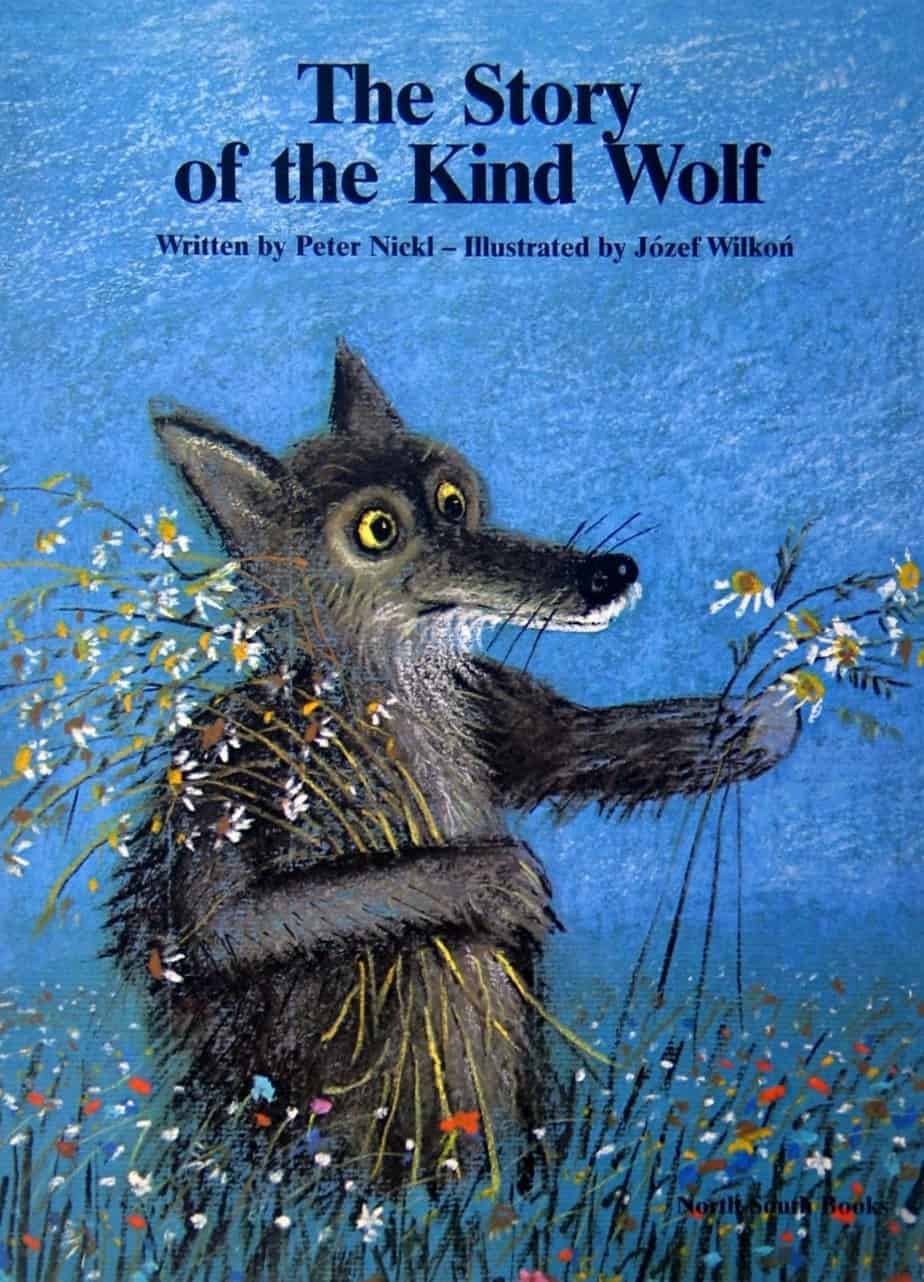

“The Story Of The Kind Wolf” is a 1982 picture book by Jozef Wilkon, illustrated by Peter Nickl and translated into English by Marion Koenig. The story is now out of print and hard to find.

