Swans are terrifying, right? My first memory of a swan: I am about three years old. At The Groynes with my father. If by slim chance you are from Christchurch New Zealand you’ll know that The Groynes is a river and park with playgrounds and many wild birds, mostly ducks, too many ducks. They crap in the water and actually it’s not safe to swim there, though many kids do. This was years ago. Who knows, maybe the water quality is much improved since 1981.

Anyway, I remember a scene with, like, a thousand ducks and one swan. Maybe two swans, but I only remember the one. We’ve brought a bread-bag of crusts from home. No one eats the crusts. You’re not meant to feed bread to birds, but who knew that in the early 1980s. My father says, “Here. Feed this bread to the swan.”

I don’t want to. This damn swan is bigger than I am.

“Go on, feed it, don’t be scared, feed it, go on, the swan won’t hurt you, go on, feed it, feed it, swans are harmless, go on, go on, feed it, go on, poor starving swan is starving, go on, feed it.”

Under duress I approach the massive swan standing on the side of the river bank. I tentatively offer my chubby, bread-holding toddler hand to the bird and, whaddaya know, I promptly get my fingers bitten hard by a sharp and fast beak.

I bawled my eyes out, and was cautious around birds after that. Pretty sure I never fully trusted my father’s take on reality after that, either. “It wasn’t that bad, didn’t really hurt, swans aren’t really scary…”

1980s parenting advice: Replace your child’s narrative and everything is fixed.

Watching Hitchcock’s adaptation of the Daphne du Maurier story didn’t help my ease around birds. Nor did moving to Australia as an adult. I cannot safely leave my house during Magpie Season. I wear wraparound sunglasses while out walking and, for now at least, retain two good eyes in my very own skull.

DESIGNATED SCARY BIRDS

But swans? Swans aren’t the designated Scary Birds, right? Think crows, ravens… any big bird who eats carrion… Black birds in general, who seem more street smart than you.

The swan in Dahl’s story is not a scary bird, either. She is magnificent. But she becomes associated with death.

THE EVIL AND RIDICULOUS GOOSE

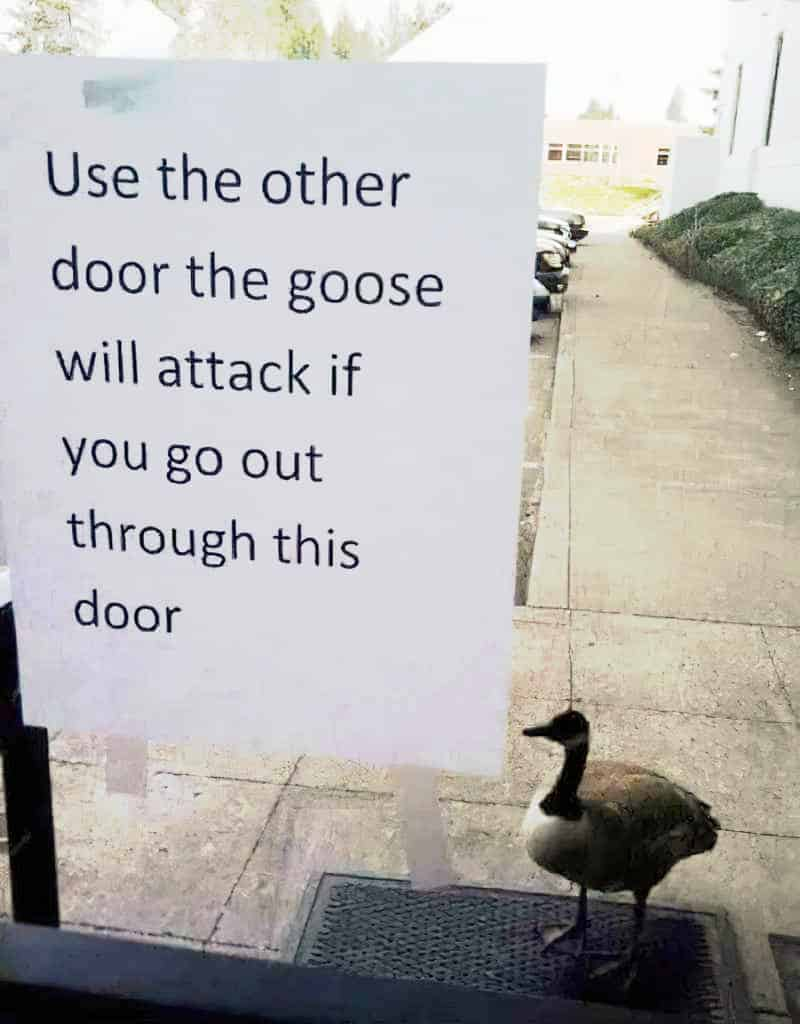

We need to talk about geese. On the Internet, geese are having a moment. Somehow the goose is both ridiculous and evil. There’s a popular game called Untitled Goose Game which plays right into this archetype. The player plays the evil goose.

