**UPDATE LATE 2024**

After Alice Munro died, we learned about the real ‘open secrets’ (not so open to those of us not in the loop) which dominated the author’s life. We must now find a way to live with the reality that Munro’s work reads very differently after knowing certain decisions she made when faced with a moral dilemma.

For more information:

My stepfather sexually abused me when I was a child. My mother, Alice Munro, chose to stay with him from the Toronto Star

Before Alice Munro’s husband sexually abused his stepdaughter, he targeted another 9-year-old girl. ‘It was a textbook case of grooming’ from the Toronto Star

So, now what?

Various authors on CBC talk about what to do with the work of Alice Munro

And here is a brilliant, nuanced article by author Brandon Taylor at his Substack: what i’m doing about alice munro: why i hate art monster discourse

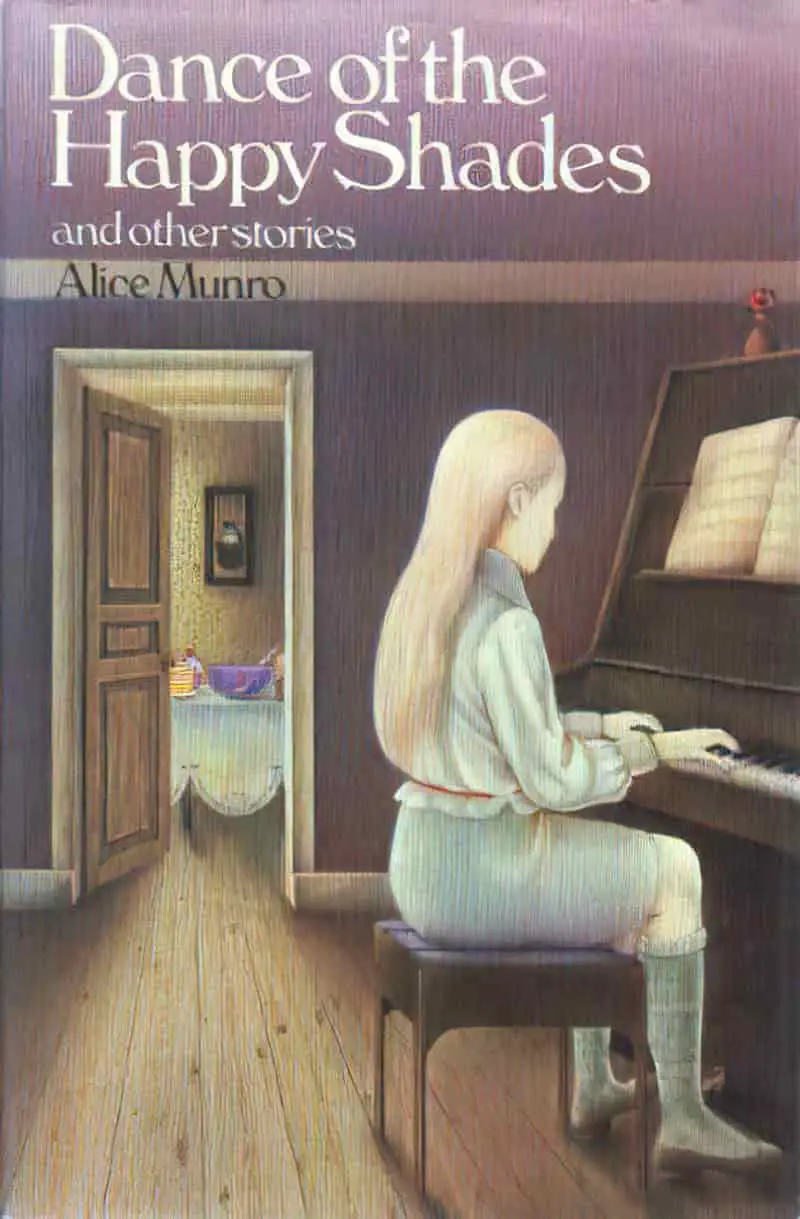

“The Shining Houses” is the second story of Alice Munro’s first short story collection, Dance of the Happy Shades, first published in 1968.

Neologism to watch out for: “competitive violence”, as in:

They worked with competitive violence and energy, all this being new to them; they were not men who made their livings by physical work. All day Saturday and Sunday they worked like this, so that in a year or two there should be green terraces, rock walls, shapely flower beds and ornamental shrubs.

“The Shining Houses” by Alice Munro

For me, this story feels close to home. Although it means extra commuting time, we purchased our family home in a rural, untidy area precisely to avoid draconian landscaping rules and ridiculous contractual agreements of the inner suburbs. We didn’t want rules about which material to use as a fence (wood! Not Colourbond!), or about the shape of our portico (not too similar to the portico of neighbours! but also not too different!), or about the aesthetics of our front yard (manicured! but also! aesthetically landscaped for frequent drought!).

