The Power of the Dog is a 2021 film directed by Jane Campion, based on the same-named 1967 novel by Thomas Savage. Like a lyrical short story, this film is designed for a repeat viewing. The plot and characterisation both made so much more sense to me the second go around, but at 2 hours and 6 minutes, you may not have the time to watch it twice, in which case, welcome!

Added to that, this is a pretty heavy watch, with signature Campion violent moments smacking you upside the face without warning. (If you’ve seen The Piano, you’ll remember the finger.)

See also: Films That Centre Characters Over 40

WHY DOES THIS FILM REQUIRE A REPEAT VIEWING?

Don’t feel stupid for failing to pick up every aspect of the ending, or why characters behave the way they do. People who watch a lot of film are saying this one requires a second viewing to truly understand.

That’s because The Power of the Dog is heavily symbolic, and makes much use of foreshadowing. You’re pretty good at picking up foreshadowing, you say? Yeah, me too. That said, there’s a subset of foreshadowing which is set up for ‘delayed decoding‘. This is a variety of foreshadowing not actually designed to be meaningful until the audience already knows the ending of the story. Certain short story writers are masters at this, and this is why your high school English teacher insisted every short story must be read at least twice. (I came across the term ‘delayed decoding’ when reading criticism on the short stories of Annie Proulx.)

The Power Of The Dog works with regular ole foreshadowing, too, by the way. A contemporary audience will sense that because there is death of a small animal (rabbits), there will be death of a human before the movie’s end. This is such a common trope that to kill a rabbit and then fail to kill a human would be a subversion of audience expectation on the author’s part.

Moreover, this is a story which also takes universal symbols and turns them into something a little different. There’s the Chekhov’s gun of the rope. What does your mind conjure up when you think ‘Western setting’ and ‘rope’? Hangings, I bet. That’s not what this particular rope is used for. More on that below.

Should a film require two viewings before the majority of the audience understands it? That’s a different question. I can tell you I enjoyed this one more the second time.

But if I’d paid for a full price ticket to see it once at the movies and couldn’t go home to see it again the following week? Maybe I would’ve been annoyed. But in the age of streaming services (and covid) perhaps we’re about to see a return of the lyrical, highly symbolic arthouse film which requires more than one session.

BUT MY COUSIN INSISTS THE POWER OF THE DOG IS RIDICULOUSLY PREDICTABLE

You may have met people who insist the plot of The Power of the Dog is ‘predictable’ or ‘obvious’. (Perhaps you’re one of them?)

I believe viewers are responding to the arc, not to the delayed decoding around character, because this is a ‘twist’ which contemporary viewers have seen many times before. Thomas Savage’s book, upon which this movie is based, was published back in 1967. Whatever feels original upon a work’s publication rarely feels original 64 years later, for the simple fact that storytellers (subconsciously) copy other people’s plots.

I’m talking about the plot of queer lateral violence.

[Phil] is in an impossible situation of being an alpha male who is homophobic and also homosexual. It’s incredibly painful and complicated. I found Phil moving and I found the mysterious relationship between him and the boy exciting and satisfying.

Jane Campion

We are no longer surprised when the biggest homophobe of a narrative turns out to be gay himself. You can probably point to numerous real life examples e.g. the guy who murdered Harvey Milk. Certain politicians who seem to exist in every country: They’ll bleat on and on about family and then a paparazzo will catch them doing the exact thing they purport to despise. We mistakenly think that disgust and attraction are different ends of a linear spectrum, but it’s far more complicated than that: Some people require disgust in order for attraction to kick in.

So yeah, I’m starting to get a little leary of these ‘plot twists’ myself, in which the most terrible bully is only a bully because he’s trying to protect his own position in the gender hierarchy. Once the dominant culture reaches a critical mass of plots in which ‘the worst character is himself gay’ it becomes part of the collective consciousness to the point where people say of the worst real life bigots, oh, he must be secretly gay. (If that were the case, we must expect the Westboro Church to be chocka full of gay people.)

For the record, I don’t believe that the worst homophobes are secretly gay themselves. (I also despise the cliche: “Women are each other’s worst enemy.” No. Misogyny is an entire system of power with many moving cogs in constant motion.)

To guess at anyone’s orientation without having been told, by themselves, and then to try and out that person as retribution, is yet another kind of violence. And although we may feel justified in our punishing bigots by outing them, it’s a terrible mental habit to fall into.

By the way, Squidward of SpongeBob Squarepants is the cartoon, comedic equivalent of Phil. Squidward feels contempt for SpongeBob, who enjoys life as himself, uninhibited. We sometimes get glimpses of Squidward wanting what SpongeBob wants, loving the same things, but he is never able to. He continues to mistake his envy for contempt, and this is his tragedy.

IS THE POWER OF THE DOG REALLY A ‘WESTERN’?

[Savage’s novel] intrigued me for many reasons: I couldn’t guess what was going to happen, it was incredibly detailed, and I felt that the person writing the story had lived this experience. It’s not just a cowboy story from 1925 of ranch life. This is a lived experience, and I think because of that I felt a real trust for the story. I loved how deeply it explores masculinity and that it’s also about a hidden love.

Jane Campion

It’s a rich psychodrama with extraordinary roles for the central characters, has an incredibly cinematic landscape, and a chilling and surprising ending that really works.

Tanya Seghatchian, producer

Nothing’s a true Western anymore. Since WW2, everything has been an anti-Western, critiquing American expansionism rather than glorifying it.

But okay, whatever, is this an ‘anti-Western’ then?

Nope, not even that, exactly. It’s a domestic drama but looks at times like a Western because it’s set on an American ranch.

Domestic dramas set on American ranches are frequently mistaken for Westerns, especially if the author is a man.