This is a Tawny Scrawny Lion plot, and very much of its time. This was the era of the vegetarian wild animal in picture books. Ecologists have long understood the importance of meat in the diet of a carnivore, and now understand how a single pack of wolves are vital to keeping an ecosystem in balance. But according to these Tawny-Scrawny-Lion plots, an ideal wilderness is one in which carnivorous animals become vegetarian. If this happened in reality, rabbits would ruin the landscape for everyone. Rabbits have ruined Australia, a topic covered metaphorically by Shaun Tan and John Marsden in The Rabbits.

Like John Brown, Rose and the Midnight Cat, this story definitely has a subtextual layer to it. Unlike John Brown, Rose and the Midnight Cat, I’m not sure it’s intended? For me, this is a subtexually a Jekyll and Hyde story, in which the fox functions symbolically as the wolf’s extreme hunger.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “THE STORY OF THE KIND WOLF”

PARATEXT

The pastel illustrations call to mind the work of Yuri Norsteyn, who created Hedgehog in the Fog and other hedgehog stories in the same series.

Everyone has heard people say someone is as fierce as a wolf or as wise as an owl. In The Story of the Kind Wolf, children find that stereotypes are not always correct.

MARKETING COPY

A gentled wolf returns to the forest of his birth to practice medicine, but a silly owl warns sick animals to stay away

MARKETING COPY

SHORTCOMING

According to the story, the wolf’s shortcoming is that he is mean to other animals by eating them. Humans must also wrestle with the (common) desire to eat meat juxtaposed against the ethical issues around doing so. Wolves, of course, have no such qualms. The wolf in this story is therefore heavily anthropomorphised.

The narratees of this story are also presumed to have a moral shortcoming, and we are directly addressed at the opening:

But not all wolves are fierce, any more than all foxes are sly or all owls wise. It is as silly as saying all girls are pretty or all boys brave.

The author’s intention is clear, but other stories do a much better job of asking readers to avoid stereotypes and prejudice, on the assumption that prejudging the temperaments of wild animals is morally wrong.

In this particular story, children are encouraged not to prejudge the ferocity of wolves. This is clearly a story aimed at city and suburban kids. If I lived, say, in rural Alaska, I would be teaching my offspring never to trust a wolf, or indeed any wild dog which may be part wolf. I’m reminded of the Peppa Pig episode, banned in Australia, which urges children not to be afraid of spiders. Here in Australia, spiders can kill a child. Messages encouraging children ‘not to be afraid of wild and dangerous creatures’ are very much targeted at a readership who will never actually meet a wild and dangerous creatures.

Second, the author compares animal stereotypes (from fables) to gender stereotyping. This is a terrible analogy, in part because animals do not have gender, only sex. Worse, the unintended consequence of reminding readers that not all girls are pretty and not all boys are brave is this: readers are reminded that girls are supposed to be pretty and boys are supposed to be brave. This is a close cousin to the rhetorical device known as paralepsis. “I know who farted but I wouldn’t want to embarrass Charles.”

DESIRE

Despite being a carnivore, with a digestive system to match, the wolf wants to be accepted as a member of the forest community.

OPPONENT

Since the wolf wants to eat, his opponents are the creatures he’d like to be friends with. He’s torn though, because he wants to eat. He wants to eat his friends.

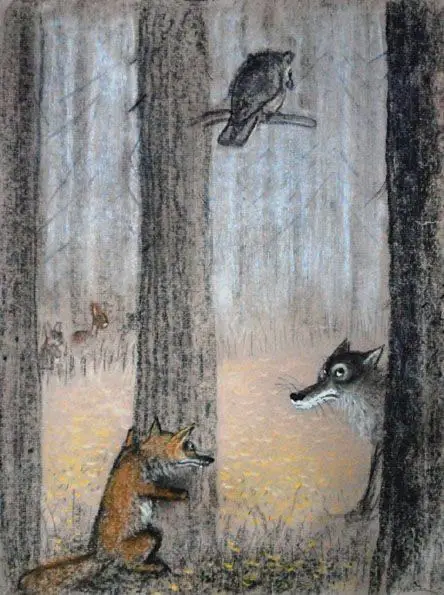

Basically, the fox steps in as a symbol of the wolf’s baser instinct. See him below, hiding behind the tree trunk? As soon as the wolf leaves the area, the fox is going to jump in to gobble up all the animals who were previously being cautious. The wolf’s ferociousness was obvious, but for some reason, the animals in this story have not learned to be afraid of the sly fox.

