Homes are an outworking of the characters who live inside. Sometimes, in fiction, the house even seems to come alive in its own right.

There exist sunny houses in which, at all seasons, it is summer, houses that are all windows.

Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space

For my notes after reading Gaston Bachelard, see Symbolism of the Dream House.

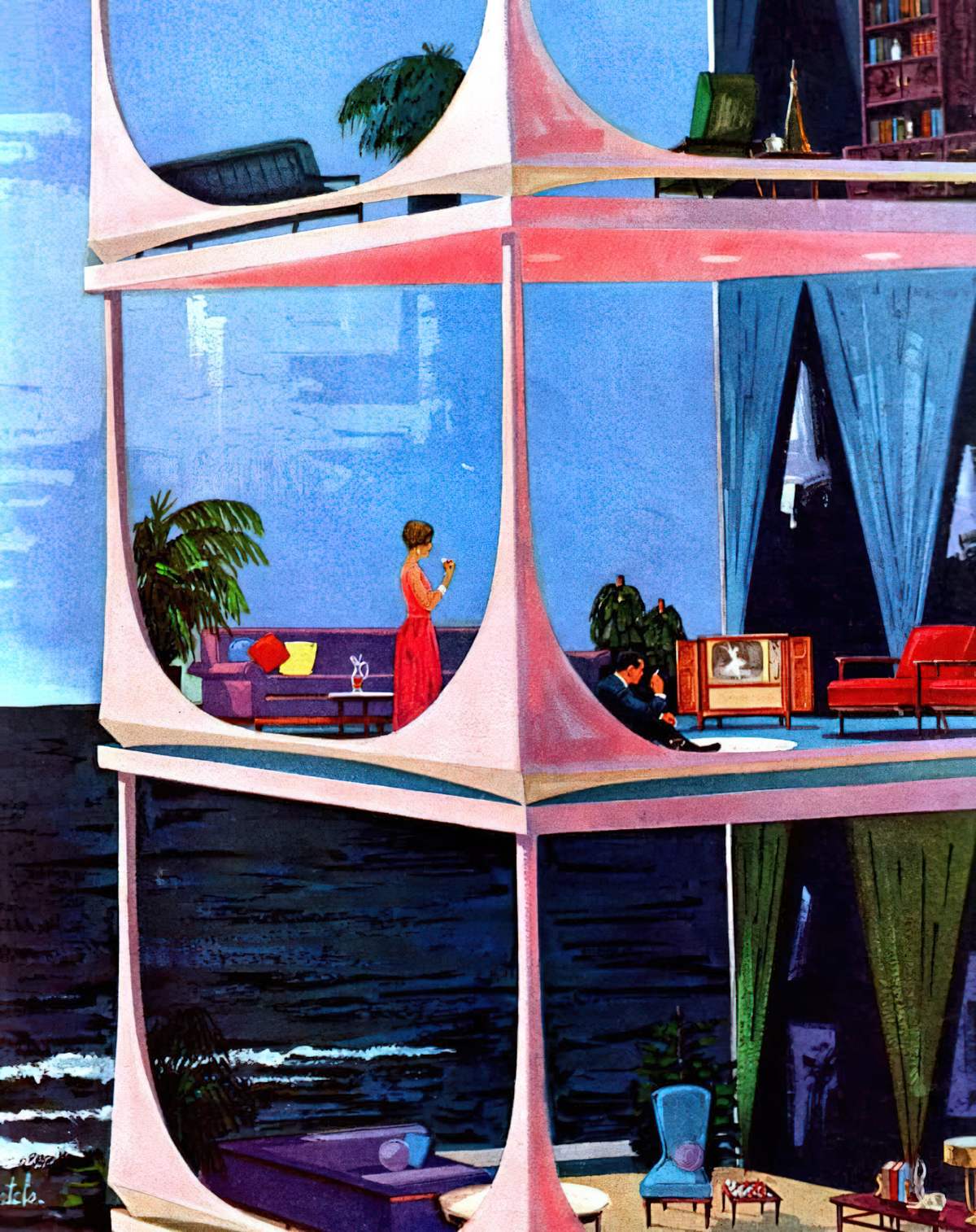

THE GLASS HOUSE AND THE INFLUENCE OF FARNSWORTH

The famous Farnsworth House is a square construction made mostly of windows and constructed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe between 1945 and 1951. It’s in Plano, Illinois.