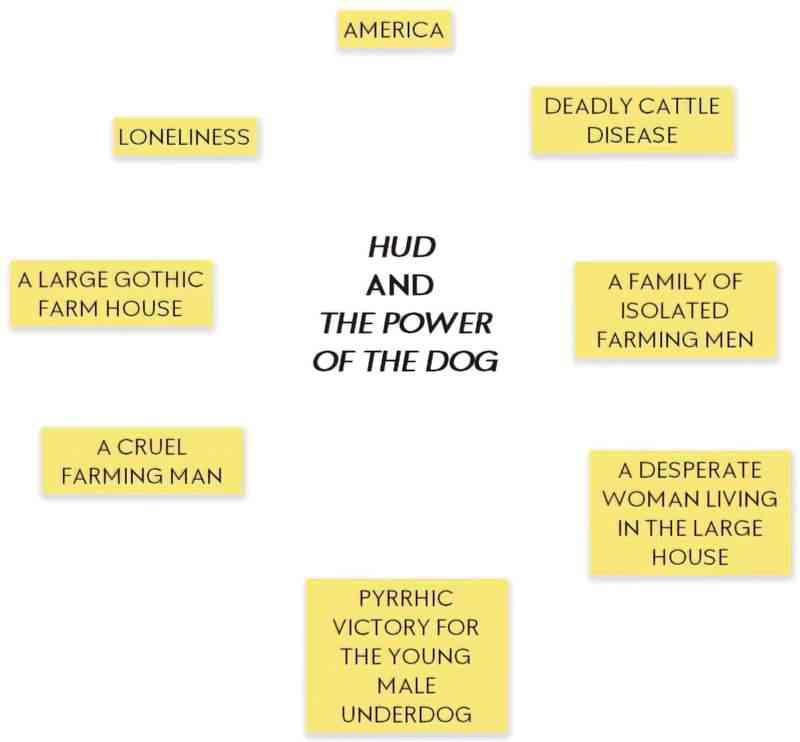

Another domestic drama written by a man, frequently mis-marketed as a Western is the film Hud (1963), based on Larry McMurtry’s first published novel. (If you’re not familiar with McMurtry, he died recently. He was best known for Lonesome Dove.)

So how is a Western different? There’s more to a Western than ‘setting’.

Now for the ways in which The Power of the Dog is somewhat like a Western.

The creators clearly expect audiences to come to this story with knowledge of Westerns. Back in the 1960s, when Thomas Savage’s novel was published, Westerns were very popular with American men. You just don’t find that many people who consume Westerns anymore; not in the way some contemporary readers — stereotypically women, but also many men, in private — consume romance stories — I’m talking several books per week. It’s really important to understand this. If certain modern viewers of Campion’s film adaptation are having a bit of trouble reading the symbolism, it’s because we have collectively lost certain knowledge around the (anti-)Western genre which was once so very familiar.

The Power of the Dog is better described a neo-Western: a subgenre of the Western that adopts the character archetypes, settings, and themes of classic Westerns, but transplants them to appeal to contemporary sensibilities.

Other examples of neo-Westerns:

- No Country For Old Men (Cormac McCarthy utilises the wilderness of a Western landscape for this crime thriller and psychological study of a sociopath and the sheriff who tries to catch him.)

- Brokeback Mountain (a story about a homophobic community and its specific impact on two gay men)

- Hell Or High Water (A story of American capitalism and how it does a number on the farmers who used to make an honest living off the land.)

The American wilderness settings of neo-Westerns cannot be divorced from the plots and themes. But we can’t call them traditional Westerns because they are concerned with issues other than American expansionism.

WHY IS THE POWER OF THE DOG DIVIDED INTO PARTS?

First, consider this film the screen equivalent of a series of interlinked lyrical short stories. When authors release narratives as a series of interlinked shorts, or parts, the point of view is often changing at each part.

So it is in The Power of the Dog. Each part has its own ‘main character’. Ultimately, this turns the story into one of community rather than about the triumph or downfall of a single character. The ‘community’, specifically, is the collection of people who all find themselves in this particular farm house at this particular time.

- At first we might think the story will follow George, but as soon as he is established as a good, wholesome character, there’s nothing much more to be said about him.

- Rose and her piano are next. The piano and Rose’s relationship to it must convey the contents of her entire life to us. This piano is doing a lot of heavy lifting.

- Next the story switches to Peter. Is the story about him?

- Rose and the gloves.

- Now to Phil and Peter together. Wait, is the story a twisted romance between these two?

- Nope. Back to Peter.

When stories divide into parts they’re frequently also creating ‘gaps’ in the pacing. When talking about story pacing, narratologists sometimes divide narration into the categories (from slowest to fastest):

- pause

- dilation

- scene

- summary

- gap

By breaking a story into clear, differentiated parts, storytellers avoid discombobulating the audience with the gaps, and there are plenty of gaps in this story, where there wouldn’t be in many similar stories. For example, we don’t see the wedding. We don’t see the funeral. These are the ‘designated’ important days of our lives, but when this story skips them, the statement is this: The days we designate as important are no such thing. Lives turn on a dime when we least expect massive change.

There’s another really important reason for the parts, and the switch in viewpoint: The audience has time to forget a few things, but only just enough for the ending to be a surprise. For instance, we almost forget that the film opened with Peter carefully making replica flowers, and that this is indicative of an interest in anatomy, not a femme coded activity. We almost forget it wasn’t Peter who became upset after the bullying incident at the inn; it was his mother.

Now I’m curious! Men only, what’s your favorite flower? (A Twitter thread)

WHAT IS THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE TITLE?

THE BIBLICAL MEANING

Even if audiences don’t know this coming in, we see Peter look something up in a Bible. Not surprisingly, Thomas Savage isn’t the only one to utilise ‘the power of the dog’ in fiction. It’s an aesthetically pleasing line.

Deliver my soul from the sword; my darling from the power of the dog.

Psalm 22:20

What does it mean? The film will explain it a little, when it finally comes up, but an article at CinemaHolic makes a good job: What Is the Meaning of The Power of the Dog Title? Does it Refer to a Bible Verse?

Old Testament writing often uses a mirror image pattern known as chiasm. David earlier compared his enemies’ attacks to those of bulls (Psalm 22:12), lions (Psalm 22:13), and dogs (Psalm 22:16). In verses 20 and 21, he will complete the mirror-image by mentioning those same animals in the opposite order: dogs, lions, oxen.

