**UPDATE LATE 2024**

After Alice Munro died, we learned about the real ‘open secrets’ (not so open to those of us not in the loop) which dominated the author’s life. We must now find a way to live with the reality that Munro’s work reads very differently after knowing certain decisions she made when faced with a moral dilemma.

For more information:

My stepfather sexually abused me when I was a child. My mother, Alice Munro, chose to stay with him from the Toronto Star

Before Alice Munro’s husband sexually abused his stepdaughter, he targeted another 9-year-old girl. ‘It was a textbook case of grooming’ from the Toronto Star

So, now what?

Various authors on CBC talk about what to do with the work of Alice Munro

And here is a brilliant, nuanced article by author Brandon Taylor at his Substack: what i’m doing about alice munro: why i hate art monster discourse

“The Office” is a short story by Canadian author Alice Munro, first published in Dance of the Happy Shades (1968).

Unless you’re a woman, or a femme presenting person, it may be lost on you how very relatable this story is. In “The Office”, a middle-class woman rents an office away from the home where she can spend evenings and weekend afternoons honing her craft. She’s a writer. She isn’t published yet, but she feels she needs an office anyway — perhaps taking Virginia Woolf’s 1929 advice that a writer needs a room of one’s own.

The solution to my life occurred to me one evening while I was ironing a shirt. It was simple but audacious. I went into the living room where my husband was watching television and I said, ‘I think I ought to have an office’.

It sounded fantastic, even to me. What do I want an office for? I have a house; it is pleasant and roomy and has a view of the sea; it provides appropriate places for eating and sleeping, and having baths and conversations with one’s friends. Also I have a garden; there is no lack of space.

“The Office by Alice Munro”

Various woman writers continue to broach the topic of sexism in writing, the failure to be taken seriously, the imposition of others on their time, space and into their very minds, not to mention the never-ending day-to-day drudgery of keeping house and caring for family which, until recently, was a dawn to dusk job. Technology may have alleviated the dawn-to-dusk monotony that is housewife-ing, but for many women, those hours are usurped by paid work outside the home.

To take just this month’s viral example, Maggie Smith got a poem published in 2016 which made her a bit famous. This proved challenging for her husband. (They subsequently divorced.) Regarding that time in her marriage, she has now published this:

Even after my poem went viral, I was still hidden, cleverly disguised as one of the least visible creatures on earth: a middle-aged mother.

[…]

Did my children see their father’s job as more “real” than mine because it happened outside the home, and because despite my work, I was the primary caregiver? I felt that he treated my (writing) work like an interruption of my (domestic) work, and did they see that, too?

My Marriage Was Never the Same After That: In 2016, I wrote a poem that went viral. My home life got complicated by Maggie Smith

Writing of The Depression years, Australian author Carmel Bird characterises the life of a 1930s woman artist like this:

With her large family and a small farm to manage, it is a miracle Rita ever put brush to canvas. But this is something I have discovered about my women painters: they kept their sanity by snatching moments of creative passion from the hours of duty and family responsibility.

“The Legacy of Rita Marquand” by Carmel Bird, a short story in The Best Australian Stories 2006 (also available at The Griffith Review behind a paywall).

“The Legacy of Rita Marquand” by Carmel Bird, a short story in The Best Australian Stories 2006 (also available at The Griffith Review behind a paywall).

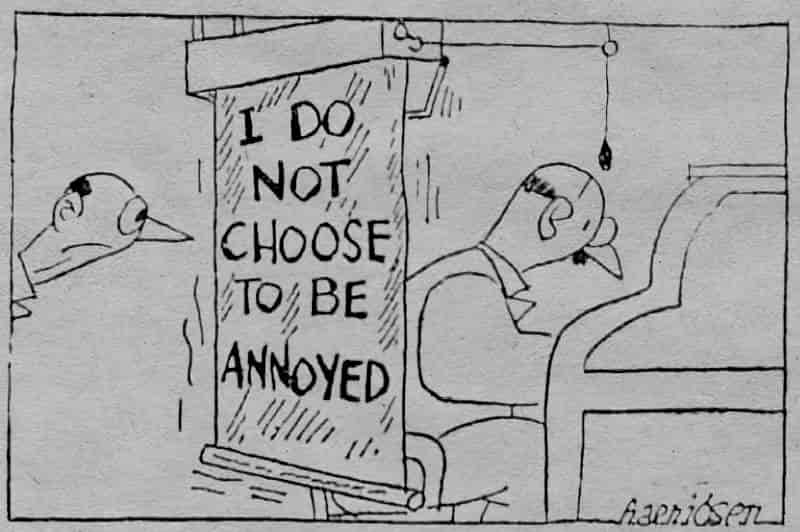

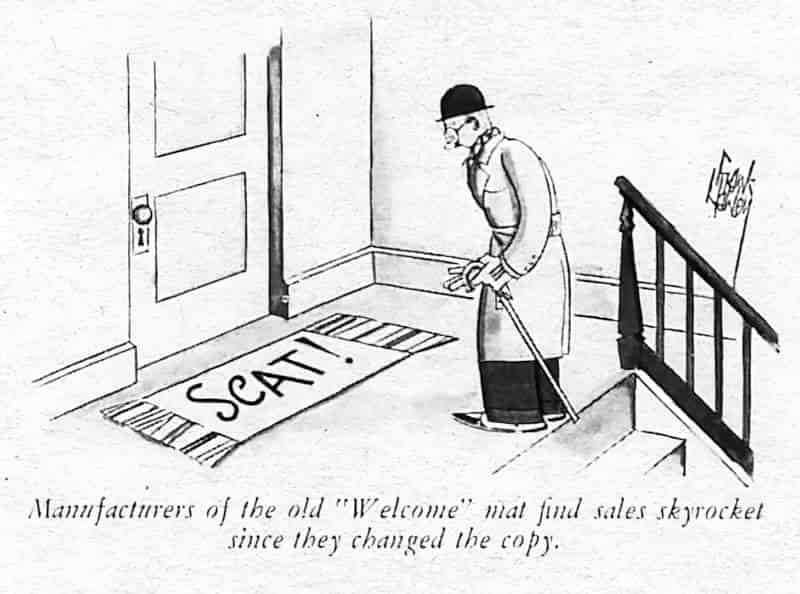

Of course, men understand fully how irritating it is, to be constantly interrupted while concentrating on a task. At least, men who work in open plan offices will know it. There’s a cult 1999 movie which exemplifies such conflict. (See my analysis of Office Space from a 2023 perspective).

