In juxtaposing a series of pictures in order to imply the sequence of a story, picture-book artists act much as filmmakers do. Andre Bazin [film critic] suggests that montage, assumed by many to be the essence of film art, is “the creation of a sense of meaning not proper to the images themselves but derived exclusively from their juxtaposition”. In films, the arrangement of a succession of shots provides the events depicted with their significance; not surprisingly, filmmakers often prepare themselves for shooting by using storyboards, sequential drawings of the various shots they intend to make of the scenes they will film that look much like picture books.

Perry Nodelman, Words About Pictures

- EYECANDY is a visual technique community with a website exemplifying various visual techniques.

- Movie vocabulary used by directors from Wordnik

- 30 Camera Shots Every Film Fan Should Know, and also these ‘shots’ come in handy when talking about the art of picture books, I might add. From Filmmaker IQ

- Infographic shows the most common problems with 300 screenplays, from io9

- Hayao Miyazaki (of Studio Ghibli) offers six filmmaking tips which could equally apply to the making of picture books, from Film School Rejects

- Seven Teaching Resources on Film Literacy from Edutopia

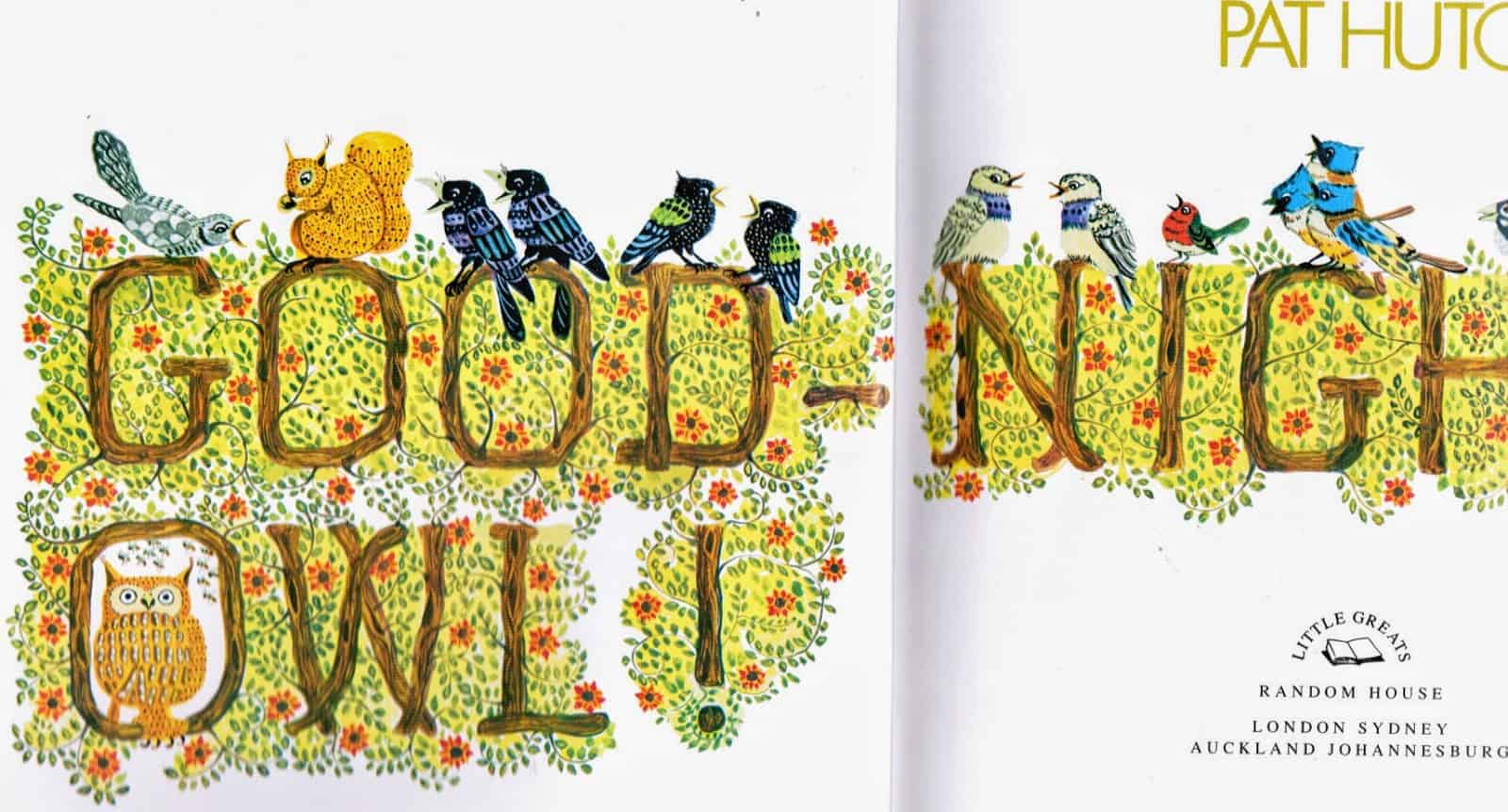

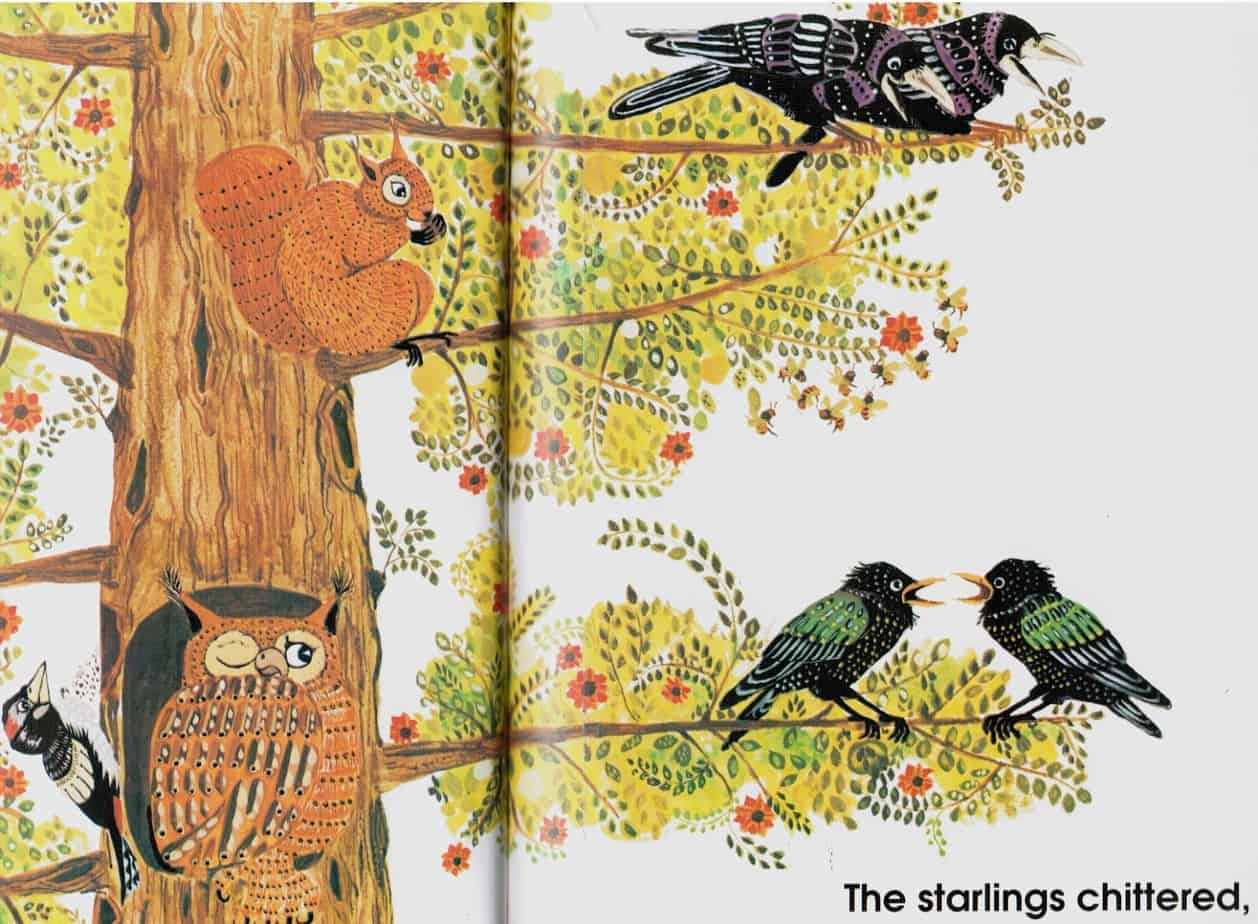

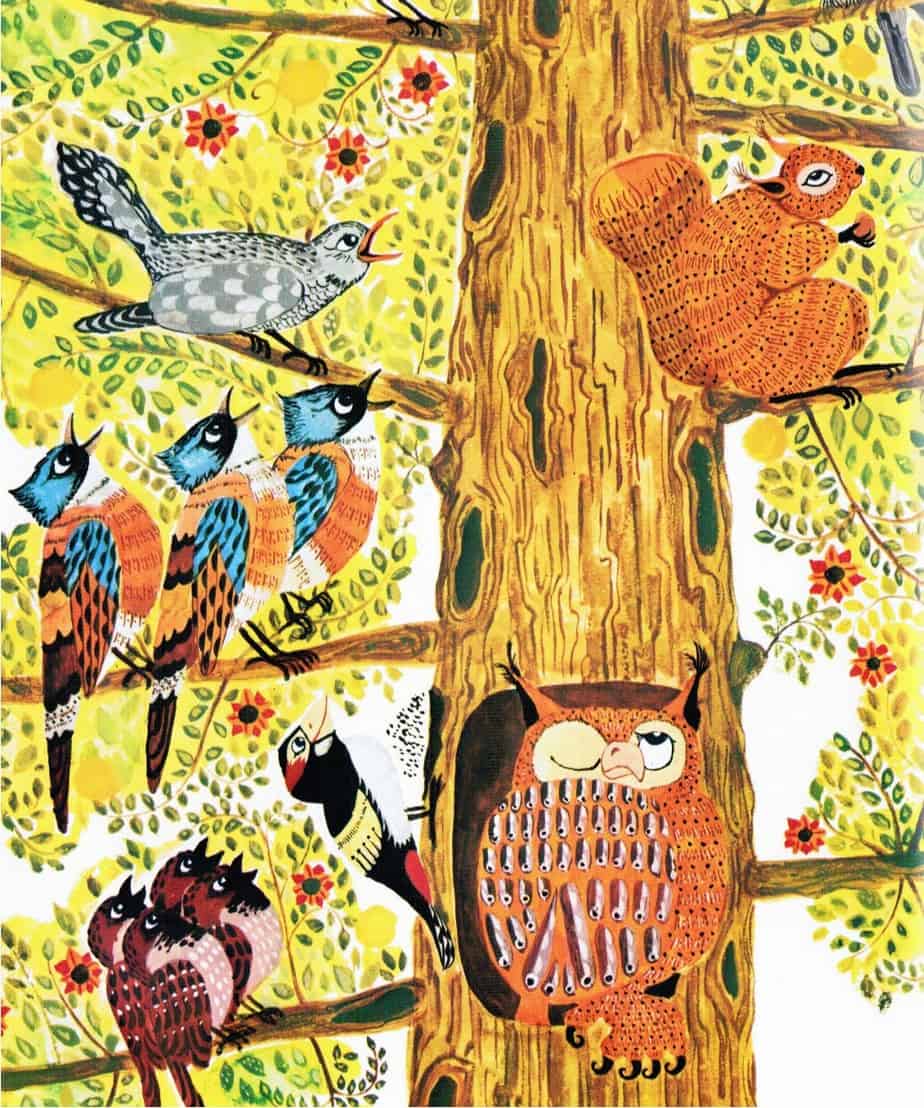

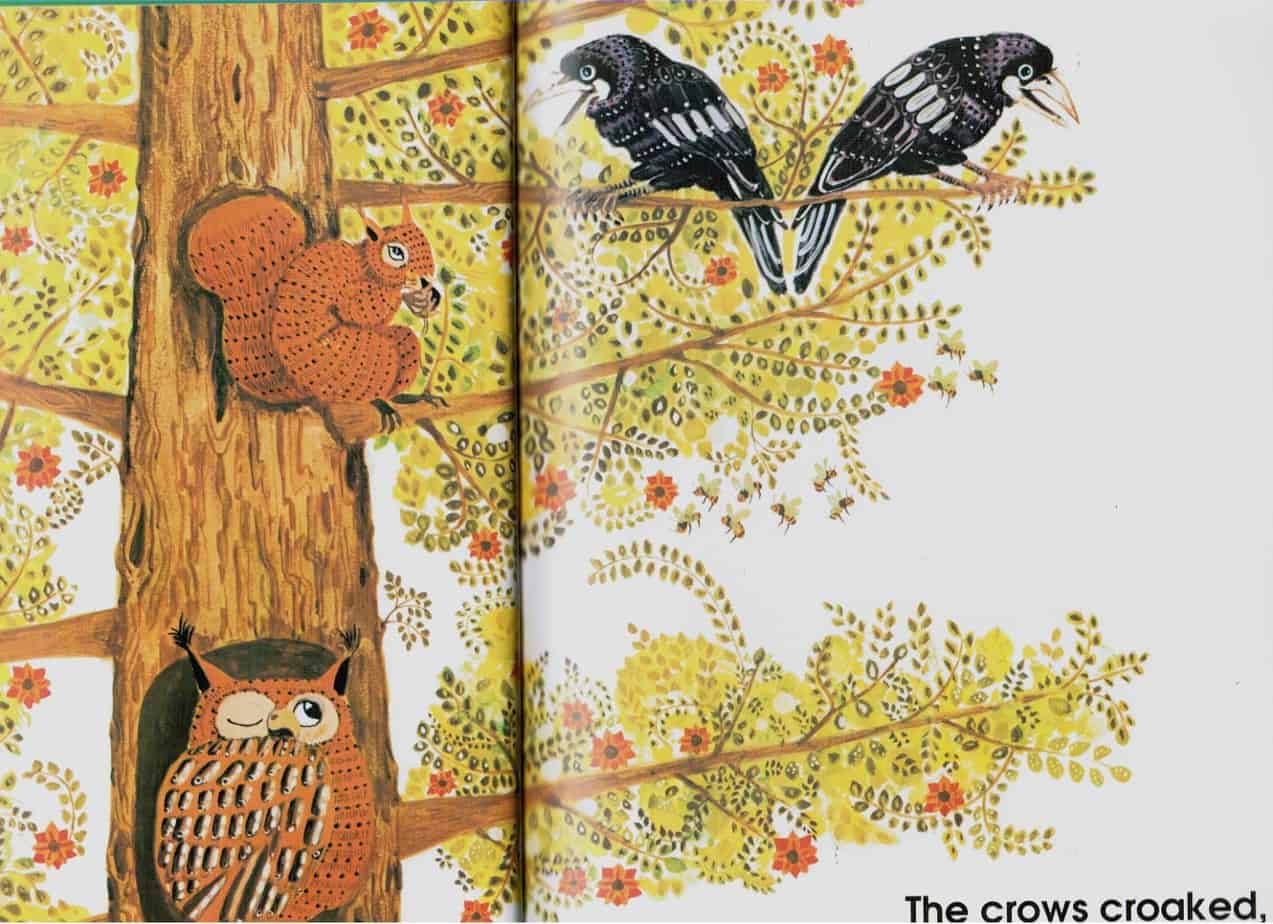

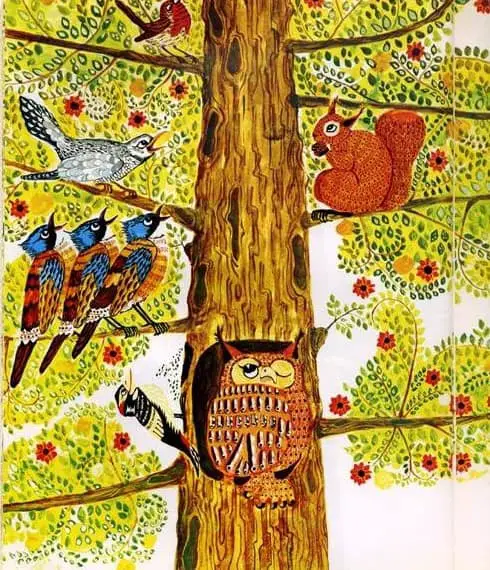

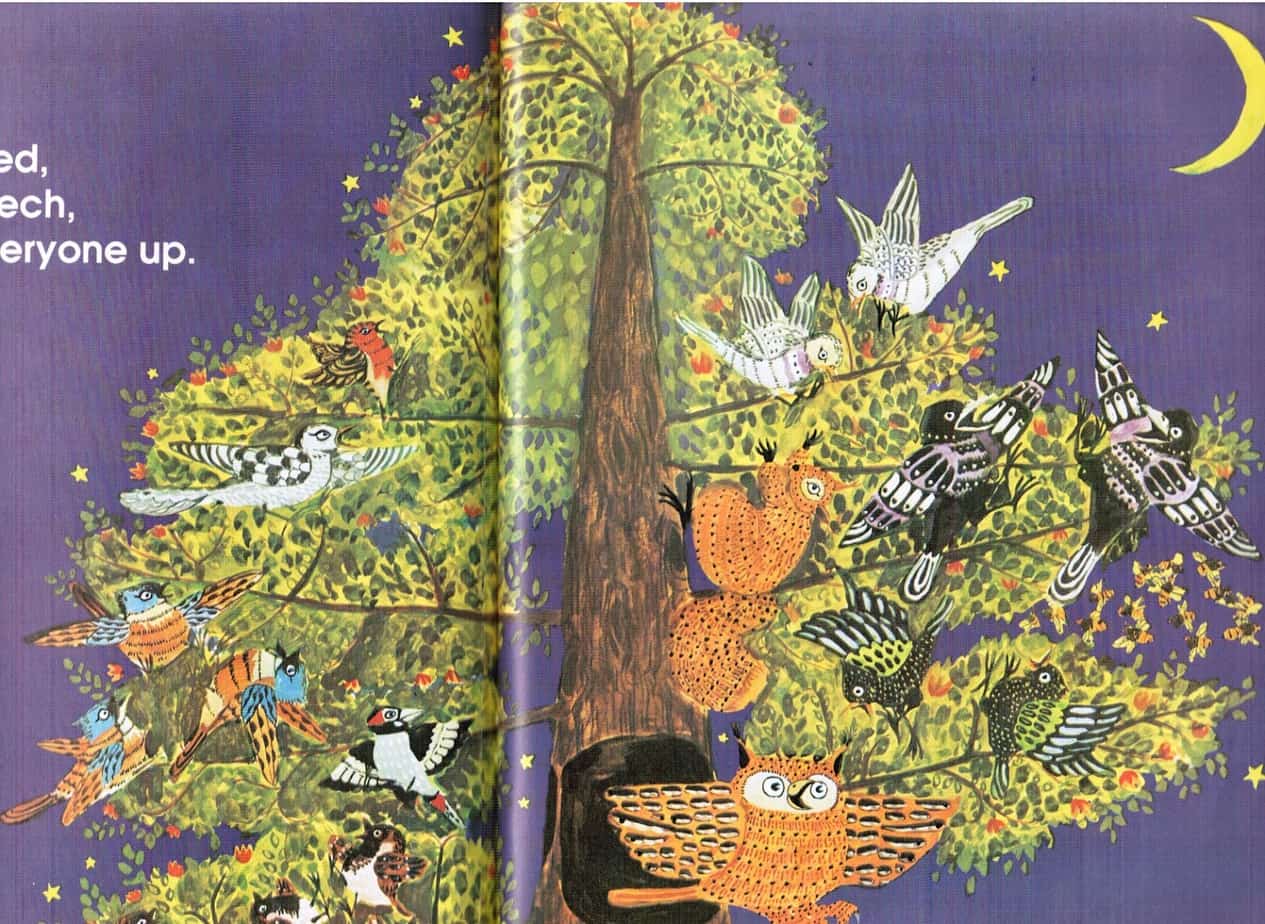

- Form Cuts (or Match Cuts) are a film technique quite often used in picture books, for example in The Garden of Abdul Gasazi by Chris Van Allsburgh (round back of old sofa, curved bridge) Nodelman notes that Pat Hutchins depicts the same tree in each picture of Goodnight, Owl, but adds a new set of birds each time. Form cuts are good for making the differences in each picture really clear — the fixed position of objects anchors changes that are significant to the story.