Bible.ref

THE LITERARY SIGNIFICANCE

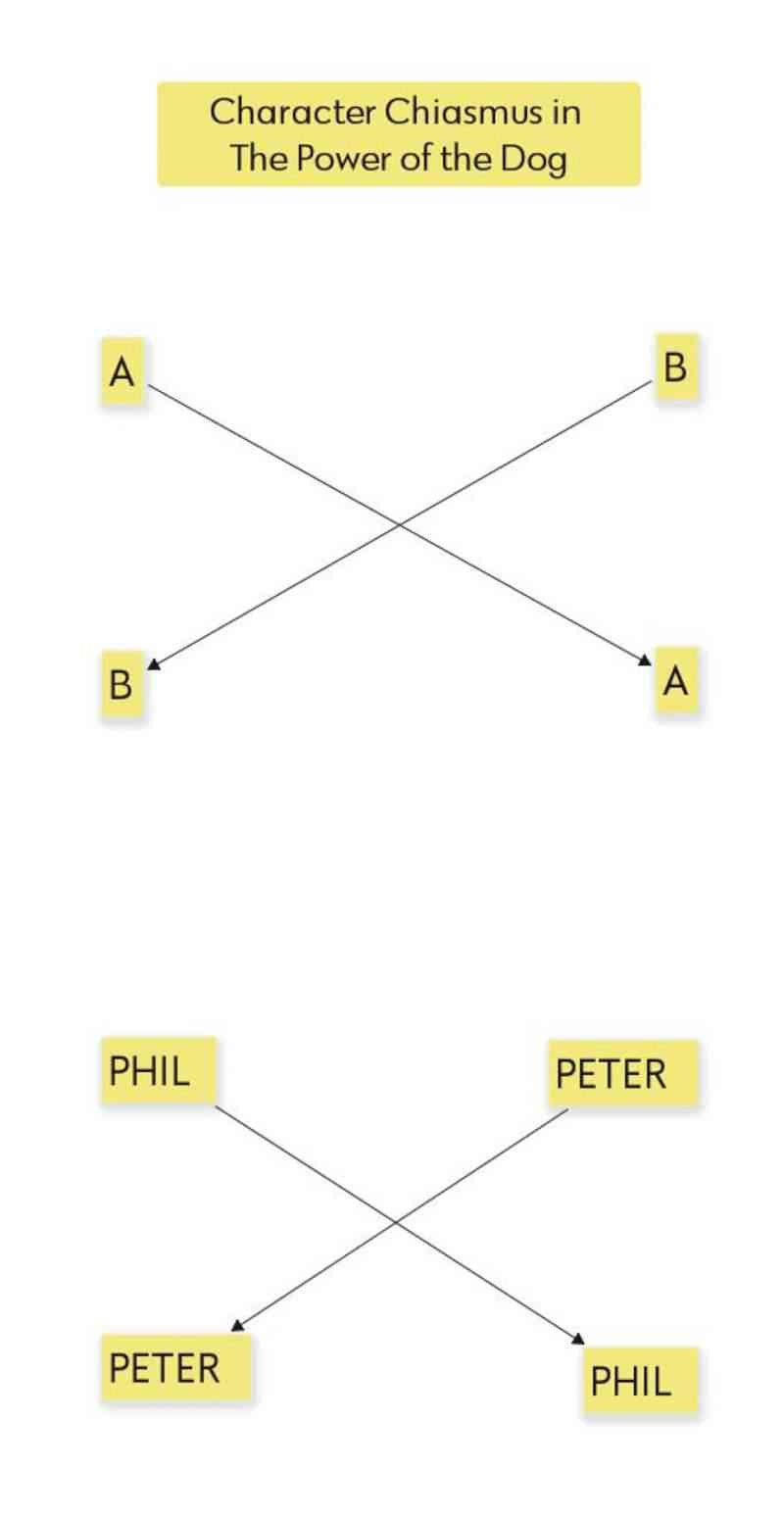

In rhetoric, chiasmus (or chiasm) describes a reversal of crossing of grammatical structures in successive phrases or clauses.

To take an example of chiasmus from a different work (film adaptations sharing a link via the Australian actor who plays Peter):

You forget what you want to remember and you remember what you want to forget.

The Road, Cormac McCarthy.

That’s a good example of chiasmus which expresses irony.

We might also take the grammatical structure of chiasmus and apply it to a story’s character web, in which case:

Character chiasmus might describe a opponent relationship in which character A inflicts something upon character B. In turn, character B inflicts something upon character A. They both ‘cross’ each other, with a power reversal that happens somewhere near the middle of the story.

THE DOG WHICH BINDS PETER AND PHIL TOGETHER

At a certain time of day, shadows cast onto the foothills reveal the shape of a dog. As a test, Phil asks a group of workers if they can see an animal. None of them can. Later, Phil asks Peter if he can see it. Peter picks it out right away.

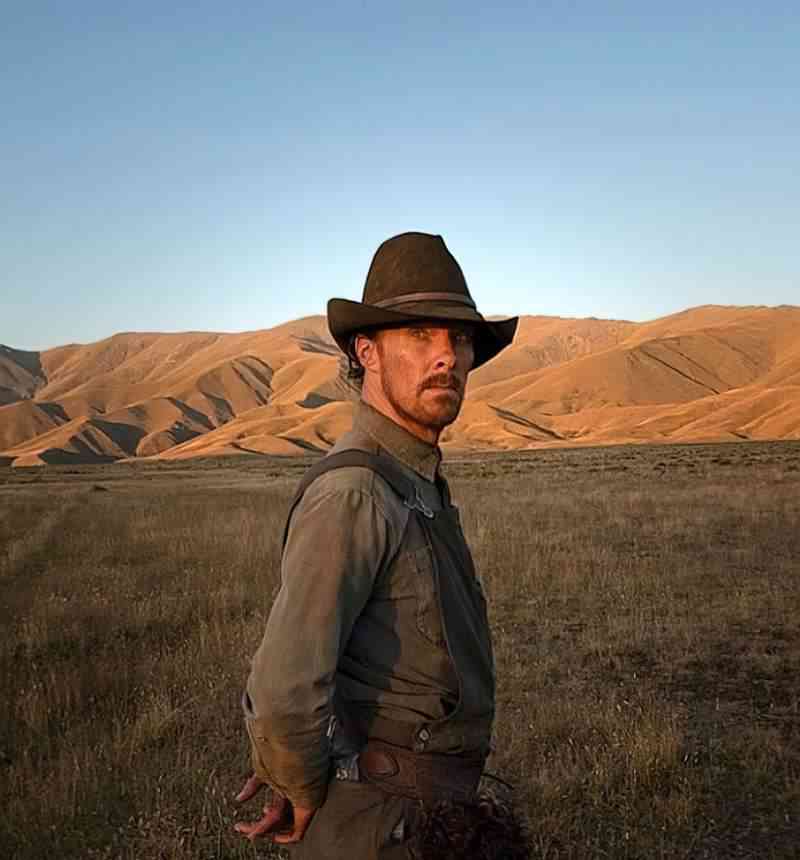

I’m guessing this is it:

Phil is impressed by this. These two are the only ones in the story who can see the same thing.

It’s not really about the dog, though. Their ability to see something which no one else can sets them apart. This goes to the very heart of what it means to be queer: A different way of seeing the world.