In real life, people who build these houses tend to be well-off and have environmental aspirations. When a house has this much glass you’re living ‘at one with nature’. You’re also respecting the environment by refusing to build something garish. From a distance, the house hardly interferes with the natural landscape, with the trees reflecting off the windows, and the lack of a pretentious, gabled roof. (I’m not sure about their energy efficiency rating, though.)

In fiction, however, the glass house generally spells doom for you and your family. If you are a fictional person reading this, I advise against purchasing a house made mainly of glass.

LAKE HOUSE

The glass house in the movie Lake House (with Keanu Reeves and Sandra Bullock) is based on the Farnsworth architecture. The character who lives in this house is an architect, and in movies, architects can’t live in ordinary houses. Here, the house is ‘at one with the water’.

THE ICE STORM

One of the families in The Ice Storm — The Carver family — live in a very nice house with a lot of glass. They could be enjoying their Thanksgiving dinner, at their beautiful table with lots of food, under the cover of glass but still enjoying the late autumn scenery. But the 14-year-old daughter is far too astute to be fooled by appearances — on the other side of that ‘glass’ people are starving. The meaning of Thanksgiving is built on abuse, she points out.

In the following clip, we hear how Connecticut was the first place to really embrace the glass house, but a lot of the time they weren’t ‘beautiful’ — they simply functioned like fish bowls. In the glass house, the irony is that the family can’t see each other. This glass house juxtaposes with another main house, which is a 1950s colonial house. This was also an archetypal architectural time, but would be a little less cold. The colonial house is the key party house, which makes the key party seem even dirtier.

INTO THE FOREST

Into The Forest (2015) is set somewhere in Canada, but more ‘correctly’ somewhere in fairytale world. Viewers who expected mimesis were utterly disappointed that these young women were able to sustain themselves by finding berries in the woods over a long winter. This is the stuff of fairytales, and I code it as such.

The difficulty is, these girls live in the present, or actually in the near future, probably. The father has purchased a partially finished house with large, glass walls and transplanted his daughters to their forest haven. Then the outside world breaks down — a Doomsday Prepper’s dream.

The girls are suddenly alone and vulnerable. The house which seemed like a haven is now a target for predators. They end up boarding over those massive glass walls, first putting makeshift curtains up, then realising this will never be enough.

This house is an interesting mixture of ‘cold glass house’ and ‘warm, cosy house’. The house itself is a character in the movie, and therefore has its own ‘character arc’. For the house, the film is a tragedy along Gilbert Grape lines.

For a similar film about a family who must survive in a kind of fairytale utopia after calamity hits Earth — or America — see A Quiet Place. One garnered excellent reviews; the other did not. I have my own feminist theories about why.

WIENER DOG

Wiener-dog (2016) is an indie film which connects four short stories via the travels of a dog who never finds a permanent home. The first household we meet is desperately unhappy. Sure enough, they live in a house with walls made mainly of glass.

