Hills and valleys, cliffs, mountains — altitude in story is highly symbolic. When creating a story, remember to vary the altitude as much as you’d vary any other setting.

Something weird happens when humans position ourselves in high places. High place phenomenon is that weird urge you get to jump off a bridge.

I don’t get that, exactly. I get a strange variation on that. I remember standing on a bridge one time holding a tennis ball. I wondered how hard it would be to get the tennis ball back if I dropped it. So I dropped it, entirely without meaning to. Sure enough, it was no easy job getting the tennis ball back.

In London I never liked standing at the front of the queue to get on a rush hour underground train. I always felt like I’d be pushed by the people behind me into the oncoming train and fall onto the tracks. Sometimes I wondered what it would be like to push someone in front of me. But don’t worry, I never tried it. And I stay right away from trains these days.

Because there’s always the tennis ball.

HILLS AND VALLEYS

A cottage atop a hill can symbolise extreme happiness.

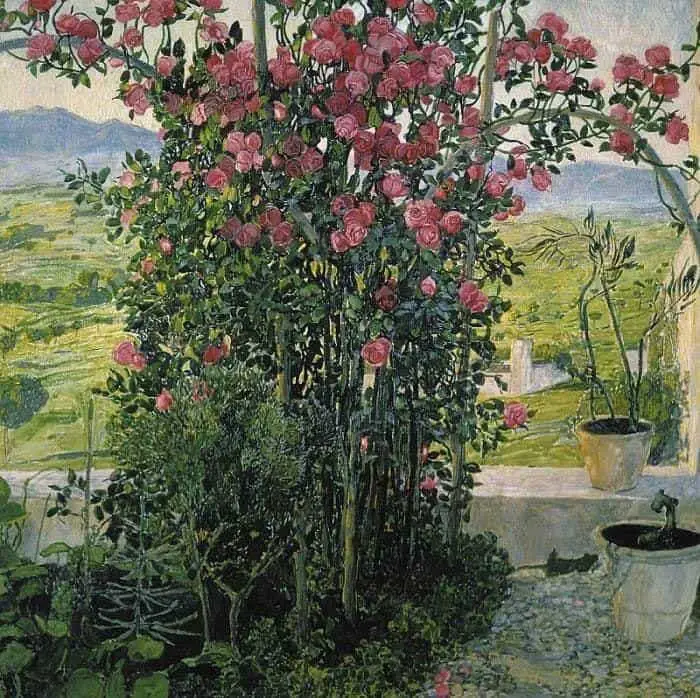

From the porch of her new house Miss Rumphius watched the sun come up; she watched it cross the heavens and sparkle on the water; and she saw it set in glory in the evening. She started a little garden among the rocks that surrounded her house, and she planted flower seeds in the stony ground. Miss Rumphius was almost perfectly happy. “But there is still one more thing I have to do,” she said. “I have to do something to make the world more beautiful.” But what? “The world already is pretty nice,” she thought, looking out over the ocean.

Miss Rumphius by Barbara Cooney

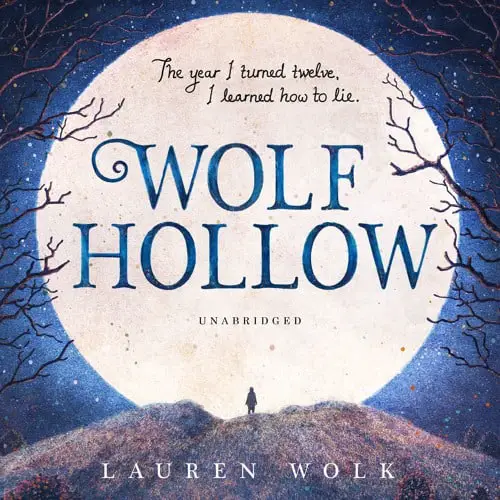

Growing up in the shadows cast by two world wars, Annabelle has lived a mostly quiet, steady life in her small Pennsylvania town. Until the day new student Betty Glengarry walks into her class. Betty quickly reveals herself to be cruel and manipulative, and while her bullying seems isolated at first, things quickly escalate, and reclusive World War I veteran Toby becomes a target of her attacks. While others have always seen Toby’s strangeness, Annabelle knows only kindness. She will soon need to find the courage to stand as a lone voice of justice as tensions mount.

Wolf Hollow is an interesting setting because it is an snail under the leaf setting. ‘Hollow’ is a poetic sounding name (as the creators of Stars Hollow surely recognise). While dips in the landscape generally indicate evil (basements are scary, valleys attract mysterious fog and harbour secrets), ‘hollows’ are metaphorically similar to islands, sheltered from the evils of the outside world. That’s why ‘Hollow’ is such a great choice for this book — it is in many ways a utopian setting (sheltered from the World War going on elsewhere) but also a terrible place, with its inhabitants dangerously bigoted.

Hills and valleys have a logic of their own. Why did Jack and Jill go up the hill? Sure, sure, a pail of water, probably orders from a parent. But wasn’t the real reason so Jack could break his crown and Jill come tumbling after That’s what it usually is in literature. Who’s up and who’s down? Just what do up and down mean?

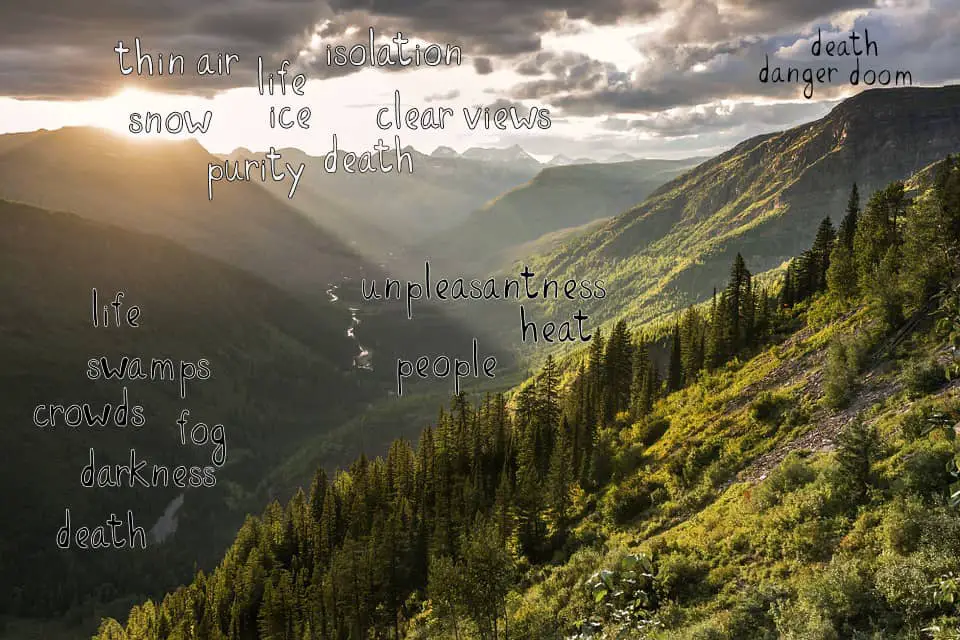

First, think about what there is down low or up high. Low: swamps, crowds, fog, darkness, fields, heat, unpleasantness, people, life, death.High: snow, ice, purity, thin air, clear views, isolation, life, death. Some of these, you will notice, appear on both lists, and you can make either environment work for you.

