Before modern science took hold, when humans were still trying to classify everything we saw around us, people really did believe in the chimera. Take the example of the Scoter duck. No one could decide whether this bird was a bird or a fish. he Abbe of Vallemont even took it out of the bird category and put it in the fish category, and in the 19th century Catholics were allowed to eat Scoter duck on Fridays in lieu of fish if they wanted.

The chimera is important in the horror and speculative fiction/sci-fi genres.

The term chimera may be about to undergo a renaissance in modern parlance, because scientists are using the word to describe a single organism composed of cells from different zygotes. Animal chimeras are produced by the merger of multiple fertilized eggs.

WHAT IS A CHIMERA?

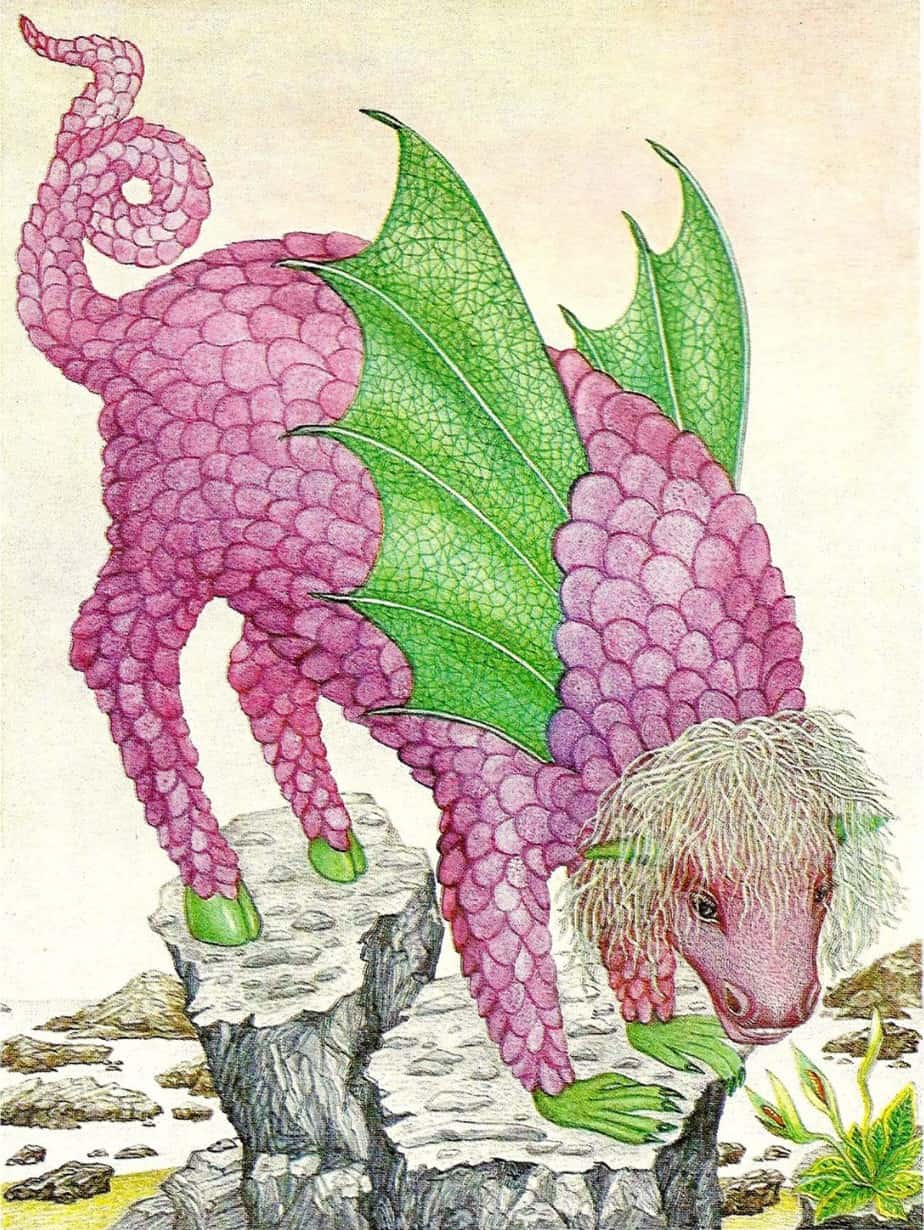

A creature composed of body parts from a variety of (at least two) different creatures.

Examples of hybrids in well-known tales:

- angels — human bodies, wings of birds

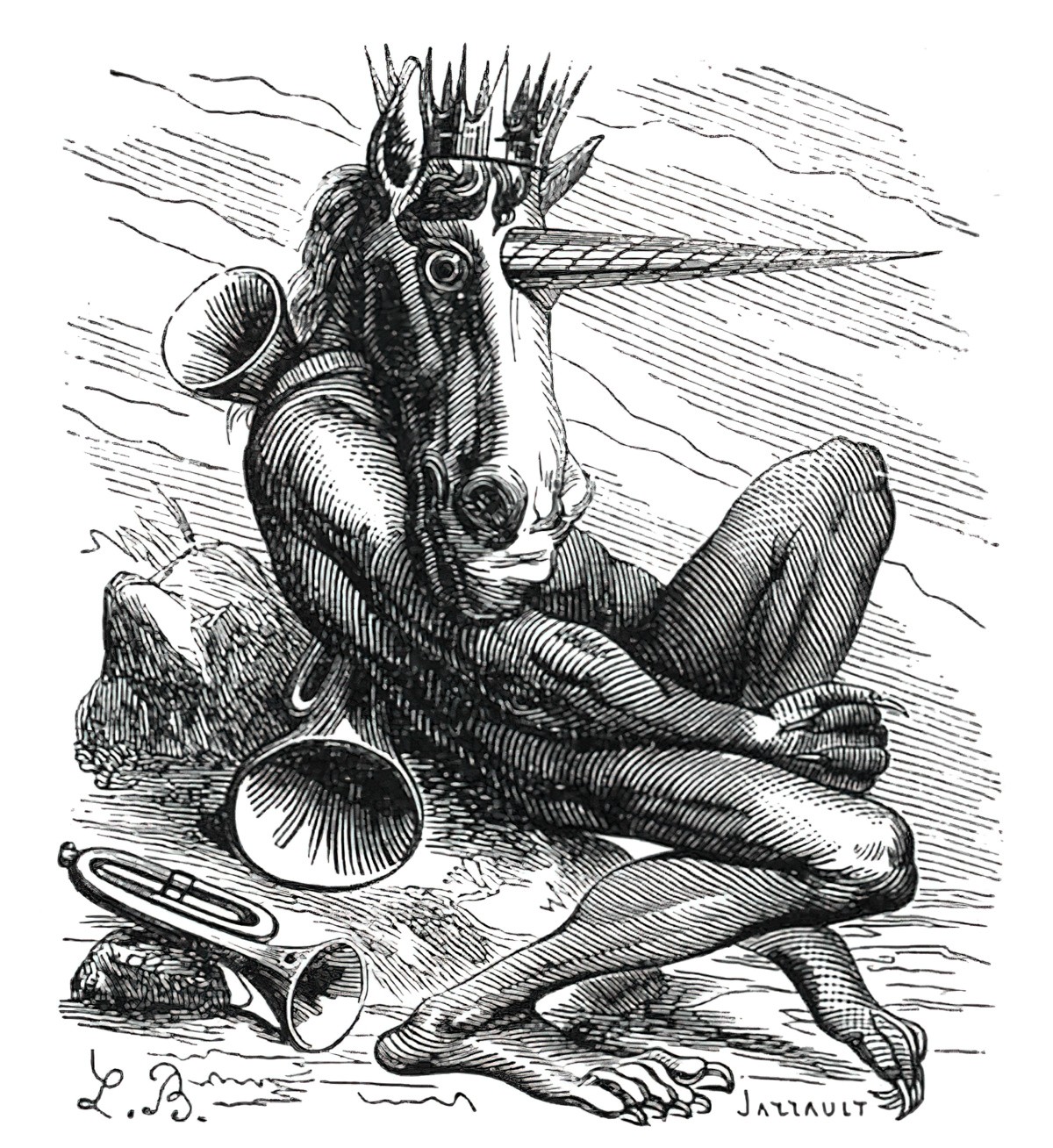

- centaurs — the head, arms, and torso of a man and the body and legs of a horse. Symbolises the essential duality of humans.

- bucentaur — half man, half ox/bull. Like the centaur, the bucentaur symbolises the essential duality of humans, however in the bucentaur, the baser (animalistic) part is stressed.

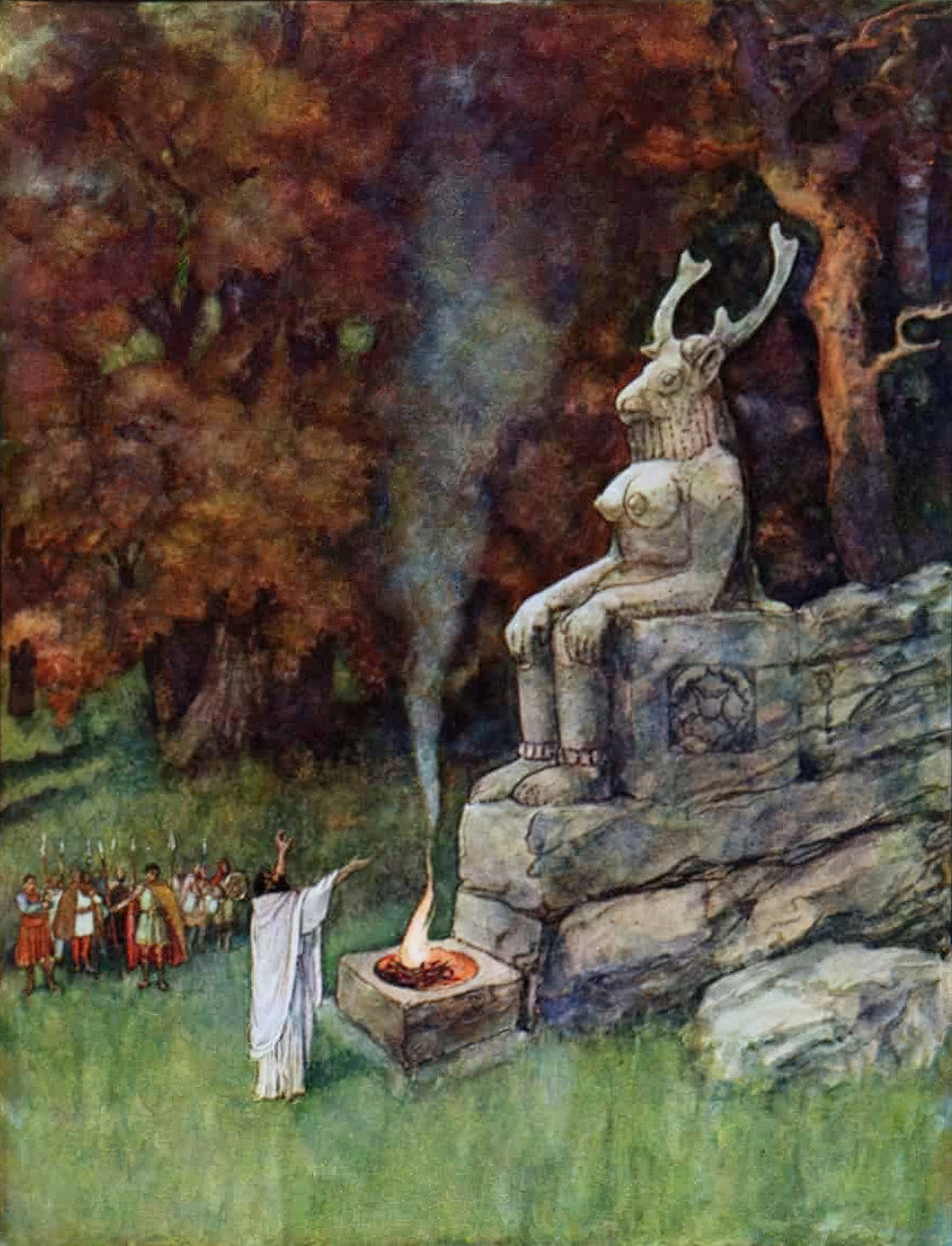

- devils — human plus goat

- sphinxes —woman’s head, lion’s body

- tritons — trunk of a man and the tail of a fish

- mantichore — the man beast

- gorgon — from Topsell’s Historie of Fourefooted Beasts (Topsell was the 16th century version of Arthur Mee)