FOR DISCUSSION

- In the narrator and the landlord’s wife (the landlady), Alice Munro has created two different (arche)types of women. How would you characterise the main difference between these two women?

- What did women’s rights look like in mid-20th century Western countries? Which rights had been won, which were yet to be achieved?

- Why do you think the landlord was so interested in his new tenant? What forces (both internal and cultural) drive him to encroach on someone else’s space?

- What is the story reason for the small potted plant?

- What red flags does the landlord give off? Is the narrator quick to see them?

- Alice Munro draws our attention to the conflation of house and woman. Can you think of stories from any genre which turn a woman into a house (either literally or metaphorically)? In these examples, where does sympathy lie? With the woman-as-house, or with another character?

- Is there anything you think the narrator could have done differently to improve this woman’s situation in her rented office?

- Can you think of other stories — or real life examples — in which a woman artist must fight for the space to create? How does she go about this? Does she succeed, fail, or fall somewhere in between?

“THE OFFICE” IN A NUTSHELL

A middle-class woman with a husband and children realises that, to be a writer, she needs her own office. So she rents a room from a couple in the town nearby. She will use this room during evenings and weekend afternoons.

The catch: The landlord of this room is an interfering nuisance who won’t leave her in peace. She left her household precisely for the headspace, but here’s this older man, filling it up under the guise of being a Nice Guy (TM).

One days he arrives at her office outside her usual routine and finds him reading her work. She is so angry she hardly knows what to do, but all she can do is lock him out of her room while she is in it.

Landlord gets the pip and things turn sour. He accuses her of lipstick graffiti in the adjoining toilet, which is never locked. The writer had nothing to do with it.

Now she has the landlord offside, she realises she cannot continue renting this office. Her time here is over. She hands her key to his wife.

ANALYSIS OF “THE OFFICE” BY ALICE MUNRO

INTRUSIVE LANDLORDS IN FICTION

Bad strangers who enter your house are an evergreen plot. A simple inversion: You’re the stranger, and the house you enter is bad.

Landlords and landladies who know too much about your life, inserting themselves where they shouldn’t, are a great subject for all kinds of stories, from horror to comedy. For a horror example, see “A Case of Eavesdropping” by Algernon Blackwood (1900). Roald Dahl wrote a femme fatale landlady in his short story “The Landlady” (which is only moderately successful as a story).

A wonderfully written comedic example can be found in the opening chapter to Notes From A Small Island by Bill Bryson, and the wonderfully named Mrs Smegma who runs a boarding house in Dover:

Over the next two days, Mrs Smegma persecuted me mercilessly, while the others, I suspected, scouted evidence for her. She reproached me for not turning the light off in my room when I went out, for not putting the lid down in the toilet when I’d finished, for taking the colonel’s hot water — I’d no idea he had his own until he started rattling the doorknob and making aggrieved noises in the corridor — for ordering the full English breakfast two days running and then leaving the fried tomato both times. ‘I see you’ve left the fried tomato again,’ she said on the second occasion. I didn’t know quite what to say to this as it was incontestably true, so I simply furrowed my brow and joined her in staring at the offending item. I had actually been wondering for two days what it was. ‘May I request,’ she said in a voice heavy with pain and years of irritation, ‘that in future if you don’t require a fried tomato with your breakfast that you would be good enough to tell me.’

Abashed, I watched her go. ‘I thought it was a blood clot!’ I wanted to yell after her, but of course I said nothing and merely skulked from the room to the triumphant beams of my fellow residents.

Notes from a Small Island by Bill Bryson (2015)

WOMAN AS HOUSE

A house is all right for a man to work in. He brings his work into the house, a place is cleared for it; the house rearranges itself as best it can around him. Everybody recognizes that his work EXISTS. He is not expected to answer the telephone, to find things that are lost, to see why the children are crying, or feed the cat. He can shut the door. Imagine (I said) a mother shutting her door, and the children knowing she is behind it; why, the very thought of it is outrageous to them. A woman who sits staring into space, into a country that is not her husband’s or her children’s is likewise known to be an offence against nature. So a house is not the same for a woman. She is not someone who walks into the house, to make use of it, and will walk out again. She IS the house; there is no separation possible.

“The Office” by Alice Munro

Alice Munro beautifully exemplifies how, in the West, the concept of ‘woman’ is historically intertwined with ‘house’. Arguably, this conflation was especially rife in the post- world war years, when the patriarchy conspired to send women back into the home, freeing up paid work for deserved returned servicemen, with the express goal of repopulating. Good Women were required to bear, birth and raise as many (white, Christian) babies as possible. (This turns out to be about five per woman, and almost all of the babies past infancy lived due to improved health care, which meant the work of a mother had never been so intense.)

But the trend of turning houses into ladies and ladies into houses had already been set in motion during the 19th century.

When lace became affordable, even the soft furnishings of a house matched women’s clothing:

[By 1900] colors, fabrics and textures were lighter… Whites and pastels largely replaced browns, blacks, deep burgundies, greens, and blues in women’s dress, and the materials were often much airier and more porous. Lace (now produced relatively inexpensively on factory machines) was used abundantly. It was made into bodices (the “Edwardian blouse” was often a rather frothy affair) or sometimes whole dresses, and it was used for trim on garments and accessories. It was also important for the first time as a fabric for undergarments. Lace also found its way into the interior, and significantly, it was particularly popular as a window treatment.