WHY DOES MONTANA LOOK SO BEAUTIFUL?

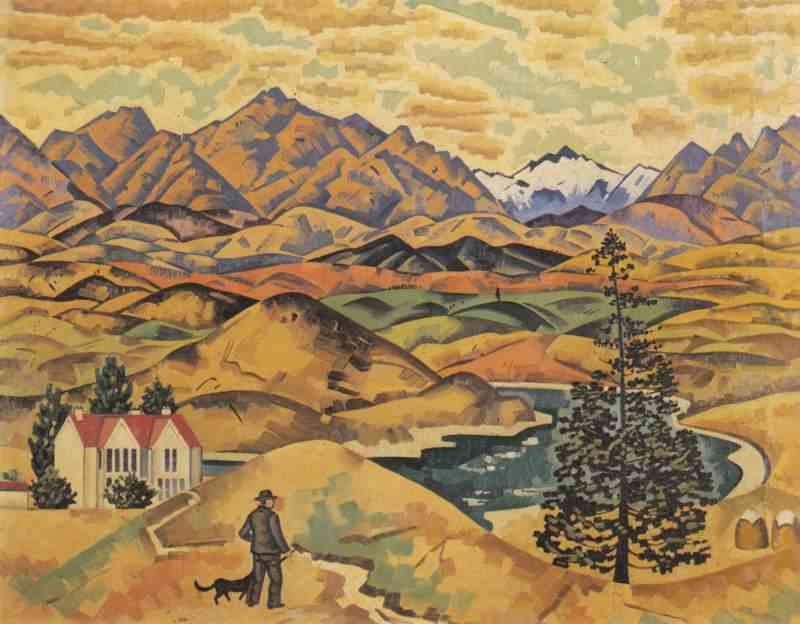

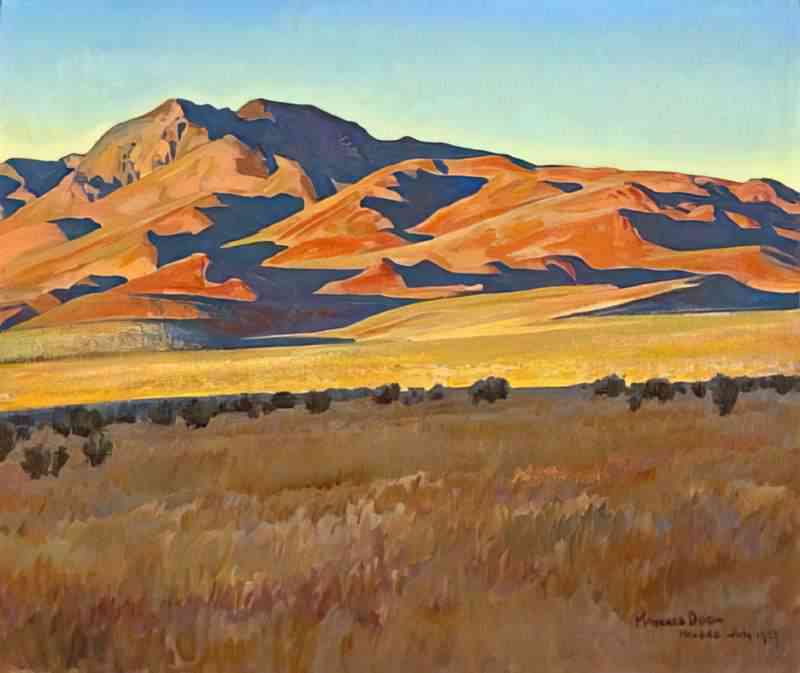

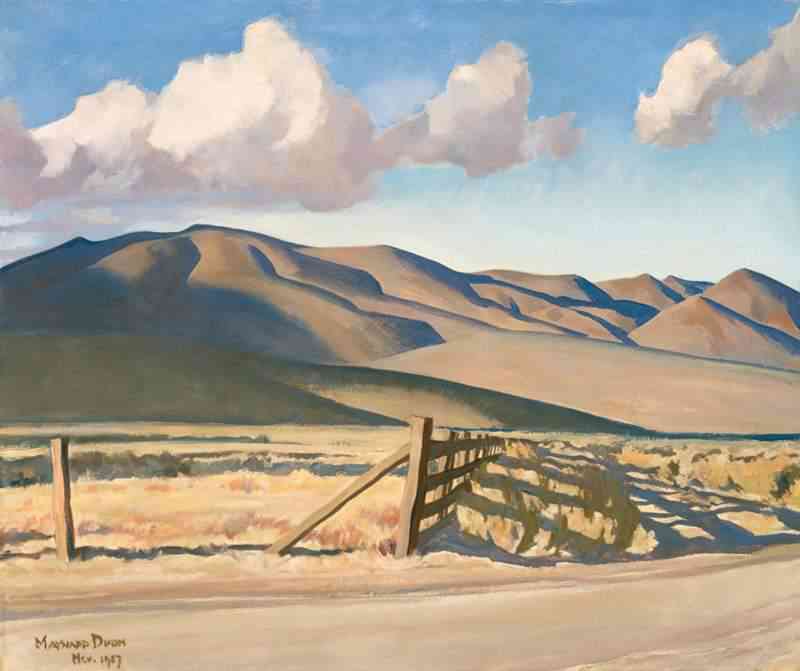

This film is set in Montana, America, but filmed in Otago, near the bottom of New Zealand. Thomas Savage was writing a story about the real life farm of his own maternal grandparents. Jane Campion went to see it so she could replicate the setting authentically.

Although the outdoor scenes were filmed in Central Otago, much of it was filmed in a studio up in Auckland. While covid raged almost everywhere else, New Zealand, with its zero covid policy, was a safe place to film at the time.