- The dynamic frame is even more common in picture books than it is in film. Filmmakers who use dynamic frame change the size and shape of the image on the screen. It has gone out of fashion in filmmaking. You still see it in contemporary films when shooting through doorways, for example, so hat the lighted area seen by the audience is shaped, even though the shape of the screen itself doesn’t change. For an example of this technique in a picture book see Hyman’s Sleeping Beauty, with views through the arches. In Where The Wild Things Are, the pictures gradually grow in size and then become smaller.

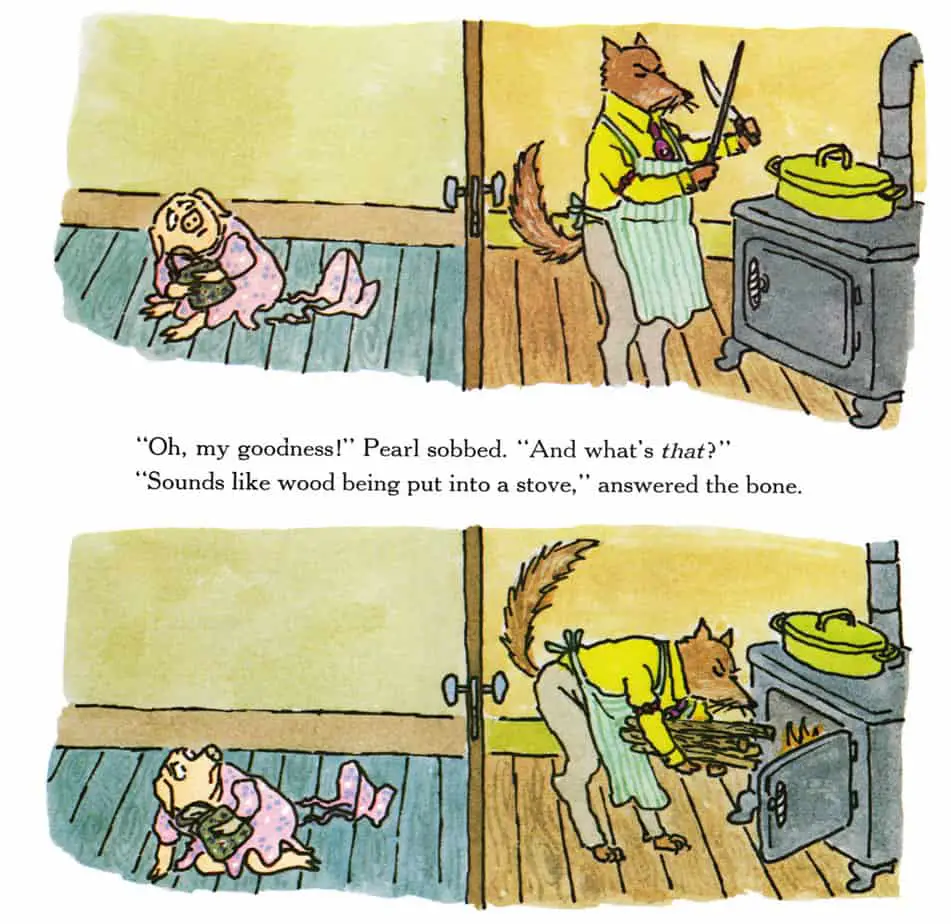

The change in frame sizes is not annoying in picturebooks as it can be in films — instead, this is an accepted picturebook convention. It’s fairly common to place more pictures on a single page when there’s a lot going on.