Which came first? The evil goose or the evil reputation?

To be fair, real world geese can be quite evil.

ROALD DAHL, RUINER OF SWANS

Meanwhile, the swan gets off scot free with a tragic back story courtesy of Hans Christian Andersen. The goose is ridiculous and evil whereas the swan is elegant and beautiful.

That said. Roald Dahl did his level best to ruin swans for us. Personally, I didn’t need Dahl’s input in that regard. None of this is the poor mother swan’s fault. This story ruins swans by association. If you haven’t read it yet, be warned. The story features animal cruelty and bullying.

WHERE TO READ “THE SWAN” BY ROALD DAHL

“The Swan” is the fourth short story in Roald Dahl’s 1977 collection The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar and Six More.

- The Boy Who Talked with Animals

- The Hitch-hiker

- The Mildenhall Treasure

- The Swan

- The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar

- Lucky Break

- A Piece of Cake

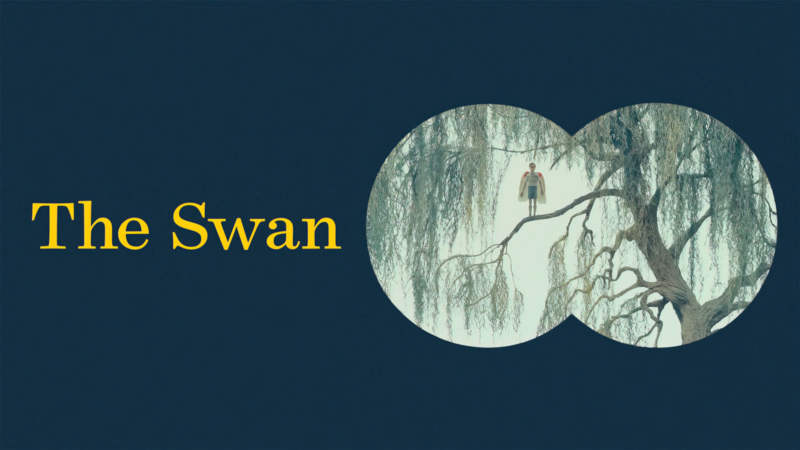

In 2023, Wes Anderson released a short film as part of a series of shorts based on Roald Dahl short stories.

The difficulty in adapting such a gruesome story for screen: How to avoid traumatising the audience? Most people have low tolerance for bird cruelty even if we happily tolerate violence against humans on screen.

Anderson had the same hurdle with adapting “The Ratcatcher“, and avoids onscreen gore by using some original techniques.

Here, Rupert Friend plays the grown version of Peter who first takes the audience through a maze made of hedges, hay bales and maize, then opens a door in the maze onto a railroad. He re-enacts the rest of the story by describing a memory.

A younger version of himself stands nearby but doesn’t speak. The effect is a highly-stylized version of Roald Dahl’s original.

