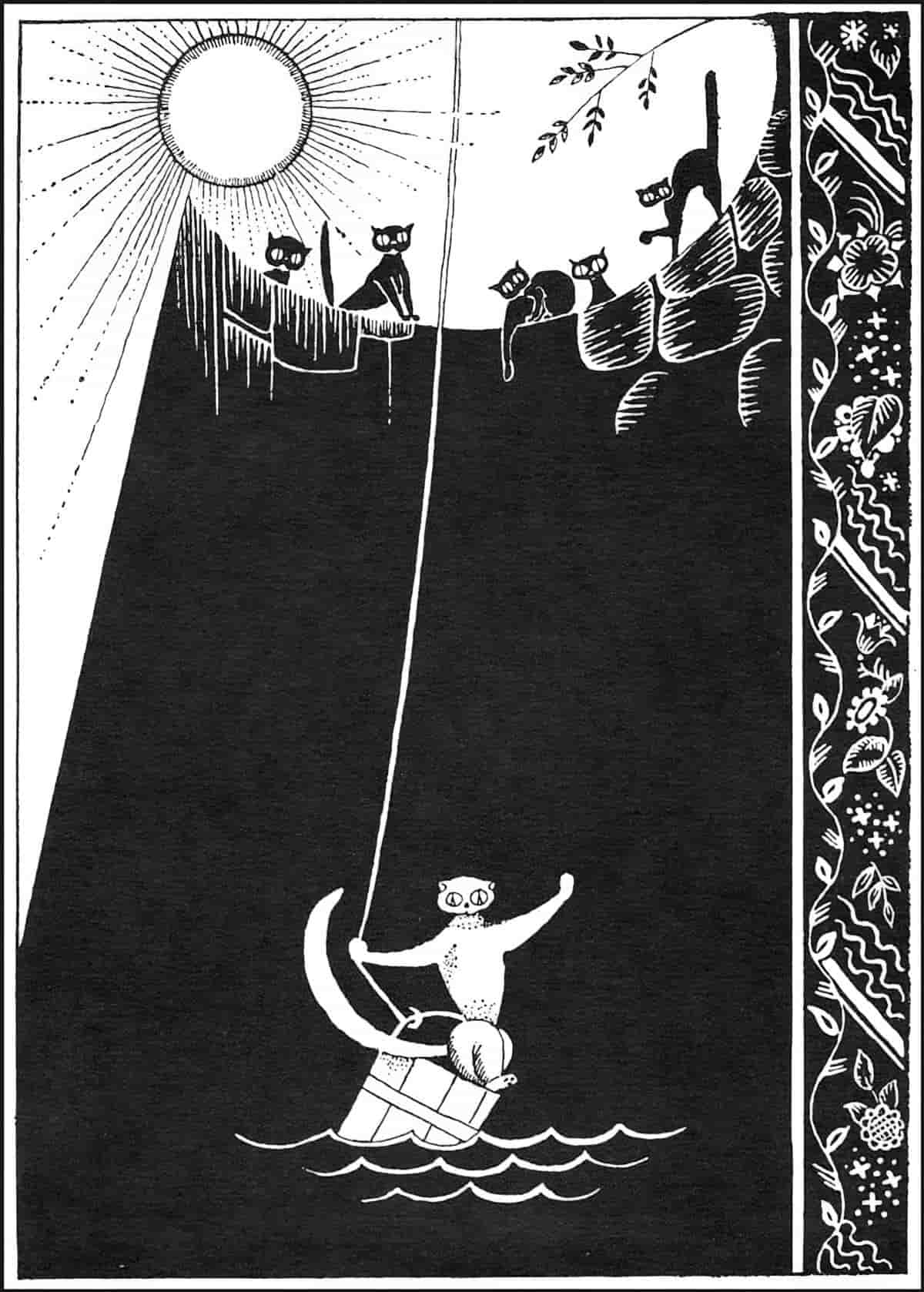

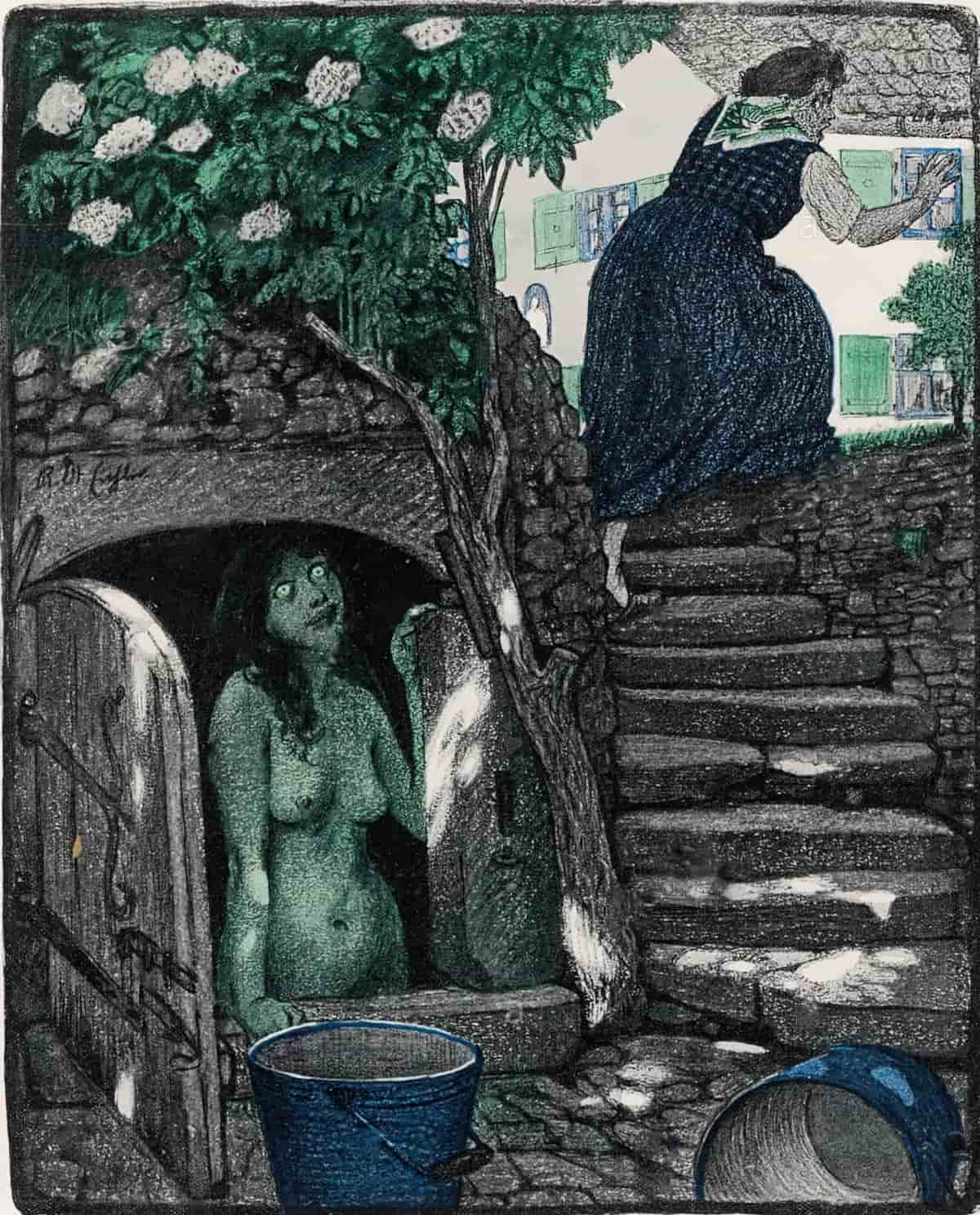

In folklore and fairy tale, round, enclosed structures (towers and wells) align with lunar figures which stand in for cyclic time i.e. dragons, serpents, werewolves or other related creatures who abduct maidens. And also, by the way, dishevelled hair and shaggy furs worn as garments are the other symbol set which go hand-in-hand with round, enclosed structures. These symbols are associated with moon phases, menstrual cycles and, more broadly, renewal through death.

(All of that is an excellent example of how symbols tend to appear in clusters rather than in isolation.)

In a very deep well you can see a star even on the brightest day.

IVAN’S CHILDHOOD | ANDREI TARKOVSKY (1962)

