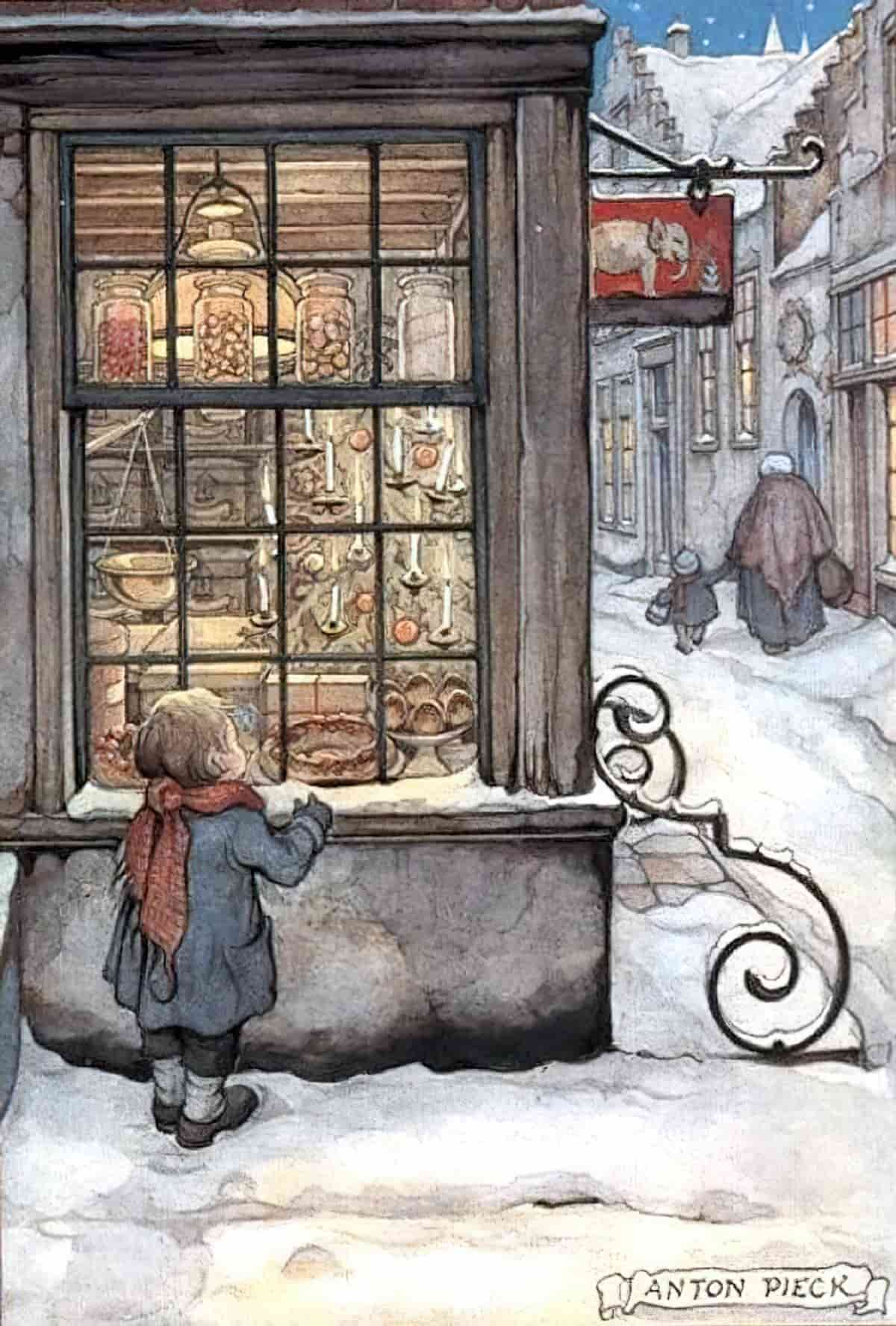

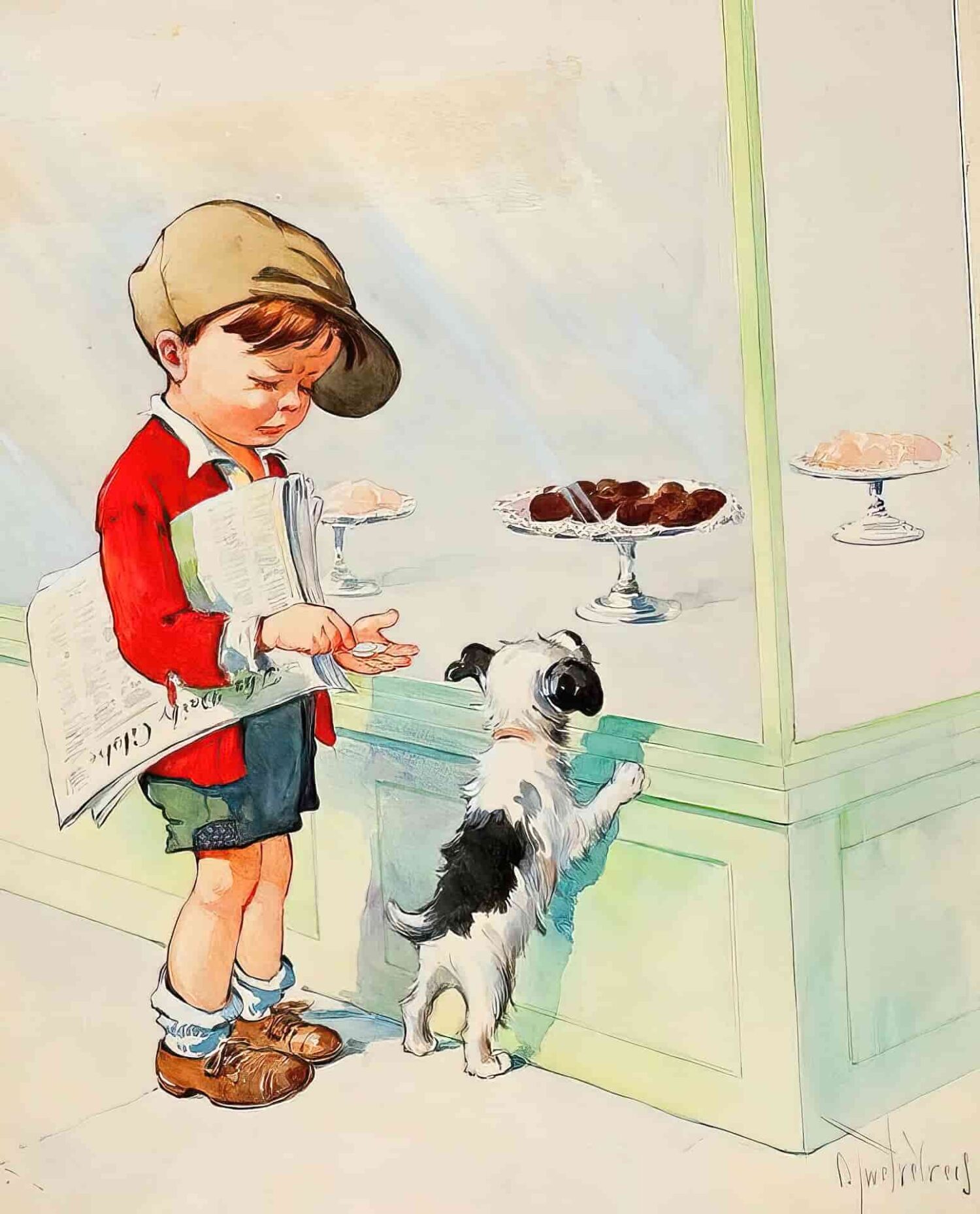

WINDOWS AND LONGING

The following scene from John Steinbeck’s Depression Era novel The Grapes Of Wrath is one of the most affecting for its unmet desire and reminder of poverty and hardship:

A 1926 Nash sedan puled wearily off the highway. The back seat was piled nearly to the ceiling with sacks, with pots and pans, and on the very top, right up against the ceiling, two boys rode. On the top of the car, a mattress and a folded tent; tent poles tied along the running-board. The car pulled up to the petrol pumps. A dark-haired hatchet faced man got slowly out. And the two boys slid down from the load and hit the ground. […] Their faces were streaked with mud. They went directly to the mud puddle under the hose and dug their toes into the mud. […]

The man took off his dark-stained hat and stood with a curious humility in front of the screen. “Could you see your way to sell us a loaf of bread, ma’am?”

