In stories for children, as in stories for adults, emphasis on the seasons and the circular nature of time gives a story a feminine feel. Each season carries its own symbolism, but it’s not a clear delineation.

Why do we associate cycles and seasons with femininity? Who better to teach us something than Dwight Schrute?

With the recent Gilmore girls revival we now have agents/editors asking for similar story structures.

What would that mean, exactly, to write a story with a similar structure to Gilmore girls?

One aspect which provides structure to Gilmore girls is the seasons. Rory’s life (like any diligent high school student’s) is determined by the school terms, in turn different according to season. Stars Hollow holds regular annual events which are also connected to seasons, be it Halloween pumpkins, picnic hampers or Christmas festivities.

In television miniseries, the seasonal structure isn’t new. Take for instance the Disney adaptation of Little House On The Prairie. Each of the three episodes has distinctly different seasons.

The fact is, this story structure is very old, especially in stories for and about girls.

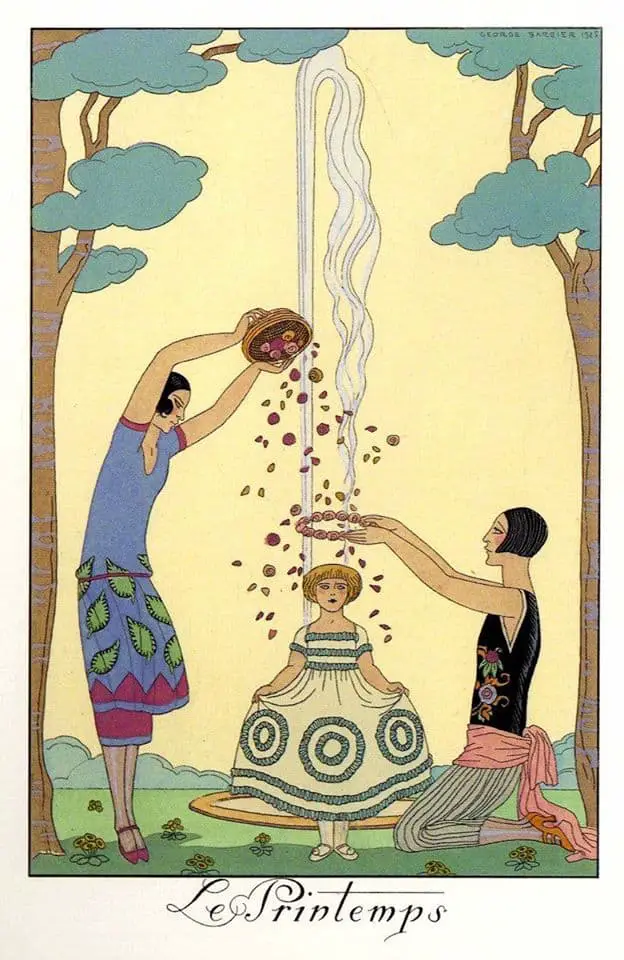

The straight (non-reversed, un-ironic) version looks like this:

SUMMER

Characters exist in:

- a troubled, vulnerable state or

- in a world of freedom susceptible to attack

The crickets sang in the grasses. They sang the song of summer’s ending, a sad, monotonous song. “Summer is over and gone,” they sang. “Over and gone, over and gone. Summer is dying, dying.” The crickets felt it was their duty to warn everybody that summertime cannot last forever. Even on the most beautiful days in the whole year — the days when summer is changing into fall — the crickets spread the rumor of sadness and change.

Charlotte’s Web, E.B. White

AUTUMN/FALL

‘Fall’ was common in British English until the 17th century, when ‘autumn’, from French, took over. It’s short for ‘fall of the leaf’ (just as ‘spring’ is short for the ‘spring of the leaf’) and was the successor to the Old English name for the season, hærfest, ‘harvest’.

Susie Dent

Characters begin their decline.

Alternatively, or as well as this decline, autumn lends a cosy feel which takes us back to childhood especially — this is a Northern Hemisphere thing, and works well for American audiences, who have Thanksgiving, Halloween and football matches in the fall.

The late scenes of Girls on Fire by Robin Wasserman and Marlena by Julie Buntin both occur in a damp, shadowy, late-autumn woods haunted by literal death that signals the end of girlhood.