- dipsa — so small that when you step on him you don’t see him

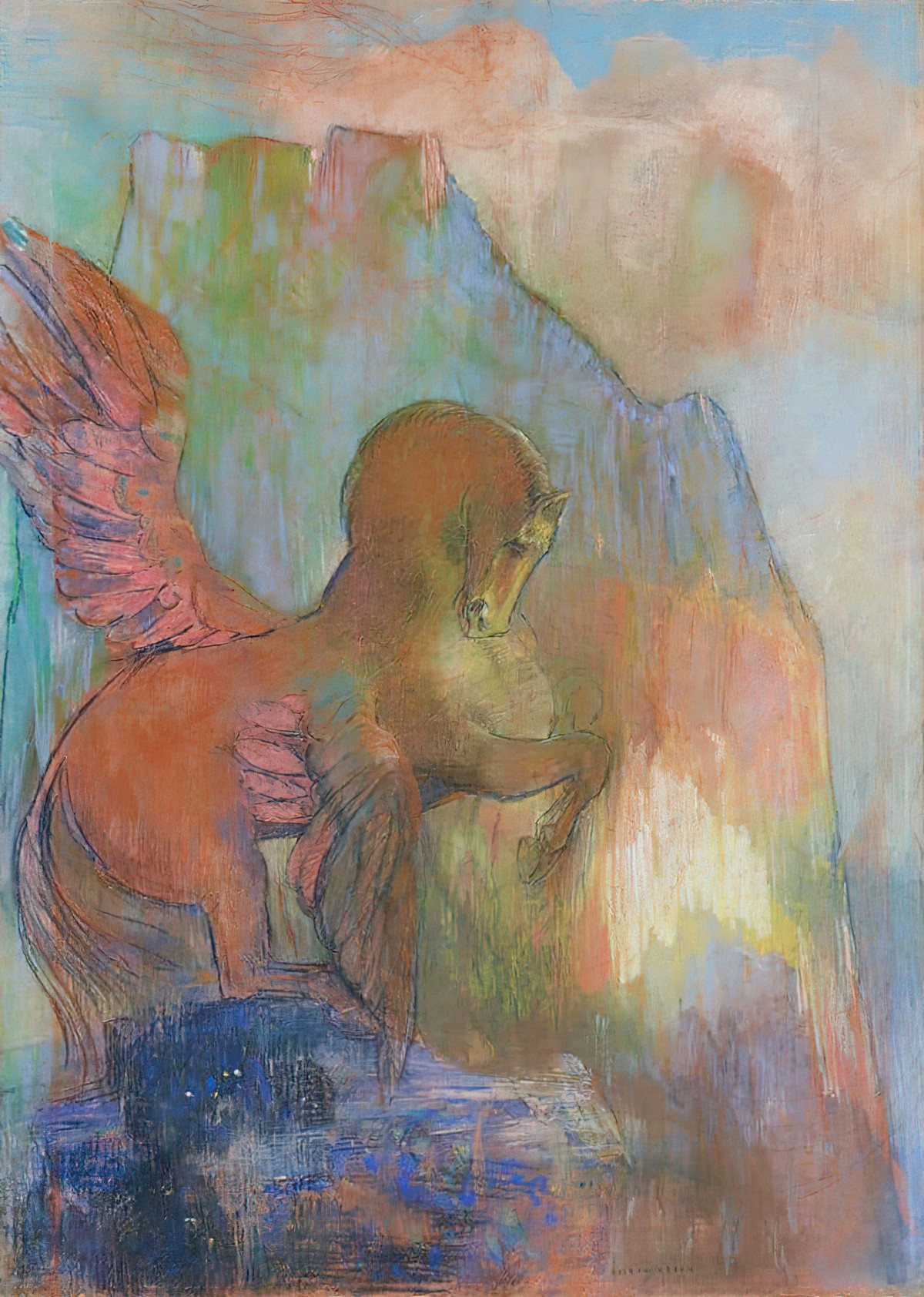

- pegasus — a horse that can fly, so a horse/bird combo. (Though creatures with wings are not always considered chimeras — sometimes they’re symbolically considered just creatures… but with wings.)

- mermaids and mermen — half human half fish, or the French version, melucina (singular: melusine)

- sirens — Sirens have changed a lot over history, from freaky bird women to seductive femme creatures more akin to mermaids. What’s so sexy about a chimera, though? This sentence sums it up: ‘The true allure of the Siren … lies in their status as in-between creatures, bridging the human world and the unknown afterlife with a powerful knowledge that both attracts and repels the onlooker.’ (Vice)

- unicorns — horses plus the horn from some other animal

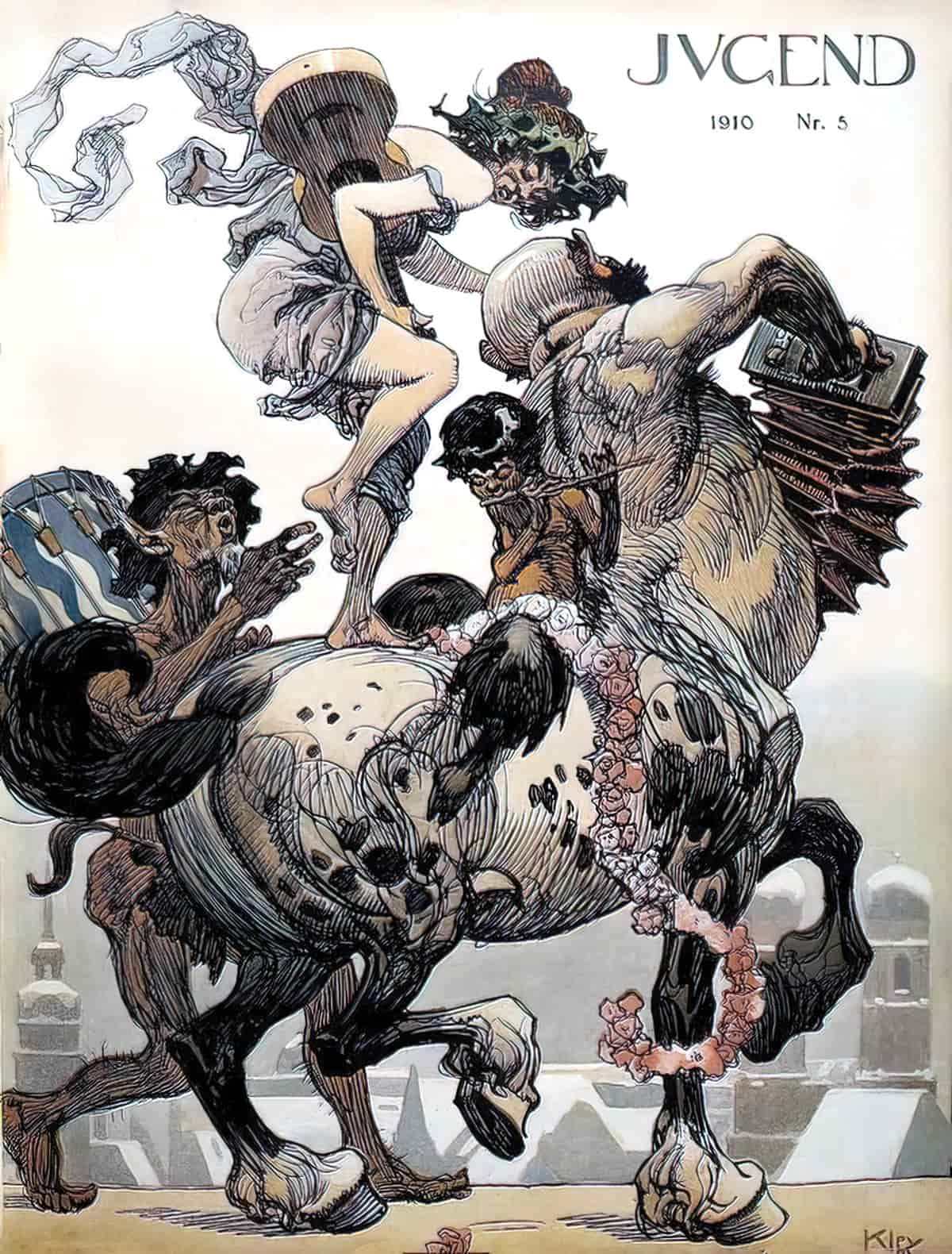

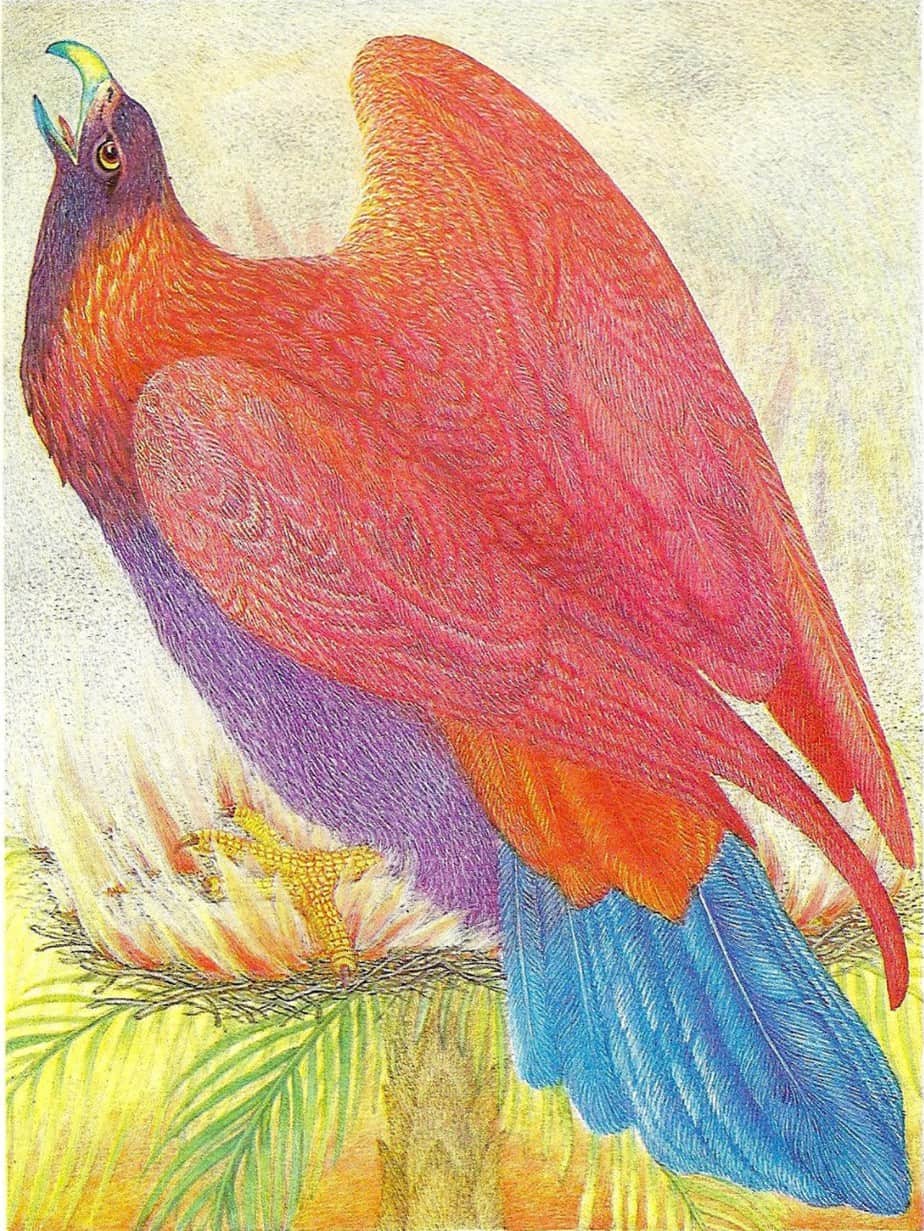

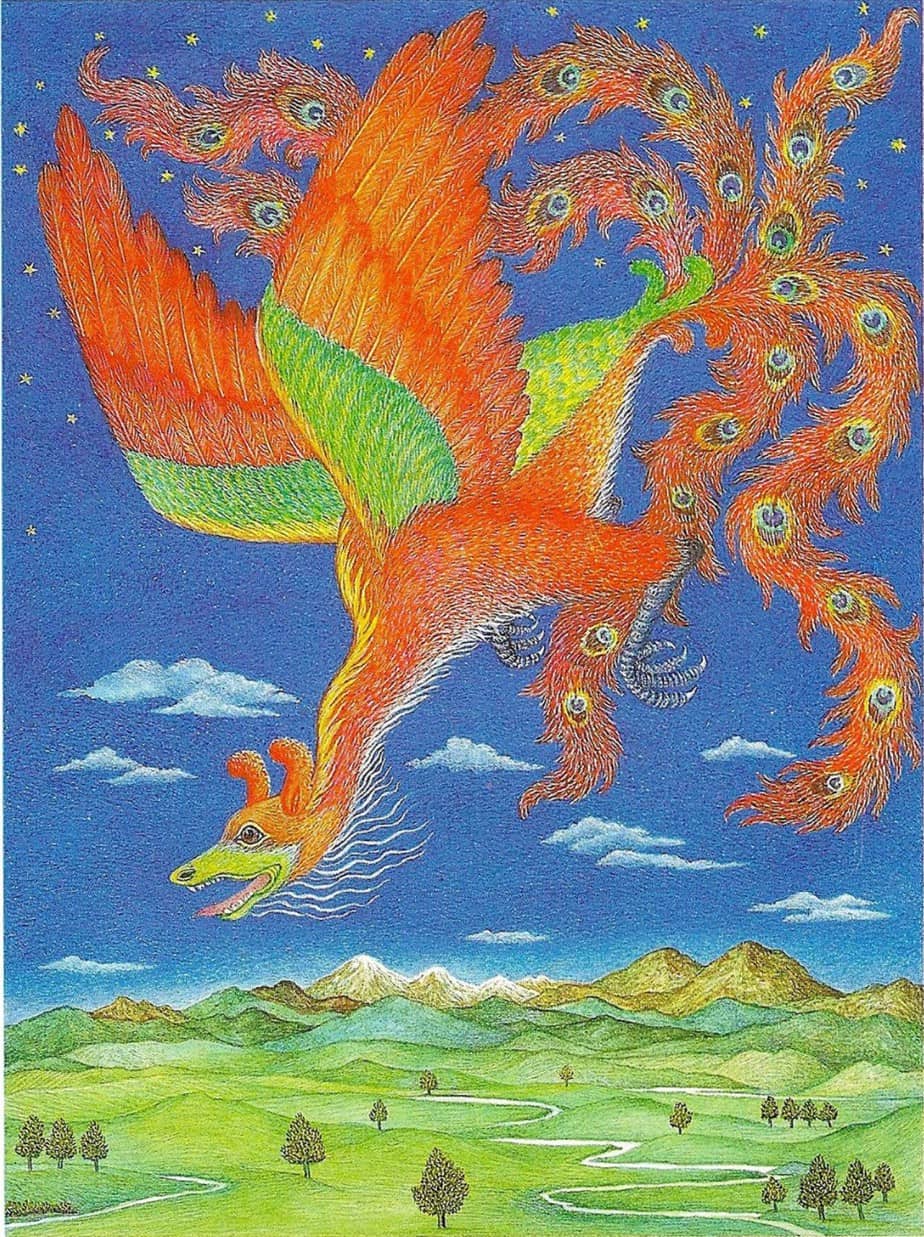

The spectrum of hybrid creatures can be beautiful, with lovely wings, or they can be monstrous and deformed, evoking a wide range of moods.