Lace curtains were multivalent symbols. Visually, they offered a sense of translucency and a play of light that was not unlike what the impressionists were experimenting with. They also stood for or reflected the greater permeability that existed between “the outside world” and the home at the turn of the century; just as women were following Frances Willard’s precept of “making the whole world homelike,” they were concomitantly bringing the outside in.

Some of this was conceptual, but some was literal, for they brought in an increasing amount of plant life, sunshine, and air. Lace curtains also signalled to the passer-by the strength of the feminine presence in the home, demonstrating the woman’s housekeeping skills and social aspirations and indicating her artistic refinement. Even beyond this, the lace also resonated as a particularly intimate fabric, as it now carried associations with lingerie. Because these were personal garments that were most closely in touch with the woman’s body, it is also reasonable to assert that hanging lace curtains in the window signalled a subtle but symbolically important identification between the home and body.

Beverly Gordon, Woman’s Domestic Body: The Conceptual Conflation of Women and Interiors in the Industrial Age, 1996

When the landlord of Alice Munro’s “The Office” insists what ‘women’ are like, couched in language around what women like, as a single blob of a category, he is not only generalising and stereotyping by gender. He is influenced by a very strong cultural force, in which woman is house, house is woman. Even when a woman leaves the domestic sphere, she must create domesticity afresh, wherever she lands. It is inconceivable to this man that a woman might be happy (happier) in a Spartan room, where she is less distracted and better able to sink into the wealth riches of her own mind.

The symbol of the lace curtain (and its connection to underwear) is especially apt because it exemplifies how, conceptually, the dominant culture can’t seem to get past conflating women with sexuality. This is exactly what’s happening in Alice Munro’s story. To be seen as a sexual object by cishet men, however peripherally, however subconsciously, is a huge barrier in the constant, ongoing fight for equality. The landlord of this story cannot penetrate the narrator’s body, but by reading her writing without her consent, he is penetrating her mind, her privacy.

WOMAN AS HOUSE IN A CHILDREN’S ANIMATED FEATURE FILM: MONSTER HOUSE (2003)

As the house, Constance is therefore enormous, insatiable, crazed — just as she was in life. Mr. Nebbercracker, in contrast, is small and skinny, the one who placates her great rage. This portrayal of a fat woman as out of control with huge appetites (whether for food or for sex) – as, literally, a maneater – is unfortunately all too common. In fact, the very difference in size between a large wife and a smaller husband, whether in literature, film, or real life, communicates the message that she is the dominant partner. These stereotypes of fat women are particular to fat women — the reverse wouldn’t work. There are no cultural figures of fat men whose appetites must be controlled by their skinny wives.

Further, the house is only silenced when it is destroyed, at which point we see Constance’s ghost dancing with Nebbercracker before swirling off into the sky. Nebbercracker then breaks down in relief that he and Constance have finally been set free. Thus, it is only through Constance’s destruction that her appetite is forever controlled.

What’s wrong with this picture? Monster House doesn’t merely reinforce negative stereotypes – it depends upon them. There would be no plot if not for the purposefully grotesque figure of Constance.

Blogging While Feminist

See my analysis of Monster House here. The popular website TV Tropes seldom interrogates gendered aspects of tropes, but the following trope clearly plays into another harmful trope about women: That women are volatile and ‘crazy’:

Hair-Trigger Temper: The house can go from calm to extremely angry with minimal provocation. So could the woman possessing it.

The Monster House entry at TV Tropes

If you click through to other examples of ‘hair-trigger temper’ in fiction, it doesn’t seem particularly female-skewed. But note also: Mr Nebbercracker also has a hair-trigger temper. He goes off half-cock when a children’s sports ball lands in his front yard. Yet it’s the woman-house used as stand-out example of the trope. Hair-trigger men go mostly unnoticed as examples of hair-trigger anger.

Another clear example of the Monstrous Woman As House trope can be seen in What’s Eating Gilbert Grape? (1993). The empathetic character is Gilbert. His monstrous (very fat) mother is the monstrous woman upstairs. And true to the trope, she must be destroyed before the empathetic male character, Gilbert, can start to live his life on his own terms. Again, What’s Eating Gilbert Grape doesn’t merely reinforce stereotypes — it depends on them.

Let’s take a look at who created those stories.

What’s Eating Gilbert Grape? was directed by Lasse Hallstrom and written by Peter Hedges. (Both men.) The main character is a young man (played by the increasingly despicable Johnny Depp).

Monster House was created by directed by Gil Kenan (a man) and written by Dan Harmon, Rob Schrab and Pamela Pettler (a gender balance which matches the gender balance of the child characters: two boys as main characters with a girl who turns up, partly to do the ‘homework’ aspects of saving the day, partly as a sassy love interest).

It seems to require a woman as main creator to interrogate the problematic conflation between woman and house in fiction. Alice Munro has done it for us in “The Office”. Not only does sympathy lie with the woman-as-house, but the narrative contains nuance. She shows us the cultural forces at play.

RED FLAGS

The narrator is writing this story with the clarity of hindsight. I have two hopes for her:

- That she found another wonderful place to write

- That she posted this piece for the former landlord to read, since he so desperately wanted her to write a story about him.

It is always, always easier to see red flags in hindsight and no one should chastise themselves for failing to pick them in real time.

Note that, right from the start, the narrator trusted her instincts. She knew that if she were too friendly that would not go well. She also know that if she were too rude that would not go well, either. In hindsight, the red flags are clear:

- The landlord is attempting to buy her with gifts, which is possible because he controls the finances. (Whoever controls the resources controls the people.)

- His humility is false. (He apologises for taking up her time while continuing to take more and more of it.)

