Meg Elison has written a McSweeneys post about The Gaze which strikes a chord.

IF WOMEN WROTE MEN THE WAY MEN WRITE WOMEN.

At The Guardian, Lindesay Irvine (incidentally, a man) responded to this spoof gender reversal with:

Anyone who’s ever had a brush with cultural studies will be familiar with Laura Mulvey’s influential theory of the male gaze in film and fine art and photography. But I’d never quite thought the male gaze could function equally well in fiction.

Yes, of course the male gaze functions equally well in fiction.

I’m sorry to say that this gaze is just as prevalent in children’s fiction.

After chuckling at Meg Elison’s piece I made a note to blog an example from children’s book world. I wasn’t actively looking for it because I have plenty of other ideas for blog posts, but it took less than a week to stumble upon an example.

Here we encounter the male gaze by the time we’re halfway down the middle of the very first page of an upper middle grade/young adult novel:

One

“Haven’t you loaded that chainsaw on yet?” Lisbeth asked.

Craig Dawson paused with one hand on the helicopter cabin door. He breathed deeply.

“I’ve been checking to make sure its tank’s empty,” he said. “You never carry anything with petrol in it, if you’re in a chopper.”

“Is that right?” Lisbeth’s voice was as cool as always. “Thanks for the lecture.”

This time, Craig breathed deeply twice. He slide the chainsaw into the main locker inside the Mongoose’s cabin, snapped the safety clips over it, then pulled the storage net tight, holding it in place.

“OK,” he announced as he straightened up. “That’s the lot.”

Lisbeth had finished stacking the supermarket bags of milk, fruit and vegetables in the Mongoose’s small locker. Now she stood with perfectly clean hands on the hips of perfectly fitted jeans, watching Craig.

Cold Comfort by David Hill, 1996, published with the support of Creative New Zealand

It’s hard to imagine the character of Craig standing in perfectly fitted jeans (unless we’re reading specifically gay fiction, marketed quite differently), and if you’re wondering about the narration of Lisbeth watching Craig, well, that’s it. I didn’t cut anything pertinent off by ending the quote there. The story goes back to Craig.

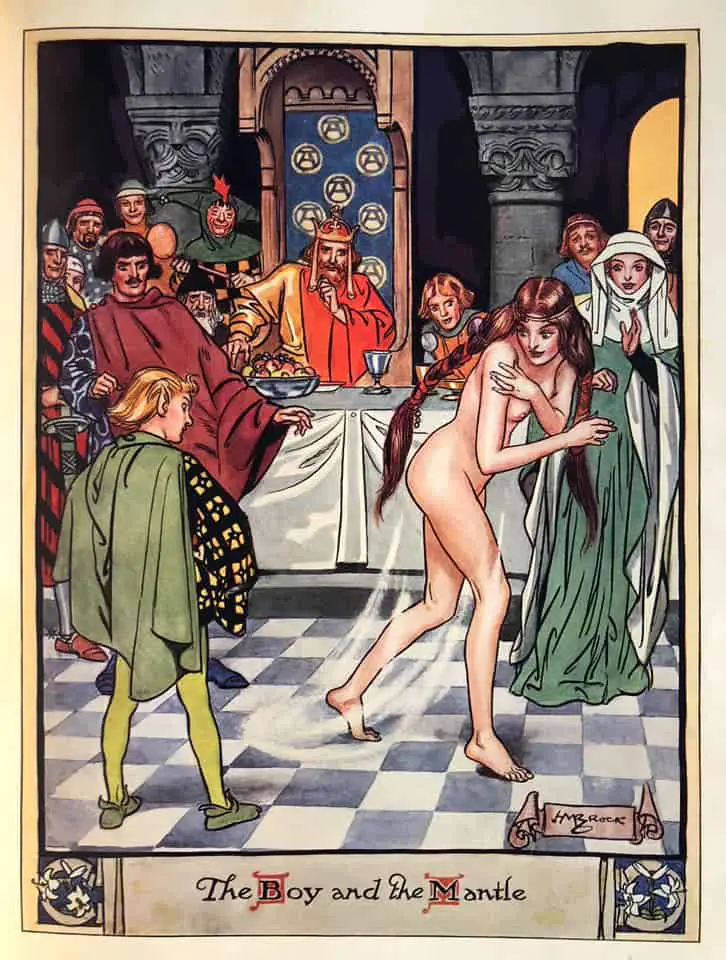

We might call this literary candaulism. Candaulism is a sexual practice, or the fantasy of the practice, where a man exposes his female partner, or intimate images of her, to others for their voyeuristic pleasure.