Thomas C. Foster, How To Read Literature Like A Professor

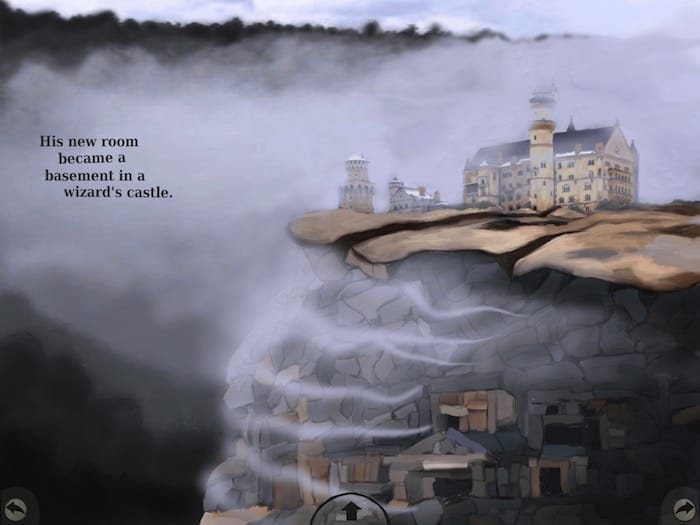

In storybook illustrations, it’s very common to find a house on a hill. A house on a hill is a safe house — from here you won’t be susceptible to flooding, and you can see enemies approaching. A house on a hill might also be close to the sea, but protected from it by the slight altitude.

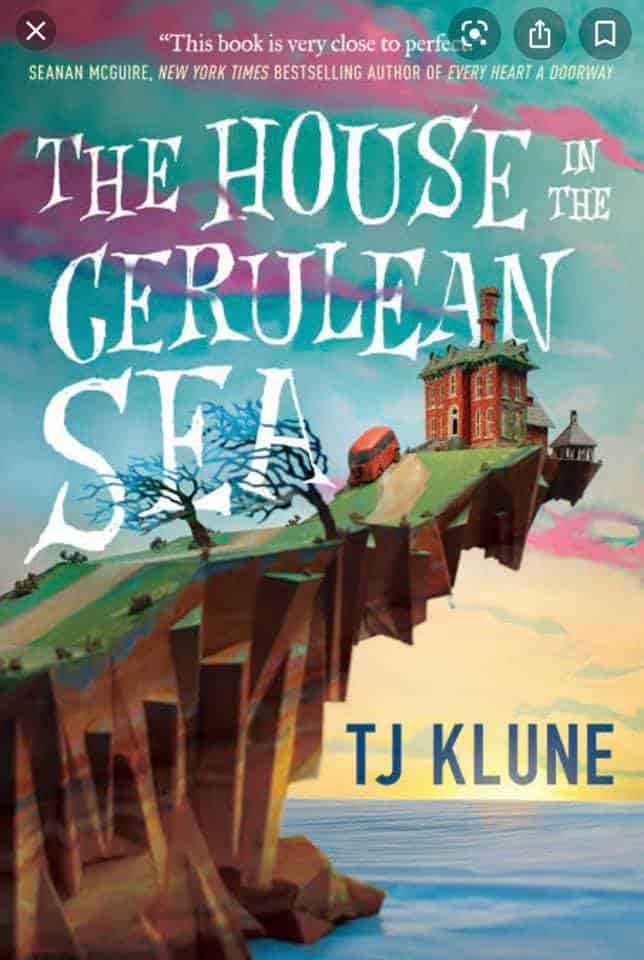

A magical island. A dangerous task. A burning secret.

Linus Baker leads a quiet, solitary life. At forty, he lives in a tiny house with a devious cat and his old records. As a Case Worker at the Department in Charge Of Magical Youth, he spends his days overseeing the well-being of children in government-sanctioned orphanages.

When Linus is unexpectedly summoned by Extremely Upper Management he’s given a curious and highly classified assignment: travel to Marsyas Island Orphanage, where six dangerous children reside: a gnome, a sprite, a wyvern, an unidentifiable green blob, a were-Pomeranian, and the Antichrist. Linus must set aside his fears and determine whether or not they’re likely to bring about the end of days.

But the children aren’t the only secret the island keeps. Their caretaker is the charming and enigmatic Arthur Parnassus, who will do anything to keep his wards safe. As Arthur and Linus grow closer, long-held secrets are exposed, and Linus must make a choice: destroy a home or watch the world burn.

The House in the Cerulean Sea is about the profound experience of discovering an unlikely family in an unexpected place—and realizing that family is yours.

MOUNTAINS

At the beginning, mountaineering was an equal field. Things changed when Victorian social etiquette became stricter & mountains became masculine spaces. Biases in publishing meant that we lost the women’s voices and inherited a male-canon of mountain literature.

A Twitter thread by Anna Fleming (@annamfleming)

Anna Fleming references an article called The surprising origins of women’s mountaineering – 1770-1830 at UK Climbing, which includes numerous examples of female pioneer mountaineers.

In the valley of Fruitless Mountain, a young girl named Minli spends her days working hard in the fields and her nights listening to her father spin fantastic tales about the Jade Dragon and the Old Man of the Moon.

Minli’s mother, tired of their poor life, chides him for filling her head with nonsense. But Minli believes these enchanting stories and embarks on an extraordinary journey to find the Old Man of the Moon and ask him how her family can change their fortune.

She encounters an assorted cast of characters and magical creatures along the way, including a dragon who accompanies her on her quest.

M.C. Higgins the Great is set in Kentucky on a fictitious mountain in the Appalachians, in an area recently strip-mined for coal.

Mayo Cornelius Higgins sits on his gleaming, forty-foot steel pole, towering over his home on Sarah’s Mountain. Stretched before him are rolling hills and shady valleys. But behind him lie the wounds of strip mining, including a mountain of rubble that may one day fall and bury his home. M.C. dreams of escape for himself and his family. And, one day, atop his pole, he thinks he sees it—two strangers are making their way toward Sarah’s Mountain. One has the ability to make M.C.’s mother famous. And the other has the kind of freedom that M.C. has never even considered.

Mountains are somewhat cliched as ‘the land of greatness’ in stories but they are still used a whole heap and the symbolism still works.

In the 1997 film Contact, for instance, the Jody Foster character sits on a high piece of land when she has her anagnorises.

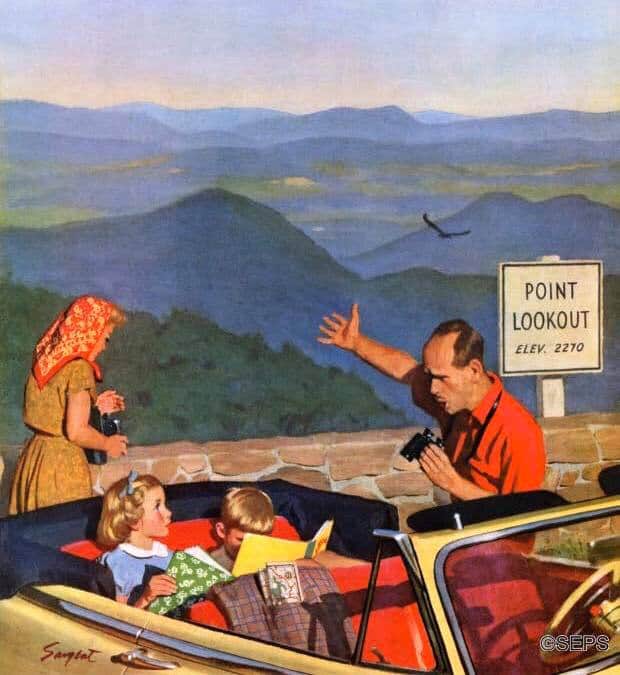

A character often has a revelation in a high place (mountain, hill, knoll, rooftop… any high place will suffice).