Ma said: “This ain’t a grocery store. We got bread to make san’widges.” […]

From behind her Al growled: “God Almighty, Mae. Give ’em bread.” […]

Mae shrugged her plump shoulders and looked to the truck drivers to show them what she was up against. She held the screen door open and the man came in, bringing a smell of sweat with him. The boys edged in behind him and they went immediately to the candy case and stared in — not with craving or with hope or even with desire, but just with a kind of wonder that such things could be.

The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck

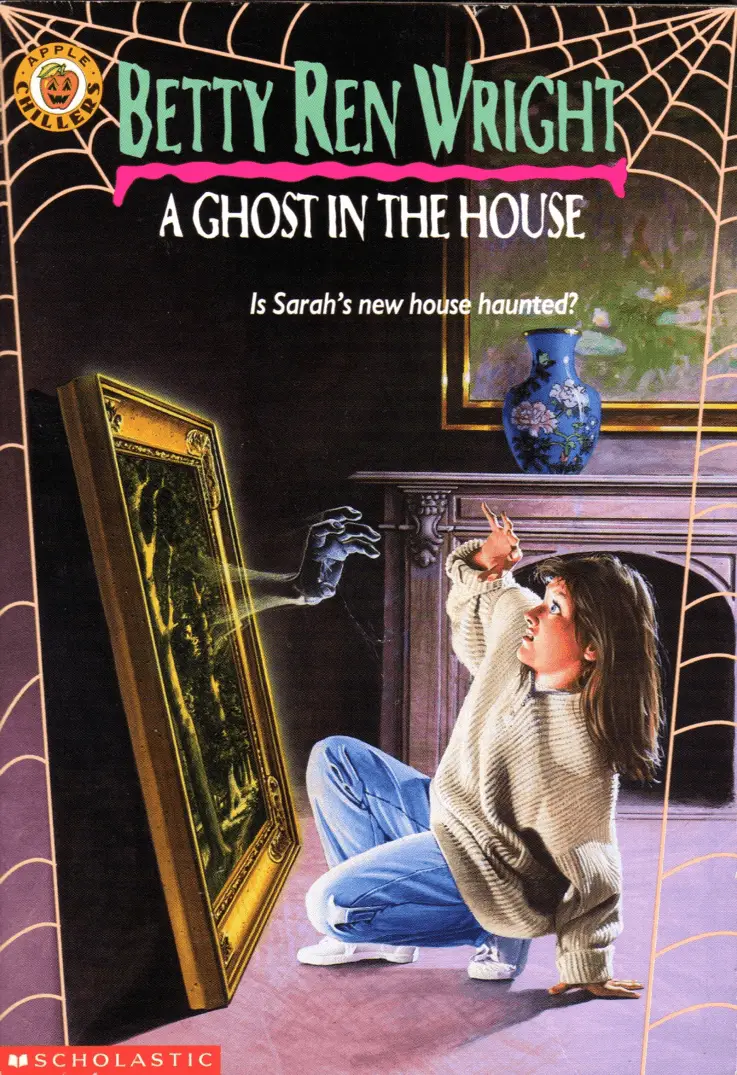

WINDOWS AS WEAKNESSES IN THE HOME WHICH ADMIT THE SUPERNATURAL

Windows, doors and chimneys all feature in ancient superstition. Each of these parts of a house open the home to the dangerous, outside world. They are each a threshold.

The window may be about ambiguity between inside and outside rather than about juxtaposition. In that case, there may be a ghostly feel to the work, or stories in which the occult becomes prominent and dominating.

The transparency of a window pane lends the poetically inclined towards ideas around translucence, Heaven, angels and everything associated with light and purity. A gaze out the window can help you reflection on your own position between the finite and the infinite (life versus the afterlife), and between the ephemeral and the immutable.

The window is a way of achieving phenomenal transparency. In this context, phenomenal means perceptible by the senses. Normally, transparency is not something that’s sensed. Air is transparent but we don’t normally notice it. But glass has a transparency that can draw attention to itself, being semi-reflective and solid.

CASE STUDIES: WINDOW SYMBOLISM

WINDOWS AND GUSTAVE FLAUBERT

Some stories mention windows a lot. Madame Bovary by Flaubert is one standout example.

In the gothic tradition, maidens gaze through a window and wiat for their heroes to arrive. This is frequently subverted. For example, Flaubert’s Emma waits for her hero but when he arrives he turns out to be the romantic avatar of her own personality.

