The rule of three in storytelling has several uses. The first works like this:

- One tells us what the risk is.

- Two confirms what wrong behaviour is.

- At three, we know the rules, and so can appreciate what the smart third person is doing differently, to break the un- successful pattern and win.

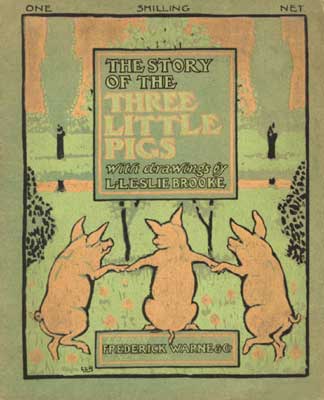

If that folk tale was about just one pig who built a house of bricks in the first place, and the wolf couldn’t get in no matter how he huffed and puffed, where would the story be? Conflict, but no drama, just stalemate. Success for the pig, but no suspense. Anticlimax. No story.

Refer to: Picturebook Study: The Three Little Pigs

Three is suspense, pattern, and contrast, all in one nifty little technique as old as storytelling.

It’s the scientific technique of the variable, with third time lucky.

From Anson Dibell’s book on writing called Plot:

If somebody fails twice, in similar circumstances, there’s going to be more tension and drama when they try the third time because we’ve already seen them fail and know it can happen. We know what doesn’t work, we know the situation; now we’re focusing on what they’re doing differently this time. We’re aware of the pattern, the apparent rules, and are concentrating on the one thing that changes.

Instead of two repetitions, you can use the Rule of Three.

- The first time the bell coincides with the painful electric shock, you’re too busy being shocked to notice.

- The second time, you think uneasily that maybe it wasn’t a coincidence.

- The third time, you’ve started jumping before the bell is even done ringing.

If you want your reader interested and involved in the scene before it’s fully begun to happen, there’s nothing like a triple set- up to get things rolling. It gives added drama. It directs the read- er’s attention where you want it directed. And it makes the scene’s meaning clear in a way it could not have been in isolation.

Choose and control the variable with care, keep the situations visibly comparable so the reader will be aware of the bell/ shock pairing and be anticipating the outcome, and all three scenes will gain in impact and effectiveness.

The second use is far more simple. Show a character doing something three times and we will assume they keep on going until the end.

An example of this occurs in Mercy Watson Thinks Like A Pig. Eugenia, the arch nemesis, plants pansies all around her house. Mercy makes a hole in the hedge and eats three pansies. Then the chapter ends. We deduce that she eats far more than three pansies. If left to her own devices, she will eat all of the pansies.

For an example of The Rule Of Three in a popular movie, see this article about Star Trek: First Contact.

(IT’S NOT ACTUALLY A RULE)

It’s more like a trick that often works. Bear in mind that experienced readers have grown weary of it. Recently a children’s book editor expressed her frustration on Twitter.

Ugh, that rule of threes business makes me crazy. I promise you, NO editor has EVER asked for things to come in threes. We can spot these manuscripts from the first line, and we often reject them, because they sound like the last ten manuscripts we rejected.

Frances Gilbert

THE RULE OF FOUR

The most important thing I [Nora Ephron] learned from Lee [a chef] was something I call the Rule of Four. Most people serve three things for dinner — some sort of meat, some sort of starch, and some sort of vegetable — but Lee always served four. And the fourth thing was always unexpected, like those crab apples. A casserole of lima beans and pears cooked for hours with brown sugar and molasses. Peaches with cayenne pepper. Sliced tomatoes with honey. Biscuits. Savory bread pudding. Spoon bread. Whatever it was, that fourth thing seemed to have an almost magical effect on the eating process. You never got tired of the food because there was always another taste on the plate to match it and contradict it.

Nora Ephron, from I Feel Bad About My Neck

THE RULE OF THREE IN PROPAGANDA

What we think others think greatly influences our own personal thoughts, feelings, and behaviour. Our accuracy in forming impressions of group opinion and group norms is also an essential component in guiding our social interactions. Nevertheless, little is known about how we estimate the prevalence of an opinion in a group. Quite obviously, an opinion is likely to be widely shared the more different group members express it. Our participants clearly recognized this and provided higher prevalence estimates when the same opinion was expressed once by each of three different group members than when it was expressed once by one group member. More surprising, and consistent with our hypotheses, however, our studies showed that hearing one person express an opinion repeatedly also leads perceivers to estimate that the opinion is more widespread relative to hearing the same communicator express the same opinion only once. Across our studies, we found that although three people each expressing the same sentiment is more influential than one person expressing the same belief three times, the latter was, on average, 90% the former.

Inferring the popularity of an opinion from its familiarity: a repetitive voice can sound like a chorus.

Kimberlee Weaver, Stephen M. Garcia, +1 author D. Miller

THE RULE OF THREE AT A STRUCTURAL LEVEL

I can’t believe how long it took me to realize: when you have a relationship in a novel, even a super major one, it’s mostly gonna be THREE SCENES. There are usually three (ish) key scenes that are big relationship turning points, and you can tinker with them endlessly.

To clarify: I specifically mean that there are usually a few scenes where people actually have a major relationship conversation and it’s a big turning point. Once I’ve identified those, I can fine tune them and also make sure the connective tissue between them is strong.

@charliejane