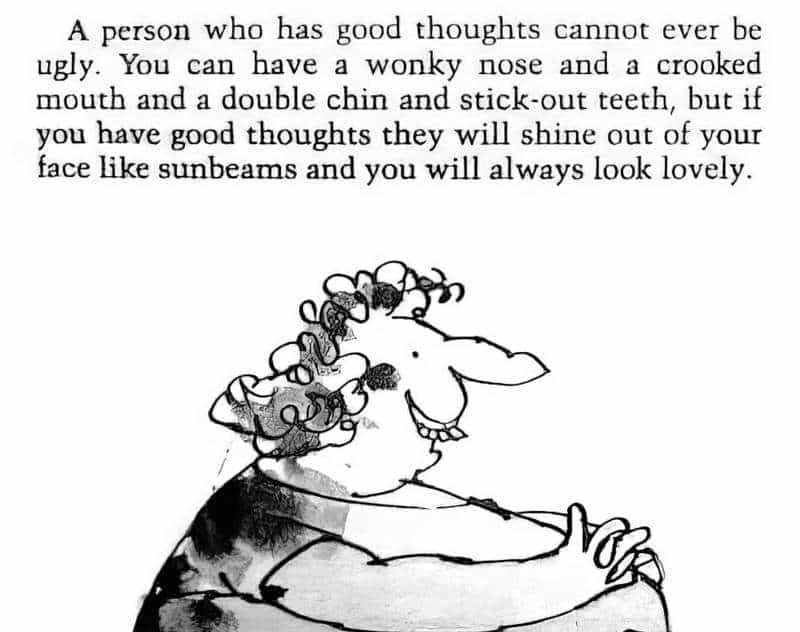

Publishers of Roald Dahl’s children’s books walked a fine line. Choice of illustrator was crucial. In the end, Sir Quentin Blake was a perfect match. Blake’s loose sketches are expressive and full of life, but not scary in and of themselves. Scary stories with scary illustrations were too much.

We know this because Quentin Blake’s illustrations replaced scarier versions. An illustrator Rosemary Fawcett was contracted to illustrate some Dahl work early in Dahl’s career, but her illustrations were not used. They are too scary.

SETTING OF “THE SWAN”

- A picturesque village somewhere in Britain with narrow hedgy lanes

- Saturday morning in May

- Beautiful countryside surrounds them with chestnut trees in full flower, hawthorn white around the hedges. The hedges are home to birds such as bullfinches, hedge sparrows, whitethroats and yellowhammers.

- A railway line runs through the village.

- There’s a big lake which is a sanctuary for water fowl. The lake is fairly narrow with tall willow trees growing along its banks. The water is clear and clean near the middle. A forest of reeds and bulrushes grow in the water nearer the banks.

- Dahl lists the bird species on the lake: wild ducks (mallards — in the Americas wild ducks are muskovys), moorhens (a.k.a. marsh hens), coots (a black water bird) and ring-ouzels (a type of thrush).

- There’s a rabbit field over the hill and behind the lake but it’s private land belonging to Douglas Highton.

CAST OF CHARACTERS IN “THE SWAN”

ERNIE

Straightaway we learn Ernie has been gifted a gun. Today is his fifteenth birthday. What’s this kid doing with a gun?

Dahl describes him as big and loutish with ‘small slitty eyes set very close together near the top of the nose. His mouth was loose, the lips often wet.’

Roald Dahl wrote thumbnail character descriptions under the assumption that a nasty looking person was a nasty person. Then he attempted to reverse this lifelong writing habit in The Twits, by writing this:

Personally, I don’t buy it, and suspect an editor of Dahl’s of writing it. (Matilda was a much meaner story before his editor Steven Roxburgh turned it into a feminist text.)

ALBERT (ERNIE’S FATHER)

We know he’s supposed to be a layabout because watching TV already at 9:30 on a Saturday morning is a heuristic for laziness. He’s so lazy he’s given his son a gun so the son can shoot meat for dinner.

He’s also a drinker. He requires a quart bottle of brown ale.

As the story progresses, we’ll see that Ernie is a bully. We can deduce that the apple hasn’t fallen far from the tree. Ernie has learnt how to act from his own father.

The father urges his son to go out and shoot some spadgers. What’s a spadger? Importantly, it means two things in this British dialect:

- house sparrow

- slang : a small boy

Basically, the father could be urging the son to go out and shoot a small boy.

ERNIE’S MOTHER

A bullied and ineffectual parent due to the household hierarchy with her husband as boss.

RAYMOND

Ernie’s friend. He lives close by. The boys summon each other by whistling.

Raymond never went anywhere without a big ball of string in his jacket pocket, and a knife.

“The Swan”

String as Chekhov’s gun? (The gun of the opening sentence has already gone off.) The boys are tying their bird kill to a length of this string.

Fortunately for Peter, the victim, Raymond is impulsive in nature. His attention quickly moves from one diverting thing to the next.

PETER WATSON

For readers who picked up that spadger refers to both bird and boy, no surprise when Ernie and Raymond prey on the small boy, who happens to be looking up into a tree with binoculars, watching a green woodpecker at the time.

BIRD-WATCHING OR “TWITCHING”

Immediately we know this boy is the inverse of a bird killer. He is a twitcher — a pastime which involves the pursuit of a previously located rare bird. The bird is never harmed.

In a different story, Dahl described a rat catcher as a rat. Here he describes the bird-watching boy as looking a bit like a bird, suggesting some special affinity with nature.