In stories, characters frequently half know things. They sort of understand reality, but for some reason they’re loathe to acknowledge the full truth. Storytellers usually don’t let characters rest easy in their state of partial knowing. Writers generally give their characters the opportunity to see reality as it exists in the veridical world of the story. If characters refuse the opportunity, the story is a tragedy. If they are ready to see the truth, they undergo a beneficial character arc. When characters refuse to see reality, they generally lose two things: What we thought we desired and what we actually possessed. This is the case for Emma in Madame Bovary, where windows are heavily symbolic. Windows can be a useful symbol in stories about truth and reality because they offer a frame on the world which is only a partial view of it, until we go outside.

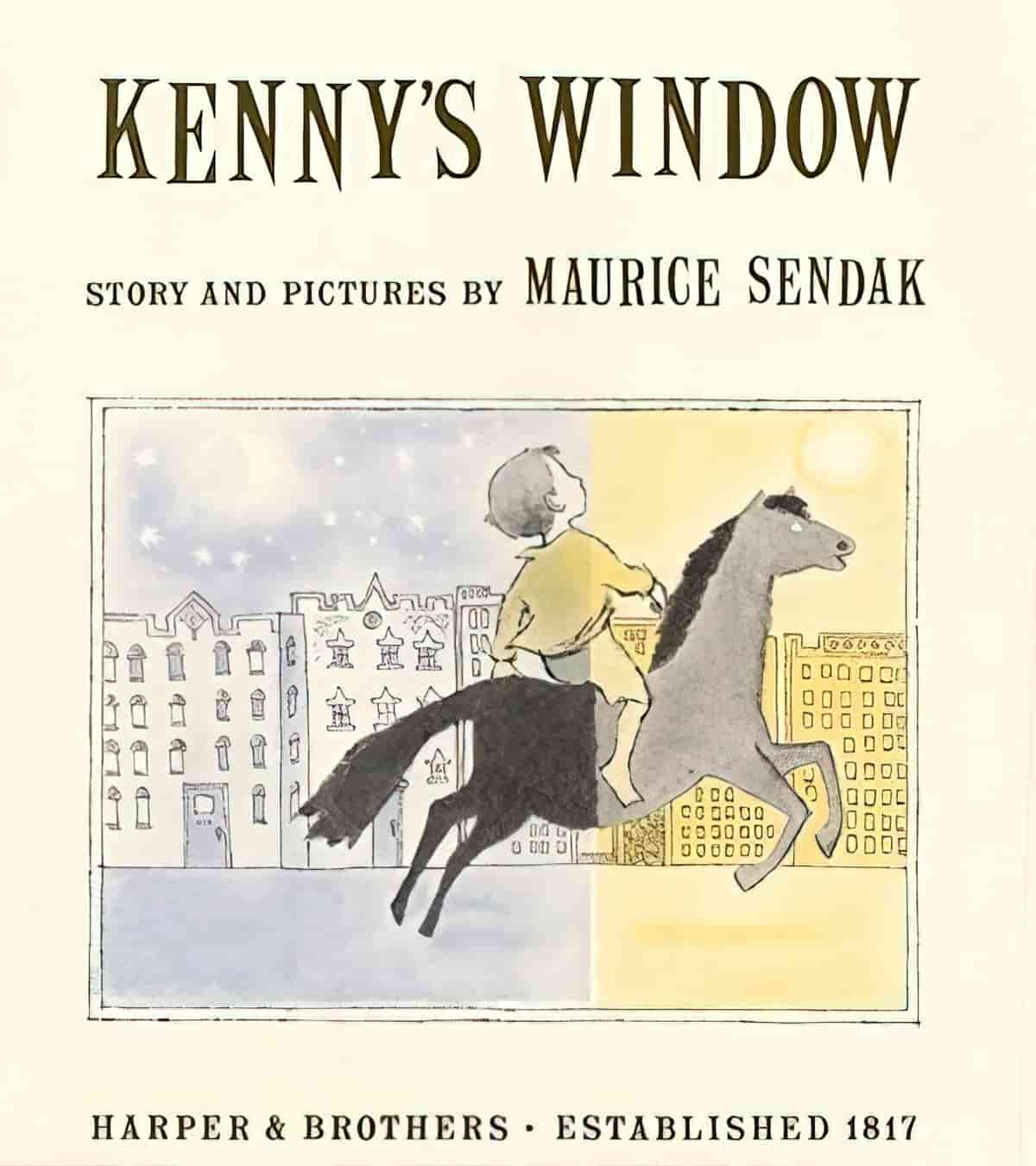

WINDOWS AND MAURICE SENDAK

[In the 1950s Sendak] was serving his apprenticeship illustrating the stories of others or creating his own stories and pictures about daydreamers and introverted loners who stare out the window (Kenny’s Window) at life taking place over there (Very Far Away). The breakthrough came with The Sign on Rosie’s Door (1960), when Sendak went through the window and (in his words) “outside over there” to create Rosie — an irrepressible Brooklyn kid who swaggers on stage in a boa and her mother’s high heels and whose infectious manner shows that she is daring personified.