Gaston Bachelard points out that creatures with shells are regarded suspiciously by us:

And the fact is that a creature that comes out of its shell suggests daydreams of a mixed creature that is not only “half fish, half flesh,” but also half dead, half alive, and, in extreme cases, half stone, half man. This is just the opposite of the daydream that petrifies us with fear. Man is born of stone.

Poetics of Space

E. Nesbit was no stranger to the chimera. As well as children’s stories she also wrote horror, such as “Man-sized in Marble“. In that case, she is making use of the same axis of horror.

Drolleries — What, now?

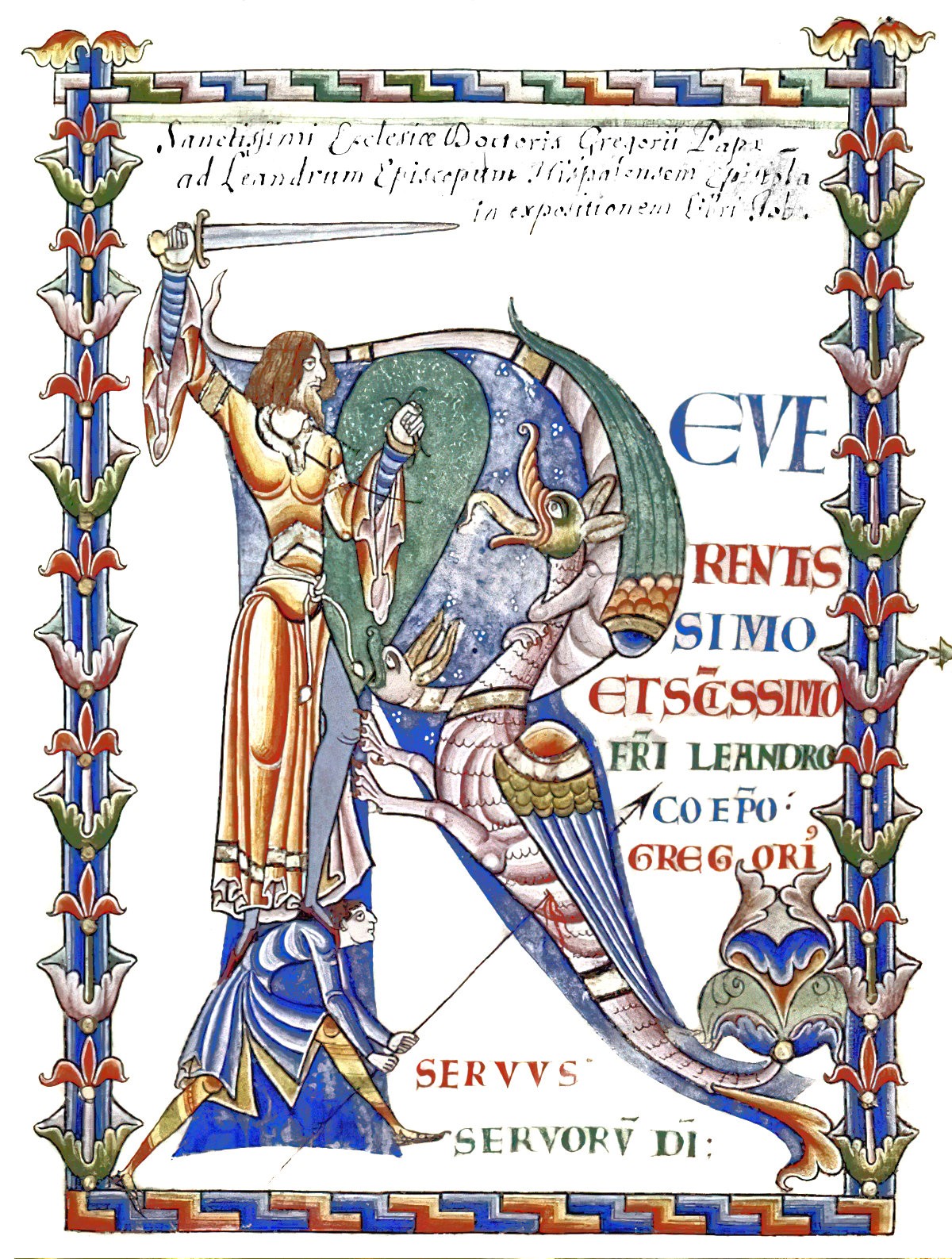

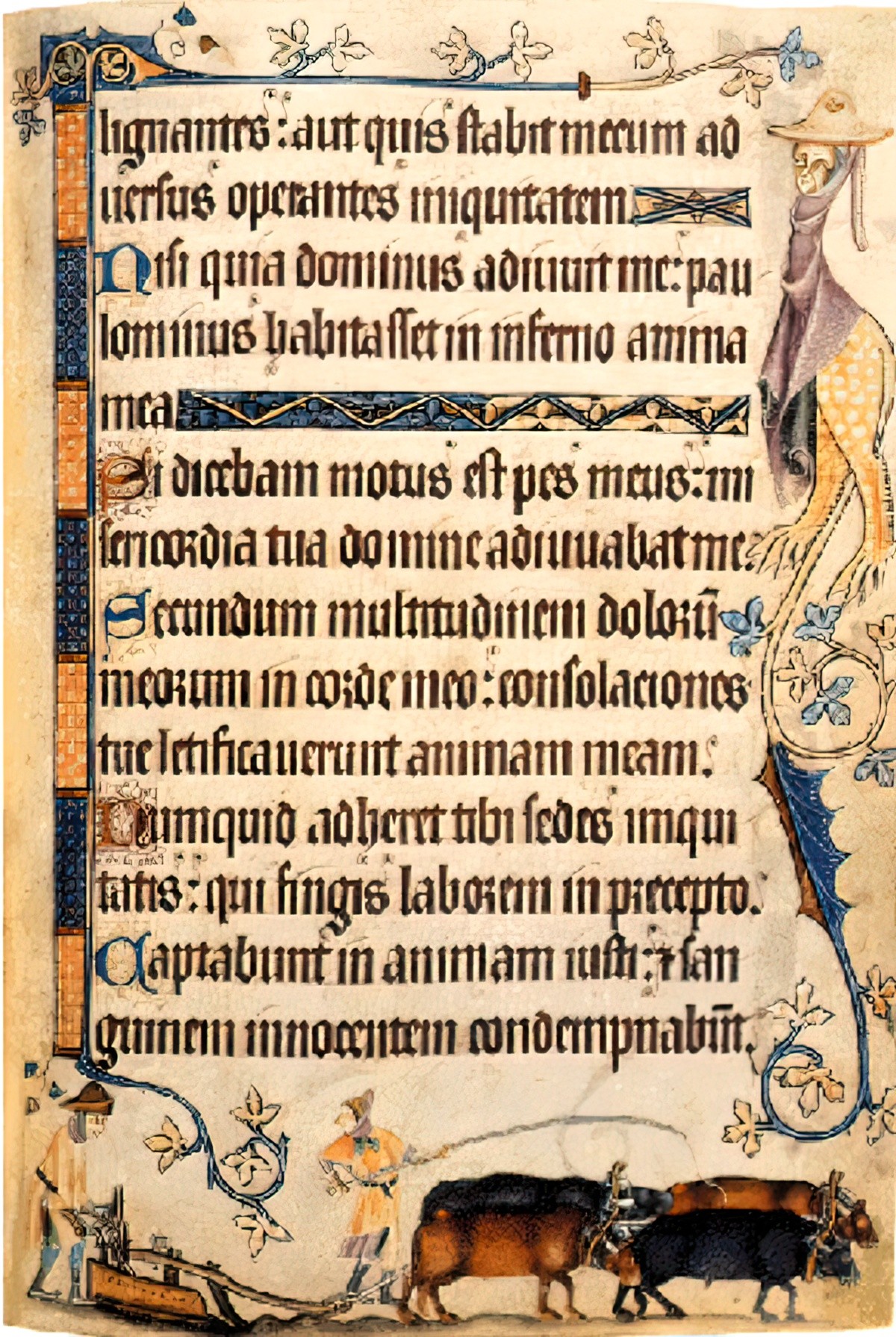

Bachelard, being French, offers the example of Les heures de Marguerite de Beaujeu by Baltrusitis, The Book Of Hours of Marguerite of Beaujeu, (around 1320-1330) as an example of a work full of such creatures. (Marguerite of Beaujeu was the daughter of a lord and the book was made for her. The real work is now kept at The British Library.) This book contains lots of ‘drollery’.