- He refuses to listen to the narrator, or respect her as a separate person with her own needs and desires. Instead he pastes his own needs and desires onto her, and expects her to bend herself around them.

- He tries to tell her who she is.

- He tells her that she and he are alike. (Always a bad sign.)

These all seem obvious to the reader because they’re written by a narrator who has already processed the flags but, in real time, in the fictional world of the story, these small incidents don’t snap into focus until she catches him reading her work. Until now, each of his actions had plausible deniability: I was just being nice. I was just giving you gifts. I was just trying to make this room comfortable for you. I was just trying to help you out with story fodder. I was just passing the time of day. I was just…

THE LANDLORD’S WIFE IN “THE OFFICE”

I hesitate before calling her the landlady because although she does the job of finding tenants (and releasing them), she is required to run every decision past her husband. This is perhaps just a means by which to negotiate rental rate and so on, but if we go by the husband’s behaviour towards the narrator, in which he turns everything about the narrator into a story about him (quite literally), the marital power imbalance can be deduced.

Alice Munro paints a portrait of a wife who is strangely distant, in a Stepford Wives kind of way. (The Stepford Wives is a 1972 satirical feminist horror novel by Ira Levin. The 2004 film adaptation isn’t very good.)

For Joanna, her husband, Walter, and their children, the move to beautiful Stepford seems almost too good to be true. It is. For behind the town’s idyllic façade lies a terrible secret—a secret so shattering that no one who encounters it will ever be the same.

At once a masterpiece of psychological suspense and a savage commentary on a media-driven society that values the pursuit of youth and beauty at all costs, The Stepford Wives is a novel so frightening in its final implications that the title itself has earned a place in the American lexicon.

THE LITTLE POT PLANT

The landlord gifts the narrator a small pot plant, ostensibly as an apology gift for intruding on her space. But this gifting palaver is also a test. If she accepts the plant, she’ll accept further intrusions.

Understanding this dynamic (because it is so familiar), the narrator hates the pot plant. Yet she feels obliged to take care of it. Her taking care of the plant lasts precisely as long as she feels obliged to put up with the man who gifted it to her. In this way, the thriving/withering state of the pot-plant serves to mirror the narrator’s capacity for patience.

It does more than this, though. Without the woman’s care, the pot plant dies. Likewise, without the attention of a woman, the landlord withers, not literally but emotionally. The inevitable withering of the plant demonstrates the very real labour performed by women, invisibly. Without feminine attention and caregiving, society fails to thrive. Women’s work is real work. Society understands this, but also denies it.

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE TEAPOT

Next the landlord gifts her a teapot covered in gilt and roses, a multivalent symbol.

- The roses are symbolically important. Not only are they a symbol of beauty (and therefore expected femininity), they also come with their own barbs.

- The gilding indicates something which looks good on the outside, but is a cover for a different sort of material underneath. Gilt is also homophonous with ‘guilt’. The gift is intended to provoke guilt in the recipient should she refuse it.

- The teapot has a feminine shape, much like a witch’s cauldron (which works so well as a symbol partly because of its pregnant-belly shape).

THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN A DOUBLE STANDARD AND A DOUBLE BIND

The narrator is in a double bind in dealing with this man, and Alice Munro describes it perfectly. When dealing with such men, women can’t win: If she is too friendly he will interpret this as an invitation. If she is too unfriendly, he will make her life a misery, until she must curtail her own freedoms and leave. There is no happy medium here.

Alice Munro expresses this double bind in a few ways to be sure we get it (belt and braces, hah):

I took to coming upstairs on tiptoe, trying to turn the key without making a noise; this was foolish of course because I could not muffle my typewriter.

“The Office” by Alice Munro

Feminist linguist Deborah Tannen has written and spoken about this issue, though she is sometimes misinterpreted as advising women to alter their behaviour. She doesn’t advise this at all, but is more of a realist, encouraging women to trust their intuition in any given situation:

I never say women should apologise less [because of] the double bind.

A double bind is worse than a double standard. Double standard means women are judged by a different standard, but they can still meet that standard. They have to work twice as hard, they have to be twice as good, but they can meet that standard.

A double bind is a situation where you have two sets of requirements. And anything you do to fulfil one violates the other.

In the workplace, our expectations for how a person in authority should speak is opposed to our expectations of how a woman should speak.

If she fulfils expectations for how a woman should speak, she’s lacking in confidence, lacking in competence. If she talks in a way that a manager or person in authority’s expected to speak she’s too aggressive. People just don’t like her. And that certainly comes up all the time in public life. It’s extremely difficult for women in public life … think of women on the campaign trail. To be forceful, talk about what they’ve done, to show emotion — often anger — at things that are happening, things they don’t think are good, all those things are unacceptable in a woman.

So, I never said in the book [Talking From Nine To Five] that women should stop apologising. In fact, one very specific example a woman told me when she was first promoted: She talked in the way the previous person who had held that position talked. He happened to be a guy. What they tell people very often in positions of authority, “Never apologise, never explain.” And she was getting a very bad reaction. She found that when she began to apologise more she got a better reaction. “Oh, I’m so sorry…” [laughs] Because people liked her more. This is what they expected from a woman.

So I’m not giving advice either way. I’m saying you have to be cautious, you have to have antennae for the effects of the ways you’re speaking and change the way you’re communicating if you feel comfortable doing so.

It’s extremely frustrating that it’s always women who are asked to change.

[interviewer mentions The Likeability Trap: How to Break Free and Succeed as You Are by Alicia Menendez.]

Everyday Conversation in Relationships with Debora Tannen, Psychologists Off The Clock Podcast 21 October 2020

TALKING FROM NINE TO FIVE (2013)

In her extraordinary international bestseller, You Just Don’t Understand, Deborah Tannen transformed forever the way we look at intimate relationships between women and men. Now she turns her keen ear and observant eye toward the workplace—where the ways in which men and women communicate can determine who gets heard, who gets ahead, and what gets done.