Jerry Griswold

I noticed that a lot of the translations of Outside Over There have ‘window’ in the title, even though there is no ‘Window’ in the English language title. Here is a blog post from the translator of the Spanish edition of Outside Over There, called Sendak’s Windows.

For a case study in the various ways windows can be used symbolically, expanding upon the psychology of character, read “Prelude” by Katherine Mansfield.

- As in many children’s books, Kezia looks out of the window of her old house, which marks the end of her early childhood. She’s looking forward to a new section of her life in a new house.

- Her mother’s feelings towards her husband are clear when the husband craves intimacy, but Linda goes to the window and closes it because she’s cold.

- The open window (and the vase of flowers inside) downstairs at the new house signals to the reader that the inside meets the outside — this is ultimately a story of transitions on all the various levels.

- Alongside windows, “Prelude” also makes much symbolic use of mirrors — a more reflective kind of window.

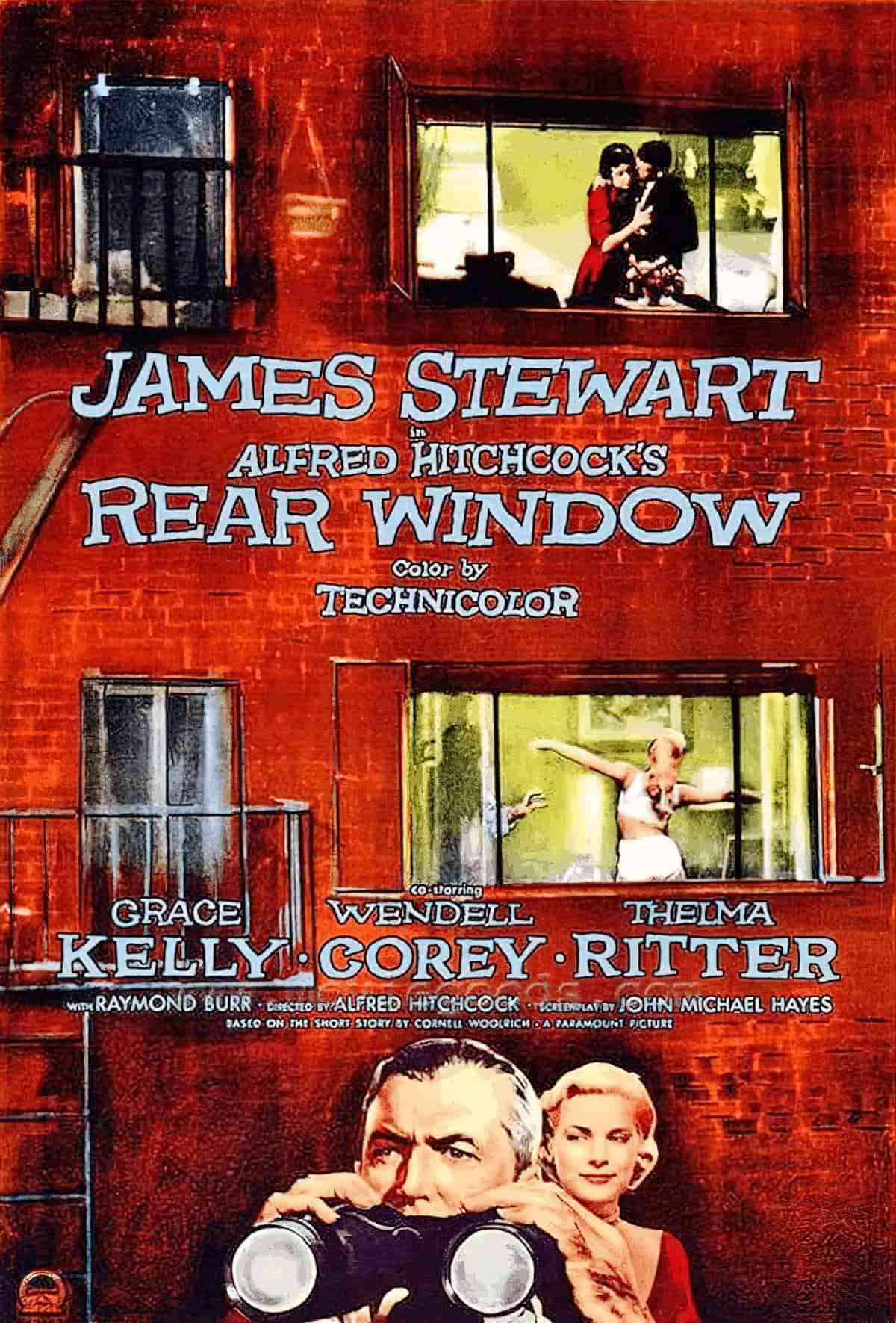

REAR WINDOW, ALFRED HITCHCOCK

In the film Rear Window, a convalescing man comes into possession of knowledge about neighbours. The gaze from a window, as we have now seen, is a very old motif. In the 20th century it took on new meaning (and continues to do so). In our city lives, full of technology, what are we to do — ethically — with information about others we happen to acquire, even if by chance of proximity and timing?

Since Rear Window, many crime stories have given a treatment to this moral dilemma. In recent literary history, The Girl On The Train is a tentpole bestseller example.