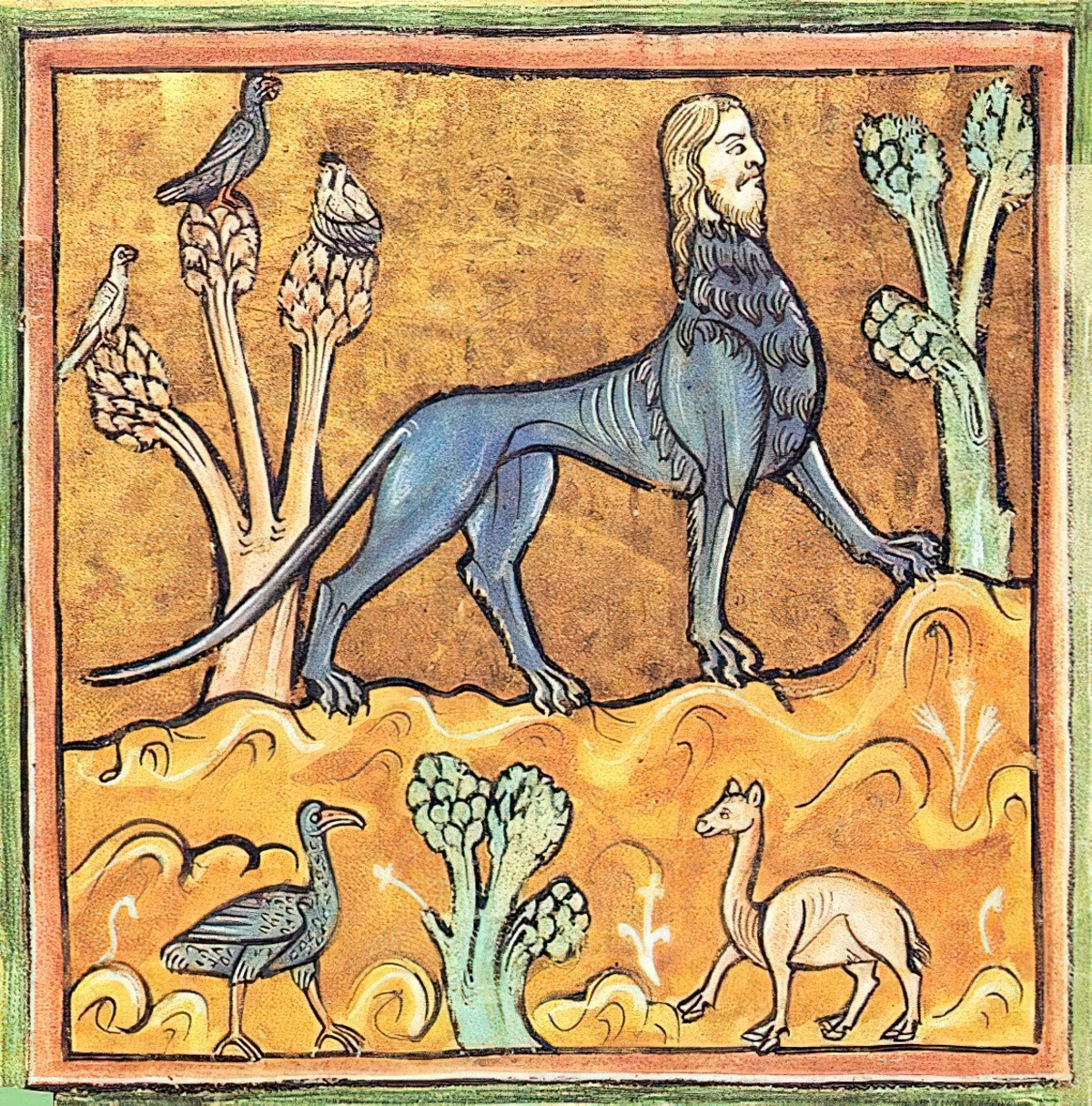

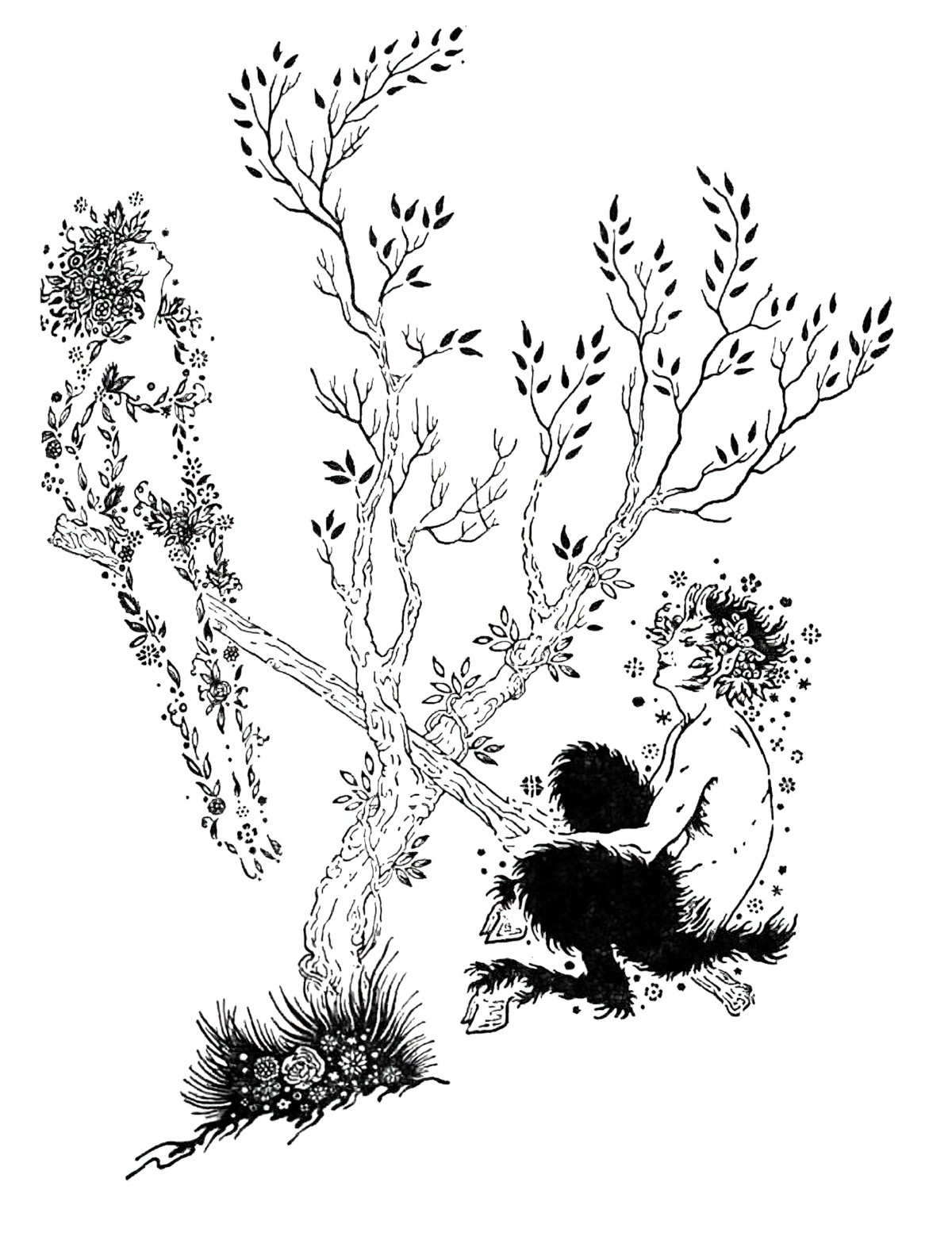

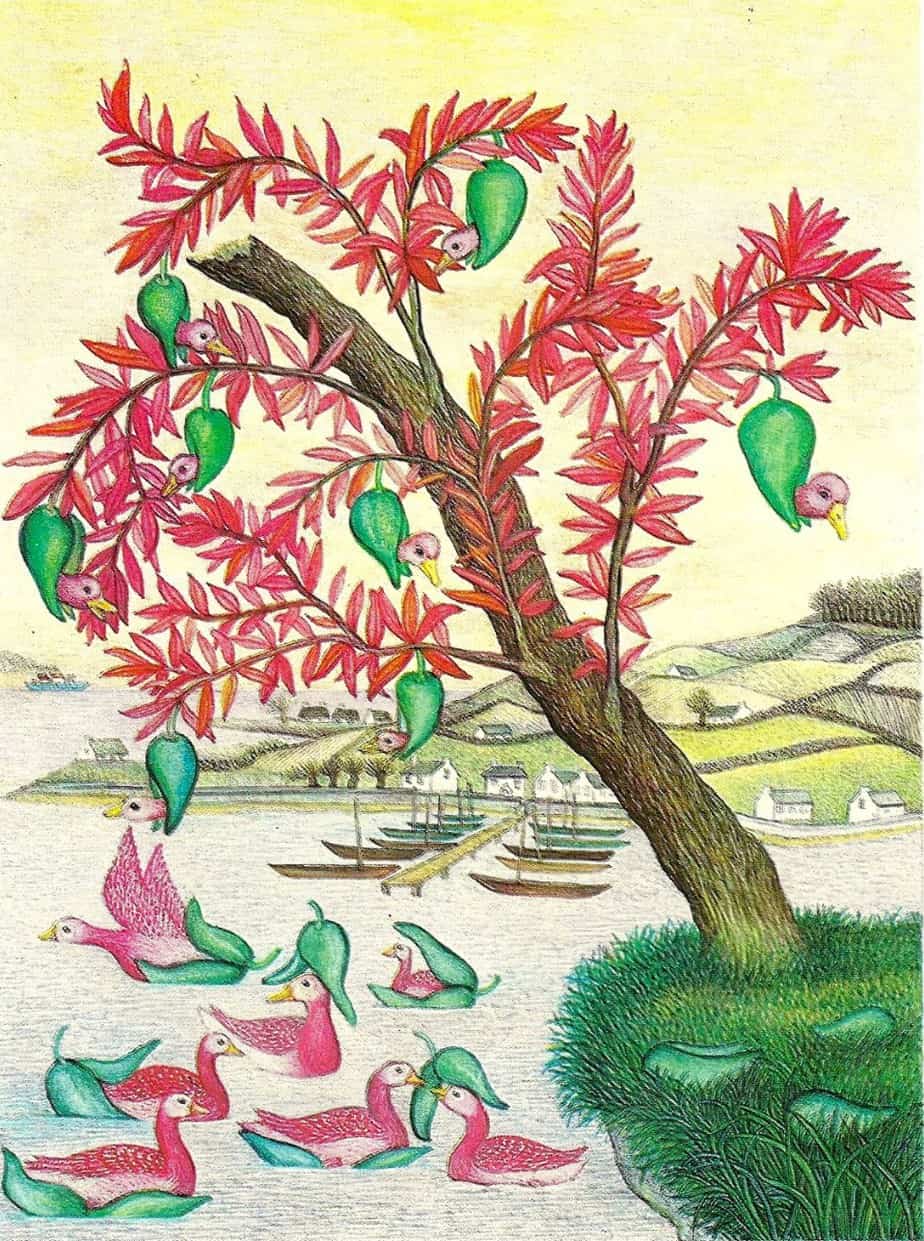

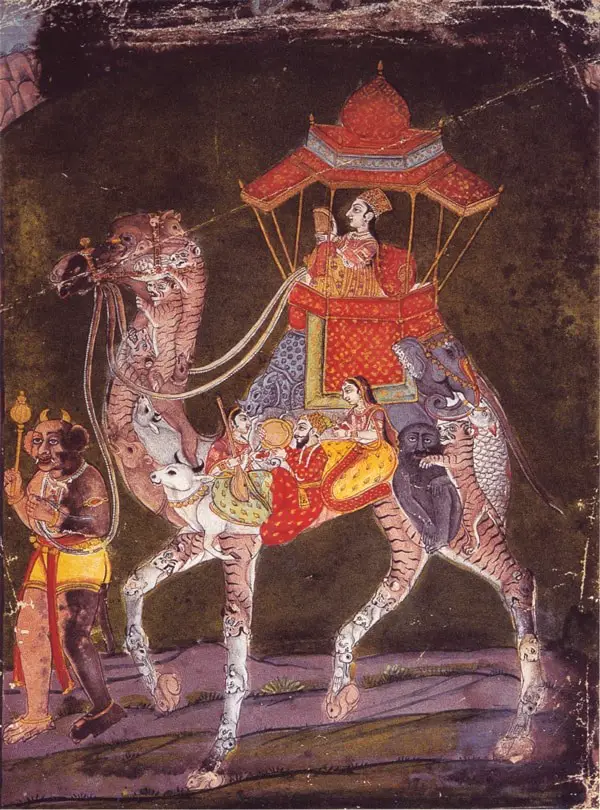

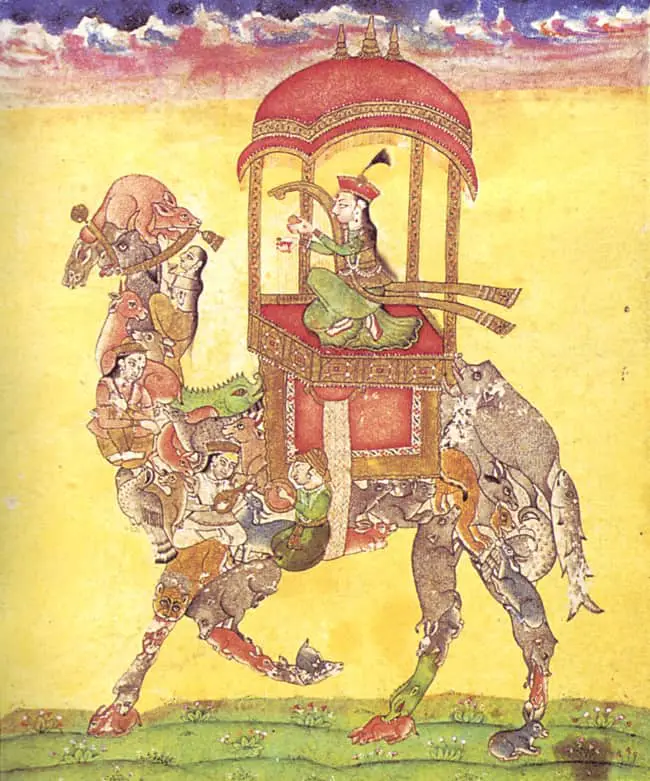

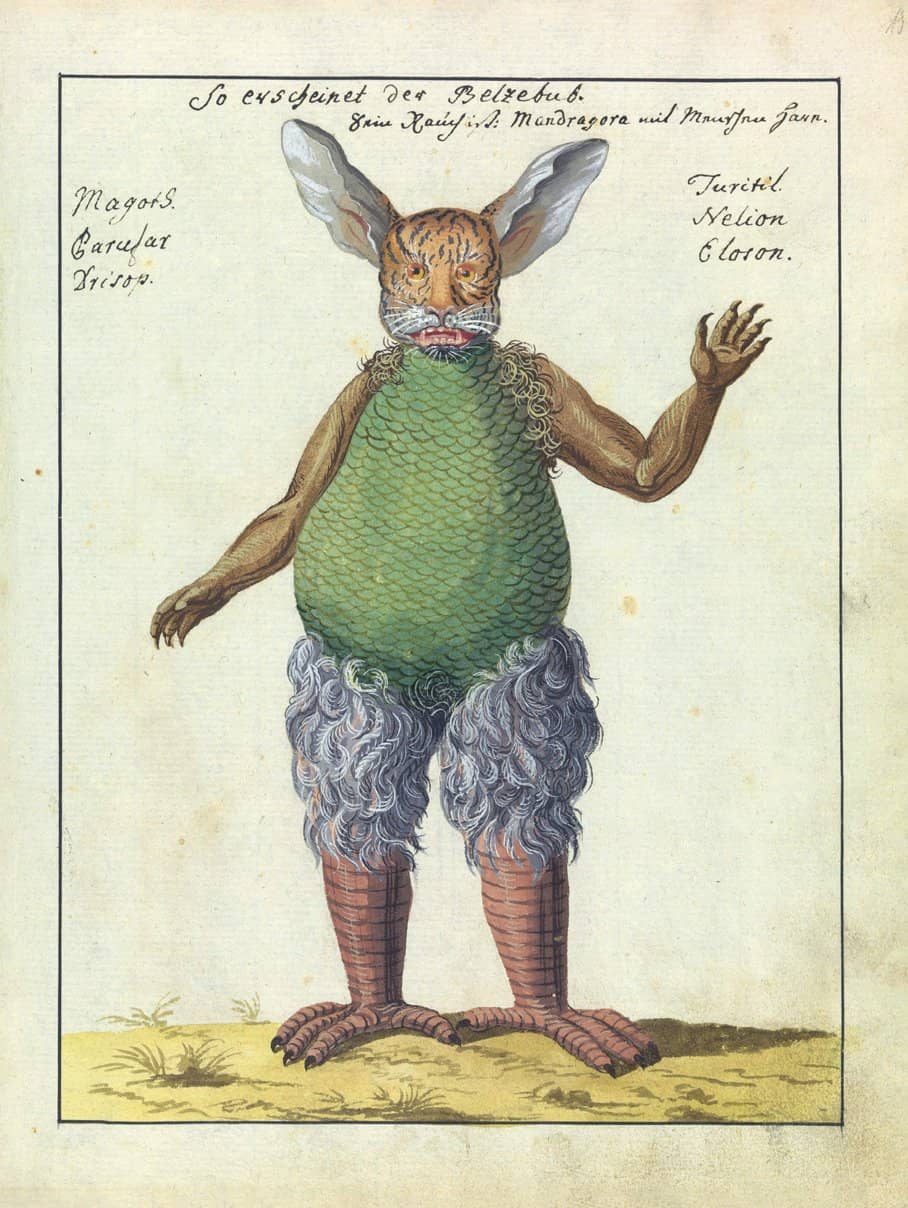

A drollery — yes, it’s related to the word ‘droll’, is a decorative thumbnail image in the margin of an illuminated manuscript. They were most popular from c1250-15th century. The most common types of drollery images appear as mixed creatures: several different animals, part human, part animal, or part animal, part plant. Or even other, inorganic things.