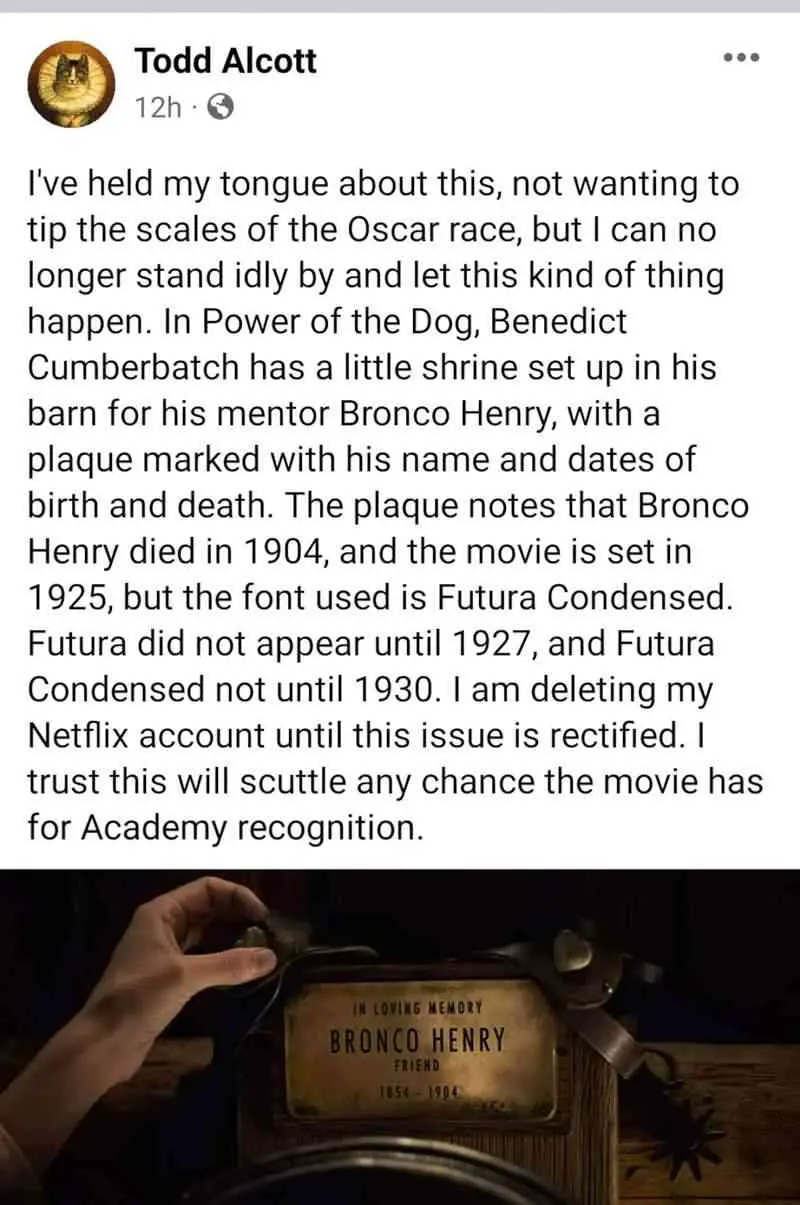

WHY WON’T PHIL SHUT UP ABOUT BRONCO HENRY?

Only on second viewing did I realise just how much Phil talks about this guy. It starts on the prairie, with Phil asking George to recall the significance of the day. It’s 25 years since the two of them first started working together, initiated and trained by the great rider, Bronco Henry. This Bronco Henry guy clearly means nothing at all to George and everything in the world to Phil.

Similar to Gus Fring in Breaking Bad, the death of his gay lover is subtly conveyed as the reason for Phil’s cruelty. He’s a broken man. Not only did he lose the love of his life, he wasn’t allowed to openly mourn him as heterosexual people do.

To keep on living and remembering him, Phil revisits the river. We can deduce Phil and Bronco Henry bathed there together numerous times, because we see there’s a tradition of the other men doing just that. Phil doesn’t feel sufficiently comfortable to join them, though he does look on from a distance. Phil keeps a handkerchief stuffed down the front of his pants. He pulls it out and enjoys it in a sensory way. A close up shot reveals that the handkerchief is embroidered BH, which is actually kind of comedic because you would expect someone’s proper name to be embroidered on something like that. ‘Bronco’ is the guy’s actual name.

Bronco is an American term for a wild or partly tamed horse. Undoubtedly, this Bronco Henry was somewhat wild, or had that reputation. Phil carries on the tradition of living as close to the land as he can, eschewing his university education and his wealth. He could live in comfort but chooses not to.

WHAT’S THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE ROPE?

Like other symbols in this story, the rope has multivalent symbolism.

In the best sense, the rope is a symbol of unity. Phil invites Peter to make a rope with him. This literally brings them together, as it requires more than one person to work with the hides and cut the strips and braid.

“You ever do any plaiting or braiding yourself Pete?” Phil asks. What do we mostly associate with braiding? Girls’ hair. I do wonder what Phil is really asking. “No, sir I never did,” Peter replies.

Cowboy ropes are used to lasso, to constrict another’s freedom, to bring cattle under the control of man.

At the worst end of the spectrum, the rope can also be a noose. Another neo-Western, No Country For Old Men, makes subtle use of similar rope symbolism.

HOW DOES PHIL DIE?

Peter made sure he became infected with anthrax.

“We got off on the wrong foot,” Phil says, in a non-apology suggesting they’re both equally bad. Peter is the visitor on this ranch and must go along with Phil’s plan to teach him how to be a manly man. But he has a secret plan of his own. The audience is kept in inferior position as Peter carries out this plan:

- Find a dead cow which has died of anthrax

- Being very careful (wearing gloves), collect its hide.

- Wait for your moment. Phil never wears gloves. He’s far too tough.

It’s possible Peter had no such plan and was a complete opportunist. The plan may not have worked had Phil not cut his hand as they tried to find the rabbit in the woodpile.

Rose gives away the hides that Phil planned to use to make rope. “I have a hide,” Peter tells him, knowing full well it’s infected.

And by the time Peter is ‘feeding’ Phil that last cigarette (his ‘last meal’) in the barn, Peter has decided to let him risk anthrax. He won’t be stepping in.

Note that the cigarette scene has more than one storytelling function. It is a tensely intimate scene between two men who may or may not be similar. The scene also functions to show us how Peter is not touching the carcass himself. He’s making himself busy with the cigarettes, letting Phil do all of the anthrax work.

WHAT ARE WE TO MAKE OF PETER?

The Power of the Dog slowly reveals itself to be not a love story but more like something out of the twisted mind of Shirley Jackson.

Think Merricat from We Have Always Lived In The Castle (1962). Peter is a Merricat archetype. Both are around 18-years-old, both are proto-Goths, both are into slow, undetectable forms of murder; poisoners, modern witches. (TV Tropes calls this trope Perfect Poison.) Whereas Merricat has an agoraphobic older sister, Peter has a different kind of shut-in for a mother.

I’ve … learned that a lot of scientists have mischief in their pasts, and their particular strain of mischief can be a good predictor of their future chosen field. Chemists, for instance, usually experience a period of childhood pyromania. Biologists might get a little too curious about what’s inside frogs. Physicists, somewhere along the way, drop objects from heights.