- The Moses story (the ur-mountain-story in the Christian world)

- Greek myths about gods on Mt Olympus

- Brokeback Mountain

- Heidi

- Cold Mountain

- The Shining

- The Bears On Hemlock Mountain

- Serena

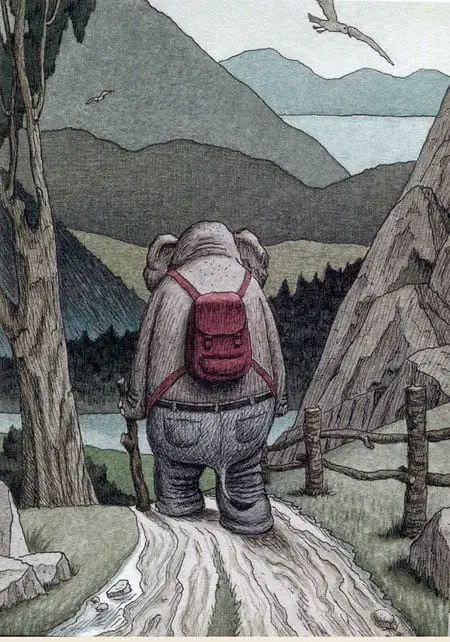

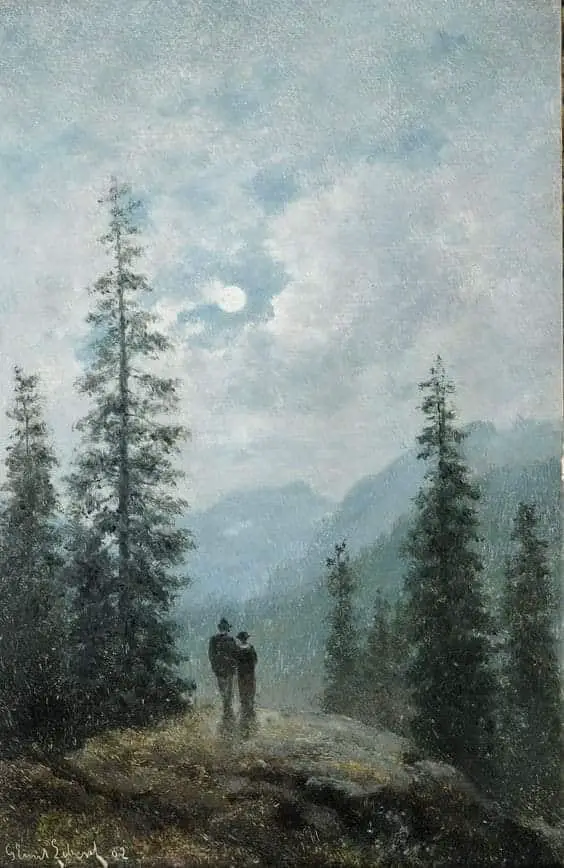

In The Remains of the Day, the butler has a high-altitude revelation early in his journey:

It was a fine feeling indeed to be standing up there like that, with the sound of summer all around one and a light breeze on one’s face. And I believe it was then, looking on that view, that I began for the first time to adopt a frame of mind appropriate for the journey before me. For it was then that I felt the first healthy flush of anticipation for the many interesting experiences I know these days ahead hold in store for me. And indeed, it was then that I felt a new resolve not to be daunted in respect to the one professional task I have entrusted myself with on this trip; that is to say, regarding Miss Kenton and our present staffing problems.

The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro

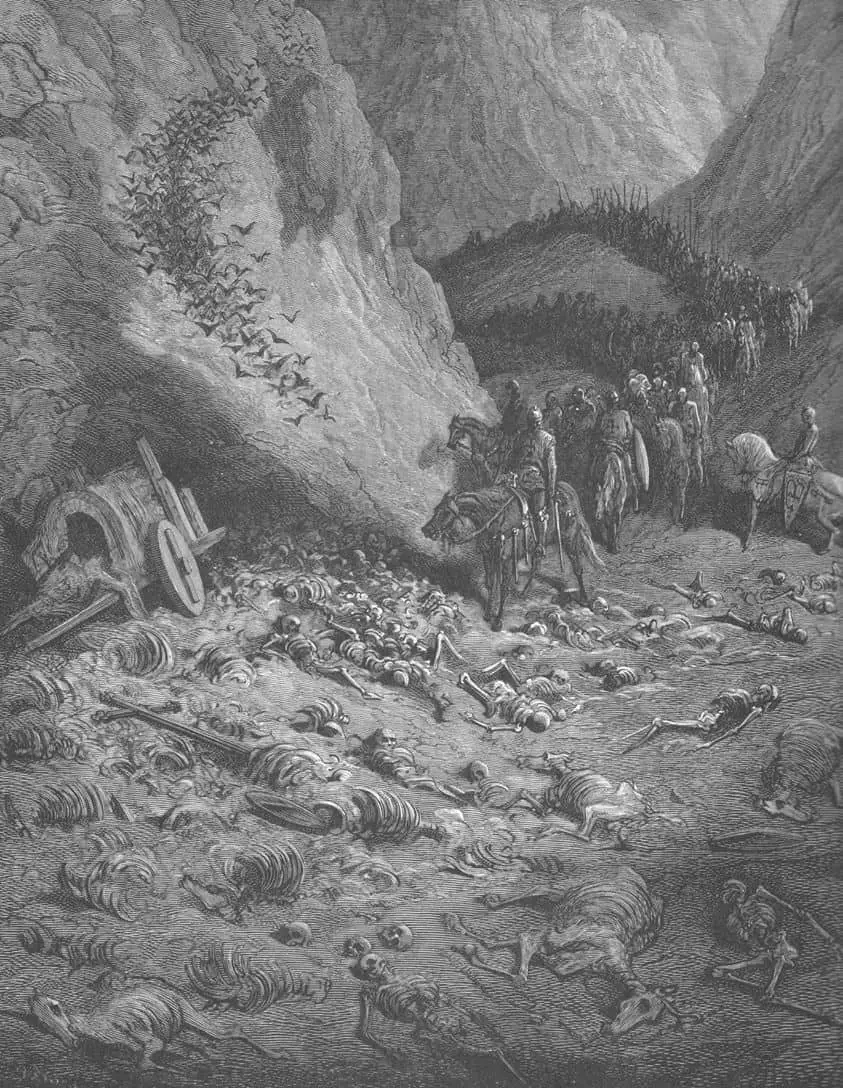

An ecoGothic Everest is arguably a contemporary phenomenon, a lived experience, where human perceptions of the mountain as both monstrous and desirable are enacted through its commodified and environmentally unstable condition. Climate-change induced alterations on Everest are exacerbated by commercialism: melting glaciers, thickening air, and corrupted waters as corpses and human waste litter the mountainside.