Movies in which autumn features heavily:

- When Harry Met Sally

- Autumn in New York is a movie in its own right, but…

- …another film which features autumn in New York is You’ve Got Mail! You’ve Got Mail spans the entire year through the seasons, but the fall scenes are thought to be the best.

- Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (think of Hagrid’s hut with all the pumpkins)

- Stepmom — fall in Connecticut

- Hocus Pocus and other Halloween movies like Practical Magic — because for North Americans, fall is synonymous with Halloween

- Dead Poet’s Society — for its back-to-school feel. (Australian students return to school while it’s still well and truly summer, so this is a Northern Hemisphere thing.)

- Remember The Titans and Rudy — because autumn is football season

- Pieces of April — because fall is Thanksgiving season

- Little Women — because a lot of the story takes place in the autumn

WINTER

Characters reach their lowest point.

Middle grade novel Skellig by David Almond is a story which makes use of seasonal symbolism. When Michael discovers Skellig, his luck begins to change. “Winter was ending.” The season of death and dormancy (especially for Michael and Skellig) is about to give way to the rebirth of spring-a kind of second innocence.

However, there’s winter and then there’s winter. A winter blizzard is dangerous, but a landscape covered in snow has the opposite effect, evoking hygge, or as Jerry Griswold puts it, evoking snugness.

There are, of course, certain times of year and day that are more conducive to evocations of snugness. Winter, especially after snow has fallen, and Christmastime are special in this regard; consider, for example, the tableau of the family in Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women, all gathered together around the fire when father returns at Christmas; or Clement Moore’s poem “The Night Before Christmas” when “The children were nestled all snug in their beds, / While visions of sugarplums danced in their heads.” And as for time of day, the moment for nesting is when sleep comes; here the great tableau may be in Johanna Spyri’s Heidi when grandfather, both when Heidi first arrives and when she returns from Frankfurt, steals up the ladder to look at the slumbering child in the nest she has made for herself from hay in the attic. To be brief: a snug place is a place where one can sleep peacefully.

Jerry Griswold

Ancient tales offer various personifications of the seasons. Winter has Jack Frost and Father Frost (from Russia).

If you’d like to hear “The Story of King Frost” read aloud, I recommend the retellings by Parcast’s Tales podcast series. (They have now moved over to Spotify.) These are ancient tales retold using contemporary English, complete with music and Foley effects. Some of these old tales are pretty hard to read, but the Tales podcast presents them in an easily digestible way. “The Story of King Frost” was published December 2019.

SPRING

In the spring, characters overcome their problem and rise.

This short film, called Spring, follows a girl’s trip out of the dark forest, which gradually blooms into a more welcoming arena. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WhWc3b3KhnY&feature=youtu.be

A story might start in springtime. In Beverly Cleary’s Emily’s Runaway Imagination, the story begins with spring and a feeling of welcome change. Almost exhilaration:

The things that happened to Emily Bartlett that year!

It seemed to Emily that it all began one bright spring day, a day meant for adventure. The weather was so warm Mama had let her take off her long stockings and put on her half socks for the first time since last fall. Breezes on her knees after a winter of stockings always made Emily feel as frisky as a spring lamb. The field that Emily could see from the kitchen window had turned blue with wild forget-me-nots and down in the pasture the trees, black silhouettes trimmed with abandoned bird nests throughout the soggy winter, were suddenly turning green.

Everywhere sap was rising, and Emily felt as if it was rising in her, too.

Beverly Cleary

SUBVERSION OF SEASONAL SYMBOLISM

However, a writer may choose to avoid the cliche by turning it around. So the character declines in spring and is rejuvenated in the winter. This not only short-circuits the audience’s expectations but also asserts that humans, though of the natural world, are not enslaved by its patterns.

What about the seasons and writing for children?

If writing for children is different from writing for adults, surely it’s because our main audience has not seen enough of the world or of literature to have noticed cliche, which becomes more noticeable the older/better read you become.

Maria Nikolajeva, academic of children’s literature has made the following observations about:

THE TREATMENT OF TIME IN BOOKS FOR GIRLS AND BOOKS FOR BOYS

This is a fascinating concept, and something I’d not noticed until it was pointed out, by Maria Nikolajeva in Children’s Literature Comes Of Age. Earlier in the book she defines books for boys (often adventure) and books for girls (horse stories etc, and those starring girls) which these days tend to have pink somewhere on the cover. In an ideal world there’d be no such thing as sex differentiation in books. Because gender is not genre. But I’m quite radical like that.

