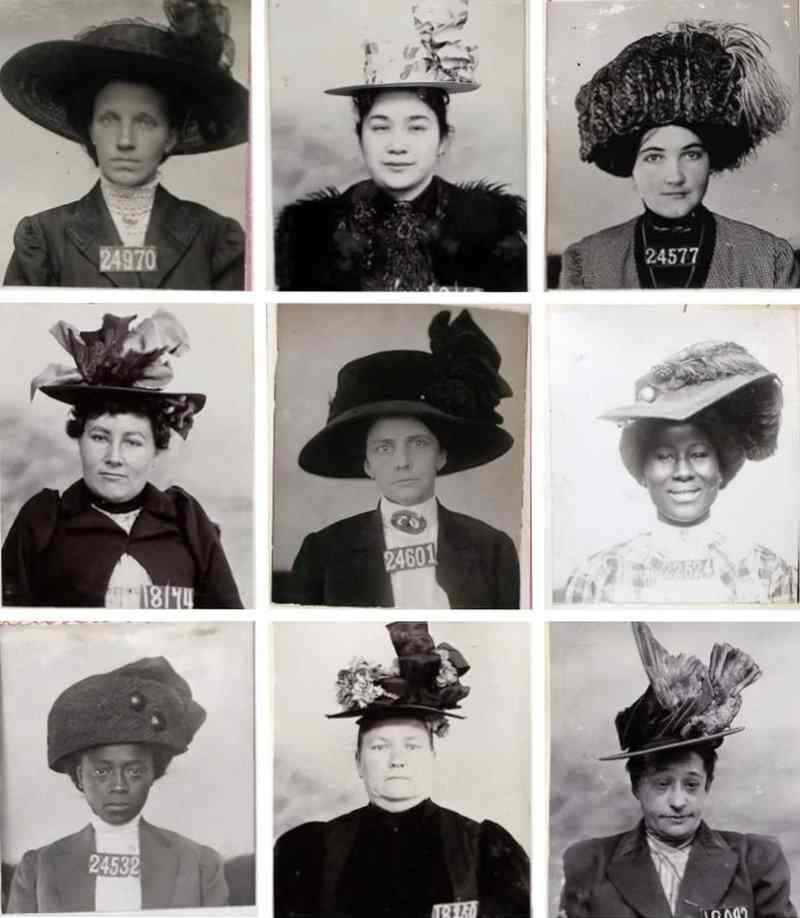

In various territories around the world it is considered improper to leave the house without covering your head. We tend to put this down to religious beliefs of the area, though it is mostly cultural. People younger than about 60 may not be aware that until quite recently it was impolite in Western countries to appear in public without headgear. No hat, not dressed.

My favourite regional Australia story is this one time in Warwick where a guy in a cowboy hat took one look at the top hat I was wearing and said “nice hat,” <f-slur> as we passed each-other on the street. It shocked me for a sec, like, we were BOTH wearing ridiculous hats? What?

from Twitter

My mother was a child of the 1950s. When we watched Mad Men together she noticed an inaccuracy. Unless America was vastly different from New Zealand, the real world secretaries of Madison Ave would have been wearing hats, even in the office. Don Draper would have also worn a hat more than depicted on the show. He was an old-fashioned guy.

Lack of hats on Mad Men was an anachronism, possibly a stylistic choice which allowed the viewer to get a better look at actors’ faces. (For the same reason we rarely see characters on screen wearing sunglasses outside.)