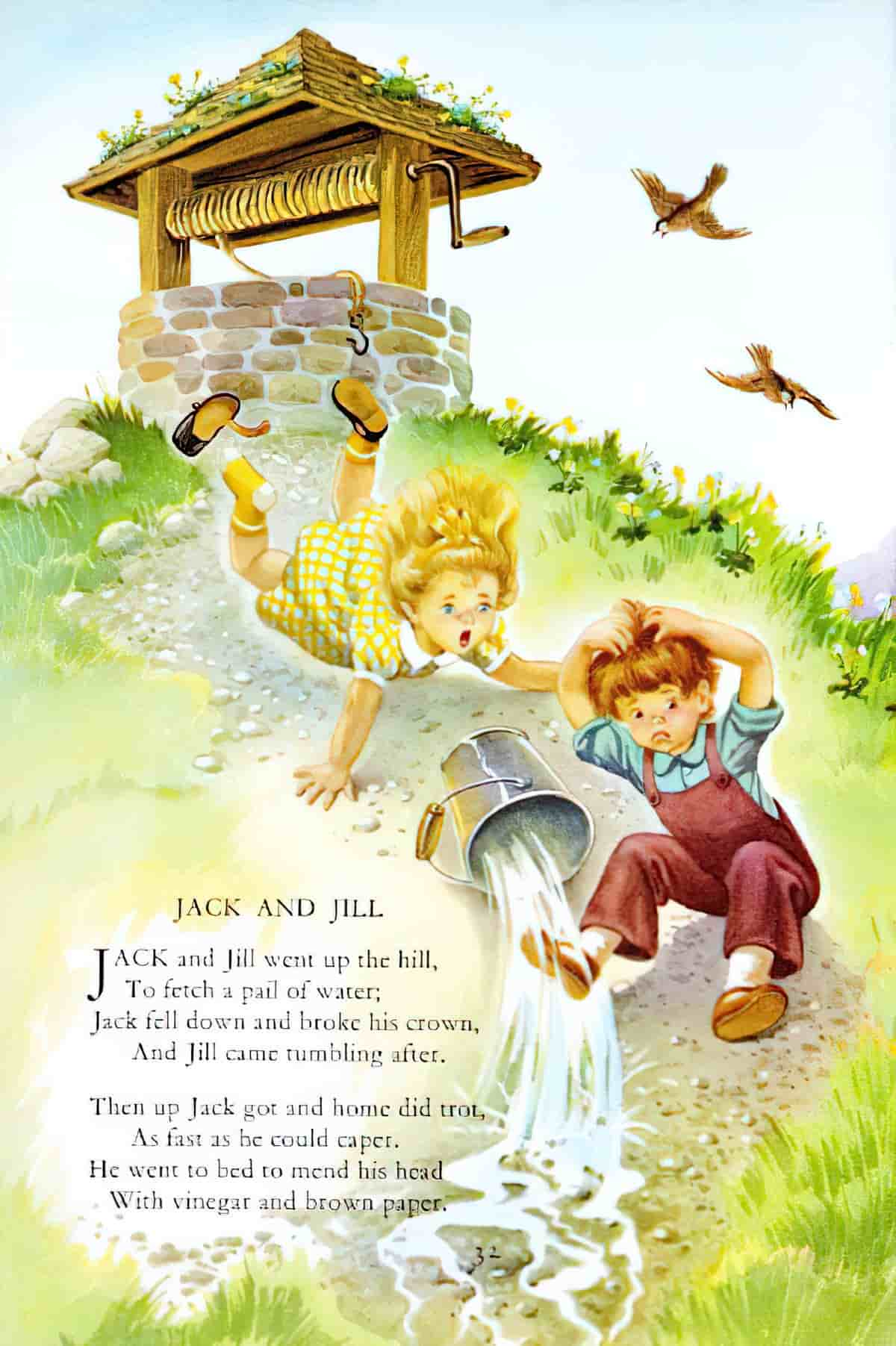

I didn’t have a well growing up because I didn’t live on a farm. Our water came out of the tap and that’s all I knew about the matter. But I did have a book of Mother Goose nursery rhymes illustrated by Hilda Boswell, and I also had a cat, so I knew wells were deep, dark, dangerous places.