An instant classic, Talking From 9 to 5 brilliantly explains women’s and men’s conversational rituals—and the language barriers we unintentionally erect in the business world. It is a unique and invaluable guide to recognizing the verbal power games and miscommunications that cause good work to be underappreciated or go unnoticed—an essential tool for promoting more positive and productive professional relationships among men and women.

THE LIKEABILITY TRAP (2019)

Be nice, but not too nice. Be successful, but not too successful. Just be likeable. Whatever that means?

Women are stuck in an impossible bind. At work, strong women are criticized for being cold, and warm women are seen as pushovers. An award-winning journalist examines this fundamental paradox and empowers readers to let go of old rules and reimagine leadership rather than reinventing themselves.

OTHER EXAMPLES OF WOMEN WHO FIGHT FOR THE RIGHT TO WRITE

The Wife by Meg Wolitzer

Meg Wolitzer’s novel The Wife now has a film adaptation starring Glenn Close, and is a 2003 example of how one (fictional) woman writer achieved publication in a hierarchical literary environment with men holding power over who is published, read and reviewed.

A husband. A wife. A secret. Behind any great man, there’s always a greater woman.

Joe and Joan Castleman are on an aeroplane, 35,000 feet above the ocean. Joe is thinking about the prestigious literary prize he is about to receive and Joan is plotting how to leave him. For too long Joan has played the role of supportive wife, turning a blind eye to his misdemeanours, subjugating her own talents and quietly being the keystone of his success.

The Wife is an acerbic and astonishing take on a marriage from its public face to the private world behind closed doors. Wolitzer has masterfully created an expose of lives lived in partnership and the truth that behind the compromises, dedication and promise inherent in marriage there so often lies a secret…

Related: Who was Einstein’s first wife? Part 1 – Debate heats up over Mileva’s role in Albert’s science, a Science Friction podcast.

JANET FRAME’S REAL-LIFE EXPERIENCE

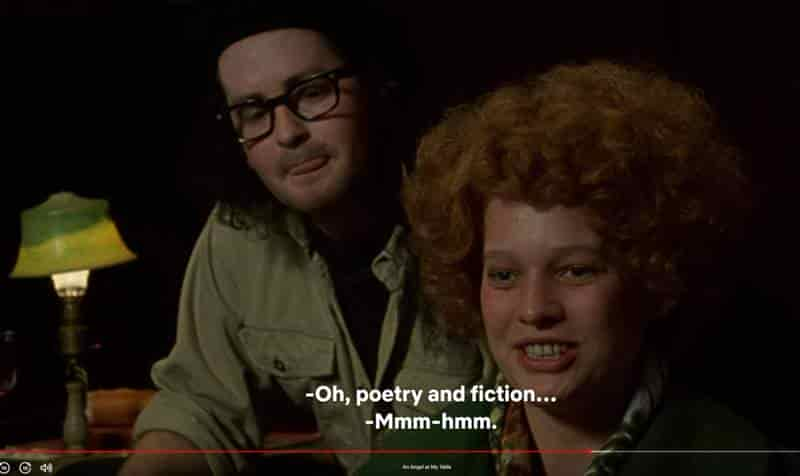

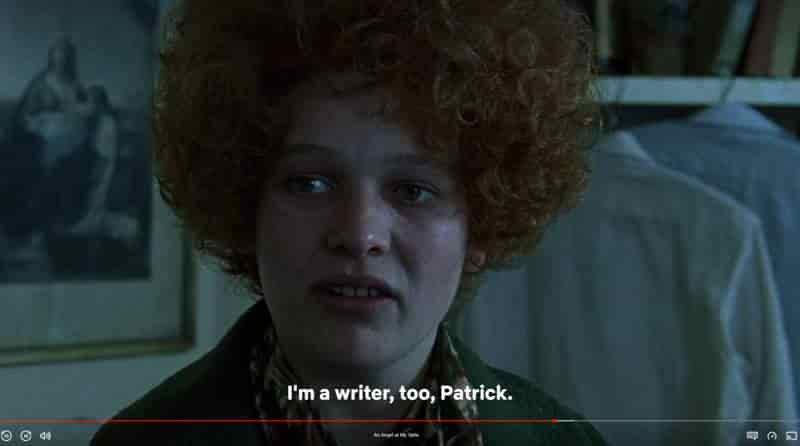

Janet Frame is now considered one of New Zealand’s most talented writers the country has ever produced, and she did achieve a measure of prestige in her lifetime. However, as a young woman travelling in Europe on a writer’s grant, she experienced the expected condescension. This came from all directions, from her own native working-class people who despised the literary class in general, and also from fellow writers, who expressed surprise that someone so… unassuming, as softly spoken as Janet could possibly have had an entire book of short stories published as well as a novel! “Only in New Zealand,” Janet replied, hoping not to alienate her new friends by seeming too uppity.