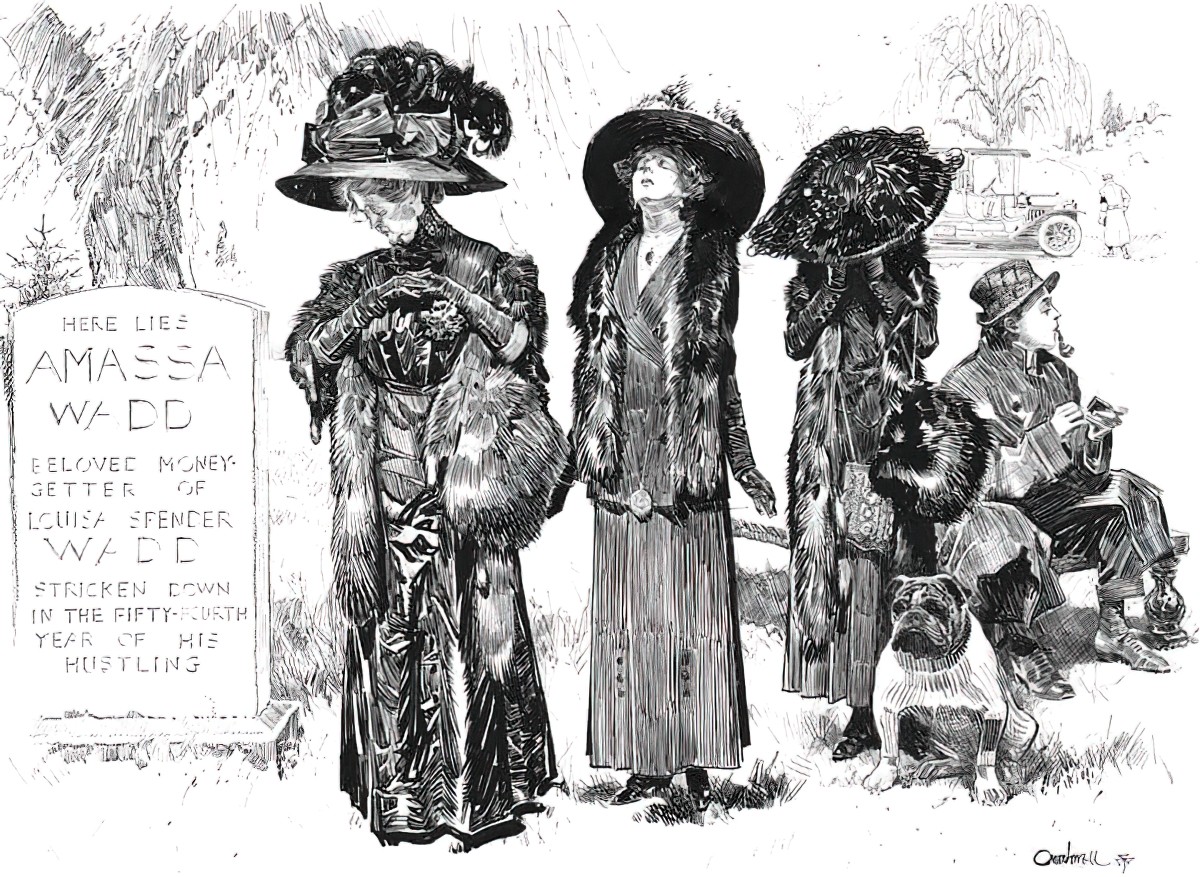

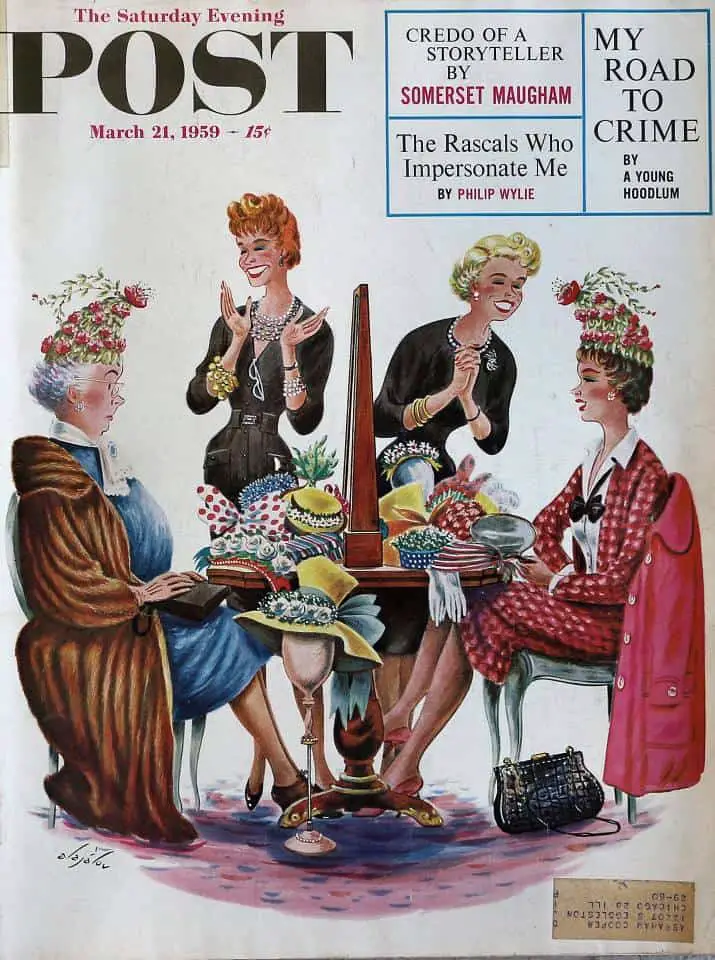

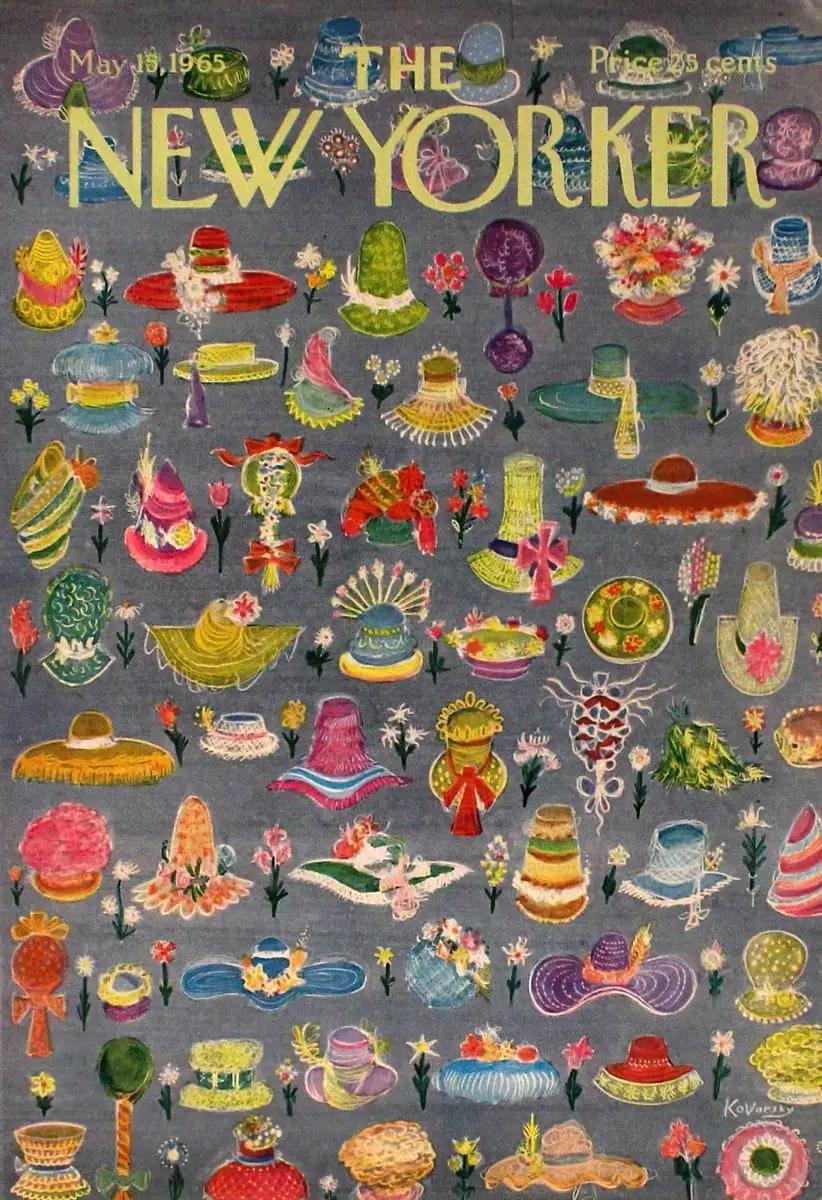

The painting below demonstrates how, in earlier eras, women’s decorative hats were considered a part of their day wear, not necessarily functional, and therefore worn inside.

These days, here in New Zealand and Australia, hats are mainly worn for practical reasons — hard hats on building sites, sun hats under our harsh UV rays. Hats are also worn on certain specific occasions, for example by women to The Melbourne Cup (as fascinators).

But why is headgear so important in many places across most eras?