He had a small, frail body. His face was freckled, and he wore spectacles with thick lenses. He was a brilliant pupil, already in the senior class at school although he was only thirteen. He loved music and played the piano well. He was no good at games. He was quiet and polite. His clothes, although patched and darned, were always clean. And his father did not drive a truck or work in a factory. He worked at the bank.

“The Swan”

Peter is basically a Nerdy Birdy.

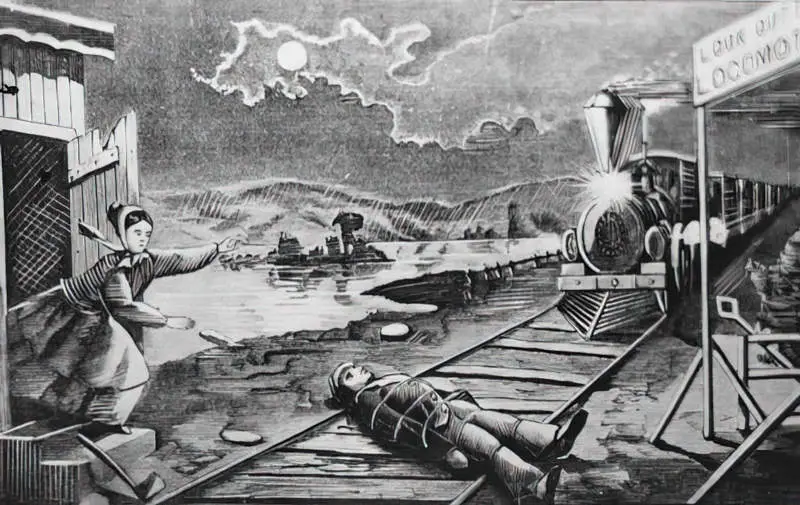

CHAINED TO A RAILWAY TROPE

Sure enough, that string is an example of Chekhov’s gun. The bully boys use it to ‘truss’ their victim ‘like a chicken’, further cementing Peter in the reader’s mind as a helpless bird.

Dahl has also mentioned the railway line while describing the picturesque village. As the only non-natural detail in the description of countryside, the railway line stood out as an ominous arena. And now the bullies drag their younger victim down the embankment towards the track.

You may assume, as I did, that the scene of chaining someone to a railway is a trope from old Western films. In fact, this trope was rarely used straight. Even from the beginning, it was usually messed with in some way, usually for comedy purposes, or for titillation.

The typical victim of a railway chaining is a maiden in distress archetype. So when Ernie and Raymond chain Peter to the railway, they are also feminising him. Note that Augustin Daly’s 1867 melodrama play Under the Gaslight features a rare male victim, and in an example of gender subversion is in fact rescued by the fair maiden.

Note that across literature, it is mostly women who are compared to birds (and also cats).

THE BOYHOOD TRADITION OF TRAINSPOTTING

As well as a bird-watcher, young Peter likes to watch trains.

Along this stretch of track they traveled around eighty miles and hour. Peter knew that. He had sat on the bank many times watching them When he was younger, he used to keep a record of their numbers in a little book, and sometimes the engines had names written on their sides in gold letters.

“The Swan”