PLAN

I see the influence of new age thinking, of which modern Wicca is a part. Like a benevolent forest witch, the wolf decides to study herbs and plants for their medicinal purposes. He’ll become a forest doctor. Instead of eating his friends, he’ll help them.

To do this, he moves into ‘a cave, a long way to the south’. The cave is the place where characters from fable and folklore go to have a good hard look at themselves. Note that the wolf travels south. (You may be interested in these thoughts on the symbolism of cardinal direction.)

THE BIG STRUGGLE

What is the difference between the fox and the wolf? Nothing, in my opinion. According to my reading, images of the fox gobbling up the forest creatures depict the wolf succumbing to hunger.

To support my theory, the illustration of the canine with the creature in its mouth is partially obscured by mist. The text, too, seems to conflate the wolf and the fox. Observations come to us via the silly owl, who butchers his aphorisms (in a way I can’t quite fathom — is this a translation issue?).

Once again the owl flew off to warn the animals. “Beware the wolf in sheep’s clothing!” he hooted. “Troubles never come singingly! as the saying goes. Beware! Beware!”

“Beware of the wolf?” said the fox to a mouse, and when she began to run he gobbled her up.

“A wolf may lose his teeth but never his nature,” observed the owl.

“How true,” said the fox, and looked greedily at a moorhen.

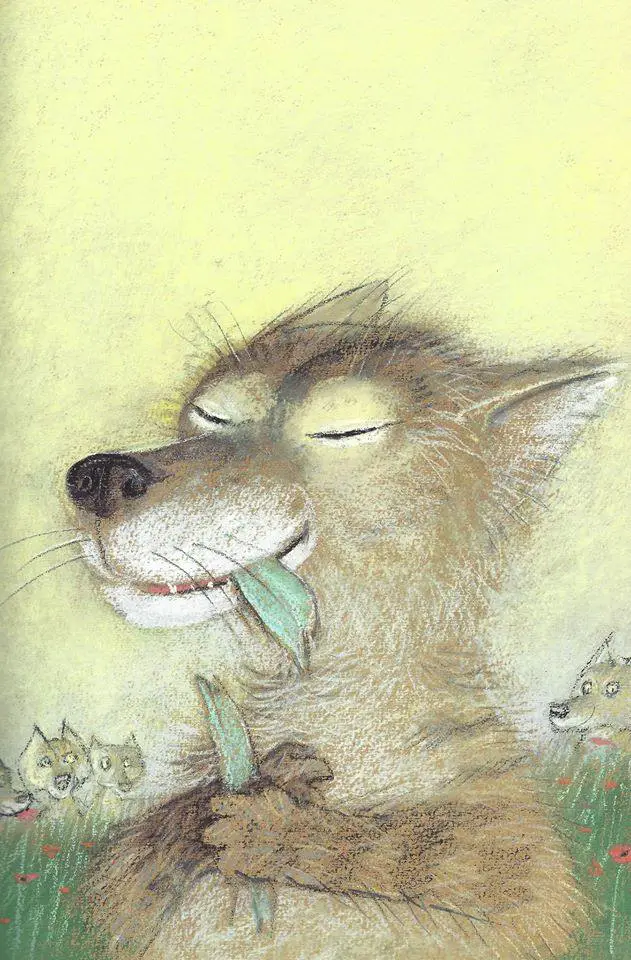

Unlike in The Tawny Scrawny Lion, the author of this picture book is realistic about the canine’s baser nature. Despite a wild canine’s best intentions, his lizard brain kicks in and he eats someone. We actually see the poor creature hanging out of the fox’s mouth.

The “fox” eats too many animals and gets a sore stomach. That’s the surface level interpretation. My subtextual interpretation: This fox-like metaphor of the wolf’s hunger has a sore stomach because he is… terribly, unbearably hungry!

The irony of this picture book is that despite being a gentle, pro-vegetarian story about friendship and acceptance, the violence is right there on the page. Again, this is the close cousin of paralepsis, because if storytellers are trying to leave it out, they must show it before leaving it out, which means it has to be on the page. And if it’s not on the page, it’s off the page… which any kcosmWhat Is Cosmic Horror? afficiado will tell you, is worse.