Hats and Status

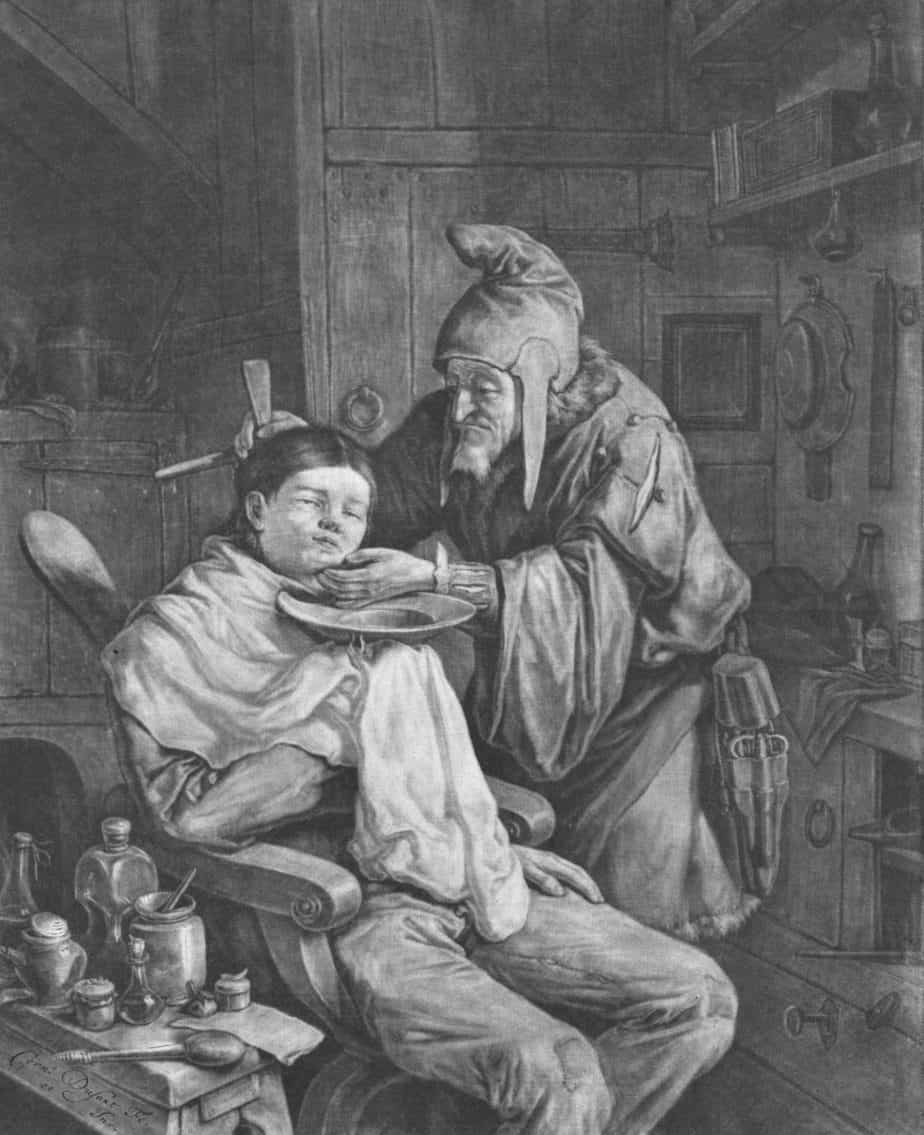

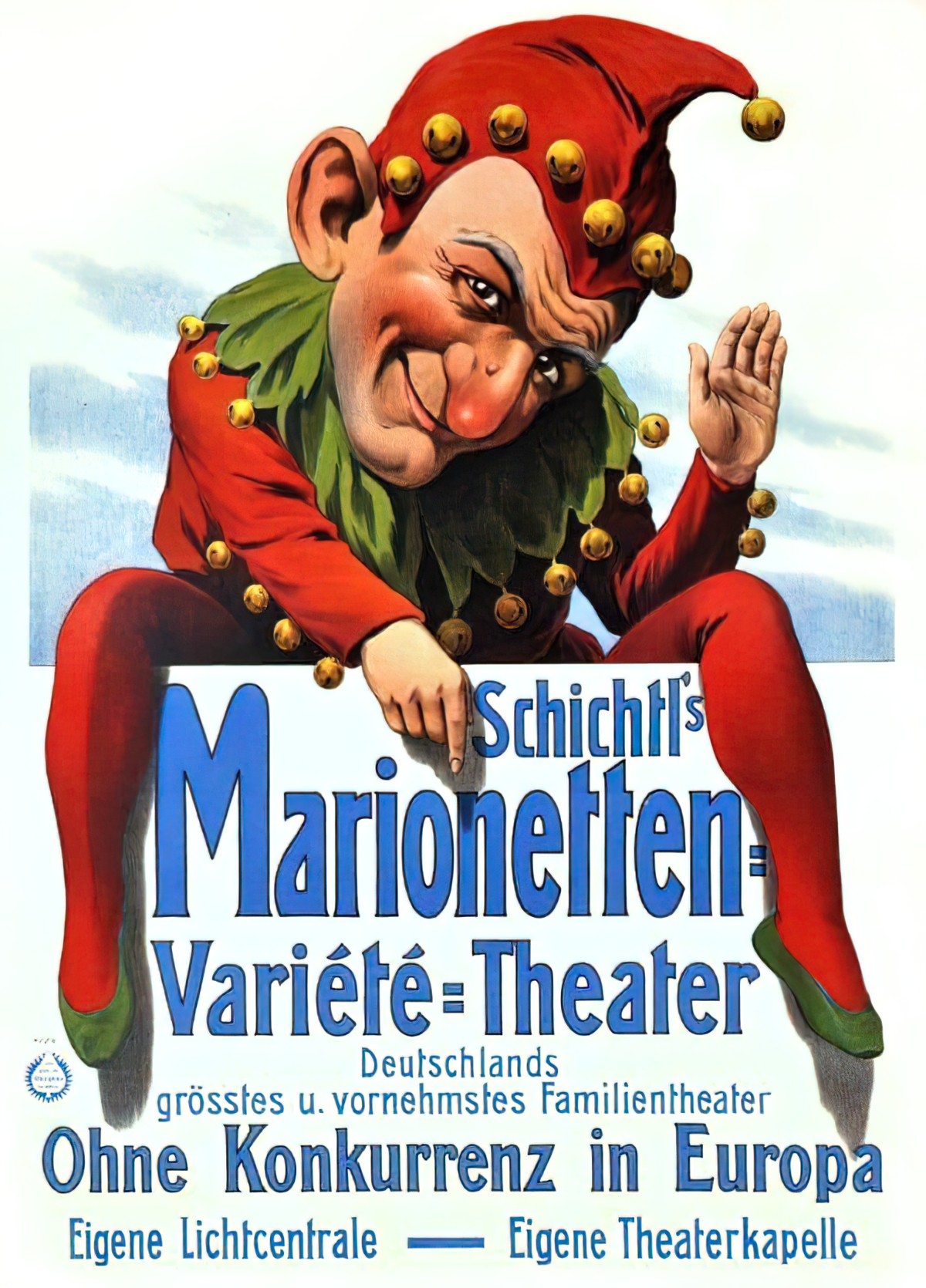

Headgear identifies the status of the wearer. Peaked hats in general authority. The witch’s hat is very tall and spiky. The hat supposedly contains the essence of her magical power in the form of a spiral of energy. The medieval Jewish hat and the papal tiara (triregnum) are also tall and spiky. Some believe these are phallic symbols.

A crown means royalty, and is the clearest example of headgear as status symbol: There is literally no reason to wear a crown other than to show off your status. Crowns can be so heavy they would’ve given the wearer a headache.

Crowns are circular and therefore inherit the symbolism of the circle — eternity, immortality and a connection between the spiritual and material world. This is symbolised by the coronation itself.

Jewels are often affixed to a crown. These are expensive and pretty, but also symbolise rays of sun. The wearer becomes one with the ‘illumination’ from above. Read illumination in all senses — someone who wears a crown achieves illumination — greatness, knowledge, power.

The Catholic Pope wears a triple crown. It’s called a triregnum. The three parts symbolise different aspects of the Catholic faith and of their papal role.

Crowns aren’t always made of precious metals and jewels. A crown made of laurels signals victory and carries equivalent status. In Ancient Roman times, the highest accolade for a soldier was to wear a crown of grass. A crown of grass was called a corona graminea. It meant he now owned the territory.

Native Americans traditionally make use of feathers to indicate status. The feathers themselves signify the different qualities of the birds they belong to. The most valuable feather is the eagle feather.

In contrast, beggars take off their hat (‘cap in hand’) in order to collect coins in it, but also to defer. An uppity beggar won’t have much luck.

The top of the head is a sacred part of the body because it’s closest to the heavens, and first contact with spirits who descend from above. In sacred places you take off your shoes but worshippers are likely to cover their heads. Both acts signal modesty and deference.

An excellent example of this belief is the skullcap worn by Orthodox Jews (the yarmulke or kippah). The Torah says no man may walk more than four paces without head covering. The head should always be covered in the presence of God. God is believed to be omnipresent. Many other faiths also require the covering of heads, though mainly in a place of worship.