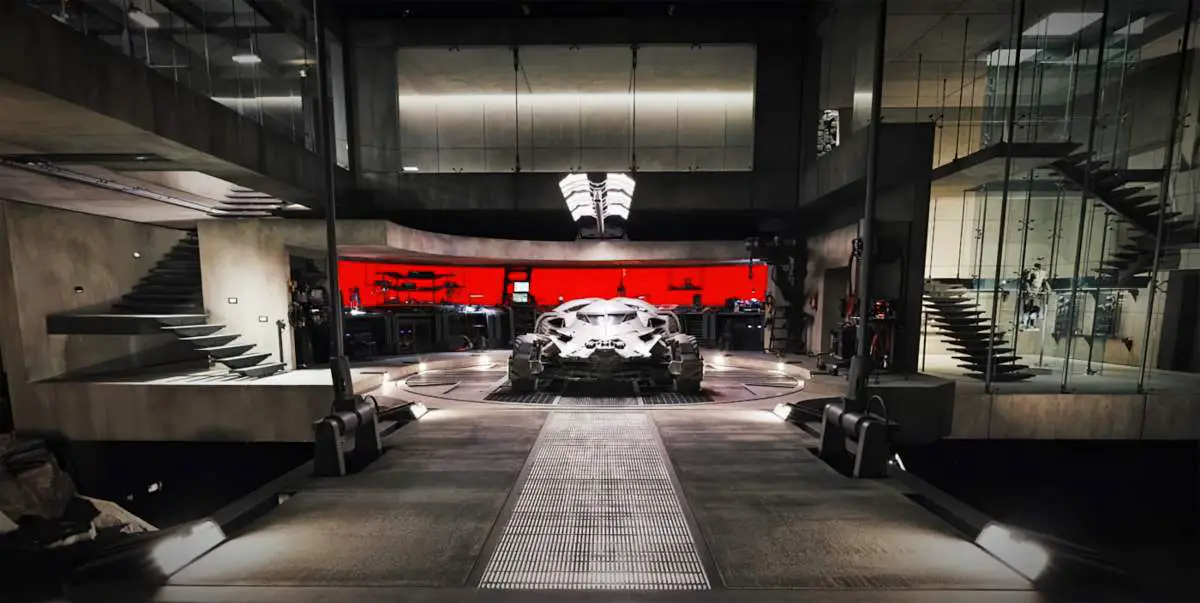

BATMAN VS SUPERMAN

Bruce Wayne’s residence is also a big glass thing. You can explore it using Google Street View. In the film there is an underground lair where criminal activities occur.

TWILIGHT

The vampires live in a glass house in the middle of the forest. You’d think they’d want a bit more privacy, wouldn’t you? But the forest itself provides the walls and curtains. In contrast to the more homely vibe emitted from Jacob, the Cullens are a cold, stand-offish clan, and so the house made of glass is fitting.

If you’re wondering where the house from the films is located, it’s a slightly complicated story:

The Cullen House is supposedly located in Forks Washington. But as we have learned, most of the filming for the original Twilight movie was done here in Portland and the surrounding area. For New Moon and Eclipse they used another home in Vancouver BC area. For Breaking Dawn 1 and 2 they broke down the house in Vancouver and loaded it on semi-trucks and transported it to the Louisiana sound stage where those films were made. It’s amazing that it is still so easily accessible for Twilight fans.

FERRIS BUELLER’S DAY OFF

Because a house made of glass is such an ostentatious statement — while ironically seeming to fit into the surrounding landscape unobtrusively — this building, which exists only to house cars, is comedic in itself.

Annie Proulx’s short story “Negatives” is another example of the ostentatiously glass house used to symbolic effect.