Anyway, we’ve lived here happily for more than a decade, mowing our paddock grass but not bothering with the whipper snipping, instead waiting for sheep on the adjoining farm to stop by and do the job naturally. I enjoy waking up to the sound of bleating, and the sight of ewes and lambs shoving their heads through the fence, reaching for the long, juicy weeds growing up our side.

But then the farmer went and sold his land to developers. Our family hasn’t moved anywhere, but we no longer live in the relaxed little country town we chose for ourselves. We now live next to many new, tidy houses—”The Shining Houses”—with residents who bring their own ideas about what suburban life should look like, and what it takes to be a Good Neighbour. We “original villagers” think nothing of letting our perimeter weeds grow along fences which were never previously seen from the street. In contrast, many of our new neighbours think nothing of cranking up the leaf-blower on a Saturday morning, or mowing on a Sunday, or letting their dogs bark while they’re away at work during the day. Neither group is ‘right’, but the earlier residents prioritise a relaxed sort of peace and quiet. Newer residents prioritise appearance above all else. (As I type this, a nearby leaf blower is my soundtrack. There are no leaves.)

Although Alice Munro’s “The Shining Houses” was written in the 1960s, this story feels familiar.

WHAT HAPPENS IN THE SHINING HOUSES

In a new neighbourhood, many houses have been built next to an old one. The owner of the older house, Mrs. Fullerton, does not take care of her property to the extent that the owners of the new houses would like. This story starts out as a character study of Mrs. Fullerton through the eyes of a young mother called Mary, who takes a quiet interest in hearing people’s stories. Mary finds it easy to get Mrs. Fullerton talking about her life. Husbands come and go, but she prefers to stay in the same old house for continuity purposes, and also just in case the last husband (much younger than herself) decides to wander back one day after disappearing without notice.

But once the reader has a firm grasp on Mrs. Fullerton as a ‘full’ (rounded) character, the story turns into a character study of a community.

Annoyed with the eyesore and stench that is Mrs. Fullerton’s cottage industry farm, the young new professional residents band together to get rid of Mrs. Fullerton by making use of the law. Asked to sign a petition to build a laneway right through Mrs. Fullerton’s property, Mary is conflicted. These other new people are ‘good people’ who look after their neighbours and care about their neighbourhood. Still, she doesn’t feel Mrs. Fullerton should be pushed out.

In the end, the best Mary can do is to aim for ‘disaffected’.