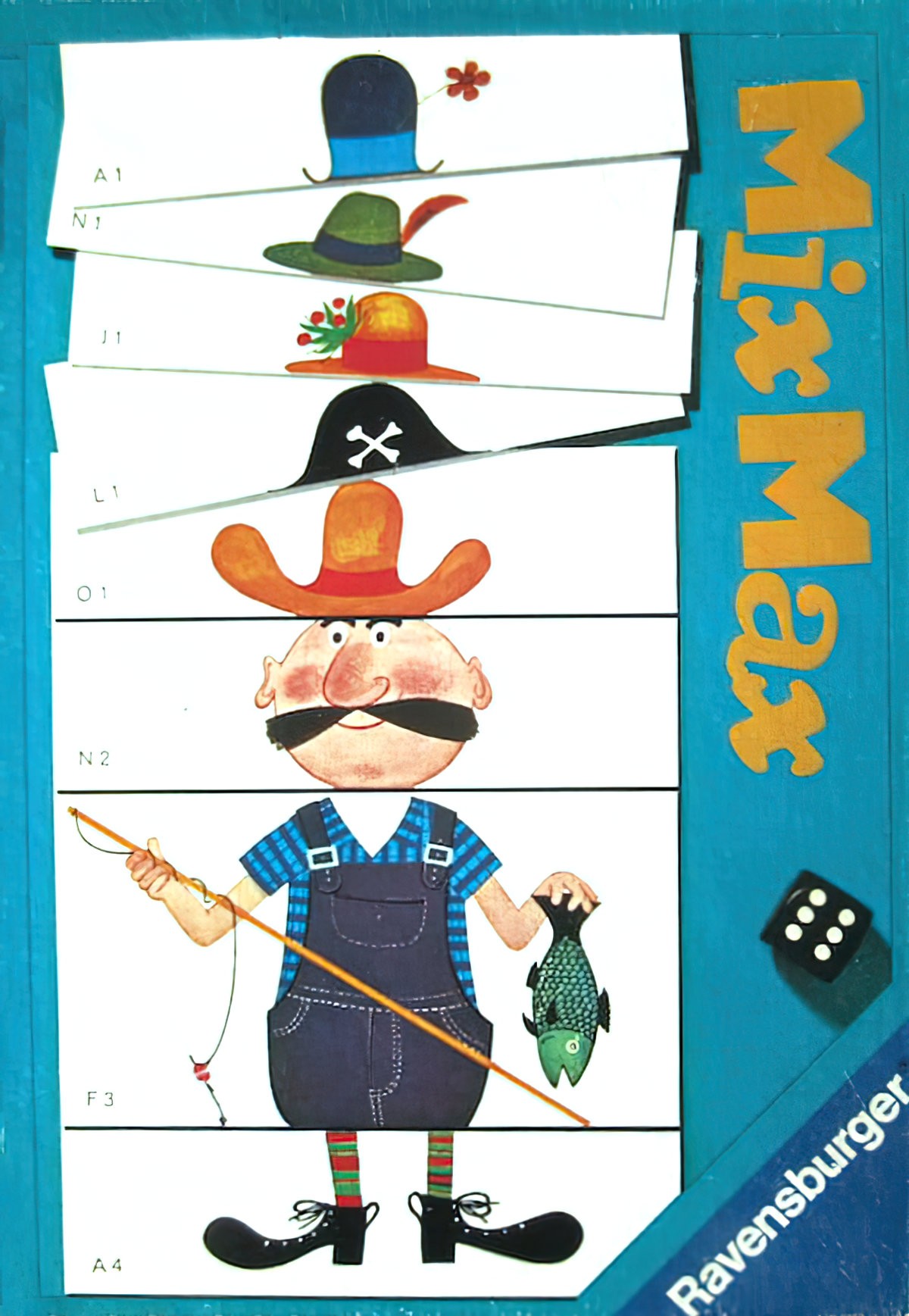

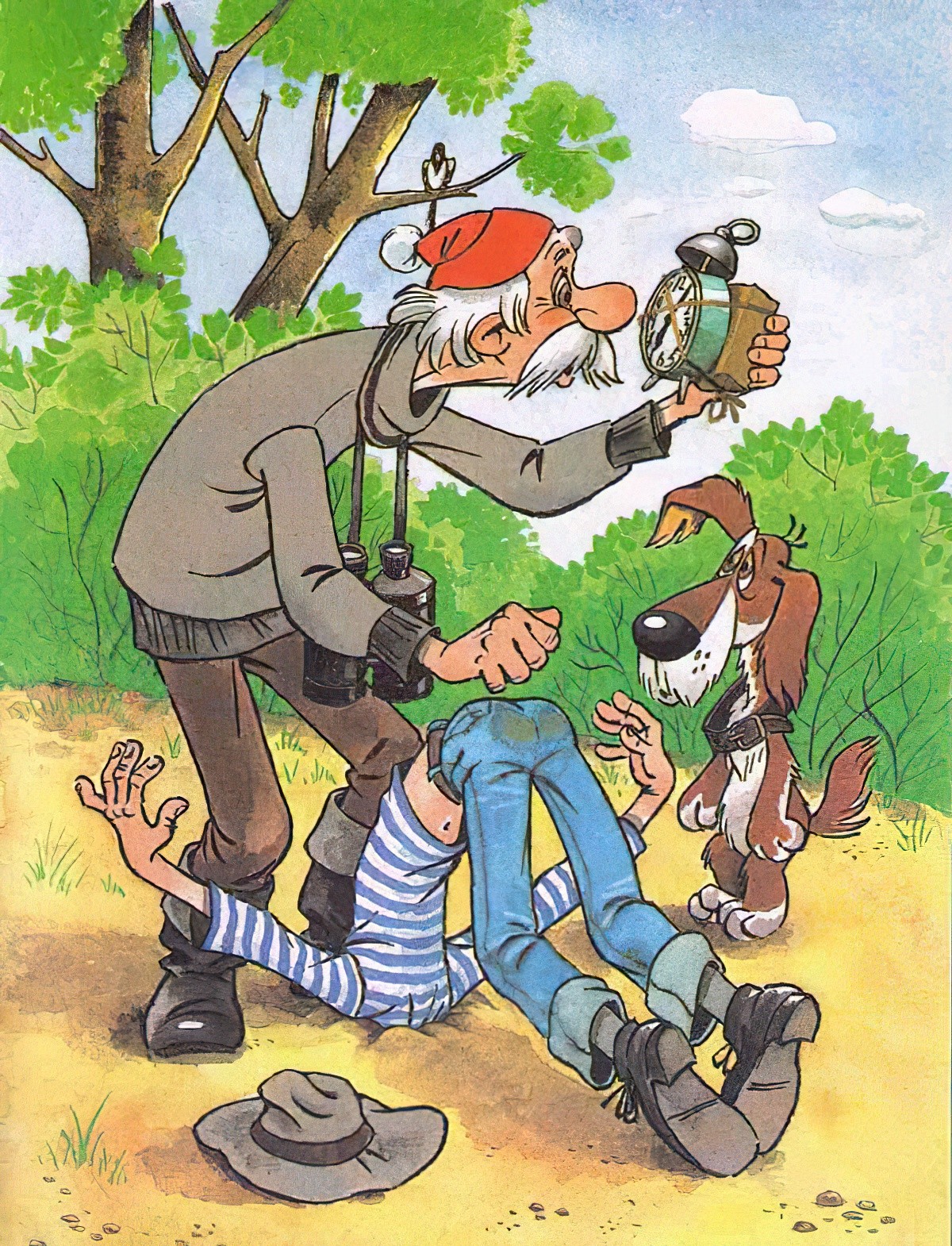

The paper hat in the role playing game below is important to the scenario. Without a fancy hat it’s difficult to imagine one’s own importance.

Kate Greenaway was a prolific and pre-eminent English Children’s Book Illustrator throughout the Victorian Era. This is a case in which reality mimics ‘fiction’.

A ‘High End’ London Children’s Clothing Store stocked Kate Greenaway’s designs. These fashion items were copied from her book illustrations. Upper class Victorian mothers adorned their children in Kate Greenaway’s Designs.