Meanwhile, there are accusations that Dark Tourism has found a home on the crowning peak of ‘the roof of the world,’ as would-be summiteers photograph bodies acting as route-markers, and droves of hopefuls pay large sums to swarm upon the slopes in their summit bids, regardless of numerous fatal tragedies fuelling the criticism of ‘bagging’ this most prestigious of peaks.

Despite the contemporary nature of the ecoGothic on Everest, its manifestation is born out of a historical literary imagination which created the iconography of the Gothic mountain, alongside the rise of mountaineering and its accompanying literature. This article considers how the Gothic aesthetic has influenced mountaineering and in fact contributed to the creation and maintenance of an ecoGothic Everest.

The Gothic terror of Everest today is not generated primarily through fictional reimaginings of the untameable wilderness, but through encountering the human-made degradation of the peak, consolidating the mountain as a site of lived ecoGothic in current times. By focalising Everest through the ecoGothic, George Mallory’s famous statement of intent to summit, ‘because it is there,’ no longer seems a legitimate motivation behind so-called human mastery of the mountain.

Making Gothic Mountains: Everest and the EcoGothic

Jemma Stewart

For years, little was known about the secretive mountain community.

But this year a number of members, including children, managed to escape and began to share harrowing stories of life inside the elusive cult-like group.

“They have child marriages, they have forced labour for the children and for the adults, and they are training children to be warriors, to be soldiers of God,” Fionah Bojos, an attorney from Cebu for Human Rights who met with survivors, told the ABC.

The man they thought was the reincarnation of Jesus had promised them heaven but delivered hell.

Inside Socorro Bayanihan Services Inc, the alleged doomsday cult under investigation in the Philippines, ABC, November 2023

CLIFFS

The cliff face does not have the same meaning as the beach. Cliffs are elevated areas without sand. Cliffs work quite differently in English literature.

- Cliffs in English (England) are gloomy settings

- Cliffs also exist in Australia of course, but they are most often considered dangerous e.g. the Twelve Apostles in Victoria give way to rough ocean rather than a safe beach.

The association between cliffs and peril is so strong that occasionally cliffs can be misused in drama, for instance in The River Wild.

And what about the sequences in which Strathairn cuts crosscountry, climbing mountains, fording rivers, walking faster than the river flows? Impossible, but he does it. At one point, in a scene so ludicrous I wanted to laugh aloud, he even starts a fire to send smoke signals to his wife. At another point, he clings to the side of a cliff, while we ask ourselves what earthly reason he had for climbing it. And he works wonders with his handy Swiss Army knife.

Roger Ebert’s review of The River Wild

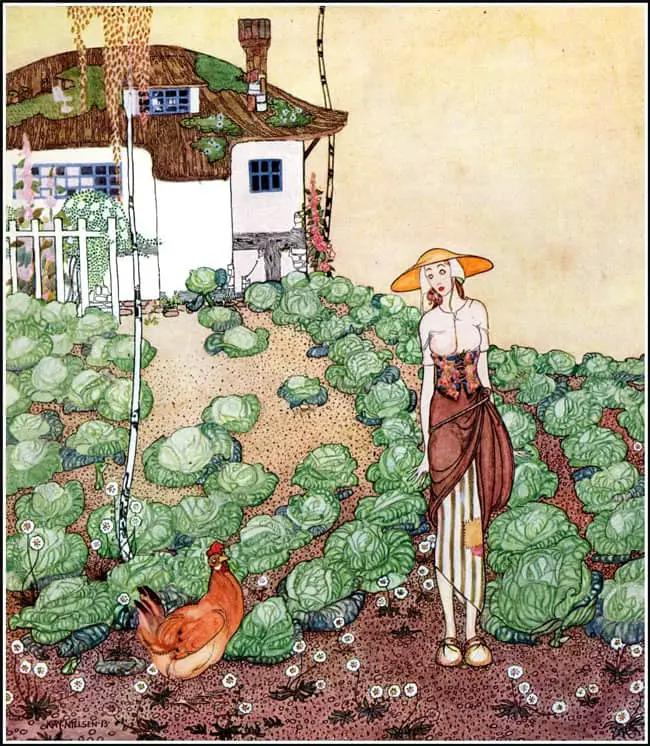

In the illustration from Beauty and the Beast below, the family has lost its fortune at sea and has had to move to a small cottage and live as peasants. They live precariously in this community, not fully accepted (except for Beauty, of course, whose beauty privilege makes up for a lot).

Cliffs are also high in altitude but they have a quite different symbolism from mountains. Cliffs are precarious.

See the Hayao Miyazaki film Ponyo for an excellent example of cliff symbolism, in which the precarious cliff is a symbol for the precarious balance of nature.

Her paintings are bursting with subjects she finds fascinating, capturing the imagination with her individual & dramatic style.

Fire and cliffs make for a wonderfully camp symbolic admixture in this Three Investigators mystery story.

For a short story collection which makes full use of altitude, set in the vertiginous landscape of Wyoming, see one of Annie Proulx’s Wyoming collections (e.g. Close Range). Proulx makes use of mixed topography and everything you find in that:

- mountains

- high desert landscapes

- canyons

- buttes (an isolated hill with steep sides and a flat top (similar to but narrower than a mesa)

- eroded outcroppings (known in North America as hoodoos)

When reading Proulx’s stories, one of the most important concepts to grasp is her ‘geographical determinism.’ This refers to the way in which the landscape has the upper hand in a game against the insignificant humans who live there, but temporarily. We know the characters are going to have tragic endings; we read the stories to find out how much of a fight they put up, and to know the exact nature of their downfall.

