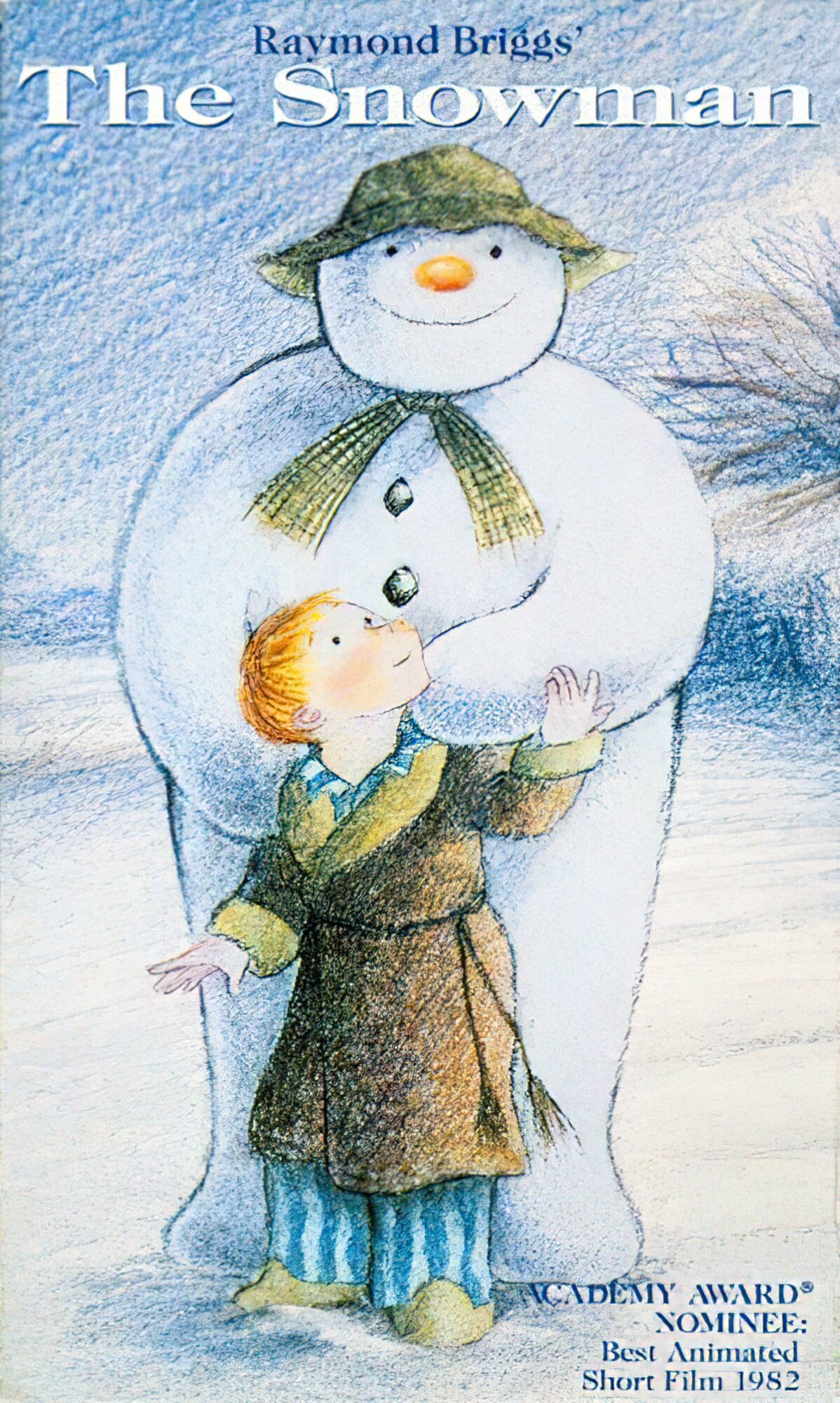

This month I’m blogging a series aimed at teaching kids how to structure a story. This seven-step structure works for all forms of narrative. It works for picture books, songs, commercials, films and novels. Today I take a close look at The Snowman by Raymond Briggs.

The Snowman is another carnivalesque tale, in which the ‘classic story structure’ needs a little reinterpretation.

STORY STRUCTURE OF THE SNOWMAN

WHO IS THE MAIN CHARACTER?

A boy. Illustrated in generic style, with dots for eyes, this boy is supposed to represent the Every Child. (White boys often do. Anything extra on the White boy is interpreted to be a meaningful embellishment.)

What is wrong with him?