FAHRENHEIT 451

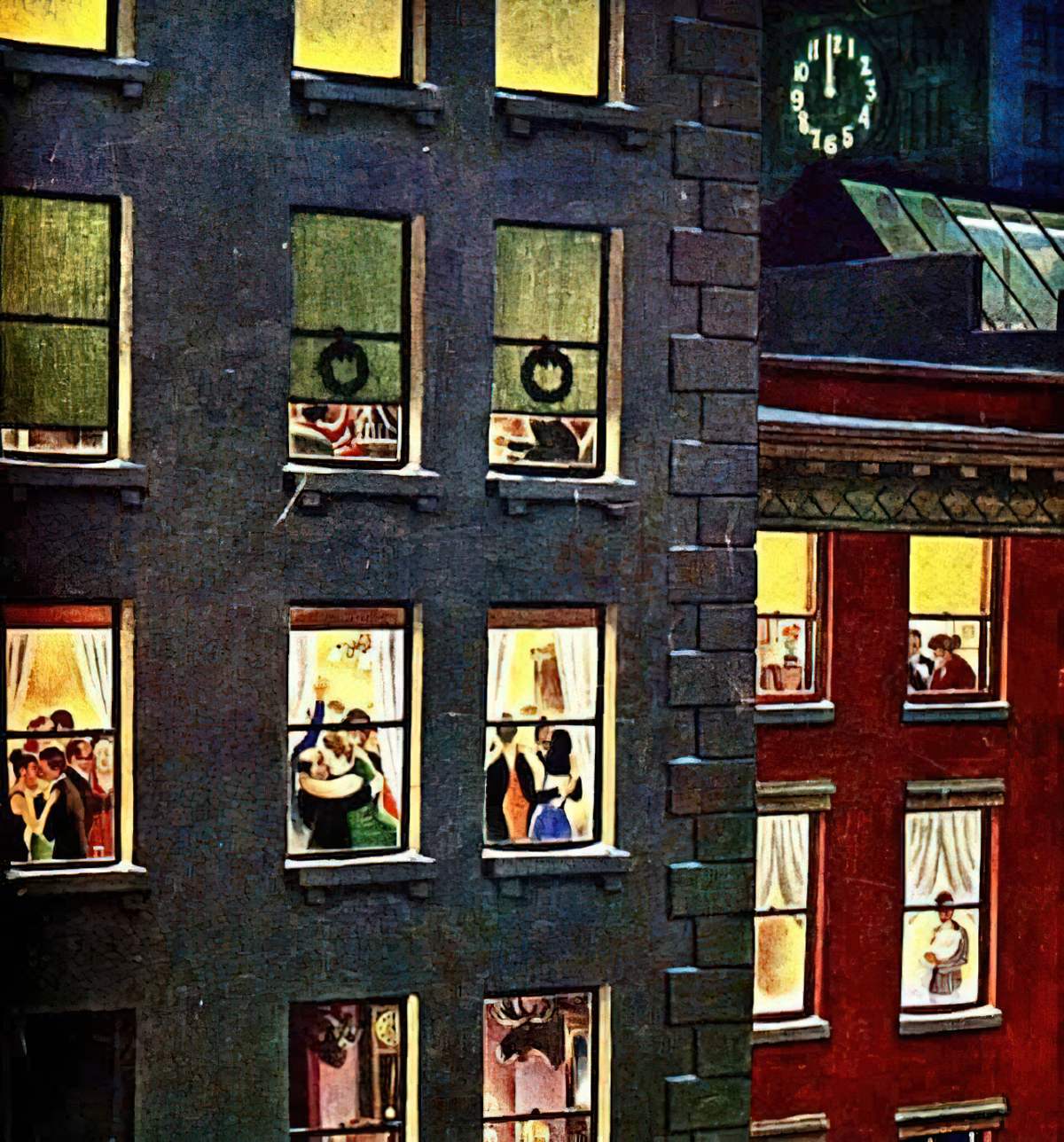

HOUSE OF CARDS

Despite their terrible sleep hygiene, you won’t find light-filled rooms in House Of Cards.