One Swedish essay on narrative differences in books for boys and books for girls stipulated that male time is linear, while female time is circular…. Time in books for girls and in books for boys is closely connected with place. Not only is male time linear, but male space is open, as books for boys take place outdoors, sometimes far away from home in the wide world. Male narrative time is structured as a series of stations where an adventure is experienced, a task is performed, a trial is passed. Time between these stations practically does not exist. The text can say something like “after many days full of hardships they reached their destination…” The male chronotope is thus corpuscular, discontinuous, a chain of different separate time-spaces (“quants”) which are held together by a final goal. These separate chronotopes may also correspond to chapters in adventure boos: each chapter is self-contained, even if some threads can run from one chapter to another. It is easily observable in classic stories such as Mark Twain’s The Adventures Of Tom Sawyer (1876) or Robert McCloskey’s Homer Price (1943).

[…]

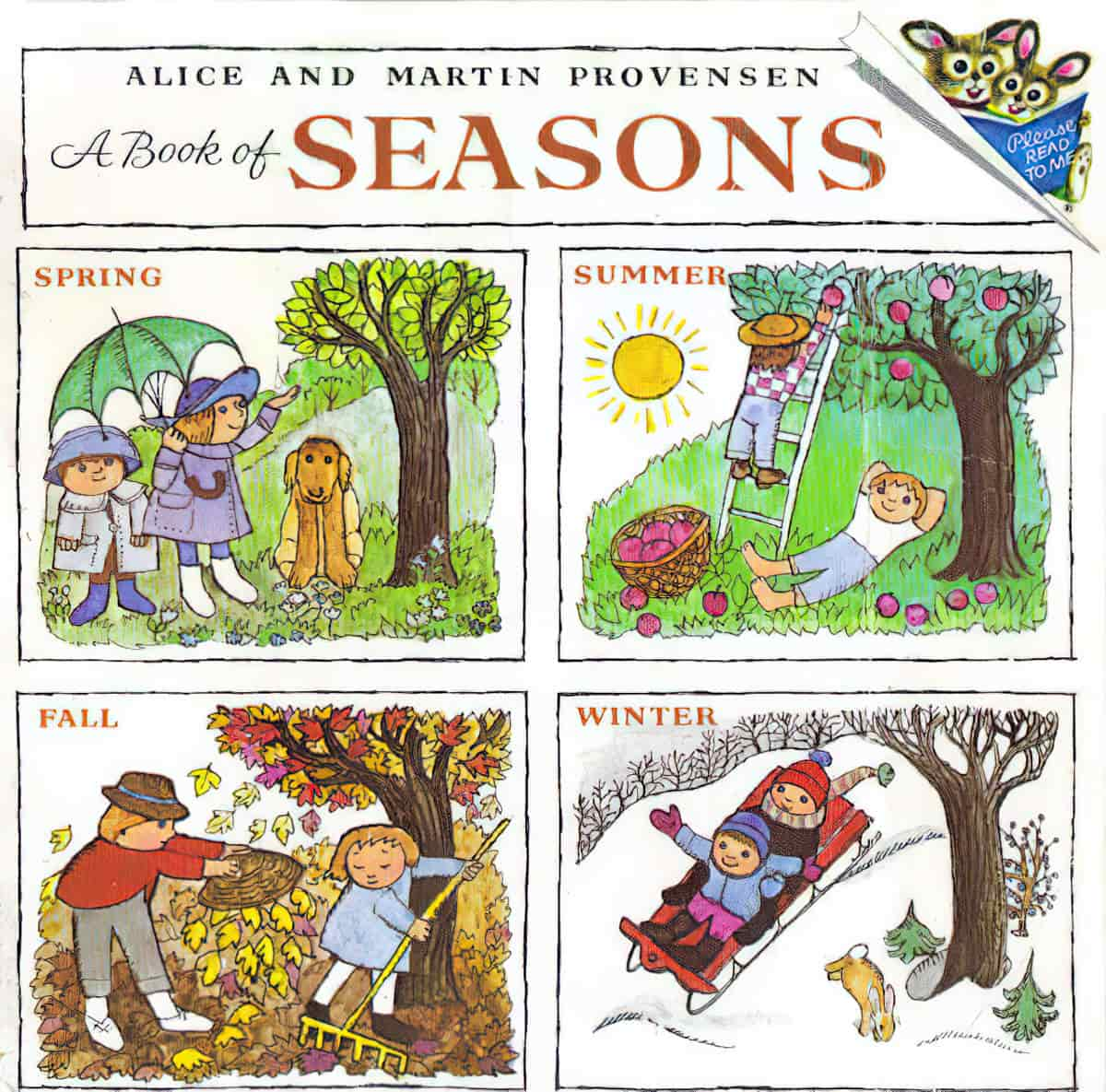

The chronotope in books for girls is completely different. The space is closed and confined. The action mostly takes place indoors, at home (alternatively at school). Time is cyclically closed and marked by recurrent time indications: (“It was spring again,” “It was Christmas again”). Three classical girls’ books, Little Women (1868), Anne Of Green Gables (1908) and Little House In The Big Woods (1932), are very good illustrations. Any gaps in time can be easily filled by the reader, who knows that it takes time for plants to grow or for snow to thaw, that the school year is full of