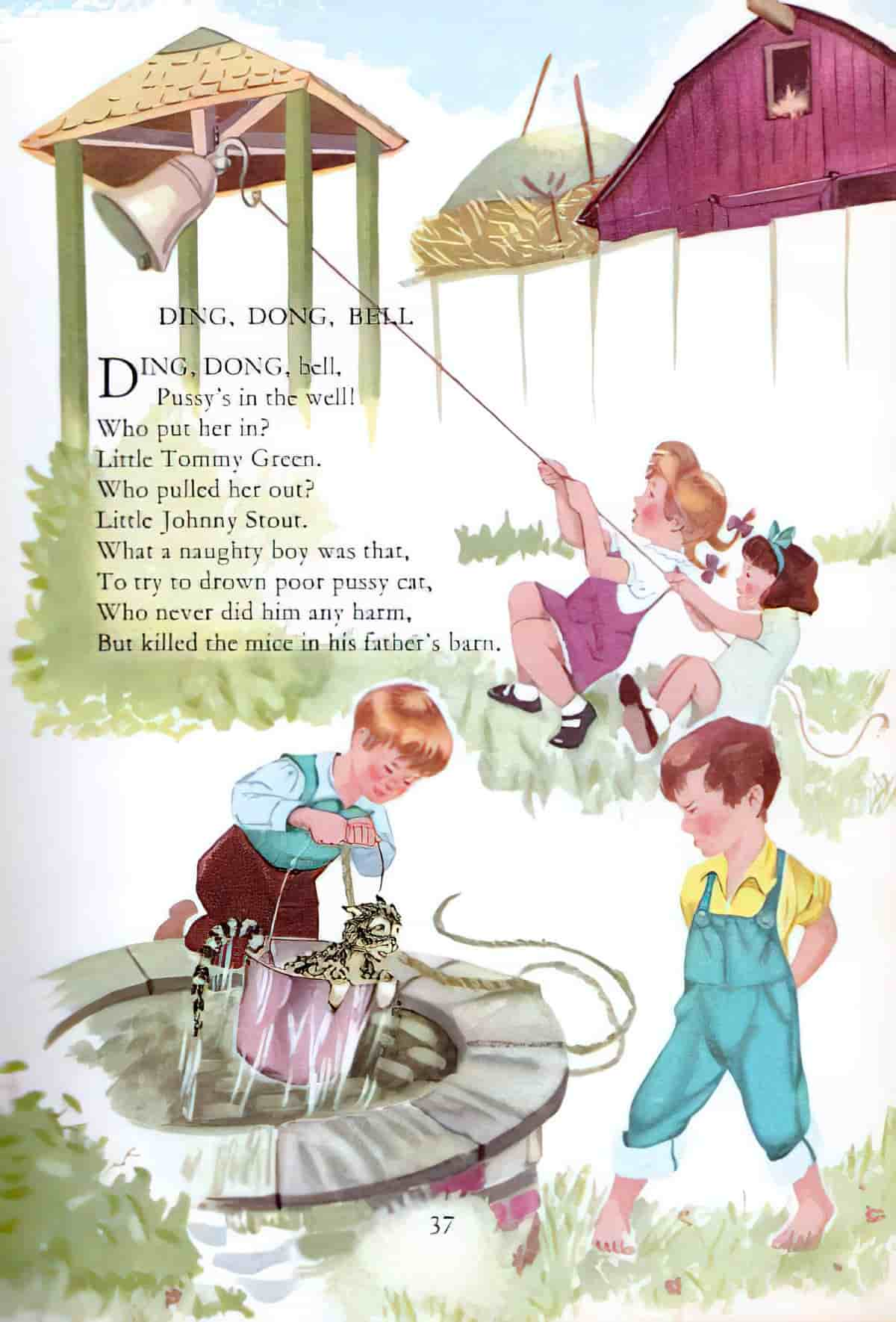

Ding, dong, bell,

by William Shakespeare, maybe

Pussy’s in the well.

Who put her in?

Little Johnny Thin.

Who pulled her out?

Little Tommy Stout.

What a naughty boy was that,

To try to drown poor pussy cat,

Who never did him any harm,

But chased all the mice in the farmer’s barn.