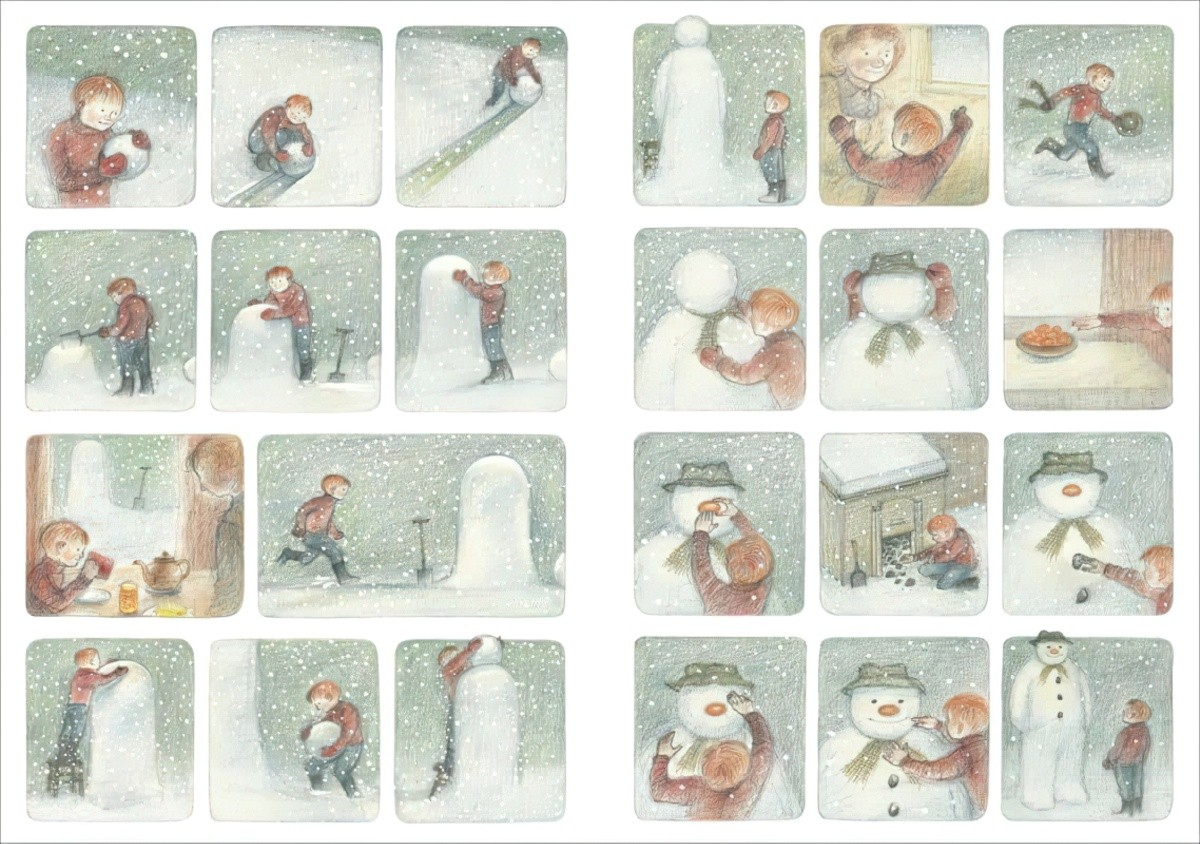

This is the question you should always ask of a main character. Unless there’s some psychological shortcoming, there’s no room for the character to grow. But sometimes, especially when you get a story about an Every Child, there’s nothing really wrong with them at all — we don’t know enough about them. Usually, in that case, their youth is their biggest problem. Childhood is restrictive. You don’t get to make your own decisions. The boy has to ask his mother before going out to build a snowman. He has to ask her again if he can dress the snowman in clothes. This is symbolic of how the boy lives his life — he craves more freedom, and he does get it, only for one night, and it may have been a dream.

WHAT DO THEY WANT?

Surface level desire: When he sees it is snowing outside he wants to build a snowman.

Deeper desire: As I mentioned above, he is restricted, so he craves freedom and adventure, and probably also a friend. He seems to be an only child, and in stories, only children are presumed to be lonely.

OPPONENT/MONSTER/BADDIE/ENEMY/FRENEMY

This is a carnivalesque story, so the character who turns up can exist at anywhere on the spectrum between opponent and best friend. The Cat In The Hat messes up the house, so is an opponent. But the Snowman in this tale is very much a friend.

Opposition in carnivalesque stories can come from the fact that the new friend has to eventually leave.