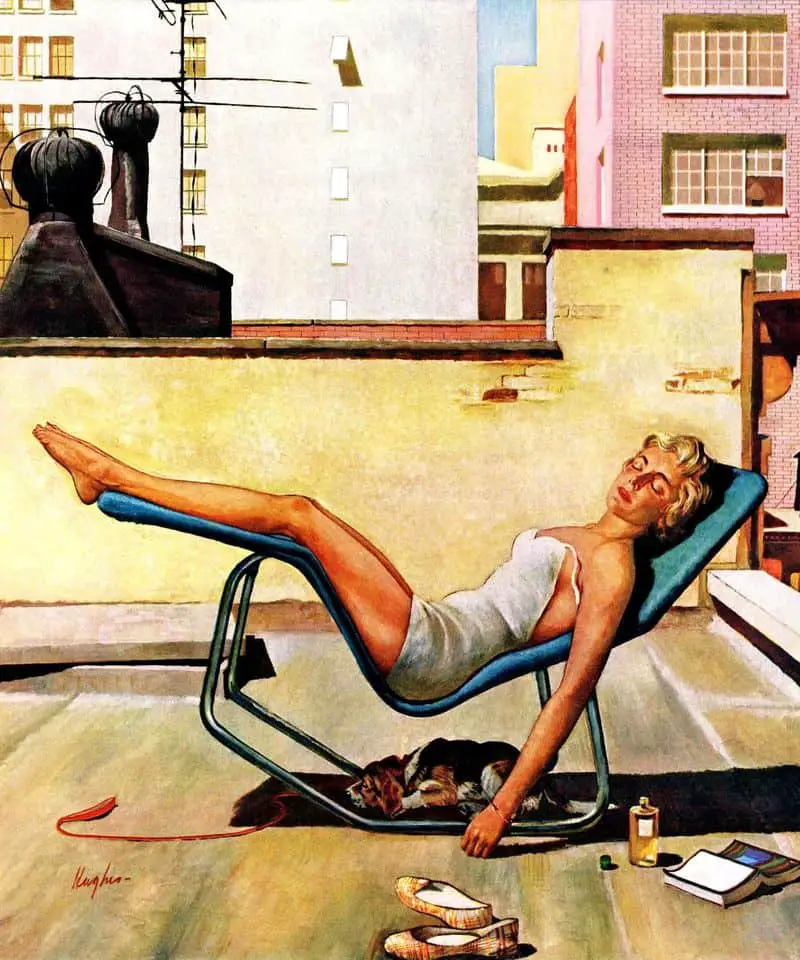

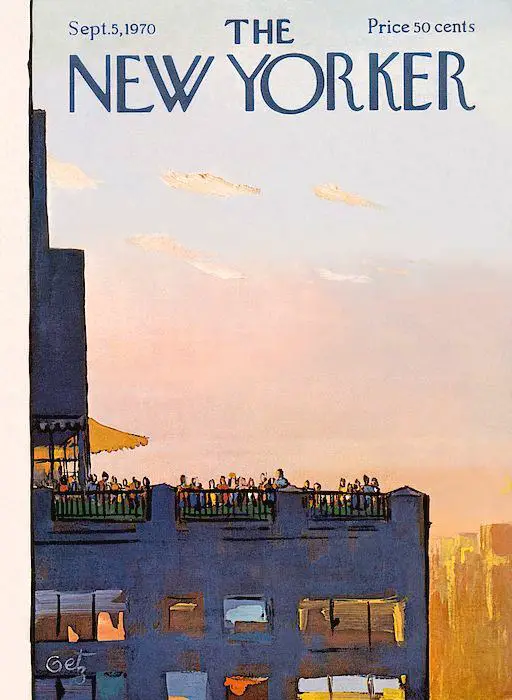

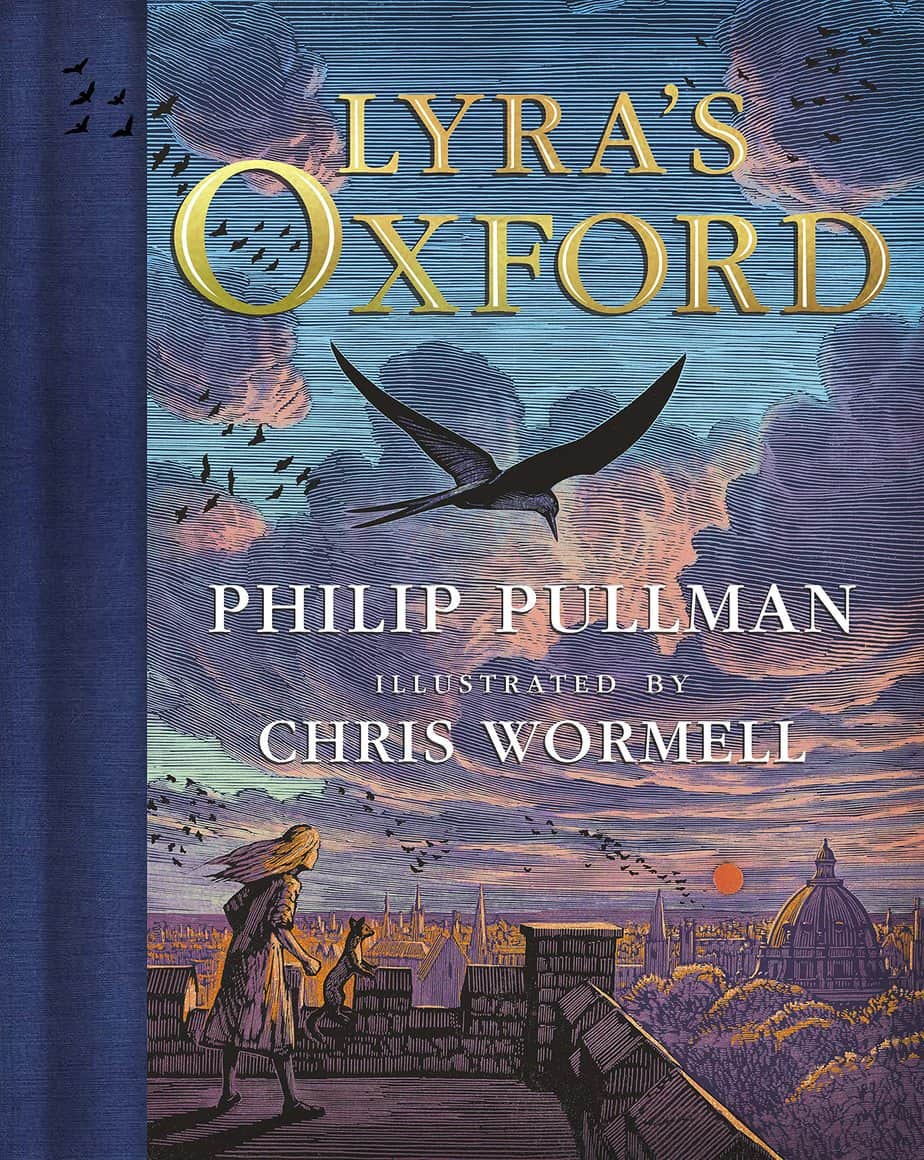

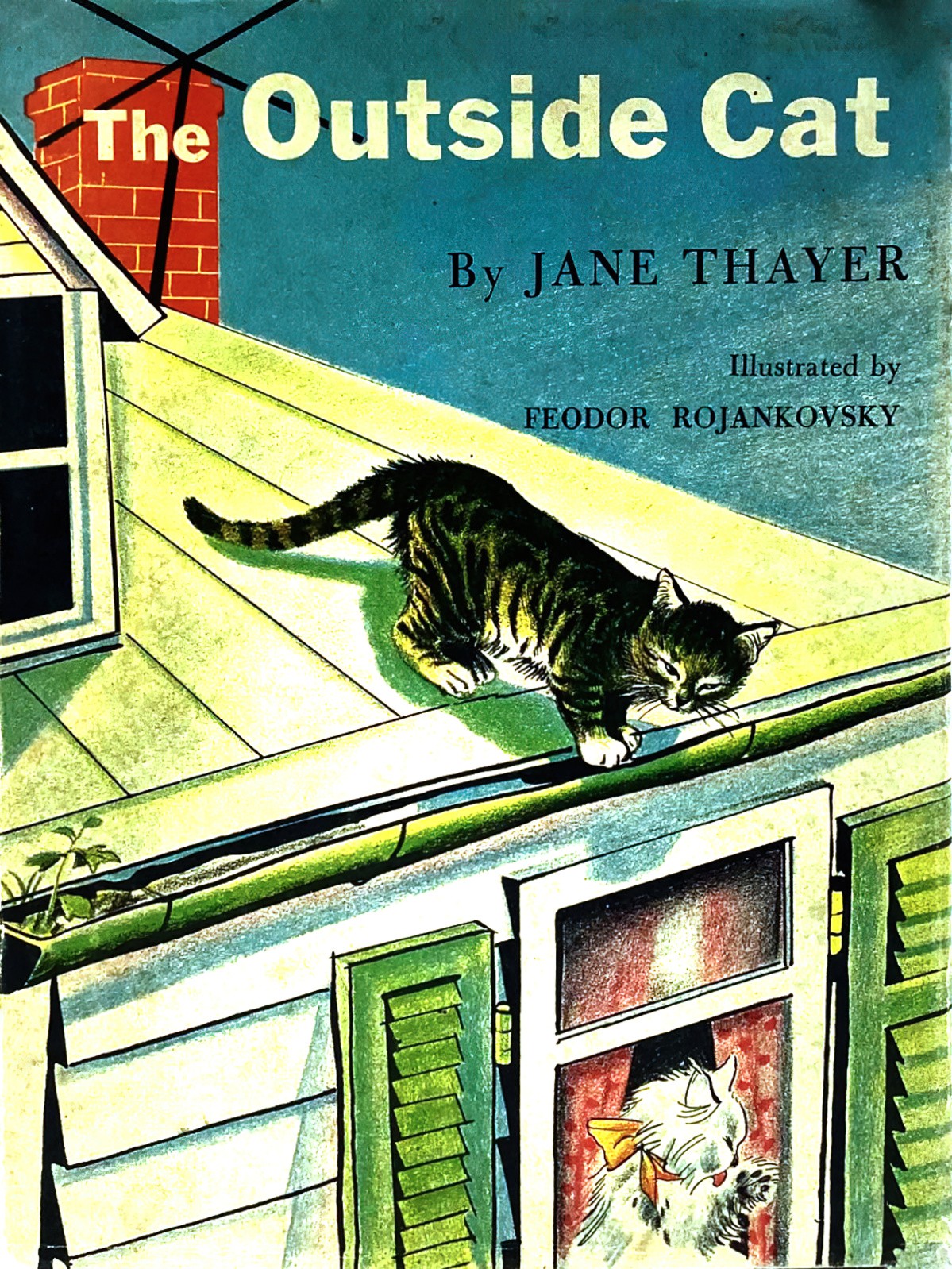

Rooftops

The manmade equivalent of a natural high place is a rooftop. Characters often experience anagnorises on rooftops, or go there to achieve an overview of a situation, and to work out a plan to achieve their desires.

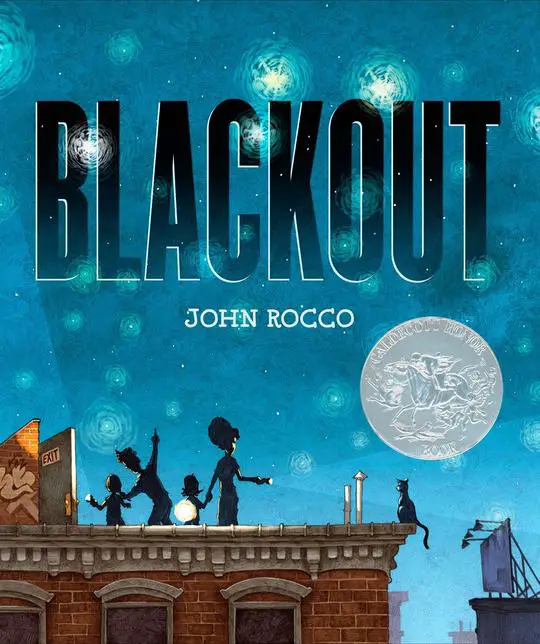

One hot summer night in the city, all the power goes out. The TV shuts off and a boy wails, “Mommm!” His sister can no longer use the phone, Mom can’t work on her computer, and Dad can’t finish cooking dinner. What’s a family to do? When they go up to the roof to escape the heat, they find the lights–in stars that can be seen for a change–and so many neighbors it’s like a block party in the sky! On the street below, people are having just as much fun–talking, rollerblading, and eating ice cream before it melts. The boy and his family enjoy being not so busy for once. They even have time to play a board game together. When the electricity is restored, everything can go back to normal . . . but not everyone likes normal. The boy switches off the lights, and out comes the board game again.

Using a combination of panels and full bleed illustrations that move from color to black-and-white and back to color, John Rocco shows that if we are willing to put our cares aside for a while, there is party potential in a summer blackout.

For the most part, Hannah’s life is just how she wants it. She has two supportive parents, she’s popular at school, and she’s been killing it at gymnastics. But when her cousin Cal moves in with her family, everything changes. Cal tells half-truths and tall tales, pranks Hannah constantly, and seems to be the reason her parents are fighting more and more. Nothing is how it used to be. She knows that Cal went through a lot after his mom died and she is trying to be patient, but most days Hannah just wishes Cal never moved in.

For his part, Cal is trying his hardest to fit in, but not everyone is as appreciative of his unique sense of humor and storytelling gifts as he is. Humor and stories might be his defense mechanism, but if Cal doesn’t let his walls down soon, he might push away the very people who are trying their best to love him.

Told in verse from the alternating perspectives of Hannah and Cal, this is a story of two cousins who are more alike than they realize and the family they both want to save.