There are plenty of rhymes and stories from antiquity which caution children to behave compassionately. Some people think Shakespeare himself wrote the freaky “Ding Dong Bell” poem. There’s a famous song in The Tempest (1610) which is similar, though it’s about a drowned sailor, not a drowned cat.

Democritus, Wells & Truth

Let us travel back even further than Shakespeare. Ancient Greek philosopher Democritus (ca. 460 BC – ca. 370 BC) said, “Truth lies at the bottom of a well.” Why a well? The water in a well is often a long way down. He meant you have to look deep to find the truth.

Bodies of water in general give off a reflection and reflections have long been symbolically associated with truth.

This almost magical capacity is not limited to the water in wells. The beach is another setting with magical, mirror-like properties. When the beach is the setting of a love story, the (female) main character sometimes takes a holiday to a beach, enjoys its beauty and thereby discovers the beauty within herself. But when a beach is the setting of a horror story, the beauty of the beach juxtaposes against the evil within the main characters. In both kinds of stories, the beach acts as their mirror.

History and Superstition

Fresh water is perceived to be life-giving and healing. The many sacred wells associated with saints speak to older traditions of kindly female spirits dwelling in watery places.

But well worship goes back further than Christianity.

In ancient times, wells existed symbolically (and probably literally) at the centre of the community. In some communities today that is still the case. The well is therefore a symbol of community.

In ancient Israel, people would get married next to a well. Travellers would stop to water their camels there. It was the job of girls to collect water.

At the well they might meet their friends, providing a welcome opportunity to socialise.

Aryan tribes worshipped wells. As they travelled westward they spread this ritual.

According to Greek mythology, the Delphic oracle was a place (in Delphi, Greece) where prophecy was given. This place was originally a well surrounded by trees. Peasants would hang votive offerings on the trees. Later, kings would offer silver and gold and precious stones.

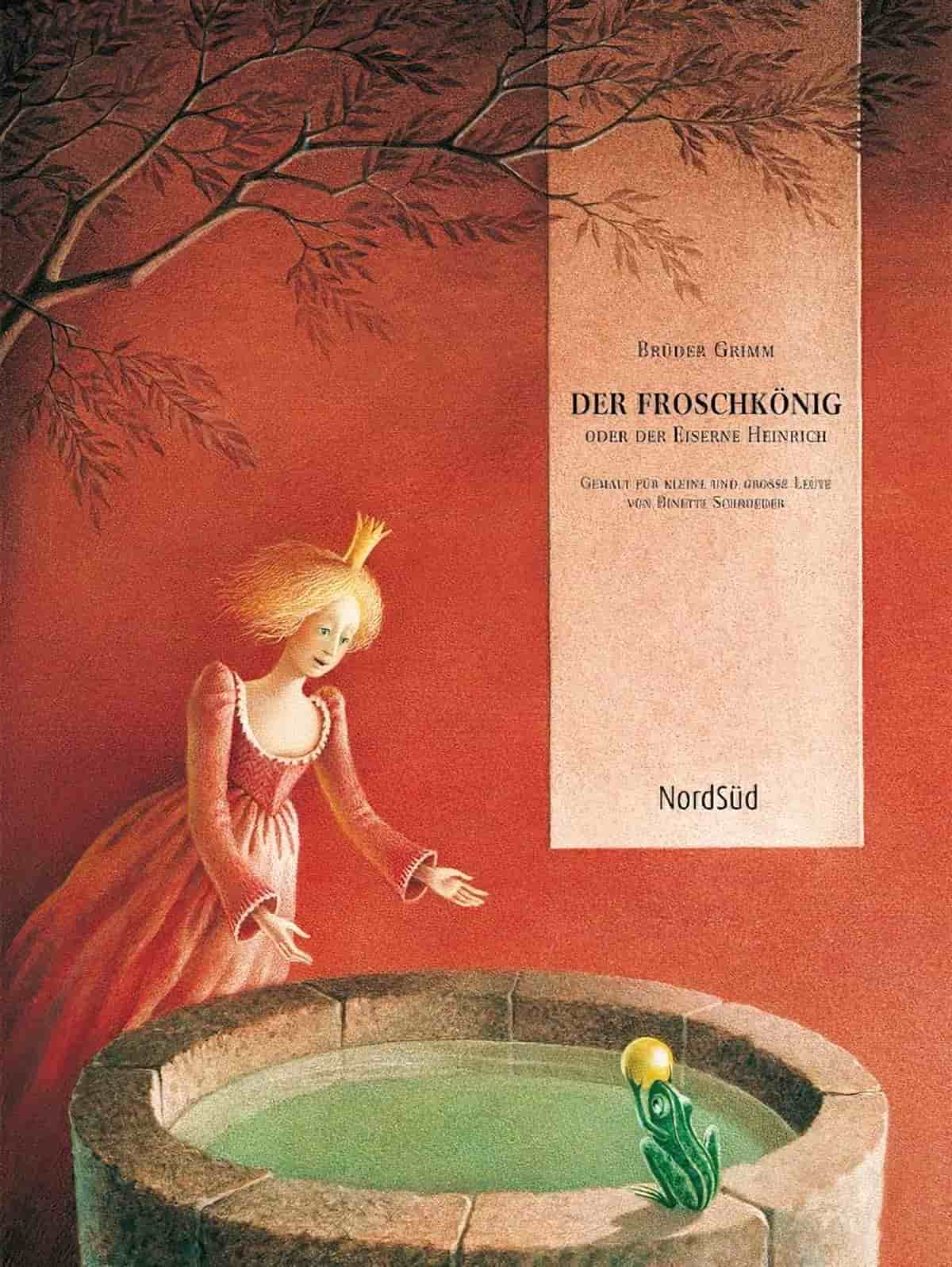

Well feature in fairytales, sometimes swapped out for another small body of water in retellings of the same story, such as a pond. “The Princess and the Frog” is a European fairy tale with a body of water at its heart. In some versions the body of water is a well. A frog lives in it. He transmogrifies into a prince after the princess is coerced by her father to ‘kiss’ him.