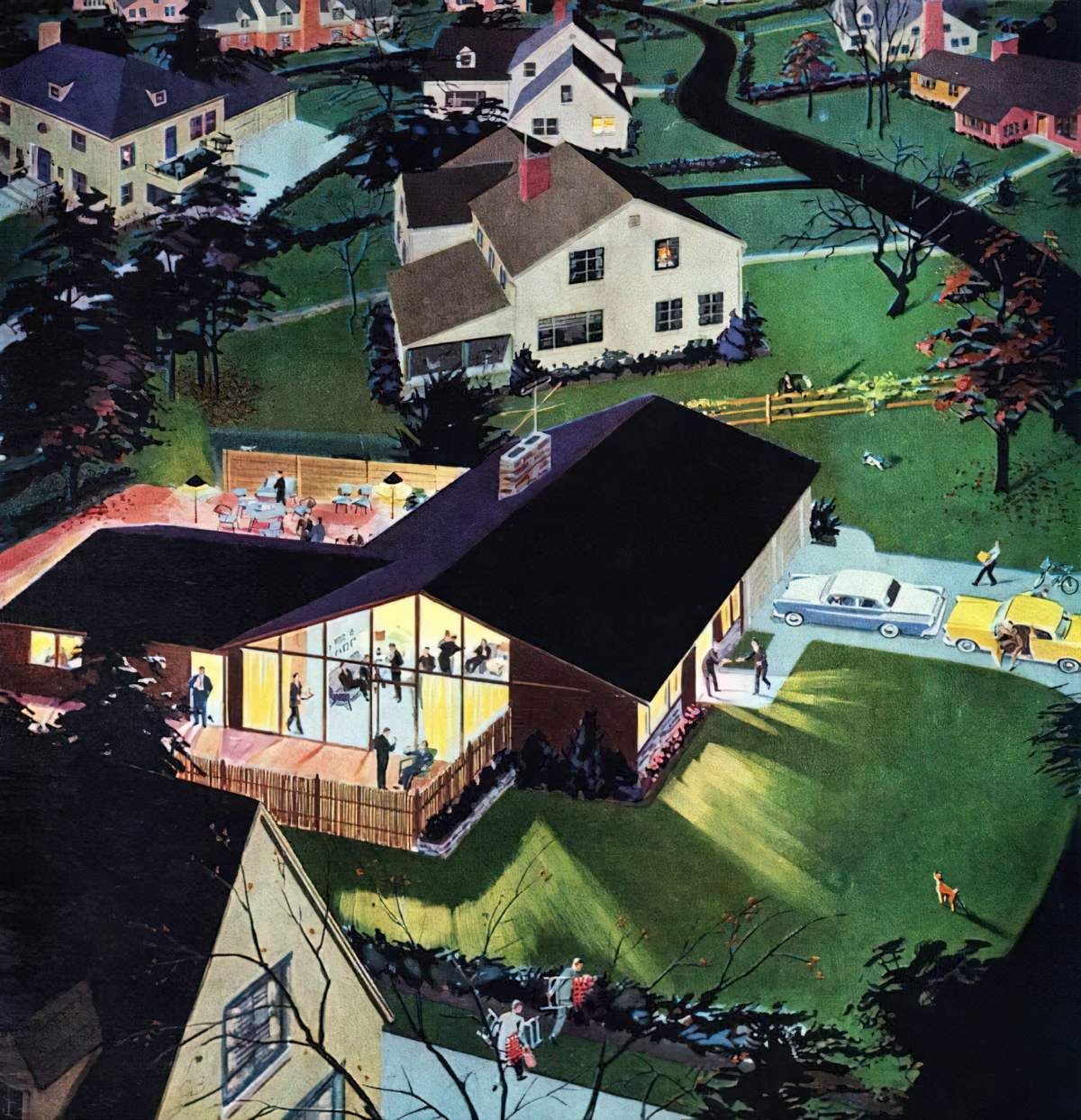

MAD MEN

Mad Men is equally dark as House of Cards in many ways, but well-lit rooms are quite usual in this series. Mad Men is an snail under the leaf setting. Don Draper has everything he could possibly want… from the outside looking in.

California is the flip side of New York — New York is wintry and studious while California is light-hearted and beachy.

But even on the East Coast, the light-filled kitchen scene here only highlights how down-and-out Betty Draper seems. Her mood contrasts equally with the upbeat innocence of their children.

DON’T TRUST THE B IN APARTMENT B

Krystin Ritter is actually the perfect fit for dark stories and her look has been utilised thusly in Breaking Bad and Jessica Jones. You won’t find many light-filled homes in those series. But here she is in a light-hearted comedy, bathed in a white, welcoming glow.

TROPHY WIFE

Here’s another Pinterest-worthy white kitchen in a light-hearted series.

SUBURGATORY

Though the title of this series suggests a kind of hell, the home is filled with natural light. This is a safe house in some well-off suburbs.

GILMORE GIRLS

The opening of Gilmore girls shows the main characters drinking coffee inside Luke’s, but at night, with all those fairy lights. In that case, the dark forms a cloak of reassurance and cosiness. During the day, Luke’s is always a place of refuge, even when he goes out of his way to be gruff.

Emily and Richard’s house has no natural light at all — a cold house from another age. What age is that, exactly?

The Centennial encouraged the founding of many so-called patriotic societies, such as the Sons (now defunct) and the Daughters (still active) of the American Revolution, the Colonial Dames of America, and the Society of Mayflower Descendants. This new interest in genealogy was due partly to the Centennial itself, and partly to efforts by the established middle class to distance itself from the increasing number of new, predominantly non-British immigrants. This process of cultural authentification was fortified by furnishing homes in the so-called Colonial style, thus underlining the link to the past. Like most invented traditions, the Colonial revival was also a reflection of its own time–the nineteenth century. Its visual taste was influenced by the then current English architectural fashion–Queen Anne–which had nothing to do with the Pilgrim Fathers, but whose cozy hominess appealed to a public sated by the extravagances of the Gilded Age.