The Girl on the Train is a 2015 psychological thriller novel by British author Paula Hawkins that gives narratives from three different women about relationship troubles (caused by coercive and/or controlling men) and, for the main protagonist, alcoholism.

Rachel catches the same commuter train every morning. She knows it will wait at the same signal each time, overlooking a row of back gardens. She’s even started to feel like she knows the people who live in one of the houses. ‘Jess and Jason’, she calls them. Their life – as she sees it – is perfect. If only Rachel could be that happy.

And then she sees something shocking. It’s only a minute until the train moves on, but it’s enough.

Now everything’s changed. Now Rachel has a chance to become a part of the lives she’s only watched from afar.

Now they’ll see; she’s much more than just the girl on the train…

The Woman in the Window is a 2021 American psychological thriller film directed by Joe Wright from a screenplay by Tracy Letts (August: Osage County), based on the 2018 novel of the same name by controversial author A. J. Finn, the pseudonym of Dan Mallory, who has previously lied about writing autobiographically.

Mallory apparently took aspects of The Woman in the Window plot from a 1995 film called Copycat, which starred Sigourney Weaver as an agoraphobic professor, and co-stars Holly Hunter, Dermot Mulroney, and Harry Connick, Jr.

The story follows an agoraphobic woman (played by Amy Adams in the film) who begins to spy on her new neighbours and is witness to a crime in their apartment.