homework, that housework is the same year in and year out. Female narrative time is often extended to several years with certain recurrent points. The chronotope is continuous both in time and space. Spatial movement in girls’ books means merely a change from one confined space to another likewise confined one — for instance, from the parents’ home to a boarding school, from the heroine’s childhood home to her husband’s home, to “the doll house,” an image often used by contemporary writers trying to break this pattern; one example is Maud Reutersward’s A Way From Home (1979), the Swedish title of which is “The Girl and the Doll House.”

The female narrative chronotope is also based on our conceptions of male and female nature…Female time is circular, follows the cycle of the moon, and consists of recurrent, regular events of death and resurrection, seasonal changes and so on. … Linear male time is a product of enlightenment and is the spirit of action and progress.

…there are many deviations… As in all other areas, in chronotope structures of children’s books of the past ten to twenty years there is also a merging of male and female, a disintegration of the epic chronotope, and some bold innovations.

Nikolajeva’s book was published in 1996, so another 10 or 20 years have passed even since then. I’d be interested to know what has happened. Are stories for girls still mostly set inside? Do books for girls run by the moon?

EXAMPLES OF SEASONAL SYMBOLISM IN CHILDREN’S LITERATURE

Sometimes, winter is a metaphor for depression. As an example, see Blackdog by Levi Pinfold.

In the similarly named, earlier title by Pamela Allen, Black Dog, more is made of the significance of the seasons with inclusion of the following double spread:

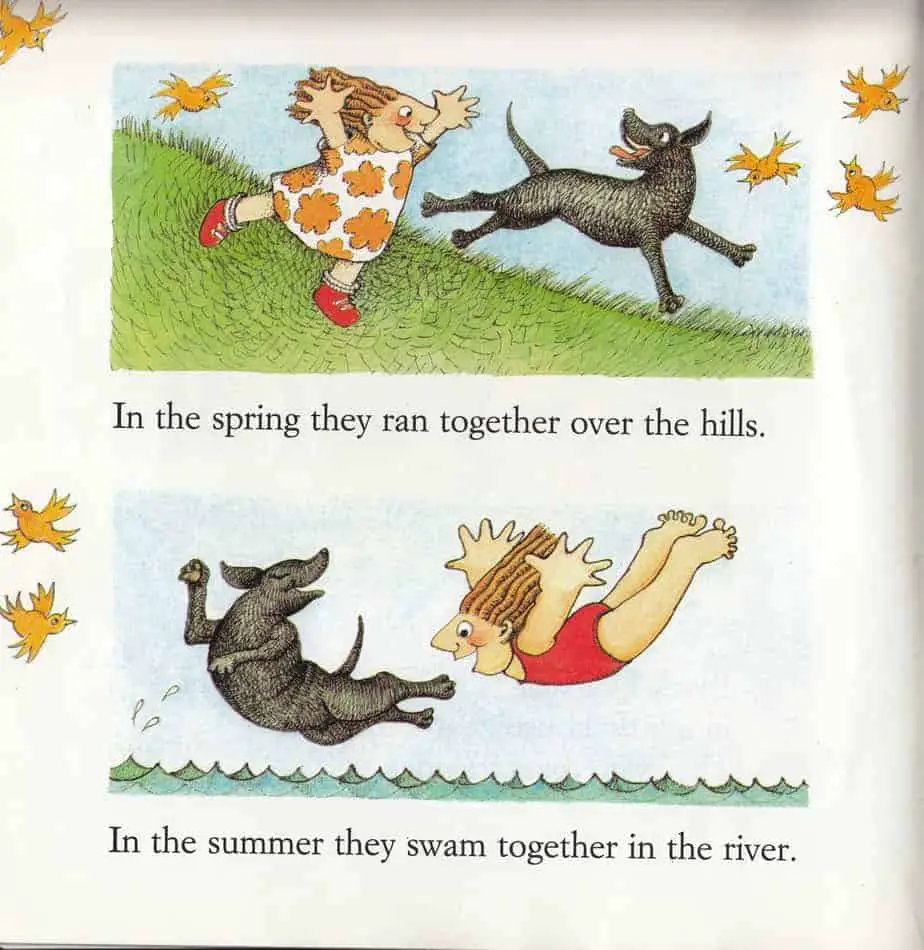

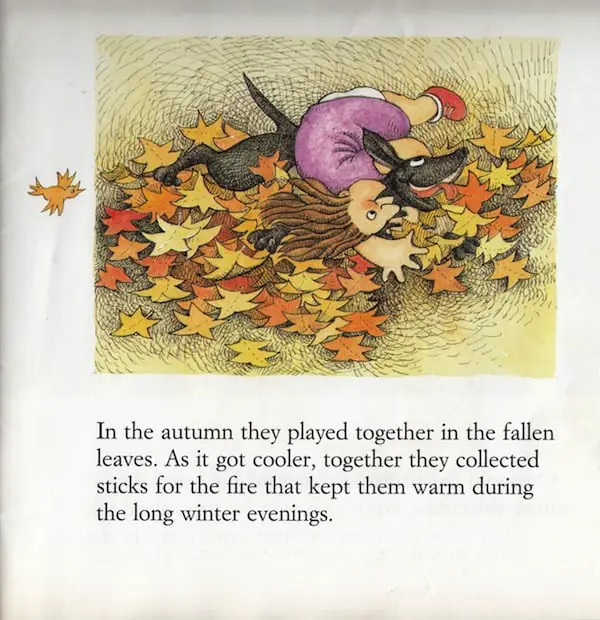

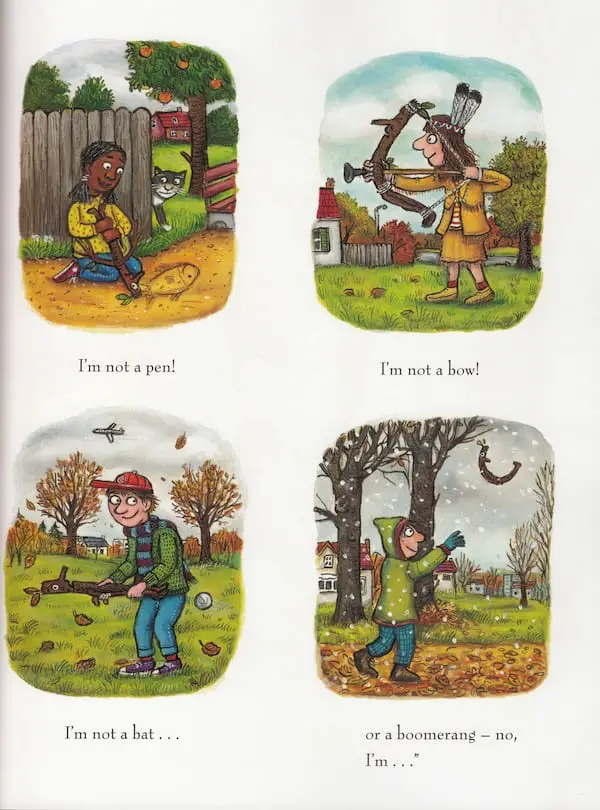

Axel Scheffler

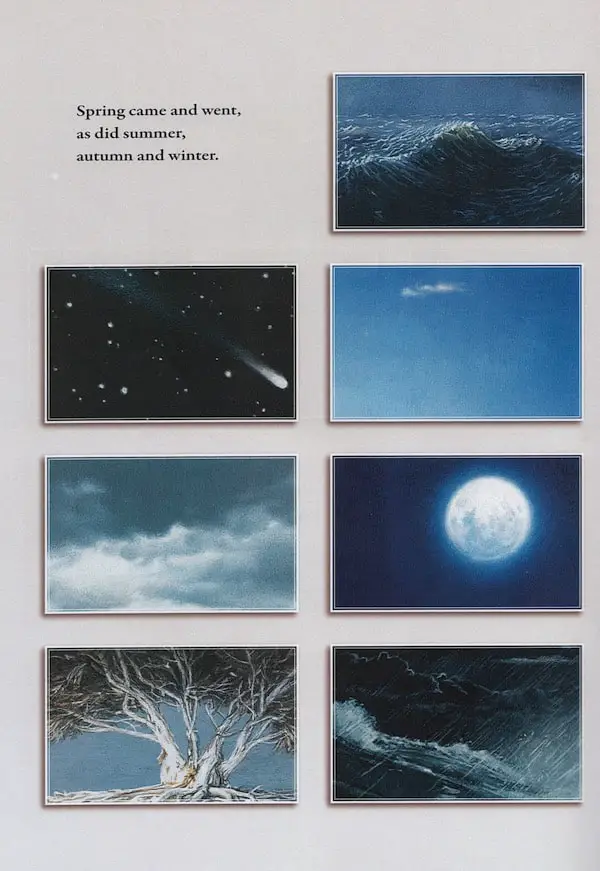

In Stick Man, illustrator Axel Scheffler demonstrates the passing of time with the following montage:

In the Australian picture book Tanglewood, too, we have a page of thumbnail illustrations depicting the passage of time via the seasons.

Beatrix Potter

Handy quotes Lewis on his own memory of reading the Beatrix Potter book “Squirrel Nutkin” when he was young: It “troubled me with what I can only describe as the Idea of Autumn.” The subject of childhood, even more than old age, seems always to be about its ending. My favourite chapter was the last one — about death in children’s literature, but also about endings generally.

NYT review of Wild Things: The Joy of Reading Children’s Literature as an Adult By Bruce Handy

The examples above are all picture books, but stories which emphasis cycles are common in stories for (or about) older girl readers. Julie of the Wolves is an excellent example. This novel is a Robinsonnade earlier feminist novel with explicitly ecological themes.

Miyax (Julie) must kill to remain alive herself, but her killing is always shown to be part of the ongoing life cycle that must continue if life is to be sustained on the tundra. […] The ideology […] is explicitly ecological, but it contains an implicitly feminist message as well, for this ecological veneration of life cycles inherently praises the interconnectedness of life cycles that feminist texts so often embrace. Rather than unfolding with the linear plot-line that is common in children’s realism, Julie of the Wolves contains an embedded narrative structure that parallels the text’s consciousness of cycles. […] Nothing in Miyax’s life happens in isolation, and nothing occurs in a straight line. Instead, she moves forward, makes mistakes, and moves forward again. Thus, the narrative structure parallels the nonlinear nature of Miyax’s life and the cyclical nature of the novel’s setting.