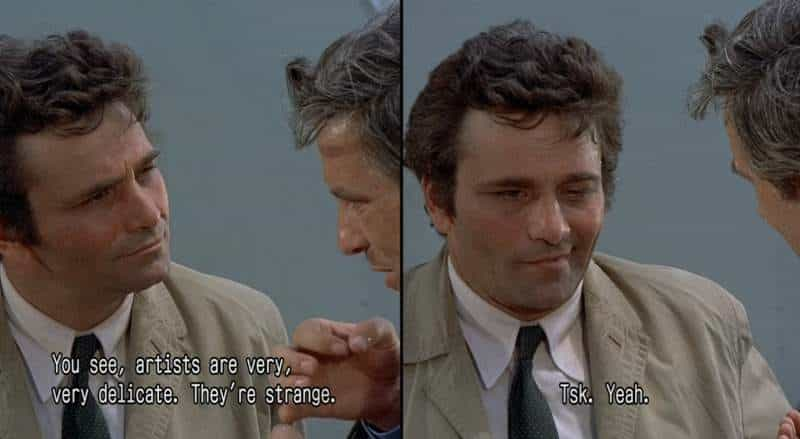

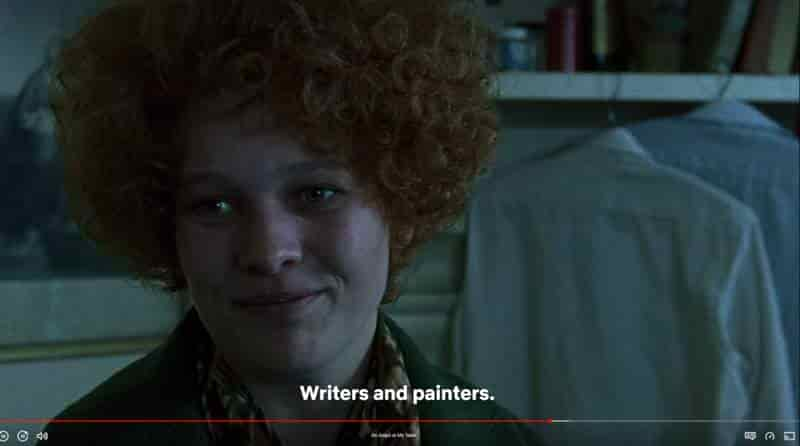

The following are screenshots from Jane Campion’s 1990 film adaptation of Janet Frame’s three volume autobiography. The middle volume is called An Angel at My Table, and became the title of the film. Here is Janet, new to London, out for an evening with literary and artist types.

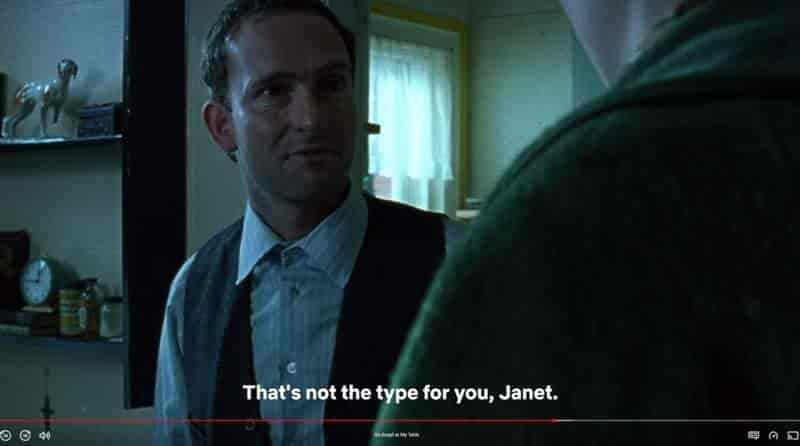

The next morning, Janet returns to the house where she is renting a room. Another tenant puts himself in charge of showing her around the house. Patrick is an Irish fellow who has got it into his head, with zero encouragement, that he and Janet will become an item.

Unlike the mother in Alice Munro’s “The Office,” who at least has class and money on her side, Janet Frame is dealing with the intersection of working class attitudes and gender. She came from a working class family herself, and now she’s an immigrant to London. Added to that, Janet Frame was almost certainly Autistic, and men such as her Irish co-tenant would never have been able to put that into words, but would have most definitely spotted a vulnerability in her, which they saw fit to exploit, first by telling her who she was, and who she is meant to be. There are certain men for whom this is their modus operandi when interacting with women. It’s as if they don’t know how else to be, at once protective, avuncular, controlling, domineering, condescending, with no concept that a woman is a separate human with her own needs and desires.

I’m not entirely convinced such men avoid dishing out life advice and so on to other men, either. The difference is, other men haven’t been socialised to put up with it, in fear of the ever-present threat of violent retribution.

“That’s not the type for you, Janet,” Patrick tells her, on the assumption he knows Janet better than she could possibly know herself. The narrator of Munro’s “The Office” endures the same invasion as the landlord insists that women need colour, women need carpet, women need to drink tea instead of coffee. Like a desperately hopeful lover, he draws imaginary similarities between their personalities:

He said that tea was better for the nerves and that he had known right away that I was a nervous person, like himself.

“The Office” by Alice Munro

In An Angel At My Table, Patrick tells Janet he’s not comfortable with all their ‘muckin in’. Note the crucifix dangling in the background. He doesn’t approve of his woman boarder’s perceived ‘lifestyle’. For him, writers — and writers, especially woman writers, no doubt — go hand in hand with an ineffable salaciousness. If women are secretly writing things down in books — and gadding about outside the house after dark — they surely have something to hide. This woman must be saved from herself.

Been doing some thinking tonight, and I have something to share here for anyone who needs to hear it.

One of the biggest pieces of bullsh!t I was ever told by someone (a parent, in this case) was that if I was hiding something, it was because I was ashamed and knew it was wrong.

I cannot articulate enough how inaccurate that is. A lot of the time, we hide stuff because we know how we might be treated for it and we haven’t got the energy/endurance to deal with it, or we plain just don’t want to have to. And that’s valid!

This can apply to pretty much anything, but certainly to sexual orientation, gender identity, etc.

So whoever needs to hear it, if there’s any aspect of yourself that you’ve hesitated to share with anyone/everyone and you’re feeling guilty about it, then reassess that guilt because it’s probably unfair.

anonymous on Tumblr

The great irony of this for Janet Frame: It was medical men who almost ended Janet’s life as she knew it, and her writing which literally saved her. If she had not won a literary award for her first collection of short stories, she would not have been released from the psychiatric ward in New Zealand.