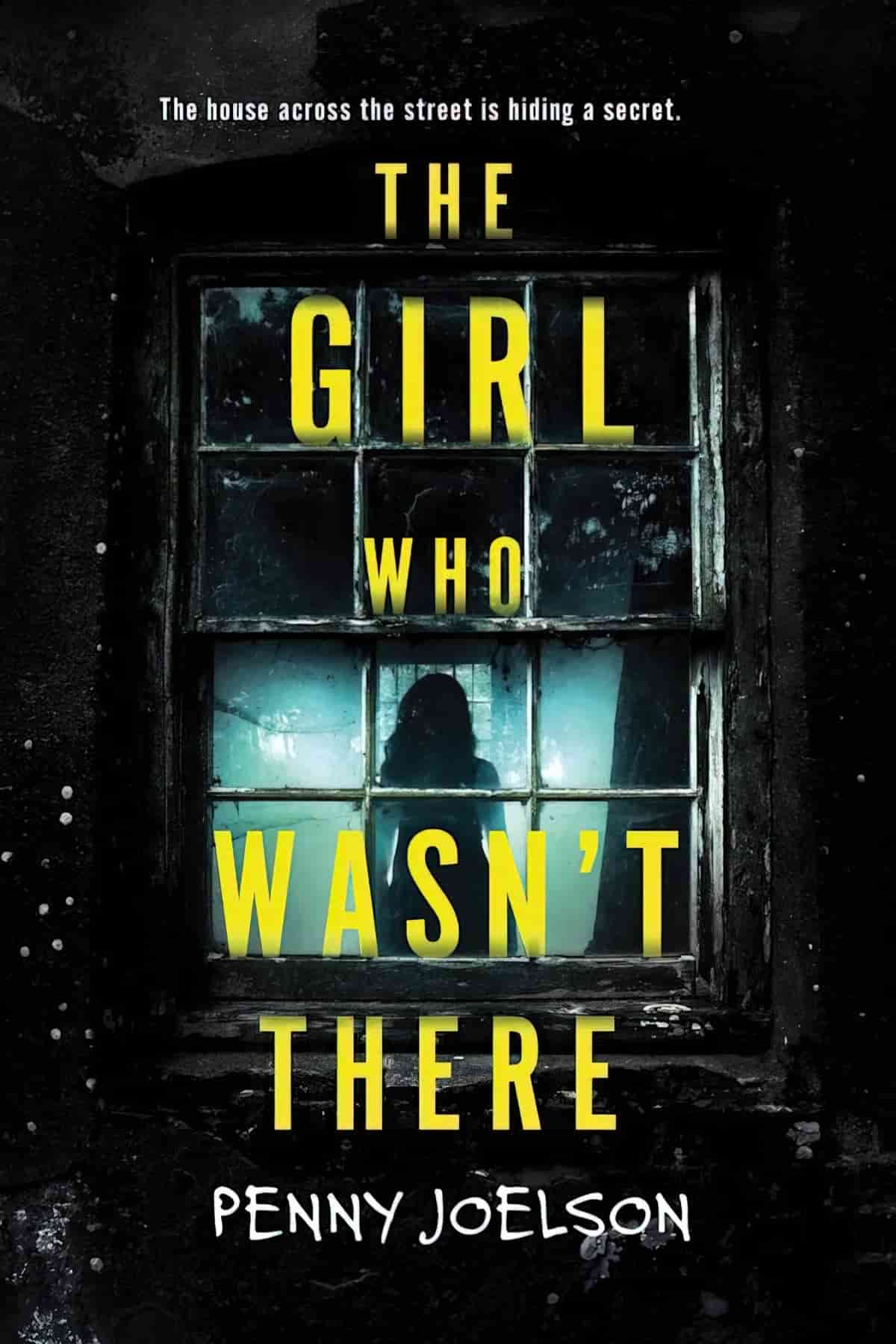

For fans of Karen M. McManus and Kara Thomas comes this riveting new young adult crime thriller packed with mystery and suspense, from the acclaimed author of I Have No Secrets

Nothing ever happens on Kasia’s street. And Kasia would know, because her chronic illness keeps her stuck at home, watching the outside world from her bedroom window. So when she witnesses what looks like a kidnapping, she’s not sure whether she can believe her own eyes…

There had been a girl in the window across the street who must have seen something too. But when Kasia ventures out to find her, she is told the most shocking thing of all: There is no girl.

QUESTIONS TO ASK WHEN READING A TEXT

If you’re immersed in a novel or film and you’re noticing frequent emphasis on windows, take this as a cue to look at point of view.

- Do windows signal changes in perspective?

- Do characters look from inside to outside?

- In any given scene, are the windows open, ajar or closed? Are they picture windows or tall, human-shaped windows?

- What might the characters be feeling when they are proximal to windows?

- Do they long for liberation? Liberation from what, exactly?

FOR FURTHER INVESTIGATION

A slideshow of windows in paintings by Larry Groff

Similar to the ‘leper squints’ in churches, wine windows, a.k.a. buchette del vino, are little windows carved into concrete walls. They allow beverage merchants to keep selling their goods during a pandemic, and maintain a safe physical distance.

Many mirror shots in movies are actually done using windows. The audience sees the back of the character’s head on the near side of the mirror, played by a body double. If you’ve ever taken a selfie in the mirror you’ll know why mirrors are no good for mirror scenes on screen: The camera ends up in the picture. (YouTube video.)

KENZARI, BECHIR. “Windows.” Built Environment (1978-), vol. 31, no. 1, 2005, pp. 38–48. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23289498. Accessed 18 Nov. 2022.

Jütte, Daniel. “Window Gazes and World Views: A Chapter in the Cultural History of Vision.” Critical Inquiry, vol. 42, no. 3, 2016, pp. 611–46. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26547623. Accessed 20 Nov. 2022.