MRS FULLERTON: MODERN WITCH

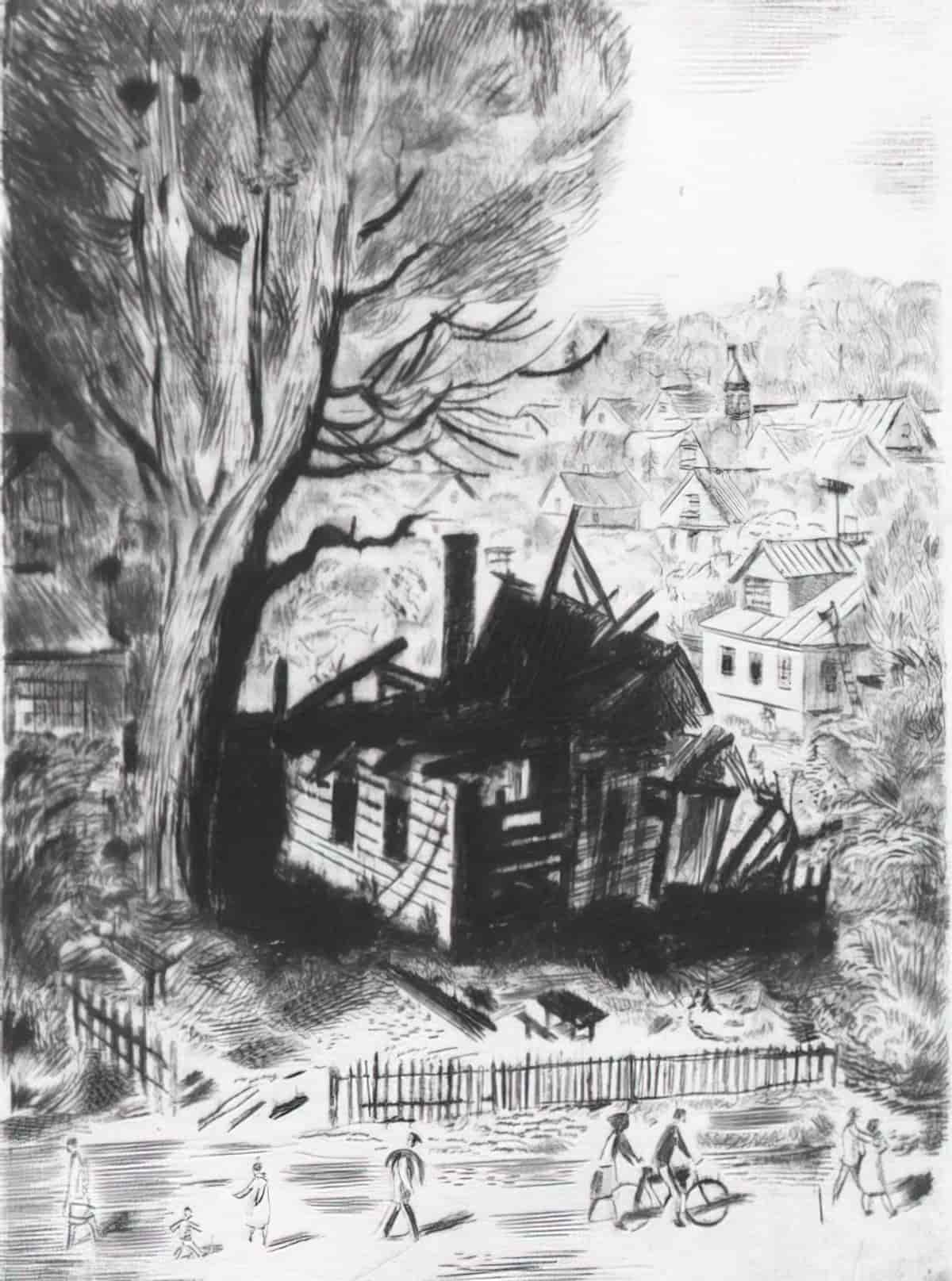

Stories of communities with a scary haunted house and a scary, witchy old lady are plentiful. These houses probably sit at the liminal space between suburbia and the wilderness. In contrast to the family houses around, they will be poorly maintained, a source of gossip among the adults and spooky speculation among children. If you trick or treat there, she may even poison you…

During the Witch Craze of the middle ages, it was thought that every village had a witch. This belief was par for the course. Some people even made a living out of casting spells and whatnot to ostensibly keep populations safe from these so-called witches.

And who were the witches? They could be almost anyone—anyone could accuse you. But in reality, witches were most likely the disenfranchised, the poor, the disabled and elderly, no longer able to contribute to society in the way a young, healthy, reproductive person can. With no one to protect them, these old women were cast out of their communities.

Set in the mid 20th century, this story is not of witches, but is a portrait of how the more things change, the more they stay the same. Mrs. Fullerton is useless to these young families. She won’t even babysit for them. She is neither polite nor maternal, which goes against everything a good woman is supposed to be.

A good woman. The wives of the men, in contrast, are polite and wifely—not too bossy, but obediently meek. These are the good women, and their husbands are good men (TM).

But of course, ‘good’ in this context does not mean morally good. This kind of goodness is self-serving, but appears community-minded. It is still self-serving; fortunately for the young, privileged families, their self-serving behaviours serve a majority.

We can’t ignore that there’s a racial component to this. It appears everyone, including Mrs. Fullerton is white. But this is classic white people behaviour. Elsewhere, in the same era, Black families were being ushered from place to place, also for fear that their very presence would lower the value of the houses.

This, of course, is how entire communities let bad things happen, exemplified in fiction by Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery“.

DANCE OF THE HAPPY SHADES (1968)

- “Walker Brothers Cowboy” — A woman looks back at her 1930s childhood. Her family has 2 or 3 months earlier lost the family fox farm and moved to a small town on the edge of Lake Huron, where the father has started a new job as a door-to-door salesman. Meanwhile, the mother sinks into a depressive state. One day, the father takes the narrator and her younger brother on a ride, where he visits an old friend/lover. The daughter learns that her father had another sort of life once.

- “The Shining Houses“

- “Images” — A little girl is the narrator of this double character study: A second cousin who came to take care of the household while her own mother was sick, and a man with a psychotic mental illness who lived alone in the woods. After meeting the man in the woods, the little girl learns not to be afraid of the woman who has infiltrated the household to take care of them all.

- “Thanks for the Ride” — This story is written with the viewpoint character of a young man. He has just finished school and is out with his older cousin with the purpose of losing his virginity. Together they pick up some ‘loose’ girls. The whole experience is perfunctory and defamiliarizing.