Hats As Identity

Hats As Indication Of Civility

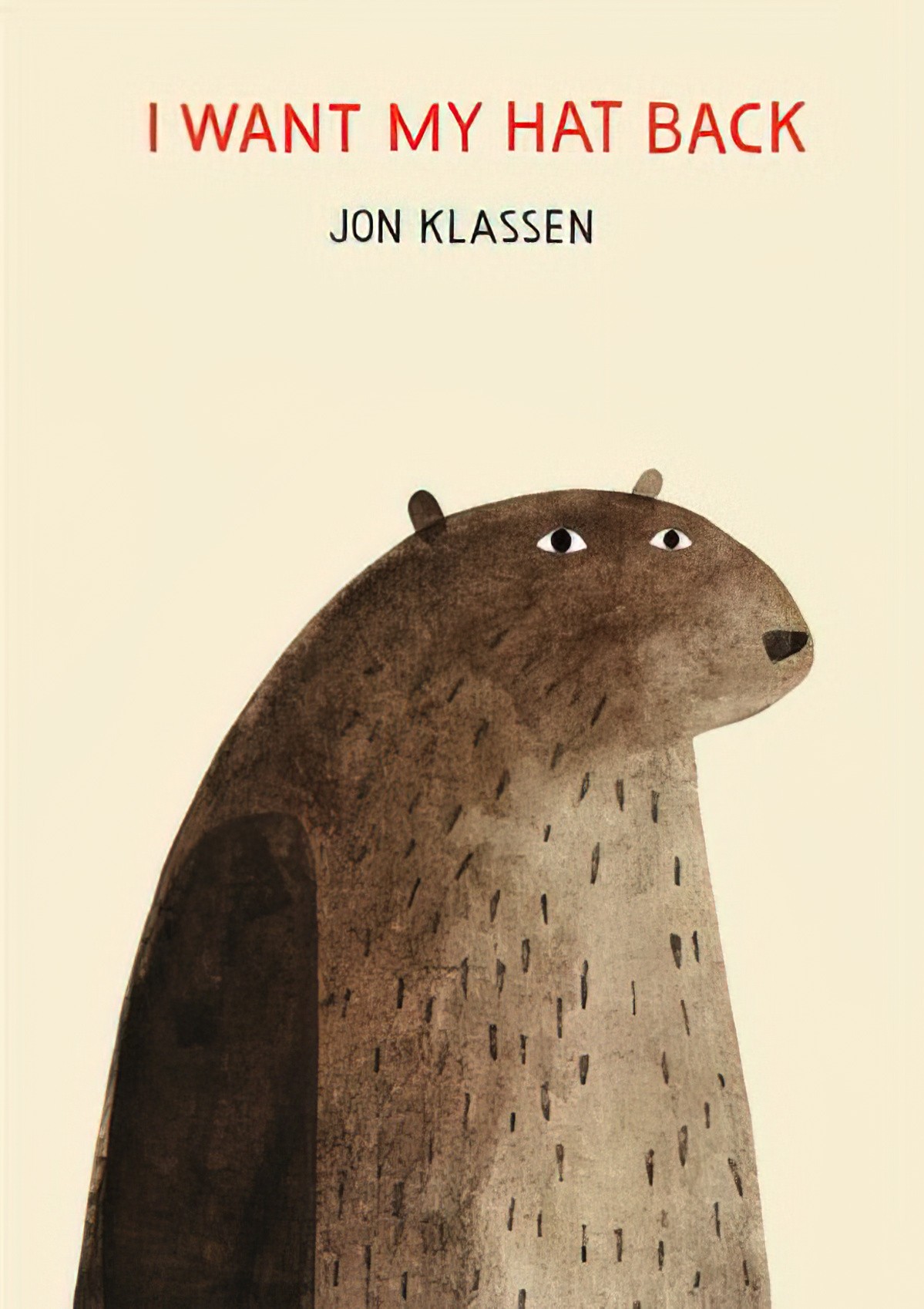

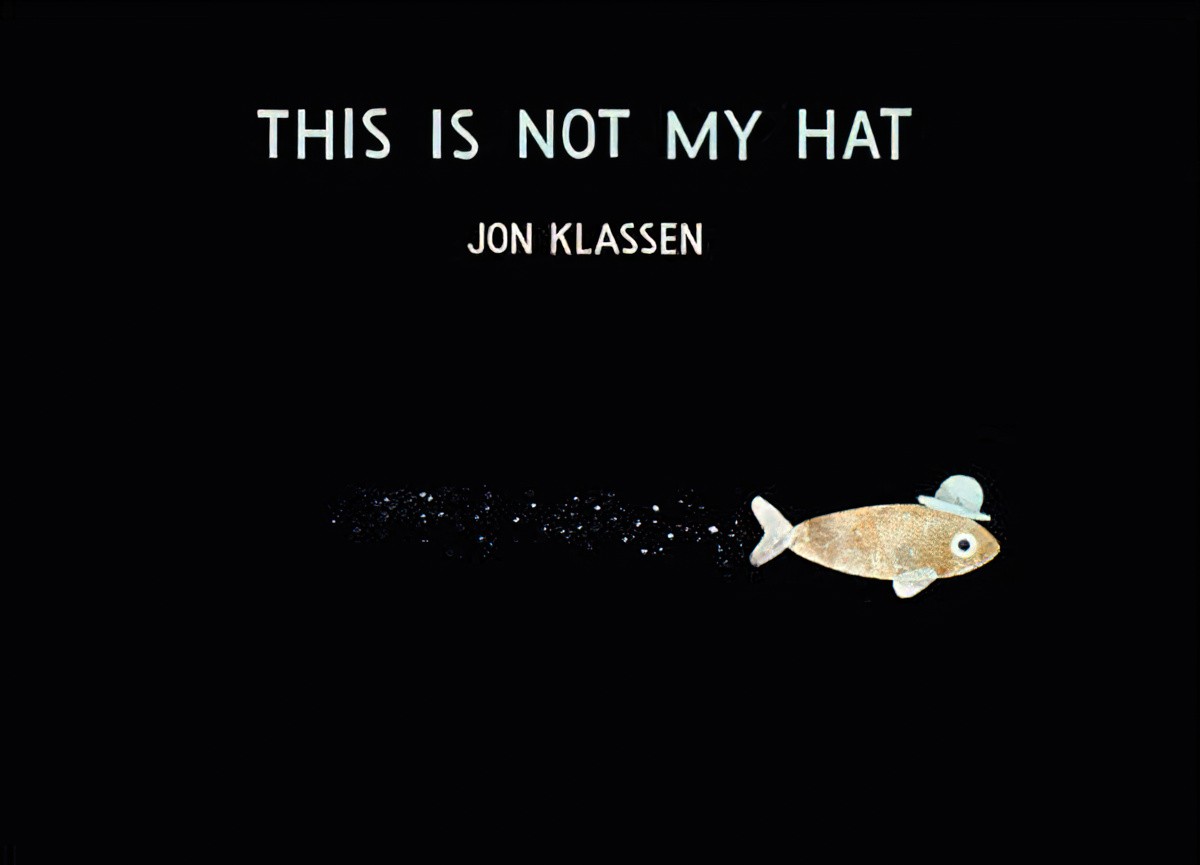

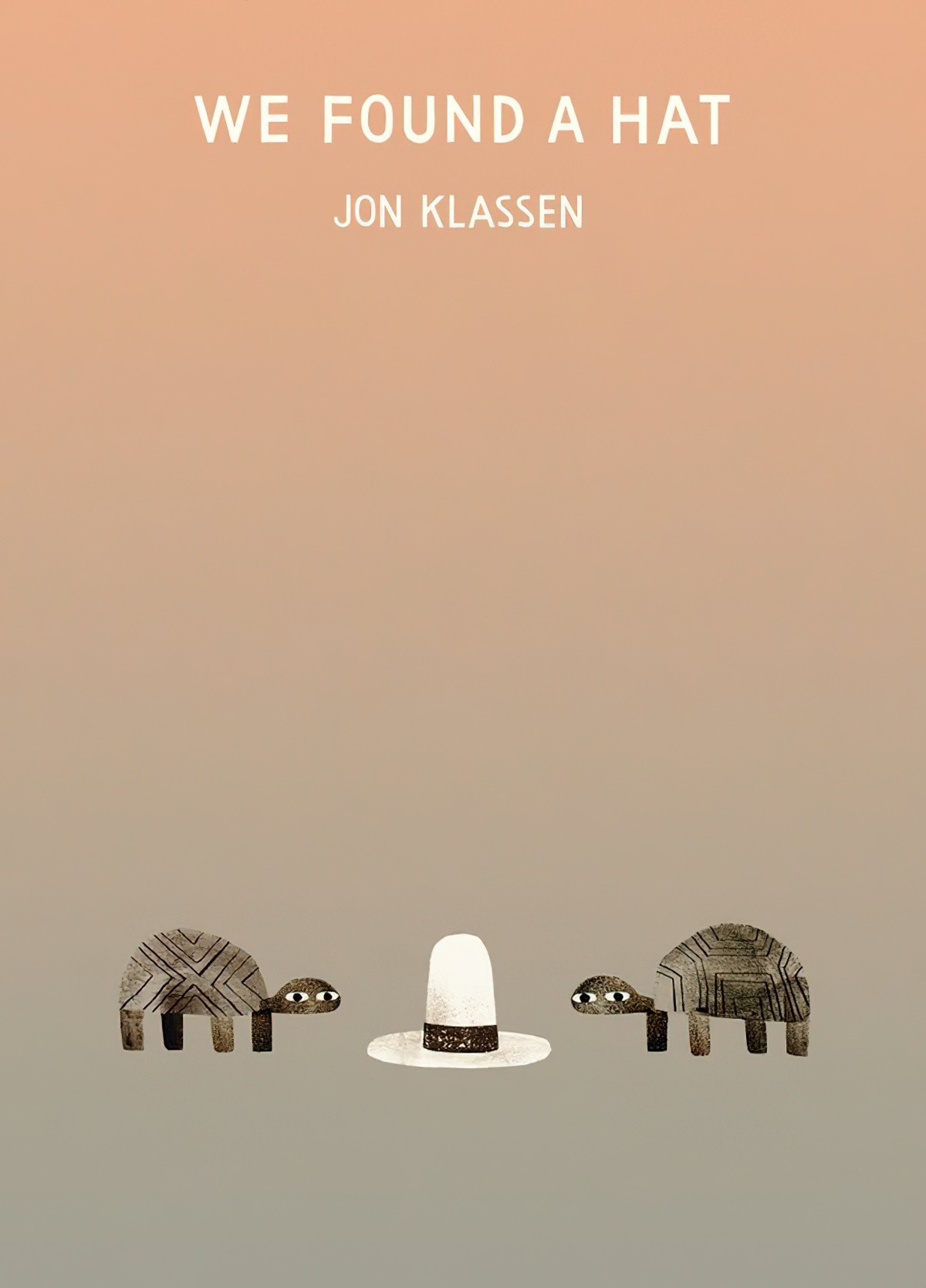

When Jon Klassen created his hat series of picture books, he was making use of the idea that when someone puts on a hat, they become better people, emphasis on ‘people’. His characters are animals. When they put on a hat they become more important. Two tortoises both want a hat. A fish steals a hat. A bear can’t find his hat and this is a tragedy.

By putting on hats, humans likewise metamorphose from base, animalistic creatures into civilised human beings.

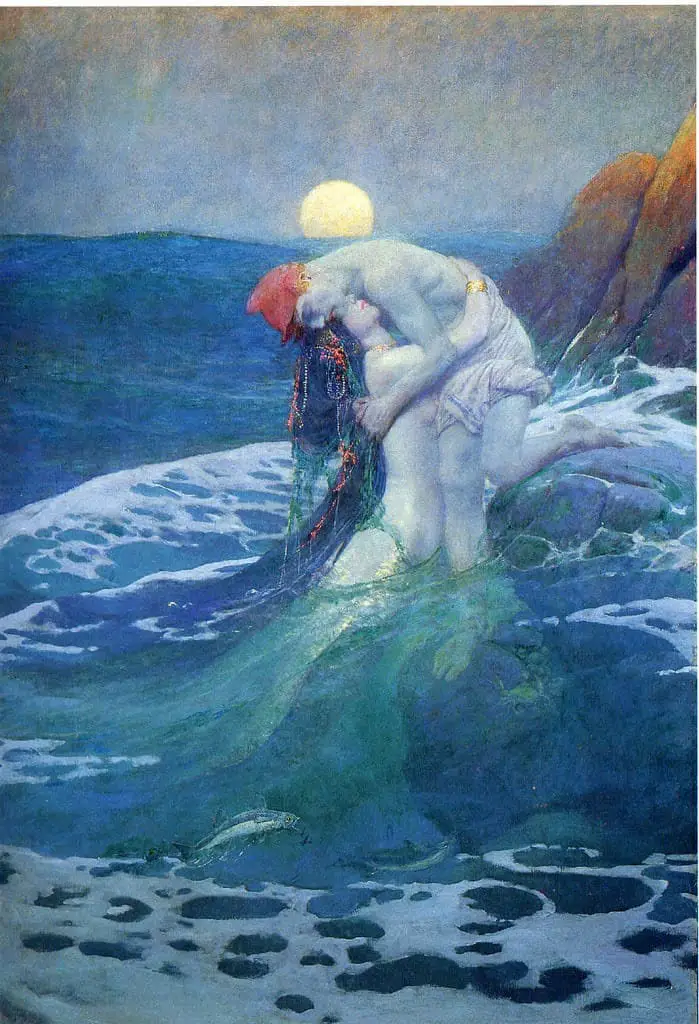

The painting below shocked its turn of the century audience not really because the woman wears no clothes, but because of the combo: She is wearing no clothes EXCEPT a hat. At the time this felt especially shocking, because hats were almost sacred. Hats were a marker of respectability. You’d not leave the house without one. When a naked person wears only a hat, they are thereby emphasising their nakedness. They are more naked than before. In fact, the painting below was so shocking, it wasn’t viewed by the public for another 40 years:

Wilson Steer, one of the most impressionist of British painters, posed his nudes in everyday settings, and here the model is playfully trying on a hat she has found in the studio. Steer did not exhibit this sketch, and it was chosen for the Tate Gallery directly from his studio in 1941, by the then Director Sir John Rothenstein. Steer told him ‘friends told me it was spoiled by the hat; they thought it indecent that a nude should be wearing a hat, so it’s never been shown’.

Gallery label at The Tate, February 2016

Removing One’s Hat As Etiquette

Hats can be utilised to mark deference. A man might tip his hat in greeting. As another form of respect, he takes it off when entering a room. Women’s hats are decorative in function and decorative hats are not designed to be easily removed.

Hats for women typically look quite different from hats for men. Hats are therefore binary gender markers before they are anything else.

The Smurf Hat

Why are smurf hats shaped like that? This is technically called a Phrygian cap and people have been wearing versions of this hat for at least 2000 years. King Midas wore a Smurf hat.

The Phrygians lived in a kingdom in the west central part of Anatolia, in what is now Asian Turkey, centred on the Sangarios River. Their language and culture was extinct by the 6th century CE.

Hats as Symbols of Freedom

The Phyrgian cap later became known as a Freedom Cap. This happened as a result of the American Revolution and then the French Revolution. That wasn’t the original association with Phrygian caps.

In Ancient Rome hats were also a symbol of freedom beacuse slaves never wore one.