WHAT’S THE PLAN?

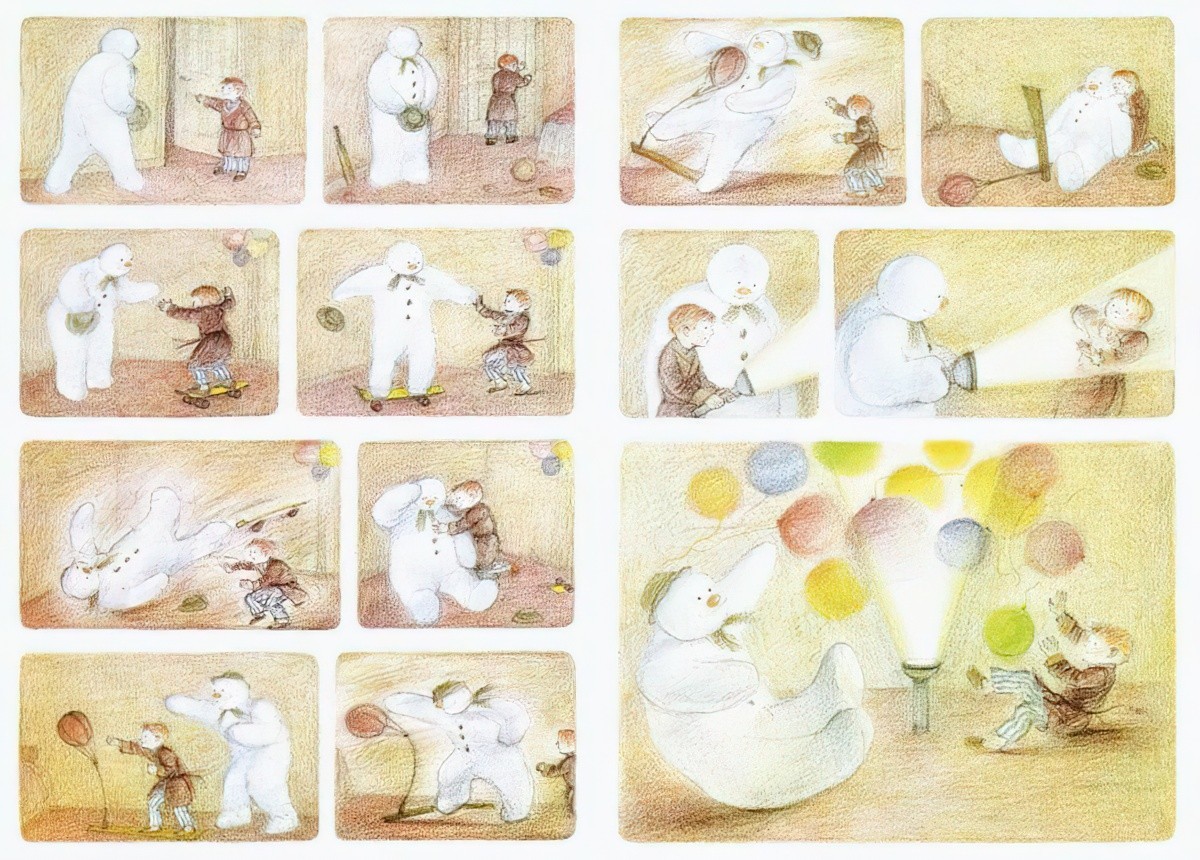

The boy introduces the Snowman to his world. He shows him the TV, how to punch the punching bag, and eventually they have a midnight feast together in the house. But this is not quite enough. The boy has already been shown to gaze wistfully out the window, so any lover of picture books should expect the child to go beyond the house. And so they do. They go flying.

BIG STRUGGLE

The ‘Big Battle’ in a carnivalesque tale is often no such thing. Consider it simply an ultimate escalation of fun. Just when you thought the characters couldn’t have any more fun (a midnight feast is pretty fun, right?) they go further.

In this story the boy flies through the air. They go on a ship across the sea. Consider this ultimate fun.

Flying is common and also highly symbolic in children’s literature. It can symbolise a bunch of different things. (Not just freedom.)

WHAT DOES THE CHARACTER LEARN?

I’ve heard it said that although children share the same emotions as adults, and we should respect that, the one thing children can’t relate to is nostalgia. Children have simply not spent enough time on earth to have seen good things (or bad things) come to an end, and though some things have ended (the toddler years etc) they haven’t yet had time to separate themselves from those experiences. It generally takes seven years before we can look back on a past event with a clear view.