TRANSPARENCY

Coming clean. Opening up. Seeing right through. Today, we’re talking all things transparent in the food world. From restaurateurs shaking things up with radical financial disclosure, to an enchanting clear dessert, our stories today explore the many meanings of transparency. What can we learn when we’ve got nothing to hide?

Transparent: Food with Nothing to Hide

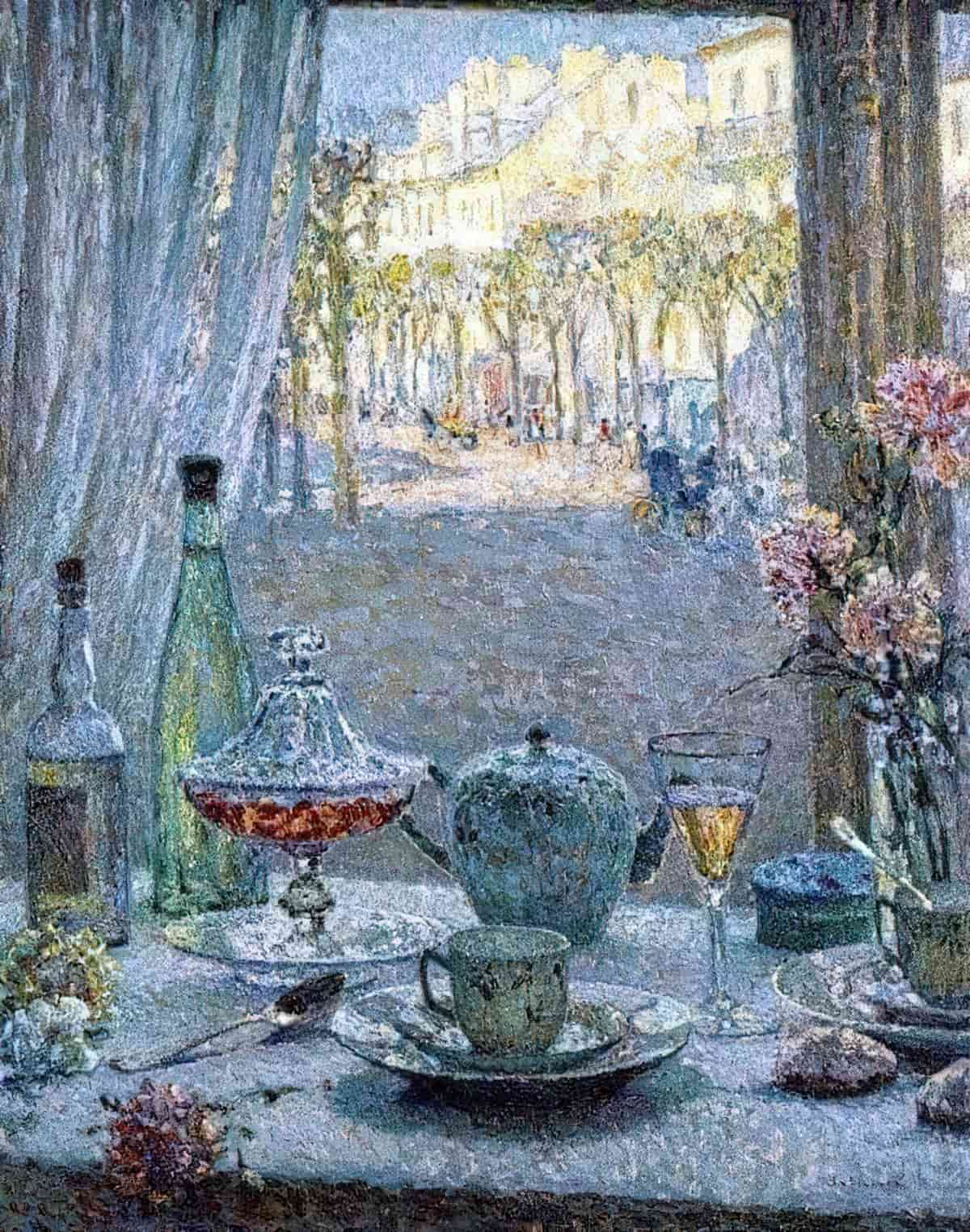

Header painting: Henri Le Sidaner (1862 – 1939) Table by the Window. Reflections, 1922