Hats as Symbols of Oppression

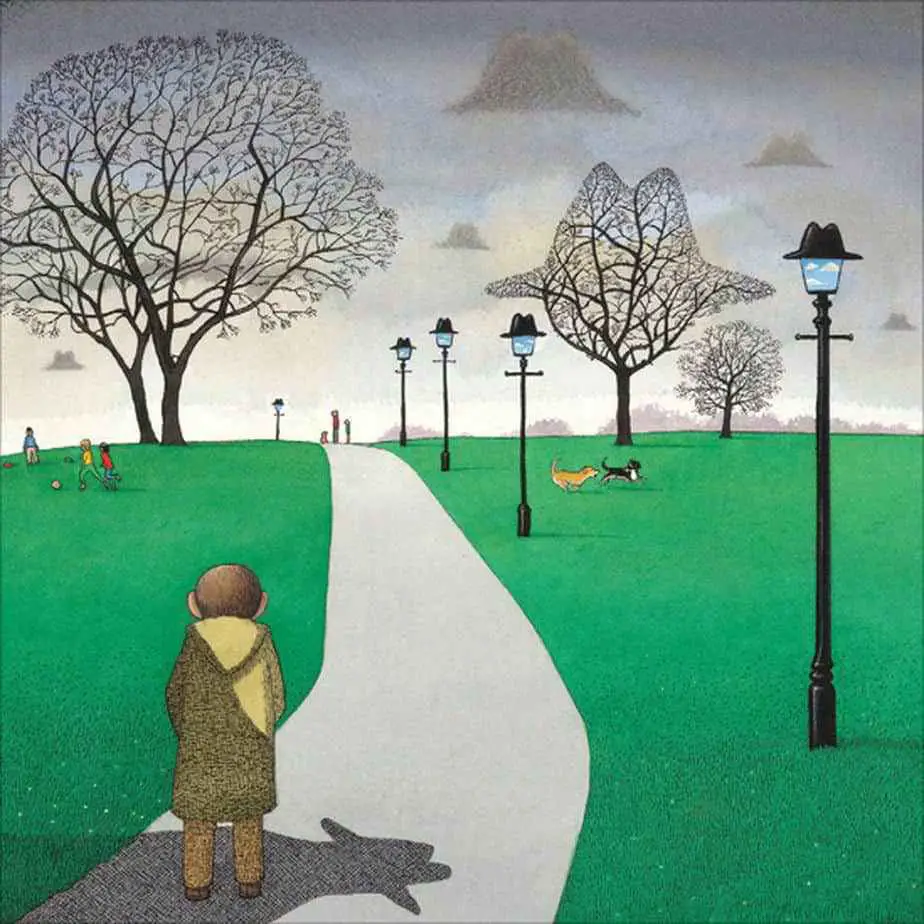

The picturebook Voices In The Park by Anthony Browne uses the surreal imagery of a bowler hat to symbolise opressive patriarchy for the boy. Hats can be symbols of liberty or oppression, depending the history of who has been wearing them.

The fedora is a modern version of the bowler which is an evolution on the top hats of aristocracy: At the end of the 19th century, gentlemen gradually swapped their top hats for bowlers.

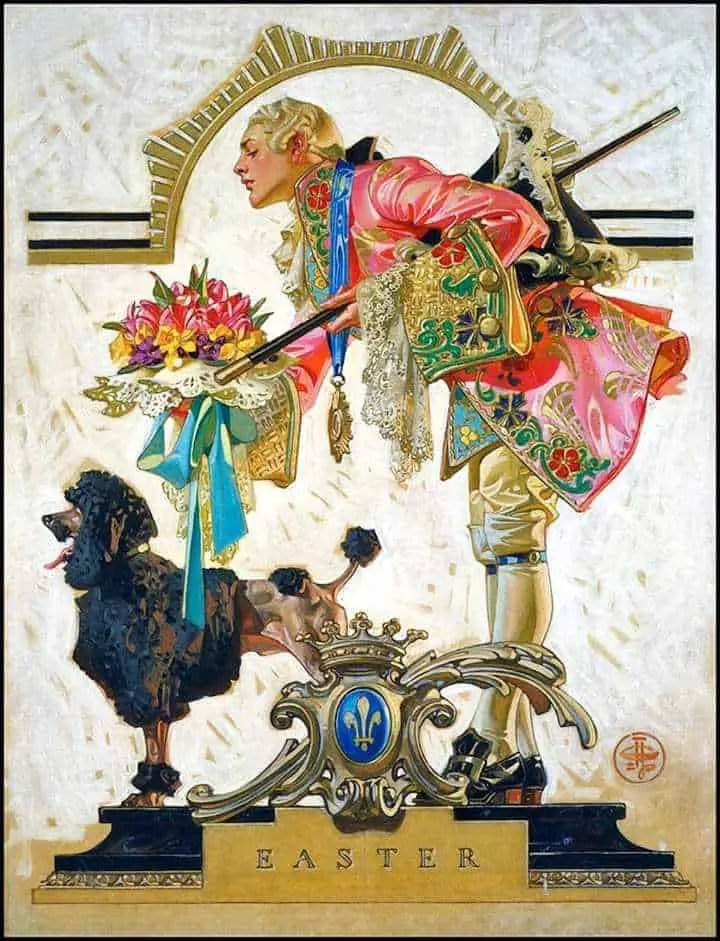

The Easter Bonnet

The Easter bonnet actually originated as a European tradition. People would wear new clothes and hats to celebrate the coming of spring and meaning of Easter. Spring and Easter signal new life and rebirth. Getting a new outfit and hat was one way to honor that meaning. The first bonnets were circles of leaves and flowers to show the cycle of the seasons. It was also a time when many people attended church a few days in a row for Easter, and a time to see who was wearing the latest fashions.