The Smallest Lights In The Universe by Sara Seager

IS PETER QUEER?

There’s no definitive on-the-page evidence that Peter is gay.

But isn’t he at least genderqueer? After all, when we first meet him, he’s engaging in the highly femme coded pastime of creating paper flowers. Yes, yes he is. But why is he so into flower? We are meant to code him as feminine ourselves; that’s deliberate. But the thoughtful viewer will eventually understand that Peter’s interest in the flowers belies his interest in anatomy (stamens, pollen, the shape of petals etc.). Peter’s perfect representations of flowers also belie an extraordinary patience and attention to detail. Both foreshadow his long-term plan to murder undetectably, from a distance, as if playing God.

But he plays with hula hoops, we might ask? In 1925, hula hooping was not a femme coded activity because it wasn’t any kind of activity.

Jane [Campion] has an instinct for finding hidden notes and knowing how to intensify sensuality. One of her real gifts is making invisible emotions visible. We pinpointed themes and emotional gaps to explore more deeply and Jane crafted scenes only partially described in the book in a visual language. Jane is a master at highlighting desire and making it come alive cinematically.

Tanya Seghatchian, producer

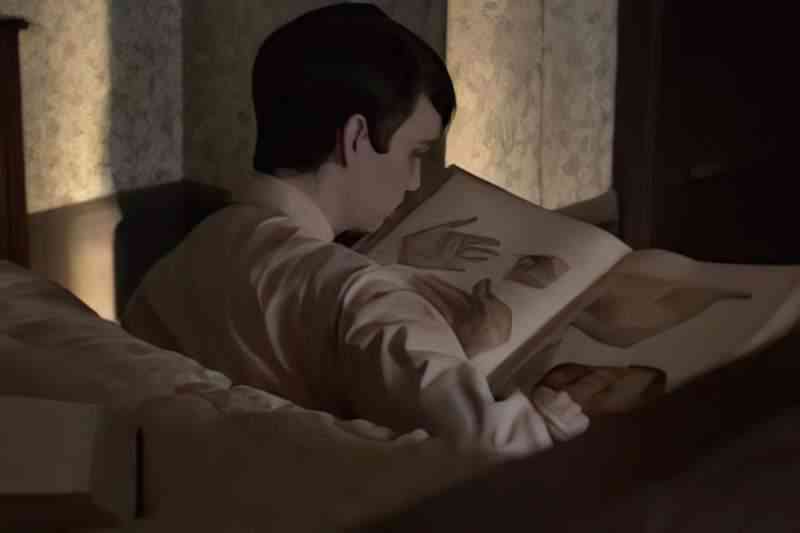

Peter later finds Phil’s magazines and flips through. Is he interested in the pictures themselves, or only in what they reveal about Phil? We don’t know. We don’t see Peter coming back to them, drawn in by their eroticism. Once was enough.

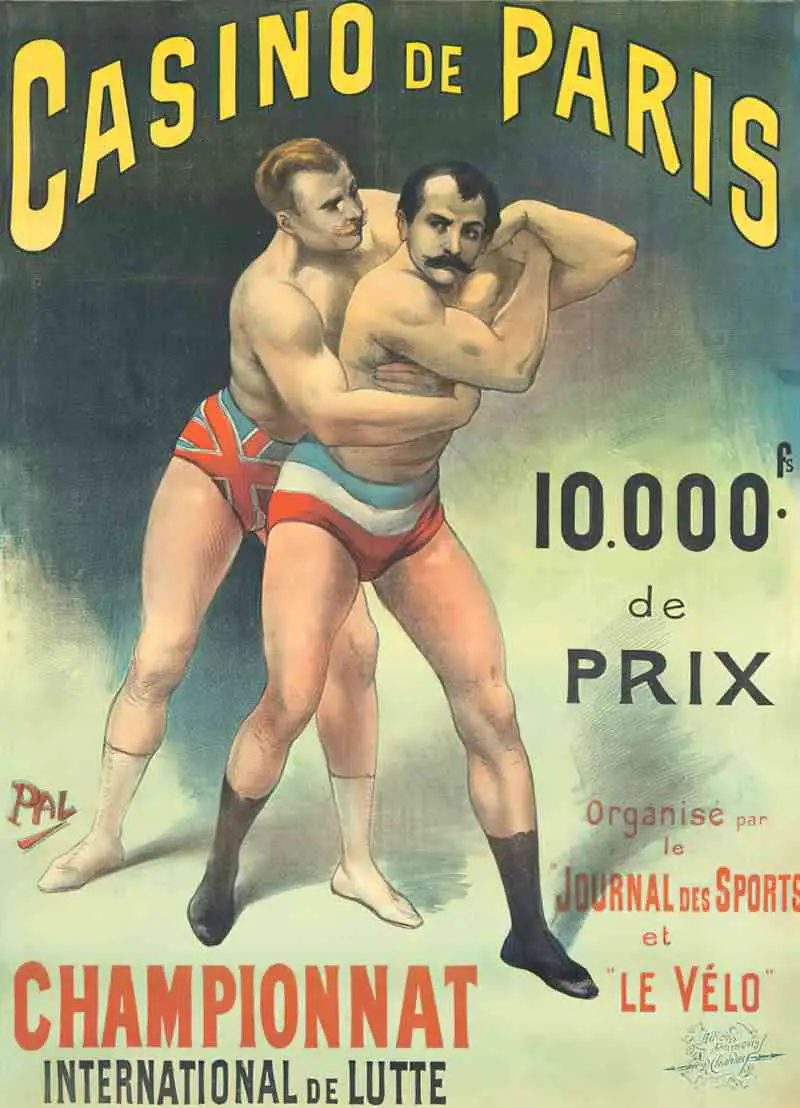

Art by Jean de Paléologue (1860-1942) Casino In Paris, ostensibly an illustration of wrestling from 1899 or perhaps, in fact, intimacy coded as violence which can, if we’re not careful, turn into actual violence.

The sexual orientation of Peter remains an enigma to us, which contributes to our sense of him in his godlike role. He could be gay, bi plus, asexual or even straight. We simply don’t know.

What about Peter’s unseen male friend? Peter mentions a male friend who he refuses to bring to the house because of ‘a certain person’. We deduce Peter doesn’t want to subject him to Phil’s homophobic bullying but it doesn’t follow that these young men have sexual or romantic interest in each other. They call each other pet names which, if anything, suggest an attraction to each other’s minds.