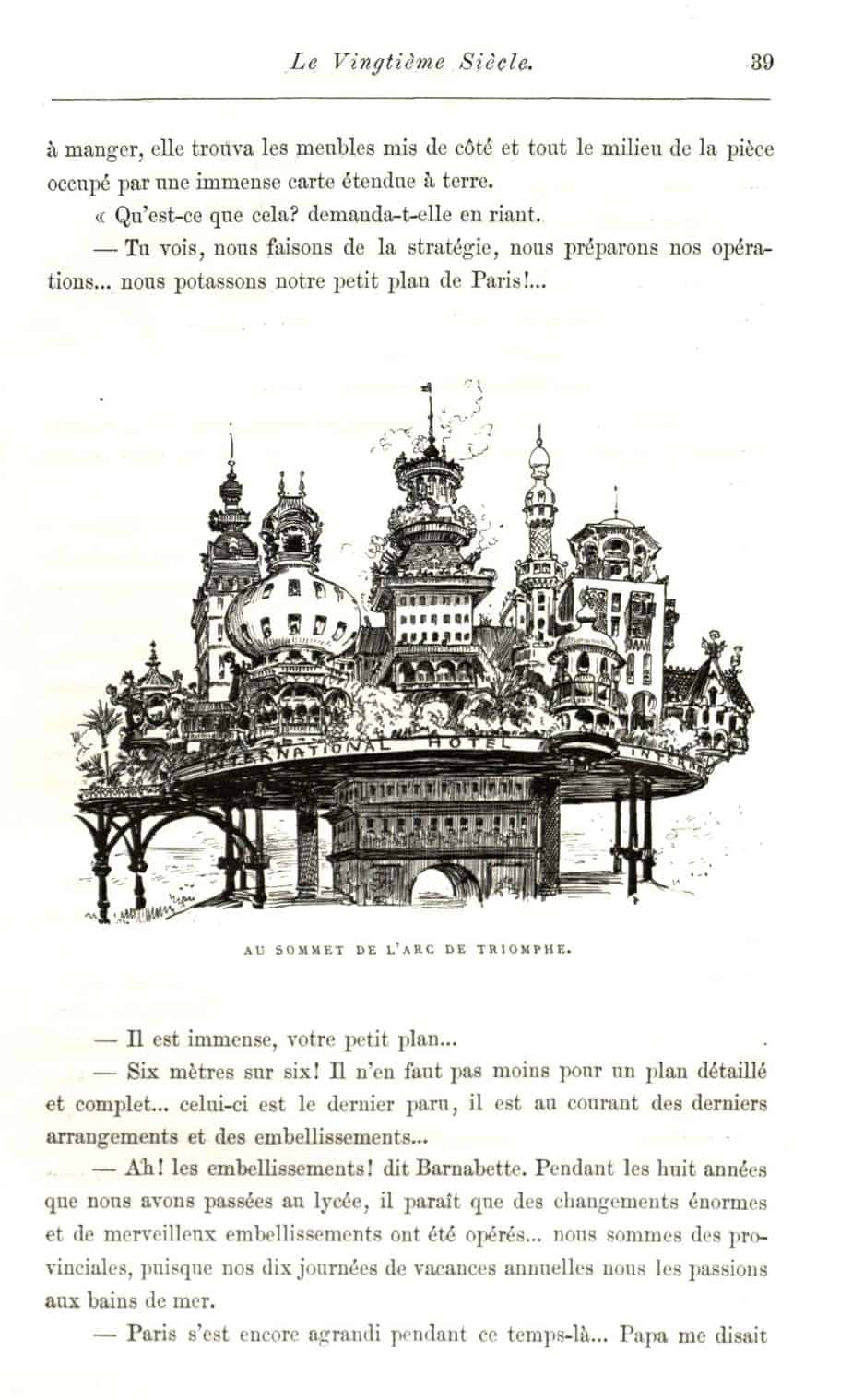

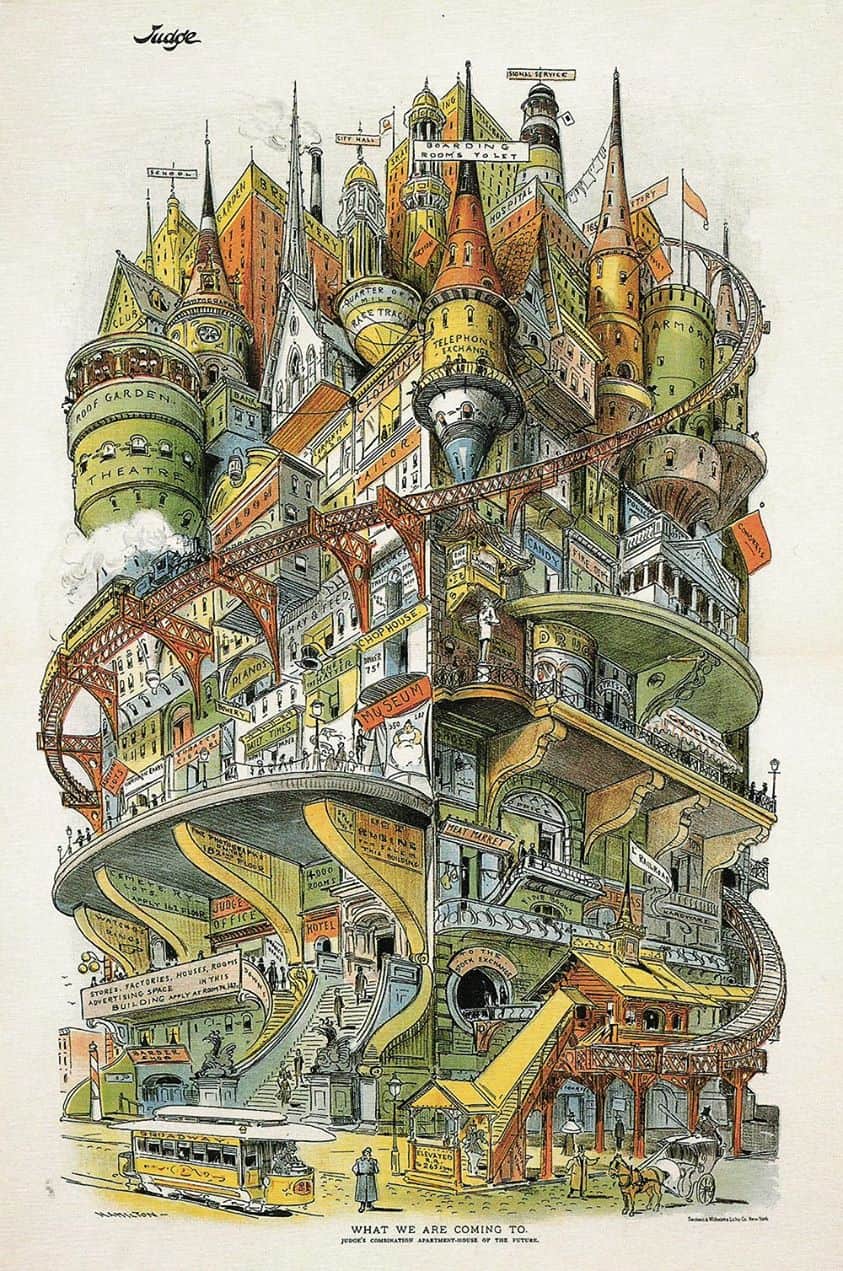

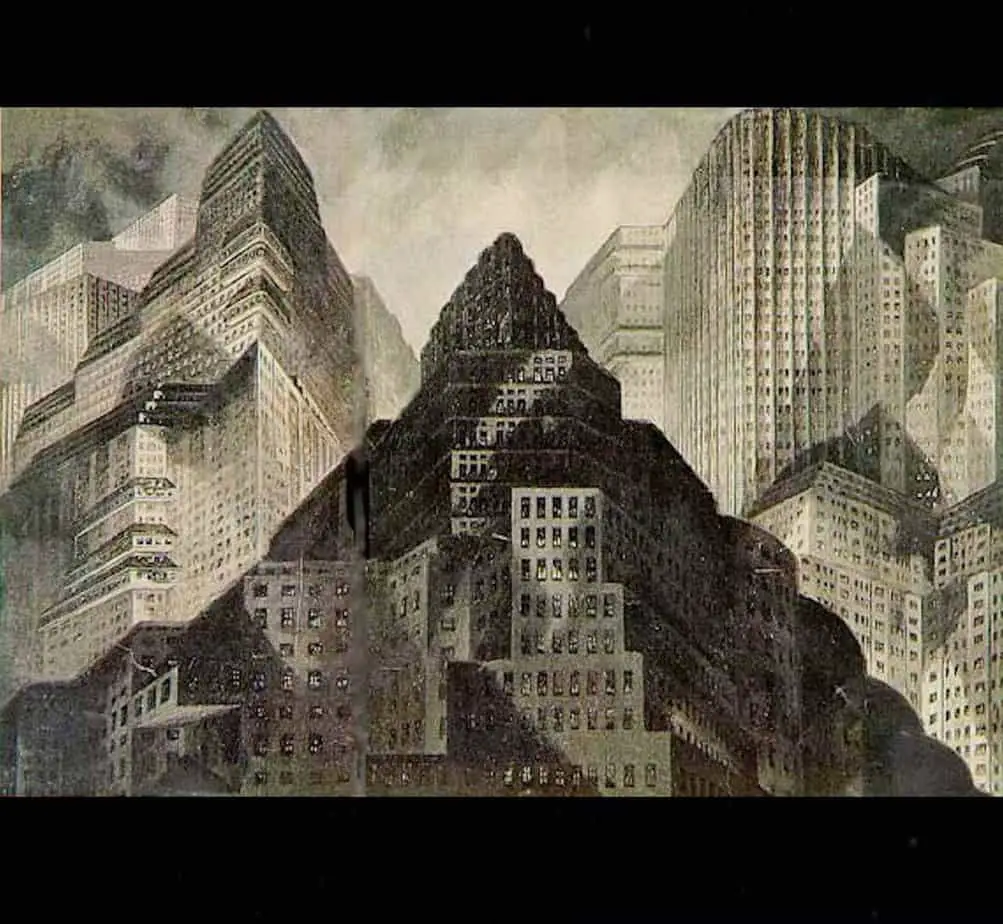

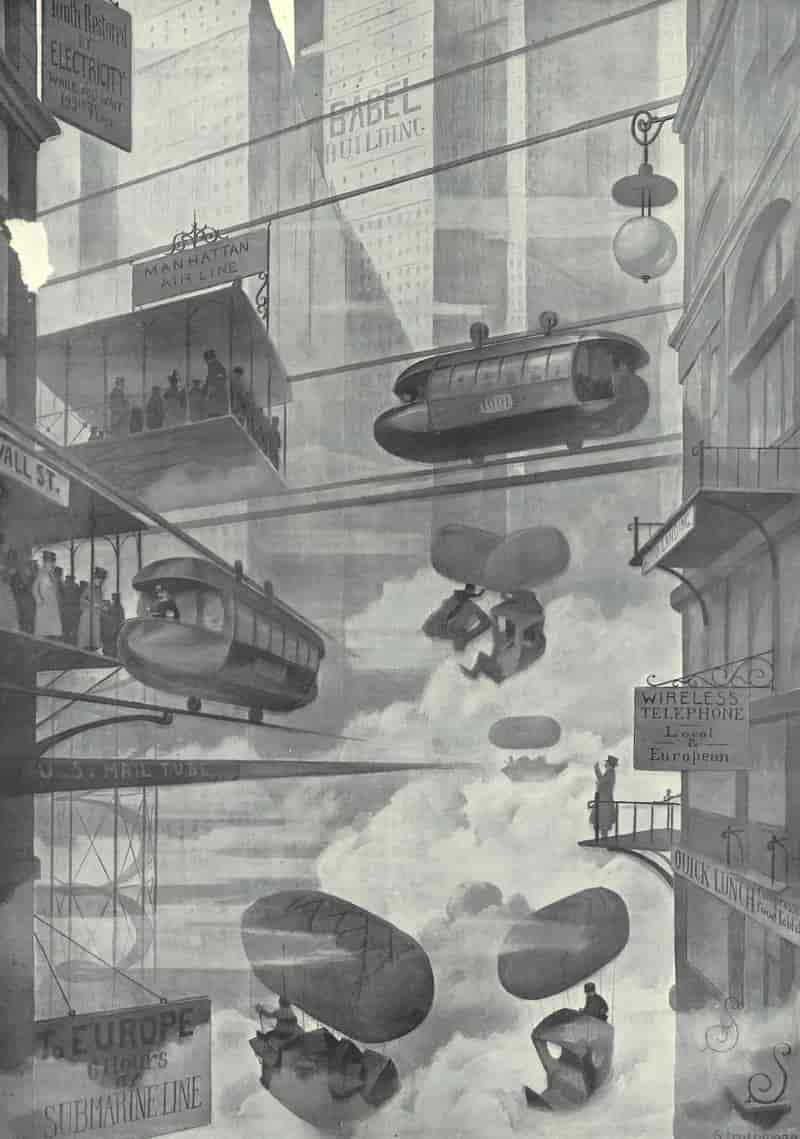

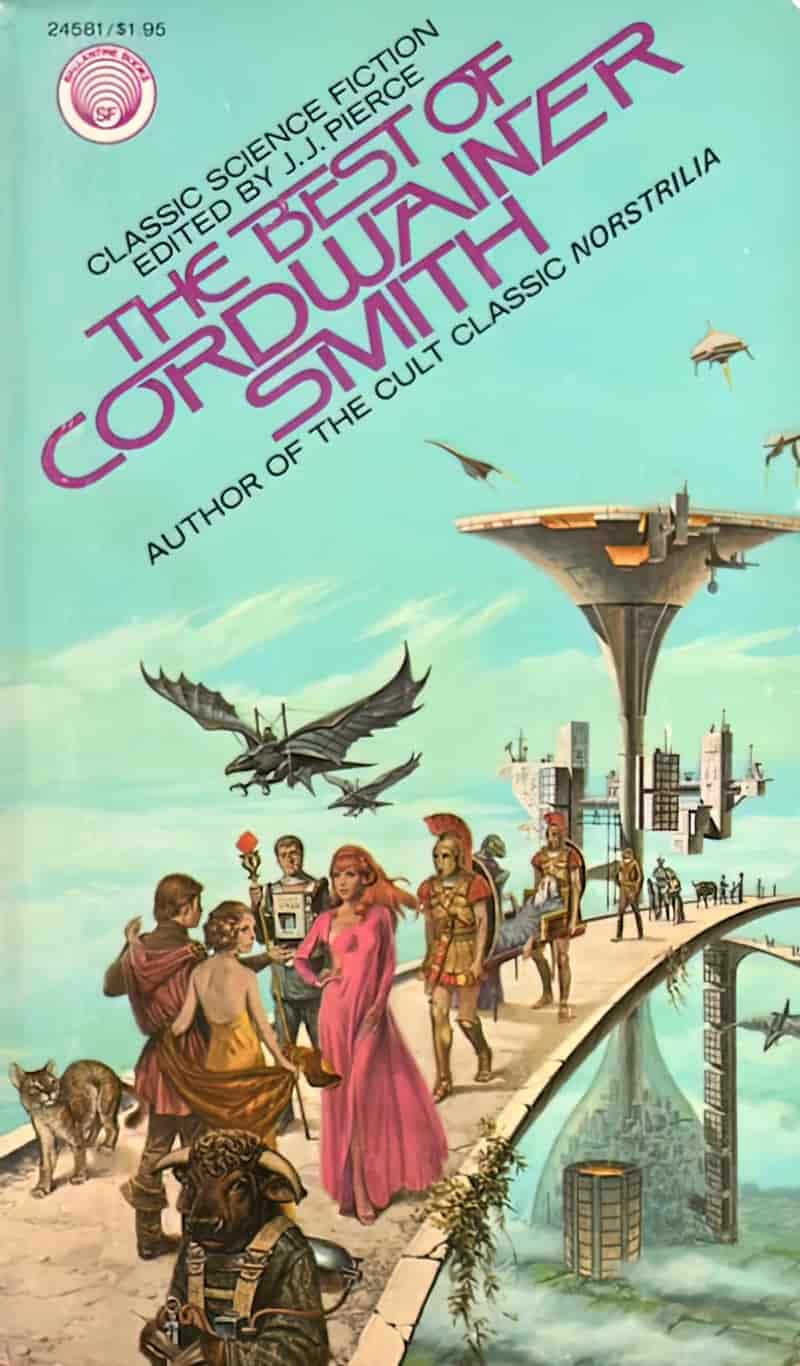

FANTASY VISIONS OF FUTURE CITIES

If we take a look at imagined futures, cities always seem to go up and down. This is indeed the general trend, as population density grows, building technologies improve and city buildings get taller and taller. What I find surprising is how far back these visions go.

Concept Art and Background Stills from the movie Metropolis (1927)

Header illustration: 1936 MY OWN STORY BOOK HCDJ Childrens I’m done groaned Meg