In an especially misogynistic tale, “The Blue Light“, a soldier turns into a woman hater after a witch keeps him captive for a bit. He exacts revenge by kidnapping the king’s daughter. Anyhow, the witch leaves him at the bottom of a well for a bit. He gets out because a little man appears. Turns out lucky for him; the well is connected to a network of tunnels, and the dwarf is able to lead him back up to safety.

If you’d like to hear “The Blue Light” read aloud, I recommend the retellings by Parcast’s Tales podcast series. (They have now moved over to Spotify.) These are ancient tales retold using contemporary English, complete with music and Foley effects. Some of these old tales are pretty hard to read, but the Tales podcast presents them in an easily digestible way. “The Blue Light” was published July 2021.

“Mother Frost” features a well or a body of water as a portal to an adjacent, utopian domestic setting for the main character. Significantly, when the girl sees her reflection, that’s when she becomes overwhelmed with a kind of vertigo and is drawn irrevocably into the well.

In Christian art, the well (or fountain) is the symbol of baptism, life and rebirth. A flowing fountain symbolises the waters of eternal life. The sealed well/fountain is a symbol of the virginity of Mary (along with the bower, the tower and the door).

IRELAND

In Ireland, wells are considered healing places. They were initially made sacred by Druid priests. Archeologists have found many Druid remains around wells. So we know the Druids danced, carved into stones and practised sun worship.

These rituals were incorporated into Christian ritual when Christianity arrived.

In Ireland, the well isn’t thought to have healing properties in its own right. The healing is thought to be achieved by honouring the saint associated with the well. The saint’s spirit is still over the well because he drank from this well while he lived on Earth.

If there’s a white-thorn or ash-tree overshadowing the well, the well is thought to be especially sacred.

A lot of early Irish texts refer to rivers that were associated with sacred or poetic wisdom and inspiration. The two best-known: The River Boyne and the River Shannon. In various versions of the story of Sinann, a woman approaches a well. She’s looking for knowledge. She follows a stream and ends up at a well. She drowns in the well. But she doesn’t fully die — she becomes the spirit of the river, Tuatha De Dannan. Same thing happens to Boand, a woman who approaches a well, also looking for knowledge, and walks around it three times. (Don’t do that.) The water rises up, she somehow becomes disfigured, drowns and transforms into the spirit of the river. What do these myths try to teach us about women who look for knowledge?

JAPAN

Wells are considered spiritual.

An ancient Japanese ghost story “Banchō Sarayashiki” (The Dish Mansion at Banchō) is about a woman called Okiko who was tossed into a well for romantically rejecting a samurai. Some versions have a strong sado-masochistic element, and Okiko is bound up, beaten and lowered in and out of the well numerous times by her torturer. It’s a very old story. Generally, Japanese horror never ended well for the woman. The male abusers would win.

In 1795, old wells in Japan suffered from an infestation of larvae that became known as the “Okiku insect”. This larva was covered with thin threads which made it look as though it had been bound. People saw this and actually believed it was a reincarnation of Okiku from the ghost story.

- The Girl From The Well is a young adult novel by Rin Chupeco based on the ghost story of Okiko. (Chupeco is Chinese-Filipino.)

- The Studio Ghibli movie My Neighbour Totoro features a beautiful image of a well in the new country house. A Japanese audience takes the cue: This is a magical, spiritual place.

- My Neighbour Totoro is a genuine utopia, but the other-worldly associations of wells, plus a strong folk horror tradition, wells also feature heavily in contemporary Japanese horror.

- The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle by Haruki Murakami includes a scene in which a soldier is thrown into a well.

- Dark Water is a 2002 Japanese horror film based on a short story by Koji Suzuki (who also wrote The Ring novels). In Dark Water, a divorced mother moves into a rundown apartment with her daughter and experiences supernatural occurrences including a mysterious water leak from the floor above. The water tank is a horrifying modern take on the ancient well.

Wells and Women

In Britain and Ireland (as mentioned above) wells were regarded as sacred. This is because they were connected to the Earth Goddess (gendered female). Later they became associated with Christianity and associated with female saints.

Some commentators suggest that the well is a symbol for the vagina — one big watery orifice. Or, in some ways, the well is like a nipple because you drink from it and it keeps you alive.

In Greek mythology we have the example of Lilith, with her leaky, problematic body, ‘too much’ for everyone. Her body indicates her evil nature. According to ancient thought, openness equals evil. According to some Hebrew stories it is dangerous to fetch water from wells at solstices and equinoxes because the wells become polluted by blood (referring to Lilith’s menstruation). Lilith flies through the sky, off to no good, and her blood drops into the well. Misogyny at its finest. Throughout most of history, and in most cases, women menstruate only when not pregnant; Lilith is a ‘failed mother’; her menstruation evidence of that, and therefore shameful. (Another story implies Lilith does give birth to children by eats them.)

The symbolism may be much more subtle than that. In Tibetan Buddhism wisdom (gendered female) is basically about understanding the nature of reality. If you understand that, then you are wise. The word Sunyata refers to this wisdom. It is sometimes translated into English as ’emptiness’ but comes from a Sanskrit root meaning ‘pregnant’ or ‘swollen with possibility’. There are crossovers and connections between Sunyata and Celtic mythology.