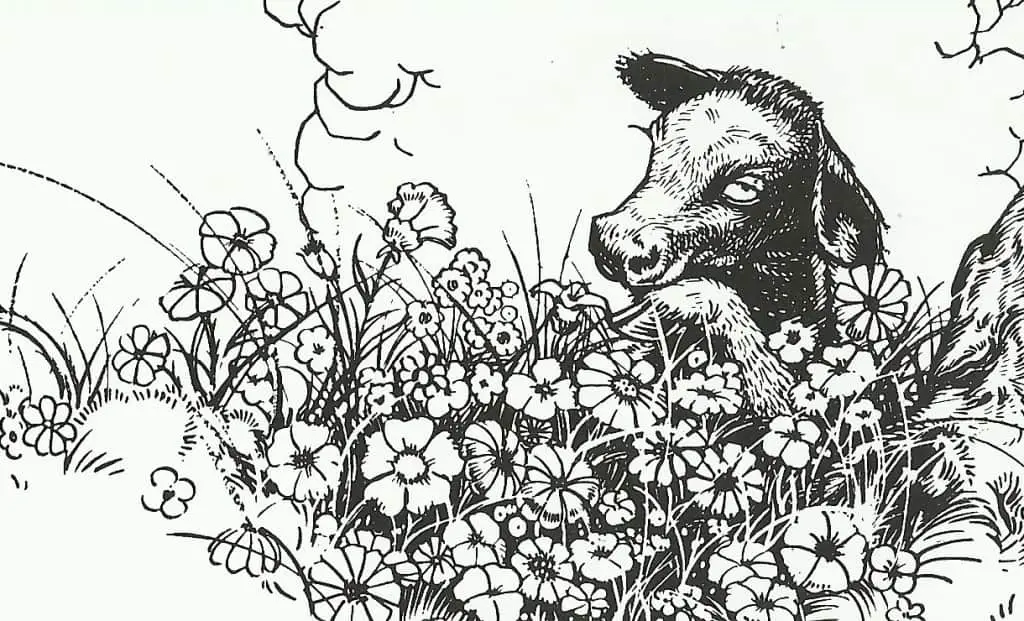

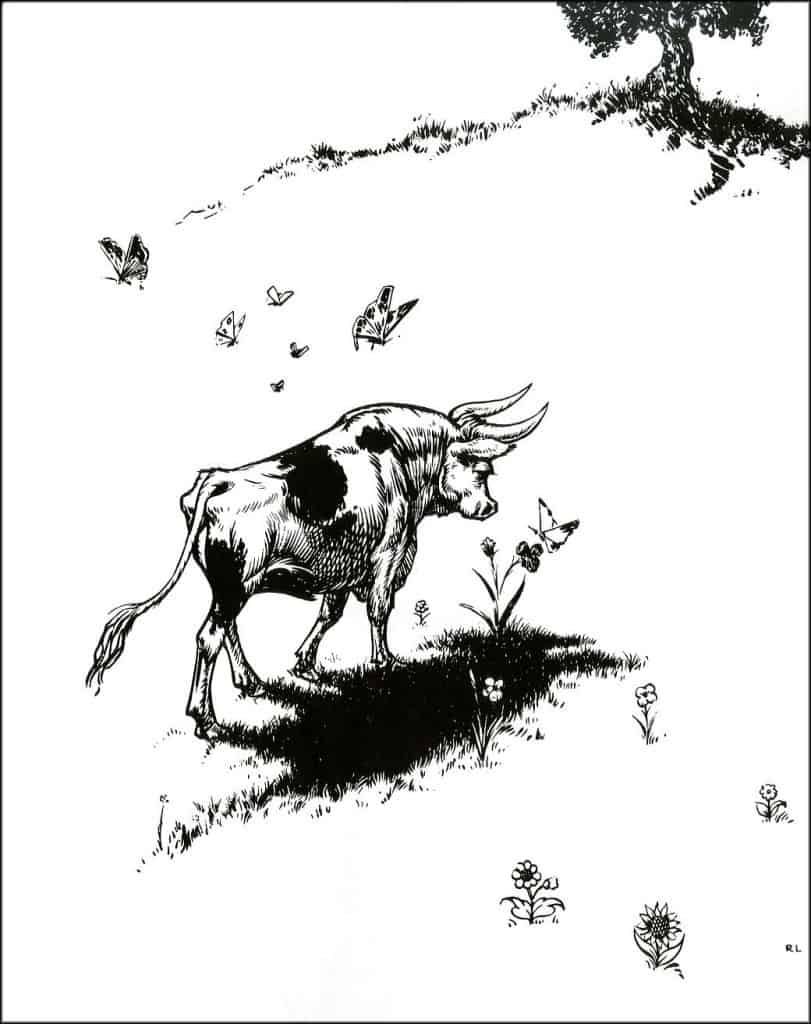

- Robert Lawson’s The Story of Ferdinand is one of the few picture books to use many of the very common film shots. Most picture books make heavy use of medium close ups.