In person, young Janet Frame came across as laconic, shy, somewhat lacking in basic life skills and easily manipulated. But read her wonderful character sketch of Patrick the landlord (in the autobiography) and it is apparent how much else is going on inside her head, not able to be depicted via screen:

Patrick Reilly was beginning to acquire mythical attributes as The Greeter who was also The Warner: even during this first meeting he began to list the lurking dangers of Cedars Road, Clapham Common North Side. I supposed that he would deal later with London and the World.

He took me to his room next to the bathroom in the main house and I sat silently watching while he filled a kettle from the tap on the landing and lighting a gas ring on the table, boiled the water for a cup of tea. I knew I was seeing for the first time the ritual of a way of living that was new to me, where people lived alone in one room of a large house of many rooms, each self-contained except for the shared bathroom and lavatory and the water tap above the basin in the landing where Patrick had filled the kettle for our tea. Already I had noticed two men with buckets fetching their supply of water either for washing or for drinking.

‘Women are not popular with landladies,’ Patrick explained. ‘They leave hair in the bathroom and are always washing clothes.’

He set two cups and saucers at one end of the large oilcloth-covered table, and lifting a full bottle of milk from a basin of water and grasping the bottle at both ends he gently rocked the milk to and fro, then lay it sideways on the table beside the cups and saucers.

‘Bluetop, Jersey Island milk. I buy the best,’ he said. ‘That’s how you spread the cream.’

He made the tea.

‘I wait five minutes, no more, no less for the infusion.’

He said ‘infusion’ in self-admiring way, like a surgeon who has diagnosed and will operate correctly.

He then probed apart the wrapping from a tube of biscuits, holding them for me to examine before he tipped three or four onto a plate.

‘Digestive. Chocolate digestive. The dark kind.’

The tea was now brewed. I bit into my chocolate digestive and began to drink my tea.

‘It’s Tetley’s Tips,’ Patrick Reilly said. ‘And the biscuits are Peek Frean.’

Peek Frean.

He spoke in a satisfied way as if he had achieved another point on the path to perfection.

Mirror From Envoy City, the third volume of Janet Frame’s autobiography

What Janet Frame shows here, and what Alice Munro depicts equally well in fiction: The sexual suspicion which followed woman writers around like a cheap brothel perfume. Woman writers and artists are hardly alone in fielding ridiculous, unwanted responses from strangers who learn you’re a writer. What commonly happens when you say you’re a writer:

- Your interlocutor immediately worries that you’re famous and they should have known about you. In reality, the vast majority of writers are like cooks and dishwashers. Sure, some writers are famous, and so are some celebrity chefs but, as far as I know, no one meets kitchen staff and immediately presumes fame.

- Next, they want to know how much they should respect you. This involves a series of questions designed to determine how well-known you are and how much money you earn. That’s their shortcut to understanding how Good you are and how deferential they need to be. An unpublished writer (or someone who refuses to disclose their publication history) is immediately relegated to the hobbyist. I suspect it is here that men (and masc presenting writers) fare worse than women, by one dimension. Women are allowed their artistic hobbies because of course their main job is house, husband and children. Men who can’t earn money from their toils are judged more harshly and their very masculinity comes into question.

- Where women (and femme presenting writers) fare worse is the suspicion that a woman writer is a little crazy (for having grandiose plans to be read), that she’s hiding something or is generally up to no good, that her time and headspace does not belong to her, not really. Also, no matter what a woman does, it is imbued with sexuality in the eyes of a straight man who happens to find her attractive. And because attraction exists, he cannot move beyond seeing her, in his own imagination, as partner material whose life decisions, major and minor, automatically become his business. #NotAllMen #YesAllWomen

- What Alice Munro also captures so well, common to almost anyone who has ever disclosed themselves as a writer: The barrage of free ‘ideas’ from people who would write something down themselves, if only they had the time. But writers are never short on ideas. The issue is always the inverse: Too many ideas and not enough lifetime to develop them all, which is why the narrator of this story values her time so fiercely. (“Writer’s block” happens not for lack of ideas, but for realising you’re not quite ready to be writing something down, or because your plot has a hole in it, or your day-to-day life has filled with difficulties which means you cannot presently give your mind over to the mammoth task of imagining a story-world peopled with fictional characters.)

FOR FURTHER INVESTIGATION

OTHER STORIES IN DANCE OF THE HAPPY SHADES (1968)

- “Walker Brothers Cowboy” — A woman looks back at her 1930s childhood. Her family has 2 or 3 months earlier lost the family fox farm and moved to a small town on the edge of Lake Huron, where the father has started a new job as a door-to-door salesman. Meanwhile, the mother sinks into a depressive state. One day, the father takes the narrator and her younger brother on a ride, where he visits an old friend/lover. The daughter learns that her father had another sort of life once.

- “The Shining Houses” — In a new neighbourhood, many houses have been built next to an old one. The owner of the older house, Mrs. Fullerton, does not take care of her property to the extent that the owners of the new houses would like. They conspire to get rid of the old poultry-farming witch. Only our narrator seems conflicted.

- “Images” — A little girl is the narrator of this double character study: A second cousin who came to take care of the household while her own mother was sick, and a man with a psychotic mental illness who lived alone in the woods. After meeting the man in the woods, the little girl learns not to be afraid of the woman who has infiltrated the household to take care of them all.

- “Thanks for the Ride” — This story is written with the viewpoint character of a young man. He has just finished school and is out with his older cousin with the purpose of losing his virginity. Together they pick up some ‘loose’ girls. The whole experience is perfunctory and defamiliarizing.

- “The Office“

- “An Ounce of Cure” — A young teenager is pining after a boy who dumped her months ago for another girl. She can barely think of anything else. One night she is babysitting when she spies three bottles of liquor on the bench. She accidentally gets very drunk and very caught out. Her reputation is ruined. But as an older woman looking back on this time, she is glad it happened.

- “The Time of Death” — A mother who lives in one of the squalid cottages on the edge of town has lost a child in a terrible accident. The village gathers round, but how genuine are they in their grief?