The notion that close best friends are gay until proven otherwise informs toxic forms of masculinity. In subcultures with this mindset, men are required to prove they are “real” men by proving they are not gay and not women. This film consistently invites viewers to fall into dangerous mental traps: In relation to Peter, the mental trap of underestimation.

We underestimate Peter’s capacity for cold and calculated decision making because he also likes to make paper flowers, which we, along with Phil, associate with femininity, and therefore with weakness.

IS PETER AUTISTIC?

When this book was written, Hans Asperger’s work wasn’t well-known, and if Thomas Savage was writing an autistic character in Pete, he can’t have done so consciously but must have been informed by various autistic people he’d met over the course of his life. (Autism has always existed. Only the label is new.) Of course Peter will never be on-the-page autistic.

So let’s talk about a 2021 audience, many of whom know enough about autism to see neurodivergence in fiction.

- Peter has a strong, enduring interest (biology). He immerses himself in biology at every opportunity. It grounds him. Biology is Peter’s special interest, or what people pejoratively call an “obsession” or a “fixation”.

- In the current version of the DSM, sensory processing disorder comes under the umbrella of autism (so a person with an autism diagnosis no longer needs the separate diagnosis of SPD). Peter is not the only character in this story with strong reactions to sensory stimuli. The way he flicks the comb is highly reminiscent of a cowboy cocking a gun in a Western movie, but for him it functions as a calming measure. Then there’s the hula hooping. Same thing. Like spinning in circles.

- As much as the comb flicking calms Peter, it irritates Rose, perhaps because she is constantly in the highly unpleasant cycle of intoxication and withdrawal, but also possibly because Rose is sensitive to sensory stimulation more generally herself. We see this with her reaction to the beautifully soft Native American gloves. Since autism is more than 80% heritable, if Peter is autistic, it’s highly likely Rose is (at least) broad autistic phenotype.

- Ten per cent of autistic people are gifted. It’s likely Peter is gifted in biology. He is certainly gifted in poisoning, and his hubris must come from somewhere.

- Cognitive empathy is a second language for autistic people, but by young adulthood, smart and/or gifted autistic people have learned cognitive empathy via keen observation. The common autistic ability to see patterns affords a broad and useful (almost omniscient) view of humanity. When you’re not bombarded with all sorts of information about either kind of empathy you are afforded a clear eye view of someone’s patterns of behaviour. Both Phil and Peter have this ability, though Phil uses it to manipulate and maintain hierarchy with him at the top. Making use of his carefully studied cognitive empathy, an observant character such as Peter may take a studied look at the household his mother has married into, calculate that if Phil were to disappear there would be a net gain in collective happiness, then act accordingly.

- Note that cognitive empathy and affective empathy are two separate things. Autistic people have no problem with affective empathy, and many have so much natural affective empathy that it overwhelms. Sometimes it overwhelms to the point where it must be somewhat ‘turned off’ in order to function. I’ve no doubt some viewers will code Peter as a sociopath, the empathetic inverse of autism: sociopaths are high in cognitive empathy, but for sociopaths, it’s the affective empathy which doesn’t come so naturally.

- Autistic men are frequently mistaken for gay men. This makes sense: Any masculo-coded individual who does not conform to the constrictive rules of manliness attracts this label whether it fits or not. ‘Gay’ may also fit; there’s a broader range of gender expression and orientation within the autistic community, because there’s a broader range of every metric of humanity within the autistic community. But there’s a reason why autistic people frequently present as queer even when they are cishet: Gender and sexuality rules exist to prop up a nonsensical gender hierarchy — that is literally the only function of those rules. Autistic people have a low tolerance for social hierarchies in the first place. Moreover, gender rules are a second language so must be learned, and anything consciously learned is subject to critique. In general, autistic people have a lower tolerance for rules which make no sense. Ergo, why conform to gender and sexuality rules when they’re nonsensical?

- Why respect someone at the top of the social hierarchy when they don’t deserve to be there? Peter does not respect Phil’s position as the man at the top of the pecking order. Phil goes to great lengths to keep himself top dog; he is a constant bully. He bullies his own brother (by calling him ‘Fatso’, by dismissing his new wife, by preemptively poisoning the relationship between Rose and his mother etc). The other men, including George, don’t challenge Phil’s position at the top of that hierarchy. For them it’s not worth it. It may even feel natural to them because they don’t give conscious thought to how human hierarchies are established and maintained. But Peter doesn’t feel the hierarchy. Since Peter doesn’t see Phil as the top dog, this actually affords him immunity to Phil’s attempts at bullying. His opinion means nothing.

- Phil seems to sense this about Peter. But, to his detriment, he can’t fully figure him out. The moment things change: After Phil’s constant encouragement, the workmen jeer as Peter walks the gauntlet towards some birds in a tree which he’d like to observe. Phil respects how well Peter carries himself. He underestimates Peter, thinking he’s showing bravado but is secretly in turmoil. My interpretation: Peter literally doesn’t give a shit about what those guys think of him. He is going to be a professional man. He is in an entirely separate class from these fools and their rubbish pecking order. (I’m tempted to compare the men to chickens, but they’re more like a pack of wild dogs.) If Peter doesn’t consider himself one of the dogs, they can’t get to him.

- Following on from all that, my best guess about Peter’s gender and sexuality: If Peter’s not straight, he is neuroqueer.

- If the author’s biography informs our reading, it’s worth noting that Thomas Savage was himself gay, though because of the era in which he grew up, he did marry a woman and have children. Other aspects of this story are autobiographical (the ‘demonic step-uncle’ — Campions’ words) so we might deduce this aspect of Peter is autobiographical as well.

In a traditional Western, the badge is heavily symbolic. There’s no actual badge in this one, and no sheriff, but Peter places a metaphorical badge upon himself as lawmaker and protector of the family. In his own eyes, he is enforcing what’s right and good. Already ostracised, he is unlike the Western hero. Even from the start, he has nothing to lose. This makes him even more powerful than your typical Western hero, who often ends a story with a pyrrhic victory, having saved a community but ruined his own life.

AT PHIL’S FUNERAL, WHY DOES THE MOTHER GIVE ROSE HER JEWELS?

Throughout the story, we’ve seen nothing of the relationship between Rose and Mrs Burbank. The old woman lives somewhere else now. There’s nothing for her on the farm during retirement; she lives an upper-class life in town. Phil has done his best to sour the relationship between these two women by trash-talking Rose in a letter to the men’s mother, pre-empting the announcement of an engagement. When the mother visits for dinner, we see no warmth between these two women at all.