Ferdinand is only one of many picture books that, in its choice of vantage points, its quick cuts, its total flexibility, would have been unthinkable before motion pictures.

Barbara Bader

ONE BIG DIFFERENCE BETWEEN FILM AND PICTURE BOOKS

For all the similarities between motion pictures and modern picture books, Perry Nodelman notes one big difference:

Even when picture-book illustrators do vary from eye-level middle-distance or long shots, the effect of the variation is not cinematic. In films, we see the same scene from a variety of angles; in most picture books, indeed even in Ferdinand, every picture marks a different point in the story, in effect a different episode….almost every picture in most books represents a different scene. The whole point of film montage is that we come to understand action by means of the various ways the action has been broken down into smaller bits. But that does not happen in picture books. That, I believe, is the major difference between the depiction of action in picture-book narrative and in all other sorts of visual media; we see only a few carefully selected moments out of numerous possibilities, whereas on film we see many different ones of those possibilities, and on stage in any given scene, we see all of them. Because picture-book artists are restricted in the number of moments they can depict—usually it is fewer than fifteen, including the title page— they must choose their moments carefully and vary them more than do film-makers. If the angles remain the same, the actions depicted are always different; Max may make mischief in two different pictures, but they are two different sorts of mischief…Comic books can be located somewhere between picture books and films; they almost always show many different pictures of the same sequence of actions, and they tend to make use of every conceivable sort of shot, every possible angle…When picture books show more shots, they tend to take on the conventions of comic books and films.

Words About Pictures

THE FIVE DIFFERENT SYSTEMS OF SIGNIFICATION

Before reading the paragraph about the work of Christian Metz below, know that semiology means ‘semiotics’ (the study of signs and symbols and their use or interpretation).

In a discussion of the semiology of film, Christian Metz suggests that films demand from their viewer knowledge of at least five different systems of signification, most of which can also be found in slightly different ways in picture books:

culturebound patterns of visual and auditory perception (such as knowing how to understand a perspective through drawing)

recognition of the objects shown on screen (labelling)

knowledge of their cultural significance (such as knowing that black clothing stands for mourning)

narrative structures (knowledge of types of stories and how they usually work out)

and purely cinematic means of implying significance, such as music and montage.

Metz suggests that each complete film, “relying on all these codes, plays them one against the other, eventually arriving at its own individual system, its ultimate (or first?) principle of unification and intelligibility.” In other words, filmmakers make use of the differences between various means of communication in the knowledge that each medium they bring into play will finally merely be part of the whole along with all the others; consequently, they deliberately (or sometimes, given the varying narrative capabilities of different media, inevitably) make each incomplete so that it can indeed be part of a whole and so that the meaning will be communicated by the whole and not any specific part of the whole.

What the clothing and gesture do not reveal to us, the music or the narrative structure might; and what the clothing and the music communicate separately is different from what they communicate together.

So each medium that filmmakers use always communicates different information differently, and all of them express their fullest meaning in terms of the ironies inherent in their differences from each other.

Words About Pictures

Art History for Filmmakers: The Art of Visual Storytelling

Gillian McIver‘s Art History for Filmmakers: The Art of Visual Storytelling (Bloomsbury, 2016) is a ground-breaking book that illustrates the relationships among the histories of painting and cinema. Of interest to established filmmakers, students of film, and those engaged with the history of art and visual storytelling overall, Art History for Filmmakers is a comprehensive study of the ways in which painting and film influence one another in terms of light, composition, subject matter, theme and style. McIver presents examples of the impact of painting from the antique to the modern upon the work of filmmakers Peter Greenaway, Martin Scorcese, Peter Webber, Stan Douglas, Guillermo de Toro, John Ford and others. Through an array of color images, McIver demonstrates how Dutch Baroque, Realism, Surrealism, Expressionism, Minimalism and other art historical movements shape story and appearance in film. Art History for Filmmakers also provokes consideration of the ways the language of film brings idea and form to painting. Chapters are followed by creative exercises and discussion questions that further understanding of the material.

New Books Network