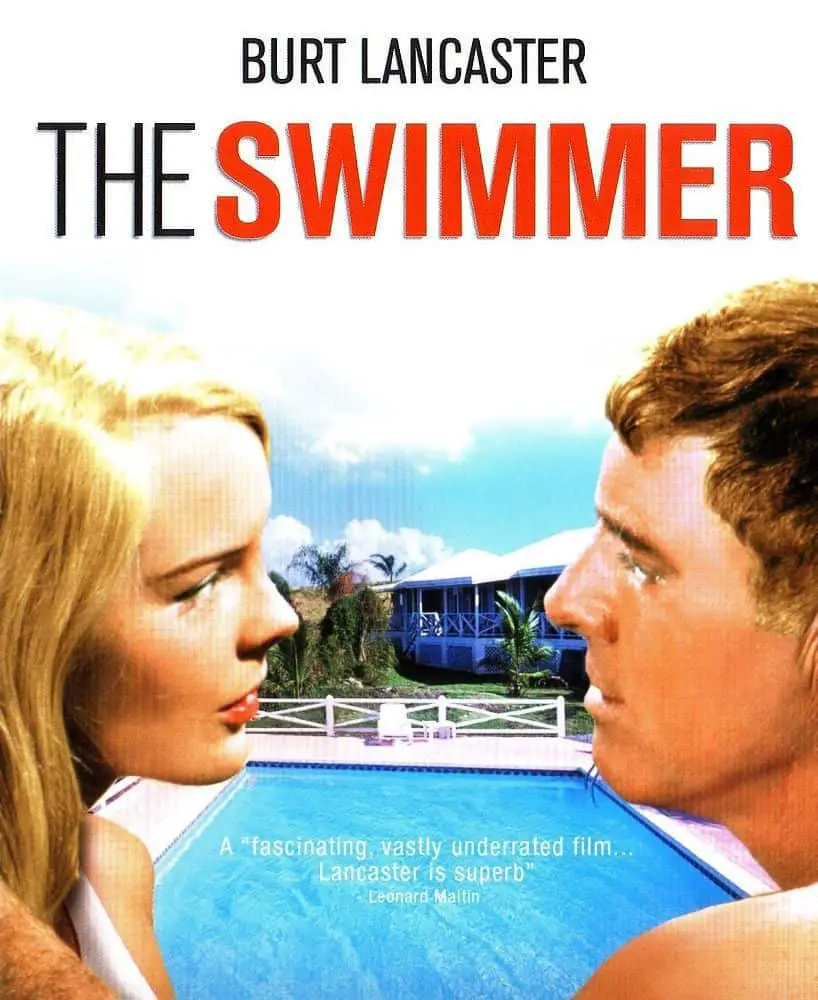

“The Swimmer”(1964) is considered one of Cheever’s best short stories. Anne Enright feels that this would never have worked as the novel Cheever had originally planned and adds that it would work even better as a short story had he lost one or two pools. (The naturist communists are amusing but we don’t want any more than that.)

Anne Enright reads John Cheever’s “The Swimmer” at The New Yorker Fiction podcast.

PLOT OF THE SWIMMER

Neddy Merrill, half-cocked on gin and tonics during a restorative summer brunch at the house of some friends, decides to return home through several miles of Connecticut exurb by swimming the lengths of contiguous pools. Thus begins a minor odyssey during which we watch as Neddy makes his way, first in drunken delight, but then through rainstorms, colder weather, and the hostility of former friends, gradually growing old and infirm, finally arriving home to find it deserted.

THE MILLIONS

In more detail:

The story begins with Neddy Merrill lounging at a friend’s pool on a mid-summer’s day. On a whim, Neddy decides to get home by swimming across all the pools in the county, which he names “The Lucinda River” in honor of his wife, and starts off enthusiastically and full of youthful energy. In the early stops on his journey, he is enthusiastically greeted by friends, who welcome him with drinks. It is readily apparent that he is well-regarded and from an upper-class or upper-middle-class social standing.

Midway through his journey, things gradually take on a darker and ultimately surreal tone. Despite everything taking place during just one afternoon, it becomes unclear how much time has passed. At the beginning of the story; it was clearly mid-summer, but by the end all natural signs point to the season’s being autumn. Different people Neddy encounters mention misfortune and money troubles he doesn’t remember, and he is outright unwelcome at several houses which should have been beneath him. His earlier, youthful energy leaves him, and it becomes increasingly painful and difficult for him to swim on. Finally, he staggers back home, only to find his house decrepit, empty, and abandoned.

Wikipedia

Is Neddy dead at the end of this story? That’s one interpretation, but is too literal for Anne Enright. There is a long tradition of stories with stings in the tail. This is another such story. It stings but we don’t know why, exactly. We don’t know how many years have elapsed between the beginning and the end of the story. In the end, the mood is the important thing about this story rather than the plot, which is simply a wrapper for the mood.