But when the snowman melts, that’s pretty close to nostalgia. The boy has learnt that even wonderful things must come to an end, and there’s not a single thing you can do to stop the passage of time.

I think this is a book which appeals to adults just as much as it appeals to kids, if not more so. Adults can look at that snowman and think of all the wonderful things that have come and gone in their lives.

HOW WILL LIFE BE DIFFERENT FROM NOW ON?

The boy has now experienced something wonderful, even if it was all a dream. Now he knows what it is to fly through the air and have a companion, and not be the naive one in the partnership.

In these types of plots it’s not clear how life will be different exactly, but we trust it will be, simply because the boy has been touched by magic. You might call it ‘The Life-changing Power Of Magic’.

WONDERFULNESS OF THE SNOWMAN

[This story] is so tightly controlled in its cartoon strip visual images which resemble animation stills as to almost negate the interjection of the viewer’s imagination that the proponents of the wordless picture book so extol.

Sheila Egoff suggests in Thursday’s Child that [the reason why this story] is superior to other wordless picture books is because it contains 43 pictures. (This is far more than most.)

Perry Nodelman explains why The Snowman is such a successful wordless picture book:

The Snowman is tightly controlled in every respect. If it stands out from other wordless books, it does so because Briggs has chosen both a subject and a style that allow him to make full use of the potential of the difficult medium. The idea of a snowman coming to life is full of action, and Briggs chooses to show us the snowman and the boy doing things, and lots of different ones. We recognize what they are doing because these are familiar actions, the sorts of things we do every day in our own homes. They are funny, because the snowman does not know how to do them. But the soft warmth of the style demands empathy rather than the distance of comedy; we stand back from the snowman but we still like him. He is the ideal candidate for sympathy: he is incompetent not because he is vain or self-satisfied but because he is ignorant and ingenuous. We feel superior to him because he cannot do the things any child can do, things that the boy in the book does well. But because these are things any child can do, we feel concern for him. He demands the same response from viewers as Winnie the Pooh does from readers. That he should be capable of flying gracefully through the air after his endearing display of incompetence is an added bonus.

Words About Pictures, Perry Nodelman

For this same reason, viewers empathise more with the likes of Patrick in SpongeBob Squarepants more than Squidward, who is self-satisfied, pessimistic and vain. For more tricks on how to create empathetic characters, see this post.

NOTES ON THE ILLUSTRATIONS

There are three main ways illustrators can choose to depict people: minimalist, generic and naturalistic. I write more about that here.

Briggs has been working in children’s literature over decades and has developed a wide range of styles. He chooses either minimalist, generic or naturalistic depending on the story.

In other books, Raymond Briggs’ people lack delicacy/sensitivity, with jutting chins and prominent and scattered teeth. See Fungus the Bogeyman (1977) for an example of that style. Briggs also has an eccentric sensibility (see Father Christmas, 1973) and has even written a picture book for adults to demonstrate the horror of nuclear war (see When the Wind Blows, 1972).

Characters in The Snowman are drawn in generic, non-grotesque style, with dots for eyes. (Though even when we say ‘generic’, generic means obviously a White boy.)

Colour

There are two dominant colour palettes in The Snowman — cool palette, warm palette.

There are a lot of pictures of windows and doors in this picture book. Windows and doors are highly symbolic. In children’s illustrations they tend to show a child shut inside (against their will). The child will look outside, wondering what adventures could be had on the other side. Next we see them break free of their prison. But first comes the wondering and watching.

The final image could easily have taken up the entire last page, but instead Briggs chose to keep it very small. The boy’s world now seems very small again, now that his partner in imagination has melted away. This letterbox view is surrounded by a lot of white space, also known as ’emptiness’.

STORY SPECS OF THE SNOWMAN

I have heard the publishers of The Snowman love this book. They don’t have to do anything and it sells a reliable number of copies each and every year. Partly, this is because it’s a great Christmas book, and as you know, Christmas comes around each and every year. For most of the world (not here), Christmas and winter go together.

Made into a short film, released 1982. The boy who sang the song Walking In The Air (Aled Jones) grew up to present British home and garden shows, among other things.

WORDLESS PICTURE BOOKS

According to Barbara Bader, the first wordless picture book was What Whiskers Did by Ruth Carroll, published in 1932. Since then, many more wordless picture books have found popularity with young readers. Wordless books are truly interactive, because they require more of the reader. When a child and adult read a wordless book together, they’re probably doing a lot of talking about what’s going on.