Here, a male author exposes his female character, or intimate images of her, to young readers for their voyeuristic pleasure.

Isidor Sadger hypothesized that the candaulist completely identifies with his partner’s body, and deep in his mind is showing himself. Except in this particular instance, as in most, the author does not intend to show anything about the narrator. The narrator is an unseen, all-seeing, all-knowing, trustworthy persona, whose view of everything is the implied accurate one.

This unseen third person narrator is unambiguously male. The author chooses to pull in more closely to Craig’s head than to Lisbeth and there are writerly reasons for that; the reader’s sympathies are supposed to lie with Craig, not with Lisbeth. In short, this tendency to sexualise the female body rather than the male body is partly to do with how many more books are written about boys and men. (In children’s books, across the board, it’s about 3 male characters to every 1 female.)

David Hill’s work has been widely read (and taught) in New Zealand schools (I’ve had to teach his work myself, in a girls’ high school) and, like a couple of other big name educational authors from my home country (William Taylor is another), this is typical of the sort of narration that gets purchased by schools as class sets. It’s written from a blokey point of view with sympathies directed at the put-upon male character whose opponent is the annoying but sexually alluring female character. These characterisations are thought to engage those hard-to-reach reluctant boy readers.

(Fortunately in New Zealand reading lists have become a bit more diverse since the 1990s. This has happened in part because teachers have started to acknowledge that it’s not just boys who are failing to take up with fiction these days.)

However, when it comes to the male gaze, there’s more to it.

FOR MORE ON THE MALE GAZE

- One of the most important essays in contemporary film theory: Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema by Laura Mulvey (1975), which has some weird Freudian stuff in it but is still relevant for the pretty standard dichotomy between the watched and the watchers.

- Fashion As A Way Of Avoiding The Male Gaze from Merf, Thinking Is Hard

- The Peeping Press: Understanding the Male Media Gaze from Jessica Valenti

- The Omniscient Breasts: The Male Gaze Through Female Eyes by Kate Elliot

- From the classroom to the boardroom, beauty is in the eye of the beholder. And the beholder is always a man, from Soraya Chemaly

- Opinion: Video games and Male Gaze – are we men or boys? from Gama Sutra

- Six Reasons Female Nudity Can Be Powerful from Salon

- Why Do Actresses Have To Do The Org*sm Face? from Daily Life

- How Can You Tell if You’re Being Sexually Empowered or Objectified? Ask Yourself This Simple Question from Everyday Feminism

- Red Sparrow is Male Gaze as Female Empowerment from The Mary Sue

- The Male Gaze master class by Jill Soloway

- Further analyses showed that men’s preferences for larger female breasts were significantly associated with a greater tendency to be benevolently sexist, to objectify women, and to be hostile towards women. (from Men’s Oppressive Beliefs Predict Their Breast Size Preferences in Women, PubMed.)

- The consequences of the media’s objectification of women from The Not So Quiet Feminist

- Staring Is Caring: Anti-cancer campaigns often use fundraising or awareness for then cause as an excuse to sexually objectify women. (Not to mention animal rights!) from Osocio

- Why lads’ mags don’t ‘celebrate women’ by using their bodies to sell copies: The Five Worst Arguments from Newsweek