Without chimeras, many of the most memorable science fiction and horror films would have been impossible, writes Howard Suber. A chimera was an ancient Greek monster with the head of a lion, the body of a goat and the tail of a serpent.

Dragons are a subset of a chimera, being made up of lions, serpents and birds. A great number of characters in myth, legend and folk tales are chimeras.

Drolleries often have a thematic connection with the subject of the text of the page, and larger miniatures, and they usually form part of a wider scheme of decorated margins, though some are effectively doodles added later. Here’s an example from elsewhere:

THE FUNCTION OF CHIMERA IN A STORY

Throughout history, hybrid creatures have functioned as remarkably versatile vehicles for the expression of abiding cultural anxieties. On many occasions, they have been rendered just about tolerable by the sublimation of their uncanny anatomies into so-called “curiosities.” Yet, this has frequently led to a paradoxical situation, insofar as our attraction to those beings’ intractable alterity is never conclusively anesthetized: much as we may seek to domesticate the threatening connotations they are held to carry, by relegating them to the province of the abnormal or the repulsive, the sense of menace abides as a vital component of their bizarre, monstrous and fearful beauty. In other words, hybrids’ attractiveness is inextricable from their intimidating power.

Dani Cavallaro, Magic as Metaphor in Anime: A Critical Study

The most important thing to understand about these metaphorical creatures (and other metaphorical symbols in general) is that they also represent something within the hero.

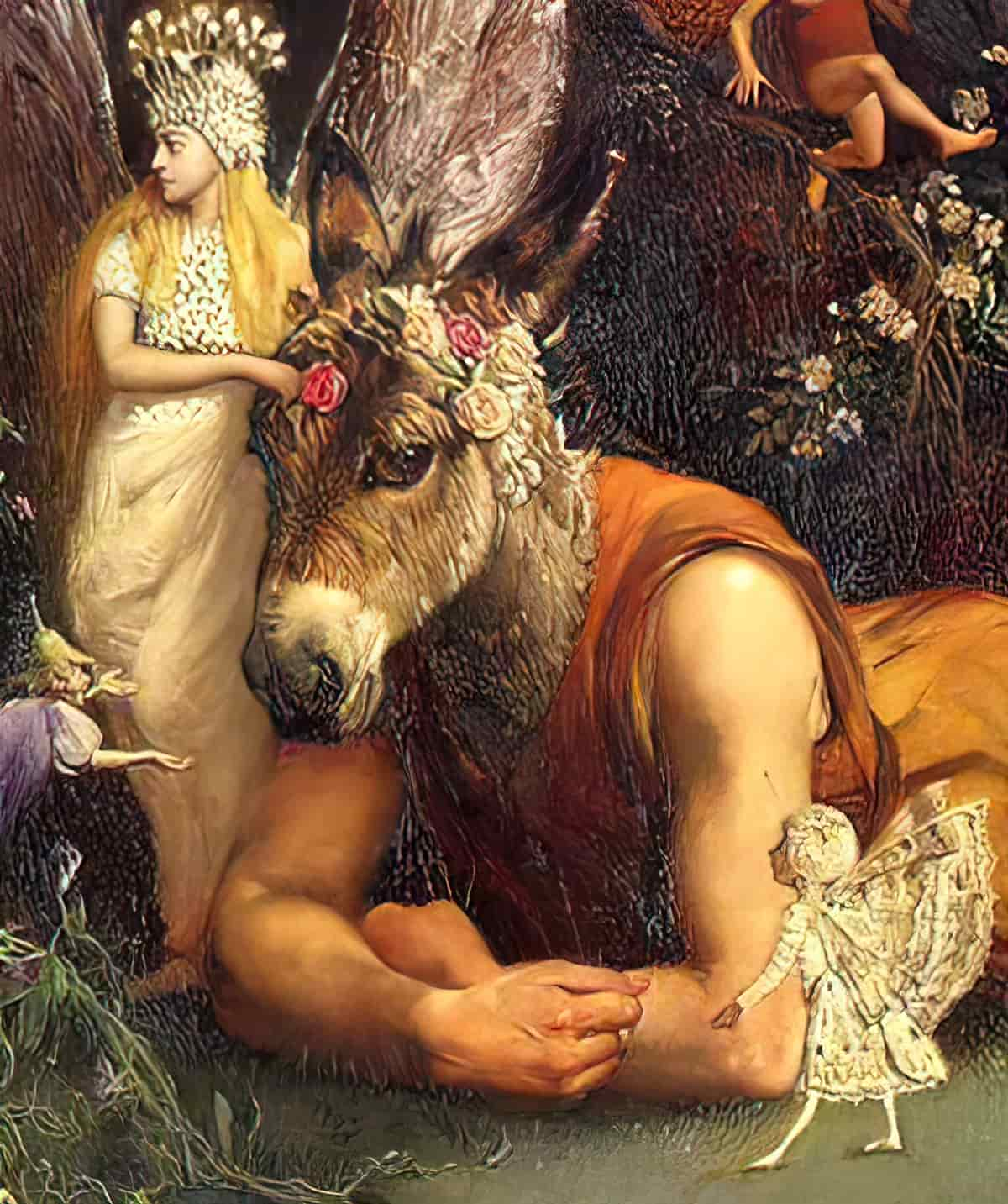

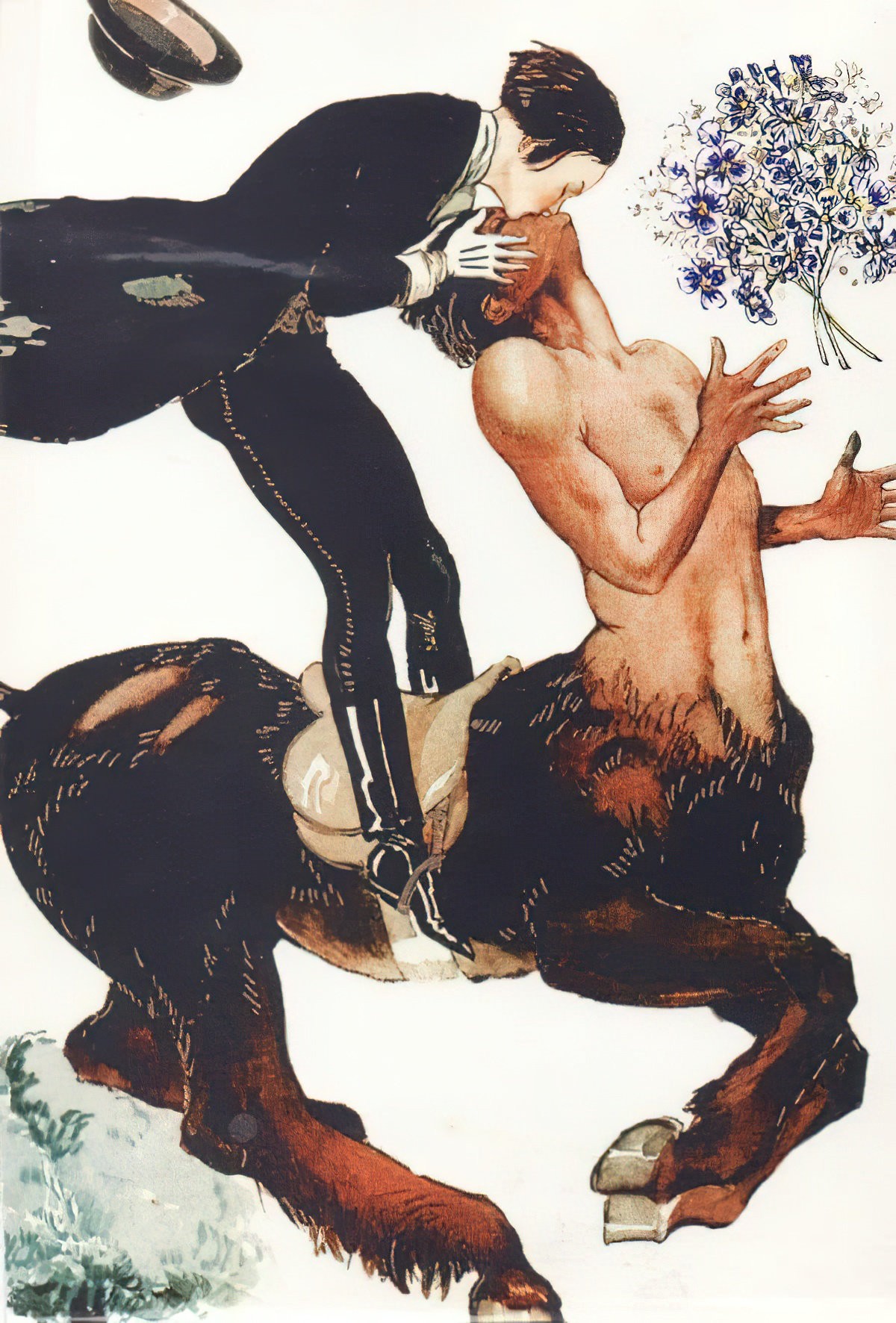

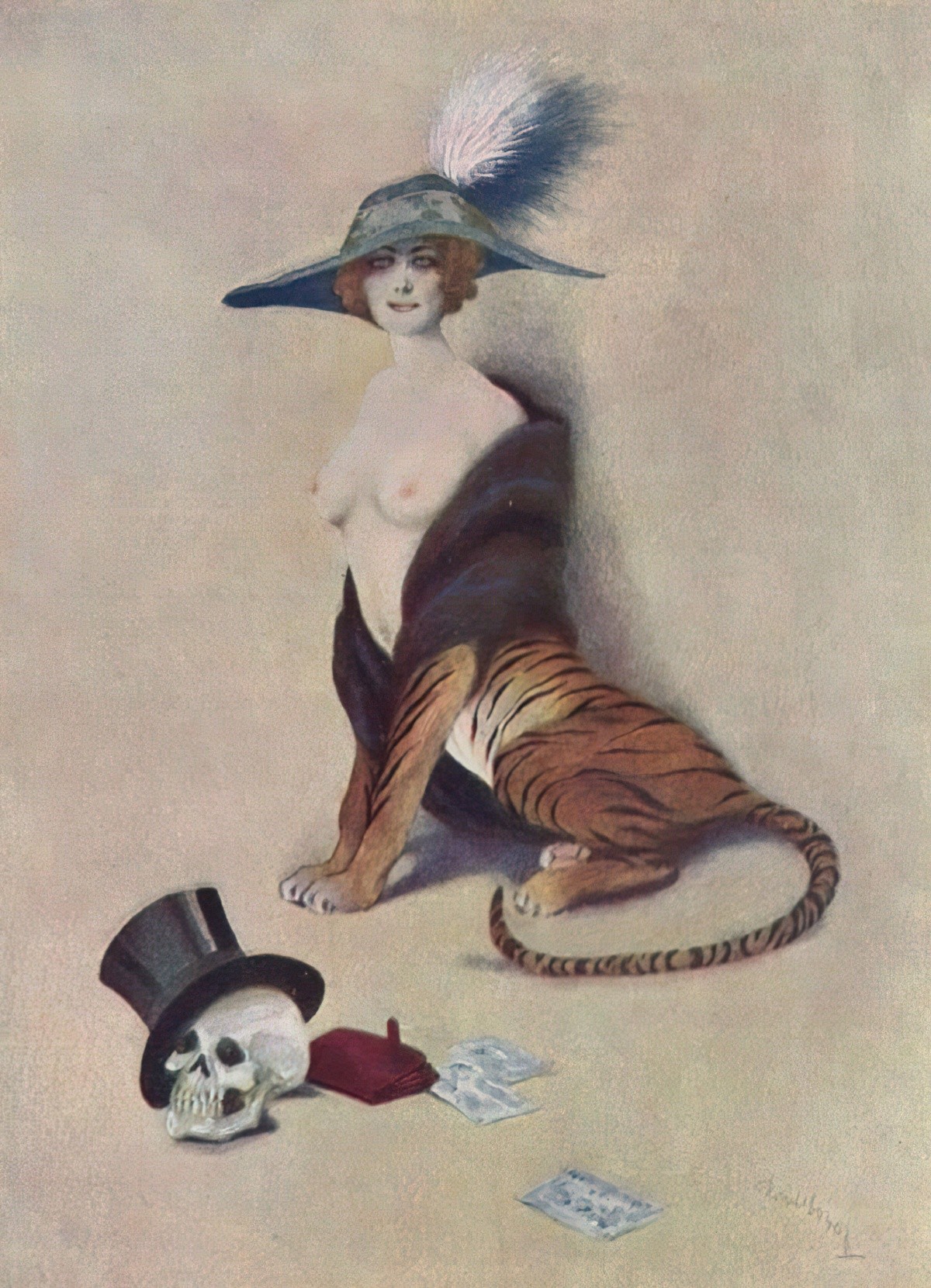

One way to tame the fearsome chimera is to turn it into a sexual object. This happens regularly with femme coded chimeras but this occasionally happens with the masculo-coded centaur as well. There is a chapter in “The Wind In The Willows” about a sexualised Pan, sometimes left out of editions marketed to children.