Home: A short history of an idea, by Witold Rybczynski

Emily Gilmore belongs to Daughters of the American Revolution. She herself is clearly racist and her big, cold, Colonial home is an outworking of Emily herself.

In contrast we have Lorelai’s house, which we often see from the outside bathed in sunlight. The contrast between Emily’s house and Lorelai’s house is the archetypal cold colonial vs warm and sunny dichotomy. We are meant to feel at home in one and not in the other. The expectation that warm, cosy houses are full of food is overturned by the writer in (what I believe) to be an attempt at subverting the patriarchal expectation that women must be good at cooking.

In Emily’s house there is plenty of light, but it comes from those Gothic chandeliers and expensive mood lighting, not through the windows. This house is an island unto itself. Nothing’s coming in that Emily hasn’t put there her very self.

What is also striking about these handsome interiors is the absence of so many of the things that characterize modern life. We look in vain for clock-radios, electric hair dryers, or video games. There are pipe racks and humidors in the bedrooms, but no cordless telephones, no televisions. There may be snowshoes banging on the cabin wall, but there are no snowmobile boots by the door.

Home: A short history of an idea, by Witold Rybczynski

CASE STUDY: THE HOUSES OF NASHVILLE

The difference between the ‘cosy, colonial’ house and the cold, inhospitable house made mostly of glass is exemplified beautifully in Nashville, TV series, written by Callie Khouri.

(I’ve only seen the first two seasons, so my commentary is only on that…)

JULIETTE BARNES

Here’s Juliette’s house from the outside: square, modern, white. Perfectly manicured. Juliette is nouveau riche but she grew up in a trailer with an exploitative mother. This ghost continues to haunt her into the present.

Though these windows are covered in net curtains (probably to diffuse the light for the sake of filming), it’s significant that Juliette lives in a glass house. The whole world is watching her every move. There is no real boundary between Juliette and the public.

Juliette herself is small in stature, but her house is enormous. This juxtaposition emphasises her loneliness.

Juliette is young and so her tastes are modern.

This house is basically a modern castle. Where else do we find castles? In gothic fiction. These traditional castles have dungeons and hidden passages and are surrounded by gloomy forests and this isn’t that kind of castle, but it is still almost part of the female gothic tradition, in which the character inhabiting the space graduates from adolescence to maturity.

The Female Gothic permitted the introduction of feminine societal and sexual desires into Gothic texts. It has been said that medieval society, on which some Gothic texts are based, granted women writers the opportunity to attribute “features of the mode [of Gothicism] as the result of the suppression of female sexuality, or else as a challenge to the gender hierarchy and values of a male-dominated culture”.

Does that sound like Juliette? Another feature of the female gothic is the threatening control of a male antagonist.

The heroine possesses the romantic temperament that perceives strangeness where others see none. Her sensibility, therefore, prevents her from knowing that her true plight is her condition, the disability of being female.

Juliette is definitely vilified due to her gender — the way she is set upon by the public when she is implicated in the Wentworth break-up is one example.

RAYNA JAMES

Rayna has plenty of money, though it’s clear from the pilot that she is ‘cash poor’. She has married a ‘trust fund boy’ and lives in a house typical of the one percent. Exactly the sort of house we’d expect a middle-aged country singer from Nashville to live in. But this is a warm house compared to the white cube owned by Juliette.

Inside Rayna’s house we see Maddie’s bedroom. Teenage bedrooms are easy for set designers to get wrong — there’s too often an unlikely mixture of fan posters on the wall. But the set designers have avoided that altogether with Maddie by hanging up some artwork — perhaps her own as a child, which has been framed?

The Bluebird Café is another example of the ‘Warm House’, and the café, too, can be warm or terrifying.