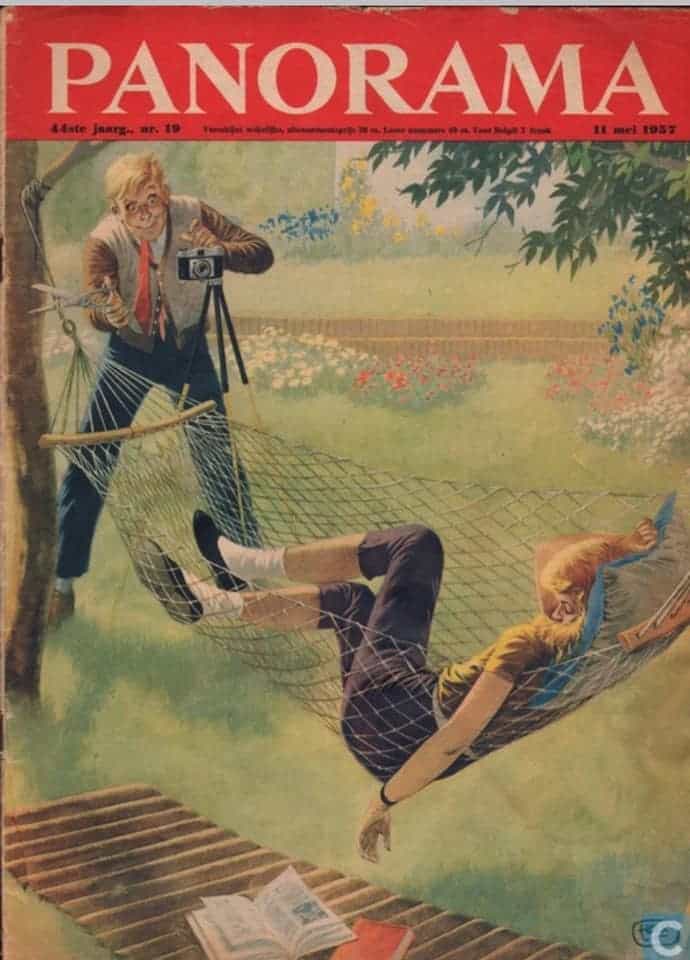

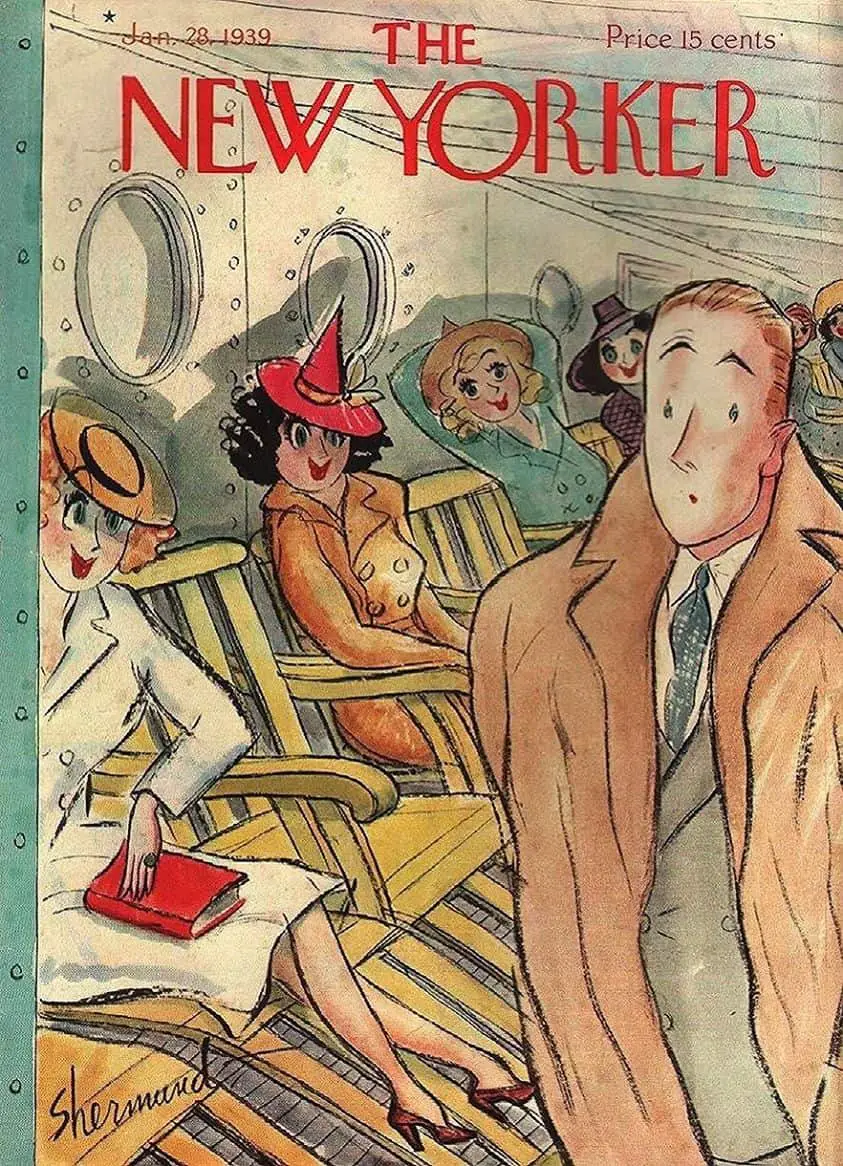

The commercial below dates from the 1980s and is an advertisement for the revitalisation of Melbourne inner city. This is the ‘humour’ of my 1980s childhood, and no one in my orbit was remarking upon it at the time. Women surrounded by pervy men (and enjoying the attention) was played for laughs. But trust me, some of us always felt the inherent creepiness. I did.

THE MALE GAZE IN WORKS BY WOMEN, FOR YOUNG WOMEN

When the male gaze is internalised by women and directed back upon ourselves it is called ‘self-objectification’.

For more on that I would direct you to the work of Peggy Orenstein. You can find numerous podcast interviews with Orenstein as she talks about her book Girls and Sex.

Author Peggy Orenstein says that when it comes to sexuality, girls today are receiving mixed messages. Girls hear that “they’re supposed to be sexy, they’re supposed to perform sexually for boys,” Orenstein tells Fresh Air’s Terry Gross, “but that their sexual pleasure is unspoken.”

While researching her new book, Girls & Sex, Orenstein spoke with more than 70 young women between the ages of 15 and 20 about their attitudes and early experiences with the full range of physical intimacy.

She says that pop culture and p*rn*graphy sexualize young women by creating undue pressure to look and act sexy. These pressures affect both the sexual expectations that girls put on themselves and the expectations boys project onto them.

from the Fresh Air interview with Terry Gross

Peggy Orenstein has given us a sobering set of up-to-date statistics in this book, especially if you’ve ever read the work of Shere Hite — published 1976 — and wondered if things have improved since then.

Popular YA authors, as you might expect, are very well attuned to today’s teens and face a difficult task: Negotiating that fine line between telling the reader, “I know how it is, I will depict it as it is no matter how awful so that you know you’re not alone” and “This is how it could be. Look at this character — behave like this.”