- “Day of the Butterfly” — Two girls at a primary school are ostracised. One is the narrator, now grown, ostracised for being an out-of-towner who doesn’t wear the right clothes. The other is more ostracised still, because her parents are immigrants, because she smells like rotting fruit, and because her brother needs her to accompany him to the toilet. When this girl is dying in hospital from child leukemia, the young narrator is filled with inexplicable grief. It is now too late to be a real friend to this outcast, and anything she does in kindness will feel empty and pointless.

- “Boys and Girls” — An outdoorsy farm girl loves helping her father on the fox farm but realises she’ll very soon be required to go indoors to help her mother with domestic work. In contrast, her younger brother, far less conscientious, will be allowed to stay outside and work with the animals, enfolded and welcomed into the masculine world.

- “Postcard” — A woman around the age of 30 has been seeing a man for years. They’re long-term partners. The reason they haven’t married: He’s waiting for his mother to die. His mother wouldn’t approve of him marrying the narrator, we deduce because of the wealth disparity. Unfortunately for the narrator (Helen), turns out the guy never intended to marry her anyway. He sends her a postcard from Florida telling her how he’s having such a good time. Next minute, Helen’s best friend is round to break the bad news: It’s been published in the paper, the lover is getting married to someone else after all this time. The weasel didn’t have the gumption to let Helen know. So she goes round to his house, stands outside and expresses her grief in a very vocal way.

- “Red Dress—1946” — A thirteen-year-old girl’s first ball. Her mother sews a red dress with a princess neckline. Suddenly she looks much older. She barely recognises herself in the mirror, and longs for childhood again. Almost all the girls around her are obsessively interested in boys. Everyone, that is, except one other girl who says she despises boys, and plans to support herself by working as a P.E. teacher. But by aligning herself with this queer girl, our thirteen-year-old risks much. What will she do? Will she take up the offer of friendship?

- “Sunday Afternoon” — Seventeen-year-old Alva has recently finished high school and started working as a maid for the mega-wealthy Gannetts. Today they are hosting a party at their mansion and Alva must navigate a delicate social situation: They want her to feel part of the family, but what does that mean, exactly, when you’re actually the paid help? Alva must also navigate the men who enter the house, several of whom express sexual interest in her. This isn’t your run-of-the-mill, predictable young-woman-is-seduced storyline, but Alice Munro keeps readers in audience superior position as we watch with bated breath what happens to Alva in this big, lonely island of a house. We’re left to deduce most of it.

- “A Trip to the Coast” — An eleven-year-old girl called May lives with her mother and grandmother (mostly her grandmother) in a general store in a three-house township. There’s nothing to do in this one horse town. But today she’s looking forward to same-age company. However, the “company” is a total let-down, and so her grandmother, for the first time ever, suggests the two of them take a trip to the coast. But then another visitor comes. A customer who declares himself an amateur hypnotist. This story ends on a cliff hanger, and I don’t believe Munro has given us enough of a symbolic layer to fill in the gaps for ourselves. I believe we’re supposed to feel exactly as unmoored as eleven-year-old May, waiting out front of the store in the rain.

- “The Peace of Utrecht” — Numerous critics and scholars consider this story the jewel of the crown of Munro’s first collection. Considering that, it’s baffling why it doesn’t make it into more Selected and Collection volumes. It’s certainly the most overtly personal of Munro’s early stories, and she has said in interview that this one changed the way she wrote. Until writing “The Peace of Utrecht” she’d written to be a writer. Now she wrote because she knew only she could write this story. The biographical relevancy: young Alice Munro cared for her mother over many years as her mother lived, then died, with Parkinson’s disease.

- “Dance of the Happy Shades” — An emotionally astute and very observant adolescent girl is required to accompany her mother to an embarrassing recital with the elderly, unfortunate-looking spinster teacher whose spinster sister is recently bedridden due to a stroke. The story is told via the slightly baffled viewpoint of the girl, who is required to recite a tune on the piano at these excruciating annual events.

I frequently find myself recommending this book, which is surprisingly funny given the depressing subject matter.

This story was an example of how some adult men target adult women. Do we call it grooming? Probably not. But there’s overlap, mostly to do with testing boundaries.

Here are some resources to do with red flags and grooming specifically regarding adult groomers and child/teenage victims:

- Online Grooming: What Is It, How Does It Happen and What Your Family Needs To Know

- 6 Stages of Grooming Adults and Teens: Spotting The Red Flags

- What Parents Need to Know About Online Grooming

- Sextortion

Red flags regarding adults who know you’re a minor:

- Grooming doesn’t work unless the predator is outwardly charming, so a charming, polite persona is a given.

- They enter your space by asking personal questions

- Asking you personal things, perhaps about your body

- Telling you personal things you didn’t ask and didn’t want to know

- Asking for nude pictures of yourself

- Presenting themselves as safe adults

- Their online followers are mostly minors

- They try to convince you that you are best friends

- They talk about you and them wanting a relationship

- Tells you how mature you are for your age

- Tells you you’re not like other girls (or boys)

- Lavish you with gifts

- Tell you secrets about other people

- Tell you to keep the relationship secret

- Making you their confidante, in general, hoping to make you feel important that they’ve shared secrets with you

- Moving conversations towards the sexual

- Threaten harm or self-harm if you break contact with them

- Put the onus on you not to ruin the relationship you have. How they say you’ll ruin the relationship: By telling another adult about it.

- They may push you to change platforms to an online communication method that’s more private, or harder to save and share.

CLAIMING SPACE

In this episode of Talk Nerdy, Cara is joined by Eliza VanCort, author of “A Woman’s Guide to Claiming Space: Stand Tall. Raise Your Voice. Be Heard.” They talk about her harrowing childhood and recovery from a traumatic brain injury, which influenced her work in women’s empowerment and anti-racism.