In modern vampire stories, e.g. Twilight, the male werewolf might be considered a kind of sexually objectified chimera. In this case, the human turns wholly into a beast, then wholly back again. Apart from in the process of transformation itself, the body is complete.

But what, exactly, is the appeal of this eroticised centaur? What’s that about?

The feet are where the body ends and the ground begins. They are part of the lower body, the belly, the genitals, the anus, and associated with all three. This is one reason why feet and legs are eroticized in many cultures. Such bodily lowness is also symbolized by the fact that many of the odd feet of demons are animal feet; classical mythology abounds with creatures whose lower bodies are animal and their upper bodies human; satyrs, centaurs, fauns, silenoi, and the god Pan, are all associated with sexual licence.

Diane Purkiss: Troublesome things: A history of fairies and fairy stories

The winged monkeys in The Wizard of Oz are a kind of children’s book chimera. The novel by L. Frank Baum is famously open to interpretation. Everything seems like a symbol.

The flying monkeys is a tern now used in pop psychology when talking about narcissistic abuse:

Flying monkeys … are people who act on behalf of a narcissist to a third party, usually for an abusive purpose (e.g., smear campaign). The phrase has also been used to refer to people who act on behalf of a psychopath, for a similar purpose. The term is not formally used in medical practice or teaching.

Abuse by proxy (or proxy abuse) is a closely related or synonymous concept. The term is from the flying monkeys used by the Wicked Witch of the West in the 1939 film Wizard of Oz to carry out evil deeds on her behalf.[

Wikipedia

WHAT ARE THE BESTIARIES?

A bestiary, or bestiarum vocabulum, is a compendium of beasts. They came from the Ancient world, and became popular in the Middle Ages. Illustrated volumes describe various animals, birds and also inanimate things like rocks. Each beast gets its own illustration, a natural history and tends to end with a moral lesson (similar to Aesop fables).

Bestiaries are Hellenic, Asian and Egyptian in origin. Each illustrator from the 8th century onwards has added flourishes and sometimes given them weirdly humanised faces.

Nearly every animal in a Bestiary was symbolic of a human virtue or vice. So these beasts tend to be divided in binary fashion into good and wicked.

Beasts like minotaurs, harpies and centaurs belong to stories of gods and heroes that have been translated into English without being changed or used, apart from the kind of imaginative transference whereby a poet like Gavin Douglas could make the Aeneid sound as if it were happing in Scotland.

Margaret Blount, Animal Land

In the old days, chimeras were mostly made up of different animal parts.

For example, the minotaur is a creature from Greek myth with the head of a bull and the body of a man.

Heraldic creatures or mythical mixtures of parts are supposed to have been created that way, complete and finished. But creatures that have grown warped and monstrous with time and misfortune symbolise too much that is warped in human nature for comfort.

THE CHIMERA AND HUMAN PSYCHOLOGY

Nicoletta Ceccoli is an artist who paints a lot of chimeras. Here she explains why she is drawn to them:

I often depict lonely weird sad creatures. Half woman, half monster. The characters in my pictures are kind of my alter ego. I’ve never felt comfortable with my own body, and I have fought with these feelings all my life. When I was an adolescent I often had the sensation of being a ‘freak’; I felt a sense of isolation, of being lonely and closed in my own thoughts. This brought me to feel a connection with those people who looked foreign to society. The word ‘normal’ scares me a little. In the film ‘Freaks’ by Tod Browning, the idea of man and monster is reversed: the human cruelty of so-called normality is monstrous, not the morality and goodness of the ‘others’. I feel an affection towards creatures that are unusual.

MODERN CHIMERAS

Modern chimeras are different: Frankenstein is a man merged with different bodies.

As Margaret Blount writes in Animal Land:

Minotaurs and others of half-human appearance do not seem to have travelled well enough to transplant themselves into stories. But they, and other animals made up from a mixture of parts, seem to have been accepted as facts in the popular Bestiaries; the descriptions proliferated in the telling with all the force of apparent eye-witness accounts, permeated with religious symbolism which lends them awe and wonder.

Chimera in Victorian Children’s Literature

Edward Lear invented quite a few creatures, and we’re not sure what they’re made up of:

- The Dong — Edward Lear’s “The Dong with a Luminous Nose”

- The Quangle-Wangle — Edward Lear also wrote a poem called The Quangle Wangle’s Hat

- Mock Turtle — from Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland — named after ‘mock turtle soup’, a dish popular in the Victorian period

These made-up creatures were particularly useful to writers who loved to make up words: Lear, Seuss, Carroll and Sendak.

- Psammead — from Five Children and It — a sand fairy who can grant three wishes (Nesbit)

- Melvyn Peake, who wrote Captain Slaughterboard Drops Anchor in 1945 also made up a bunch of animals for the story such as the Yellow Creature.

- The Mr Neverlost books by A. Turnbull (1932-1934) are early Dr. Who stories. Impossible creatures show an interest in humans as specimens. (Science fiction treated as fairy tale.)

- Then of course we have the strange creatures from Dr. Seuss, such as The Lorax, who might be a cross between species — a land dweller who looks like of like something from the deep ocean. One reviewer describes the Lorax of the film adaptation by saying “Danny DeVito voices the Lorax, a mustachioed, tangerine-coloured being that looks like a cross between Wilford Brimley and a potato with a spray tan.” Or maybe The Lorax is a type of walrus without the tusks.