The sex scene in Gayle Foreman’s If I Stay is an example of the former. In a flashback scene, our main character Mia tells the reader about the first time she had sex, with her more sexually experienced, uber-cool boyfriend Adam. He tells her to play him like a cello, which some reviewers find a bit weird (ouch?) but the point is, he’s offering her a diversion tactic to put her at ease. My issue is instead with the (very relatable) contrast between how easily Adam is able to sink into the sensations versus how much harder it is for Mia. This isn’t only attributable to the difference in sexual experience between them. It’s also to do with Mia’s self-objectification.

Here she is, empowered by her newly-realised ability to arouse, focusing on her partner’s pleasure:

I reached for the bow and brushed it across his hips, where I imagined the bridge of the cello would be. I played lightly at first and then with more force and speed as the song now playing in my head increased in intensity. Adam lay perfectly still, little groans escaping from his lips. I looked at the bow, looked at my hands, looked at Adam’s face, and felt this surge of love, lust and unfamiliar feeling of power. I had never known that I could make someone feel this way.

Now they ‘switch roles’:

When I finished, he stood up and kissed me long and deep. “My turn,” he said. He pulled me to my feet and started by slipping the sweater over my head and edging down my jeans. Then he sat down on the bed and laid me across his lap. At first Adam did nothing except hold me. I closed my eyes and tried to feel his eyes on my body, seeing me as no one else ever had.

Except the roles haven’t really been switched, because while Adam’s moaning seems to indicate an ability to fully enjoy the experience, Mia’s arousal is instead fully reliant on seeing her body from the boy’s point of view.

That’s ‘self-objectification’ right there. Most girl readers will identify with this scene and think nothing of it. In case you’re wondering, Gayle Foreman does spend a paragraph describing Mia’s orgasm (without using the word orgasm), but the work of Orenstein highlights just how much of a fantasy scene this is. For many girls having an early sexual experience with a boy, the balance between self-objectification and focusing on his pleasure over her own overwhelms her ability to sink into her own pleasure.