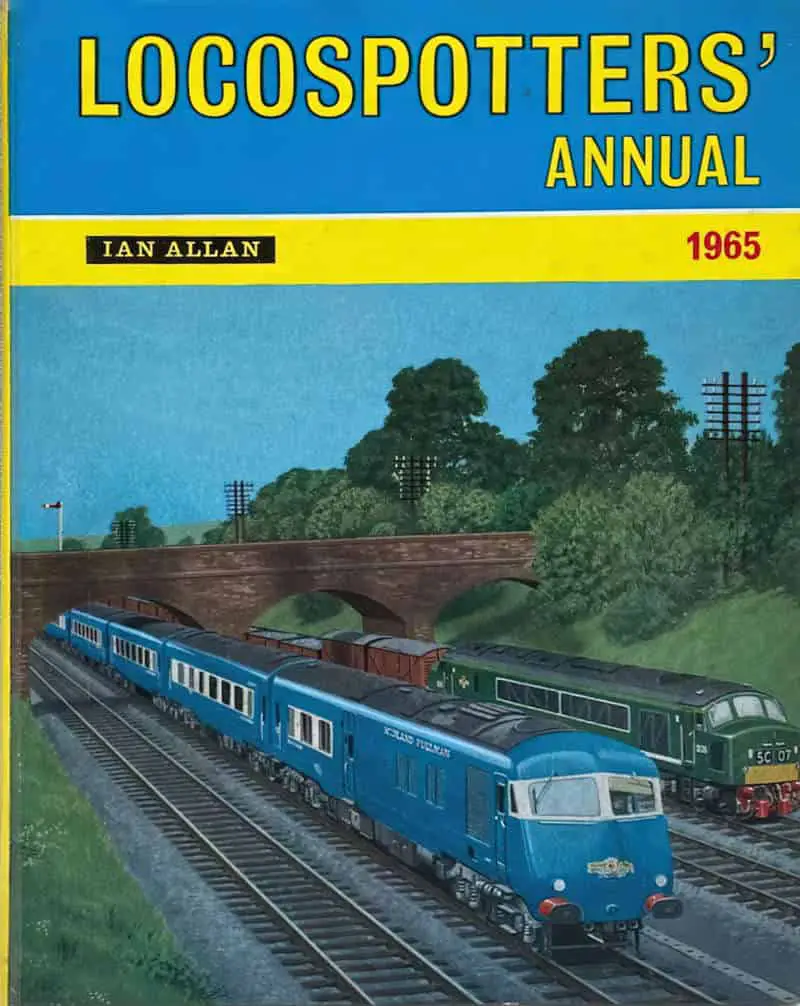

Trainspotting as a hobby used to be very popular, especially among adolescent boys. Basically, trainspotting is the practice of watching trains with the aim of noting distinctive characteristics. It appeals to our instinct to collect, and provides a reason to visit new parts of your country. “Bashing” refers to going somewhere for the purpose of seeing trains. People who love trains also often love radios, though in this story Dahl has made the link between bird-watching and train-watching.

In England, a train clerk called Ian Allen used to print a list of all the locomotives across the country and sold it as The Locospotters’ Annual.

Most (straight) trainspotting boys lost the interest once they became interested in girls, and those who persist with the hobby into adulthood are seen as a little strange by the mainstream as a result. A derogative word for trainspotter is ‘anorak’ because trainspotters will brave wet weather to pursue their interest. (Note that ‘anorak’ still refers to an actual raincoat in other parts of the English speaking world e.g. in New Zealand.)

‘To grice‘ is another word for trainspotting, and ‘gricer’ is another word for trainspotter.

Although trainspotting is an especially British phenomenon, there are enthusiasts in other countries. In the USA trainspotters are pejoratively known as ‘foamers’ (because they are thought to metaphorically foam at the mouth whenever they see a steam locomotive).

In any case, a strong interest in trains is quite common, though non-normative and therefore easy to mock. Trainspotters know how to have low-cost fun. You don’t need to buy anything at all, which means you’re not contributing to capitalism. You’re also not interested in showing off your wealth to others, which means you are outside the societal pecking order. For as long as trains run, trainspotters have a never-ending stream of novelty, and always have something to discuss with likeminded enthusiasts.

It is useful for Dahl to make Peter a trainspotting kid, because via Peter’s point of view, all trussed up on the tracks, we have all the information we need to truly dread the arrival of the next train.

Fortunately for Peter, he’s small enough to fit right under the train.

At least six people in the United States were killed between 1874 and 1910 as a result of being tied to railroad tracks. Of course, it was never as common in real life as in fiction, no doubt because there are more efficient ways of murdering people.

TV Tropes

Peter is geeky but also smart. He understands intuitively that these two are real trouble. The word ‘psychopathy’ was yet to mean what it means today. The closest descriptor he can find is ‘hooligan’. Psychopathy is not a clinical diagnosis. “Callous and unemotional traits” is the clinical descriptor.

It is impossible to look at a child with callous and unemotional traits and predict adult psychopathy because the child brain is still very much under development. However, adults who later become known as psychopaths have always shown signs since early childhood, and certainly before the age of fifteen, so it is interesting that Roald Dahl makes this story happen on a young psychopath’s fifteenth birthday. Typically, before psychopaths harm other humans they will have tortured animals.

See also: A kid can’t be diagnosed as a psychopath. Why? from All In The Mind podcast, ABC.

Young Peter knows these boys and he instinctively knows to ‘grey rock’ them. When captured by psychopaths, sociopaths and narcissists, sure enough, the best thing to do is make yourself as uninteresting as possible:

he must continue to be passive. Don’t insult them. Do not aggravate them in any way. And above all, do not try to take them on physically. Then, hopefully, in the end, they might become bored with this nasty little game and go off to shoot rabbits.