Forsyth Family Magazine

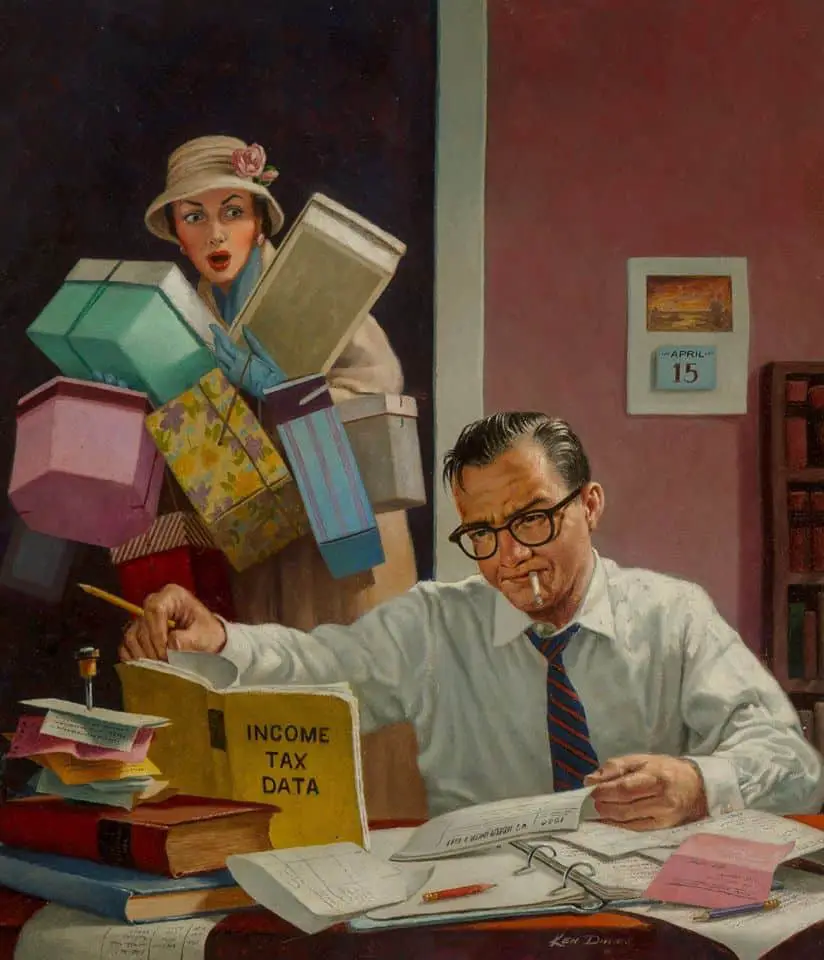

Hat As Symbol Of Wasteful Female Frippery

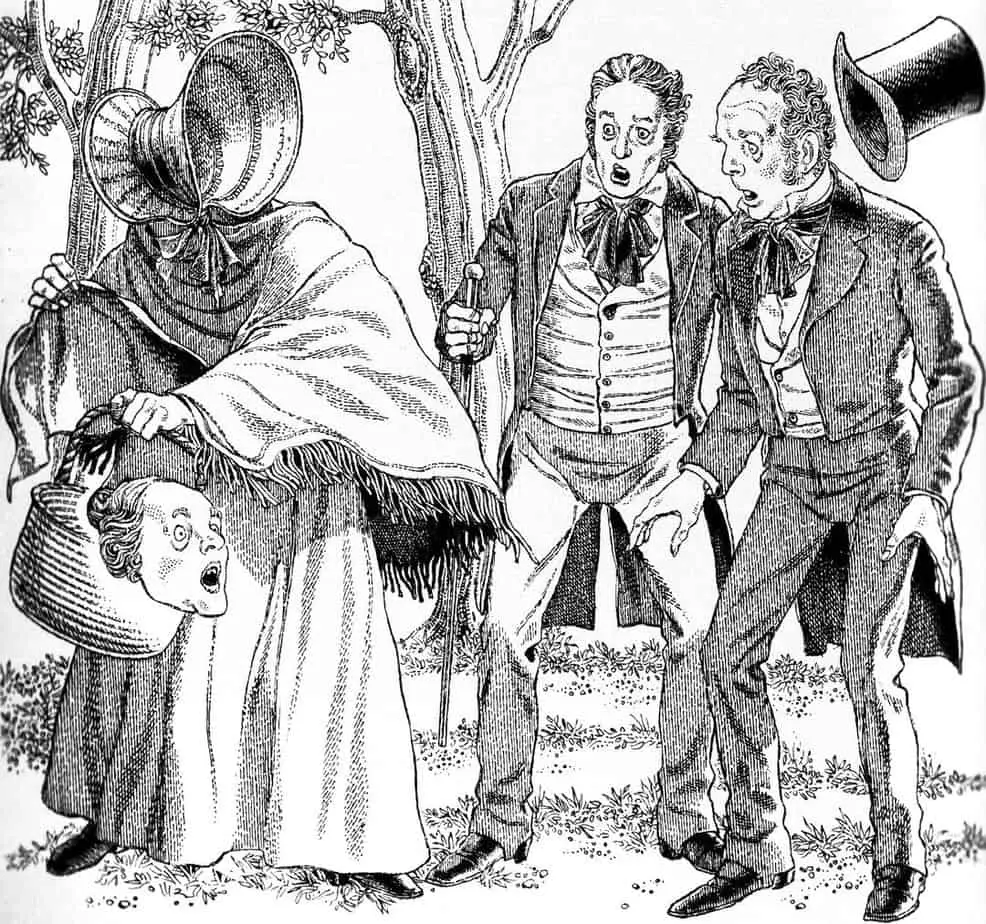

The ‘joke’ in the illustration above suggests the wife has indirectly killed her husband by overwork. The massive and ostentatious hats worn by the women signal to the viewer that they have been wasting the man’s hard-earned money on vain and unnecessary things.

This illustration appeared in an age where women were not permitted credit cards, mortgages equal pay or jobs after marriage. Look out for hats as symbols of feminine ‘leeches’ off their hard done-by husbands in older illustrations and advertisements. It’s common.

Related to this is the idea that women are so vain they would each be mortified if the women could see each other wearing the same hat (thus driving the excessive purchasing). Dealt with humorously in the illustration below:

CHILDREN’S STORIES FEATURING HATS

Because of their link with play and status, hats are of course a popular motif across children’s stories, especially carnivalesque children’s stories, which exist for the child to have fun.

THE COMIC BOOK CONVENTION OF A HAT FLYING OFF

SEE ALSO

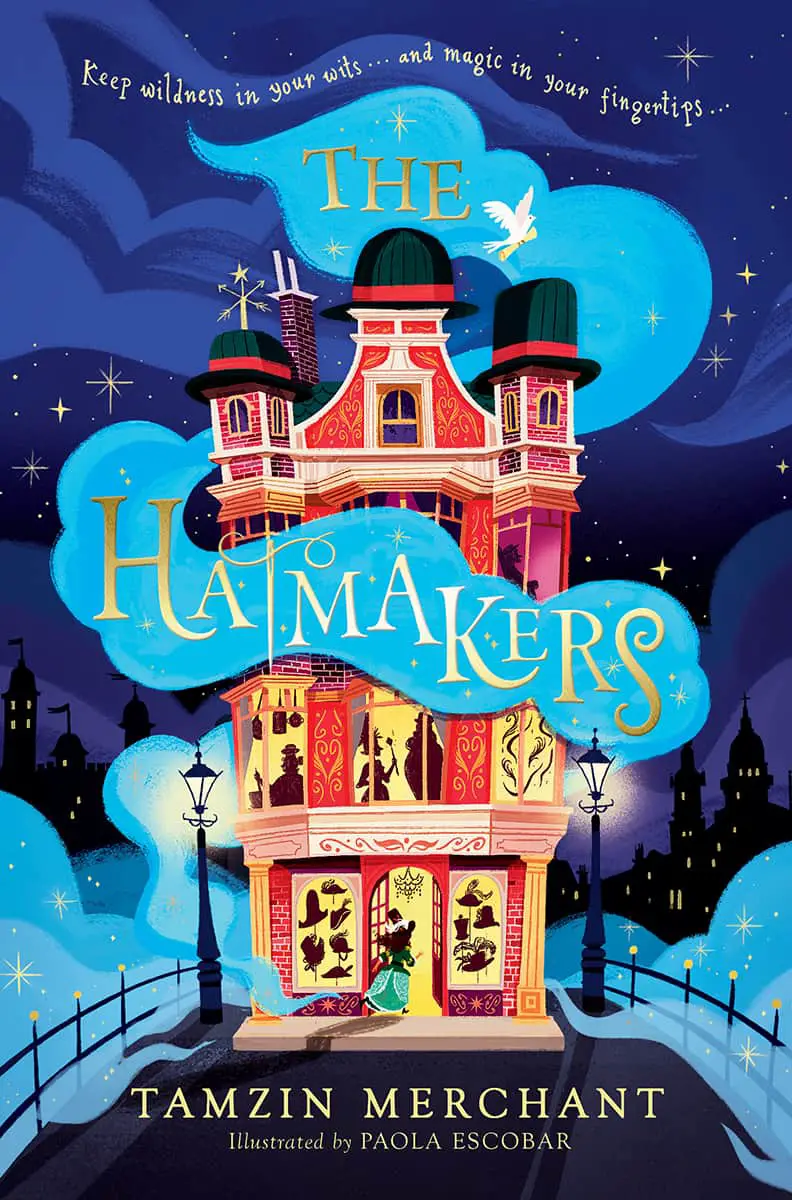

Cordelia comes from a long line of magical milliners, who weave alchemy and enchantment into every hat. In Cordelia’s world, Making – crafting items such as hats, cloaks, watches, boots and gloves from magical ingredients – is a rare and ancient skill, and only a few special Maker families remain.

When Cordelia’s father Prospero and his ship, the Jolly Bonnet, are lost at sea during a mission to collect hat ingredients, Cordelia is determined to find him. But Uncle Tiberius and Aunt Ariadne have no time to help the littlest Hatmaker, for an ancient rivalry between the Maker families is threatening to surface. Worse, someone seems to be using Maker magic to start a war.

It’s up to Cordelia to find out who, and why . . .

Featuring illustrations by Paola Escobar.

Silk snatchers: Thieves who snatch hoods or bonnets from persons walking in the streets (from a 1703 dictionary of slang)

Header painting: Carlton Alfred Smith – The Hat Makers 1891