I love wordless books because you can change the story just a bit every time you tell it.

a student quoted by Language of Literacy

COMPARE THE SNOWMAN WITH…

Another wordless picture book with a similarly affecting storyline is The Farmer and The Clown by Marla Frazee. In both stories an interesting stranger turns up, they have fun for a while and then there is sadness as the stranger must disappear.

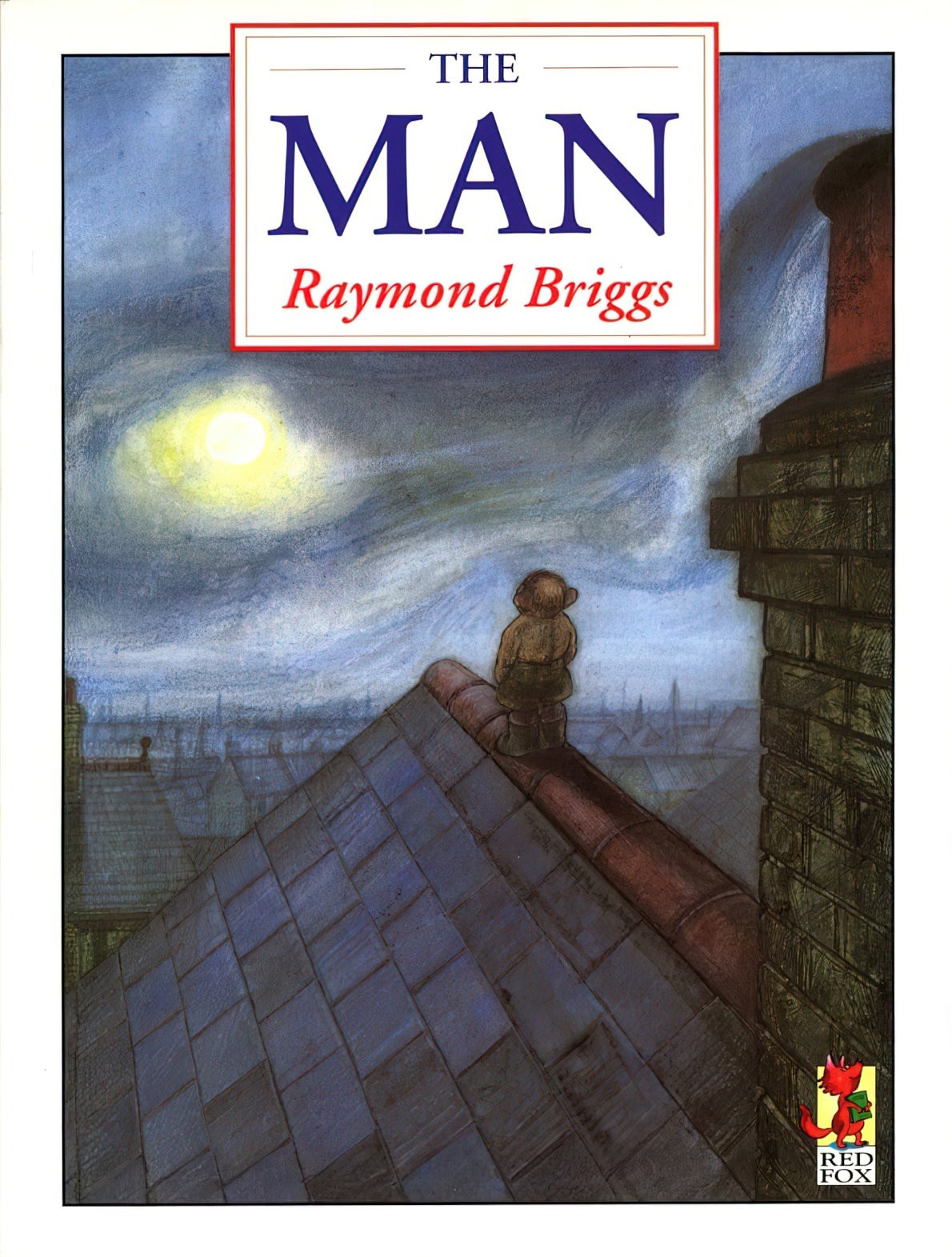

The Snowman is bittersweet. The Man, also by Briggs, shows Briggs is multi-talented. He has the power to tell a story, illustrate it well, and he can also be very funny in both the pictures and the words.

Snowmen are not always the kind, naive creatures as presented by Raymond Briggs. Sometimes Snowmen are evil.