If you think my intepretation of this story goes deeper than it should, check out the following consumer review:

The story has page after page of animals killing and ‘gobbling’ each other up. Great illustration of a fox with a mouse in its mouth. The wolf takes the advice of an owl and goes from the forest to find a new way of life. While he’s away, the story tells of a bitterly cold winter and animals becoming desperate with the cold and hunger. The wolf turns into a vegetarian and turns all the little animals in the forest to fruit and vegetables instead of meat. Who do you think is behind this book? I gave it 1 star because -10 was not available. Thank goodness I read this book before reading it to my grandchildren, they would have had nightmares for weeks.

What? Well, if we start with the scientific fact preposition that forest canines are gonna need to eat meat, we need to do a bit of mental gymnastics, right? Now I’m thinking the VEGETABLES and FRUIT are ACTUALLY forest animals! The wolf (and later the fox) have let themselves get so starving, they now see cute little animals and imagine it as vegetation!

Bear in mind, the vast majority of the consumer reviews go more like this one:

One of the loveliest children books I know. Every child should be able to enjoy reading it. The illustrations are beautiful!

ANAGNORISIS

In many stories with anthropomorphised animals, the animal reaches peak mastery of its baser instincts when it starts wearing human clothing or using human implements. In this case, we’ll know the character arc of the wolf is complete when he returns home from the south holding a suitcase. (We are told several times he has a suitcase, but he’s not carrying it, fyi.)

Wolf finds the smallest, cutest looking little rabbit and saves this rabbit from the cold by taking him home and tucking him into his own “bed”. This inspires an “Aww!”

Illustrator Jozef Wilkon does a magnificent job of creating the softest, furriest little bunny. The pastel medium is good for this.

The wolf is so overwhelmed by the bunny’s cuteness that he is now finally fixed. He can no longer stomach meat. Rabbits equals meat, and we like rabbits.

(See also: my collection of rabbit illustrations.)

NEW SITUATION

Everyone lives happily ever after. At least, that’s the on-the-page version.

I’ve watched David Attenborough, so I happen to know a canine cannot live on fruit and carrots alone. I’m pretty sure the author tries to lampshade this scientific fact by telling us the fox slash wolf never learned to enjoy salads.

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

Anyone who knows the first thing about wolves (or anyone who’s ever been hungry) will know that the wolf’s lizard brain is about to kick in. When he reaches a certain point in his starvation he’s going on a munching rampage. Curtains for the cute little rabbit, and all the other morally upstanding plant eaters.

RESONANCE

Finally a story where wolves are not considered villains.

CONSUMER REVIEW

There are now many picture books which invert the fablistic villainy of wolves. Sometimes this is done for pure comedic purposes. Sometimes the storytellers are making use of irony. We don’t expect a wolf to be scared of the dark, for instance, so a little wolf who is scared of the dark reassures young readers that anyone can be afraid of anything.

The best of these ‘wolves as goodies’ stories have something useful to say, without inadvertently saying problematic things as well. (Subversion is not easy to pull off and easy to muck up.) My pick of the bunch is The Three Little Wolves and the Big Bad Pig by Eugene Trivizas, illustrated by Helen Oxenbury, which flips the message of earlier versions: One must always protect oneself from bad actors.

What I love about the message in Trivizas’s story is that we’re telling children the truth about bad people: No matter what we do to protect ourselves, if someone with bad intentions really wants to harm us, there is nothing we can do to stop them. This may not sound especially reassuring, but Trevizas manages to make it so, while encouraging readers away from victim blaming, or self-blaming when things in life inevitably go wrong.

I’m a fan of inversions in which children learn a truth about reality.

Wolf in the Snow is a wordless picture book by Matthew Cordell, also about the kindness of wolves. However, the attendant danger of wolves is never questioned.

All along, the owl — functioning as a kind of ironic narrator — never realised that there was a wolf AND a fox. The owl is therefore very silly. (The main irony for me is that I happen to think he is right — the wolf and fox are the same character, a la Jekyll and Hyde.) Other stories ironically overturn the Aesopian idea that owls are wise. Those have been around for a long time already — check out the pompous but very silly owl in Winnie The Pooh.