FOR FURTHER INVESTIGATION

Episode 134 of the Then Again Podcast: The Portrayal of Women in Western Art. “Our Research Intern Kate Chenault discussed the portrayal of women in Western art with Dr. Donna Cassidy, Professor of Art and American & New England Studies at the University of Southern Maine. Discussed in this episode: early female artists, the male gaze, the feminist movement and art, interpretations of the female reclining nude, and what art can tell us about a culture.”

THE FEMALE GAZE

In case you were wondering if this is a thing, we are now coming to a place where the heterosexual female gaze is entering mainstream culture — on screen and in popular literature — rather than sticking to its usual walled garden of Harlequin Romances.

The Female Gaze: Essential Movies Made by Women

Today we will be talking to Alicia Malone, the author of The Female Gaze: Essential Movies Made by Women (Mango Publishing Group, 2018). Malone is a film critic and host on Turner Classic Films who has compiled a list of 52 films directed by women, from the early days of Hollywood to the present. Along with other guest critics, she discusses each movie to show how the female gaze is different from how men direct films.

New Books Network

Hot Dudes With Dogs from BuzzFeed

Colin Firth’s Shirt: Jane Austen And The Rise Of The Female Gaze from The Atlantic

I find it hard to believe that even though feminists have been talking about this issue since at least the 60s, not only has the situation got worse for women, it’s also getting worse for men.DOES THE RISE OF MEN’S SEXUAL OBJECTIFICATION = EQUALITY? from Sociological ImagesWatch Rebel Wilson objectify a man in a short film. (Of course, this is a backwards take on an old gag about a woman.)

Men Deemed ‘Too Handsome’ Deported from Saudi Arabia for Fear They Would Be Irresistible to Women from Gawker

Money P*rn: Simply put, men are objectified in terms of money in a way that parallels the sexual objectification of women. from PsychCentral

Male Bodies And Objectification at GMP

Male Actors Hate It When You Treat Them Like Actresses at Daily Life quote a couple of high profile men who complain about the very thing female actors have endured all along.

Chuck Wendig explains why the objectification of men isn’t ‘just as bad’ as objectification of women.In brief: Years of unfortunate history.

Pictures of men posted by a woman just don’t carry the same meaning as pictures of women posted by a men – HTML Giant

OBJECTIFICATION OF BLACK MEN

I have always been interested in African American manhood and masculinity and particularly by the way that – although contemporary discussions of objectification most often focus on the bodies of white women – Black men too are highly objectified by the news and entertainment media. Black men’s images – their bodies, in particular – are used to sell products, ideas and political campaigns, including those that are actually deleterious to Black men and their communities.

visual artist Arjuan Mance

In YA literature, the female gaze does, indeed, exist alongside the male gaze.

From Mia’s scene in If I Stay:

As thin as he was, he was surprisingly built. I could’ve spent twenty minutes staring at the contours and valleys of his chest.

(Most of the attraction is in the build-up, in fact, in which Mia imagines licking the sweat off his face as he comes off stage and so on.)

The question is, in YA sex scenes what is the perfect balance?

Sex scenes for teenage girls exist

- to arouse

- as a sort of manual

- as a subliminal messages, shaping 13-year-old expectations about what to expect in future

- as a literary mirror, to show girls that they’re not alone

I do wonder about young adult fiction aimed at girls, if (1) and (4) conflict with the feminist ideals of (2) and (3).

THE MALE GLANCE

Lili Loofbourow argues that The Male Glance is the flip side of The Male Gaze.

SELF-OBJECTIFICATION

That thing where you size yourself up every time you catch your reflection. In the absence of mirrors you’re wondering how you appear to other people… Even when other people aren’t around. That. That’s called self-objectification. Teenagers have it bad, but many carry it around for much longer.

- Women Who ‘Listen’ To Their Bodies Are Less Likely To Objectify from PsychCentral

- Body Shame On You from Beauty Redefined

- Running From Self-Objectification also from Beauty Redefined

Header painting by Charles Spencelayh – She Stoops to Conquer