DEACON’S SUBURBAN COTTAGE

Deacon is your archetypal difficult man, the silent type with addiction issues but brimming with talent. Deacon, we are led to believe, would rather be living in the woods, just him and his guitar. This personality type — reflected in his niece — explains the backstory of why he never sought fame when he was younger, riding on the coat tails of Rayna.

SCARLETT’S HOUSE

Okay so two young men lived here too, but I only ever see Scarlett cleaning the kitchen, so I’m calling the sunny, warm and retro-vibe kitchen an outworking of her.

RELATED

How much would fictional houses cost in real life? from CNN Style

Houses which inspired writers from Poets and Writers

At TV Tropes:

- Big Fancy House

- Big Fancy Castle

- Cool House

- Old Dark House

- Horrible Housing

- Cardboard Box Home

- Bad Bedroom, Bad Life

- Lonely Bachelor Pad

- Non-residential Residence

FURTHER READING

Unique 143-year-old listed home in concrete and glass seeks new family

FURTHER READING

The Great Indoors: The Surprising Science of How Buildings Shape Our Behavior, Health, and Happiness

Modern humans are an indoor species. We spend 90 percent of our time inside, shuttling between homes and offices, schools and stores, restaurants and gyms. And yet, in many ways, the indoor world remains unexplored territory. For all the time we spend inside buildings, we rarely stop to consider: How do these spaces affect our mental and physical well-being? Our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors? Our productivity, performance, and relationships?

In this wide-ranging, character-driven book, science journalist Emily Anthes takes us on an adventure into the buildings in which we spend our days, exploring the profound, and sometimes unexpected, ways that they shape our lives. Drawing on cutting-edge research, she probes the pain-killing power of a well-placed window and examines how the right office layout can expand our social networks. She investigates how room temperature regulates our cognitive performance, how the microbes hiding in our homes influence our immune systems, and how cafeteria design affects what―and how much―we eat.

Along the way, Anthes takes readers into an operating room designed to minimize medical errors, a school designed to boost students’ physical fitness, and a prison designed to support inmates’ psychological needs. And she previews the homes of the future, from the high-tech houses that could monitor our health to the 3D-printed structures that might allow us to live on the Moon.

The Great Indoors: The Surprising Science of How Buildings Shape Our Behavior, Health, and Happiness provides a fresh perspective on our most familiar surroundings and a new understanding of the power of architecture and design. It’s an argument for thoughtful interventions into the built environment and a story about how to build a better world―one room at a time.

interview at New Books Network

Every Home a Fortress: Cold War Fatherhood and the Family Fallout Shelter

In Every Home a Fortress: Cold War Fatherhood and the Family Fallout Shelter (University of Massachusetts Press, 2020), Thomas Bishop details the remarkable cultural history and personal stories behind an iconic figure of Cold War masculinity—the fallout shelter father, who, with spade in hand and the canned goods he has amassed, sought to save his family from atomic warfare. Putting policy documents and presidential addresses into conversation with previously unmined personal letters, diaries, local media coverage, and antinuclear ephemera, Bishop demonstrates that the nuclear crisis years of 1957 to 1963 were not just pivotal for the history of international relations but were also a transitional moment in the social histories of the white middle class and American fatherhood. During this era, public concerns surrounding civil defense shaped private family conversations, and the fallout shelter emerged as a site at which ideas of nationhood, national security, and masculinity collided with the complex reality of trying to raise and protect a family in the nuclear age.

interview at New Books Network

House Lessons: Renovating a Life

From the New York Times, best selling author Erica Bauermeister comes House Lessons: Renovating a Life (Sasquatch Books, 2020). This memoir is about the power of home, and the transformative act of restoring one house in particular. In this mesmerizing memoir-in-essays, Erica Bauermeister renovates a trash-filled house in eccentric Port Townsend, Washington, and in the process takes readers on a journey to discover the ways our spaces subliminally affect us. A personal, accessible, and literary exploration of the psychology of architecture, as well as a loving tribute to the connections we forge with the homes we care for and live in, this book is designed for anyone who’s ever fallen head over heels for a house. It is also a story of a marriage, of family, and of the kind of roots that settle deep into your heart. Discover what happens when a house has its own lessons to teach in this moving and insightful memoir that ultimately shows us how to make our own homes (and lives) better.

interview at New Books Network