- “The Office” — A housewife decides to improve her life by carving out some time for herself to pursue her passion of writing. So she rents a room above a hair salon and drugstore. But the landlord won’t leave her in peace, deeming her time his.

- “An Ounce of Cure” — A young teenager is pining after a boy who dumped her months ago for another girl. She can barely think of anything else. One night she is babysitting when she spies three bottles of liquor on the bench. She accidentally gets very drunk and very caught out. Her reputation is ruined. But as an older woman looking back on this time, she is glad it happened.

- “The Time of Death” — A mother who lives in one of the squalid cottages on the edge of town has lost a child in a terrible accident. The village gathers round, but how genuine are they in their grief?

- “Day of the Butterfly” — Two girls at a primary school are ostracised. One is the narrator, now grown, ostracised for being an out-of-towner who doesn’t wear the right clothes. The other is more ostracised still, because her parents are immigrants, because she smells like rotting fruit, and because her brother needs her to accompany him to the toilet. When this girl is dying in hospital from child leukemia, the young narrator is filled with inexplicable grief. It is now too late to be a real friend to this outcast, and anything she does in kindness will feel empty and pointless.

- “Boys and Girls” — An outdoorsy farm girl loves helping her father on the fox farm but realises she’ll very soon be required to go indoors to help her mother with domestic work. In contrast, her younger brother, far less conscientious, will be allowed to stay outside and work with the animals, enfolded and welcomed into the masculine world.

- “Postcard” — A woman around the age of 30 has been seeing a man for years. They’re long-term partners. The reason they haven’t married: He’s waiting for his mother to die. His mother wouldn’t approve of him marrying the narrator, we deduce because of the wealth disparity. Unfortunately for the narrator (Helen), turns out the guy never intended to marry her anyway. He sends her a postcard from Florida telling her how he’s having such a good time. Next minute, Helen’s best friend is round to break the bad news: It’s been published in the paper, the lover is getting married to someone else after all this time. The weasel didn’t have the gumption to let Helen know. So she goes round to his house, stands outside and expresses her grief in a very vocal way.

- “Red Dress—1946” — A thirteen-year-old girl’s first ball. Her mother sews a red dress with a princess neckline. Suddenly she looks much older. She barely recognises herself in the mirror, and longs for childhood again. Almost all the girls around her are obsessively interested in boys. Everyone, that is, except one other girl who says she despises boys, and plans to support herself by working as a P.E. teacher. But by aligning herself with this queer girl, our thirteen-year-old risks much. What will she do? Will she take up the offer of friendship?

- “Sunday Afternoon” — Seventeen-year-old Alva has recently finished high school and started working as a maid for the mega-wealthy Gannetts. Today they are hosting a party at their mansion and Alva must navigate a delicate social situation: They want her to feel part of the family, but what does that mean, exactly, when you’re actually the paid help? Alva must also navigate the men who enter the house, several of whom express sexual interest in her. This isn’t your run-of-the-mill, predictable young-woman-is-seduced storyline, but Alice Munro keeps readers in audience superior position as we watch with bated breath what happens to Alva in this big, lonely island of a house. We’re left to deduce most of it.

- “A Trip to the Coast” — An eleven-year-old girl called May lives with her mother and grandmother (mostly her grandmother) in a general store in a three-house township. There’s nothing to do in this one horse town. But today she’s looking forward to same-age company. However, the “company” is a total let-down, and so her grandmother, for the first time ever, suggests the two of them take a trip to the coast. But then another visitor comes. A customer who declares himself an amateur hypnotist. This story ends on a cliff hanger, and I don’t believe Munro has given us enough of a symbolic layer to fill in the gaps for ourselves. I believe we’re supposed to feel exactly as unmoored as eleven-year-old May, waiting out front of the store in the rain.

- “The Peace of Utrecht” — Numerous critics and scholars consider this story the jewel of the crown of Munro’s first collection. Considering that, it’s baffling why it doesn’t make it into more Selected and Collection volumes. It’s certainly the most overtly personal of Munro’s early stories, and she has said in interview that this one changed the way she wrote. Until writing “The Peace of Utrecht” she’d written to be a writer. Now she wrote because she knew only she could write this story. The biographical relevancy: young Alice Munro cared for her mother over many years as her mother lived, then died, with Parkinson’s disease.

- “Dance of the Happy Shades” — An emotionally astute and very observant adolescent girl is required to accompany her mother to an embarrassing recital with the elderly, unfortunate-looking spinster teacher whose spinster sister is recently bedridden due to a stroke. The story is told via the slightly baffled viewpoint of the girl, who is required to recite a tune on the piano at these excruciating annual events.