In short, wells may be connected to women not because of the misogynistic idea that women’s bodies contain ‘voids’ (absence of the phallus) but because Sunyata is about ‘plenitude of the void’. Think of possibility caused by absence. The ‘void’ in this context has a pleasant connotation, unlike the English word.

Unlike a patriarchal god, a Goddess of a well might be about liberation — about the free will we can enjoy when we have a bit of ‘void plenitude’ in our lives. Possibilities and self-actualisation can flow out of the ground when there’s an opening like that.

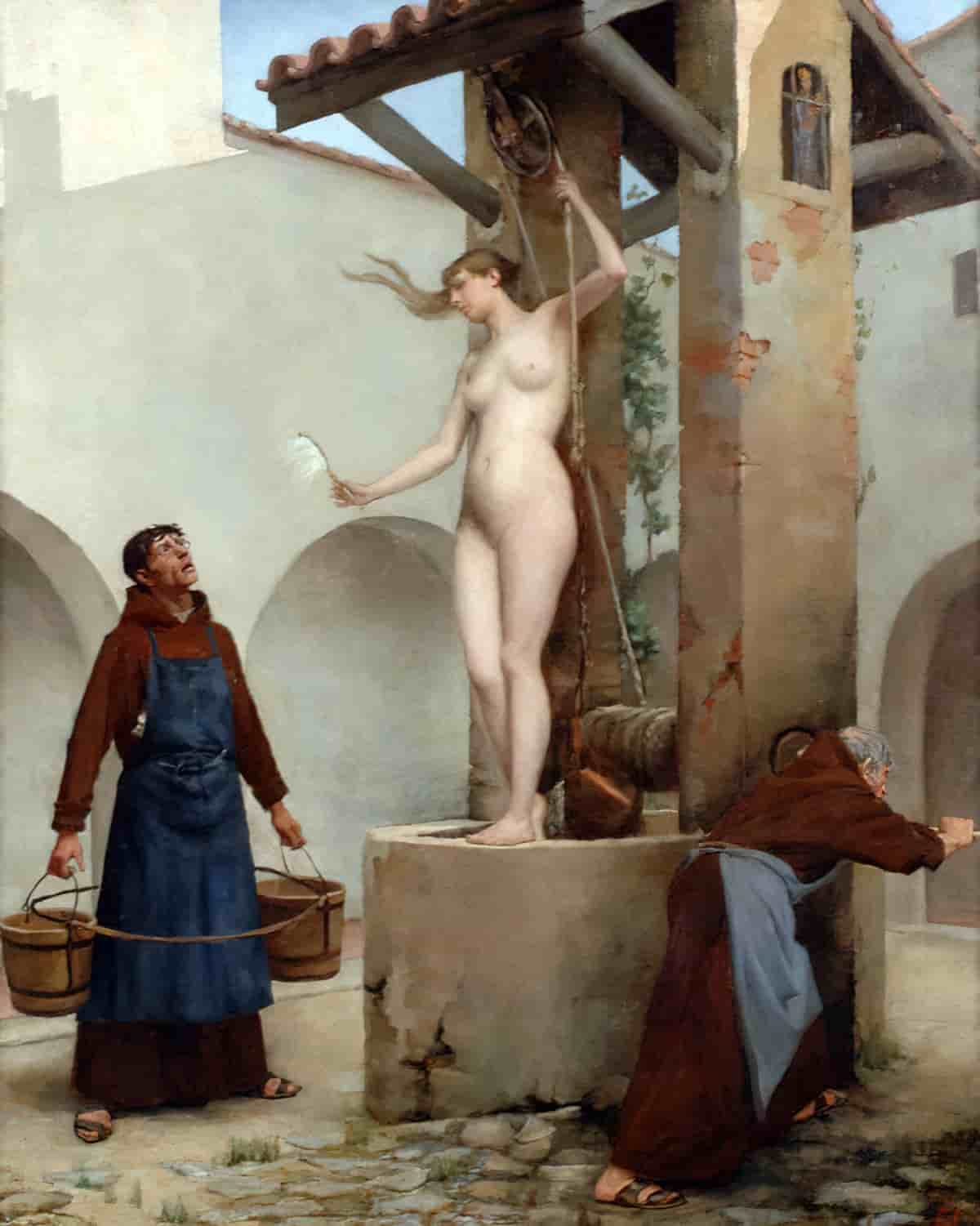

What does the personification of Truth look like? She is gendered female. This is similar to Tibetan Buddhism, in which wisdom is also gendered female. (Lady Tara is the wisdom goddess.)