SETTING OF THE SWIMMER

Place

Cheever himself moved from New York to the suburbs of Westchester County, New York to bring up his family. Many of his stories are set in this kind of suburb, and he has been called ‘the Chekhov of the suburbs’. (He has also been called Dante of the cocktail hour.) He wrote a series of stories set in the fictional ‘Shady Hill’. This is a well-off suburb, where everyone seems to have a pool and house staff. They throw big parties and employ bartenders. No two pools are alike — quite a feat of description.

Time

The story is set on ‘one of those midsummer Sundays when everyone sits around saying, “I drank too much last night.” This is explained in the very first sentence. We don’t know exactly what year it is set, though the story was written in the 1960s. In fact, the lack of specific time is part of the story itself. By the end, we don’t know how many years have metaphorically passed between Neddy’s first and last swim. But we do know that this is the Cold-War era, when America is in International expansion mode.

CHARACTERS IN THE SWIMMER

Neddy has a kid’s name. A grown-man would more often be called ‘Ned’. His quest is childlike in its enthusiasm. He has the narcissism of youth, thinking of himself as a legendary figure, as little boys often imagine they’re superheroes. His ego depletes as he swims forth.

Cheever’s mastery lies in the handling of Neddy’s gradual, devastating progress from boundless optimism to bottomless despair, from summer to fall, from swimming pool to swimming pool….as we read the story we feel time passing, before our eyes; feel Neddy losing heart, growing weary, getting old.

Michael Chabon

The story opens with everybody’s hangovers, but Neddy is not complaining about his hangover. Probably because he’s still drunk from the previous night. By the end of the story he may have sobered up, and sees the reality of his life.

THEME IN THE SWIMMER

Neddy Merrill literally ‘floats’ over the reality of his life, which is that he’s drowning in his suburban life, and in his alcohol problem. Of course, this is the natural reading after knowing about the life of the author, but how would the story be interpreted if we knew nothing of Cheever’s alcoholism? This is a story about the denial of knowledge. Neddy is able to continue while his life crumbles beneath him.

Theme: People can remain brittle and tenacious even as things fade and dissolve under them. Yet there’s no morality in Cheever. He doesn’t wag a finger, telling us we must face up to reality.

Cheever himself said this story is about ‘the irreversibility of human conduct’. It’s about grandiosity of any description. You don’t have to be rich with lots of swimming pools in order to understand this story. This story is about drinking, but ‘we’re all drinkers’ (in some fashion or other).

“The Swimmer” is also an allegory for getting older. Everything withers and crumbles in the end. We just keep on trucking. There’s no turning back. The birds he mentions at the highway scene are a type of heron that get netted while trying to swim upstream.

The story has mythic echoes — the passage of a divine swimmer across the calendar toward his doom — and yet is always only the story of one bewildered man, approaching the end of his life, journeying homeward, in a pair of bathing trunks, across the countryside where he lost everything that ever meant something to him.

Michael Chabon

TECHNIQUES OF NOTE IN THE SWIMMER

This story is an example of how well Cheever is able to bring the reader into the story. The first paragraph offers a wonderful description of setting. He makes use of the second person, moving from the universal to the specific social group, ending/beginning with the priest. Drinking too much is juxtaposed against the church. Slate use the word ‘litany’ to describe the feeling evoked by the first paragraph. A litany is a ritual repetition of prayers when applied to the church, but is also used outside church settings to describe something which feels repetitious in a tedious sort of way.

At one point Cheever wanted to parallel the tale of Narcissus, a character in Greek mythology who died while staring at his own reflection in a pool of water, which Cheever dismissed as too restrictive. As published, the story is highly praised for its blend of realism and surrealism, the thematic exploration of suburban America, especially the relationship between wealth and happiness, as well as his use of myth and symbolism.

Wikipedia

The turning point is marked by the onset of the storm. Ned sees the first red and yellow leaves and starts to get signs that things are not all right. Yet Netty loves the storm. It’s a big drinker’s story. Along with the idea that nothing ever changes is another idea of ‘let it all come down’. Invite destruction. In the opening paragraph everything is lovely. The cloud is like a city, but this is no ordinary cloud.

Cheever has written an intensely dark story, there are comic elements, such as when the drivers on the highway throw things at him. Even the epic journey itself is fake and therefore laughable. But there is both pleasure and misery in this story. It’s a very slow apocalypse. The beautiful people are moving on, no longer beautiful; Ned has lost everything he ever held dear. The comic elements make this darkness even darker.

Cheever has chosen the names of his characters with care. Neddy’s wife Lucinda, for example, is named after ‘light’, which is associated with time.