Chimeras In Modern Film

- The Fly

- Alien

- The Terminator

- The Matrix

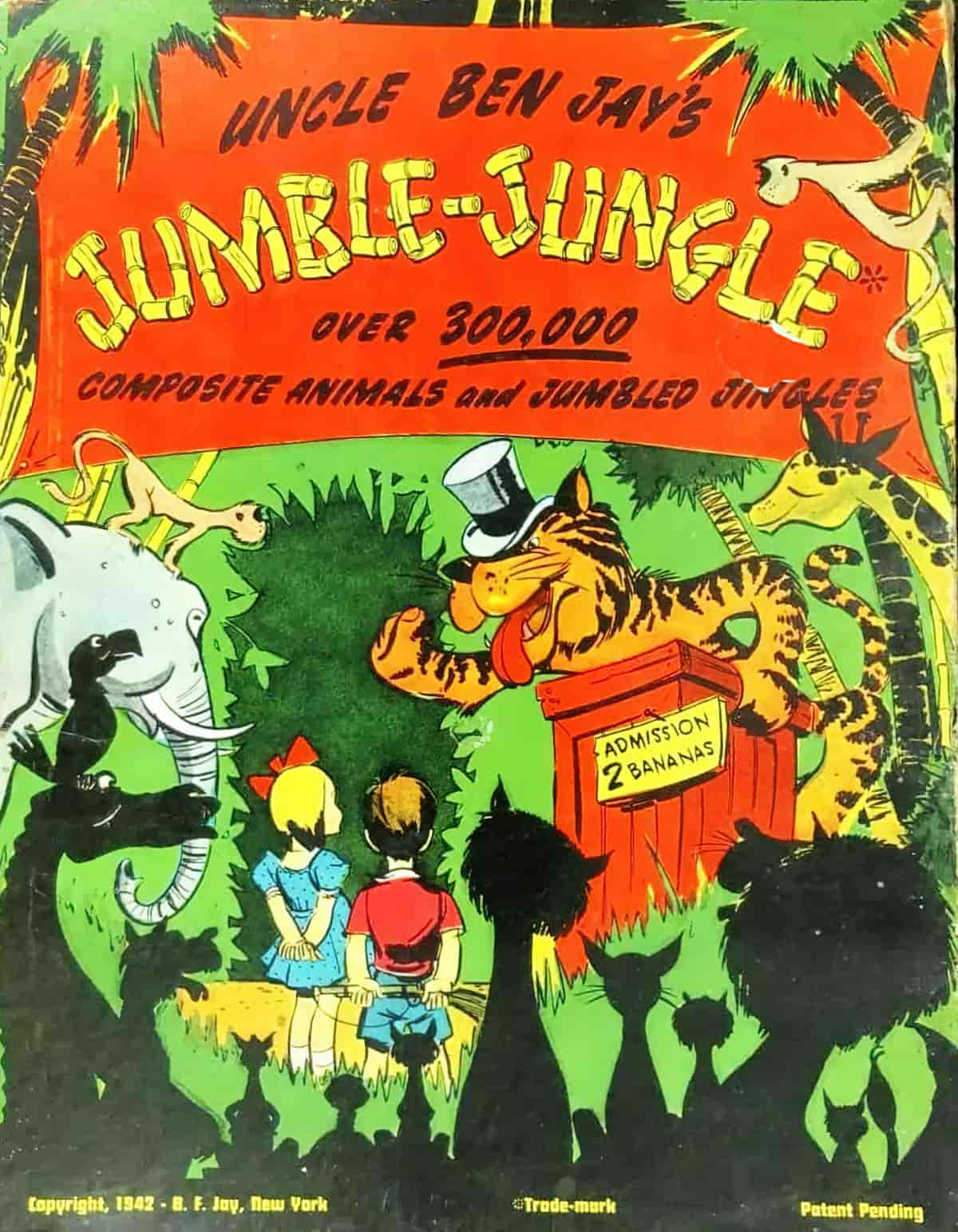

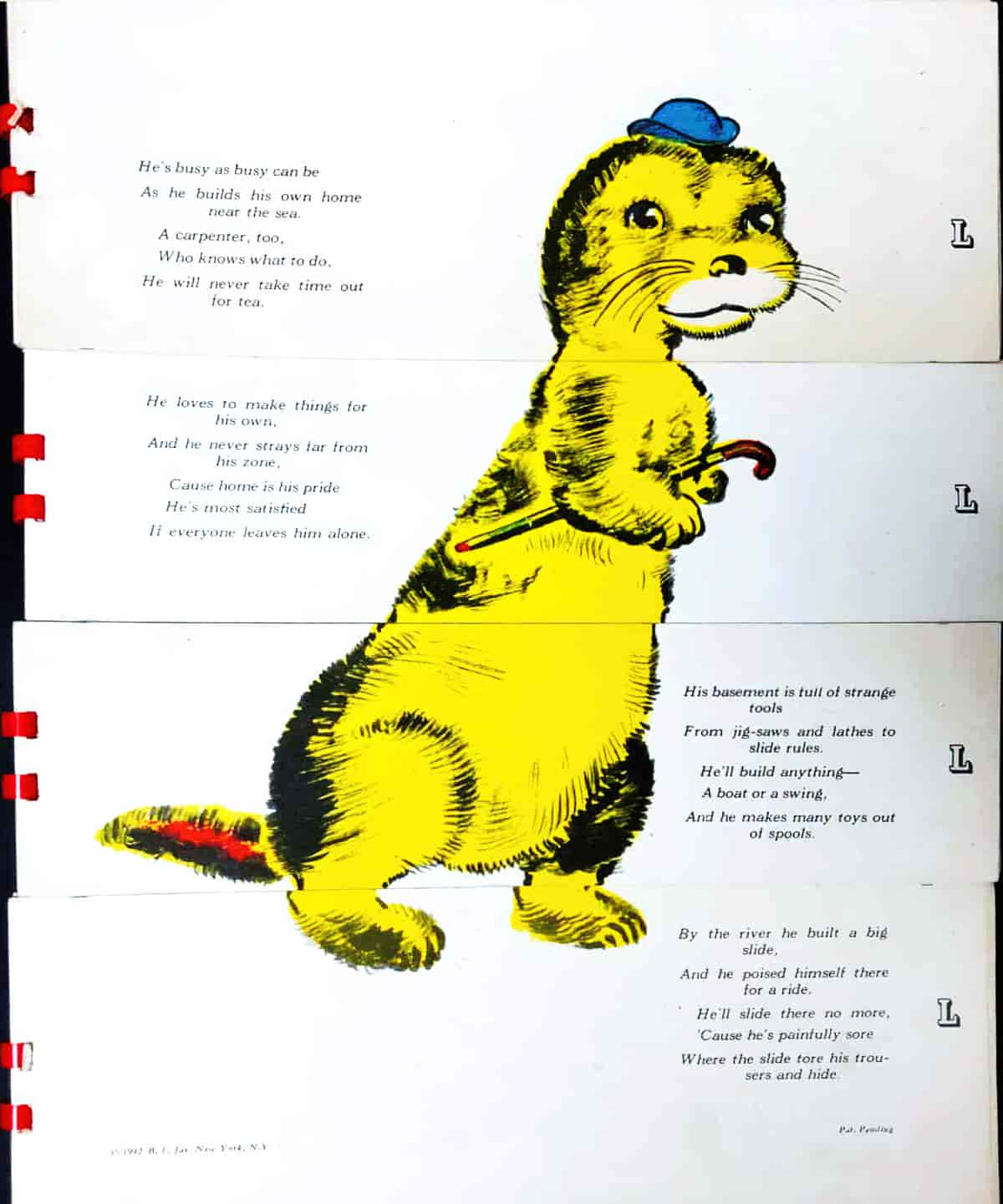

Chimeras in Picture Books

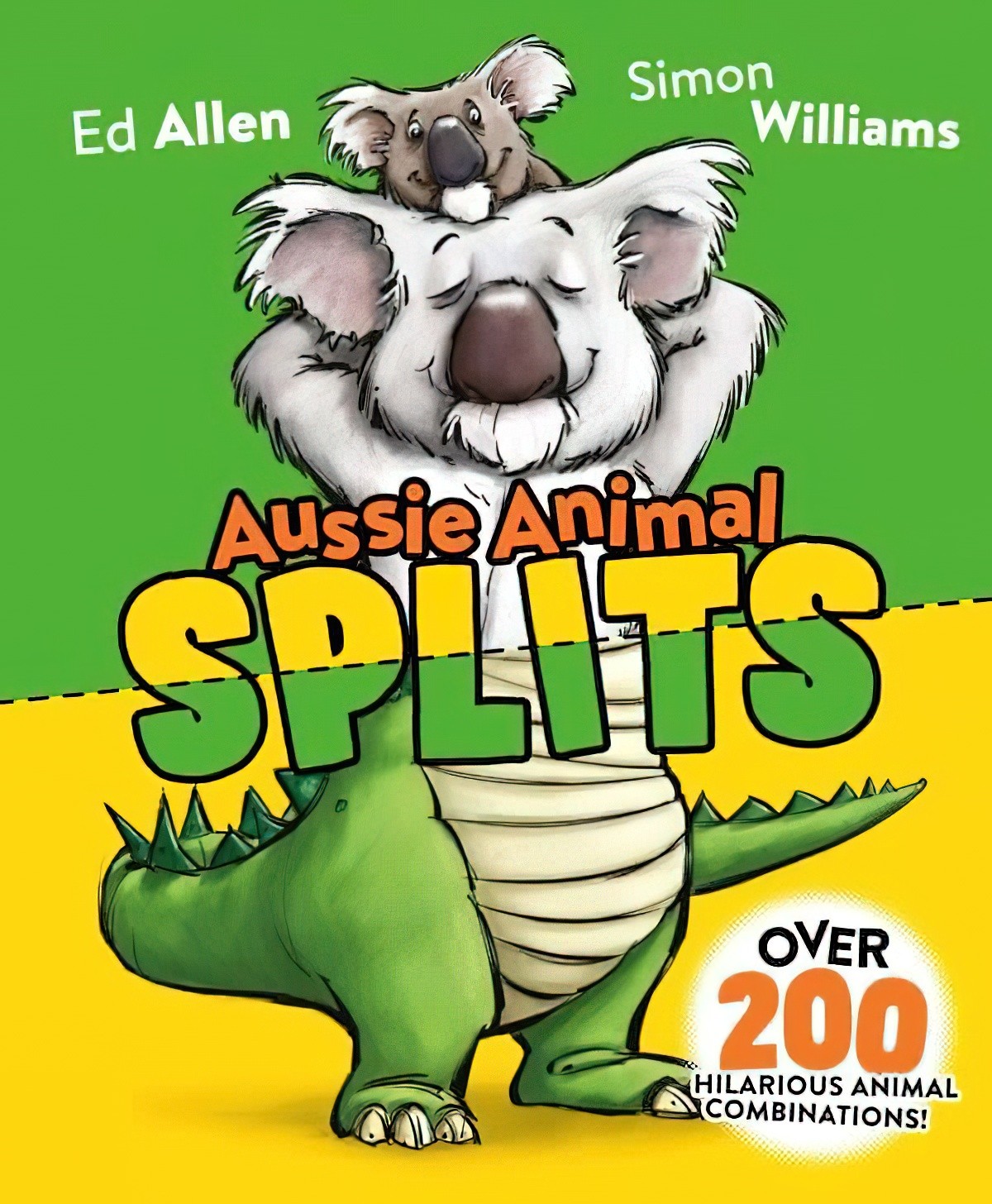

Not all chimeras are scary. Today there are ‘toy books’ with split pages in which the young reader is able to create their own chimera by pairing an animal head with a different animal’s body/legs.

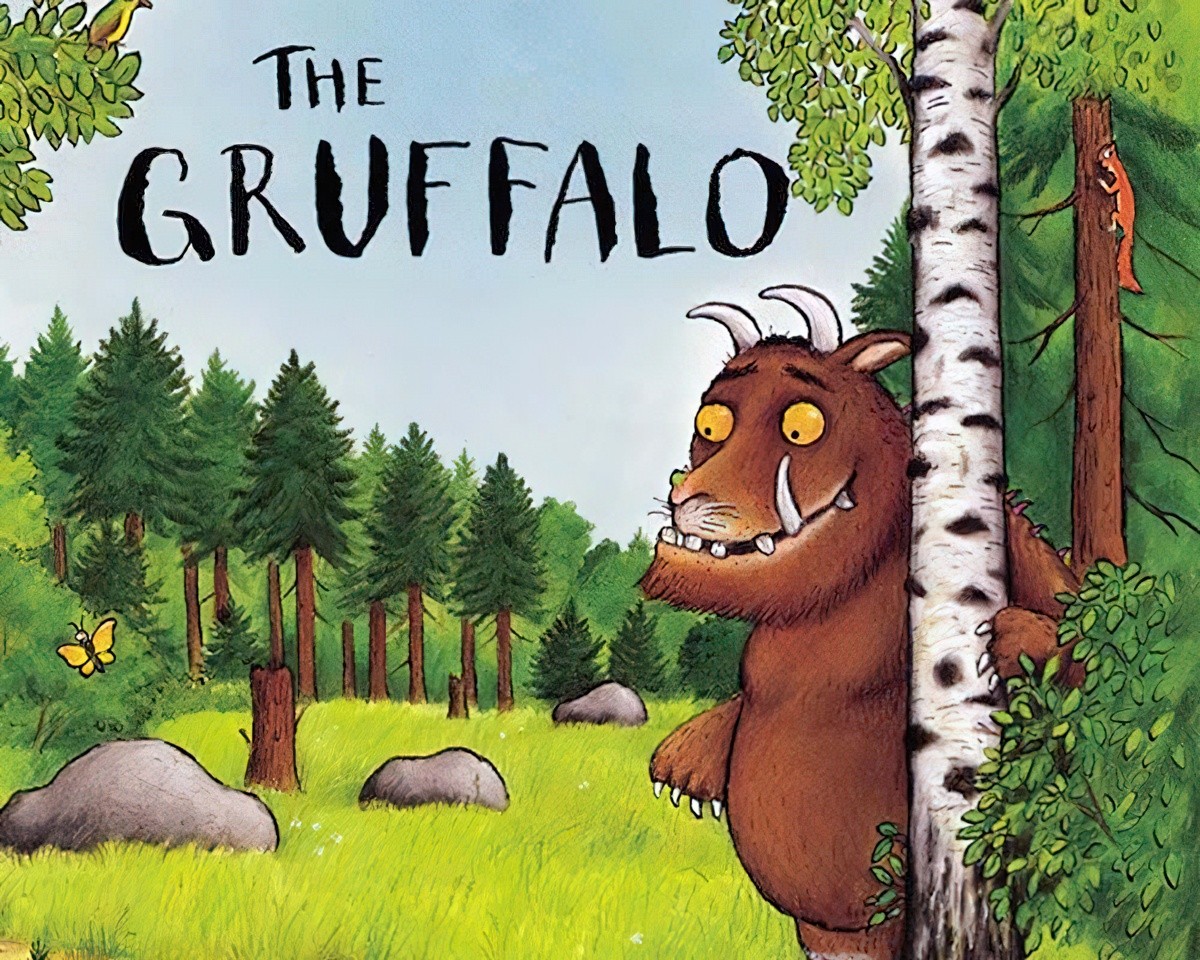

Julia Donaldson and Axel Scheffler’s Gruffalo also seems to be a kind of chimera, and a portmanteau word made from a blend of ‘Gruff’ and ‘Buffalo’. Gruff, of course, is not a creature but an adjective. But this is still a riff on the ancient chimera.

In general I would say that entirely made-up creatures are less terrifying than real ones. Contrast The Gruffalo with Blackdog by Levi Pinfold, in which a massive dog looks in through the window of a cosy house.

The Chimerical Home

In Poetics of Space, Gaston Bachelard briefly mentions the term ‘chimerical home’, which obviously means a bit from one type of dwelling added onto another type of dwelling. An example of a chimerical home would be a house boat. Another would be a tree house.

RELATED TERM

ADDITIVE MONSTER: In contrast with the composite monster, mythologists and folklorists use the label additive monster to describe a creature from mythology or legend that has an altered number of body parts rather than body parts from multiple animals added together. For instance, the Scandinavian Ettin, a troll or giant with two heads, is an additive monster. Sleipnir, the magical horse in Norse mythology, is a regular horse, except it has eight legs. Deities and demons in the Hindu pantheon often have multiple arms or eyes. The term has also been loosely applied to fantastic creatures that have modified limbs as well. For instance, the gyascutis is a fantastic medieval beast that resembles a sheep, except its limbs vary in length. Its front legs are drastically shortened, and its hind legs are drastically lengthened, which allows it to remain level as it grazes on the incline of steep hills.