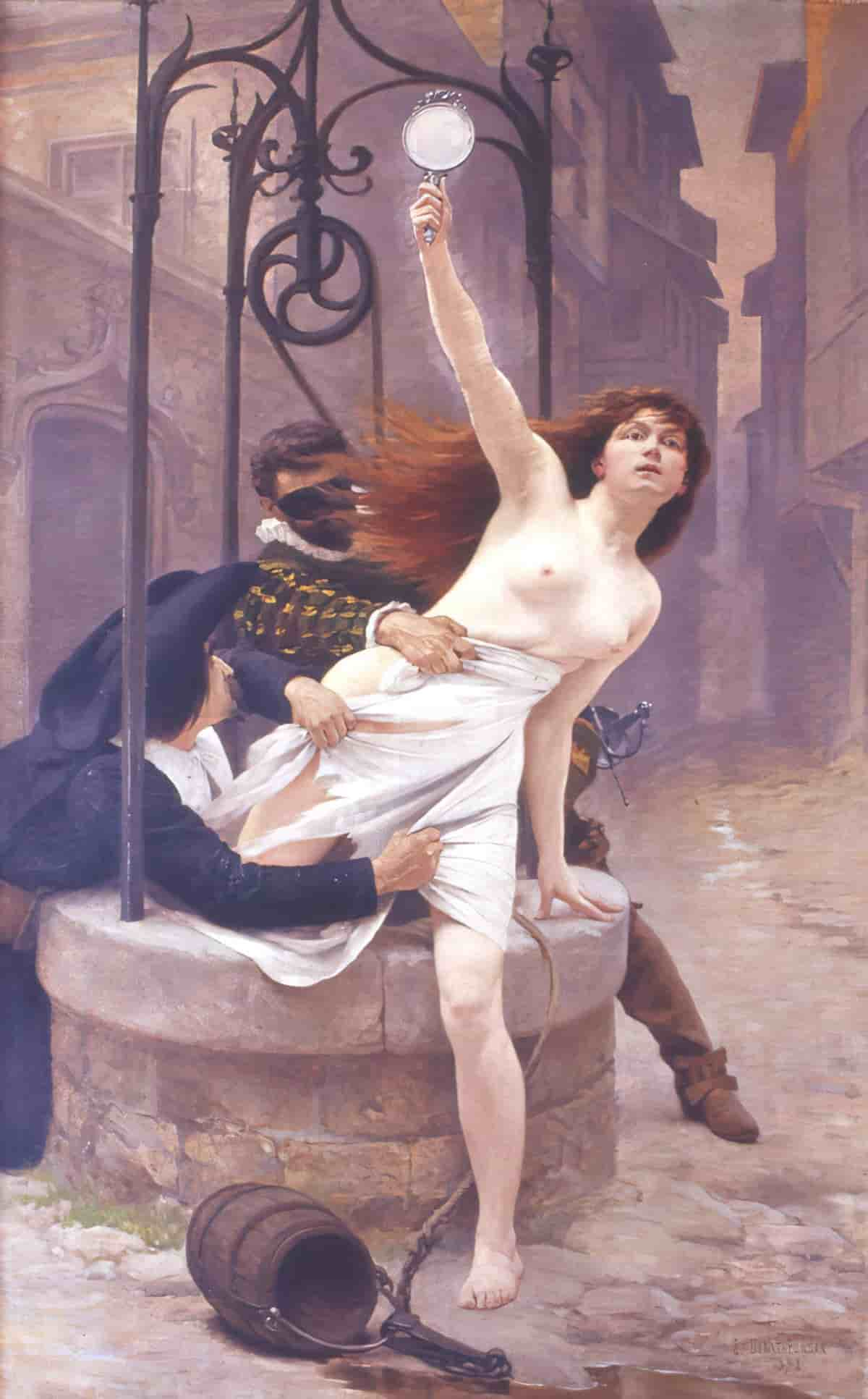

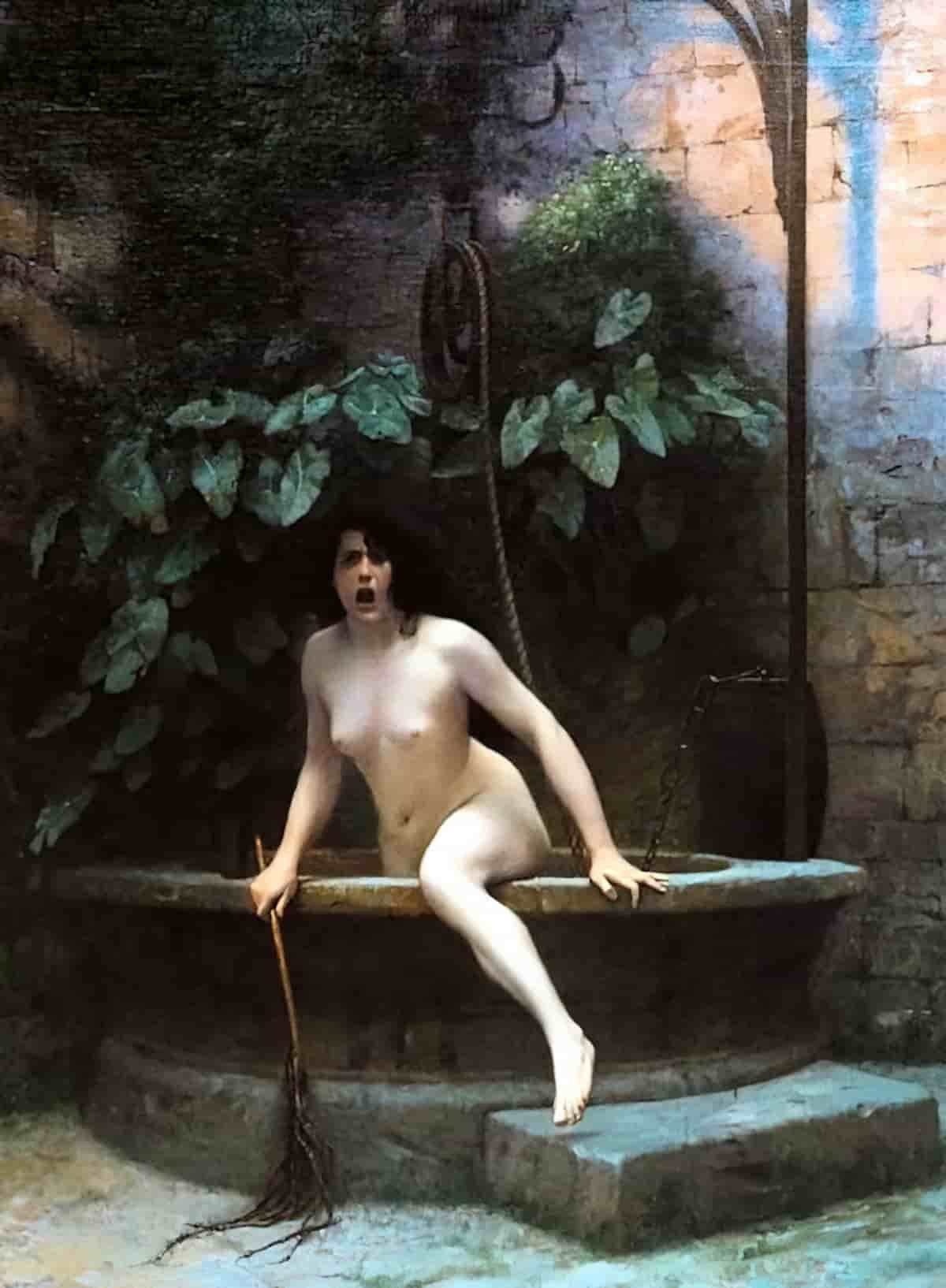

In the painting by Jean-Léon Gérôme, Truth emerges from a well holding a scourge. She wants to shame and punish humankind. Some have interpreted the painting as a reference to the Dreyfus affair, while others discuss it in the context of a quote by Gérôme that “thanks to photography, Truth has finally left her well.” – [WTF Art History]

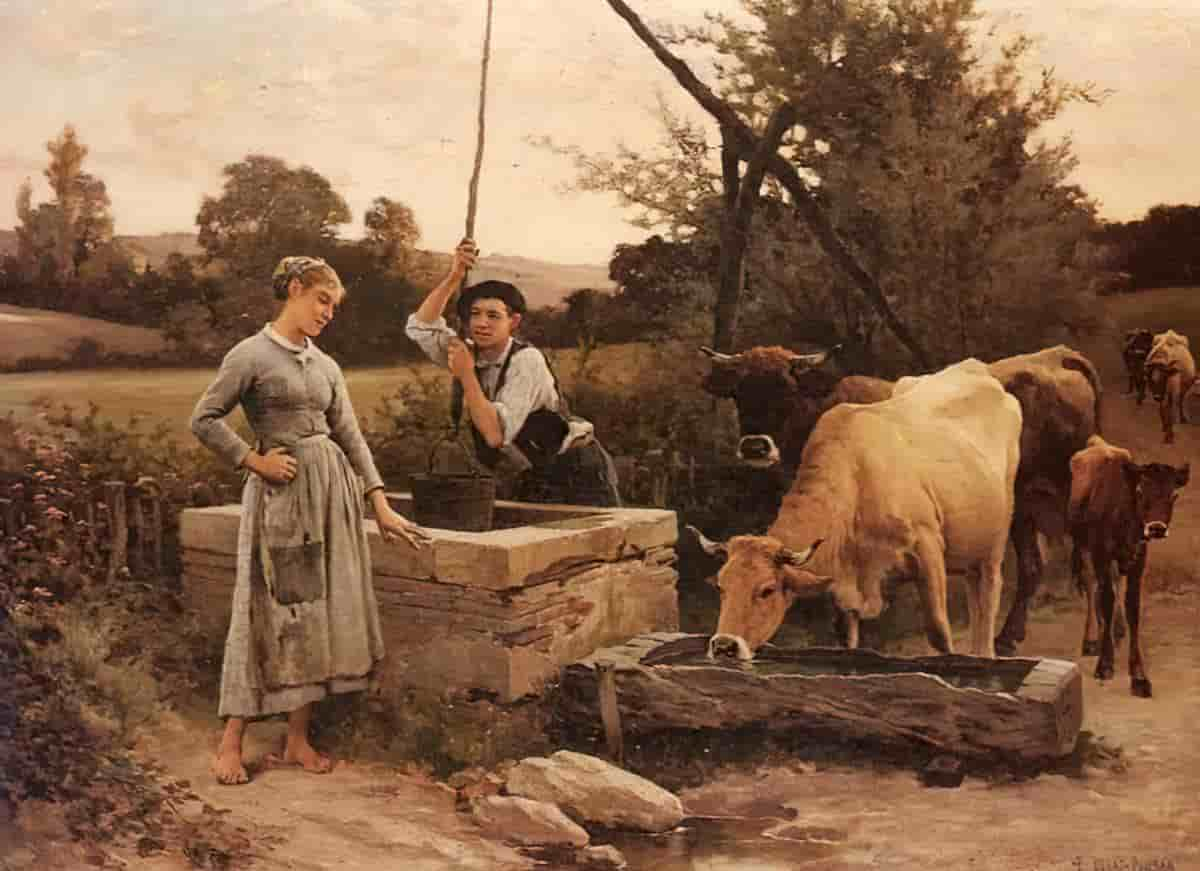

Painter Daniel Ridgway Knight also associated young women with wells. Women’s lives did indeed revolve around wells — it was a woman’s job to collect water. If you’ve ever had to collect water (say, on camp) you’ll know what a time-consuming chore this is. But is Ridgway also making use of mythology in these pastoral images below? When two young women talk beside the well, does the mythological connection between wells and truth indicate two characters connecting at a deeper, more truthful level?

Header painting: Henry John Yeend King – By the Well