Cheever uses sound to create extraordinary atmospheres.

Metaphysical moments are scattered throughout: The constellations of the sky, for example. (Another story like this is “Rabbit”.) Metaphysics is a traditional branch of philosophy concerned with explaining the fundamental nature of being and the world that encompasses it.

Not Quite Magical Realism

In fiction, when unreal elements appear, usually one of two things is happening. In the first case, the unreal actually is real. This describes much of genre fiction, in which the reader expects vampires and aliens to appear — would, in fact, be disappointed if they didn’t. In literary fiction, too, the unreal may be introduced with a straight face, for effect. Magical realism depends on the introduction of a fantastic element into otherwise grim reality, for instance in Gabriel García Márquez’s “A Very Old Man with Enormous Wings.” The appearance of an angel in a poor Colombian village creates a host of consequences, though a crucial difference between magical realism and, say, fantasy, is that in magical realism the narrative is primarily interested in the village, while in fantasy the author would focus primarily on the old man, his wings, how he got them, and what his home world is like.

More typically, in literary fiction, the fantastic occurs as a manifestation of the main character’s disordered psychology. In close third person, the narrative is so intimately linked to a protagonist’s point of view that the world appears in subjective terms, and if the main character is sufficiently disoriented — drunk, delusional, or simply experiencing very heightened emotion — aspects of their immediate surroundings may become distorted in a way that reveals their mental state. In William Kennedy’s Ironweed, Francis Phelan, an itinerant, guilt-wracked alcoholic sees the ghosts of dead people he’s known, some of whom he killed. Although the narrative never states that they are apparitions deriving from his fear and shame, it doesn’t need to: we are able to read them as having a kind of immediate corporeality, at least to Francis, while still being utterly unreal, figments.

So which of the two is happening in “The Swimmer?” Well, neither, really. On the one hand, it is impossible to read “The Swimmer” and think that the main events of the story are happening as described — that, in the course of a single afternoon, a man ages 30 years while becoming increasing destitute and reviled — unless we believe Neddy Merrill has entered some horrific parallel universe. On the other hand, it is equally impossible to read the events of the story as merely a manifestation of Neddy’s mental state. He’s been drinking as the story starts, but not that much. He is happy, overwhelmingly content in his life, really. Even if we were to read the story as a projection of Neddy’s subsumed life anxieties, it is impossible to imagine him projecting a vision of the world this entirely altered.

It is not magical realism because the strangeness is not intended to be taken literally — strangeness in magical realism is almost always encountered and acknowledged by multiple characters, and is, in fact, a device meant to comment on the interlaced relationships that form a society. Strangeness in Cheever performs the opposite function: it is personal, particular, atomizing.

THE MILLIONS

STORY SPECS OF THE SWIMMER

“The Swimmer” a short story by American author John Cheever, was originally published in The New Yorker on July 18, 1964, and then in the 1964 short story collection, The Brigadier and the Golf Widow. Originally conceived as a novel and pared down from over 150 pages of notes, it is probably Cheever’s most famous and frequently anthologized story.

Wikipedia

COMPARE THE SWIMMER WITH

New Zealand writer Keri Hulme writes stories with a blend of realism and surrealism. (Sometimes called ‘magic realism’.) See her collection Te Kaihau.

The surrealism is also a bit like the surrealism of The Graduate.

“The Enormous Radio“, also by Cheever, has the same sort of surrealism.

WRITE YOUR OWN

Where to start, if your intention is to practice writing a story of magic realism? I suppose we might first start with a theme and build a magical/surreal setting which makes the theme clear to the reader. In this type of story we write in a realistic way but we’re not obligated to write ‘the truth’. How does Neddy get into the public swimming pool? Does he carry spare change in his swimming trunks? I asked myself this question as I read, yet in this type of story it’s not important. When the details are specific and familiar enough, the reader will be drawn along for the ride.

If we’re to be inspired by “The Swimmer”:

- Start with a character embarking on a slightly absurd quest

- Decide what the quest stands for, thematically

- Include comic details

- Use the weather to help build atmosphere

- End with a sting in the tail

RELATED LINKS

- Read it here: The Swimmer PDF

- Listen to it here: The New Yorker Fiction Podcast, read by Anne Enright. (The second part of Enright’s commentary starts at -9:30.)

- Read Michael Chabon’s description of reading The Swimmer for the first time.

- Spark Notes

- Slate’s Audiobook Special

In this episode, we discuss “The Swimmer” by John Cheever. What can we learn from this fantastic story? What can we say about the point of view? How does Neddy’s journey drive the way we understand the story? Does a story need to be real? Does it have to mean anything? How do we figure out a story’s theme? How is emotion expressed in this story?

Why Is This Good? podcast