Literary Terms and Definitions

FOR FURTHER INVESTIGATION

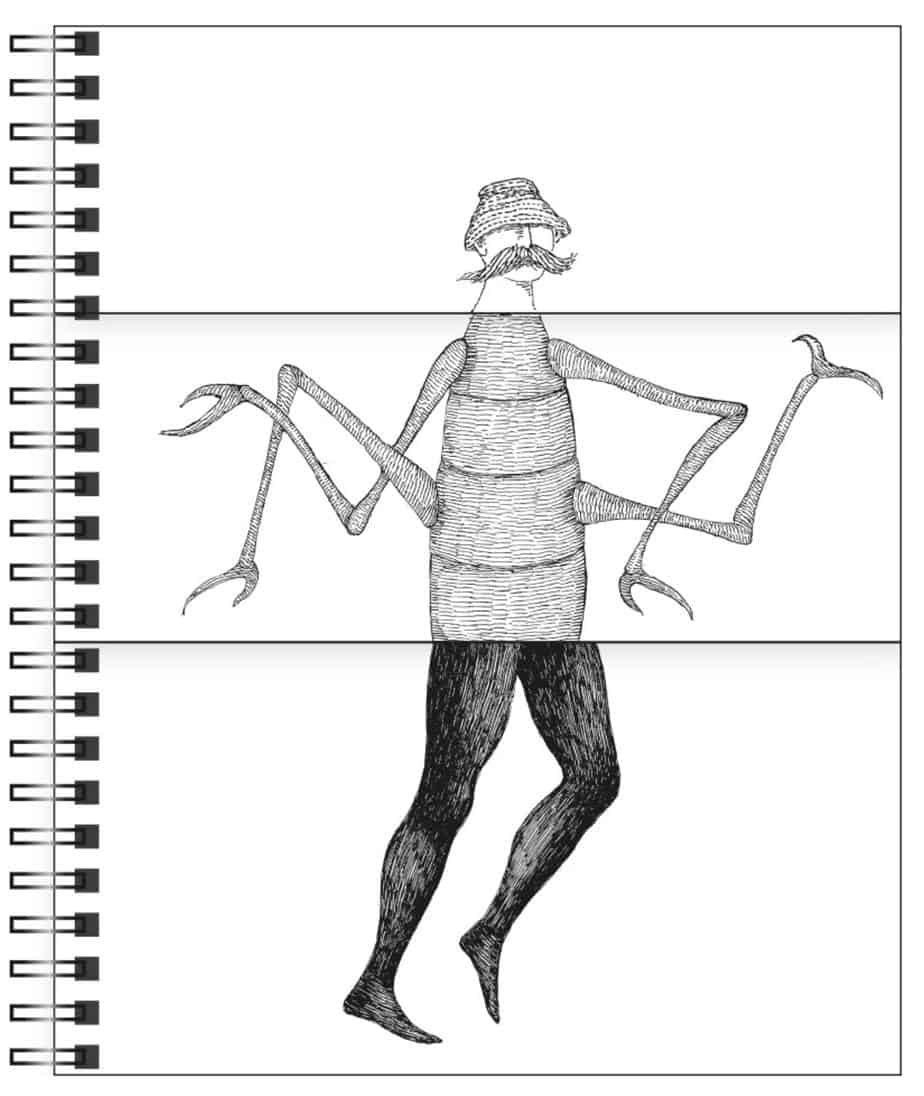

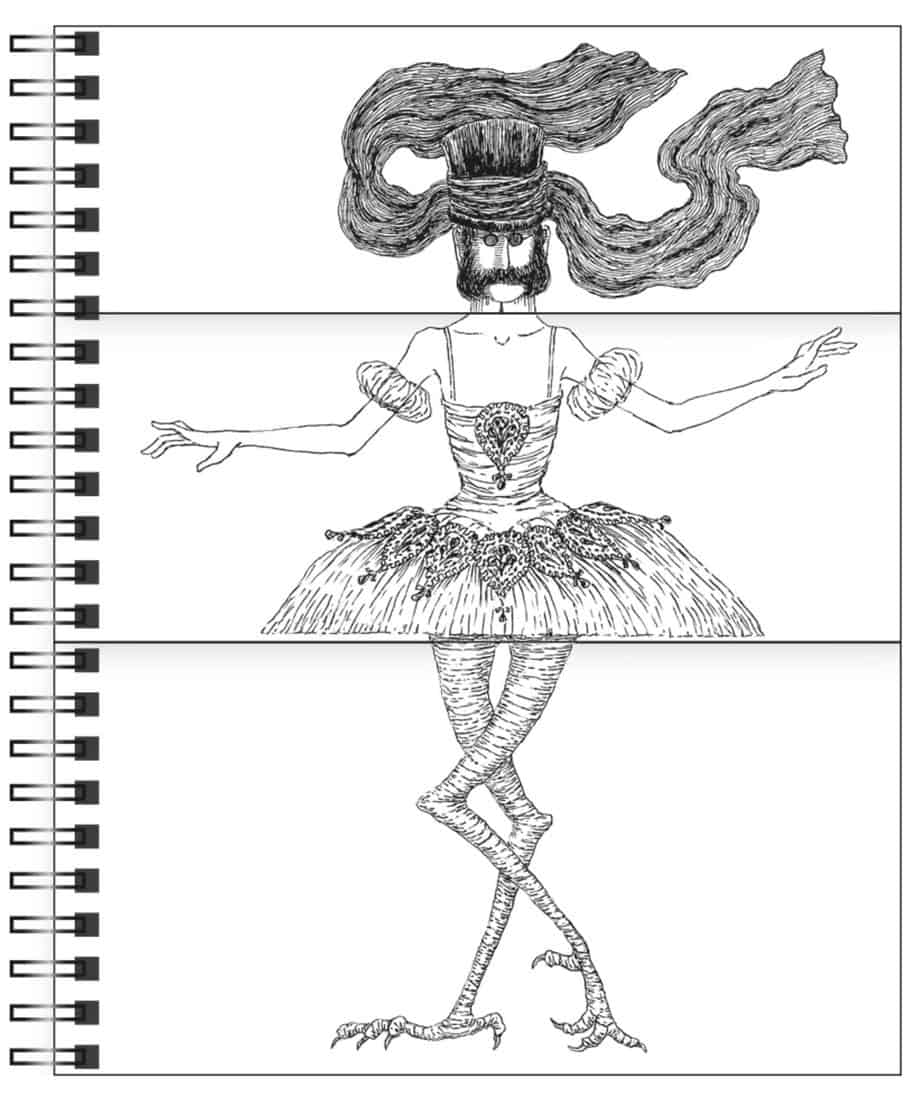

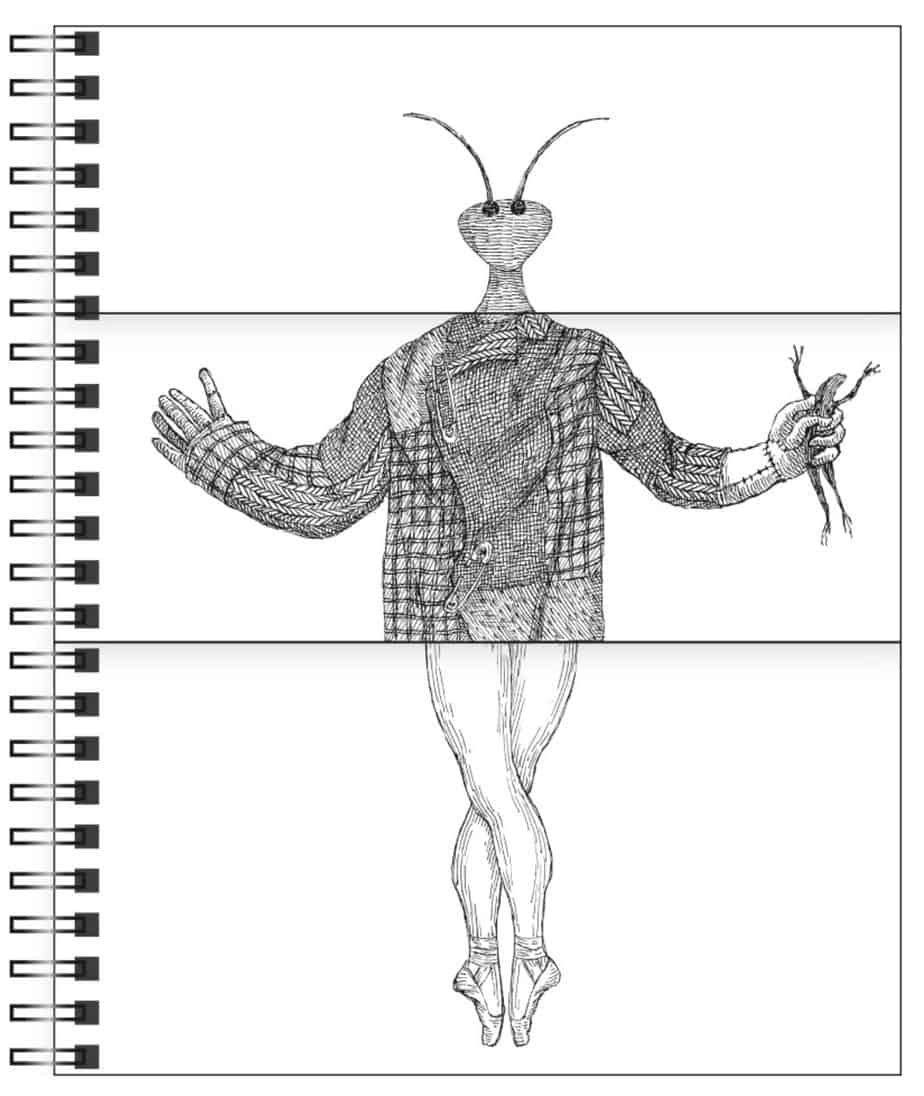

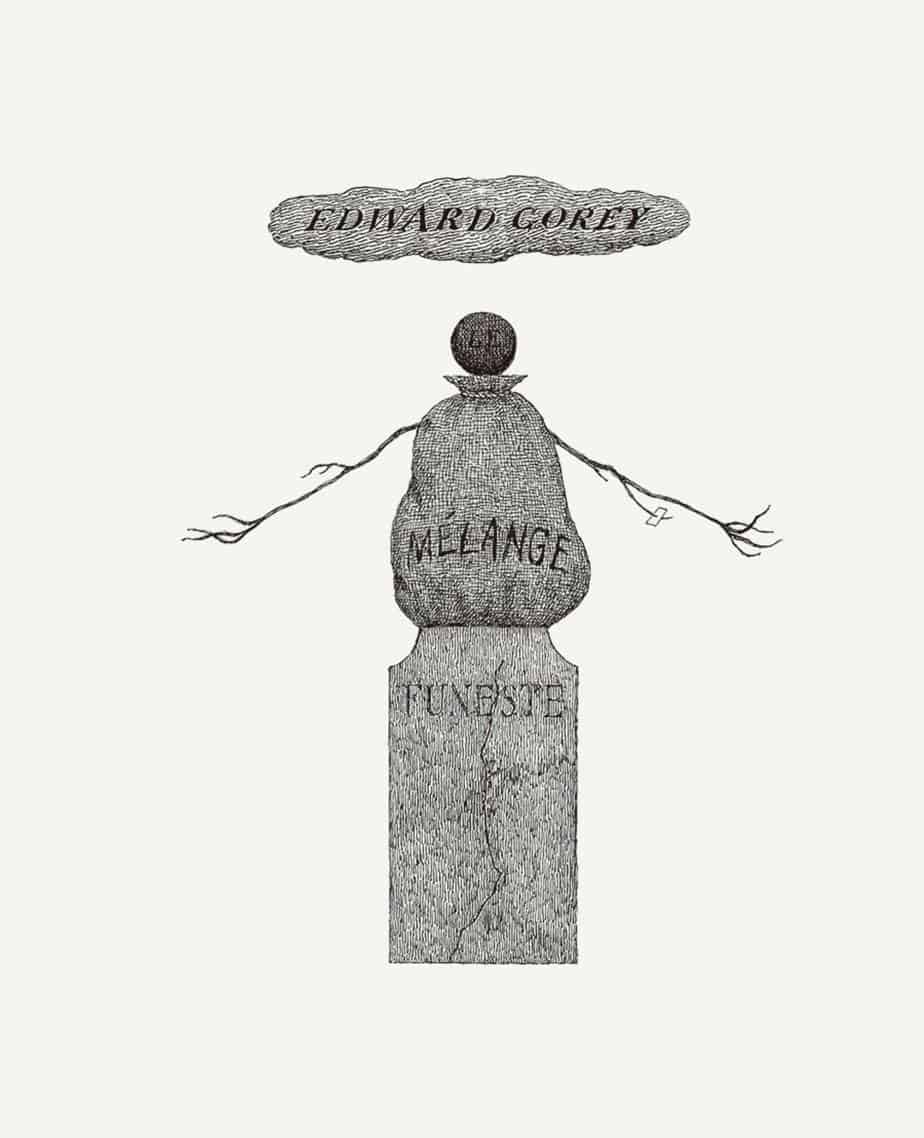

Sixteen images to flip, mix, and match in a Wire-O bound hard cover book. Sixteen bizarre creatures are combined in extraordinary ways in Edward Gorey’s Mélange Funeste, which could be translated as “The Dreadful Mixture.” Each intricately drawn figure has been divided into three parts and mixed up. Flip the parts and make the figures whole again…or create new combinations of head, torso, and legs.

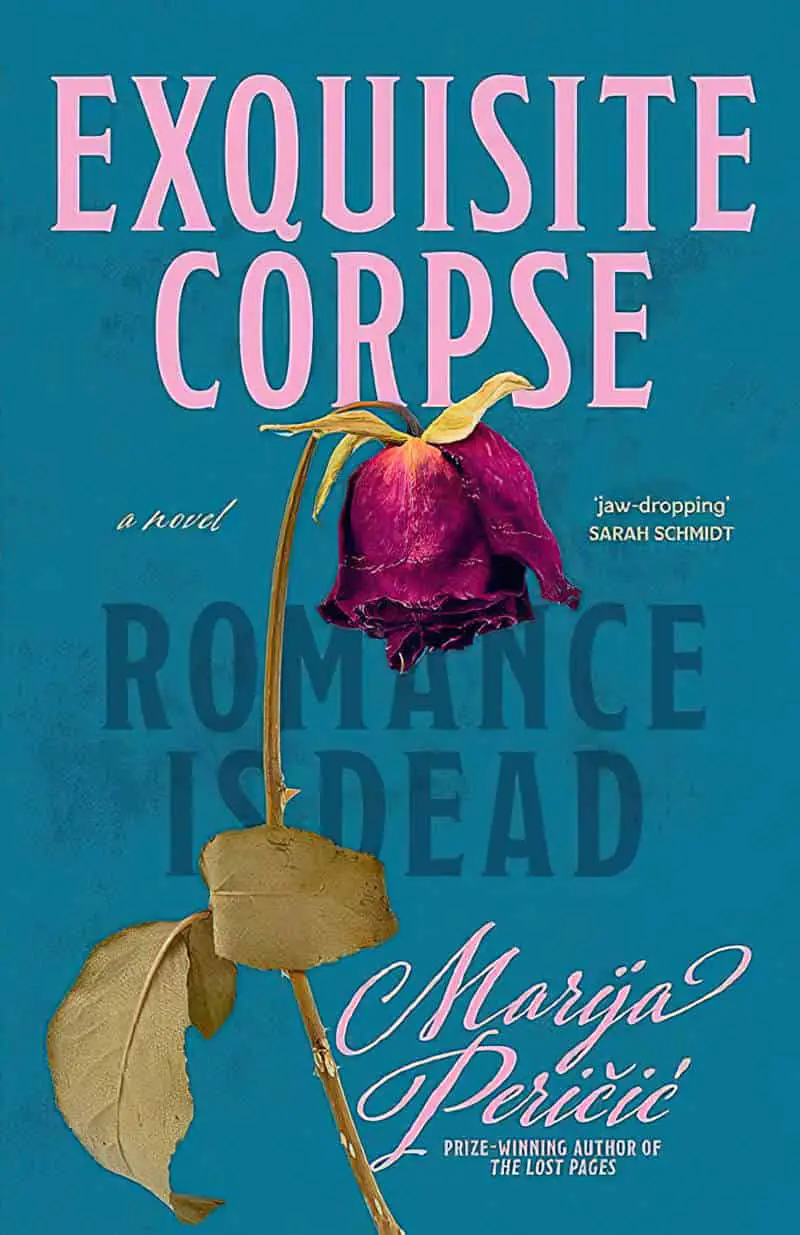

THE EXQUISITE CORPSE GAME

Exquisite corpse, also known as exquisite cadaver (from the original French term cadavre exquis), is a method by which a collection of words or images is collectively assembled. Each collaborator adds to a composition in sequence, either by following a rule (e.g. “The adjective noun adverb verb the adjective noun.” as in “The green duck sweetly sang the dreadful dirge.”) or by being allowed to see only the end of what the previous person contributed.

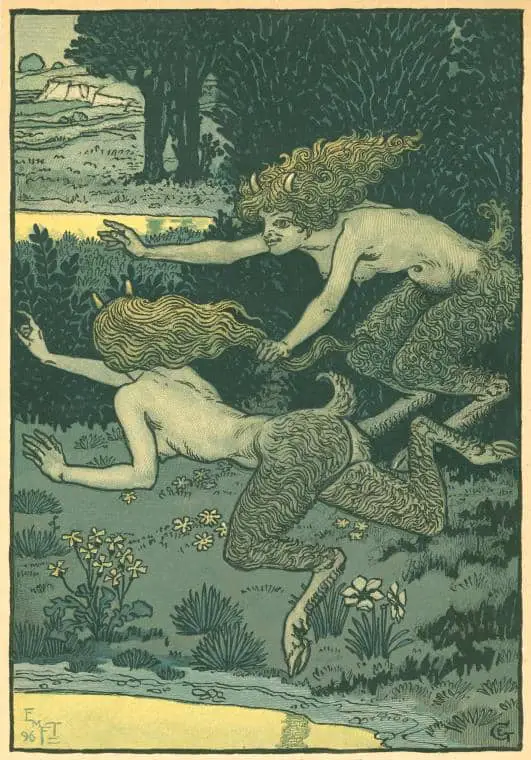

Header painting: Les petites faunesses (The Little Faunesses) by Eugene Grasset