Traditionally, jewellery is handed down from matriarch to the eldest woman of the younger generation. When Rose receives this inheritance at her brother-in-law’s funeral, I deduce the old woman never stopped waiting for Phil to marry a woman. The sadness of this is that Phil was never truly known, not even by his own mother. The only person who truly got to know him was Bronco Henry (perhaps), and then Peter.

It is only once Phil is dead that the mother gives up on the dream of him marrying and producing a new generation of farmers. Now it’s up to Rose to hold the mantle of Burbank matriarchy. The old woman confers power when she hands over the jewels.

With Phil gone, and with her mother-in-law’s acceptance, the audience can hold optimism for Rose. Perhaps, once she detoxes, things look very good for her from now on.

WHAT’S THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE GLOVES?

Jane Campion makes sure we notice-but-don’t-notice Peter’s gloves. This is a very difficult balance, adroitly executed.

The gloves are integral to the murder plot. When Peter makes the decision to infect his mean uncle with anthrax, Peter’s gloves are the one thing protecting him from death himself.

Were farmers making regular use of rubber gloves in 1925? I very much doubt it. The very first rubber gloves were made for surgeons in 1890 because by now it was clear that dirty hands were a menace. Surgeons were using carbolic acid and mercuric chloride as disinfectant, which caused contact dermatitis. So they started wearing rubber gloves.

But latex disposable gloves weren’t made for general use until 1964, by the Ansell rubber company. Remember this book was published in 1967? When Thomas Savage wrote this book, disposable rubber gloves for use around the house and farm were a new thing, and perhaps because of their newness, were likely on the author’s mind.

Farmers, without a doubt, were using other forms of hand protection, leather gloves to avoid chafing and whatnot, but to avoid deadly disease? Not so much. That sort of thinking was in the realm of surgeons and biologists, a realm Peter is stepping into himself.

Peter must have got his own rubber gloves from his academic institution. He probably brought them home for summer so he could continue his work on small animals, dissecting them, learning from them. He already knew that Phil was an asshole bully, but his plan probably hatched more slowly. Peter’s crime is opportunistic; he doesn’t go out of his way to make sure Phil cuts himself while trying to catch that rabbit, but he sure makes the most of the open wound, which Phil shrugs off as a ‘splinter’.

Did you notice all the shots of Peter putting on gloves? Again, this is something more obvious on second viewing. He carefully puts on rubber gloves before setting to work on that diseased dead cow. Note, too, that he puts them on again after Phil has died, before touching that coil of rope which he carefully slides under the bed, just in case it doesn’t work out with George, perhaps.

Soft hands were a sign that a women came from a prosperous or upper class family and gloves were the number one way to keep the hands soft and protected while out horse riding.

Long gloves allowed women to hide the skin on their arms if they had a sort sleeve on their top which enabled them to cover up and maintain their modesty.

For those women that did have coarse hands from manual work, gloves were a way to hide their hands especially when at church or other social gatherings, effectively allowing them to hide their station in life.

Fashion In Time, History of Gloves

Peter’s rubber gloves are not the only significant gloves in the story. The scene with Rose and the Native American gloves draws our attention to gloves-but-not-Peter’s-gloves. The power of suggestion.

DOES THE STORY POINT TO A HAPPY ENDING FOR GEORGE AND ROSE?

WHAT’S WITH PHIL AND HIS REFUSAL TO TAKE A PROPER BATH?

For plot reasons it’s important that he has a certain relationship to cleanliness, otherwise he may not have been infected with anthrax. But there’s way more to it than that.

As Jane Ward explains below, queer culture works differently from straight culture regarding abjection and ‘disgust’. To remain dirty is to embrace one’s full self as it is, and Phil is making a statement against straight culture when he refuses to wash before coming to (straight) table with (straight) guests:

A basic premise of straight culture is the idea that gendered bodies, especially women’s bodies, require purification and modification to be desirable — shaving, perfuming, toning, refining, shrinking, enlarging, and antiaging. But in queer spaces, it is often precisely the hairy, sweaty, dirty, smelly, or unkempt gendered body that is most beloved. I recall the first time I entered a gay men’s sex shop, in the 1990s in the Castro district of San Francisco, and encountered a barrel full of lightly stained and dingy-looking “used jock straps” for sale. It was my introduction to the fact that there were people in the world who desired men’s bodies so much that they wanted deep, intimate, and seemingly unconditional contact with them–even and especially the parts of men’s bodies that straight women seemed to want to avoid.

Most straight women I knew, no doubt due to their socialization as girls and women, appreciated men’s bodies for their sexual functionality but not as a site of objectification that they were excited to dive into and explore–to smell, taste, or penetrate. Similarly, I have been to dozens of dyke strip shows, burlesque shows, drag-king shows, and sex shows in which women’s armpit hair and leg hair and facial hair or their body fat or their genderqueer bodies have been precisely the objects of the audience’s collective lust. Fat bodies and hairy bodies are also staples of queer dyke porn, not relegated to a fetish category.

In other words, queer desire is marked by a lustful appreciation for even those parts of men’s and women’s bodies that have been degraded by straight culture. Like a food adventurer who delights in those parts of the animal or plant deemed undesirable by the narrowing of mainstream tastes, queer people’s desire for the full animal has been less constrained. Recognizing this suggests that gay men may have a deeper or more comprehensive appreciation for men’s bodies than do straight women, just as lesbians’ lust for women is arguably more expansive and forgiving than straight men’s. But most importantly, because queer circuits of desire do not rely on the erotic encounter of “opposites” embedded in a boarder culture of gendered acrimony and alienation, queer lust need not reconcile a conflict between wanting to fuck and generally disliking one’s fuckable population.

Jane Ward, The Tragedy of Heterosexuality

David Bowie’s song Cactus conveys a similar eroticism. The narrator requests someone get their dress dirty and then send it to him. (We shouldn’t assume the wearer of the dress is a woman.)

RELATED

Screenplay of The Power of the Dog. Although it says ‘final draft’, final drafts don’t match the final product. It’s interesting to see how the beginning changed.

Turning New Zealand Into 1925 Montana for The Power of the Dog at Architectural Digest.

Jane Campion visited Montana and I trust she saw enough similarities between Otago and Montana to create an authentic experience even for Montana folk. I’ll leave you with a painting of the Central Otago landscape by New Zealand painter Rita Angus. This one dates from 1940. (Could it pass for Montana also?)