Roberta Seelinger Trites, Waking Sleeping Beauty

As for the cycles of the female body, the text openly addresses how a teenager living in isolation deals wtih menstruation by clearly stating that she has not yet reached menarche.

Obviously, the association of cycles and femininity are to do with menstruation, pregnancy and childbirth. The female body goes through clear cycles of birth and rebirth, while men just get older and die.

For more on that see Menstruation In Fiction.

FURTHER READING

Some countries would be better served decolonising weather concepts. Australia is an excellent example of a country which does not fit the four seasons model.

In this poem, a Black child explores his shifting emotions throughout the year.

There is a place inside of me

a space deep down inside of me

where all my feelings hide.

Summertime is filled with joy—skateboarding and playing basketball—until his community is deeply wounded by a police shooting. As fall turns to winter and then spring, fear grows into anger, then pride and peace.

In spring, when City Dog runs free in the country for the first time, he spots Country Frog sitting on a rock, waiting for a friend. “You’ll do,” Frog says, and together they play Country Frog games. In summer, they meet again and play City Dog games. Through the seasons, whenever City Dog visits the country he runs straight for Country Frog’s rock. In winter, things change for City Dog and Country Frog. Come spring, friendship blooms again, a little different this time.

Header illustration: Stevan Dohanos, Billboard Painters,,from Saturday Evening Post cover, February 14, 1948