“The Swan”

The bullies mean to throw him into the lake, still bound and helpless. Except Dahl uses Raymond’s distractibility to save him. Plans change. Now they’ll torture the bird-loving Peter to retrieve their kill.

PETER’S FATHER

In stark contrast to Ernie’s father, who we briefly met earlier, Peter’s father is the sensitive type who has taught his son to be observant.

[T]o keep his mind off the thing that was going to happen soon, he played a game that his father had taught him long ago on a hot summer’s day when they were lying on their backs in the grass above the cliffs at Beachy Head. The game was to look for strange faces in the folds and shadows and billows of a cumulus cloud. If you looked hard enough, his father had said, you would always find a face of some sort up there.

“The Swan”

The sad irony is that while Peter was watching a bird through binoculars, his monotropic focus made him vulnerable to bully predators. Moreover, this is an era where observant people are treated with suspicion:

You’re a spy. And you know what ‘appens to spies when they get caught, don’t you? They get put up against the wall and shot.”

“The Swan”

THE WHITE SWAN

After the bullies start treating Peter like their retriever dog, they happen upoon the ‘magnificent white swan sitting serenely on her nest … like a great white lady of the lake’.

Peter points out that swans are the most protected birds in England. The law was created because swans were eaten as a special delicacy at medieval feasts. Rights of ownership could be passed on to favoured friends and associates of the monarch.

Nowadays, swans are no longer considered food, but remain protected as one of England’s quirkier laws.

‘Today The Crown retains the right of ownership of all unmarked mute swans in open water, but The Queen mainly exercises this right on certain stretches of the River Thames and its surrounding tributaries.

The Royal Family’s website (2021)

That these bullies wish to eat a swan links the story to ancient times in the most violent of ways. These boys really are in the wild — not just in the wilderness next to the village, but they’ve also moved from linear time (chronos) to mythos, outside the normal boundaries of time. This is a dark, fairy tale setting. In fairy tales, the land just outside civilisation symbolises the subconscious, where characters confront their deepest fears.

Dahl’s tale takes a turn towards the fairy tale now, because Ernie tells Peter he can make the dead swan come alive. That only happens in fairy tales.

The psychopaths chop off the dead swan’s wings and attach them to Peter’s back, again with the terrible string. They march him along the riverbank. They order him to climb to the top of a willow tree and fly.

WHAT TURNS REALISM INTO MAGIC?

Something happens to Peter when he’s in the willow tree. The willow tree functions as a magic portal.

Weeping willow trees have long played a part in witchcraft and magic:

- The sorcery teacher Hecate was the Greek goddess of the moon and willow tree.

- The poet Orpheus took willow branches with him when he went to the Underworld. Poets considered the willow tree holy.

- The goddess Helice had priestesses who also employed willow in their magic.

The droopiness of their foliage has made them perfect for personification — it’s all in the name. Weeping willow.

THE FALSE ENDING

When Peter flies into the sky with those wings, readers will inevitably think of angels. This will make us think he has bled out after being shot in the thigh.

Interestingly, the imagery of winged angels does not come from The Bible:

Winged beings are an essential part of the folklore of every culture. From the times of Babylonia and the Pharoahs, sculptors were preoccupied with putting wings on lions and unidentifiable beasts. Although the angels of biblical times were never described as being winged, painters and sculptors have always persisted in giving them feathered appendages. (Actually, the old-time angels appeared like ordinary human beings. They even had supper with Lot.) When demons over-ran the planet during the Dark Ages they were also recorded as monstrous entities with bats’ wings.

The Mothman Prophecies, John Keel, 1975

So we think Peter has died.

But after the section break, Dahl reveals that Peter manages to fly all the way home to his mother. He is even seen by three reliable witnesses, who Dahl names for the sake of verisimilitude.

Peter is found by his distraught mother. This is the scene with the emotional payoff.

WHAT HAPPENS AFTER THE STORY ENDS?

The mother will undoubtedly take her son to the hospital. We can imagine Peter survives, and hope that the bullies are sent to Borstal, as was mentioned earlier.

We can be confident Peter calls the cops on these boys because across Dahl’s corpus of work, we know for sure he enjoyed a good revenge tale. Pretty much everything ever written by Roald Dahl is a revenge fantasy. The Twits is his uber revenge tale — a story for children which was re-written using the main element of a much earlier short story called “Smoked Cheese”: A man plagued with mice disorientates them by gluing his furniture to the ceiling.

Or maybe revenge is served sweetest if Peter stays as a bird.